Abstract

IMPORTANCE

The incidence of syphilis in the United States is increasing; it is estimated that more than 55 000 new infections will occur in 2014. Treatment regimens are controversial, especially in specific populations, and assessing treatment response based on serology remains a challenge.

OBJECTIVE

To review evidence regarding penicillin and nonpenicillin regimens, implications of the “serofast state,” and treatment of specific populations including those with neurosyphilis or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and pregnant women.

EVIDENCE REVIEW

We searched MEDLINE for English-language human treatment studies dating from January 1965 until July 2014. The American Heart Association classification system was used to rate quality of evidence.

FINDINGS

We included 102 articles in our review, consisting of randomized trials, meta-analyses, and cohort studies. Case reports and small series were excluded unless they were the only studies providing evidence for a specific treatment strategy. We included 11 randomized trials. Evidence regarding penicillin and nonpenicillin regimens was reviewed from studies involving 11 102 patients. Data on the treatment of early syphilis support the use of a single intramuscular injection of 2.4 million U of benzathine penicillin G, with studies reporting 90% to 100% treatment success rates. The value of multiple-dose treatment of early syphilis is uncertain, especially in HIV-infected individuals. Less evidence is available regarding therapy for late and late latent syphilis. Following treatment, nontreponemal serologic titers should decline in a stable pattern, but a significant proportion of patients may remain seropositive (the “serofast state”). Serologic response to treatment should be evident by 6 months in early syphilis but is generally slower (12-24 months) for latent syphilis. Evidence defining treatment for HIV-infected persons and for pregnant women is limited, but available data support penicillin as first-line therapy.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

The mainstay of syphilis treatment is parenteral penicillin G despite the relatively modest clinical trial data that support its use.

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. First described after European explorers returned from the Americas at the end of the 15th century, syphilis has been a major cause of morbidity and mortality for more than 500 years. Its clinical influence was profoundly diminished by the introduction of penicillin in the 1940s. After declining to a historic low in the year 2000, the number of syphilis cases in the United States has been increasing and now exceeds 55 000 new cases each year.1 Penicillin has been the treatment of choice for more than half a century, but questions regarding the appropriate therapeutic regimen for various stages of syphilis still exist. Because T pallidum cannot be cultured, there is no gold standard by which to assess cure. Instead, indirect means (changes in titer of syphilis serology) must be used, contributing to inconsistencies among studies and complicating the task of drawing evidence-based conclusions.

Public Health Consequences

Syphilis is an important public health problem. Timely diagnosis and prompt treatment are important to limiting its clinical effects. Untreated, up to one-third of patients progress to later stages of disease.2 Late syphilis can cause irreversible damage to the cardiovascular and central nervous systems, resulting in profound morbidity and even death. Without adequate screening and treatment, stillbirth, neonatal death, low birth weight, prematurity, and congenital syphilis may affect more than half of pregnancies among women with syphilis.3,4 In addition, genital ulcers due to syphilis have been linked to acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.5

Epidemiology and At-Risk Populations

In recent years, an increasing proportion of syphilis cases in the United States have been diagnosed in men who have sex with men (MSM), often associated with high-risk sexual behavior and HIV coinfection.6 In 2013, more than 16 000 of the total reported cases were primary and secondary syphilis, the most transmissible stages of infection, and three-quarters of these occurred in MSM.6 The highest rates of primary and secondary syphilis are currently found in younger men (aged 20-29 years), a change since 2006, when those aged 35 to 59 years were most affected. Primary and secondary syphilis disproportionately affect black men, whose infection rate (27.9 per 100 000) is more than 5-fold higher than the rate among white men (5.4 per 100 000).1

Stages of Syphilis

Syphilis occurs in overlapping stages, classified according to symptoms and time since initial infection (Table 1). Appropriate staging is important for determining infectivity and treatment duration. A diagnosis of early syphilis (primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis) implies that T pallidum infection occurred within the previous year.9 Late syphilis represents manifestations occurring more than 1 year and even decades after initial infection. Latent syphilis refers to T pallidum infection with reactive syphilis serologic findings but without clinical manifestations of disease. It includes both early latent (within 1 year of infection) and late latent (1 year or more after infection) syphilis.

Table 1.

Stages of Syphilisa

| Syphilis Stage | Timing | Symptoms | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early syphilis (occurs within 1 year of infection) | |||

| Primary | 2-4 wk after exposure (median, 21 d) | Painless chancre, usually on the genitalia; can also occur on the perineum, anus, rectum, lips, oropharynx, or hands; may be asymptomatic. | Chancre usually clears spontaneously but widespread spirochete dissemination occurs during this stage |

| Secondary | 2-8 wk after disappearance of chancre | Wide range of systemic symptoms including rash, fever, headache, pharyngitis, and lymphadenopathy; may be asymptomatic | Rash is usually truncal and maculopapular, frequently involving the palms and soles Condyloma lata (grayish white warty lesions) may be seen, usually on genital mucosa |

| Early latent | Acquisition of syphilis within the preceding year | None | Diagnosis requires (within the previous year) documented seroconversion or ≥4-fold increase in nontreponemal titer, documented seroconversion of a treponemal test, sexual exposure to a person with early syphilis, or only sexual contact was within the last 12 mo (sexual debut)9 |

| Tertiary (late; includes neurosyphilis [see below], cardiovascular, and gummatous disease) | Occurs >1 y to decades after primary infection | Cardiovascular system involvement including dilated aorta, aortic regurgitation, or carotid ostial stenosis; gummas (granulomatous lesions) form on skin, bones, or within organs | Cardiovascular disease often as a result of vasculitis of the vasa vasorum of the ascending thoracic aorta |

| Latent syphilis (asymptomatic infection with normal physical examination findings in association with reactive serologic findings) | |||

| Early latent | See above | See above | |

| Late latent | Diagnosis of syphilis >1 y after infection or of unknown duration | None | Cases not meeting above criteria for early latent syphilis and cases of infection at unknown time point are considered late latent syphilis |

| Neurosyphilis (infection of central nervous system by Treponema pallidum, further defined as early or late neurosyphilis) | |||

| Early neurosyphilis | Occurs <1 y after initial infection, usually within weeks of exposure | Usually involves the meninges and vasculature: meningitis, cranial nerve defects, meningovascular disease, or stroke | May present simultaneously with symptoms of primary or secondary syphilis |

| Late neurosyphilis | Occurs >1 y after initial infection, even decades after primary infection | Usually involves the brain and spinal cord: disorders such as general paresis, dementia, or tabes dorsalis | Much less common in current period |

| Serofast state | Following treatment | None; patients have achieved clinical cure | Nontreponemal antibodies decline but do not completely revert to nonreactive |

Methods

One of us (M.E.C.) searched MEDLINE for English-language human treatment studies dating from January 1965 through July 2014. The initial search was limited to clinical trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses consisting of syphilis treatment studies. We excluded articles involving only diagnostic testing, screening, or prevention. Reference lists of identified articles were searched for additional relevant references (eFigure in the Supplement). Case reports and series were not included unless they were the only studies providing evidence for a specific treatment strategy. The American Heart Association classification of recommendations was used to grade the quality of evidence (Table 2). Grade A indicates data from many large randomized clinical trials (RCTs); grade B, data from fewer, smaller RCTs, careful analyses of nonrandomized studies, or observational registries; and grade C, expert consensus.29

Table 2.

Evidence for Therapy for Each Syphilis Stage

| Syphilis Stage | Primary Therapy | Grade of Evidence of Primary Therapya |

Alternative Therapy | Grade of Evidence of Alternative Therapya |

Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early syphilis (primary, secondary) | BPG, 2.4 million U intramuscularly in 1 dose | A10-12 | Doxycycline, 100 mg twice daily for 14 d | B13-19 | Clinical and serologic examinations at 6 and 12 mo |

| Ceftriaxone, 1-2 g/d intramuscularly or intravenously for 10-14 d | B16,20-23 | ||||

| Tetracycline, 100 mg orally 4 times daily for 14 d | B13,15 | ||||

| Azithromycin, single 2-g dose, only if all other options not feasible | A11,12,24-27b | ||||

| Early latent syphilis | BPG, 2.4 million U intramuscularly in 1 dose | A10-12 | Nontreponemal serologic tests at 6, 12, and 24 mo | ||

| Late latent syphilis | BPG, 2.4 million U intramuscularly in 3 weekly doses | C | Doxycycline, 100 mg orally twice daily for 28 d | C | |

| Tetracycline, 500 mg orally 4 times daily for 28 d | C | ||||

| Tertiary syphilis (excluding neurosyphilis) | BPG, 2.4 million U intramuscularly in 3 weekly doses | C | |||

| Neurosyphilis | Aqueous penicillin G, 18 million-24 million U/d intravenously (every 4 h or as continuous infusion) for 14 d | C | Procaine penicillin, 2.4 million U/d intramuscularly, plus probenecid, 500 mg orally 4 times daily, for 10-14 d | Repeat cerebrospinal fluid analysis every 6 months until cell count is normal if pleocytosis is initially present | |

| Ceftriaxone, 2 g/d intramuscularly or intravenously for 10-14 d | |||||

| HIV coinfection | Same as HIV uninfected | C10 | Clinical and serologic examinations at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 mo | ||

| BPG, 2.4 million U intramuscularly in 3 weekly doses for early syphilis | C28 |

Abbreviations: BPG, benzathine penicillin G; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Grade A indicates data from many large randomized clinical trials (RCTs); grade B, data from fewer, smaller RCTs, careful analyses of nonrandomized studies, or observational registries; and grade C, expert consensus.29

Grade A due to large RCTs; however, azithromycin is used only when other options are not feasible because of macrolide resistance.

Results

Treatment of Syphilis

The MEDLINE search for syphilis treatment identified 418 articles, of which 40 were included in this review. After reviewing the reference lists of these articles for additional relevant studies, we identified 102 articles for inclusion in our review, including RCTs, meta-analyses, and cohort studies. In total, the review included 11 randomized trials, and the evidence regarding penicillin and nonpenicillin regimens was reviewed from studies involving 11 102 patients (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3.

Evidence for Penicillin Treatment of Syphilis

| Source | Study Design |

Participants | Treatment | Dosing Regimens | Outcome Measure and Definitions |

Results | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rolfs et al,10 1997 | Randomized clinical trial | 139 patients with primary, 253 with secondary, and 149 with early latent syphilis (100 with history of syphilis) | 276 treated with BPG and 265 with enhanced therapy | BPG: 2.4 million U IM as 1 dose Enhanced therapy: BPG, 2.4 million U IM in 1 dose plus 2 g amoxicillin and 500 mg probenecid orally 3 times daily for 10 d |

Treatment success: negative or ≥ 4-fold decrease in RPR titer | Treatment failure: 18% with usual therapy and 17% with enhanced therapy at 6 mo; 15% with usual therapy and 14% with enhanced therapy at 12 mo | 1-y follow-up (52% retained in study) 101/541 (19%) HIV infected |

| Talwar et al,30 1992 | Retrospective study | 1532 patients with early syphilis with 30 mo of follow-up: 1008 with primary, 429 with secondary, and 95 with latent (defined as <2 y of infection) | 1386 treated with BPG, 17 with procaine penicillin, and 139 with broad-spectrum antibiotics | BPG: 2.4 million U IM as 1 dose, 4.8 million U IM weekly as 2 doses Procaine penicillin: 0.6 million U/d for 10 d Broad-spectrum antibiotics at various dosages |

Patients followed up for serial VDRL measurements at 2-mo intervals for first 6 mo, 3-mo intervals for the next year, and 6-mo intervals for the next year | Reactive VDRL test result in 16.5% and 6.6% (primary), 27.6% and 8.4% (secondary), and 18.9% and 11.6% (early latent) at 6 and 30 mo, respectively Results for secondary and early latent syphilis were better with 4.8 million U of BPG and procaine penicillin | 30-mo surveillance period |

| Fiumara,311986 | Retrospective study | 88 patients with primary and 101 with secondary syphilis When combined with previous series, 588 with primary and 623 with secondary syphilis |

All treated with BPG | BPG: 2.4 million U IM weekly as 2 doses | Patients followed up until lesions or rash healed and test results (RPR and FTA-ABS) became negative | 88/88 with primary syphilis seronegative at 12 mo; 101/101 with secondary syphilis seronegative at 2 years | 2-y follow-up Excluded patients with ≥4-fold increase in RPR after lesions had healed or after titer had decreased ≥4-fold, considered to have been reinfected No control group |

| Durst et al,32 1973 | Prospective study | 40 patients with secondary syphilis | All treated with BPG | BPG: 6.0 million U total (2.4 million U as 1 dose initially, then 2.4 million U IM as 1 dose within 5 d, then 1.2 million U IM as 1 dose within 3-5 d) | Patients followed up until serologic test results became negative | At 12 mo: 17/40 seronegative; at 18 mo: 33/40 seronegative; at 24 mo: 40/40 seronegative | 2-y follow-up No control group |

| Jefferiss and Willcox,33 1963 | Presumed retrospective study | 211 patients with seronegative primary, 179 with seropositive primary, 196 with secondary, and 50 with early latent syphilis | 107 treated with benzyl penicillin, 7 with benzyl penicillin plus BPG, 231 with procaine penicillin or PAM, and 291 with high-dose APPG ± PAM | Benzyl penicillin: “repeated injections” of 2.5 to 5 million U BPG: unspecified dose as 1 or 2 injections Procaine penicillin: 5.1-10 million U High-dose APPG: >10 million U PAM at varied dosing of injections |

Patients followed up with clinical and serologic examinations monthly for 6 mo, quarterly for 1 year, and twice per year for second year | 95% with negative VDRL test result 22 mo after treatment | Followed up for 30 mo; 238/636 (37.4%) followed up at 22-30 mo No distinction between reinfection/relapse, but low rates of both (cumulative re-treatment rate of 4.42%) |

| Smith et al,34 1956 | Presumed retrospective study | 52 patients with seronegative primary, 67 with seropositive primary, and 155 with secondary syphilis | 52 with seronegative primary, 67 with seropositive primary, and 155 with secondary infection treated with BPG, 2.5 million U as single injection 166 with secondary infection treated with PAM as 1 session 415 with secondary infection treated with PAM as 2-4 sessions | BPG: 2.5 million U IM as 1 dose PAM: 4.8 million U in a single session or 2-4 sessions |

Patients followed up according to percentage seronegative (negative or less than 4 Kahn units) | Seronegative at 2 y after BPG: 100% with seronegative primary, 96.0% with seropositive primary, and 94.5% with secondary syphilis Seronegative at 2 y after PAM: 91.0% with single-dose and 88.3% with divided-dose regimens | 2-y follow-up |

| Sternberg and Leifer,35 1947 | Retrospective study | 1400 patients with early syphilis: 600 (42.8%) seronegative primary, 564 (40.3%) with seropositive primary, and 236 (56.4%) with secondary syphilis | Sodium penicillin in aqueous solution or isotonic sodium chloride | 2.4 million U penicillin delivered over 7.5 d | “Satisfactory progress”: no signs of clinical relapse and serologic test results became/remained negative during the observation period “Unsatisfactory progress”: relapse or reinfection |

Seronegative primary syphilis: 86% followed up >9 mo; satisfactory progression in 566 (94.3%) Seropositive primary syphilis: 82% followed up >9 mo; satisfactory progression in 507 (89.9%) Secondary syphilis: 84% followed up >9 mo; satisfactory progress at last observation in 196 (83%) |

1-y follow-up No distinction of penicillin type; noted “patients were probably treated with penicillins of satisfactory potency” No control group |

Abbreviations: APPG, aqueous procaine penicillin G; BPG, benzathine penicillin G; FTA-ABS, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IM, intramuscularly; PAM, penicillin aluminum monostearate; RPR, rapid plasma reagin; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory.

Table 4.

Evidence for Antibiotics Other Than Penicillin for Treatment of Syphilis

| Source | Study Design |

Participants | HIV Status | Treatment and Dosing Regimens |

Outcome Measures, Definitions, and Comments |

Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline/tetracycline | ||||||

| Li and Zheng,13 2014 | Retrospective cohort | 641 patients with early syphilis (13.4% primary, 52.1% secondary, and 34.5% early latent) | Excluded HIV-infected patients | 606 (94.5%) treated with BPG, 2.4 million U IM weekly as 2 doses, and 35 (5.5%) with doxycycline, 100 mg twice daily for 14 d, and tetracycline, 500 mg 4 times daily for 14 d | Serologic response: negative or ≥4-fold decrease in RPR or serofast (±1 dilution from baseline if RPR was 1:2 or 1:1 at baseline) by 6 mo | No significant difference in serologic response rates: 91.4% of penicillin vs 82.9% of doxycycline/tetracycline; P = .16 |

| Psomas et al,16 2012 | Retrospective | 116 patients with early syphilis | 80% HIV infected | 52 treated with BPG, 2.4 million U IM weekly as 1-3 doses, 49 with ceftriaxone, 1-2 g/d for 14-21 d, and 15 with doxycycline, 100 mg twice or 3 times daily for 14-21 d | Serologic response: ≤1:4 VRDL titer Relapse: 4-fold increase in VDRL or increase to >1:4 |

Responses: penicillin, 39/52 (75%); ceftriaxone, 38/49 (77.6%); doxycycline, 11/15 (73.3%) No significant difference in time to serologic response per treatment (log-rank test, P = .90) |

| Wong et al,15 2008 | Retrospective | 445 primary syphilis cases | Excluded diagnosed HIV-infected patients but many had unknown HIV status | 420 (94.4%) treated with BPG, 2.4 million U IM as 1 dose, and 25 (5.6%) with doxycycline/tetracycline, 100 mg twice daily for 14 d | Serologic response:≥4-fold decrease in RPR by 6 mo, ≥8-fold by 12 mo, ≥16-fold by 24 mo, or serofast (±1 dilution from baseline if RPR was 1:4, 1:2, or 1:1 at baseline) Failure: none of the above or ≥4-fold increase in RPR at 1-6 mo |

No significant difference in serologic response rates: 409/420 (97.4%) of BPG vs 25/25 (100%) of doxycycline/tetracycline |

| Ghanem et al,14 2006 | Retrospective case-control | 1558 patients with early syphilis | 13.7% HIV positive in BPG vs 5.9% in doxycycline groups | 34/87 treated with doxycycline/tetracycline, 100 mg twice daily for 14 d, met inclusion criteria and were compared with 73 randomly selected patients treated with BPG, 2.4 million U IM as 1 dose | Serologic failure: 4-fold increase in RPR 30-400 d posttreatment or lack of 4-fold decrease in RPR 20-400 d posttreatment | 4/73 with serologic failure in BPG group vs 0/34 in doxycycline group |

| Long et al,17 2006 | Prospective cohort | 96 patients with syphilis; 76 returned for 1-y follow-up Syphilis stage undefined | 15/96 had HIV infection | 58 treated with BPG, 2.4 million U IM as 1 dose, and 18 with doxycycline, 100 mg twice daily for 14 d if penicillin allergy | Serologic response: negative or ≥4-fold decrease in RPR by 12 mo Reinfection: success then subsequent 4-fold increase in RPR from its lowest level or conversion to reactive Failure: no 4-fold decline in RPR or failure to convert a 1:4 or 1:2 titer to nonreactive No relapse group |

No significant difference in serologic response rates: 94.8% of BPG vs 88.9% of doxycycline; odds ratio, 2.29; 95% CI, 0.17-21.60; P = .59 |

| Schroeter et al,36 1972 | Prospective | 586 patients with early syphilis | NA | 100 treated with BPG, 2.4 million U IM as 1 dose, 101 with PAM, 4.8 million U, 61 with APPG, 4.8 million U (0.6 million U/d for 8 d), 107 with tetracycline, 30 g (3 g/d ×10 d), and 144 with erythromycin, 30 g | Cure: healed clinical manifestations, prompt and permanent decrease of VDRL Relapse: reappearance of lesions with dark field or significant increase in VDRL Failure: lack of significant response of VDRL after 1 y |

Cumulative re-treatment at 24 mo: BPG, 11.4%; PAM, 10.9%; APPG,10.7%; tetracycline, 12.7%; erythromycin, 21.3% |

| Ceftriaxone | ||||||

| Psomas et al,16 2012 | Retrospective | 116 patients with early syphilis | 80% HIV infected | 52 treated with BPG, 2.4 million U IM as 1-3 doses, 49 with ceftriaxone, 1-2 g daily for 14-21 d, and 15 with doxycycline, 100 mg twice or 3 times daily for 14-21 d | Serologic response: ≤1:4 VRDL titer Relapse: 4-fold increase in VDRL or increase to >1:4 |

Responses: penicillin, 39/52 (75%); ceftriaxone, 38/49 (77.6%); doxycycline, 11/15 (73.3%) No significant difference in time to serologic response per treatment (log-rank test, P = .90) |

| Spornraft-Ragaller et al,20 2011 | Retrospective | 24 patients with active syphilis (21 with primary syphilis; 3 with neurosyphilis) | All patients HIV infected | 12 treated with ceftriaxone, 1-2 g intravenously for 10-21 d, and 12 with high-dose penicillin G (8 with BPG, 2.4 million U/wk as 2-3 doses, 2 with clemizole penicillin G, 1 million U/d for 14-21 d, and 2 with intravenous penicillin G, 3 × 10 million U/d for 21 d) | Serologic response: negative or ≥4-fold decrease in VDRL | 11/12 with ceftriaxone and 12/12 with penicillin had >4-fold decline in VDRL titers at median of 18.3 mo |

| Smith et al,37 2004 | Prospective randomized pilot | 31 patients with asymptomatic syphilis randomized to procaine penicillin or ceftriaxone Most thought to have late latent syphilis |

All patients HIV infected; enrolled before availability of effective antiretroviral therapy | 10 treated with procaine penicillin, 2.4 million U IM, plus oral probenecid and 14 with ceftriaxone, 1 g/d for 15 d (only 24 followed up) | Serologic response: ≥4-fold decrease in RPR Relapse: ≥4-fold increase in RPR, persistent titer ≥1:64, or clinical progression of disease Nonresponse: ≤2-fold change in RPR Serofast: persistent titer after treatment |

Penicillin: 7/10 had response (2/10 had subsequent relapse), 3/10 were serofast Ceftriaxone: 10/14 with response (1/14 had subsequent relapse), 2/14 were serofast, 2/14 failures |

| Dowell et al,38 1992 | Secondary | 7 patients with neurosyphilis, 6 with latent syphilis, and 30 with presumed latent syphilis | All patients HIV infected | 43 treated with ceftriaxone,1-2 g/d for 10-14 d, and 13 with BPG, 2.4 million U IM as 3 weekly doses | Serologic response: ≥4-fold decrease in RPR with no subsequent increase Relapse: ≥4-fold rise in RPR after ≥4-fold decline Failure: ≥4-fold RPR increase without initial response, persistent RPR ≥1:64, or clinical progression Serofast: persistent titer after treatment with no signs of progressive disease |

Ceftriaxone: 28 (65%) had response, 5 (12%) were serofast, 9 (21%) had serologic relapse, 1 (2%) progressed to neurosyphilis BPG: 8 (62%) had response, 1 (8%) was serofast, 2 (15%) had relapse, and 2 (15%) had failures All followed up for ≥6 mo |

| Schöfer et al,21 1989 | Randomized prospective | 28 patients with early syphilis (9 primary, 19 secondary) | NA | 14 treated with ceftriaxone, 1 g IM 4 times daily every 2 d, and 14 with penicillin G, 1 million U/d IM for 15 d | Serological controls were repeated 1, 2, 3, 6, and 12 mo after therapy | All patients had ≥4-fold decrease in VDRL titer and resolution of clinical symptoms One adverse reaction in penicillin G group (rash); none in ceftriaxone group |

| Hook et al,22 1988 | Prospective | 11 patients with primary and 5 with secondary syphilis | NA | 10 treated with ceftriaxone, 250 mg/d for 10 d, and 6 with ceftriaxone, 500 mg every other day as 5 doses | Results reported at 3 mo | Daily treatment: 1/10 with VDRL persistently negative, 4/10 became seronegative, 5/10 had dilutions of ≥3 Every-other-day treatment: 1/6 became VDRL seronegative, 5/6 had dilutions of ≥2 Of 11 patients available for follow-up at 3-23 mo, there were no cases with evidence of relapse |

| Moorthy et al,23 1987 | Randomized | 18 patients with early syphilis | NA | 5 treated with ceftriaxone, 3 g as 1 dose, 5 with ceftriaxone, 2 g/d IM as 2 doses, 3 with ceftriaxone, 2 g/d IM as 5 doses, and 5 with BPG, 2.4 million U IM as 1 dose | Cure: clearance of lesions, nonreactive VDRL Sustained response: clearance of lesions, ≥4-fold decrease in VDRL by 3 mo and sustained at 12 mo Failure: clinical progression or ≥4-fold increase in VDRL |

Single 3-g ceftriaxone dose: 3/5 had cure, 1/5 had sustained response, 1/5 had failure 2 g ceftriaxone in 2 daily doses: 3/5 had cure, 2/5 had sustained response 2 g ceftriaxone in 5 daily doses: 3/3 had sustained response BPG: 3/5 had cure, 1/5 had sustained response, and 1 lost to follow-up Follow-up was at 1 y |

| Azithromycin | ||||||

| Bai et al,26 2012 | Meta-analysis | 790 patients with early syphilis | NA | 3 randomized clinical trials comparing BPG vs azithromycin in variable dosages | Serologic response: ≥4-fold decrease in RPR measured at 3, 6, 9, and 12 mo | No statistically significant difference between azithromycin and BPG treatment in odds of cure (odds ratio, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.69-1.56) 85.7% (341/398) response rate for azithromycin and 85.0% (333/392) for BPG |

| Hook et al,12 2010 | Randomized clinical trial | 517 patients with early syphilis: 26% primary, 46% secondary, 28% early latent primary, 46% early latent secondary, and 28% early latent | Excluded HIV-infected patients | 237 treated with BPG, 2.4 million U IM as 1 dose, and 232 with azithromycin, 2.0 g orally as 1 dose | Serologic response: negative or ≥4-fold decrease in RPR by 6 mo | Serologic response in 180/232 (77.6%) with azithromycin vs 186/237 (78.5%) with BPG Increased nonserious adverse events (mostly gastrointestinal) in azithromycin group |

| Bai et al,27 2008 | Meta-analysis | 476 patients with early syphilis | NA | 4 randomized clinical trials comparing BPG vs azithromycin in variable dosages | Serologic response: ≥4-fold decrease in RPR measured at 3, 6, 9, and 12 mo | 95.0% (227/239) response rate for azithromycin and 84.0% (199/237) for BPG Five times more gastrointestinal adverse effects of azithromycin vs BPG, but results not significant |

| Kiddugavu et al,25 2005 | Secondary analysis of randomized clinical trial (not randomized to therapy) | 11 patients (1.1%) with primary, 122 (13%) with secondary or early latent, and 818 (86%) with presumed late latent syphilis | 20.8% HIV infected | 18% treated with BPG alone, 2.4 million U IM as 1 dose, 17% with azithromycin alone, 1 g orally as 1 dose, and 65% with dual therapy All treated with single dose IM regardless of presumed stage of syphilis |

Serologic response: negative or ≥4-fold decrease in TRUST result by 10 mo | When initial titer >1:4, higher response rate with azithromycin alone and with dual treatment vs BPG alone No difference in response rates in analysis of lower initial titers or overall (56%-63% response rates) No difference in response rates between HIV infected and uninfected |

| Riedner et al,11 2005 | Randomized clinical trial | 25 patients with primary and 303 with high-titer latent syphilis | 52.1% HIV infected | 163 treated with azithromycin, 2.0 g orally as 1 dose, and 165 with BPG, 2.4 million U IM as 1 dose | Serologic response: ≥4-fold decrease in RPR titer at 9 mo | 97.7% response in azithromycin group vs 95.0% in BPG group |

| Hook et al,24 2002 | Randomized pilot | 60 patients with early syphilis | 4% HIV infected | 14 treated with BPG, 2.4 million U IM as 1 dose; 17 with single-dose azithromycin and 29 with double-dose azithromycin, 2.0 g orally as 1 dose | Serologic response: clinical resolution and negative or 4-fold decrease in RPR Serofast status: clinical resolution with no change or ≤2-fold change in RPR Failure: new lesions or ≥4-fold increase in RPR |

Response rates: 12/14 (86%) of BPG, 16/17 (94%) of single-dose azithromycin, and 24/29 (83%) of double-dose azithromycin Failure in 1 with BPG and 1 with double-dose azithromycin |

Abbreviations: APPG, aqueous procaine penicillin G; BPG, benzathine penicillin G; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IM, intramuscularly; NA, not available (study conducted prior to HIV era or did not address HIV status); PAM, penicillin aluminum monostearate; RPR, rapid plasma reagin; TRUST, toluidine red unheated serum test; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory.

Monitoring Syphilis Treatment Response

Both diagnosis and assessment of treatment response rely on serologic tests (Box). Treponemal tests detect antibodies to specific antigenic components of T pallidum, while nontreponemal tests detect antibodies to a nonspecific cardiolipin-cholesterol-lecithin reagin antigen produced by the host in response to syphilis infection.39 Nontreponemal serologic tests such as the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test or the rapid plasma reagin test are used to monitor treatment response because they usually correlate with disease activity. Different nontreponemal tests do not provide interchangeable measurements; for example, rapid plasma reagin titers are often higher than VDRL titers. In general, a 4-fold decline in nontreponemal titer (such as a decrease from 1:32 to 1:8) is needed to signify treatment response. There are limitations to relying on changes in serologic titers to monitor response to treatment. For example, a recent report demonstrated that 20% of patients with syphilis experienced at least a 1-dilution (2-fold) increase in nontreponemal titer within 14 days of treatment, suggesting that the actual baseline titer used to assess response is often underestimated.40 Coinfection with HIV may also contribute to therapeutic uncertainty because HIV-infected patients may experience slower serologic response rates after apparently successful treatment.41-44

Box. Serologic Tests for Syphilis.

Treponemal tests: detect antibodies to specific antigenic components of Treponema pallidum

Treponema pallidum particle agglutination

Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed

Enzyme immunoassay

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Chemiluminescence assay

Nontreponemal tests: detect antibodies to nonspecific antigens produced by the host in response to treponemal infection

Rapid plasma reagin

Venereal Disease Research Laboratory

Toluidine red unheated serum test

Unheated serum reagin

The Serofast State

The serofast state refers to a situation in which nontreponemal antibodies decline (often adequately) after treatment but fail to completely revert to nonreactive.45 Persons with low pretreatment titers are also sometimes said to be serofast when there is minimal (≤2-fold) or no change following treatment. The serofast state may represent a number of different phenomena, including persistent low-level T pallidum infection, variability of host antibody response to infection, or tissue injury due to nonsyphilitic inflammatory conditions.46 A significant proportion of patients remain serofast after treatment (15%-41%), although rates depend on syphilis stage, pretreatment titer, and the time point at which response is assessed, all of which vary from study to study.13,47-50 Available data suggest that re-treatment has a modest effect on the serofast state, with only 27% of such patients achieving serologic cure in 1 study.46

Efficacy of Parenteral Penicillin for Early Syphilis

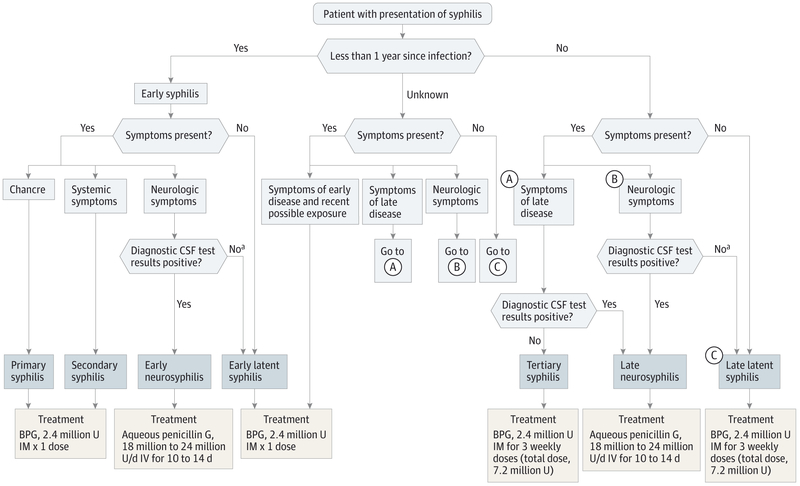

Treatment of syphilis is based on stage of infection and on whether there is evidence of central nervous system involvement (Figure). Treponema pallidum remains extremely susceptible to penicillin, an antimicrobial agent targeting bacterial cell wall synthesis. During more than 60 years of use, there has never been a documented case of penicillin resistance.51 The organism’s slow dividing time (30-33 hours) requires the prolonged presence of killing (treponemicidal) concentrations of antimicrobial agents. Depot preparations achieve this goal and have thus become the mainstay of treatment based on decades of experience.52,53 Nonetheless, only limited clinical trial evidence of efficacy exists, and interpretation of data from available studies is complicated by heterogeneous definitions of syphilis stage, differences in treatment regimens, and nonstandard treatment outcome measurements (Table 3).10,30-35 Despite the limitations in published studies, the predominance of evidence, including more recent high-quality studies, supports the use of parenteral penicillin, and it remains the treatment of choice. The quality of evidence for penicillin and alternate therapies, graded according to the American Heart Association classification system, is shown in Table 2.

Figure. Suggested Algorithm for Treatment of Syphilis.

BPG indicates benzathine penicillin G; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous.

a Some clinicians would treat patients with syphilis who have neurologic symptoms for neurosyphilis despite negative diagnostic CSF test results.

For early syphilis, studies from the 1950s onward have focused on benzathine penicillin G (BPG) and demonstrate favorable cure rates and infrequent need for re-treatment. Historical estimates for the rate of treatment failure with a single dose of 2.4 million U of BPG are around 5%.54 In 1956, Smith et al34 reported BPG efficacy in early syphilis, finding that response rates with a single BPG injection were not different from multiple injections of procaine penicillin with aluminum monostearate (a long-acting formulation no longer widely available). At 2 years, 94.5% to 100% of all patients had a seronegative status, depending on stage. Similarly, Schroeter et al36 showed no difference in outcomes with single-dose BPG compared with multiple-dose penicillin regimens (11.4% vs 10.7%-10.9% 2-year cumulative re-treatment rates). Some reports claim superiority with multiple doses rather than a single injection of BPG,31,32 but these studies have been criticized for lack of a control group or exclusion of reinfected patients based on serological response pattern (thus overestimating success, as some of those excluded patients may actually have had treatment failure).55

A 1997 study by Rolfs et al10 that included 541 patients remains the only large RCT for syphilis therapy from the 20th century. The study compared a single standard dose of 2.4 million U of intramuscular BPG with an “enhanced therapy” regimen (the addition of high-dose oral amoxicillin/probenecid to BPG) and found no difference in outcome between the 2 groups. In that study, serologic failure was rigidly defined (requiring a 4-fold decline in nontreponemal titer by 3 months), contributing to the relatively high failure rate in each group (18% and 17%, respectively, at 6 months).10 Only 1 patient, who was HIV infected, experienced clinical treatment failure (new rash) during follow-up. However, definitive conclusions are limited because of high loss to follow-up in the trial (52% at 1 year).

More recently, trials comparing penicillin with nonpenicillin regimens confirm the efficacy of a single intramuscular injection of 2.4 million U of BPG for early syphilis. In a 2005 RCT by Riedner et al11 in which 328 patients were enrolled, 95% of those receiving BPG achieved serologic cure, a majority of whom had high-titer, presumptive early latent syphilis. Hook et al12 published an RCT in 2010 that included 517 patients and compared oral azithromycin with BPG; 79% of BPG recipients achieved serologic cure by 6 months. Other recent retrospective studies have also demonstrated high success rates with single-dose BPG for early syphilis.14,15

Penicillin in Late and Late Latent Syphilis

Minimal high-quality evidence exists to guide the therapy for late syphilis. It has been postulated that longer-duration penicillin therapy may be required for late syphilis because treponemes appear to divide more slowly during later stages of infection, but the validity of this concept has not been rigorously assessed.7 Only limited data exist regarding late latent syphilis therapy. In 2005, Kiddugavu et al25 published a secondary analysis of an RCT studying 818 patients (86%) who had presumptive late latent syphilis. Benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million U intramuscularly, was given as a single dose or along with oral azithromycin. Response rates were modest (cure rates of 56%-63%). Smith et al published a small randomized pilot study in 2004 in which 7 of 10 HIV-infected patients treated with procaine penicillin had an appropriate decline in titers, although 2 subsequently relapsed and 3 remained in a serofast state.37 Most participants in this study were not taking effective antiretroviral therapy (ART), and the majority were presumed to have late latent syphilis. Another study of HIV-infected patients not taking suppressive ART who had late latent syphilis (some with central nervous system involvement) showed that 3 weekly injections of BPG resulted in an appropriate serologic response in only 62%.38

Efficacy of Therapies Other Than Benzathine Penicillin G for Syphilis

The evidence for nonpenicillin treatment of syphilis consists mostly of small, uncontrolled, retrospective studies, although a few larger, randomized trials exist (Table 4).10-17,20-27,31,34,36-38 Erythromycin is no longer recommended based on tolerability and resistance concerns,56 but doxycycline, ceftriaxone, and azithromycin are still considered potential alternatives to penicillin.

Doxycycline

Several studies, mostly small and retrospective, indicate that doxycycline/tetracycline is effective treatment for early syphilis, with serologic response rates of 83% to 100%.13-19 Most studies used oral doxycycline, 100 mg twice daily for 14 days, a regimen that has been shown to have 73% to 89% response rates in HIV-infected patients.16,17 Doxycycline is advantageous in that it has simultaneous activity against other sexually transmitted infections. However, the requirement for multiple days of treatment when using doxycycline introduces adherence concerns compared with the preferred single observed dosing with intramuscular BPG. As a result, doxycycline is considered an alternative to BPG in the treatment of syphilis.

Ceftriaxone

Several small studies of intramuscular ceftriaxone for early syphilis have shown efficacy comparable with penicillin G.16,20-23 Most of these trials used parenteral once-daily doses of 1 to 2 g for 10 to 15 days with serologic response rates of 65% to 100%. The lowest response rates were seen in HIV-infected patients, particularly among patients with incomplete HIV suppression. Treatment failure was most often noted in HIV-infected patients with latent syphilis.37,38 Ceftriaxone treatment of syphilis requires multiple daily parenteral doses and is both more cumbersome and more expensive than single-dose BPG but has the advantage of treating other coexisting sexually transmitted infections and may be useful in patients with penicillin allergy.57 Use of cephalosporins in patients with penicillin allergy is discussed below.

Azithromycin

Randomized clinical trials have shown that oral azithromycin (as a single 1- to 2-g dose) is effective in the treatment of early syphilis, with much of the data derived from studies done in Africa.11,12,24 The emergence of azithromycin resistance mutations in T pallidum with resultant treatment failure has limited its usefulness in many regions of the United States.56,58-62 In a study of 141 T pallidum samples collected from 11 US clinics between 2007 and 2009, the 23s rRNA A2058G point mutation (associated with macrolide resistance/treatment failure) was found in 53% of specimens.61 Azithromycin has also been associated with a 5-fold greater risk of gastrointestinal adverse effects compared with BPG.27 It is no longer recommended as syphilis treatment unless special circumstances require its use.

The Jarisch-Herxheimer Reaction

The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is a significant adverse event that can occur with any antibiotic treatment for syphilis but is most common after penicillin. This reaction manifests with systemic symptoms including fever, rash, malaise, headache, and myalgias, typically occurring within 24 hours of treatment of early syphilis. It is seen in 10% to 35% of patients and is usually self-limited.63 The reaction is thought to result from release of lipoproteins, cytokines, and immune complexes from killed organisms.63,64

Penicillin Allergy and Penicillin Desensitization

Given the availability of nonpenicillin options for the treatment of syphilis, the need for penicillin desensitization approaches seems limited, and it is not well studied.65

However, in some settings, penicillin is clearly the treatment of choice and desensitization is probably the preferred option in the following situations: (1) neurosyphilis in persons with a history of severe immediate hypersensitivity reaction to penicillin; (2) tertiary syphilis in all penicillin-allergic patients; (3) any stage of syphilis in penicillin-allergic pregnant women; and (4) congenital syphilis in penicillin-allergic infants.7

Special Circumstances: Neurosyphilis, HIV-Infected Persons, and Pregnant Women

Neurosyphilis

Successful neurosyphilis treatment requires the presence of adequate, prolonged cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of a treponemicidal antimicrobial (Table 5). Benzathine penicillin G should not be used because it does not reliably achieve sufficient concentrations in CSF. Intravenous administration of aqueous crystalline penicillin G achieves adequate CSF levels and is the treatment of choice for neurosyphilis.69 Procaine penicillin injections also achieve treponemicidal levels in CSF, and there is evidence of clinical improvement in some studies, but the regimen is often difficult to complete because of the need for multiple intramuscular injections that can be painful and the requirement for adherence to oral probenecid 4 times daily.70,71

Table 5.

Parenteral Penicillin Regimens

| Drug | Route | Cerebrospinal Fluid Concentration |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzathine penicillin G66 | Intramuscular | Low | Very low solubility leading to slow release from injection site; blood concentrations detectable up to 4 wk after injection |

| Aqueous procaine penicillin G67 | Intramuscular | High | Slowly dissolving; blood levels plateau at about 4 h then decrease slowly over the next 15 to 20 h |

| Aqueous penicillin G (benzylpenicillin)68 | Intramuscular or intravenous | High | Half-life of 42 min |

Treatment of neurosyphilis in patients with significant penicillin allergy is challenging, and penicillin desensitization is probably the best option. Ceftriaxone (2 g/d intramuscularly or intravenously for 10-14 days) is an alternative, but evidence of its efficacy is limited.72-74 Risk of cross-reactivity between penicillin and ceftriaxone is negligible, but skin testing for β-lactam allergy and desensitization can be done if needed.7,57

HIV Coinfection

Syphilis and HIV infection are strongly linked with one another. Most of the recent increase in syphilis cases in the United States has occurred in MSM, and rates of HIV coinfection as high as 50% to 70% have been reported among MSM diagnosed as having primary and secondary syphilis.75

There are few studies comparing syphilis treatment of HIV-coinfected patients with HIV-uninfected controls.76 Patients with HIV infection may be at increased risk of serologic failure following treatment, although this is controversial.41,43 Some studies comparing serologic response rates between HIV-infected and uninfected persons show no difference in treatment success rates.10,77 Other studies attribute the perceived increased risk of treatment failure to a slower decline in titer in HIV-infected individuals.42 Lower CD4 cell counts are associated with delayed treatment response and increased risk of serologic failure among HIV-infected patients.41,78 Data from the pre-ART era suggest a shorter latency period before progression to neurosyphilis and an increased risk of progression to neurosyphilis despite adequate treatment for early syphilis.79-81 Based on these observations, some authorities recommend a longer duration of penicillin for early syphilis in HIV-infected persons (7.2 million U of BPG given as 3 weekly 2.4 million-U doses).82 A recent retrospective study of patients with primary and secondary syphilis found a nonsignificant increase in serologic response rates in HIV-infected patients who received 3 weekly doses of penicillin compared with those treated with a single dose of BPG (serologic cure in 88% with a single dose vs 97% with 3 doses; P = .18); however, another study from 2013 demonstrated no difference in BPG treatment outcome between single-dose treatment and multiple-dose (3 weekly injections) treatment in HIV-infected patients with early syphilis.28,78 Effective ART appears to reduce the likelihood of serologic failure as well as progression to neurosyphilis.83,84

While HIV infection appears to affect syphilis outcomes, syphilis also appears to affect the course of HIV infection. Increased HIV replication and reduced CD4 cell counts have been reported among HIV-infected patients with syphilis, highlighting the importance of appropriate treatment for both infections.85-87

HIV Infection and Neurosyphilis

Reports of increased risk of neurosyphilis emerged soon after recognition of the HIV epidemic.80,81,88,89 As with all patients, successful treatment of neurosyphilis in HIV-infected persons requires sustained treponemicidal CSF penicillin concentrations. Some studies suggest that as many as 60% of HIV-infected patients may have failure of currently recommended neurosyphilis therapy with intravenous penicillin G.81,90,91 Although penicillin is the preferred treatment for neurosyphilis, ceftriaxone, 1 to 2 g/d intravenously for 10 days, is thought to be an effective alternative in HIV-infected patients with neurosyphilis based on data from small observational studies.37,38,92 One prospective study demonstrated that HIV-infected patients with low CD4 cell counts (<200/mL) were less likely to clear CSF-VDRL titers after treatment, illustrating the need for immune recovery facilitated by effective ART as part of optimal management.93

Pregnant Women

Most cases of congenital syphilis result from transmission of T pallidum to the fetus during early syphilis, while most adverse pregnancy outcomes occur in women treated for syphilis in the third trimester, demonstrating the importance of timely syphilis screening and treatment in pregnancy.94,95 Observational studies of syphilis in pregnant women suggest that standard treatment based on stage of syphilis at diagnosis is sufficient.96-99 A Cochrane review published in 2010 found no syphilis treatment studies that met predetermined criteria for treatment group comparisons nor any that used randomly allocated groups of pregnant women.100,101

Risks associated with the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in pregnant women may be significant, including induction of early labor or fetal distress. Pregnant women should be warned about this potential outcome prior to treatment, but therapy should not be delayed or withheld. Alternatives to penicillin are not recommended because of potential fetal toxicity (doxycycline) or failure of treatment to cross the placenta (azithromycin). There is limited evidence suggesting that parenteral ceftriaxone is effective, but no controlled trials have been performed.7,101

Discussion

Based on this review of the available literature, the preferred regimen for early syphilis, including primary, secondary, and early latent infection, is 2.4 million U of BPG in a single intramuscular injection. Late and late latent infection should be treated with 3 weekly injections of 2.4 million U of BPG, totaling 7.2 million U. Treatment response should be assessed by repeat measurements of nontreponemal serologic titers at 6 and 12 months following treatment of primary and secondary syphilis and at 6, 12, and 24 months for late and latent syphilis. Patients who are in a serofast state do not appear to benefit substantially from re-treatment. Doxycycline and ceftriaxone are also effective treatments for early syphilis when penicillin cannot be used, and reasonable evidence exists to support the use of either as alternatives to penicillin. Because of the potential for resistance, azithromycin should not be used to treat patients in the United States except when other agents are not available. Careful follow-up is essential.

Treatment of neurosyphilis should be aqueous crystalline penicillin G, 18 million to 24 million U/d via continuous infusion or divided into 6 daily doses for 10 to 14 days. Unfortunately, the data supporting this treatment regimen are modest and largely based on achievement of adequate treponemicidal CSF concentrations rather than demonstrated clinical efficacy. Individuals with HIV infection should be treated similarly to uninfected patients based on the available evidence and because the preponderance of data on syphilis treatment in HIV-infected persons were compiled in the era prior to the widespread availability of effective ART (which likely improves syphilis treatment responses). Although evidence is limited in pregnant women, the preferred treatment is penicillin, and pregnant women known to have penicillin allergy should be desensitized.7

Our recommendations align with those of the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC). Although a few large RCTs support the current CDC recommendations, they are primarily based on results from early, uncontrolled studies and on decades of clinical experience. The best data exist for early syphilis because it encompasses the majority of diagnosed cases. In contrast, evidence in support of treatment recommendations for late and late latent syphilis is quite limited, as is also true for neurosyphilis, for HIV-infected persons, and for pregnant women. The CDC’s guidelines for treating syphilis in the setting of HIV infection are largely based on data from a 1997 RCT (done before the era of effective ART) that showed that HIV-infected patients respond comparably with HIV-uninfected persons.10 However, only 69 HIV-infected persons in this study completed 6 months of follow-up and the only clinical failure occurred in an HIV-infected patient. Given the increasing rate of syphilis in the MSM population, there is a need for additional high-quality studies.

Conclusions

After declining to historic lows at the turn of the 21st century, the incidence of syphilis has progressively increased in the United States, particularly in MSM. Penicillin remains the treatment of choice for all stages of syphilis, with different regimens suggested based on stage. Rigorous data from clinical trials to support the recommended regimens are generally lacking, and most existing data are limited by the lack of a gold standard to assess cure. Furthermore, the absence of homogeneous diagnostic definitions and outcome measurements among the available studies limits comparisons.102 Larger, high-quality studies would be beneficial, especially in the disproportionately affected HIV-infected population, but seem unlikely to be carried out. Current recommendations are largely driven by clinical experience and expert opinion because available data are limited and sometimes conflicting. The accumulated clinical experience suggests that the current guidelines are largely successful. With the preponderance of available clinical data supporting penicillin as the preferred treatment option, the use of benzathine penicillin G offers a convenient, directly observed regimen that combines ease of administration with demonstrated antitreponemal activity. Penicillin will likely remain the cornerstone of syphilis treatment for years to come.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

- ART

antiretroviral therapy

- BPG

benzathine penicillin G

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- MSM

men who have sex with men

- RCT

randomized clinical trial

- VDRL

Venereal Disease Research Laboratory

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Dr Hicks reports contracted research agreements with Argos, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, and ViiV and consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, and ViiV. No other disclosures were reported.

Contributor Information

Meredith E. Clement, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina.

N. Lance Okeke, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina.

Charles B. Hicks, Divisions of General Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases, University of California, San Diego..

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis fact sheet. http://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/STDFact-Syphilis-detailed.htm. Accessed January 19, 2014.

- 2.Golden MR, Marra CM, Holmes KK. Update on syphilis. JAMA. 2003;290(11):1510–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomez GB, Kamb ML, Newman LM, et al. Untreated maternal syphilis and adverse outcomes of pregnancy. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(3): 217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ingraham NR Jr. The value of penicillin alone in the prevention and treatment of congenital syphilis. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1950;31 (suppl 24):60–87 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tobian AA, Quinn TC. Herpes simplex virus type 2 and syphilis infections with HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2009;4(4):294–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patton ME, Su JR, Nelson R, Weinstock H; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Primary and secondary syphilis—United States, 2005-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63 (18):402–406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen SE, Klausner JD, Engelman J, Philip S. Syphilis in the modern era. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2013;27(4):705–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STD Surveillance Case Definitions Effective January 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats/CaseDefinitions-2014.pdf. Accessed August 17, 2014.

- 10.Rolfs RT, Joesoef MR, Hendershot EF, et al. ; Syphilis and HIV Study Group. A randomized trial of enhanced therapy for early syphilis in patients with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(5):307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riedner G, Rusizoka M, Todd J, et al. Single-dose azithromycin vs penicillin G benzathine for the treatment of early syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353 (12):1236–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hook EW III, Behets F, Van Damme K, et al. A phase III equivalence trial of azithromycin vs benzathine penicillin for treatment of early syphilis. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(11):1729–1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Zheng H-Y. Early syphilis: serological treatment response to doxycycline/tetracycline vs benzathine penicillin. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8(2): 228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghanem KG, Erbelding EJ, Cheng WW, Rompalo AM. Doxycycline compared with benzathine penicillin for the treatment of early syphilis. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(6):e45–e49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong T, Singh AE, De P. Primary syphilis: serological treatment response to doxycycline/tetracycline vs benzathine penicillin. Am J Med. 2008;121(10):903–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Psomas KC, Brun M, Causse A, Atoui N, Reynes J, LeMoing V. Efficacy of ceftriaxone and doxycycline in the treatment of early syphilis. Med Mal Infect. 2012;42(1):15–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long CM, Klausner JD, Leon S, et al. ; NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group. Syphilis treatment and HIV infection in a population-based study of persons at high risk for sexually transmitted disease/HIV infection in Lima, Peru. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(3):151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Onoda Y. Therapeutic effect of oral doxycycline on syphilis [in Japanese]. Jpn J Antibiot. 1980;33 (1):18–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harshan V, Jayakumar W. Doxycycline in early syphilis: a long term follow up. Indian J Dermatol. 1982;27(4):119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spornraft-Ragaller P,Abraham S, Lueck C, Meurer M. Response of HIV-infected patients with syphilis to therapy with penicillin or intravenous ceftriaxone. Eur J Med Res. 2011;16(2):47–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schöfer H, Vogt HJ, Milbradt R. Ceftriaxone for the treatment of primary and secondary syphilis. Chemotherapy. 1989;35(2):140–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hook EW III, Roddy RE, Handsfield HH. Ceftriaxone therapy for incubating and early syphilis. J Infect Dis. 1988;158(4):881–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moorthy TT, Lee CT, Lim KB, Tan T. Ceftriaxone for treatment of primary syphilis in men. Sex Transm Dis. 1987;14(2):116–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hook EW III, Martin DH, Stephens J, et al. A randomized, comparative pilot study of azithromycin vs benzathine penicillin G for treatment of early syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 2002; 29(8):486–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiddugavu MG, Kiwanuka N, Wawer MJ, et al. ; Rakai Study Group. Effectiveness of syphilis treatment using azithromycin and/or benzathine penicillin in Rakai, Uganda. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32 (1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bai ZG, Wang B, Yang K, et al. Azithromycin vs penicillin G benzathine for early syphilis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:CD007270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bai Z-G, Yang K-H, Liu Y-L, et al. Azithromycin vs benzathine penicillin G for early syphilis. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19(4):217–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tittes J, Aichelburg MC, Antoniewicz L, Geusau A. Enhanced therapy for primary and secondary syphilis. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24(9):703–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibbons RJ, Smith S, Antman E; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association clinical practice guidelines, I. Circulation. 2003;107(23):2979–2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Talwar S, Tutakne MA, Tiwari VD. VDRL titres in early syphilis before and after treatment. Genitourin Med. 1992;68(2):120–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fiumara NJ. Treatment of primary and secondary syphilis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14 (3):487–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Durst RD Jr, Sibulkin D, Trunnell TN,Allyn B. Dose-related seroreversal in syphilis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108(5):663–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jefferiss FJG, Willcox RR. Treatment of early syphilis with penicillin alone. Br J Vener Dis. 1963;39 (3):143–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith CA, Kamp M, Olansky S, Price EV. Benzathine penicillin G in the treatment of syphilis. Bull World Health Organ. 1956;15(6):1087–1096. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sternberg TH, Leifer W. Treatment of early syphilis with penicillin. JAMA. 1947;133(1):1–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.1947.02880010003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schroeter AL, Lucas JB, Price EV, Falcone VH. Treatment for early syphilis and reactivity of serologic tests. JAMA. 1972;221(5):471–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith NH, Musher DM, Huang DB, et al. Response of HIV-infected patients with asymptomatic syphilis to intensive intramuscular therapy with ceftriaxone or procaine penicillin. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15(5):328–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dowell ME, Ross PG, Musher DM, et al. Response of latent syphilis or neurosyphilis to ceftriaxone therapy in persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Med. 1992;93(5): 481–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Association of Public Health Laboratories. Laboratory Diagnostic Testing for Treponema pallidum: Expert Consultation Meeting Summary Report. January 2009. http://www.aphl.org/aphlprograms/infectious/std/Documents/ID_2009Jan_Laboratory-Guidelines-Treponema-pallidum-Meeting-Report.pdf. Accessed October 19, 2013.

- 40.Holman KM, Wolff M, Seña AC, et al. Rapid plasma reagin titer variation in the 2 weeks after syphilis therapy. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(8):645–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghanem KG, Erbelding EJ, Wiener ZS, Rompalo AM. Serological response to syphilis treatment in HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients attending sexually transmitted diseases clinics. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83(2):97–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manavi K, McMillan A. The outcome of treatment of early latent syphilis and syphilis with undetermined duration in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected patients. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18 (12):814–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.González-López JJ, Guerrero MLF, Luján R, et al. Factors determining serologic response to treatment in patients with syphilis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(10):1505–1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Knaute DF, Graf N, Lautenschlager S, et al. Serological response to treatment of syphilis according to disease stage and HIV status. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(12):1615–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghanem KG, Workowski KA. Management of adult syphilis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(suppl 3):S110–S128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seña AC, Wolff M, Behets F, et al. Response to therapy following retreatment of serofast early syphilis patients with benzathine penicillin. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(3):420–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agmon-Levin N, Elbirt D, Asher I, et al. Syphilis and HIV co-infection in an Israeli HIV clinic. Int J STD AIDS. 2010;21(4):249–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tong M-L, Lin L-R, Liu G-L, et al. Factors associated with serological cure and the serofast state of HIV-negative patients with primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary syphilis. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e70102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dionne-Odom J, Karita E, Kilembe W, et al. Syphilis treatment response among HIV-discordant couples in Zambia and Rwanda. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(12):1829–1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seña AC, Wolff M, Martin DH, et al. Predictors of serological cure and serofast state after treatment in HIV-negative persons with early syphilis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(11):1092–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lewis DA, Lukehart SA. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Treponema pallidum. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(suppl 2):ii39–ii43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nell EE. Comparative sensitivity of treponemes of syphilis, yaws, and bejel to penicillin in vitro, with observations on factors affecting its treponemicidal action. Am J Syph Gonorrhea Vener Dis. 1954;38(2): 92–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Norris SJ, Edmondson DG. In vitro culture system to determine MICs and MBCs of antimicrobial agents against Treponema pallidum subsp pallidum (Nichols strain). Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32(1):68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Idsoe O, Guthe T, Willcox RR. Penicillin in the treatment of syphilis. Bull World Health Organ. 1972;47(suppl):1–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rolfs RT. Treatment of syphilis, 1993. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20(suppl 1):S23–S38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lukehart SA, Godornes C, Molini BJ, et al. Macrolide resistance in Treponema pallidum in the United States and Ireland. N Engl J Med. 2004; 351(2):154–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pichichero ME, Casey JR. Safe use of selected cephalosporins in penicillin-allergic patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136(3):340–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klausner JD, Kohn RP, Kent CK. Azithromycin vs penicillin for early syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354(2):203–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marra CM, Colina AP, Godornes C, et al. Antibiotic selection may contribute to increases in macrolide-resistant Treponema pallidum. J Infect Dis. 2006;194(12):1771–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Damme K, Behets F, Ravelomanana N, et al. Evaluation of azithromycin resistance in Treponema pallidum specimens from Madagascar. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(12):775–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.A2058G Prevalence Workgroup. Prevalence of the 23S rRNA A2058G point mutation and molecular subtypes in Treponema pallidum in the United States, 2007 to 2009. Sex Transm Dis. 2012; 39(10):794–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Azithromycin treatment failures in syphilis infections—San Francisco, California, 2002-2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(9):197–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang C-J, Lee N-Y, Lin Y-H, et al. Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction after penicillin therapy among patients with syphilis in the era of the HIV infection epidemic. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(8):976–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pound MW, May DB. Proposed mechanisms and preventative options of Jarisch-Herxheimer reactions. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2005;30(3):291–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cernadas JR, Brockow K, Romano A, et al. ; European Network of Drug Allergy and the EAACI Interest Group on Drug Hypersensitivity. General considerations on rapid desensitization for drug hypersensitivity—a consensus statement. Allergy. 2010;65(11):1357–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.National Library of Medicine. Bicillin L-A (penicillin G benzathine) injection. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=012d46f1-d0a0-4676-a879-cd320297ab16. Accessed May 24, 2014.

- 67.National Library of Medicine. Penicillin G procaine injection. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=07fe2b47-34ac-4a20-be67-3c788c77b207#nlm34090-1. Accessed May 24, 2014.

- 68.National Library of Medicine. Penicillin G sodium injection. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=23b6d4a3-b273-4e10-9da9-1376933fdbdf. Accessed May 24, 2014.

- 69.Mohr JA, Griffiths W, Jackson R, et al. Neurosyphilis and penicillin levels in cerebrospinal fluid. JAMA. 1976;236(19):2208–2209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dunlop EM, Al-Egaily SS, Houang ET. Production of treponemicidal concentration of penicillin in cerebrospinal fluid. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 1981;283(6292):646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hellerstrom S, Skog E. Outcome of penicillin therapy of syphilis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1962;42: 179–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gentile JH, Viviani C, Sparo MD, Arduino RC. Syphilitic meningomyelitis treated with ceftriaxone. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26(2):528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hook EW III, Baker-Zander SA, Moskovitz BL, et al. Ceftriaxone therapy for asymptomatic neurosyphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1986;13(3)(suppl): 185–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shann S, Wilson J. Treatment of neurosyphilis with ceftriaxone. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79(5): 415–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Su J, Weinstock H. Epidemiology of co-infection with HIV and syphilis in 34 states, United States—2009. In: Proceedings of the 2011 National HIV Prevention Conference; August 14-17, 2011; Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Blank LJ, Rompalo AM, Erbelding EJ, et al. Treatment of syphilis in HIV-infected subjects. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(1):9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Goeman J, Kivuvu M, Nzila N, et al. Similar serological response to conventional therapy for syphilis among HIV-positive and HIV-negative women. Genitourin Med. 1995;71(5):275–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jinno S, Anker B, Kaur P, et al. Predictors of serological failure after treatment in HIV-infected patients with early syphilis in the emerging era of universal antiretroviral therapy use. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pialoux G, Vimont S, Moulignier A, et al. Effect of HIV infection on the course of syphilis. AIDS Rev. 2008;10(2):85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Musher DM, Hamill RJ, Baughn RE. Effect of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection on the course of syphilis and on the response to treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(11):872–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gordon SM, Eaton ME, George R, et al. The response of symptomatic neurosyphilis to high-dose intravenous penicillin G in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(22):1469–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Musher DM. Syphilis, neurosyphilis, penicillin, and AIDS. J Infect Dis. 1991;163(6):1201–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ghanem KG, Moore RD, Rompalo AM, et al. Antiretroviral therapy is associated with reduced serologic failure rates for syphilis among HIV-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(2): 258–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ghanem KG, Moore RD, Rompalo AM, et al. Neurosyphilis in a clinical cohort of HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS. 2008;22(10):1145–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Buchacz K, Patel P, Taylor M, et al. Syphilis increases HIV viral load and decreases CD4 cell counts in HIV-infected patients with new syphilis infections. AIDS. 2004;18(15):2075–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Palacios R, Jiménez-Oñate F, Aguilar M, et al. Impact of syphilis infection on HIV viral load and CD4 cell counts in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44(3):356–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kofoed K, Gerstoft J, Mathiesen LR, Benfield T. Syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 coinfection. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(3):143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Flood JM, Weinstock HS, Guroy ME, et al. Neurosyphilis during the AIDS epidemic, San Francisco, 1985-1992. J Infect Dis. 1998;177(4):931–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schöfer H, Imhof M,Thoma-Greber E,et al. ; German AIDS Study Group. Active syphilis in HIV infection. Genitourin Med. 1996;72(3):176–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Marra CM, Longstreth WT Jr, Maxwell CL, Lukehart SA. Resolution of serum and cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities after treatment of neurosyphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1996;23(3):184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Malone JL, Wallace MR, Hendrick BB, et al. Syphilis and neurosyphilis in a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 seropositive population. Am J Med. 1995;99(1):55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Marra CM, Boutin P, McArthur JC, et al. A pilot study evaluating ceftriaxone and penicillin G as treatment agents for neurosyphilis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(3):540–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Marra CM, Maxwell CL, Tantalo L, et al. Normalization of cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities after neurosyphilis therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38 (7):1001–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hawkes SJ, Gomez GB, Broutet N. Early antenatal care: does it make a difference to outcomes of pregnancy associated with syphilis? PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Qin J, Yang T, Xiao S, et al. Reported estimates of adverse pregnancy outcomes among women with and without syphilis. PLoS One. 2014;9(7): e102203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Kamb M, et al. Lives Saved Tool supplement detection and treatment of syphilis in pregnancy to reduce syphilis related stillbirths and neonatal mortality. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(suppl 3):S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Alexander JM, Sheffield JS, Sanchez PJ, et al. Efficacy of treatment for syphilis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(1):5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Watson-Jones D, Gumodoka B, Weiss H, et al. Syphilis in pregnancy in Tanzania, II. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(7):948–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Berman SM. Maternal syphilis. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(6):433–438. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Walker GJ. Antibiotics for syphilis diagnosed during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(3):CD001143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhou P, Gu Z, Xu J, et al. A study evaluating ceftriaxone as a treatment agent for primary and secondary syphilis in pregnancy. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(8):495–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Parkes R, Renton A, Meheus A, Laukamm-Josten U. Review of current evidence and comparison of guidelines for effective syphilis treatment in Europe. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15(2):73–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.