SUMMARY

Human T cells are central effectors of immunity and cancer immunotherapy. CRISPR-based functional studies in T cells could prioritize novel targets for drug development and improve the design of genetically reprogrammed cell-based therapies. However, large-scale CRISPR screens have been challenging in primary human cells. We developed a new method, sgRNA lentiviral infection with Cas9 protein electroporation (SLICE), to identify regulators of stimulation responses in primary human T cells. Genome-wide loss-of-function screens identified essential T cell receptor signaling components and genes that negatively tune proliferation following stimulation. Targeted ablation of individual candidate genes characterized hits and identified perturbations that enhanced cancer cell killing. SLICE coupled with single-cell RNA-Seq revealed signature stimulation-response gene programs altered by key genetic perturbations. SLICE genome-wide screening was also adaptable to identify mediators of immunosuppression, revealing genes controlling responses to adenosine signaling. The SLICE platform enables unbiased discovery and characterization of functional gene targets in primary cells.

Keywords: CRISPR, primary human T cells, pooled screens, immunotherapy, T cell activation, T cell proliferation, single-cell RNA-seq

INTRODUCTION

Cytotoxic T cells play a central role in immune-mediated control of cancer, infectious diseases, and autoimmunity. Immunotherapies such as checkpoint inhibitors and engineered cell-based therapies are revolutionizing cancer treatments, achieving durable responses in a subset of patients with otherwise refractory malignant disease (June et al., 2018; Wolchok et al., 2017). However, despite dramatic results in some patients, the majority of patients do not respond to available immunotherapies (Sharma et al., 2017). Much work remains to be done to extend immunotherapy to common cancers that continue to be refractory to current treatments.

Next-generation adoptive cell therapies are under development utilizing CRISPR-Cas9 genome engineering. Cas9 ribonucleoproteins can be delivered to primary human T cells to efficiently knockout checkpoint genes (Ren et al., 2017; Rupp et al., 2017; Schumann et al., 2015) or even re-write endogenous genome sequences (Roth et al., 2018). While deletion of the canonical checkpoint gene encoding PD-1 may enhance T cell responses to some cancers (Ren et al., 2017; Rupp et al., 2017), an expanded set of targets would offer additional therapeutic opportunities. Advances in immunotherapy depend on an improved understanding of the genetic programs that determine how T cells respond when they encounter their target antigens. Promising gene targets could enhance T cell proliferation and productive effector responses upon stimulation. In addition, immunosuppressive cells and soluble molecules such as cytokines and metabolites can accumulate within tumors and hamper productive anti-tumor T cell responses. Gene targets that influence a T cell’s ability to overcome such immunosuppressive tumor microenvironments could extend the reach of adoptive cell therapies to solid tumors.

Decades of work in animal models and cell lines have identified regulators of T cell suppression and activation, but systematic strategies to comprehensively analyze the function of genes that regulate human T cell responses are still lacking. Gene knock-down studies with curated RNA interference libraries have pointed to targets that enhance in vivo antigen-responsive T cell proliferation in mouse models (Zhou et al., 2014). More recently, CRISPR-Cas9 has ushered in a new era of functional genetics studies (Doench, 2018), where lentiviral particles encoding large libraries of single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) can generate pools of cells with diverse genomic modifications that can be tracked by sgRNA sequences in integrated provirus cassettes. This approach has been used in cell lines engineered to express stable Cas9 and in Cas9 transgenic mouse models (Parnas et al., 2015; Shang et al., 2018). Pooled CRISPR screens in human cancer cell lines are already revealing gene targets that modulate responses to T cell-based therapies (Manguso et al., 2017; Pan et al., 2018; Patel et al., 2017). However, CRISPR screening in primary human T cells – which can only be cultured ex vivo for limited time spans – has been hampered by low lentiviral transduction rates with Cas9-encoding vectors (Seki and Rutz, 2018). Critical biology of human immune cells, including key signaling pathways and effector functions, may not be recapitulated in immortalized cell lines. Genome-scale CRISPR screens in primary human T cells would enable comprehensive target discovery studies that could be rapidly translated into new immunotherapies with small molecules, biologics, and gene-engineered adoptive cell therapies.

Here we developed a screening platform that combines pooled lentiviral sgRNA delivery with Cas9 protein electroporation to enable loss-of-function pooled screening at genome-wide scale in primary human T cells. We applied this technology to identify gene modifications that promote T cell proliferation in response to stimulation. We further coupled pooled CRISPR delivery with single-cell transcriptome analysis of human T cells to characterize the cellular programs controlled by several of the genes found to regulate T cell responses in our genome-wide screens. A subset of the hits enhanced in vitro anti-cancer activity of human T cells, suggesting that this screening platform could be used to find promising preclinical candidates for next-generation cell therapies. Finally, we adapted the genome-wide screening context to model suppression by a well-described immunosuppressive metabolite, adenosine, to identify known as well as novel targets that enable escape from adenosine receptor-mediated immunosuppression. Taken together, these studies provide a rich resource of gene pathways that can be targeted to tune human T cell responses and a broadly applicable platform to probe primary human T cell biology at genome-scale.

RESULTS

A Hybrid Approach to Introduce Traceable Genetic Perturbations into Primary Human T Cells

We set out to establish a high-throughput CRISPR screening platform that works directly in ex vivo human hematopoietic cells. Current pooled CRISPR screening methods rely on establishing cell lines with stably integrated Cas9 expression cassettes. Our attempts to stably express Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 by lentivirus in primary human T cells resulted in extremely poor transduction efficiencies. This low efficiency was prohibitive of large-scale pooled screens in primary cells, which are not immortalized and can only be expanded in culture for a limited amount of time. We previously showed efficient gene editing of primary human T cells by electroporation of Cas9 protein pre-loaded in vitro with sgRNAs (Hultquist et al., 2016; Schumann et al., 2015). We conceived of a hybrid system to introduce traceable sgRNA cassettes by lentivirus followed by electroporation with Cas9 protein (Figure 1A). To test this strategy, we targeted the gene encoding a candidate cell surface protein, the alpha chain of the CD8 receptor (CD8A), as it is highly and uniformly expressed in human CD8+ T cells. We optimized multiple steps in lentiviral transduction, Cas9 electroporation, and T cell stimulation to ensure efficient delivery of each component while maintaining cell viability and proliferative potential (Figure S1A–S1D). Briefly, CD8+ T cells were isolated from peripheral blood of healthy donors, stimulated, and then transduced with lentivirus encoding an sgRNA cassette and an mCherry fluorescence protein reporter gene. Following transduction, T cells were transfected with recombinant Cas9 protein by electroporation. At day 4 post-electroporation, the transduced cells (mCherry+) were largely (>80%) CD8 negative (Figure 1B and Figure S1E), indicative of successful targeting by the Cas9-sgRNA combination. Loss of CD8 protein was specifically programmed by the targeting sgRNA, as cells transduced with a non-targeting control sgRNA retained high levels of CD8 expression. By targeting PTPRC (CD45) with the same delivery strategy, we confirmed successful knockout at a second target and demonstrated efficacy of the system in both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells (Figure S1F). We conclude that sgRNA lentiviral infection with Cas9 protein electroporation (SLICE) results in effective and specific disruption of target genes.

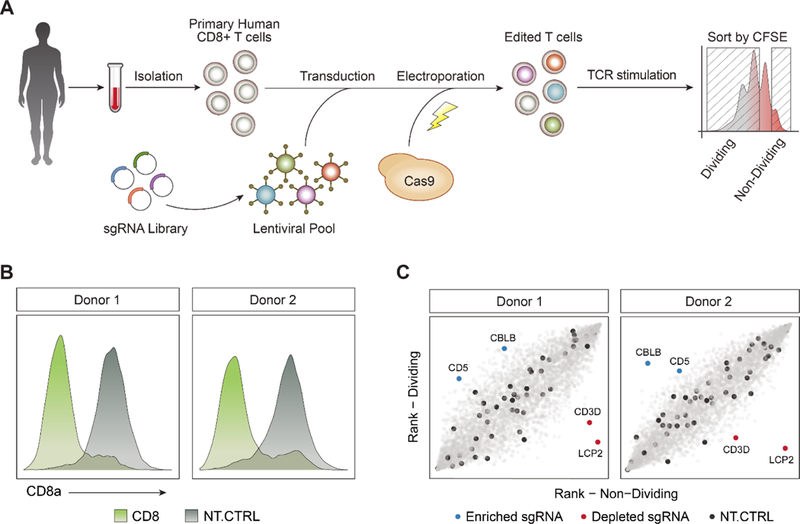

Figure 1. Framework for Unbiased Discovery of Regulators of Human T Cell Proliferation Using Pooled CRISPR Screens.

(A) Diagram of a hybrid system of sgRNA lentiviral infection and Cas9 electroporation (SLICE), enabling pooled CRISPR screens in primary human T cells.

(B) Editing of the CD8A gene with SLICE led to efficient protein knockdown in two independent donors.

(C) Targeted screen (4,918 guides) shows that sgRNAs targeting CBLB and CD5 were enriched in proliferating T cells (blue), while sgRNAs targeting LCP2 and CD3D were depleted (red). Non-targeting sgRNAs were evenly distributed across the cell populations (black).

We next tested whether SLICE could be expanded to allow large-scale loss-of-function screens in primary cells with pools of lentivirus-encoded sgRNAs. We performed a screen to identify gene targets that regulate T cell proliferation in response to T cell receptor (TCR) stimulation. For pilot studies we generated a custom library of sgRNA plasmids targeting all annotated cell surface proteins and several canonical members of the TCR signaling pathway (4,918 guides targeting 1211 genes total and 48 non-targeting guides, Table S1). CD8+ T cells isolated from two healthy human donors were transduced with lentivirus encoding this sgRNA library, electroporated with Cas9, and then maintained in culture (STAR Methods). At day 10 post-electroporation, cells were labeled with CFSE to track cell divisions and then TCR stimulated. After four days of stimulation, CFSE levels revealed that the cells had undergone multiple divisions. Cells were sorted by FACS into two populations: (1) non-proliferating cells (CFSE high) and (2) highly-proliferating cells (CFSE low) (Figure 1A, Figure S1G, and STAR Methods). We quantified sgRNA abundance from each population by deep sequencing of the amplified sgRNA cassettes. Consistent with well-maintained coverage of sgRNAs across experimental steps, we were able to detect all library guides in the infected CD8+ T cells, with the distribution of sgRNA abundance being relatively uniform for each donor and across biological replicates (Figure S1H). To identify sgRNAs that regulated T cell proliferation, we calculated the abundance-based rank difference between the highly dividing cells and non-dividing cells. sgRNAs with strong enrichment in dividing or non-dividing cells pointed to key biologic pathways. We found that sgRNAs targeting essential components of TCR signaling such as CD3D and LCP2, inhibited cell proliferation (de Saint Basile et al., 2004; Shen et al., 2009). We also found that proliferation could be enhanced in human T cells by targeting CD5 or CBLB, which have reported roles in the negative regulation of T cell stimulation responses (Voisinne et al., 2016). sgRNAs targeting these genes were in the top 1% by rank difference in both biological replicates (Figure 1C). Furthermore, multiple sgRNAs targeting these genes had concordant effects, increasing our confidence that the phenotype was not due to off-target effects (Figure S1I, Table S2). Importantly, sorting dividing and non-dividing primary cells based on CFSE provided stronger enrichment of sgRNA sequences than simple growth-based screens with otherwise identical experimental timelines (Figure S1J). Growth-based screens have been largely successful using immortalized cell lines that can be cultured for prolonged durations (Shalem et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014), however this did not translate to screens in primary human T cells. Taken together, these data demonstrate that SLICE pooled CRISPR screens can be used to discover positive and negative regulators of proliferation in primary human T cells.

A Genome-wide Pooled CRISPR Screen Uncovers Regulators of the TCR Response

To take full advantage of the high-throughput screening capacity of this platform, we scaled-up from the targeted pilot screen to genome-wide (GW) scale (Doench et al., 2016), transducing a library of 77,441 sgRNAs (19,114 genes) into T cells from two healthy donors. After confirming successful transduction of these primary human T cells (Figure S2A–B), the cells were restimulated and then FACS sorted into non-proliferating and highly-proliferating populations based on CFSE levels (Figure S2C and STAR Methods). MAGeCK software (Li et al., 2014) was used to systematically identify genes that were positively or negatively selected in the proliferating population of T cells (Table S3). Top positive and negative regulators from the pilot screen were confirmed in both biological replicates of the GW screen along with numerous other hits (Figure 2A, B). To hone the list of top candidates, we performed an independent secondary screen in cells from two additional human blood donors. The results were well correlated between the primary and secondary screens (Figure 2C). Integrated analysis of the two independent screens performed on a total of four human blood donors provided improved power for target discovery, particularly for negative regulators of T cell proliferation (Table S4 and Figure S2D). Because these CRISPR-based target perturbations require pre-stimulation, our results are generally expected to reflect modulators of the TCR-response in antigen-experienced cells. To confirm that the hits were in fact dependent on TCR stimulation, we performed GW screens with increasing levels of TCR stimulation. While similar gene targets appeared as positive and negative regulators across the conditions, the magnitude of the effects were blunted at higher levels of TCR stimulation, suggesting that stronger TCR stimulation can override the effects of these genetic perturbations (Figure 2D and Figure S2E). The observed dose-response confirmed that the majority of the screen hits are dependent on the TCR stimulus and serve to tune resulting proliferative responses. Taken together these screens identified dozens of genetic perturbations that positively and negatively modulate T cell proliferation.

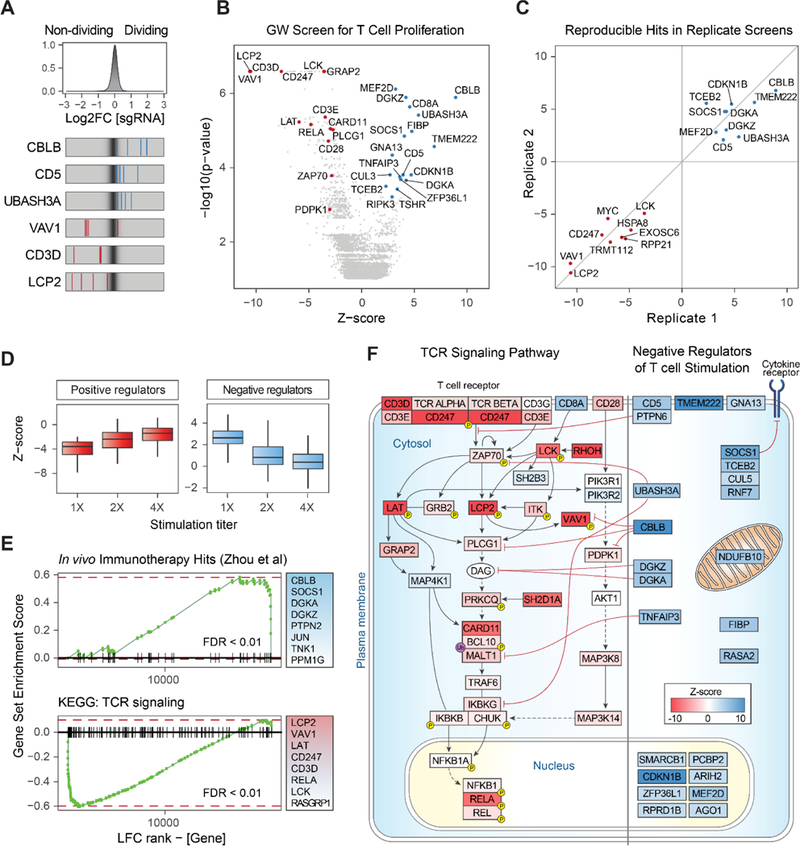

Figure 2. Genome-wide Screen in Primary Human T Cells Identifies Key Mediators of TCR Signaling Dependent T Cell Proliferation.

(A) Top panel: distribution of log2 fold-change (LFC) values of dividing over non-dividing cells for >75,000 guides in the genome-wide (GW) library. Bottom panel: LFC for all four sgRNAs targeting three genes enriched in dividing cells (blue lines) and three depleted genes (red lines), overlaid on grey gradient depicting the overall distribution. Values are averaged over two donors.

(B) Volcano plot for hits from the primary GW screen. X-axis shows Z-score (ZS) for gene-level LFC (median of LFC for all sgRNAs per gene, scaled). Y-axis shows the p-value as calculated by MAGeCK. Highlighted in red are negative hits (depleted in dividing cells, FDR < 0.2 and |ZS| > 2), which are annotated for the TCR signaling pathway by Gene Ontology (GO). Blue dots show all positive hits (Rank < 20 and |ZS| > 2). All values are calculated for two donors as biological replicates.

(C) Gene hits from the secondary GW screen in cells from two independent blood donors are positively correlated with the hits from the primary screen. Shown are Z-scores for overlapping hits for the top 25 ranking targets from the independent screens, in both positive and negative directions.

(D) Boxplots for Z-scores (scaled LFC) of the top 100 hits in each direction, for three GW screens with increasing TCR stimulation levels (1X = data in (B)). For both panels, LFC values trended towards 0, indicating selection pressure was reduced as the TCR signal increased. Horizontal line is the median, vertical line is the data range.

(E) Gene-set enrichment analysis shows significantly skewed LFC ranking of screen hits in two curated gene lists: (top panel) previously discovered hits by an shRNA screen in a mouse model of melanoma (Zhou et al., 2014) and (bottom panel) TCR signaling pathway by KEGG. The top eight gene members on the leading edge of each set enrichment are shown in the text-box on the right. Vertical lines on the x-axis are members of the gene set, ordered by their LFC rank in the GW screen. FDR = False discovery rate, permutation test.

(F) Modulators of TCR signaling and T cell activation detected in the GW screens. Depicted on the left are positive regulators of the TCR pathway found in our GW screens (FDR < 0.25). The curated TCR pathway is based on NetPath_11 (Kandasamy et al., 2010) and literature review. Depicted on the right are negative regulator genes (both known and unknown) found in our GW screens (FDR < 0.25), and represent candidate targets to boost T cell proliferation. Cellular localization and interaction edges are based on literature review. Gene nodes are shaded by their Z-score in the GW screen (red for positive and blue for negative Z-score values).

Genes identified in the integrated screen analysis were enriched with annotated pathways associated with TCR stimulation. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed significant overrepresentation of gene targets depleted from proliferating cells in the TCR signaling pathway (FDR < 0.01, Figure 2E and Figure S2F). Many of the negative regulators in our screen were enriched in the list of hits from a published shRNA screen (Zhou et al., 2014) that was designed to discover gene targets that boost T cell proliferation in tumor tissue in vivo (FDR < 0.01). This result is striking, as the studies were done in a different organism with a different gene perturbation platform, yet there was significant enrichment for high ranking positive hits in our screen with the hit list discovered in this in vivo animal model. These global analyses confirmed that our functional screens could identify critical gene targets, now achievable at genome-wide scale directly in primary human cells.

Targets depleted from proliferating cells in this GW screen encode key protein complexes critical for TCR signaling (Figure 2F). For example, gene targets that impaired TCR dependent proliferation included those encoding delta and zeta chains of the TCR complex itself (negative rank 18 and 6, respectively), and LCK (negative rank 20) which directly phosphorylates and activates the TCR ITAMs and the central signaling mediator ZAP70 (negative rank 299) (Dave et al., 1998; Tsuchihashi et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2010). LCK and ZAP70 are translocated to the immunological synapse by RhoH (negative rank 2) (Chae et al., 2010). The ZAP70 target, LCP2 (negative rank 4), is an adaptor protein required for TCR-induced activation and mediates integration of TCR and CD28 co-stimulation signaling by activating VAV1 (negative rank 8), which is required for TCR-induced calcium flux and signal transduction (Dennehy et al., 2007; Tybulewicz, 2005). LAT (negative rank 38) is another ZAP70 target, which upon phosphorylation recruits multiple key adaptor proteins for signaling downstream of TCR engagement (Bartelt and Houtman, 2013).

Genes that negatively regulate T cell proliferation have therapeutic potential to boost T cell function. Many of the negative regulators are less well-annotated in the canonical TCR signaling pathway, although functions have been assigned to some. Diacylglycerol (DAG) kinases, DGKA (rank 17) and DGKZ (rank 1), which are negative regulators of DAG-mediated signals, were both found to restrain human T cell proliferation following stimulation (Chen et al., 2016). The E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase, CBLB (rank 4) and its interacting partner, CD5 (rank 12), work together to inhibit TCR activation via ubiquitination leading to degradation of the TCR (Voisinne et al., 2016). TCEB2 (rank 5) complexes with RNF7 (rank 34), CUL5 (rank 162), and SOCS1 (rank 3), a key suppressor of JAK/STAT signaling in activated T cells (Kamura et al., 1998; Liau et al., 2018). UBASH3A (rank 10), TNFAIP3, and its partner TNIP1 (rank 13 and 24, respectively) inhibit TCR-induced NFkB signaling, a critical survival and growth signal for activated CD8+ T cells (Düwel et al., 2009; Ge et al., 2017). In addition to these key complexes, genes encoding other less well-characterized cell surface receptors, cytosolic signaling components, and nuclear factors were found to inhibit proliferation (Figure 2F), revealing a promising resource set of candidate targets to boost the effects of T cell stimulation.

Arrayed Delivery of Cas9 RNPs Reveals that Hits Alter Stimulation Responses

We next confirmed the ability of high scoring genes to boost T cell activation and proliferation with arrayed electroporation of individual Cas9 ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) (Hultquist et al., 2016). We focused primarily on a set of highly-ranked negative regulators of proliferation due to their therapeutic potential to enhance T cell function when targeted. We first tested the effects of these arrayed gene knockouts on T cell proliferation following TCR stimulation. Briefly, CD8+ T cells from four human blood donors were stimulated, electroporated with RNPs, rested for 10 days, labelled with CFSE, and then re-stimulated (Figure 3A and STAR Methods). High-throughput flow cytometry determined proliferation responses in edited and control cells based on CFSE dilutions. This validated the ability of many of the tested gene targets to increase T cell proliferation post stimulation, consistent with their robust effects in the pooled screens (Figure S3A). For example, CBLB and CD5 knockout cells showed a marked increase in number of divisions post stimulation compared to controls, persistent across different guide RNAs and blood donors (Figure 3B). To systematically quantify cell proliferation across samples, we fitted the CFSE distributions using a mathematical model (Munson, 2010) (Figure S3B). This analysis revealed that perturbation of multiple negative regulators of T cell stimulation increased the proliferation index score compared to controls (7 out of 10 gene perturbations of negative regulators shown here). UBASH3A, CBLB, CD5, and RASA2 knockout T cells all showed greater than 2-fold increase in the proliferation index compared to non-targeting control cells (Figure 3C). Notably, targeting these genes did not increase proliferation in the unstimulated cells, indicating that they are not general regulators of proliferation but instead appear to modulate proliferation induced by TCR signaling. In contrast, guides against gene targets that were depleted in the proliferating cells in the pooled screens (CD3D and LCP2), showed a reduction in the proliferation index compared to the non-targeting controls. This arrayed RNP gene targeting system demonstrated that the majority of top genes identified by our screens robustly modulate stimulation-dependent proliferation in human CD8+ T cells.

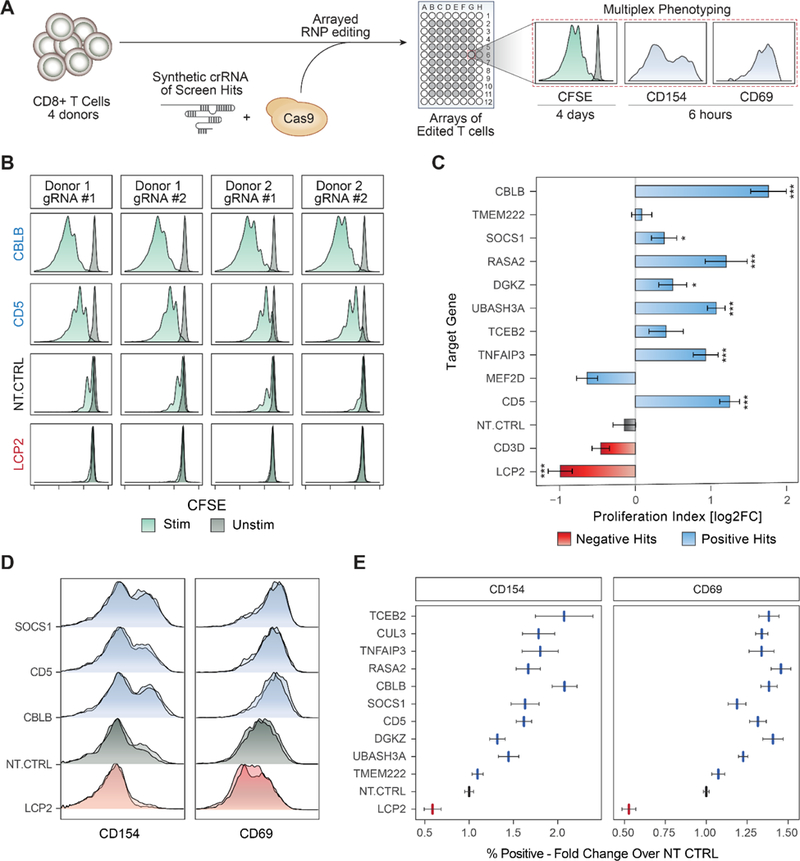

Figure 3. Validation of Gene Targets That Regulate T Cell Stimulation Using RNP Arrays.

(A) Overview of arrayed Cas9 RNP electroporation phenotyping strategy.

(B) Proliferation assay with CFSE-stained CD8+ T cells. Each panel shows CFSE signal from TCR-stimulated (green) or unstimulated (dark grey) human CD8+ T cells. Shown are data for two guides targeting negative regulators, CBLB and CD5, compared to non-targeting control (NT-CTRL) guides and guides targeting a critical TCR signaling gene, LCP2.

(C) Summary of data in (B) across sgRNAs. Gene targets (y-axis) are ordered by their rank in the GW pooled screens. X-axis is the calculated proliferation index (STAR methods), relative to NT-CTRL in each donor (log2 transformed). Bars show mean of two independent experiments, with two donors in each experiment. Error bars are SEM. *** denotes p < 0.001, * denotes p < 0.05, Standard t-test.

(D) Early activation markers, as measured by flow cytometry 6 hours post stimulation. Shown are representative distributions of two guides per targeted gene (y-axis) for CD154 (left) and CD69 (right).

(E) Summary of data in (D) for all gene targets tested (y-axis). X-axis is the fold-change increase in the marker-positive (CD69 or CD154) population over NT-CTRL. Vertical lines are mean values, error bars are SEM, two guides per gene, for four donors.

See also Figure S3.

We next examined whether these hits modulate canonical responses to TCR stimulation in addition to cell proliferation. The phenotype of cells edited in an arrayed format could be assessed with multiple markers at different time points. We analyzed two different cell surface markers of early CD8+ T cell activation, CD69 and CD154 (López-Cabrera et al., 1993; Shipkova and Wieland, 2012). At day 10 post-electroporation, cells were assessed 6 hours after re-stimulation. We found that T cells engineered to lack negative regulators of proliferation, such as SOCS1, CBLB, CD5, and others, also showed increased surface expression levels of both CD69 and CD154 compared to non-targeting control cells (Figure 3D and Figure S3C–D). Conversely, targeting a positive regulator of TCR signaling, LCP2, reduced expression of CD69 and CD154 in stimulated cells. Overall, the percent of cells expressing these activation markers in each condition was higher for positive hits compared to non-targeting control guides, consistent across two sgRNAs per gene, for four donors (Figure 3E). In summary, arrayed editing and phenotyping characterized the effects of genetic perturbations and revealed targets that boost stimulation-dependent proliferation and activation programs.

SLICE Paired with Single Cell RNA-Seq for Molecular Phenotyping of Modified Primary Human Cells

Next, we more deeply characterized the stimulation-dependent transcriptional programs altered by ablation of key target genes in human T cells. The recent combination of pooled CRISPR screens with single-cell RNA-Seq has enabled high-content analysis of transcriptional changes resulting from genetic perturbations in immortalized cell lines (Aarts et al., 2017, Adamson et al., 2016; Datlinger et al., 2017; Dixit et al., 2016) and cells from transgenic mice (Jaitin et al., 2016). Here, we coupled SLICE with a droplet-based single-cell transcriptome readout for highdimensional phenotyping of pooled perturbations in primary human T cells. We chose the CROP-Seq platform, as it offers a barcode-free pooled CRISPR screening method with single-cell RNA-Seq using the readily available 10X Genomics platform (Datlinger et al., 2017). We generated a custom library targeting selected hits from our GW screens (2 sgRNAs per gene), known checkpoint genes (PDCD1, TNFRSF9, C10orf54, HAVCR2, LAG3, BTLA), and 8 non-targeting controls, for a total of 48 sgRNAs (Table S5). Human T cells from two donors were transduced with this library, electroporated with Cas9 protein, and enriched with Puromycin selection (STAR Methods) (Figure S4A). Cells were subjected to single-cell transcriptome analysis either with or without re-stimulation to characterize alterations to cell state and stimulation response resulting from each genetic modification.

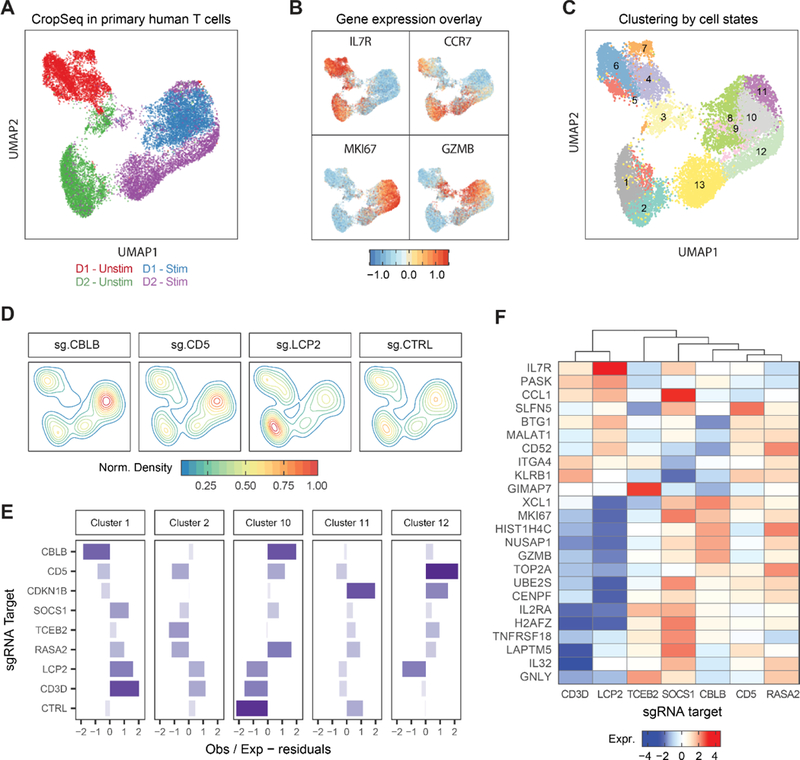

First, we analyzed the transcriptional states of more than 15,000 resting and stimulated single cells where we could identify an sgRNA barcode. Synthetic bulk gene expression profiles showed that stimulated cells up-regulated many cell cycle genes, indicating response to TCR stimulus (Figure S4B). We next visualized the distribution of these single cell transcriptomes in reduced dimensions using Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) (McInnes and Healy, 2018) (Figure 4A). While the unstimulated T cells had donor-dependent basal gene expression patterns, stimulated cells from the two donors tended to have a shared transcriptional signature and clustered together. For example, stimulated cells generally induced expression of cell cycle genes (e.g.: MKI67) and cytolytic granzymes (e.g.: GZMB) (Figure 4B). In contrast, unstimulated cells largely expressed markers of a resting state, such as IL7R and CCR7. TCR stimulation thus had a strong effect in inducing an activated cell state across biological replicates, although more cells appeared to have been stimulated strongly in Donor 1 than in Donor 2. To systematically impute cell states, we clustered single cells based on their shared nearest neighbors by gene expression (Figure 4C). Stimulated cells were enriched in clusters 9–12, which were characterized by preferential expression of mitotic cell cycle and T cell activation cellular programs (Figure S4C). This analysis of single cell transcriptomes revealed a characteristic landscape of cell states in human T cells before and after re-stimulation.

Figure 4. Pairing SLICE with Single Cell RNA-Seq for High Dimensional Molecular Phenotyping of Gene Knockouts in Primary Cells.

(A) UMAP plot of all single cells with identified sgRNAs across resting and re-stimulated T cells from two human donors.

(B) UMAP with scaled gene expression for four genes showing cluster associations with activation state (IL7R, CCR7), cell cycle (MKI67), and effector function (GZMB).

(C) Unsupervised clustering of single cells based on gene expression, 13 clusters identified as labeled.

(D) Clustering of cells expressing sgRNAs for CBLB, CD5, LCP and NT-CTRL on the UMAP representation.

(E) Y-axis shows over- or under-representation of cells expressing sgRNAs (y-axis) across clusters (panels), as determined by a chi-square test.

(F) Heatmap showing average gene expression (y-axis) across stimulated cells with different sgRNA targets (x-axis). Data represents one of two donors.

See also Figure S4.

We next assessed the effect of CRISPR-mediated genetic perturbations on cell states. Efficient editing for the majority of gene targets was validated by reduced expression of sgRNA target transcripts compared to levels in cells with non-targeting control sgRNAs (Figure S4D). We tested whether these gene perturbations caused altered genetic programs. Cells with non-targeting control sgRNAs were relatively evenly distributed among clusters. In contrast, cells with CBLB and CD5 sgRNAs were enriched in clusters associated with proliferation and activation, and those with LCP2 sgRNAs were found mostly in clusters characterized by resting profiles (Figure 4D).

We then quantified which sgRNA targets pushed cells towards distinct cell-state clusters based on their transcriptional profiles (Figure 4E). Targeting multiple negative regulators identified in the GW screens such as CD5, RASA2, SOCS1, and CBLB promoted the cluster 10–12 programs. These programs tended to be characterized by the induction of markers of activation states (e.g. IL2RA, TNFRSF18/GITR), cell cycle genes (e.g. MKI67, UBE2S, CENPF and TOP2A), and effector molecules (e.g GZMB) (Figure 4F and Figure S4E). In contrast, sgRNAs targeting CD3D or LCP2 inhibited the cluster 10 activation program and promoted the cluster 1–2 programs, characterized by expression of IL7R and CCR7. SLICE paired with single cell RNA-Seq revealed how target gene manipulation shapes stimulation-dependent cell states.

Targeting different negative regulators of proliferation led to distinct transcriptional consequences. Knockout of CBLB tended to induce a cell state signature similar to targeting known checkpoint genes BTLA or LAG3, as evidenced by similarity in cluster representation (Figure S4F). A different shared activation program was observed as a result of targeting CD5, TCEB2, RASA2 or CDKN1B. The integration of SLICE pooled CRISPR screens and single cell RNA-Seq provides a powerful approach to both discover and characterize critical gene pathways in primary human cells. These data also demonstrate that targeting negative regulators of proliferation can induce specialized stimulation-dependent effector gene programs that could enhance the potency of T cells.

Screen Hits Boost Cancer Cell Killing in vitro by Engineered Human T Cells

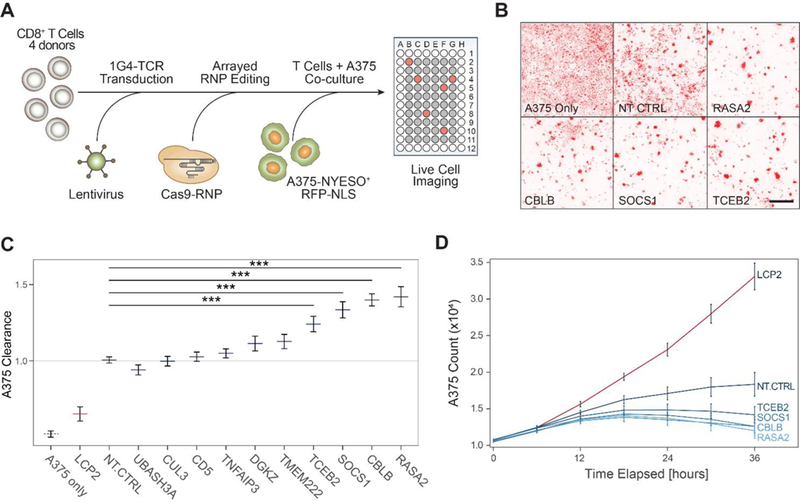

Cells engineered to have an enhanced proliferation response and to boost effector gene programs in response to TCR stimulation could hold promise for cancer immunotherapies. We tested the effects of target gene knockout in an antigen-specific in vitro cancer cell killing system (Figure 5A). Specifically, we used an RFP-expressing A375 melanoma cell line, which expresses the tumor antigen NY-ESO, as a target cell (Wargo et al., 2009). Antigen specific T cells were generated by transduction with the NY-ESO1-reactive 1G4 TCR (Robbins et al., 2008) (Figure S5A). These transduced T cells were able to induce caspase-mediated cell death in the target A375 cells, which was exhibited by a rise in the level of caspase and a decline in the level of RFP-tagged A375 nuclei over time (Figure S5B). Here, NY-ESO TCR+ T cells were generated from four donors using lentiviral transduction and then edited with RNPs in an array of 24 guides targeting 11 genes, including non-targeting controls. These edited antigen-specific T cells were then co-cultured with the A375 cells and killing was assessed by quantifying RFP-labeled A375 cells by live time-lapse microscopy over a span of 36 hours.

Figure 5. Genome-wide Screen Hits Boost in vitro Cancer Cell Killing by Engineered Antigen-specific Human T Cells.

(A) Diagram of a high throughput experimental strategy to test for gene targets that boost cancer cell killing in vitro by CD8+ T cells.

(B) Representative images taken at 36 hours post co-culture of human CD8+ T cells and A375-RFP+ tumor cells. Cancer cell density is shown in the red fluorescence channel, for representative wells, as annotated at the bottom left of each panel. Scale bar is 500μm.

(C) Clearance of RFP-labeled A375 cells by antigen-specific CD8 T cells after 36 hours. Clearance is defined as count of A375 cells in each well normalized to counts of A375 cells in wells with NT-CTRL T cells. Horizontal lines are the mean, error bars are the SEM, for two guides per gene target, across four donors and two technical replicates. *** denotes p < 0.001, Wilcoxon Rank Sum test.

(D) Time traces for A375 cell counts as measured by IncuCyte software for selected hits. Lines are mean for four donors, two guides per target gene. Error bars are SEM.

See also Figure S5.

We compared the kinetics of cancer cell killing between gene-edited and control NY-ESO TCR+ T cells. NY-ESO specific T cells started to cluster around RFP+ cancer cells at 12 hours, with more efficient cancer cell clearance at 36 hours for certain sgRNA targets compared to non-targeting controls (Figure 5B). As expected, knockout of LCP2 – dentified in our screens as essential for a strong TCR stimulation response – robustly disabled T cell killing of A375 cells. In contrast, CRISPR-ablation of negative regulators TCEB2, SOCS1, CBLB and RASA2 each significantly increased tumor cell clearance compared to control T cells electroporated with a non-targeting guide RNA (Figure 5C). Targeted deletion of these four genes led to improved kinetics of cancer cell clearance in our assay compared to the non-targeting control conditions (Figure 5D and Figure S5C–D). Among these, CBLB has been best studied as an intracellular immune checkpoint that can be targeted in T cells to improve tumor control in mouse models (Chiang et al., 2007; Hinterleitner et al., 2012). Targeting SOCS1, a negative regulator of JAK/STAT signaling in T cells, showed enhanced T cell clearance comparable to CBLB (Liau et al., 2018). Ablation of TCEB2, a binding partner of SOCS1, also improved tumor clearance, suggesting that the SOCS1/TCEB2 complex restrains T cell responses and is a potential target for immunotherapy (Ilangumaran et al., 2017; Kamizono et al., 2001; Liau et al., 2018). RASA2, a GTPase-activating protein that stimulates the GTPase activity of wild-type RAS (Arafeh et al., 2015), has not been studied in the context of primary T cells and the immune system, but our findings suggest it may be a modulator of T cell proliferation, activation, and anti-tumor immunity. In summary, several gene targets identified in the genome-wide screen for proliferative response to stimulation also potentiated in vitro tumor killing activity.

SLICE Screen for Resistance to Immunosuppressive Adenosine Signaling

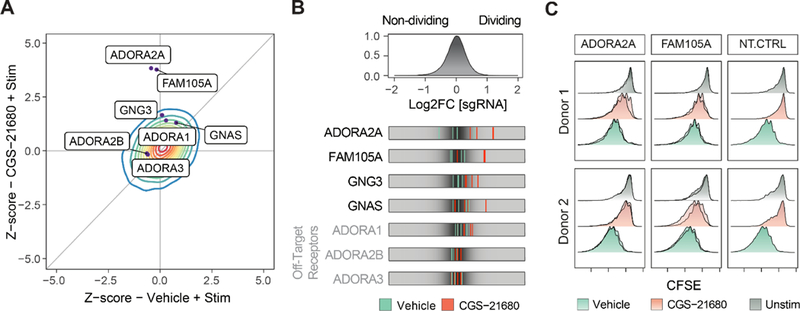

We next sought to demonstrate that SLICE is adaptable and can be used in a range of screening conditions to discover context-dependent functional effects of gene perturbations. Adoptive cell therapies that are effective for the treatment of solid tumors will require cells that can respond robustly to tumor antigens even in immunosuppressive tumor microenvironments. With genome editing, T cells could be rendered resistant to particular immunosuppressive cues, and it will be important to identify the relevant T cell pathways for modification. We reasoned that our SLICE screening platform also could be used to identify gene deletions that allow T cells to escape various forms of suppression. We focused on adenosine, a key immunosuppressive factor in the tumor microenvironment (Allard et al., 2017; Beavis et al., 2017). We performed a genome-wide proliferation screen by stimulating T cells in the presence of an adenosine receptor 2 (A2A) agonist (CGS-21680) at a suppressive dose of 20μM (Figure S6A) versus a vehicle control for four days (Jacobson and Gao, 2006). We looked for sgRNAs that were enriched in the proliferating cell population (CFSE low) in the A2A agonist treatment condition compared to the vehicle condition (Figure S6B, Table S6).

While many gene modifications promoted TCR proliferative responses to stimulation in the presence or absence of the adenosine receptor agonist, we identified several sgRNAs that were only enriched in the dividing cells in the presence of CGS-21680 (Figure 6A). These gene targets appear to play a selective role in adenosine receptor-mediated T cell suppression. Importantly, ADORA2A – encoding the receptor specifically targeted by CGS-21680 – showed a high rank difference between the two treatment conditions (rank 19 in CGS-21680 vs rank 7399 in vehicle control), indicating that its knockout provided a specific escape from CGS-21680 (Figure 6A and Figure S6C). In contrast, ADORA2B, which is not targeted by CGS-21680, did not show a preferential proliferative advantage in the presence of this selective A2A agonist (Figure 6A). These findings encouraged us to investigate other gene targets that show a similar pattern to ADORA2A in terms of selective resistance to CGS-21680. We noted that several guanine nucleotide binding proteins with potential roles in adenosine-responsive signaling had higher positive rank scores in the adenosine agonist GW screen, including GCGR (rank 35 vs. 1149), GNG3 (rank 199 vs. 12976), and GNAS (rank 836 vs. 2803). Strikingly, we found that multiple guides targeting a previously uncharacterized gene, FAM105A (rank 15 in CGS-21680 vs. rank 13390 in vehicle control), were specifically enriched nearly to the same extent as ADORA2A (Figure 6B). Although little is known about FAM105A function, GWAS of allergic diseases implicates a credible missense risk variant in this gene (Ferreira et al., 2017). A neighboring paralogue gene, Otulin (FAM105B), encodes a deubiquitinase with an essential role in immune regulation (Damgaard et al., 2016; Fiil and Gyrd-Hansen, 2016) (Figure S6D). These results suggest an important role for FAM105A in mediating adenosine immunosuppressive signals in T cells.

Figure 6. Adapting SLICE to Reveal Resistance to Immunosuppressive Signals in Primary Human T Cells.

(A) Z scores for the genome-wide screen for resistance to adenosine A2A selective agonist CGS-21680 (y-axis) compared to vehicle (x-axis). Contour represents the density (red for higher, blue for lower density) of all genes across the screen. Genes with selective effects on adenosine-mediated immunosuppression deviated upwards from the diagonal identity line. Dots show selected individual gene targets.

(B) Top panel: distribution of log2 fold change for all sgRNAs in the GW library for T cells treated with CGS-21680 (20μM). Bottom panel: LFC for selected sgRNAs in the vehicle (stimulation only) condition (green) compared to the CGS-21680 treated condition (red).

(C) Validation of gene targets from the adenosine resistance screen using T cells edited with individual RNPs. Knockout of both ADORA2A and FAM105A enables cells to proliferate more robustly in the presence of the adenosine agonist (CGS-21680), compared to the NT-CTRL RNP. Each panel shows results from two independent sgRNAs for two donors.

To validate our findings, we used our arrayed RNP platform to edit ADORA2A and FAM105A with a CFSE proliferation readout across two donors. We found that targeting each of these genes with two different sgRNAs each led to resistance to suppression by CGS-21680, as predicted by our screen (Figure 6C). Importantly, these edits did not lead to increased T cell proliferation in the absence of TCR stimulation, suggesting that they selectively overcome CGS-21680 suppression of TCR stimulation. Lastly, we showed that ADORA2A and FAM105A targeted T cells were resistant to suppression by CGS-21680 in the in vitro cancer cell killing assay (Figure S6E). Thus, we identified both extracellular and intracellular targets that could be modified to generate T cells resistant to adenosine suppression. Overall, these findings demonstrate that SLICE is able to identify both known and novel components of a pathway required for primary cell-response to a specific extracellular cue. This exemplifies the potential for this platform to be used to discover gene targets that can enhance specialized T cell functions.

DISCUSSION

SLICE provides a new platform for genome-wide CRISPR loss-of-function screens in primary human T cells, a cell type that has been central to a revolution in cancer immunotherapies. SLICE screens can be performed routinely at large-scale in primary cells from multiple human donors, ensuring biologically reproducible discoveries. Here, we enriched for genetic perturbations that enhanced stimulation-responsive T cell proliferation. We elected to use proliferation in response to TCR stimulation as our screening output, as it is a broad phenotype governed by complex genetics. It is possible that certain gene targets could be promoting the survival of a preexisting sub-population of T cells within the bulk CD8+ T cell population with a higher baseline proliferative capacity, rather than driving the proliferative state. However, the reproducible trends of top targets across multiple donors and screens, as well as in the RNP validation experiments, suggest that consistent hits are most likely not determined by heterogeneity of the starting populations. Arrayed editing with Cas9 RNPs allowed us to further characterize the effects of individual perturbations with multiplexed proteomics measured by flow cytometry. Finally, coupling SLICE with single-cell transcriptomics enabled a more global assessment of the functional consequences of perturbing hits from the genome wide screen. Integration of these CRISPR-based functional genetic studies rapidly pinpointed genes in human T cells that can be targeted to enhance stimulation-dependent proliferation, activation responses, effector programs, and in vitro cancer cell killing.

The potential power of human primary T cell loss-of-function screens was recently demonstrated in a patient who received CAR T cell therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) (Fraietta et al., 2018). Non-targeted integration of lentiviral provirus encoding a CAR construct can randomly disrupt endogenous genes. T cells with a lentiviral integration disrupting TET2 showed strong preferential expansion at the peak of a patient’s response and likely contributed to this complete response to CAR T cell therapy. This patient happened to have a pre-existing hypomorphic mutation in the second allele of TET2, suggesting that in this case, TET2 knockout was key to the T cells proliferative advantage and tumor control. SLICE now provides an opportunity to search more systematically for genetic perturbations that enhance cell expansion and effector function for adoptive T cell therapies.

We found that ablation of at least four targets (SOCS1, TCEB2, RASA2, and CBLB) in human T cells enhanced both proliferation and in vitro anti-cancer function. Of these, CBLB has been studied in mouse models as an intracellular checkpoint that can be targeted to enhance tumor control by CD8+ T cells. Our data suggest that RASA2 and the SOCS1/TCEB2 complex members may also be targets for modulation in immunotherapies. Ultimately, any candidate target from in vitro screens will have to be validated with in vivo models of function and tumor clearance. While we have focused on proliferation, looking forward, SLICE pooled screens could be adapted to select for perturbations that confer even more complex phenotypes on human T cells, including in vivo functions relevant for T cell therapies. Screens for phenotypes other than proliferation may reveal more useful targets for immunotherapies, and SLICE should provide a flexible platform for such screens. Integrating transcriptional or chromatin profiling from orthogonal in vivo studies with functional SLICE-based perturbations may also help to prioritize candidates for further investigation (Pauken et al., 2016, Philip et al., 2017; Sen et al., 2016). Additionally, SLICE-enabled pooled screens or scRNA-seq analysis with libraries expressing multiple sgRNAs may discover epistatic interactions between pairwise genetic perturbations, revealing relevant pathways and combination targets that synergize for potential therapeutic effects.

The SLICE pooled screening approach is flexible and versatile as it can be adapted to probe diverse genetic programs that regulate primary T cell biology. Primary T cell screens can be performed with various extracellular selective pressures and/or FACS-based phenotypic selections. We focused on CD8+ T cells, but showed that SLICE also can be employed in CD4+ T cells, and eventually may be generalizable to many other primary human cell types. We demonstrated that a suppressive pressure can be added to the screen, in our case an adenosine agonist, to identify gene perturbations that confer resistance. Future screens could be designed to overcome additional critical suppressive forces in the tumor microenvironment, such as suppressive cytokines, metabolites, nutrient depletion, or suppressive cell types including regulatory T cells or myeloid-derived suppressor cells. In summary, we have developed a novel pooled CRISPR screening technology with the potential to explore unmapped genetic circuits in primary human cells and to guide the design of engineered cell therapies.

STAR Methods

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Alexander Marson (alexander.marson@ucsf.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Isolation and Culture of Human CD8+ T Cells

Primary human T cells for all experiments were sourced from one of two origins: (1) residuals from leukoreduction chambers after Trima Apheresis (Blood Centers of the Pacific) or (2) fresh whole blood samples under a protocol approved by the UCSF Committee on Human Research (CHR#13–11950). Donors were de-identified, so no information on sex or gender was provided. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from samples by Lymphoprep centrifugation (STEMCELL, Cat #07861) using SepMate tubes (STEMCELL, Cat #85460). CD8+ T cells were isolated from PBMCs by magnetic negative selection using the EasySep Human CD8+ T Cell Isolation Kit (STEMCELL, Cat #17953) and used directly. When frozen cells were used (IncuCyte experiments), previously isolated PBMCs that had been frozen in Bambanker freezing media (Bulldog Bio, Cat #BB01) were thawed, CD8+ T cells were isolated using the EasySep isolation kit previously described, and cells were rested in media without stimulation for one day prior to stimulation. Cells were cultured in X-Vivo media, consisting of X-Vivo15 medium (Lonza, Cat #04–418Q) with 5% Fetal Calf Serum, 50mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10mM N-Acetyl L-Cysteine. After isolation, cells were stimulated with plate-bound anti-human CD3 (Cat #40–0038, clone UCHT1) at 10μg/mL and anti-human CD28 (clone CD28.2) at 5μg/mL (Tonbo, Cat #40–0289) with IL-2 at 50U/mL, at 1e6 cells/mL.

METHOD DETAILS

Lentiviral Production

HEK 293T cells were seeded at 18 million cells in 15 cm poly-L-Lysine coated dishes 16 hours prior to transfection and cultured in DMEM + 5% FBS + 1% pen/strep. Cells were transfected with the sgRNA transfer plasmids and 2nd generation lentiviral packaging plasmids, pMD2.G (Addgene, Cat #12259) and psPAX2 (Addgene, Cat #12260) using the lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent per the manufacturer’s protocol (Cat #L3000001). The following day, media was refreshed with the addition of viral boost reagent at 500x as per the manufacturer’s protocol (Alstem Cat #VB100). The viral supernatant was collected 48 hours post transfection and spun down at 300g for 10 minutes, to remove cell debris. To concentrate the lentiviral particles, Alstem precipitation solution (Alstem Cat #VC100) was added, mixed, and refrigerated at 4°C for four hours. The virus was then concentrated by centrifugation at 1500g for 30 minutes, at 4°C. Finally, each lentiviral pellet was resuspended at 100× of original volume in cold PBS and stored until use at −80°C.

Lentiviral Transduction and Cas9 Electroporation

24 hours post stimulation, lentivirus was added directly to cultured T cells at a 1:250 v/v ratio and gently mixed by tilting. Following 24 hours, cells were collected, pelleted, and resuspended in Lonza electroporation buffer P3 (Lonza, Cat #V4XP-3032) at 20e6 cells / 100μL. Next, Cas9 protein (MacroLab, Berkeley, 40μM stock) was added to the cell suspension at a 1:10 v/v ratio. Cells were electroporated at 20e6 cells per cuvette using the pulse code EH115 (Lonza, cat #VVPA-1002). The total number of cells for electroporation was scaled as required. Immediately after electroporation, 1mL of pre-warmed media was added to each cuvette and cuvettes were placed at 37 degrees for 20 minutes. Cells were then transferred to culture vessels in X-Vivo media containing 50U/mL IL-2 at 1e6 cells /mL in appropriate tissue culture vessels. Cells were expanded every two days, adding fresh media with IL-2 at 50U/mL and maintaining the cell density at 1e6 cells /mL.

CFSE Staining

Cultured cells were collected, spun, washed with PBS, and then resuspended at 1–10 million cells/mL in PBS. CFSE (Biolegend, Cat #423801) was prepared per the manufacturer’s protocol to make a 5mM stock solution in DMSO. At time of use, this stock solution was diluted 1:1000 in PBS for a 5μM working solution, and then added in a 1:1 v/v ratio to the cell suspension. After mixing, cells were incubated for 5 minutes in the dark at room temperature. The stain was then quenched with a volume of media that was 5× the stain volume (e.g. 2ml + 10ml), and incubated for one minute at room temperature in the dark. Cells were then spun down and resuspended in X-vivo media prior to restimulation.

For CFSE staining of arrayed cells that were edited with RNPs, cells were collected from multiple replicate plates and combined into a deep well 96-well plate. Cells were spun down in the deep-well plate and after decanting the media, resuspended in 0.5mL of PBS per well using a manual multichannel pipette. CFSE was prepared to make a 5uM working solution in PBS per the manufacturer’s protocol as described above. Next, 0.5mL of the 5μM CFSE was then added in a 1:1 v/v ratio to each well of cells using the multichannel pipette. After mixing, cells were incubated for 5 minutes in the dark at room temperature. The stain was then quenched with 1 mLs of X-Vivo media using a multichannel pipette, and incubated for one minute at room temperature in the dark. Cells were then spun down in the deep-well plate, CFSE was decanted, and then cells were resuspended in X-Vivo media prior to restimulation.

T Cell Proliferation Screen Pipeline

PBMCs from multiple healthy human donors were isolated from TRIMA residuals, as above. After CD8+ T cells isolation (Day 0), cells were stimulated with plate-bound anti-human CD3/CD28 and IL-2 at 50U/mL. The following day, 24 hours after stimulation (Day 1), cells were transduced with concentrated lentivirus encoding the pooled sgRNA library, as above. 24 hours after transduction (Day 2), cells were electroporated with Cas9 protein. Cells were then cultured in media with IL-2 at 50U/mL and split every two days, keeping a density of 1e6 cells/mL. On day 14, cells were CFSE stained and then restimulated with ImmunoCult Human CD3/CD28/CD2 T Cell Activator (STEMCELL, Cat #10970). ImmunoCult was used at 1/16 of the manufacturer’s recommended dose of 25μL/1e6 cells.. Four days later cells were FACS sorted based on CFSE level. Specifically, we defined the non-proliferating cells as those with the highest CFSE peak, and the highly proliferative cells as in the 3rd highest CFSE peak and below (Figure S1G). For the T cell proliferation screen with adenosine receptor 2A agonist, CGS-21680 (TOCRIS, Cat #1063), CGS- 21680 was first resuspended in DMSO for a stock solution of 10mM, and then added to media for a final concentration of 20μM.

Preparation of gDNA for Next-Generation Sequencing

After cell sorting and collection, genomic DNA was isolated from cell pellets using a genomic DNA isolation kit (Machery-Nagel, Cat #740954.20). Amplification and bar-coding of sgRNAs for the cell surface sublibrary was performed as described by Gilbert et al. (Gilbert et al., 2014). For the genome-wide screen, after gDNA isolation, sgRNAs were amplified and barcoded as in Joung et al. (Joung et al., 2017), with adaptation to using a two-step PCR protocol. Each sample was first divided into multiple 100μL reactions with 4μg of gDNA per reaction. Each reaction consisted of 50μL of NEBNext 2x High Fidelity PCR Master Mix (NEB, cat #M0541L), 4μg of gDNA, 2.5μL each of the 10μM read1-stagger-U6 and TRACR-read2 primers, and water to 100μL total. The PCR cycling conditions were: 3 minutes at 98°C, followed by 10 seconds at 98°C, 10 seconds at 62°C, 25 seconds at 72°C, for 20 cycles; and a final 2 minute extension at 72°C. After the PCR, all reactions were pooled for each sample and then purified using Agencourt AMPure XP SPRI beads (Beckman Coulter, cat #A63880) per the manufacturer’s protocol. Next 1 μL was taken from each purified PCR product to go into a second PCR for indexing. Each reaction included 5μL of PCR product, 25μL of NEBNext 2x Master Mix (NEB, cat #M0541L), 1.25μL each of the 10μM p5-i5-read1 and read2-i7-p7 indexing primers, and water to 50μL total per reaction. The PCR cycling conditions for the indexing PCR were: 3 minutes at 98°C, followed by 10 seconds at 98°C, 10 seconds at 62°C, 25 seconds at 72°C, for 10 cycles; and a final 2 minute extension at 72°C. Post PCR, the samples were SPRI purified, quantified using the Qubit ssDNA high sensitivity assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat #Q32854), and then analyzed on the 2100 Bioanalyzer Instrument. Samples were then sequenced on a HiSeq 4000 instrument (Illumina).

Arrayed Cas9 Ribonucleotide Protein (RNP) Preparation and Electroporation

Lyophilized crRNAs and tracrRNAs (Dharmacon) were resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCL (7.4 pH) with 150 mM KCl at a stock concentration of 160 μM and stored in −80°C until use. To prepare Cas9-RNPs, crRNAs and tracrRNAs were first thawed, mixed at a 1:1 v/v ratio, and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes to complex the gRNAs. Cas9 protein (Stock 40μM) was added at a 1:1 v/v ratio and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. Assembled RNPs were dispensed into a 96W V-bottom plate at 3μL per well. Cells were spun down, resuspended in Lonza P3 buffer at 1e6 cells per 20μL, and added to a V-bottom plate with RNPs. The cells/RNP mixture was transferred to a 96 well electroporation cuvette plate (Lonza, cat #VVPA-1002) for nucleofection using the pulse code EH115. Immediately after electroporation, 80μL of pre-warmed media was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 20 minutes. Cells were then transferred to culture vessels with 50U/mL IL-2 at 1e6 cells /mL in appropriate tissue culture vessels.

Flow Cytometry for the Arrayed Validation

All array-based validation studies were processed in 96-well round-bottom plates and read on an Attune NxT Flow Cytometer with a 96-well plate-reader. For the RNP-based proliferation validation assays for top targets from the genome-wide screen, cells were stained with CFSE in the 96-well format prior to restimulation as described in methods above. For the evaluation of activation marker levels on arrayed RNP-edited cells, the following antibodies were used: CD69 (Biolegend, cat #310904), CD154 (Biolegend, cat #310806), and CD8a (Biolegend, cat #301038).

Pooled sgRNA Library Construction

For the cloning of the targeted cell surface sublibrary, we followed the custom sgRNA library cloning protocol as described by Joung et al. (Joung et al., 2017). We utilized the pgRNA-humanized backbone (Addgene, plasmid #44248). To optimize this plasmid for cloning the library, we first replaced the sgRNA with a 1.9kb stuffer derived from the lentiGuide-Puro plasmid (Addgene, plasmid #52963) with flanking BfuAI cut sites. This stuffer was excised using the BfuAI restriction enzyme (NEB, #R0701) and the linear backbone was gel purified (Zymo, #D4007). We designed a targeted library to include all genes matching Gene Ontology for “Cell Surface”, “‘T cell receptor signaling pathway”, or “cytokine receptor activity”. In total we included 1211 genes with 4 guides per gene, and 48 non-targeting controls (Table S1). Guides were subsetted from the Brunello sgRNA library (Doench et al., 2016), and the pooled oligo library was ordered from Twist Bioscience to match the vector backbone. Oligos were PCR amplified and cloned into the modified pgRNA-humanized backbone by Gibson assembly as described by Joung et al. (Joung et al., 2017). For the genome-wide screens, the Brunello plasmid library in the lentiGuide-Puro backbone (Addgene, cat. 73178) was a gift from David Root and John Doench. The library was amplified using Endura ElectroCompetent Cells following the manufacturer’s protocol (Endura, Cat #60242–1).

SLICE adapted to CROP-Seq

The backbone plasmid used to clone the CROP-Seq library was CROPseq-Guide-Puro, purchased from Addgene (Addgene. Plasmid #86708). This library consisted of 20 gene targets (2 guides per gene selected from hits in the GW screen) and 8 non-targeting control guides, for a total of 48 guides (Table S5). Oligos for these library guides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) and cloned into the CROPseq-Guide-Puro plasmid backbone using the methods described by Datlinger et al. (Datlinger et al., 2017). Lentivirus was produced from this pooled plasmid library and used to transduce CD8+ T cells from two healthy donors, as above. 48 hours after transduction, 1e6 cells were resuspended in P3 buffer and 3μL of Cas9 (Stock 40μM) was added. Cells were transferred to a 96 well electroporation cuvette plate (Lonza, cat #VVPA-1002) for nucleofection using the pulse code EH115. 24 hours post nucleofection, cells were treated with 2.5ug/mL Puromycin for three days, and subsequently sorted for live cells using Ghost Dye 710 (Tonbo Biosciences, Cat #13–0871). Two days post sorting, cells were restimulated as above. 36 hours post restimulation, cells were collected, counted, and prepared for Illumina sequencing by Chromium™ Single Cell 3’ v2 (PN-120237), as per manufacturer protocol.

CROP-seq Guide Reamplification

For the guide reamplification, samples were amplified and barcoded using a two-step PCR protocol. First, each sample was divided into 8 PCR reactions with 0.1ng template of cDNA each. Each 25μL reaction consisted of 1.25μL P5 forward primer, 1.25μL Nextera Read 2 reverse primer, priming to the U6 promoter to enrich for guides, 12.5μL NEBNext Ultra II Q5 Master Mix (NEB, cat #M0544L), 0.1ng template, and water to 25μL. The PCR cycling conditions were: 3 minutes at 98°C, followed by 10 seconds at 98°C, 10 seconds at 62°C, 25 seconds at 72°C, for 10 cycles, and a final 2 minute extension at 72°C. After the PCR, all reactions were pooled for each sample and purified using Agencourt AMPure XP SPRI beads per the manufacturer’s protocol. Next, 1μL was taken from each purified PCR product to go into a second PCR for indexing. Each reaction included 1μL of PCR product, 12.5 μL NEBNext Ultra II Q5 Master Mix (NEB, cat #M0544L), 1.25μL P5 forward primer, 1.25μL Illumina i7 primer, and water to 25μL. The PCR cycling conditions were: 3 minutes at 98°C, followed by 10 seconds at 98°C, 10 seconds at 62°C, 25 seconds at 72°C, for 10 cycles, and a final 2 minute extension at 72°C. After the PCR, all reactions were SPRI purified and quantified using the Qubit dsDNA high sensitivity assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat# Q32854) and run on a gel to confirm size. Samples were then sequenced on a MiniSeq instrument (Illumina).

A375 and T cell in vitro Co-culture Assay

A375 melanoma cells were transduced with lentivirus to establish an RFP-nuclear tag (IncuCyte, Cat #4478) for optimal imaging on the IncuCyte live cell imaging system. 24 hours after stimulation, CD8+ T cells from healthy donors were transduced with virus containing the 1G4 NY-ESO1-reactive α95:LY TCR construct. Five days after transduction, cells were FACS sorted for a pure population of cells expressing the construct using the HLA-A2+ restricted NY-ESO-1 peptide (SLLMWITQC) dextramer-PE (Immundex, cat #WB2696). Cells were then expanded in X-Vivo media containing IL-2 at 50U/mL for a total of 14 days after initial stimulation. For initial optimization of this system, A375 cells were seeded at 24 thousand cells per well and T cells from two donors transduced with the 1G4 NY-ESO specific TCR were added at varying T cell to tumor cell ratios. The IncuCyte Caspase-3/7 red apoptosis reagent (IncuCyte, Cat #4704) was added to each well per the manufacturer’s instructions, and then imaged every 4 hours on the IncuCyte live cell imaging system. In parallel, A375 cells with the RFP-nuclear tag were seeded at 4,000 cells per well, and the same T cells from two donors transduced with the 1G4 TCR were added at the same ratios as in the caspase experiment, and these were imaged in parallel.

To test candidate gene targets, sorted 1G4+ T cells were edited as in the arrayed RNP experiments at day 10 post stimulation. On the day prior to co-culture, A375 cells were seeded at 5,000 cells per well in a 96W plate in 100μL of complete RPMI media. Complete RPMI media includes RPMI (Gibco, cat #11875093), 10% Fetal Calf Serum, 1% L-glutamine, 1% NEAA, 1% HEPES, 1% pen/strep, 50mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10mM N-Acetyl L-Cysteine. The next day, 1G4+ edited T cells were added to each well on top of the 5,000 A375 cells at indicated T cell to cancer cell ratios. T cells were resuspended in complete RPMI, with 150U/mL IL-2 and 6g/dL glucose, and added at 50ul per well. In experiments involving CGS-21680, the CGS-21680 was added at relevant doses to the media on the same day as the T cells were added. Plates were then imaged using the IncuCyte live cell imaging system, where the number of A375 RFP-positive nuclei were counted over time.

Oligo list

All guide RNAs and primers used in the study are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Analysis of Pooled CRISPR Screens

To identify negative and positive hits in our screens, we used the MAGeCK software to quantify and test for guide enrichment (Li et al., 2014). Abundance of guides was first determined by using the MAGeCK “count” module for the raw fastq files. For the genome-wide Brunello libraries, the 5’ trim length was set to remove the staggered offset introduced by the library preparation, by using the parameter: “—trim-5 23,24,25,26,28,29,30”. For the targeted libraries the constant 5’ trim was automatically detected by MAGeCK. We removed guides with an absolute count under 50 in more than 80% of the samples. To test for robust guide and gene-level enrichment, the MAGeCK “test” module was used with default parameters. This step includes media n ratio normalization to account for varying read depths. We used the non-targeting control guides to estimate the size factor for normalization, as well as to build the mean-variance model for null distribution, which is used to find significant guide enrichment. All donor replicates in each screen were grouped for analysis to account for biological noise. MAGeCK produced guide-level enrichment scores for each direction (i.e. positive and negative) which were then used for alpharobust rank aggregation (RRA) to obtain gene-level scores. The p-value for each gene is determined by a permutation test, randomizing guide assignments and adjusted for false discovery rates by the Benjamini–Hochberg method. Log2 fold change (LFC) is also calculated for each gene, defined throughout as the median LFC for all guides per gene target. Where indicated, LFC was normalized to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 to obtain the LFC Z-score.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis for Screen Hits

To find enriched annotations within screen hits, we used Gene Set Enrichment Analysis, as implemented in the fgsea R package (Sergushichev, 2016). The input for enrichment consisted of the LFC values for all genes tested in the screen. We used the KEGG pathways dataset as the reference gene annotation database, including only gene sets with more than 15 members and less than 500 members. For the external gene set for in vivo immunotherapy hits shown in Figure 2E, we used the 43 genes as determined by Zhou et al. (Zhou et al., 2014), having 3 or more shRNA guides with over 4-fold enrichment in T cells from tumor tissue compared to spleen. Normalized enrichment scores and p-values were determined by a permutation test with 10,000 iterations with same size randomized gene sets and adjusted with the FDR method.

Fitting CFSE Distributions for Arrayed Validation Screens

We used the FlowFit R package to extract quantitative parameters from the CFSE profiles across all samples (Rambaldi et al, 2014). As CFSE staining for arrays was done for individual populations of edited cells, the signal peak for the parental population might shift slightly from well to well. To account for this, for each well the stimulated well was compared to an identical unstimulated well, expected to have a single peak at the end of the assay. The FlowFit package implements the Levenberg-Marquadt algorithm to estimate the size and position of the parental population peak. We then used the fitted parameters from the unstimulated wells to fit the CFSE profiles of the corresponding stimulated cells. These CFSE profiles are modeled as Gaussian distributions, with log2 distanced peaks resulting from cell divisions and CFSE dilution. The fitted models were inspected visually, adjusting fitting parameters to minimize deviance from the original CFSE signal. The fitted models were used to calculate the proliferation index (Munson, 2010), defined as the total count of cells at the end of the experiment divided by the calculated original starting number of parent cells. This parameter is robust to variation in the starting CFSE staining intensities.

Analysis of SLICE Paired with Single-cell RNA-Seq

Pre-processing of the Illumina sequencing results from the 10X Genomics V2 libraries was performed with CellRanger software, version 2.0.0. This pipeline produces sparse numerical matrices for each sample, with gene-level counts of unique molecular identifiers (UMI) identified for all single cells passing default quality control metrics. These gene expression matrices were processed with Seurat R package (Butler et al., 2018), as described elsewhere (https://satijalab.org/seurat/pbmc3k_tutorial.html). Only cells with more than 500 genes identified were used for downstream analyses. Using Seurat, counts were log normalized, regressing out total UMI counts per cell and percent of mitochondrial genes detected per cell, and scaled to obtain gene level z-scores. Of note, all samples were processed simultaneously in the same experiment and thus sample origin was not regressed out (Butler et al., 2018). We then applied principal component analysis (PCA), using the 1,000 most variable genes across cells. The first 30 PCA components were used to construct a uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) to visualize single cells in a two dimensional plot, as in Figure 4A. Gene expression for single cells as displayed in Figure 4B was calculated as log10(UMI count + 1) and scaled. Clustering in Figure 4C, was performed by the Louvain algorithm on the shared nearest neighbor graph, as implemented by the FindClusters command from the Seurat R package. For synthetic bulk differential gene expression in Figure S4B, UMI counts per gene were summed for all cells with non-targeting control guides in each sample, and the DESeq2 R package was used to determine differentially expressed genes. For gene list enrichment analysis in cell clusters, the REACTOME database (Fabregat et al., 2018) was used as reference to generate Figure S4C.

To associate guides with identified cell barcodes, we processed both fastq files from the 10X libraries and from the re-amplification PCR. The read2 files were matched to the guide library using matchPattern as implemented in the ShortRead R package (Morgan et al. 2009). The pattern used was the sequence of the U6 promoter preceding the guide sequence appended to the 20bp library guide sequences (e.g. TGGAAAGGACGAAACACCGNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNN, where N denotes the guide sequence), allowing for 4 mismatches total. The mate Read1 pairs for reads with matched guides were used to determine the cell barcode and UMI assignment. We filtered out reads appearing less than twice and cells with more than one assigned guide. The Chi-square test was used to determine over-representation of cells with guides for the same gene target across cell-state driven clusters. Standardized residuals from the chi-square test were scaled and used to generate Figures 4E and S4F.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

Raw sequencing files for all screens performed are available at SRA database: SRP158611. Raw files for the single-cell RNA-Seq experiment are accessible through GEO Series accession number, GSE119450. All code used to analyze data and produce figures in this work is available by request.

Supplementary Material

Synthetic oligos used in this study: sgRNA library for targeting cell surface and TCR signaling genes, primers and synthetic crRNA for RNP arrays.

Output of MAGeCK analysis for pilot targeted screen, normalized counts and results for sgRNA and gene level enrichment.

Output of MAGeCK analysis for primary genome-wide screen.

Output of MAGeCK analysis for integrated replicates genome-wide screens.

Oligo sequences for Crop-Seq library.

Output of MAGeCK analysis for CGS-21680 and vehicle genome-wide screens.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank members of the Marson and Ashworth labs as well as Jeffrey Bluestone, Kole Roybal, Chun Jimmie Ye and Art Weiss for helpful suggestions and technical assistance. We thank Jim Wells and Amy Weeks for experimental insights throughout the conception and realization of the project. We thank Tom Norman and Jonathan Weissman for helpful discussions on Crop-Seq data, Chris Jeans (Macrolab) for reagents, Vin Nguyen and Eunice Wan for technical assistance with flow cytometry and single cell RNA-seq. The 1G4-TCR vector was a gift from Cristina Puig-Saus and Antoni Ribas. This research was supported by grants from the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy (PICI) and gifts from Jake Aronov and Galen Hoskin (A.M.). A.M. holds a Career Award for Medical Scientists from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and is an investigator at the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub. J.C. is a Damon Runyon Physician-Scientist Training Award fellow. The UCSF Flow Cytometry Core was supported by the Diabetes Research Center grant NIH P30 DK063720.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare competing financial interests: A.M. is a co-founder of Spotlight Therapeutics.A.M. has served as an advisor to Juno Therapeutics and is a member of the scientific advisory board at PACT Pharma. The Marson laboratory has received sponsored research support from Juno Therapeutics, Epinomics, Sanofi and a gift from Gilead. A.A. is a co-founder of Tango Therapeutics. A patent application is being filed based on the findings described here.

REFERENCES

- Aarts M, Georgilis A, Beniazza M, Beolchi P, Banito A, Carroll T, Kulisic M, Kaemena DF, Dharmalingam G, Martin N, et al. (2017). Coupling shRNA screens with single-cell RNA-seq identifies a dual role for mTOR in reprogramming-induced senescence. Genes Dev. 31,2085–2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson B, Norman TM, Jost M, Cho MY, Nuñez JK, Chen Y, Villalta JE, Gilbert LA, Horlbeck MA, Hein MY, et al. (2016). A Multiplexed Single-Cell CRISPR Screening Platform Enables Systematic Dissection of the Unfolded Protein Response. Cell 167, 1867–1882.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allard D, Turcotte M, and Stagg J (2017). Targeting A2 adenosine receptors in cancer. Immunol. Cell Biol. 95, 333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arafeh R, Qutob N, Emmanuel R, Keren-Paz A, Madore J, Elkahloun A, Wilmott JS, Gartner JJ, Di Pizio A, Winograd-Katz S, et al. (2015). Recurrent inactivating RASA2 mutations in melanoma. Nat. Genet. 47, 1408–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartelt RR, and Houtman JCD (2013). The adaptor protein LAT serves as an integration node for signaling pathways that drive T cell activation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 5, 101–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beavis PA, Henderson MA, Giuffrida L, Mills JK, Sek K, Cross RS, Davenport AJ, John LB, Mardiana S, Slaney CY, et al. (2017). Targeting the adenosine 2A receptor enhances chimeric antigen receptor T cell efficacy. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 929–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler A, Hoffman P, Smibert P, Papalexi E, and Satija R (2018). Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 411–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae H-D, Siefring JE, Hildeman DA, Gu Y, and Williams DA (2010). RhoH regulates subcellular localization of ZAP-70 and Lck in T cell receptor signaling. PLoS One 5, e13970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SS, Hu Z, and Zhong X-P (2016). Diacylglycerol Kinases in T Cell Tolerance and Effector Function. Front Cell Dev Biol 4, 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang JY, Jang IK, Hodes R, and Gu H (2007). Ablation of Cbl-b provides protection against transplanted and spontaneous tumors. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1029–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damgaard RB, Walker JA, Marco-Casanova P, Morgan NV, Titheradge HL, Elliott PR, McHale D, Maher ER, McKenzie ANJ, and Komander D (2016). The Deubiquitinase OTULIN Is an Essential Negative Regulator of Inflammation and Autoimmunity. Cell 166, 1215–1230.e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datlinger P, Rendeiro AF, Schmidl C, Krausgruber T, Traxler P, Klughammer J, Schuster LC, Kuchler A, Alpar D, and Bock C (2017). Pooled CRISPR screening with single-cell transcriptome readout. Nat. Methods 14, 297–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave VP, Keefe R, Berger MA, Drbal K, Punt JA, Wiest DL, Alarcon B, and Kappes DJ (1998). Altered functional responsiveness of thymocyte subsets from CD3delta-deficient mice to TCR-CD3 engagement. Int. Immunol. 10, 1481–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennehy KM, Elias F, Na S-Y, Fischer K-D, Hunig T, and Lühder F (2007). Mitogenic CD28 signals require the exchange factor Vav1 to enhance TCR signaling at the SLP-76-Vav-Itk signalosome. J. Immunol. 178, 1363–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit A, Parnas O, Li B, Chen J, Fulco CP, Jerby-Arnon L, Marjanovic ND, Dionne D, Burks T, Raychowdhury R, et al. (2016). Perturb-Seq: Dissecting Molecular Circuits with Scalable Single-Cell RNA Profiling of Pooled Genetic Screens. Cell 167, 1853–1866.e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doench JG (2018). Am I ready for CRISPR? A user’s guide to genetic screens. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 67–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doench JG, Fusi N, Sullender M, Hegde M, Vaimberg EW, Donovan KF, Smith I, Tothova Z, Wilen C, Orchard R, et al. (2016). Optimized sgRNA design to maximize activity and minimize off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 184–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duwel M, Welteke V, Oeckinghaus A, Baens M, Kloo B, Ferch U, Darnay BG, Ruland J, Marynen P, and Krappmann D (2009). A20 negatively regulates T cell receptor signaling to NF-kappaB by cleaving Malt1 ubiquitin chains. J. Immunol. 182, 7718–7728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabregat A, Jupe S, Matthews L, Sidiropoulos K, Gillespie M, Garapati P, Haw R, Jassal B, Korninger F, May B, et al. (2018). The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D649–D655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira MA, Vonk JM, Baurecht H, Marenholz I, Tian C, Hoffman JD, Helmer Q, Tillander A, Ullemar V, van Dongen J, et al. (2017). Shared genetic origin of asthma, hay fever and eczema elucidates allergic disease biology. Nat. Genet. 49, 1752–1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiil BK, and Gyrd-Hansen M (2016). OTULIN deficiency causes auto-inflammatory syndrome. Cell Res. 26, 1176–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraietta JA, Nobles CL, Sammons MA, Lundh S, Carty SA, Reich TJ, Cogdill AP, Morrissette JJD, DeNizio JE, Reddy S, et al. (2018). Disruption of TET2 promotes the therapeutic efficacy of CD19-targeted T cells. Nature 558, 307–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y, Paisie TK, Newman JRB, McIntyre LM, and Concannon P (2017). UBASH3A Mediates Risk for Type 1 Diabetes Through Inhibition of T-Cell Receptor-Induced NF-κB Signaling. Diabetes 66, 2033–2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]