Abstract

Objective

To determine any changes in total hospital revisits within 30 days of discharge after a hospital stay for medical conditions targeted by the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP).

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Hospital stays among Medicare patients for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia between 1 January 2012 and 1 October 2015.

Participants

Medicare fee-for-service patients aged 65 or over.

Main outcomes

Total hospital revisits within 30 days of discharge after hospital stays for medical conditions targeted by the HRRP, and by type of revisit: treat-and-discharge visit to an emergency department, observation stay (not leading to inpatient readmission), and inpatient readmission. Patient subgroups (age, sex, race) were also evaluated for each type of revisit.

Results

Our study cohort included 3 038 740 total index hospital stays from January 2012 to September 2015: 1 357 620 for heart failure, 634 795 for acute myocardial infarction, and 1 046 325 for pneumonia. Counting all revisits after discharge, the total number of hospital revisits per 100 patient discharges for target conditions increased across the study period (monthly increase 0.023 visits per 100 patient discharges (95% confidence interval 0.010 to 0.035)). This change was due to monthly increases in treat-and-discharge visits to an emergency department (0.023 (0.015 to 0.032) and observation stays (0.022 (0.020 to 0.025)), which were only partly offset by declines in readmissions (−0.023 (−0.035 to −0.012)). Increases in observation stay use were more pronounced among non-white patients than white patients. No significant change was seen in mortality within 30 days of discharge for target conditions (−0.0034 (−0.012 to 0.0054)).

Conclusions

In the United States, total hospital revisits within 30 days of discharge for conditions targeted by the HRRP increased across the study period. This increase was due to a rise in post-discharge emergency department visits and observation stays, which exceeded the decline in readmissions. Although reductions in readmissions have been attributed to improvements in discharge planning and care transitions, our findings suggest that these declines could instead be because hospitals and clinicians have intensified efforts to treat patients who return to a hospital within 30 days of discharge in emergency departments and as observation stays.

Introduction

Healthcare systems around the world are intensifying efforts to deliver higher value care. Reducing preventable hospital visits has drawn policy attention as an opportunity to improve quality of care and reduce healthcare spending in several countries, including the United States, England, Denmark, and Germany.1 In the US, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has implemented national initiatives that aim to push clinicians and hospitals to reduce readmissions for Medicare fee-for-service patients over the age of 65. In 2009, for example, CMS began publicly reporting 30 day readmission rates as a measure of hospital performance. One year later, the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) was established, mandating that CMS impose financial penalties on acute care hospitals in the US with higher than expected 30 day readmission rates after a hospital stay for common medical conditions. Penalties under the HRRP began in 2012 and are capped at 3% of Medicare payments to hospitals; 82% of hospitals were penalized in fiscal year 2019.2

Readmissions alone, however, do not capture the full spectrum of hospital revisits that can occur after discharge. A return visit to an emergency department, even if it does not result in an inpatient hospital stay, might also reflect inadequate care transitions or fragmented post-discharge care. In addition, observation stays, which are short hospital stays that are reimbursed differently from full inpatient hospital stays, are increasingly being used in the US as an alternative to inpatient hospital stays, and can occur in an emergency department, hospital observation unit, or a typical inpatient ward setting.3 However, neither of these encounters (emergency department or observation stays) are included as outcomes in the 30 day readmission measure used by CMS to evaluate hospital care quality under the HRRP.4

Understanding nationwide trends in total hospital based encounters (including treat-and-discharge visits to an emergency department, observation stays, or inpatient readmissions) within 30 days of discharge, for conditions targeted by the HRRP, is critically important from a policy perspective. A reduction in total revisits would suggest widespread improvements in discharge planning and transitions of care during hospital stays, as well as care coordination and quality in the post-discharge period, as intended by the HRRP. By contrast, if hospital revisits after discharge have not changed, or have increased, previously observed reductions in readmissions5 might simply reflect greater management of patients in emergency departments and observation units, and the readmission measure currently used by CMS could provide an incomplete picture of hospital performance. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to answer three policy relevant questions:

Have total hospital revisits within 30 days of discharge after a hospital stay for medical conditions targeted by the HRRP changed over time?

How have rates of treat-and-discharge visits to an emergency department, observation stays (not leading to readmission), and readmissions each contributed to changes in total hospital revisits?

Do these patterns differ if all 30 day post-discharge revisits per patient are counted, to provide a more comprehensive assessment of hospital use after discharge, rather than just the first revisit as done by CMS for the readmission measure?

Methods

Study cohort

We used Medicare Provider Analysis and Review files to identify index hospital stays at acute care hospitals from 1 January 2012 to 1 October 2015 with a principal discharge diagnosis of heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia—medical conditions targeted by the HRRP. We defined study cohorts using ICD-9-CM (international classification of diseases, 9th revision, clinical modification) codes used in the publicly reported CMS readmission and mortality measures. We included Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 or older who were alive at discharge, and excluded patients who were discharged against medical advice, were not enrolled in Medicare fee for service for at least 30 days after discharge (absent death), or were enrolled in Medicare fee for service for less than one year before hospital admission. Transfers to other hospitals were linked to one index hospital stay.6 Comorbidities were defined by hierarchical condition categories based on inpatient Medicare claims up to one year before hospital admission, and diagnosis codes per claim were limited to the first nine codes,7 as has been done in previous studies.5 6 8 9 We used outpatient claims files and previously described methods to identify observation stays10 as well as treat-and-discharge visits to an emergency department3 that occurred within 30 days of discharge after the index hospital stay.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was the trend in total hospital revisits within 30 days of discharge after a hospital stay for medical conditions targeted by the HRRP. We also evaluated revisits by type: treat-and-discharge visits to an emergency department, observation stays (not later leading to readmission), and readmissions. For each revisit, we used two different approaches: we counted only one revisit (the first event after discharge) for each type of encounter after the index hospital stay, as CMS does for the readmission measure4; and we counted all revisits within 30 days of discharge.

Statistical analysis

Logistic regression was used to fit a model for the outcome of the first post-discharge revisit among patients surviving up to discharge. We used a Poisson regression model for the outcome of all revisits. Models included reason for the index hospital stay (eg, heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia), demographics (age, sex, race), and clinical comorbidities as independent variables. After constructing separate models for each month (45 models for 45 months), we estimated the mean of the potential outcomes for each respective month using the demographics and clinical comorbidity profiles of patients admitted to hospital in 2014 as a reference, which was the most recent year that contained 12 calendar months of data. A smoothing spline was then fitted to the 45 data points to show temporal trends. A simple linear regression was also fitted to the 45 data points to estimate the monthly change for each type of revisit per 100 patient discharges. We then repeated this analysis to evaluate trends in revisits by patient subgroups. Additional details regarding the methodological approach and inferential strategy are provided in the supplement. Analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Institutional review board approval, including waiver of the requirement of participant informed consent because the data were deidentified, was provided by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in planning, design, or interpretation of the study. The study involved examination of existing claims data and no participants were recruited for this analysis. We intend to engage patients and health policymakers by disseminating this research through press releases, blog posts, and at research meetings. This research was done without patient involvement. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop patient relevant outcomes or interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document for readability or accuracy.

Results

Our study cohort included 3 038 740 total index hospital stays from January 2012 to September 2015: 1 357 620 for heart failure, 634 795 for acute myocardial infarction, and 1 046 325 for pneumonia. Baseline characteristics for all index hospital stays are shown in eTable 1. Over the study period, 840 114 hospital revisits within 30 days of discharge (counting only the first revisit of any type after discharge) occurred, including 265 055 treat-and-discharge visits to an emergency department, 80 083 observation stays, and 599 664 inpatient readmissions (counting only the first revisit for each type of encounter). After counting all revisits after the index hospital stays, we found 1 064 410 total hospital revisits, of which 303 194 were treat-and-discharge visits to an emergency department, 84 169 were observation stays, and 677 047 were readmissions (eTable 2).

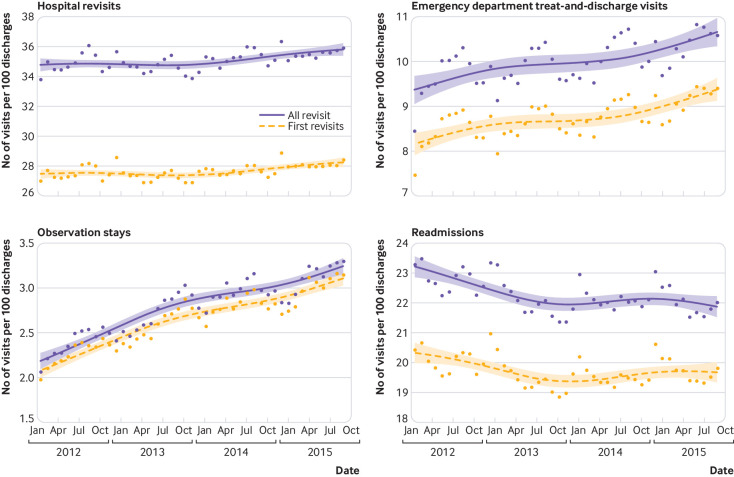

The number of first hospital revisits per 100 patient discharges for medical conditions targeted by the HRRP increased during the study (monthly change 0.016 revisits per 100 patient discharges (95% confidence interval 0.006 to 0.026); table 1). This change was driven by an increase in treat-and-discharge visits to an emergency department (0.022 (0.014 to 0.029)) and observation stays (0.022 (0.019 to 0.024)), which were only partly offset by reductions in inpatient readmissions (−0.013 (−0.023 to −0.002)).

Table 1.

Risk standardized monthly change in hospital revisits, treat-and-discharge visits to an emergency department, observation stays, and readmissions within 30 days of discharge for medical conditions targeted by the HRRP in the US

| Monthly change in No of revisits per 100 patient discharges (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| First revisit* | |

| Any hospital revisit | +0.016 (0.006 to 0.026) |

| Treat-and-discharge visit to emergency department | +0.022 (0.014 to 0.029) |

| Observation stay | +0.022 (0.019 to 0.024) |

| Readmission | −0.013 (−0.023 to −0.002) |

| All revisits† | |

| Any hospital revisit | +0.023 (0.010 to 0.035) |

| Treat-and-discharge visit to emergency department | +0.023 (0.015 to 0.032) |

| Observation stay | +0.022 (0.020 to 0.025) |

| Readmission | −0.023 (−0.035 to −0.012) |

Data based on Medicare fee-for-service patients aged 65 or over between 1 January 2012 and 1 October 2015. Target conditions include heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia.

Among patients with multiple hospital revisits within 30 days of discharge, only the first revisit for each type of encounter was counted.

Among patients with multiple hospital revisits within 30 days of discharge, all visits for each type of encounter were counted.

These changes became more pronounced after we counted all revisits per patient within 30 days of discharge. The monthly change in total hospital revisits per 100 patient discharges increased (0.023 (95% confidence interval 0.010 to 0.035)), due to a rise in treat-and-discharge visits to an emergency department (0.023 (0.015 to 0.032)) and observation stays (0.022 (0.020 to 0.025)), while readmissions decreased (−0.023 (–0.035 to −0.012)). Figure 1 shows spline fitted trends of hospital revisits across all target conditions, and eFigures 1-2 show trends by individual target condition.

Fig 1.

Risk standardized hospital revisits, treat-and-discharge visits to an emergency department, observation stays, and readmissions within 30 days of discharge for medical conditions targeted by the HRRP in the US. Spline fitted trends of hospital revisits are shown for all target conditions (heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia). Data based on Medicare fee-for-service patients aged 65 or over between 1 January 2012 and 1 October 2015. Yellow line=trends including only the first revisit for each type of encounter (eg, any hospital revisit, treat-and-discharge visit to an emergency department, observation stay, or inpatient readmission); purple line=trends including all revisits for each type of encounter

Patient subgroups (age, sex, and race) were also evaluated, as shown in table 2. Counting all revisits per patient, the monthly change in total hospital revisits per 100 patient discharges did not differ significantly among patients younger than 80 compared with patients aged 80 and over. Trends in treat-and-discharge visits to an emergency department, observation stays, and readmissions also did not differ between these age groups. In addition, we saw no significant difference in revisit trends among men compared to women. The monthly change in total hospital revisits and in treat-and-discharge visits to an emergency department were also similar among white patients compared with non-white patients. However, increases in observation stays within 30 days of discharge were more pronounced among non-white patients than white patients (monthly change 0.029 stays per 100 patient discharges (95% confidence interval 0.024 to 0.034) v 0.021 (0.018 to 0.024); P=0.006 for difference).

Table 2.

Risk standardized monthly change in hospital revisits, treat-and-discharge visits to an emergency department (ED), observation stays, and readmissions within 30 days of discharge for medical conditions targeted by the HRRP in the US, categorized by patient subgroups

| Patient characteristic | Monthly change in No of revisits per 100 patient discharges (95% CI) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparator group 1 | Comparator group 2 | ||

| Age (<80 v ≥80 years) | |||

| First revisit† | |||

| Any hospital revisit | +0.016 (0.007 to 0.027) | +0.015 (0.004 to 0.026) | 0.89 |

| ED treat-and-discharge visit | +0.024 (0.016 to 0.032) | +0.019 (0.012 to 0.027) | 0.36 |

| Observation stay | +0.023 (0.020 to 0.026) | +0.021 (0.018 to 0.023) | 0.30 |

| Readmission | −0.014 (−0.025 to −0.003) | −0.012 (−0.023 to 0.00) | 0.80 |

| All revisits‡ | |||

| Total hospital revisits | +0.030 (0.015 to 0.045) | +0.015 (0.012 to 0.028) | 0.08 |

| ED treat-and-discharge visit | +0.027 (0.017 to 0.037) | +0.020 (0.011 to 0.029) | 0.29 |

| Observation stay | +0.024 (0.021 to 0.027) | +0.020 (0.017 to 0.024) | 0.08 |

| Readmission | −0.021 (−0.034 to −0.009) | −0.026 (−0.038 to −0.014) | 0.56 |

| Sex (men v women) | |||

| First revisit† | |||

| Any hospital revisit | +0.016 (0.006 to 0.026) | +0.016 (0.005 to 0.027) | 1.00 |

| ED treat-and-discharge visit | +0.022 (0.015 to 0.029) | +0.021 (0.014 to 0.029) | 0.84 |

| Observation stay | +0.023 (0.021 to 0.025) | +0.020 (0.017 to 0.024) | 0.13 |

| Readmission | −0.013 (−0.025 to −0.001) | −0.012 (−0.023 to −0.002) | 0.90 |

| All revisits‡ | |||

| Total hospital revisits | +0.024 (0.012 to 0.037) | +0.021 (0.006 to 0.035) | 0.75 |

| ED treat-and-discharge visit | +0.024 (0.015 to 0.034) | +0.023 (0.013 to 0.032) | 0.88 |

| Observation stay | _+0.024 (0.022 to 0.027) | +0.021 (0.017 to 0.025) | 0.20 |

| Readmission | −0.024 (−0.037 to −0.012) | −0.023 (−0.034 to −0.011) | 0.91 |

| Race (white v non-white) | |||

| First revisit† | |||

| Any hospital revisit | +0.017 (0.008 to 0.027) | +0.009 (−0.005 to 0.023) | 0.36 |

| ED treat-and-discharge visit | +0.022 (0.015 to 0.029) | +0.020 (0.011 to 0.028) | 0.71 |

| Observation stay | +0.021 (0.018 to 0.023) | +0.027 (0.023 to 0.031) | 0.01 |

| Readmission | −0.011 (−0.022 to −0.001) | −0.021 (−0.035 to −0.007) | 0.26 |

| All revisits‡ | |||

| Total hospital revisits | +0.023 (0.011 to 0.035) | +0.021 (0.001 to 0.043) | 0.87 |

| ED treat-and-discharge visit | +0.023 (0.014 to 0.033) | +0.024 (0.013 to 0.035) | 0.89 |

| Observation stay | +0.021 (0.018 to 0.024) | +0.029 (0.024 to 0.034) | 0.006 |

| Readmission | −0.022 (−0.033 to −0.011) | −0.031 (−0.048 to −0.014) | 0.37 |

Data based on Medicare fee-for-service patients aged 65 or over between 1 January 2012 and 1 October 2015. Target conditions include heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia.

P value for difference in monthly change among subgroups.

Among patients with multiple hospital revisits within 30 days of discharge, only the first revisit for each type of encounter was counted.

Among patients with multiple hospital revisits within 30 days of discharge, all visits for each type of encounter were counted.

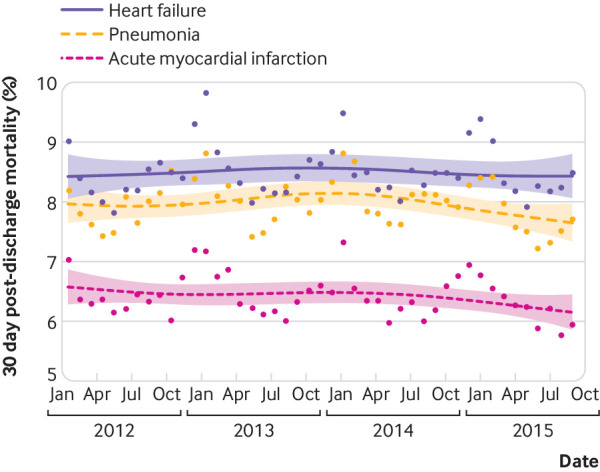

Overall, we observed no significant changes in mortality within 30 days of discharge across the three targeted conditions (−0.0034 (95% confidence interval −0.012 to 0.0054)) from 2012 to 2015. Post-discharge mortality at 30 days did not change among patients admitted to hospital for heart failure (0.00 (−0.011 to 0.010)), acute myocardial infarction (−0.006 (−0.015 to 0.002)), or pneumonia (−0.004 (−0.013 to 0.005); fig 2 and eTable 3).

Fig 2.

Risk standardized mortality within 30 days of discharge among Medicare patients admitted to hospital for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia (medical conditions targeted by the HRRP in the US). Spline fitted trends of mortality are shown, by target condition. Data based on Medicare fee-for-service patients aged 65 or over between 1 January 2012 and 1 October 2015

Discussion

In this study of Medicare beneficiaries admitted to hospital for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia in the US between 2012 and 2015, we found an increase in total hospital revisits within 30 days of discharge despite a reduction in 30 day readmissions. This increase was because of a rise in treat-and-discharge visits to an emergency department and observation stays within 30 days of discharge, which on national level, exceeded the decline in readmissions. Our finding of increased healthcare use during this period was more pronounced after we included all encounters within 30 days of discharge from the index hospital stay—rather than simply including the first revisit.

In the US, nationwide reductions in readmission rates for medical conditions targeted by the HRRP have been viewed as markers of improvements in quality of care. Our findings suggest that this success could be illusory because total hospital revisits after discharge are, in fact, rising. If reductions in readmissions were being driven by widespread improvements in discharge planning, care transitions and post-discharge care after a hospital stay (as intended by the HRRP), total hospital revisits within 30 days of discharge would also be expected to decline. Instead, much of the reduction in readmissions seems to reflect intensified efforts to manage patients who return to a hospital after discharge in observation units and emergency departments, potentially because the 30 day readmission measure used to evaluate hospital performance under the HRRP does not include these types of post-discharge encounters. These observations perhaps explain why previous studies have shown that inpatient quality of care delivered to patients admitted to hospital for heart failure or acute myocardial infarction do not differ at hospitals with high versus low readmission rates.11 12

The increase in use of observation stays and emergency department visits (compared with inpatient hospital stays) among patients who return after discharge could be a good thing if it reflects that patients are, on average, returning with lower severity illness that can be safely managed in a non-admission setting. These revisits could also be beneficial to patient care. For instance, observation stays have been associated with higher patient satisfaction than inpatient hospital stays,13 although they can also result in higher out-of-pocket expenditures and more financial hardship for patients than inpatient hospital stays.14 15

However, the increasing use of emergency department visits for post-discharge care could be problematic. Data have suggested that hospitals that tend to manage patients in emergency departments rather than admitting them for an inpatient stay have higher rates of early death after discharge.16 We observed no change in post-discharge mortality at 30 days for target conditions during the HRRP (from 2012 to 2015). However, several independent analyses have found that the implementation of the HRRP was associated with an increase in post-discharge mortality at 30 days among patients admitted for heart failure and pneumonia compared with pre-HRRP trends (pre-2010), and that this increase was concentrated entirely among patients not readmitted after discharge.6 17 18 19 Whether intensified efforts to manage returning patients in emergency departments and observation units explain increases in mortality observed in the years that preceded our study period is an important area for further research, given that this potential mechanism could explain increased mortality under the HRRP.20 21 22 23 24

Policy implications

Our findings have important policy implications for value based programs that use the 30 day readmission measure to evaluate hospital and provider care quality. Firstly, focusing on 30 day readmissions while ignoring other types of hospital revisits overestimates the clinical and financial benefits of incentives to reduce readmissions. Secondly, use of 30 day readmissions as the sole quality metric could impede fair comparisons of hospital performance, particularly given wide variation in triage patterns in emergency departments and the availability and use of observation units.25 Finally, given these limitations, the 30 day readmission rate seems to be an inappropriate target for financial incentives for hospitals (as used in the HRRP) or outpatient practices (as being increasingly used in pay-for-performance programs). Measuring all revisits within 30 days of discharge (that is, a “30 day return to hospital” metric) could instead provide a more comprehensive, accurate, and fair assessment of provider and hospital care quality.26

Several countries, including England, Germany, and Denmark, have implemented national level policies that aim to reduce readmissions, and others are actively considering similar initiatives.27 In England, incentives to reduce all cause readmissions were announced in 2010,28 and from fiscal years 2011-12, hospitals were no longer reimbursed for readmissions within 30 days of discharge exceeding a locally set threshold. However, the extent to which reductions in readmissions in England are due to improved quality of care during the index hospital stay, or instead, are due to greater management and treatment of patients who return after discharge in emergency departments is unknown. This area is important for future study, particularly given growing concern in the US that a focus on reducing readmissions could have adversely affected patients at the margin who would have benefited from inpatient level care.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Our study had limitations. We did not examine whether the increase in total hospital revisits, and emergency department visits and observation stays in particular, was associated with changes in patient satisfaction, or changes in Medicare spending and beneficiary out-of-pocket expenditures. We were also unable to evaluate whether greater shifts in emergency department and observation use occurred in the years before our study, when the HRRP was announced in 2010, and if this affected patient experience, quality of care, and mortality. This area remains important for future research given ongoing discussions regarding the potential unintended consequences of this program.21 22 23 26 29 30 31

Conclusions

Although readmissions for target conditions decreased from 2012 to 2015 in the US, total hospital revisits within 30 days of discharge steadily increased over that same period. This increase was due to a rise in treat-and-discharge encounters in emergency departments and observation stays, which on a national level, exceeded the decline in readmissions over the same period. Given that total hospital revisits are rising, nationwide reductions in readmissions could reflect intensified efforts to manage patients who return to a hospital after discharge to emergency departments and observation units rather than improvements in discharge planning and care transitions during index hospital stays, as intended by the HRRP. Future policy efforts in the US could benefit from measuring total hospital revisits within 30 days of discharge instead of solely focusing on readmissions, to strengthen incentives to improve quality of care and provide a more comprehensive assessment of care quality and healthcare use in the post-discharge period.

What is already known on this topic

Readmission rates at 30 days are increasingly used to measure quality of care and evaluate provider and hospital performance under value based payment programs in the United States

Readmission rates for medical conditions targeted by one such program, the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia), have declined modestly on a national scale

Policymakers have attributed these reductions to improved discharge planning, care transitions, and post-discharge care after index hospital stays, but these declines could be because clinicians and hospitals have increasingly adopted strategies to manage patients who return to a hospital within 30 days of discharge in emergency departments or as observation stays—which are not included in the current readmission measure

What this study adds

Total hospital revisits within 30 days of discharge after a hospital admission for target conditions have steadily increased under the HRRP, due to a rise in treat-and-discharge visits in an emergency department and observation stays

Although reductions in readmissions have been attributed to improvements in discharge planning and transitional care, as intended by the HRRP, these declines instead appear to be due to intensified efforts to manage patients who return within 30 days of discharge in emergency departments and observation units

A metric to measure patients’ 30 day return to hospital that captures all post-discharge encounters (inpatient, emergency department, and observation stays) could provide a more comprehensive, accurate, and fair assessment of hospital quality and performance

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: Supplemental material

Contributors: CS and RWY contributed equally as senior authors. All authors conceived and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. RWY acquired the data. CS and RKW carried out the statistical analysis. RKW, KEJM, and DSK drafted the manuscript. RWY, RKW, and CS supervised the study and are the guarantors. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted

Funding: This study received no support from any organization.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; RKW receives research support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1K23HL148525-1), and has previously served as consultant for Regeneron, outside the submitted work; KEJM receives research support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL143421), National Institute on Aging (R01AG060935), and Commonwealth Fund; RWY receives research support from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (R01HL136708) and the Richard A and Susan F Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology and received from Abiomed, personal fees from Asahi Intecc, grants from AstraZeneca, grants and personal fees from Boston Scientific, personal fees from Medtronic, and personal fees from Teleflex outside the submitted work; DSK receives research support from the Richard A and Susan F Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology; the other authors report no conflicts; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was reviewed and granted exemption by the institutional review board at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, including waiver of the requirement of participant informed consent because the data were deidentified.

Data sharing: No additional data are available due to data use agreement with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

The lead author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as originally planned have been explained.

References

- 1. Kristensen SR, Bech M, Quentin W. A roadmap for comparing readmission policies with application to Denmark, England, Germany and the United States. Health Policy 2015;119:264-73. . 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2019 https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html accessed February 12 2019.

- 3. Dharmarajan K, Qin L, Bierlein M, et al. Outcomes after observation stays among older adult Medicare beneficiaries in the USA: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2017;357:j2616. . 10.1136/bmj.j2616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.2017 Readmission Measures Updates and Specifications Report: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS); http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?cid=1228774371008&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier4&c=Page accessed February 2 2019.

- 5. Wasfy JH, Zigler CM, Choirat C, Wang Y, Dominici F, Yeh RW. Readmission rates after passage of the hospital readmissions reduction program: a pre-post analysis. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:324-31. . 10.7326/M16-0185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wadhera RK, Joynt Maddox KE, Wasfy JH, Haneuse S, Shen C, Yeh RW. Association of the hospital readmissions reduction program with mortality among medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia. JAMA 2018;320:2542-52. . 10.1001/jama.2018.19232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tsugawa Y, Figueroa JF, Papanicolas I, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Assessment of strategies for managing expansion of diagnosis coding using risk-adjustment methods for Medicare data. JAMA Intern Med 2019. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ody C, Msall L, Dafny LS, Grabowski DC, Cutler DM. Decreases in readmissions credited to Medicare’s program to reduce hospital readmissions have been overstated. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38:36-43. . 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ibrahim AM, Dimick JB, Sinha SS, Hollingsworth JM, Nuliyalu U, Ryan AM. Association of coded severity with readmission reduction after the hospital readmissions reduction program. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:290-2. . 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medicare Claims Processing ManualChapter 4 - Part B Hospital (Including Inpatient Hospital Part B and OPPS). 2019 https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c04.pdf accessed March 6 2019.

- 11. Pandey A, Golwala H, Hall HM, et al. Association of US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Hospital 30-day risk-standardized readmission metric with care quality and outcomes after acute myocardial infarction: findings from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry/Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network Registry-Get With the Guidelines. JAMA Cardiol 2017;2:723-31. . 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pandey A, Golwala H, Xu H, et al. Association of 30-day readmission metric for heart failure under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program with quality of care and outcomes. JACC Heart Fail 2016;4:935-46. . 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ross MA, Aurora T, Graff L, et al. State of the art: emergency department observation units. Crit Pathw Cardiol 2012;11:128-38. . 10.1097/HPC.0b013e31825def28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kangovi S, Cafardi SG, Smith RA, Kulkarni R, Grande D. Patient financial responsibility for observation care. J Hosp Med 2015;10:718-23. . 10.1002/jhm.2436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sheehy AM, Graf B, Gangireddy S, et al. Hospitalized but not admitted: characteristics of patients with “observation status” at an academic medical center. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1991-8. . 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.8185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Obermeyer Z, Cohn B, Wilson M, Jena AB, Cutler DM. Early death after discharge from emergency departments: analysis of national US insurance claims data. BMJ 2017;356:j239. . 10.1136/bmj.j239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gupta A, Allen LA, Bhatt DL, et al. Association of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program implementation with readmission and mortality outcomes in heart failure. JAMA Cardiol 2018;3:44-53. . 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.4265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huckfeldt P, Escarce J, Sood N, Yang Z, Popescu I, Nuckols T. Thirty-day postdischarge mortality among black and white patients 65 years and older in the Medicare Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e190634-34. . 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huckfeldt P, Escarce J, Wilcock A, et al. HF mortality trends under Medicare Readmissions Reduction Program at penalized and nonpenalized hospitals. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:2539-40. . 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.2174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jha AK. To fix the Hospital Readmissions Program, prioritize what matters. JAMA 2018;319:431-3. . 10.1001/jama.2017.21623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Joynt KE, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmissions--truth and consequences. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1366-9. . 10.1056/NEJMp1201598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fonarow GC, Konstam MA, Yancy CW. The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program is associated with fewer readmissions, more deaths: time to reconsider. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1931-4. . 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gupta A, Fonarow GC. The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program-learning from failure of a healthcare policy. Eur J Heart Fail 2018;20:1169-74. . 10.1002/ejhf.1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gupta A, Fonarow GC. The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program: Evidence for Harm. JACC Heart Fail 2018;6:607-9. . 10.1016/j.jchf.2018.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Venkatesh AK, Wang C, Ross JS, et al. Hospital use of observation stays: cross-sectional study of the impact on readmission rates. Med Care 2016;54:1070-7. . 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wadhera RK, Yeh RW, Joynt Maddox KE. The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program - time for a reboot. N Engl J Med 2019;380:2289-91. . 10.1056/NEJMp1901225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pricing framework for Australian public hospital services 2018-19: Independent Hospital Pricing Authority; 2017 https://www.ihpa.gov.au/sites/g/files/net4186/f/publications/pricing_framework_for_australian_public_hospital_services_2018-19.pdf accessed March 2019.

- 28.Equity and excellence: liberating the NHS: Department of Health; 2010 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213823/dh_117794.pdf accessed March 2019.

- 29. Wadhera RK, Bhatt DL. Toward precision policy - the case of cardiovascular care. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2193-5. . 10.1056/NEJMp1806260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fonarow GC. Unintended harm associated with the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA 2018;320:2539-41. . 10.1001/jama.2018.19325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jha AK. Seeking rational approaches to fixing hospital readmissions. JAMA 2015;314:1681-2. . 10.1001/jama.2015.13254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Supplemental material