SUMMARY

Excitation-inhibition (E-I) imbalance is considered a hallmark of various neurodevelopmental disorders, including schizophrenia and autism. How genetic risk factors disrupt coordinated glutamatergic and GABAergic synapse formation to cause an E-I imbalance is not well understood. Here, we show that knockdown of Disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1 (DISC1), a risk gene for major mental disorders, leads to E-I imbalance in mature dentate granule neurons. We found that excessive GABAergic inputs from parvalbumin-, but not somatostatin-, expressing interneurons enhance the formation of both glutamatergic and GABAergic synapses in immature mutant neurons. Following the switch in GABAergic signaling polarity from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing during neuronal maturation, heightened inhibition from excessive parvalbumin+ GABAergic inputs causes loss of excitatory glutamatergic synapses in mature mutant neurons, resulting in an E-I imbalance. Our findings provide insights into the developmental role of depolarizing GABA in establishing E-I balance and how it can be influenced by genetic risk factors for mental disorders.

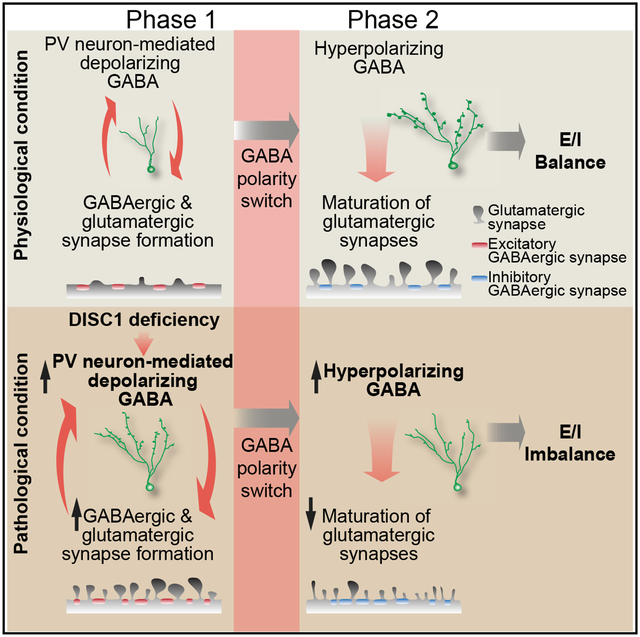

Graphical Abstract

In Brief

Kang et al. uncover a circuit-level homeostatic mechanism coordinating glutamatergic and GABAergic synapse formation during neuronal maturation and reveal how excitation-inhibition imbalance develops due to a genetic insult.

INTRODUCTION

Excitation-inhibition (E-I) balance, a defining property of neuronal network activity in the healthy brain, is initially established during development and actively maintained by homeostatic mechanisms throughout life (Gao and Penzes, 2015; Turrigiano and Nelson, 2004). Cumulative evidence suggests that an E-I imbalance contributes to the etiology and symptomology of a range of brain disorders with developmental origins, including schizophrenia, autistic spectrum disorders (ASDs), and epilepsy (Canitano and Pallagrosi, 2017; Foss-Feig et al., 2017; Gao and Penzes, 2015; Nelson and Valakh, 2015). For example, genetic linkage and association studies have identified many disease risk genes implicated in synaptic structure and functions (Canitano and Pallagrosi, 2017). Postmortem studies have also provided evidence of structural abnormalities in both excitatory glutamatergic and inhibitory GABAergic synapses in patients with mental disorders (Chattopadhyaya and Cristo, 2012; Glausier and Lewis, 2013; Hutsler and Zhang, 2010). Moreover, recent multimodal neuroimaging studies of schizophrenia and ASD patients implicates E-I imbalance in the expression of some disease symptoms (Foss-Feig et al., 2017). In mice, acute alterations of E-I balance can elicit changes in social and cognitive behavior (Yizhar et al., 2011).

E-I imbalance may arise from dysregulation of the formation or maturation of either excitatory glutamatergic synapses or inhibitory GABAergic synapses (Canitano and Pallagrosi, 2017). While most of the previous studies investigated the roles of disease risk genes on the maintenance of E-I balance, developmental processes that establish E-I balance at the circuitry level are far from clear. In particular, GABA, a classic inhibitory neurotransmitter for mature neurons, depolarizes immature neurons due to their high levels of intracellular chloride due to the expression of chloride transporter Nkcc1 (Ben-Ari, 2002; Ben-Ari and Spit-zer, 2004; Owens and Kriegstein, 2002). Given the developmental switch in GABA action from depolarizing immature neurons to hyperpolarizing mature neurons and the presence of various GABAergic interneuron subtypes, understanding developmental processes and circuitry mechanisms that coordinate excitatory and inhibitory synapse formation may provide fundamental insights into the pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental disorders and novel therapeutic strategies.

Disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1 (DISC1), a genetic risk factor for major mental disorders, regulates various aspects of neural development, including cell proliferation, migration, dendritic development, and neuronal morphogenesis (Brandon and Sawa, 2011; Chubb et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2012; Mao et al., 2009; Saito et al., 2016; Thomson et al., 2013; Ye et al., 2017), as well as synapse formation (Duan et al., 2007; Faulkner et al., 2008; Hayashi-Takagi et al., 2010; Seshadri et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2011). DISC1 knockdown in adult-born dentate granule neurons is also sufficient to cause affective and cognitive behavioral deficits in mice (Zhou et al., 2013), suggesting dysfunction in neuronal circuits. Taking advantage of DISC1-induced deficits as a model of neurodevelopmental dysregulation, we investigated molecular, cellular, and circuitry mechanisms leading to E-I imbalance in vivo.

RESULTS

DISC1 Deficiency Leads to E-I Imbalance of Adult-Born Mature Dentate Granule Neurons

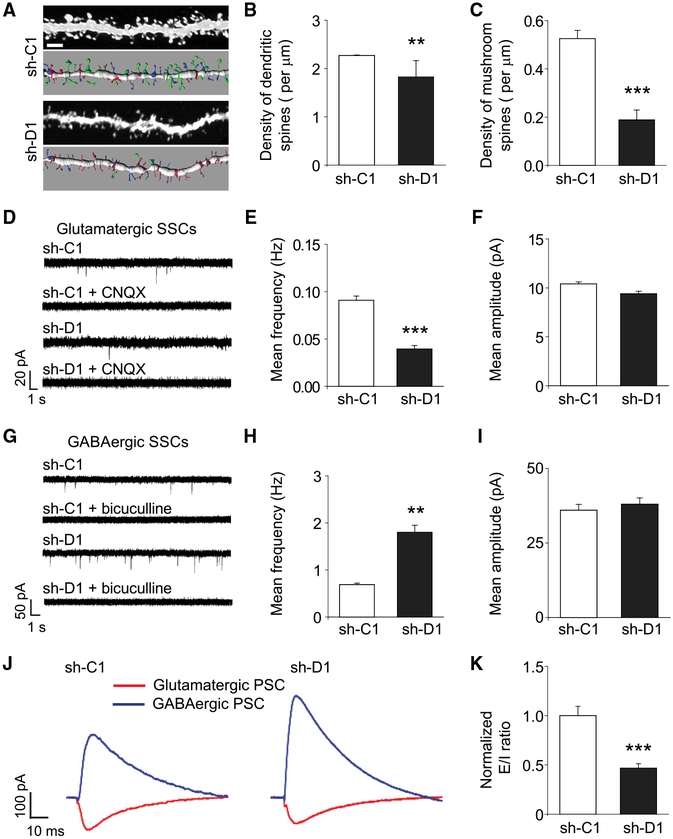

Using retroviruses co-expressing GFP and a previously validated small hairpin RNA (shRNA) against mouse Disc1 (sh-D1) or control shRNA (sh-C1) for birth-dating, genetic manipulation, and labeling (Duan et al., 2007), we assessed the impact of DISC1 deficiency on synaptic properties of GFP+ adult-born granule neurons in the dentate gyrus at 28 days post retrovirus injection (dpi), a time point when behavioral deficits were observed in mice with DISC1 knockdown in newborn neurons (Zhou et al., 2013). Quantification of morphological synapses with confocal microscopy revealed lower total dendritic spine density in DISC1 mutant neurons (Figures 1A and 1B). Notably, the density of morphologically mature mushroom spines was drastically reduced in mutant neurons, suggesting deficits in the formation and/or maintenance of glutamatergic synapses (Figures 1A and 1C). Electrophysiological whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings of GFP+ neurons in acutely prepared brain slices from retrovirus-injected animals further showed reduced frequency, but not amplitude, of glutamatergic spontaneous synaptic currents (SSCs) in mutant neurons at 28 dpi (Figures 1D–1F). In contrast, the mean frequency, but not amplitude, of GABAergic SSCs, was increased in mutant neurons (Figures 1G–1I). The antagonistic changes in glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptic transmission in mutant neurons suggested an E-I imbalance. Indeed, when we recorded evoked excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic currents (PSCs) from the same cells in response to perforant path stimulation (Ge et al., 2006), we found a decreased E-I ratio of PSCs in mutant neurons at 28 dpi (Figures 1J and 1K).

Figure 1. DISC1 Deficiency Leads to E-I Imbalance of Adult-Born Mature Dentate Granule Neurons In Vivo.

(A–C) Confocal microscopy analyses of dendritic spines. GFP+ newborn neurons expressing control shRNA (sh-C1) or shRNA against mouse Disc1 (sh-D1) were examined at 28 dpi.

(A) Sample confocal projection images and Imaris reconstruction images of dendritic fragments. Scale bar, 2 μm. Spine subtypes are color coded in the reconstructed images: mushroom spines (green), long-thin spines (blue), and stubby spines (red).

(B and C) Summaries of densities of total dendritic spines (B) and mushroom spines (C). Values represent mean ± SEM (n = 32–56 dendritic fragments from two to four animals for each sample; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Student’s t test).

(D–I) GABAergic and glutamatergic spontaneous synaptic currents (SSCs) recorded in GFP+ neurons from acutely prepared slices from retrovirus-injected brains.

(D and F) Sample traces of glutamatergic SSCs recorded from GFP+ neurons at 28 dpi in the presence of bicuculline (10 μM) (D), and summaries of mean frequency (E) and amplitude (F) of glutamatergic SSCs. CNQX (20 mM) was added to confirm glutamatergic SSCs.

(G–I) Sample traces of GABAergic SSCs recorded from GFP+ neurons in the presence of CNQX (20 μM) (G), and summaries of mean frequency (H) and amplitude (I) of GABAergic SSCs. Bicuculline (10 μM) was added to confirm GABAergic SSCs. Values represent mean ± SEM (n = 5–6 cells for each sample; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Student’s t test).

(J and K) Evoked excitatory and inhibitory post synaptic currents (PSCs) recorded in GFP+ neurons in response to perforant pathway stimulation at 28 dpi. Shown are sample recording traces (J) and summary of the E-I ratio of PSCs (K). Values represent mean ± SEM (n = 5 cells for each sample; ***p < 0.001; Student’s t test).

Depolarizing GABA Signaling Promotes Synapse Formation of DISC1 Deficit Immature Neurons

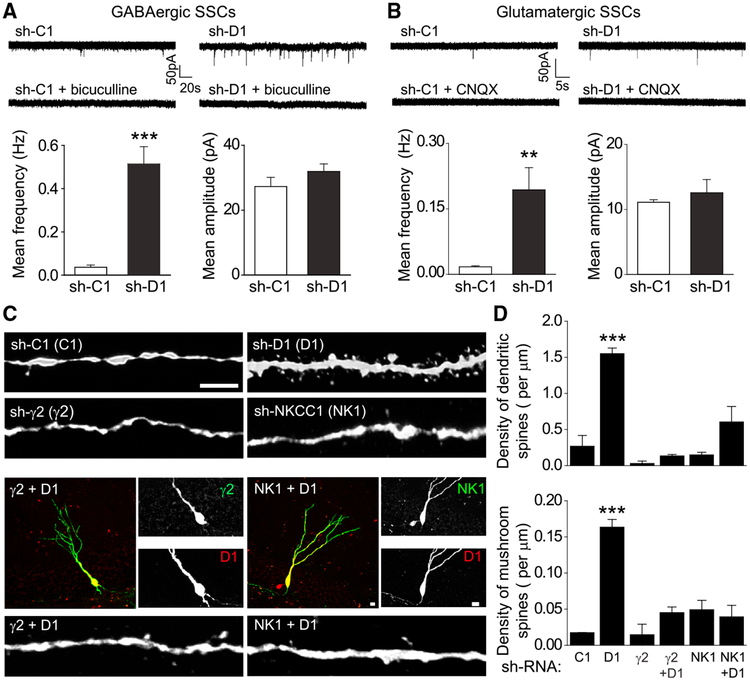

To investigate the developmental origin of E-I imbalance in mutant neurons, we examined synaptic properties of immature neurons at 14 dpi. Electrophysiological recordings of GFP+ neurons showed drastically increased frequencies, but not amplitudes, of both GABAergic and glutamatergic SSCs in mutant neurons (Figures 2A and 2B). Confocal microscopy analysis also showed increased densities of total dendritic spines and mushroom spines in mutant neurons (Figures 2C and 2D). Thus, DISC1 deficiency leads to elevated GABAergic synapse formation but diametric outcomes on glutamatergic synapses at immature and mature neuron stages.

Figure 2. Depolarizing GABA Signaling Promotes Synapse Formation of DISC1-Deficient Immature Neurons.

(A and B) GABAergic and glutamatergic synaptic transmission recorded in GFP+ neurons expressing sh-C1 or sh-D1 at 14 dpi. Similar to Figures 1D–1I, shown are sample recording traces and summaries of mean frequency and amplitude of GABAergic (A) and glutamatergic (B) SSCs. Values represent mean ± SEM (n = 6–7 cells; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Student’s t test).

(C and D) Retrovirus co-expressing GFP and a shRNA against the γ2 subunit of GABAAR (γ2), or a shRNA against Nkcc1 (NK1), and those co-expressing RFP and sh-D1 (D1) were co-injected into the adult dentate gyrus and dendritic spines were examined at 14 dpi. Shown are sample confocal images (C; scale bar, 5 μm) and quantification of densities of total dendritic spines and mushroom spines (D). Values represent mean ± SEM (n = 28–57 cells from two to four animals for each sample; ***p < 0.001; ANOVA).

During development, GABAergic synapses are formed before glutamatergic synapses and GABA-induced depolarization of immature neurons promotes glutamatergic synapse formation (Cancedda et al., 2007; Chancey et al., 2013; Espósito et al., 2005; Ge et al., 2006, 2007a; Kim et al., 2012; Song et al., 2013). Therefore, we next examined how elevated GABAergic synaptic transmission resulting from DISC1 deficiency may impact glutamatergic synapse formation in immature neurons. We suppressed GABA signaling in newborn neurons by co-injecting two retroviruses: one co-expressing red fluorescent protein (RFP) and sh-D1, and the other co-expressing GFP and a previously characterized shRNA against the γ2 subunit of GABAAR (Kim et al., 2012). Because the low number of GFP+RFP+ newborn neurons in these experiments precluded electrophysiological analysis, we performed confocal analysis of dendritic spines at 14 dpi. While knockdown of γ2 itself has no significant effect on the dendritic spine development, reducing γ2-GABAAR-mediated GABA signaling largely prevented precocious dendritic spine formation in DISC1 mutant immature neurons at 14 dpi (Figures 2C and 2D). Furthermore, the effect of GABA signaling on synapse formation requires its depolarizing action (Owens and Kriegstein, 2002), as co-expression of a previously characterized shRNA against Nkcc1 also largely prevented a DISC1 deficiency-induced increase of dendritic spine formation, whereas knockdown of Nkcc1 itself did not show decreased dendritic spine development (Figures 2C and 2D). Together, these results indicate that depolarizing GABA signaling drives glutamatergic synapse formation on immature neurons under pathological conditions.

Excessive PV+ Interneuron Synaptic Inputs Drive Precocious GABAergic and Glutamatergic Synapse Formation on DISC1-Deficient Immature Neurons

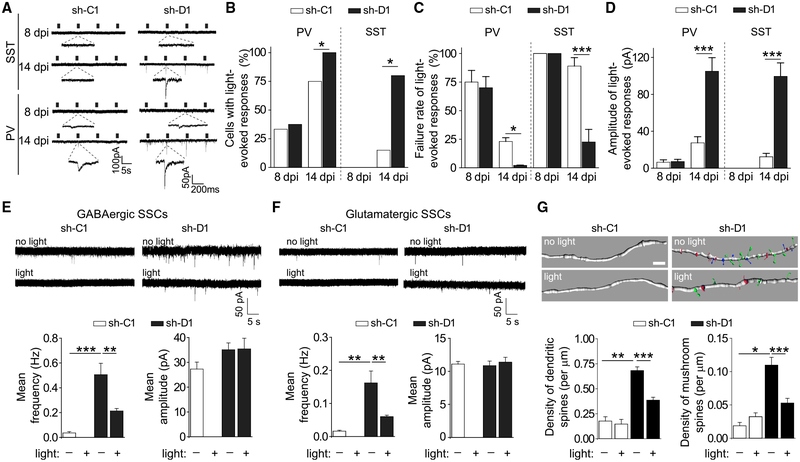

We next sought to identify the local source(s) of GABA that influence synapse formation in immature neurons. Previous trans-synaptic tracing (Bergami et al., 2015; Deshpande et al., 2013; Li et al., 2013; Vivar et al., 2012) and electrophysiological (Espósito et al., 2005; Markwardt et al., 2011; Song et al., 2013) analyses have identified interneuron subtypes that innervate adult-born neurons older than 6 weeks, but not immature neurons, in the adult dentate gyrus. We employed a rabies virus-mediated retrograde mono-synaptic tracing approach (Bergami et al., 2015; Osakada and Callaway, 2013). We first injected a mixture of retroviruses, one co-expressing shRNA, RFP, and the EnvA receptor (TVA) to limit the infection of primary rabies virus to newborn neurons as the starter population, and the other expressing glycoprotein (G), which is required for retrograde transfer to the first-order presynaptic partners of the starter neurons (Osakada and Callaway, 2013) (Figures S1A and S1B). One week later, we injected EnvA-pseudotyped DG rabies virus expressing GFP into the same region and waited another week before analysis (Figure S1B). At 14 dpi, we found only GFP+ Parvalbumin+ (PV+) interneurons innervating control neurons, but both GFP+PV+ and GFP+ somatostatin+ (SST+) interneurons innervating mutant neurons (Figure S1C). To quantitatively and functionally assess GABAergic synaptic inputs from PV+ or SST+ interneurons onto newborn neurons, we employed an optogenetic-aided electrophysiological approach. We used an adeno associated virus-double-floxed inverse orientation (AAV-DIO) system to specifically express ChR2-Tdtomato in PV+ or SST+ interneurons using PV-Cre or SST-Cre mice (Figures S2A and S2B) (Song et al., 2012, 2013). We compared evoked GABAergic PSCs in GFP+ control or mutant neurons in response to optogenetic stimulation of PV+ or SST+ interneurons. At 8 dpi, there were no differences in the properties of PV+ interneuron-mediated GABAergic synaptic inputs onto control and mutant GFP+ neurons, including the percentage of neurons with detectable PSCs, and the failure rates and amplitude of evoked PSCs (Figures 3A–3D). We did not detect any PSCs in response to SST+ interneuron stimulation for either control or mutant neurons at 8 dpi (Figures 3A–3D). In contrast, at 14 dpi, mutant neurons exhibited an increased percentage of recorded cells with PSCs, and a reduced failure rate and increased amplitude of evoked PSCs in response to the stimulation of either PV+ or SST+ interneurons (Figures 3A–3D).

Figure 3. Excessive PV+ Interneuron Synaptic Inputs Drive Precocious GABAergic and Glutamatergic Synapse Formation of DISC1-Deficient Immature Neurons.

(A–D) Quantitative assessment of synaptic inputs from local PV+ or SST+ interneurons using optogenetics and electrophysiology.

(A) Sample traces of light-evoked post-synaptic currents (PSCs) in GFP+ neurons expressing sh-C1 or sh-D1 at 8 and 14 dpi.

(B–D) Quantifications of percentages of recorded cells with detectable light-evoked PSCs (B), failure rate of light-evoked responses (C), and amplitude of light-evoked PSCs (D). Values represent mean ± SEM (n = 4–13 cells for each sample; *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001; Student’s t test).

(E and F) GABAergic and glutamatergic synaptic transmission recorded in GFP+ neurons expressing sh-C1 or sh-D1 at 14 dpi with or without optogenetic suppression of PV+ interneurons between 8 and 14 dpi. Similar to Figures 2A and 2B, shown are sample recording traces and summaries of the mean frequency and amplitude of GABAergic (E) and glutamatergic (F) SSCs. Values represent mean ± SEM (n = 4–10 cells for each sample; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Student’s t test).

(G) Confocal microscopy analyses of dendritic spines at 14 dpi. Similar to Figure 1A, shown are sample Imaris reconstruction images of dendritic fragments. Spine subtypes are color coded in the reconstructed images: mushroom spines (green), long-thin spines (blue), and stubby spines (red). Scale bar, 2 μm. Also shown are summaries of the densities of the total dendritic spines and mushroom spines. Values represent mean ± SEM (n = 46–70 neurons from two to four animals for each sample; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; and ***p < 0.001; Student’s t test).

See also Figures S1, S2, S3, and S4.

To determine the functional impact of these excessive PV+ or SST+ interneuron-mediated GABAergic inputs on synapse formation in immature neurons, we optogenetically suppressed the activity of either PV+ or SST+ interneurons via Arch (Song et al., 2012, 2013). Light stimulation was given between 8 and 14 dpi to suppress PV+ or SST+ interneurons in vivo (Figures S3A and S3B). We have previously shown that this paradigm exhibited a minimal impact on the physiological properties of mature granule neurons examined, such as glutamatergic and GABAergic SSC frequencies and did not lead to significant cell death or physiological properties of PV+ or SST+ neurons in the adult dentate gyrus (Song et al., 2012, 2013). Following suppression of PV+ interneuron activity, we did not detect any GABAergic or glutamatergic SSCs in the control neurons at 14 dpi (Figures 3E and 3F). These results suggest that depolarizing PV+ synaptic inputs onto immature neurons are essential for GABAergic and glutamatergic synapse formation under physiological conditions. Interestingly, suppression of PV+ interneuron activation significantly reduced the DISC1 deficiency-induced elevation of GABAergic SSC frequency with no effect on the amplitude (Figure 3E). Similarly, the DISC1 deficiency-induced increase in glutamatergic SSC frequency and the density of dendritic spines was partially ameliorated (Figures 3F and 3G). In contrast, a similar paradigm of light-induced suppression of SST+ interneuron activation had no detectable effect on either GABAergic or glutamatergic synapses in the control or mutant neurons (Figures S4A–S4F). These results identified a PV+ interneuron-specific neuronal circuit that promotes GABAergic and glutamatergic synapse formation in immature neurons under physiological conditions, and drives precocious synapse formation with DISC1 deficiency.

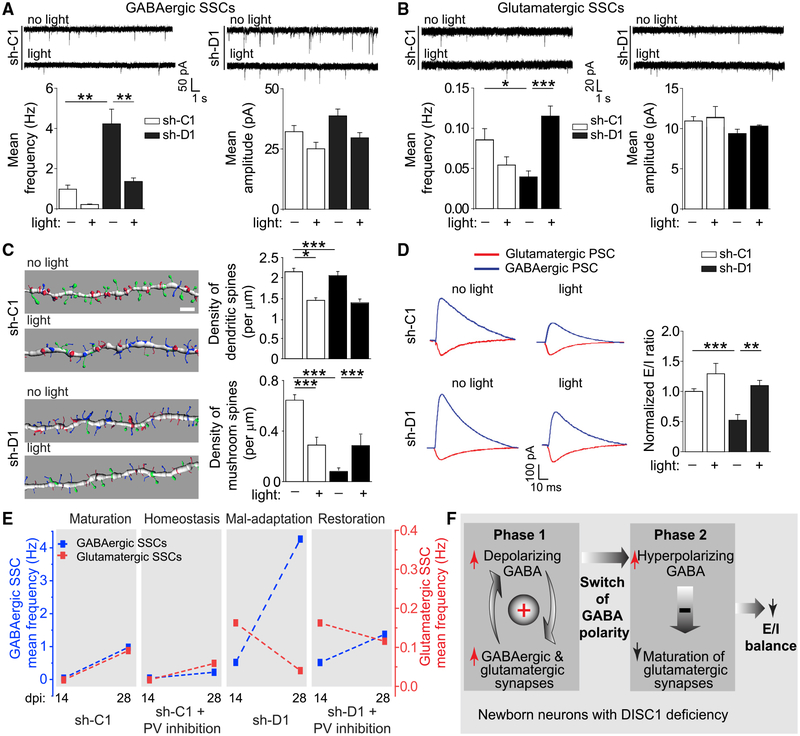

Heightened GABAergic Inhibition Leads to the Loss of Glutamatergic Synapses in Mature DISC1-Deficient Neurons after GABA Polarity Switch

GABA action switches in polarity from depolarizing immature neurons to hyperpolarizing mature neurons during neuronal maturation (Ben-Ari, 2002; Owens and Kriegstein, 2002). Our previous studies using electro-physiology (Ge et al., 2006) and calcium imaging (Kim et al., 2012) have shown that this GABA polarity switch occurs between 14 and 21 dpi during neuronal maturation. To determine the functional impact of inhibitory PV+ GABAergic inputs on synapse formation after the GABA polarity switch, we optogenetically suppressed PV+ interneurons between 22 and 28 dpi (Figure S3C). For control neurons expressing sh-C1 without light stimulation, frequencies of both GABAergic and glutamatergic SSCs increased from 14 to 28 dpi, indicating further synapse formation and maturation during this period under physiological conditions (Figures 4A, 4B, and 4E). Optogenetic suppression of PV+ interneurons significantly decreased the frequency, but not the amplitude, of both GABAergic and glutamatergic SSCs compared to controls without light stimulation (Figures 4A, 4B, and 4E). Total dendritic spine and mushroom spine densities were also reduced (Figure 4C). These results suggest a homeostatic mechanism that can coordinate adaptive changes in excitatory and inhibitory synaptic input formation when the inhibitory input is altered. As a result, the E-I balance was maintained (Figures 4D and 4E). For mutant neurons, however, the already elevated GABAergic SSC levels were increased even further from 14 to 28 dpi without light stimulation (Figure 4E). On the other hand, levels of glutamatergic SSCs and dendritic spine densities decreased from 14 to 28 dpi, suggesting a failure to maintain glutamatergic synapses (Figure 4E). The asymmetry in GABAergic and glutamatergic synapse formation and maintenance exacerbates the E-I imbalance, suggesting a mal-adaptive response (Figures 4D and 4E). Interestingly, optogenetic suppression of PV+ GABAergic inputs tempered this divergent pattern of synapse maintenance. The GABAergic SSC frequency was attenuated in mutant neurons (Figure 4A), whereas the glutamatergic SSC frequency in mutant neurons was increased to levels comparable to those of control neurons (Figures 4B and 4E). The mushroom spine density was also increased compared to the no stimulation control condition in mutant neurons (Figure 4C). The net effect of these changes was the restoration of E-I balance in mutant neurons (Figure 4D). These results suggest that counteracting excessive GABAergic inputs in mutant neurons is sufficient to restore coordinated excitatory and inhibitory synapse formation to maintain E-I balance (Figure 4E).

Figure 4. Heightened PV+ GABAergic Inhibition Leads to a Further Increase in GABAergic Synapses and the Loss of Glutamatergic Synapses in DISC1 Mutant Neurons after the GABA Polarity Switch.

GFP+ neurons expressing sh-C1 or sh-D1 were examined at 28 dpi with or without optogenetic suppression of PV+ interneurons between 22 and 28 dpi.

(A and B) Sample recording traces and summaries of mean frequency and amplitude of GABAergic (A) and glutamatergic (B) SSCs. Values represent mean ± SEM (n = 5–7 cells for each sample; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; and ***p < 0.001; Student’s t test).

(C) Confocal microscopy analyses of dendritic spines. Shown are sample Imaris reconstruction images of dendritic fragments. Spine subtypes are color coded in the reconstructed images: mushroom spines (green), long-thin spines (blue), and stubby spines (red). Scale bar, 2 μm. Also shown are summaries of the densities of the total dendritic spines and mushroom spines. Values represent mean ± SEM (n = 40–51 dendritic fragments from two to four animals for each sample; *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001; Student’s t test).

(D) Sample recording traces and summary of the E-I ratio of PSCs. Values represent mean ± SEM (n = 6–8 cells for each sample; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Student’s t test).

(E) Summary of the time course of GABAergic and glutamatergic SSC frequencies under different conditions. The same data as in Figures 3E, 3F, 4A, and 4B are replotted.

(F) A two-phase model of E-I imbalance development in mutant neurons.

See also Figure S4.

DISCUSSION

First proposed as a model for ASDs (Rubenstein and Merzenich, 2003), synaptic dysfunction from E-I imbalance has been implicated in the pathophysiology and symptomology of many neurodevelopmental disorders (Canitano and Pallagrosi, 2017; Foss-Feig et al., 2017; Gao and Penzes, 2015; Nelson and Valakh, 2015; Sohal and Rubenstein, 2019), including schizophrenia (Kehrer et al., 2008), Rett syndrome (Dani et al., 2005), fragile X syndrome (Gibson et al., 2008), tuberous sclerosis (Bateup et al., 2011), Angelman syndrome (Wallace et al., 2012), and epilepsy (Pallud et al., 2014). A substantial number of studies have investigated deficits of either excitatory glutamatergic synapses or inhibitory GABAergic synapses, yet few studies have examined the dynamic interaction between two systems during neuronal development. Our systematic approach using a genetic risk gene to perturb developmental processes identified circuitry mechanisms underlying the dynamic interplay between GABAergic and glutamatergic synapse formation during development in vivo. Our results suggest a two-phase model for the emergence of E-I imbalance (Figure 4F). During the first phase, when GABA is depolarizing, elevated GABA signaling generates a positive-feedback loop to accelerate synapse formation, resulting in excessive GABAergic and glutamatergic synaptic inputs in DISC1 mutant immature neurons. During the second phase, when the polarity of GABA action switches from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing, heightened inhibition leads to a loss of glutamatergic synapses and further elevation of GABAergic synapse formation, eventually resulting in a disrupted E-I ratio. Our study reveals a circuit-level homeostatic mechanism to coordinate dynamic excitatory and inhibitory synapse formation during neuronal maturation under physiological conditions and identifies the GABA action switch as a pivotal turning point for developing E-I imbalance under pathological conditions (Figure 4F).

Here, we employed abnormal synaptic development by DISC1 deficiency as a model system to investigate neuronal circuit development through homeostatic coordination of inhibitory and excitatory synapse formation. Future studies should aim to elucidate the functional role of DISC1 further at both molecular and circuitry levels. While the molecular mechanisms underlying how DISC1 deficiency contributes to increased GABA transmission in immature newborn granule neurons remain to be elucidated, DISC1 has been reported to negatively regulate AKT (Kim et al., 2009), which activates the chloride importer NKCC1 and inactivates the chloride exporter KCC2 through phosphorylation by WNK3 in brain tumor, renal system, and Xenopus oocytes (Garzon-Muvdi et al., 2012; Kahle et al., 2005; Leng et al., 2006; Rinehart et al., 2005; Zeniya et al., 2013). Thus, DISC1 may participate in controlling the intracellular concentration of chloride in immature granule neurons, which determines the strength of GABAergic neurotransmission.

Even though it is clear that DISC1 knockdown in adult-born dentate granule neurons influences the hippocampal function, as it is sufficient to induce both affective and cognitive behavioral deficits in mice (Zhou et al., 2013), it remains to be determined whether a disrupted E-I balance by DISC1 deficiency leads to dysfunction of the hippocampal neural circuits and mediates the behavioral defects. A recent study has shown that an increased E-I ratio in L2/3 pyramid neurons does not alter neuronal spiking and network excitability in the somatosensory cortex in four mouse models of autism, and suggested that the stability is due to E-I conductance matching (Antoine et al., 2019). A previous study, on the other hand, demonstrated that an increased E-I ratio leads to enhanced activity and hyperexcitability of the hippocampal network in a mouse model of tuberous sclerosis with Tsc1 deficiency (Bateup et al., 2013). These studies suggest that there are different mechanisms or capacities for E-I conductance matching in different neural circuits, which determine whether and how E-I imbalance at the cellular level impacts the network excitability. It is currently unknown whether a decrease of E-I ratio, as observed in the current study, can also undergo conductance matching. Future studies examining whether a disturbed E-I ratio by DISC1 deficiency in individual newborn granule neurons impacts the evoked voltage dynamics, excitability, or synchrony of the hippocampal network will be informative additions to generate insights on the contribution of E-I imbalance to an abnormal circuit activity.

Adult hippocampal neurogenesis provides a unique platform to investigate the impact of genetic insults on neuronal development in vivo at the single-cell level, as it recapitulates the complete process of embryonic neurogenesis with a prolonged temporal resolution (Kang et al., 2016). Adult hippocampal neurogenesis has also attracted much attention through efforts to understand the role of the hippocampus due to the functions of adult-generated granule neurons in cognition, such as spatial learning and memory, and pattern separation (Abrous and Wojtowicz, 2015). It is believed that distinct electrophysiological features of newborn neurons, such as high excitability and enhanced synaptic plasticity, put them in a unique position to be involved in these hippocampal functions (Ge et al., 2007b; Pelkey et al., 2017). Therefore, maintaining and refining the E-I ratio during newborn granule neuron maturation might play an important role in controlling downstream neuronal circuits in the adult hippo-campus. Combination of in vivo extracellular recordings and genetic manipulation of DISC1 in newborn neurons at the population level will be a useful tool to dissect the role of adult-born granule neurons for hippocampal circuit activity and behavioral output. Furthermore, investigating the activity of each of the neuronal populations including mossy cells, mature granule neurons, GABAergic interneurons, and pyramidal neurons in CA1/3, and their collective consequence on hippocampal circuit dynamics, will lead to further understanding of the function of newborn granule neurons in the adult brain.

Our finding that elevated depolarizing GABA signaling is a precursor for the later manifestation of E-I imbalance resonates with a number of recent human genetics findings and clinical observations for developmental brain disorders and here we provide a potential underlying mechanism. First, we previously identified an epistatic interaction between DISC1 and NKCC1 (SLC12A2) that increases risk for schizophrenia in two separate case-control studies (Kim et al., 2012). The same interaction also affects human hippocampal function and connectivity in two independent cohorts (Callicott et al., 2013). Second, independent of DISC1, genetic studies have identified a gain-of-function missense variant in NKCC1 in schizophrenia (Merner et al., 2016) and loss of function variants in KCC2 (SLC12A5) in schizophrenia and ASDs (Merner et al., 2015). Expression of NKCC1 and its regulators have been found to be elevated in postmortem brains of schizophrenia patients (Arion and Lewis, 2011; Dean et al., 2007; Morita et al., 2014). Third, the polarity switch of GABA action was found to be delayed in mouse models of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (Amin et al., 2017) and fragile X syndrome (He et al., 2014), and an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) model of Rett syndrome (Tang et al., 2016). Fourth, in recent clinical trials and case studies, Bumetanide, an NKCC1 antagonist that attenuates depolarizing GABA action, has been shown to alleviate some symptoms of ASDs (Hadjikhani et al., 2015; Lemonnier et al., 2012; Lemonnier et al., 2017), including Asperger syndrome (Grandgeorge et al., 2014), fragile X syndrome (Lemonnier et al., 2013), and schizophrenia (Lemonnier et al., 2016).

In summary, our study suggests a model to explain how interaction between a genetic risk factor and depolarizing GABA signaling can introduce an asymmetry in inhibitory and excitatory synapse formation that disrupts the homeostatic regulation of circuit development. Our findings further provide a perspective for understanding the pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental brain disorders.

STAR★METHODS

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Dr. Guo-li Ming (gming@pennmedicine.upenn.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Animals

All animal experimental procedures were carried out in agreement with the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine. 6–8 weeks old PV-Cre mice (B6;129P2-Pvalbtm1(cre)Arbr/J) and SST-Cre mice (mixed background, Ssttm21(cre)Zjh/J) (Jackson Laboratory), and C57BL/6 (Charles River) were used for the experiments. All experiments were done in both male and female PV-Cre and SST-Cre mice, and female C57BL/6 mice.

METHOD DETAILS

Construction, Production, and Stereotaxic Injection of Engineered Onco-retroviruses, AAV, and Rabies Viruses

Engineered murine oncoretroviruses co-expressing GFP, or RFP, and shRNA were used to birth-date, label, and genetically manipulate proliferating cells and their progeny in the dentate gyrus of adult mouse as previously described (Ge et al., 2006, 2007b; van Praag et al., 2002). The retroviruses expressing specific shRNAs against mouse Disc1, GABAAR-γ2 subunit and Nkcc1 were previously validated (Duan et al., 2007; Ge et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2012). For retrograde mono-synaptic tracing, two different engineered murine oncoretroviruses were used: one co-expresses shRNAs under the U6 promoter and RFP under the Ubiquitin promoter and TVA following the IRES sequence, and the other expresses Glycoprotein under the Ubiquitin promoter (Figure S1A). For experiments without optogenetic manipulations, adult mice housed under standard conditions (6–8 weeks old, female, C57BL/6 background; Charles River) were anaesthetized and retroviruses were delivered by stereotaxic injection into the dentate gyrus at two sites as previously described (Ge et al., 2006, 2007b). For retrograde mono-synaptic tracing, EnvA-pseudotyped rabies viruses lacking Glycoprotein but expressing eGFP (Salk Institute) were stereotaxically injected 7 days after retrovirus injection (Figure S1B). Immunohistological and electrophysiological analysis were performed at 8, 14 or 28 dpi as previously described (Ge et al., 2006, 2007b). For cell-type-specific transgene expression of ChR2-Tdtomato and Arch-Tdtomato, Cre dependent recombinant AAV vectors were purchased from the vector cores of University of North Carolina and University of Pennsylvania (Atasoy et al., 2008; Cardin et al., 2009; Sohal et al., 2009). For experiments with optogenetic manipulations, transgenic PV-Cre mice (B6;129P2-Pvalbtm1(cre)Arbr/J) and SST-Cre mice (mixed background, Ssttm21(cre)Zjh/J) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Stereotaxic injection of AAV was injected stereotaxically with following coordinates: anteroposterior = − 2 mm from Bregma; lateral = ± 1.5 mm; ventral = 2.7 mm. Animals were then allowed to recover for 4–5 weeks before retroviral injection (Figures S2A, S3A, and S3C). Implantation of optical fibers (Doric Lenses, Inc) was performed using the same injection sites at a depth of 1.6 mm from the skull surface. The specificity and efficacy of expression of opsins in PV+ and SST+ interneurons have been previously characterized (Song et al., 2012, 2013). Specifically, we have confirmed that over 90% of PV+ or SST+ neurons were labeled with fluorescent protein tagged ChR2 by AAV virus injection in the dentate gyrus. In addition, we have verified the effective light-induced manipulation of PV+ or SST+ neuron firing in acutely prepared slides using whole-cell recording of ChR2+ neurons upon light-stimulation (Song et al., 2012, 2013). All procedures with animals were carried out in accordance with institutional guidelines.

In Vivo Optogenetic Manipulation, Immunohistochemistry, Image Processing, and Analysis of Dendritic Spines

For optogenetic manipulation in vivo, the light paradigm was administered as previously described (Song et al., 2012, 2013). Briefly, for Arch stimulation, constant yellow light (593 nm) was delivered in vivo through DPSSL laser system (Laser century Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China) for 8 h per day for 7 consecutive days from 8–14 dpi or 22–28 dpi (Figures S3A and S3C). Electrophysiological and histological evaluations showed that these manipulations did not cause deficits in the structural integrity of the dentate gyrus, substantial cell death, or alterations of PV+ or SST+ interneuron properties in the adult dentate gyrus (Song et al., 2012, 2013).

For immunohistology of retrograde mono-synaptic tracing, brains were sectioned in 50 mm thickness coronally (Ge et al., 2006). The following primary antibodies were used: PV (Swant; goat; 1:500) and GFP (Aves Labs; Chicken; 1:1000; Rockland; goat; 1:1000), SST (Millipore; rat; 1:250). Images were obtained on a Zeiss LSM 710 multiphoton confocal system (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA) using a multi-track configuration.

Imaging and analysis of dendritic spines was performed as previously described (Jang et al., 2013). Briefly, dissected hippocampi from fixed mouse brain were cross-sectioned perpendicular to the septal-temporal axis in 50 mm thickness and processed for immunostaining using anti-GFP antibodies (goat, 1:250, Rockland). For complete 3-dimensional reconstruction of spines, a consecutive stack of images (0.22 μm × 0.22 μm, z- step of 0.5 μm) was obtained using an excitation wavelength of 488nm at high magnification (x63, 5 times zoom) to capture the complete depth of dendritic fragments (20–35 mm long) and spines using a confocal microscope (Zeiss). Deconvolution of confocal image stacks was performed in a blind manner (Autoquant). The structure of dendritic fragments and spines were traced using 3–D Imaris software using a “fire” heatmap and a 2D x–y orthoslice plane to aid visualization (Bitplane). Dendritic fragments and dendritic spines were traced using automatic filament tracer and an autopath method with the semi-automatic filament tracer (diameter; min: 0.1, max: 2.0, Contrast 0.8), respectively. Spines were classified using a custom MATLAB (MathWorks) script with the algorithm: stubby: length (spine) < 1.2 and max width (head) < mean width (neck); mushroom: max width (head) >mean width (neck) and max width (head) >0.3; spine was defined as long thin, if it was not categorized as stubby and mushroom. MATLAB script code will be available upon request.

Electrophysiology

Brain slices were prepared from adult mice housed under standard conditions at 14 or 28 dpi as previously described (Ge et al., 2006, 2007b; Song et al., 2012). Briefly, brains were quickly transferred into ice-cold solution (in mM: 110 choline chloride, 2.5 KCl, 1.3 KH2PO4, 25.0 NaHCO3, 0.5 CaCl2, 7 MgSO4, 20 dextrose, 1.3 sodium L-ascorbate, 0.6 sodium pyruvate, 5.0 kynurenic acid). Brains were sectioned into 275 mm think slices using a vibratome (Leica VT1000S) and moved to a chamber containing the external solution (in mM: 125.0 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.3 KH2PO4, 1.3 MgSO4, 25.0 NaHCO3, 2 or 5 CaCl2, 1.3 sodium L-ascorbate, 0.6 sodium pyruvate, 10 dextrose, pH 7.4, 320 mOsm), bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2. Electrophysiological recordings were carried out at 32–34°C. DIC and fluorescence microscopy were used for visualization of GFP+ cells within the dentate gyrus. The whole-cell patch-clamp configuration was employed in the voltage-clamp mode (Vm = [C0]65 mV). Microelectrodes (4–6 MU) were prepared from pulled borosilicate glass capillaries and filled with the internal solution containing (in mM): 135 CsCl gluconate, 15 KCl, 4 MgCl2, 0.1 EGTA, 10.0 HEPES, 4 ATP (magnesium salt), 0.3 GTP (sodium salt), 7 phosphocreatine (pH 7.4, 300 mOsm). Bicuculline (50–100 μM) or CNQX (20 μM) was added in the bath at the following final concentrations as indicated. All chemicals were obtained from Sigma except bicuculline (Tocris). Data were acquired using an Axon 200B amplifier and a DigiData 1322A (Axon Instruments) at 10 kHz.

Experiments with optogenetic stimulation of PV+ or SST+ interneurons expressing ChR2 were performed at 8 or 14 dpi as previously described (Song et al., 2012, 2013). Briefly, light flashes (0.1 Hz) produced by a Lambda DG-4 plus high speed optical switch with a 300W Xenon lamp and a 472 nm filter set (Chroma) were delivered to coronally sectioned slices through a 40X objective (Carl Zeiss)

For evoked glutamatergic and GABAergic PSC recording, microelectrodes were filled with an internal solution containing (in mM): 130 CsMeSO3, 8 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.3 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 4 ATP (magnesium salt), 0.3 GTP (sodium salt), and 10 phosphocreatine (pH 7.4, 300 mOsm). A bipolar electrode (FHC) was used to stimulate the perforant pathway input to the dentate gyrus. Evoked glutamatergic PSCs were isolated by voltage-clamping neurons at the reversal potential of the inhibition (Vh = −70 mV), whereas evoked GABAergic PSCs were recorded at the reversal potential of the excitation (Vh = 0 mV). A total of 20 recording events with intervals of 30 s at each holding potential were used for analysis. E-I ratio was calculated from baseline subtracted traces as the maximum EPSC amplitude divided by the maximum IPSC amplitude. All data were normalized to the mean of control E-I ratio.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All statistical analyses of results were assessed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test as indicated in the text and figure legends. Normality and homogeneity of variation tests were performed using Shapiro-Wik and Levene’s tests, respectively. All statistical analyses were carried out using Origin software (OriginLab).

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Goat-anti-GFP | Rockland | Cat#600–101215; RRID: AB_218182 |

| Chicken-anti-GFP | Aves | Cat#GFP1020; RRID: AB_2734732 |

| Goat-anti-PV | Swant | Cat#PVG213; RRID: AB_2650496 |

| Rat-anti-SST | Millipore | Cat#MAB354; RRID: AB_2255365 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli: XL10-Gold | STRATAGNE | Cat#2000314 |

| AAV2.9-EF1a-DIO-hChR2-TdTomato | University of Pennsylvania Vector Core | N/A |

| AAV2.9-EF1a-DIO-Arch-TdTomato | University of Pennsylvania Vector Core | N/A |

| Rabies virus: SADDG | Salk Institute | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Bicuculline | Tocris | Cat#0130 |

| CNQX | Sigma | Cat#c127 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| B6;129P2-Pvalbtm1(cre)Arbr/J | The Jackson Laboratory | Stock#: 017320 |

| Ssttm.2.1(cre)Zjh/J | The Jackson Laboratory | Stock#: 010708 |

| C57BL/6 | Charles River | Stock#: 27 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Plasmid: pSUbGW | Kang et al., 2011 | N/A |

| Plasmid: pSUbGW-shRNA-DISC1 | Kang et al., 2011 | N/A |

| Plasmid: SUbRW-shRNA-DISC1 | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid: pSUbGW-shRNA-gamma2 | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid: pSUbGW-shRNA-NKCC1 | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid: shRNA-RFP-TVA | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid: Glycoprotein | This paper | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Zen | ZEISS | https://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/us/products/microscope-software/zen-lite.html |

| Origin | OriginLab | https://www.originlab.com/ |

| Imaris | Bitplane | https://www.bitplane.com/imaris |

| MATLAB | Math Works | https://www.mathworks.com/products/matlab.html |

Highlights.

Interaction between DISC1 deficiency and depolarizing GABA leads to E-I imbalance

PV+ interneurons coordinate glutamatergic and GABAergic synapse formation

Polarity switch of GABA action plays a pivotal role in developing E-I imbalance

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Ming and Song laboratories for comments and suggestions, D. Johnson for technical support, and J. Schnoll for lab coordination. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01MH105128 and R35NS097370 to G.-L.M. and R37NS047344 to H.S.) and from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD) to G.-L.M., H.S., and E.K.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2019.07.024.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Abrous DN, and Wojtowicz JM (2015). Interaction between Neurogenesis and Hippocampal Memory System: New Vistas. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 7, a018952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin H, Marinaro F, De Pietri Tonelli D, and Berdondini L (2017). Developmental excitatory-to-inhibitory GABA-polarity switch is disrupted in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: a potential target for clinical therapeutics. Sci. Rep 7, 15752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoine MW, Langberg T, Schnepel P, and Feldman DE (2019). Increased Excitation-Inhibition Ratio Stabilizes Synapse and Circuit Excitability in Four Autism Mouse Models. Neuron 101, 648–661.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arion D, and Lewis DA (2011). Altered expression of regulators of the cortical chloride transporters NKCC1 and KCC2 in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 68, 21–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atasoy D, Aponte Y, Su HH, and Sternson SM (2008). A FLEX switch targets Channelrhodopsin-2 to multiple cell types for imaging and long-range circuit mapping. J. Neurosci 28, 7025–7030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateup HS, Takasaki KT, Saulnier JL, Denefrio CL, and Sabatini BL (2011). Loss of Tsc1 in vivo impairs hippocampal mGluR-LTD and increases excitatory synaptic function. J. Neurosci 31, 8862–8869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateup HS, Johnson CA, Denefrio CL, Saulnier JL, Kornacker K, and Sabatini BL (2013). Excitatory/inhibitory synaptic imbalance leads to hippo-campal hyperexcitability in mouse models of tuberous sclerosis. Neuron 78, 510–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y (2002). Excitatory actions of gaba during development: the nature of the nurture. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 3, 728–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y, and Spitzer NC (2004). Nature and nurture in brain development. Trends Neurosci 27, 361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergami M, Masserdotti G, Temprana SG, Motori E, Eriksson TM, Göbel J, Yang SM, Conzelmann KK, Schinder AF, Götz M, and Berninger B (2015). A critical period for experience-dependent remodeling of adult-born neuron connectivity. Neuron 85, 710–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon NJ, and Sawa A (2011). Linking neurodevelopmental and synaptic theories of mental illness through DISC1. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 12, 707–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callicott JH, Feighery EL, Mattay VS, White MG, Chen Q, Baranger DA, Berman KF, Lu B, Song H, Ming GL, and Weinberger DR (2013). DISC1 and SLC12A2 interaction affects human hippocampal function and connectivity. J. Clin. Invest 123, 2961–2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancedda L, Fiumelli H, Chen K, and Poo MM (2007). Excitatory GABA action is essential for morphological maturation of cortical neurons in vivo. J. Neurosci 27, 5224–5235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canitano R, and Pallagrosi M (2017). Autism Spectrum Disorders and Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders: Excitation/Inhibition Imbalance and Developmental Trajectories. Front. Psychiatry 8, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardin JA, Carlén M, Meletis K, Knoblich U, Zhang F, Deisseroth K, Tsai LH, and Moore CI (2009). Driving fast-spiking cells induces gamma rhythm and controls sensory responses. Nature 459, 663–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chancey JH, Adlaf EW, Sapp MC, Pugh PC, Wadiche JI, and Over-street-Wadiche LS (2013). GABA depolarization is required for experience-dependent synapse unsilencing in adult-born neurons. J. Neurosci 33, 6614–6622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyaya B, and Cristo GD (2012). GABAergic circuit dysfunctions in neurodevelopmental disorders. Front. Psychiatry 3, 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubb JE, Bradshaw NJ, Soares DC, Porteous DJ, and Millar JK (2008). The DISC locus in psychiatric illness. Mol. Psychiatry 13, 36–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani VS, Chang Q, Maffei A, Turrigiano GG, Jaenisch R, and Nelson SB (2005). Reduced cortical activity due to a shift in the balance between excitation and inhibition in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 12560–12565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean B, Keriakous D, Scarr E, and Thomas EA (2007). Gene expression profiling in Brodmann’s area 46 from subjects with schizophrenia. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 41, 308–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande A, Bergami M, Ghanem A, Conzelmann KK, Lepier A, Götz M, and Berninger B (2013). Retrograde monosynaptic tracing reveals the temporal evolution of inputs onto new neurons in the adult dentate gyrus and olfactory bulb. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, E1152–E1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan X, Chang JH, Ge S, Faulkner RL, Kim JY, Kitabatake Y, Liu XB, Yang CH, Jordan JD, Ma DK, et al. (2007). Disrupted-In-Schizophrenia 1 regulates integration of newly generated neurons in the adult brain. Cell 130, 1146–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espósito MS, Piatti VC, Laplagne DA, Morgenstern NA, Ferrari CC, Pitossi FJ, and Schinder AF (2005). Neuronal differentiation in the adult hippocampus recapitulates embryonic development. J. Neurosci 25, 10074–10086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner RL, Jang MH, Liu XB, Duan X, Sailor KA, Kim JY, Ge S, Jones EG, Ming GL, Song H, and Cheng HJ (2008). Development of hippocampal mossy fiber synaptic outputs by new neurons in the adult brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 14157–14162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss-Feig JH, Adkinson BD, Ji JL, Yang G, Srihari VH, McPartland JC, Krystal JH, Murray JD, and Anticevic A (2017). Searching for Cross-Diagnostic Convergence: Neural Mechanisms Governing Excitation and Inhibition Balance in Schizophrenia and Autism Spectrum Disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 81, 848–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao R, and Penzes P (2015). Common mechanisms of excitatory and inhibitory imbalance in schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders. Curr. Mol. Med 15, 146–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzon-Muvdi T, Schiapparelli P, ap Rhys C, Guerrero-Cazares H, Smith C, Kim DH, Kone L, Farber H, Lee DY, An SS, et al. (2012). Regulation of brain tumor dispersal by NKCC1 through a novel role in focal adhesion regulation. PLoS Biol 10, e1001320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S, Goh EL, Sailor KA, Kitabatake Y, Ming GL, and Song H (2006). GABA regulates synaptic integration of newly generated neurons in the adult brain. Nature 439, 589–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S, Pradhan DA, Ming GL, and Song H (2007a). GABA sets the tempo for activity-dependent adult neurogenesis. Trends Neurosci 30, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S, Yang CH, Hsu KS, Ming GL, and Song H (2007b). A critical period for enhanced synaptic plasticity in newly generated neurons of the adult brain. Neuron 54, 559–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JR, Bartley AF, Hays SA, and Huber KM (2008). Imbalance of neocortical excitation and inhibition and altered UP states reflect network hyperexcitability in the mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J. Neurophysiol 100, 2615–2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glausier JR, and Lewis DA (2013). Dendritic spine pathology in schizophrenia. Neuroscience 251, 90–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandgeorge M, Lemonnier E, Degrez C, and Jallot N (2014). The effect of bumetanide treatment on the sensory behaviours of a young girl with Asperger syndrome. BMJ Case Rep 2014, bcr2013202092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjikhani N, Zürcher NR, Rogier O, Ruest T, Hippolyte L, Ben-Ari Y, and Lemonnier E (2015). Improving emotional face perception in autism with diuretic bumetanide: a proof-of-concept behavioral and functional brain imaging pilot study. Autism 19, 149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi-Takagi A, Takaki M, Graziane N, Seshadri S, Murdoch H, Dunlop AJ, Makino Y, Seshadri AJ, Ishizuka K, Srivastava DP, et al. (2010). Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) regulates spines of the gluta-mate synapse via Rac1. Nat. Neurosci 13, 327–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q, Nomura T, Xu J, and Contractor A (2014). The developmental switch in GABA polarity is delayed in fragile X mice. J. Neurosci 34, 446–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutsler JJ, and Zhang H (2010). Increased dendritic spine densities on cortical projection neurons in autism spectrum disorders. Brain Res 1309, 83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang MH, Bonaguidi MA, Kitabatake Y, Sun J, Song J, Kang E, Jun H, Zhong C, Su Y, Guo JU, et al. (2013). Secreted frizzled-related protein 3 regulates activity-dependent adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Cell Stem Cell 12, 215–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahle KT, Rinehart J, de Los Heros P, Louvi A, Meade P, Vazquez N, Hebert SC, Gamba G, Gimenez I, and Lifton RP (2005). WNK3 modulates transport of Cl- in and out of cells: implications for control of cell volume and neuronal excitability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 16783–16788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang E, Wen Z, Song H, Christian KM, and Ming GL (2016). Adult Neurogenesis and Psychiatric Disorders. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 8, a019026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang EC, Burdick KE, Kim JY, Duan X, Guao JU, Sailor KA, Jung DE, Ganesan S, Choi S, Pradhan D, et al. (2011). Interaction between FEZ1 and DISC1 in Regulation of Neuronal Development and Risk for Schizophrenia. Neuron 72, 559–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrer C, Maziashvili N, Dugladze T, and Gloveli T (2008). Altered Excitatory-Inhibitory Balance in the NMDA-Hypofunction Model of Schizophrenia. Front. Mol. Neurosci 1, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, Duan X, Liu CY, Jang MH, Guo JU, Pow-anpongkul N, Kang E, Song H, and Ming GL (2009). DISC1 regulates new neuron development in the adult brain via modulation of AKT-mTOR signaling through KIAA1212. Neuron 63, 761–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, Liu CY, Zhang F, Duan X, Wen Z, Song J, Feighery E, Lu B, Rujescu D, St Clair D, et al. (2012). Interplay between DISC1 and GABA signaling regulates neurogenesis in mice and risk for schizophrenia. Cell 148, 1051–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemonnier E, Degrez C, Phelep M, Tyzio R, Josse F, Grandgeorge M, Hadjikhani N, and Ben-Ari Y (2012). A randomised controlled trial of bumetanide in the treatment of autism in children. Transl. Psychiatry 2, e202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemonnier E, Robin G, Degrez C, Tyzio R, Grandgeorge M, and Ben-Ari Y (2013). Treating Fragile X syndrome with the diuretic bumetanide: a case report. Acta Paediatr 102, e288–e290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemonnier E, Lazartigues A, and Ben-Ari Y (2016). Treating Schizophrenia With the Diuretic Bumetanide: A Case Report. Clin. Neuropharmacol 39, 115–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemonnier E, Villeneuve N, Sonie S, Serret S, Rosier A, Roue M, Brosset P, Viellard M, Bernoux D, Rondeau S, et al. (2017). Effects of bumetanide on neurobehavioral function in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 7, e1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng Q, Kahle KT, Rinehart J, MacGregor GG, Wilson FH, Canessa CM, Lifton RP, and Hebert SC (2006). WNK3, a kinase related to genes mutated in hereditary hypertension with hyperkalaemia, regulates the K+ channel ROMK1 (Kir1.1). J. Physiol 571, 275–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Stam FJ, Aimone JB, Goulding M, Callaway EM, and Gage FH (2013). Molecular layer perforant path-associated cells contribute to feed-forward inhibition in the adult dentate gyrus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 9106–9111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y, Ge X, Frank CL, Madison JM, Koehler AN, Doud MK, Tassa C, Berry EM, Soda T, Singh KK, et al. (2009). Disrupted in schizophrenia 1 regulates neuronal progenitor proliferation via modulation of GSK3beta/beta-catenin signaling. Cell 136, 1017–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markwardt SJ, Dieni CV, Wadiche JI, and Overstreet-Wadiche L (2011). Ivy/neurogliaform interneurons coordinate activity in the neurogenic niche. Nat. Neurosci 14, 1407–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merner ND, Chandler MR, Bourassa C, Liang B, Khanna AR, Dion P, Rouleau GA, and Kahle KT (2015). Regulatory domain or CpG site variation in SLC12A5, encoding the chloride transporter KCC2, in human autism and schizophrenia. Front. Cell. Neurosci 9, 386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merner ND, Mercado A, Khanna AR, Hodgkinson A, Bruat V, Awadalla P, Gamba G, Rouleau GA, and Kahle KT (2016). Gain-of-function missense variant in SLC12A2, encoding the bumetanide-sensitive NKCC1 co-transporter, identified in human schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res 77, 22–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita Y, Callicott JH, Testa LR, Mighdoll MI, Dickinson D, Chen Q, Tao R, Lipska BK, Kolachana B, Law AJ, et al. (2014). Characteristics of the cation cotransporter NKCC1 in human brain: alternate transcripts, expression in development, and potential relationships to brain function and schizophrenia. J. Neurosci 34, 4929–4940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SB, and Valakh V (2015). Excitatory/Inhibitory Balance and Circuit Homeostasis in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Neuron 87, 684–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osakada F, and Callaway EM (2013). Design and generation of recombinant rabies virus vectors. Nat. Protoc 8, 1583–1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens DF, and Kriegstein AR (2002). Is there more to GABA than synaptic inhibition? Nat. Rev. Neurosci 3, 715–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallud J, Le Van Quyen M, Bielle F, Pellegrino C, Varlet P, Cresto N, Baulac M, Duyckaerts C, Kourdougli N, Chazal G, et al. (2014). Cortical GABAergic excitation contributes to epileptic activities around human glioma. Sci. Transl. Med 6, 244ra89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkey KA, Chittajallu R, Craig MT, Tricoire L, Wester JC, and McBain CJ (2017). Hippocampal GABAergic Inhibitory Interneurons. Physiol. Rev 97, 1619–1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinehart J, Kahle KT, de Los Heros P, Vazquez N, Meade P, Wilson FH, Hebert SC, Gimenez I, Gamba G, and Lifton RP (2005). WNK3 kinase is a positive regulator of NKCC2 and NCC, renal cation-Cl- cotransporters required for normal blood pressure homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 16777–16782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein JL, and Merzenich MM (2003). Model of autism: increased ratio of excitation/inhibition in key neural systems. Genes Brain Behav 2, 255–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito A, Taniguchi Y, Rannals MD, Merfeld EB, Ballinger MD, Koga M, Ohtani Y, Gurley DA, Sedlak TW, Cross A, et al. (2016). Early post-natal GABAA receptor modulation reverses deficits in neuronal maturation in a conditional neurodevelopmental mouse model of DISC1. Mol. Psychiatry 21, 1449–1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshadri S, Faust T, Ishizuka K, Delevich K, Chung Y, Kim SH, Cowles M, Niwa M, Jaaro-Peled H, Tomoda T, et al. (2015). Interneuronal DISC1 regulates NRG1-ErbB4 signalling and excitatory-inhibitory synapse formation in the mature cortex. Nat. Commun 6, 10118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal VS, and Rubenstein JLR (2019). Excitation-inhibition balance as a framework for investigating mechanisms in neuropsychiatric disorders. Mol. Psychiatry, Published online May 14, 2019. 10.1038/s41380-019-0426-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal VS, Zhang F, Yizhar O, and Deisseroth K (2009). Parvalbumin neurons and gamma rhythms enhance cortical circuit performance. Nature 459, 698–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Zhong C, Bonaguidi MA, Sun GJ, Hsu D, Gu Y, Meletis K, Huang ZJ, Ge S, Enikolopov G, et al. (2012). Neuronal circuitry mechanism regulating adult quiescent neural stem-cell fate decision. Nature 489, 150–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Sun J, Moss J, Wen Z, Sun GJ, Hsu D, Zhong C, Davoudi H, Christian KM, Toni N, et al. (2013). Parvalbumin interneurons mediate neuronal circuitry-neurogenesis coupling in the adult hippocampus. Nat. Neurosci 16, 1728–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Kim J, Zhou L, Wengert E, Zhang L, Wu Z, Carromeu C, Muotri AR, Marchetto MC, Gage FH, and Chen G (2016). KCC2 rescues functional deficits in human neurons derived from patients with Rett syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 751–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson PA, Malavasi EL, Grünewald E, Soares DC, Borkowska M, and Millar JK (2013). DISC1 genetics, biology and psychiatric illness. Front. Biol. (Beijing) 8, 1–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG, and Nelson SB (2004). Homeostatic plasticity in the developing nervous system. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 5, 97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag H, Schinder AF, Christie BR, Toni N, Palmer TD, and Gage FH (2002). Functional neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Nature 415, 1030–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivar C, Potter MC, Choi J, Lee JY, Stringer TP, Callaway EM, Gage FH, Suh H, and van Praag H (2012). Monosynaptic inputs to new neurons in the dentate gyrus. Nat. Commun 3, 1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace ML, Burette AC, Weinberg RJ, and Philpot BD (2012). Maternal loss of Ube3a produces an excitatory/inhibitory imbalance through neuron type-specific synaptic defects. Neuron 74, 793–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Charych EI, Pulito VL, Lee JB, Graziane NM, Crozier RA, Revilla-Sanchez R, Kelly MP, Dunlop AJ, Murdoch H, et al. (2011). The psychiatric disease risk factors DISC1 and TNIK interact to regulate synapse composition and function. Mol. Psychiatry 16, 1006–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye F, Kang E, Yu C, Qian X, Jacob F, Yu C, Mao M, Poon RYC, Kim J, Song H, et al. (2017). DISC1 Regulates Neurogenesis via Modulating Kinetochore Attachment of Ndel1/Nde1 during Mitosis. Neuron 96, 1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yizhar O, Fenno LE, Prigge M, Schneider F, Davidson TJ, O’Shea DJ, Sohal VS, Goshen I, Finkelstein J, Paz JT, et al. (2011). Neocortical excitation/inhibition balance in information processing and social dysfunction. Nature 477, 171–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeniya M, Sohara E, Kita S, Iwamoto T, Susa K, Mori T, Oi K, Chiga M, Takahashi D, Yang SS, et al. (2013). Dietary salt intake regulates WNK3-SPAK-NKCC1 phosphorylation cascade in mouse aorta through angiotensin II. Hypertension 62, 872–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Li W, Huang S, Song J, Kim JY, Tian X, Kang E, Sano Y, Liu C, Balaji J, et al. (2013). mTOR Inhibition ameliorates cognitive and affective deficits caused by Disc1 knockdown in adult-born dentate granule neurons. Neuron 77, 647–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.