Abstract

Activity of hippocampal pyramidal cells is critical for certain forms of learning and memory, and work from our lab and others has shown that CA2 neuronal activity is required for social cognition and behavior. Silencing of CA2 neurons in mice impairs social memory, and mice lacking Regulator of G-Protein Signaling 14 (RGS14), a protein that is highly enriched in CA2 neurons, learn faster than wild types in the Morris water maze spatial memory test. Although the enhanced spatial learning abilities of the RGS14 KO mice suggest a role for CA2 neurons in at least one hippocampus-dependent behavior, the role of CA2 neurons in fear conditioning, which requires activity of hippocampus, amygdala, and possibly prefrontal cortex is unknown. In this study, we expressed excitatory or inhibitory DREADDs in CA2 neurons and administered CNO before the shock-tone-context pairing. On subsequent days, we measured freezing behavior in the same context but without the tone (contextual fear) or in a new context but in the presence of the tone (cued fear). We found that increasing CA2 neuronal activity with excitatory DREADDs during training resulted in increased freezing during the cued fear tests in males and females. Surprisingly, we found that only females showed increased freezing during the contextual fear memory tests. Using inhibitory DREADDs, we found that inhibiting CA2 neuronal activity during the training phase also resulted in increased freezing in females during the subsequent contextual fear memory test. Finally, we tested fear conditioning in RGS14 KO mice and found that female KO mice had increased freezing on the cued fear memory test. These three separate lines of evidence suggest that CA2 neurons are actively involved in both intra- and extra-hippocampal brain processes and function to influence fear memory. Finally, the intriguing and consistent findings of enhanced fear conditioning only among females is strongly suggestive of a sexual dimorphism in CA2-linked circuits.

Keywords: Hippocampal CA2, DREADD, RGS14, hM3Dq, hM4Di, fear conditioning, amygdala

In fear conditioning, a naive animal is conditioned to associate an initially neutral environment or tone with an aversive unconditioned stimulus (US), such as a foot shock. After pairing the environment (the context) or the tone (the cue) with the shock US, exposure to the context or the cue alone can evoke a conditioned fear response, typically freezing in rodents (Maren, 2001). Context fear conditioning has been shown to require neuronal activity in the hippocampus, notably in area CA1, for context encoding and in the amygdala for pairing the aversive stimulus with the context (Goshen et al., 2011; Helmstetter & Bellgowan, 1994; Maren & Fanselow, 1995; Muller, Corodimas, Fridel, & LeDoux, 1997; Phillips & LeDoux, 1992; Zelikowsky, Hersman, Chawla, Barnes, & Fanselow, 2014). Medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) is also required for acquisition of context fear memory under some conditions (Gilmartin & Helmstetter, 2010; Zhao et al., 2005). Cued fear conditioning requires auditory regions and amygdala structures but does not normally require the hippocampus (LeDoux, Sakaguchi, Iwata, & Reis, 1986; Maren & Fanselow, 1995; Muller et al., 1997; Phillips & LeDoux, 1992). If the shock is delayed relative to the cue, then cued fear conditioning also requires the mPFC in order for the animal to learn the association (Gilmartin, Miyawaki, Helmstetter, & Diba, 2013).

Previous studies have attempted to separate the roles of dorsal and ventral hippocampus in context fear (Hunsaker & Kesner, 2008; Maren & Holt, 2004). In rats and mice, dorsal CA1 neurons have strong spatial properties, with well-defined place fields capable of encoding a context (Jung, Wiener, & McNaughton, 1994; Moser, Kropff, & Moser, 2008). Lesions to or inhibition of dorsal hippocampus impairs context fear memory (Bast, Zhang, & Feldon, 2003; Hunsaker & Kesner, 2008; Wiltgen, Sanders, Anagnostaras, Sage, & Fanselow, 2006). Ventral CA1 neurons, on the other hand, have less well-defined place fields and poorly encode space but likely function more in emotional and social processing, as evidenced by the brain regions targeted by ventral, but not dorsal, CA1 neurons (Fanselow & Dong, 2010; Moser & Moser, 1998; Okuyama, Kitamura, Roy, Itohara, & Tonegawa, 2016; Raam, McAvoy, Besnard, Veenema, & Sahay, 2017). Ventral CA1 neurons project directly to amygdala, mPFC and nucleus accumbens (Jay & Witter, 1991; Okuyama et al., 2016; Pitkänen, Pikkarainen, Nurminen, & Ylinen, 2000). Accordingly, lesions to or inactivation of ventral hippocampus also impairs context fear (Bast, Zhang, & Feldon, 2001; Fanselow & Dong, 2010; Maren & Fanselow, 1995; Maren & Holt, 2004; Zhang, Bast, & Feldon, 2001). Some argue that coordinated activity between hippocampus and amygdala is required for acquisition of context fear memory, supporting the notion that contextual information from dorsal and ventral hippocampus is communicated directly from ventral hippocampus to amygdala for context fear encoding (Girardeau, Inema, & Buzsáki, 2017; Kim & Cho, 2017; Maren & Fanselow, 1995; Ohkawa et al., 2015).

One synapse upstream from hippocampal CA1 neurons are CA2 neurons (Dudek, Alexander, & Farris, 2016; Kohara et al., 2014; Tamamaki, Abe, & Nojyo, 1988). The role of CA2 neurons in hippocampal physiology and behavior has only recently been studied. We and others have shown that CA2 neurons display spatial properties, including firing in place fields, and that place fields are remapped with various manipulations to the animal’s context (Alexander et al., 2016; Lee, Wang, Deshmukh, & Knierim, 2015; Lu, Igarashi, Witter, Moser, & Moser, 2015; Mankin, Diehl, Sparks, Leutgeb, & Leutgeb, 2015). In addition, mice lacking the GTP-ase activating protein Regulator of G-Protein Signaling 14 (RGS14), a protein that is highly enriched in CA2 pyramidal cells (PCs), learn faster than wild-types (WTs) in the Morris water maze test of spatial memory (Lee et al., 2010). In these RgS14 knock-out (KO) mice, CA2 PCs have increased excitability and a capacity for LTP at synapses in the CA2 stratum radiatum, where LTP normally does not occur (Lee et al., 2010; Zhao, Choi, Obrietan, & Dudek, 2007). These findings further support a role for CA2 neurons in contextual memory. In addition, CA2 neurons project both within the same coronal plane and in the caudal/posterior direction, targeting CA1 neurons in both dorsal and intermediate to ventral CA1 (Tamamaki et al., 1988). As such, CA2 neurons may transmit contextual information from the dorsal hippocampus to more ventral CA1. Ventral CA1 neurons, in turn, project to amygdala and mPFC (Jay & Witter, 1991; Kishi, Tsumori, Yokota, & Yasui, 2006). Although it is unknown how CA2 neuronal activity affects the amygdala, we previously found that modifying CA2 neuronal activity can influence mPFC activity. Therefore, CA2 neuronal activity is capable of influencing neuronal activity of more ventral CA1, as well as at least one target area of ventral CA1 neurons (Alexander et al., 2018; Meira et al., 2018).

In addition, CA2 neurons project to CA3 (Mercer, Trigg, & Thomson, 2007) and gate the communication between CA3 and CA1 (Alexander et al., 2018; Boehringer et al., 2017; Kohara et al., 2014). Accordingly, chemogenetic modification of CA2 neuron activity inversely influences sharp wave ripple (SWR) occurrence in both dorsal and ventral CA1, likely by affecting CA3 output to CA1 (Alexander et al., 2018; Boehringer et al., 2017). Interestingly, dorsal and ventral hippocampal CA1 neurons fire together during SWRs (Patel, Schomburg, Berényi, Fujisawa, & Buzsáki, 2013), and neuronal activity is modulated in a subset of basolateral amygdala (BLA) neurons by SWRs recorded in dorsal CA1, providing a link between dorsal hippocampus and BLA through ventral hippocampus during SWRs (Girardeau et al., 2017). Further, in animals exposed to an aversive stimulus in one area of a linear track, BLA neuron modulation is greater during population SWRs that include place cell reactivation encoding the aversive area and trajectory of the track (Girardeau et al., 2017), which may reflect consolidation of a contextual fear memory. In sum, CA2 neurons transmitting contextual information could connect dorsal hippocampus to more ventral hippocampus, possibly by regulating SWRs to provide a link from dorsal hippocampus to the BLA. As such, CA2 neuronal activity may play a role in context fear conditioning.

Based on previous findings that 1) CA2 neurons display spatial firing properties indicative of a role in encoding context, 2) CA2 neuronal activity inversely regulates SWR occurrence in dorsal and ventral CA1, which affects neuronal activity in BLA, and 3) modification of CA2 neuronal activity affects neuronal activity in mPFC (Alexander et al., 2018), we hypothesized that modifying CA2 neuronal activity would impact context fear conditioning, which relies on neuronal activity in CA1, BLA and, possibly, mPFC. We tested this hypothesis by expressing excitatory and inhibitory DREADDs in CA2 PCs, treating animals with the DREADD ligand, CNO, during cue and context fear conditioning, and measuring cue- and context-dependent fear responses in the days following conditioning. Because CA2 neurons in RGS14 KO mice show increased excitability, we also examined cue and context fear in RGS14 KO mice to test our hypothesis that fear conditioning in these mice would phenocopy fear conditioning in mice expressing excitatory DREADDs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Experiments were carried out in adult male and female mice. Mice were pair-housed under a 12:12 light/dark cycle with access to food and water ad libitum. In most cases, one control animal and one littermate experimental animal were housed together. Males and females were housed in the same colony room. All behavioral assays were performed during the light cycle, between 8 AM and 3 PM. All procedures were approved by the NIEHS Animal Care and Use Committee and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of North Carolina and were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for care and use of animals.

Virus infusion and tamoxifen treatment

For virus-infusion surgery, mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg, IP) and xylazine (7 mg/kg, IP), then placed in a stereotaxic apparatus. An incision was made in the scalp, a hole was drilled over each target region for AAV infusion, and a 27-ga cannula connected to a Hamilton syringe by a length of tube was lowered into hippocampus (in mm: −2.3 AP, +/−2.4 ML, −1.9 DV from bregma). Mice were infused bilaterally for both hM3Dq (AAV-hSyn-DIO-hM3D(Gq)-mCherry; Serotype 5; University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Viral Vector Core) and hM4Di AAV (AAV-hSyn-DIO-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry; Serotype 5; University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Viral Vector Core). For each infusion, 0.5 μl was infused at a rate of 0.1 μl/min. Following infusion, the cannula was left in place for an additional 10 minutes before removing. The scalp was then sutured and the animals administered buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg, SQ) for pain and returned to their cage. All mice received virus infusions, but only the mice expressing cre recombinase (Cre+) showed expression of the DREADD proteins (Fig. 1A, S1).

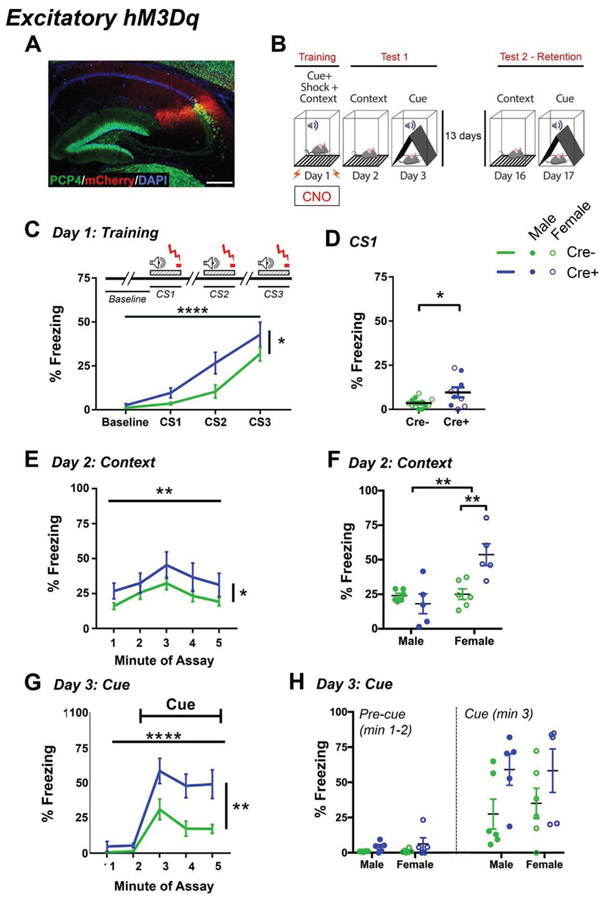

Figure 1.

Contextual and cued fear conditioning in hM3Dq mice. A, hM3Dq-mCherry expression colocalizes with PCP4, a marker of CA2 neurons. B, Schematic of the fear conditioning paradigm. C, Percent of time spent freezing during training. Freezing was measured during the baseline period (before any tone-shock pairing) and during each of the three conditioned stimulus (CS) tone-shock pairings. A shock (unconditioned stimulus, US) was delivered during the final 2 sec of each 30-sec CS tone presentation. The schematic diagram shows the relative time-course of tone CS and shock US presentation. Freezing during each CS presentation was measured for the entire tone presentation, which included the 2-sec shock. D, Freezing for each mouse during the first tone CS-shock presentation. Freezing was significantly increased in Cre+ mice. E-H, Contextual (E-F) and cued (G-H) fear results from Test 1. E, Mean freezing across time for each genotype showed main effects of genotype and time. A main effect of sex was also detected, as well as an interaction between sex and genotype, prompting us to analyze each sex independently. F, Mean percent of time freezing across all five minutes of the contextual fear test. Cre+ female, but not male, mice showed enhanced freezing behavior relative to Cre− mice. G, Freezing for each minute of the cued fear test. Analysis of freezing for all five minutes of the test showed main effects of genotype and time and an interaction between genotype and time. H, Percent of time freezing during the pre-cue period and the first minute of the tone presentation in the cued fear memory test for male and female mice. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001. Lines show means and SEM, filled dots represent individual male animals, open circles represent individual females. Scale bar represents 300 μm in A. See also Fig. S1-3, S5.

For hM3Dq studies, 24 adult Cre+ and Cre− (12 Cre+, 12 Cre−; 8-12 weeks old) Amigo2-cre mice (Alexander et al., 2017) were infused bilaterally with hM3Dq. For hM4Di studies, 31 adult Cre+ and Cre− (15 Cre+, 16 Cre−; 8-12 weeks old) Amigo2-icreERT2 mice (Alexander et al., 2018) were infused bilaterally with hM4Di AAV. Two weeks following AAV infusion surgery, Amigo2-icreERT2 mice began daily tamoxifen treatments (100 mg/kg tamoxifen dissolved in warmed corn oil, IP) for a total of 7 days. Approximately two weeks following infusion and/or tamoxifen administration, mice were transferred to the University of North Carolina Mouse Behavioral Phenotyping Laboratory in Chapel Hill, NC. Mice were 20-24 weeks old at the start of the fear conditioning assay. Two mice were removed from the study; one mouse for having a baseline freezing percentage of greater than 3 SD away from the mean (25% of baseline period time) and another for displaying a “wild-running” fear response instead of freezing consistently in tests of fear memory.

For RGS14 KO studies, 58 male and female KO and littermate control RGS14 KO mice (29 RGS14−/−, 29 RGS14+/+) were bred from RGS14 heterozygous mice (Lee et al., 2010) and used for these studies. At 3-4 weeks of age, mice were transferred to the University of North Carolina Mouse Behavioral Phenotyping Laboratory in Chapel Hill, NC. Mice were 22-23 weeks old at the start of the fear conditioning assay.

Apparatus

Mice were evaluated for learning and memory in a conditioned fear test, using the Near-Infrared image tracking system (MED Associates, Burlington, VT). Levels of freezing (no movement for 0.5 sec) before and during the stimulus were obtained by the image tracking system.

Fear conditioning

All behavioral tests were conducted by investigators blinded to genotype. On Day 1, all hM3Dq and hM4Di mice were treated with CNO (hM3Dq: 1 mg/kg, IP; hM4Di: 5 mg/kg, IP) 50 minutes before a 7.5-min training session. Mice were placed in the test chamber, contained in a sound-attenuating box, and allowed to explore for 2 min. The mice were then exposed to a 30-sec tone (80 dB) with a 2-sec scrambled foot shock (0.4 mA) during the final 2 sec of the tone. Mice received 2 additional shock-tone pairings, with 80 sec between each pairing. Mice were then returned to their home cage and returned to the animal colony. Training boxes were wiped clean with water and dried with paper towels between each animal, and then cleaned with 70% ethanol at the end of each day.

Context- and cue- dependent short-term retention tests

On Day 2, mice were placed back into the original conditioning chamber for a test of contextual learning. Levels of freezing were measured across the 5-min session. Mice were then returned to their home cage and returned to the animal colony.

On Day 3, mice were evaluated for associative learning to the auditory cue in another 5-min session. The conditioning chambers were modified using a Plexiglas insert to change the wall and floor surface, and a novel odor (dilute vanilla flavoring) was added to the sound-attenuating box. Mice were placed in the modified chamber and allowed to explore. After 2 min, the acoustic stimulus (an 80-dB tone) was presented for a 3-min period. Freezing was measured during presentation of the tone.

Long-term retention tests

Two weeks following the first test for contextual learning, mice were given a second test, using the same 5-min context test procedure in the original conditioning chambers, described above. On the following day, mice were given a second test for cue-dependent learning in the modified fear conditioning chambers, as described above.

Statistical Analyses

Before beginning this study, we sought to investigate genotype and sex differences in conditioned fear measures for hM3Dq, hM4Di and RGS14 KO mice. All data were checked for normal distribution, and the appropriate statistical test was chosen for each analysis. The percent of time spent freezing during each minute of training and during each minute of the context and cue test were measured and are presented as percent freezing. Baseline freezing levels were compared using nonparametric Mann Whitney tests. Freezing during training was compared using repeated-measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVAs) with the between subject factors of genotype and sex and the within-subjects factor of each minute of training. Freezing data were not obtained for one male, Cre+ hM3Dq mouse during training due to tracking software failure. Visual inspection of video during training confirmed shock responsiveness, but freezing levels during training are not included with training freezing data. Freezing during the context and cue tests were compared between control and experimental groups in two ways. First, for both the context and cue tests, ANOVAs with the between subject factors of genotype and sex and the within-subjects factor of each minute of the test were used. For the context tests, we also calculated the mean percent freezing across all five minutes and compared groups using a two-way ANOVA with the between subject factors of genotype and sex. For the cue tests, freezing only during minute three (the first minute of the tone) with the between subject factors of genotype and sex was also compared using a two-way ANOVA. If a main effect of sex or an interaction with sex was found, then males and females were analyzed separately. Fisher’s protected least significant difference post hoc tests were used when significant main effects were identified. Data was analyzed using SPSS software (IBM Corp., version 21). Significance was set at p<0.05.

Immunostaining

Animals used for immunohistochemistry were euthanized with Fatal Plus (sodium pentobarbital, 50 mg/mL; >100 mg/kg) and underwent transcardial perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose PBS for at least 72 hours and sectioned with a cryostat or vibratome at 40 μm. For immunohistochemistry, brain sections were rinsed in PBS, boiled in deionized water for 3 min, and blocked for at least 1 h in 3-5% normal goat serum/0.01% Tween 20 PBS. Sections were incubated in the following primary antibodies, which have previously been validated in mouse brain(Hitti & Siegelbaum, 2014; Kohara et al., 2014): rabbit anti-PCP4 (SCBT, sc-74186, 1:500), rat anti-mCherry (Life Technologies, M11217, 1:500- 1:1000), mouse anti-RGS14 (UC Davis/NIH NeuroMab Facility, AB_10698026, 1:1000). Antibodies were diluted in blocking solution and sections were incubated for 24 h. After several rinses in PBS/Tween, sections were incubated in secondary antibodies (Alexa goat anti-mouse 488 and Alexa goat anti-rabbit 568, Alexa Goat anti-rat 568, Invitrogen, 1:500) for 2 h. Finally, sections were washed in PBS/Tween and mounted under ProLong Gold Antifade fluorescence media with DAPI (Invitrogen). Images of hippocampi were acquired on a Zeiss 780 meta confocal microscope using a 40× oil-immersion lens. Images of whole-brain sections were acquired with a slide scanner using the Aperio Scanscope FL Scanner (Leica Biosystems Inc.).

Animals used for immunoblotting were euthanized with Fatal Plus (sodium pentobarbital, 50 mg/mL; >100 mg/kg) and decapitated. Brains were rapidly removed and homogenized on ice in ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher, 89901) with HALT protease and phosphatase inhibitor (ThermoFisher, 78440). Mouse brain homogenates were sonicated on ice and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Samples in sample buffer were loaded onto a 4-12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen, NP0321BOX) and subjected to gel electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using the iBlot gel transfer apparatus (Invitrogen) and subjected to immunoblotting by incubating in Odyssey blocking buffer (LI-COR, 927-50100) then in blocking buffer plus mouse anti-RGS14 (UC Davis/NIH NeuroMab Facility, AB_10698026, 1:500) and rabbit anti beta-actin (Abcam, ab8227, 1:5000) overnight at 4°C. After several rinses in PBS/Tween, membranes were incubated in donkey anti-rabbit IRDye secondary antibody (LI-COR Biosciences, 925-32213, 1:10,000) and donkey anti-mouse IRDye secondary antibody (LI-COR Biosciences, 925-68072, 1:10,000), rinsed and imaged on an Odyssey infrared scanner (LI-COR Biosciences).

RESULTS

DREADD-mediated CA2 activation increases contextual and cued fear

To investigate the role of CA2 neurons in hippocampal dependent memory, we first asked whether mice expressing the excitatory hM3Dq (Fig. 1A, S1) in the fear conditioning assay had altered freezing responses. Mice were administered CNO (1 mg/kg, IP) 50 min before the training session and were returned to their home cage until training began (Fig. 1B). CNO was not administered before any other phase of the assay. Before presentation of the tone or shock, baseline freezing was measured in the context. Levels of baseline freezing were not significantly different between Cre− and Cre+ mice (median (Cre−)=0.695% of baseline period; median (Cre+)=1.6% of baseline period; U=57.5, p=0.8818, Mann-Whitney test, N=12 Cre− mice, 10 Cre+ mice). We also measured freezing in response to the tone-shock pairing during training. Freezing was measured over the entire 30-sec period, and the shock was delivered during the final 2 sec of that period. The mean percent of time freezing significantly increased across the three tone presentations during training (main effect of time: F(2,34)=32.007, p<0.0001; Fig. 1C). In addition, freezing was significantly greater for Cre+ mice than Cre− mice during training (main effect of genotype: F(1,17)= 6.240, p=0.023), although freezing was not significantly different between males and females (main effect of sex: F(1,17)=0.156, p=0.698) and no interaction between genotype and sex was detected (interaction: F(1,17)= 0.009, p=0.925). Interestingly, freezing was significantly greater for Cre+ mice even during the first 30-sec tone/shock presentation (t(19)=2.309, p=0.0324, unpaired t-test; Fig. 1D), suggestive of a tone fear. However, we saw no difference between Cre+ and Cre− mice in activity during any of the three shock stimuli, suggesting that pain threshold was not affected by CA2 activation (main effect of genotype: (F(2,38)=0.5608, p=0.5754; Fig. S2A).

Contextual fear memory was tested 24 hours after training (Fig. 1B). Cre+ mice showed enhanced freezing behavior relative to Cre− mice when placed in the context, as measured by the mean percent of time freezing across all five minutes (main effect of genotype: F(1,18)=5.085, p=0.037; Fig. 1E). Freezing also varied significantly as a function of time in the context (main effect of time (F(4,72)=4.862, p=0.002). A main effect of sex was also detected (F(1,18)=9.972, p=0.005), as well as an interaction between sex and genotype (F(1,18)=11.924, p=0.003) due to significantly greater freezing in Cre+ females relative to Cre− females (p=0.0013; Fig. 1F, S3A). By contrast, males showed no difference in freezing between genotypes (p=0.4412; Fig. 1F, S3A).

Cue fear memory was tested the following day. Mice were placed into a novel chamber distinct from the context chamber and freezing was measured before and during the tone cue presentation. Levels of freezing during each of the five minutes of the test showed a main effect of genotype (F(1,18)=10.235, p=0.005; Fig. 1G) and a main effect of time (F(4,72)=40.101, p<0.0001), with significant increases in freezing corresponding to cue onset. An interaction between genotype and time was also found (F(4,72)=5.503, p=0.009). However, we found no difference in freezing between males and females (F(1,18)=1.153, p=0.297). In the two minutes before the onset of the tone cue, freezing was not significantly different between Cre+ and Cre− mice (main effect of genotype: F(1,18)=3.797; p=0.0671; Fig. 1H) or between male and female mice (main effect of sex: F(1,18)=0.3059; p=0.5870). However, freezing during the first minute of the cue presentation was greater for Cre+ mice relative to Cre− mice (main effect of genotype, F(1,18)=5.209, p=0.035; Fig. 1H), with no difference in freezing between males and females detected (main effect of sex: F(1,18)=0.080, p=0.781) nor an interaction between sex and genotype (F(1,18)=0.122, p=0.731), therefore post hoc tests within each sex were not performed.

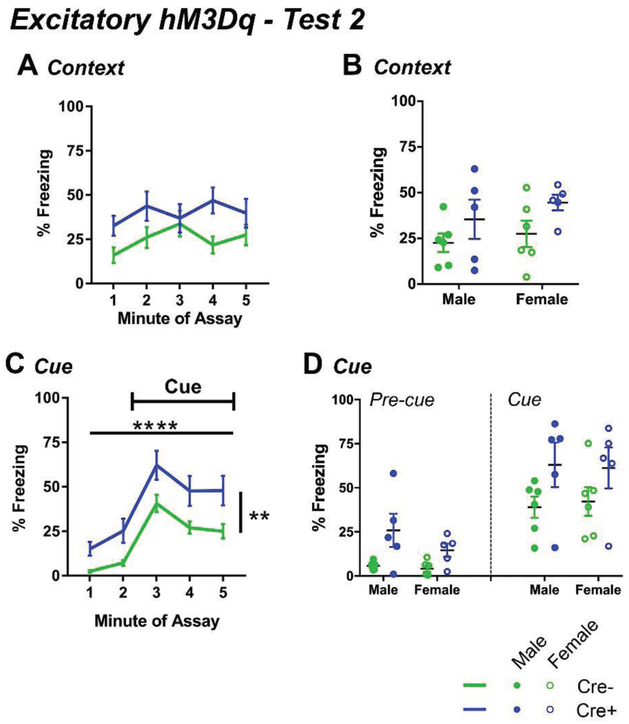

Thirteen days later, long-term retention of contextual and cued fear memory was tested. In the context, Cre+ mice showed a trend toward increased freezing over Cre− mice but did not reach significance (F(1,18)=4.402, p=0.05; Fig. 2A-B, S4A). No difference in freezing was detected between males and females, and no difference in freezing across time was detected (main effect of sex: F(1,18)=0.975, p=0.336; main effect of time: F(4,72)=1.795, p=0.139; Fig. 2A-B). In contrast, in the retention test for cued fear, Cre+ mice showed significantly more freezing than Cre− mice over all five minutes of the test (main effect of genotype: F(1,18)=9.197, p=0.007; main effect of time: F(4,72)=43.992, p<0.0001; Fig. 2C, S4B). However, freezing did not differ between males and females (main effect of sex: F(1,18)=0.025, p=0.641), and there was no significant interaction between sex and genotype (F(1,18)=0.077, p=0.784). In the two minutes before the onset of the tone cue, freezing was significantly greater among Cre+ mice compared with Cre− mice (main effect of genotype: F(1,18)=10.543; p=0.004; Fig. 2D, S4B), which likely reflects second order conditioning (Holland, 1977), but freezing did not differ between male and female mice (F(1,18)=1.889; p=0.186) and no interaction between sex and genotype was detected (F(1,18)=1.068; p=0.315). Similarly, analysis of the first minute of the tone presentation showed that Cre+ mice had significantly more freezing behavior than Cre− mice (F(1,18)=5.080, p=0.037; Fig. 2C-D), but no effect of sex (F(1,18)=0.006, p=0.940) nor an interaction (F(1,18)=0.067, p=0.799) was detected, therefore post hoc tests within each sex were not performed.

Figure 2.

Long-term retention of contextual (A-B) and cued (C-D) fear conditioning two weeks after training in hM3Dq mice. Data correspond to Test 2 from Fig. 1B. A, Mean percent of time freezing for all five minutes of the contextual fear retention test. Cre+ mice trended toward more freezing than Cre− mice. Freezing for all animals did not vary as a function of time in the context. B, Mean freezing across time for each genotype for males and females. C, Freezing for each minute of the cued fear test. Cre+ mice showed more freezing than Cre− mice. D, Percent of time freezing during the pre-cue period and the first minute of the tone presentation in the cued fear memory test for male and female mice. **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001. Lines show means and SEM, filled dots represent individual males, open circles represent individual females. See also Fig. S4-S5.

Comparing freezing levels from Test 1 (24-48 hours after training) to Test 2 (2 weeks after training) showed no main effect of test for either contextual fear (Fig. S5A-B) or cued fear (Fig. S5C-D) but did show a main effect of genotype among females for the contextual fear test (F(1,18)=14.14, p=0.0014; Fig. S5B) and among males for the cued fear test (F(1,18)=7.476, p=0.0136; Fig. S5C), with females also trending toward a main effect of genotype in the cued fear test (F(1,18)=3.382, p=0.0825; Fig. S5C).

DREADD-mediated inhibition of CA2 increases contextual fear in females

We next tested mice expressing the inhibitory hM4Di in the fear conditioning assay (Fig. 3A-B). Mice were administered CNO (5 mg/kg, IP) 50 min before the training session and were returned to their home cage until training began. CNO was not administered before any other phase of the assay (Fig. 1B). Before presentation of the shock or tone, baseline freezing was measured in the context. Levels of baseline freezing were not significantly different between Cre− and Cre+ mice (median (Cre−)=0.7281% of baseline period; median (Cre+)=1.03% of baseline period; U=92, p=0.2620, Mann-Whitney test, N=16 Cre− mice, 15 Cre+ mice, Fig. 3C). During training, the mean percent of time freezing significantly increased across the three tone/shock presentations (main effect of time: F(2,54)=69.733, p<0.0001; Fig. 3C). However, freezing during training was not significantly affected by genotype (F(1,27)=0.726, p=0.402) or sex (F(1,27)=0.039, p=0.844). In addition, activity in response to the shock was not significantly different between Cre− and Cre+ mice (F(1,27)=3.226, p=0.084; Fig. S2B).

Figure 3.

Contextual and cued fear conditioning in hM4Di mice. A-B, hM4Di-mCherry expression colocalizes with PCP4, a marker of CA2 neurons. C, Percent of time spent freezing during the baseline period before any tone-shock pairing, and freezing during each of the three conditioned stimulus (CS) tone-shock pairings. D, Mean freezing across time upon re-exposure to the context 24 hours after training. A main effect of genotype and of time and an interaction between time and genotype were found. A main effect of sex was also detected. E, Average freezing over the five-minute context fear test. Males showed no difference in freezing across genotype, but among females, Cre+ mice showed significantly more freezing than Cre− mice. F, Freezing for each minute of the cued fear test. G, Percent of time freezing during the pre-cue period and the first minute of the tone presentation in the cued fear memory test. Lines show means and SEM, filled dots represent individual males, open circles represent individual females. Result of post hoc tests shown on graph. *p<0.05, ****p<0.0001. Scale bar represents 1 mm in A, 300 μm in B. See also Fig. S6, S8.

In the test of contextual fear memory, Cre+ mice showed significantly more freezing than Cre− mice (main effect of genotype: F(1,27)=4.556, p=0.042; Fig. 3D). Mean freezing across time for each genotype showed a main effect of time (F(4,108)=3.420, p=0.011) and an interaction between time and genotype (F(4,108)=2.891, p=0.026). A main effect of sex was also detected (F(1,27)=5.905, p=0.022), prompting us to analyze each sex independently (Fig 3E, S6A). Males showed no difference in freezing across genotype (p=0.6928; Fig. 3E, S6Ai). In contrast, among females, Cre+ mice showed significantly more freezing than Cre− mice (p=0.0130; Fig. 3E, S6Aii). In the test of cued fear memory, we found a significant main effect of time across the five minutes of the test (F(4,108)=63.927, p<0.0001; Fig. 3F), but we detected no differences in freezing between Cre+ and Cre− hM4Di mice (main effect of genotype: F(1,27)=0.030, p=0.864; Fig. 3F, S6B). In addition, we found no difference in freezing between males and females (main effect of sex: F(1,27)=0.001, p=0.981). Analysis of freezing during the two minutes before cue onset showed no effect of genotype (F(1,27)=0.3169, p=0.5781) and analysis of the first minute of the cue also showed no difference in freezing across genotypes (F(1,27)=0.003, p=0.958; Fig. 3G).

To determine whether inhibiting CA2 activity during conditioning impacted longer-term retention of contextual fear memory, we tested the animals two weeks after training. In this case, we found no difference in freezing between Cre+ and Cre− mice (F(1,27)=1.104, p=0.303; Fig. 4A, S7A) or between males and females (F(1,27)=0.017, p=0.897; Fig. 4B). Freezing also did not vary significantly as a function of time in the context (F(4,108)=1.693, p=0.157; Fig. 4A, S7A). Similarly, we found no difference in freezing between Cre+ and Cre− mice or between males and females in the long-term retention test for cued fear memory, as measured over all five minutes of the test (main effect of genotype: F(1,27)=0.016, p=0.901; main effect of sex (F(1,27)=1.566, p=0.221; Fig. 4C, S7B) despite freezing being significantly affected by time in the test of cued fear (F(4,108)=65.777, p<0.0001). Further, analysis of freezing during the two minutes before cue onset showed no significant effect of genotype or sex (main effect of genotype: F(1,27)=0.3944, p=0.5353; main effect of sex: F(1,27)=0.04022, p=0.8426; Fig. 4D), and freezing was also not significantly affected by genotype or sex during the first minute of the cue (main effect of genotype: F(1,27)=0.051, p=0.822; main effect of sex: F(1,27)=0.051, p=0.822; Fig. 4D). These data show in female but not male mice, CA2 neuron silencing during fear conditioning led to increased contextual freezing.

Figure 4.

Long-term retention of contextual (A-B) and cued (C-D) fear conditioning in hM3Di mice two weeks after training. Data correspond to Test 2 from Fig. 1B. A, Mean contextual freezing across time for each genotype. B, Mean percent of time freezing across all five minutes of the contextual fear test for males and females. C, Freezing across each minute of the cued fear test. D, Percent of time freezing during the pre-cue period and the first minute of the tone presentation in the cued fear test. Lines show means and SEM, filled dots represent individual males, open circles represent individual females. ****p<0.0001. See also Fig. S7, S8.

Finally, comparing freezing levels from Test 1 to Test 2 showed no main effect of test for either contextual fear (Fig. S8A-B) or cued fear (Fig. S8C-D) but a main effect of genotype among females for the contextual fear test (F(1,28)=0.7968, p=0.0087; Fig. S8B).

Female RGS14 KO mice have increased cued fear memory

Finally, because CA2 pyramidal neurons in RGS14 KO mice are more excitable that those from WT mice and abnormally can express LTP (Lee et al., 2010), we explored whether RGS14 KO would also have aberrant behavior following fear conditioning. RGS14 is expressed at high levels in CA2 of WT mice (Fig. 5A-B), but RGS14 KO mice do not expresses transcripts for RGS14 (Fig. 5C). Before presentation of the shock or tone, baseline freezing was measured in the context. Levels of freezing were not significantly different between WT and KO mice (median (WT)= 1.45% of baseline period; median (KO)=1.44% of baseline period; U=370.5, p=0.4419, Mann-Whitney test, N=29 WT mice, 29 KO mice, Fig. 5D). During training, the mean percent of time freezing significantly increased across the three tone/shock presentations (main effect of time: F(2,108)=80.804, p<0.0001; Fig. 5D), although freezing during training was not significantly affected by genotype (F(1,54)=0.330, p=0.568). Overall, collapsed data of freezing from the three tone/shock pairings showed greater freezing among females than males (main effect of sex: (F(1,54)=6.302, p=0.015), but there was no significant interaction between genotype and sex in the level of freezing during training (F(1,54)=0.078, p=0.780). Measuring motion during the two sec immediately before, during, and immediately following shock presentation showed that KO mice were slightly, but significantly, less active during those times, and this effect was sex-specific; no difference in activity was detected among male mice (F(1,33)=0.4187, p=0.5221; Fig. S2Ci), but female KO mice showed less activity than female WT mice (F(1,21)=7.095, p=0.0145; Fig. S2Cii).

Figure 5.

Contextual and cued fear conditioning in RGS14 KO and WT mice. A-B, RGS14 protein staining in a whole-brain coronal section (A) and in the hippocampus, showing staining in CA2 and the fasciola cinerea (B). C, Western blot analysis showing protein expression of RGS14 and beta-actin loading control in RGS14 KO and WT control mice. D, Percent of time spent freezing during the baseline period before any tone-shock pairing, and freezing during each of the three conditioned stimulus (CS) tone-shock pairings. E, Mean freezing across time for each genotype in the context fear test. F, Mean percent of time freezing across all five minutes of the contextual fear test for each of males and females. G, Freezing across each minute of the cued fear test. H, Percent of time freezing during the pre-cue period and the first minute of the tone presentation in the cued fear memory test for males and females. Lines show means and SEM, filled dots represent individual males, open circles represent individual females. Scale bar represents 1 mm in A, 300 μm in B. ****p<0.0001. See also Fig. S9, S11.

Freezing was not significantly different between WT and KO mice in the first test of either contextual fear or cued fear. In the context, freezing varied significantly with time (F(4,216)=11.043, p<0.0001; Fig. 5E) but did not differ between genotypes (F(1,54)=1.476, p=0.230; Fig. 5E-F), and no interaction between time and genotype was detected (F(4,216)=0.883, p=0.475). Similarly, no significant effect of sex was detected on level of contextual freezing (F(1,54)=3.958, p=0.052; Fig. 5F, S9A). In the test of cued fear memory, across the five minutes of the test, freezing varied significantly with time (F(4,216)=102.298, p<0.0001; Fig. 5G) but did not differ according to genotype (F(1,54)=0.034, p=0.855; Fig. 5G) or sex (F(1,54)=0.007, p=0.936; Fig. 5H, S9B). Analysis of freezing during the two minutes before cue onset showed no effect of genotype (F(1,54)=0.1261, p=0.7239; Fig. 5H) or sex (F(1,54)=1.243, p=0.2698). Analysis of the first minute of the cue also showed no difference in freezing between genotypes (F(1,54)=0.166, p=0.685; Fig. 5H) or sexes (F(1,54)=0.337, p=0.564) and no significant interaction between genotype and sex (F(1,54)=3.187, p=0.0800).

In the long-term retention test of contextual fear memory, we found no difference in freezing between WT and KO mice (F(1,54)=1.175, p=0.283; Fig. 6A-B). However, freezing varied significantly with time in the context (F(4,216)=8.425, p<0.0001; Fig. 6A). We also observed a significant main effect of sex (F(1,54)=7.092, p=0.010; Fig. 6B) as well as a significant interaction between time and sex (F(4,216)=4.465, p=0.002). Upon analysis of freezing for each sex individually, we found that neither males nor females showed a significant difference in freezing across genotype (males: F(1,33)=0.015, p=0.903), females: F(1,21)=2.061, p=0.167; Fig. 6B, S10A).

Figure 6.

Long-term retention of contextual (A-B) and cued (C-D) fear conditioning in RGS14 KO and WT mice two weeks after training. Data correspond to Test 2 from Fig. 1B. A, Mean freezing across time for each genotype in the test of context fear. B, Mean percent of time freezing during all five minutes of the context fear test for males and females. C, Freezing for each minute of the cued fear test. D, Percent of time freezing during the pre-cue period and the first minute of the tone presentation in the cued fear test for male and female mice. Females showed significantly greater freezing during the first minute of the cue presentation. Lines show means and SEM, filled dots represent individual males, open circles represent individual females. *p<0.05, ****p<0.0001. See also Fig. S10, S11.

In the long-term retention test of cued fear memory, freezing differed between KO and WT mice, but only among females. Analysis of all five minutes of the cued fear retention test showed significant changes in freezing with time (F(4,216)=63.209, p<0.0001; Fig. 6C) but no significant differences in freezing according to genotype (F(1,54)=1.907, p=0.173) or sex (F(1,54)=1.293, p=0.261). Analysis of freezing during the two minutes before cue onset showed no effect of genotype (F(1,54)=0.9989, p=0.3220; Fig. 6D) but a significant effect of sex, with males showing more freezing than females (F(1,54)=5.634, p=0.0212). During the first minute of the cue, we found no difference in freezing between KO and WT mice (F(1,54)=0.540, p=0.466; Fig. 6D) or between males and females (F(1,54)=0.009, p=0.924). However, we found a significant interaction between genotype and sex in freezing during the first minute of the cue (F(1,54)=7.788, p=0.007), whereby freezing tended to decrease in KO mice among males (p=0.1083; Fig. 6D, S10Bi) but significantly increased in KO mice among females (p=0.0273; Fig. 6D, S10Bii).

Finally, comparing freezing levels from Test 1 to Test 2 showed no main effect of test for either contextual fear (Fig. S11A-B) or cued fear (Fig S11C-D) but a main effect of genotype among females in the cued fear test (F(1,42)=5.745, p=0.0211; Fig. S11D).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated whether modifying CA2 neuronal activity during fear conditioning would impact fear memory. Strikingly, we found a robust sex difference in the behavioral outcomes after CA2 activation or inhibition. Increasing CA2 neuronal activity with excitatory DREADDs during training resulted in increased freezing in females and in males upon the cued fear memory tests, but only females exhibited increased freezing during the contextual fear memory test. Using inhibitory DREADDs, we found that inhibiting CA2 neuronal activity during training similarly increased freezing in females on the subsequent contextual fear memory test, with no changes in male behavior. Finally, in RGS14 KO mice, which have been shown to have increased levels of CA2 neuronal activity (Lee et al., 2010), we found increased freezing in females during the cued fear memory test but not during the contextual fear memory test. In addition, to further investigate whether altering CA2 neuronal activity during fear conditioning engages extrahippocampal regions, we tested all of our animals two weeks after training. This time point for memory recall is well beyond the timeframe for hippocampal-dependent memory, and previous studies have outlined important distinctions in interpreting freezing behavior measured at 24 hours and 14 days post-training (Balogh & Wehner, 2003). While statistical significance may have been lost or gained between Test 1 (24 and 48 hours after training) and Test 2 (two weeks after training) due to changes in variability, the patterns of freezing remained constant within our control and experimental groups across each experiment (see Fig. S5, S8, S11), suggesting that altering CA2 neuronal activity has a persistent effect on behavioral responses to fear that likely engage extrahippocampal circuits to facilitate long-term memory storage. Together, these findings demonstrate a potentially sexually-dimorphic role for CA2 neuronal activity in facilitating conditioned fear behavioral responses.

Males and females expressing hM3Dq in CA2 neurons and administered CNO before conditioned fear training on day 1 of the task showed increased freezing in the test of cued fear memory two days and two weeks after training. We have previously shown that CA2 activation with hM3Dq increases neuronal activity in CA1 and in mPFC (Alexander et al., 2018), likely via CA1. Because CA1 neurons also project to amygdala (Kishi et al., 2006), a possible scenario is that CA2 activation with hM3Dq would similarly increase neuronal activity in amygdala and promote encoding of cued fear memory, which is amygdala-dependent (Maren & Fanselow, 1996; Rogan, Stäubli, & LeDoux, 1997). In support of this idea, direct activation of amygdala neurons during conditioned fear training by expressing hM3Dq sparsely in amygdala and administering CNO before training has previously been shown to increase cued fear (Yiu et al., 2014). The neurons in the amygdala that expressed hM3Dq were nearly four-fold more likely to express the immediate-early gene Arc after testing for cue fear memory 24 hours later than the neurons that did not express hM3Dq, suggesting that hM3Dq-mediated excitation of amygdala neurons during training is sufficient to allocate those particular amygdala neurons to a cued fear memory engram and increase cued freezing. Similarly, if activity of amygdala neurons was increased by hM3Dq in CA2 during training, the cued fear engram may have been more strongly encoded in hM3Dq animals than in control animals, thereby enhancing cued fear memory both two days and two weeks after training. In addition, perineuronal nets (PNNs) are heavily expressed in CA2 (Carstens, Phillips, Pozzo-Miller, Weinberg, & Dudek, 2016), similar to expression observed in several cortical regions (Alpár, Gärtner, Härtig, & Brückner, 2006). Interestingly, PNNs in auditory cortex are regulated by fear conditioning in that mRNA of several PNN components has been shown to be increased four hours after training (Banerjee et al., 2017). Further, this regulation of PNNs in the auditory cortex during auditory fear conditioning was found to be necessary for fear expression (i.e., freezing) during tone presentations 24 and 48 hours after training. Thus, it is possible that PNNs in CA2 are similarly regulated during fear conditioning and CA2 activation enhances this regulation, ultimately leading to increased freezing during cue presentations.

Another interesting observation was that hM3Dq mice also showed increased freezing relative to controls during training, as early as during the first CS-US pairing. Because freezing during training was increased during the first presentation of the tone and shock, before the pairing was learned, it is possible that in the presence of CNO, hM3Dq mice had increased tone fear. We think that this effect is not likely to be an effect of CNO because control mice also received CNO before training. We also don’t believe this effect to be due to increased general anxiety among hM3Dq mice because we have previously shown that open-arm entries in the elevated plus maze and time in the center of an open field are not different between CNO-treated hM3Dq mice and control littermates (Alexander et al., 2017). However, CA2 has reciprocal connections with the supramammillary nucleus (SuM) (Cui, Gerfen, & Young, 2013), a region implicated in arousal and attention (Pedersen et al., 2017). Thus, it is possible that the activation of CA2 neurons enhanced attention to the tone during training through activation of the SuM. Although it is unclear whether CA2 engagement of SuM upon hM3Dq activation increased alertness and possibly fear to the tone cue, the presumptive tone fear in hM3Dq mice could have strengthened the tone-shock association leading to long-lasting cued fear, resulting in increased freezing in response to the tone on both cued fear tests in males and females.

Perhaps our most striking finding was the dramatic sex difference in tests of contextual fear memory. Female mice, but not male mice, expressing hM3Dq showed increased freezing relative to Cre− mice in the tests of contextual fear memory across both of Test 1 and Test 2 (see Fig. S5A-B). We think this increased freezing is unlikely to be a byproduct of enhanced cued fear for several reasons. First, cued fear was enhanced in both male and female hM3Dq mice, whereas contextual fear was only enhanced in female mice. Second, cued and contextual fear are thought to be mediated by distinct brain circuits (Jutras, Fries, & Buffalo, 2009; Phillips & LeDoux, 1992; Spellman et al., 2015). Accordingly, strengthening of the cued fear pathways would not necessarily strengthen the context fear pathways. Third, cued fear learning can interfere with, or overshadow, contextual fear learning if the shock is delivered immediately after the tone during training (Marlin, 1981; McKinzie & Spear, 1995). As such, given the stronger association between the tone and shock that hM3Dq mice formed relative to control mice, one would expect no difference or decreased freezing in the context in hM3Dq mice relative to control mice, which is not what we found.

Increasing CA2 activity in hM3Dq female mice may have increased contextual fear learning through any of several possible mechanisms. One possibility is that CA2 neurons could have driven CA1 neuron firing to more strongly encode the hippocampal CA1 engram that represented the conditioning context (Liu et al., 2012; Tanaka et al., 2014; Tonegawa, Pignatelli, Roy, & Ryan, 2015). Alternatively, or in addition, enhanced context encoding may have been mediated by network oscillatory activity. We have previously shown that activating CA2 cells with hM3Dq increases gamma oscillations and synchrony between the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (Alexander et al., 2018), and gamma oscillations have been shown to be positively associated with memory encoding (Jutras et al., 2009; Spellman et al., 2015). In these experiments, we had used both males and females and we did not detect a sex difference in the magnitude of increases or decreases in gamma power or gamma coherence; however, we had not aimed to address sex differences in that study, so we were underpowered to query sex differences. Finally, CA2 PCs project toward intermediate and ventral CA1 (Tamamaki et al., 1988), and ventral CA1 neurons project to mPFC and amygdala (Jay & Witter, 1991; Kishi et al., 2006). Females show higher activation of BLA neurons, as measured by c-fos, during contextual fear memory retrieval than do males (Keiser et al., 2017), and mPFC dendritic complexity is dynamically changed in a sex-specific manner after exposure to stress (Garrett & Wellman, 2009). Based on these physiological and anatomical findings, one possibility is that hM3Dq activation of CA2 neurons may have produced increased context fear conditioning in females through disynaptic entrainment of amygdala or mPFC neuronal firing and/or synchrony through gamma oscillations. This potential for enhanced hippocampal-BLA/mPFC engagement may underlie the stark sex difference we observed in contextual fear memory of hM3Dq mice.

Surprisingly, we found a similar behavioral effect in females expressing hM4Di as females that expressed hM3Dq in that these mice also showed increased freezing in the test of contextual fear memory 24 hours after training. Similar to the hM3Dq mice, the significant increase in freezing did not remain statistically significant two weeks later, but including data from Test 1 and Test 2 in the analysis revealed a main effect of genotype among females (see Fig. S8B). In other words, Cre+ females froze more in contextual fear tests than their Cre− littermates across the life of the experiment.

We have previously shown that CNO administration to mice expressing hM4Di in CA2 neurons results in decreased synaptic output to CA1 and decreased hippocampal and prefrontal cortical low gamma oscillations (Alexander et al., 2018). Based on these findings, one may predict decreased contextual fear memory in hM4Di mice. However, we have also shown that silencing CA2 output with hM4Di increases hippocampal SWRs, which likely reflects release of CA2 inhibition over CA3 and therefore increased CA3 to CA1 activity (Alexander et al., 2018; Boehringer et al., 2017). Interestingly, hippocampal SWRs have been shown to significantly modulate neuronal firing in BLA during the SWR, with some BLA neurons positively modulated and some BLA neurons negatively modulated (Girardeau et al., 2017). Further, when rats were trained to traverse a linear track, those BLA neurons showing positive modulation by SWRs showed preferential involvement in post-training reactivation of place cell sequences representing the linear track. Finally, if the linear track included an aversive air puff in a specific location along the track, BLA neuron modulation was strongest during those post-training SWRs with place cell sequences representing the aversive area of the track. Therefore, consolidation of the learned association between contextual information and aversive stimuli may occur post-training during periods of SWRs via engagement of BLA neuron firing in concert with CA1 place cell reactivations (Girardeau et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2014). The increased occurrence of SWRs upon silencing of CA2 in our hM4Di animals may have provided greater opportunity for hippocampal-BLA engagement, especially in females, during place cell reactivations, thereby enhancing contextual fear memory consolidation. This idea remains to be tested. Our previous study of SWRs upon CA2 inhibition, which included both male and female mice, was underpowered to detect differences according to sex, so it is unclear whether SWRs may have contributed to the sex-dependent effect of inhibiting CA2 on fear conditioning. Alternatively, sex differences in CA3 dendritic spine density and dendritic changes in response to stress exposure (for review, see McEwen & Milner, 2017) may have been exacerbated by silencing of CA2 and subsequent disinhibition of CA3 neurons during fear conditioning, which may have contributed to sexually dimorphic behavioral outcomes.

Lastly, we sought to investigate behavioral responses to fear conditioning in a genetic mouse model targeting CA2, RGS14 KO mice. Normally, in wild-type mice, LTP of excitatory synapses onto CA2 neurons in stratum radiatum, where Schaffer collateral synapses from CA3 contact CA2 neurons, does not occur using typical protocols ( Zhao et al., 2007). In contrast, synaptic responses from RGS14 KO mice do show LTP (Lee et al., 2010). RGS14 KO mice also show increased CA2 neuron excitability (Lee et al., 2010). These previous findings motivated us to examine fear conditioning in RGS14 KO mice. Because CA2 neuronal activity is increased in RGS14 KO mice and in hM3Dq mice, with the caveat that the effects RGS14 KO would likely have been present since at least the time that RGS14 is first expressed (Evans, Lee, Smith, & Hepler, 2014), whereas hM3Dq mice have temporarily increased activity, we reasoned that if fear conditioning was affected in RGS14 KO mice, it would be affected in a manner similar to hM3Dq mice.

Fear conditioning experiments in RGS14 KO mice yielded yet another piece of evidence suggesting a sexually dimorphic role for CA2 in regulating fear behavior. RGS14 KO females showed increased cued fear conditioning compared with their WT littermates. Although increased freezing among females was not statistically significant during the first test of cued fear administered 48 hours after training, a strong trend showed a biologically meaningful increase in freezing. Indeed, more than 80% of the females exhibited freezing for more than 50% of the test period, but two female mice showed almost no freezing during the test, dramatically increasing the group variability while demonstrating the trend toward increased cued fear among females. In the test of cued fear measured two weeks after training, a significant increase in freezing was detected. Further, a main effect of genotype was found when comparing Test 1 and Test 2 (Fig. S11) showing that KO females froze significantly more in tests of cued fear than their WT littermates. These results further support the involvement of CA2 activity in amygdala-dependent processes such as memory for fearful stimuli (Maren, 2001).

Our most prominent finding is that the majority of the increases in freezing in response to fear conditioning among hM3Dq, hM4Di and RGS14 KO was limited to female mice. Certainly, these three independent findings suggest that CA2 inputs, outputs, modulators or other cellular properties may be sexually dimorphic. Although no studies, to our knowledge, have identified sex differences in these properties of CA2 neurons, sex differences in dendritic branching patterns of guinea pig CA2 neurons have been reported (Bartesaghi & Ravasi, 1999). As such, further sex differences may exist in CA2. Behaviorally, we previously found that silencing of CA2 synaptic output with hM4Di impaired social behavior selectively in male mice, with female mice showing no such impairment in social behavior upon CA2 silencing (Alexander et al., 2017). In fact, most behavioral studies investigating CA2 involvement in social behavior have used only males (Alexander et al., 2016; Hitti & Siegelbaum, 2014; Pagani et al., 2015; Smith, Williams Avram, Cymerblit-Sabba, Song, & Young, 2016; Stevenson & Caldwell, 2014; Wersinger, Ginns, O'Carroll, Lolait, & Young, 2002), so any sex-specific effects would have been missed. Given our previous and current sex-specific behavioral findings upon CA2 activation and inhibition, inclusion of both males and females in future studies of CA2 is warranted.

Given the higher prevalence of fear and anxiety disorders among females in the clinical population (Kessler, Petukhova, Sampson, Zaslavsky, & Wittchen, 2012) and our findings that modification of CA2 activity specifically affects fear conditioning in female mice, future studies should investigate whether any sex-specific interactions exist between CA2 and amygdala or other nodes of the fear circuit. For example, although not commonly associated with the fear circuit, locus coeruleus (LC) involvement in fear conditioning may differentially regulate fear conditioning in a sex-specific manner and may involve CA2. To elaborate, CA3, and possibly CA2, receive direct inputs from LC. Interestingly, these inputs have been shown to be important for contextual memory formation in males (Wagatsuma et al., 2018). LC is a sexually dimorphic structure, with LC dendrites longer and more complex in females than in males, and stress hormone receptor expression and function varying by sex (e.g., CRFR1; for review, see Bangasser, Wiersielis, & Khantsis, 2016). In addition, LC has reciprocal connections with the central amygdala, which receives inputs directly from the BLA, providing one potential route through which the sexually-dimorphic LC could contribute to the sex-specific effect of CA2 modulation on fear conditioning.

In conclusion, using three independent manipulations of CA2 neurons in mice, we provide evidence that CA2 neuronal activity plays a role in the behavioral responses to fear conditioning. Specifically, activating CA2 neurons during training increased cued fear conditioning in males and females, but increased contextual fear conditioning only in females. Similarly, inhibiting CA2 during training increased contextual fear conditioning in females, and females of a KO mouse line in which CA2 neurons have increased activity had increased long-term cued fear conditioning. These three separate lines of evidence suggest that CA2 neurons are actively involved in both intra- and extra-hippocampal brain processes and function to influence fear memory. Finally, the intriguing and consistent findings of enhanced fear conditioning only among female mice strongly implicate CA2 as a sexually-dimorphic structure.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Changes in CA2 activity has a sexually dimorphic effect on learned fear behavior

Increasing CA2 activity during training increased context freezing in females

Increasing CA2 activity during training increased cued freezing in males and females

Decreasing CA2 activity during training also increased context freezing in females

Female, but not male, RGS14 knock-out mice had increased cued freezing

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

This research is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the U.S. NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Z01 ES100221 to S.M.D.). The UNC Mouse Behavioral Phenotyping Laboratory is supported by U.S. NIH, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U54HD079124 to Joseph Piven). We wish to thank the Fluorescence Microscopy and Imaging Center, and the animal care staff at NIEHS for their support, and Jesse Cushman for comments and helpful discussion on the manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFEREN

- Alexander GM, Brown LY, Farris S, Lustberg D, Pantazis C, Gloss B, et al. (2018). CA2 neuronal activity controls hippocampal low gamma and ripple oscillations. eLife, 7, 27 10.7554/eLife.38052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GM, Farris S, Pirone JR, Zheng C, Colgin LL, & Dudek SM (2016). Social and novel contexts modify hippocampal CA2 representations of space. Nature Communications, 7, 10300 10.1038/ncomms10300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander G, Brown L, Farris S, Lustberg D, Pantazis C, Gloss B, et al. (2017). CA2 Neuronal Activity Controls Hippocampal Oscillations and Social Behavior. bioRxiv, 1–36. 10.1101/190504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpár A, Gärtner U, Härtig W, & Brückner G (2006). Distribution of pyramidal cells associated with perineuronal nets in the neocortex of rat. Brain Research, 1120(1), 13–22. 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balogh SA, & Wehner JM (2003). Inbred mouse strain differences in the establishment of long-term fear memory. Behavioural Brain Research, 140(1-2), 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee SB, Gutzeit VA, Baman J, Aoued HS, Doshi NK, Liu RC, & Ressler KJ (2017). Perineuronal Nets in the Adult Sensory Cortex Are Necessary for Fear Learning. Neuron, 95(1), 169–179.e3. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangasser DA, Wiersielis KR, & Khantsis S (2016). Sex differences in the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system and its regulation by stress. Brain Research, 1641(Pt B), 177–188. 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartesaghi R, & Ravasi L (1999). Pyramidal neuron types in field CA2 of the guinea pig. Brain Research Bulletin, 50(4), 263–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bast T, Zhang WN, & Feldon J (2001). The ventral hippocampus and fear conditioning in rats. Different anterograde amnesias of fear after tetrodotoxin inactivation and infusion of the GABA(A) agonist muscimol. Experimental Brain Research, 139(1), 39–52. 10.1007/s002210100746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bast T, Zhang W-N, & Feldon J (2003). Dorsal hippocampus and classical fear conditioning to tone and context in rats: effects of local NMDA-receptor blockade and stimulation. Hippocampus, 13(6), 657–675. 10.1002/hipo.10115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehringer R, Polygalov D, Huang AJY, Middleton SJ, Robert V, Wintzer ME, et al. (2017). Chronic Loss of CA2 Transmission Leads to Hippocampal Hyperexcitability. Neuron, 94(3), 642–655.e9. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstens KE, Phillips ML, Pozzo-Miller L, Weinberg RJ, & Dudek SM (2016). Perineuronal Nets Suppress Plasticity of Excitatory Synapses on CA2 Pyramidal Neurons. Journal of Neuroscience, 36(23), 6312–6320. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0245-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z, Gerfen CR, & Young WS (2013). Hypothalamic and other connections with dorsal CA2 area of the mouse hippocampus. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 521(8), 1844–1866. 10.1002/cne.23263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek SM, Alexander GM, & Farris S (2016). Rediscovering area CA2: unique properties and functions. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 17(2), 89–102. 10.1038/nrn.2015.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans PR, Lee SE, Smith Y, & Hepler JR (2014). Postnatal developmental expression of regulator of G protein signaling 14 (RGS14) in the mouse brain. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 522(1), 186–203. 10.1002/cne.23395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanselow MS, & Dong H-W (2010). Are the dorsal and ventral hippocampus functionally distinct structures? Neuron, 65(1), 7–19. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett JE, & Wellman CL (2009). Chronic stress effects on dendritic morphology in medial prefrontal cortex: sex differences and estrogen dependence. Neuroscience, 162(1), 195–207. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.04.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin MR, & Helmstetter FJ (2010). Trace and contextual fear conditioning require neural activity and NMDA receptor-dependent transmission in the medial prefrontal cortex. Learning & Memory (Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.), 17(6), 289–296. 10.1101/lm.1597410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin MR, Miyawaki H, Helmstetter FJ, & Diba K (2013). Prefrontal activity links nonoverlapping events in memory. Journal of Neuroscience, 33(26), 10910–10914. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0144-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardeau G, Inema I, & Buzsáki G (2017). Reactivations of emotional memory in the hippocampus-amygdala system during sleep. Nature Neuroscience, 20(11), 1634–1642. 10.1038/nn.4637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshen I, Brodsky M, Prakash R, Wallace J, Gradinaru V, Ramakrishnan C, & Deisseroth K (2011). Dynamics of retrieval strategies for remote memories. Cell, 147(3), 678–689. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmstetter FJ, & Bellgowan PS (1994). Effects of muscimol applied to the basolateral amygdala on acquisition and expression of contextual fear conditioning in rats. Behavioral Neuroscience, 108(5), 1005–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitti FL, & Siegelbaum SA (2014). The hippocampal CA2 region is essential for social memory. Nature, 508(7494), 88–92. 10.1038/nature13028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland PC (1977). Conditioned stimulus as a determinant of the form of the Pavlovian conditioned response. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Animal Behavior Processes, 3(1), 77–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsaker MR, & Kesner RP (2008). Dissociations across the dorsal-ventral axis of CA3 and CA1 for encoding and retrieval of contextual and auditory-cued fear. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 89(1), 61–69. 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay TM, & Witter MP (1991). Distribution of hippocampal CA1 and subicular efferents in the prefrontal cortex of the rat studied by means of anterograde transport of Phaseolus vulgaris-leucoagglutinin. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 313(4), 574–586. 10.1002/cne.903130404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung MW, Wiener SI, & McNaughton BL (1994). Comparison of spatial firing characteristics of units in dorsal and ventral hippocampus of the rat. The Journal of Neuroscience : the Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 14(12), 7347–7356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutras MJ, Fries P, & Buffalo EA (2009). Gamma-band synchronization in the macaque hippocampus and memory formation. Journal of Neuroscience, 29(40), 12521–12531. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0640-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiser AA, Turnbull LM, Darian MA, Feldman DE, Song I, & Tronson NC (2017). Sex Differences in Context Fear Generalization and Recruitment of Hippocampus and Amygdala during Retrieval. Neuropsychopharmacology : Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(2), 397–407. 10.1038/npp.2016.174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, & Wittchen H-U (2012). Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 21(3), 169–184. 10.1002/mpr.1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WB, & Cho J-H (2017). Synaptic Targeting of Double-Projecting Ventral CA1 Hippocampal Neurons to the Medial Prefrontal Cortex and Basal Amygdala. Journal of Neuroscience, 37(19), 4868–4882. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3579-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi T, Tsumori T, Yokota S, & Yasui Y (2006). Topographical projection from the hippocampal formation to the amygdala: a combined anterograde and retrograde tracing study in the rat. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 496(3), 349–368. 10.1002/cne.20919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohara K, Pignatelli M, Rivest AJ, Jung H-Y, Kitamura T, Suh J, et al. (2014). Cell type-specific genetic and optogenetic tools reveal hippocampal CA2 circuits. Nature Publishing Group, 17(2), 269–279. 10.1038/nn.3614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE, Sakaguchi A, Iwata J, & Reis DJ (1986). Interruption of projections from the medial geniculate body to an archi-neostriatal field disrupts the classical conditioning of emotional responses to acoustic stimuli. Neuroscience, 17(3), 615–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Wang C, Deshmukh SS, & Knierim JJ (2015). Neural Population Evidence of Functional Heterogeneity along the CA3 Transverse Axis: Pattern Completion versus Pattern Separation. Neuron, 87(5), 1093–1105. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SE, Simons SB, Heldt SA, Zhao M, Schroeder JP, Vellano CP, et al. (2010). RGS14 is a natural suppressor of both synaptic plasticity in CA2 neurons and hippocampal-based learning and memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(39), 16994–16998. 10.1073/pnas.1005362107/-/DCSupplemental/pnas.201005362SI.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Ramirez S, Pang PT, Puryear CB, Govindarajan A, Deisseroth K, & Tonegawa S (2012). Optogenetic stimulation of a hippocampal engram activates fear memory recall. Nature, 484(7394), 381–385. 10.1038/nature11028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Igarashi KM, Witter MP, Moser EI, & Moser M-B (2015). Topography of Place Maps along the CA3-to-CA2 Axis of the Hippocampus. Neuron, 87(5), 1078–1092. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mankin EA, Diehl GW, Sparks FT, Leutgeb S, & Leutgeb JK (2015). Hippocampal CA2 activity patterns change over time to a larger extent than between spatial contexts. Neuron, 85(1), 190–201. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S (2001). Neurobiology of Pavlovian fear conditioning. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 24(1), 897–931. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S, & Fanselow MS (1995). Synaptic plasticity in the basolateral amygdala induced by hippocampal formation stimulation in vivo. The Journal of Neuroscience : the Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 15(11), 7548–7564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S, & Fanselow MS (1996). The amygdala and fear conditioning: has the nut been cracked? Neuron, 16(2), 237–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S, & Holt WG (2004). Hippocampus and Pavlovian fear conditioning in rats: muscimol infusions into the ventral, but not dorsal, hippocampus impair the acquisition of conditional freezing to an auditory conditional stimulus. Behavioral Neuroscience, 118(1), 97–110. 10.1037/0735-7044.118.1.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlin NA (1981). Contextual associations in trace conditioning. Animal Learning Behavior, 9(4), 519–523. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, & Milner TA (2017). Understanding the broad influence of sex hormones and sex differences in the brain. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 95(1-2), 24–39. 10.1002/jnr.23809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinzie DL, & Spear NE (1995). Ontogenetic differences in conditioning to context and CS as a function of context saliency and CS-US interval. Animal Learning Behavior, 23(3), 304–313. [Google Scholar]

- Meira T, Leroy F, Buss EW, Oliva A, Park J, & Siegelbaum SA (2018). A hippocampal circuit linking dorsal CA2 to ventral CA1 critical for social memory dynamics. Nature Communications, 9(1), 4163 10.1038/s41467-018-06501-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer A, Trigg HL, & Thomson AM (2007). Characterization of neurons in the CA2 subfield of the adult rat hippocampus. Journal of Neuroscience, 27(27), 7329–7338. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1829-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser EI, Kropff E, & Moser M-B (2008). Place cells, grid cells, and the brain's spatial representation system. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 31(1), 69–89. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.061307.090723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser MB, & Moser EI (1998). Functional differentiation in the hippocampus. Hippocampus, 8(6), 608–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller J, Corodimas KP, Fridel Z, & LeDoux JE (1997). Functional inactivation of the lateral and basal nuclei of the amygdala by muscimol infusion prevents fear conditioning to an explicit conditioned stimulus and to contextual stimuli. Behavioral Neuroscience, 111(4), 683–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawa N, Saitoh Y, Suzuki A, Tsujimura S, Murayama E, Kosugi S, et al. (2015). Artificial association of pre-stored information to generate a qualitatively new memory. Cell Reports, 11(2), 261–269. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuyama T, Kitamura T, Roy DS, Itohara S, & Tonegawa S (2016). Ventral CA1 neurons store social memory. Science (New York, N.Y.), 353(6307), 1536–1541. 10.1126/science.aaf7003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagani JH, Zhao M, Cui Z, Avram SKW, Caruana DA, Dudek SM, & Young WS (2015). Role of the vasopressin 1b receptor in rodent aggressive behavior and synaptic plasticity in hippocampal area CA2. Molecular Psychiatry, 20(4), 490–499. 10.1038/mp.2014.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel J, Schomburg EW, Berényi A, Fujisawa S, & Buzsáki G (2013). Local Generation and Propagation of Ripples along the Septotemporal Axis of the Hippocampus. The Journal of Neuroscience : the Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 33(43), 17029–17041. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2036-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen NP, Ferrari L, Venner A, Wang JL, Abbott SBG, Vujovic N, et al. (2017). Supramammillary glutamate neurons are a key node of the arousal system. Nature Communications, 3(1), 1405 10.1038/s41467-017-01004-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RG, & LeDoux JE (1992). Differential contribution of amygdala and hippocampus to cued and contextual fear conditioning. Behavioral Neuroscience, 106(2), 274–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkänen A, Pikkarainen M, Nurminen N, & Ylinen A (2000). Reciprocal connections between the amygdala and the hippocampal formation, perirhinal cortex, and postrhinal cortex in rat. A review. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 911, 369–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raam T, McAvoy KM, Besnard A, Veenema AH, & Sahay A (2017). Hippocampal oxytocin receptors are necessary for discrimination of social stimuli. Nature Communications, 8(1), 2001 10.1038/s41467-017-02173-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogan MT, Stäubli UV, & LeDoux JE (1997). Fear conditioning induces associative long-term potentiation in the amygdala. Nature, 390(6660), 604–607. 10.1038/37601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AS, Williams Avram SK, Cymerblit-Sabba A, Song J, & Young WS (2016). Targeted activation of the hippocampal CA2 area strongly enhances social memory. Molecular Psychiatry, 21(8), 1137–1144. 10.1038/mp.2015.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spellman T, Rigotti M, Ahmari SE, Fusi S, Gogos JA, & Gordon JA (2015). Hippocampal-prefrontal input supports spatial encoding in working memory. Nature, 522(7556), 309–314. 10.1038/nature14445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson EL, & Caldwell HK (2014). Lesions to the CA2 region of the hippocampus impair social memory in mice. The European Journal of Neuroscience, 40(9), 3294–3301. 10.1111/ejn.12689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamaki N, Abe K, & Nojyo Y (1988). Three-dimensional analysis of the whole axonal arbors originating from single CA2 pyramidal neurons in the rat hippocampus with the aid of a computer graphic technique. Brain Research, 452(1-2), 255–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka KZ, Pevzner A, Hamidi AB, Nakazawa Y, Graham J, & Wiltgen BJ (2014). Cortical representations are reinstated by the hippocampus during memory retrieval. Neuron, 84(2), 347–354. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.09.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonegawa S, Pignatelli M, Roy DS, & Ryan TJ (2015). Memory engram storage and retrieval. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 35, 101–109. 10.1016/j.conb.2015.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagatsuma A, Okuyama T, Sun C, Smith LM, Abe K, & Tonegawa S (2018). Locus coeruleus input to hippocampal CA3 drives single-trial learning of a novel context. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(2), E310–E316. 10.1073/pnas.1714082115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wersinger SR, Ginns EI, O'Carroll A-M, Lolait SJ, & Young WS III. (2002). Vasopressin V1b receptor knockout reduces aggressive behavior in male mice. Molecular Psychiatry, 7(9), 975–984. 10.1038/sj.mp.4001195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltgen BJ, Sanders MJ, Anagnostaras SG, Sage JR, & Fanselow MS (2006). Context fear learning in the absence of the hippocampus. Journal of Neuroscience, 26(20), 5484–5491. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2685-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yiu AP, Mercaldo V, Yan C, Richards B, Rashid AJ, Hsiang H-LL, et al. (2014). Neurons are recruited to a memory trace based on relative neuronal excitability immediately before training. Neuron, 83(3), 722–735. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]