Abstract

Extracellular vesicles released by cancer cells have recently been implicated in the differentiation of stromal cells to their activated, cancer-supporting states. Microvesicles, a subset of extracellular vesicles released from the plasma membrane of cancer cells, contain biologically active cargo, including DNA, mRNA, and miRNA, which are transferred to recipient cells and induce a phenotypic change in behavior. While it is known that microvesicles can alter recipient cell phenotype, little is known about how the physical properties of the tumor microenvironment affect fibroblast response to microvesicles. Here, we utilized cancer cell-derived microvesicles and synthetic substrates designed to mimic the stiffness of the tumor and tumor stroma to investigate the effects of microvesicles on fibroblast phenotype as a function of the mechanical properties of the microenvironment. We show that microvesicles released by highly malignant breast cancer cells cause an increase in fibroblast spreading, α-smooth muscle actin expression, proliferation, cell-generated traction force, and collagen gel compaction. Notably, our data indicate that these phenotypic changes occur only on stiff matrices mimicking the stiffness of the tumor periphery and are dependent on the cell type from which the microvesicles are shed. Overall, these results show that the effects of cancer cell-derived microvesicles on fibroblast activation are regulated by the physical properties of the microenvironment, and these data suggest that microvesicles may have a more robust effect on fibroblasts located at the tumor periphery to influence cancer progression.

Keywords: cell contractility, extracellular matrix, fibroblast activation, mechanotransduction, traction force

INTRODUCTION

The stromal microenvironment plays a crucial role in the determination of cancer cell metastatic potential. Signaling molecules, extracellular components, and cells within the stroma can increase or decrease the metastatic potential of cancer cells (39). This relationship is bidirectional as the microenvironment is often manipulated by cancer cells through both direct and indirect mechanisms. Recent studies have shown that extracellular vesicles (EVs) secreted by cancer cells, specifically exosomes and microvesicles (MVs), communicate with stromal cells to alter the local tumor microenvironment (2, 46, 49, 54). MVs originate from the plasma membrane of cells and range from 200 nm to 1 μm in diameter (40). They contain a wide variety of cargo, including extracellular matrix (ECM) components, cytoskeletal proteins, and signaling molecules (1, 2, 4). The interaction of cancer cell-derived MVs with recipient cells promotes cancer-supporting characteristics, including increased cell growth and survival (2, 5). The effects of MV components within the tumor microenvironment are just beginning to be uncovered.

Cancer cell invasion through the basement membrane and metastasis to a secondary site are highly dependent upon cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions (44). Specifically, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) located in the tumor microenvironment have been shown to mediate cancer cell invasion and metastasis through the direct remodeling of the ECM (14, 33, 38). CAFs use contractile forces to generate tracks in the ECM to guide cancer cell invasion and promote metastasis (38). It is currently hypothesized that a large portion of CAFs in the tumor microenvironment are derived from fibroblasts adjacent to the primary tumor that have been transformed to an activated state (22). It was recently established that MVs released from MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells transform normal fibroblasts to exhibit increased survival capability and the ability to grow under low-serum conditions (2). Proteomic screens of MDA-MB-231 MVs were carried out to determine the MV-associated proteins responsible for fibroblast transformation, specifically tissue transglutaminase and fibronectin (2).

Fibroblasts in the tumor stroma are exposed to both compliant healthy tissue and the increasingly stiff tissue of the primary tumor. Specifically, increased matrix stiffness has been shown to promote fibroblast spreading, traction force, and proliferation (13, 29). Here, we examined the effects of breast cancer cell-derived MVs on fibroblast function on substrates mimicking both healthy and tumorigenic tissue. We show that MVs increase fibroblast cell area, contractility, and proliferation in a manner that is dependent on matrix stiffness. We additionally show that the ability to activate fibroblasts on stiff matrices is dependent on the cell type from which the MVs are shed. Together, these results demonstrate the role of the mechanical properties of the matrix in regulating MV-induced fibroblast activation and matrix remodeling.

METHODS

Cell culture and reagents.

MDA-MB-231 malignant mammary adenocarcinoma cells (HTB-26; ATCC, Manassas, VA), MDA-MB-231 cells (HTB-26, ATCC) transfected to express Lifeact-GFP, and NIH 3T3 fibroblasts were maintained in DMEM (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, PA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals, Flowery Branch, GA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (ThermoFisher Scientific). MCF10A mammary epithelial cells (CRL-10317; ATCC) were maintained in DMEM-F12 (ThermoFisher Scientific) supplemented with 5% horse serum (ThermoFisher Scientific), 0.5 μg/ml hydrocortisone (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 20 ng/ml human epidermal growth factor (hEGF; ThermoFisher Scientific), 10 μg/ml insulin (Sigma), 100 ng/ml insulin (Sigma), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. MCF7 mammary adenocarcinoma cells (HTB-22; ATCC) were maintained in minimum essential medium (MEM; ThermoFisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. All cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2. Primary antibodies used were rabbit anti-flotillin-2 (no. 3436; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), rabbit anti-IκBα (no. 9242; Cell Signaling Technology), mouse anti-α-smooth muscle actin (anti-α-SMA; M0851; DAKO, Santa Clara, CA), and mouse anti-β-actin (A5316, Sigma). Secondary antibodies used were horseradish peroxidase (HRP) anti-rabbit (Rockland, Limerick, PA), HRP anti-mouse (Rockland), and AlexaFluor 488 conjugated to donkey anti-mouse (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA).

MV isolation and characterization.

Subconfluent MDA-MB-231, MCF10A, and MCF7 cells were incubated overnight in serum-free DMEM, serum-free DMEM-F12, or serum-free MEM, respectively. The conditioned medium was removed from the cells and centrifuged at 400 rpm. The supernatant was removed and again centrifuged at 400 rpm. The medium was then filtered through a 0.22 μm SteriFlip filter unit (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) and rinsed with serum-free media. The MVs retained by the filter were resuspended in their respective serum-free media. Nanoparticle tracking analysis (ZetaView ParticleMetrix, Germany) was used to determine the size and number of isolated MVs. N = 3 independent sets of MV isolations.

Western blotting.

Isolated MVs were rinsed with PBS on a 0.22 μm SteriFlip filter unit and lysed with Laemmli buffer. MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured on tissue culture plastic dishes, rinsed with PBS, and lysed with Laemmli buffer. Lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE. The proteins were then transferred to PVDF membranes. Transferred membranes were blocked with 5% milk in TBS-Tween. Membranes were incubated overnight in IκBα (1:1,000), flotillin-2 (1:1,000), and β-actin (1:1000) in 5% milk in TBS-Tween at 4°C. Membranes were then incubated in HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2,000) in 5% milk in TBS-Tween for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were imaged with a LAS-4000 imaging system (Fujifilm Life Science) after the addition of SuperSignal West Pico or West Dura Chemiluminescent Substrates (ThermoFisher Scientific). N = 3 independent sets of MV isolations.

Polyacrylamide gel preparation.

Polyacrylamide (PA) gels were fabricated as described elsewhere (7). Briefly, the ratio of acrylamide (40% wt/vol; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) to bis-acrylamide (2% wt/vol; Bio-Rad) was varied to tune gel stiffness from 1 to 20 kPa to mimic the heterogeneous stiffness in the tumor microenvironment (37). Moduli were changed by varying ratios of bis-acryalmide:acrylamide [% acrylamide:% bis-acrylamide (Young’s modulus (in kPa)]; [3:0.1 (1)], [7.5:0.175 (5)], and [12:0.19 (20)]. The PA gels were coated with 0.1 mg/ml rat tail type I collagen (Corning, Corning, NY).

Cell spreading assays.

NIH 3T3 fibroblasts were seeded on 1, 5, or 20 kPa PA gels in 1.6 ml of DMEM + 1% FBS. Cell media were additionally supplemented with either 400 μl of serum-free media or ~5.5 × 107 MVs suspended in 400 μl serum-free media. Phase contrast images were acquired at 20-min intervals using a 10×/0.3 N.A. objective on a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1.m microscope. Only cells without contact with adjacent cells that spread to an area of at least 30% greater than its initial area were analyzed. For area analysis, cells were outlined in ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD), and area was quantified. The data were regressed via a nonlinear least-squares regression to a modified error function of the form

| (1) |

previously used to describe cell spreading dynamics (41). Briefly, A is the area of the cell, t is the time after plating, t50 is the time at which the cell has spread to half its maximum, and A50 is half of the maximum area of the cell. N = 3+ independent sets of PA gels and MV isolations.

Phalloidin and α-SMA immunofluorescence and analysis.

NIH 3T3 fibroblasts were seeded on 1, 5, or 20 kPa PA gels in 1.6 ml of DMEM + 1% FBS. Cell media were supplemented with either 400 μl of serum-free media or ~5.5 × 107 MVs suspended in 400 μl serum-free media. After 24 h, cells were fixed with 3.2% vol/vol paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hartfield, PA) and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X-100 (J.T. Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ). Cells were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in 0.02% Tween in PBS and then incubated for 3 h at room temperature with mouse anti-α-smooth muscle actin (1:100). After being washed, cells were incubated for 1 h with AlexaFluor 488 conjugated to donkey anti-mouse (1:200). The cells were washed, and F-actin and nuclei were stained with AlexaFluor 568 phalloidin (1:500; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and DAPI (1:500; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), respectively. To image, gels were inverted onto a drop of Vectashield Mounting Media (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) placed on a glass slide. Fluorescent images were acquired with a 20×/1.0 N.A. water-immersion objective on a Zeiss LSM700 Upright laser-scanning microscope. For α-SMA expression, cells stained with phalloidin were outlined in ImageJ. Cell area was overlaid onto α-SMA images, and integrated density was measured. Corrected total cell α-SMA fluorescence was calculated by subtracting the cell area multiplied by the mean fluorescence of the background by the integrated density of the cell. N = 3 independent sets of PA gels and MV isolations.

Cell proliferation assays.

NIH 3T3 fibroblasts were serum-starved for 6 h and subsequently seeded on 1, 5, or 20 kPa PA gels in 1.6 ml of DMEM + 1% FBS. Cell media were supplemented with either 400 μl of serum-free media or ~5.5 × 107 MVs suspended in 400 μl serum-free media. After 24 h, 10 μM 5-ethynyl-2′-dexoyuridine (EdU; ThermoFisher Scientific) were added to the culture media for 2 h. Cells were fixed with 3.2% vol/vol paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and stained with the Click-iT EdU Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (1:500). Cells were imaged with a 20×/1.0 N.A. water-immersion objective on a Zeiss LSM700 Upright laser-scanning microscope. The percentage of EdU incorporation was calculated as the ratio of EdU-positive cells to the total number of cells. N = 3 independent sets of PA gels and MV isolations.

Traction force microscopy.

Traction force microscopy was performed as previously described (24). Briefly, polyacrylamide (PA) gels, embedded with 0.5 μm diameter fluorescent beads (Life Technologies), were prepared with Young’s moduli of 1 kPa, 5 kPa, and 20 kPa. Some traction force experiments were only conducted on 5 kPa and 20 kPa PA gels due to the difficulty of cell adhesion onto soft gels in low serum conditions. NIH 3T3 fibroblasts were allowed to adhere for 24 h in 1.6 ml of DMEM + 1% FBS supplemented with either 400 μl of serum-free media, ~5.5 × 107 MVs suspended in 400 μl serum-free media, 400 μl of conditioned media, or ~5.5 × 107 MVs suspended in 400 μl conditioned media. After 24 h, phase contrast images of single fibroblasts and fluorescent images of the bead field at the surface of the PA gel were acquired. Fibroblasts were removed from the PA gel using 0.25% trypsin/EDTA (Life Technologies), and a fluorescent image of the bead field was acquired after cell removal. Bead displacements between the stressed and null states and fibroblast area were calculated and analyzed using the LIBTRC library developed by M. Dembo (Dept. of Biomedical Engineering, Boston Univ., Boston, MA) (10). The overall cellular force is the integral of the traction vectors over the total cell area. Outliers were removed using the ROUT method with Q = 0.2%. N = 3 independent sets of PA gels and MV isolations.

Collagen gel contraction.

Type I collagen was isolated from rat tail tendons (Rockland) and solubilized to form 10 mg/ml stock solutions as previously described (30). Briefly, collagen stock solutions were mixed with 0.5 M ribose to form collagen solutions containing a final concentration of 100 mM ribose in 0.1% sterile acetic acid and incubated at 4°C for 5 days. Glycated collagen solutions were neutralized with 1 M sodium hydroxide (Sigma) in 10× PBS buffer (Life Technologies) and mixed with HEPES (EMD Millipore) and sodium bicarbonate (JT Baker) in 10× PBS to form 1.5 mg/ml collagen gels. When added to collagen, ribose interacts with amino groups on proteins to form Schiff bases that rearrange into Amadori products. Amadori products form advanced glycation end products (AGE) that accumulate on proteins and result in cross-link formation (30). 3T3 fibroblasts were seeded at a density of 200,000 fibroblasts/ml of collagen gel for a final volume of 500 μl collagen gels. Collagen gels were cultured in 1.1 mL DMEM + 1% FBS and supplemented with either 400 μl of serum-free media or ~5.5 × 107 MVs suspended in 400 μl serum-free media. Gels were unattached from the well-plate by tracing around the outward edge of the gel with a pipet tip. Gels were allowed to contract for 48 h and subsequently imaged. N = 4 independent sets of collagen gels and MV isolations.

Statistical analysis.

All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) or Excel 2016 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Where appropriate, data were compared with a Student’s t-test or with a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Sidak multiple comparisons test. All data are reported as mean ± standard error.

RESULTS

Highly malignant breast cancer cells release MVs.

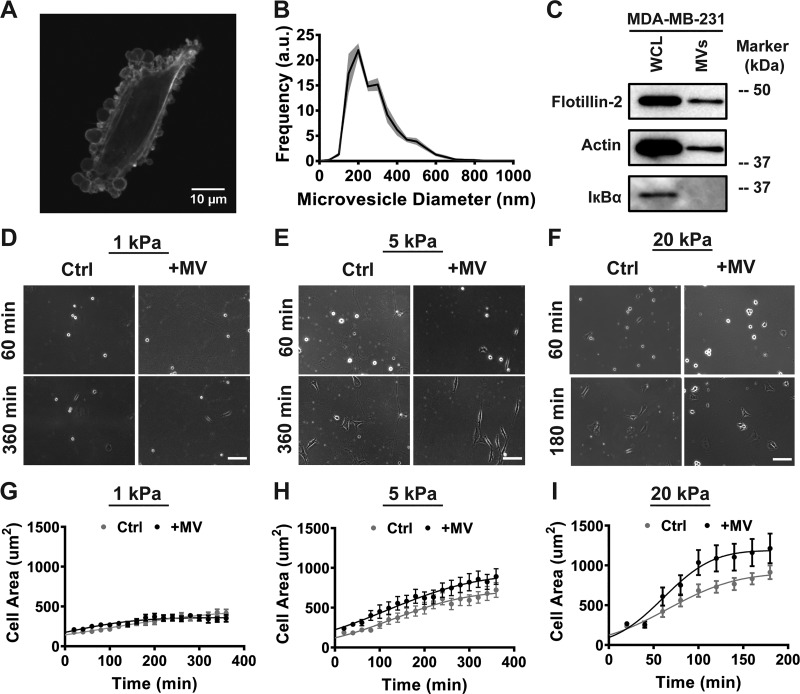

To examine the role of cancer cell-derived MVs on fibroblasts, we first isolated MVs from the highly malignant MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. The release of MVs by breast cancer cells was visualized by culturing LifeAct-GFP MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells in serum-free media (Fig. 1A). MVs were isolated from breast cancer cells using centrifugation and subsequent filtration. Isolated MVs were confirmed to be within the expected size distribution (200 nm to 1 μm) using nanoparticle tracking analysis (Fig. 1B). Western blot analysis confirmed the expression of the MV marker flotillin-2 in MV lysates and the absence of the cytosolic marker IκBα, showing no cytosolic contamination from intact cells in the MV samples (Fig. 1C). These results are consistent with prior studies suggesting that MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells release extracellular vesicles within the MV class (2, 5, 17).

Fig. 1.

Cancer cell-derived microvesicles (MVs) increase fibroblast early spreading dynamics on stiff matrices. A: fluorescent image of MDA-MB-231 cell in serum-free media. B: size distribution of isolated MVs; a.u., arbitrary units. C: representative immunoblots of actin, the MV marker flotillin-2, and the cytosolic-specific marker IκBα in whole cell lysates (WCL) and MV lysates (MVs). D–F: representative images of early spreading in fibroblasts treated with serum-free media alone (Ctrl) or MVs (+MV) on 1 kPa (D), 5 kPa (E), and 20 kPa (F) polyacrylamide (PA) gels. Scale bar = 100 μm. G–I: measurements of fibroblast cell area during early cell spreading, taken every 20 min, on 1 kPa (G; Ctrl: n = 24; +MV: n = 14), 5 kPa (H; Ctrl: n = 34; +MV: n = 27), and 20 kPa PA gels (I; Ctrl: n = 30; +MV: n = 28). Data points fit to a nonlinear least-squares regression of a modified error function. Plots are means ± SE. N = 3+ independent sets of PA gels and MV isolations.

Fibroblasts in the tumor stroma are exposed to a range of matrix stiffness due to heterogeneities in ECM composition. As increased matrix stiffness has been shown to directly promote fibroblast spreading and the ability of a cell to spread directly affects its function, we investigated the relationship between matrix stiffness and MV-mediated fibroblast spreading (8, 18, 29, 43, 52). MVs were applied to fibroblasts at the time of seeding on PA gels of varying stiffness (1–20 kPa), spanning the range of matrix stiffness in physiologically relevant breast tissue (37). Cell spreading was monitored using time-lapse microscopy, and the data were fit to a modified error function to obtain the half-maximum spreading area, A50, and the half-maximum spreading time, t50 (41) (see methods for details). Table 1 presents the regression parameter values for Fig. 1 data. As expected, significant differences in A50 were calculated between increasing PA gel stiffness within control or MV conditions (Table 2), highlighting the role of matrix stiffness in fibroblast spreading. At a stiffness mimicking healthy breast tissue (1 kPa), MVs did not affect early fibroblast spreading dynamics or fibroblast cell area after 24 h of culture (Fig. 1, D and G, and Fig. 2, A and B); no change in the A50 was observed between control and MV conditions (Table 2). However, on moderately stiff PA gels mimicking tumorigenic breast tissue (5 kPa), culture with MVs increased the rate of early fibroblast spreading (Fig. 1, E and H). Likewise, a significant difference in the A50 was calculated between control and MV conditions on the 5 kPa PA gel (Table 2). After 24 h of culture, no change in fibroblast cell area was noted between control and MV conditions on 5 kPa PA gels (Fig. 2, A and B). Additionally, increased rate of early fibroblast spreading was evident in fibroblast culture with MVs on the stiffest substrate tested (20 kPa), where the rate of early spreading was increased as well as fibroblast cell area throughout the entire observation period (Fig. 1, F and I, and Fig. 2, A and B). A significant difference in A50 was observed between control and MV conditions on the 20 kPa gel (Table 2) as well as a significant difference between cell area after 24 h of culture (Fig. 2, A and B). These results indicate that MVs derived from highly malignant breast cancer cells cause an increase in early fibroblast spreading on stiff matrices, highlighting the role of matrix mechanical properties in regulating cellular interactions and fibroblast function in the tumor microenvironment.

Table 1.

Regression parameter values for data presented in Fig. 1

| 1 kPa |

5 kPa |

20 kPa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctrl | +MV | Ctrl | +MV | Ctrl | +MV | |

| R2 | 0.9701 | 0.89 | 0.9745 | 0.9845 | 0.9782 | 0.9766 |

| t50 | 95.72 | 5.069 | 130.5 | 113.6 | 65.58 | 62 |

| A50 | 227.2 | 179.6 | 359.9 | 462.6 | 451.2 | 593.1 |

Ctrl, control; MV, microvesicle; t50, time at which the cell has spread to half its maximum; A50, half of the maximum area of the cell.

Table 2.

Statistical comparison of regression parameter values using two-way ANOVA with Sidak test for multiple comparisons

| A50 | |

|---|---|

| 1 kPa Ctrl vs. 1 kPa +MV | N.S. |

| 5 kPa Ctrl vs. 5 kPa +MV | † |

| 20 kPa Ctrl vs. 20 kPa +MV | † |

| 1 kPa Ctrl vs. 5 kPa Ctrl | ‡ |

| 5 kPa Ctrl vs. 20 kPa Ctrl | * |

| 1 kPa +MV vs. 5 kPa +MV | ‡ |

| 5 kPa +MV vs. 20 kPa +MV | † |

Ctrl, control; MV, microvesicle; A50, half of the maximum area of the cell; N.S., not significant.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.001,

P < 0.0001.

Fig. 2.

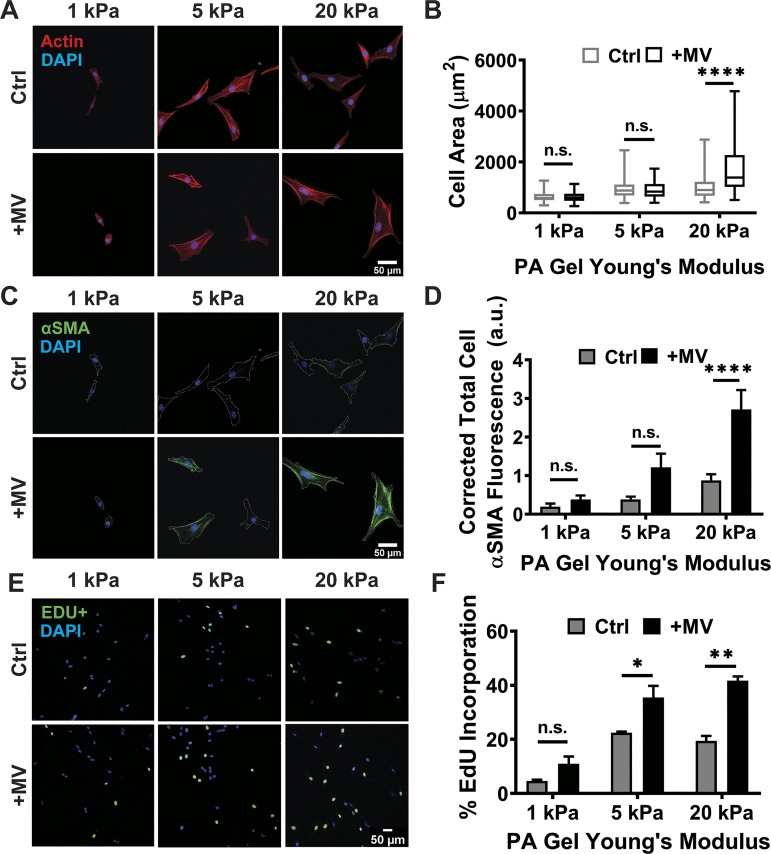

Cancer cell-derived microvesicles (MVs) induce cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF)-like fibroblast phenotypes on stiff matrices. A: representative images of fibroblast actin (red) after culture in serum-free media alone (Ctrl) or MVs (+MV) on 1, 5, or 20 kPa polyacrylamide (PA) gels. B: measurements of fibroblast cell area after 24 h of culture on 1 kPa (Ctrl: n = 75; +MV: n = 75), 5 kPa (Ctrl: n = 80; +MV: n = 80), and 20 kPa PA gels (Ctrl: n = 80; +MV: n = 80) in Ctrl and +MV conditions. Plots are median ± the minimum and maximum values. C: representative images of fibroblast α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; green) after 24 h of culture in Ctrl and +MV conditions. Cell perimeter is outlined in dashed white line. D: measurements of fibroblast α-SMA fluorescence after 24 h of culture on 1 kPa (Ctrl: n = 67; +MV: n = 64), 5 kPa (Ctrl: n = 66; +MV: n = 68), and 20 kPa PA gels (Ctrl: n = 80; +MV: n = 75) in Ctrl and +MV conditions. E: representative fluorescent images of fibroblast 5-ethynyl-2′-dexoyuridine (EdU) incorporation after treatment with serum-free media alone (Ctrl) or MVs (+MV) for 24 h on 1, 5, or 20 kPa PA gels. EdU+ cells are in green. DAPI is in blue. F: fibroblast proliferation after culture in Ctrl or +MV conditions for 24 h as determined by Click-iT EdU staining. Percentages are relative to total cell number. Ten representative images taken for each condition; over 500 cells were analyzed for each condition. N = 3 independent sets of PA gels and MV isolations. Plots are means ± SE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 from two-way ANOVA with Sidak test for multiple comparisons; n.s., not significant.

Cancer cell-derived MVs induce CAF-like fibroblast phenotypes on stiff matrices.

After 24 h of culture with cancer cell-derived MVs, fibroblasts on 1 and 5 kPa PA gels exhibited no change in cell area compared with control conditions while fibroblasts on 20 kPa PA gels exhibited significantly larger cell area following treatment with MV (Fig. 2, A and B). Since MVs induce a more robust spreading response when cells are on stiff substrates, we hypothesized that cancer cell-derived MVs in conjunction with a stiff microenvironment may help activate fibroblasts to their cancer-associated state. α-SMA expression, a marker of fibroblast activation (19, 32, 45), was quantified to measure fibroblast activation. In control conditions, α-SMA expression slightly increased with increasing matrix stiffness. After 24 h of culture with MVs, fibroblasts on 1 and 5 kPa PA gels exhibited no significant increase in α-SMA expression, compared with control conditions (Fig. 2, C and D). However, a robust increase in α-SMA expression was evident in fibroblasts cultured with MVs on 20 kPa PA gels, compared with control conditions (Fig. 2, C and D). These results suggest that MV-induced fibroblast activation increases with matrix stiffness. Given that the ability of cells to spread and fibroblast activation have been shown to be related to proliferation (8, 22), and our data indicate MVs affect spreading and activation, we sought to determine if cancer cell-derived MVs affect fibroblast proliferation on matrices of varying physiological stiffness. Fibroblast proliferation in control conditions increases on stiffer (5 and 20 kPa) matrices compared with more compliant (1 kPa) matrices, and MVs significantly increased fibroblast proliferation on both 5 and 20 kPa matrix conditions (Fig. 2, E and F). These results indicate that matrix stiffness enhances MV-induced fibroblast proliferation.

Cancer cell-derived MVs increase fibroblast contraction on stiff matrices.

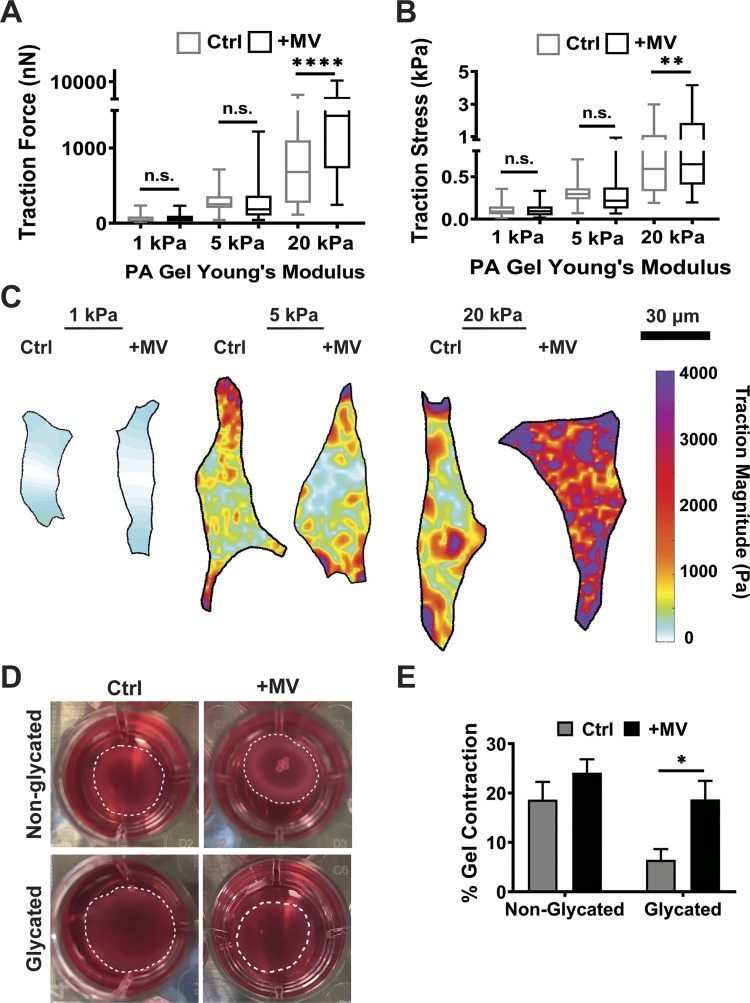

As we observed increased cell spreading and α-SMA expression on stiff substrates in response to MVs, we sought to assess whether cell contractility also increases. For a fibroblast to remodel its surrounding matrix, it uses actomyosin contractility to generate force to rearrange the matrix (42). To assess the effects of cancer cell-derived MVs on fibroblast-matrix interactions, we utilized traction force microscopy to measure cellular contractile force following MV treatment. Given that our data indicate that matrix stiffness alters fibroblast spreading in response to MVs, and given that fibroblasts encounter heterogeneous stromal environments with varying stiffness during cancer progression (3, 12, 28, 55), we measured fibroblast traction force on substrates of varying stiffness (1–20 kPa). At a stiffness mimicking healthy breast tissue (1 kPa), fibroblasts exhibited no change in total traction force per cell or traction stress when cultured with MVs for 24 h (Fig. 3, A–C). Likewise, no statistically significant change in total traction force or traction stress was exhibited in fibroblasts cultured on a moderate stiffness mimicking tumorigenic conditions in breast tissue (5 kPa) (Fig. 3, A–C). However, on 20 kPa substrates, mimicking the highest ECM stiffness found in breast cancer (37), MVs induced a robust increase in fibroblast traction force (Fig. 3A). Since the force is the traction stress integrated over the area, these data indicate that this change is not simply a result of the increased cell area observed in Fig. 2. Fibroblasts cultured with MVs on the stiff matrices also exhibited an increase in traction stress, indicating an increase in the ability of fibroblasts to contract the matrix (Fig. 3, B and C). These data suggest that increasing matrix stiffness enhances the effects of cancer cell-derived MVs on fibroblast contractility.

Fig. 3.

Cancer cell-derived microvesicles (MVs) increase fibroblast contraction on stiff matrices. A: traction force measurements of fibroblasts treated with serum-free media alone (Ctrl) or MVs (+MV) on 1 kPa (Ctrl: n = 64; +MV: n = 44), 5 kPa (Ctrl: n = 47; +MV: n = 51), and 20 kPa (Ctrl: n = 39; +MV: n = 42) kPa polyacrylamide (PA) gels. B: traction stress measurements (Traction Force/Cell Area) of fibroblasts in Ctrl and +MV culture conditions on 1 kPa (Ctrl: n = 64; +MV: n = 44), 5 kPa (Ctrl: n = 47; +MV: n = 51), and 20 kPa (Ctrl: n = 39; +MV: n = 42) PA gels; n = 3 independent sets of PA gels and MV isolations. Plots are median ± the minimum and maximum values. C: representative traction stress maps of fibroblasts in Ctrl and +MV culture conditions on 1, 5, and 20 kPa PA gels. D: representative images of collagen gel contraction after 48 h. E: collagen gel contraction by fibroblasts treated with serum-free media alone (Ctrl) or MVs (+MV) for 48 h in nonglycated (n = 12) or glycated (n = 12) matrices. N = 4 independent sets of collagen gels and MV isolations. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 from two-way ANOVA with Sidak test for multiple comparisons; n.s., not significant.

To further investigate the increased traction force initiated by cancer-derived MVs, we assessed the ability of fibroblasts to contract collagen gels. The stiffness of collagen gels was modulated by nonenzymatic glycation without altering the density of collagen gel (30). Fibroblasts were cultured in nonglycated and glycated 1.5 mg/ml collagen gels, with Young’s Moduli of ~175 and 575 Pa, respectively (30), for 48 h in control or MV conditions. Fibroblasts cultured in control conditions exhibited greater collagen gel contraction in more compliant matrices compared with stiffer matrices (Fig. 3, D and E). Fibroblasts cultured with MVs exhibited significantly increased collagen gel contraction compared with control conditions in glycated matrices (Fig. 3, D and E). These data reveal that MVs increase fibroblast collagen gel contraction to a greater magnitude on stiffer, glycated matrices. These results are consistent with our data on two-dimensional substrates (Fig. 3, A–C), which indicates cancer cell-derived MVs increase the ability of fibroblasts to contract stiffer matrices. Specifically, this system extends the effects of MVs on fibroblasts to more physiologically relevant three-dimensional microenvironments.

Cancer cell-derived MVs are significant regulators of fibroblast function independently of the overall cancer cell secretome.

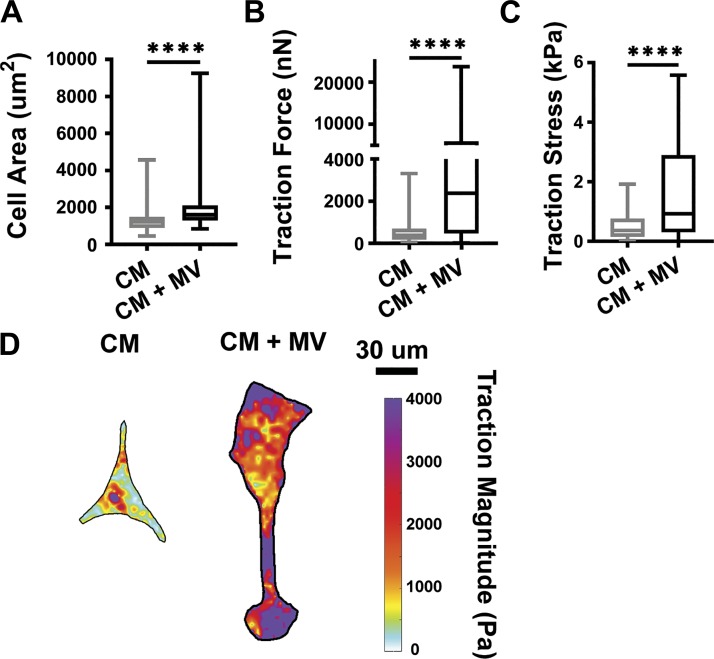

Cancer cells release a variety of components into the extracellular space, including cell motility factors, growth factors, proteases, and cytokines, in addition to extracellular vesicles (35). As MVs are just one of the many components released from cancer cells, we sought to determine whether MVs are a physiology significant regulator of fibroblast function in the tumor microenvironment compared with the overall secretome. To compare the effects of MVs to other components of the cancer cell secretome, isolated MVs were resuspended in cancer cell conditioned media and applied to fibroblasts. On stiff 20 kPa PA gels, fibroblasts cultured with MVs suspended in conditioned media exhibited increased cell area (Fig. 4A), traction force (Fig. 4B), and traction stress (Fig. 4, C and D), compared with fibroblasts cultured with conditioned media alone. These data indicate that MVs are not outcompeted by other components of the cancer cell secretome.

Fig. 4.

Cancer-cell derived microvesicles (MVs) alter fibroblast function independently of other secreted factors. A: cell area of fibroblasts treated with conditioned media (CM) or conditioned media supplemented with MVs (CM + MV) for 24 h on 20 kPa polyacrylamide (PA) gels (CM: n = 72, CM + MV: n = 78). B: traction force measurements of fibroblasts in CM and CM + MV culture conditions on 20 kPa PA gels (CM: n = 41, CM + MV: n = 50). C: traction stress measurements (Traction Force/Cell Area) of fibroblasts in CM and CM + MV culture conditions on 20 kPa PA gels (CM: n = 41, CM + MV: n = 50). D: representative traction stress maps of fibroblasts in CM and CM + MV culture conditions on 20 kPa PA gels. N = 3 independent sets of PA gels and MV isolations. Plots are median ± the minimum and maximum values. ****P < 0.0001 from Student’s unpaired t-test.

MV-induced fibroblast activation is MV cell-type dependent.

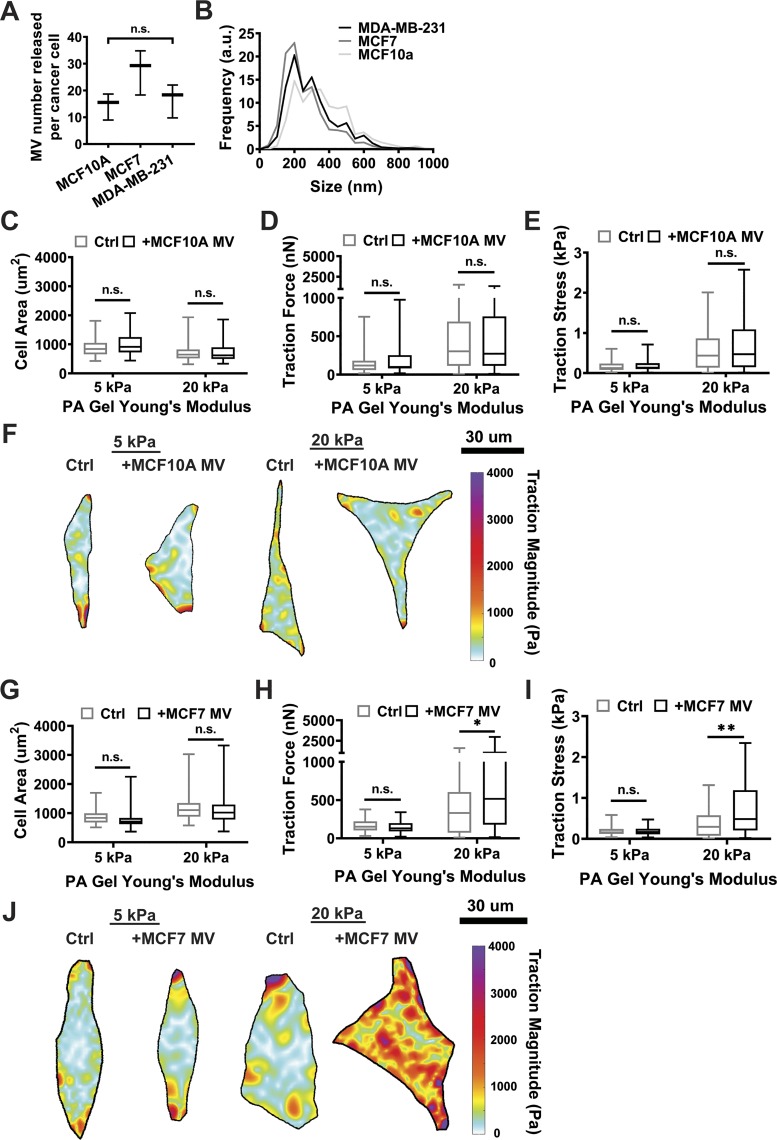

To determine whether the cell type from which the MVs are shed influences the matrix stiffness-dependent effect of MVs on fibroblasts, MVs were isolated from the MCF10A breast epithelial cells and MCF7 breast cancer cells, which are considered less aggressive than MDA-MB-213 cells. MCF10As, MCF7s, and MDA-MB-231 cells all released comparable numbers of MVs (Fig. 5A). MVs isolated from MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells had similar size distributions, while MCF10A MVs shift toward larger diameters (Fig. 5B). To investigate the effects of these MVs on fibroblast function, fibroblasts were cultured with MCF10A or MCF7 MVs on both 5 and 20 kPa PA gels. Fibroblasts cultured with MCF10A MVs exhibited no change in cell area, traction force, or traction stress on either 5 or 20 kPa PA gels (Fig. 5, C–F). Fibroblasts cultured with MCF7 MVs exhibited no change in cell area on either 5 or 20 kPa PA gels (Fig. 5G), but cell contractility increased on stiff 20 kPa PA gels (Fig. 5, H–J). These data indicate that the effect of MVs on fibroblast function is cell-type dependent, as MVs from nonmalignant epithelial cells had no influence on fibroblast cell area or traction force. These data also suggest that the effect may be dependent on cancer cell malignancy, as the magnitude of change in fibroblast contractility appeared to increase from nonmalignant (MCF10A), to weakly metastatic (MCF7), to more aggressive (MDA-MB-231) cancer cells. However, MVs from additional cell lines from different cancer types would need to be tested to fully address this finding.

Fig. 5.

Microvesicle (MV)-induced fibroblast activation is MV cell-type dependent. A: number of MVs released by MCF10A, MCF7, and MDA-MB-231 cancer cells. B: MCF10A, MCF7, and MDA-MB-231 MV size distributions. N = 3 independent MV isolations. C: cell area measurements of fibroblasts treated with serum-free media alone (Ctrl) or MCF10A MVs (+MCF10A MV) on 5 kPa (Ctrl: n = 67; +MCF10A MV: n = 66) and 20 kPa (Ctrl: n = 75; +MCF10A MV: n = 75) polyacrylamide (PA) gels. D: traction force measurements of fibroblasts in Ctrl and +MCF10A MV culture conditions on 5 kPa (Ctrl: n = 42; +MCF10A MV: n = 33) and 20 kPa (Ctrl: n = 51; +MCF10A MV: n = 49) PA gels. E: traction stress measurements (Traction Force/Cell Area) of fibroblasts in Ctrl and +MCF10A MV culture conditions on 5 kPa (Ctrl: n = 42; +MCF10A MV: n = 33) and 20 kPa (Ctrl: n = 51; +MCF10A MV: n = 49) PA gels. F: representative traction stress maps of fibroblasts in Ctrl and +MCF10A MV culture conditions on 5 and 20 kPa PA gels. G: cell area measurements of fibroblasts treated with serum-free media alone (Ctrl) or MCF7 MVs (+MCF7 MV) on 5 kPa (Ctrl: n = 63; +MCF7 MV: n = 63) and 20 kPa (Ctrl: n = 68; +MCF7 MV: n = 69) PA gels. H: traction force measurements of fibroblasts in Ctrl and +MCF10A MV culture conditions on 5 kPa (Ctrl: n = 30; +MCF7 MV: n = 30) and 20 kPa (Ctrl: n = 42; +MCF7 MV: n = 40) gels. I: traction stress measurements (Traction Force/Cell Area) of fibroblasts in Ctrl and +MCF10A MV culture conditions on 5 kPa (Ctrl: n = 30; +MCF7 MV: n = 30) and 20 kPa (Ctrl: n = 42; +MCF7 MV: n = 40) PA gels. J: representative traction stress maps of fibroblasts in Ctrl and +MCF7 MV culture conditions on 5 and 20 kPa PA gels. N = 3 independent sets of PA gels and MV isolations. Plots are median ± the minimum and maximum values. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 from two-way ANOVA with Sidak test for multiple comparisons; n.s. not significant.

DISCUSSION

Recent evidence has highlighted the ability of EVs to transform epithelial and stromal cells to promote cancer progression. Specifically, exosomes have been implicated in the promotion of cancer cell migration, chemotaxis, tumorigenicity, and chemoresistance and the transformation of stromal fibroblasts and macrophages to cancer-promoting states (11, 15, 16, 21, 47, 50, 51, 54). These phenotypes are the result of the transfer of oncogenic proteins from cancer cells, including mutant KRAS proteins, transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), and microRNA (11, 15, 16, 54). However, the effects of MVs, a distinct class of EVs released from the plasma membrane of cancer cells, on the tumor microenvironment are just beginning to be uncovered. Here, we show that MVs induce changes in fibroblast spreading, α-SMA expression, proliferation, cell-generated traction forces, and collagen gel compaction. Importantly, the MV-induced phenotypes assessed in this study were enhanced with matrix stiffness.

Our data suggest that matrix stiffness may prime nontransformed fibroblasts for activation by MV cargo. Previously, matrix stiffness was shown to sensitize various cells to respond to growth factors. Matrix stiffening was shown to sensitize cells to epidermal growth factor (EGF), with implications in epithelial cell proliferation (23). Similarly, increased matrix stiffness was shown to increase EGF-dependent growth in epithelial cells (34). Additionally, matrix stiffness enhances vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) internalization, signaling, and proliferation in endothelial cells (25). As such, matrix stiffness may play a role in fibroblast sensitivity to MV cargo.

Other than priming cells for response to MVs, the stiffness-dependent differences that we have identified may also be due to differences in MV uptake. Conflicting evidence exists as to whether endocytosis is altered with matrix stiffness. Epithelial cells cultured on varying PA gel stiffness showed increased nanoparticle uptake on 20 kPa PA gels relative to 1 kPa gels (53). However, it has also been shown that epithelial cells cultured on soft matrices had significantly enhanced EV uptake, compared with tissue culture polystyrene (48). Additionally, uptake of mitogen-activated protein kinase activated protein kinase II (MK2) by mesothelial cells is increased on soft substrates, compared with stiff substrates (6). As such, matrix stiffness may play a role in MV uptake by stromal cells; however, it is not yet clear and requires further investigation.

Previously, matrix stiffness was identified as a central regulator of fibroblast activation and fibroblast-induced fibrosis in the lung. Specifically, TGF-β1 was shown to enhance fibroblast traction forces on stiff matrices mimicking fibrotic lung tissue but not on matrices mimicking the stiffness of healthy lung tissue (29). Additionally, yes-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ) were identified as mechano-activated regulators of the matrix stiffness-driven feedback loop that amplifies lung fibrosis (27). Together, these results suggest a role for matrix stiffness in fibroblast-induced fibrosis of the lung, where the fibrotic ECM is both a cause and a consequence of fibroblast activation. We identify a similar phenomenon in the tumor microenvironment. We speculate that a feedback loops exists where matrix stiffness amplifies MV-induced fibroblast activation, which further stiffens the matrix to activate both fibroblasts and other cell types in the tumor microenvironment. As a whole, these results suggest that the compliance of healthy tissue may inhibit inhibit microvesicle-induced fibroblast activation.

Interestingly, MV release from cancer cells is also likely regulated by matrix stiffness, further adding to the consequences of this feedback loop. Previously, MV shedding was determined to be regulated by the GTPase RhoA (26). Significant evidence exists to suggest that RhoA activity in cells is highly regulated by matrix stiffness (36). As such, it is likely that the increased matrix remodeling by MV-activated fibroblasts also results in increased MV release from cancer cells to further activate stromal cells. This feedback loop would then result in further matrix stiffening.

Here, we focus on the primary tumor microenvironment; however, it is known that MVs have been identified in the circulation of cancer patients (31). The transfer of exosomal contents to recipient cells is believed to play a role in the preparation of the premetastatic niche (9, 20). Exosomal integrins were found contribute to the premetastatic niche and direct organ-specific colonization by fusing with cells in a tissue-specific fashion, shown to play roles in brain, lung, and liver metastasis (20). Additionally, exosomal microRNA associated with osteoblast differentiation was identified in cancer exosomes, believed to play a role in the preparation of the premetastatic niche for bone metastasis (9). Interestingly, it has also been shown that CAFs in breast tumors select for cancer cell clones that are more equipped for bone metastasis (56). Consequently, MVs released by the primary tumor may both travel to distant sites in the body to prime the premetastatic niche as well as activate fibroblasts surrounding the primary tumor involved in metastatic cell selection. Further studies are required to determine if the MV class of extracellular vesicles are identified in distant tissues. Based on our data, it is possible that MVs may play a role in the development of the premetastatic niche of stiffer tissues, such as breast to bone metastasis. While we focus here on contractility, it is also possible that MVs may induce the release of soluble signals from fibroblasts that may also play a role in priming.

Overall, our work reveals a novel mediator in the bidirectional relationship between cancer cells and fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment. As fibroblast activation is associated with cancer progression, cancer-derived MVs appear to play a role in transforming fibroblasts to an activated state to prime the tumor microenvironment for metastasis. We hypothesize that a matrix stiffness feedback loops exists in which MV-induced fibroblast activation further stiffens the matrix promote cancer progression. Additionally, the robust response of fibroblasts to culture with MVs on matrices ranging from 5 to 20 kPa highlights the sensitivity of fibroblasts to MV contents at the tumor periphery. Significantly, this region is where fibroblasts form tracks in the matrix or align fibers to promote cancer cell invasion. Future studies should assess the ability of cancer cells to sense MV-mediated fibroblast remodeling.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Science Foundation-National Institutes of Health Public Employment Service Office Award 1740900 (to C. A. Reinhart-King) and Scholarship for the Next Generation of Scientists from the Cancer Research Society and National Cancer Institute Grant K99CA212270 (to F. Bordeleau).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.C.S., F.B., M.A.A., R.A.C., and C.R.-K. conceived and designed research; S.C.S. performed experiments; S.C.S. and J.Z. analyzed data; S.C.S., F.B., and C.R.-K. interpreted results of experiments; S.C.S. prepared figures; S.C.S. drafted manuscript; S.C.S., F.B., J.Z., M.A.A., and C.R.-K. edited and revised manuscript; S.C.S., F.B., J.Z., M.A.A., R.A.C., and C.R.-K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alissa Weaver for the use of the ZetaView ParticleMetrix.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antonyak MA, Cerione RA. Microvesicles as mediators of intercellular communication in cancer. Cancer Cell Signaling, edited by Robles-Flores M. New York: Humana, p. 147–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonyak MA, Li B, Boroughs LK, Johnson JL, Druso JE, Bryant KL, Holowka DA, Cerione RA. Cancer cell-derived microvesicles induce transformation by transferring tissue transglutaminase and fibronectin to recipient cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 4852–4857, 2011. [Erratum in Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 17569, 2011]. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017667108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker EL, Bonnecaze RT, Zaman MH. Extracellular matrix stiffness and architecture govern intracellular rheology in cancer. Biophys J 97: 1013–1021, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balaj L, Lessard R, Dai L, Cho YJ, Pomeroy SL, Breakefield XO, Skog J. Tumour microvesicles contain retrotransposon elements and amplified oncogene sequences. Nat Commun 2: 180, 2011. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bordeleau F, Chan B, Antonyak MA, Lampi MC, Cerione RA, Reinhart-King CA. Microvesicles released from tumor cells disrupt epithelial cell morphology and contractility. J Biomech 49: 1272–1279, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brugnano JL, Panitch A. Matrix stiffness affects endocytic uptake of MK2-inhibitor peptides. PLoS One 9: e84821, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Califano JP, Reinhart-King CA. A balance of substrate mechanics and matrix chemistry regulates endothelial cell network assembly. Cell Mol Bioeng 1: 122–132, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s12195-008-0022-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen CS, Mrksich M, Huang S, Whitesides GM, Ingber DE. Geometric control of cell life and death. Science 276: 1425–1428, 1997. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5317.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa-Silva B, Aiello NM, Ocean AJ, Singh S, Zhang H, Thakur BK, Becker A, Hoshino A, Mark MT, Molina H, Xiang J, Zhang T, Theilen TM, García-Santos G, Williams C, Ararso Y, Huang Y, Rodrigues G, Shen TL, Labori KJ, Lothe IM, Kure EH, Hernandez J, Doussot A, Ebbesen SH, Grandgenett PM, Hollingsworth MA, Jain M, Mallya K, Batra SK, Jarnagin WR, Schwartz RE, Matei I, Peinado H, Stanger BZ, Bromberg J, Lyden D. Pancreatic cancer exosomes initiate pre-metastatic niche formation in the liver. Nat Cell Biol 17: 816–826, 2015. doi: 10.1038/ncb3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dembo M, Wang YL. Stresses at the cell-to-substrate interface during locomotion of fibroblasts. Biophys J 76: 2307–2316, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77386-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demory Beckler M, Higginbotham JN, Franklin JL, Ham AJ, Halvey PJ, Imasuen IE, Whitwell C, Li M, Liebler DC, Coffey RJ. Proteomic analysis of exosomes from mutant KRAS colon cancer cells identifies intercellular transfer of mutant KRAS. Mol Cell Proteomics 12: 343–355, 2013. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.022806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denis M, Gregory A, Bayat M, Fazzio RT, Whaley DH, Ghosh K, Shah S, Fatemi M, Alizad A. Correlating tumor stiffness with immunohistochemical subtypes of breast cancers: prognostic value of comb-push ultrasound shear elastography for differentiating luminal subtypes. PLoS One 11: e0165003, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Mohri H, Wu Y, Mohanty S, Ghosh G. Impact of matrix stiffness on fibroblast function. Mater Sci Eng C 74: 146–151, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erdogan B, Webb DJ. Cancer-associated fibroblasts modulate growth factor signaling and extracellular matrix remodeling to regulate tumor metastasis. Biochem Soc Trans 45: 229–236, 2017. doi: 10.1042/BST20160387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fabbri M, Paone A, Calore F, Galli R, Gaudio E, Santhanam R, Lovat F, Fadda P, Mao C, Nuovo GJ, Zanesi N, Crawford M, Ozer GH, Wernicke D, Alder H, Caligiuri MA, Nana-Sinkam P, Perrotti D, Croce CM. MicroRNAs bind to Toll-like receptors to induce prometastatic inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: E2110–E2116, 2012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209414109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang T, Lv H, Lv G, Li T, Wang C, Han Q, Yu L, Su B, Guo L, Huang S, Cao D, Tang L, Tang S, Wu M, Yang W, Wang H. Tumor-derived exosomal miR-1247-3p induces cancer-associated fibroblast activation to foster lung metastasis of liver cancer. Nat Commun 9: 191, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02583-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng Q, Zhang C, Lum D, Druso JE, Blank B, Wilson KF, Welm A, Antonyak MA, Cerione RA. A class of extracellular vesicles from breast cancer cells activates VEGF receptors and tumour angiogenesis. Nat Commun 8: 14450, 2017. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folkman J, Moscona A. Role of cell shape in growth control. Nature 273: 345–349, 1978. doi: 10.1038/273345a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinz B, Celetta G, Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Chaponnier C. Alpha-smooth muscle actin expression upregulates fibroblast contractile activity. Mol Biol Cell 12: 2730–2741, 2001. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.9.2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoshino A, Costa-Silva B, Shen T-L, Rodrigues G, Hashimoto A, Tesic Mark M, Molina H, Kohsaka S, Di Giannatale A, Ceder S, Singh S, Williams C, Soplop N, Uryu K, Pharmer L, King T, Bojmar L, Davies AE, Ararso Y, Zhang T, Zhang H, Hernandez J, Weiss JM, Dumont-Cole VD, Kramer K, Wexler LH, Narendran A, Schwartz GK, Healey JH, Sandstrom P, Labori KJ, Kure EH, Grandgenett PM, Hollingsworth MA, de Sousa M, Kaur S, Jain M, Mallya K, Batra SK, Jarnagin WR, Brady MS, Fodstad O, Muller V, Pantel K, Minn AJ, Bissell MJ, Garcia BA, Kang Y, Rajasekhar VK, Ghajar CM, Matei I, Peinado H, Bromberg J, Lyden D. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature 527: 329–335, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nature15756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahlert C, Kalluri R. Exosomes in tumor microenvironment influence cancer progression and metastasis. J Mol Med (Berl) 91: 431–437, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1020-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalluri R. The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 16: 582–598, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JH, Asthagiri AR. Matrix stiffening sensitizes epithelial cells to EGF and enables the loss of contact inhibition of proliferation. J Cell Sci 124: 1280–1287, 2011. doi: 10.1242/jcs.078394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kraning-Rush CM, Califano JP, Reinhart-King CA. Cellular traction stresses increase with increasing metastatic potential. PLoS One 7: e32572, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaValley DJ, Zanotelli MR, Bordeleau F, Wang W, Schwager SC, Reinhart-King CA. Matrix stiffness enhances VEGFR-2 internalization, signaling, and proliferation in endothelial cells. Converg Sci Phys Oncol 3: 044001, 2017. doi: 10.1088/2057-1739/aa9263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li B, Antonyak MA, Zhang J, Cerione RA. RhoA triggers a specific signaling pathway that generates transforming microvesicles in cancer cells. Oncogene 31: 4740–4749, 2012. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu F, Lagares D, Choi KM, Stopfer L, Marinković A, Vrbanac V, Probst CK, Hiemer SE, Sisson TH, Horowitz JC, Rosas IO, Fredenburgh LE, Feghali-Bostwick C, Varelas X, Tager AM, Tschumperlin DJ. Mechanosignaling through YAP and TAZ drives fibroblast activation and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 308: L344–L357, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00300.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malandrino A, Mak M, Kamm RD, Moeendarbary E. Complex mechanics of the heterogeneous extracellular matrix in cancer. Extreme Mech Lett 21: 25–34, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.eml.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marinković A, Mih JD, Park JA, Liu F, Tschumperlin DJ. Improved throughput traction microscopy reveals pivotal role for matrix stiffness in fibroblast contractility and TGF-β responsiveness. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 303: L169–L180, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00108.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mason BN, Starchenko A, Williams RM, Bonassar LJ, Reinhart-King CA. Tuning three-dimensional collagen matrix stiffness independently of collagen concentration modulates endothelial cell behavior. Acta Biomater 9: 4635–4644, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menck K, Bleckmann A, Wachter A, Hennies B, Ries L, Schulz M, Balkenhol M, Pukrop T, Schatlo B, Rost U, Wenzel D, Klemm F, Binder C. Characterisation of tumour-derived microvesicles in cancer patients’ blood and correlation with clinical outcome. J Extracell Vesicles 6: 1340745, 2017. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2017.1340745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishishita R, Morohashi S, Seino H, Wu Y, Yoshizawa T, Haga T, Saito K, Hakamada K, Fukuda S, Kijima H. Expression of cancer-associated fibroblast markers in advanced colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett 15: 6195–6202, 2018. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Otranto M, Sarrazy V, Bonté F, Hinz B, Gabbiani G, Desmoulière A. The role of the myofibroblast in tumor stroma remodeling. Cell Adhes Migr 6: 203–219, 2012. doi: 10.4161/cam.20377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paszek MJ, Zahir N, Johnson KR, Lakins JN, Rozenberg GI, Gefen A, Reinhart-King CA, Margulies SS, Dembo M, Boettiger D, Hammer DA, Weaver VM. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell 8: 241–254, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel S, Wetie AG, Darie CC, Clarkson BD. Cancer secretomes and their place in supplementing other hallmarks of cancer. In: Advancements of Mass Spectrometry in Biomedical Research, edited by Woods AG, Darie CC. New York: Springer International, p. 409–442. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peyton SR, Kim PD, Ghajar CM, Seliktar D, Putnam AJ. The effects of matrix stiffness and RhoA on the phenotypic plasticity of smooth muscle cells in a 3-D biosynthetic hydrogel system. Biomaterials 29: 2597–2607, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plodinec M, Loparic M, Monnier CA, Obermann EC, Zanetti-Dallenbach R, Oertle P, Hyotyla JT, Aebi U, Bentires-Alj M, Lim RY, Schoenenberger CA. The nanomechanical signature of breast cancer. Nat Nanotechnol 7: 757–765, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Provenzano PP, Eliceiri KW, Campbell JM, Inman DR, White JG, Keely PJ. Collagen reorganization at the tumor-stromal interface facilitates local invasion. BMC Med 4: 38, 2006. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-4-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med 19: 1423–1437, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nm.3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol 200: 373–383, 2013. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reinhart-King CA, Dembo M, Hammer DA. The dynamics and mechanics of endothelial cell spreading. Biophys J 89: 676–689, 2005. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.054320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rhee S. Fibroblasts in three dimensional matrices: cell migration and matrix remodeling. Exp Mol Med 41: 858–865, 2009. doi: 10.3858/emm.2009.41.12.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarker B, Singh R, Silva R, Roether JA, Kaschta J, Detsch R, Schubert DW, Cicha I, Boccaccini AR. Evaluation of fibroblasts adhesion and proliferation on alginate-gelatin crosslinked hydrogel. PLoS One 9: e107952, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwager SC, Taufalele PV, Reinhart-King CA. Cell–cell mechanical communication in cancer. Cell Mol Bioeng 12: 1–14, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s12195-018-00564-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shinde AV, Humeres C, Frangogiannis NG. The role of α-smooth muscle actin in fibroblast-mediated matrix contraction and remodeling. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 1863: 298–309, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Song YH, Warncke C, Choi SJ, Choi S, Chiou AE, Ling L, Liu HY, Daniel S, Antonyak MA, Cerione RA, Fischbach C. Breast cancer-derived extracellular vesicles stimulate myofibroblast differentiation and pro-angiogenic behavior of adipose stem cells. Matrix Biol 60-61: 190–205, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steenbeek SC, Pham TV, de Ligt J, Zomer A, Knol JC, Piersma SR, Schelfhorst T, Huisjes R, Schiffelers RM, Cuppen E, Jimenez CR, van Rheenen J. Cancer cells copy migratory behavior and exchange signaling networks via extracellular vesicles. EMBO J 37: e98357, 2018. doi: 10.15252/embj.201798357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stranford DM, Hung ME, Gargus ES, Shah RN, Leonard JN. A systematic evaluation of factors affecting extracellular vesicle uptake by breast cancer cells. Tissue Eng Part A 23: 1274–1282, 2017. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2017.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suetsugu A, Honma K, Saji S, Moriwaki H, Ochiya T, Hoffman RM. Imaging exosome transfer from breast cancer cells to stroma at metastatic sites in orthotopic nude-mouse models. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 65: 383–390, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sung BH, Ketova T, Hoshino D, Zijlstra A, Weaver AM. Directional cell movement through tissues is controlled by exosome secretion. Nat Commun 6: 7164, 2015. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sung BH, Weaver AM. Exosome secretion promotes chemotaxis of cancer cells. Cell Adhes Migr 11: 187–195, 2017. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2016.1273307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wakatsuki T, Wysolmerski RB, Elson EL. Mechanics of cell spreading: role of myosin II. J Cell Sci 116: 1617–1625, 2003. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Y, Gong T, Zhang ZR, Fu Y. Matrix stiffness differentially regulates cellular uptake behavior of nanoparticles in two breast cancer cell lines. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 9: 25915–25928, 2017. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b08751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Webber J, Steadman R, Mason MD, Tabi Z, Clayton A. Cancer exosomes trigger fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation. Cancer Res 70: 9621–9630, 2010. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yuan Y. Spatial heterogeneity in the tumor microenvironment. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 6: a026583, 2016. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang XH, Jin X, Malladi S, Zou Y, Wen YH, Brogi E, Smid M, Foekens JA, Massagué J. Selection of bone metastasis seeds by mesenchymal signals in the primary tumor stroma. Cell 154: 1060–1073, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]