Abstract

Introduction

This study estimated the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for Mini Mental State Examination, Clinical Dementia Rating Scale sum of boxes, and Functional Activities Questionnaire across the Alzheimer's disease (AD) spectrum.

Methods

Retrospective analysis of the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set (9/2005-9/2016) and MCID for clinical outcomes were estimated using anchor-based (clinician's assessment of meaningful decline) and distribution-based (1/2 baseline standard deviation) approaches, stratified by severity of cognitive impairment.

Results

On average, a 1-3 point decrease in Mini Mental State Examination, 1-2 point increase in Clinical Dementia Scale sum of boxes, and 3-5 point increase in Functional Activities Questionnaire were indicative of a meaningful decline. The MCID values generally increased by disease severity; the effect size and standardized response mean for those with meaningful decline were consistently in the acceptable ranges for MCID.

Discussion

These findings can inform design and interpretation of future clinical trials.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, MCID, MMSE, CDR, FAQ, Meaningful decline

1. Introduction

A key challenge in clinical trials to evaluate the effects of interventions related to Alzheimer's disease (AD) and dementia is to assess the clinical—rather than statistical—significance of differences in outcomes across trial cohorts. [1] The concept of a minimal clinically important difference (MCID)—also known as minimal important difference, minimal clinically relevant change, or minimum detectable change [2]—can be valuable in this context. MCID is “the smallest difference in score in the domain of interest which patients perceive as beneficial and which would mandate, in the absence of troublesome side effects and cost, a change in patient's management.” [3] Information about whether a proposed intervention has the potential to provide meaningful clinical benefits relative to comparators is important in the evaluation of clinical trials [4] and is of great value to patients, caregivers, and healthcare decision makers including treating physicians.

Despite this, empirical evidence regarding MCID estimates across various clinical outcome assessments designed to measure cognition, function, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and other global outcomes in clinical trials related to dementia is limited [1], [5]. A recent review of the literature found that only 46% of the 57 trials evaluating dementia drugs reported the clinical significance of their results [1]. In addition, there is no standardized method for estimating MCID [4], [6], [7], [8]. Two commonly used approaches to estimate MCID are: (1) an anchor-based approach, in which a change in an outcome measure is linked to a meaningful external anchor, largely corresponding to patient perception, or in case of dementia research, clinical opinion; (2) distribution-based approaches specific to clinical trial populations, in which the MCID is calibrated based on observed variation across patients enrolled in the clinical trials.

Both of these approaches have been used in clinical trials for dementia, but there is considerable variation in the resulting MCID estimates. For example, one study involving a survey of neurologists and geriatricians reported a mean MCID for the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) of 3.75 (95% confidence interval: 3.5-3.95) [9]. By comparison, using data from the DOMINO trial, Howard et al. estimated the MCID thresholds for MMSE and neuropsychiatric inventory (NPI) to be 1.4 and 8.0 points, respectively [10]. An additional challenge is that estimates of MCID—and in particular those using distribution-based approaches—may not generalize to other populations whose characteristics differ from the underlying study population. Furthermore, for progressive conditions like AD, it is possible that MCID estimates may differ across the disease continuum, with the different stages of cognitive impairment associated with a different calibration of the MCID [4], [11].

To address these gaps in the literature, this study examined the MCID for the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Scale sum of boxes (SB) score, the MMSE, and the Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ) for patients on the AD continuum who visit various Alzheimer's Disease Centers (ADCs) across the US. The study considered both anchor-based and distribution-based approaches, consistent with recommendations that describe the incorporation of both methods to estimate MCIDs [12]. The findings are reported overall and stratified by degree of cognitive impairment at the time of initial evaluation.

2. Methods

2.1. Data

The study used publicly available Uniform Data Set (UDS) from the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center (NACC), which comprises data from 35 past and present ADCs supported by the National Institute on Aging/National Institute of Health [13]. The NACC, established in 1999, maintains a cumulative database including clinical evaluations, neuropathological data (when available) and magnetic reonnance imaging. The UDS reflects the total enrollment at the ADCs since September 2005 until September 2016—for a total of approximately 35,000 patients—and includes subjects with normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and dementia. Subjects may enroll in an ADC, and therefore UDS, via clinician referral, self-referral, referral by family members, or active recruitment through community organizations. Volunteers who wish to contribute to research on dementia may also enroll. Data for the UDS are collected and recorded directly by trained clinicians and contain, among other measures, information on (1) patient demographics, medical history (including medication use), and family history; (2) cognitive and functional status, measured using validated instruments such as the MMSE, CDR, and the FAQ; and (3) behavioral symptoms, evaluated using the NPI-Questionnaire. Importantly, at each visit the NACC data include a derived indicator of whether a clinician has observed meaningful decline in a patient's memory, nonmemory cognitive abilities, behavior, ability to manage his/her affairs, or motor/movement changes relative to previously attained abilities. In the context of the present study, it is assumed that the clinician's assessment of a meaningful change is relative to the visit immediately preceding the time of evaluation. This indicator serves as the relevant index for our anchor-based MCID estimates.

2.2. Study sample and time periods

Patients were included in the study if they had at least two consecutive visits to an ADC during the period 9/2005-9/2016 (n = 22,039) and had complete information for clinician assessment of meaningful decline in cognition, function, and/or behavioral attributes, as well as the MMSE, CDR, and FAQ scores (n = 19,566). Patients were then stratified into four mutually exclusive cohorts:

-

1.

Normal cognition (n = 8404)—patients not classified as MCI-AD, mild AD dementia, or moderate-severe AD dementia, as described below, but with ≥1 visit with an MMSE score >26 and no evidence of a probable AD diagnosis (prAD; per National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke - Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria) [14] at the same visit as MMSE score >26.

-

2.

MCI-AD (n = 2815)—patients with ≥1 visit with clinician diagnosis of MCI with a presumptive etiology of AD (per National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke - Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria) on or after the first visit with MCI diagnosis, and stable or progressive disease (i.e., no subsequent visit with “normal cognition” as per the clinician's assessment). To minimize the likelihood of including patients with MCI because of other etiologies, patients with any record of non-AD etiology were excluded.

-

3.

Mild AD dementia (n = 3163)—patients not classified as MCI-AD but with ≥1 visit with a diagnosis of prAD and MMSE score 20-26, no indication of MMSE score <17 before earliest indication of mild AD dementia (to minimize the likelihood of including patients with considerably greater disease severity during previous visits), and stable or progressive disease (i.e., no subsequent visit with MCI or normal cognition in clinician's assessment).

-

4.

Moderate-to-severe AD dementia (n = 1509)—patients not classified as MCI-AD or mild AD dementia, but with ≥1 visit with a diagnosis of prAD and MMSE score <20, with stable or progressive disease (as defined previously for the mild AD dementia cohort).

Because patients with AD often experience progression in their disease, it is possible that patients could meet criteria for multiple cohorts over time. However, to approximate the potential enrollment criteria for clinical trials, patients with AD were classified according to the earliest observed stage of disease in the following order: MCI-AD, mild AD dementia, and moderate-severe AD dementia. The remaining 3675 patients did not meet the criteria for any cohort and were excluded from analyses stratified by disease severity.

2.3. Patient characteristics, outcomes, and analytical approach

The following characteristics were assessed for the final analytic sample at the time of first observed ADC visit:

-

•

Demographic characteristics—mean age, gender distribution, average years of education,

-

•

Select comorbidities—proportions of patients with diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, cardiovascular conditions, cerebrovascular disease, depression,

-

•

Clinical characteristics—a clinician-determined cognitive status (MCI, dementia, normal cognition); global CDR score (mean and categorical score, mean CDR-SB score, and mean MMSE score); self-reported (or informant-reported) level of independence (i.e., whether patient is independent, requires help with complex activities, basic activities, or is completely dependent); mean FAQ score; and mean NPI-Q score.

Patient characteristics were described for the overall cohort, as well as stratified by whether the patients had ≥1 visit where the clinician indicated a meaningful decline. Statistical significance of differences between cohorts was assessed using chi-square tests for categorical measures and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous measures.

With regards to the key outcomes, mean changes in CDR-SB, MMSE, and FAQ across consecutive visits (estimated as second visit minus the first visit) were estimated for the overall cohort, as well as the four subsets described earlier, stratified by whether the clinician indicated there was a meaningful decline from the previous visit. The 95% confidence intervals around the mean changes were also reported.

In addition to these anchor-based estimates of MCID, the following distribution-based measures of MCID were estimated [6], [15] and integrated according to previously published guidance on applying triangulation methodology to derive MCID [12].

-

•

Effect size (ES)—defined as mean difference in score divided by standard deviation (SD) of baseline scores.

-

•

Standardized Response Mean (SRM)—defined as mean difference in score divided by SD of the change from previous visit score.

-

•

0.5*SD of baseline scores.

2.4. Sensitivity analyses

The clinician's assessment of clinically meaningful decline considers changes in ≥1 of the following domains: cognitive, functional, and behavioral. As recent guidance for future clinical trials in AD allows for the possibility of primary endpoints based on changes in the cognitive domain alone, particularly in the earlier stages of disease [16], MCID estimates for all clinical outcomes were also generated for a subgroup of patients experiencing a meaningful decline in the cognitive domain only. For this analysis, visits where the clinician indicated meaningful decline in functional or behavioral domains were excluded.

In another sensitivity analysis aimed at testing whether the findings were sensitive to the selection of the anchor to determine MCID estimates, similar measures as the core analyses were generated for MMSE and FAQ, stratified by whether patients experienced no change in global CDR or experienced a change of 0.5 points (from 0.5 to 1) between consecutive visits [15].

All outcomes were evaluated at the visit level; all analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

On average, patients in the overall study sample were evaluated approximately every year (mean ± SD: 1.15 ± 0.38 years; median [interquartile range]: 1.04 years [0.98, 1.18]). The mean age of the overall study sample (n = 19,566) was 73 years, 43% were men, and patients had just over 15 years of education. Of the overall study sample, 6896 (35%) patients did not have any visit with a clinician-indicated meaningful decline in cognitive, functional, or behavioral attributes (Table 1). On average, patients with no clinically meaningful decline ever were younger at their first ADC visit (71 vs. 74 years) and were less likely to be men (33% vs. 49%). Approximately 24% of patients with no meaningful decline had depression at the first ADC visit compared with 42% of those with meaningful decline. In addition, 93% of those with no meaningful decline were considered by physicians to have normal cognition (MMSE score 28.97, global CDR score 0.03; 94% with global CDR score 0), and only 0.7% used an AD medication. Relatedly, 98% were able to live independently. By comparison, among those with meaningful decline, nearly half were already diagnosed with dementia at the time of first presentation, 32% with MCI, and 6% with other cognitive impairment; 41% used AD medication, and only 53% were able to live independently. The mean MMSE score for the cohort with meaningful decline was 24.61, the mean global CDR was 0.67 (54% had a score of 0.5 and 24%, a score of 1), and the mean FAQ score was 8.36 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics at the time of first ADC visit

| Characteristic | All patients (N = 19,566) | Meaningful decline (N = 12,670) | No meaningful decline (N = 6896) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at index visit (years), mean (SD) | 73.05 (9.83) | 73.98 (9.66) | 71.33 (9.89)∗ |

| Male, n (%) | 8479 (43.3) | 6203 (49.0) | 2276 (33.0)∗ |

| Education (years), mean (SD) | 15.1 (3.4) | 14.8 (3.6) | 15.7 (3.0)∗ |

| Comorbid conditions, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 10,394 (53.1) | 6921 (54.6) | 3473 (50.4)∗ |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 10,025 (51.8) | 6672 (53.2) | 3353 (49.1)∗ |

| Depression | 6876 (35.2) | 5253 (41.6) | 1623 (23.6)∗ |

| Diabetes | 2415 (12.4) | 1678 (13.3) | 737 (10.7)∗ |

| Transient ischemic attack | 972 (5.0) | 733 (5.8) | 239 (3.5)∗ |

| Stroke | 955 (4.9) | 793 (6.3) | 162 (2.3)∗ |

| Clinician diagnosis of cognitive status, n (%) | |||

| Normal cognition | 8277 (42.3) | 1900 (15.0) | 6377 (92.5)∗ |

| Impaired, no MCI | 937 (4.8) | 735 (5.8) | 202 (2.9)∗ |

| MCI | 4301 (22.0) | 3987 (31.5) | 314 (4.6)∗ |

| Dementia | 6051 (30.9) | 6048 (47.7) | 3 (0.0)∗ |

| Level of independence, n (%) | |||

| Able to live independently | 13,454 (69.0) | 6687 (53.0) | 6767 (98.2)∗ |

| Requires assistance with complex activities | 4354 (22.3) | 4255 (33.7) | 99 (1.4)∗ |

| Requires assistance with basic activities | 1390 (7.1) | 1368 (10.8) | 22 (0.3)∗ |

| Completely dependent | 314 (1.6) | 311 (2.5) | 3 (0.0)∗ |

| Clinical outcome assessment scores | |||

| Global CDR, mean (SD) | 0.44 (0.53) | 0.67 (0.53) | 0.03 (0.12)∗ |

| Global CDR categories, n (%) | |||

| 0.0 | 8343 (42.6) | 1837 (14.5) | 6506 (94.3)∗ |

| 0.5 | 7286 (37.2) | 6897 (54.4) | 389 (5.6)∗ |

| 1.0 | 3052 (15.6) | 3051 (24.1) | 1 (0.0)∗ |

| 2.0 | 700 (3.6) | 700 (5.5) | 0 (0.0)∗ |

| 3.0 | 185 (1.0) | 185 (1.5) | 0 (0.0)∗ |

| CDR-SB, mean (SD) | 2.13 (3.12) | 3.25 (3.38) | 0.06 (0.23)∗ |

| MMSE, mean (SD) | 26.14 (4.84) | 24.61 (5.34) | 28.97 (1.35)∗ |

| FAQ score, mean (SD) | 5.49 (8.10) | 8.36 (8.79) | 0.23 (1.06)∗ |

| NPI-Q score, mean (SD) | 2.54 (3.78) | 3.58 (4.22) | 0.63 (1.51)∗ |

| AD medication use, n (%) | 5227 (26.7) | 5178 (40.9) | 49 (0.7)∗ |

-

1.Index visit defined as the first ADC visit.

-

2.Clinically meaningful decline indicates clinician's assessment of meaningful decline in a patient's memory, nonmemory cognitive abilities, behavior, ability to manage his/her affairs, or motor/movement changes since the previous visit. Patients with at least one visit with clinician-indicated meaningful decline were included in the “meaningful decline” cohort.

Abbreviations: ADC, Alzheimer's Disease Center; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; FAQ, Functional Assessment Questionnaire; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; NPI-Q, Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire; SB, sum of boxes; SD, standard deviation.

P value <.0001; P values were calculated using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables.

All comparisons between the meaningful decline cohort and the no meaningful decline cohort were statistically significant (P < .0001).

3.2. Changes in clinical outcomes and MCID measures—overall and by disease severity

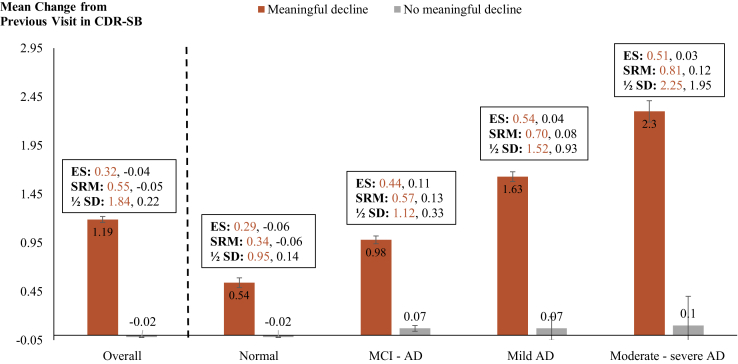

Overall, across all visits, the mean changes in CDR-SB scores for visits with and without clinician-indicated meaningful decline were 1.19 (ES: 0.32; SRM: 0.55) and −0.02 (ES: −0.04; SRM: −0.05), respectively (Fig. 1). Similarly, mean changes in MMSE scores for visits with and without clinician-indicated meaningful decline were −1.64 (ES: −0.29; SRM: −0.47) and -0.04 (ES: −0.02; SRM: −0.02), respectively. Regarding functional attributes, the mean changes in FAQ among visits with and without clinically meaningful decline were 2.49 (ES: 0.26; SRM: 0.47) and 0.03 (ES: 0.02; SRM: 0.02), respectively (Table 2). The minimum change thresholds at which over 70% of visits were classified as having a clinically meaningful decline were as follows: an increase of 0.5 in CDR-SB, a decrease of ≥3 points on the MMSE, and an increase of ≥1 point on the FAQ (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

MCID for CDR-SB—Overall and by Disease Severity. Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; CDR-SB, Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes; ES, effect size; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; SRM, standardized response mean; SD, standard deviation (of baseline scores). Note. Clinically meaningful decline indicates clinician's assessment of meaningful decline in a patient's memory, nonmemory cognitive abilities, behavior, ability to manage his/her affairs, or motor/movement changes since the previous visit.

Table 2.

Changes in clinical outcome scores that indicate clinically important difference, overall and by disease severity (n = 57,097 pairs of visits)

| Clinical outcome | Overall |

Normal |

MCI-AD |

Mild AD dementia |

Moderate-severe AD dementia |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meaningful decline (N = 28,274) | No meaningful decline (N = 28,823) | Meaningful decline (N = 4347) | No meaningful decline (N = 22,023) | Meaningful decline (N = 6897) | No meaningful decline (N = 1540) | Meaningful decline (N = 7961) | No meaningful decline (N = 244) | Meaningful decline (N = 2702) | No meaningful decline (N = 30) | |

| MMSE | ||||||||||

| Mean change (95% CI) | −1.64 (−1.68; −1.60) | −0.04 (−0.05; −0.02) | −0.89 (−0.97; −0.81) | −0.05 (−0.06; −0.03) | −1.26 (−1.33; −1.20) | −0.19 (−0.27; −0.11) | −2.32 (−2.41; −2.24) | −0.40 (−0.63; −0.16) | −3.22 (−3.37; −3.06) | −0.47 (−1.29; 0.36) |

| ES | −0.29 | −0.02 | −0.42 | −0.05 | −0.37 | −0.11 | −0.55 | −0.18 | −0.53 | −0.09 |

| SRM | −0.47 | −0.02 | −0.34 | −0.04 | −0.43 | −0.11 | −0.62 | −0.22 | −0.77 | −0.21 |

| ½ SD(baseline) | 2.82 | 0.74 | 1.05 | 0.47 | 1.71 | 0.89 | 2.13 | 1.13 | 3.05 | 2.69 |

| FAQ | ||||||||||

| Mean change (95% CI) | 2.49 (2.43; 2.55) | 0.03 (0.01; 0.05) | 1.42 (1.28; 1.55) | 0.02 (0.00; 0.04) | 2.59 (2.47; 2.71) | 0.26 (0.15; 0.37) | 3.39 (3.26; 3.51) | 0.66 (0.30; 1.02) | 3.22 (2.99; 3.44) | 0.70 (−0.67; 2.07) |

| ES | 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.36 | 0.10 | 0.41 | 0.14 | 0.38 | 0.09 |

| SRM | 0.47 | 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.02 | 0.51 | 0.12 | 0.62 | 0.23 | 0.53 | 0.19 |

| ½ SD(baseline) | 4.71 | 0.81 | 3.18 | 0.61 | 3.63 | 1.30 | 4.13 | 2.30 | 4.21 | 3.94 |

-

1.Clinically meaningful decline indicates clinician's assessment of meaningful decline in a patient's memory, nonmemory cognitive abilities, behavior, ability to manage his/her affairs, or motor/movement changes since the previous visit.

-

2.Effect size was calculated at the visit level as the mean difference in score divided by SD(baseline).

-

3.SRM was calculated at the visit level as the mean difference in score divided by SD of the change from previous visit score.

-

4.1/2 SD(baseline) was calculated at the visit level as 0.5 x SD(baseline).

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size; FAQ, Functional Assessment Questionnaire; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; SRM, standardized response mean; SD, standard deviation.

Table 3.

Smallest change estimates for majority of visits with clinician-indicated meaningful decline (overall; n = 57,097 pairs of visits)

| Clinical outcome | Cutoff for ≥50% visits with meaningful decline | Cutoff for ≥60% visits with meaningful decline | Cutoff for ≥70% visits with meaningful decline | Cutoff for ≥80% visits with meaningful decline | Cutoff for ≥90% visits with meaningful decline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDR-SB | +0.5 | +0.5 | +0.5 | +1 | +1 |

| MMSE | −2 | −2 | −3 | −4 | −5 |

| FAQ | +1 | +1 | +1 | +2 | +4 |

-

1.+ indicates an increase in score from previous visit; − indicates a decrease in score from previous visit.

-

2.Clinically meaningful decline indicates clinician's assessment of meaningful decline in a patient's memory, nonmemory cognitive abilities, behavior, ability to manage his/her affairs, or motor/movement changes since the previous visit.

Abbreviations: CDR-SB, Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes; FAQ, Functional Assessment Questionnaire; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.

When evaluated by disease severity, the proportions of visits with clinically meaningful decline increased with increase in disease severity: 16% of visits in the “normal” cohort had clinically meaningful decline compared with 82% of visits in the MCI-AD cohort, 97% in the mild AD dementia cohort, and 99% visits in the moderate-severe AD dementia cohort (Supplementary Fig. 1). In addition, on average, the magnitude of changes in CDR-SB, MMSE, and FAQ associated with clinician assessment of meaningful decline increased with increase in disease severity (Fig. 1 and Table 2). For example, among those with a clinically meaningful decline, the mean change in CDR-SB scores was 0.54 for patients with normal cognition (ES: 0.29; SRM: 0.34), 0.98 among those with MCI-AD (ES: 0.44; SRM: 0.57), 1.63 for those with mild AD (ES: 0.54; SRM: 0.70), and 2.30 for the moderate-severe AD cohort (ES: 0.51; SRM: 0.81). The changes in CDR-SB scores for visits with no meaningful decline also increased—from -0.02 in the normal cohort to 0.10 in the moderate-severe AD cohort—however, the effect sizes were not meaningful (ES: −0.06 and 0.03, respectively) (Fig. 1).

Results from the distribution-based method are consistent with the anchor-based approach, with similar ½ SD values for CDR-SB, and slightly larger but comparable values for MMSE and FAQ (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

3.3. MCID estimates among visits with no changes in behavior and/or motor function

Compared with the core analysis including all visits, the magnitudes of changes at which majority (≥70%) of the visits were categorized as having meaningful decline were higher for the subgroup with decline in the cognitive domain only–CDR-SB: increase of ≥1, MMSE: decrease of ≥6, and FAQ: increase of ≥5 points (data not shown). On average, the mean changes in CDR-SB, MMSE, and FAQ across visits with meaningful decline were smaller than the core analysis; however, the ES/SRM values were similar. For example, the mean change in CDR-SB for visits with meaningful decline was 0.74 (ES: 0.31; SRM: 0.47) compared with a change of 1.19 (ES: 0.32; SRM: 0.55) in the main analysis (Table 4). The mean changes for visits with clinician-indicated no meaningful decline were very small in both analyses—for example, −0.02 for the main analysis and 0.00 for the sensitivity (ES and SRM were −0.04 and −0.05 for the core analysis and 0.00 for the sensitivity).

Table 4.

Changes in clinical outcome scores that indicate clinically important difference, among visits with or without meaningful decline in cognitive domain only (n = 33,851 pairs of visits)

| Clinical outcome | Meaningful decline (N = 5675) | No meaningful decline (N = 28,176) |

|---|---|---|

| CDR sum of boxes | ||

| Mean change (95% CI) | 0.74 (0.70; 0.78) | 0.00 (0.00; 0.00) |

| ES | 0.31 | 0.00 |

| SRM | 0.47 | 0.00 |

| ½ SD(baseline) | 1.19 | 0.16 |

| MMSE | ||

| Mean change (95% CI) | −1.02 (−1.09; −0.94) | −0.04 (−0.06; −0.02) |

| ES | −0.26 | −0.03 |

| SRM | −0.36 | −0.03 |

| ½ SD(baseline) | 1.99 | 0.72 |

| FAQ | ||

| Mean change (95% CI) | 1.89 (1.77; 2.01) | 0.06 (0.04; 0.07) |

| ES | 0.27 | 0.04 |

| SRM | 0.40 | 0.04 |

| ½ SD(baseline) | 3.44 | 0.69 |

-

1.Clinically meaningful decline indicates clinician's assessment of meaningful decline in a patient's memory or non-memory cognitive abilities since the previous visit.

-

2.Effect size was calculated at the visit level as the mean difference in score divided by SD(baseline).

-

3.SRM was calculated at the visit level as the mean difference in score divided by SD of the change from previous visit score.

-

4.1/2 SD(baseline) was calculated at the visit level as 0.5 x SD(baseline).

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size; FAQ, Functional Assessment Questionnaire; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; SRM, standardized response mean; SD, standard deviation.

3.4. MCID estimates, by changes in global CDR scores

Overall, the ES/SRM of MMSE and FAQ among visits with changes in global CDR score from 0.5 to 1 were in the acceptable ranges for MCID [17], whereas the ES/SRM in those with no change in global CDR scores were not meaningful (Table 5). Specifically, the mean change in MMSE for visits with a change in CDR score was –2.58 (ES: −0.73; SRM: −0.72) compared with a change in MMSE of −0.46 (ES: −0.10; SRM: −0.21) for those with no change in CDR scores. The mean change in FAQ for visits with a change in CDR score was 6.25 (ES: 1.01; SRM: 0.97) compared with a change in FAQ of 0.72 (ES: 0.10; SRM: 0.22) for those with no change in CDR scores. When evaluated for cognitive status, on average, the changes in MMSE and FAQ scores for visits among patients with MCI or mild AD were similar to the overall cohort (Table 5).

Table 5.

Changes in clinical outcome scores that indicate clinically important difference, by disease severity, and change in global CDR (n = 48,254 pairs of visits)

| Clinical outcome | Overall |

Normal |

MCI-AD |

Mild AD dementia |

Moderate-severe AD dementia |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change from 0.5 to 1 (N = 2924) | No change (N = 45,330) | Change from 0.5 to 1 (N = 220) | No change (N = 23,622) | Change from 0.5 to 1 (N = 918) | No change (N = 6420) | Change from 0.5 to 1 (N = 1171) | No change (N = 5118) | Change from 0.5 to 1 (N = 139) | No change (N = 1542) | |

| MMSE | ||||||||||

| Mean change (95% CI) | −2.58 (−2.71; −2.45) | −0.46 (−0.48; −0.44) | −2.79 (−3.24; −2.33) | −0.11 (−0.13; −0.10) | −2.55 (−2.76; −2.34) | −0.72 (−0.78; −0.66) | −2.36 (−2.55; −2.16) | −1.63 (−1.72; −1.54) | −4.99 (−5.77; −4.22) | −2.15 (−2.33; −1.98) |

| ES | −0.73 | −0.10 | −0.97 | −0.10 | −0.86 | −0.23 | −0.80 | −0.38 | −1.12 | −0.33 |

| SRM | −0.72 | −0.21 | −0.81 | −0.09 | −0.80 | −0.29 | −0.69 | −0.51 | −1.08 | −0.60 |

| ½ SD(baseline) | 1.76 | 2.19 | 1.44 | 0.56 | 1.48 | 1.54 | 1.48 | 2.12 | 2.23 | 3.30 |

| FAQ | ||||||||||

| Mean change (95% CI) | 6.25 (6.02; 6.49) | 0.72 (0.69; 0.75) | 6.32 (5.38; 7.26) | 0.14 (0.12; 0.16) | 6.92 (6.50; 7.34) | 1.42 (1.32; 1.51) | 5.68 (5.34; 6.01) | 2.44 (2.30; 2.57) | 8.42 (7.12; 9.71) | 2.08 (1.81; 2.35) |

| ES | 1.01 | 0.10 | 0.94 | 0.05 | 1.14 | 0.22 | 0.98 | 0.29 | 1.36 | 0.24 |

| SRM | 0.97 | 0.22 | 0.89 | 0.08 | 1.06 | 0.36 | 0.98 | 0.50 | 1.09 | 0.38 |

| ½ SD(baseline) | 3.08 | 3.78 | 3.35 | 1.37 | 3.04 | 3.24 | 2.89 | 4.25 | 3.09 | 4.41 |

-

1.Effect size was calculated at the visit level as the mean difference in score divided by SD(baseline).

-

2.SRM was calculated at the visit level as the mean difference in score divided by SD of the change from previous visit score.

-

3.1/2 SD(baseline) was calculated at the visit level as 0.5 x SD(baseline).

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size; FAQ, Functional Assessment Questionnaire; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; SRM, standardized response mean; SD, standard deviation.

4. Discussion

Validated definitions of MCID for clinical measures used in AD research remain underexplored in the literature [1], [4], [5]. In addition, previous approaches to define MCIDs have focused on patients at more advanced stages of the disease or focused on a narrow subset of clinical outcome assessments [5]. Although the clinical outcome assessments included in the NACC UDS may not be uniformly consistent with those included in contemporary clinical trials, this study provides estimates of clinically meaningful changes for several relevant domains across the AD spectrum, including the earlier stages of MCI-AD and mild AD–the primary focus of most current therapeutic trials.

Across the overall cohort of NACC participants with cognitive abilities ranging from normal to moderate-severe AD dementia, on average, a 1-2 point increase in CDR-SB, a 1-3 point decrease in MMSE, and 3–5 point increase in FAQ were indicative of a meaningful decline in the clinician's assessment. The ES/SRM for those with a clinically meaningful decline were in the acceptable ranges for MCID (ES: 0.2–0.5; SRM: 0.4–0.8), whereas the ES/SRM for changes in visits with no meaningful decline indicator were close to zero. Estimates generated from the distribution-based approach (1/2 SD at baseline), as well as using a change in global CDR (as a different anchor), were supportive of the estimates generated using the clinician's assessment as an anchor for MMSE (∼1-3 point decrease on average), and somewhat larger—but comparable—for FAQ (∼5-7 point increase on average). Among the subset of patients with decline in cognitive domain only, the MCID estimates for CDR-SB, MMSE, and FAQ across visits with meaningful decline were smaller than the core analysis, however, the ES/SRM were similar. MCID for CDR-SB and FAQ have not been estimated previously [5]. However, our estimates of MCID for MMSE are consistent with the published range of MCID estimates for this outcome measure (a decrease of 1.4-4 points) [9], [10].

In stratifying the findings by disease severity, not surprisingly, we found that the proportions of visits characterized as having a clinically meaningful decline (in clinician's opinion) increased from 16% among the normal cognition cohort to 99% among those with moderate-severe AD dementia. In addition, the magnitudes of MCID estimates increased by stage of severity across the disease continuum. For example, among visits with clinically meaningful decline, the mean change in MMSE scores over consecutive visits for the normal cohort was −0.89 compared with −3.22 for the moderate-severe AD dementia cohort. Furthermore, the ESs and SRM among visits with meaningful decline were consistently within the acceptable ranges for MCID, but <0.1 for those with no meaningful decline. These findings are consistent with previous reports that an increase in disease severity may be associated with a faster deterioration in cognitive and functional attributes [18], [19] and underscore the need to calibrate the MCID measures according to the disease severity of the patient population being studied. In addition, our findings suggest that the thresholds of change in global, cognitive, and functional domains that are associated with a clinician's impression of meaningful decline in MCI-AD and mild AD dementia are lower than the conventionally accepted thresholds. These results are consistent with a recent study that used a similar anchor-based methodology and estimated that the MCID for ADAS-Cog in mild AD was lower (3 points) compared to previous recommendations made by a consensus committee of the FDA for patients in more advanced stages (≥4 points) [15]. Future research should evaluate whether these estimates are corroborated by the responder status observed in contemporary clinical trials.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

This study utilized data from a large cohort of patients who repeatedly visit various ADCs across the US on an annual basis (on average), and therefore the findings are not limited to a particular trial population. However, the population enrolled in the NACC UDS may not be representative of the broader population with cognitive impairment because of differences in patient characteristics and enrollment procedures [13]. In particular, patients enrolled in the NACC UDS are more educated than the general US population. In addition, each ADC enrolls the subjects according to its own protocol, and patients may enroll for reasons other than seeking treatment (e.g., to participate in clinical trials). Relatedly, to assess the changes in various clinical endpoints over time, the study was limited to patients with at least two consecutive visits to the ADCs, further limiting the representativeness of the sample. Furthermore, while the data facilitate evaluation of changes in patients' clinical attributes across the AD spectrum, the precise dates of cognitive impairment diagnoses and changes in disease severity are not captured within the data. In addition, although the clinical criteria for determining MCI due to AD were updated in 2011 [14], these changes were not implemented within the NACC until March 2015 [13]. As such, the cohorts evaluated in this study may not reflect the current clinical practice. In addition, we assumed that the clinician's assessment of a meaningful decline at a given visit was relative to the assessment at the previous visit, but the precise considerations, including the use of any validated tool for the clinical decision making within and across ADCs remain unknown. Finally, it should be noted that the MCID estimates present average changes within the sample cohort and might not be appropriate for interpretation of individual level findings. Of note, the present findings may represent conservative estimates, given that an unknown proportion of the sample deemed to have meaningful decline may have achieved a clinically important decline at a precise date before the annual follow-up assessment, thereby surpassing the MCID between visit periods. In other words, the MCID estimates from the present study may reflect change thresholds that are higher than the true MCID. Moreover, the MCIDs reported in this study correspond to the clinicians' assessments of a meaningful decline as opposed to the patients' perceptions. Nonetheless, the study findings present average effects based on the clinical judgment of multiple treating physicians across ADCs. As such, the study findings offer the potential to inform design of future clinical trials based on actual clinical practice.

5. Conclusions

Using clinicians' assessment of meaningful decline in patients' cognitive, functional, or behavioral attributes since the previous visit as an anchor, a 1-2 point increase (on average) in CDR-SB, a 1-3 point decrease in MMSE, and a 3-5 point increase in FAQ over 1 year are considered clinically meaningful. Across the disease severity spectrum, the thresholds for clinically meaningful decline increased from MCI-AD to moderate-severe AD. Specifically, the MCID estimates for CDR-SB, MMSE, and FAQ were as follows: MCI-AD: +1, −1, and +3; mild AD: +2, −2, and +3; moderate-severe AD: +2, −3, and +3, respectively (where '+' indicates an increase in score and '−' indicates a decrease in score). The MCID estimates based only on the distribution of scores at baseline were slightly larger but generally consistent with and supportive of the anchor-based approach. These findings suggest that it is important to calibrate the MCID measures to be used in clinical trials according to disease severity of the patient population.

Research in context.

-

1.

Systematic review: Information about whether an intervention for Alzheimer's disease (AD) can provide meaningful clinical benefits relative to comparators is important for evaluating clinical trials and is of great value to patients, caregivers, and healthcare decision makers. However, empirical evidence regarding the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) estimates across various clinical outcome assessments among people with different stages of AD is limited.

-

2.

Interpretation: We find that on average, 1-2 point increase in CDR-SB, a 1-3 point decrease in MMSE, and 3-5 point increase in FAQ over 1 year were indicative of a meaningful decline in clinicians' assessment. The MCID values generally increased with increase in disease severity, suggesting that it is important to calibrate MCID measures to be used in clinical trials according to disease severity of the population.

-

3.

Future directions: Future research should evaluate whether these estimates are corroborated by the outcomes observed in contemporary clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

No assistance in the preparation of this manuscript is to be declared. Preliminary findings from this analysis were presented at the 2018 Alzheimer's Association International Conference in Chicago, IL.

The NACC database is funded by NIA/ NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Thomas Wisniewski, MD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI James Brewer, MD, PhD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG053760 (PI Henry Paulson, MD, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P30 AG049638 (PI Suzanne Craft, PhD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Grabowski, MD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD).

Footnotes

Funding for this research was provided by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, Indiana, the employer of J. Scott Andrews and Brandy R. Matthews. Urvi Desai, Noam Y. Kirson, and Miriam L. Zichlin are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a company that received funding from Eli Lilly and Company to conduct this study. Daniel E. Ball was an employee of Eli Lilly and Company at the time of the study and owns company stock.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trci.2019.06.005.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Molnar F.J., Man-Son-Hing M., Fergusson D. Systematic review of measures of clinical significance employed in randomized clinical trials for drugs for dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:536–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King M.T. A point of minimal important difference (MID): a critique of terminology and methods. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11:171–184. doi: 10.1586/erp.11.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaeschke R., Singer J., Guyatt G.H. Measurement of health status: ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Controlled Clin Trials. 1989;10:407–415. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green Park Collaborative, Evidence guidance document: design of clinical studies of pharmacologic therapies for Alzheimer's disease, Center for Medical Technology Policy. 2013. Available at: http://www.cmtpnet.org/docs/resources/GPC_Evidence_Guidance_Document_-_Alzheimers_Disease.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2018.

- 5.Webster L., Groskreutz D., Grinbergs-Saull A., Howard R., O'Brien J.T., Mountain G. Core outcome measures for interventions to prevent or slow the progress of dementia for people living with mild to moderate dementia: systematic review and consensus recommendations. 2017. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0179521 2017. Available at: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Wright A., Hannon J., Hegedus E.J., Kavchak A.E. Clinimetrics corner: a closer look at the minimal clinically important difference (MCID), 2012 minimal clinically important difference (MCID) J Man Manipulative Ther. 2012;20:160–166. doi: 10.1179/2042618612Y.0000000001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Copay A.G., Subach B.R., Glassman S.D., Polly D.W., Schuler T.C. Understanding the minimum clinically important difference: a review of concepts and methods. Spine J. 2007;7:541–546. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guatt G.H., Osoba D., Wu A.W., Wyrwich K.W., Norman G.R. Methods for explaining the clinical significance of health status measures. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:371–383. doi: 10.4065/77.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burback D., Molnar F.J., St John P., Man-Son-Hing M. Key methodological features of randomized controlled trials of Alzheimer's disease therapy. Minimal clinically important difference, sample size and trial duration. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;10:534–540. doi: 10.1159/000017201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howard R., Phillips P., Johnson T., O'Brien J., Sheehan B., Lindesay J. Determining the minimum clinically important differences for outcomes in the DOMINO trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:812–817. doi: 10.1002/gps.2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vellas B., Andrieu S., Sampaio C., Coley N., Wilcock G., European Task Force Group Endpoints for trials in Alzheimer’s disease: a European task force consensus. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:436–450. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leidy N.K., Wyrwich K.W. Bridging the gap: using triangulation methodology to estimate minimal clinically important differences (MCIDs) COPD. 2005;2:157–165. doi: 10.1081/copd-200050508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Information and Resources NACC researcher home page, National Alzheimers Coordinating Center. University of Washington. Available at: https://www.alz.washington.edu/WEB/researcher_home.html.

- 14.McKhann G., Drachman D., Folstin M., Katzman R., Price D., Stadlan E.M. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schrag A., Schott J.M., Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative What is the clinically relevant change on the ADAS-Cog? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:171–173. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-300881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Posner H., Curiel R., Edgar C., Hendrix S., Liu E., Loewenstein D.A. Outcomes assessment in clinical trials of Alzheimer's disease and its precursors: readying for short-term and long-term clinical trial needs. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2017;14:22–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yost K.J., Cella D., Chawla A., Holmgren E., Eton D.T., Ayanian J.Z. Minimally important differences were estimated for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (FACT-C) instrument using a combination of distribution- and anchor-based approaches. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:1241–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrews J.S., Desai U., Kirson N.Y., Enloe C.J., Ristovska L., King S. Functional limitations and healthcare resource utilization for individuals with cognitive impairment without dementia: findings from a US population-based survey. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2017;6:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zidan M., Arcoverde C., Bom de Araujo N., Vasques P., Rios A., Laks J. Motor and functional changes in different stages of Alzheimer's disease. Rev Psiq Clín. 2012;39:161–165. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.