Abstract

Adverse life experiences (ALEs) are associated with hyperalgesia and chronic pain, but the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood. One potential mechanism is hyperexcitability of spinal neurons (i.e., central sensitization). Given that Native Americans (NA) are more likely to have ALEs, and have a higher prevalence of chronic pain, the relationship between ALEs and spinal hyperexcitability might contribute to their pain risk. The present study assessed temporal summation of the nociceptive flexion reflex (TS-NFR; correlate of spinal hyperexcitability) and pain (TS-Pain) in 246 healthy, pain-free non-Hispanic whites (NHW) and Native Americans (NA). The Life Events Checklist (LEC-4) assessed the number of ALEs. Multilevel growth models were used to predict TS-NFR and TS-Pain, after controlling for age, perceived stress, psychological problems, negative and positive affect, and painful stimulus intensity. ALEs and negative affect were significantly associated with higher pain, but not enhanced TS-Pain. By contrast, ALEs were associated with enhanced TS-NFR. Race did not moderate these relationships. This implies that ALEs promote hyperalgesia as a result of increased spinal neuron excitability. Although relationships between ALEs and NFR/pain were not stronger in NAs, given prior evidence that NAs experience more ALEs, this might contribute to the higher prevalence of chronic pain in NAs.

Perspective:

This study found a dose-dependent relationship between adverse life experiences (ALE) and spinal neuron excitability. Although the relationship was not stronger in Native Americans (NA) than non-Hispanic whites, given prior evidence that NAs experience more ALEs, this could contribute to the higher prevalence of chronic pain in NAs.

Keywords: temporal summation, nociceptive flexion reflex, adverse life experiences, pain, negative affect, ethnic differences, trauma

Introduction

Native Americans (NA) have higher rates of chronic pain than other racial/ethnic groups,39 but the mechanisms involved in this pain disparity are poorly understood. One psychosocial factor that could contribute is exposure to adverse life events (ALEs, e.g., physical/sexual assault). Although much of the work on ALEs has focused on its psychological consequences (i.e., posttraumatic stress disorder, PTSD),12,52 ALEs may promote pain in the absence of PTSD. For example, ALE-exposed persons report more pain sites, greater somatization, more negative affect, and poorer perceived health than non-ALE-exposed persons.28 Given that NAs are more likely to experience ALEs,9,10,13,40,42,47,60,72,73 the ALEs-pain relationship may be particularly relevant for this minority group.

Interestingly, a dose-dependent effect has been found between ALEs and negative sequelae. For example, the number of adverse childhood experiences is associated with worse physical health/quality of life,8,18,26 somatic symptoms,38,45,49 mood/anxiety/stress symptoms,1–4,17,21,23,24,26,49,53,75 sleep disturbance,3,16 anger control,3 and corticotropin-releasing factor (stress hormone).93 It is therefore possible that a dose-dependent relationship exists between ALEs and pain.

The mechanisms linking ALEs to pain are not well understood, but one that is emerging is increased hyperexcitability of nociceptive spinal neurons (i.e., central sensitization).98 A model for studying this was first discovered by Mendell and Wall, who found that repetitive noxious stimuli with an interstimulus interval (ISI) ≤3-s produced a robust “windup” of dorsal horn neurons in animals.51 In humans, this is assessed from temporal summation of pain (TS-Pain) and involves the delivery of a train of constant-intensity stimuli that produces increased pain to the last stimulus relative to the first. Although most humans exhibit some TS-Pain, it is enhanced in persons with chronic pain;99 thus, it is believed that TS-Pain is a marker of amplification of ascending nociceptive input that promotes chronic pain.25,99 Consistent with the notion that ALEs increase spinal cord hyperexcitability, increased TS-Pain has been found in individuals with adverse childhood experiences101 and patients with functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID) with ALEs (compared to FGID patients without ALEs and healthy controls).79

One potential drawback of TS-Pain stems from the fact that pain ratings are used to make inferences about spinal nociceptive processes.65 Cortico-cortical circuits exist that could modulate pain solely at the supraspinal level without altering spinal neurons (e.g., 59,74) ). This would weaken the correlation between pain report and spinal nociception. 19,48,69,84 Consistent with this, catastrophizing is associated with TS-Pain, 22,32,34,65,86 but is unrelated to spinal nociception. 29,30,65,66,86,87 A more direct measure of spinal nociception could bolster the argument that ALEs are related to amplification of spinal neurons.

The current study examined the relationship between ALEs and temporal summation of the nociceptive flexion reflex (TS-NFR) and TS-Pain in a healthy, pain-free sample of 281 NAs and non-Hispanic whites (NHW). The NFR is a spinally-mediated nociceptive reflex assessed from electromyogram (EMG) whose reflex arc does not require supraspinal centers.78 Thus, NFR is used as a correlate of spinal nociception. Importantly, NFR magnitude summates in response to a train of noxious stimuli,5 and animal studies suggest this reflects hyperexcitability of spinal neurons.102,103 As a result, TS-NFR is a more direct measure of spinal neuron hyperexcitability.85

It is hypothesized that there will be a dose-dependent relationship between ALEs and TS, such that more ALEs will be associated with greater TS-NFR and TS-Pain. Race/ethnicity was included as a moderator to examine whether the relationship varies in NAs. Although evidence suggests it should be stronger in NAs,13 a small study of TS-NFR in NAs (n=22) found that TS-NFR was reduced (not enhanced), relative to NHWs (n=20).57 Thus, it is unclear if the relationship will be stronger or weaker in NAs.

Methods

Participants

All participants (N= 281; 156 women) were healthy, pain-free individuals recruited as part of the Oklahoma Study of Native American Pain Risk (OK-SNAP), a 2-day study investigating risk factors for chronic pain in Native Americans and non-Hispanic Whites. Native American participants in the current study represent tribal nations predominately from southern plains and eastern Oklahoma tribes. Most NHW and NA participants lived in the Northeastern area of Oklahoma, although recruitment was not limited to this area. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of The University of Tulsa, Cherokee Nation, and the Indian Health Service Oklahoma City Area Office. Participants were recruited via newspaper ads, fliers, email announcements, and online strategies (Facebook, Craigslist). Exclusion criteria included: 1) <18 years old, 2) history of cardiovascular, neuroendocrine, musculoskeletal, or neurological disorders, 3) current acute or chronic pain, 4) BMI ≥35 (due to difficulties obtaining the nociceptive flexion reflex [NFR]), 5) use of anti-depressant, anxiolytic, analgesic, stimulant, or anti-hypertensive medication, 6) current psychotic symptoms (assessed by Psychosis Screening Questionnaire 11) or substance abuse problems, and/or 7) an inability to read/speak English. Participants who identified as Native American were required to present verification of their heritage (e.g., Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood, tribal affiliation card) in order to participate.

Participants were given an overview of all procedures and told they could withdraw at any time. All participants provided verbal and written informed consent and received a $100 honorarium for the completion of each testing day (or $10/hour of non-completed days). Of the 281 participants enrolled in the larger study, 246 attended the testing day that included TS and completed some TS testing (see Results for additional sample details).

Power/Sensitivity Analysis

The present study is an ancillary analysis of data collected to study pain risk in NAs; therefore, the original sample size was not determined a priori to power this analysis. However, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to ensure that 246 participants would allow the detection of a meaningful effect size. Based on this N and α=.05, we obtained a power=.80 to detect individual predictors that explain ≥3.2% variance in the dependent variables (DV). Notably, this sensitivity analysis is based on less powerful ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models. The multilevel growth models used will actually exceed this power and will be powered to detect even smaller effects.

Procedures

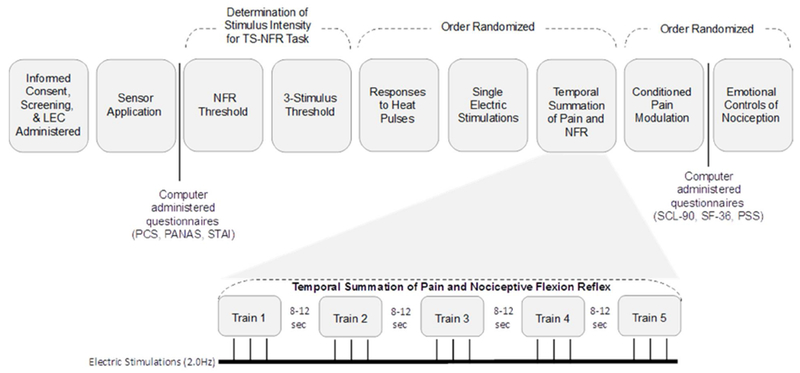

Testing was conducted over a 2-day period, each lasting 4-6 hours long. Figure 1 depicts procedures performed on the temporal summation testing day (note: other outcomes noted in the figure will be reported in subsequent papers). After consent was obtained, a thorough health screening was administered by the experimenter to ensure that all participants were eligible. Once inclusion was established, the Life Event Checklist for DSM-IV-TR (LEC) was administered to assess ALEs and then the experimenter applied electrodesand sensors.

Figure 1.

Testing day timeline and experimental procedures for the Temporal Summation of Pain and Nociceptive Flexion Reflex (TS-Pain; TS-NFR) testing day. The TS-NFR is expanded to show the 5 trains of 3 individually calibrated electrical stimulations, which were delivered at a frequency of 2.0 Hz. The interstimulus interval between each stimulation was randomized and ranged from 8-12 seconds

Pain tests were pseudorandomized with the exception that the assessment of NFR threshold and the 3-stimulation threshold were always administered first and second, respectively, so that suprathreshold stimulation intensity used during TS testing could be determined (see details below).

Apparatus, Electrode Application, and Signal Acquisition

Participants completed all testing in a sound-attenuated and electrically-shielded room. Throughout testing, the experimenter, who was located in an adjacent room, monitored participants via a video camera connected to an LCD television. Participants wore sound-attenuating headphones which provided verbal instructions for each task, and experimenters communicated with participants via a microphone connected to a 40 W audio amplifier (Radio Shack, Fort Worth, TX; Part #32–2054). All data, questionnaire, and stimuli presentation were controlled by a PC equipped with dual monitors, A/D board (PCI-PCI-6071E; National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA), and LabVIEW software (National Instruments; Austin, TX). One computer monitor presented questionnaires, pain rating scales, and picture stimuli to participants. A second monitor within the control room allowed for the experimenter to evaluate physiological signals and experimental progress.

An isolated, constant current stimulator (Digitimer DS7A; Hertfordshire, England) and bipolar stimulating electrode (Nicolet, 019-401400; Madison, WI) delivered electrical stimuli to the left ankle over the retromalleolar pathway of the sural nerve. Each stimulus was a train of five 1 ms rectangular wave pulses at 250 Hz. A computer controlled the timing of the electric stimulations (maximum stimulation intensity = 50 mA). Grass Technologies (West Warwick, RI), Model 151LT amplifiers (with AC Module 15A54 and Module 15A12) collected and amplified EMG physiological signals.

Two Ag-AgCl electrodes were placed over the biceps femoris muscle (10 cm superior to the popliteal fossa) to assess EMG associated with NFR. A common ground electrode was placed over the lateral epicondyle of the femur. To apply EMG and stimulating electrodes, the skin was first cleaned with alcohol and exfoliated using Nuprep gel (Weaver and Company, Aurora CO) until impedances were below 5 kΩ. All electrodes were filled with conductive gel (EC60; Grass Technologies) and applied to the skin via adhesive collars. The signal was sampled at 1000 Hz.

Questionnaires

Demographics and Health Exclusion.

A custom-made demographics form was used to assess background information for each of the participants (e.g., age, biological sex, socioeconomic status, health status). This information was used to describe the sample as well as to evaluate eligibility criteria.

Adverse Life Experiences (ALEs).

The Life Events Checklist (LEC) was used to assess ALEs.35 It includes 17 items assessing various stressful events: natural disaster, fire/explosion, transportation accident, serious accident at work/home/etc, exposure to toxic substance, physical assault, sexual assault, other unwanted sexual contact, combat exposure, captivity, life threatening illness, severe human suffering, sudden violent death, sudden unexpected death of someone close, serious harm/death you caused to someone else, other stressful event. The respondent indicates the range of proximity to the event by assessing if the event “happened to me,” “witnessed it,” or “learned about it.” The authors of the measure have shown that it is a reliable source for assessing ALEs, with test-retest agreement ranging from moderate to substantial.35 This scale was used to assess the number of different ALEs that participants endorsed as “happened to me.” Therefore, items in which the participant responded with “happened to me” were summed to yield a total ALE score that ranges between 0 and 17. Prior studies have found that the number of ALEs varies by the population studied: college sample (mean = 2.05),33 headache sufferers (mean = 2.47 to 2.71),58 substance dependent individuals with (mean = 5.93) and without (mean = 4.67) PTSD,89 and resettled refugees (mean = 9-10).83

Current Affect.

Positive and negative affect was assessed from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS).92 Each subscale consists of 10 items that measure positive and negative emotions, with subscales ranging from 0 to 40. Higher scores on each scale indicate greater positive or negative affect.

State Anxiety.

State anxiety was assessed by the 20-item state anxiety subscale of the State Trait Anxiety Inventory.81 The subscale ranges from 20-80, with higher scores indicating greater current anxiety.

Psychological Problems.

The Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) was used to assess psychological problems.20 The scale consists of 90 items that assess various psychological symptoms. The Global Severity Index (GSI) of the SCL-90-R was used to assess overall psychological problems. Scores range from 0 to 4 with higher scores indicating more problems.

Health Perceptions.

The general health perceptions subscale of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36)91 was used to assess perceptions of physical health. Furthermore, the bodily pain subscale was used to assess the degree of pain and interference due to pain that has occurred over the past 4 weeks (prior to the first testing day). For both scales, scores are standardized to range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better physical functioning.

Pain Catastrophizing.

Pain catastrophizing was assessed using the 13-item Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS).82 Scores for the PCS ranged from 0 to 52, with higher scores indicating greater catastrophic thoughts.

Pain Ratings

Following each electrocutaneous stimulation, participants rated the pain they experienced using a computer-presented visual analog scale (VAS), similar to ones used in prior research.64 Anchors corresponded to no pain and the most intense pain imaginable, and the computer converted the scores to numerical values between 0-100. Prior to testing, participants were trained by the experimenter on how to use the pain rating scales through both verbal instructions and a demonstration.

Determination of Stimulus Intensity for Temporal Summation Testing

To determine the suprathreshold stimulation intensity used during temporal summation testing, NFR threshold and 3-stimulation threshold were first assessed. The stimulus intensity was set at 120% of NFR threshold or 120% of 3-stimulation threshold, whichever was higher (in mA). We have previously shown that this ensures that NFRs are reliably elicited throughout testing.85 However, because the stimulus intensity is set at a physiological threshold, rather than a perceptual threshold (e.g., pain threshold), this introduces more inter-individual variability in perception of the stimulus (but more consistency in the size of the NFR magnitude). Because NFR threshold and 3-stimulation threshold assess spinal nociception, they can also be used to assess “static” (tonic) reactivity of the spinal cord to painful input, whereas TS-NFR assesses “dynamic” (summative) reactivity of the spinal cord to painful input.

Assessment of NFR Threshold.

Three ascending-descending staircases of electric stimuli determined NFR threshold. The first ascending-descending staircase began at 0 mA and increased in 2 mA steps until an NFR was detected. NFR was defined as a mean biceps femoris EMG response within the 90- to 150-ms post-stimulus interval that exceeded the mean biceps femoris EMG activity within the 60 ms baseline interval prior to the delivery of electric stimulus by at least 1.4 standard deviations.31,63 Following the detection of the first NFR, the electrical current decreased in 1 mA steps until an NFR was no longer detected (trough). The second and third ascending-descending staircases were detected using 1 mA steps. The stimulus intensity (mA) which elicited the 2 NFRs and 2 troughs of the last 2 ascending-descending staircases were averaged and comprised the NFR threshold. In between electrical stimulations, a time interval of at least 8 seconds but no longer than 12 seconds was used to reduce predictability and habituation.

3-Stimulation Threshold Assessment.

One ascending staircase, beginning at 0 mA and increasing in 2 mA steps, of 3 electric stimulations (0.5 s inter-stimulus interval [ISI; 2.0 Hz]) were delivered until an NFR was evoked by the third stimulus. The stimulus intensity at which the NFR was evoked was recorded as the 3-stimulation threshold.

Temporal Summation of Pain and NFR

5 trains of 3 suprathreshold stimuli (0.5 s ISI) were used to assess temporal summation. After each train of stimuli, participants were instructed to rate the pain intensity for all 3 stimulations, using a set of 3 computer-presented VASs. After the participant completed the ratings, there was an inter-train interval of 8-12 s. The baseline EMGs in the 60 ms prior to the third stimulus in the stimulus train were visually inspected in real-time by the experimenter for excessive muscle tension or voluntary movement. If the mean rectified EMG exceeded 5 μV, the train was repeated in order to ensure that EMG activity in the post-stimulus interval was not contaminated by muscle tension unrelated to the NFR.85 NFR magnitudes in response to each stimulus in the 3-stimulus train were calculated in d-units by first subtracting the 60-ms baseline prior to the first stimulus in each train from the EMG response 70-150 ms after each stimulus in the train. This difference was then divided by the average of the standard deviations of the rectified EMG from these two intervals. Note: the post-stimulus interval used here differs from our assessment of NFRs in response to single stimuli (i.e., 90-150 ms post-stimulus) because repeated stimulations with a short (0.5 s) ISI can result in a shorter NFR onset latency.85

Data Analysis

Prior to analyses, variables were examined for non-normality. Skewed distributions were transformed (i.e., log10 for right skew). Also, outliers were identified according to Wilcox’s recommended MAD-Median procedure with the criteria set to 2.24.95 Identified outliers were winsorized to the nearest non-outlier value. Alpha level was set to p<.05 (2-tailed) for all analyses.

Group differences on background characteristics were analyzed using independent t-tests (continuous variables) or chi-square tests (categorical variables). Ordinary least squares regression analyses were used to predict NFR threshold and 3-stimulation threshold from race, ALEs, and the interaction of Race × ALEs after controlling for Age, Sex, Perceived Stress, Psychological Problems (SCL-90-R GSI subscale), Negative Affect, and Positive Affect.

For primary analyses, multilevel growth models were conducted with pain ratings or NFR magnitudes as the dependent variable. Data for these models were kept in “long form,” meaning that each participant had multiple rows of data that corresponded to each stimulation they received. TS testing involved 5 trains of 3 stimulations, therefore each participant had 15 rows of data. Thus, participants served as level 2 units in the models and stimulations served as level 1 units. The within-subject variance covariance structure was modeled as a first-order autoregressive matrix (AR1) to account for the significant autocorrelation in the repeated measures. A variable called Stimulus Number (Stim1, Stim2, Stim3) was entered into these models as a continuous predictor to model the slope of temporal summation (i.e., the change in pain/NFR across the 3 stimulations in a train). Train Number was also entered as a predictor to account for variance in pain/NFR across the 5 trains. Control variables that were entered included: Age, Sex, Perceived Stress, Psychological Problems, Negative Affect, Positive Affect, and Suprathreshold Stimulus Intensity. (Note: Based on a reviewer’s recommendation, we also examined bodily pain as a control variable, but it was not a significant covariate in the model for TS-Pain [p=.335] or the model for TS-NFR [p=.96]. Further, including it did not change any of the conclusions; thus, it is not reported in the final models.) Adverse Life Experiences (ALEs), Race, and their interactions with Stimulus Number were the primary predictors of interest. All continuous variables were centered by subtracting the grand mean to reduce multicollinearity and aid interpretation. Categorical variables were contrast coded (Race: NHW=−1, NA=1; Sex: Male=−1, Female=1). The models included a random intercept and a random slope for Stimulus Number (to allow summation to vary across participants). Finally, the intercepts and slopes were allowed to covary to control for the law of initial values (i.e., pain/NFR that is higher in response to the first stimulus is less likely to increase across the 3 stimuli, and vice versa). Chi-squared difference tests were used to determine whether the models were significantly different from a no predictor model (akin to the omnibus F-test used in OLS linear regression).

To test primary hypotheses, the main effects of ALEs and Race examined whether these variables were associated with overall levels (i.e., the intercept) of pain/NFR. The interactions of ALEs X Stimulus Number and Race X Stimulus Number tested whether ALEs or race (respectively) were associated with TS-pain or TS-NFR. The ALEs X Race X Stimulus Number interaction tested whether the relationship between ALEs and TS differed in NAs.

Results

Final Sample

A total of 281 NA and NHW participants were enrolled in the study; however, only 246 had data available for analysis. 2 participants’ data were lost due to a computer malfunction, 19 completed the first day of testing but did not return for the second day that included TS testing, and 14 completed some testing but quit before TS testing.

Table 1 reports characteristics for those participants available for analysis and those who were not (this does not include the 2 persons with lost data). As shown, the only significant difference was in state anxiety at the beginning of the physiology testing day. Those without TS data had slightly lower anxiety. There were also trends for persons available for TS analyses to have higher psychological distress, higher perceived stress, and be of younger age, but these did not reach statistical significance at P<.05.

Table 1.

Differences between participants with and without temporal summation (TS) data

| TS (n=246) |

No TS (n=33) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Variable | M | SD | M | SD | t | p |

| Age (years) | 29.423 | 13.257 | 33.636 | 14.671 | 1.693 | 0.092 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 25.050 | 4.367 | 25.464 | 3.866 | 0.517 | 0.606 |

| Adverse Life Events (0-17) | 2.152 | 1.818 | 2.182 | 2.068 | 0.088 | 0.930 |

| Pain Catastrophizing (PCS; 0-52) | 10.248 | 8.417 | 8.219 | 7.024 | −1.305 | 0.193 |

| Negative Affect (PANAS; 0-40) | 3.212 | 3.180 | 2.406 | 2.474 | −1.380 | 0.169 |

| Positive Affect (PANAS; 0-40) | 18.445 | 7.395 | 20.250 | 8.359 | 1.279 | 0.202 |

| State Anxiety (STAI; 20-80) | 33.098 | 7.482 | 30.250 | 7.053 | −2.038 | 0.043 |

| Perceived Stress (PSS; 0-40) | 14.094 | 6.375 | 11.680 | 6.149 | −1.809 | 0.072 |

| Psychological Problems (SCL-90; 0-4) | 0.387 | 0.378 | 0.240 | 0.195 | −1.910 | 0.057 |

| General Health Scale (SF-36; 0-100) | 63.353 | 11.505 | 64.616 | 11.622 | 0.522 | 0.602 |

| Categorical Variable | N | % | N | % | X2 | p |

| Sex (female) | 135 | 55% | 19 | 58% | 0.086 | 0.770 |

| Race (Native American) | 118 | 52% | 18 | 48% | 0.504 | 0.478 |

Note. PCS=Pain Catastrophizing Scale. PANAS=Positive and Negative Affect Schedule. STAI=State Trait Anxiety Inventory. PSS=Perceived Stress Scale. SCL-90=Symptom Checklist 90. SF-36=Medical Outcomes Study Short Form, 36-item. Items in bold are statistically significant.

Characteristics of the 128 NHW and 118 NA participants with available data are noted in Table 2. NAs had a higher BMI, reported more psychological problems, required a higher suprathreshold stimulus intensity to evoke NFRs during TS testing (due to a higher NFR threshold), were more likely to be female, and more likely to cohabitate (P=.021) than NHW participants. There was also a trend for NAs to experience more ALEs (P=.087).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Native American (NA) and non-Hispanic white (NHW) individuals with available temporal summation data

| NHW (n=128) |

NA (n=118) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Variable | M | SD | M | SD | t | p |

| Age (years) | 28.281 | 13.425 | 30.661 | 13.016 | −1.409 | 0.160 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 24.258 | 3.862 | 25.925 | 4.729 | −2.984 | 0.003 |

| Adverse Life Events (0-17) | 1.961 | 1.706 | 2.359 | 1.918 | −1.716 | 0.087 |

| Pain Catastrophizing (PCS; 0-52) | 10.195 | 8.372 | 10.305 | 8.500 | −0.102 | 0.919 |

| Negative Affect (PANAS; 0-40) | 3.032 | 3.185 | 3.407 | 3.176 | −0.923 | 0.357 |

| Positive Affect (PANAS; 0-40) | 18.221 | 7.050 | 18.686 | 7.772 | −0.492 | 0.623 |

| State Anxiety (STAI; 20-80) | 32.496 | 7.285 | 33.746 | 7.666 | −1.308 | 0.192 |

| Perceived Stress (PSS; 0-40) | 13.492 | 6.173 | 14.759 | 6.552 | −1.554 | 0.121 |

| Psychological Problems (SCL-90; 0-4) | 0.340 | 0.338 | 0.439 | 0.413 | −2.054 | 0.041 |

| General Health Scale (SF-36; 0-100) | 64.397 | 11.677 | 62.212 | 11.253 | 1.488 | 0.138 |

| Bodily Pain Subscale (SF-36; 0-100) | 43.453 | 6.382 | 42.833 | 7.895 | 0.755 | 0.451 |

| NFR Threshold (0-50 mA) | 16.511 | 9.962 | 20.229 | 11.437 | −2.723 | 0.007 |

| 3-Stimulation Threshold (0-50 mA) | 13.813 | 6.718 | 15.423 | 7.345 | −1.797 | 0.074 |

| Suprathreshold Stimulus Intensity (0-50 mA) | 21.734 | 10.497 | 25.593 | 11.163 | −2.794 | 0.006 |

| Categorical Variables | N | % | N | % | χ2 | p |

| Sex (female) | 61 | 48% | 74 | 63% | 5.620 | 0.018 |

| Education | 7.078 | 0.132 | ||||

| <High school | 1 | 1% | 8 | 7% | ||

| High school graduate | 16 | 13% | 14 | 12% | ||

| Partial college | 69 | 54% | 54 | 46% | ||

| College graduate | 31 | 24% | 32 | 27% | ||

| Graduate/professional school | 10 | 8% | 9 | 8% | ||

| Employment | ||||||

| >40 hours per week | 28 | 22% | 34 | 29% | 3.701 | 0.296 |

| <40 hours per week | 59 | 47% | 44 | 38% | ||

| Retired | 5 | 4% | 2 | 2% | ||

| Unemployed | 34 | 27% | 36 | 31% | ||

| Income | 7.874 | 0.163 | ||||

| <$9,999 | 47 | 37% | 30 | 27% | ||

| $10,000-$14,999 | 15 | 12% | 11 | 10% | ||

| $15,000-$24,999 | 16 | 13% | 17 | 15% | ||

| $25,000-$34,999 | 11 | 9% | 15 | 13% | ||

| $35,000-$49,999 | 10 | 8% | 19 | 17% | ||

| >$50,000- | 27 | 21% | 21 | 19% | ||

| Marital Status | 9.771 | 0.021 | ||||

| Single | 97 | 76% | 72 | 62% | ||

| Married | 21 | 16% | 22 | 19% | ||

| Separated/divorce/widowed | 8 | 6% | 13 | 11% | ||

| Cohabitating | 2 | 2% | 10 | 9% | ||

Note. NHW=non-Hispanic white. NA=Native American. PCS=Pain Catastrophizing Scale. PANAS=Positive and Negative Affect Schedule. STAI=State Trait Anxiety Inventory. PSS=Perceived Stress Scale. SCL-90=Symptom Checklist 90. SF-36=Medical Outcomes Study Short Form, 36-item. NFR=Nociceptive Flexion Reflex. Items in bold are statistically significant.

During data processing/data cleaning it was noted that 11 participants (4 NHW males, 2 NHW females, 3 NA males, 2 NA females) had to be excluded from NFR analyses due to excess movement during testing. 8 participants (3 NHW males, 2 NA males, 3 NA females) were excluded from pain rating analyses because all stimuli were rated at the highest level (i.e., 100; creating a ceiling effect for TS-Pain).

Variable Conditioning

The ALE variable suffered from outliers. After winsorizing, the new range was 0 to 5 ALEs. Perceived stress also required winsorizing. Age, negative affect, and psychological distress (SCL-90 GSI) were all right skewed; so, they were log transformed (log10).

ALE Exposure

In the present study, 80% of participants reported experience at least one ALE. The percentage of persons reporting individual ALEs were: natural disaster (24%), fire/explosion (12%), transportation accident (48%), serious accident (11%), exposure to toxins (2%), physical assault (25%), assault with weapon (9%), sexual assault (7%), unwanted sexual experience (13%), combat exposure (1%), captivity (<1%), life threatening illness (2%), severe human suffering (1%), sudden violent death (2%), sudden unexpected death (33%), caused serious injury/harm/death (3%), other (19%).

NFR Threshold and 3-Stimulation Threshold

The regression model predicting NFR threshold was significant F(9, 232)=1.925, P=.049; however, the only significant predictor in the model was Age (B=0.125, P=.038). Race (B=1.460, P=.206), ALEs (B=0.311, P=.510), and the interaction (B=0.111, P=.802) were all non-significant. The regression model predicting 3-stimulation threshold was non-significant, F(9, 232)=0.528, P=.854, and no individual predictor was significant (all Ps>.25).

Temporal Summation of Pain (TS-Pain)

To briefly summarize findings, pain summated across the 3 stimuli in the trains; however, this summation was not related to ALEs or race. Nonetheless, more ALEs and greater negative affect were associated with greater overall pain during TS-Pain (but not pain summation).

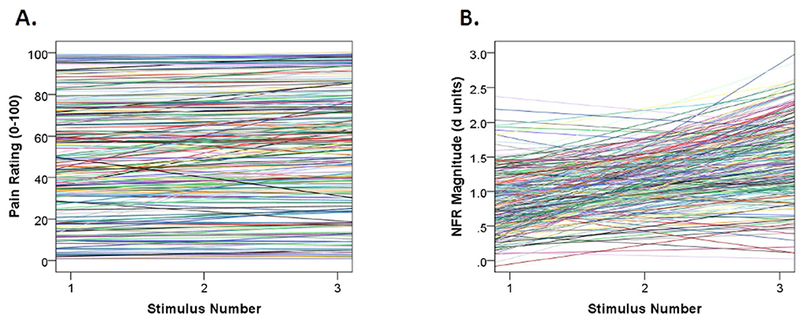

Figure 2 depicts the variance in slopes and intercepts for TS-Pain. Table 3 reports the results of the multilevel growth model analysis for pain and confirms that the variance in intercepts and slopes is significant.

Figure 2.

Plots depicting individual growth curves for temporal summation of pain (TS-Pain; panel A) and temporal summation of the nociceptive flexion reflex (TS-NFR; panel B). As depicted in the graphs and verified by the multilevel growth curve models, there is significant variance in both the intercepts (mean levels) and slopes (summation across the 3 stimulus trains) for both variables. This indicates that variance is available to be predicted by the growth models.

Table 3.

Results of multilevel growth curve analysis for temporal summation of pain (TS-Pain)

| 95% Confidence Interval |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | Estimate | SE | lower | upper |

| Intercept | 48.729* | 1.755 | 45.275 | 52.184 |

| Suprathreshold Stimulus Intensity | 0.610* | 0.159 | 0.297 | 0.922 |

| Train Number | 1.545* | 0.239 | 1.074 | 2.015 |

| Stimulus Number | 1.637* | 0.241 | 1.163 | 2.111 |

| Sex (female) | 0.668 | 1.715 | −2.711 | 4.048 |

| Age | 0.883 | 11.749 | −22.261 | 24.028 |

| Negative Affect (PANAS) | 15.366* | 5.789 | 3.961 | 26.770 |

| Perceived Stress (PSS) | −0.415 | 0.396 | −1.196 | 0.365 |

| Psychological Problems (SCL-90) | 16.429 | 29.282 | −41.256 | 74.114 |

| Positive Affect (PANAS) | −0.008 | 0.233 | −0.467 | 0.451 |

| Race | 0.917 | 1.740 | −2.510 | 4.345 |

| Adverse Life Events (ALEs) | 2.426* | 1.172 | 0.118 | 4.735 |

| Stim Number X Race | −0.041 | 0.231 | −0.497 | 0.415 |

| Stim Number X ALEs | 0.053 | 0.144 | −0.231 | 0.338 |

| Race X ALEs | −0.806 | 1.063 | −2.901 | 1.289 |

| Stim Number X Race X ALEs | 0.065 | 0.144 | −0.219 | 0.350 |

| 95% Confidence Interval |

||||

| Random Effects | Estimate | SE | lower | upper |

| AR1 diagonal | 163.878* | 21.256 | 127.091 | 211.313 |

| AR1 rho | 0.863* | 0.018 | 0.822 | 0.894 |

| Stimulus Number intercept variance | 585.298* | 63.681 | 472.895 | 724.418 |

| Intercept and slope covariance | −1.582 | 6.086 | −13.510 | 10.346 |

| Stimulus Number slope variance | 10.614* | 1.148 | 8.586 | 13.121 |

Note: Estimates are unstandardized relationships between the predictors and the dependent variable.

Estimates in bolded text are significant at P < 0.05. SE = standard error of coefficient/estimate.

AR1 = first-order autoregressive structure. PANAS = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule. PSS = Perceived Stress Scale. GSI = Global Severity Index of the Symptom Checklist 90. Sex was coded −1 = male and 1=female. Race was coded −1 = non-Hispanic white and 1 = Native American.

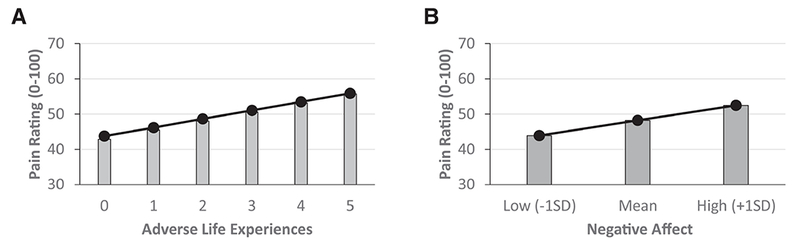

The chi-square difference test indicated that the model was statistically significant, Δχ2 (df=17)=849.10, P<.001. There was significant summation of pain as indicated by the main effect of Stimulus Number (P<.001), but this was not moderated by Race or ALEs. Nonetheless, the main effect of ALEs (P=.026) indicates that more ALEs is associated with higher pain (see Fig 3). There was also a significant main effect of Negative Affect (P=.029), indicating greater negative affect is also associated with more pain (see Fig 3).

Figure 3.

The predicted relationships between adverse life experiences and pain (panel A) and negative affect and pain (panel B). The predicted values are derived from the coefficients of the multilevel growth curve model. More adverse life experiences and greater negative affect were associated with higher reported pain during temporal summation of pain testing. This suggests that exposure to adverse life experiences and negative affect have independent effects on pain amplification. variance is available to be predicted by the growth models.

The main effect of Stimulus Intensity (P<.001) reflects that persons receiving a higher stimulus experienced more pain. The main effect of Train Number (P<.001) shows that pain increased across the 5 trains.

Results from the random effects in Table 3 show that there is still significant variance in the intercepts and slopes to be explained (Ps<.001), but that intercepts and slopes were unrelated (P=.795). This last fact indicates that the degree of TS-Pain was unrelated to the initial pain level evoked by the first stimulus in the series (e.g., more temporal summation of pain was not due to lower pain ratings to the first stimulus).

Temporal Summation of NFR (TS-NFR)

To briefly summarize findings, more ALEs was associated with greater TS-NFR. Race did not moderate this relationship, suggesting the effect of ALEs on NFR is similar in NA and NHW groups.

Figure 2 depicts the variance in slopes and intercepts for TS-NFR. Table 4 reports the results of the multilevel growth model analysis for NFR and confirms that the variance in intercepts and slopes is significant.

Table 4.

Results of multilevel growth curve analysis for temporal summation of the nociceptive flexion reflex (TS-NFR)

| 95% Confidence Interval |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | Estimate | SE | lower | upper |

| Intercept | 1.205* | 0.028 | 1.150 | 1.260 |

| Suprathreshold Stimulus Intensity | 0.000 | 0.002 | −0.005 | 0.004 |

| Train Number | −0.020* | 0.005 | −0.029 | −0.010 |

| Stimulus Number | 0.268* | 0.017 | 0.234 | 0.301 |

| Sex (female) | −0.031 | 0.026 | −0.083 | 0.020 |

| Age | 0.080 | 0.178 | −0.270 | 0.430 |

| Negative Affect (PANAS) | 0.039 | 0.089 | −0.137 | 0.214 |

| Perceived Stress (PSS) | 0.006 | 0.006 | −0.006 | 0.018 |

| Psychological Problems (SCL-90) | −0.294 | 0.461 | −1.201 | 0.613 |

| Positive Affect (PANAS) | 0.001 | 0.004 | −0.006 | 0.008 |

| Race | 0.008 | 0.027 | −0.046 | 0.061 |

| Adverse Life Events (ALEs) | 0.022 | 0.018 | −0.014 | 0.058 |

| Stim Number X Race | 0.019 | 0.017 | −0.015 | 0.053 |

| Stim Number X ALEs | 0.027* | 0.011 | 0.006 | 0.049 |

| Race X ALEs | −0.014 | 0.017 | −0.047 | 0.019 |

| Stim Number X Race X ALEs | −0.010 | 0.011 | −0.032 | 0.011 |

| 95% Confidence Interval |

||||

| Random Effects | Estimate | SE | lower | upper |

| AR1 diagonal | 0.132* | 0.004 | 0.125 | 0.139 |

| AR1 rho | 0.094* | 0.020 | 0.055 | 0.133 |

| Stimulus Number intercept variance | 0.146* | 0.015 | 0.120 | 0.178 |

| Intercept and slope covariance | 0.023* | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.037 |

| Stimulus Number slope variance | 0.054* | 0.006 | 0.043 | 0.068 |

Note: Estimates are unstandardized relationships between the predictors and the dependent variable.

Estimates in bolded text are significant at P < 0.05. SE = standard error of coefficient/estimate.

AR1 = first-order autoregressive structure. PANAS = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule. PSS = Perceived Stress Scale. GSI = Global Severity Index of the Symptom Checklist 90. Sex was coded −1 = male and 1=female. Race was coded −1 = non-Hispanic white and 1 = Native American.

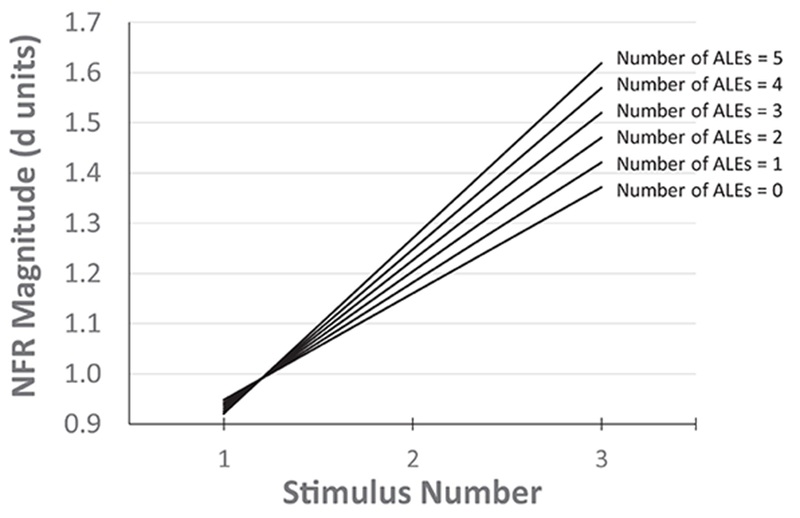

The chi-square difference test indicated that this model was statistically significant, Δχ2 (df=17)=1267.27, P<.001. There was significant summation of NFR as noted by the main effect of Stimulus Number (P<.001), but this effect was moderated by ALEs (P=.012). Specifically, persons reporting more ALEs experienced greater TS-NFR (see Fig 4). Race was unrelated to NFR (P=.781) and the summation of NFR (P=.265), and it did not moderate the relationship between ALEs and the summation of NFR (P=.346).

Figure 4.

The predicted relationship between adverse life experiences (ALEs) and temporal summation of the nociceptive flexion reflex (TS-NFR). Individual (simple) regression lines are based on the multilevel growth curve model. NFRs increased over the 3 stimulus train, indicating a temporary hyperexcitability of spinal neurons. However, persons who experienced a higher number of ALEs had greater TS-NFR, suggesting enhanced hyperexcitability (central sensitization) of spinal neurons in these individuals. This could serve as a risk factor for future chronic pain.

The main effect of Train Number (P<.001) shows that NFR magnitudes decreased across the 5 trains.

Results from the random effects in Table 4 show that there is still significant variance in the intercepts and slopes to be explained (Ps<.001), and the intercepts and slopes were related (P=.001). The significant covariance between the intercept and slope suggests that the degree of TS-NFR was related to the initial NFR magnitude evoked by the first stimulus in the series and underscores the importance of controlling for this issue.

Discussion

This study examined the relationships between ALEs and TS-NFR and TS-Pain. As predicted, ALEs were associated with enhanced TS-NFR, suggesting that exposure to ALEs promotes spinal neuron hyperexcitability in a dose-dependent manner. Although ALEs were not associated with enhanced TS-Pain, they were associated with higher pain ratings, suggesting that they promote hyperalgesia. The relationships between ALEs and pain/NFR were not moderated by race, indicating that NAs and NHWs did not differ. Notably, these relationships were not explained by age, negative affect, positive affect, sex, stress, psychological problems, because these variables were controlled in the models. Of the control variables, only negative affect was found to be a significant predictor of pain. Although ALEs were associated with TS-NFR, they were not associated with NFR threshold or 3-stimulation threshold. Implications are discussed below.

ALEs May Promote Central Sensitization and Hyperalgesia

Central sensitization is believed to promote the onset and maintenance of many chronic pain conditions (e.g., fibromyalgia).97 Although TS-Pain/TS-NFR and windup (the animal analog) are not synonymous with central sensitization,96 TS-NFR6 and TS-Pain25 are believed to assess physiological processes important to central sensitization, such as the activity of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and spinal neuron hyperexcitability. Moreover, past research has found that enhanced TS-Pain and TS-NFR are associated with chronic pain.7,46,97 We found that ALEs exert a dose-dependent influence on TS-NFR (more ALEs = greater NFR summation). This indicates persons with more ALEs have greater hyperexcitability of spinal neurons.

Although TS-NFR, NFR threshold, and 3-stimulation threshold all measure aspects of spinal nociception, ALEs were not associated with NFR threshold or 3-stimulation threshold. This likely reflects the underlying physiological mechanisms responsible. NFR threshold and 3-stimulation threshold are assumed mediated by α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid/kainite (AMPA) receptors,6,90,100 whereas TS-NFR is mediated by NMDA receptors.6,36 Thus, ALEs may have a stronger effect on NMDA-related mechanisms (i.e., central sensitization).

Notably, these effects were found in healthy, pain-free persons; therefore, ALEs may place individuals at future risk for chronic pain by promoting central sensitization. Interestingly, ALEs were not associated with enhanced TS-Pain. Rather, ALEs seem to promote general hyperalgesia because those that reported more ALEs experienced more overall pain in response to the electric stimuli. Together, it appears ALEs may be a risk factor for pain because they promote central sensitization and hyperalgesia.

Exposure to ALEs May Contribute to Native Americans (NA) Pain Disparities

Prior studies have found that NAs have a higher prevalence of chronic pain than NHWs and other racial/ethnic minorities.39 However, a few small prior studies found that NAs have higher pain thresholds/tolerances (i.e., hypoalgesia)56,57,80 and reduced TS-NFR.57 We previously speculated that this could represent a risk factor that is unique to NAs,56,57 because other racial/ethnic minorities at a high chronic pain risk show the opposite pattern (e.g., hyperalgesia, higher TS-Pain).61,71 To better understand the mechanisms contributing to NA pain we implemented the Oklahoma Study of Native American Pain Risk (OK-SNAP) from which the current data were drawn. Thus far, findings from OK-SNAP are not consistent with those prior studies. Instead, we find that, similar to other minority groups, NAs have lower pain tolerances (hyperalgesia) and report more pain-related negative affect in response to painful stimuli (Rhudy et al, manuscript under review).55

Relative to NHW, the current results indicate that NAs do not: 1) report more pain in response to electric stimuli, 2) have enhanced TS-NFR or TS-Pain, or 3) show a stronger relationship between ALEs and TS-NFR/TS-Pain. That said, ALEs may nonetheless represent an important pain risk pathway for NAs. Indeed, considerable evidence suggests that ALEs are more prevalent in NAs,9,10,13,40,42,43,47,60,72,73 which is consistent with the marginally higher rate we observed. Given this, the higher base rate of ALEs may help explain a higher rate of chronic pain in this population. Longitudinal studies are necessary to confirm this, but if true, then pharmacological (e.g., NMDA antagonists)6,54 and/or non-pharmacological (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy)41,76,88 interventions that reverse central sensitization could be used following exposure to ALEs to prevent the future chronic pain development.

Negative Affect May Contribute to NA Pain Disparities

Consistent with prior studies,14,44,50,67,68 we found that negative affect was associated with higher pain. Moreover, the relationship between negative affect and pain was found to be independent of the effect of ALEs on pain. Thus, our findings are consistent with a study that showed negative mood and ALEs independently predicted the progression from acute back pain to later disability.15 Taken together, greater negative affect may independently contribute to hyperalgesia and chronic pain risk.14,44,68,94

As noted above, we have found that NAs experience more negative affect in response to painful stimuli (Rhudy et al, under review).55 If this is also true of their response to clinical pain, as it is with other minorities,71 then negative affect may provide an additional pathway to pain risk for this population. Given that the relationship between negative affect and TS-Pain/TS-NFR was not a central aim of the present study, we did not formally test whether the negative affect and pain relationship was moderated by race. Nonetheless, we explored this interaction and it was non-significant (data not shown). Taken together, negative affect and ALEs may exert independent effects on pain processing and both may promote pain risk in NAs.

Why Do ALEs Influence TS-NFR, but not TS-Pain?

TS-NFR assesses spinal nociception.78 Thus, it should provide some insight into the pain signals relayed to the brain to produce pain perception. However, NFR and pain can diverge, because there are multiple modulatory circuits. For example, some are local (e.g., spinal-spinal, cortico-cortical) and some descend from supraspinal centers (cerebrospinal).27,59,74,77 Consistent with this, some psychosocial factors influence pain and TS-Pain, but not NFR or TS-NFR (e.g., catastrophizing),22,29,32,34,65,86 whereas others influence pain and NFR similarly (e.g., emotions).62,70 Thus, our findings suggest that ALEs promote spinal neuron hyperexcitability that amplifies ascending nociceptive input to promote general hyperalgesia, without leading to enhanced TS-Pain.

That said, these results should be interpreted with caution until they are replicated. Indeed, the divergence between TS-NFR and TS-Pain could have stemmed from ceiling effect. Given that those with higher ALEs already reported higher pain it may have limited the amount of pain summation that could occur. However, this was not supported by our finding that the covariance between the model intercept (initial pain rating) and the slope (degree of pain summation) was non-significant.

Alternatively, our failure to see enhanced TS-Pain could have resulted from the way pain was assessed. Electric stimulations were delivered with a 0.5 s ISI, so participants did not have time to make ratings between stimuli. Rather, they rated all 3 stimuli after the 3-stimulus train. As a result, exposure to the 3rd stimulus may have biased their ratings of earlier stimuli. Although this may have impacted our measurement of TS-Pain, it is not likely to have affected our measurement of pain more generally. So, our finding that ALEs and negative affect are associated with hyperalgesia is still valid. Moreover, this would not have affected our primary aim which was to examine the relationship between ALEs and TS-NFR.

Strengths and Limitations

This is the first study to examine the relationship between ALEs and TS-NFR in a large sample of NA and NHW men and women. Additionally, statistically powerful analyses were used to model the data complexity and control for potential confounds. Nonetheless, a few additional limitations should be noted.

First, the LEC limited the information gathered about ALEs. Similar to the commonly used Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) questionnaire,26 the LEC only provides the number of different events that a person experiences. It does not assess the event’s severity, the person’s reaction, or its chronicity/repetition. Further, the LEC does not assess for some less severe events or others ACEs (e.g., divorce, job loss) that might be important. Thus, future research is needed to examine the influence of ALEs not assessed by the LEC. Second, psychological diagnoses were not obtained, so we are unable to determine if clinically-significant distress impacted our results, or whether these results generalize to clinical samples (e.g., PTSD). Third, this study recruited healthy, pain-free subjects to examine the effect of ALEs before pain onset, so it is unclear if the results generalize to chronic pain samples. Finally, future studies are needed to determine whether augmented TS-NFR and hyperalgesia ultimately promote future chronic pain. However, preliminary analyses of OK-SNAP follow-up data suggest this.37

Summary

These findings imply ALEs have a dose-dependent effect on central sensitization (as assessed by TS-NFR) and hyperalgesia. This is independent of perceived stress, negative/positive affect, sex, age, and psychological symptoms. Only negative affect emerged as an independent predictor of pain. Although these relationships were not moderated by race, they could nonetheless contribute to the higher prevalence of chronic pain in NAs, because prior studies have noted that NAs are more likely to experience ALEs and pain-related negative affect.

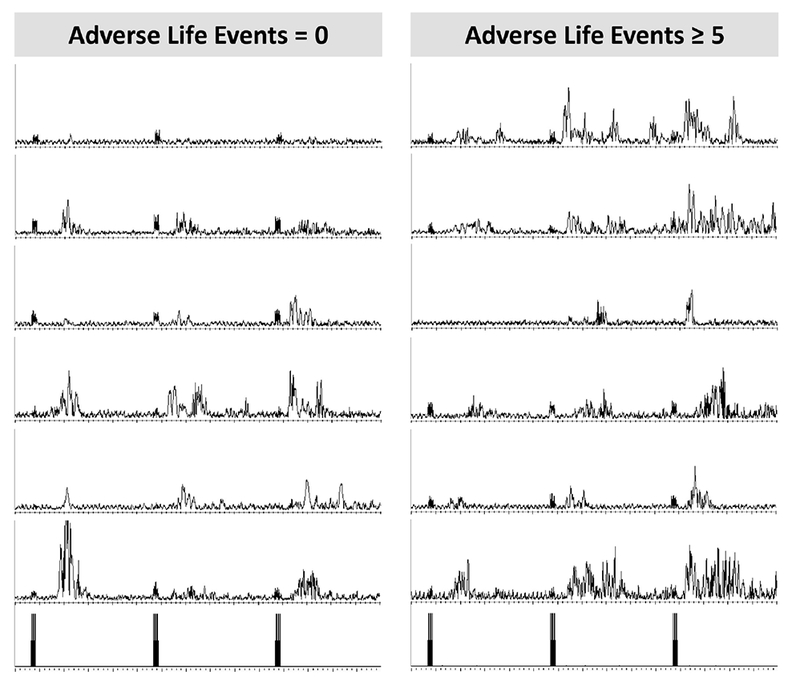

Figure 5.

Electromyogram (EMG) traces from the biceps femoris muscle used to measure temporal summation of the nociceptive flexion reflex (TS-NFR). On the left is 6 randomly selected participants that reported 0 adverse life experiences (ALEs) and on the right is 6 randomly selected participants reporting ≥5 ALEs. As illustrated, the summation in NFR across the 3-stimulation train (3 stimulations depicted in the bottom graphs) was greater in the group reporting more ALEs. y-axis range: 0-50 μV, x-axis range: 1500 ms.

Highlight Points.

Adverse Life Events (ALEs) were associated with increased spinal hyperexcitability

ALEs and negative affect were associated with hyperalgesia

These relationships were similar in Native Americans (NAs) and non-Hispanic whites

ALEs may promote central sensitization and hyperalgesia to increase pain risk

Acknowledgements:

Research reported was supported by the National Institute On Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institute of Health under Award Number R01MD007807. Edward Lannon, Shreela Palit, and Yvette Guereca were supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, Indian Health Service, or the Cherokee Nation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Afifi TO, Enns MW, Cox BJ, Asmundson GJ, Stein MB, Sareen J: Population attributable fractions of psychiatric disorders and suicide ideation and attempts associated with adverse childhood experiences. American journal of public health 98:946–952, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anda RF, Brown DW, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Dube SR, Giles WH: Adverse childhood experiences and prescribed psychotropic medications in adults. American journal of preventive medicine 32:389–394, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, Dube SR, Giles WH: The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience 256:174–186, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anda RF, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Chapman D, Edwards VJ, Dube SR, Williamson DF: Adverse childhood experiences, alcoholic parents, and later risk of alcoholism and depression. Psychiatric services 53:1001–1009, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arendt-Nielsen L, Brennum J, Sindrup S, Bak P: Electrophysiological and psychophysical quantification of temporal summation in the human nociceptive system. Eur J Appl Physiol 68:266–273, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arendt-Nielsen L, Petersen-Felix S, Fischer M, Bak P, Bjerring P, Zbinden AM: The effect of N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist (ketamine) on single and repeated nociceptive stimuli: a placebo-controlled xperimental human study. Anesth Analg 81:63, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banic B, Petersen-Felix S, Andersen OK, Radanov BP, Villiger PM, Arendt-Nielsen L, Curatolo M: Evidence for spinal cord hypersensitivity in chronic pain after whiplash injury and in fibromyalgia. Pain 107:7–15, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barile JP, Edwards VJ, Dhingra SS, Thompson WW: Associations among county-level social determinants of health, child maltreatment, and emotional support on health-related quality of life in adulthood. Psychology of Violence 5:183, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beals J, Manson SM, Whitesell NR, Spicer P, Novins DK, Mitchell CM: Prevalence of DSM-IV disorders and attendant help-seeking in 2 American Indian reservation populations. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62:99–108, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beals J, Novins DK, Whitesell NR, Spicer P, Mitchell CM, Manson SM, American Indian Service Utilization PE, Risk, Team PFP: Prevalence of mental disorders and utilization of mental health services in two American Indian reservation populations: mental health disparities in a national context. Am J Psychiatry 162:1723–1732, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bebbington P, Nayani T: The psychosis screening questionnaire. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 5:11–19, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brennstuhl MJ, Tarquinio C, Montel S: Chronic pain and PTSD: evolving views on their comorbidity. Perspectives in psychiatric care 51:295–304, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buchwald D, Goldberg J, Noonan C, Beals J, Manson S: Relationship between post-traumatic stress disorder and pain in two American Indian tribes. Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.) 6:72–79, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bushnell MC, Ceko M, Low LA: Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience 14:502–511, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casey CY, Greenberg MA, Nicassio PM, Harpin RE, Hubbard D: Transition from acute to chronic pain and disability: A model including cognitive, affective, and trauma factors. Pain 134:69–79, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapman DP, Wheaton AG, Anda RF, Croft JB, Edwards VJ, Liu Y, Sturgis SL, Perry GS: Adverse childhood experiences and sleep disturbances in adults. Sleep medicine 12:773–779, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Anda RF: Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. Journal of affective disorders 82:217–225, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corso PS, Edwards VJ, Fang X, Mercy JA: Health-related quality of life among adults who experienced maltreatment during childhood. American journal of public health 98:1094–1100, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DelVentura JL, Terry EL, Bartley EJ, Rhudy JL: Emotional modulation of pain and spinal nociception in persons with severe insomnia symptoms. Ann Behav Med 47:303–315, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Derogatis LR: SCL-90-R : symptom checklist-90-R : administration, scoring & procedures manual. Vol. [Minneapolis, Minn.]: [National Computer Systems, Inc.]; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman DP, Giles WH, Anda RF: Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: the adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics 111:564–572, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edwards RR, Fillingim RB, Maixner W, Sigurdsson A, Haythornthwaite J: Catastrophizing predicts changes in thermal pain responses after resolution of acute dental pain. J Pain 5:164–170, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edwards VJ, Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Anda RF: It’s ok to ask about past abuse. 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edwards VJ, Holden GW, Felitti VJ, Anda RF: Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: results from the adverse childhood experiences study. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:1453–1460, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eide PK: Wind-up and the NMDA receptor complex from a clinical perspective. European Journal of Pain 4:5–15, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, Marks JS: Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 14:245–258, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fields HL, Basbaum AI, Heinricher MM: Central nervous system mechanisms of pain modulation In: McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M, (eds). Textbook of Pain. 5th Edition ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone; 2006:pp 125–143 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fillingim RB, Edwards RR: Is Self-Reported Childhood Abuse History Associated With Pain Perception Among Healthy Young Women and Men? Clin J Pain 21:387–397, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.France CR, France JL, al’Absi M, Ring C, McIntyre D: Catastrophizing is related to pain ratings, but not nociceptive flexion reflex threshold. Pain 99:459–463, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.France CR, Keefe FJ, Emery CF, Affleck G, France JL, Waters S, Caldwell DS, Stainbrook D, Hackshaw KV, Edwards C: Laboratory pain perception and clinical pain in post-menopausal women and age-matched men with osteoarthritis: Relationship to pain coping and hormonal status. Pain 112:274–281, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.France CR, Rhudy JL, McGlone S: Using normalized EMG to define the Nociceptive Flexion Reflex (NFR) threshold: Further evaluation of standardized scoring criteria. Pain 145:211–218, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.George SZ, Wittmer VT, Fillingim RB, Robinson ME: Sex and pain-related psychological variables are associated with thermal pain sensitivity for patients with chronic low back pain. The Journal Of Pain: Official Journal Of The American Pain Society 8:2–10, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gibson LE, Anglin DM, Klugman JT, Reeves LE, Fineberg AM, Maxwell SD, Kerns CM, Ellman LM: Stress sensitivity mediates the relationship between traumatic life events and attenuated positive psychotic symptoms differentially by gender in a college population sample. J Psychiatr Res 53:111–118, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Granot M, Granovsky Y, Sprecher E, Nir RR, Yarnitsky D: Contact heat-evoked temporal summation: tonic versus repetitive-phasic stimulation. Pain 122:295–305, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gray MJ, Litz BT, Hsu JL, Lombardo TW: Psychometric Properties of the Life Events Checklist. Assessment 11:330–341, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guirimand F, Dupont X, Brasseur L, Chauvin M, Bouhassira D: The effects of ketamine on the temporal summation (wind-up) of the R(III) nociceptive flexion reflex and pain in humans. Anesth Analg 90:408–414, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huber FA, Kuhn BL, Lannon EW, Sturycz CA, Payne MF, Hellman N, Toledo TA, Guereca YM, DeMuth M, Palit S, Shadlow JO, Rhudy JL: Less Efficient Endogenous Inhibition of Spinal Nociception Predicts Chronic Pain Onset: A Prospective Analysis from the Oklahoma Study of Native American Pain Risk (OK-SNAP). Paper presented at: American Pain Society, 2019; Milwaukee, WC [Google Scholar]

- 38.Imbierowicz K, Egle UT: Childhood adversities in patients with fibromyalgia and somatoform pain disorder. European Journal of Pain 7:113–119, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jimenez N, Garroutte E, Kundu A, Morales L, Buchwald D: A Review of the Experience, Epidemiology, and Management of Pain among American Indian, Alaska Native, and Aboriginal Canadian Peoples. J Pain 12:511–522, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koss MP, Yuan NP, Dightman D, Prince RJ, Polacca M, Sanderson B, Goldman D: Adverse childhood exposures and alcohol dependence among seven Native American tribes. Am J Prev Med 25:238–244, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lackner JM, Mesmer C, Morley S, Dowzer C, Hamilton S: Psychological treatments for irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 72:1100, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Libby AM, Orton HD, Novins DK, Beals J, Manson SM: Childhood physical and sexual abuse and subsequent depressive and anxiety disorders for two American Indian tribes. Psychol Med 35:329–340, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu MC, Chen B: Racial and ethnic disparities in preterm birth: the role of stressful life events. Am J Obstet Gynecol 191:691–699, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lumley MA, Cohen JL, Borszcz GS, Cano A, Radcliffe AM, Porter LS, Schubiner H, Keefe FJ: Pain and emotion: a biopsychosocial review of recent research. J Clin Psychol 67:942–968, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maaranen P, Tanskanen A, Haatainen K, Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Hintikka J, Viinamaki H: Somatoform dissociation and adverse childhood experiences in the general population. The Journal of nervous and mental disease 192:337–342, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maixner W, Fillingim R, Sigurdsson A, Kincaid S, Silva S: Sensitivity of patients with painful temporomandibular disorders to experimentally evoked pain: evidence for altered temporal summation of pain. Pain 76:71–81, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manson SM, Beals J, Klein SA, Croy CD, Team A-s: Social epidemiology of trauma among 2 American Indian reservation populations. Am J Public Health 95:851–859, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martin SL, Kerr KL, Bartley EJ, Kuhn BL, Palit S, Terry EL, DelVentura JL, Rhudy JL: Respiration-Induced Hypoalgesia: Exploration of Potential Mechanisms. The Journal of Pain 13:755–763, 212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McBeth J, Macfarlane GJ, Benjamin S, Morris S, Silman AJ: The association between tender points, psychological distress, and adverse childhood experiences: a community-based study. Arthritis & Rheumatism: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology 42:1397–1404, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meagher MW, Arnau RC, Rhudy JL: Pain and emotion: effects of affective picture modulation. Psychosom Med 63:79–90, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mendell LM, Wall PD: Responses of single dorsal cord cells to peripheral cutaneous unmyelinated fibres. Nature 206:97, 1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moeller-Bertram T, Strigo IA, Simmons AN, Schilling JM, Patel P, Baker DG: Evidence for acute central sensitization to prolonged experimental pain in posttraumatic stress disorder. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.) 15:762–771, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Myers HF, Wyatt GE, Ullman JB, Loeb TB, Chin D, Prause N, Zhang M, Williams JK, Slavich GM, Liu H: Cumulative burden of lifetime adversities: Trauma and mental health in low-SES African Americans and Latino/as. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 7:243, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neugebauer V, Lucke T, Schaible HG: N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and non-NMDA receptor antagonists block the hyperexcitability of dorsal horn neurons during development of acute arthritis in rat’s knee joint. J Neurophysiol 70:1365, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Newsom GC, Toledo TA, Kuhn BL, Sturycz CA, Lannon EW, Palit S, Guereca YM, Payne MF, Hellman N, Shadlow JO, Rhudy JL: Does Altered Pain Sensitivity Contribute to Pain Risk in Native Americans?: Preliminary Findings from the Oklahoma Study of Native American Pain Risk (OKSNAP) [abstract]. Paper presented at: 17th IAPS World Congress on Pain 2018, 2018; Boston, MA, September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Palit S, Kerr KL, Kuhn BL, DelVentura JL, Terry EL, Bartley EJ, Shadlow JO, Rhudy JL: Examining emotional modulation of pain and spinal nociception in Native Americans: A preliminary investigation. Int J Psychophysiol 90:272–281, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Palit S, Kerr KL, Kuhn BL, Terry EL, DelVentura JL, Bartley EJ, Shadlow JO, Rhudy JL: Exploring pain processing differences in Native Americans. Health Psychol 32:1127–1136, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peterlin BL, Tietjen G, Meng S, Lidicker J, Bigal M: Post-traumatic stress disorder in episodic and chronic migraine. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain 48:517–522, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Piché M, Arsenault M, Rainville P: Cerebral and cerebrospinal processes underlying counterirritation analgesia. J Neurosci 29:14236–14246, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pole N, Gone JP, Kulkarni M: Posttraumatic stress disorder among ethnoracial minorities in the United States. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 15:35–61, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL III, Williams AK, Fillingim RB: A quantitative review of ethnic group differences in experimental pain response: do biology, psychology, and culture matter? Pain Medicine 13:522–540, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rhudy JL, Bartley EJ, Williams AE: Habituation, sensitization, and emotional valence modulation of pain responses. Pain 148:320–327, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rhudy JL, France CR: Defining the nociceptive flexion reflex (NFR) threshold in human participants: A comparison of different scoring criteria. Pain 128:244–253, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rhudy JL, Martin SL, Terry EL, DelVentura JL, Kerr KL, Palit S: Using multilevel growth curve modeling to examine emotional modulation of temporal summation of pain (TS-pain) and the nociceptive flexion reflex (TS-NFR). Pain 153:2274–2282, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rhudy JL, Martin SL, Terry EL, France CR, Bartley EJ, DelVentura JL, Kerr KL: Pain catastrophizing is related to temporal summation of pain, but not temporal summation of the nociceptive flexion reflex. Pain 152:794–801, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rhudy JL, Maynard LJ, Russell JL: Does in-vivo catastrophizing engage descending modulation of spinal nociception? J Pain 8:325–333, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rhudy JL, Meagher MW: Fear and anxiety: divergent effects on human pain thresholds. Pain 84:65–75, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rhudy JL, Meagher MW: The role of emotion in pain modulation. Curr Opin Psychiatry 14:241–245, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rhudy JL, Williams AE, McCabe KM, Rambo PL, Russell JL: Emotional modulation of spinal nociception and pain: The impact of predictable noxious stimulation. Pain 126:221–233, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rhudy JL, Williams AE, McCabe KM, Russell JL, Maynard LJ: Emotional control of nociceptive reactions (ECON): Do affective valence and arousal play a role? Pain 136:250–261, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Riley JL III, Wade JB, Myers CD, Sheffield D, Papas RK, Price DD: Racial/ethnic differences in the experience of chronic pain. Pain 100:291, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Robin RW, Chester B, Rasmussen JK, Jaranson JM, Goldman D: Prevalence and characteristics of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a southwestern American Indian community. Am J Psychiatry 154:1582–1588, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Robin RW, Chester B, Rasmussen JK, Jaranson JM, Goldman D: Prevalence, characteristics, and impact of childhood sexual abuse in a Southwestern American Indian tribe. Child Abuse Negl 21:769–787, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roy M, Piche M, Chen J-I, Peretz I, Rainville P: Cerebral and spinal modulation of pain by emotions. PNAS Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106:20900–20905, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sachs-Ericsson N, Cromer K, Hernandez A, Kendall-Tackett K: A review of childhood abuse, health, and pain-related problems: the role of psychiatric disorders and current life stress. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 10:170–188, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Salomons TV, Moayedi M, Erpelding N, Davis KD: A brief cognitive-behavioural intervention for pain reduces secondary hyperalgesia. PAIN® 155:1446–1452, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sandkühler J: Spinal cord plasticity and pain. Wall and Melzack’s textbook of pain 6:94–110, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sandrini G, Serrao M, Rossi P, Romaniello A, Cruccu G, Wilier JC: The lower limb flexion reflex in humans. Prog Neurobiol 77:353–395, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sherman AL, Morris MC, Bruehl S, Westbrook TD, Walker LS Heightened Temporal Summation of Pain in Patients with Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders and History of Trauma. Ann Behav Med 49:785–792, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sherman ED: Sensitivity to Pain:(With an Analysis of 450 Cases). Can Med Assoc J 48:437,1943 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Spielberger CD: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Vol. Palo-Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J: The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation. Psychological Assessment 7:524–532,1995 [Google Scholar]

- 83.Teodorescu DS, Heir T, Hauff E, Wentzel-Larsen T, Lien L: Mental health problems and post-migration stress among multi-traumatized refugees attending outpatient clinics upon resettlement to Norway. Scand J Psychol 53:316–332, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Terry EL, DelVentura JL, Bartley EJ, Vincent A, Rhudy JL: Emotional modulation of pain and spinal nociception in persons with major depressive disorder (MDD). Pain 154:2759–2768, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Terry EL, France CR, Bartley EJ, DelVentura JL, Kerr KL, Vincent AL, Rhudy JL: Standardizing procedures to study sensitization of human spinal nociceptive processes: Comparing parameters for temporal summation of the nociceptive flexion reflex (TS-NFR). Int J Psychophysiol 81:263–274, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Terry EL, Thompson KA, Rhudy JL: Experimental reduction of pain catastrophizing modulates pain report but not spinal nociception as verified by mediation analyses. Pain 156:1477–1488, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Terry EL, Thompson KA, Rhudy JL: Does pain catastrophizing contribute to threat-evoked amplification of pain and spinal nociception? Pain 157:456–465, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Thieme K, Flor H, Turk DC: Psychological pain treatment in fibromyalgia syndrome: efficacy of operant behavioural and cognitive behavioural treatments. Arthritis research & therapy 8:R121, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tull MT, McDermott MJ, Gratz KL, Coffey SF, Lejuez CW: Cocaine-related attentional bias following trauma cue exposure among cocaine dependent in-patients with and without post-traumatic stress disorder. Addiction 106:1810–1818, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Urban L, Thompson SW, Dray A: Modulation of spinal excitability: Co-operation between neurokinin and excitatory amino acid neurotransmitters. Trends In Neurosciences 17:432–438, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B: SF-36 Health Survey manual and interpretation guide. Vol. Boston: The Health Institute New England Medical Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A: Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 54:1063,1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Westfall NC, Nemeroff CB: The Preeminence of Early Life Trauma as a Risk Factor for Worsened Long-Term Health Outcomes in Women. Current Psychiatry Reports 17:2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wiech K, Tracey I: The influence of negative emotions on pain: behavioral effects and neural mechanisms. Neuroimage 47:987–994, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wilcox RR: Understanding and applying basic statistical methods using R. Vol John Wiley & Sons; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Woolf CJ: Windup and central sensitization are not equivalent. Pain 66:105–108, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Woolf CJ: Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain 152:S2–S15, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Woolf CJ, Thompson SW: The induction and maintenance of central sensitization is dependent on N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor activation; implications for the treatment of post-injury pain hypersensitivity states. Pain 44:293, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yarnitsky D, Granot M, Granovsky Y: Pain modulation profile and pain therapy: between pro- and antinociception. Pain 155:663–665, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yoshimura M, Nishi S: Excitatory amino acid receptors involved in primary afferent-evoked polysynaptic EPSPs of substantia gelatinosa neurons in the adult rat spinal cord slice. Neurosci Lett 143:131–134, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.You DS: The Impact of Adverse Childhood Events on Temporal Summation of Second Pain [Texas A & M University; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 102.You HJ, Dahl Morch C, Chen J, Arendt-Nielsen L: Simultaneous recordings of wind-up of paired spinal dorsal horn nociceptive neuron and nociceptive flexion reflex in rats. Brain Res 960:235–245, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.You HJ, Morch CD, Arendt-Nielsen L: Electrophysiological characterization of facilitated spinal withdrawal reflex to repetitive electrical stimuli and its modulation by central glutamate receptor in spinal anesthetized rats. Brain Res 1009:110–119, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]