Abstract

Studies have shown that the mTORC1/rpS6 signaling cascade regulates Sertoli cell blood-testis barrier (BTB) dynamics. For instance, specific inhibition of mTORC1 by treating Sertoli cells with rapamycin promotes the Sertoli cell barrier, making it “tighter.” However, activation of mTORC1 by overexpressing a full-length rpS6 cDNA clone (i.e., rpS6-WT, wild type) in Sertoli cells promotes BTB remodeling, making the barrier “leaky.” Also, there is an increase in rpS6 and p-rpS6 (phosphorylated and activated rpS6) expression at the BTB in testes at stages VIII–IX of the epithelial cycle, and it coincides with BTB remodeling to support the transport of preleptotene spermatocytes across the barrier, illustrating that rpS6 is a BTB-modifying signaling protein. Herein, we used a constitutively active, quadruple phosphomimetic mutant of rpS6, namely p-rpS6-MT of p-rpS6-S235E/S236E/S240E/S244E, wherein Ser (S) was converted to Glu (E) at amino acid residues 235, 236, 240, and 244 from the NH2 terminus by site-directed mutagenesis, for its overexpression in rat testes in vivo using the Polyplus in vivo jet-PEI transfection reagent with high transfection efficiency. Overexpression of this p-rpS6-MT was capable of inducing BTB remodeling, making the barrier “leaky.” This thus promoted the entry of the nonhormonal male contraceptive adjudin into the adluminal compartment in the seminiferous epithelium to induce germ cell exfoliation. Combined overexpression of p-rpS6-MT with a male contraceptive (e.g., adjudin) potentiated the drug bioavailability by modifying the BTB. This approach thus lowers intrinsic drug toxicity due to a reduced drug dose, further characterizing the biology of BTB transport function.

Keywords: adjudin, blood-testis barrier, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1, ribosomal protein S6, spermatogenesis, testis

INTRODUCTION

The blood-testis barrier (BTB) in the rat testis is constituted by tight junction (TJ), supported by coexisting basal ectoplasmic specialization (basal ES, a testis-specific, actin-rich anchoring junction), gap junction, and intermediate filament-based desmosome between adjacent Sertoli cells near the basement membrane (12, 68). Ultrastructurally, the BTB is supported by the closely located actin- and microtubule (MT)-based cytoskeletons (59, 70, 75). These cytoskeletons, in turn, support the different cell junctions that constitute the BTB, conferring the unusual strength of this tissue barrier in the testis, making it one of the tightest blood-tissue barriers in mammals (24, 65, 68). The BTB also divides the seminiferous epithelium into the basal and apical (adluminal) compartments. Undifferentiated (e.g., spermatogonial stem cells or Asingle spermatogonia) and differentiated spermatogonia (e.g., A1–A4 and type B spermatogonia) reside in the basal compartment (22, 27). Once preleptotene spermatocytes transformed from B spermatogonia in stage VII tubules at the basal compartment, they are transported by Sertoli cells across the BTB at late-stage VII through stage IX to enter the adluminal compartment to form late-stage spermatocytes. Thus, meiosis and postmeiotic spermatid development take place in a unique environment behind the BTB in the epithelium (28, 59, 70, 75, 80). As such, the BTB poses a hurdle for nonhormonal male contraception (or therapeutic treatment of testicular cancer) if contraceptives (e.g., adjudin) or drugs exert their effects behind the barrier to perturb germ cell development or destroy cancer cells. Consistent with this concept, other blood-tissue barriers also pose hurdles to deny the entry of therapeutic drugs to a target organ. Whereas the BTB and the blood-brain barrier (BBB) are considered to be two of the tightest blood-tissue barriers (12, 65), the BTB undergoes cyclic remodeling to support spermatogenesis during the epithelial cycle, such as at late-stage VII to VIII of the epithelial cycle in rodent testes, when the BTB undergoes extensive remodeling to support the transport of preleptotene spermatocytes across the immunological barrier (31, 80). As such, if the biomolecule(s) that support transient remodeling of the BTB (or other blood-tissue barriers) are identified, there is a possibility that such biomolecules can be used to improve drug bioavailability if they can codeliver the drug to the testis (or other organs).

Studies have shown that when mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), a nonreceptor Ser/Thr protein kinase known to regulate cellular energy status in virtually all cells (5, 38, 45, 66), is associated with the adaptor protein regulatory-associated protein of mTOR (Raptor), it creates mTORC1 (mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1) (5, 49, 66). mTORC1 has been shown to promote Sertoli cell BTB disruption through a surge in the expression of the downstream signaling protein rpS6, making the barrier “leaky” (53). Subsequent in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that this p-rpS6 upregulation is mediated downstream through downregulation of p-Akt1/2, and the net result of these changes leads to reorganization of actin cytoskeleton (48, 50, 53). This involvement of mTOR in testis function via its effects on Sertoli cell cytoskeletal organization and the activation of rpS6 have since been confirmed in genetic models in mice (7, 23). We have since prepared a quadruple phosphomimetic (i.e., constitutively active) mutant of rpS6 [i.e., p-rpS6-MT, in which the Ser (S) residue was converted to Glu (E) by site-directed mutagenesis using PCR, that is, p-rpS6-S235E/S236E and p-rpS6-S240E/S244E] (50). We have also shown that overexpression of this p-rpS6-MT in Sertoli cells in vitro (48, 50) and in the testis in vivo (41) perturbs the Sertoli cell barrier function, but it remains to be determined whether the BTB transport function is indeed perturbed. In this study, we sought to expand these earlier observations by further characterizing whether overexpression of p-rpS6-MT that modifies mTORC1 function could alter the transport function at the BTB, such as by lowering the effective dose of adjudin to perturb spermatogenesis, wherein adjudin serves as a candidate molecule. Furthermore, this study on BTB also serves as a model to assess whether p-rpS6-MT can be used to modify barrier function in other blood-tissue barriers such as the BBB in future studies. Although this approach may have minimal impact on male contraceptive development, it offers an interesting study model to characterize BTB biology mechanistically.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Adult Sprague-Dawley rats (male, 250–275 g body wt at ∼60–70 days of age) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Kingston, NY). Rats were housed in groups of two per cage at the Rockefeller University (RU) Comparative Bioscience Center (CBC) with free access to standard rat chow and water ad libitum at 22°C with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. The use of all animals in this report and detailed procedures of the experiments were approved by the RU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) with protocol nos. 15-780-H and 18-043-H. The use of recombinant DNA materials, including plasmid cDNA and transfection medium for in vivo studies, were approved by the RU Institutional Biosafety Committee. The use of cadmium chloride that served as the positive control in BTB integrity assay was also approved by the RU Laboratory Safety and Environmental Health (LS & EH). Animals were maintained in accordance with the applicable portions of the Animal Welfare Act and the guidelines in the Department of Health and Human Services publication Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All personnel involved in handling animals and the use of recombinant DNA materials had received appropriate trainings, attended appropriate safety courses, passed corresponding annual examinations, and approved by the IACUC at the Rockefeller University. Rats at specified time points were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation using slow (20–30%/min) displacement of chamber air from a compressed carbon dioxide tank in a euthanasia chamber approved by RU LS & EH.

Antibodies.

Antibodies were obtained commercially, unless specified. Antigens and animal sources used for the production of these antibodies and their working dilutions and the corresponding Resource Identification Initiative numbers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Antibodies used for different experiments in this report

| Antibody (RRID) | Host Species | Vendor | Catalog No. | Application (Working Dilution) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actin (AB_630836) | Goat | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-1616 | IB (1:500) |

| Arp3 (AB_476749) | Mouse | Sigma-Aldrich | A5979 | IF (1:200) |

| α-Tubulin (AB_2241126) | Mouse | Abcam | ab7291 | IF (1:500), IHC (1:300) |

| β-Tubulin (AB_2210370) | Rabbit | Abcam | Ab6046 | IF (1:500), IB (1:1,000) |

| β1-Integrin (AB_2130101) | Rabbit | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-8978 | IF (1:100) |

| β-Catenin (AB_138792) | Mouse | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 138400 | IF (1:100) |

| EB1 (AB_2141629) | Rabbit | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-15347 | IF (1:300) |

| Eps8 (AB_397544) | Mouse | BD Biosciences | 610143 | IF (1:100) |

| Dynein HC Antibody (R-325) (AB_2093483) | Rabbit | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-9115 | IF (1:50) |

| Formin1 (AB_2105244) | Mouse | Abcam | Ab68058 | IF (1:100), IB (1:500) |

| Laminin-γ3 (AB_2636817) | Rabbit | Cheng Laboratory | NA | IF (1:300) |

| N-cadherin (AB_2313779) | Mouse | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 33-3900 | IF (1:100) |

| MAP1a (AB_10903974) | Rabbit | Abcam | Ab101224 | IF (1:100), IB (1:300) |

| MAP1a (AB_649150) | Goat | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-8969 | IF (1:100) |

| MARK4 (AB_2140610) | Rabbit | Protein Technology Group | 20174-1-AP | IF (1:100), IB (1:2,000) |

| Myosin7a (AB_2148626) | Mouse | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-74516 | IF (1:100) |

| Nectin-2 (AB_2174166) | Goat | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-14802 | IF (1:100) |

| Nectin-3 (AB_2174276) | Goat | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-14806 | IF (1:100) |

| Occludin (AB_2533977) | Rabbit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 711500 | IF (1:100), IB (1:250) |

| p-rpS6 S235/S236 (AB_916156) | Rabbit | Cell Signaling Technology | 4858 | IB (1:2,000) |

| p-rpS6 S240/S244 (AB_10694233) | Rabbit | Cell Signaling Technology | 5364 | IB (1:1,000) |

| rpS6 (AB_331355) | Rabbit | Cell Signaling Technology | 2217 | IB (1:1,000) |

| Vimentin (AB_628437) | Mouse | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Sc-6260 | IF (1:500), IB (1:300) |

| ZO-1 (AB_2533938) | Rabbit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 61–7300 | IF (1:100), IB (1:250) |

| Goat IgG-HRP (AB_634811) | Bovine | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-2350 | IB (1:3,000) |

| Rabbit IgG-HRP (AB_634837) | Bovine | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-2370 | IB (1:3,000) |

| Goat IgG-Alexa 488 (AB_2534102) | Donkey | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A11055 | IF (1:250) |

| Goat IgG-Alexa 555 (AB2535853) | Donkey | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A21432 | IF (1:250) |

| Mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (AB_2534088) | Goat | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A11029 | IF (1:250) |

| Mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 555 (AB_141780) | Goat | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A21424 | IF (1:250) |

| Rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (AB_2576217) | Goat | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A11034 | IF (1:250) |

| Rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 555 (AB_2535850) | Goat | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A21429 | IF (1:250) |

| Biotinylated mouse IgG (AB_2313581) | Horse | Vector Laboratories | BA-2000 | IF (1:300) |

Arp3, actin-related protein 3; EB1, end-binding protein 1; Eps8, epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; IB, immunoblot; IF, immunofluorescence; IHC, immunohistochemistry; MAP1a, microtubule-associated protein 1a; MARK4, microtubule affinity-regulatory kinase 4; NA, not applicable; RRID, Research Resource Identifier (see https://scicrunch.org/resources for details); ZO-1, zonula occludens-1.

Treatment of rats with adjudin.

Rats in groups of three to four animals per treatment versus control groups were used for our studies. In short, a total of 10 rats were used per group, but the study was divided into three separate experiments to obtain sufficient samples for different experiments, excluding another set of rats (n = 3 rats/group) that assessed the optimal transfection frequency and adjudin dose to achieve the best phenotypes. It is of note that animals used for pilot experiments to establish initial experimental conditions were not included for analysis. Treatment of animals with adjudin was performed as described (15). In brief, adjudin was suspended in 0.05% methylcellulose in MilliQ water (wt/vol) at 20 mg/ml. Adjudin was administered to rats via oral gavage using a Cadence Science feeding needle (cat. no. 7916) at either 5 mg/kg body wt or 50 mg/kg body wt, which served as a positive control. Adjudin treatment with or without transfection with p-rpS6-MT using the regimen is shown in Fig. 1A.

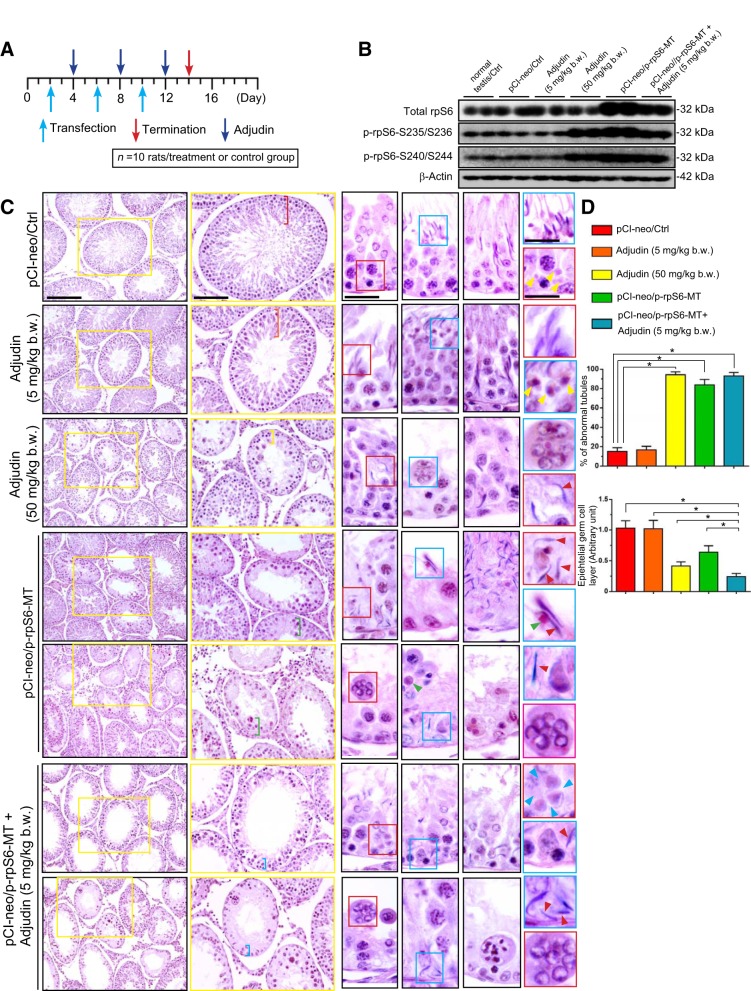

Fig. 1.

Overexpression of phosphorylated (activated) ribosomal protein S6-mutant (p-rpS6-MT) potentiates the effects of adjudin to induce germ cell exfoliation from the rat testis. A: regimen used for studies shown herein and subsequent studies in this report. Each group, including treatment and control groups, had n = 10 adult rats. B: representative results of immunoblot (IB) analysis from n = 6 experiments. C: histological analysis using cross-sections of paraffin-embedded testes previously fixed in modified Davidson fixative and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Images boxed in yellow were enlarged, and additional images were further enlarged and boxed in either red or blue and shown in corresponding insets. In blue and red insets in testes of control (pCI-neo/Ctrl) and low-dose adjudin (5 mg/kg body wt) groups, elongated spermatids were properly oriented, with their heads and tails pointed toward the basement membrane and tubule lumen, respectively. Phagosomes were found near the basement membrane (annotated by yellow arrowheads) in stage IX tubules in the pCI-neo/Ctrl group, but phagosomes were near the tubule lumen in VIII tubules when residual bodies engulfed by Sertoli cells were gradually turned into phagosomes (yellow arrowheads in blue boxed area in low dose adjudin group), consistent with an earlier report (17). However, in testes of the high-dose adjudin (50 mg/kg body wt), pCI-neo/rpS6-MT, or pCI-neo/p-rpS6-MT + adjudin groups, extensive defects were noted regarding 1) polarity in elongated spermatids (annotated by red arrowheads) in which their heads pointed 90–180° away from the intended orientation, 2) phagosome transport in which phagosomes were found near tubule lumen (annotated by green arrowhead) when they should have been transported to the base of the tubule for lysosomal degradation, 3) elongated spermatid transport since multiple step 19 spermatids were found near the base of the tubule when spermiation had occurred, and 4) the presence of multinucleated round spermatids and spermatocytes (blue arrowheads). Considerable thinning of the epithelium (annotated by colored brackets on the 2nd column) was also noted. Scale bars in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd columns are 280, 180, and 50 µm, respectively; insets in blue and red are 40 and 40 µm, respectively, which apply to corresponding images or insets. These results are representative findings of an experiment from n = 4 experiments using different rats, which yielded similar results. About 80 cross-sections of tubules were randomly scored from n = 4 rats, so that a total of 320 tubules were examined. D, top: %abnormal tubules based on the criteria as noted above. D, bottom: changes in thinning of the germ cell layer between control and different treatment groups versus pCI-neo/p-rpS6 + adjudin. *P < 0.01 by ANOVA.

Overexpression of p-rpS6-MT in adult rat testes.

The constitutively active quadruple phosphomimetic mutant of rpS6 cloned into the mammalian expression vector pCI-neo, namely, p-rpS6 mutant (i.e., pCI/neo-p-rpS6-MT), was obtained by site-directed mutagenesis using a full-length cDNA of rpS6-WT (wild-type), as earlier described (48, 50). In short, p-rpS6-S235/S236 and S240/S244 was converted to p-rpS6-S235E/S236E/S240E/S244E as described (48, 50). Plasmid DNA free of endotoxin was obtained by using Qiagen (Chatsworth, CA) Plasmid Plus Midi kits. In vivo transfection of testes was performed using 15 µg of plasmid DNA (for both treatment vs. control groups) containing 1.8 µl of Polyplus (Illkirch, France) in vivo-jetPEI reagent and suspended in sterile 5% glucose (wt/vol) at room temperature to a final transfection mix of 50 µl for each testis as, described earlier (8). This transfection mix was administered to each testis through a vertical insertion from the apical end of each testis, using a 28-gauage needle (0.5-in. needle length) attached to a 0.5-ml syringe. As the syringe was gently withdrawn from the testis, plasmid DNA contained in the transfection medium was gently released to avoid rapid hydrostatic pressure buildup to induce unwanted epithelial damage. Testes from animals were transfected on days 2, 6, and 10 (3 times) and adjudin at a low dose (5 mg/kg body wt) was administered to rats on days 4, 8, and 12 (for positive control, adjudin at 50 mg/kg body wt was administered once on day 4). Rats were terminated on day 14. The transfection efficiency using Polyplus in vivo-jetPEI reagent as a transfection was estimated to be ∼60%, as described (8) and detailed in a recent report (25). In brief, the transfection efficiency was estimated to be 60% by cotransfecting testes with DsRed2 (a variant of Discosoma sp. red fluorescence protein drFP583; Clontech) cloned into the pCI-neo (i.e., pCI-neo/DsRed2) plus pCI-neo/p-rpS6-MT using the regimen in Fig. 1A, as described earlier (40). A tubule was scored as successfully transfected when >15 red fluorescence (DsRed2) aggregates were detected in the seminiferous epithelium of a tubule cross-section by fluorescence microscopy. It was noted that most of the fluorescence was associated with the Sertoli cell cytosol and some early spermatocytes but not postmeiotic spermatids, particularly elongating/elongated spermatids, which are metabolically quiescent and highly differentiated germ cells.

BTB integrity assay in vivo.

The integrity of the BTB in the testis following treatment with p-rpS6-MT + adjudin at a low dose (5 mg/kg body wt) versus adjudin alone at a low (5 mg/kg body wt) or high (50 mg/kg body wt) dose and p-rpS6-MT alone, and compared with empty vector (pCI-neo/Ctrl) (negative control), was performed as described (8). In brief, rats under anesthesia with ketamine HCl (60 mg/kg body wt im) and with xylazine as an analgesic (10 mg/kg body wt im) were used. Testes were exposed through a small incision (∼0.5 cm) in the scrotum, and 100 µl of 10 mg/ml EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin, a membrane-impermeable biotinylation reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), was gently loaded into the testis using a 29-gauage needle. About 30 min thereafter, rats were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation, and testes were immediately removed and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen sections (∼6–7 µm in thickness) were obtained using a cryostat at −21°C and fixed in 4% PFA (paraformaldehyde in PBS, 10 mM sodium phosphate, and 0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.4 at 22°C) for 10 min, to be followed by Alexa Fluor 555-streptavidin (1:250) for 30 min. Microscopic slides were mounted in Prolong Gold Antifade reagent with DAPI to visualized cell nuclei. A functional and intact BTB blocked the biotin (i.e., red fluorescence following staining with Alexa Fluor 555-streptavidin) from entering the adluminal (apical) compartment, but red fluorescence (i.e., biotin) was found behind the BTB when it was compromised by p-rpS6-MT. Semiquantitative data to assess BTB integrity or damage will be obtained by measuring the distance (D) traveled by the biotin (DBiotin): the radius of a seminiferous tubule (STRadius). For oblique sections of tubules, STRadius was the average of the shortest and the longest distance from the basement membrane. About 60 randomly selected tubules from each testis of n = 3 rats (including treatment and negative and positive control groups) were quantified with a total of ∼180 tubules. Positive controls were rats treated with cadmium chloride (3 mg/kg body wt ip) for 4 days, which is known to induce irreversible BTB disruption (32, 79). This semiquantitative analysis is important to assess whether overexpression of p-rpS6-MT and adjudin at a low dose (5 mg/kg body wt) was considerably more than p-rpS6-MT overexpression alone than low (5 mg/kg body wt) or high dose (50 mg/kg body wt) alone versus pCI-neo/Ctrl (empty vector) control.

Lysate preparation and immunoblot analysis.

Lysates were obtained from testes for immunoblotting as described (8, 41). In brief, testes were lysed in lysis buffer [50 mM Tris, pH 7.4 at 22°C, containing 0.15M NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40 (wt/vol), 2 mM EGTA, and 10% glycerol (vol/vol), freshly supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors containing 1 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzene sulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 0.05 mM bestatin, 0.05 mM sodium EDTA, 15 µM E64 (trans-epoxysuccinyl-L-leucylamido-(4-guanidino)butane), 1 mM pepstatin, 4 mM sodium tartrate dihydrate, 5 mM NaF, and 3 mM β-glycerophosphate disodium salt] as described (41). Immunoblot analysis was performed using a homemade enhanced chemiluminescence kit to visualize target proteins with the corresponding antibodies (Table 1) as described (54). Immunoblot signals were detected using an ImageQuant LAS 4000 mini (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) Imaging system and ImageQuant software (version 1.3). Protein band intensities were obtained and compared by ImageJ 1.45s obtained from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD) at https://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij. All samples within an experimental set, including all treatment and control groups, were processed simultaneously (in replicates) to avoid interexperimental variations. A total of n = 3 independent experiments from different rats were performed, which yielded similar results for statistical comparisons.

Histology and immunofluorescence analysis.

Histology was performed using testes fixed in modified Davidson fixative (39), embedded in paraffin and sectioned to ~5 µm thickness using a microtome. These sections were de-paraffinized, rehydrated, and subjected to antigen retrieval, to be followed by hematoxylin and eosin staining as described (41). For immunofluorescence (IF) analysis (or dual-labeled immunofluorescence analysis), frozen cross-sections (7 µm in thickness) of testes were obtained in a cryostat at −21°C and postfixed in 4% PFA (wt/vol, in PBS), and immunofluorescence staining was performed using corresponding specific antibodies and appropriate secondary antibodies listed in Table 1, as described earlier (8), for all target proteins, except for MAP1a and dynein 1, wherein paraffin sections (7 µm in thickness) of testes were fixed in modified Davidson fixative and Bouin fixative, respectively. F-actin in testis sections was visualized by either fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated phalloidin or rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (Invitrogen-Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and β-tubulin was visualized by using a specific anti-β-tubulin antibody as described (69). Fluorescent images were acquired using a Nikon Eclipse 90i Fluorescence Microscope System equipped with a Nikon Ds-Qi1Mc and Nikon DS-Fi1 digital cameras and the Nikon NIS Elements Imaging Software. Image files were then analyzed by using Photoshop in Adobe (San Jose, CA) Creative Suite (version 6.0) for image overlays to assess protein colocalization for dual-labeled immunofluorescence analysis. For histological analysis, images were acquired using an Olympus BX61 Microscope with a built-in Olympus DP-71 digital camera, using the Olympus MicroSutie Five software package (version 1224; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). All images were unaltered original images without manipulation. At least 500 cross-sections were examined and acquired for analysis so that images presented in this report represented the unbiased general observations. All histology and IF data shown in corresponding figures were the result of a representative experiment. However, each experiment was from n = 3 independent experiments using cross-sections of testes from different rats. All samples within an experimental set, including treatment and control groups, were processed simultaneously for either histological or immunofluorescence analysis, and all images across treatment and control groups were captured in the same experimental session to avoid interexperimental variations. Also, negative controls using corresponding normal animal serum, depending on the source of animals used for primary antibody preparations, to substitute the primary antibody, served as an additional negative control in IF. In some selected target proteins for IF (e.g., occludin, ZO-1, N-cadherin, β-catenin), changes in the distribution of proteins were assessed by measuring fluorescence signals at the BTB that lay adjacent to the basement membrane in treatment groups versus the control (i.e., pCI-neo/Ctrl). At least 80 cross-sections of tubules from a testis were randomly selected from each group with n = 4 rats, so that a total of 320 tubules were scored.

Assessment of defects in spermatogenesis.

Defects in spermatogenesis were assessed by histological analysis. If cross-section of a tubule displayed any one of the following defects, it was classified to have defects in spermatogenesis. However, each tubule usually had two to three noted defects, as shown in Fig. 1. In short, criteria of defects in spermatogenesis in the cross-section of a randomly scored seminiferous tubule were as follows: 1) germ cell loss with >15 germ cells (usually elongating spermatids, round spermatids and spermatocytes) found in tubule lumen in non-stage VIII tubules, 2) appearance of multinucleated round spermatids (or spermatocytes), 3) defects in spermatid polarity in which elongating/elongated spermatocytes no longer had their heads pointed toward the basement membrane but deviated by 90°-180° from the intended orientation, 4) defects in spermatid transport wherein step 19 elongated spermatids were trapped in the seminiferous epithelium alongside with step 9–14 in stages IX–XIV tubules due to failure in spermiation because of the damaged track-like structures conferred by MTs to support their transport across the epithelium, and 5) defects in phagosome transport in which phagosomes were found in adluminal compartment instead of at the base of the epithelium in non-stage VIII tubules. However, we also assessed thinning of the seminiferous epithelium due to germ cell exfoliation in a treatment group versus corresponding staged tubules in the control group. It was noted that by using this as the criterion, the differences between the pCI-neo/p-rpS6-MT + adjudin treatment group were readily noted when compared with the p-rpS6, low-dose, and also high-dose adjudin group. About 80 cross-sections of tubules were randomly scored from a rat of n = 4 rats, so that a total of 320 tubules were randomly examined.

Statistical analysis.

Each data point represents means ± SD of n = 3 independent experiments using different rats. For semiquantitative analysis, such as by quantifying changes in tubule diameter or BTB integrity assay, ≥80 cross-sections of tubules from a testis were randomly scored from n = 3–4 rats in each experimental versus control groups. Statistical significance for evaluation of four measurements, such as the pCI-neo/p-rpS6-MT + adjudin (low dose, 5 mg/kg body wt) versus pCI-neo/p-rpS6-MT, adjudin (low dose, 5 mg/kg body wt), adjudin (high dose, 50 mg/kg body wt), and pCI-neo/Ctrl (empty vector) groups, was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Overexpression of p-rpS6-MT potentiates the disruptive effects of adjudin on spermatogenesis through changes in the permeability of the BTB.

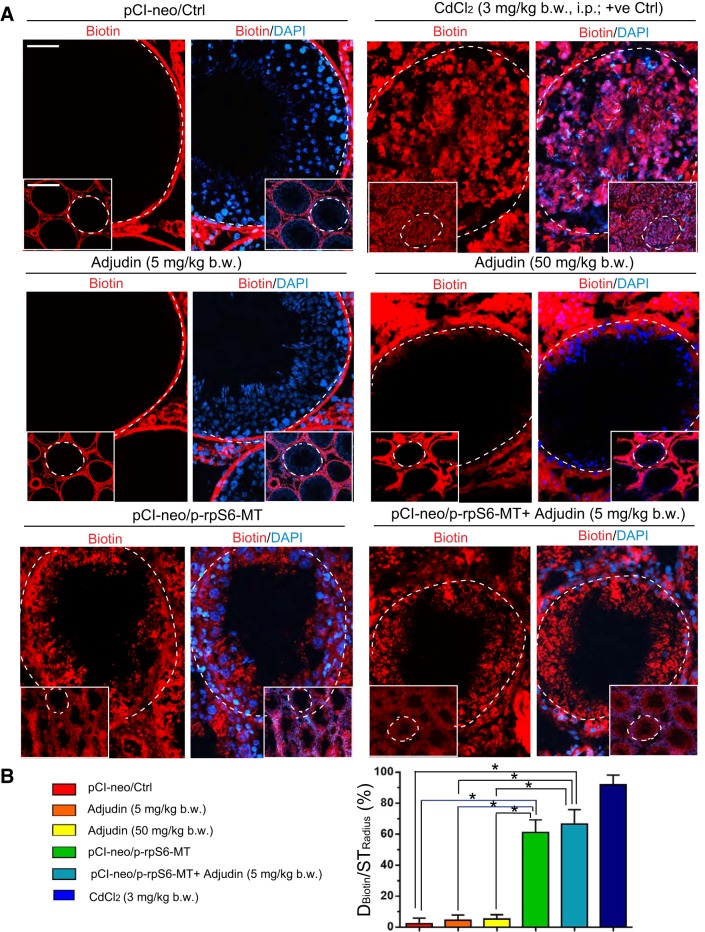

rpS6 is the downstream signaling protein of mTORC1 (i.e., mTOR + Raptor) (38, 47), shown earlier to impede Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier in vitro by making the barrier “leaky” transiently (48, 50, 53). A quadruple phosphomimetic (i.e., constitutively active) mutant, designated as p-rpS6-MT, in which the four amino acid residues at the active sites were converted by site directed mutagenesis from Ser (S) to Glu (G), namely p-rpS6-S235E/S236E/S240E/S244E, was prepared and cloned into the mammalian expression vector pCI-neo (Promega) as described (50). Overexpression of this p-rpS6-MT in Sertoli cells in vitro (48, 50) or in testes in vivo (41) was shown to be considerably more active than rpS6-WT (wild-type, i.e., full-length cDNA encoding rat rpS6) to induce the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier disruption in vitro or in vivo (41, 48, 50). The regimen shown in Fig. 1A was established based on pilot experiments by overexpression of p-rpS6-MT, coupled with treatment of these rats with a low dose of adjudin (5 mg/kg body wt by oral gavage) known to have no detectable effects on spermatogenesis per se (15). In short, we sought to examine whether a transient “opening” of the BTB would potentiate the effects of adjudin at a low dose (i.e., 5 mg/kg body wt), which had no effects on the status of spermatogenesis per se (Fig. 1B). As noted in Fig. 1B, transfection of testes with pCI-neo/rpS6-MT in the absence or presence of adjudin (5 vs. 50 mg/kg body wt) (but not adjudin at 5 mg/kg body wt alone) using Polyplus in vivo-jetPEI (Polyplus-transfection) as a transfection medium at ∼60% transfection efficiency, as reported earlier (8), was found to induce an upregulation on the steady-state protein level of p-rpS6-S235/S236 and p-rpS6-S240/S244 (Fig. 1B). For the total rpS6, overexpression of p-rpS6-MT also increased its steady-state protein level, but not adjudin alone at either 5 or 50 mg/kg body wt (Fig. 1B and Supplemental Fig. S1; Supplemental Material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8059868.v1). As expected, adjudin at 5 mg/kg body wt alone had no effects on the status of spermatogenesis (Fig. 1C). Overexpression of pCI-neo/rpS6-MT per se was found to induce some defects in spermatogenesis, but not as effective as adjudin at 50 mg/kg body wt (Fig. 1C). However, overexpression of p-rpS6-MT in the presence of adjudin at 5 mg/kg body wt was more effective than adjudin at 50 mg/kg body wt or p-rpS6-MT alone to perturb spermatogenesis since virtually all tubules were devoid of any germ cells by day 14 (Fig. 1C), suggesting that this might be the result of an additive effect. Defects in the status of spermatogenesis, including by pCI-neo/rpS6-MT with or without adjudin at 5 mg/kg body wt are 1) loss of germ cells, most notably elongating/elongated spermatids, round spermatids and spermatocytes; 2) appearance of multinucleated round spermatids (and also some multi-nucleated spermatocytes), which were subsequently degraded by Sertoli cells through phagocytosis; 3) defects in spermatid polarity in which spermatid heads no longer pointed to the basement membrane but deviated by 90–180° from the intended orientation; 4) defects in elongated spermatid transport in which groups of spermatids with polarity defects were found to be trapped deep inside the epithelium near the base of the tubule; and 5) defects in phagosome transport (Fig. 1C). Also noted were thinning of the seminiferous epithelium due to germ cell exfoliation, as noted in in Fig. 1C, column 2 (see color-boxed areas across different treatment versus control groups). Data from histological analysis were summarized and shown on the bar graphs in Fig. 1D. It is noted that there were no obvious differences between the three treatment groups, namely high-dose adjudin versus p-rpS6-MT and adjudin (low dose) + p-rpS6-MT overexpression regarding defects in the seminiferous epithelium following treatment (Fig. 1D, top), since the severity of defects could not be distinguished among the three treatment groups (see Fig. 1D, top bar graph). However, careful analysis of the data in Fig. 1C show otherwise. For instance, there was considerable seminiferous epithelial thinning in the p-rpS6-MT plus adjudin low-dose group in the second column of Fig. 1C in randomly selected tubules. These data were shown in Fig. 1D, bottom bar graph. The disruptive effects of p-rpS6-MT were mediated likely by its ability to induce BTB disruption by making the barrier “leaky,” as noted in Fig. 2A, since a “leaky” BTB potentiated the ability of adjudin to penetrate the barrier to reach the adluminal compartment to induce germ cell exfoliation, as noted in Fig. 1C. Data shown in Fig. 2B also summarized findings in Fig. 2A.

Fig. 2.

A study to assess changes in blood-testis barrier (BTB) integrity following overexpression of p-rpS6-MT with or without adjudin cotreatment. A: BTB integrity was assessed, in which an intact BTB near the base of the seminiferous tubule (basement membrane annotated by the white dashed line) was capable of blocking the diffusion of a membrane-impermeable small biotinylation reagent (EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin, Mr 556.59), as noted in control (pCI-neo/Ctrl) and also when adjudin was used at a low dose (5 mg/kg body wt), which earlier was shown to have no effects on the status of spermatogenesis and BTB function (11, 15). Also, at 50 mg/kg body wt, adjudin had no effects on the BTB integrity in vivo by 2 wk, consistent with earlier reports (51, 55). However, treatment of rats with CdCl2 (3 mg/kg body wt, 3 days) induced irreversible BTB disruption, wherein biotin had leaked into the tubule lumen. Yet overexpression of phosphorylated (activated) ribosomal protein S6-mutant (p-rpS6-MT) was capable of making the BTB “leaky,” thereby facilitating the entry of adjudin (at 5 mg/kg body wt) into the adluminal compartment and to induce germ cell exfoliation. Furthermore, overexpression of p-rpS6-MT alone was also capable of inducing germ cell loss from the testis, possibly as a result of BTB disruption. Results are representative findings of an experiment that was repeated with n = 3 rats and yielded similar results. Scale bars, 400 (inset, low magnification) and 70 µm, which applies to corresponding micrographs. B: semiquantitative analysis of the data shown in A by assessing %tubules that had defects in BTB integrity by comparing the diffusion of the biotin (Dbiotin) into the seminiferous epithelium vs. the seminiferous tubule radius (STradius) (see materials and methods for details). *P < 0.01 by ANOVA.

Overexpression of p-rpS6-MT perturbs seminiferous epithelial cytoskeletal organization.

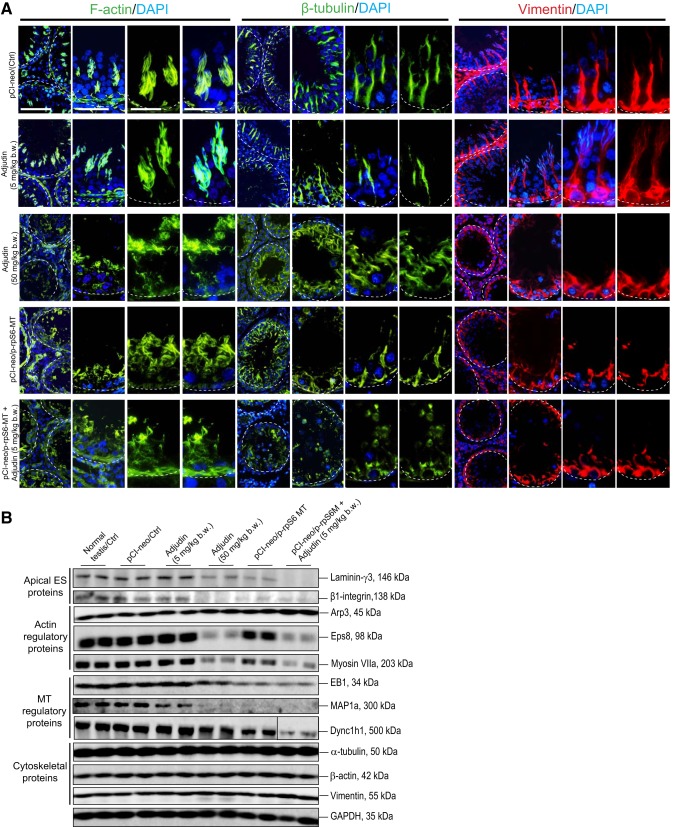

When adjudin was used at a low dose at 5 mg/kg body wt, it had no apparent effects on the cytoskeletal organization of F-actin, MTs [visualized by β-tubulin staining since α-/β-tubulin dimers are the building blocks of MTs (59, 70)], or vimentin-based intermediate filaments, similar to control testes (Fig. 3A). For instance, F-actin, vimentin, and most notably MTs appeared as track-like structures, and they lay perpendicular against the basement membrane (Fig. 3A). These tracks worked in concert with motor proteins, such as dynein 1 [an MT-specific minus (–)-end directed cargo protein (77)], and were used to support the transport of developing germ cells in particular elongating/elongated spermatids and other organelles (e.g., residual bodies, phagosomes) across the seminiferous epithelium during the epithelial cycle of spermatogenesis. However, overexpression of p-rpS6-MT in the testis would potentiate the effects of adjudin at 5 mg/kg body wt, since track-like structures across the epithelium conferred by one of the three cytoskeletons were no longer visible (Fig. 3A). Data shown in Fig. 3B and Supplemental Figure S2 also summarized changes in the expression of selected actin- and MT-based regulatory proteins following rats treated with adjudin at high doses. However, combined use of adjudin at low doses plus overexpression of p-rpS6-MT was capable of perturbing the expression of these regulatory proteins, which might be the basis for changes in cytoskeletal organization across the seminiferous epithelium. This possibility was examined in the next few experiments.

Fig. 3.

Changes in the organization of actin-, microtubule (MT)-, and vimentin-based cytoskeletons in testes following overexpression of phosphorylated (activated) ribosomal protein S6-mutant (p-rpS6-MT) with or without adjudin treatment. A: control testes (transfected with pCI-neo empty vector, pCI-neo/Ctrl) and also testes from rats treated with adjudin at low doses alone: 1) F-actin in these stage V tubules was found to wrap around elongating spermatids conspicuously to support spermatid adhesion and transport; 2) MTs (visualized by β-tubulin staining which, together with α-tubulin, i.e., α-/β-tubulin dimers, served as the building blocks of MTs) appeared as track-like structures that lay perpendicular to the basement membrane (annotated by white dashed line) that stretched across the entire epithelium to support spermatid and organelle transport; and 3) vimentin-based intermediate filaments also stretched across the epithelium that lay perpendicular to the basement membrane to support cellular transport. Adjuidin at a high dose (50 mg/kg body wt) considerably perturbed the organization of these cytoskeletons, and they were truncated and no longer aligned orderly across the epithelium as noted in control, similar to testes overexpressed with p-rpS6-MT alone. Combined overexpression of p-rpS6-MT and low-dose adjudin caused considerable more damage to the organization of these cytoskeletons, consistent with findings noted in Fig. 1C. Results shown are representative findings of an experiment that was repeated with n = 3 rats and yielded similar results. Scale bars: 180, 100, 80, and 80 µm in the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th columns, respectively, which applies to images in corresponding columns. B: immunoblot analysis that illustrates adjudin at a high dose (50 mg/kg body wt) and the combined use of adjudin at a low dose and overexpression of p-rpS6-MT, but not adjudin at a low dose alone, perturbed the expression of actin- and MT-regulatory proteins. Changes in the distribution of these proteins were examined in subsequent experiments. Results shown are representative findings of an experiment from n = 3 independent experiments, which yielded similar results.

Overexpression of p-rpS6-MT potentiates disruptive changes on the spatial expression of actin regulatory proteins that impedes F-actin organization in the testis.

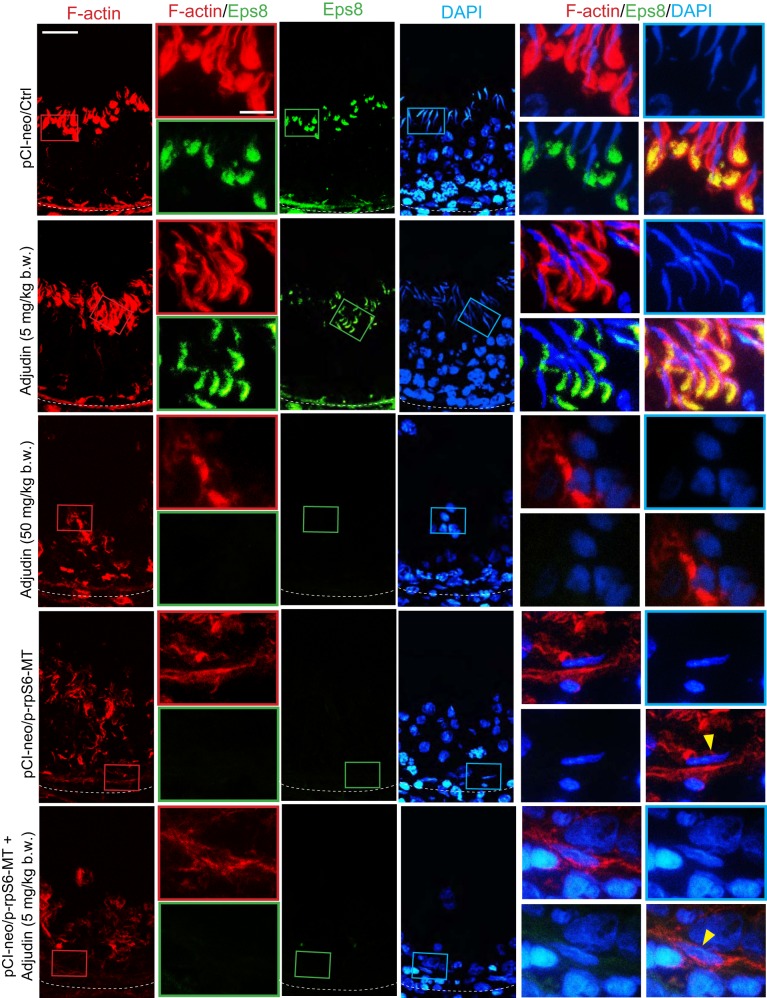

In control testes, similar to testes from rats treated with adjudin at low doses (5 mg/kg body wt), F-actin appeared as bulb-like structures at the concave side of spermatid heads at the apical ES in the seminiferous epithelium, being supported by the conspicuous expression of Eps8 (an actin barbed-end capping and bundling protein that supports actin filament bundles at the ES) (Fig. 4). This phenotype was shared by Arp3 (an actin barbed-end nucleation protein that supports branched actin polymerization at the ES; Fig. 5). These prominent expressions of Eps8 and Arp3 at the apical ES thus conferred apical ES the ability to support endocytic vesicle-mediated protein trafficking, facilitating the assembly of “new” apical ES through protein endocytosis and recycling when step 8 spermatids arose concomitant with apical ES degeneration at stage VIII of the epithelial cycle (Figs. 4 and 5) in normal testes. Overexpression of p-rpS6-MT alone was capable of perturbing these spatial expression of Eps8 (Fig. 4) and Arp3 (Fig. 5); however, p-rpS6-MT potentiated the disruptive effects of adjudin at 5 mg/kg body wt, making the testis indistinguishable from the testis in rats treated with adjudin at 50 mg/kg body wt (Figs. 4 and 5).

Fig. 4.

Changes in the organization of actin-based cytoskeleton in testes following overexpression of phosphorylated (activated) ribosomal protein S6-mutant (p-rpS6-MT) with or without adjudin treatment vs. controls are mediated by changes in the spatial expression of Eps8. Changes in the distribution of epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8 (Eps8), an actin barbed-end capping and bundling protein known to maintain the actin filaments to be assembled as bundles at the ectoplasmic specialization (44), were examined herein. In stage VII or early VIII tubules from testes of the control and the low-dose adjudin groups, Eps8 appeared as bulb-like structures, prominently expressed at the concave (ventral) side of spermatid heads and colocalized with F-actin. Following adjudin treatment at a high dose or overexpression with p-rpS6-MT with or without adjudin at a low dose, Eps8 was no longer expressed in any tubules, as noted in testes of the control or low-dose adjudin group. Instead, Eps8 was considerably diminished and virtually undetectable, and the organization F-actin was also grossly disrupted, as noted in Fig. 3A. For some elongated spermatids that were found in the treatment groups, they had defects in polarity (annotated by yellow arrowheads) in which their heads no longer pointed to the basement membrane but deviated by 90–180° from the intended orientation. Results shown are representative findings of an experiment that was repeated with n = 3 rats and yielded similar results. Scale bars: 80 and 40 µm, which applies to corresponding micrographs.

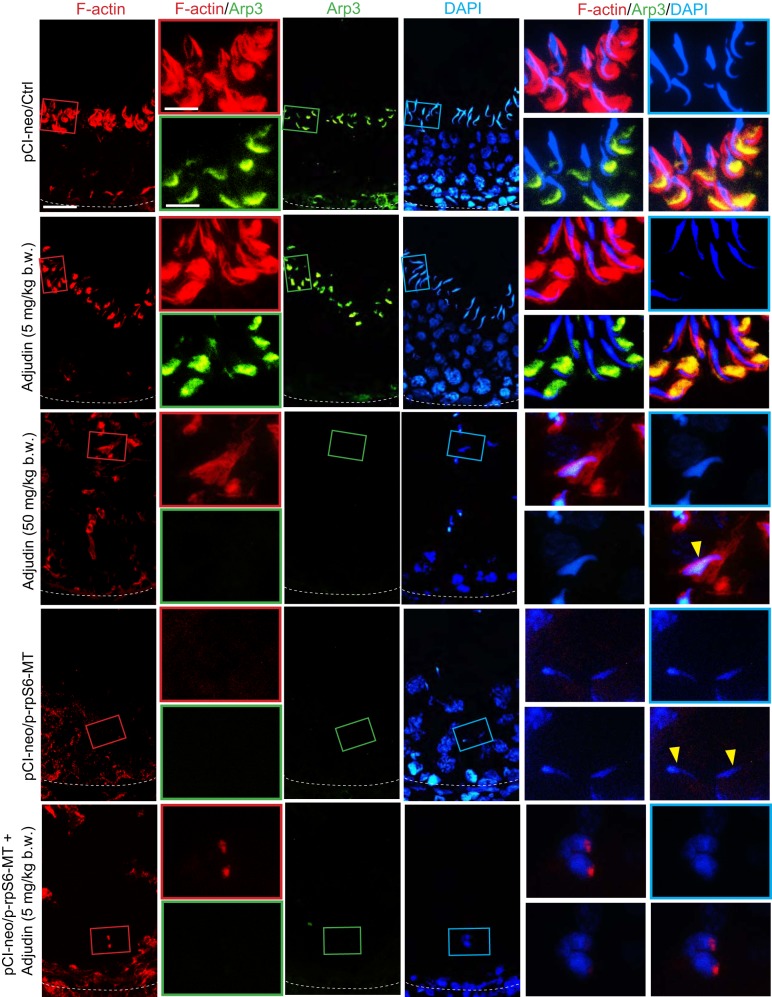

Fig. 5.

Changes in the organization of actin-based cytoskeleton in testes following overexpression of phosphorylated (activated) ribosomal protein S6-mutant (p-rpS6-MT) with or without adjudin treatment vs. controls are mediated by changes in the spatial expression of actin-related protein 3 (Arp3). Changes in the distribution of Arp3, an actin barbed-end nucleation protein that converts linear actin filaments to a branched network (43), which together with epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8 (Eps8) thus conferred plasticity to F-actin at the ectoplasmic specialization to support spermatogenesis to facilitate the transport of spermatids and organelles (e.g., residual bodies, phagosomes) across the seminiferous epithelium. In stage VII or early stage VIII tubules from testes of the control and the low-dose adjudin groups, Arp3 appeared as bulb-like structures, prominently expressed at the concave (ventral) side of spermatid heads and colocalized with F-actin. Following adjudin treatment at a high dose or overexpression with p-rpS6-MT with or without adjudin at low dose, Arp3 was no longer expressed in any tubules, as noted in testes of the control or low-dose adjudin group. Instead, Arp3 was considerably diminished and virtually undetectable, and the organization F-actin was also grossly disrupted as noted in Fig. 3A. For some elongated spermatids that were found in the treatment groups, they had defects in polarity (annotated by yellow arrowheads) in which their heads no longer pointed to the basement membrane but deviated by 90–180° from the intended orientation. Results shown are representative findings of an experiment that was repeated with n = 3 rats and yielded similar results. Scale bars: 80 and 40 µm, which applies to corresponding micrographs in the same panel.

Overexpression of p-rpS6-MT potentiates disruptive spatial expression of apical ES- adhesion proteins that impede spermatid adhesion, leading to spermatid exfoliation.

In control testes and testes from rats treated with adjudin at low doses (5 mg/kg body wt), which had no apparent effects on the status of spermatogenesis (Fig. 1C), laminin-γ3 chain, an apical ES protein specifically expressed by elongated spermatids (34, 82), was localized prominently at the tip of spermatid heads (Supplemental Fig. S3). On the other hand, nectin 2 [a Sertoli cell-specific apical ES protein (60); Supplemental Fig. S4] and β1-integrin (Supplemental Fig. S5) were localized at the convex side of spermatid heads in testes of control and low-dose adjudin-treated (5 mg/kg body wt) rats. However, overexpression of p-rpS6-MT in testes potentiated the disruptive effects of adjudin at 5 mg/kg body wt, causing considerable downregulation and mislocalization of either laminin-γ3 chain (Supplemental Fig. S3), nectin 2 (Supplemental Fig. S4), or β1-integrin (Supplemental Fig. S5). This is likely due to an increase in the permeability of adjudin at the BTB, potentiating the effects of adjudin, making it similar to rats exposed to adjudin at 50 mg/kg body wt even though only one-tenth of adjudin was used. This possibility was also supported by data shown in Fig. 2.

Overexpression of p-rpS6-MT potentiates adjudin-mediated germ cell exfoliation in the seminiferous epithelium by enhancing adjudin transport at the BTB.

In control testes and testes from rats treated with adjudin at low doses (5 mg/kg body wt), TJ proteins occludin and ZO-1 (Fig. 6) and basal ES proteins N-cadherin and β-catenin (Supplemental Fig.S6) localized tightly to the BTB site, which was localized adjacent to the basement membrane. However, overexpression of p-rpS6-MT potentiates the disruptive effects of adjudin at low doses (5 mg/kg body wt), making the distribution of TJ proteins (Fig. 6) and basal ES proteins (Supplemental Fig. S6) considerably worse than testes from rats treated with either adjudin at high doses (50 mg/kg body wt) or p-rpS6-MT overexpression alone.

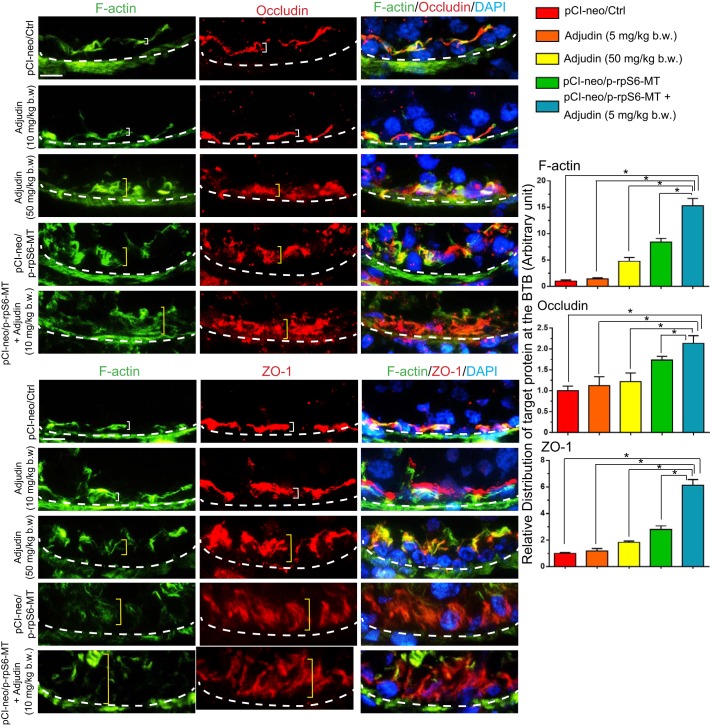

Fig. 6.

Changes in the distribution of tight junction (TJ) adhesion proteins occludin-ZO-1 at the blood-testis barrier (BTB) in testes following overexpression of phosphorylated (activated) ribosomal protein S6-mutant (p-rpS6-MT) with or without adjudin treatment vs. controls. In testes of rats from the control group or low-dose adjudin (5 mg/kg body wt) treated group, TJ proteins occludin or zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) were colocalized with F-actin and tightly distributed at the BTB (see white brackets) located near the basement membrane (annotated by white dashed line). Following adjudin treatment at a high dose (50 mg/kg body wt) or overexpression with p-rpS6-MT with or without adjudin at a low dose, either occludin or ZO-1 was no longer tightly distributed at the BTB but diffusively distributed (see yellow brackets), possibly due to the disorganization of F-action at the site since occludin and ZO-1 both utilize actin for attachments. Histograms shown on the right are composite data of the immunofluorescence analysis shown on the left. Each bar is a mean ± SD of n = 4 rats, and for each test, ≥80 randomly selected cross-sections of tubules were quantified so that a total of 320 seminiferous tubules were scored. Results shown are representative findings of an experiment that was repeated with n = 3 rats and yielded similar results. Scale bar: 40 µm, which applies to all other micrographs. Bar graph on the right depicts changes in the distribution of F-actin vs. TJ proteins occludin and ZO-1 at the BTB in treatment and control groups. Each bar is a mean ± SD of n = 3 rats. For each rat, ∼80 tubules were randomly scored, and changes in the distribution of target proteins were assessed. *P < 0.01 by ANOVA.

Overexpression of p-rpS6-MT potentiates adjudin-mediated germ cell exfoliation in the seminiferous epithelium by altering actin-based motor protein myosin VIIa distribution.

Because the function of MT-based tracks to support germ cell and organelle transport relies on the motor proteins, such as myosin VIIa, to facilitate cargo transport, we examined whether there were changes in myosin VIIa distribution in the testis following overexpression of p-rpS6 with and without adjudin at low dose. In testes of control and adjudin low-dose animal groups, myosin VIIa, an F-actin-based barbed (+)-end directed motor protein (36, 73, 78), was conspicuously expressed at the apical and basal ES/BTB across the epithelium and colocalized with F-actin, often at the concave side of spermatid heads (Supplemental Fig. S7). Overexpression of p-rpS6-MT potentiated the disruptive effects of low-dose adjudin, considerably diminishing the expression of myosin VIIa across the epithelium (Supplemental Fig. S7), consistent with histology data shown in Fig. 1C.

Overexpression of p-rpS6-MT potentiates disruptive changes on the spatial expression of MT regulatory proteins and motor protein dynein 1 to impede MT organization.

As noted in Fig. 3A, there were considerable disruptions on the organization of MT-based cytoskeleton following overexpression of p-rpS6-MT coupled with low-dose adjudin, worse than the use of adjudin at high-dose or p-rpS6-MT alone. We examined whether this was due to changes in the spatiotemporal expression of MT regulatory proteins EB1 [end-binding protein 1, a plus (+)-end tracking protein (+TIP)] and MAP1a (microtubule-associated protein 1A), which are known to confer MT stability when they bind to MTs (6, 56, 57, 59, 70). In testes of control and adjudin low-dose animal groups, EB1 and MAP1a were prominently expressed in the epithelium that lay across the seminiferous epithelium as track-like structures (Fig. 7), similar to MTs (Fig. 3A). Adjudin at high doses (50 mg/kg body wt) or overexpression of p-rpS6-MT perturbed the distribution and expression of EB1 and MAP1a in the epithelium considerably, eliminating virtually all these track-like structures in the epithelium (Fig. 7). On the other hand, overexpression of p-rpS6-MT in combination with adjudin at low doses was even more effective to eliminate these track-like structures conferred by EB1- and MAP-1a (Fig. 7). Consistent with these findings, distribution of dynein 1 [visualized by the use of an antibody specific to the dynein 1 heavy chain, as recently reported (77)] across the seminiferous epithelium that colocalized with MT-based tracks as noted in control testes (pCI-neo/Ctrl) and low-dose adjudin treated testes were grossly disrupted in testes from both high-dose adjudin group and overexpressed with p-rpS6-MT (Fig. 8). However, testes overexpressed with p-rpS6-MT combined with adjudin at low doses was considerably more effective to perturb the distribution of dynein 1 across the epithelium (Fig. 8).

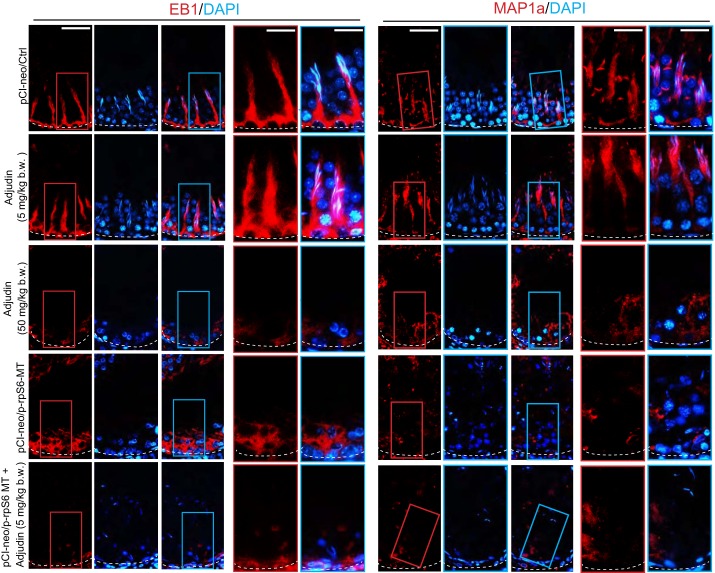

Fig. 7.

Changes in the spatial expression of microtubule (MT) regulatory proteins end-binding protein 1 (EB1) and microtubule-associated protein 1a (MAP1a), which perturb MT organization following overexpression of phosphorylated (activated) ribosomal protein S6-mutant (p-rpS6-MT) with or without adjudin treatment vs. controls. In testes of rats from the control or low-dose adjudin-treated (5 mg/kg body wt) group, EB1 (a +TIP that stabilizes MT) and MAP1a (a MT-binding protein that stabilizes MT protofilaments; however, its phosphorylation by MAPK such as microtubule affinity-regulatory kinase 4 leads to its dissociation from MT, conferring MT catastrophe) appeared as track-like structures (due to their association with MT-based tracks) that lay perpendicular to the basement membrane (annotated by white dashed line) in the seminiferous epithelium. Following treatment with adjudin at 50 mg/kg body wt or overexpression with p-rpS6-MT, the expression and distribution of EB1 or MAP1a in the seminiferous epithelium were considerably diminished, whereas in the p-rpS6-MT and low-dose adjudin groups, the expression of either EB1 or MAP1a in the seminiferous epithelium was considerably weaker than testes from either the adjudin (50 mg/kg body wt) or p-rpS6-MT group. These changes thus impeded MT organization across the seminiferous epithelium, as noted in Fig. 3A. Results shown are representative findings of an experiment that was repeated with n = 3 rats and yielded similar results. Scale bar: 80 and 50 µm in insets boxed in red or blue, which applies to corresponding micrographs and insets.

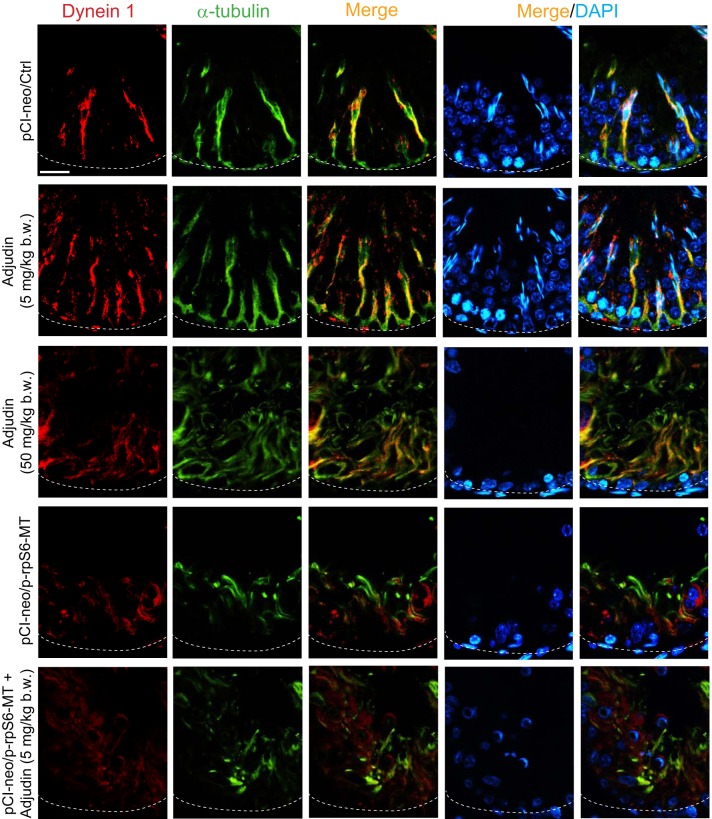

Fig. 8.

Changes in the distribution of microtubule (MT)-based motor protein dynein 1 in the seminiferous epithelium of testes following overexpression of phosphorylated (activated) ribosomal protein S6-mutant (p-rpS6-MT)with or without adjudin treatment vs. controls. In testes of rats from control or low-dose adjudin-treated (5 mg/kg body wt) group, MT-based motor protein dynein 1 (red fluorescence) visualized by using a specific anti-dynein 1 heavy chain (anti-Dync1h1) (77) was found to be localized along the MT-based tracks, consistent with its function as a minus (−) end-directed motor protein. In fact, dynein 1 was colocalized with MTs (stained by α-tubulin, which together with β-tubulin create the α-/β-tubulin dimers, which are the building blocks of MTs) across the entire seminiferous epithelium, serving as the engine to transport cargoes (e.g., elongating spermatids) across the epithelium. However, treatment of rats with adjudin at a high dose (50 mg/kg body wt, via oral gavage) or overexpression of pCI-neo/p-rpS6-MT considerably disrupted the distribution of dynein 1 and the organization of MT-based tracks as noted herein. But overexpression of pCI-neo/p-rpS6-MT combined with the use of adjudin at a low dose (5 mg/kg body wt), which by itself had no effects, was found to induce more remarkable disruption of dynein 1 organization and MT organization. The basement membrane at the base of the seminiferous tubule was annotated by a dashed white line. Results are representative findings of an experiment that was repeated with n = 3 rats and yielded similar results. Scale bar: 40 µm, which applies to all other micrographs.

DISCUSSION

In the mammalian testis, the BTB supports spermatogenesis since the assembly of a functional barrier at ∼16–18 days postpartum in rats coincides with the onset of meiosis (4, 52, 63). This is also consistent with findings in humans that the appearance of a functional BTB at puberty at ∼12–13 yr of age coincides with the production of spermatozoa (3, 10, 21). Also, treatment of neonatal rats with diethylstilbestrol (a synthetic nonsteroidal estrogen), which retards BTB development, also delays meiosis, wherein pachytene spermatocytes undergo degeneration (72). Furthermore, the use of a goitrogen (e.g., 6-propyl-2-thiouracil) to induce neonatal hypothyroidism in rats, which delays Sertoli cell differentiation by impeding BTB assembly, also perturbs spermatogenic function (18, 20, 30). Interestingly, although the BTB is one of the tightest blood-tissue barriers, it undergoes rapid remodeling during the epithelial cycle of spermatogenesis to facilitate the transport of preleptotene spermatocytes across the barrier (29, 67). Studies have shown that this is a series of highly orchestrated cellular events (67) involving delicate control of endocytosis and recycling (83–85) of TJ and basal ES proteins (67), including specialized ultrastructures known as the basal tubulobulbar complex (74, 76) and a local regulatory axis (13, 14). For instance, studies have shown that endogenously produced signaling proteins such as mTORC1/rpS6 are upregulated to induce BTB remodeling (48, 50, 53). It was first demonstrated that a downregulation of rpS6 by RNAi promoted Sertoli cell TJ-barrier function (53), implicating that an activation of rpS6 through an upregulation of p-rpS6-S235/S236 and -S240/S244 would lead to BTB remodeling (53). This notion was supported by two lines of evidence. First, treatment of rats with a high dose of adjudin, such as at 250 mg/kg body wt, which induced irreversible BTB damage, leading to infertility in adult rats (51), was associated with a considerable surge in the expression of p-rpS6-S235/S236 and -S240/S244 by as much as 12-fold (vs. control rat testes), although the steady-state protein level of total rpS6 was unaffected and the mTOR level was considerably downregulated (53). Second, overexpression of rpS6-WT and p-rpS6-MT in Sertoli cells cultured in vitro perturbed the Sertoli cell TJ-barrier through changes in the organization of actin-based cytoskeleton (48, 50). More importantly, these disruptive effects of p-rpS6-MT on the Sertoli cell TJ-barrier function vitro were reproduced in vivo by transfecting testes with p-rpS6-MT versus rpS6-WT plasmid DNA (41). These findings that mTORC1/rpS6 may be involved in BTB dynamics through changes in cytoskeletal organization have recently been confirmed in studies using different genetic models. For instance, specific deletion of mTOR in Sertoli cells in mice led to a surge in p-rpS6-S240/S244 expression and seminiferous epithelial degeneration, causing male infertility (7), mimicking findings in vivo using the adjudin and the rpS6-specific siRNA knockout models (53). On the other hand, specific deletion of Raptor (i.e., inactivation of mTORC1) in Sertoli cells in mice caused extensive tubular degeneration due to disruptive organization of actin-, MT-, and vimentin-based cytoskeletons (81), also mimicking the p-rpS6-MT overexpression model (41). Collectively, these data suggest that the use of p-rpS6-MT that modifies the BTB permeability function could enhance the transport function at the BTB. This possibility has now been demonstrated unequivocally by using adjudin as a candidate drug to assess changes in transport function at the BTB. These findings also support the notion that the p-rpS6-MT may possibly induce remodeling/opening of other blood-tissue barriers such that therapeutic drugs can be effectively delivered to a target organ.

We have presented compelling evidence in this report illustrating that adjudin when used at 5 mg/kg body wt (via oral gavage) alone, it was ineffective at inducing any notable phenotype in the testis, consistent with earlier findings (15). Its administration, coupled with overexpression of p-rpS6-MT using the regimen reported herein, however, was exceedingly effective to induce germ cell exfoliation, which was considerably better than using either adjudin at 50 mg/kg body wt or p-rpS6-MT alone. In short, overexpression of p-rpS6-MT renders an increase in adjudin potency by as much as 10-fold by modifying the transport function of the BTB. Furthermore, it was unequivocally demonstrated that the combined use of adjudin and p-rpS6-MT that induced germ cell exfoliation was mediated by changes in the spatial expression of F-actin regulatory proteins (e.g., Eps8, Arp3) or MT regulatory proteins (e.g., EB1, MAP1a), thereby impeding the organization of actin-, MT-, and vimentin-based cytoskeletons. These changes thus perturb the function of adhesion proteins at the apical ES (e.g., laminin-γ3, nectin 2, β1-integrin) and at the basal ES (e.g., occludin-ZO-1, N-cadherin-β-catenin), promoting germ cell depletion from the seminiferous epithelium since these proteins all utilize F-actin for attachments and support by MTs (58, 59). Additionally, disruptive changes in the actin- and MT-based cytoskeletons also perturb the BTB integrity in the testis in vivo. Another notable observation is the considerable change in the distribution of actin- and MT-specific motor proteins, namely myosin VIIa and dynein 1, respectively, which were noted following overexpression of p-rpS6-MT coupled with low-dose adjudin. Because these motor proteins are known to confer cargo transport, including spermatids, phagosomes, residual bodies, mitochondria, and others, across the seminiferous epithelium to support spermatogenesis (61, 71, 73, 77, 78), their disorganization thus renders the inability of the elongated spermatids to be transported to the luminal edge of the epithelium to undergo spermiation. As such, many step 19 spermatids were entrapped deep inside the epithelium, some of which were located near the basement membrane, failing to be emptied into the tubule lumen.

These findings are important because they demonstrate that this approach can be used to enhance the ability of a drug to penetrate a blood-tissue barrier if it exerts its biological effects behind it. However, it remains to be determined whether p-rpS6-MT can also induce an increase in the permeability of other blood-tissue barriers, such as the BBB, for therapeutic applications. These future studies are of physiological significance since emerging evidence has shown that the testis and the brain often serve as a safe haven for viruses such as the Zika virus (26, 62) and HIV (19, 37). Thus, this approach can possibly be explored to deliver anti-viral drugs behind the BTB and the BBB to eradicate viruses harbored in the testis and brain, respectively. Furthermore, this approach can also be explored to administer pCI-neo/p-rpS6-MT plasmid DNA (or p-rpS6-MT recombinant protein) based on the use of nanoparticles, as illustrated for delivering adjudin or other therapeutic drugs (including cDNA and RNA) to mammalian cells, tissues, and/or organs (1, 9, 16, 35, 42, 86), but through the use of nasal spray for delivery as described (2, 9, 46, 64). In summary, we have provided insightful information regarding the likely mechanism by which the mTORC1/rpS6 signaling complex modulates BTB function through changes in the actin- and MT-based cytoskeletons, which involves multiple regulatory and supporting proteins as well as motor proteins.

GRANTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01-HD-056034 and U54 HD-029990 to C. Y. Cheng), and The National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, 81601264 to L.L., 81730042 to R.G.). M.Y. was supported by a fellowship from the China Scholarship Council (201607060039); L.L., B.M. and H.L. were supported by a fellowship from Wenzhou Medical University. M. Yan was supported by a fellowship from the China Scholarship Council.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.Y.C. conceived and designed research; M.Y., L.L., B.M., H.L., S.Y.L., and C.Y.C. performed experiments; M.Y., L.L., B.M., H.L., S.Y.L., and C.Y.C. analyzed data; D.M., B.S., Q.L., R.G., and C.Y.C. interpreted results of experiments; M.Y. and C.Y.C. prepared figures; C.Y.C. drafted manuscript; C.Y.C. edited and revised manuscript; M.Y., L.L., B.M., H.L., S.Y.L., D.M., B.S., Q.L., R.G., and C.Y.C. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Current address of M. Yan: Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Drug Screening, Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Druggability of Biopharmaceuticals, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing, China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agrahari V, Burnouf P-A, Burnouf T, Agrahari V. Nanoformulation properties, characterization, and behavior in complex biological matrices: Challenges and opportunities for brain-targeted drug delivery applications and enhanced translational potential. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. In press. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2019.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alpar HO, Somavarapu S, Atuah KN, Bramwell VW. Biodegradable mucoadhesive particulates for nasal and pulmonary antigen and DNA delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 57: 411–430, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amann RP. The cycle of the seminiferous epithelium in humans: a need to revisit? J Androl 29: 469–487, 2008. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.107.004655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergmann M, Dierichs R. Postnatal formation of the blood-testis barrier in the rat with special reference to the initiation of meiosis. Anat Embryol (Berl) 168: 269–275, 1983. doi: 10.1007/BF00315821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bockaert J, Marin P. mTOR in brain physiology and pathologies. Physiol Rev 95: 1157–1187, 2015. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00038.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowne-Anderson H, Hibbel A, Howard J. Regulation of microtubule growth and catastrophe: Unifying theory and experiment. Trends Cell Biol 25: 769–779, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyer A, Girard M, Thimmanahalli DS, Levasseur A, Céleste C, Paquet M, Duggavathi R, Boerboom D. mTOR regulates gap junction alpha-1 protein trafficking in Sertoli cells and is required for the maintenance of spermatogenesis in mice. Biol Reprod 95: 13, 2016. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.115.138016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen H, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Regulation of spermatogenesis by a local functional axis in the testis: role of the basement membrane-derived noncollagenous 1 domain peptide. FASEB J 31: 3587–3607, 2017. doi: 10.1096/fj.201700052R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen H, Mruk DD, Xia W, Bonanomi M, Silvestrini B, Cheng CY. Effective delivery of male contraceptives behind the blood-testis barrier (BTB)—lesson from adjudin. Curr Med Chem 23: 701–713, 2016. doi: 10.2174/0929867323666160112122724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen H, Mruk DD, Xiao X, Cheng CY. Human spermatogenesis and its regulation. In: Male Hypogonadism, Contemporary Endocrinology, edited by Winters SJ, Huhtaniemi IT. . New York: Springer International Publishing, p. 49–72, 2017. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-53298-1_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng CY. Toxicants target cell junctions in the testis: Insights from the indazole-carboxylic acid model. Spermatogenesis 4: e981485, 2015. doi: 10.4161/21565562.2014.981485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng CY, Mruk DD. The blood-testis barrier and its implications for male contraception. Pharmacol Rev 64: 16–64, 2012. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.002790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng CY, Mruk DD. An intracellular trafficking pathway in the seminiferous epithelium regulating spermatogenesis: a biochemical and molecular perspective. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 44: 245–263, 2009. doi: 10.1080/10409230903061207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng CY, Mruk DD. A local autocrine axis in the testes that regulates spermatogenesis. Nat Rev Endocrinol 6: 380–395, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng CY, Mruk D, Silvestrini B, Bonanomi M, Wong CH, Siu MKY, Lee NPY, Lui WY, Mo MY. AF-2364 [1-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)-1H-indazole-3-carbohydrazide] is a potential male contraceptive: a review of recent data. Contraception 72: 251–261, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng J, Nonaka T, Wong DTW. Salivary Exosomes as Nanocarriers for Cancer Biomarker Delivery. Materials (Basel) 12: 654, 2019. doi: 10.3390/ma12040654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clermont Y, Morales C, Hermo L. Endocytic activities of Sertoli cells in the rat. Ann N Y Acad Sci 513: 1–15, 1987. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb24994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooke PS, Porcelli J, Hess RA. Induction of increased testis growth and sperm production in adult rats by neonatal administration of the goitrogen propylthiouracil (PTU): the critical period. Biol Reprod 46: 146–154, 1992. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod46.1.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darcis G, Coombs RW, Van Lint C. Exploring the anatomical HIV reservoirs: role of the testicular tissue. AIDS 30: 2891–2893, 2016. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Franca LR, Hess RA, Cooke PS, Russell LD. Neonatal hypothyroidism causes delayed Sertoli cell maturation in rats treated with propylthiouracil: evidence that the Sertoli cell controls testis growth. Anat Rec 242: 57–69, 1995. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092420108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Kretser DM, Kerr JB. The cytology of the testis. In: The Physiology of Reproduction, edited by Knobil E, Neill JB, Ewing LL, Greenwald GS, Markert CL, Pfaff DW. New York: Raven, 1988, vol 1, p. 837–932. [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Rooij DG. The spermatogonial stem cell niche. Microsc Res Tech 72: 580–585, 2009. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dong H, Chen Z, Wang C, Xiong Z, Zhao W, Jia C, Lin J, Lin Y, Yuan W, Zhao AZ, Bai X. Rictor regulates spermatogenesis by controlling Sertoli cell cytoskeletal organization and cell polarity in the mouse testis. Endocrinology 156: 4244–4256, 2015. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.França LR, Auharek SA, Hess RA, Dufour JM, Hinton BT. Blood-tissue barriers: morphofunctional and immunological aspects of the blood-testis and blood-epididymal barriers. Adv Exp Med Biol 763: 237–259, 2013. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-4711-5_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao Y, Mruk DD, Lui WY, Lee WM, Cheng CY. F5-peptide induces aspermatogenesis by disrupting organization of actin- and microtubule-based cytoskeletons in the testis. Oncotarget 7: 64203–64220, 2016. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Govero J, Esakky P, Scheaffer SM, Fernandez E, Drury A, Platt DJ, Gorman MJ, Richner JM, Caine EA, Salazar V, Moley KH, Diamond MS. Zika virus infection damages the testes in mice. Nature 540: 438–442, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nature20556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hermo L, Pelletier RM, Cyr DG, Smith CE. Surfing the wave, cycle, life history, and genes/proteins expressed by testicular germ cells. Part 1: background to spermatogenesis, spermatogonia, and spermatocytes. Microsc Res Tech 73: 241–278, 2010. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hermo L, Pelletier RM, Cyr DG, Smith CE. Surfing the wave, cycle, life history, and genes/proteins expressed by testicular germ cells. Part 2: changes in spermatid organelles associated with development of spermatozoa. Microsc Res Tech 73: 279–319, 2010. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hermo L, Pelletier RM, Cyr DG, Smith CE. Surfing the wave, cycle, life history, and genes/proteins expressed by testicular germ cells. Part 5: intercellular junctions and contacts between germs cells and Sertoli cells and their regulatory interactions, testicular cholesterol, and genes/proteins associated with more than one germ cell generation. Microsc Res Tech 73: 409–494, 2010. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hess RA, Cooke PS, Bunick D, Kirby JD. Adult testicular enlargement induced by neonatal hypothyroidism is accompanied by increased Sertoli and germ cell numbers. Endocrinology 132: 2607–2613, 1993. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.6.8504761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hess RA, Renato de Franca L. Spermatogenesis and cycle of the seminiferous epithelium. Adv Exp Med Biol 636: 1–15, 2008. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09597-4_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hew KW, Heath GL, Jiwa AH, Welsh MJ. Cadmium in vivo causes disruption of tight junction-associated microfilaments in rat Sertoli cells. Biol Reprod 49: 840–849, 1993. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod49.4.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koch M, Olson PF, Albus A, Jin W, Hunter DD, Brunken WJ, Burgeson RE, Champliaud MF. Characterization and expression of the laminin γ3 chain: a novel, non-basement membrane-associated, laminin chain. J Cell Biol 145: 605–618, 1999. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.3.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kowalski PS, Rudra A, Miao L, Anderson DG. Delivering the messenger: advances in technologies for therapeutic mRNA delivery. Mol Ther 27: 710–728, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Küssel-Andermann P, El-Amraoui A, Safieddine S, Hardelin JP, Nouaille S, Camonis J, Petit C. Unconventional myosin VIIA is a novel A-kinase-anchoring protein. J Biol Chem 275: 29654–29659, 2000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004393200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamers SL, Rose R, Maidji E, Agsalda-Garcia M, Nolan DJ, Fogel GB, Salemi M, Garcia DL, Bracci P, Yong W, Commins D, Said J, Khanlou N, Hinkin CH, Sueiras MV, Mathisen G, Donovan S, Shiramizu B, Stoddart CA, McGrath MS, Singer EJ. HIV DNA is frequently present within pathologic tissues evaluated at autopsy from combined antiretroviral therapy-treated patients with undetectable viral loads. J Virol 90: 8968–8983, 2016. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00674-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 149: 274–293, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Latendresse JR, Warbrittion AR, Jonassen H, Creasy DM. Fixation of testes and eyes using a modified Davidson’s fluid: comparison with Bouin’s fluid and conventional Davidson’s fluid. Toxicol Pathol 30: 524–533, 2002. doi: 10.1080/01926230290105721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li N, Mruk DD, Mok KW, Li MW, Wong CK, Lee WM, Han D, Silvestrini B, Cheng CY. Connexin 43 reboots meiosis and reseals blood-testis barrier following toxicant-mediated aspermatogenesis and barrier disruption. FASEB J 30: 1436–1452, 2016. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-276527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li SYT, Yan M, Chen H, Jesus T, Lee WM, Xiao X, Cheng CY. mTORC1/rpS6 regulates blood-testis barrier dynamics and spermatogenetic function in the testis in vivo. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 314: E174–E190, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00263.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li X, Gao C, Wu Y, Cheng CY, Xia W, Zhang Z. Combination delivery of Adjudin and Doxorubicin via integrating drug conjugation and nanocarrier approaches for the treatment of drug-resistant cancer cells. J Mater Chem B Mater Biol Med 3: 1556–1564, 2015. doi: 10.1039/C4TB01764A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lie PPY, Chan AYN, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Restricted Arp3 expression in the testis prevents blood-testis barrier disruption during junction restructuring at spermatogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 11411–11416, 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001823107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lie PPY, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8 (Eps8) is a novel regulator of cell adhesion and the blood-testis barrier integrity in the seminiferous epithelium. FASEB J 23: 2555–2567, 2009. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-070573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Long X, Müller F, Avruch J. TOR action in mammalian cells and in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 279: 115–138, 2004. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-18930-2_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uner M, Damgalı S, Ozdemir S, Celik B. Therapeutic potential of drug delivery by means of lipid nanoparticles: reality or illusion? Curr Pharm Des 23: 6573–6591, 2017. doi: 10.2174/1381612823666171122110638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meyuhas O. Ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation: Four decades of research. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 320: 41–73, 2015. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mok KW, Chen H, Lee WM, Cheng CY. rpS6 regulates blood-testis barrier dynamics through Arp3-mediated actin microfilament organization in rat sertoli cells. An in vitro study. Endocrinology 156: 1900–1913, 2015. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mok KW, Mruk DD, Cheng CY. Regulation of blood-testis barrier (BTB) dynamics during spermatogenesis via the “Yin” and “Yang” effects of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTORC2. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 301: 291–358, 2013. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407704-1.00006-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mok KW, Mruk DD, Cheng CY. rpS6 regulates blood-testis barrier dynamics through Akt-mediated effects on MMP-9. J Cell Sci 127: 4870–4882, 2014. doi: 10.1242/jcs.152231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mok KW, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Spermatogonial stem cells alone are not sufficient to re-initiate spermatogenesis in the rat testis following adjudin-induced infertility. Int J Androl 35: 86–101, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2011.01183.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mok KW, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. A study to assess the assembly of a functional blood-testis barrier in developing rat testes. Spermatogenesis 1: 270–280, 2011. doi: 10.4161/spmg.1.3.17998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mok KW, Mruk DD, Silvestrini B, Cheng CY. rpS6 Regulates blood-testis barrier dynamics by affecting F-actin organization and protein recruitment. Endocrinology 153: 5036–5048, 2012. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mruk DD, Cheng CY. Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) for routine immunoblotting: an inexpensive alternative to commercially available kits. Spermatogenesis 1: 121–122, 2011. doi: 10.4161/spmg.1.2.16606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mruk DD, Cheng CY. Sertoli-Sertoli and Sertoli-germ cell interactions and their significance in germ cell movement in the seminiferous epithelium during spermatogenesis. Endocr Rev 25: 747–806, 2004. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nehlig A, Molina A, Rodrigues-Ferreira S, Honoré S, Nahmias C. Regulation of end-binding protein EB1 in the control of microtubule dynamics. Cell Mol Life Sci 74: 2381–2393, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2476-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nogales E, Zhang R. Visualizing microtubule structural transitions and interactions with associated proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol 37: 90–96, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.O’Donnell L. Mechanisms of spermiogenesis and spermiation and how they are disturbed. Spermatogenesis 4: e979623, 2015. doi: 10.4161/21565562.2014.979623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O’Donnell L, O’Bryan MK. Microtubules and spermatogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol 30: 45–54, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ozaki-Kuroda K, Nakanishi H, Ohta H, Tanaka H, Kurihara H, Mueller S, Irie K, Ikeda W, Sakai T, Wimmer E, Nishimune Y, Takai Y. Nectin couples cell-cell adhesion and the actin scaffold at heterotypic testicular junctions. Curr Biol 12: 1145–1150, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00922-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reck-Peterson SL, Redwine WB, Vale RD, Carter AP. The cytoplasmic dynein transport machinery and its many cargoes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19: 382–398, 2018. [Erratum in Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19: 479, 2018]. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0004-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Robinson CL, Chong ACN, Ashbrook AW, Jeng G, Jin J, Chen H, Tang EI, Martin LA, Kim RS, Kenyon RM, Do E, Luna JM, Saeed M, Zeltser L, Ralph H, Dudley VL, Goldstein M, Rice CM, Cheng CY, Seandel M, Chen S. Male germ cells support long-term propagation of Zika virus. Nat Commun 9: 2090, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04444-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]