Introduction

Psoriasis and lupus erythematosus (LE) are autoimmune diseases that affect the skin. Patients with these diseases may share a similar genetic predisposition, as genome-wide association studies have identified common genetic polymorphisms. Yet, the coexistence of these diseases is uncommon, an observation previously thought to be owing to the T helper (Th)2 immune predominance in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in contra-distinction to the Th1 immune predominance in psoriasis. A review of more than 1800 SLE patients at the Toronto Lupus Clinic found that the incidence of psoriasis is increased in this population compared with the general population (estimated at 3.89% in their cohort compared with 1.6% in the Canadian population).1 Patients with concurrent SLE and psoriasis may have unusual photosensitive psoriasis with the initial presentation of psoriasis lesions on the sun-exposed extremities.2, 3

The treatment of psoriasis in patients with SLE can be problematic. Phototherapy is generally avoided. Antimalarial medications such as hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine may induce photosensitivity and psoriasis, although this notion has been mostly based on case reports and small series. Ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody to the p40 subunits of the interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23 receptors, is a safe and efficacious treatment for psoriasis and has been used anecdotally to treat subacute cutaneous LE4 and hypertrophic LE.5 Ustekinumab has shown possible efficacy in cutaneous LE when used to treat 5 patients with coexisting psoriasis and LE.6 Ustekinumab has recently been studied as a treatment for SLE in a phase 2 study of 102 adults showing improvement in musculoskeletal and cutaneous disease activity at 24 weeks.7

Here we report on 3 patients treated with ustekinumab for psoriasis. Two patients with prior SLE had new-onset lupus nephritis while on ustekinumab. A third individual had probable SLE with vasculitis and nephritis while on ustekinumab. This case series highlights similarities in clinical presentation suggesting a common mechanism.

Case reports

Case 1

A woman in her 30s presented with hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia, malar rash, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, and pericarditis. SLE was the diagnosis. Treatment included plasmapheresis, high-dose prednisone, azathioprine, and hydroxychloroquine. One year later, biopsy-proven psoriasis developed. Multiple therapies including methotrexate, acitretin, and antimalarial withdrawal failed to improve her skin condition (Fig 1). Her psoriasis worsened over 6 years. She was started on ustekinumab (45 mg every 12 weeks). This treatment improved her skin condition at 4 months (Psoriasis Activity and Severity Index [PASI], 13.3 to 1.8). Anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies developed shortly after the initiation of ustekinumab. She presented 6 months later with increasing fatigue, vasculitis, and vasculopathic skin lesions on both palms and proximal nail fold, increasing anti–double-stranded DNA, and hypocomplementemia. This condition was treated as a lupus flare with intravenous methylprednisone followed by prednisone. Twenty months after ustekinumab initiation, she had worsening fatigue, bilateral pleural effusions, pancytopenia, and increased inflammatory markers. Prednisone and azathioprine dosage were increased. Scaly plaques to both palms were noted with histopathology consistent with acral discoid LE. At 24 months, she had proteinuria and hematuria. Renal biopsy showed class IV S(A) diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis with lupus microangiopathy (Fig 1). She was treated with cyclophosphamide, a switch from azathioprine to mycophenolate mofetil, and ustekinumab discontinuation.

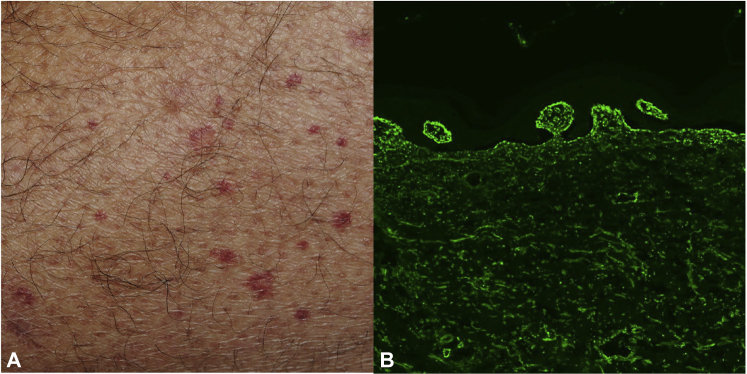

Fig 1.

Presentation with small plaque/papular psoriasis on sun-exposed areas in a patient with prior SLE (A). Development of proximal nail fold infarcts (B) 10 months after ustekinumab therapy. Periodic acid–Schiff–stained glomerulus shows segmental endocapillary hypercellularity and a small cellular crescent (C). (Original magnification: ×200)

Case 2

A man in his 40s presented with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA). His skin was treated with topical therapy and phototherapy. His antinuclear antibody (ANA) was negative. His PsA was refractory to hydroxychloroquine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, sulfasalazine, leflunomide, methotrexate, and cyclosporine. He subsequently did not respond to infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, and etanercept and remained ANA−. Treatment with ustekinumab (45 mg every 12 weeks) was started 15 years after presentation, with significant improvement of his skin (PASI score from 13.6 to 5.2), but limited improvement of PsA. Eleven months after initiation, his ustekinumab dose was increased from 45 to 90 mg every 12 weeks for better joint control. His PASI improved further to 0.3. At 24 months, the patient was hospitalized with worsening renal function and palpable purpura (Fig 2). A renal biopsy showed full house granular immune-reactant deposition (IgG, IgM, IgA, C1q, and C3) at the glomerular basement membrane consistent with membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis with immune complexes. Skin biopsy confirmed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with a positive lupus band but no vascular immune reactants (Fig 2). Additional investigations found a positive ANA at 1:80 speckled pattern and low C3 levels. The diagnosis was probable SLE. The patient was treated with cyclophosphamide, but he had persistent renal failure.

Fig 2.

Palpable purpura in patient with prior psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis at 24 months of ustekinumab therapy (A). Biopsy-confirmed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with perivascular neutrophils, leukocytoclastic debris, and red blood cell extravasation with no vascular immunoglobulin or complement deposition but with full-house granular immune-reactant deposition (IgG, IgM, IgA, C3) at the basement membrane zone (B). (IgG direct immunofluorescence; original magnification, ×100.)

Case 3

A female in her 20s was assessed for SLE and psoriasis. She had presented in her teens with malar rash, parotitis, interstitial lung disease, arthritis, and retinal vasculitis. SLE was diagnosed, and she was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone. Her course was complicated by macrophage activation syndrome requiring cyclosporine and cyclophosphamide. She was subsequently maintained on mycophenolate mofetil with subsequent minimal disease activity. Psoriasis developed, and she was started on ustekinumab 4 years later. Because her SLE was stable, mycophenolate mofetil was held. Nephrotic syndrome with class V lupus nephritis developed after 3 months of ustekinumab treatment, requiring renewed corticosteroids and mycophenolate mofetil. Her nephritis was ascribed to mycophenolate mofetil discontinuation, and ustekinumab was continued with good control of skin (previously described in Tselios et al1).

Discussion

The use of ustekinumab in psoriasis is associated with an excellent safety profile. However, isolated reports exist of immune-mediated adverse events in patients treated with this drug: cases of small vessel vasculitis,8 bullous pemphigoid,9, 10, 11 and linear IgA bullous dermatosis12 have been described. These cases indicate that antibody-antigen complex disease (vasculitis) and loss of B-cell tolerance with autoantibody-mediated disease (immune-bullous disease) may occur in patients undergoing IL-12 and IL-23 inhibition (Table I).

Table I.

Autoantibody and antibody-mediated immune phenomena in patients treated with ustekinumab

| Age | Sex | Ustekinumab indication | Prior autoimmune-mediated disease | New clinical manifestation after ustekinumab | Ustekinumab duration at time of onset of new disease (mo) | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 43 | F | Psoriasis | Prior SLE | Lupus nephritis vasculopathy | 20 | Current study |

| 46 | M | Psoriasis Psoriatic arthritis |

None | Probable lupus Nephritis (membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis with immune complex) Vasculitis |

24 | Current study |

| 25 | F | Psoriasis | Prior SLE | Lupus nephritis | 3 – Ustekinumab continued | Current study and Tselios et al,1 2017 |

| 62 63 58 |

M M M |

Psoriasis Psoriatic arthritis Psoriasis |

None Not reported Not reported |

Bullous pemphigoid | 10 18 2 |

Le Guern et al,9 2015 Nakayama et al,10 2015 Onsun et al,11 2017 |

| 31 | F | Psoriasis | Not reported | Linear IgA bullous dermatosis | 2 | Becker 201612 |

SLE is a complex disease with multiple manifestations. A defect in dead cell clearance and type 1 interferon production are thought to underlie the susceptibility for SLE resulting in dysregulated cell-mediated autoimmunity as noted in cutaneous disease and autoantibody-mediated immunity as noted in renal disease. The cases described here share the onset of autoantibody-mediated nephritis at 3 to 24 months after ustekinumab therapy for psoriasis. Two cases include the development of small vessel vasculitis/vasculopathy. These events occurred with a variable delay after the introduction of ustekinumab, akin to paradoxical psoriasis described with the use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. The potential role of ustekinumab is highlighted by the overall lower incidence of lupus nephritis and vasculitis noted in patients with concurrent SLE and psoriasis compared with SLE alone.1 Although these rare events do not prove causality, we propose that augmentation of autoantibody production and autoantibody-related disease may be a consequence of simultaneous IL-12 and IL-23 inhibition. Patients with SLE have been noted to have low levels of IL-12 and p34 RNA suggesting that inhibition of this cytokine may promote a shift to Th2 immunity.13 Ongoing therapy with ustekinumab in case 3 did not lead to further autoantibody-mediated immunity, suggesting a stochastic element to this effect. Further, the development of ANAs in patients with psoriasis treated with ustekinumab is likely a rare event.14

Clinicians and investigators should be aware of the possibility of enhancement of antibody-mediated autoimmunity in patients with SLE treated with ustekinumab. Because B-cell–activating factor of the tumor necrosis factor family (BAFF) polymorphisms have been associated with B-cell–mediated autoimmunity,15 the role of this polymorphism and BAFF levels in exacerbation of disease after ustekinumab therapy deserves further investigation.

Acknowledgments

Dr Dutz is a Senior Scientist at the BC Children's Hospital Research Institute. Dr Al Khalili received an immune-dermatology fellowship award from the Sultanate of Oman. We would like to thank Dr Martin Trotter for cutaneous histopathology and immune-histology expertise, Drs Mei Lin Bissonette and Alexander Magil for renal pathology and immune-histology, and Dr Jose Guerrero for helpful comments.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: Dr Dutz has received consulting fees and speaker's fees from Abbvie, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Novartis and Pfizer. The rest of the authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Tselios K., Yap K.S., Pakchotanon R. Psoriasis in systemic lupus erythematosus: a single-center experience. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36(4):879–884. doi: 10.1007/s10067-017-3566-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Millns J.L., Muller S.A. The coexistence of psoriasis and lupus erythematosus. An analysis of 27 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116(6):658–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zalla M.J., Muller S.A. The coexistence of psoriasis with lupus erythematosus and other photosensitive disorders. Acta Derm-Venereol Suppl. 1996;195:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Souza A., Ali-Shaw T., Strober B.E., Franks A.G., Jr. Successful treatment of subacute lupus erythematosus with ustekinumab. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(8):896–898. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winchester D., Duffin K.C., Hansen C. Response to ustekinumab in a patient with both severe psoriasis and hypertrophic cutaneous lupus. Lupus. 2012;21(9):1007–1010. doi: 10.1177/0961203312441982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varada S., Gottlieb A.B., Merola J.F., Saraiya A.R., Tintle S.J. Treatment of coexistent psoriasis and lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(2):253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Vollenhoven R.F., Hahn B.H., Tsokos G.C. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, an IL-12 and IL-23 inhibitor, in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a multicentre, double-blind, phase 2, randomised, controlled study. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1330–1339. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacArthur K.M., Merkel P.A., Van Voorhees A.S., Nguyen J., Rosenbach M. Severe small-vessel vasculitis temporally associated with administration of ustekinumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(3):359–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Guern A., Alkeraye S., Vermersch-Langlin A., Coupe P., Vonarx M. Bullous pemphigoid during ustekinumab therapy. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1(6):359–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2015.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakayama C., Fujita Y., Watanabe M., Shimizu H. Development of bullous pemphigoid during treatment of psoriatic onycho-pachydermo periostitis with ustekinumab. J Dermatol. 2015;42(10):996–998. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Onsun N., Sallahoglu K., Dizman D., Su O., Tosuner Z. Bullous pemphigoid during ustekinumab therapy in a psoriatic patient. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27(1):81–82. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2016.2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Becker J.G., Mundi J.P., Newlove T., Mones J., Shupack J. Development of linear IgA bullous dermatosis in a patient with psoriasis taking ustekinumab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(4):e150–e151. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.11.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu T.F., Jones B.M., Wong R.W., Srivastava G. Impaired production of IL-12 in systemic lupus erythematosus. III: deficient IL-12 p40 gene expression and cross-regulation of IL-12, IL-10 and IFN-gamma gene expression. Cytokine. 1999;11(10):805–811. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez-Jimenez P., Chicharro P., Godoy A., Llamas-Velasco M., Garcia M., Dauden E. No evidence for induction of autoantibodies or autoimmunity during treatment of psoriasis with ustekinumab. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(3):862–863. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steri M., Orru V., Idda M.L. Overexpression of the Cytokine BAFF and autoimmunity risk. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(17):1615–1626. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]