Abstract

Salmonella species can infect a diverse range of birds, reptiles, and mammals, including humans. The type III protein secretion system (T3SS) encoded by Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1) delivers effector proteins required for intestinal invasion and the production of enteritis. The T3SS is regarded as the most important virulence factor of Salmonella. SPI-1 encodes transcription factors that regulate the expression of some virulence factors of Salmonella, while other transcription factors encoded outside SPI-1 participate in the expression of SPI-1-encoded genes. SPI-1 genes are responsible for the invasion of host cells, regulation of the host immune response, e.g., the host inflammatory response, immune cell recruitment and apoptosis, and biofilm formation. The regulatory network of SPI-1 is very complex and crucial. Here, we review the function, effectors, and regulation of SPI-1 genes and their contribution to the pathogenicity of Salmonella.

Keywords: Salmonella, SPI-1, T3SS, effector, regulation, immune response

Introduction

The gram-negative bacterial genus Salmonella contains as many as six subspecies and more than 2,600 serovars, including numerous serovars pathogenic to humans and a variety of animals (LeLièvre et al., 2019). Salmonellosis, the most frequent foodborne disease in humans, usually results from contaminated water and food. Typhoid fever, caused by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi infection, is still a major health problem, especially in the developing world with substandard water supplies and poor sanitation (Parry et al., 2002; Wain et al., 2015). Better characterization of Salmonella has become a hotspot issue. Pathogenic Salmonella species invade non-phagocytic intestinal epithelial cells by delivering a specialized set of effectors through sophisticated machinery comprising the type 3 secretion system (T3SS), which plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of Salmonella (Que et al., 2013). Salmonella employs two T3SSs encoded by Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1) and Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI-2). SPI-1 is a gene cluster and consists of a 40-kb region, which includes 39 genes encoding T3SS-1 and its chaperones and effector proteins as well as some transcriptional regulators that control the expression of many virulence genes located within and outside SPI-1 (Hansen-Wester and Hensel, 2001; Zhang K. et al., 2018). T3SS-1 of Salmonella can affect the phenotype, polarization and function of macrophages (Kyrova et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2018). The ubiquity of SPI-1 is conserved and required for Salmonella virulence, demonstrated by its active role in the entry process. Further studies have revealed that the SPI-1-encoded T3SS has additional functions and that its regulatory network is very complex. This review focuses on the effect and the regulation of SPI-1 and the relationship between host immunology and SPI-1 in Salmonella.

The Role of SPI-1

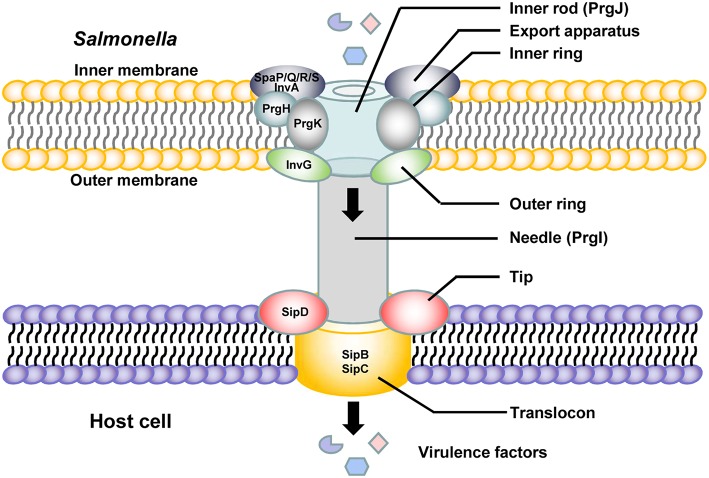

Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1) plays a crucial role in the interaction between Salmonella and host cells. SPI-1 promotes Salmonella invasion into epithelial cells (Raffatellu et al., 2005). The T3SS is assembled from the proteins encoded by SPI-1 and is termed the needle complex. Translocases and effector proteins are delivered into host cells through the needle complex. The needle complex spans the bacterial envelope, and a needle-like extension protrudes from the bacterial inner and outer membranes to the host cell membranes (Kubori et al., 1998; Sukhan et al., 2001). There are several highly conserved proteins and an ATPase in the needle complex, and all of them are essential for secretion (Figure 1). A sorting platform determines the order of protein secretion in the SPI-1 T3SS of Salmonella. The sorting platform consists of five proteins, SpaO, OrgA, OrgB, InvI, and the hexameric ATPase InvC, in Salmonella. Type III secretion chaperones are required for loading effectors and translocases onto the sorting platform (Lara-Tejero et al., 2011). The needle complex is composed of a multiple-ring cylindrical base. The needle complex base is initiated at the export apparatus, which is composed of the proteins InvA, SpaP, SpaQ, SpaR, and SpaS (Cornelis, 2006; Galán and Wolf-Watz, 2006; Minamino et al., 2008; Worrall et al., 2010). The export apparatus is essential to the assembly and/or the stability of the needle complex base (Wagner et al., 2010). Three proteins, InvG, which comprises the outer rings; PrgH, and PrgK, which are thought to form the rest of the structure, constitute the base with equimolar amounts. PrgI is the main component of the needle portion (Kubori et al., 2000; Marlovits et al., 2004; Schraidt et al., 2010). The length of the needle segment is controlled by the protein InvJ (Kubori et al., 2000). PrgJ forms an inner rod within the basal body and the needle is anchored by that inner rod, which forms a conduit between the bacterial cytoplasm and the host cell membrane (Galán and Wolf-Watz, 2006). The needle tip structure is capped with SipD, which is secreted by a nascent T3SS filament. The tip protein SipD is stably bound at the tip of the needle formed by a polymer of the protein PrgI. The needle tip complex regulates the secretion of effectors from Salmonella into the host cell (Lunelli et al., 2011). Upon host cell contact, the protein SipD forms a platform for the translocon composed of the transmembrane proteins SipB and SipC and interacts with their N-terminal ectodomains (Lara-Tejero and Galán, 2009; Kaur et al., 2016; Glasgow et al., 2017). SipB is a Salmonella translocon protein that is inserted into host membranes to form a channel associated with SipD at the needle tip, through which T3SS effectors are translocated into the host cell (Myeni et al., 2013; McShan et al., 2016). These translocons, encoded by Salmonella SPI-1, play an important role in both Salmonella contact with and invasion of host cells and the colonization of mammalian intestinal epithelial cells (Knodler and Steele-Mortimer, 2003; Boyen et al., 2006; Sivula et al., 2008; Lara-Tejero and Galán, 2009).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the SPI-1-related T3SS needle apparatus in contact with a host cell.

The SPI-1-encoded proteins are also required for the complex immune responses of host cells during Salmonella infection. Salmonella SPI-1 induces neutrophil recruitment during enteric colitis, leading to a reduction and alteration in intestinal microbiota (Sekirov et al., 2010). The SPI-1-encoded T3SS is required not only for cell invasion but also for suppression of early proinflammatory cytokine expression in macrophages, including that of IL-1β, IL-8, TNF-α, IL-23α, GM-CSF, and IL-18 (Pavlova et al., 2011). SPI-1 is involved in MHC-II downregulation and polarization to the M2 phenotype in macrophages (Kyrova et al., 2012; Van Parys et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2018). Salmonella can cross the blood-brain barrier and reach various brain tissues because the SPI-1 and outer membrane protein A genes of Salmonella increase penetration of the blood-brain barrier (Chaudhuri et al., 2018).

The Effector Proteins of the SPI-1 T3SS

Many gram-negative bacterial pathogens use a T3SS to inject their own proteins, termed effectors, into host cells to modulate some cellular functions (Hueck, 1998). Many SPI-1 effector proteins have been identified in Salmonella. These effectors play a variety of roles during Salmonella infection, including taking part in rearrangement of the host cytoskeleton, immune cell recruitment, cell metabolism, fluid secretion, and regulation of the host inflammatory response (Collier-Hyams et al., 2002; Brawn et al., 2007; Myeni et al., 2013). Several SPI-1 translocated effectors are responsible for the invasion of epithelial cells (Fu and Galán, 1999; Hayward and Koronakis, 1999; Mirold et al., 2001a,b). Salmonella expresses different SPI-1 effectors when colonizing specific tissues. The level and timing of the expression of these proteins determine the consequences of Salmonella infection and might be essential for tissue-specific aspects of its pathogenesis (Gong et al., 2009, 2010). The differential stability of some effector proteins (SopE and SptP) is central to the regulation of the activity of bacterial effectors within host cells (Kubori and Galán, 2003). We describe some of the effector proteins of SPI-1 T3SS and their functions below.

(1) AvrA

The virulence-associated gene avrA is located within SPI-1 and exists in most Salmonella strains (Amavisit et al., 2003). AvrA is a multifunctional enzyme and plays a critical role in inhibiting activation of the key proinflammatory NF-κB transcription factor and apoptosis via the JNK pathway (Collier-Hyams et al., 2002; Jones et al., 2008; Liao et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2012). It is phosphorylated in mammalian cells, and its phosphorylation requires the extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway (Du and Galán, 2009). AvrA promotes intestinal epithelial cell proliferation (Ye et al., 2007) and tumorigenesis (Lu et al., 2010) by blocking the degradation of IκBα and β-catenin. It enhances the development of infection-associated colon cancer by activating the STAT3 signaling pathway (Lu et al., 2016). AvrA expression in Salmonella stabilizes the structure and influences the function of tight junctions of intestinal epithelial cells via the JNK pathway, while its expression increases bacterial invasion ability and translocation (Liao et al., 2008; Lu et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2016).

(2) Sips

There are four Salmonella invasion proteins (Sips), namely, Sips A–D. These Sips are exported and translocated into the host cell plasma membrane or cytosol and play essential and complex roles in the secretion and translocation of SPI-1 effectors. SipA is an actin-binding protein and enhances the efficiency of the entry process of Salmonella into host cells by influencing different stages in the formation of membrane ruffles and rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton (Zhou et al., 1999). SipA regulates the concentration, polymerization and stability of the actin molecules at the site of bacterial entry and increases the bundling activity of host cell fimbrin (Galan and Zhou, 2000; McGhie et al., 2001, 2004). SipA is not essential for uptake, but it enhances the efficiency of the entry process (Zhou et al., 1999). SipA is exposed on the cytoplasmic face of the Salmonella-containing vacuole (SCV) after Salmonella internalization in both non-phagocytic cells and macrophages, and it is involved in the regulation of phagosome maturation and intracellular Salmonella replication (Brawn et al., 2007). The N-terminal domain of SipA induces polymorphonuclear leukocyte recruitment (Lee et al., 2000; Wall et al., 2007). SipA causes the activation and release of caspase-3, which plays multiple roles in the immune response of host cells, including in apoptosis, differentiation, proliferation, immunomodulation, immune cell migration, and signal transduction (Srikanth et al., 2010; McIntosh et al., 2017). SipB, SipC, and SipD are translocon proteins that participate in the formation of the SPI-1 T3SS needle complex (Figure 1; Zierler and Galán, 1995; Collazo and Galán, 1997; Scherer et al., 2000; Myeni and Zhou, 2010; Myeni et al., 2013). SipB is necessary for Salmonella-induced caspase-1-dependent apoptosis and the release of IL-18 (Hersh et al., 1999; Dreher et al., 2002; Obregon et al., 2003). SipC is a Salmonella translocon protein that targets F-actin, which is necessary for pathogen internalization (Kaniga et al., 1995) and promotes Salmonella invasion. Antibodies against SipD inhibit Salmonella invasion, and SipD might be a potential target for blocking SPI-1-mediated virulence (Desin et al., 2010). The N-terminal domain of SipD promotes the secretion of effectors and functions at the post-transcriptional and post-translational levels (Glasgow et al., 2017).

(3) SptP

Salmonella protein tyrosine phosphatase (SptP) was identified in 1996. The translocation of SptP to host cells results in the disruption of the cellular actin cytoskeleton (Kaniga et al., 1996; Fu and Galán, 1998a). However, SptP is directly responsible for the reversal of the actin cytoskeletal changes induced by other effectors of Salmonella via regulating villin phosphorylation (Fu and Galán, 1999; Lhocine et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2017). SptP translocation occurs during entry, when it downregulates membrane ruffling and then downmodulates ERK and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation and the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines induced by Salmonella entry (Kubori and Galán, 2003; Lin et al., 2003; Eswarappa et al., 2008; Button and Galán, 2011; Johnson et al., 2017). Protein SicP, which is immediately upstream of SptP, acts as a chaperone for SptP. Coupling of their translation is required for maximally efficient secretion of SptP (Fu and Galán, 1998b; Zhou and Galán, 2001; Button and Galán, 2011). SptP-mediated dephosphorylation of valosin-containing protein promotes Salmonella intracellular replication (Humphreys et al., 2009). SptP suppresses the degranulation and activation of mast cells, which enables bacterial dissemination. It is a powerful mechanism utilized by Salmonella to impede early innate immunity (Choi et al., 2013; Kawakami and Ando, 2013).

(4) Sops

The Salmonella outer proteins (Sops) are effector proteins that consist of SopA, SopB, SopD, SopD2, SopE, and SopE2. Sops are involved in the control of different stages of polymorphonuclear leukocyte influx and rearrangement of the cytoskeleton (Wood et al., 1996, 2000; Galyov et al., 1997; Jones et al., 1998; Bakshi et al., 2000; Boyle et al., 2006; Schlumberger and Hardt, 2006), contribute to Salmonella invasion and are responsible for inducing inflammation and diarrhea (Wood et al., 2000; Raffatellu et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2005). sopA, sopB, and sopE are regulated cooperatively by HilA and InvF (Thijs et al., 2007).

SopA can induce fluid secretion and the inflammatory response in Salmonella-infected intestines after being translocated into host cells (Wood et al., 2000). The stability and translocation of SopA requires the chaperone InvB (Ehrbar et al., 2004). Efficient bacterial escape from the SCV to the cytosol of epithelial cells requires HsRMA1-mediated SopA ubiquitination and contributes to Salmonella-induced enteropathogenicity. HsRMA1 is a membrane-bound ubiquitin E3 ligase, although SopA is an E3 ligase itself (Zhang et al., 2005, 2006). SopA regulates innate immune responses by mediating the ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of tripartite-motif containing (TRIM) E3 ligases (TRIM56 and TRIM65) (Kamanova et al., 2016; Fiskin et al., 2017).

SopB/SigD, an inositol phosphatase, is required for fluid and chloride secretion and neutrophil recruitment (Norris et al., 1998; Bertelsen et al., 2004). It mediates virulence by interdicting inositol phosphate signaling pathways and inducing Akt activation (Norris et al., 1998; Steele-Mortimer et al., 2000; Marcus et al., 2001). SopB/SigD also has antiapoptotic activity and is related to intracellular replication because of the sustainment of Akt activation (Knodler et al., 2005; Rodríguez-Escudero et al., 2011; García-Gil et al., 2018). SopB/SigD promotes membrane fission and damage to epithelial barrier function during invasion (Marcus et al., 2002; Terebiznik et al., 2002; Bertelsen et al., 2004). It stimulates nitric oxide (NO) production (Drecktrah et al., 2005).

SopD affects multiple signals and protein interactions and contributes to the systemic virulence of Salmonella and the development of gastroenteritis (Galyov et al., 1997; Jones et al., 1998; Galan and Zhou, 2000; Boonyom et al., 2010). It is involved in membrane fission and macropinosome formation during Salmonella invasion, with cooperation from SopB (Bakowski et al., 2007). SopD and SopD2 promote bacterial replication in host cells and are related to the SCV (Jiang et al., 2004; Bakowski et al., 2007; Maserati et al., 2017). SopD2 contributes to Salmonella-induced filament formation (Jiang et al., 2004) and inhibits the vesicular transport and tubule formation that extend outward from the SCV (Schroeder et al., 2010).

SopE, a Rho GTPase exchange factor, induces rapid actin cytoskeleton rearrangements, membrane ruffling, and consequent pathogen macropinocytosis and promotes bacterial invasion (Wood et al., 1996; Hardt et al., 1998; Rudolph et al., 1999; Galán and Fu, 2000; Mirold et al., 2001b; Humphreys et al., 2012; Lim et al., 2014). SopE transiently localizes to the early SCV and contributes to intracellular replication (Vonaesch et al., 2014). SopE2, which is homologous to SopE, has similar mechanisms of action to those of SopE (Bakshi et al., 2000; Stender et al., 2000; Friebel et al., 2001; Mirold et al., 2001a; Schlumberger and Hardt, 2006). SopE is rapidly degraded by a proteasome-mediated pathway, whereas SptP is slowly degraded, which inactivates Cdc42 and Rac1 and thereby reverses SopB-, SopE-, and SopE2-signaling (Fu and Galán, 1999; Kubori and Galán, 2003; Van Engelenburg and Palmer, 2008; Vonaesch et al., 2014). SopE induces the host to produce nitric oxide synthetase (iNOS) in the intestine, leading to intestinal inflammation (Bliska and van der Velden, 2012).

The Regulation of SPI-1

Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1) plays a crucial role not only in the colonization and invasion of Salmonella in the gut but also in the induction of neutrophil recruitment (Boyen et al., 2006). The regulation of the process involves many environmental stimuli and genetic regulators in complex networks (Figure 2). Several transcriptional regulators (e.g., HilA, HilC, HilD, and InvF) are encoded by SPI-1. Induction of SPI-1 requires the expression of invF and hilA because they are transcriptional activators of SPI-1 genes (Altier, 2005; Jones, 2005; Ellermeier and Slauch, 2007). The feed-forward regulatory loop of HilC–RtsA–HilD is the most important core part of the regulatory networks to control the transcription of hilA, while HilA is the central regulator of SPI-1 (Ellermeier et al., 2005; Dieye et al., 2007). HilA directly activates the expression of two SPI-1 genes (invF and sicA) that encode SPI-1 T3SS apparatus components. InvF, a transcriptional activator of the AraC family, activates the expression of SPI-1 T3SS effectors encoded both inside and outside of SPI-1 (Darwin and Miller, 1999; Eichelberg and Galán, 1999). The activity of InvF requires SicA, which is also encoded within SPI-1 (Darwin and Miller, 2000, 2001). Each activator among HilC, RtsA, and HilD can bind to the hilA promoter to activate the expression of hilA, and HilA can also induce its own expression significantly as well as activate the other two regulators (Schechter and Lee, 2001; Boddicker et al., 2003; Ellermeier et al., 2005). Furthermore, they can activate the expression of invF in a HilA-independent manner (Akbar et al., 2003; Baxter et al., 2003). HilE is the most important negative regulator of hilA expression. HilE represses the SPI-1 genes by binding to HilD, thus inactivating HilD and preventing the activation of HilA (Paredes-Amaya et al., 2018). Many other regulators can influence SPI-1 through interacting with the core network. Mlc, a global regulator of carbohydrate metabolism, controls several genes related to sugar utilization. Mlc downregulates hilE expression by binding to the hilE P3 promoter (Lim et al., 2007). SirA, a member of the phosphorylated response regulator protein family, positively regulates the HilD–HilC–RtsA–HilA network by activating HilA, HilC, or HilD (Behlau and Miller, 1993; Johnston et al., 1996; Teplitski et al., 2003; Ellermeier and Slauch, 2007). The action of BarA is coupled to SirA. In many studies, BarA/SirA is regarded as a two-component regulator that activates hilA expression and can also activate the invF gene without HilA involvement (Johnston et al., 1996; Rakeman et al., 1999; Altier et al., 2000; Teplitski et al., 2003). CsrA, a global regulatory RNA-binding protein, post-transcriptionally downregulates hilD expression by binding near the translation initiation codon sequences of the hilD mRNA directly, preventing HilD translation and leading to hilD mRNA turnover (Lucchetti-Miganeh et al., 2008; Martínez et al., 2011). The negative regulation is counteracted by the BarA/SirA two-component system, which directly activates the expression of csrB/C, two non-coding regulatory RNAs that sequester CsrA, thereby preventing CsrA from binding to its target mRNAs (Teplitski et al., 2003; Timmermans and Van Melderen, 2010; Martínez et al., 2011, 2014; Potts et al., 2019). H-NS is an abundant DNA-binding protein found in enteric bacteria, including Salmonella (Marsh and Hillyard, 1990; Owen-Hughes et al., 1992). H-NS inhibits the core positive regulators of SPI-1, including HilA, HilD, and RtsA, thus inhibiting the expression of SPI-1 as well as that of many other A + T-rich genes or ancestral DNA (Van Velkinburgh and Gunn, 1999; Lucchini et al., 2006; Navarre et al., 2006). The repression effect on rtsA is the most efficient among them. HilD, HilC, and RtsA bind to a common site in the rtsA promoter and antagonize H-NS-mediated repression (Schechter et al., 2003; Olekhnovich and Kadner, 2007). Interestingly, H-NS also represses the promoters of leuO and hilE, which are regarded as negative regulatory genes. HilE downregulates the expression of SPI-1 by directly inactivating HilD (Baxter et al., 2003). LeuO, a LysR-type transcriptional regulator, has been identified as a Salmonella virulence factor through genetic screening (Tenor et al., 2004; Lawley et al., 2006). The regulatory effect of LeuO is concentration-dependent (Dillon et al., 2012; Hernández-Lucas and Calva, 2012). LeuO is regarded as a transcriptional antagonist of H-NS because some genes repressed by H-NS can be activated by LeuO (Hernández-Lucas et al., 2008; Shimada et al., 2009). LeuO inhibits the expression of SPI-1 mainly by directly activating the promoter of hilE and via an unknown HilE-independent mechanism (Espinosa and Casadesús, 2014). However, LeuO has also been suggested to play a backup role for H-NS. The inhibitory effect of LeuO on SPI-1 genes may occur under growth conditions where H-NS does not perform such activity (Fahlen et al., 2000). FliZ, a flagellar regulator, can inhibit the expression of the type-1 fimbrial gene through post-transcriptional regulation of FimZ. FimZ is a regulator known to facilitate fimbrial protein expression and to repress the expression of flagellar genes (Saini et al., 2010). FliZ post-transcriptionally controls HilD to upregulate hilA expression (Chubiz et al., 2010). FimZ enhances the expression of hilE, which negatively regulates hilD. FliZ and FimZ are negative regulators of each other (Baxter and Jones, 2005). glnA, the glutamine synthetase gene, is essential for the growth and virulence of Salmonella because it upregulates FliZ, HilA, and HilD levels, improving the expression of SPI-1-associated effector genes, such as sopA, sopB, sopD, and invF (Aurass et al., 2018). The global regulatory system ArcAB promotes the expression of genes associated with the SPI-1 T3SS, such as invF, hilA, and sipC. It participates in Salmonella adaptation to changing oxygen levels. ArcAB is also involved in promoting bacterial intracellular survival (Lim et al., 2013; Pardo-Esté et al., 2018).

Figure 2.

Scheme of the SPI-1 regulatory network in Salmonella. The green arrows indicate activation, and the red lines with flat ends represent inhibition.

Because environmental changes, such as osmolarity, pH, and oxygen tension, influence the expression of hilA and because constitutive expression of hilA substantially frees invasion genes from the control of these environmental signals, it has been supposed that HilA plays a central role in the coordinated environmental regulatory effects of invasion genes (Bajaj et al., 1996). Bile, Mg2+ concentration and short-chain fatty acids can also regulate invasion (Altier, 2005). Bile is produced continuously by the liver and is involved in the digestion and absorption of fats. Bile is stored in the gall bladder at high concentrations prior to release into the intestines and serves as an important environmental cue to upregulate virulence gene expression during infection within the host gastrointestinal tract. Salmonella controls the production of virulence factors following bile exposure. The bile presents different regulatory effects on the SPI-1 T3SS between non-typhoidal and typhoidal Salmonella. The expression and activity of the S. Typhimurium SPI-1 T3SS are repressed by bile via BarA/SirA (Prouty and Gunn, 2000; Ellermeier and Slauch, 2007), while those of S. Typhi are increased by bile via prolonging the half-life of HilD and increasing SipC, SipD, SopB, and SopE expression (Johnson et al., 2018). Both phoPQ and phoBR, two-component systems, are very important regulators of hilA expression. These environmental signals could influence the expression and phosphorylation of fimZ. Under conditions of low Mg2+ concentration, the PhoPQ regulon is activated, leading to the phosphorylation of FimZ with a subsequent increase in hilE expression. Under conditions of low phosphate, PhoBR is activated, which increases fimZ expression, thus upregulating hilE expression (Baxter and Jones, 2015). The concentrations and composition of short-chain fatty acids regulate the SPI-1 T3SS via BarA/SirA (Lawhon et al., 2002). Propionate represses the SPI-1 T3SS by reducing the stability of HilD through post-translational modification (Hung et al., 2013). Lon protease, a negative regulator of SPI-1 genes, is important for the downregulation of hilA expression and intracellular survival after the invasion of epithelial cells through the degradation of HilC and HilD (Boddicker and Jones, 2004; Takaya et al., 2005). LoiA directly represses lon expression to activate the expression of SPI-1 genes (Jiang et al., 2017, 2019; Li et al., 2018). Salmonella can sense sugar availability by Mlc. The relatively high glucose concentration in the proximal small intestine can inhibit SPI-1 gene expression via Mlc, perhaps together with PhoBR and/or SirA (Agbor and McCormick, 2011). Lysophosphatidylcholine released following caspase-1 activation in Salmonella-infected cells promotes the expression of Sips and HilA and increases Salmonella invasion of host cells, and it is regarded as a key component of a novel regulatory mechanism for the regulation of cellular invasion with pathogenic Salmonella (Shivcharan et al., 2018).

Some small molecule compounds have been found to have an effect on the regulation of SPI-1. Dimethyl sulfide inhibits the expression of multiple SPI-1-related genes, including hilA, invA, sopA, sopB, and sopE2 (Antunes et al., 2010). L-arabinose, a plant-derived sugar, may serve as an inhibitory signal for SPI-1 of Salmonella by inhibiting the expression of hilD under certain circumstances (López-Garrido et al., 2015). Bifidobacterium thermophilum RBL67, a human fecal isolate, upregulates the expression of SPI-1-related genes of Salmonella, including sipB, sipD, prgI/H/K, invA/C/B/G/H, spaS/R/Q/P/O, and sicA/P. However, it also activates some genes located on SPI-2 and fimbrial genes, leading to redundant energy expenditure and protective activity against Salmonella infection (Tanner et al., 2016). Seaweed water extracts (Sarcodiotheca gaudichaudii and Chondrus crispus) can suppress expression of the SPI-1-associated genes hilA, sipA, and invF and may also impart beneficial effects on animal and human health (Kulshreshtha et al., 2016). Cytosporone B can decrease the expression of hilC, hilD, rtsA, hilA, sipA, and sipC. It regulates the transcription of SPI-1-related genes through the Hha–H-NS–HilD–HilC–RtsA–HilA regulatory pathway and has potential benefits in anti-Salmonella drug discovery (Li et al., 2013). Sanguinarine chloride, a natural compound, downregulates the transcription of HilA and consequently decreases the production of SipA and SipB. Sanguinarine chloride inhibits the invasion of host cells by Salmonella. It is a putative SPI-1 inhibitor and could be a promising anti-Salmonella compound (Zhang Y. et al., 2018). Methylthioadenosine reduces the virulence of Salmonella by suppressing the expression of invF and sipB (Bourgeois et al., 2018). Some kinds of prenylated flavonoids show a strong inhibitory effect on the secretion of SPI-1 effector proteins through regulating the transcription of sicA/invF and the transportation of the effector proteins SipA/B/C/D (Guo et al., 2016). Baicalein, a specific flavonoid from Scutellaria baicalensis, targets SPI-1 effectors and translocases to inhibit Salmonella invasion. It does not suppress SPI-1-related proteins directly but affects the assembly, stability, or activity of their substrates (Tsou et al., 2016). Quercetin, another naturally occurring flavonoid, can also antagonize SPI-1 T3SS substrates of Salmonella (Tsou et al., 2016). Biochanin a, a major isoflavone constituent found in red clover, cabbage, alfalfa, and some other herbal dietary supplements, suppresses the expression of sipA, sipB, sipC, hilA, and hilD and reverses macrophage polarization via downregulating SPI-1 expression (Zhao et al., 2018). Indole, a microbial metabolite of tryptophan, inhibits Salmonella invasion by decreasing SPI-1-related gene expression, including that of hilA, prgH, invF, and sipC, via both PhoPQ-dependent and -independent mechanisms (Kohli et al., 2018). These compounds and medicines may have immunomodulatory effects on Salmonella-infected host cells and regulate their bactericidal activity. They might be promising candidates for novel types of anti-Salmonella drugs.

Conclusion

The virulence-associated SPI-1 has been widely explored in interactions between Salmonella and its hosts. SPI-1 affects the whole process of salmonellosis, including pathogen invasion, proliferation, and host responses. Greater insights into SPI-1 and its complex regulatory network might contribute to drug investigation and Salmonella infection control.

Author Contributions

YW conceived the general idea. LL, PZ, and RP conducted the literature study and wrote the draft manuscript. YW provided critical revision and final approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81801972).

References

- Agbor T. A., McCormick B. A. (2011). Salmonella effectors: important players modulating host cell function during infection. Cell Microbiol. 13, 1858–1869. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01701.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbar S., Schechter L. M., Lostroh C. P., Lee C. A. (2003). AraC/XylS family members, HilD and HilC, directly activate virulence gene expression independently of HilA in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 47, 715–728. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03322.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altier C. (2005). Genetic and environmental control of Salmonella invasion. J. Microbiol. 43, 85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altier C., Suyemoto M., Ruiz A. I., Burnham K. D., Maurer R. (2000). Characterization of two novel regulatory genes affecting Salmonella invasion gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 35, 635–646. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01734.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amavisit P., Lightfoot D., Browning G. F., Markham P. F. (2003). Variation between pathogenic serovars within Salmonella pathogenicity islands. J. Bacteriol. 185, 3624–3635. 10.1128/JB.185.12.3624-3635.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes L. C., Buckner M. M., Auweter S. D., Ferreira R. B., Loli,ć P., Finlay B. B. (2010). Inhibition of Salmonella host cell invasion by dimethyl sulfide. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 5300–5304. 10.1128/AEM.00851-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurass P., Düvel J., Karste S., Nübel U., Rabsch W., Flieger A. (2018). glnA Truncation in Salmonella enterica results in a small colony variant phenotype, attenuated host cell entry, and reduced expression of flagellin and SPI-1-associated effector genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84:e01838–17. 10.1128/AEM.01838-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj V., Lucas R. L., Hwang C., Lee C. A. (1996). Coordinate regulation of S. typhimurium invasion genes by environmental and regulatory factors is mediated by control of hilA expression. Mol. Microbiol. 22, 703–714. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.d01-1718.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakowski M. A., Cirulis J. T., Brown N. F., Finlay B. B., Brumell J. H. (2007). SopD acts cooperatively with SopB during Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium invasion. Cell Microbiol. 9, 2839–2855. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01000.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi C. S., Singh V. P., Wood M. W., Jones P. W., Wallis T. S., Galyov E. E. (2000). Identification of SopE2, a Salmonella secreted protein which is highly homologous to SopE and involved in bacterial invasion of epithelial cells. J. Bacteriol. 182, 2341–2344. 10.1128/JB.182.8.2341-2344.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter M. A., Fahlen T. F., Wilson R. L., Jones B. D. (2003). HilE interacts with HilD and negatively regulates hilA transcription and expression of the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium invasive phenotype. Infect. Immun. 71, 1295–1305. 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1295-1305.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter M. A., Jones B. D. (2005). The fimYZ genes regulate Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium invasion in addition to type 1 fimbrial expression and bacterial motility. Infect. Immun. 73, 1377–1385. 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1377-1385.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter M. A., Jones B. D. (2015). Two-component regulators control hilA expression by controlling fimZ and hilE expression within Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 83, 978–985. 10.1128/IAI.02506-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behlau I., Miller S. I. (1993). A PhoP-repressed gene promotes Salmonella typhimurium invasion of epithelial cells. J. Bacteriol. 175, 4475–4484. 10.1128/jb.175.14.4475-4484.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertelsen L. S., Paesold G., Marcus S. L., Finlay B. B., Eckmann L., Barrett K. E. (2004). Modulation of chloride secretory responses and barrier function of intestinal epithelial cells by the Salmonella effector protein SigD. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 287, C939–C948. 10.1152/ajpcell.00413.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliska J. B., van der Velden A. W. (2012). Salmonella “sops” up a preferred electron receptor in the inflamed intestine. MBio 3, e00226–e00212. 10.1128/mBio.00226-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddicker J. D., Jones B. D. (2004). Lon protease activity causes down-regulation of Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 invasion gene expression after infection of epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 72, 2002–2013. 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2002-2013.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddicker J. D., Knosp B. M., Jones B. D. (2003). Transcription of the Salmonella invasion gene activator, hilA, requires HilD activation in the absence of negative regulators. J. Bacteriol. 185, 525–533. 10.1128/JB.185.2.525-533.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonyom R., Karavolos M. H., Bulmer D. M., Khan C. M. (2010). Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1) type III secretion of SopD involves N- and C-terminal signals and direct binding to the InvC ATPase. Microbiology 156(Pt 6), 1805–1814. 10.1099/mic.0.038117-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois J. S., Zhou D., Thurston T. L. M., Gilchrist J. J., Ko D. C. (2018). Methylthioadenosine suppresses Salmonella virulence. Infect. Immun. 86:e00429–18. 10.1128/IAI.00429-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyen F., Pasmans F., Van Immerseel F., Morgan E., Adriaensen C., Hernalsteens J. P., et al. (2006). Salmonella typhimurium SPI-1 genes promote intestinal but not tonsillar colonization in pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 8, 2899–2907. 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle E. C., Brown N. F., Finlay B. B. (2006). Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium effectors SopB, SopE, SopE2, and SipA disrupt tight junction structure and function. Cell Microbiol. 8, 1946–1957. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00762.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawn L. C., Hayward R. D., Koronakis V. (2007). Salmonella SPI1 effector SipA persists after entry and cooperates with a SPI2 effector to regulate phagosome maturation and intracellular replication. Cell Host Microbe. 1, 63–75. 10.1016/j.chom.2007.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button J. E., Galán J. E. (2011). Regulation of chaperone/effector complex synthesis in a bacterial type III secretion system. Mol. Microbiol. 81, 1474–1483. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07784.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri D., Roy Chowdhury A., Biswas B., Chakravortty D. (2018). Salmonella typhimurium infection leads to colonization of the mouse brain and is not completely cured with antibiotics. Front. Microbiol. 9:1632 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H. W., Brooking-Dixon R., Neupane S., Lee C. J., Miao E. A., Staats H. F., et al. (2013). Salmonella typhimurium impedes innate immunity with a mast-cell-suppressing protein tyrosine phosphatase, SptP. Immunity 39, 1108–1120. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubiz J. E., Golubeva Y. A., Lin D., Miller L. D., Slauch J. M. (2010). FliZ regulates expression of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 invasion locus by controlling HilD protein activity in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 192, 6261–6270. 10.1128/JB.00635-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collazo C. M., Galán J. E. (1997). The invasion-associated type III system of Salmonella typhimurium directs the translocation of Sip proteins into the host cell. Mol. Microbiol. 24, 747–756. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3781740.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier-Hyams L. S., Zeng H., Sun J., Tomlinson A. D., Bao Z. Q., Chen H., et al. (2002). Cutting edge: Salmonella AvrA effector inhibits the key proinflammatory, anti-apoptotic NF-kappa B pathway. J. Immunol. 169, 2846–2850. 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.2846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelis G. R. (2006). The type III secretion injectisome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 811–825. 10.1038/nrmicro1526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin K. H., Miller V. L. (1999). InvF is required for expression of genes encoding proteins secreted by the SPI1 type III secretion apparatus in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 181, 4949–4954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin K. H., Miller V. L. (2000). The putative invasion protein chaperone SicA acts together with InvF to activate the expression of Salmonella typhimurium virulence genes. Mol. Microbiol. 35, 949–960. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01772.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin K. H., Miller V. L. (2001). Type III secretion chaperone-dependent regulation: activation of virulence genes by SicA and InvF in Salmonella typhimurium. EMBO J. 20, 1850–1862. 10.1093/emboj/20.8.1850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desin T. S., Mickael C. S., Lam P. K., Potter A. A., Köster W. (2010). Protection of epithelial cells from Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis invasion by antibodies against the SPI-1 type III secretion system. Can. J. Microbiol. 56, 522–526. 10.1139/w10-034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieye Y., Dyszel J. L., Kader R., Ahmer B. M. (2007). Systematic analysis of the regulation of type three secreted effectors in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. BMC Microbiol. 7:3. 10.1186/1471-2180-7-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon S. C., Espinosa E., Hokamp K., Ussery D. W., Casadesús J., Dorman C. J. (2012). LeuO is a global regulator of gene expression in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 85, 1072–1089. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08162.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drecktrah D., Knodler L. A., Galbraith K., Steele-Mortimer O. (2005). The Salmonella SPI1 effector SopB stimulates nitric oxide production long after invasion. Cell Microbiol. 7, 105–113. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00436.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreher D., Kok M., Obregon C., Kiama S. G., Gehr P., Nicod L. P. (2002). Salmonella virulence factor SipB induces activation and release of IL-18 in human dendritic cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 72, 743–751. 10.1189/jlb.72.4.743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du F., Galán J. E. (2009). Selective inhibition of type III secretion activated signaling by the Salmonella effector AvrA. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000595. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrbar K., Hapfelmeier S., Stecher B., Hardt W. D. (2004). InvB is required for type III-dependent secretion of SopA in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 186, 1215–1219. 10.1128/JB.186.4.1215-1219.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichelberg K., Galán J. E. (1999). Differential regulation of Salmonella typhimurium type III secreted proteins by pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1)-encoded transcriptional activators InvF and hilA. Infect. Immun. 67, 4099–4105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellermeier C. D., Ellermeier J. R., Slauch J. M. (2005). HilD, HilC and RtsA constitute a feed forward loop that controls expression of the SPI1 type three secretion system regulator hilA in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 57, 691–705. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04737.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellermeier J. R., Slauch J. M. (2007). Adaptation to the host environment: regulation of the SPI1 type III secretion system in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10, 24–29. 10.1016/j.mib.2006.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa E., Casadesús J. (2014). Regulation of Salmonella enterica pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1) by the LysR-type regulator LeuO. Mol. Microbiol. 91, 1057–1069. 10.1111/mmi.12500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eswarappa S. M., Janice J., Nagarajan A. G., Balasundaram S. V., Karnam G., Dixit N. M., et al. (2008). Differentially evolved genes of Salmonella pathogenicity islands: insights into the mechanism of host specificity in Salmonella. PLoS ONE 3:e3829. 10.1371/journal.pone.0003829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlen T. F., Mathur N., Jones B. D. (2000). Identification and characterization of mutants with increased expression of hilA, the invasion gene transcriptional activator of Salmonella typhimurium. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 28, 25–35. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2000.tb01453.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiskin E., Bhogaraju S., Herhaus L., Kalayil S., Hahn M., Dikic I. (2017). Structural basis for the recognition and degradation of host TRIM proteins by Salmonella effector SopA. Nat. Commun. 8:14004. 10.1038/ncomms14004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friebel A., Ilchmann H., Aepfelbacher M., Ehrbar K., Machleidt W., Hardt W. D. (2001). SopE and SopE2 from Salmonella typhimurium activate different sets of RhoGTPases of the host cell. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 34035–34040. 10.1074/jbc.M100609200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Galán J. E. (1998a). The Salmonella typhimurium tyrosine phosphatase SptP is translocated into host cells and disrupts the actin cytoskeleton. Mol. Microbiol. 27, 359–368. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00684.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Galán J. E. (1998b). Identification of a specific chaperone for SptP, a substrate of the centisome 63 type III secretion system of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 180, 3393–3399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Galán J. E. (1999). A Salmonella protein antagonizes Rac-1 and Cdc42 to mediate host-cell recovery after bacterial invasion. Nature 401, 293–297. 10.1038/45829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galán J. E., Fu Y. (2000). Modulation of actin cytoskeleton by Salmonella GTPase activating protein SptP. Methods Enzymol. 325, 496–504. 10.1016/S0076-6879(00)25469-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galán J. E., Wolf-Watz H. (2006). Protein delivery into eukaryotic cells by type III secretion machines. Nature 444, 567–573. 10.1038/nature05272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galan J. E., Zhou D. (2000). Striking a balance: modulation of the actin cytoskeleton by Salmonella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97, 8754–8761. 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galyov E. E., Wood M. W., Rosqvist R., Mullan P. B., Watson P. R., Hedges S., et al. (1997). A secreted effector protein of Salmonella dublin is translocated into eukaryotic cells and mediates inflammation and fluid secretion in infected ileal mucosa. Mol. Microbiol. 25, 903–912. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1997.mmi525.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Gil A., Galán-Enríquez C. S., Pérez-López A., Nava P., Alpuche-Aranda C., Ortiz-Navarrete V. (2018). SopB activates the Akt-YAP pathway to promote Salmonella survival within B cells. Virulence 9, 1390–1402. 10.1080/21505594.2018.1509664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow A. A., Wong H. T., Tullman-Ercek D. (2017). Secretion-amplification role for Salmonella enterica translocon protein SipD. ACS Synth. Biol. 6, 1006–1015. 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong H., Su J., Bai Y., Miao L., Kim K., Yang Y., et al. (2009). Characterization of the expression of Salmonella Type III secretion system factor PrgI, SipA, SipB, SopE2, SpaO, and SptP in cultures and in mice. BMC Microbiol. 9:73. 10.1186/1471-2180-9-73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong H., Vu G. P., Bai Y., Yang E., Liu F., Lu S. (2010). Differential expression of Salmonella type III secretion system factors InvJ, PrgJ, SipC, SipD, SopA and SopB in cultures and in mice. Microbiology 156(Pt 1), 116–127. 10.1099/mic.0.032318-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z., Li X., Li J., Yang X., Zhou Y., Lu C., et al. (2016). Licoflavonol is an inhibitor of the type three secretion system of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 477, 998–1004. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen-Wester I., Hensel M. (2001). Salmonella pathogenicity islands encoding type III secretion systems. Microbes. Infect. 3, 549–559. 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01411-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt W. D., Chen L. M., Schuebel K. E., Bustelo X. R., Galán J. E. (1998). S. typhimurium encodes an activator of Rho GTPases that induces membrane ruffling and nuclear responses in host cells. Cell 93, 815–826. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81442-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward R. D., Koronakis V. (1999). Direct nucleation and bundling of actin by the SipC protein of invasive Salmonella. EMBO J. 18, 4926–4934. 10.1093/emboj/18.18.4926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Lucas I., Calva E. (2012). The coming of age of the LeuO regulator. Mol. Microbiol. 85, 1026–1028. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08175.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Lucas I., Gallego-Hernández A. L., Encarnación S., Fernandez-Mora M., Martinez-Batallar A. G., Salgado H., et al. (2008). The LysR-type transcriptional regulator LeuO controls expression of several genes in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. J. Bacteriol. 190, 1658–1670. 10.1128/JB.01649-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh D., Monack D. M., Smith M. R., Ghori N., Falkow S., Zychlinsky A. (1999). The Salmonella invasin SipB induces macrophage apoptosis by binding to caspase-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96, 2396–2401. 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hueck C. J. (1998). Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62, 379–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys D., Davidson A., Hume P. J., Koronakis V. (2012). Salmonella virulence effector SopE and Host GEF ARNO cooperate to recruit and activate WAVE to trigger bacterial invasion. Cell Host Microbe 11, 129–139. 10.1016/j.chom.2012.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys D., Hume P. J., Koronakis V. (2009). The Salmonella effector SptP dephosphorylates host AAA+ ATPase VCP to promote development of its intracellular replicative niche. Cell Host Microbe 5, 225–233. 10.1016/j.chom.2009.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung C. C., Garner C. D., Slauch J. M., Dwyer Z. W., Lawhon S. D., Frye J. G., et al. (2013). The intestinal fatty acid propionate inhibits Salmonella invasion through the post-translational control of HilD. Mol. Microbiol. 87, 1045–1060. 10.1111/mmi.12149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L., Feng L., Yang B., Zhang W., Wang P., Jiang X., et al. (2017). Signal transduction pathway mediated by the novel regulator LoiA for low oxygen tension induced Salmonella Typhimurium invasion. PLoS Pathog. 13:e1006429. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L., Li X., Lv R., Feng L. (2019). LoiA directly represses lon gene expression to activate the expression of Salmonella pathogenicity island-1 genes. Res. Microbiol. 10.1016/j.resmic.2019.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Rossanese O. W., Brown N. F., Kujat-Choy S., Galán J. E., Finlay B. B., et al. (2004). The related effector proteins SopD and SopD2 from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium contribute to virulence during systemic infection of mice. Mol. Microbiol. 54, 1186–1198. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04344.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R., Byrne A., Berger C. N., Klemm E., Crepin V. F., Dougan G., et al. (2017). The Type III Secretion System Effector SptP of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhi. J. Bacteriol. 199:e00647–16. 10.1128/JB.00647-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R., Ravenhall M., Pickard D., Dougan G., Byrne A., Frankel G. (2018). Comparison of Salmonella enterica serovars typhi and typhimurium reveals typhoidal serovar-specific responses to Bile. Infect. Immun. 86:e00490–17. 10.1128/IAI.00490-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C., Pegues D. A., Hueck C. J., Lee A., Miller S. I. (1996). Transcriptional activation of Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes by a member of the phosphorylated response-regulator superfamily. Mol. Microbiol. 22, 715–727. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.d01-1719.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B. D. (2005). Salmonella invasion gene regulation: a story of environmental awareness. J. Microbiol. 43, 110–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M. A., Wood M. W., Mullan P. B., Watson P. R., Wallis T. S., Galyov E. E. (1998). Secreted effector proteins of Salmonella dublin act in concert to induce enteritis. Infect. Immun. 66, 5799–5804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. M., Wu H., Wentworth C., Luo L., Collier-Hyams L., Neish A. S. (2008). Salmonella AvrA coordinates suppression of host immune and apoptotic defenses via JNK pathway blockade. Cell Host Microbe 3, 233–244. 10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamanova J., Sun H., Lara-Tejero M., Galán J. E. (2016). The Salmonella effector protein SopA modulates innate immune responses by targeting TRIM E3 ligase family members. PLoS Pathog. 12:e1005552. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniga K., Tucker S., Trollinger D., Galán J. E. (1995). Homologs of the Shigella IpaB and IpaC invasins are required for Salmonella typhimurium entry into cultured epithelial cells. J. Bacteriol. 177, 3965–3971. 10.1128/jb.177.14.3965-3971.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniga K., Uralil J., Bliska J. B., Galán J. E. (1996). A secreted protein tyrosine phosphatase with modular effector domains in the bacterial pathogen Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 21, 633–641. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02571.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur K., Chatterjee S., De Guzman R. N. (2016). Characterization of the Shigella and Salmonella Type III secretion system tip-translocon protein-protein interaction by paramagnetic relaxation enhancement. Chembiochem 17, 745–752. 10.1002/cbic.201500556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami T., Ando T. (2013). Salmonella's masterful skill in mast cell suppression. Immunity 39, 996–998. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knodler L. A., Finlay B. B., Steele-Mortimer O. (2005). The Salmonella effector protein SopB protects epithelial cells from apoptosis by sustained activation of Akt. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 9058–9064. 10.1074/jbc.M412588200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knodler L. A., Steele-Mortimer O. (2003). Taking possession: biogenesis of the Salmonella-containing vacuole. Traffic 4, 587–599. 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00118.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli N., Crisp Z., Riordan R., Li M., Alaniz R. C., Jayaraman A. (2018). The microbiota metabolite indole inhibits Salmonella virulence: involvement of the PhoPQ two-component system. PLoS ONE 13:e0190613. 10.1371/journal.pone.0190613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubori T., Galán J. E. (2003). Temporal regulation of Salmonella virulence effector function by proteasome-dependent protein degradation. Cell 115, 333–342. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00849-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubori T., Matsushima Y., Nakamura D., Uralil J., Lara-Tejero M., Sukhan A., et al. (1998). Supramolecular structure of the Salmonella typhimurium type III protein secretion system. Science 280, 602–605. 10.1126/science.280.5363.602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubori T., Sukhan A., Aizawa S. I., Galán J. E. (2000). Molecular characterization and assembly of the needle complex of the Salmonella typhimurium type III protein secretion system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97, 10225–10230. 10.1073/pnas.170128997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulshreshtha G., Borza T., Rathgeber B., Stratton G. S., Thomas N. A., Critchley A., et al. (2016). Red seaweeds Sarcodiotheca gaudichaudii and Chondrus crispus down regulate virulence factors of Salmonella enteritidis and induce immune responses in Caenorhabditis elegans. Front. Microbiol. 7:421. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyrova K., Stepanova H., Rychlik I., Faldyna M., Volf J. (2012). SPI-1 encoded genes of Salmonella typhimurium influence differential polarization of porcine alveolar macrophages in vitro. BMC Vet. Res. 8:115. 10.1186/1746-6148-8-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Tejero M., Galán J. E. (2009). Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium pathogenicity island 1-encoded type III secretion system translocases mediate intimate attachment to nonphagocytic cells. Infect. Immun. 77, 2635–2642. 10.1128/IAI.00077-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Tejero M., Kato J., Wagner S., Liu X., Galán J. E. (2011). A sorting platform determines the order of protein secretion in bacterial type III systems. Science 331, 1188–1191. 10.1126/science.1201476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawhon S. D., Maurer R., Suyemoto M., Altier C. (2002). Intestinal short-chain fatty acids alter Salmonella typhimurium invasion gene expression and virulence through BarA/SirA. Mol. Microbiol. 46, 1451–1464. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03268.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawley T. D., Chan K., Thompson L. J., Kim C. C., Govoni G. R., Monack D. M. (2006). Genome-wide screen for Salmonella genes required for long-term systemic infection of the mouse. PLoS Pathog. 2:e11. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. A., Silva M., Siber A. M., Kelly A. J., Galyov E., McCormick B. A. (2000). A secreted Salmonella protein induces a proinflammatory response in epithelial cells, which promotes neutrophil migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97, 12283–12288. 10.1073/pnas.97.22.12283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeLièvre V., Besnard A., Schlusselhuber M., Desmasures N., Dalmasso M. (2019). Phages for biocontrol in foods: What opportunities for Salmonella sp. control along the dairy food chain? Food Microbiol. 78, 89–98. 10.1016/j.fm.2018.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lhocine N., Arena E. T., Bomme P., Ubelmann F., Prévost M. C., Robine S., et al. (2015). Apical invasion of intestinal epithelial cells by Salmonella typhimurium requires villin to remodel the brush border actin cytoskeleton. Cell Host Microbe. 17, 164–177. 10.1016/j.chom.2014.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Li X., Lv R., Jiang X., Cao H., Du Y., et al. (2018). Global regulatory function of the low oxygen-induced transcriptional regulator LoiA in Salmonella Typhimurium revealed by RNA sequencing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 503, 2022–2027. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.07.151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Lv C., Sun W., Li Z., Han X., Li Y., et al. (2013). Cytosporone B, an inhibitor of the type III secretion system of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 2191–2198. 10.1128/AAC.02421-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao A. P., Petrof E. O., Kuppireddi S., Zhao Y., Xia Y., Claud E. C., et al. (2008). Salmonella type III effector AvrA stabilizes cell tight junctions to inhibit inflammation in intestinal epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 3:e2369. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J. S., Shin M., Kim H. J., Kim K. S., Choy H. E., Cho K. A. (2014). Caveolin-1 mediates Salmonella invasion via the regulation of SopE-dependent Rac1 activation and actin reorganization. J. Infect. Dis. 210, 793–802. 10.1093/infdis/jiu152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S., Yoon H., Kim M., Han A., Choi J., Choi J., et al. (2013). Hfq and ArcA are involved in the stationary phase-dependent activation of Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI1) under shaking culture conditions. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 23, 1664–1672. 10.4014/jmb.1305.05022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S., Yun J., Yoon H., Park C., Kim B., Jeon B., et al. (2007). Mlc regulation of Salmonella pathogenicity island I gene expression via hilE repression. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 1822–1832. 10.1093/nar/gkm060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S. L., Le T. X., Cowen D. S. (2003). SptP, a Salmonella typhimurium type III-secreted protein, inhibits the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by inhibiting Raf activation. Cell Microbiol. 5, 267–275. 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.t01-1-00274.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z., Zhang Y. G., Xia Y., Xu X., Jiao X., Sun J. (2016). Salmonella enteritidis effector AvrA stabilizes intestinal tight junctions via the JNK pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 26837–26849. 10.1074/jbc.M116.757393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Garrido J., Puerta-Fernández E., Cota I., Casadesús J. (2015). Virulence gene regulation by L-arabinose in Salmonella enterica. Genetics 200, 807–819. 10.1534/genetics.115.178103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R., Wu S., Liu X., Xia Y., Zhang Y. G., et al. (2010). Chronic effects of a Salmonella type III secretion effector protein AvrA in vivo. PLoS ONE 5:e10505. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R., Wu S., Zhang Y. G., Xia Y., Zhou Z., Kato I., et al. (2016). Salmonella protein AvrA activates the STAT3 signaling pathway in colon cancer. Neoplasia 18, 307–316. 10.1016/j.neo.2016.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchetti-Miganeh C., Burrowes E., Baysse C., Ermel G. (2008). The posttranscriptional regulator CsrA plays a central role in the adaptation of bacterial pathogens to different stages of infection in animal hosts. Microbiology 154, 16–29. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/012286-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchini S., Rowley G., Goldberg M. D., Hurd D., Harrison M., Hinton J. C. (2006). H-NS mediates the silencing of laterally acquired genes in bacteria. PLoS Pathog. 2:e81. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunelli M., Hurwitz R., Lambers J., Kolbe M. (2011). Crystal structure of PrgI-SipD: insight into a secretion competent state of the type three secretion system needle tip and its interaction with host ligands. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002163. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus S. L., Knodler L. A., Finlay B. B. (2002). Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium effector SigD/SopB is membrane-associated and ubiquitinated inside host cells. Cell Microbiol. 4, 435–446. 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00202.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus S. L., Wenk M. R., Steele-Mortimer O., Finlay B. B. (2001). A synaptojanin-homologous region of Salmonella typhimurium SigD is essential for inositol phosphatase activity and Akt activation. FEBS Lett. 494, 201–207. 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02356-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlovits T. C., Kubori T., Sukhan A., Thomas D. R., Galán J. E., Unger V. M. (2004). Structural insights into the assembly of the type III secretion needle complex. Science 306, 1040–1042. 10.1126/science.1102610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh M., Hillyard D. R. (1990). Nucleotide sequence of hns encoding the DNA-binding protein H-NS of Salmonella typhimurium. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:397. 10.1093/nar/18.11.3397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez L. C., Martínez-Flores I., Salgado H., Fernández-Mora M., Medina-Rivera A., Puente J. L., et al. (2014). In silico identification and experimental characterization of regulatory elements controlling the expression of the Salmonella csrB and csrC genes. J. Bacteriol. 196, 325–336. 10.1128/JB.00806-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez L. C., Yakhnin H., Camacho M. I., Georgellis D., Babitzke P., Puente J. L., et al. (2011). Integration of a complex regulatory cascade involving the SirA/BarA and Csr global regulatory systems that controls expression of the Salmonella SPI-1 and SPI-2 virulence regulons through HilD. Mol. Microbiol. 80, 1637–1656. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07674.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maserati A., Fink R. C., Lourenco A., Julius M. L., Diez-Gonzalez F. (2017). General response of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium to desiccation: a new role for the virulence factors sopD and sseD in survival. PLoS ONE 12:e0187692. 10.1371/journal.pone.0187692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGhie E. J., Hayward R. D., Koronakis V. (2001). Cooperation between actin-binding proteins of invasive Salmonella: SipA potentiates SipC nucleation and bundling of actin. EMBO J. 20, 2131–2139. 10.1093/emboj/20.9.2131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGhie E. J., Hayward R. D., Koronakis V. (2004). Control of actin turnover by a Salmonella invasion protein. Mol. Cell. 13, 497–510. 10.1016/S1097-2765(04)00053-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh A., Meikle L. M., Ormsby M. J., McCormick B. A., Christie J. M., Brewer J. M., et al. (2017). SipA Activation of Caspase-3 is a decisive mediator of host cell survival at early stages of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection. Infect. Immun. 85:e00393–17. 10.1128/IAI.00393-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McShan A. C., Anbanandam A., Patnaik S., De Guzman R. N. (2016). Characterization of the binding of hydroxyindole, indoleacetic acid, and morpholinoaniline to the Salmonella Type III secretion system proteins SipD and SipB. Chem. Med. Chem. 11, 963–971. 10.1002/cmdc.201600065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minamino T., Imada K., Namba K. (2008). Mechanisms of type III protein export for bacterial flagellar assembly. Mol. Biosyst. 4, 1105–1115. 10.1039/b808065h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirold S., Ehrbar K., Weissmüller A., Prager R., Tschäpe H., Rüssmann H., et al. (2001a). Salmonella host cell invasion emerged by acquisition of a mosaic of separate genetic elements, including Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI1). SPI5, and sopE2. J. Bacteriol. 183, 2348–2358. 10.1128/JB.183.7.2348-2358.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirold S., Rabsch W., Tschäpe H., Hardt W. D. (2001b). Transfer of the Salmonella type III effector sopE between unrelated phage families. J. Mol. Biol. 312, 7–16. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myeni S. K., Wang L., Zhou D. (2013). SipB-SipC complex is essential for translocon formation. PLoS ONE 8:e60499. 10.1371/journal.pone.0060499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myeni S. K., Zhou D. (2010). The C terminus of SipC binds and bundles F-actin to promote Salmonella invasion. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 13357–13363. 10.1074/jbc.M109.094045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarre W. W., Porwollik S., Wang Y., McClelland M., Rosen H., Libby S. J., et al. (2006). Selective silencing of foreign DNA with low GC content by the H-NS protein in Salmonella. Science 313, 236–238. 10.1126/science.1128794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris F. A., Wilson M. P., Wallis T. S., Galyov E. E., Majerus P. W. (1998). SopB, a protein required for virulence of Salmonella dublin, is an inositol phosphate phosphatase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95, 14057–14059. 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obregon C., Dreher D., Kok M., Cochand L., Kiama G. S., Nicod L. P. (2003). Human alveolar macrophages infected by virulent bacteria expressing SipB are a major source of active interleukin-18. Infect. Immun. 71, 4382–4388. 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4382-4388.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olekhnovich I. N., Kadner R. J. (2007). Role of nucleoid-associated proteins Hha and H-NS in expression of Salmonella enterica activators HilD, HilC, and RtsA required for cell invasion. J. Bacteriol. 189, 6882–6890. 10.1128/JB.00905-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen-Hughes T. A., Pavitt G. D., Santos D. S., Sidebotham J. M., Hulton C. S., Hinton J. C., et al. (1992). The chromatin-associated protein H-NS interacts with curved DNA to influence DNA topology and gene expression. Cell 71, 255–265. 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90354-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Esté C., Hidalgo A. A., Aguirre C., Briones A. C., Cabezas C. E., Castro-Severyn J., et al. (2018). The ArcAB two-component regulatory system promotes resistance to reactive oxygen species and systemic infection by Salmonella Typhimurium. PLoS ONE 13:e0203497. 10.1371/journal.pone.0203497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes-Amaya C. C., Valdés-García G., Juárez-González V. R., Rudiño-Piñera E., Bustamante V. H. (2018). The Hcp-like protein HilE inhibits homodimerization and DNA binding of the virulence-associated transcriptional regulator HilD in Salmonella. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 6578–6592. 10.1074/jbc.RA117.001421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry C. M., Hien T. T., Dougan G., White N. J., Farrar J. J. (2002). Typhoid fever. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 1770–1782. 10.1056/NEJMra020201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlova B., Volf J., Ondrackova P., Matiasovic J., Stepanova H., Crhanova M., et al. (2011). SPI-1-encoded type III secretion system of Salmonella enterica is required for the suppression of porcine alveolar macrophage cytokine expression. Vet. Res. 42:16. 10.1186/1297-9716-42-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts A. H., Guo Y., Ahmer B. M. M., Romeo T. (2019). Role of CsrA in stress responses and metabolism important for Salmonella virulence revealed by integrated transcriptomics. PLoS ONE 14:e0211430. 10.1371/journal.pone.0211430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prouty A. M., Gunn J. S. (2000). Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium invasion is repressed in the presence of bile. Infect. Immun. 68, 6763–6769. 10.1128/IAI.68.12.6763-6769.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que F., Wu S., Huang R. (2013). Salmonella pathogenicity island 1(SPI-1) at work. Curr. Microbiol. 66, 582–587. 10.1007/s00284-013-0307-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffatellu M., Wilson R. P., Chessa D., Andrews-Polymenis H., Tran Q. T., Lawhon S., et al. (2005). SipA, SopA, SopB, SopD, and SopE2 contribute to Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium invasion of epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 73, 146–154. 10.1128/IAI.73.1.146-154.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakeman J. L., Bonifield H. R., Miller S. I. (1999). A HilA-independent pathway to Salmonella typhimurium invasion gene transcription. J. Bacteriol. 181, 3096–3104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Escudero I., Ferrer N. L., Rotger R., Cid V. J., Molina M. (2011). Interaction of the Salmonella Typhimurium effector protein SopB with host cell Cdc42 is involved in intracellular replication. Mol. Microbiol. 80, 1220–1240. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07639.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph M. G., Weise C., Mirold S., Hillenbrand B., Bader B., Wittinghofer A., et al. (1999). Biochemical analysis of SopE from Salmonella typhimurium, a highly efficient guanosine nucleotide exchange factor for RhoGTPases. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 30501–30509. 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini S., Slauch J. M., Aldridge P. D., Rao C. V. (2010). Role of cross talk in regulating the dynamic expression of the flagellar Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 and type 1 fimbrial genes. J. Bacteriol. 192, 5767–5777. 10.1128/JB.00624-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schechter L. M., Jain S., Akbar S., Lee C. A. (2003). The small nucleoid-binding proteins H-NS, HU, and Fis affect hilA expression in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 71, 5432–5435. 10.1128/IAI.71.9.5432-5435.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schechter L. M., Lee C. A. (2001). AraC/XylS family members, HilC and HilD, directly bind and derepress the Salmonella typhimurium hilA promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 40, 1289–1299. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02462.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer C. A., Cooper E., Miller S. I. (2000). The Salmonella type III secretion translocon protein SspC is inserted into the epithelial cell plasma membrane upon infection. Mol. Microbiol. 37, 1133–1145. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02066.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlumberger M. C., Hardt W. D. (2006). Salmonella type III secretion effectors: pulling the host cell's strings. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9, 46–54. 10.1016/j.mib.2005.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraidt O., Lefebre M. D., Brunner M. J., Schmied W. H., Schmidt A., Radics J., et al. (2010). Topology and organization of the Salmonella typhimurium type III secretion needle complex components. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000824. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder N., Henry T., de Chastellier C., Zhao W., Guilhon A. A., Gorvel J. P., et al. (2010). The virulence protein SopD2 regulates membrane dynamics of Salmonella-containing vacuoles. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001002. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekirov I., Gill N., Jogova M., Tam N., Robertson M., de Llanos R., et al. (2010). Salmonella SPI-1-mediated neutrophil recruitment during enteric colitis is associated with reduction and alteration in intestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes. 1, 30–41. 10.4161/gmic.1.1.10950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada T., Yamamoto K., Ishihama A. (2009). Involvement of the leucine response transcription factor LeuO in regulation of the genes for sulfa drug efflux. J. Bacteriol. 191, 4562–4571. 10.1128/JB.00108-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivcharan S., Yadav J., Qadri A. (2018). Host lipid sensing promotes invasion of cells with pathogenic Salmonella. Sci. Rep. 8:15501. 10.1038/s41598-018-33319-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivula C. P., Bogomolnaya L. M., Andrews-Polymenis H. L. (2008). A comparison of cecal colonization of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium in white leghorn chicks and Salmonella-resistant mice. BMC Microbiol. 8:182. 10.1186/1471-2180-8-182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srikanth C. V., Wall D. M., Maldonado-Contreras A., Shi H., Zhou D., Demma Z., et al. (2010). Salmonella pathogenesis and processing of secreted effectors by caspase-3. Science 330, 390–393. 10.1126/science.1194598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele-Mortimer O., Knodler L. A., Marcus S. L., Scheid M. P., Goh B., Pfeifer C. G., et al. (2000). Activation of Akt/protein kinase B in epithelial cells by the Salmonella typhimurium effector sigD. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 37718–37724. 10.1074/jbc.M008187200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stender S., Friebel A., Linder S., Rohde M., Mirold S., Hardt W. D. (2000). Identification of SopE2 from Salmonella typhimurium, a conserved guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Cdc42 of the host cell. Mol. Microbiol. 36, 1206–12021. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01933.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhan A., Kubori T., Wilson J., Galán J. E. (2001). Genetic analysis of assembly of the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium type III secretion-associated needle complex. J. Bacteriol. 183, 1159–1167. 10.1128/JB.183.4.1159-1167.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaya A., Kubota Y., Isogai E., Yamamoto T. (2005). Degradation of the HilC and HilD regulator proteins by ATP-dependent Lon protease leads to downregulation of Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 55, 839–852. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04425.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner S. A., Chassard C., Rigozzi E., Lacroix C., Stevens M. J. (2016). Bifidobacterium thermophilum RBL67 impacts on growth and virulence gene expression of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium. BMC Microbiol. 16:46. 10.1186/s12866-016-0659-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenor J. L., McCormick B. A., Ausubel F. M., Aballay A. (2004). Caenorhabditis elegans-based screen identifies Salmonella virulence factors required for conserved host-pathogen interactions. Curr. Biol. 14, 1018–1024. 10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplitski M., Goodier R. I., Ahmer B. M. (2003). Pathways leading from BarA/SirA to motility and virulence gene expression in Salmonella. J. Bacteriol. 185, 7257–7265. 10.1128/JB.185.24.7257-7265.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terebiznik M. R., Vieira O. V., Marcus S. L., Slade A., Yip C. M., Trimble W. S., et al. (2002). Elimination of host cell PtdIns(4,5)P(2) by bacterial SigD promotes membrane fission during invasion by Salmonella. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 766–773. 10.1038/ncb854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thijs I. M., De Keersmaecker S. C., Fadda A., Engelen K., Zhao H., McClelland M., et al. (2007). Delineation of the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium HilA regulon through genome-wide location and transcript analysis. J. Bacteriol. 189, 4587–4596. 10.1128/JB.00178-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans J., Van Melderen L. (2010). Post-transcriptional global regulation by CsrA in bacteria. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 67, 2897–2908. 10.1007/s00018-010-0381-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsou L. K., Lara-Tejero M., RoseFigura J., Zhang Z. J., Wang Y. C., Yount J. S., et al. (2016). Antibacterial flavonoids from medicinal plants covalently inactivate type III protein secretion substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2209–2218. 10.1021/jacs.5b11575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Engelenburg S. B., Palmer A. E. (2008). Quantification of real-time Salmonella effector type III secretion kinetics reveals differential secretion rates for SopE2 and SptP. Chem. Biol. 15, 619–628. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Parys A., Boyen F., Verbrugghe E., Leyman B., Bram F., Haesebrouck F., et al. (2012). Salmonella typhimurium induces SPI-1 and SPI-2 regulated and strain dependent downregulation of MHC II expression on porcine alveolar macrophages. Vet. Res. 43:52. 10.1186/1297-9716-43-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Velkinburgh J. C., Gunn J. S. (1999). PhoP-PhoQ-regulated loci are required for enhanced bile resistance in Salmonella spp. Infect. Immun. 67, 1614–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonaesch P., Sellin M. E., Cardini S., Singh V., Barthel M., Hardt W. D. (2014). The Salmonella Typhimurium effector protein SopE transiently localizes to the early SCV and contributes to intracellular replication. Cell Microbiol. 16, 1723–1735. 10.1111/cmi.12333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S., Königsmaier L., Lara-Tejero M., Lefebre M., Marlovits T. C., Galán J. E. (2010). Organization and coordinated assembly of the type III secretion export apparatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 17745–17750. 10.1073/pnas.1008053107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wain J., Hendriksen R. S., Mikoleit M. L., Keddy K. H., Ochiai R. L. (2015). Typhoid fever. Lancet 385, 1136–1145. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62708-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]