Abstract

Very little is known in broad comparative terms about the nature and content of election campaigns. In this article, we present the first systematic and comparative assessment of the electoral campaigns of candidates having competed in elections across the world along three dimensions: negative campaigning, emotional campaigning and populist rhetoric. We do so by introducing a new dataset, based on expert judgements, that allows us to retrace the content of campaigns of 97 candidates having competed in 43 elections worldwide between 2016 and 2018. To put the importance of these three dimensions of electoral campaigns into perspective, we comparatively assess the extent to which these three dimensions are more or less likely to capture the attention of news media and to determine the electoral fate of those who rely on them. Our analyses reveal that negativity and emotionality significantly and substantially drive media coverage and electoral results: more positive and enthusiasm-based campaigns increase media attention, but so do campaigns based on personal attacks and fear appeals, especially during presidential elections and when the number of competing candidates is lower. Looking at electoral success, negativity backlashes overall, and yet personal attacks can be used successfully to increase the chances of an electoral victory. Furthermore, both appeals to enthusiasm (but not when a lot of candidates compete) and fear (especially in presidential elections) work as intended to capture the attention of the public and transform it into better electoral fortunes. We also discuss the results of a case study of the 2017 French presidential election, where we compare the campaigns of four leading candidates (Emmanuel Macron, Marine Le Pen, François Fillon and Jean-Luc Mélenchon); results of the case study offer interesting insights to understand the general trends, and beyond.

Keywords: Comparative political communication, electoral campaigns, emotions, France, negative campaigning, populism

Introduction

Given the abundance of literature on the nature and content of election campaigns in some well-studied cases, it is surprising to realize that very little is known in broad comparative terms. When thinking of elections across the globe, in countries as diverse as Australia, Bulgaria, Colombia, Finland, Japan, Mexico, Pakistan, Russia, Spain or the USA, to name just a few, how do competing candidates communicate with their voters? And through which communication strategies do they try to convince them to vote for them, and not for their rivals? Can we point to universal trends, or is the use of electoral campaigns – and their effects – also a function of contextual differences?

Looking at the existing studies, mostly about the American case (which could even be considered as an outlier), three sets of communication strategies emerge: (1) the use of ‘negative campaigning’ strategies (Lau and Pomper, 2004; Nai and Walter, 2015), that is, to what extent competing candidates attack their rivals instead of promoting their own programme; (2) the use of emotional appeals (Brader, 2006; Ridout and Searles, 2011), that is, why and how candidates use messages intended to stir anxiety, rage, enthusiasm and other emotions in those exposed to them; (3) the use of a populist rhetoric (Jagers and Walgrave, 2007; Rooduijn and Pauwels, 2011), that is, and independently of the populist nature of the candidate itself from an ideological standpoint, to what extent they promote a vision of politics as a Manichean conflict between the pure people and the corrupt elite, often relying to a simplistic and demagogical language.

To what extent are different communication strategies able to shape media coverage? Following theories of mediatisation of politics (e.g. Mazzoleni and Schulz, 1999), the political system and its outcomes are increasingly co-dependent with the coverage of political events provided by news media. News media in modern democracies (and beyond) tend to cover political events by focusing on the ‘game of politics’, seen as a battleground between competing actors and by providing special attention to the conflicts and disagreements between them (Geer, 2006, 2012; Gerstlé et al., 1992; Patterson, 1993). Modern news media are attracted towards the more conflictual elements of politics; much evidence exists that news media are characterized by an increased ‘negativity’ (Bobba et al., 2013; Kleinnijenhuis, 2008), that is, the tendency to frame coverage of political events with a negative tone that promotes ‘conflict-centeredness’ and gives priority to disputes and disagreements between candidates: in recent years, up to 80% of all news stories related to US presidential elections focussed on negative ads (Geer, 2012). ‘News, according to the critics among the journalist, is nowadays more buffeted by rumors, controversies and trivialities’ (Plasser, 2005: 55). All this creates a situation where preferential coverage is given to more offensive, aggressive campaigns. Much evidence exists that the rhetoric strategies of candidates are able to drive media coverage:

Candidates want to get their message out, hoping to control the terms of the debate. They can air a positive ad and seek to influence voters with that spot. But the news media will likely ignore it. [. . .] A negative ad, however, can generate controversy and conflict, drawing attention from journalists. (Geer, 2012: 423)

Beyond media attention, the ultimate question that moves political operatives, spin doctors and campaign consultants is, of course, to what extent do campaigning strategies matter for the final result at the ballot box. The question of campaign effectiveness has been at the forefront of academic electoral research for many decades, at least since the publication in 1944 of Lazarsfeld and colleagues’ The People’s Choice. Many models have been developed to account for campaigning effects over the past decades, insisting on different type of effects or mechanisms (e.g. social position, partisan identification or agenda-setting framing, and priming; Gerstlé and Piar, 2016) and even if the magnitude of such effects is often questioned a rather consensual assumption is that the information carried through campaigns interacts with individual predispositions to shape opinions, and attitudinal behaviours (Nai et al., 2017).

In this article, we present the first systematic and comparative assessment of the electoral campaigns of candidates having competed in elections across the world along the three dimensions of negative campaigning, emotional campaigning and populist rhetoric. We do so by introducing a new dataset, based on expert judgements, that allows us to retrace the content of campaigns of 97 candidates having competed in 43 elections worldwide between 2016 and 2018 (Nai, 2018b). To put the importance of these three dimensions of electoral campaigns into perspective, we comparatively assess the extent to which these three dimensions are more or less likely to capture the attention of news media and to determine the electoral fate of those who rely on them. Furthermore, we will present a more detailed case study and focus on the campaign profile of four candidates having competed in the French presidential elections of 2017 (Macron, Le Pen, Fillon and Mélenchon). The case study will provide additional insights into the three dimensions of electoral campaigning discussed here – negativity, emotionality and populism – and their saliency within a specific set of political dynamics.

Dimensions of electoral campaigns

The literature on comparative political communication faces the absence of an integrated framework able to provide a comprehensive picture of the different dimensions of electoral campaigns (Nai and Maier, 2018). Among a multitude of approaches, three main competing (yet complementary) research streams coexist, each focussed on a specific facet of electoral campaigns: negative campaigning, emotional campaigning and the use of a populist rhetoric. To be sure, these three dimensions are not fully exhaustive of the diversity of campaign strategies; they nonetheless represent the major dimensions of modern electoral campaigning, and echo the contemporary focus of the literature on (comparative) political communication.

First, much attention has been provided to the ‘tone’ of electoral campaigns, that is, the extent to which competing candidates rely on policy or personal attacks to comment on, criticize or even belittle political opponents (Lau and Pomper, 2004; Nai and Walter, 2015). Scholars disagree about the extent to which negative campaigning ‘works’ (Lau et al., 2007); if several studies show that negativity reduce positive feelings for the target and overall harm its image in the eyes of the voters (Pinkleton, 1997; Shen and Wu, 2002), others highlight that negative messages are ‘a two-edged sword that can sometimes cut the sponsor more than the target’ (Shapiro and Rieger, 1992: 135). Several studies have found that negative campaigning has unintentional systemic effects, for instance, in depressing turnout and mobilization (Ansolabehere and Iyengar, 1995) or in fostering cynicism, apathy and a gloomier public mood (Yoon et al., 2005; Nai and Seeberg, 2018); others see in negative campaigning the potential to increase citizens attention and mobilize them (Geer, 2006). A more nuanced approach tends to differentiate between policy and character attacks. Character attacks have been shown to be more effective than issue attacks (Brooks and Geer, 2007) while being riskier, as they face a stronger probability of ‘backlash’ effects than policy attacks (Carraro et al., 2010). Furthermore, character attacks are particularly disliked by the public, and are more likely to depress participation and turnout than policy attacks (Min, 2004), but are probably more memorable.

A second, related dimension of contemporary electoral campaigns is the use of appeals intended to stir an emotional response in the audience (Brader, 2006; Crigler et al., 2006; Ridout and Searles, 2011), starting from the assumption that emotions act as powerful determinants of attitudinal behaviours (Marcus et al., 2000; Marcus and MacKuen, 1993; Nai et al., 2017). Most research draws a key difference between two basic sets of emotions: hope/enthusiasm on the one hand and fear/anxiety on the other: anxious citizens are likely to pay more attention to information and campaigns, which makes them easier targets for persuasion (Nai et al., 2017). Enthusiastic citizens, on the other hand, are more likely to get invested and participate (Marcus and MacKuen, 1993), but they do so by relying strongly on their previously held partisan beliefs and attitudes (Brader, 2006; Marcus et al., 2000). Campaign messages able to stir those emotions, thus, are particularly likely to be effective to get their message across, and thus candidates have strong incentives to rely on emotional campaigns (Ridout and Searles, 2011).

Third, a more recent research stream focuses on populism not as an ideology but rather as a communication and rhetoric style, ‘a communication frame that appeals to and identifies with the people, and pretends to speak in their name [. . .,] a conspicuous exhibition of closeness to (ordinary) citizens’ (Jagers and Walgrave, 2007: 322). Building on the definition of populism as a ‘thin’ ideology (e.g. Mudde, 2004), two elements stand out: people-centrism and anti-elitism (Rooduijn and Pauwels, 2011: 1273). First, appeals to ‘the people’, a specific national group, ‘the citizens’, ‘the country’ and so forth, composed by individuals who are sovereign by nature, and often underprivileged or misunderstood (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2013). Second, populist communication targets ‘the system’ (the government, the institutions, the politicians themselves), usually seen as out of touch, globally promoting an anti-establishment stance against political elites ‘who live in ivory towers and only pursue their own interests’ (Jagers and Walgrave, 2007: 324). Next to people-centrism and anti-elitism, research on populist communication also discusses one additional element, that is, the use of a simpler, informal language void of excessively technical terms; this rhetoric style is intended to create a sense of proximity between the candidate and the audience and often equates with a covert form of anti-intellectualism, a ‘denial of expert knowledge, and the championing of common sense’ (Moffitt and Tormey, 2014: 391).

Data and methods

Dataset

In this article, we rely on aggregated expert judgements to evaluate the content of campaigns, which might seem unorthodox. Scholars usually rely on content analysis of specific communication channels, such as party manifestos, other official campaign events and so forth.1 Content-analysing campaign content in selected channels comes however with some main disadvantages within the framework of a large-scale comparative design. On the one hand, not all communication channels exist in all contexts (for instance, TV ads are banned in France). It cannot simply be assumed that all channels are an equivalent vehicle to carry those different dimensions of electoral communication in all elections worldwide; for instance, measuring populist communication in candidates’ websites might be a good idea in countries where Internet penetration is high, but this is far from being the case everywhere. On the other hand, content analysis of specific communication channels provides a channel-specific image of the campaign, and is unable to qualify the campaign of candidates on the whole (Elmelund-Præstekær, 2010; Walter and Vliegenthart, 2010). Some candidates might use populist appeals especially during debates, and not at all in TV commercials; coding only one or the other would, necessarily, provide a skewed image of their overall campaign. Asking experts to assess the content of the overall campaign circumvents this problem, and provides a measure of campaign content that is not channel-specific, thus allowing for a broader understanding of the phenomenon.

We rely on a new dataset about campaigning strategies of parties and candidates competing in elections worldwide (Nai, 2018a, 2018b; Nai and Maier, 2018).2 Since June 2016 systematic data were collected after all national elections worldwide through expert surveys. In the direct aftermath of any given election, a sample of domestic and international scholars with proven expertise about politics and elections in that country was contacted, and asked to provide their opinion on several aspects of the election, including the campaigning strategies of competing candidates (e.g. the tone of their campaign or the issues on which they attacked their rivals the most). Expert opinions were then aggregated to provide comparable information about elections and competing candidates. The whole dataset contains information for 250+ candidates having competed in more than 90 legislative and presidential elections, based on aggregated ratings provided by more than 1400 experts worldwide.

In this article, we focus on a subset of the database and compare the content of electoral campaigns of candidates having competed in presidential or legislative elections that were held in post-industrial countries. Evidence will be presented for 97 candidates having competed in 43 national elections (the full list of elections and candidates can be found in Appendix 1, Tables 3 and 4).3

Experts

We define an ‘expert’ as a scholar who has worked/published on the country’s electoral politics, political communication (including political journalism) and/or electoral behaviour, or related disciplines. Expertise is established by the presence of one of the following criteria: (1) existing relevant academic publications (including conference papers); (2) holding a chair in those disciplines and (3) membership of a relevant research group, professional network or organized section of such a group; (4) explicit self-assessed expertise in professional webpage (e.g. biography on university webpage). Experts were contacted via a personalized email during the week following the election and received two reminders, respectively 1 and 2 weeks after the first invitation. The invitation email contained the link to the questionnaire, administered through Qualtrics. The number of expert ratings collected varies across elections and candidates; on average, 24.2 experts evaluated each candidate (a higher number than in other studies, for instance on US presidents; see, for example, Lilienfeld et al., 2012).4 On average, experts in the whole sample lean slightly to the left (M = 4.32/10, SD = 1.79), 73% are domestic (i.e. work in the country for which they were asked to evaluate the election) and 32% are female. Overall, experts declared themselves very familiar with the elections (M = 8.03/10, SD = 1.77) and estimated that the questions in the survey were relatively easy to answer (M = 6.54/10, SD = 2.39).

Measuring the content and dimensions of electoral campaigns

We measure the content of electoral campaigns – negativity, emotionality and populism – via aggregated expert judgements. Experts evaluated the tone of candidates’ campaign on a scale ranging between −10 (the campaign was exclusively negative) and 10 (the campaign was exclusively positive); their answers were then aggregated to provide a score of campaign negativity for each competing candidate. Experts were also asked to evaluate, for each candidate, the type of attack messages they mostly used against their rivals. The obtained variable ranges between 1 ‘exclusively policy attacks’ and 5 ‘exclusively character attacks’.

Concerning the use of emotional messages, experts were asked to assess the extent to which candidates used anxiety and enthusiasm appeals; experts had to provide a score ranging between 0 ‘very low use’ and 10 ‘very high use’. Finally, the use of a populist rhetoric is measured through three questions that grasp the extent to which the candidate might be someone who (1) identifies with the common people and celebrates their authenticity, (2) uses an informal style and popular language, and (3) uses an anti-establishment and anti-elite rhetoric. Answers range from 0 ‘disagrees strongly’ to 4 ‘agrees strongly’ (Nai and Maier, 2018).5 All variables have been standardized to fit into a 0–1 scale to allow comparison and simplify their interpretation in regressions.

Results

Electoral communication in elections worldwide

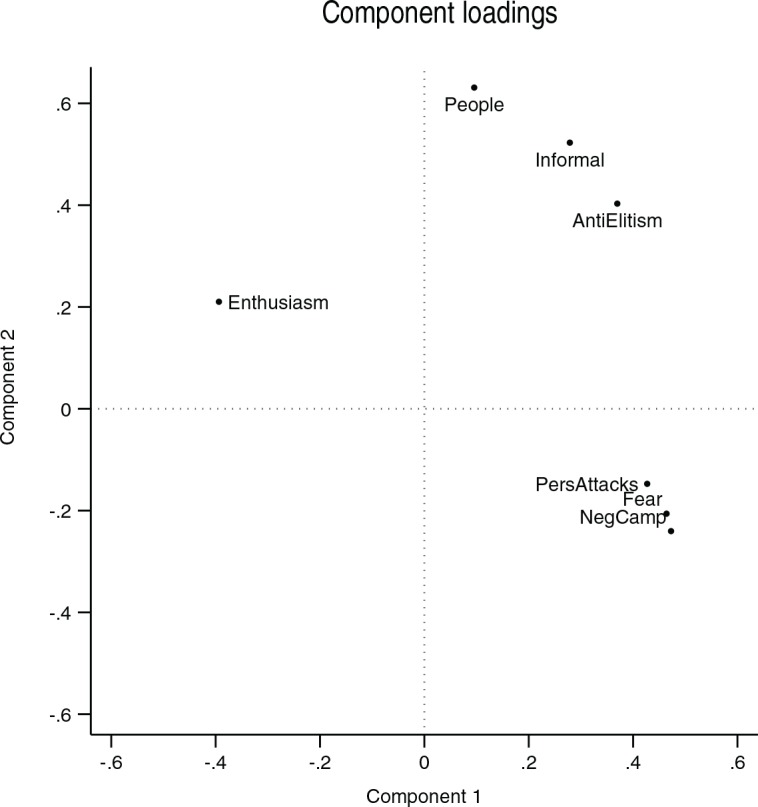

The seven elements of communication (negative tone, use of personal attacks, fear appeals, enthusiasm appeals, people-centrism, anti-elitism, simplistic language) are, of course, related; for instance, negative campaigns are more likely to contain fear appeals (Crigler et al., 2006), and populist communication seems to go hand in hand with the use of more negative and offensive messages (Nai, 2018a). From a theoretical standpoint, conceptual equivalences and overlaps undoubtedly exist between, for instance, the more ‘aggressive’ components of populist communication (e.g. the use of a brash rhetoric and the lack of respect towards political adversaries) and the use of a negative tone and political attacks. In order to uncover the factors beneath these seven elements, we performed a factor analyses (PCA; principal component analysis); results (Figure 9 in Appendix 2) suggest the existence of two underlying dimensions.6 The first underlying component (eigenvalue = 3.61, proportion = 51.6%) opposes, on the one side, campaigns with a negative tone, personal attacks and fear appeals (anti-elitism is also not far away on the horizontal axis), and on the other side campaigns based on enthusiasm; this first underlying dimension thus measures the overall ‘loathing’ level of the campaign. The second underlying dimension (eigenvalue = 1.96, proportion = 28.0%) is more straightforward and measures the overall level of ‘populism’: campaigns have higher scores on this second dimension when candidates score high on people-centrism, anti-elitism and the use of an informal language.

In Figure 1 we plot the scores of all 97 candidates in our database on the two underlying dimensions of loathing (high negativity, use of personal attacks and fear appeals, and low enthusiasm appeals) and populism (high use of appeals to the people, informal language and anti-elitism) extracted by PCA.

Figure 1.

Loathing and populism in electoral campaigns by international candidates (n = 69).

N = 97. Values on the x-axis (Loathing) reflect candidates’ scores on the first underlying dimension extracted by PCA (component 1); values on the y-axis (Populism) reflect candidates’ scores on the second underlying dimension extracted by PCA (component 2).

Looking at the graph, we see that many candidates from right to far-right and populist parties score high on the first component (loathing), on the right-hand side of the figure. In this group of candidates we find, among many others, Donald Trump (whose atypical political profile and personality reputation has been extensively documented; Nai and Maier, 2018), Marine Le Pen, the leader of the nativist Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) Alexander Gauland, Austria’s far-right FPÖ leader Norbert Hofer, UKIP (UK Independence Party) leader Paul Nuttall, the brazen leader of the Dutch Freedom Party (PVV) Geert Wilders, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the leader of Italy’s nativist and far-right Lega Matteo Salvini and the ultranationalist leader of the Russian LDPR (Liberal Democratic Party of Russia) party Vladimir Zhirinovsky (described in the press as ‘the insane clown prince of Russian politics’,7 ‘Russia’s Trump’8 and one of ‘the usual nut-jobs’9). On the other end of this spectrum, having communicated thus with a more ‘positive’ and less aggressive campaign, we find more ‘established’ and mainstream candidates, including some key players in the current European political landscape, such as Angela Merkel, Emmanuel Macron, Austria’s Alexander van der Bellen or Finland’s centrist president Sauli Väinämö Niinistö.

The second dimension, populism, discriminates between more ‘mainstream’ candidates (again, Merkel, Macron, Australia’s former PM Malcolm Turnbull, Theresa May, and Japan’s PM Shinzo Abe) on the bottom, and candidates from opposition and protest parties such as Spain’s Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias, United Kingdom’s Jeremy Corbyn, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the newly minted president of Mexico Andrés Manuel López Obrador (also known as ‘AMLO’), and again candidates from far-right and Eurosceptic parties (Hofer, Salvini, and Austria FPÖ’s Heinz-Christian Strache), who scored high on this second dimension.

The effects of communication on media attention

Our dataset includes a direct measure of media attention, which standardizes this coverage across all media channels during the campaign.10 We regressed the candidates’ media attention measure in our database on their campaign profile. Figure 2 shows that the two underlying dimensions of campaigning style seem not to play a major role in shaping media attention for the candidates. To be sure, some illustrious examples exist that support the idea of preferential coverage for more offensive or populist candidates (e.g. Trump, Orbán, Erdoğan, Le Pen and Salvini for their high scores on the loathing dimension, and Babis, Corbyn, Erdoğan and López Obrador for their higher scores on the populist dimension). Overall, however, there is no flamboyant direct relationship to be shown.

Figure 2.

Dimensions of communication and media attention.

N = 97. Dependent variable is media attention and varies between 0 (‘very low’) and 100 (‘very high’).

Media attention is unlikely however to be only driven by campaigns, and other elements necessarily participate to shape it – which, in turn, also affect the nature and content of campaigns. For instance, incumbents naturally receive a much stronger media coverage (Hopmann et al., 2011). We thus regressed the candidates’ media attention on their campaign profile controlling for several determinants at the candidate level (left–right scale, gender, age and incumbency status) and context level (electoral system: PR (proportional representation) vs FPTP (first past the post), effective number of candidates, and type of election: presidential vs legislative). Table 1 present the results of four hierarchical models; the first model (M1) tests for the direct effect of the seven campaign components, controlling for candidate profile and the nature of the context; models M2–M4 test for the interaction effects between the seven campaign components and the characteristics of the context, and allow thus to assess to what extent the effects of campaigns depend on the specificities of the electoral context.

Table 1.

Media attention by elements of communication, hierarchical linear regressions.

| M1 |

M2 |

M3 |

M4 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Significance | Coef. | SE | Significance | Coef. | SE | Significance | Coef. | SE | Significance | |

| Negativity | −41.26 | (19.79) | * | −41.64 | (40.06) | −169.94 | (63.02) | ** | 110.21 | (56.80) | † | |

| Personal attacks | 34.88 | (13.97) | * | 36.76 | (22.68) | 83.61 | (45.96) | † | 8.73 | (40.39) | ||

| Enthusiasm | 49.31 | (13.38) | *** | 66.22 | (25.22) | ** | 105.02 | (39.25) | ** | 59.49 | (41.27) | |

| Fear | 48.38 | (15.08) | ** | 48.58 | (23.65) | * | 161.64 | (45.13) | *** | −60.61 | (43.10) | |

| Appeals to people | −11.33 | (8.82) | −14.42 | (12.76) | −25.07 | (28.25) | 12.69 | (25.53) | ||||

| Informal language | −9.53 | (9.51) | 0.15 | (14.44) | −50.08 | (28.87) | † | 24.40 | (29.10) | |||

| Anti-elitism | 8.15 | (7.95) | 6.71 | (13.59) | 32.17 | (24.65) | −31.39 | (24.03) | ||||

| Left–right | −0.79 | (0.96) | −1.35 | (1.06) | −0.82 | (0.95) | −0.67 | (0.95) | ||||

| Female | 1.58 | (3.44) | 1.68 | (3.72) | −0.14 | (3.46) | 1.83 | (3.40) | ||||

| Year born | 0.00 | (0.01) | −0.00 | (0.02) | 0.01 | (0.01) | 0.01 | (0.02) | ||||

| Incumbent | 6.88 | (3.57) | † | 8.45 | (3.81) | * | 4.48 | (3.46) | 5.41 | (3.63) | ||

| Electoral system: PR | 8.84 | (2.81) | ** | 33.68 | (27.22) | 9.66 | (3.16) | ** | 11.15 | (2.82) | *** | |

| Effective N of candidates (ENC) | 1.70 | (0.88) | † | 1.73 | (0.96) | † | 5.48 | (7.24) | 1.48 | (0.88) | † | |

| Presidential election | 2.70 | (3.25) | 3.98 | (3.48) | 3.63 | (3.55) | 22.96 | (27.01) | ||||

| PR × Negativity | 8.43 | (46.79) | ||||||||||

| PR × Personal Attacks | −9.81 | (28.74) | ||||||||||

| PR × Enthusiasm | −32.31 | (30.49) | ||||||||||

| PR × Fear | −7.28 | (31.57) | ||||||||||

| PR × Appeal to People | 2.98 | (18.41) | ||||||||||

| PR × Informal Language | −18.23 | (20.58) | ||||||||||

| PR × Anti-Elitism | 6.56 | (16.77) | ||||||||||

| ENC × Negativity | 28.27 | (13.10) | * | |||||||||

| ENC × Personal Attacks | −8.85 | (10.29) | ||||||||||

| ENC × Enthusiasm | −11.05 | (8.01) | ||||||||||

| ENC × Fear | −24.05 | (8.85) | ** | |||||||||

| ENC × Appeal to People | 3.08 | (6.53) | ||||||||||

| ENC × Informal Language | 7.98 | (5.46) | ||||||||||

| ENC × Anti-Elitism | −4.91 | (4.82) | ||||||||||

| Presidential Election × Negativity | −120.91 | (43.14) | ** | |||||||||

| Presidential Election × Personal Attacks | 24.24 | (31.20) | ||||||||||

| Presidential Election × Enthusiasm | −10.03 | (33.40) | ||||||||||

| Presidential Election × Fear | 88.73 | (34.51) | * | |||||||||

| Presidential Election × Appeal to People | −14.90 | (18.27) | ||||||||||

| Presidential Election × Informal Language | −26.72 | (21.93) | ||||||||||

| Presidential Election × Anti-Elitism | 27.82 | (18.96) | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 22.09 | (32.96) | 16.42 | (38.72) | −11.40 | (47.13) | −28.39 | (48.07) | ||||

| N (candidates) | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 | ||||||||

| N (elections) | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | ||||||||

| R 2 | 0.419 | 0.453 | 0.507 | 0.517 | ||||||||

| Model χ2 | 59.09 | 62.05 | 82.90 | 80.33 | ||||||||

All models are random-effect hierarchical linear regressions (HLM) where candidates are nested within elections. Dependent variable is media attention and varies between 0 (‘very low’) and 100 (‘very high’). PR: proportional representation.

p<0.001; ** p<0.01; * p<0.05; † p<0.10.

Our results seem to suggest, on the one hand, that more ‘positive’ campaigns tend to increase media attention. Negativity in itself reduces media attention, and the use of enthusiasm appeals is the single most important determinant of higher attention. This result goes against the idea that negativity sells, but can probably be understood via the mobilization potential of enthusiasm, shown to drive involvement: ‘when politics drums up enthusiasm, people immerse themselves in the symbolic festival’ (Marcus and MacKuen, 1993: 681). In this sense, campaigns carrying hopeful and enthusiastic messages capture the attention of the public by strengthening the resolve to participate; perhaps the best example in this sense is Obama’s 2008 ‘Hope’ message, which quickly became the most visible (and mediatized) feature of his electoral campaign. Emmanuel Macron also seems to have played the card of positive emotionality. On the other hand, our results also show that ‘nastier’ campaigns have the potential to drive media coverage. Ceteris paribus, candidates making a stronger usage of personal attacks were more likely to receive a wider media attention, and the same is the case of the use of fear appeals. Thus, if positive campaigns have the power to motivate and stimulate attention, it should not be concluded that negativity is always detrimental – incivility and fear also sell.

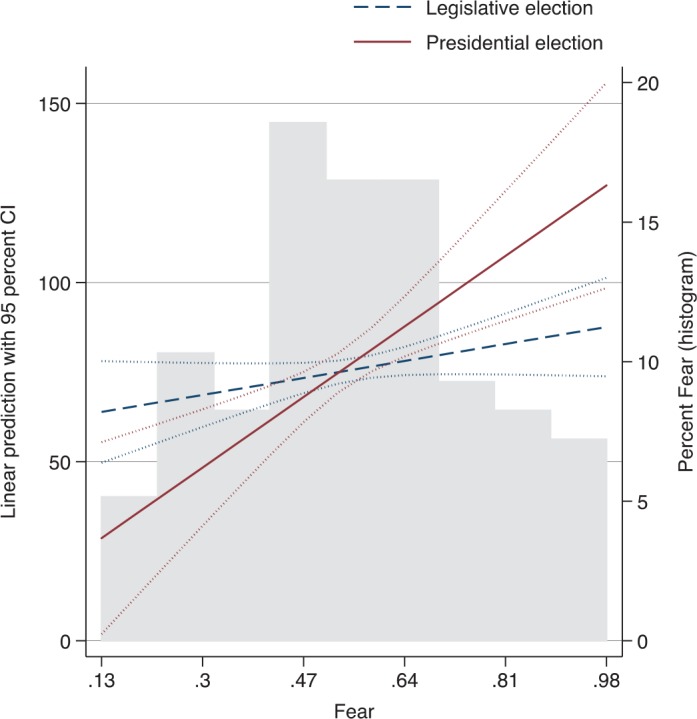

Looking at the models with interaction effects, our analyses reveal that negativity increases media attention during legislative elections and elections with a greater number of candidates; if overall detrimental, in the presence of a wider field of competing contestants negativity can be a useful tool to capture the attention of political journalist. Fear has the opposite effects: it works especially during presidential elections and when the number of competing candidates is lower. Figures 3 and 4 substantiate the interaction between negativity and the type of election, and between fear appeals and the type of election, respectively, via marginal effects.

Figure 3.

Media attention by Negativity × Election Type; marginal effects with 95% CIs.

N = 97. Dependent variable is media attention and varies between 0 (‘very low’) and 100 (‘very high’).

Figure 4.

Media attention by Fear × Election Type; marginal effects with 95% CIs.

N = 97. Dependent variable is media attention and varies between 0 (‘very low’) and 100 (‘very high’).

Turning to the remaining dimensions of electoral campaigns, our results show that populist communication is unlikely to drive a higher media attention overall (which, of course, is unrelated to the fact that populists themselves are often on the front page of traditional news media). The absence of effects for the populist dimensions of communication should however not lead to the conclusion that these forms of communication are excluded from the public debate; quite simply, they do not lead, on average, to a higher coverage (but neither to a lower one).

The effects of communication on electoral results

In this section, we test whether the candidates’ performance at the ballot box is a function of their campaigning choices. As previously for media attention, a preliminary overview seems to suggest that no particular broad trends exist. Figure 5 regresses the candidates’ electoral success on their campaign profile, both in terms of loathing (upper panel) and populism (bottom panel). Electoral success is measured in absolute terms, as the absolute percentage of votes received from each candidate;11 of course, to account for the fact that elections with a higher number of competing candidates reduces the chances that each single candidate receives a very high percentage of votes, we control our models by the effective number of competing candidates, computed adapting the classic formula by Laakso and Taagepera (1979).

Figure 5.

Dimensions of communication and electoral results.

N = 97. Dependent variable is absolute electoral success, expressed in the percentage of ballots received during the election (between 0% and 100%).

Figure 5 shows that loathing and populism do not affect electoral results in general. Yet, as previously, some indicative examples are worth mentioning. Emmanuel Macron (France), Mark Rutte (The Netherlands) and Malcolm Turnbull (Australia) used a less harsh campaign than (some of) their rivals and collected higher returns; on the other hand, candidates from the far-right in Germany (Alexander Gauland) and the United Kingdom (Paul Nuttall) exemplify the conjunction between loathing rhetoric and lower electoral results.

Although interesting in a comparative perspective, especially knowing the candidates and their behaviour, the illustration of Figure 5 does, however, not account for many candidate characteristics that undoubtedly drive both the use of certain rhetoric and their electoral success. For this, we regressed the candidates’ relative electoral success on their campaign profile controlling, as before for media attention, for several determinants at the candidate context levels (Table 2).

Table 2.

Electoral success by elements of communication, hierarchical linear regressions.

| M1 |

M2 |

M3 |

M4 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Significance | Coef. | SE | Significance | Coef. | SE | Significance | Coef. | SE | Significance | |

| Negativity | −42.55 | (16.39) | ** | −58.66 | (33.60) | † | −68.06 | (53.12) | 15.02 | (49.32) | ||

| Personal attacks | 23.67 | (11.58) | * | 20.71 | (19.02) | 55.94 | (38.78) | 12.69 | (35.08) | |||

| Enthusiasm | 39.49 | (11.08) | *** | 45.07 | (21.15) | * | 105.85 | (33.25) | ** | −6.67 | (35.83) | |

| Fear | 49.77 | (12.50) | *** | 60.18 | (19.84) | ** | 81.07 | (38.27) | * | −27.04 | (37.43) | |

| Appeals to people | 6.32 | (7.31) | 1.97 | (10.70) | 0.39 | (24.48) | 8.68 | (22.17) | ||||

| Informal language | −13.73 | (7.88) | † | −10.59 | (12.11) | −32.37 | (24.26) | −8.51 | (25.27) | |||

| Anti-elitism | 3.12 | (6.59) | 5.65 | (11.40) | 7.72 | (20.84) | 2.06 | (20.87) | ||||

| Left–right | −1.03 | (0.80) | −1.05 | (0.89) | −1.00 | (0.84) | −0.96 | (0.83) | ||||

| Female | −0.69 | (2.85) | −0.20 | (3.12) | −1.63 | (2.94) | −1.25 | (2.95) | ||||

| Year born | −0.00 | (0.01) | −0.01 | (0.01) | −0.00 | (0.01) | 0.01 | (0.01) | ||||

| Incumbent | 8.64 | (2.96) | ** | 9.13 | (3.20) | ** | 8.15 | (3.05) | ** | 7.92 | (3.15) | * |

| Electoral system: PR | 2.52 | (2.33) | 3.31 | (22.83) | 1.65 | (2.48) | 2.95 | (2.45) | ||||

| Effective N of candidates (ENC) | −2.65 | (0.73) | *** | −2.60 | (0.80) | ** | 4.88 | (6.09) | −2.44 | (0.77) | ** | |

| Presidential election | 4.56 | (2.69) | † | 4.46 | (2.91) | 4.40 | (2.81) | −25.70 | (23.46) | |||

| PR × Negativity | 30.63 | (39.24) | ||||||||||

| PR × Personal Attacks | 4.38 | (24.11) | ||||||||||

| PR × Enthusiasm | −13.68 | (25.57) | ||||||||||

| PR × Fear | −24.24 | (26.48) | ||||||||||

| PR × Appeal to People | 9.69 | (15.44) | ||||||||||

| PR × Informal Language | −4.30 | (17.26) | ||||||||||

| PR × Anti-Elitism | −5.08 | (14.07) | ||||||||||

| ENC × Negativity | 7.35 | (11.12) | ||||||||||

| ENC × Personal Attacks | −6.68 | (8.62) | ||||||||||

| ENC × Enthusiasm | −13.91 | (6.87) | * | |||||||||

| ENC × Fear | −8.18 | (7.49) | ||||||||||

| ENC × Appeal to People | 0.99 | (5.64) | ||||||||||

| ENC × Informal Language | 3.88 | (4.64) | ||||||||||

| ENC × Anti-Elitism | −0.75 | (4.08) | ||||||||||

| Presidential Election × Negativity | −44.37 | (37.46) | ||||||||||

| Presidential Election × Personal Attacks | 11.36 | (27.10) | ||||||||||

| Presidential Election × Enthusiasm | 39.78 | (29.01) | ||||||||||

| Presidential Election × Fear | 62.40 | (29.96) | * | |||||||||

| Presidential Election × Appeal to People | −0.86 | (15.87) | ||||||||||

| Presidential Election × Informal Language | −3.56 | (19.04) | ||||||||||

| Presidential Election × Anti-Elitism | −1.22 | (16.47) | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 8.24 | (27.31) | 16.12 | (32.47) | −27.02 | (39.81) | 16.45 | (41.75) | ||||

| N (candidates) | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 | ||||||||

| N (elections) | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | ||||||||

| R 2 | 0.567 | 0.582 | 0.620 | 0.605 | ||||||||

| Model χ2 | 107.4 | 104.5 | 122.2 | 114.8 | ||||||||

All models are random-effect hierarchical linear regressions (HLM) where candidates are nested within elections. Dependent variable is absolute electoral success, expressed in the percentage of ballots received during the election (between 0% and 100%). PR: proportional representation.

p<0.001; ** p<0.01; * p<0.05; † p<0.10.

Table 2 shows, first, that negativity backlashes (M1). Ceteris paribus, campaigns with a more negative tone tend to reap a more meagre bounty on election day, suggesting that only focussing on the opponents’ shortcomings is not enough to convince voters. The negative effect of campaign negativity exists, furthermore, across all the electoral systems (M2), number of competing candidates (M3) and types of election (M4). Our results suggest, however, that a certain type of attacks can be used successfully to increase the chances of an electoral victory: personal attacks. Compared with a candidate who did not rely on personal attacks at all, our results suggest that, ceteris paribus, candidates who use this rhetorical tool are rewarded on average with 24% more votes at the ballot box.

Turning to the effects of emotional messages, our results suggest that both enthusiasm and fear appeals work as intended to capture the attention of the public and transform it into better electoral fortunes. Compared with candidates who use absolutely no emotional appeals, candidates who go ‘full enthusiasm’ score on average 40% more votes, and candidates who go ‘full fear’ score on average 50% more votes. Further models show that these effects are partially contingent of the specific context in which they take place. Enthusiasm appeals become detrimental with an increasing number of competing candidates (M3) – suggesting that when voters face a broader palette of candidates to choose from, the use of positive emotions are unlikely to drive their choice for the candidate going positive – whereas fear appeals are especially effective to drive electoral success during presidential elections, and less so during legislative elections (M4, substantiated in Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Electoral success by Fear × Election Type; marginal effects with 95% CIs.

N = 97. Dependent variable is absolute electoral success, expressed in the percentage of ballots received during the election (between 0% and 100%).

Finally, our results also show that the use of informal language leads to lower electoral scores, but the effect is only significant at p < .1. The other components of populist rhetoric, as before for media attention, do not seem to drive substantially electoral success, neither directly nor in conjunction with characteristics of the context in which the election takes place. This being said, our results overall suggest that election campaigns are far from being inconsequential when it comes to the electoral fortune (and misfortune) of competing candidates. Although it is sometimes a function of specific characteristics of election, the use of negativity and emotionality significantly and strongly drives election results – even more so, in absolute terms, that does the incumbency status of the candidate, which has been shown consistently to predict a better electoral outcome (Cox and Katz, 1996).

A case study: The 2017 French presidential election

In international and comparative literature on electoral campaigns the French case is infrequently studied (Kaid et al., 1991). And, yet, many reasons justify a closer attention. Due to its strong Presidential system, France is thus a good case for the study of the ‘personalization’ of political competition (Gerstlé, 2013, 2017; Swanson and Mancini, 1996). Political commercials on television are proscribed in France since the ‘Loi Rocard’ of January 1990. As a consequence, however, France witnessed a ‘transfer’ of communication dynamics towards the news media (Gerstlé and Piar, 2016), which quickly became the main vehicle for the diffusion of campaign messages. In France, political journalism seems to have a weak(er) degree of independence (Esser, 2008), where journalists tend to follow the campaign themes set by the principal competing candidates. As a complement to the broad and transnational comparison presented in the previous sections, we provide here a ‘zoom in’ into the campaign style of four candidates having competed in the French elections of 2017 (E. Macron, M. Le Pen, F. Fillon, J.-L. Mélenchon). For those candidates, up to 34 experts rated the content of their campaigns.

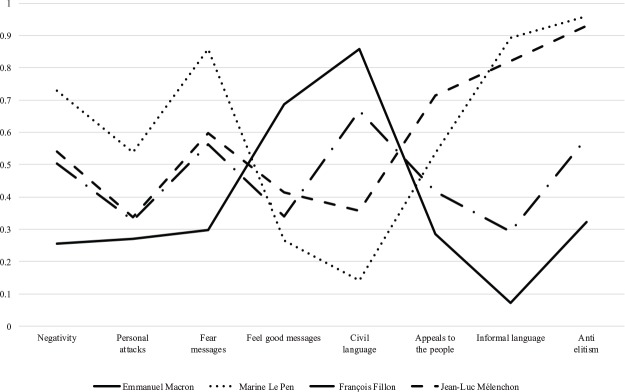

Substantial differences in the use of different rhetoric elements appear (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Elements of communication in the 2017 French presidential elections.

The y-axis represents the intensity of use of each communication element, as assessed by experts.

Across the eight rhetoric elements, the more substantial differences seem to exist when comparing Macron and Le Pen; for five elements out of eight – negativity, personal attacks, fear messages, informal language and anti-elitism – Macron scored the lowest, and Le Pen the highest. For the use of enthusiasm appeals and civil language the situation is completely reversed, with very low scores for Le Pen and high scores for Macron. The very high scores for Ms. Le Pen on negativity and the use of fear messages, informal language and anti-elitism (as well as the very low civility scores) are particularly sticking, in line with her image of contentious, negative and populist candidate often portrayed in the French and international media.12 Ms. Le Pen waged an electoral campaign based on a savant mix between emotional appeals intended to stir fear and anxiety – and especially on topics ‘owned’ by her party, such as terrorism, immigration and religious extremism. Our data also confirm the populist profile of Mélenchon,13 who has the dubious honour of scoring the highest in the use of informal language and anti-elitism – an effective strategy, as Mélenchon realized in the first round one of the most astounding exploits of the Fifth Republic.

The polar opposition between Macron and Le Pen appears clearly in Figure 7. Perhaps the best illustration of Ms. Le Pen’s aggressive rhetoric comes from the first sentence she uttered during the presidential debate before the second round of 3 May 2017 (Gerstlé, 2019). ‘Mr. Macron is the choice for uncontrolled globalisation, for uberisation, for job insecurity, for war of all against all, for economic pillage, for the butchering of France, for communitarianism’.14

During a highly aggressive debate, Mr. Macron – himself not shy of going on the offensive when pushed to it – was also accused of being the heir of disgraced François Hollande and a puppet in the hands of big corporations, Angela Merkel, and the ‘islamists’ of the umbrella organization French Muslims (formerly UOIF). All in all, in a way that was quite indicative of the whole campaign, ‘while Macron deliberately set out a clear set of policies with regard to unemployment, policing and education, for example, Marine Le Pen based the vast majority of her allocated time attacking Macron, both ad hominem and criticizing his policies but often based upon fallacious data or misrepresentation’ (Evans and Ivaldi, 2017: 115).

Figure 8 illustrates the extent to which the French candidates tailored their attacks on specific issues; for each candidate, high scores on the y-axis signal that the specific issue at stake (e.g. immigration and asylum) was a frequent frame for his or her attacks against the opponents. We find in the trends depicted the hotspots of the different political programmes by the competing candidates. Thus, for instance, the candidate of the far-right Front National (FN) mostly attacked her rivals on the issues that made the electoral fortune of her party, even at the time of her disgraced father and party founder: immigration, asylum, crime and security, and religion/morality. The populist Jean-Luc Mélenchon mostly criticized his rivals on issues typically owned by the left, from education to health care, unemployment and protection of the environment. François Fillon, following the neoliberal programme he defended during the primaries of his party in 2016, mostly attacked his rivals on economic issues such as spending, deficit and taxation, but also pushed a security agenda on foreign policy, defence and fight against crime. Emmanuel Macron, finally, mostly attacked his rivals on a key issue in his political programme, jobs and unemployment.

Figure 8.

Issue of attacks in the 2017 French presidential elections.

The y-axis represents to what extent experts judged that candidates attacked their rivals on those issues.

All in all, the figure suggests that candidates tend to attack on issues ‘owned’ by their party, confirming trends found in a handful of studies on the matter (e.g. Damore, 2002, 2004). Being considered as credible on a specific issue should reduce the chances that attacks backfire and end up harming the sponsor; on the other hand, going negative on issues on which actors have limited credibility is ‘unlikely to be effective and will probably [. . . rather underline] their own weaknesses than undermine the support of the opposition’ (Damore, 2002: 674).

Turning to media attention, the two frontrunners of the Presidential election – which will later advance to the second round – benefitted from a very high media attention; this is in line with overarching principles of political pluralism, an imperative in the French audio-visual media sphere during the last phases of electoral campaigns (Gerstlé and Piar, 2016). The unfortunate candidate from the centre-right Les Républicains, Fillon, was perhaps penalized – from an electoral standpoint at least15 – by the ‘Penelopegate’ scandal, according to which his wife and children were allegedly paid for fake jobs with public money. Nonetheless (and probably also because of that, to a large extent), media attention for the candidate was quite high on average – even if he suffered from a fading attention by the media over the last phases of the campaign, especially after the debate of 20 March 2017. Still in the presidential election, the outsider candidate from the far-left, Mélenchon, received comparatively less media attention than his rivals – thus partially failing to create sensation with innovative campaigning techniques such as the use of holograms during public rallies and the several ‘events’ he organized (such as his ‘boat ride’, rallies and extensive use of Youtube).

Discussion and conclusion

This article provided one of the first large-scale comparative studies of the nature and content of election campaigns worldwide, and their effects. Via a new dataset based on expert assessments (Nai, 2018b), we studied the campaign of 97 candidates having competed in 43 elections that happened across the world between 2016 and 2018. Following the recent literature on (comparative) political communication, we focussed on three sets of communication strategies: (1) the use of ‘negative campaigning’ strategies, that is, to what extent competing candidates attack their rivals instead of promoting their own programme; (2) the use of emotional appeals, that is, why and how candidates use messages intended to trigger emotions in those exposed to them; (3) the use of a populist rhetoric, that is, to what extent they promote a vision of politics as a Manichean conflict between the pure people and the corrupt elite, often relying to a simplistic and demagogical language.

A first description of the use of these three sets of strategies across all candidates in our dataset shows that the campaigns of ‘mainstream’ and centrist candidates worldwide are characterized by average-to-weak populism and negativity; this is, for instance, the case of Emmanuel Macron, Angela Merkel, Austria’s Alexander van der Bellen and (to a lesser extent) Hillary Clinton. On the other end of the spectrum, with aggressive campaigns characterized by a strong use of populist appeals, we find candidates from nativist and far-right parties such Austria’s far-right FPÖ leaders Norbert Hofer and Heinz-Christian Strache, Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the leader of Italy’s nativist and far-right Lega Matteo Salvini, and the ultranationalist leader of the Russian LDPR party Vladimir Zhirinovsky. The current leader of the Italian populist Five Star Movement (M5S), Luigi di Maio, also scores rather high on populism and negativity. Our results thus support the idea that populist candidates communicate differently than ‘mainstream’ candidates (Nai, 2018a); indeed, it is quite common to see populists described as ‘drunken dinner guest[s]’ (Arditi, 2007: 78) who rely on provocation and a more aggressive rhetoric, taking pleasure in displaying ‘bad manners’ (Moffitt, 2016) and adopting a ‘transgressive political style’ (Oliver and Rahn, 2016: 191) that ‘emphasises agitation, spectacular acts, exaggeration, calculated provocations, and the intended breech of political and socio-cultural taboos’ (Heinisch, 2003: 94).

Beyond these descriptive trends, our analyses revealed that two dimensions of electoral campaigns – negativity and emotionality – significantly and substantially drive media coverage and electoral results: more ‘positive’ campaigns tend to increase media attention, and the use of enthusiasm appeals being the single most important determinant of higher attention. However, ‘nastier’ campaigns also have the potential to drive media coverage, as candidates making a stronger usage of personal attacks and fear appeals were more likely to receive a wider media attention, especially during presidential elections and when the number of competing candidates is lower. Looking at electoral success, we showed that negativity backlashes overall, and yet personal attacks can be used successfully to increase the chances of an electoral victory. Furthermore, both appeals to enthusiasm (but not when a lot of candidates compete) and fear (especially in presidential elections) work as intended to capture the attention of the public and transform it into better electoral fortunes. The use of populist rhetoric does, comparatively, quite little, both in terms of media coverage and electoral results – nuancing, perhaps, the entrenched narrative about the ‘populist upsurge’ and the end of democratic order as we know it, even if our results speak more of the effects of populist rhetoric than of populist ideology per se, of course.

Beyond these general trends, we also presented a more fine-grained case study, in which we compared the campaign strategies of the four main candidates in the 2017 French presidential elections (Macron, Le Pen, Fillon and Mélenchon). The case study allowed us to illustrate some of the main trends discussed across all candidates and elections. For instance, Marine Le Pen shattered over the course of a little more than 2 hours of a very aggressive debate the hard work done over the previous 6 years, intended to soften and ‘de-demonise’ the image of her party. Even if her media coverage probably benefitted from that, the very dark tone of her remarks during the debate are likely to have costed her greatly at the ballot box and undoubtedly handicapped FN candidates during the legislative elections. Ms. Le Pen performance during that famed debate, in this sense, is to be considered as an ‘act of gravity’ (‘acte lourd’; Gerstlé, 1992) in politics. The analysis of the French case also allowed us to go beyond the general trends, and observe more closely the issue content of the campaigns run by the four candidates.

The analysis of the issues on which the French candidates attacked their rivals the most suggests that issue ownership is a powerful driver of negativity, confirming trends found in the literature (Damore, 2002). Thus, for instance, Marine Le Pen mostly attacked her rivals on immigration, asylum, crime and security, and religion/morality, and Emmanuel Macron mostly attacked his rivals on a key issue in his political programme: jobs and unemployment.

Overall, the trends presented in this article foster the relatively meagre research on comparative political communication. Within this broad agenda, several avenues for further research seem particularly promising. First, further analysis should take into account the role played by different dimensions of ‘information environments’ such as the media market and media system, following the idea that media are not only a gatekeeper for the diffusion of political information but can act as an independent political actor in itself (Van Aelst and Walgrave, 2017). Second, further studies should strive to integrate more directly how citizens react to negative messages, starting from the assumption that variations in individual cognitive and political predispositions moderate the reception of negative message and the resulting behaviours; for instance, following Fridkin and Kenney (2011), ‘citizens who have a low tolerance for certain types of negative political messages will be more affected by the (ir)relevance and (in)civility of messages’ (p. 309). Finally, further research should strive to understand the extent to which the communication strategies of candidates are also the result of an increasing polarization of the electorate, as suggested for instance by Geer (2006, 2012).

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the anonymous reviewers and the journal editors for their critiques, constructive comments, and suggestions; any remaining mistakes are of course our responsibility alone. Alessandro Nai acknowledges the material support provided by the Electoral Integrity Project (Harvard University and University of Sydney).

Appendix 1

Elections and candidates

Table 3.

Elections.

| Country | Election | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina | Legislative election | 22-Oct-2017 |

| Australia | Federal election | 2-Jul-2016 |

| Austria | Presidential election | 4-Dec-2016 |

| Austria | Legislative election | 15-Oct-2017 |

| Bulgaria | Presidential election | 6-Nov-2016 |

| Bulgaria | Legislative election | 26-Mar-2017 |

| Chile | Presidential election | 19-Nov-2017 |

| Colombia | Presidential election | 27-May-2018 |

| Croatia | Election of the Assembly | 11-Sep-2016 |

| Cyprus | Presidential election | 28-Jan-2018 |

| Czech Republic | Legislative election | 20-Oct-2017 |

| Czech Republic | Presidential election | 12-Jan-2018 |

| Finland | Presidential election | 28-Jan-2018 |

| France | Presidential election | 23-Apr-2017 |

| France | Election of the National Assembly | 11-Jun-2017 |

| Germany | Federal elections | 24-Sep-2017 |

| Hungary | Parliamentary elections | 8-Apr-2018 |

| Iceland | Presidential election | 25-Jun-2016 |

| Iceland | Election for the Althing | 29-Oct-2016 |

| Iceland | Election for the Althing | 28-Oct-2017 |

| Italy | General election | 4-Mar-2018 |

| Japan | House of Councillors election | 10-Jul-2016 |

| Japan | Election of the House of Representatives | 22-Oct-2017 |

| Lithuania | Parliamentary election | 9-Oct-2016 |

| Malaysia | Malaysian House of Representatives | 9-May-2018 |

| Malta | General elections | 3-Jun-2017 |

| Mexico | Presidential election | 1-Jul-2018 |

| New Zealand | General election | 23-Sep-2017 |

| Northern Ireland | Assembly election | 2-Mar-2017 |

| Norway | Parliamentary election | 11-Sep-2017 |

| Pakistan | General elections | 25-Jul-2018 |

| Romania | Legislative election | 11-Dec-2016 |

| Russia | Election of the State Duma | 18-Sep-2016 |

| Russia | Presidential election | 18-Mar-2018 |

| Slovenia | Presidential election | 22-Oct-2017 |

| Slovenia | Parliamentary elections | 3-Jun-2018 |

| South Korea | Presidential election | 9-May-2017 |

| Spain | General election | 26-Jun-2016 |

| Sweden | General election | 9-Sep-2018 |

| The Netherlands | General elections | 15-Mar-2017 |

| Turkey | Presidential election | 24-Jun-2018 |

| UK | Election of the British House of Commons | 8-Jun-2017 |

| USA | Presidential election | 8-Nov-2016 |

Table 4.

Candidates.

| Candidate | Party | Country | Election | Experts (*) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cristina Fernández de Kirchner | Frente para la Victoria | Argentina | L | 22-Oct-2017 | 14 (11) |

| Richard Di Natale | The Greens | Australia | L | 2-Jul-2016 | 26 (4) |

| Bill Shorten | Australian Labour Party | Australia | L | 2-Jul-2016 | 26 (6) |

| Malcolm Turnbull | Liberal Party of Australia/Nationals | Australia | L | 2-Jul-2016 | 26 (9) |

| Norbert Hofer | Freedom Party of Austria | Austria | P | 4-Dec-2016 | 37 (17) |

| Christian Kern | Social Democratic Party of Austria | Austria | L | 15-Oct-2017 | 27 (7) |

| Sebastian Kurz | Austrian People’s Party | Austria | L | 15-Oct-17 | 27 (8) |

| Heinz-Christian Strache | Freedom Party of Austria | Austria | L | 15-Oct-2017 | 27 (7) |

| Alexander Van der Bellen | Independent candidate/The Greens | Austria | P | 4-Dec-2016 | 37 (16) |

| Boyko Borisov | Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria | Bulgaria | L | 26-Mar-2017 | 15 (4) |

| Korneliya Ninova | Bulgarian Socialist Party | Bulgaria | L | 26-Mar-2017 | 15 (4) |

| Rumen Radev | Independent candidate/Bulgarian Socialist Party | Bulgaria | P | 6-Nov-2016 | 23 (11) |

| Tsetska Tsacheva | Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria | Bulgaria | P | 6-Nov-2016 | 23 (10) |

| Alejandro Guillier | Independent candidate/The Force of the Majority | Chile | P | 19-Nov-2017 | 11 (7) |

| Iván Duque Márquez | Grand Alliance for Colombia | Colombia | P | 27-May-2018 | 16 (6) |

| Gustavo Petro | List of Decency | Colombia | P | 27-May-2018 | 16 (8) |

| Zoran Milanović | Social Democratic Party of Croatia | Croatia | L | 11-Sep-2016 | 18 (4) |

| Božo Petrov | Bridge of Independent Lists | Croatia | L | 11-Sep-2016 | 18 (3) |

| Andrej Plenković | Croatian Democratic Union | Croatia | L | 11-Sep-2016 | 18 (6) |

| Nicos Anastasiades | Democratic Rally | Cyprus | P | 28-Jan-2018 | 9 (7) |

| Andrej Babiš | ANO | Czech Republic | L | 20-Oct-2017 | 23 (6) |

| Jiří Drahoš | Independent candidate | Czech Republic | P | 12-Jan-2018 | 18 (8) |

| Tomio Okamura | Freedom and Direct Democracy | Czech Republic | L | 20-Oct-2017 | 23 (9) |

| Lubomír Zaorálek | Czech Social Democratic Party | Czech Republic | L | 20-Oct-2017 | 23 (4) |

| Miloš Zeman | Party of Civic Rights | Czech Republic | P | 12-Jan-2018 | 18 (10) |

| Pekka Haavisto | Green League | Finland | P | 28-Jan-2018 | 18 (10) |

| Sauli Niinistö | Independent candidate | Finland | P | 28-Jan-2018 | 18 (7) |

| François Baroin | Les Républicains | France | L | 11-Jun-2017 | 12 (4) |

| Bernard Cazeneuve | Parti Socialiste | France | L | 11-Jun-2017 | 12 (4) |

| François Fillon | Les Républicains | France | P | 23-Apr-2017 | 34 (6) |

| Marine Le Pen | Front National | France | P | 23-Apr-2017 | 34 (6) |

| Emmanuel Macron | En Marche | France | P | 23-Apr-2017 | 34 (7) |

| Jean-Luc Mélenchon | La France Insoumise | France | P | 23-Apr-2017 | 34 (7) |

| Alexander Gauland | Alternative for Germany | Germany | L | 24-Sep-2017 | 44 (13) |

| Angela Merkel | CDU/CSU | Germany | L | 24-Sep-2017 | 44 (11) |

| Martin Schulz | SPD | Germany | L | 24-Sep-2017 | 44 (13) |

| Viktor Orbán | Fidesz | Hungary | L | 8-Apr-2018 | 12 (4) |

| Gábor Vona | Jobbik | Hungary | L | 8-Apr-2018 | 12 (5) |

| Bjarni Benediktsson | Independence Party | Iceland | L | 28-Oct-2017 | 7 (3) |

| Oddný Guðbjörg Harðardóttir | Social Democratic Alliance | Iceland | L | 29-Oct-2016 | 14 (4) |

| Katrín Jakobsdóttir | Left-Green Movement | Iceland | L | 29-Oct-2016 | 14 (4) |

| Katrín Jakobsdóttir | Left-Green Movement | Iceland | L | 28-Oct-2017 | 7 (4) |

| Birgitta Jónsdóttir | Pirate Party | Iceland | L | 29-Oct-2016 | 14 (3) |

| Davíð Oddsson | Independence Party | Iceland | P | 25-Jun-2016 | 14 (3) |

| Silvio Berlusconi | Forza Italia | Italy | L | 4-Mar-2018 | 34 (9) |

| Luigi Di Maio | Movimento 5 Stelle | Italy | L | 4-Mar-2018 | 34 (5) |

| Matteo Renzi | Partito Democratico | Italy | L | 4-Mar-2018 | 34 (7) |

| Matteo Salvini | Lega | Italy | L | 4-Mar-2018 | 34 (8) |

| Shinzō Abe | Liberal Democratic Party | Japan | L | 10-Jul-2016 | 21 (6) |

| Shinzō Abe | Liberal Democratic Party of Japan | Japan | L | 22-Oct-2017 | 20 (8) |

| Yukio Edano | Democratic Party of Japan | Japan | L | 10-Jul-2016 | 21 (4) |

| Yuriko Koike | Kibō no Tō | Japan | L | 22-Oct-2017 | 20 (7) |

| Kazuo Shii | Japanese Communist Party | Japan | L | 10-Jul-2016 | 21 (3) |

| Natsuo Yamaguchi | Komeito | Japan | L | 10-Jul-2016 | 21 (5) |

| Algirdas Butkevičius | Social Democratic Party of Lithuania | Lithuania | L | 9-Oct-2016 | 28 (5) |

| Ramūnas Karbauskis | Lithuanian Peasant and Greens Union | Lithuania | L | 9-Oct-2016 | 28 (3) |

| Gabrielius Landsbergis | Homeland Union – Lithuanian Christian Democrats | Lithuania | L | 9-Oct-2016 | 28 (8) |

| Mahathir Mohamad | Pakatan Harapan | Malaysia | L | 9-May-2018 | 9 (3) |

| Najib Razak | Barisan Nasional | Malaysia | L | 9-May-2018 | 9 (6) |

| Simon Busuttil | Nationalist Party | Malta | L | 3-Jun-2017 | 11 (5) |

| Joseph Muscat | Labour Party | Malta | L | 3-Jun-2017 | 11 (4) |

| Ricardo Anaya | National Action Party | Mexico | P | 1-Jul-2018 | 27 (12) |

| Andrés Manuel López Obrador | National Regeneration Movement | Mexico | P | 1-Jul-2018 | 27 (11) |

| Bill English | National | New Zealand | L | 23-Sep-2017 | 16 (4) |

| Winston Peters | New Zealand First | New Zealand | L | 23-Sep-2017 | 16 (4) |

| Arlene Foster | Democratic Unionist Party | Northern Ireland | L | 2-Mar-2017 | 21 (10) |

| Michelle O’Neill | Sinn Féin | Northern Ireland | L | 2-Mar-2017 | 21 (7) |

| Siv Jensen | Progress Party | Norway | L | 11-Sep-2017 | 26 (4) |

| Erna Solberg | Conservative Party | Norway | L | 11-Sep-2017 | 26 (9) |

| Jonas Gahr Støre | Labour Party | Norway | L | 11-Sep-2017 | 26 (3) |

| Imran Khan | Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf | Pakistan | L | 25-Jul-2018 | 17 (5) |

| Shehbaz Sharif | Pakistan Muslim League | Pakistan | L | 25-Jul-2018 | 17 (9) |

| Liviu Dragnea | Social Democratic Party | Romania | L | 11-Dec-2016 | 23 (13) |

| Alina Gorghiu | National Liberal Party | Romania | L | 11-Dec-2016 | 23 (5) |

| Dmitry Medvedev | United Russia | Russia | L | 18-Sep-2016 | 28 (9) |

| Vladimir Putin | Independent candidate | Russia | P | 18-Mar-2018 | 20 (8) |

| Vladimir Zhirinovsky | Liberal Democratic Party | Russia | L | 18-Sep-2016 | 28 (9) |

| Vladimir Zhirinovsky | Liberal Democratic Party | Russia | P | 18-Mar-2018 | 20 (9) |

| Janez Janša | Slovenian Democratic Party | Slovenia | L | 3-Jun-2018 | 5 (5) |

| Borut Pahor | Independent candidate | Slovenia | P | 22-Oct-2017 | 6 (4) |

| Hong Jun-pyo | Liberty Korea Party | South Korea | P | 9-May-2017 | 8 (4) |

| Pablo Iglesias | Unidos Podemos | Spain | L | 26-Jun-2016 | 19 (4) |

| Albert Rivera | Ciudadanos | Spain | L | 26-Jun-2016 | 19 (3) |

| Pedro Sánchez | Partido Socialista Obrero Español | Spain | L | 26-Jun-2016 | 19 (4) |

| Jimmie Åkesson | Sweden Democrats | Sweden | L | 9-Sep-2018 | 9 (5) |

| Mark Rutte | People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy | The Netherlands | L | 15-Mar-2017 | 40 (8) |

| Sybrand van Haersma Buma | Christian Democratic Appeal | The Netherlands | L | 15-Mar-2017 | 40 (4) |

| Geert Wilders | Party for Freedom | The Netherlands | L | 15-Mar-2017 | 40 (13) |

| Meral Akşener | İyi Party | Turkey | P | 24-Jun-2018 | 26 (9) |

| Recep Tayyip Erdoğan | Justice and Development Party | Turkey | P | 24-Jun-2018 | 26 (7) |

| Muharrem İnce | Republican People’s Party | Turkey | P | 24-Jun-2018 | 26 (8) |

| Jeremy Corbyn | Labour Party | UK | L | 8-Jun-2017 | 48 (14) |

| Tim Farron | Liberal Democrats | UK | L | 8-Jun-2017 | 48 (4) |

| Theresa May | Conservative Party | UK | L | 8-Jun-2017 | 48 (10) |

| Paul Nuttall | UK Independence Party | UK | L | 8-Jun-2017 | 48 (4) |

| Hillary Clinton | Democratic Party | USA | P | 8-Nov-2016 | 75 (28) |

| Donald Trump | Republican Party | USA | P | 8-Nov-2016 | 75 (34) |

L refers to legislative elections, and P to presidential elections.

(*)For the battery of questions measuring the use of populist language (appeals to the people, use of informal language, anti-elitism), only a subset of experts was consulted, signalled as the number within parentheses.

Appendix 2

Additional models

Table 5.

Media attention by elements of communication, hierarchical linear regressions.

| M1 |

M2 |

M3 |

M4 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Significance | Coef. | SE | Significance | Coef. | SE | Significance | Coef. | SE | Significance | |

| Loathing | 0.78 | (0.92) | −0.37 | (1.59) | −1.12 | (2.15) | 1.91 | (2.52) | ||||

| Populism | −0.54 | (1.11) | 0.29 | (1.85) | −2.35 | (3.19) | 2.18 | (3.37) | ||||

| Left-right | −0.14 | (1.05) | −0.24 | (1.07) | −0.21 | (1.06) | −0.33 | (1.08) | ||||

| Female | −0.86 | (3.81) | 0.19 | (3.98) | −0.99 | (3.97) | −0.95 | (3.87) | ||||

| Year born | −0.01 | (0.02) | −0.01 | (0.02) | −0.01 | (0.02) | −0.01 | (0.02) | ||||

| Incumbent | 13.63 | (3.51) | *** | 13.63 | (3.59) | *** | 14.01 | (3.56) | *** | 14.66 | (3.70) | *** |

| Electoral system: PR | 5.49 | (3.07) | † | 5.52 | (3.11) | † | 4.98 | (3.12) | 5.56 | (3.15) | † | |

| Effective N of candidates (ENC) | 1.21 | (0.98) | 1.11 | (1.00) | 1.19 | (0.99) | 1.15 | (0.99) | ||||

| Presidential election | 3.57 | (3.63) | 4.07 | (3.71) | 3.89 | (3.69) | 3.93 | (3.67) | ||||

| PR × Loathing | 1.50 | (1.62) | ||||||||||

| PR × Populism | −1.14 | (2.36) | ||||||||||

| ENC × Loathing | 0.43 | (0.44) | ||||||||||

| ENC × Populism | 0.41 | (0.68) | ||||||||||

| Presidential Election × Loathing | −0.70 | (1.68) | ||||||||||

| Presidential Election × Populism | −2.12 | (2.52) | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 76.42 | (32.00) | * | 75.06 | (32.29) | * | 76.02 | (32.32) | * | 73.28 | (32.71) | * |

| N (candidates) | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 | ||||||||

| N (elections) | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | ||||||||

| R 2 | 0.197 | 0.207 | 0.209 | 0.206 | ||||||||

| Model χ2 | 21.35 | 22.18 | 22.43 | 22 | ||||||||

All models are random-effect hierarchical linear regressions (HLM) where candidates are nested within elections. Dependent variable is media attention and varies between 0 (‘very low’) and 100 (‘very high’). PR: proportional representation.

p<0.001; ** p<0.01; * p<0.05; † p<0.10.

Table 6.

Electoral success by elements of communication, hierarchical linear regressions.

| M1 |

M2 |

M3 |

M4 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Significance | Coef. | SE | Significance | Coef. | SE | Significance | Coef. | SE | Significance | |

| Loathing | 0.06 | (0.77) | −1.16 | (1.32) | −3.36 | (1.76) | † | 2.55 | (2.09) | |||

| Populism | 0.64 | (0.92) | 1.17 | (1.54) | 1.03 | (2.60) | 0.54 | (2.79) | ||||

| Left-right | −0.40 | (0.87) | −0.44 | (0.89) | −0.50 | (0.86) | −0.43 | (0.89) | ||||

| Female | −2.17 | (3.17) | −1.28 | (3.29) | −1.25 | (3.23) | −1.72 | (3.21) | ||||

| Year born | −0.01 | (0.01) | −0.01 | (0.01) | −0.01 | (0.01) | −0.01 | (0.01) | ||||

| Incumbent | 14.13 | (2.92) | *** | 14.12 | (2.98) | *** | 14.29 | (2.90) | *** | 14.74 | (3.06) | *** |

| Electoral system: PR | −0.32 | (2.55) | −0.27 | (2.58) | −1.11 | (2.54) | −0.87 | (2.61) | ||||

| Effective N of candidates (ENC) | −3.00 | (0.82) | *** | −3.13 | (0.83) | *** | −3.11 | (0.81) | *** | −2.97 | (0.82) | *** |

| Presidential election | 5.01 | (3.02) | † | 5.40 | (3.08) | † | 4.87 | (3.01) | 5.05 | (3.04) | † | |

| PR × Loathing | 1.71 | (1.49) | ||||||||||

| PR × Populism | −0.74 | (1.96) | ||||||||||

| ENC × Loathing | 0.77 | (0.36) | * | |||||||||

| ENC × Populism | −0.09 | (0.56) | ||||||||||

| Presidential Election × Loathing | −1.79 | (1.39) | ||||||||||

| Presidential Election × Populism | 0.18 | (2.09) | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 56.81 | (26.62) | * | 55.62 | (26.81) | * | 59.98 | (26.36) | * | 59.92 | (27.09) | * |

| N (candidates) | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 | ||||||||

| N (elections) | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | ||||||||

| R 2 | 0.397 | 0.407 | 0.429 | 0.409 | ||||||||

| Model χ2 | 57.29 | 58.31 | 63.84 | 58.72 | ||||||||

All models are random-effect hierarchical linear regressions (HLM) where candidates are nested within elections. Dependent variable is absolute electoral success, expressed in the percentage of ballots received during the election (between 0% and 100%). PR: proportional representation.

p<0.001; ** p<0.01; * p<0.05; † p<0.10.

Figure 9.

Underlying dimensions of electoral communication (PCA loading scores).

N = 97. Components extracted through PCA; test of sphericity p < .001.

For a general overview on the study of political communication in French election, see Gerstlé (2017).

To increase robustness, we only include candidates for which at least three independent experts provided information.

The number of answers varies quite significantly between elections; thus, for instance, we were able to collect only six expert survey for Slovenia, but 75 for the 2016 election in the United States; these differences, of course, translate the different size and development of academic markets in the countries covered. Given that individual expert answers are aggregated, the higher the number of answers collected the higher the reliability of the final score. It is however important to note that even for countries with comparatively less answers, the total number of experts contacted is still substantially higher than for other similar studies; that, plus the fact that robustness checks seem to exclude the presence of expert biases, suggests that the composition of expert samples should not affect our measures excessively. We discuss the existence (and extent) of expert biases in Nai (2018b).

The number of expert assessments is lower for the populism battery (into parentheses in Table 4 in Appendix 1). To keep the length of the questionnaire at bay, some batteries of questions were asked only to subsamples of experts; this is the case of the ‘populism’ battery, and other batteries used to measure the personality of candidates (Nai and Maier, 2018) which will not be discussed in this article.

Full PCA (principal component analysis) results available upon request.

See Diana Bruk (2013).

See Anna Nemtsova (2016).

See John Simpson (2012).

Experts were asked to assess how much candidates were present in the national news media during the campaign before the election, on a 0–100 scale.

Additional models with an alternative measure of electoral success (relative measure, standardized by the effective number of competing candidates) yield very similar results. Results are available upon request at the authors.

See Cécile Alduy (2013).

See David Chazan (2017).

‘Monsieur Macron est le choix de la mondialisation sauvage, de l’ubérisation, de la précarité, de la guerre de tous contre tous, du saccage économique, notamment de nos grands groupes, du dépeçage de la France, du communautarisme’.

See Kim Willsher (2017).

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Alessandro Nai acknowledges that this work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation under Grant P300P1_161163.

Contributor Information

Jacques Gerstlé, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, France.

Alessandro Nai, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

References

- Alduy C. (2013). The devil’s daughter. The Atlantic, October Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2013/10/the-devils-daughter/309467/.

- Ansolabehere S, Iyengar S. (1995) Going Negative: How Attack Ads Shrink and Polarize the Electorate. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arditi B. (2007) Politics on the Edges of Liberalism: Difference, Populism, Revolution, Agitation. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bobba G, Legnante G, Roncarolo F, et al. (2013) Candidates in a negative light: The 2013 Italian election campaign in the media. Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica 43(3): 353–380. [Google Scholar]

- Brader T. (2006) Campaigning for Hearts and Minds: How Emotional Appeals in Political Ads Work. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DJ, Geer JG. (2007) Beyond negativity: The effects of incivility on the electorate. American Journal of Political Science 51(1): 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bruk D. (2003) The best of Vladimir Zhirinovsky, the Clown Prince of Russian politics. Vice, 11 August Available at: https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/xd5q47/the-best-of-vladimir-zhirinovsky-russias-craziest-politician.

- Carraro L, Gawronski B, Castelli L. (2010) Losing on all fronts: The effects of negative versus positive person-based campaigns on implicit and explicit evaluations of political candidates. British Journal of Social Psychology 49(3): 453–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazan D. (2017) As Macron sweeps to victory in France, resistance is growing in the heartland of the far-left. The Telegraph, 17 June Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/06/17/macron-sweeps-victory-france-resistance-growing-heartland-far/.

- Cox GW, Katz JN. (1996) Why did the incumbency advantage in US House elections grow? American Journal of Political Science 40(2): 478–497. [Google Scholar]

- Crigler A, Just M, Belt T. (2006) The three faces of negative campaigning: The democratic implications of attack ads, cynical news, and fear-arousing messages. In: Redlawsk DP. (eds) Feeling Politics: Emotion in Political Information Processing. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 135–163. [Google Scholar]

- Damore DF. (2002) Candidate strategy and the decision to go negative. Political Research Quarterly 55(3): 669–685. [Google Scholar]

- Damore DF. (2004) The dynamics of issue ownership in presidential campaigns. Political Research Quarterly 57(3): 391–397. [Google Scholar]

- Elmelund-Præstekær C. (2010) Beyond American negativity: Toward a general understanding of the determinants of negative campaigning. European Political Science Review 2(1): 137–156. [Google Scholar]

- Esser F. (2008) Dimensions of political news cultures: Sound bite and image bite news in France, Germany, Great Britain, and the United States. The International Journal of Press/Politics 13(4): 401–428. [Google Scholar]

- Evans J, Ivaldi G. (2017) The French Presidential Elections. A Political Reformation? Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Fridkin KL, Kenney PJ. (2011) Variability in citizens’ reactions to different types of negative campaigns. American Journal of Political Science 55(2): 307–325. [Google Scholar]

- Geer JG. (2006) In Defense of Negativity: Attack Ads in Presidential Campaigns. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Geer JG. (2012) The news media and the rise of negativity in presidential campaigns. PS: Political Science & Politics 45(3): 422–427. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstlé J. (1992) La communication politique [Political communication]. Paris: PUF. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstlé J. (2013) Les campagnes présidentielles depuis 1965 [Presidential campaigns since 1965]. In: Bréchon P. (dir.) Les élections présidentielles en France [Presidential elections in France]. Paris: La documentation Française, pp. 76–107. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstlé J. (2017) La communication électorale [Electoral communication]. In: Deloye Y. and Mayer N. (dirs) Analyses électorales [Electoral analyses]. Bruxelles: Bruylant, pp. 905–964. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstlé J. (2019) Onze débats télévisés pour une campagne présidentielle [Eleven TV debates for one presidential campaign]. In: Théviot A. (dir.) Médias et élections. Les campagnes présidentielle et législatives de 2017 [Media and elections. Campaigns for the Presidential and Legislative elections of 2017]. Lille: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstlé J, Piar C. (2016) La communication politique [Political communication]. Paris: Colin. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstlé J, Duhamel O, Davis DK. (1992). La couverture télévisée des campagnes présidentielles. L’élection de 1988 aux États-Unis et en France [TV coverage of presidential campaigns in France. The 1988 US and French elections]. Pouvoirs 63: 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Heinisch R. (2003) Success in opposition–failure in government: Explaining the performance of right-wing populist parties in public office. West European Politics 26(3): 91–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hopmann DN, de Vreese CH, Albæk E. (2011) Incumbency bonus in election news coverage explained: The logics of political power and the media market. Journal of Communication 61(2): 264–282. [Google Scholar]