Abstract

There has been much interest recently in the relationship between economic conditions and mortality, with some studies showing that mortality is pro-cyclical, while others find the opposite. Some suggest that the aggregation level of analysis (e.g. individual vs. regional) matters. We use both individual and aggregated data on a sample of 20–64 year-old Swedish men from 1993 to 2007. Our results show that the association between the business cycle and mortality does not depend on the level of analysis: the sign and magnitude of the parameter estimates are similar at the individual level and the aggregate (county) level; both showing pro-cyclical mortality.

Keywords: Death, Recession, Health, Unemployment, Income, Aggregation

JEL classification: E3, I1, I12

1. Introduction

There is a renewed interest in the relationship between mortality and economic conditions. Since the work by Ruhm (2000), showing that mortality increases in good economic times, many studies have attempted to replicate the findings using different datasets, different methods, and different outcomes of health and health behaviors. Their results are mixed, with some findings supporting the idea that health deteriorates, or mortality increases, with improvements in economic conditions (see e.g. Gerdtham and Ruhm, 2006; Neumayer, 2004; Tapia Granados, 2005, 2008), while others find the opposite (see e.g. Gerdtham and Johannesson, 2005; Svensson, 2007; Economou et al., 2008).

One of the differences between these studies is the level of analysis: studies using aggregate (macro-level) data tend to find that mortality is pro-cyclical (e.g. Ruhm, 2000; Gerdtham and Ruhm, 2006; Neumayer, 2004), whereas studies that use individual-level (micro) data tend to find the opposite (e.g. Gerdtham and Johannesson, 2005). Using both micro- and macro-level data, Edwards (2008) finds evidence of pro-cyclicality on the aggregated data, while the individual-level analyses provide more mixed results, finding different relationships for different subgroups. This would suggest that the level of analysis plays a crucial role in estimating the relationship between mortality and the business cycle.1

Many factors may be able to explain this. A useful starting point is the observation that if we use the same data for the micro level as for the macro level, and if in each case we only use covariates that are quantified at the macro level, notably the cyclical indicator, then the estimated regression coefficients are identical for both levels of analysis. Thus, only the inclusion of covariates in the micro-level analysis that vary at the micro level can lead to differences between the micro and macro point-estimates. With such covariates, a range of issues may create a difference between the micro-estimate and the estimate from a macro-level analysis that uses averages of the micro-level covariates as explanatory variables. For example, these covariates may contain measurement errors at the individual level or their values may be endogenous at the individual level. Misspecifications of the functional form of the model equations may also cause estimates to differ by level, especially if the business-cycle effect is heterogeneous across individuals.2

Of course, if both estimates of the coefficient of interest are identical then this does not rule out that both are equally biased. This can happen in the absence of additional relevant covariates, for example if for some reason the years with recessions in the observation window overrepresent birth cohorts with adverse unobserved systematic health features. This provides a justification for teasing out any systematic trend from the time series of the macroeconomic indicator. (As a by-product of our paper, we therefore provide sensitivity analyses based on this idea, see Section 5.3.).

Our paper explores the role of aggregation in more detail on a large dataset. Using a random sample from the entire Swedish male population aged 20–64 between 1993 and 2007, we examine the relationship between transitory changes in economic conditions and individual as well as regional (county-level) mortality. We focus on the question of how accurately models using aggregate data infer effects of the business cycle on mortality at the individual level by comparing the analyses on the same underlying data, estimated at both levels. Our results at the individual level show evidence of pro-cyclicality, with temporary downturns in economic conditions decreasing mortality. These findings are robust to the inclusion of a set of covariates. We then collapse the data to the county-level and run the same analyses. The estimates on the aggregated data both share sign and yield similar magnitudes of the parameter estimates, suggesting that aggregate data indeed adequately infer the individual-level association between business cycles and mortality. Our analyses hence show that estimates of the relationship between mortality and the business cycle are not sensitive to the level at which the dependent variable is measured. This finding suggests that it is not the different levels of analyses that are likely to be driving some of the conflicting results found in the existing literature.

Our individual-level analyses show evidence of pro-cyclical mortality, driven by 20–44 year old men, with no significant effects among those aged 45–64. The subgroup analyses reveal a social gradient in the response to macro-economic fluctuations in that the business cycle effect on mortality is present only among those in the lowest income quintile and among those with low education.

The structure of our paper is as follows: Section 2 gives the background to the study and discusses some of the existing literature. We set out our methodology in Section 3, where we present an approach for comparing individual and county-level business cycle estimates. We describe the data in Section 4. The results are presented in Section 5. Section 6 concludes.

2. Background and literature

Various mechanisms have been suggested to explain why mortality may respond to fluctuations in the business cycle. Broadly speaking, however, the arguments that have been put forward for pro-cyclical mortality are similar to those for counter-cyclical mortality. For example, risky behaviors such as binge drinking and smoking have been argued to increase in economic expansions (Ruhm and Black, 2002; Dehejia and Lleras-Muney, 2004), as well as in economic downturns (Dee, 2001; Sullivan and von Wachter, 2009; Eliason and Storrie, 2009; Cotti et al., 2015; Hollingsworth et al., 2017). Similarly, although individuals may have less time to invest in their health when the economy is doing well (Ruhm, 2000), research suggests that individuals are happier and have a higher life satisfaction during economic booms (see e.g. Di Tella et al., 2003). Likewise, Ruhm (2000) argues that migration responds to local economic conditions by increasing the death rate in areas with larger numbers of migrants due to increased crowding, importing of disease, or unfamiliarity with the medical infrastructure, whereas others argue that migrants are generally high educated, healthy, and young (Kennedy et al., 2015). Finally, some argue that (job-related) stress increases in good economic times (Ruhm, 2000), whilst others suggest that there is more (job-related) stress in economic downturns (Brenner and Mooney, 1983). These mechanisms can be argued to have stronger effects on the working-age population, compared to e.g. the elderly. For example, job-related stress mainly affects those of working age. Likewise, the opportunity cost of leisure time increases for those of working age during economic upturns, whereas it stays relatively constant for those who are retired. Miller et al. (2009) find that neither stress levels nor health behaviors contribute to mortality fluctuations. Additionally, Cutler et al. (2016) argue that the contemporaneous impact of strengthened economic conditions on mortality is mixed due to a positive impact of greater income on health and a negative impact of pollution that accompanies more output.

Looking specifically at the relationship between macroeconomic conditions and health and health behaviors (rather than all-cause mortality), Dave and Rashad Kelly (2012) find that a one percentage point increase in the resident state’s unemployment rate is associated with a 3–6% reduction in the consumption of fruits and vegetables among those who are predicted to be at highest risk of being unemployed. Similarly, Ásgeirsdóttir et al. (2014) find that the Icelandic economic collapse in 2008 increased health-compromising behaviors, including smoking and heavy drinking, and decreased the consumption of fruit and vegetables. Tekin et al. (2013) find only weak evidence for a relationship between health behavior and economic activity around the time of the recent great recession.

A recent study by Ruhm (2013) finds that the procyclical relationship in Ruhm (2000) between the business cycle and mortality in the US has decreased in recent years. The study suggests that this is to some extent due to increases in countercyclical usage of medication and drugs that carry risks of fatal overdoses. Case and Deaton (2015) detect a dramatic rise in mortality among white midlife men in the US over the past 15 years and show that it is driven by similar causes. This rise in mortality is a secular phenomenon that took off in the 1990s, rather than a cyclical response. Case and Deaton (2015) show that this phenomenon was absent in Sweden, which means that our analysis is not affected by this.

We now briefly discuss the level of aggregation used in existing studies. As there is a vast literature on the relationship between mortality/health outcomes and the business cycle, we do not aim to give a comprehensive literature review, but instead discuss some of the key recent studies relevant to our paper. We generally distinguish between two types of studies, depending on the data used: those using aggregated (macro) data, and those using individual-level (micro) data. The studies we focus on that use macro-level (panel) data generally specify a fixed effects model, where regions (countries, states or counties) are observed over a number of years (see e.g. Ruhm, 2000; Gerdtham and Ruhm, 2006; Neumayer, 2004). These studies model the region-year-level mortality rate as a function of a measure of economic conditions, which also varies by region and year. Different measures have been used, including unemployment rates, and mean disposable incomes. The regional analyses then commonly control for other covariates, which are also averaged over regions and years, such as education (e.g. percentage high school dropouts, some college, college graduates), age groups, race and income.

The studies we focus on that use micro-level data typically observe a panel of individuals who are followed up for a number of years (see e.g. Gerdtham and Johannesson, 2005; Edwards, 2008). They model the binary indicator denoting whether the individual dies in that year as a function of a measure of economic conditions. Similar to the macro-level analysis, the latter is measured at a higher (e.g. state or county) level. They then commonly control for a similar set of covariates as above, but at the individual level (e.g. education, ethnicity, income and some polynomial in age).

Many factors may be able to explain the different, and sometimes opposite, findings in the literature. For example, the use of different regions, different time periods and business cycle indicators may lead to different findings. Similarly, the choice of covariates may affect the estimates of interest. Indeed, the studies mentioned above that use individual-level data generally do not include higher-level fixed effects, such as those at the state, region, or county level. Using individual-level data for example, Neumayer (2004) finds that mortality is pro-cyclical, but that the relationship is reversed when region fixed effects are not accounted for. Using both aggregate and individual-level data for the period 1977–2008, controlling for region fixed-effects, Haaland and Telle (2015) find that mortality is pro-cyclical both at the aggregate (regional) level as well as at the individual level. Not having access to regional unemployment rates for the period covered, however, leads the authors to use the number of registered unemployed in the region divided by the working-age population in the region rather than the labor force (those employed or seeking employment) as a proxy for regional economic conditions. The value of this measure is lower than the regional unemployment rates, as the working age population is larger than the labor force, which e.g. does not include students, disabled and housewives. Moreover, its cyclical fluctuations may differ and may reflect changes in the labor force participation not related to the business cycle.

3. An approach for comparing individual and county-level business cycle estimates

Consider the following models for the association between the business cycle and health:

| (1a) |

| (1b) |

where the subscripts i, j and t refer to the individual, region and time respectively and where denotes the regional mean of the individual-level covariate Xijt. The superscript refers to the individual (I) and aggregated (A) level of analysis. The micro-level dependent variable yijt is the binary indicator for individual i in region j having died at time t; the macro-level dependent variable yjt is the mortality rate (the number of deaths per 100,000 individuals) in region j and year t. In all models, region and year fixed effects (λj and τt respectively) are controlled for. The variable of interest, the business cycle (BC), is always measured at the county-level and varies with region and year. We follow the existing literature and use regional unemployment rates as the business cycle measure in our main specification. As argued by Ruhm (2000) and discussed above, the business cycle can affect mortality and health outcomes through its effect on individual behavior. For example, fluctuations in macroeconomic conditions may affect individuals’ time use, their health-behaviors, stress or levels of anxiety. The parameters δI and δA pick up the effects of these changes in individual behavior due to macroeconomic fluctuations.

We note that these analyses are similar to those used in the existing literature: studies that use longitudinal individual-level data tend to estimate models like (1a) (see e.g. Gerdtham and Johannesson, 2005; Edwards, 2008). Due to data limitations, however, most studies use longitudinal aggregate data (e.g. on states, counties or countries) to estimate models such as (1b) (see e.g. Ruhm, 2000; Gerdtham and Ruhm, 2006; Neumayer, 2004). As the business cycle is hypothesized to affect health outcomes (mortality) through its effect on individual behavior, our preferred model for estimating the association between the business cycle and mortality is the one at the individual level, i.e. (1a). Studies using aggregate data that estimate models such as (1b) and aim to draw conclusions about individual-level association between the business cycle and mortality can at best replicate the estimates of models like (1a). A natural question that arises is how accurately the aggregate data can infer effects of the business cycle on mortality at the individual level; that is, how good of an approximation δA is of δI in terms of sharing sign and magnitude of parameter estimates.

We start by estimating the following models:

| (2a) |

| (2b) |

where the subscripts i, j and t again refer to the individual, region (county) and time respectively. To allow for comparability between the models, the underlying data of the two specifications are identical, where (2b) is estimated on the micro data that has been collapsed to the regional level. In addition, to allow for a comparison of the magnitude of the model-coefficients, we estimate (2a) as a logit model, and (2b) as a Generalised Linear Model (GLM) using a logit link function with a Bernoulli distribution. In both analyses, we cluster the standard errors by region.3 Hence, the estimates of the coefficients γ in (2a) and (2b) are identical with this estimation procedure, since variation at region-year level theBCjt cannot explain variation at the individual level yijt within regions and years. For the same reason, inclusion of additional covariates that are quantified at the aggregate level will not lead to differences in the estimated coefficients between the individual and aggregate level. In other words, only the inclusion of individual-level covariates Xijt (and the corresponding at the aggregate level) can lead to differences between the micro and macro point-estimates. As we explained in detail in the introduction, this is a useful starting point to discuss various explanations for why results may vary with the degree of aggregation.

To proceed, we add covariates to the model, arriving at models (1a) and (1b) introduced above; that is, the models typically used in the literature. Employing models (2a) and (2b), yielding identical parameter estimates, provides a common point of reference for the parameter estimates which in turn allows us to study the extent of similarity between the models once further covariates are added. With this methodology we aim to close in on an answer to the question of how accurately models using aggregate data infer effects of the business cycle on mortality at the individual level.

4. Data

The analyses are mainly based on data from Statistics Sweden (population data) and the National Board of Health and Welfare (mortality). The main source of data from Statistics Sweden is the database “Longitudinal integration database for health insurance and labor market studies” (LISA by Swedish acronym), 1993–2007. The LISA database presently holds annual registers since 1990 and includes all individuals from 16 years of age and older that were registered in Sweden as of December 31 for each year. The database integrates existing data from the labor market, educational and social sectors. LISA is updated each year with a new annual register. We use a 20% random sample of the total male population in Sweden, aged 20–64,4 located in the 21 counties of Sweden. Clearly, the majority of deaths in the population occur above age 64. However, most of the mechanisms that have been suggested to explain why mortality responds to fluctuations in the business cycle (see Section 2) suggest that it is people within the labor force who are affected, rather than retired people. In Sweden in our data window, almost nobody stayed in the labor force after age 65 (contrary to the US). This therefore suggests that, in the case of Sweden, the mortality response to business cycle fluctuations can be expected to be concentrated among those of working-age. In addition to the individual-level data, county-level macroeconomic data on unemployment rates is collected from Statistics Sweden.

The upper part of Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics on mortality for the two age groups we consider. The mean mortality rate for 20–44 and 45–64 year old Swedish men, averaged over all years, is 0.0009 and 0.0054; or 90 and 540 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics on individual characteristics; mean (standard deviation).

| Age 20–44 | Age 45–64 | Alive | Dead | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||||||||

| All-cause mortality rate | 0.0009 | (0.0004) | 0.0054 | (0.0010) | ||||

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Age | 32.27 | (7.01) | 53.92 | (5.61) | 41.51 | (12.52) | 53.15 | (10.03) |

| 9–12 years education | 0.678 | (0.46) | 0.529 | (0.49) | 0.61 | (0.48) | 0.55 | (0.49) |

| 13–15 years education | 0.155 | (0.36) | 0.103 | (0.30) | 0.133 | (0.34) | 0.07 | (0.25) |

| 16+ years education | 0.129 | (0.33) | 0.146 | (0.35) | 0.137 | (0.34) | 0.074 | (0.26) |

| Employed | 0.875 | (0.33) | 0.825 | (0.37) | 0.85 | (0.35) | 0.55 | (0.49) |

| Single | 0.652 | (0.47) | 0.1943 | (0.39) | 0.456 | (0.49) | 0.35 | (0.47) |

| Divorced | 0.051 | (0.22) | 0.170 | (0.37) | 0.102 | (0.30) | 0.23 | (0.42) |

| Widowed | 0.001 | (0.02) | 0.013 | (0.11) | 0.006 | (0.07) | 0.01 | (0.13) |

| Family income (x100, in SEK) | 2529 | (5463) | 3110 | (5268) | 2780 | (5395) | 2107 | (1981) |

| # Days PT unemployed peryear | 3.61 | (28.12) | 2.013 | (22.91) | 2.93 | (26.05) | 1.39 | (17.61) |

| Registration at AF peryear | 3.36 | (24.89) | 2.987 | (26.47) | 3.19 | (25.53) | 6.56 | (38.39) |

| # Days unemployed per year | 25.81 | (65.15) | 14.85 | (56.58) | 21.12 | (61.86) | 19.98 | (63.86) |

| Number of individuals | 499 594 | 380 586 | 709 973 | 22 245 | ||||

Notes: reference categories are less than nine years education and married. The variable “Registration at AF per year” represents a registration for at least one of the following five sub-variables: Number of days unemployed, part time unemployed, registered at employment services, labor market activities or activity studies. The sample covers individuals living in Sweden’s 21 counties over a 15-year period.

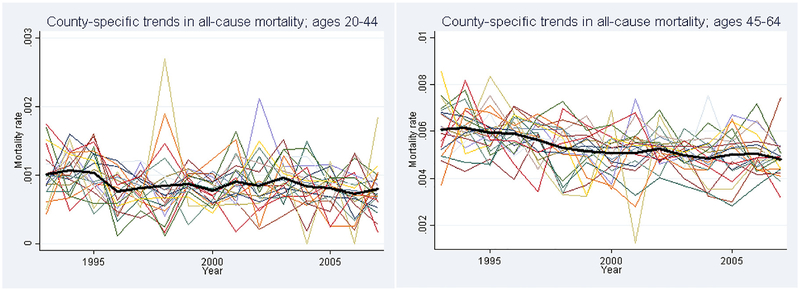

Fig. 1 shows the county-specific mortality rates for the two age groups over our observation period, showing considerable variation both within and between counties. The mortality rate over time, averaged over the 21 counties, is presented by the thick solid line, showing a slight reduction over time, particularly for 45–64 year olds.

Fig. 1.

County-specific trends in all-cause mortality by age group.

Notes: The figures show the county-level mortality rates over time by age group. The thick solid line is the average across the 21 counties.

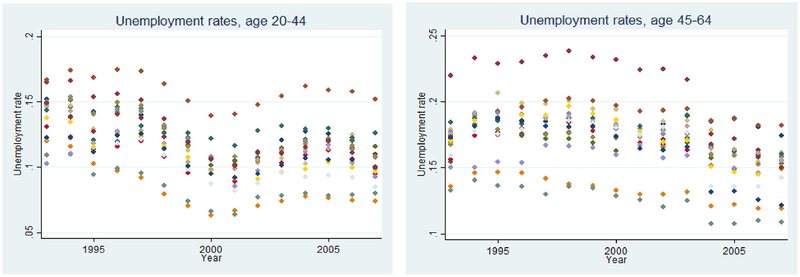

Fig. 2 presents individual-level unemployment status collapsed to the county-level by age group over our observation period. As shown, there is much variability both between counties and within counties across time. There is a clear cyclical pattern, particularly for unemployment among the younger age group. This shows a fall in unemployment rates in the late 1990s/early 2000s, with a rise in unemployment rates towards the middle of the 2000s.

Fig. 2.

Trends in county-level unemployment rates.

Notes: The figures show the average county-level unemployment rates over time by age group.

The lower part of Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics on the covariates, including individual age, educational level (less than 9 years of education, 9–12 years, 13–15 years, or 16+ years), family income (in 100 s SEK), binary indicators for being employed, being single/cohabiting, married, divorced and widowed, the number of days spent in part-time unemployment, full-time unemployment, and used to retrain for other jobs. We also observe and control for the industry the individual is employed in (not shown here). Columns 1 and 2 show the descriptive statistics for the 20% random sample distinguishing between the two age groups (20–44 and 45–64 year olds). Columns 3 and 4 show the summary statistics for the sample that is alive and those who die within our observation period.

The average age among those alive is 41.5 and it is 53 among those who die. About 87% of the younger age group are employed whereas 5 percentage points less are employed among those of 45–64 years of age.

5. Results

We start by presenting our results from the individual-level analysis, as in Eq. (2a), distinguishing between the two age groups. Next, we present the findings from the county-level analysis, collapsing the individual-level data to the county-level.

5.1. Individual-level analysis

Table 2 shows the findings for the analyses at the individual-level. Our baseline measure of economic conditions is regional unemployment rates. The robustness of the results to different business cycle indicators is shown below (Section 5.3). We report the results controlling for county and year fixed effects as well as county-specific time trends, though the findings are robust to the exclusion of county-specific time trends.

Table 2.

Individual-level analyses with unemployment rate as business cycle indicator.

| 20–44yearolds | 45–64 year olds | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| County-level measure of the business cycle | −6.999* | −7.004* | −7.363* | 1.663 | 1.555 | 1.516 |

| (4.023) | (3.986) | (4.082) | (1.567) | (1.565) | (1.483) | |

| Log-Likelihood | −31649 | −30663 | −29690 | −113777 | −108827 | −106609 |

| Region and year fixed effects and regional time trends | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Individual age, education, marital status | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Individual employment and income | N | N | Y | N | N | Y |

Notes: The measure of the business cycle is regional unemployment rates. Individual employment controls in column (3) and (6) refer to employment status, number of days in unemployment, retraining and industry employed in. The panel consists of 21 counties and 15 years where number of (individual*year) observations for 20–44 year olds is 4. 538. 832 and for 45–64 year olds 3. 398.161. Robust standard errors in parentheses, clustered by county.

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

Column 1 in Table 2 shows the raw correlation between individual-level mortality and economic conditions for 20–44 year old men, controlling only for county and year fixed effects and county-specific time trends. Column 4 shows the same analysis for the 45–64 year old group of men.

The findings indicate a pro-cyclical association between individual-level mortality and economic conditions for the younger age group, although significant only at the 10 percent significance level. A one standard deviation increase in county unemployment is associated with an odds of dying of 0.875 (e−0.1232) for 20–44 year olds, or a reduction in mortality of 12%.5 For 45–64 year olds, the parameter estimate has a positive sign and is not significant. Columns 2 and 5 then account for age, educational level and dummies for marital status. As such, the model comprises the demographic covariates typically controlled for in the literature on business cycles and mortality (Ruhm, 2000). Controlling for these individual-level background characteristics produces estimates similar in magnitude to those in column 1 and 4 for both age groups. In columns 3 and 6 the control strategy goes one step further compared to what covariates that are typically controlled for by in addition including employment controls in terms of employment status, the number of days in the year that the individual is in part-time unemployment, in full-time unemployment, and retraining for other jobs and dummies indicating the industry the individual is employed in, as well as family income. The parameter estimate for age group 20–44 increases somewhat in magnitude and remains significant at the 10 per cent level. Similar to the first specification presented in column 1, a standard deviation increase in unemployment is associated with a 13% reduction in mortality. Colum (6) indicates that mortality among men in age group 45–64 is not influenced by the economic conditions. Hence, the findings suggest that macroeconomic conditions mainly affect the younger working-age population, rather than those closer to retirement.

5.2. County-level analysis

We now turn to the county-level analysis, using the mortality rate at the county-year as the dependent variable. The measure of economic conditions remains the same as that above. Table 3 below presents the results for the county-level analyses, with columns 1–3 showing the estimates for the group of 20–44 year olds, and columns 4–6 showing that for 45–64 year olds.

Table 3.

County-level analyses with unemployment rate as business cycle indicator.

| 20–44yearolds | 45–64 year olds | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| County-level measure ofthe business cycle | −6.999* | −5.581* | −7.675** | 1.663 (1.567) | 2.316 | 2.306 |

| (4.023) | (3.274) | (3.289) | (1.645) | (1.813) | ||

| Log-Likelihood | −1.923 | −1.923 | −1.922 | −8.861 | −8.860 | −8.859 |

| Region and year fixed effects and regional time trends | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Regional mean age, education, marital status | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Regional income trend and employment controls | N | N | Y | N | N | Y |

Notes: The measure of the business cycle is regional unemployment rates. Regional employment controls in column (3) and (6) refer to county-level collapsed individual number of days in unemployment, retraining and industry employed in. Regional income refers to trend in mean regional income obtained from the HP filter. The panel consists of 21 counties and 15 years where number of (region*year) observations for 20–44 year olds as well as 45–64 year olds is 315. Robust standard errors in parentheses, clustered by county.

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

With the same underlying data to that used in the analyses presented in Table 2, but collapsed to the county-level, the estimates in columns 1 and 4 are identical to the individual-level findings described above (i.e. columns 1 and 4 of Table 2); hence again indicating a pro-cyclical association between mortality and economics conditions for men of 20–44 years of age.

Turning to columns 2 and 4, covariates of mean regional demographics are introduced as control variables. As shown, the parameter estimates share the same sign and are rather close in magnitude to those in the individual-level analysis. Column 3 and 6 add individual-level employment and income controls collapsed to the county level. In order to avoid including covariates that may themselves capture the business cycle effect however, regional employment is excluded from model, as this is clearly highly correlated to our measure of economic activity. The cyclical variation in regional income is teased out of the collapsed individual-level income so that the variables only account from the trend in mean regional income using the HP filter. Compared to specification 2 and 4 the estimates increase somewhat in magnitude while the effects become significant at the 5 percent level for 20–44 year olds. A one standard deviation increase in unemployment is associated with a 13 percent reduction in mortality. In other words, mortality is significantly pro-cyclical among the younger working-age population, while the effect is absent among the population closer to retirement. Our analyses suggest indeed that using aggregate regional-level data accurately captures the association between the business cycle and mortality at the individual level.

5.3. Extended analysis on cyclical variation

Most studies in the business cycle and health nexus literature rely on levels of macroeconomic time series as indicators of the business cycle; for example (the level of) the unemployment rate (e.g. see Ruhm, 2000). In the macroeconomic literature however, the business cycle is defined as short-run fluctuations in economic activity around a long-term economic trend (see e.g. Sorensen and Whitta-Jacobsen, 2010). This definition states that there are (at least) two forces at play in most macroeconomic time series, as opposed to one (that is, as opposed to just the level of the variable). We capture these distinctly different behaviors in the observed macroeconomic time series, denoted Et, using an additive model in which the time series is modeled as the sum of the two basic components: the time series long-run trend Tt and its short-run cyclical fluctuations BCt:

| (3) |

Thus, the observed macroeconomic time series is decomposed as the sum of a trend component Tt and a cyclical component BCt; with the cyclical component BCt representing the business cycle. Relying on Et as the business cycle indicator may be troublesome as it includes in addition to the cyclical variation also the contribution of the time series trend component Tt, that includes variation from sources unrelated to the business cycle, notably effects of secular changes in society, or slow modifications in how unemployment is defined or measured, confounding the measurement of the business cycle. In the following sensitivity analyses, we therefore identify the business cycle using solely the cyclical BCt component.

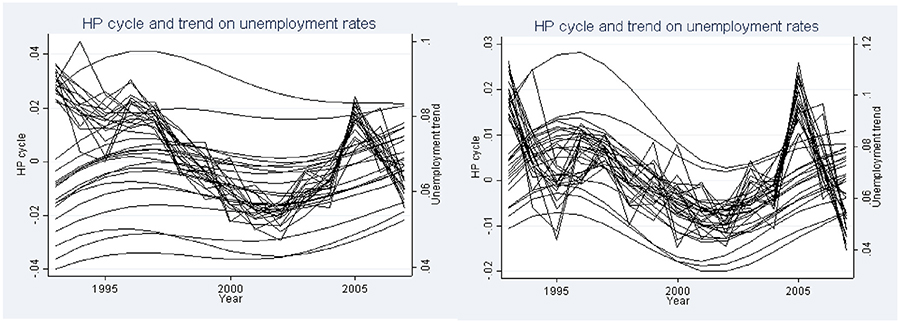

Note that we do not observe the cyclical and trend component of the macroeconomic indicator directly. We therefore need a method that allows us to tease out the trend component Tt and the cyclical component BCt from the observed time series. To this end, we use the Hodrick-Prescott (HP) filter. In this context, one advantage of using the official unemployment rate data from Statistics Sweden, rather than collapsing the individual-level unemployment indicator, is that the former cover a longer time series, which allows us to run the HP filter on a longer time interval (1976–2014), increasing the accuracy of the filter.6 Moreover, using official unemployment rates, rather than collapsing the individual-level unemployment indicator, circumvents the problem of having to measure which of the non-working individuals are a member of the labor force and which are not. The estimated cycles and trends of the HP filter using county-level unemployment rates are presented in Fig. 3 using a smoothing parameter of 100 and 6.25 respectively; the means and standard deviations of our business cycle measures are shown in Appendix A in Table A1. A smoothing parameter of 6.25 is suggested by Ravn and Uhlig (2002) for annual data. However, plotting the estimates using this smaller smoothing parameter shows clear cyclicality in the trend estimates, as shown in the right panel of Fig. 3, suggesting it is not sufficient to smooth out all cyclicality. Our preferred specification therefore applies more smoothing.

Fig. 3.

County-level trends and cycles in unemployment rates.

Notes: The figures show the county-level trends and cycles in unemployment rates obtained from the HP filter over time. Data on county-level unemployment rates is obtained from Statistics Sweden.

A sharp improvement (i.e. reduction) in cyclical unemployment is shown from the early 1990s until early 2000s after which cyclical unemployment increases for a few years to drop again after 2005. The smooth lines show that the county-level trends during the observation period are similar across all counties, albeit the levels of the trends differ across regions.

Table 4 presents the estimates from the individual-level analyses. We test the robustness of the results using our measures of the business cycle where the cycle component is extracted from the unemployment rates.

Table 4.

Robustness analyses at the individual-level, using different business cycle indicators.

| 20–44 year olds | 45–64yearolds | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Panel A: Individual−level analysis | ||||||

| Measure ofthe business cycle, cyclical unemployment rate (HP λ = 100) | −8.047* | −7.967** | −8.207** | 1.436 | 1.549 | 1.512 |

| (4.106) | (4.058) | (4.135) | (1.759) | (1.806) | (1.721) | |

| Log-Likelihood | −31649 | −30663 | −29690 | −113777 | −108827 | −106609 |

| Panel B: Individual-level analysis | ||||||

| Measure ofthe business cycle, cyclical unemployment rate (HP λ = 6.25) | −8.487** | −8.360** | −8.314** | 1.589 | 1.743 | 1.821 |

| (4.283) | (4.209) | (4.222) | (2.095) | (2.128) | (2.093) | |

| Log-Likelihood | −31649 | −30664 | −29691 | −113777 | −108827 | −106609 |

| Region and year fixed effects and regional time trends | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Individual age, education, marital status | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Individual employment and income | N | N | Y | N | N | Y |

Notes: The measure of the business cycle is obtained from the HP filter on regional unemployment rates. (HP) refers to the value of the smoothing parameter in the HP filter. Individual employment controls in column (3) and (6) refer to employment status, number of days in unemployment, retraining and industry employed in. The panel consists of 21 counties and 15 years where number of (individual*year) observations for 20–44 year olds is 4. 538. 832 and for 45–64 year olds 3.398.161 Robust standard errors in parentheses, clustered by county.

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

Panel A displays the results using the cyclical component extracted using a smoothing parameter of 100. The findings are similar to those presented in Table 2 in terms of sharing sign albeit the magnitude of the parameters estimates differ somewhat. The level of significance is higher in column (2) and (3) compared to when unemployment rates are used as a measure of economic conditions. A one standard deviation increase in cyclical unemployment is associated with an odds of dying of 0.881 (e−0.155) for 20–44 year olds, or a reduction in mortality of 12%

In panel B we show that the results are robust to applying less smoothening (λ = 6.25 as suggested by Ravn and Uhlig, 2002), in which a lower weight is to given to the trend. A standard deviation increase in cyclical unemployment is associated with a reduction in mortality for 20–44 year olds by approximately 7% (i.e. an odds of dying of 0.933 (or e(−8.314 × 0.0082) = e−0.068), where 0.0082 is the standard deviation of cyclical unemployment taken from Table A1 in the Appendix A). However, as indicated in Fig. 3, displaying the HP filter outcomes using this smaller smoothing parameter, the trend estimates clearly contain cyclical variation hence absorbing information of the business cycle that we wish to capture by the cyclical component; again, suggesting such value of the smoothing parameter is not sufficient to smooth out all cyclicality in this case. Our preferred measure of the business cycle is therefore the one presented in panel A.

Table 5 above presents the results using cyclical variation as a measure of the business cycle, estimated on the region-year level data. Similar to Table 4, panels A and B specify the business cycle based on cyclical unemployment rates with a smoothing parameter of 100 and 6.25 respectively. The estimates confirm our earlier analyses: with identical estimates in columns 1 and 4 to those in Table 4 (by construction), providing us with a reference point for comparing estimates of subsequent models, we find that mortality is pro-cyclical, accounting for regional economic activity using measures based on cyclical unemployment rates. Once we adjust for average regional-level demographics the estimates change only somewhat in magnitude while sharing the same sign. This suggests that an analysis based on aggregated region-year level data indeed provides adequate estimates for the individual-level association between the business cycle and mortality. This also holds when controls for individual (and their county-level counterparts) employment characteristics and income are added to the models. Therefore, the inclusion of additional higher-level covariates that are correlated with the business cycle measure does not seem to confound higher-level business cycle estimates. This would suggest that we in this context can rely on aggregated analyses to infer associations between the business cycle and mortality at the individual level.

Table 5.

Robustness analyses at the county-level, using different business cycle indicators.

| 20–44yearolds | 45–64year olds | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Panel A: County-level analysis | ||||||

| Measure of the business cycle, cyclical unemployment rate (HP 100) | −8.047* | −6.155* | −7.614** | 1.436 | 2.154 | 2.212 |

| (4.106) | (3.485) | (3.632) | (1.759) | (1.809) | (1.957) | |

| Log-Likelihood | −1.923 | −1.923 | −1.922 | −8.861 | −8.860 | −8.859 |

| Panel B: County-level analysis | ||||||

| Measure of the business cycle, cyclical unemployment rate (HP 6.25) | −8.487** | −7.408* | −8.775** | 1.589 | 2.308 | 2.769 |

| (4.283) | (3.958) | (4.269) | (2.095) | (2.125) | (2.369) | |

| Log-Likelihood | −1.923 | −1.923 | −1.922 | −8.861 | −8.860 | −8.859 |

| Region and year fixed effects and regional time trends | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Regional mean age, education, marital status | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Regional income trend and employment controls | N | N | Y | N | N | Y |

Notes: The measure of the business cycle is obtained from the HP filter on regional unemployment rates. (HP) refers to the value of the smoothing parameter in the HP filter. Regional employment controls in column (3) and (6) refer to county-level collapsed individual number of days in unemployment, retraining and industry employed in. Regional income refers to trend in mean regional income obtained from the HP filter. The panel consists of 21 counties and 15 years where number of (region*year) observations for 20–44 year olds as well as 45–64 year olds is 315. Robust standard errors in parentheses, clustered by county.

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

5.4. Subgroup analyses

To explore whether the effect of macroeconomic conditions differentially affects different types of individuals, we run a set of subgroup analyses. Table 6 presents the estimates by subgroup at the individual level. We show the findings for four separate income quartiles, four education groups, by marital status, and by employment status. All analyses control for the full set of individual-level background characteristics discussed above. Columns 1–4 show the findings for 20–44 year old men; columns 5–8 present the results for men aged 45–64. The results from the corresponding regional-level analyses are found in Table A2 in the Appendix A.

Table 6.

Individual-level analyses, using unemployment rate as the county-level business cycle indicator, by subgroups.

| 20–44yearolds | 45–64 yearolds | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Panel A: Individual-level analysis, by income quartiles | Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 |

| All-cause mortality rate | 0.0018 | 0.0007 | 0.0006 | 0.0005 | 0.0107 | 0.0053 | 0.0033 | 0.0023 |

| County-level measure ofthe business cycle, unemployment rate | −11.02** | 5.126 | 1.247 | −21.07 | 1.711 | −0.734 | 3.639 | 0.478 |

| (4.597) | (8.283) | (7.033) | (13.46) | (2.892) | (3.234) | (4.639) | (4.922) | |

| No. ofobservations | 1 134 272 | 1 134 667 | 1 134 204 | 1 133 241 | 849 543 | 849 500 | 849 121 | 849 381 |

| Panel B: Individual-level analysis, by education group | < 9 years | 9−12 years | 13−15 years | >15 years | < 9 years | 9−12 years | 13−15 years | >15 years |

| All-cause mortality rate | 0.0017 | 0.0010 | 0.0005 | 0.0004 | 0.0085 | 0.0052 | 0.0035 | 0.0029 |

| County-level measure ofthe business cycle, unemployment rate | 1.379 | −9.090** | −4.131 | −4.353 | 1.866 | 2.504 | 4.732 | −7.384 |

| (2.599) | (4.216) | (16.947) | (12.138) | (2.720) | (1.674) | (5.852) | (6.039) | |

| No. ofobservations | 161 471 | 3 080 290 | 702 556 | 576 716 | 747 278 | 1 799 639 | 352 006 | 498 487 |

| Panel C: Individual-level analysis, by marital status | Married | Single | Divorced | Widowed | Married | Single | Divorced | Widowed |

| All-cause mortality rate | 0.0005 | 0.0094 | 0.0018 | - | 0.0038 | 0.0077 | 0.0084 | 0.0085 |

| County-level measure ofthe business cycle, unemployment rate | 4.420 | −9.763* | −8.339 | - | 0.188 | 1.058 | 5.629* | −6.941 |

| (11.12) | (5.141) | (7.339) | - | (2.599) | (3.230) | (3.079) | (9.292) | |

| No. ofobservations | 1 339 556 | 2 960 500 | 232 506 | - | 2 111764 | 660 482 | 579 717 | 44 582 |

| Panel D: Individual-level analysis, by employment status | Unemployed | Employed | Unemployed | Employed | ||||

| All-cause mortality rate | 0.0028 | 0.0006 | 0.0139 | 0.0036 | ||||

| County-level measure ofthe business cycle, unemployment rate | −13.075* | −3.204 | 0.277 | 2.688 | ||||

| (6.824) | (3.850) | (2.405) | (1.785) | |||||

| No. ofobservations | 564 514 | 3 972 266 | 592 774 | 2 805 387 | ||||

| Region and year fixed effects and regional time trends | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Individual age, education, marital status | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Individual employment and income | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Notes: The measure of the business cycle is regional unemployment rates. Individual employment controls refer to employment status, number of days in unemployment, retraining and industry employed in. The panel consists of 21 counties and 15 years where number of (individual*year) observations for 20–44 year olds and 45–64 year olds for each subgroup is presented in the table. Robust standard errors in parentheses, clustered by county.

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

Panel A, columns 1–4, show significant pro-cyclical variation in mortality for individuals in the lowest income quartile, with a standard deviation increase in the unemployment rate being associated with an 19% (e−0.209) reduction in mortality. Thus, this indicates that socioeconomic inequality in mortality decreases in downturns while it increases during economic booms. As for the two different age groups, the findings are consistent in that it is only the younger age group with 20–44 year old men that is affected by the business cycle. The regional-level estimates are consistent with the ones at the individual-level, as shown in Table A2 in the Appendix A.

The analyses by education, presented in Panel B, show a similar pattern in that a business cycle effect is only present in the lower age group, and only for those with 9–12 years of education.

Panel C presents the results for subgroups based on marital status. The findings show that the pro-cyclical effect indicated by prior analyses is present only for single 20–44 year olds. Interestingly, a counter-cyclical effect is visible for divorced 45–64 year olds, but the effect is rather small. Of course, marital status can be affected by the expectation of future mortality, and therefore these results should be interpreted with caution. The same applies to the analysis by employment status. We find that mortality among unemployed 20–44 year olds is sensitive to variations in the business cycle. There is no effect among the 45–64 year olds, confirming that economic conditions do not affect mortality in this age group. At the regional-level however, Table A.2 in the Appendix A, there is no significant effect on singles, while it is among the employed a significant association between the business cycle and mortality is found. These results stand out in our analyses in that there is a discrepancy between the individual-level and regional-level estimates of the association between economic conditions and mortality.

Overall, the subgroup analyses thus find a social gradient in the response to macro-economic fluctuations for younger individuals in that the business cycle effect on mortality is present only among those in the lowest income quintile and among those with low education.

6. Conclusion

There has been a renewed interest in the relationship between economic conditions and mortality. The literature provides mixed evidence, with some studies finding support for the suggestion that mortality increases with improvements in economic conditions, and others finding the opposite. One of the differences between these studies is level of analysis: studies using aggregated data tend to find that mortality is pro-cyclical, whereas studies that use individual-level data tend to find the opposite.

Using both individual-level and aggregated data on a sample of Swedish working-age men sheds light on this issue. With procyclical mortality effects of similar magnitude at both the individual level and the regional level, our analyses show that estimates of the relationship between mortality and the business cycle are not sensitive to the level at which the dependent variable is measured. This finding suggests that it is not the different levels of analyses that drive some of the conflicting findings in the literature.

Our estimates at both the individual and regional level suggest that a 1 standard deviation increase in the unemployment rate reduces mortality (odds ratio) by around 12% among 20–44 year old men. In contrast, we find no differences in mortality for 45–64 year old men, suggesting that the business cycle mainly affect the younger working-age population, rather than those closer to retirement. One reason for this may be the fact that older workers are more likely to have permanent positions, and with that increased job security. Any fluctuations in the business cycle are therefore less likely to affect older workers’ (e.g.) levels of stress of anxiety, compared to the younger working-age population. Furthermore, we find a social gradient in the response to the business cycle, with the lower socio-economic groups being more affected.

Our results suggest some topics for future research. First, the results in the paper as well as those in the literature depend on the additive functional form for the relation between mortality and its determinants. It is an open question to what extent the empirical findings generalize to more flexible specifications. Furthermore, in a longitudinal setting, time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity (or an individual-specific fixed effect) leads to dynamic mortality selection over time. It is conceivable that the speed of selection within a cohort depends on the state of the business cycle, leading to systematic changes in the composition of survivors. It is not straightforward to reconcile this with the commonly used model specification, but it may go some way in explaining that while we find strong pro-cyclical effects for the ages up to 44, the effects are counter-cyclical and insignificant for the ages 45–65. Clearly, it would be interesting to explore this empirically in a more formal fashion.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the Swedish Research Council (dnr 2014–646) is gratefully acknowledged. The Health Economics Program (HEP) at Lund University also receives core funding from Government Grant for Clinical Research (“ALF”), and Region Skåne (Gerdtham). Research reported in this publication was also supported by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HL116381 to Kristina Sundquist. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix A. Additional Tables

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics of business cycle measures.

| Unemployment rate | 0.0642 | (0.019) |

| HP 100 | ||

| Cyclical unemployment | 0.0029 | (0.0154) |

| Trend unemployment | 0.0612 | (0.0108) |

| HP 6.25 | ||

| Cyclical unemployment | 0.0013 | (0.0082) |

| Trend unemployment | 0.0628 | (0.0140) |

Notes: Means and standard deviations (in parentheses) of the business cycle indicators. The number of counties is 21 and number of year is 15 where number of (region*year) observations is 315.

Table A2.

Regional-level analyses, using unemployment rate as the county-level business cycle indicator, by subgroups.

| 20–44year olds | 45–64yearolds | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Panel A: County-level analysis, by income quartiles | Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 |

| All-cause mortality rate | 0.0018 | 0.0007 | 0.0006 | 0.0005 | 0.0107 | 0.0053 | 0.0033 | 0.0023 |

| County-level measure of the business cycle, unemployment rate | −12.034** | 10.806 | −0,093 | −23.08 | 1.077 | −0.438 | 3.318 | 4.684 |

| (5.245) | (5.374) | (9.321) | (16.16) | (3.52) | (3.234) | (4.717) | (3.666) | |

| Panel B: County-level analysis, by education group | < 9 years | 9−12years | 13−15 years | >15 years | < 9 years | 9−12years | 13−15 years | >15 years |

| All-cause mortality rate | 0.0017 | 0.001 | 0.0005 | 0.0004 | 0.0085 | 0.0052 | 0.0035 | 0.0029 |

| County-level measure of the business cycle, unemployment rate | 5.888 | −9.364** | −1.316 | −13.89 | 0.298 | 2.95 | 1.739 | −5.699 |

| (16.654) | (3.93) | (1.788) | (11.506) | (2.943) | (2.332) | (6.057) | (6.116) | |

| Panel C: County-level analysis, by marital status | Married | Single | Divorced | Widowed | Married | Single | Divorced | Widowed |

| All-cause mortality rate | 0.0005 | 0.0094 | 0.0018 | - | 0.0038 | 0.0077 | 0.0084 | 0.0085 |

| County-level measure of the business cycle, unemployment rate | 9.306 | −4.824 | −13.062 | - | 1.157 | −2.87 | 6.198* | 4.017 |

| (10.776) | (4.992) | (8.571) | - | (2.661) | (3.284) | (3.188) | (9.798) | |

| Panel D: County-level analysis, by employment status | Unemployed | Employed | Unemployed | Employed | ||||

| All-cause mortality rate | 0.0028 | 0.0006 | 0.0139 | 0.0036 | ||||

| County-level measure of the business cycle, unemployment rate | −9.112 | −6.938** | 0.669 | 3.083 | ||||

| (6.437) | (3.541) | (2.661) | (2.11) | |||||

| Region and year fixed effects and regional time trends | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Regional mean age, education, marital status | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Regional income trend and employment controls | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Notes: The measure of the business cycle is regional unemployment rates. Regional employment controls refer to county-level collapsed individual number of days in unemployment, retraining and industry employed in. Regional income refers to trend in mean regional income obtained from the HP filter. The panel consists of 21 counties and 15 years where number of (region*year) observations for 20–44 year olds as well as 45–64 year olds is 315. Robust standard errors in parentheses, clustered by county.

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

Footnotes

An exception is Haaland and Telle (2015) who find that mortality is pro-cyclicalboth at the aggregate regional level as well as at the individual level. As we shallexplain, they use slightly different aggregate cyclical measures than most studies.Lindo (2015) emphasizes the importance of the geographical level of aggregationused to capture aggregate economic conditions. Throughout the current paper westick to the county level as the relevant unit.

Also, it is clear that the estimates may end up being different if different datasources are used for covariates at different aggregation levels, especially if theobserved values at the macro level do not correspond to the aggregates of theobserved micro-level values. Likewise, estimates may differ if aggregated versionsof covariates at the individual level are omitted in the macro-level analysis. Thismay concern e.g. region-specific fixed effects. These explanations may explain somefindings in the literature, but in our analyses they are ruled out by construction.

We observe a relatively small number of regions (21 counties). Even withcluster-robust standard errors, Wald tests tend to over-reject, the extent of whichdepends on how few clusters there are, as well as the data and model used, whichshould be taken into account when interpreting the results. For more informationon cluster-robust inference, we refer the reader to Cameron and Miller (2015).

Our access to these data is restricted to the male working-age population; wetherefore cannot show similar analyses on the female population, or on differentage groups. As the majority of deaths occur in the elderly population, the focus on20–64 year olds inevitably includes a more limited number of deaths. However, aswe discuss below, the working-age population is a very relevant group to study, inparticular in Sweden.

That is, a 12% reduction in the odds of dying, calculated as 1 −e(coefficient estimatex standard deviation of variable).

The HP filter output is unreliable near the endpoints of the data set. Increasingthe observation window around our period of interest (1993–2007) in the macroe-conomic county dataset deals with this.

References

- Ásgeirsdóttir T, et al. , 2014. Was the economic crisis of 2008 good for Icelanders? Impact on health behaviours. Econ. Hum. Biol 13, 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner MH, Mooney A, 1983. Unemployment and health in the Context of Economic Change. Soc. Sci. Med XVII, 1125–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron AC, Miller DL, 2015. A practitioner’s guide to cluster-Robust inference. J. Hum. Resour 50 (2), 317–372. [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Deaton A, 2015. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21 st century. PNAS 112, 15078–15083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotti C, Dunn R, Tefft N, 2015. The Dow is killing me: risky health behaviours and the stock market. Health Econ. 24 (7), 803–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler DM, Huang W, Lleras-Muney A, 2016. Economic conditions and mortality: evidence from 200 years of data. NBER Working Paper 22690. [Google Scholar]

- Dave DM, Rashad Kelly I, 2012. How does the business cycle affect eating habits? Soc. Sci. Med 74 (2), 254–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dee TS, 2001. Alcohol abuse and economic conditions: evidence of repeated cross-Sections of individual-level data? Health Econ. 10 (3), 257–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehejia R, Lleras-Muney A, 2004. Booms, busts and babies’ health. Q. J. Econ 119(3), 1091–1130. [Google Scholar]

- Di Tella R, MacCulloch RJ, Oswald AJ, 2003. The macroeconomics of happiness. Rev. Econ. Stat 85 (4), 809–827. [Google Scholar]

- Economou A, et al. , 2008. Are recessions harmful to health after all? evidence from the european union. J. Econ. Stud 35 (5), 368–384. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards R, 2008. Who is hurt by procyclical mortality? Soc. Sci. Med 67,2051–2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliason M, Storrie D, 2009. Does job loss shorten life? J. Hum. Resour 44 (2),277–302. [Google Scholar]

- Gerdtham U-G, Johannesson M, 2005. Business cycles and mortality: results from swedish microdata. Soc. Sci. Med 60 (1), 205–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdtham U-G, Ruhm C, 2006. Deaths rise in good economic times: evidence from the OECD. Econ. Hum. Biol 4 (3), 298–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haaland VF, Telle K, 2015. Pro-cyclical mortality across socioeconomic groups and health statu. J. Health Econ 39, 248–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth A, Ruhm CJ, Simon K, 2017. Macroeconomic conditions and opioid abuse. national bureau of economic research. Working Paper No. 23192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S, Kidd M, McDonald J, Biddle N, 2015. The healthy immigrant effect: patterns and evidence from four countries. J. Int. Migr. Integr 16 (2), 317–322. [Google Scholar]

- Lindo JM, 2015. Aggregation and the estimated effects of economic conditions on health. J. Health Econ 40, 83–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller D, Page M, Huff Stevens A, Filipski M, 2009. Why are recessions good for your health? Am. Econ. Rev. Pap. Proc 99 (2), 122–127. [Google Scholar]

- Neumayer E, 2004. Recessions lower (some) mortality rates: evidence from Germany? Soc. Sci. Med 58 (6), 1037–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravn MO, Uhlig H, 2002. On adjusting the Hodrick-Prescott filter for the frequency of observations. Rev. Econ. Stat 84 (2), 371–376. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhm CJ, Black WE, 2002. Does drinking really decrease in bad times? J. Health Econ 21 (4), 659–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhm CJ, 2000. Are recessions good for your health? Q. J. Econ 115 (2), 617–650. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhm CJ, 2013. Recessions, healthy No more? NBER Working Paper 19287. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen BP, Whitta-Jacobsen HJ, 2010. Introducing Advanced Macroeconomics: Growth and Business Cycle. McGraw-Hill Higher Education. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan D, von Wachter T, 2009. Job displacement and mortality: an analysis using administrative data. Q. J. Econ, 1265–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson M, 2007. Do not go Breaking your heart: do economic upturns really increase heart attack mortality? Soc. Sci. Med 64 (4), 833–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia Granados JA, 2005. Increasing mortality during the expansions of the US economy? Int. J. Epidemiol 34 (6), 1194–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia Granados JA, 2008. Macroeconomic fluctuations and mortality in postwar Japan. Demography 45 (2), 323–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekin E, McClellan C, Minyard KJ, 2013. Health and health behaviors during the worst of times: evidence from the great recession. NBER Working Paper 19234. [Google Scholar]