Protein concentration gradients play a relevant role in the organization of the bacterial cell. The Caulobacter crescentus protein OmpA2 forms an outer membrane polar concentration gradient. To understand the molecular mechanism that determines the formation of this gradient, we characterized the mobility and localization of the full protein and of its two structural domains an integral outer membrane β-barrel and a periplasmic peptidoglycan binding domain. Each domain has a different role in the formation of the OmpA2 gradient, which occurs in two steps. We also show that the OmpA2 outer membrane β-barrel can diffuse, which is in contrast to what has been reported previously for several integral outer membrane proteins in Escherichia coli, suggesting a different organization of the outer membrane proteins.

KEYWORDS: Caulobacter crescentus, FRAP, cell wall, limited diffusion, outer membrane, protein concentration gradient

ABSTRACT

OmpA-like proteins are involved in the stabilization of the outer membrane, resistance to osmotic stress, and pathogenesis. In Caulobacter crescentus, OmpA2 forms a physiologically relevant concentration gradient that forms by an uncharacterized mechanism, in which the gradient orientation depends on the position of the gene locus. This suggests that OmpA2 is synthesized and translocated to the periplasm close to the position of the gene and that the gradient forms by diffusion of the protein from this point. To further understand how the OmpA2 gradient is established, we determined the localization and mobility of the full protein and of its two structural domains. We show that OmpA2 does not diffuse and that both domains are required for gradient formation. The C-terminal domain binds tightly to the cell wall and the immobility of the full protein depends on the binding of this domain to the peptidoglycan; in contrast, the N-terminal membrane β-barrel diffuses slowly. Our results support a model in which once OmpA2 is translocated to the periplasm, the N-terminal membrane β-barrel is required for an initial fast restriction of diffusion until the position of the protein is stabilized by the binding of the C-terminal domain to the cell wall. The implications of these results on outer membrane protein diffusion and organization are discussed.

IMPORTANCE Protein concentration gradients play a relevant role in the organization of the bacterial cell. The Caulobacter crescentus protein OmpA2 forms an outer membrane polar concentration gradient. To understand the molecular mechanism that determines the formation of this gradient, we characterized the mobility and localization of the full protein and of its two structural domains an integral outer membrane β-barrel and a periplasmic peptidoglycan binding domain. Each domain has a different role in the formation of the OmpA2 gradient, which occurs in two steps. We also show that the OmpA2 outer membrane β-barrel can diffuse, which is in contrast to what has been reported previously for several integral outer membrane proteins in Escherichia coli, suggesting a different organization of the outer membrane proteins.

INTRODUCTION

The Gram-negative cell envelope consists of an inner or cytoplasmic membrane (IM), a peptidoglycan cell wall, and an outer membrane (OM) (1). As it occurs with the IM, the OM is constantly being pushed outward by the osmotic pressure of the cell (2). To keep the OM from blebbing out, several proteins bind the OM to the cell wall (3–9). One of these proteins is OmpA, which in Escherichia coli is one of the most abundant integral outer membrane proteins (OMPs). This protein has two structural domains, namely, a variable N-terminal integral OM β-barrel domain and a C-terminal peptidoglycan binding domain (PBD); these domains are linked via an Ala-Pro-rich region (7, 10, 11). Crystallographic data from the Acinetobacter baumannii OmpA periplasmic domain showed that the PBD binds to the diaminopimelic amino acid present in the peptide of the cell wall, noncovalently tethering the OM to the cell wall (12).

Caulobacter crescentus is a free-living Gram-negative bacterium with a dimorphic cell cycle that starts with a motile nondividing cell that has a single polar flagellum. This cell differentiates into a sessile cell, losing its flagellum and producing at the same position a thin extension of the cell envelope known as the stalk (13). The chromosome of C. crescentus is linearly organized within the cell, with the replication origin located at the old (stalked) pole and the terminus near the new pole (14, 15). The genome of C. crescentus has two ompA genes, both of which are located near the replication origin and, in consequence, near the old cell pole. In a previous work, we showed that the highly expressed OmpA2 protein forms a concentration gradient from the stalk to the new cell pole. This localization pattern depends on the position of the ompA2 gene in the chromosome and starts forming when the cells are in the swarmer stage, becoming stronger as the cell progresses through the cell cycle and as it ages.

Protein gradients in bacteria are rare but they play an important role in their organization (16). In C. crescentus, the presence of OmpA2 and the orientation of its concentration gradient are relevant for the cell physiology and for the synthesis of the stalk (17). Although OMPs are a major component of the OM, there is scarce information about their localization and mobility (18). In E. coli, naturally abundant or overexpressed OMPs show an even distribution (19, 20), whereas less abundant proteins have been shown to localize in patches (18, 19, 21, 22) or in particular cases at the cell pole (23). These patches have been suggested to be organized in spirals (24). In contrast with integral inner membrane proteins, experiments of fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) have shown that OMPs and the lipopolysaccharide do not diffuse (20, 25). In E. coli, OmpA expressed from a plasmid evenly localizes in the OM and does not exhibit long-range diffusion (>∼100 nm), even in the absence of its PBD (20). Single-molecule tracking using different labeling techniques has revealed that OMPs can only move inside confined regions and do not show long-range diffusion. This phenomenon as well as the absence of diffusion of abundant OMPs has been proposed to be caused by promiscuous interactions between OMPs (19–21, 24, 26). Integration of newly synthesized OMPs in the OM is accomplished by the BAM complex (27). BAM complexes have been suggested to be arranged in groups of 4 to 6 distributed across the cell, and at least one-third of the OMP patches have colocalized with a BAM complex (21, 22). This organization has led to the suggestion that the BAM complexes form functional assembly precincts in the OM. The assembly precincts are displaced from the middle to the poles of growing cells as new compartments take their place (20, 21, 24, 28, 29). These different reports suggest that the absence of diffusion is common for OMPs and that their restricted mobility in the OM is caused by the β-barrel.

In this work, we show that formation of the OmpA2 gradient depends on both of its domains since the β-barrel and PBD by themselves are unable to form it. Using FRAP assays, we show that the full-length OmpA2 protein does not diffuse and that its immobility is caused by the PBD. Point mutants of the PBD in amino acids involved in peptidoglycan binding showed that the binding of OmpA2 to the peptidoglycan is necessary for localization. Our results suggest that after OmpA2 is translocated to the periplasm, the OmpA2 gradient forms during a brief period of diffusion restricted by the N-terminal β-barrel until the gradient is stabilized by the interaction of the OmpA2-PBD with the cell wall.

(This study was conducted by L. D. Ginez in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Doctorado en Ciencias Biomédicas degree from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.)

RESULTS

Both OmpA2 structural domains are necessary for gradient formation.

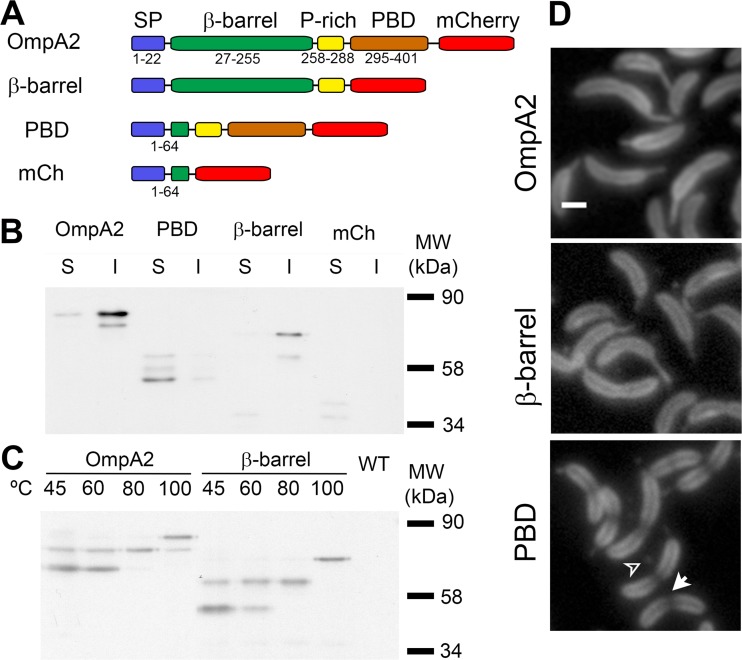

In our previous work, we showed that in C. crescentus, OmpA2 forms a concentration gradient from the early stages of the cell cycle and it becomes stronger as the cell grows and ages (17). To evaluate the contribution of each of the OmpA2 structural domains to the formation of the gradient, we substituted the wild-type ompA2 allele with truncated versions that consisted of only the β-barrel or the C-terminal PBD of OmpA2 fused to the mCherry (mCh) fluorescent protein (Fig. 1A). It should be noted that both proteins were expressed from the same promoter and gene locus and had the same signal peptide as the wild-type protein. The first β-strand of the OmpA2 β-barrel that is just after the predicted signal peptide was included for the PBD-mCh fusion, because without it the fusion protein was not detectable. The stability and subcellular localization of both truncated OmpA2 versions as well as the insertion of the β-barrel in the OM were verified (Fig. 1B and C). As a control, the mCherry protein was fused with the same OmpA2 signal peptide present in the PBD-mCh fusion (Fig. 1A). After cell fractionation (Fig. 1B), we detected two bands for periplasmic mCherry in the soluble fraction. The molecular weight of the most abundant population corresponds to the processed protein without the β-strand. This result shows the OmpA2 β-strand is not enough to recruit mCherry to the inner or outer membrane. Both OmpA2 truncated proteins were stable, and as expected, the β-barrel–mCh fusion was in the insoluble fraction while the PBD-mCh fragment was soluble. We detected several bands for the full-length OmpA2-mCh protein and the truncated versions. For the full and the β-barrel–mCh proteins, the low molecular weight bands are probably the result of partial unfolding, as it has been reported for other integral OMPs (30–35). For the PBD-mCh protein, the less abundant forms are probably caused by the degradation of the β-strand (Fig. 1A) and the proteolysis of the signal peptide. A similar pattern was observed for the periplasmic mCherry.

FIG 1.

OmpA2 requires both structural domains to form its concentration gradient. The localization, stability, subcellular localization, and folding of the full OmpA2 fluorescent fusion and of the truncated version are shown. (A) Schematic representation of the fluorescent fusions. The length (in residues) is indicated. Periplasmic mCherry was expressed from the vanA promoter. SP, signal peptide; P-rich, proline rich linker. (B) Western blot of the soluble (S) and insoluble (I) fractions obtained from cell cultures expressing the proteins indicated in the figure. The following indicated molecular weights correspond to mature proteins: OmpA2-mCh (67 kDa), PBD-mCh (45 kDa), β-barrel–mCh (57 kDa), and periplasmic mCherry (30 kDa). (C) Western blot showing the unfolding pattern of OmpA2 and the β-barrel at the indicated temperatures. Both Western blots were revealed with anti-mCherry antibody. (D) Florescence images of cells expressing the indicated fluorescent fusion (OmpA2, OmpA2-mCh, strain LDG1; PBD, PBD-mCh, strain LDG4; β-barrel, β-barrel–mCh, strain LDG3; mCh, periplasmic mCherry, strain LDG5). The arrow in the PBD panel indicates an area with a reduced amount of the protein around the cell division site, and the arrowhead indicates outer membrane vesicles. Cells were grown in PYE to a 0.3 OD660. Scale bar indicates 1 μm.

To confirm that the β-barrel–mCh fusion was correctly inserted in the OM, we took advantage of the heat modifiability and the anomalous mobility of β-barrels in SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1C). In E. coli, the mCherry protein denatures at around 60°C and the OmpA β-barrel unfolds above 80°C (20), allowing the identification of the two β-barrels. We incubated total extracts from strains expressing OmpA2-mCh or the β-barrel–mCh fusions at different temperatures from 45 to 100°C for 15 min. Since both proteins contain two β-barrels, we observed three different bands resulting from the successive denaturation of the fluorescent protein and the membrane domain. Since the truncated version has the same heat modifiability as the OmpA2-mCh protein, we conclude that the β-barrel–mCh fusion is properly assembled in the OM.

The localization of the truncated OmpA2 versions showed that neither of them was able to form a gradient (Fig. 1D), indicating that the formation of the gradient depends on the properties of both domains. Since no wild-type OmpA2 protein was present in the strains expressing the truncated OmpA2 versions, in both cases we observed the presence of outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) (Fig. 1D, arrowhead). Interestingly, cells expressing the PBD-mCh fusion showed a region of reduced fluorescence around the division sites in divisional cells (Fig. 1D, arrow).

OmpA2 is an immobile outer membrane protein.

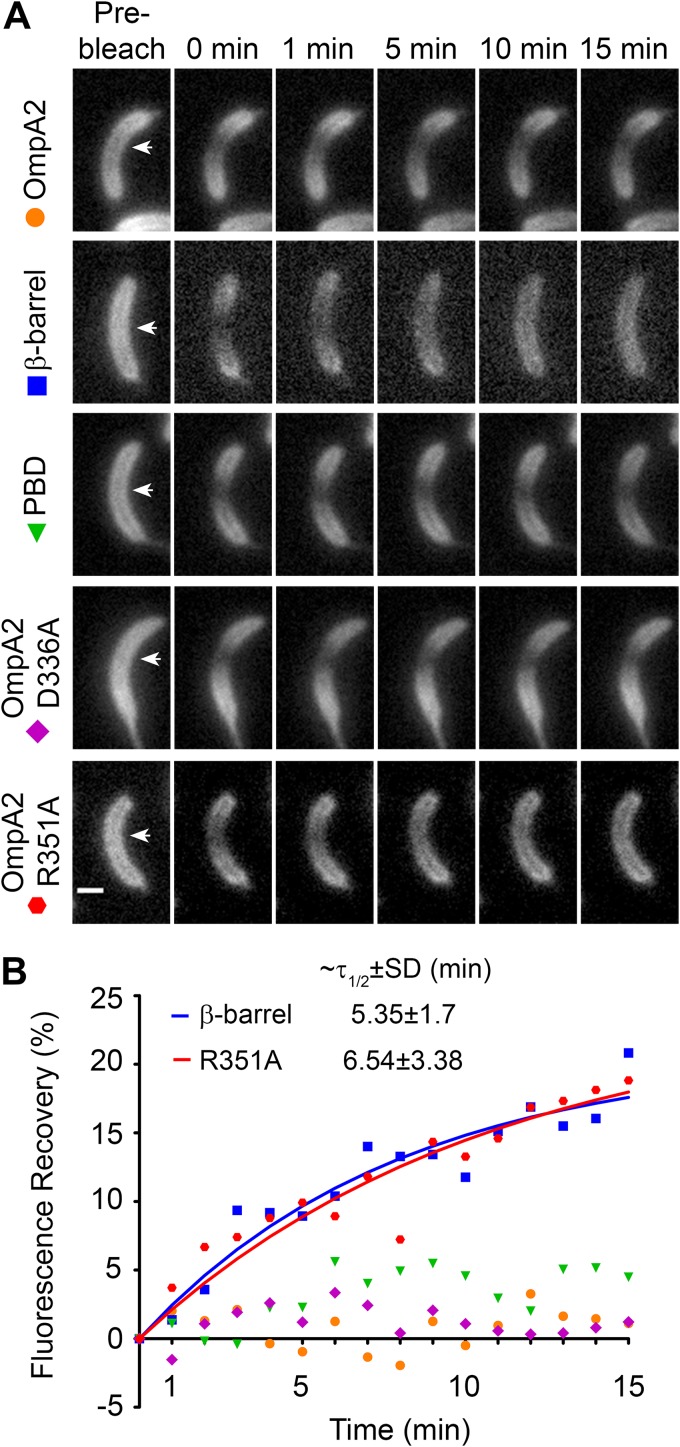

The establishment of the OmpA2 concentration gradient could be the result of continuous diffusion of the protein after its polar insertion in the OM. For this reason, we decided to evaluate the mobility of OmpA2 in a FRAP experiment. For bacteria, this technique is usually done with filamented cells obtained by treatment with antibiotics that inhibit cell division (20, 25, 36). Here, we used slightly filamented cells obtained by depleting the essential division protein FtsZ. In the absence of FtsZ, C. crescentus cells can grow and replicate their chromosomes, but they do not divide, becoming filaments. In these elongated cells, OmpA2-mCh formed a concentration gradient from both cell poles (Fig. 2A). This localization pattern could be explained by the expression of OmpA2-mCh from the two opposite ompA2 loci stabilized at the polar positions by the interaction of the ParB/C complex with PopZ (37), by the dilution of the fusion protein in the rest of the cell caused by cell growth, or by the diffusion of the protein from both poles toward the rest of the cell. After FtsZ depletion, we inhibited translation by adding chloramphenicol and spectinomycin. To determine the diffusion of OmpA2-mCh, we photobleached two regions with different protein concentrations, near the cell pole (not shown), or at the middle of the filament (Fig. 2A, first row). In both cases, we did not detect any fluorescence recovery, even after long time periods (15 min) (Fig. 2A and B, orange dots). To rule out cell damage caused by the laser during photobleaching, we evaluated the diffusion of periplasmic mCherry and the diffusion of FtsN in the IM. FtsN is a division protein with a transmembrane α-helix, and in the absence of FtsZ, it distributes evenly. Under the same experimental conditions, periplasmic mCherry and FtsN maintained their free mobility and the fluorescence recovery was fast, with a recovery half time of less than 10 s (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Our results show that OmpA2 is an immobile OMP in C. crescentus and suggest that the concentration gradient is formed by the diffusion of the protein before its position is stabilized.

FIG 2.

Mobility of OmpA2 and its truncated or point mutant versions. The mobility of the full OmpA2-mCh protein, the two domains fused to mCherry, and the single amino acid variants in the PBD domain of the full protein (OmpA2D336A-mCh and OmpA2R351A-mCh) was determined in FRAP experiments. (A) FRAP assays in filamented cells obtained by FtsZ depletion and treated to inhibit protein synthesis (OmpA2, OmpA2-mCh, strain LDG7; β-barrel, β-barrel–mCh, strain LDG8; PBD, PBD-mCh, strain LDG9; OmpA2 D336A, OmpA2D336A, strain LDG22; and OmpA2 R351A, OmpA2R351A, strain LDG23). Representative cells in different times after photobleaching are shown. Arrows in the first column indicate the selected area for photobleaching. The scale bar indicates 1 μm. (B) Quantification of the fluorescence recovery after photobleaching. The scattered symbols show the recovery of the cells in (A), and the continuous lines show the fitting of the signal of the cells that show recovery (see Materials and Methods for more details). The fluorescence level in the bleached area after the photobleaching (0 minutes) was used as basal level. The t1/2 values for β-barrel–mCh and OmpA2R351A-mCh are indicated in the plot and correspond to the mean for at least 10 cells from independent experiments.

Position maintenance of OmpA2 depends on its peptidoglycan binding domain.

OmpA2 diffusion could be restricted by its interaction with the cell wall or, since in E. coli OMPs do not diffuse, by the insertion of the β-barrel in the OM. However, the even distribution of the β-barrel–mCh and PBD-mCh fusions (Fig. 1D) suggests that these domains freely diffuse through the cell. To determine if this was the case, we performed FRAP on filamented cells expressing these proteins. The stability and subcellular localization of the protein fusions in the filamented cells as well as the viability of these cells were verified (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). As expected, both truncated proteins localize evenly in the FtsZ-depleted cells (Fig. 2A), as was observed in the unfilamented cells. After photobleaching, we detected fluorescence recovery only for the β-barrel–mCh fusion (Fig. 2A and B, squares). Adjusting the experimental data to a single-exponential equation (Fig. 2B, blue line), we calculated a recovery half-life (t1/2) of 5.35 ± 1.7 min and a diffusion constant of (2.7 ± 2) × 10−4 μm2/s for this truncated protein. In contrast, the OmpA2 PBD does not diffuse (Fig. 2A and B, triangles). Additionally, our data suggest that there is practically no free OmpA2-mCh and PBD-mCh protein since the fluorescence of the cells outside the bleached regions practically did not change (11.7% ± 7.9% and 12.4% ± 7.2% decrease for OmpA2 and the PBD, respectively), while for the β-barrel, it decreased 33.2% ± 19%. These results indicate that the diffusion of OmpA2 is mainly restricted by the binding of the protein to the cell wall and that absence of diffusion is not enough to establish the gradient.

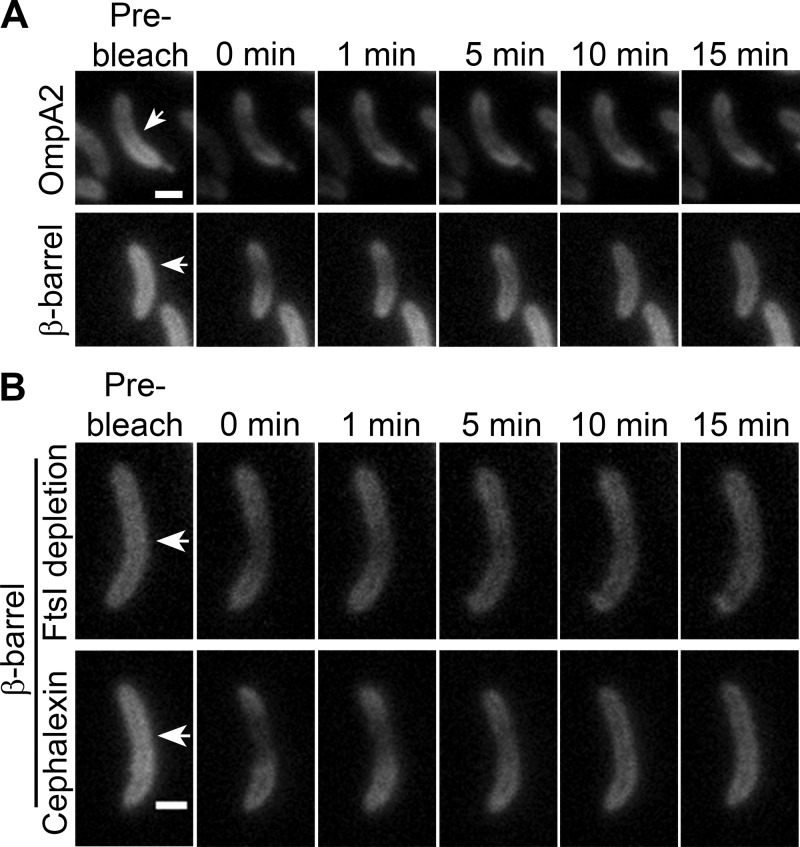

Diffusion of the OmpA2 β-barrel in the OM is not caused by FtsZ depletion.

In order to rule out that the diffusion of the OmpA2 β-barrel was caused by an abnormal condition of the OM induced by FtsZ depletion, we decided to evaluate the diffusion of OmpA2 and its truncated versions in unfilamented cells. Although the photobleached area occupied almost half the cell, we were able to determine that, in agreement with our previous results, the β-barrel–mCh fusion diffuses while the full protein is immobile (Fig. 3A). For FRAP experiments on bacteria, cells are frequently filamented by preventing division with the penicillin binding protein (PBP3 or FtsI), inhibiting antibiotic cephalexin (38). The main difference between cell filaments obtained by FtsZ depletion and cephalexin treatment is that in the last ones the divisome still forms. To determine if the presence of the divisome influenced the mobility of the OmpA2 β-barrel, we evaluated its diffusion in filamented cells obtained by the depletion of FtsI or by treatment with cephalexin (Fig. 3B). FRAP experiments showed that in filamented cells obtained by both methods, the OmpA2 β-barrel still diffuses (Fig. 3B), with recovery half times of 5.98 ± 4.18 and 4.5 ± 1.6 min for FtsI-depleted and cephalexin-treated cells (diffusion constants of [4.6 ± 2] × 10−4 μm2/s and [4.4 ± 2] × 10−4 μm2/s), respectively. Unexpectedly, we did observe that longer filamentation reduced the mobility of the OmpA2 β-barrel in FtsZ-depleted cells (recovery half time of 9.82 ± 3.8 min), and in FtsI-depleted or cephalexin-treated cells, it was completely abolished (see Fig. S3A and B in the supplemental material). The viability, as well as the FRAP of periplasmic mCherry and of mCherry fused to the inner membrane protein FtsN, was not affected in these cells (Fig. S1 and S2).

FIG 3.

Diffusion of the OmpA2 β-barrel is not caused by FtsZ depletion. The mobility of the complete OmpA2 protein and of the β-barrel were determined in unfilamented cells and for the β-barrel in cells filamented by FtsI depletion or cephalexin treatment. (A) FRAP assays of OmpA2 (OmpA2-mCh) and the β-barrel (β-barrel–mCh) in unfilamented cells. (B) FRAP of the β-barrel–mCh in filaments obtained by the FtsI depletion or the cephalexin treatment. Protein synthesis was inhibited as in the experiments in Fig. 2. Arrows in the first column indicate the selected area for photobleaching. The t1/2 values for the β-barrel in FtsI and cephalexin filaments are indicated in the text.

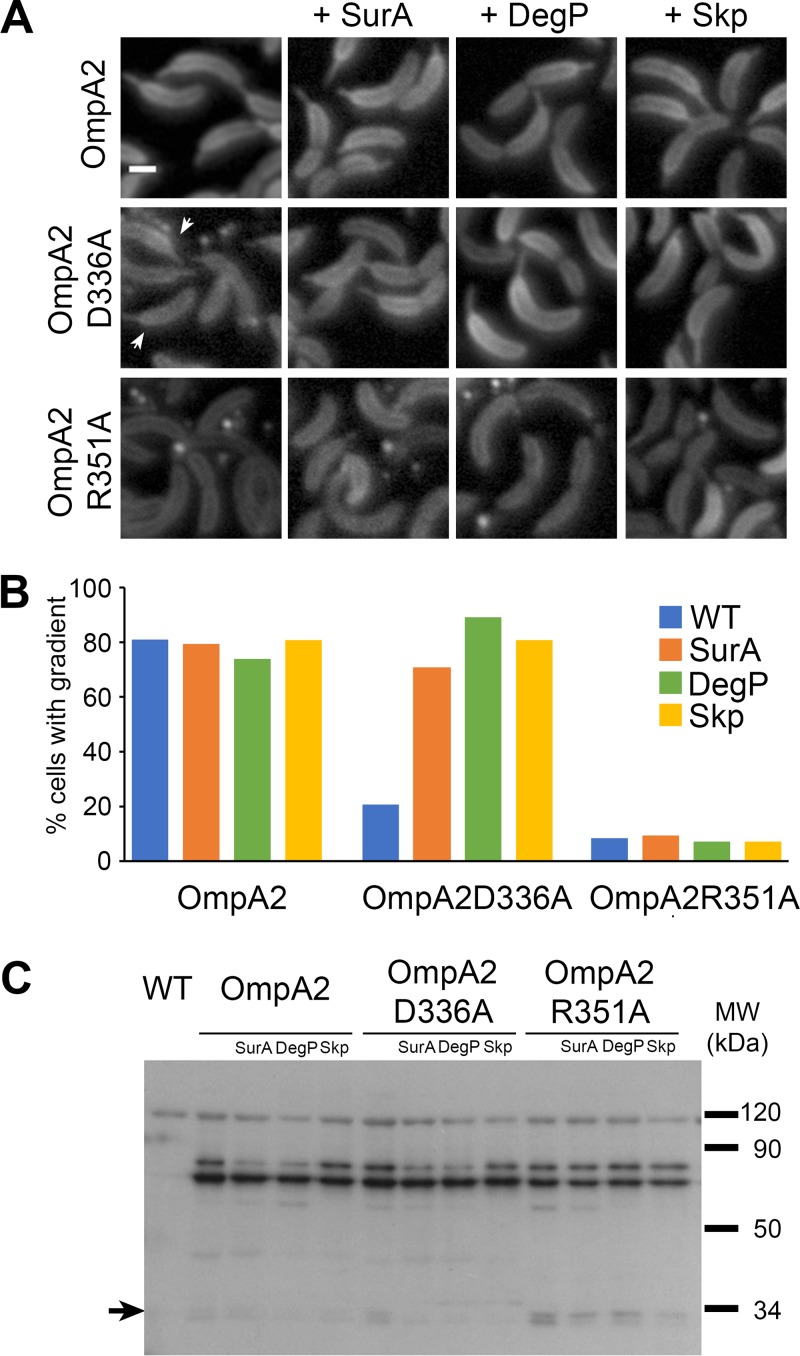

Binding of OmpA2 to the cell wall is important for protein stability and gradient formation.

The even distribution of the β-barrel observed in Fig. 1 shows that the PBD is relevant for the formation of the concentration gradient. To test if PG binding by the PBD or other possible interactions made by this domain were necessary for gradient formation, we substituted for alanine two conserved residues in OmpA2 (D336 and R351) (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material) that crystallographic and calorimetric data of the A. baumannii OmpA PBD have shown to be essential for binding to the peptidoglycan (PG) (12). Both OmpA2-mCh variants (OmpA2D336A and OmpA2R351A), distributed evenly (Fig. 4A), but a few cells expressing OmpA2D336A showed a weak protein gradient (Fig. 4A, arrows, and B). The cells expressing any of the ompA2-mCh point mutant versions as the unique ompA2 copy abundantly produced OMVs (Fig. 4A, first row). A Western blot showed that both proteins carrying these single amino acid substitutions were also slightly unstable (Fig. 4C), suggesting that not only their ability to bind PG but also their folding was affected. It has been suggested that the presence of misfolded proteins in the periplasm induces the formation of OMVs (39); this could explain the increased presence of OMVs in the strains expressing the OmpA2 point mutants. In agreement with these results, it was recently shown that substrate binding (diaminopimelic acid) was required for complete folding of the A. baumannii OmpA PBD (40). Since a partially folded PBD domain could be losing its ability to interact with other proteins, we overexpressed the SurA, DegP, or Skp periplasmic chaperones since in E. coli these chaperones assist OMP folding in the periplasm (41). The overexpression of any of these chaperones in the strain carrying the wild-type OmpA2-mCh protein did not affect or improve the gradient (Fig. 4A and B). In the case of the cells expressing OmpA2D336A, the protein instability (Fig. 4C) and OMV formation were considerably reduced by these chaperones, but it only fully recovered its competence to form a gradient in the strains overexpressing DegP or Skp, since, although the overexpression of SurA almost restored the number of cells with a gradient, the gradient was less evident (Fig. 4A and B). In contrast, although the OmpA2R351A protein stability improved with the chaperones and, in particular, with the overexpression of Skp (Fig. 4C), OmpA2R351A remained homogeneously localized and the cells continued forming OMVs, although at a smaller amount (Fig. 4A). To directly evaluate if the protein variants with these conserved amino acids are still able to bind PG, we performed FRAP assays in FtsZ-depleted cells. To our surprise, both protein variants behaved in the FtsZ-depleted cells in the same way as in the cells overexpressing the chaperones, i.e., the D336A variant was able to form a gradient, while the R351A was not (Fig. 2A), and the protein stability also improved in the FtsZ-depleted cells (Fig. S2A). Given that the β-barrel by itself can diffuse, we expected a slow mobility of the proteins not able to interact with the PG. As expected from the localization of the proteins, OmpA2D336A did not show any fluorescence recovery and OmpA2R351A showed a recovery half time similar to that of the β-barrel (t1/2 of 6.54 ± 3.38 min and diffusion constant of [2.7 ± 1.5] × 10−4 μm2/s) (Fig. 2B). These results show that the protein stability of the OmpA2 single amino acid variants can be restored, but the gradient only forms when the PBD can bind to the cell wall, indicating that a stable interaction with the PG and not the presence of the PBD is responsible for the protein immobility necessary for stabilization of the protein gradient. In addition, the PG-binding-induced folding of the PBD is important for protein stability; in fact, the R351 residue establishes crucial interactions with the PG that cannot be compensated by the activity of the chaperones. Further supporting this point, the product of the ompA2 double point mutant allele replacing both D336 and R351 by alanine was degraded and could not be rescued by the overexpression of the SurA, DegP, or Skp periplasmic chaperones, indicating that substrate binding is indispensable for the correct folding of the PBD. In contrast with the full protein, when the single point mutations were introduced in the PDB-mCh fusion, the resulting proteins were degraded even when the chaperones were overexpressed, indicating that the stability of the single amino acid full-length protein variants greatly depends on the presence of the β-barrel.

FIG 4.

Binding of OmpA2 to PG is essential for gradient formation. The localization and stability of two OmpA2 point mutants were tested in wild-type and chaperone-overexpressing cells (A) Cells expressing OmpA2-mCh or the point mutants OmpA2D336A or OmpA2R351A fused to mCherry in a wild-type background (first column, strains LDG1, LDG11, and LDG12), in cells overexpressing SurA (second column, strains LDG13, LDG16, and LDG19), in cells overexpressing DegP (third column, strains LDG14, LDG17, and LDG20), and in cells overexpressing Skp (fourth column, strains LDG15, LDG18, and LDG21). Arrows indicate cells with a weak gradient in the cells expressing OmpA2D336A. (B) Quantification of the number of cells showing a gradient. The percentage of cells showing a gradient was determined for the strains shown in panel A. The percentages were obtained from at least 100 cells. (C) Western blot α-mCherry showing the stability of OmpA2 point mutants in wild-type and chaperone-overexpressing cells. The arrow indicates the degradation product of the fluorescent fusions (free mCherry). Scale bar = 1 μm.

Newly synthesized OmpA2 preferentially appears at the old cell pole.

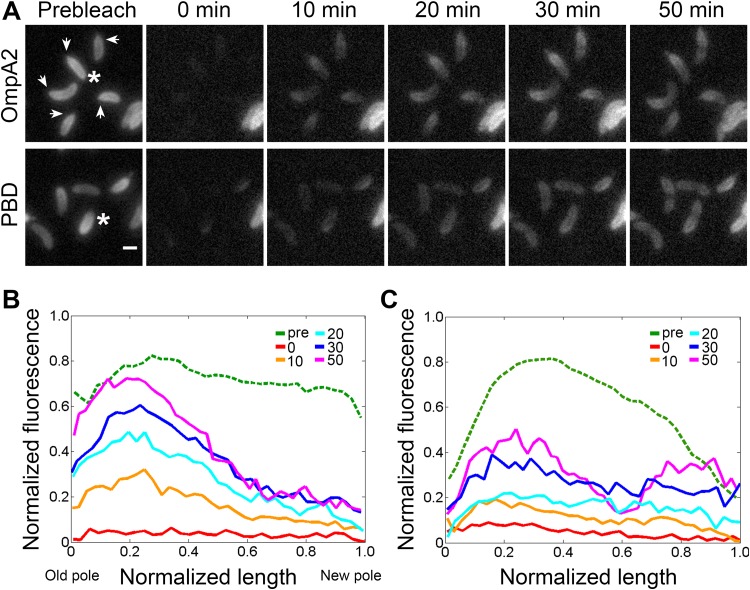

The OmpA2 gradient can be clearly seen in old cells (Fig. 1D); however, the profile of the gradient in these cells has been modified by different cellular processes like cell growth and division. If the protein does not diffuse, these processes can generate a gradient, as it can be observed for the PBD-mCh protein (Fig. 1D and 5A). To obtain a better profile of the OmpA2 gradient, we bleached the whole cell body of growing swarmer cells expressing OmpA2-mCh and then determined the appearance of newly synthesized protein by following the fluorescence in single cells (Fig. 5A, top image series). After bleaching, we observed the gradual recovery of fluorescence and the appearance of a gradient at the old pole detectable 10 minutes after bleaching (Fig. 5B), indicating that the OmpA2-mCh protein is being retained and eventually integrated at the stalked pole. After 30 minutes, the shape of the gradient can clearly be seen showing its highest concentration around the first quarter of the cell, decreasing from this point until it is barely detectable at the opposite pole. The fact that after 30 minutes there is practically no fluorescence recovery at the new pole confirms a limited diffusion of OmpA2 from the moment that it is synthesized in the cytoplasm until its position is stabilized by binding of the PBD to the cell wall. In contrast with the full protein, the fluorescence of bleached cells expressing the PBD-mCh protein was recovered at the same rate along the cell for the first 30 minutes and after that the PBD-mCh is displaced from the division site, creating a dip in the protein concentration (Fig. 5A, bottom picture series, and C). After division, the daughter cells show a protein gradient (Fig. 5A, bottom row, first panel). These results indicate that the OmpA2 gradient is not the result of cell growth or cell division. Since it is likely that the PBD is also being translocated to the periplasm near the cell pole, given that the PBD and full protein fluorescent fusions have the same signal peptide and are expressed from the same position in the chromosome, this result also suggests that the binding of the PBD to the cell wall occurs slowly, giving the protein enough time to diffuse through the periplasm.

FIG 5.

Pattern of appearance of newly synthesized OmpA2 and PBD proteins. The fluorescence pattern of synchronized single cells expressing OmpA2-mCh or PBD-mCh was recorded after complete bleaching. (A) Time lapse of cells expressing OmpA2 (strain LDG24) or PBD-mCh (strain LDG4). Fluorescence was bleached in the whole cell body, and the appearance of newly synthesized protein was followed. Arrows in the prebleach image of the strain expressing OmpA2-mCh indicate the old cell poles assigned by the localization of MipZ-YFP (not shown). The scale bar represents 1 μm. (B and C) Fluorescence intensity profiles of representative cells (marked with asterisks in panel A) expressing OmpA2-mCh or the PBD-mCh, respectively. Cell length was normalized, fluorescence levels were plotted, the fluorescence of the cell before bleaching was scaled down and correspond to one-third of the real one. The time in minutes is indicated.

DISCUSSION

In a previous work, we proposed that the OmpA2 polar gradient forms before the protein is immobilized by its interaction with the cell wall or by its insertion in the OM (17). FRAP experiments showed that the full OmpA2 protein does not diffuse, and in consequence, the gradient must form before the protein is anchored. Gradients are normally the result of the continuous diffusion of a molecule from a source, but a gradient formed by an immobile protein could also be the result of uneven dilution or displacement; for this reason, it was important to determine if the static OmpA2 gradient was the result of a different cell process. Full-cell bleaching showed that the OmpA2 gradient formed at the old cell pole and that, in contrast with the gradient formed by the PBD, it was the result of a brief period of diffusion and not of cell growth or division. Since in C. crescentus mRNAs do not move from the position of the gene locus (42) and since it is possible that the Sec translocon does not diffuse when its active (43), our model assumes that the OmpA2 diffusion that results in a gradient occurs in the periplasm. Fast engagement of proteins with the Sec system that results in higher concentration of particular transmembrane proteins has been proposed as an important mechanism for the heterogeneous organization of the inner membrane in a mechanism named transertion (44). It has been recently proposed that this mechanism can influence the BAM independent insertion of an OMP in the OM by increasing its local concentration in the periplasm (45). In line with this idea, it has been proposed that a supercomplex forms between the Sec and BAM complexes when an OMP is being translocated, mediated by the simultaneous interaction of the SurA periplasmic chaperone with its substrate and the BAM complex (46, 47). For OmpA2, transertion followed by fast diffusion restriction results in a physiological relevant organization of the protein in the OM.

To determine if any of the two OmpA2 domains was enough for the formation of the gradient, we generated truncated versions of OmpA2. A fluorescent fusion of the β-barrel localized evenly, and in contrast to what has been previously reported in E. coli (20), the OmpA2 β-barrel slowly diffuses, indicating that this domain by itself is not enough to maintain the gradient. The absence of OMP diffusion in E. coli has been attributed to promiscuous protein interactions, but this idea has only been tested in in vitro experiments (21). The diffusion of the β-barrel could be explained by a particularly slippery surface of the protein that reduces its interactions with other proteins. Another possibility is that the properties of the OM are different in C. crescentus; in agreement with this idea, the C. crescentus OM lipid composition and the structure of the lipid A show relevant differences with that of E. coli (48, 49). In contrast with the β-barrel, the PBD does not diffuse, indicating that the interaction of this domain with the cell wall is very stable even without the N-terminal domain. The localization of this domain showed a band of reduced intensity around the division site that was not detected in FtsZ-depleted cells, indicating that its presence was related with active division. Before C. crescentus cells start constricting and shortly after the FtsZ ring forms, the cell wall growth changes from a lateral to a zonal growth pattern, in which the cell wall growth concentrates at the sides of the FtsZ ring (50). The peripheral cell wall growth could be diluting or pushing away the cell wall-bound OmpA2 PBD, creating the observed pattern. Additionally, the PBD could be being displaced by other proteins; an obvious candidate is Pal that binds to the same substrate and accumulates at the division site, but other division proteins may also be responsible. Another possibility is a change in the composition of the peptidoglycan; in E. coli it has been reported that peptidoglycan stripped of peptides by the activity of the amidases (denuded peptidoglycan) accumulates at the division site (51, 52). This would result in a lower concentration of the PBD binding substrate. Since according to our FRAP data the majority of the PBD is immobile, once the PBD is displaced, the region can only be occupied by new protein. But this can only occur after the division-related process that displaced the PBD has ended, and it would only be visible after the mCherry fluorophore has matured. The fact that this band does not form with the full protein fusion indicates that the presence of β-barrel has a role in keeping OmpA2 at its position in the division site. Despite its tight binding to the cell wall, the PBD does not form a gradient, suggesting that in the absence of the N-terminal domain the PBD has enough time to distribute evenly before binding. Assuming that the PBD fusion is still being translocated at the same position as the full protein, this indicates that after the full protein is exported to the periplasm, the diffusion of the protein is initially reduced by the interactions made by the β-barrel, at first with the periplasmic chaperones and the Bam complex and later by the reduced mobility of this domain in the OM, giving the PBD time to fold and bind to the cell wall. The presence of the β-barrel could also be relevant to limit the diffusion of the OmpA2 preprotein so that translocation occurs close to the gene locus. Another possible function of the β-barrel could be to help the PBD fold faster. In line with this idea, while the OmpA2 single amino acid variants in the PBD were only slightly unstable and could be rescued by the chaperones, the PBD variants carrying the same substitutions were not stable, indicating that the β-barrel has a role in the folding of PBD either directly or by the recruitment of periplasmic chaperons.

It was previously shown that the D271 and R286 conserved amino acids were essential for substrate binding of the A. baumannii OmpA and that binding of the substrate was necessary for normal protein folding (12, 40). Accordingly, the OmpA2 variants of the corresponding conserved amino acids (D336A and R351A) did not form a concentration gradient and were more sensitive to protein degradation. Unexpectedly only the R351 residue was indispensable for substrate binding since the absence of the D336 residue could be compensated by the action of the periplasmic chaperones, suggesting different roles for these two amino acids during folding and substrate binding. However, both amino acids seem to be required for full affinity since cells expressing the OmpA2D336A allele and overexpressing the chaperones still produced a small amount of OMVs. Surprisingly, the stability of the proteins carrying the single amino acid substitutions in the strains overexpressing the chaperones was similar to that in the FtsZ-depleted cells; this result indicates that cell filamentation causes periplasmic stress in the same way as it causes cytoplasmic stress (53). This filamentation-induced stress could also be causing the absence of diffusion of the OmpA2 β-barrel in the overfilamented cells by directly promoting the association of this domain with other proteins as part of the stress response or indirectly if the outer membrane properties are modified.

Full-cell bleaching showed that OmpA2 is being inserted in the OM near the old pole. In E. coli, the insertion of OMP occurs preferentially in the lateral cell body and not at the poles (21); however, polar insertion has been reported in the case of a family of autotransporters, including the E. coli AIDA-I protein (23). The best-studied case is that of the IscA protein of Shigella flexneri, which forms a polar gradient at the old cell pole (54). Polar localization of IcsA is directed by a signal present in the protein, and it depends on OmpA and PhoN (55–59). It would be interesting to know if OmpA in this bacterium also forms a polar gradient that could direct the insertion of IcsA. In contrast, in C. crescentus, the polar insertion of OmpA2 depends on the position of the gene in the cell and the consequent polar translocation of the protein to the periplasm that is then inserted in the OM. If the translocation of OMPs occurs close to where they are being synthesized, as the OmpA2 model suggests, one possible explanation for the OMP medial insertion pattern observed in E. coli is the position from which the proteins are being translated and translocated.

The fact that neither of the OmpA2 domains could generate a gradient regardless of either their low or no diffusion shows that the formation of this localization pattern is the result of the combination of the different properties of the domains and their interactions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids, bacterial strains, and growth conditions.

Strains and plasmids are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material, and their construction is explained in the text in the supplemental material. DH5α or TOP10 E. coli strains were used to maintain and purify plasmids. These strains were grown in LB medium with the appropriate antibiotic at 37°C. C. crescentus strains were grown at 30°C in peptone-yeast extract (PYE) rich medium or Tris-based M5GG minimal medium supplemented with 50 μM phosphate (60). Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations (μg/ml) for E. coli: gentamicin, 20; kanamycin, 50; spectinomycin, 50; nalidixic acid, 20; and chloramphenicol, 30. For C. crescentus, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations (μg/ml) for liquid and solid medium, respectively: gentamicin, 2 and 5; kanamycin, 5 and 20; spectinomycin, 15 and 100; and chloramphenicol 2 and 5.

Genetic and molecular biology techniques.

All DNA manipulation, analysis, and bacterial transformations were performed according to standard protocols. For a detailed description see the text in the supplemental material. Conjugations and transductions were carried out as previously described (60). Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out by a previously reported protocol (61) with some modifications.

SDS-PAGE, Western blot, and mobility shift assay.

For Western blots, samples were mixed with sample buffer (final concentrations of 50 mM Tris [pH 6.8], 1% SDS, 10% glycerol, 2% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 2 mM EDTA) and incubated for 15 min at 45, 60, 80, or 100°C for the mobility shift assays or at 100°C for regular Western blots. SDS-PAGE resolved proteins were transferred to a 0.45-μm nitrocellulose membrane, incubated for ∼4 h with a mouse red fluorescent protein (mRFP) polyclonal anti-RFP antibody raised against 6×His-tagged mRFP (1:20,000 vol/vol) (17). For detection, an alkaline phosphatase conjugated to an anti-mouse antibody (1:30,000 vol/vol; Sigma) was used together with the CDP-Star/Nitro-block substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All samples were collected from cell cultures at an optical density at 660 nm (OD660) of 0.3, and the protein amount was quantified by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). An equal amount of protein (3 μg) was loaded in each lane.

Cell fractionation.

To determine the subcellular location of both OmpA2 truncated versions, cell fractionation from exponential cultures (OD660, 0.3) was performed as previously described (62). For a detailed description see the text in the supplemental material.

FRAP and full-cell bleaching experiments.

Cells were grown in PYE rich medium overnight at 30°C in the presence of 0.3% (vol/vol) xylose if necessary. The next day, cultures were reinoculated in the same medium and grown up to an OD660 of ∼0.6. For depletion strains, cells were washed three times with PYE medium and diluted to an OD of ∼0.05. Antibiotic-induced filamentation was achieved by adding cephalexin at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml to a 1-ml culture at an OD of ∼0.05. After cells reached the intended cell length (for FtsZ depletion, 1 h or 4 h; for FtsI depletion, 5 and 16 h, for short and long filaments, respectively; and 3 h for cephalexin), translation was inhibited by adding chloramphenicol and spectinomycin at a final concentration of 80 μg/ml and 300 μg/ml (for FtsZ depletions in LDG6 strain) or 20 μg/ml and 75 μg/ml (for FtsI and cephalexin filaments), respectively. Then, cells were incubated for an additional 1 hour. These antibiotic concentrations were necessary to efficiently block OmpA2 synthesis, and the incubation period allowed the complete maturation of mCherry and OmpA2 in the periplasm. A 1-μl sample was placed on a 1.5% agarose pad made with M2 1× salt solution with the same antibiotic mix. Samples were covered with a coverslide and sealed with a mixture of petrolatum, paraffin, and mineral oil and maintained at 30°C by means of an objective heater (Bioptechs). Cells were visualized using a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted epifluorescence microscope equipped with a Micropoint (Andor) FRAP unit and a SCMOS pco.edge camera, controlled with MicroManager 2.0 Beta (63). Photobleaching was achieved by using a 590-nm green laser dye. The laser intensity was reduced with a 30/70 beam splitter and by a software-controlled attenuator. These settings allowed to bleach ∼60% of the OmpA2-mCherry fluorescence within an area of ∼1.0 μm2. Fluorescence images were acquired at 400 ms using an ND4 filter in order to reduce the mercury lamp intensity and fluorescence loss. The acquisition rate was every minute (for OmpA2 and its mutants) or every second (for periplasmic mCherry and FtsN).

For complete cell bleaching, synchronized wild-type cells growing on 1.5% agarose pads made with PYE medium at 30°C were bleached and visualized under the same conditions described above. Acquisition rate was every 10 minutes. The cells in the images were detected with MicrobeTracker, and fluorescence intensity profiles were obtained using the intprofileall tool. Plots were edited using MATLAB after normalization of the cell length from 0 to 1 for each time.

FRAP analysis.

Using ImageJ (64), we constructed 16-bit TIFF stacks from raw images, the background was subtracted, and the intensity of a 15- by 40-pixel selection was obtained from the bleached region, a neighboring nonbleached cell, and the background using the average pixel intensity tool. The intensity of the background was subtracted from both reference and FRAP signals, and the bleaching was corrected. The percentage of fluorescence recovery was calculated using Excel. Normalized FRAP curves were fitted using the MATLAB “cftool” application to the single-exponential equation I(t) = A(1 − e−bt), where I, t, A, and b correspond to fluorescence intensity, time, mobile fraction, and fluorescence recovery rate, respectively. Recovery half life (t1/2) was determined using the formula t1/2 = ln (0.5)/−b. Data were obtained from at least 10 cells from three independent time-lapse experiments. Apparent diffusion coefficients (D) were determined using the classical two-dimensional FRAP equation D = 0.224 (r2/t1/2) (65), where r is the radius of the bleach laser. Because r exceeds cell width, we approximated r from a circular selection covering the bleached area in each analyzed cell.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

L.D.G. was supported by a fellowship from CONACyT 333933. This study was supported by grant PAPIIT IN203119 and by the Programa de Producción de Biomoléculas.

We thank the Molecular Biology Unit of the IFC and Miguel Tapia who is responsible for the Microscopy Unit of the IIB.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00177-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Silhavy TJ, Kahne D, Walker S. 2010. The bacterial cell envelope. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2:a000414. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deng Y, Sun M, Shaevitz JW. 2011. Direct measurement of cell wall stress stiffening and turgor pressure in live bacterial cells. Phys Rev Lett 107:158101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.158101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braun V, Wolff H. 1970. The murein-lipoprotein linkage in the cell wall of Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem 14:387–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1970.tb00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun V, Sieglin U. 1970. The covalent murein-lipoprotein structure of the Escherichia coli cell wall. The attachment site of the lipoprotein on the murein. Eur J Biochem 13:336–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1970.tb00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cascales E, Bernadac A, Gavioli M, Lazzaroni JC, Lloubes R. 2002. Pal lipoprotein of Escherichia coli plays a major role in outer membrane integrity. J Bacteriol 184:754–759. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.3.754-759.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernadac A, Gavioli M, Lazzaroni JC, Raina S, Lloubes R. 1998. Escherichia coli tol-pal mutants form outer membrane vesicles. J Bacteriol 180:4872–4878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith SG, Mahon V, Lambert MA, Fagan RP. 2007. A molecular Swiss army knife: OmpA structure, function and expression. FEMS Microbiol Lett 273:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonntag I, Schwarz H, Hirota Y, Henning U. 1978. Cell envelope and shape of Escherichia coli: multiple mutants missing the outer membrane lipoprotein and other major outer membrane proteins. J Bacteriol 136:280–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henning U, Sonntag I, Hindennach I. 1978. Mutants (ompA) affecting a major outer membrane protein of Escherichia coli K12. Eur J Biochem 92:491–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bremer E, Cole ST, Hindennach I, Henning U, Beck E, Kurz C, Schaller H. 1982. Export of a protein into the outer membrane of Escherichia coli K12. Stable incorporation of the OmpA protein requires less than 193 amino-terminal amino-acid residues. Eur J Biochem 122:223–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb05870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pautsch A, Schulz GE. 1998. Structure of the outer membrane protein A transmembrane domain. Nat Struct Biol 5:1013–1017. doi: 10.1038/2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park JS, Lee WC, Yeo KJ, Ryu KS, Kumarasiri M, Hesek D, Lee M, Mobashery S, Song JH, Kim SI, Lee JC, Cheong C, Jeon YH, Kim HY. 2012. Mechanism of anchoring of OmpA protein to the cell wall peptidoglycan of the gram-negative bacterial outer membrane. FASEB J 26:219–228. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-188425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poindexter JS. 1964. Biological properties and classification of the Caulobacter group. Bacteriol Rev 28:231–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viollier PH, Thanbichler M, McGrath PT, West L, Meewan M, McAdams HH, Shapiro L. 2004. Rapid and sequential movement of individual chromosomal loci to specific subcellular locations during bacterial DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:9257–9262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402606101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thanbichler M, Wang SC, Shapiro L. 2005. The bacterial nucleoid: a highly organized and dynamic structure. J Cell Biochem 96:506–521. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiekebusch D, Thanbichler M. 2013. Spatiotemporal organization of microbial cells by protein concentration gradients. Trends Microbiol 22:P65–P73. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ginez LD, Osorio A, Poggio S. 2014. Localization of the outer membrane protein OmpA2 in Caulobacter crescentus depends on the position of the gene in the chromosome. J Bacteriol 196:2889–2900. doi: 10.1128/JB.01516-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleanthous C, Rassam P, Baumann CG. 2015. Protein-protein interactions and the spatiotemporal dynamics of bacterial outer membrane proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol 35:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lill Y, Jordan LD, Smallwood CR, Newton SM, Lill MA, Klebba PE, Ritchie K. 2016. Confined mobility of TonB and FepA in Escherichia coli membranes. PLoS One 11:e0160862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verhoeven GS, Dogterom M, den Blaauwen T. 2013. Absence of long-range diffusion of OmpA in E. coli is not caused by its peptidoglycan binding domain. BMC Microbiol 13:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rassam P, Copeland NA, Birkholz O, Toth C, Chavent M, Duncan AL, Cross SJ, Housden NG, Kaminska R, Seger U, Quinn DM, Garrod TJ, Sansom MS, Piehler J, Baumann CG, Kleanthous C. 2015. Supramolecular assemblies underpin turnover of outer membrane proteins in bacteria. Nature 523:333–336. doi: 10.1038/nature14461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunasinghe SD, Shiota T, Stubenrauch CJ, Schulze KE, Webb CT, Fulcher AJ, Dunstan RA, Hay ID, Naderer T, Whelan DR, Bell TDM, Elgass KD, Strugnell RA, Lithgow T. 2018. The WD40 protein BamB mediates coupling of BAM complexes into assembly precincts in the bacterial outer membrane. Cell Rep 23:2782–2794. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.04.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain S, van Ulsen P, Benz I, Schmidt MA, Fernandez R, Tommassen J, Goldberg MB. 2006. Polar localization of the autotransporter family of large bacterial virulence proteins. J Bacteriol 188:4841–4850. doi: 10.1128/JB.00326-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibbs KA, Isaac DD, Xu J, Hendrix RW, Silhavy TJ, Theriot JA. 2004. Complex spatial distribution and dynamics of an abundant Escherichia coli outer membrane protein, LamB. Mol Microbiol 53:1771–1783. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghosh AS, Young KD. 2005. Helical disposition of proteins and lipopolysaccharide in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 187:1913–1922. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.6.1913-1922.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gunasinghe SD, Webb CT, Elgass KD, Hay ID, Lithgow T. 2017. Super-resolution imaging of protein secretion systems and the cell surface of gram-negative bacteria. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7:220. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ricci DP, Silhavy TJ. 2019. Outer membrane protein insertion by the beta-barrel assembly machine. EcoSal Plus doi: 10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0035-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ursell TS, Trepagnier EH, Huang KC, Theriot JA. 2012. Analysis of surface protein expression reveals the growth pattern of the gram-negative outer membrane. PLoS Comput Biol 8:e1002680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smit J, Nikaido H. 1978. Outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria. XVIII. Electron microscopic studies on porin insertion sites and growth of cell surface of Salmonella Typhimurium. J Bacteriol 135:687–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beher MG, Schnaitman CA, Pugsley AP. 1980. Major heat-modifiable outer membrane protein in gram-negative bacteria: comparison with the ompA protein of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 143:906–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reithmeier RA, Bragg PD. 1977. Molecular characterization of a heat-modifiable protein from the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. Arch Biochem Biophys 178:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(77)90223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohnishi S, Kameyama K, Takagi T. 1998. Characterization of a heat modifiable protein, Escherichia coli outer membrane protein OmpA in binary surfactant system of sodium dodecyl sulfate and octylglucoside. Biochim Biophys Acta 1375:101–109. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohnishi S, Kameyama K. 2001. Escherichia coli OmpA retains a folded structure in the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate due to a high kinetic barrier to unfolding. Biochim Biophys Acta 1515:159–166. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(01)00410-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakamura K, Mizushima S. 1976. Effects of heating in dodecyl sulfate solution on the conformation and electrophoretic mobility of isolated major outer membrane proteins from Escherichia coli K-12. J Biochem 80:1411–1422. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a131414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heller KB. 1978. Apparent molecular weights of a heat-modifiable protein from the outer membrane of Escherichia coli in gels with different acrylamide concentrations. J Bacteriol 134:1181–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elowitz MB, Surette MG, Wolf PE, Stock JB, Leibler S. 1999. Protein mobility in the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 181:197–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ebersbach G, Briegel A, Jensen GJ, Jacobs-Wagner C. 2008. A self-associating protein critical for chromosome attachment, division, and polar organization in Caulobacter. Cell 134:956–968. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shigi Y, Matsumoto Y, Kaizu M, Fujishita Y, Kojo H. 1984. Mechanism of action of the new orally active cephalosporin FK027. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 37:790–796. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.37.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McBroom AJ, Kuehn MJ. 2007. Release of outer membrane vesicles by Gram-negative bacteria is a novel envelope stress response. Mol Microbiol 63:545–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05522.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mushtaq AU, Park JS, Bae SH, Kim HY, Yeo KJ, Hwang E, Lee KY, Jee JG, Cheong HK, Jeon YH. 2017. Ligand-mediated folding of the OmpA periplasmic domain from Acinetobacter baumannii. Biophys J 112:2089–2098. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rollauer SE, Sooreshjani MA, Noinaj N, Buchanan SK. 2015. Outer membrane protein biogenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 370:20150023. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Montero Llopis P, Jackson AF, Sliusarenko O, Surovtsev I, Heinritz J, Emonet T, Jacobs-Wagner C. 2010. Spatial organization of the flow of genetic information in bacteria. Nature 466:77–81. doi: 10.1038/nature09152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dajkovic A, Hinde E, MacKichan C, Carballido-Lopez R. 2016. Dynamic organization of SecA and SecY secretion complexes in the B. subtilis membrane. PLoS One 11:e0157899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsumoto K, Hara H, Fishov I, Mileykovskaya E, Norris V. 2015. The membrane: transertion as an organizing principle in membrane heterogeneity. Front Microbiol 6:572. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hay ID, Belousoff MJ, Dunstan RA, Bamert RS, Lithgow T. 2018. Structure and membrane topography of the vibrio-type secretin complex from the type 2 secretion system of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 200:e00521-17. doi: 10.1128/JB.00521-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Babu M, Bundalovic-Torma C, Calmettes C, Phanse S, Zhang Q, Jiang Y, Minic Z, Kim S, Mehla J, Gagarinova A, Rodionova I, Kumar A, Guo H, Kagan O, Pogoutse O, Aoki H, Deineko V, Caufield JH, Holtzapple E, Zhang Z, Vastermark A, Pandya Y, Lai C. C-l, El Bakkouri M, Hooda Y, Shah M, Burnside D, Hooshyar M, Vlasblom J, Rajagopala SV, Golshani A, Wuchty S, F Greenblatt J, Saier M, Uetz P, F Moraes T, Parkinson J, Emili A. 2018. Global landscape of cell envelope protein complexes in Escherichia coli. Nat Biotechnol 36:103–112. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y, Wang R, Jin F, Liu Y, Yu J, Fu X, Chang Z. 2016. A supercomplex spanning the inner and outer membranes mediates the biogenesis of beta-barrel outer membrane proteins in bacteria. J Biol Chem 291:16720–16729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.710715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smit J, Kaltashov IA, Kaltoshov IA, Cotter RJ, Vinogradov E, Perry MB, Haider H, Qureshi N. 2008. Structure of a novel lipid A obtained from the lipopolysaccharide of Caulobacter crescentus. Innate Immun 14:25–37. doi: 10.1177/1753425907087588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Siervo AJ, Homola AD. 1980. Analysis of Caulobacter crescentus lipids. J Bacteriol 143:1215–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aaron M, Charbon G, Lam H, Schwarz H, Vollmer W, Jacobs-Wagner C. 2007. The tubulin homologue FtsZ contributes to cell elongation by guiding cell wall precursor synthesis in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol Microbiol 64:938–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ursinus A, van den Ent F, Brechtel S, de Pedro M, Höltje J-V, Löwe J, Vollmer W. 2004. Murein (peptidoglycan) binding property of the essential cell division protein FtsN from Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 186:6728–6737. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.20.6728-6737.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yahashiri A, Jorgenson MA, Weiss DS. 2015. Bacterial SPOR domains are recruited to septal peptidoglycan by binding to glycan strands that lack stem peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:11347–11352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508536112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sanchez-Gorostiaga A, Palacios P, Martinez-Arteaga R, Sanchez M, Casanova M, Vicente M. 2016. Life without division: physiology of Escherichia coli FtsZ-deprived filaments. MBio 7:e01620-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01620-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steinhauer J, Agha R, Pham T, Varga AW, Goldberg MB. 1999. The unipolar Shigella surface protein IcsA is targeted directly to the bacterial old pole: IcsP cleavage of IcsA occurs over the entire bacterial surface. Mol Microbiol 32:367–377. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.May KL, Morona R. 2008. Mutagenesis of the Shigella flexneri autotransporter IcsA reveals novel functional regions involved in IcsA biogenesis and recruitment of host neural Wiscott-Aldrich syndrome protein. J Bacteriol 190:4666–4676. doi: 10.1128/JB.00093-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ambrosi C, Pompili M, Scribano D, Zagaglia C, Ripa S, Nicoletti M. 2012. Outer membrane protein A (OmpA): a new player in Shigella flexneri protrusion formation and inter-cellular spreading. PLoS One 7:e49625. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scribano D, Petrucca A, Pompili M, Ambrosi C, Bruni E, Zagaglia C, Prosseda G, Nencioni L, Casalino M, Polticelli F, Nicoletti M. 2014. Polar localization of PhoN2, a periplasmic virulence-associated factor of Shigella flexneri, is required for proper IcsA exposition at the old bacterial pole. PLoS One 9:e90230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Doyle MT, Grabowicz M, Morona R. 2015. A small conserved motif supports polarity augmentation of Shigella flexneri IcsA. Microbiology 161:2087–2097. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scribano D, Damico R, Ambrosi C, Superti F, Marazzato M, Conte MP, Longhi C, Palamara AT, Zagaglia C, Nicoletti M. 2016. The Shigella flexneri OmpA amino acid residues 188EVQ190 are essential for the interaction with the virulence factor PhoN2. Biochem Biophys Rep 8:168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ely B. 1991. Genetics of Caulobacter crescentus. Methods Enzymol 204:372–384. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04019-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kunkel TA. 1985. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 82:488–492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Osorio A, Camarena L, Cevallos MA, Poggio S. 2017. A new essential cell division protein in Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol 199:e00811-16. doi: 10.1128/JB.00811-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Edelstein AD, Tsuchida MA, Amodaj N, Pinkard H, Vale RD, Stuurman N. 2014. Advanced methods of microscope control using μManager software. J Biol Methods 1:e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. 2012. NIH Image to Image J: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Soumpasis DM. 1983. Theoretical analysis of fluorescence photobleaching recovery experiments. Biophys J 41:95–97. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(83)84410-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.