Abstract

Purpose

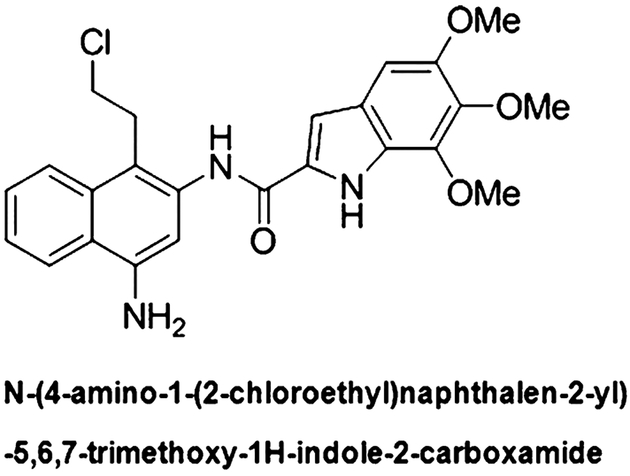

ML-970 (AS-I-145; NSC 716970) is an indolecarboxamide synthesized as a less toxic analog of CC-1065 and duocarmycin, a natural product that binds the A-T-rich DNA minor groove and alkylates DNA. The NCI60 screening showed that ML-970 had potent cytotoxic activity, with an average GI50 of 34 nM. The aim of this study is to define the pharmacological properties of this novel anticancer agent.

Methods

We established an HPLC method for the compound, examined its stability, protein binding, and metabolism by S9 enzymes, and conducted pharmacokinetic studies of the compound in two strains of mice using two different formulations.

Results

ML-970 was relatively stable in plasma, being largely intact after an 8-h incubation in mouse plasma at 37°C. The compound was extensively bound to plasma proteins. ML-970 was only minimally metabolized by the enzymes present in S9 preparation and was not appreciably excreted in the urine or feces. The solution formulation provided higher Cmax, AUC, F values, and greater bio-availability, although the suspension formulation resulted in a later Tmax and a slightly longer T1/2. To determine the fate of the compound, we accomplished in-depth studies of tissue distribution; the results indicated that the compound undergoes extensive enterohepatic circulation.

Conclusions

The results obtained from this study will be relevant to the further development of the compound and may explain the lower myelotoxicity of this analog compared to CC-1065.

Keywords: ML-970 (NSC 716970), Indolecarboxamide, HPLC, Protein binding, Pharmacokinetics, Enterohepatic, circulation

Introduction

There are increasing efforts toward developing novel therapeutic agents with better therapeutic response and lower side effects. The purpose of the present study was to carry preclinical pharmacology studies of ML-970 (NSC 716970), a newly identified anticancer agent that is under preclinical development. ML-970 (Fig. 1) is an indolecarboxamide synthesized as a less toxic analog of CC-1065 and duocarmycin, a natural product that binds the A-T-rich DNA minor groove and alkylates DNA [1]. Following initial demonstrations of the anticancer activity of the compound, it was sent to the NCI’s Developmental Therapeutics Program for further testing. The NCI60 screening showed that ML-970 had potent cytotoxic activity, with an average GI50 of 34 nM [1]. The compound was then tested in the hollow fiber assay, yielding a total score of 54 points, and efficiently killing six different cell lines [2–4].

Fig. 1.

Structure of ML-970

Preliminary in vivo anticancer efficacy studies were accomplished in animal xenograft models of glioma (SF295), and lung (H522), breast (MDA-MB-435), and ovarian (OVCAR-3) cancers [1, 4]. ML-970 shows significant antitumor effects in all of the models. Compared with other CC-1065 analogs, ML-970 appears to exert decreased liver and bone marrow toxicity, as indicated by in vitro assays and the xenograft studies [1, 4].

Given its potent anticancer activity and acceptable toxicity, it is possible that ML-970 may eventually transit to human clinical trials. As such, it will be necessary to first obtain a better understanding of the pharmacological characteristics of the compound, including its plasma stability, serum protein binding, distribution, and metabolism. We herein report the findings of our in vitro and in vivo studies, including mouse pharmacokinetic studies of the compound given in different formulations and by different routes, and preliminary rat pharmacokinetics following oral administration.

Materials and methods

Chemicals, reagents, and animals

All chemicals and solvents used for sample preparation and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis were of analytical grade. Acetonitrile (HPLC grade), methanol (HPLC grade), and formic acid were purchased from Fisher Chemicals (Fairlawn, NJ). Other chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Mouse plasma samples were purchased from Lampire Biological Laboratories (Pipersville, PA). Hepatic S9 fractions from ICR-CD-1 mice, Sprague–Dawley rats, and humans were purchased from Celsis In Vitro Technologies (Baltimore, MD). The National Cancer Institute provided the test agent, ML-970 (NSC 716970). A stock solution of the compound (2 mM) was prepared in methanol and stored at −80°C. Samples of heparinized mouse (non-Swiss albino) and rat (Sprague–Dawley) plasma were purchased from Lampire Biological Laboratories (Pipersville, PA). Pathogen-free female athymic nude mice (nu/nu, ~25 g) were obtained from the Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center (Frederick, MD), and female CD-1 (ICR) mice were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN). All animals were fed with commercial diet and provided water ad libitum. The University of Alabama at Birmingham’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved the protocols for the care and use of mice. Studies were accomplished in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH).

Analytical methods

An analytical method using HPLC was developed to monitor ML-970 in mouse and rat plasma and tissues, as well as in mouse urine and feces. The HPLC system made use of an Agilent 1120 instrument. ML-970 was separated on a Zorbax SB-C18 (5 μm, 150 × 4.6 mm) analytical column with a Zorbax Reliance Cartridge Guard Column (SB-C18). The mobile phase was composed of 60% acetonitrile in water containing 0.1% formic acid, and the eluate was monitored by UV at 308 nm. The peak area for ML-970 was used to establish standard curves and for quantitative analysis of samples.

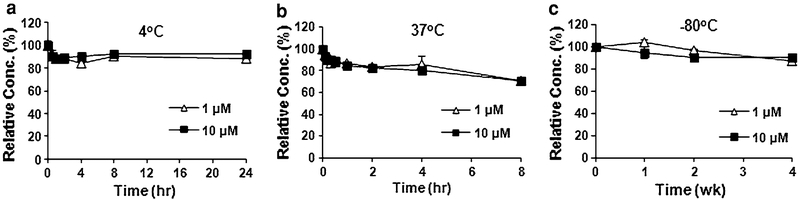

Stability of ML-970 in mouse plasma

The stability of ML-970 in mouse plasma was determined at 37, 4, and −80°C. To determine the stability at 37°C, plasma samples containing 1 or 10 μM ML-970 were placed in a water bath, and samples were taken for extraction and analysis after 5, 10, 20, 30, and 60 min, and 2, 4, and 8 h. To determine the stability at 4°C, plasma samples containing ML-970 were placed in a refrigerator at this temperature, and samples were taken for extraction and analysis at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, and 24 h. For stability at −80°C, plasma samples containing ML-970 were placed in a freezer at this temperature, and samples were taken for extraction and analysis after 1, 2, and 4 weeks. Concentrations, as percentages of the original concentration, were plotted against time to illustrate the stability of the compound.

Binding of ML-970 to mouse plasma proteins

The extent to which ML-970 was bound by plasma proteins was assessed by a previously described method using a micro-ultrafiltration system [5]. Samples of mouse plasma containing ML-970 (0.1, 1.0, and 10 μM) were maintained at 37°C for 1 h. Controls were prepared using methanol in place of plasma. From each of these preparations, a portion was taken and placed in a sample reservoir of an Amicon Centrifree® ultrafiltration system (30 kDa; Millipore Co., Bedford, MA, USA). The filter systems were centrifuged at 2,000×g until the reservoirs were dry. From each sample, triplicate portions were taken for analysis by HPLC. The amounts present in the filtrate were designated as “free drug” (F), because protein-bound drug could not pass through the membrane due to the small pore size. The concentrations of the unfiltered solutions were also determined by triplicate analyses. This amount represented the “total drug” concentration (T). The amount bound to the filter (X) was also considered. The percentage of ML-970 bound to plasma proteins was calculated as: % bound = [(T–F–X)/T] × 100.

S9 metabolism

We carried out a preliminary stability and metabolic study of ML-970 using murine and human hepatic S9 fractions containing phase I and II metabolic enzymes as described previously [6, 7]. In brief, the reaction mixture contained 10 μM of ML-970 and 1 mg/ml of S9 preparation, and the reactions were carried out in 100 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4). The negative controls did not contain the hepatic S9 fractions. Metabolic reactions were initiated by adding phase I (NADPH-regenerating systems) or phase II (UDPGA and PAPS) reagents to the reaction mixtures, respectively, and samples were incubated in a water bath at 37°C. Duplicate aliquots of the mixtures from a single reaction tube for each assay were taken at 0, 15, 30, 45, and 60 min, and the samples were processed and analyzed by HPLC. The stability of the drug was determined by analysis of intact ML-970, in comparison with negative control (without S9 fractions).

Pharmacokinetic studies in mice

To evaluate the pharmacokinetics of ML-970 administered in the solution formulation (PEG400/EtOH/Tween 80/D5 W), female nude mice were dosed i.v. via a lateral tail vein (20 mg/kg), i.p. (50 mg/kg), or p.o. (100 mg/kg) with ML-970. At 5, 15, and 30 min, and 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h (for the i.v. route) or 10 and 30 min, and 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24, and 48 h (for the other routes) after dosing, blood samples were collected into heparinized tubes via a retro-orbital bleed. To evaluate the pharmacokinetics of the compound in the suspension formulation (0.05% Tween 80/Saline), female nude mice were dosed i.p. (15 mg/kg) or p.o. (100 mg/kg) with ML-970. Blood samples were obtained at 10 and 30 min and 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h after administration. For all five of these studies, tissue samples (lungs, liver, heart, spleen, kidneys, muscle, and brain) were also collected at necropsy at the same time points.

To conduct a more in-depth study of tissue distribution of the compound, and to assess its pharmacokinetics when given at low doses, female CD-1 mice were dosed i.v. via a lateral tail vein (2.5 mg/kg) or p.o. (2.5 mg/kg) with ML-970. At various times after dosing, blood samples were collected into heparinized tubes via a retro-orbital bleed, and numerous tissue samples (brain, heart, lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys, stomach, stomach contents, small intestine, small intestine contents, large intestine, large intestine contents, gallbladder, fat, and skeletal muscle) were obtained during necropsy.

Urine and feces were also collected from mice housed in metabolic cages during several of the studies (for up to 48 h after dosing). For each urine collection, the collection containers and cages were washed twice with 0.9% saline. Each urine collection and each wash were analyzed separately, and then the values were added together to generate the percent of the compound excreted in urine.

For all studies, at least three samples were collected for each time point for each matrix (blood, tissues, urine, and feces). Data are presented as the mean ± SD of these values. Plasma was separated by centrifugation, and tissues and feces were homogenized in PBS and then extracted with acetonitrile, while urine and the washes were extracted directly. The PBS volumes used for the various tissues were based on tissue weights (5 ml PBS/g). Extracted samples were analyzed using the HPLC procedure. Considering that there were different LLQs and detection ranges for the different tissues. The above HPLC method was validated for each tissue, and data were calculated based on tissue-specific standard curves. If a sample concentration in initial assay was not covered in the range of a given standard curve, proper dilution and concentration procedures were used in repeated testing. Pharmacokinetic parameters for all samples were derived using Phoenix WinNonlin (Version 6.0, Mountain View, CA, USA).

Preliminary pharmacokinetics (dose-finding study) in rats

Female Sprague–Dawley rats were administered either a single oral dose of ML-970 (2.5 or 5 mg/kg) in the solution formulation or were administered one dose per day of the solution formulation of ML-970 (2.5 or 5 mg/kg) for 5 days. At 1, 6, and 12 h after the first and fifth administration, plasma and tissue samples (lungs, liver, kidneys, small intestine, and small intestine contents) were collected for extraction and HPLC analysis.

Results

Method validation

We followed USA FDA guidance to validate our HPLC methods for in vitro and in vivo sample analyses. The HPLC method gave linear calibration curves for the investigated concentration range (0.01–20 μM). The correlation coefficients (r2) were ≥0.999. The compound was extracted from plasma, tissue and feces homogenates, and urine using acetonitrile to precipitate the proteins, and then samples were dried under a stream of air and re-dissolved in the mobile phase (60% acetonitrile in water). The intraday precision values were in the range of 6.97–7.59%, while interday precision values were in the range of 1.32–7.52%; the accuracy of the quantitative analysis of the compound ranged from 98.89 to 109.74% for intraday and 94.40 to 101.32% for interday analyses in all fluids and tissue homogenates. These parameters were within the ranges recommended by the US FDA (CDER/US FDA, 2001). The limit of quantitation (LoQ) in mouse plasma was 0.128 μM.

Stability in plasma

ML-970 is relatively stable in mouse plasma (Fig. 2), with approximately 70% of the compound remaining after an 8-h incubation in plasma at 37°C. This occurred for both the lower (1 μM) and higher (10 μM) concentrations of the drug, with 70.9 and 70.2% remaining at 8 h, respectively. We also found that ML-970 can be stored at either 4°C for a short period of time or −80°C for a longer period of time. After a 24-h storage in mouse plasma at 4°C, approximately 90% of the compound still remained intact (88.6% for the 1 μM and 92.4% for the 10 μM, respectively). When the plasma was stored at −80°C, there was no significant degradation of ML-970 after a week of storage; after being stored for 4 weeks at −80°C, there was 87.5 and 89.8% of the compound remaining for the 1 and 10 μM concentrations, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Stability of ML-970 in mouse plasma at 37°C (a), 4°C (b), and −80°C (c)

Plasma protein binding

ML-970 was found to be extensively bound to mouse plasma proteins in vitro, with the 0.1 μM concentration demonstrating 87.57% binding, the 1.0 μM concentration with 89.31% binding, and the 10.0 μM concentration being 90.89% bound, respectively.

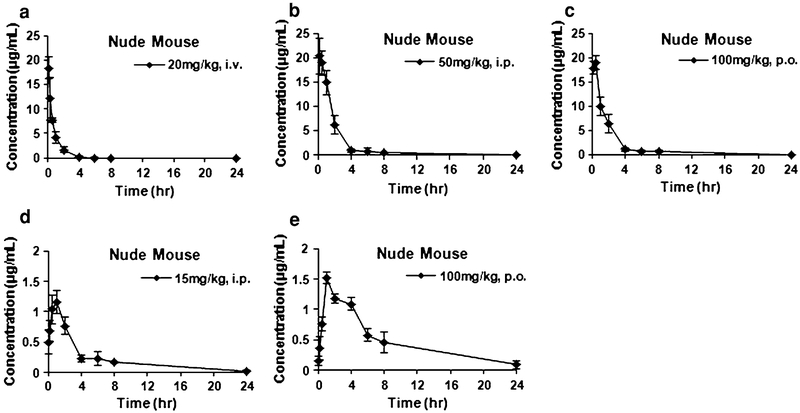

Initial pharmacokinetics of ML-970 in nude mice

Based on the MTDs of the compound and the effective doses reported [1, 4], we first evaluated the pharmacokinetics of ML-970 in PEG400/EtOH/Tween 80/D5 W at an intravenous (i.v.) dose of 20 mg/kg, an intraperitoneal (i.p.) dose of 50 mg/kg, or an oral dose of 100 mg/kg. We observed that the intact compound was still detectable in plasma 8 h after intravenous administration (Fig. 3a). The compound reached its highest plasma concentration by 10 min after administration when the compound was given i.p. injection, but reached its highest plasma concentration after 30 min when given by oral gavage. Intact ML-970 could still be detected 24 h after dosing by both i.p. and p.o. routes (Fig. 3b, c). We monitored urinary and fecal excretion of the compound when it was given by i.v. injection and observed that there was minimal excretion of the parent compound, with less than 0.5% of the compound being excreted in urine during the first 48 h following administration, and only about 1% (1.14%) being excreted in the feces during this same time period. Studies examining the excretion of a higher dose (40 mg/kg i.v. administered to CD-1 mice) confirmed this finding and showed that only approximately 1% of the compound was excreted in urine during the 48 h after treatment, and less than 0.1% of the parental ML-970 was excreted in feces during the first 8 h after administration. These results indicate that ML-970 may be taken up and remained in tissues for a prolonged time. Therefore, in subsequent studies, tissue distribution was studied in detail.

Fig. 3.

Concentration–time curves of the distribution of ML-970 in nude mouse plasma after administration of a 20 mg/kg by i.v. injection, b 50 mg/kg by i.p. injection, c 100 mg/kg by oral gavage in the solution formulation (PEG400/Tween 80/Ethanol/Saline), d 15 mg/kg by i.p. injection, and e 100 mg/kg by oral gavage in the suspension formulation (0.05% Tween 80/Saline)

Initial efficacy studies had examined administration of ML-970 in both a soluble formulation (PEG400/EtOH/Tween 80/D5 W as used above) and a suspension formulation (using 5% Tween 80/Saline). These studies showed that the suspension formulation of ML-970 had diminished antitumor efficacy compared to when the same dose was administered in the soluble formulation [1, 4]. To determine whether the differences in activity were due to the pharmacokinetics of the compound in the different formulations, we evaluated the i.p. (15 mg/kg) and p.o. (100 mg/kg) pharmacokinetics of ML-970 when it was administered in the suspension formulation (Fig. 3d, e). Confirming that the lack of efficacy was likely due to decreased availability of the compound to the tumor, the suspension formulation showed a lower plasma Cmax, lower AUC, and a higher clearance than the soluble formulation.

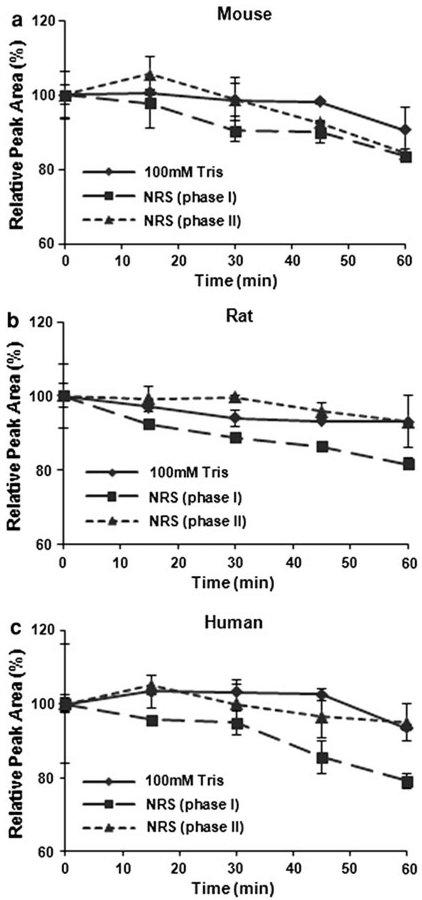

S9 metabolism study

Given the low urinary and fecal excretion of the compound, the low concentrations of intact compound in the plasma, and a wide distribution in various tissues within a few hours of administration, we hypothesized that ML-970 may be metabolized after administration. We screened the potential mechanisms responsible for ML-970 degradation using in vitro preparations of S9 fractions and determined the extent of metabolism by phase I and phase II enzymes. The studies indicated that the compound has a relatively long half-life in the presence of the microsomal enzymes (no significant loss of the parent compound was detected within an hour of incubation with the enzymes). There was a small, time-dependent decrease in the amount of ML-970 observed during these preliminary studies, suggesting that ML-970 may be metabolized by phase I (oxidation) enzymes in rats and humans, and both phase I and II enzymes in mice (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Metabolism of ML-970 by phase I and phase II S9 microsomal enzymes from mice (a), rats (b), and humans (c)

Further pharmacokinetic studies of ML-970 in the solution formulation

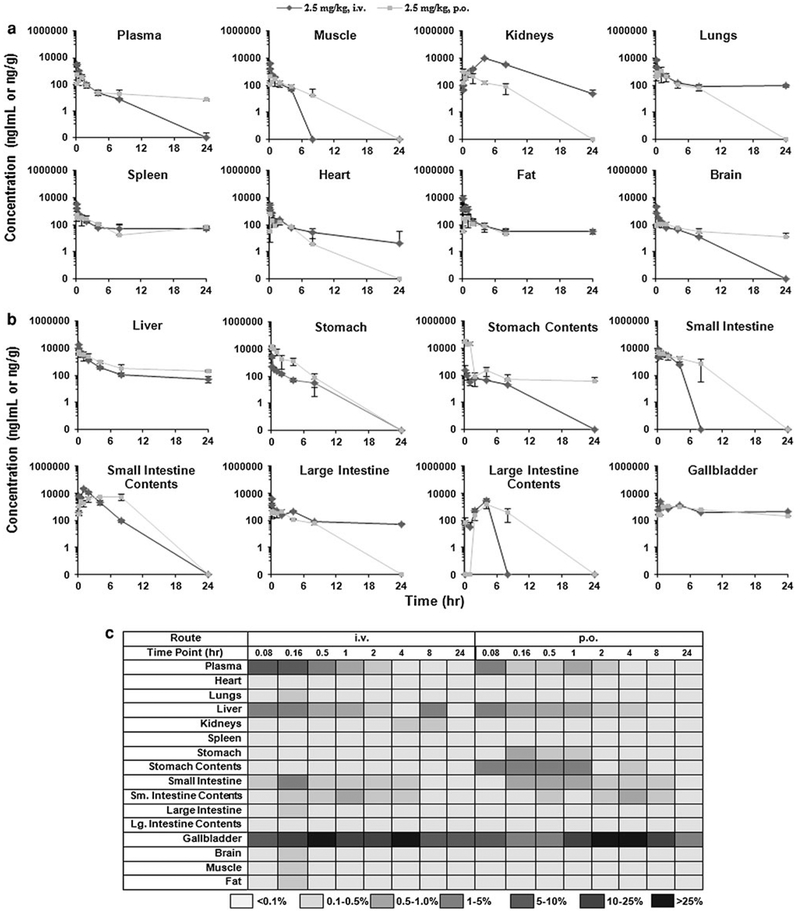

Further in vivo studies efficacy studies had indicated that the compound was effective at much lower doses. To evaluate the low-dose pharmacokinetics and accomplish a more in-depth study of the disposition of ML-970, we carried out in-depth pharmacokinetic studies of the compound administered intravenously via a tail vein or orally to female CD-1 mice at a single dose of 2.5 mg/kg (i.v. and p.o.). Blood and extensive tissue samples were collected at various time points to determine whether the compound was undergoing enterohepatic circulation. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the plasma pharmacokinetic parameters obtained during the various pharmacokinetic studies in mice. Figure 5a, b shows the distribution of the compound when it was administered at low doses, and Fig. 5c shows the percentage of the initial dose present in the various tissues at each time point. These data indicate that ML-970 undergoes enterohepatic circulation, keeping it from being excreted.

Table 1.

Summary of plasma pharmacokinetic parameters for ML-970 administered to nude mice

| Formulation | 0.05% Tween 80/Saline | PEG400/EtOH/Tween 80/D5W | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Route | i.p. | p.o. | i.p. | p.o. | i.v. |

| Dose (mg/kg) | 15 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 20 |

| Parameters | |||||

| Cmax (μg/ml) | 1.16 | 1.52 | 20.39 | 18.93 | 22.35 |

| Tmax (h) | 1 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.5 | 0 |

| AUC0~∞ (μg h ml−1) | 5.35 | 11.52 | 42.11 | 39.63 | 14.89 |

| T1/2 (h) | 6.14 | 6.73 | 4.58 | 4.26 | 0.78 |

| MRT (h) | 6.21 | 8.1 | 2.5 | 2.82 | 0.87 |

| CL or CL/F (ml g−1 h−1) | 2.67 | 8.07 | 1.19 | 2.52 | 1.35 |

| Vss (ml g−1) | – | – | – | – | 1.18 |

| Foral | – | – | 1.13 | 0.53 | – |

Cmax maximum concentration of the compound observed, Tmax time when the maximum concentration was observed, AUC area under the concentration–time curve, T1/2 half-life of the compound, MRT mean residence time, CL clearance, Vss volume in steady state, Foral oral bioavailability

Table 2.

Summary of plasma pharmacokinetic parameters for ML-970 administered to CD-1 mice

| Formulation | PEG400/EtOH/Tween 80/D5W | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Route | i.v. | p.o. | p.o. |

| Dose (mg/kg) | 2.5 | 2.5 | 5 |

| Parameters | |||

| Cmax (μg/ml) | 4.34 | 0.55 | 0.99 |

| Tmax (h) | 0 | 0.08 | 0.5 |

| AUC0~∞ (μg h ml−1) | 1.96 | 0.85 | 1.73 |

| T1/2 (h) | 0.31 | 10.73 | 2.97 |

| MRT (h) | 2.76 | 8.28 | 1.8 |

| CL or CL/F (ml g−1 h−1) | 1.27 | 2.61 | 3.22 |

| Vss (ml g−1) | 3.52 | – | – |

| Foral | – | 0.43 | 0.44 |

Cmax maximum concentration of the compound observed, Tmax time when the maximum concentration was observed, AUC area under the concentration–time curve, T1/2 half-life of the compound, MRT mean residence time, CL clearance, Vss volume in steady state, Foral oral bioavailability

Fig. 5.

Distribution of ML-970 to mouse plasma and various tissues following administration of 2.5 mg/kg by i.v. injection and 2.5 mg/kg by oral gavage a, and distribution of ML-970 to hepatobiliary and gastrointestinal tissues and luminal contents after administration of 2.5 mg/kg by i.v. injection, and 2.5 mg/kg by oral gavage (b) in the solution formulation, c percentage of the initial dose of ML-970 present in plasma, various tissues, and luminal contents following i.v. or p.o. administration to CD-1 mice

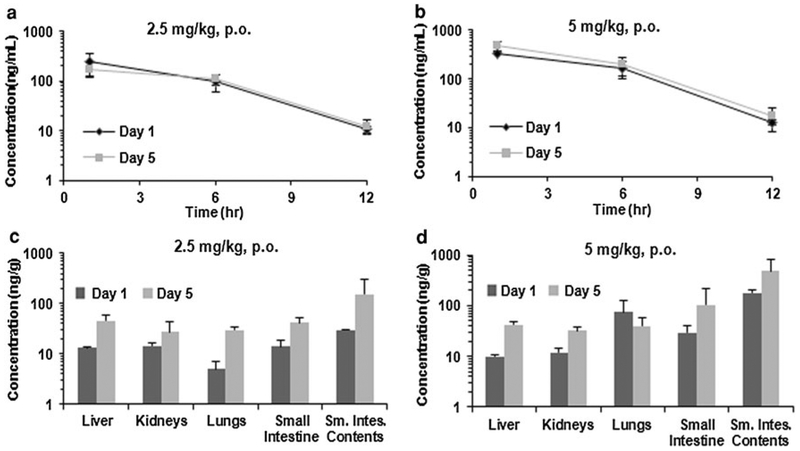

Preliminary rat pharmacokinetics

We also analyzed samples of plasma and various tissues collected from Sprague–Dawley rats administered either a single oral dose of ML-970 (2.5 and 5 mg/kg) or oral doses of ML-970 once per day for 5 days (2.5 and 5 mg/kg) in ((PEG400/EtOH/Tween 80 = 6:3:1)/D5 W = 1:2). Plasma samples were collected 1, 6, and 12 h post-administration, and tissue samples were collected at 12 h on days 1 and 5 to determine the distribution in rats. As shown in Fig. 6, tissue concentrations increased with time (Day 1 vs. Day 5), but there was no significant difference in tissue concentrations between two doses. The exception was intestine that showed increased concentration in a time- and dose-dependent manner. These results indicate it is possible that there is an enterohepatic circulation for the drug (and metabolites) and that GI is a major elimination route of the drug and metabolites. This may explain why there is no obvious tissue communication of ML-970 in non-GI tissues.

Fig. 6.

Distribution of ML-970 in a rat plasma at 1, 6, and 12 h after administration of a single dose, or after oral administration of the fifth daily dose of 2.5 or 5 mg/kg of ML-970; and b rat tissues and luminal contents 12 h after administration of a single dose or the fifth daily oral dose of 2.5 or 5.0 mg/kg ML-970

Discussion and conclusion

Although numerous agents are evaluated in the clinic each year as potential cancer therapeutics, few obtain FDA approval. There is an increasing trend toward deciding the fate of new agents earlier in development (preclinical or early phase I studies) in order to decrease the cost of drug development and the exposure of patients to toxic or ineffective drugs [8]. As such, even greater emphasis is being placed on examining potential issues with delivery, distribution, and toxicity than ever before. The present study was designed to evaluate various characteristics of the novel CC-1065/duocarmycin analog, ML-970, with regard to its stability in plasma, distribution following administration by different routes, and possible degradation and metabolic pathways.

Although animal models are imperfect for predicting human toxicity and biodistribution, there is a relatively high level of correlation between results obtained during preclinical studies and in human trials, and allometry is at the heart of determining the first dose to be administered in a clinical trial [9–11]. With this in mind, we evaluated the stability of ML-970 in mouse plasma, examined its plasma protein binding, accomplished studies of its possible metabolism by S9 microsomal enzymes, and determined its pharmacokinetic parameters in two of the most common animal models used for preclinical drug development (mice and rats).

During the evaluation of the metabolism of ML-970 by murine and human hepatic S9 microsomal fractions, we observed modest degradation of the compound. Our initial data suggest that ML-970 may be metabolized by phase I or II metabolic enzymes in different species. Based upon these results and tissue distribution results, we speculate that the compound (and its metabolites) may be accumulated in gastrointestinal tract and undergo enterohepatic circulation. Further studies on identification of those possible metabolites are needed.

Perhaps explaining the minimal S9 metabolism and the low urinary and fecal excretion, we observed that the compound appears to undergo enterohepatic circulation. Our study investigated the pharmacokinetic profile of ML-970 following both i.v. (2.5 mg/kg) and p.o. (2.5 mg/kg) administration in mice. We found high levels of ML-970 in the liver, gallbladder, and small intestine (Fig. 5), and the levels in these tissues, especially the liver and gallbladder, remained relatively high for at least 24 h. This may also explain the decreased myelotoxicity observed for ML-970 compared to its related analogs [1, 4]. The rat preliminary pharmacokinetic results showed that tissue concentrations increased in a time-dependent manner, but there were no significant differences in accumulation for most tissues (except intestines and intestinal contents) between two doses tested. The results indicate that ML-970 accumulates with repeated administration, and it is possible that there is an enterohepatic circulation and GI is a major elimination route of the agent and metabolites. Further studies are needed to test these hypotheses.

Of note, the HPLC method was developed and validated for the analyses of intact ML-970. This method apparently was not affected by its possible metabolites, based on our standard cures with specific tissues and analyses of tissue samples from in vivo pharmacokinetic studies. However, we realize that this method could not identify metabolites. To facilitate the metabolic studies of the drug, further efforts should include method development and validation for identification of possible metabolites of the drug.

Another important point is the relations between the observed pharmacokinetics and the drug efficacy and toxicity. Overall, previous studies have demonstrated the antitumor activity of ML-970 against the different human cancer cell lines in vitro and in vivo [1, 4]. A wide range of ML-970 doses have been used in these in vivo studies [1, 4]. In MDA-MB-435 breast cancer xenograft models, ML970 inhibited tumor growth at all the oral doses (70–280 mg/kg) and i.v. dose (10 mg/kg), and no weight loss (a sensitive index for host toxicity) was observed at any of these doses and routes of administration. Based on efficacy and MTDs results, we first evaluated the pharmacokinetics of ML-970 with a broad range of doses (from 10 to 100 mg/kg) in both soluble and suspension formulations. We did not observe any toxicity under these conditions. Further efficacy studies indicated that the compound was effective at much lower doses (data not shown); therefore, lower doses (2.5 and 5 mg/kg) were used in subsequent pharmacokinetic studies. In fact, our data indicate that even lower doses (B10% of the MTD) should be effective against tumors located in various organs, because these tissues all exhibited concentration values above 34 nM (GI50 of ML-970 in vitro). Taken together, our findings, alongside previous reports, indicate that ML-970 may be administered at low dose, leading to significant anticancer activity and minimal or no side effects. Further studies should examine its unique pharmacokinetic properties, including the enterohepatic circulation, minimal excretion of intact compound through urine or feces, and tissue-specific accumulation. It is also worthy investigating whether any metabolites of ML-970 are active against cancer cells.

In conclusion, ML-970 is a relatively stable compound and has unique pharmacokinetic profiles. Based on available data on ML-970’s anticancer activity and safety profiles, we conclude that it has potential for human cancer therapy. Further investigations to optimize the formulation, dose, and dosing frequency are needed. Detailed metabolic studies of this drug and identification of possible metabolites will facilitate the preclinical and clinical studies of the drug. Moreover, additional long-term toxicity studies will also be needed, especially to determine whether the enterohepatic circulation affects its efficacy and toxicity. The methods developed and the preliminary results from the present study provided a basis for these studies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH NCI contract N01-CM-52207. We thank Dr. Silvana Grau, Dr. Scharri Ezell, and Ms. Charnell Sommers for excellent technical assistance, and Dr. Donald Hill for helpful discussion.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Rayburn, Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Cancer Pharmacology Laboratory, Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294, USA.

Wei Wang, Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Cancer Pharmacology Laboratory, Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294, USA; Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, 1300 Coulter Drive, Amarillo, TX 79106, USA; Cancer Biology Center, School of Pharmacy, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Amarillo, TX 79106, USA.

Mao Li, Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Cancer Pharmacology Laboratory, Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294, USA.

Haibo Li, Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Cancer Pharmacology Laboratory, Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294, USA.

Jiang-Jiang Qin, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, 1300 Coulter Drive, Amarillo, TX 79106, USA.

Moses Lee, Department of Chemistry, Hope College, Holland, MI, USA.

Ruiwen Zhang, Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Cancer Pharmacology Laboratory, Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294, USA; Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, 1300 Coulter Drive, Amarillo, TX 79106, USA; Cancer Biology Center, School of Pharmacy, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Amarillo, TX 79106, USA.

References

- 1.Sato A, McNulty L, Cox K, Kim S, Scott A, Daniell K, Summerville K, Price C, Hudson S, Kiakos K, Hartley JA, Asao T, Lee M (2005) A novel class of in vivo active anticancer agents: achiral seco-amino- and seco-hydroxycyclopropylbenz[e]indolone (seco-CBI) analogues of the duocarmycins and CC-1065. J Med Chem 48:3903–3918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacMillan KS, Lajiness JP, Cara CL, Romagnoli R, Robertson WM, Hwang I, Baraldi PG, Boger DL (2009) Synthesis and evaluation of a thio analogue of duocarmycin SA. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 19:6962–6965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toth JL, Trzupek JD, Flores LV, Kiakos K, Hartley JA, Pennington WT, Lee M (2005) A novel achiral seco-amino-cyclopropylindoline (CI) analog of CC-1065 and the duocarmycins: design, synthesis and biological studies. Med Chem 1:13–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiakos K, Sato A, Asao T, McHugh PJ, Lee M, Hartley JA (2007) DNA sequence selective adenine alkylation, mechanism of adduct repair, and in vivo antitumor activity of the novel achiral seco-amino-cyclopropylbenz[e]indolone analogue of duocarmycin AS-I-145. Mol Cancer Ther 6:2708–2718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agrawal S, Zhang X, Cai Q, Kandimalla ER, Manning A, Jiang Z, Marcel T, Zhang R (1998) Effect of aspirin on protein binding and tissue disposition of oligonucleotide phosphorothioate in rats. J Drug Target 5:303–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang H, Wang Z, Wang S, Li M, Nan L, Rhie JK, Covey JM, Zhang R, Hill DL (2005) Preclinical pharmacology of epothilone D, a novel tubulin-stabilizing antitumor agent. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 56:255–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H, Li M, Rhie JK, Hockenbery DM, Covey JM, Zhang R, Hill DL (2005) Preclinical pharmacology of 2-methoxyantimycin A compounds as novel antitumor agents. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 56:291–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ivy SP, Siu LL, Garrett-Mayer E, Rubinstein L (2010) Approaches to phase 1 clinical trial design focused on safety, efficiency, and selected patient populations: a report from the clinical trial design task force of the national cancer institute investigational drug steering committee. Clin Cancer Res 16:1726–1736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paxton JW (1995) The allometric approach for interspecies scaling of pharmacokinetics and toxicity of anti-cancer drugs. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 22:851–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernillon P, Bois FY (2000) Statistical issues in toxicokinetic modeling: a bayesian perspective. Environ Health Perspect 108(Suppl 5):883–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith DA, Obach RS (2009) Metabolites in safety testing (MIST): considerations of mechanisms of toxicity with dose, abundance, and duration of treatment. Chem Res Toxicol 22:267–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]