Abstract

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are rare cancers with an associated prolonged survival in some patients. A proportion of patients diagnosed with NETs will present with carcinoid syndrome symptoms, characterized by diarrhea, flushing and/or wheezing. This review summarizes the current treatment options for carcinoid syndrome, focusing on the latest novel treatment option, telotristat ethyl. In addition, information on patient-reported outcomes and impact of carcinoid syndrome on quality of life (QOL) and improvement of following treatment with telotristat ethyl are reviewed. This article also provides an overview of the current QOL questionnaires for patients with NETs and addresses unmet needs in this field of patient-reported outcomes.

Keywords: telotristat ethyl, carcinoid syndrome, NET, diarrhea

Introduction

Neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) arise from enterochromaffin cells. Gastro-entero-pancreatic (GEP) NENs are the most frequent origin (incidence rate of 3.56 per 100 000 population/year), followed by lung (incidence rate of 1.49 per 100 000) and unknown primary (incidence rate of 0.84 per 100 000).1,2

NENs can be classified according to different features (Table 1). Based on the most updated WHO classification, NENs are divided into well-differentiated (neuroendocrine tumors (NET)) or poorly differentiated (neuroendocrine carcinomas) based on morphology.3 In addition, they are categorized as grade 1 (<3%), grade 2 (3–20%) or grade 3 (>20%) according to the Ki67 proliferation index.3 NENs can also be classified as functioning or nonfunctioning based on their hormonal secretion status.4

Table 1.

Classification of NENs

| Differentiation features | Grade | Ki 67 | Functioning status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Well-differentiated (NE tumors) |

1 | <3% | Functioning |

| 2 | 3–20% | ||

| 3 | >20% | ||

| Poor-differentiated (NE carcinomas) |

3 | >20% | Non- functioning |

Abbreviations: NE, neuroendocrine; NENs, neuroendocrine neoplasms.

Carcinoid syndrome

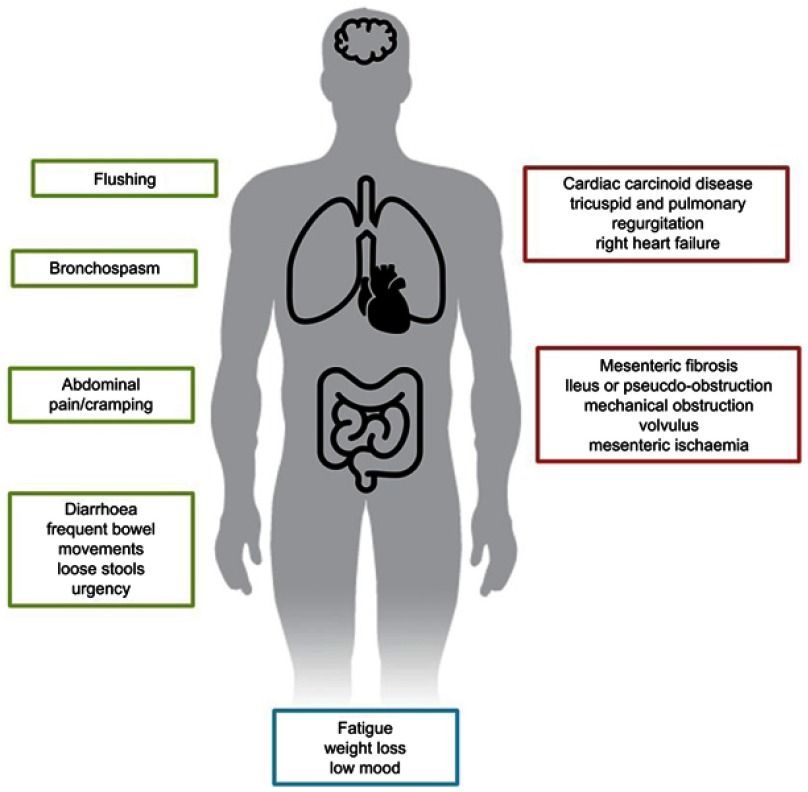

Although a variety of hormone secretion-related syndromes are described, carcinoid syndrome represents the most frequent one for NENs. Carcinoid syndrome comprises a set of symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain or abdominal cramping, flushing episodes and bronchospasm (Figure 1). In addition, chronic complications such as endocardial fibrosis, leading to carcinoid heart disease, and mesenteric fibrosis can arise. Carcinoid syndrome affects approximately 18.6% of all patients with NETs, according to the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database, and most commonly is associated with gastrointestinal and bronchopulmonary origin.5 Most patients with clinically evident carcinoid syndrome have liver metastases. In contrast, patients diagnosed with lung NETs may develop carcinoid syndrome in the absence of liver metastases due to direct access of the hormones to the general circulation, avoiding portal circulation and, ultimately, liver metabolism.

Figure 1.

Carcinoid syndrome.

Serotonin has been identified as the main agent involved in carcinoid syndrome symptoms; overproduction of serotonin stimulates intestinal motility causing diarrhea and abdominal pain, and also stimulates fibroblast growth factor receptors, leading to heart valve and peritoneal fibrosis. Carcinoid syndrome may also be due to secretion of other hormones, such as substance P, neurotensin, prostaglandins, tachykinins and kallikrein. The latter is a potent vasodilator, and its presence has been linked to flushing.6,7

The fibroblast growth factor pathway is highly activated in NETs with carcinoid syndrome as a consequence of serotonin release. This leads mainly to mesenteric and heart valve fibrosis, with fibrosis of other areas reported less frequently.8,9 The exact mechanism underlying carcinoid heart disease is not completely understood.10 Chronic exposure of cardiac endothelium to serotonin is the main hypothesis; in fact, increased 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), a metabolite of serotonin, levels have been correlated with increased carcinoid heart disease severity.11,12 In addition, the presence of tachykinins, neurokinin A or substance P has also been associated with the development of carcinoid heart disease.8,13 Fibrosis of heart valves induces thickening and retraction of the valve cusps, leading to insufficient coaptation and regurgitation, especially of right heart valves. Due to an increment of pressure in the right cavities, patients develop right heart failure. Development of carcinoid heart disease is a late event in patients with carcinoid syndrome, and patients are usually asymptomatic until very advanced stages when they present with right heart failure–related symptoms. In order to increase awareness and early diagnosis, current guidelines suggest screening and follow-up of patients with carcinoid syndrome for carcinoid heart disease.4,9,14–16 It has been suggested that treatment inducing a reduction of serotonin levels may stop and/or prevent heart valve deterioration. Unfortunately, there is limited evidence available regarding treatments with the capacity to change the natural history of carcinoid heart disease.

Mesenteric fibrosis commonly develops around the primary tumor, secondary to a desmoplastic reaction. This fibrosis can lead to a complete obstruction or a volvulus and less frequently to mesenteric ischemia. The mechanism underlying this condition is presumed to be similar to those underlying carcinoid heart disease; thus, it is hypothesized that reduction in serotonin levels may prevent this complication.8,9

Patients diagnosed with NENs and carcinoid syndrome are known to report worse quality of life (QOL) compared to the general population as several surveys have shown.17–20 For patients with carcinoid syndrome, diarrhea and flushing seem to be the most limiting symptoms; patients who reported a greater average number of bowel movements per day or more flushing episodes had worse scores in the QOL scales.17,21

Within the population of patients with carcinoid syndrome, data suggest that the intensity of carcinoid symptoms is directly associated with QOL. Those patients with 4 or more bowel movements per day and those patients with any flushing episode in a 2-week period are the ones with a worse QOL.17,21 A recent survey assessing NET-related QOL was developed by a patient association and was answered by a total number of 1928 patients diagnosed with NETs. Results confirmed that the most frequent symptoms were fatigue, diarrhea, abdominal pain/cramping and flushing. Most patients (71%) reported a moderate to substantial negative impact of the disease on their daily life. Energy levels, emotional health, ability to participate in leisure activities and social life and ability to care for family or finances were particularly affected.22,23

Treatment of refractory carcinoid syndrome

Due to the impact on patients' long-term complications and QOL, it is important to achieve adequate control of carcinoid syndrome. Symptomatic control of diarrhea with antidiarrheal agents, such as loperamide, codeine or atropine/diphenoxylate, has been used with variable efficacy. Ondansetron, a serotonin receptor agonist usually employed for the treatment of chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting, has been explored in carcinoid syndrome because of its action mechanism. There are some studies with promising results, but the number of patients included is too small to draw definitive conclusions.24,25

In addition to the symptomatic management mentioned above, somatostatin analogs (SSA) are the first-line treatment recommended by international guidelines for patients with advanced functioning NETs, especially for those with carcinoid syndrome.26 Two long-acting SSAs are available, octreotide LAR and lanreotide Autogel. In addition, there are short-acting octreotide formulations that can be employed as “rescue” treatment to help with symptomatic control.

The rate of improvement of carcinoid syndrome-related symptoms with SSAs has been reported to be high: around 70% for unselected populations9,10,27,28 (symptoms control rates of 74.2% for octreotide and 67.5% for lanreotide have been described in a pooled data analysis)29, and around 50% for patients with “highly functioning” carcinoid syndrome.11,30–32 The converse of this is that some patients have limited or no benefit from SSAs in symptom improvement, thus requiring alternative strategies (primary resistance). Moreover, a proportion of patients may develop worsening symptoms despite initial response to SSAs and would therefore also benefit from additional treatment (secondary resistance). Resistance mechanisms to SSAs are not completely understood. Several mechanisms have been described, such as tachyphylaxis as a consequence of downregulation of somatostatin receptors (SSTRs), mutations in the SSTR or in regulatory proteins (amphiphysin IIb), antibody formation against SSAs, alternative pathways activation and truncated SSTR variants.33–36

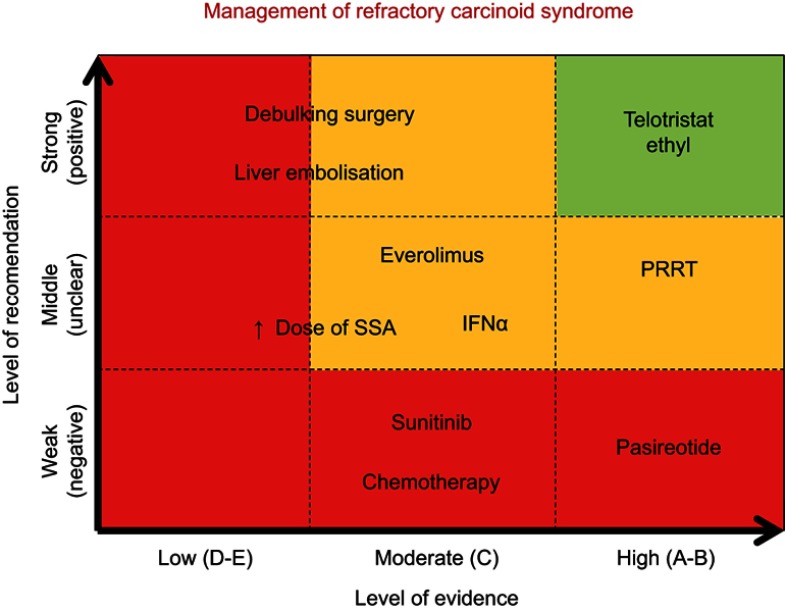

Strategies for management of refractory carcinoid syndrome can be divided into two main groups: local and systemic approaches. Figure 2 provides an overview of the evidence supporting each one of these potential treatment options.

Figure 2.

Overview of available treatment options for refractory carcinoid syndrome. Level of recommendation is classified as strong (positive) when there is literature available showing positive results and improvement of patient symptoms; weak (negative) if literature has shown no benefit on management of carcinoid syndrome; middle (unclear) if controversy exists. Level of evidence is classified as follows: Level A: there exists a meta-analysis of high standard or several randomized trials with consistent results; Level B: if randomized studies (level B1), therapeutic trials, quasi-experimental trials, or comparisons of populations (level B2) provide consistent results when considered together; Level C: there exist studies, therapeutic trials, quasi-experimental trials, or comparisons of populations, of which the results are not consistent when considered together; Level D: if either scientific data do not exist or there is only a series of cases; expert agreement: data do not exist but the experts are unanimous in their judgment.

Note: ↑, Increased.

Abbreviations: SSA, somatostatin analogs; PRRT, peptide receptor radionuclide therapy, INFα, alpha-interferon.

Local strategies with the aim of reducing liver disease burden (ie debulking surgery or liver arterial embolization) for symptomatic relief can be pursued in selected patients.1,34

Systemic alternatives have been investigated as follows:

In SSA refractory carcinoid syndrome, dose escalation or shortening the interval between injections could be an alternative, even though supporting evidence is of limited quality.37–39 The development of novel SSAs to date (ie pasireotide) has been disappointing in this scenario. Standard SSAs target mainly SSTR subtype 2 (SSTR2); on the contrary, pasireotide is a novel SSA with high binding affinity to four of the five known SSTR subtypes (1, 2, 3 and 5). This was the rationale for testing pasireotide in patients with refractory NETs. Unfortunately, results have not shown a significant improvement in either symptomatic relief40,41 or tumor growth control,42,43 and its development is currently on hold in this indication.

Alpha-interferon is an immunomodulatory drug that has been used in patients with NETs for many years. It has a role in the relief of carcinoid symptoms, by reducing both diarrhea and flushing.44–50 This benefit seems to correlate with a reduction in urinary 5-HIAA levels. Benefit for tumor growth control has also been reported.51 The toxicity profile includes flu-like symptoms, depression, tiredness and leukopenia.

The role of targeted therapies such as everolimus52–56 or sunitinib57 in the treatment of carcinoid syndrome has not been confirmed in prospective studies, and their use for symptomatic management remains controversial. In addition, due to the limited response to chemotherapy in patients with intestinal well-differentiated NETs, chemotherapy has limited activity in this setting.58–63

Currently, the most promising alternatives in the treatment of carcinoid syndrome include peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT)64,65 and inhibitors of serotonin synthesis (ie telotristat ethyl). A QOL analysis from the pivotal trial with PRRT reported that the overall time to deterioration (TTD) of symptoms was significantly longer in the PRRT arm compared with the octreotide arm with 22.7-month difference in median TTD between both arms (HR=0.41), including time to worsening diarrhea (HR=0.473).65

Table 2 provides more information about the efficacy of these treatments in the control of carcinoid syndrome as well as their impact on the QOL.

Table 2.

Systemic management of refractory carcinoid syndrome

| Treatment | Mechanism of action | Trial | Symptoms and QOL assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSA: octreotide and lanreotide | Agonist of somatostatin receptors, principally SSTR2. Antisecretory and antiproliferative effects | PROMID. Octreotide Phase 3 (Rinke A, 2009)37 | 38.8% patients with carcinoid syndrome. Symptomatic improvement, especially in flushing. QOL assessment (secondary end point). EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire. Similar scores in both arms. |

| CLARINET. Lanreotide Phase 3 (Caplin ME, 2014)38 | Number of functioning tumors included unknown. QOL assessment (secondary end point). EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-GINET21 questionnaires. No differences in global health status in both arms. |

||

| ELECT. Lanreotide Phase 3 (Vinik AI, 2016. Fisher GA, 2018)27,28 | All patients with carcinoid syndrome not refractory to SSA. Symptomatic relief (reducing use of short-acting SSA) primary end point: achieved. QOL assessment (secondary end point). EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-GINET21 questionnaires. Improvement in global health status, gastrointestinal and endocrine symptoms scales in lanreotide arm compared with placebo arm. |

||

| New generation SSA: pasireotide | SSA with high binding affinity to four somatostatin receptor subtypes (1, 2, 3 and 5), instead of only SSTR2. Antisecretory and antiproliferative effects |

Phase 2 (Kvols LK, 2012)40 | Number of functioning tumors included unknown. 21% patients experience partial symptom control (did not achieve primary aim: ≥30%) QOL assessment (secondary end point). FACIT-G and FACIT-D questionnaires. No significant changes during the treatment. |

| Phase 3 (Wolin EM, 2015)41 | Most of the patients have functioning tumors (based on u5-HIAA levels) 20% patients experience symptom control, the same as in control arm (octreotide LAR). No QOL assessment. |

||

| Everolimus | mTOR inhibitor | RADIANT-2. Phase 3 (Pavel ME, 2011)52 | Included functioning tumors. Non assessment of symptom control. No QOL assessment. |

| RADIANT-3. Phase 3 (Yao JC, 2011)53 | Functioning tumors excluded. No assessment of symptom control. No QOL assessment. |

||

| RADIANT-4. Phase 3 (Yao JC, 2016)54 | Functioning tumors excluded. QOL assessment (secondary end point). FACT-G questionnaire. No differences between both arms. |

||

| Phase 3b (Pavel ME, 2016)55 | 42% functioning tumors. QOL assessment. EuroQOL-5 dimensions, EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-GINET21 questionnaires. QOL stable in pancreatic NET and slightly impaired in nonpancreatic NET. |

||

| COOPERATE-2. Phase 2 (Kulke MH, 2017)43 | Functioning tumors excluded. No QOL assessment. |

||

| LUNA. Phase 2 (Ferolla P, 2017)42 | Patient with severe symptoms from carcinoid syndrome excluded. No assessment of symptom control. No QOL assessment. |

||

| Sunitinib | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor of VEGFR-1 and 2, FLT3, KIT, PDGFR-A and B | Phase 3 (Raymond E, 2011. Vinik A, 2016)57,112 | Number of patients with carcinoid syndrome unknown (pancreatic NET, other hormone syndromes). QOL assessment (secondary end point). EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire. No differences between both arms. Worsening in diarrhea and fatigue scores with sunitinib. Longer time to deterioration in health global and functional status with sunitinib. |

| PRRT (177Lu-Dotatate) | Radiolabeled peptides specific for the SSTR2 | NETTER-1. Phase 3 (Strosberg J, 2017. Strosberg J, 2018)64,65 | Number of functioning tumors included unknown. QOL assessment (secondary end point). EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-GINET21 questionnaires. Longer time to deterioration of QOL with PRRT in global health, physical functioning and role functioning. Improvement in diarrhea, fatigue and pain scores. |

| Interferon-alpha 2b | Immunomodulatory effect | Smith DB, 198745 | All patients presented with elevated u5HIAA, but only 9/14 (65%) had carcinoid symptoms. Important symptomatic relief (in 55% patients). Improvement in Karnofsky performance status. No QOL assessment. |

| Moertel CG, 198946 | Most of patients (85%) had functioning tumors (carcinoid syndrome). Important symptomatic relief (65% flushing and 33% diarrhea). No QOL assessment. |

||

| Veenhof CHN, 199248 | Most of patients had functioning tumors (carcinoid syndrome). 58% experienced symptomatic relief. No QOL assessment. |

||

| Chemotherapy | Cytotoxicity | STPZ-DX vs STPZ-5FU vs CLZ (Moertel GC, 1992)58 | Only pancreatic-NET. Functioning status unknown. No QOL assessment. |

| 5FUᵟ, DX and STPZ (Kouvaraki MA, 2004)59 | Only pancreatic-NET. 20% functioning, no carcinoid syndrome. No QOL assessment. |

||

| STPZ and liposomal DX (Fjallskog MCH, 2008)113 | Only pancreatic-NET. 23% functioning, no carcinoid syndrome. No QOL assessment. |

||

| TEM-CAP (Strosberg JR, 2011)60 | Only pancreatic-NET. 26% functioning, no carcinoid syndrome. No QOL assessment. |

||

| CAP, STPZ ± Cisplatine (Meyer T, 2014)61 | Pancreatic and gut NET. 36% Functioning, % carcinoid syndrome unknown. QOL assessment. EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire. Worsening in QOL with triple therapy; no changes with double therapy compared to baseline. |

Abbreviations: SSA, somatostatin analog; QOL, quality of life; EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30; QLQ-GINET21, Quality of Life Questionnaire – Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors 21; FACIT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General; FACIT-D, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Diarrhea; u5-HIAA, urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid levels; NET, neuroendocrine tumors; PRRT, peptide receptor radionuclide therapy; STPZ, streptozocin; DX, doxorubicin; 5FU, 5-fluorouracil; CLZ, chlorozotocin; TEM, temozolomide; CAP, capecitabine.

The remaining of this review will be focused on the role of telotristat ethyl for management of carcinoid syndrome.

Metabolism of serotonin

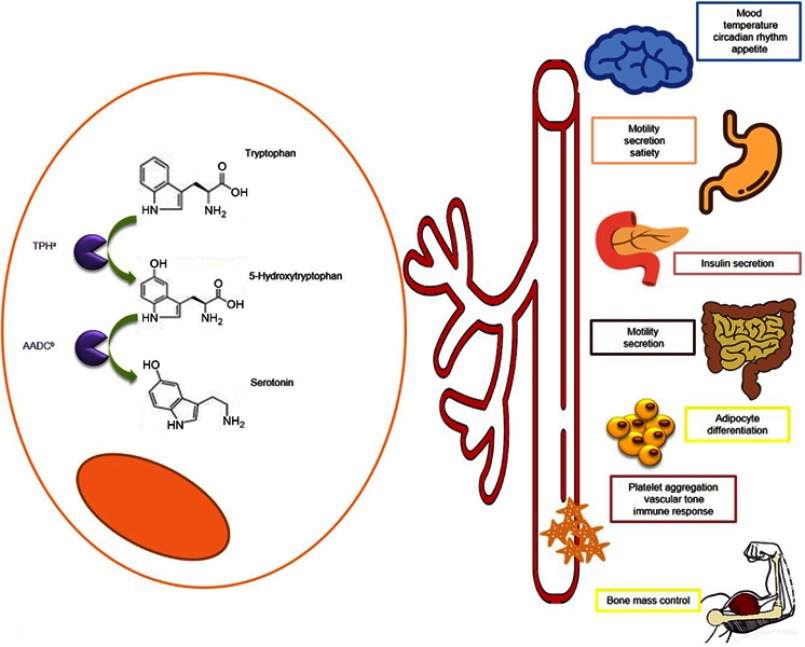

L-tryptophan, precursor of serotonin, is sequentially processed by two enzymes: tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) and aromatic amino acid decarboxylase. Catalyzation by TPH is the rate-limiting step in serotonin synthesis. This enzyme is encoded by two different genes: TPH1 (expressed mainly in enterochromaffin cells in the gastrointestinal tract, and in the pineal gland) and TPH2 (present in the central nervous system and in the enteric nervous system).66–68

Serotonin regulates gut function including bowel motility and secretion; it also controls satiety and nausea. In addition, it participates in other multiple body homeostasis mechanisms (Figure 3) including but not limited to platelet aggregation, erythropoiesis, immune response, temperature regulation, circadian rhythmicity and mood. It also influences insulin regulation, bone mass control, adipocyte differentiation, liver regeneration and fibrosis.66,67 Up to 90% of serotonin levels come from the gastrointestinal system, from where serotonin is released into the bloodstream and stored inside platelets. Excess serotonin is degraded into 5-HIAA; this serotonin metabolite is predominantly excreted in the urine.66,67 Therefore, overproduction of serotonin by NETs results in elevated systemic levels of serotonin and can be identified by measuring the 5-HIAA urine metabolite. Measurement of 5HIAA in blood (plasma or serum) is also possible.69

Figure 3.

Serotonin: metabolism and function. L-tryptophan is processed by the tryptophan hydroxylase (TPHa) and aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADCb) becoming in serotonin. Serotonin is released into bloodstream and distributed to the different organs where participates in the regulation of several functions as temperature, mood, circadian rhythm and appetite control, gut secretion and motility, insulin secretion, adipocyte differentiation and bone mass regulation, platelet aggregation, vascular tone and immune response. More details are provided in the figure.

Telotristat ethyl

Telotristat ethyl is an orally administered prodrug, which is converted into its active metabolite: telotristat etiprate (or LP-778902). Telotristat etiprate is a potent inhibitor of serotonin synthesis, by inhibiting TPH function, which results in a reduction of the serotonin bloodstream levels. Due to the high structural similarity between both TPH isoforms, TPH1 and TPH2, telotristat etiprate has a similar affinity for both. Telotristat etiprate’s high molecular weight prevents it from crossing the brain–blood barrier, thus acquiring a “physiological” selectivity for TPH1. Therefore, telotristat etiprate produces a significant reduction of serotonin concentrations in the intestine70 without affecting the function of TPH2 isoform, thus without compromising levels of serotonin in the central nervous system.66,71

Safety profile of telostristat ethyl

Phase I studies in healthy volunteers demonstrated that telotristat ethyl reduced serotonin production and decreased urinary 5-HIAA, with an adequate safety profile. Depression and other psychiatric syndromes were considered adverse events of special interest in these studies due to previous experience with serotonin inhibitors;72 with telotristat ethyl, no neurologic or psychiatric side effects were observed.73,74

Two phase II clinical trials explored the safety of telotristat ethyl in patients diagnosed with refractory carcinoid syndrome. Both trials shared a similar design: single-arm, open-label, dose escalating studies. Overall, treatment was well tolerated, with the most frequently reported adverse events being mild gastrointestinal symptoms and mild hepatic impairment. Only one case of depression was reported in a patient with a previous diagnosis of anxiety disorder.75,76 This favorable toxicity profile was confirmed in phase III studies.77,78

Pivotal phase III trials confirmed this favorable safety profile of telotristat ethyl. More frequently reported adverse events were related to the gastrointestinal tract (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, constipation, abdominal distension, abdominal pain, dyspepsia) and were mainly classified as mild or moderate grade. Increase in hepatic enzymes, especially in gamma-glutamyl transferase, was reported mainly in telotristat ethyl arms. Although depression incidence in the TELECAST trial was similar across groups, in the TELESTAR, more cases were reported in telotristat ethyl 500-mg group compared with the placebo and 250-mg groups.74,75

The incidence of treatment discontinuation secondary to adverse events was 6.7% in each telotristat ethyl group in the TELESTAR trial and 8% in the TELECAST trial. Two deaths in the telotristat ethyl groups and three in the placebo group were reported in the TELESTAR trial (in the setting of advanced disease), whereas none were reported in the TELECAST trial.

During the OLE period, overall adverse events and incidence of treatment discontinuation were similar, regardless of the increased exposure to telotristat ethyl due to crossover from placebo to telotristat ethyl and due to the increased dose of telotristat ethyl from 250 mg to 500 mg.74

In addition, a post-hoc meta-analysis of patients included in both trials was performed to examine the efficacy and safety of telotristat ethyl in combination with lanreotide. The median duration of treatment was similar across treatment groups, being treatment withdrawal rate secondary to adverse events low. Although 60% and 80% of treatment-related adverse events rates were reported in the telotristat ethyl 250 and 500 mg groups , respectively.79

Efficacy of telostristat ethyl

Efficacy of telotristat ethyl was assessed in two pivotal phase III clinical trials: TELESTAR and TELECAST.77,78 These multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trials included patients with uncontrolled carcinoid syndrome. Patients were randomized (1:1:1) to receive placebo or telotristat ethyl 250 mg or 500 mg 3 times per day. The main characteristics of the design of these two clinical trials are summarized in Table 3. Both studies had a 12-week double-blind treatment period followed by a 36-week open-label extension, followed by an expansion phase: TELEPATH study. The primary objective of TELEPATH was to assess the long-term safety of telotristat ethyl; secondary objectives included the impact on patients’ QOL. Final results have not been reported yet.80

Table 3.

Phase III clinical trial designs with telotristat ethyl

| TELESTAR (Kulke, 2016)77 | TELECAST (Pavel, 2018)78 | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 135 | 76 |

| Study design | Prospective, randomized (1:1:1 ratio), placebo-controlled | Prospective, randomized (1:1:1 ratio), placebo-controlled |

| Treatment arms | Telotristat ethyl 250 mg versus Telotristat ethyl 500 mg versus placebo | Telotristat ethyl 250 mg versus telotristat ethyl 500 mg versus placebo |

| Inclusion criteria | ≥18 years old WD-NET biopsy-proven Refractory carcinoid syndrome Stable-dose of SSA for at least 3 months before inclusion |

≥18 years old WD-NET biopsy-proven Documented carcinoid syndrome Stable-dose of SSA for at least 3 months before inclusion |

| Refractory carcinoid syndrome | ≥4BM per day despite SSA treatment for at least 3 months before inclusion u5-HIAA could be above or below the ULN, or unknown |

<4BM per day with a stable dose of SSA, and at least one of the following: - Daily stool consistency ≥5 on the Bristol stool form scale for ≥50% of the days - Daily flushing frequency of ≥2 - Daily rating of ≥3 episodes of abdominal pain - Nausea present ≥20% of the days - u5-HIAA above the ULN Or ≥4BM per day or at least one of the previous items if patient was not on SSA therapy |

| Response | Reduction of at least 30% in BM per day from the baseline | Reduction of at least 30% in BM per day from the baseline Durable: at least 50% of the time in 12 weeks |

| Primary aim | Mean reduction from baseline in daily BM averaged over 12 weeks | Safety: incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events Efficacy: percent change from baseline in 24 hr u5-HIAA levels at week 12 |

| Safety | No serious AE reported. Most of the AE were gastrointestinal (nausea, abdominal pain, vomiting) Depression-related AE occurred in 6.7% of both telotristat ethyl arms and 15.6% of placebo arms. No patient required antidepressant drugs |

No depression-related AE on telotristat ethyl. Two depression-related AE in the expansion phase (OLE) in patients with previous diagnosis of depression at baseline. Gastrointestinal AE mainly, milda: abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation. Not dose-dependent |

| Efficacy | Mean reduction in daily BM frequency from baseline to week 12 was −1.7 and −2.1 with telotristat ethyl 250 mg and 500 mg, respectively, and −0.9 for the placebo arm 42–44% of patients in telotristat ethyl groups are considered as responders. u5-HIAA levels decreased significantly with telotristat ethyl, but increased in placebo arm Slight improvements in other parameters (abdominal pain, urgency, stools consistency, flushing): not statistically significant |

A significant reduction from baseline in u5-HIAA levels at week 12 for both telotristat ethyl arms compared with placebo (−76.5 and −33.2% with telotristat ethyl 500 mg and 250 mg, respectively) 40% considered durable responders in telotristat ethyl groups telotristat ethyl 500 mg had a statistically significant effect on stool consistency. This difference was not achieved between the telotristat ethyl 250 mg and placebo No statistically significant changes in flushing or abdominal pain |

Note: aMild: adverse events were graded in severity by the investigator as mild, moderate or severe.

Abbreviations: WD-NET, well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor; SSA, somatostatin analogs; BM, bowel movements; u5-HIAA, urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid; ULN, upper limit of normal; AE, adverse events.

Both the TELESTAR and TELECAST studies recruited patients with refractory carcinoid syndrome, but definition of “refractory” differed between these studies.77,78 The TELESTAR clinical trial recruited patients with a minimum of 4 bowel movements per day, despite adequate SSAs, thus focusing on refractory carcinoid syndrome-related diarrhea. In contrast, the TELECAST study allowed the recruitment of patients with carcinoid syndrome (diarrhea, flushing, abdominal pain, nausea or elevated u5-HIAA) with <4 bowel movements per day on SSAs (or ≥1 symptom or ≥4 bowel movements per day, if not on SSAs).

The TELESTAR clinical trial reported a significant reduction in daily bowel movements in those patients treated with telotristat ethyl, with a daily bowel movement reduction equivalent to 30% from baseline (Table 4) (absolute mean reduction in number of daily bowel movements from baseline (mean 6.09) to week 12 (mean 4.24) was −1.7 with telotristat ethyl 250 mg three times per day), together with a significant reduction of urinary 5-HIAA levels.77 This led to the approval of telotristat ethyl for refractory carcinoid syndrome-related diarrhea.70 The study failed to show a statistically significant improvement in flushing (p-value 0.39 with telotristat ethyl 250 mg three times per day) which is likely explained as follows: 1) the study was not properly powered for identifying differences in terms of flushing; 2) the low rate of patients (total of 38.5% of the whole population recruited into the TELESTAR study) who reported ≥2 episodes of flushing/day limited even further the power to identify such differences; and 3) flushing is known not be driven by serotonin alone but by a combination of other hormones such as substance P, prostaglandins, tachykinins and kallikrein,81–83 therefore serotonin production decrease may not be enough to control flushing in all the patients with carcinoid syndrome.

Table 4.

Symptom assessment in phase III clinical trials with telotristat ethyl

| TELESTAR (Kulke, 2016)77 | TELECAST (Pavel, 2018)78 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Treatment (week 12) | Baseline | Treatment (week 12) | ||||||||||

| Telotristat ethyl 250 mg (n=45) |

Telotristat ethyl 500 mg (n=45) |

Placebo (n=45) |

Telotristat ethyl 250 mg (n=36) |

Telotristat ethyl 500 mg (n=37) |

Placebo (n=35) |

Telotristat ethyl 250 mg (n=25) |

Telotristat ethyl 500 mg (n=25) |

Placebo (n=26) |

Telotristat ethyl 250 mg (n=25) |

Telotristat ethyl 500 mg (n=25) |

Placebo (n=35) |

||

| BM frequency per day | Mean (SD) | 6.1 (2.1) | 5.8 (2.0) | 5.2 (1.4) | 4.24 (nr) | 3.83 (nr) | 4.34 (nr) | 2.5 (1.2) | 2.8 (1.6) | 2.2 (0.7) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) |

| Arithmetic mean reduction from baseline to week 12& | – | – | – | −1.7 | −2.1 | −0.9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Daily reduction averaged over 12 weeks mean (SD) | – | – | – | −1.43 (1.36) | −1.46 (1.31) | −0.62 (0.83) | – | – | – | −0.45 (0.69) | −0.60 (0.72) | 0.05 (0.33) | |

| p-Valueb | – | – | – | <0.001 | <0.001 | – | – | – | – | 0.004 | <0.001 | – | |

| Abdominal pain score | Mean (SD) | 2.6 (2.3) | 2.6 (2.2) | 2.5 (2.3) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | 1.2 (1.5)a | 1.8 (1.7)a | 1.7 (1.7)a | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) |

| Change from baseline over 12 weeks mean (SD) | – | – | – | −0.49 (1.44) | −0.33 (1.18) | −0.23 (1.16) | – | – | – | −0.23 (0.97) | 0.03 (0.77) | −0.06 (0.78) | |

| p-Valueb | – | – | – | 0.28 | 0.87 | – | – | – | – | 0.61 | 0.66 | – | |

| Flushing episodes per day | Mean (SD) | 2.8 (3.7) | 2.7 (3.4) | 1.8 (1.9) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | 2.7 (3.7) | 1.8 (2.2) | 3.7 (4.1) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) |

| Change from baseline over 12 weeks mean (SD) | – | – | – | −0.30 (1.31) | −0.53 (1.34) | −0.16 (1.16) | – | – | – | −0.06 (0.98) | 0.11 (2.10) | −0.33 (1.22) | |

| p-Valueb | – | – | – | 0.39 | 0.84 | – | – | – | – | 0.67 | 0.58 | – | |

| Stool consistency | Mean (SD) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | 5.1 (0.8) | 5.3 (0.8) | 5.0 (0.9) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) |

| Change from baseline over 12 weeks mean (SD) | – | – | – | −0.26 (0.47) | −0.36 (0.41) | −0.22 (0.48) | – | – | – | −0.20 (0.70) | −0.60 (0.86) | 0.01 (0.41) | |

| p-Valueb | – | – | – | 0.57 | 0.052 | – | – | – | – | 0.09 | 0.009 | – | |

| Daily rescue short-acting SSA use | Mean (SD) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) |

| Change from baseline over 12 weeks mean (SD) | – | – | – | −0.11 (nr) | 0.03 (nr) | 0.18 (nr) | – | – | – | −0.07 (0.35) | 0.01 (0.10) | −0.01 (0.14) | |

| p-Valueb | – | – | – | 0.19 | 0.16 | – | – | – | – | 0.45 | 0.98 | – | |

| Urgency (proportion of days) | Proportion of days mean (SD) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | 0.67 (0.34) | 0.60 (0.31) | 0.75 (0.29) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | nr (nr) |

| p-Valueb | – | – | – | 0.35 | 0.006 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

Notes: aMean weekly abdominal pain rating. bCompared versus placebo arm. &Arithmetic mean reduction in daily BM frequency from baseline to week 12 was only calculated for patients for whom both baseline and week 12 assessments were available.

Abbreviations: BM, bowel movement; nr, not reported; n, number of patients.

The TELECAST study provided confirmatory data about efficacy and safety of telotristat ethyl in a different scenario, as mentioned above. In addition, a significant reduction in urinary 5-HIAA levels and number of daily bowel movements was identified. Patients randomized to 500 mg telotristat ethyl experienced an improvement in stool consistency. No statistically significant improvement was seen in flushing, abdominal pain or requirement of rescue SSAs.78

Impact of telotristat ethyl on carcinoid heart disease and mesenteric fibrosis

There are little data available regarding the impact of telotristat ethyl on carcinoid heart disease and mesenteric fibrosis. Two of the patients recruited into the TELESTAR clinical trial with known carcinoid heart disease had no worsening of fibrosis of heart valves on follow-up echocardiograms.9,10 No data on the impact of mesenteric fibrosis are available.

Clinical benefit from telotristat ethyl

Symptom improvement and QOL have been end points of special interest in the telotristat ethyl clinical trials, especially in phase III studies. These parameters have been assessed through different methods such as interviews, diaries and questionnaires, being the main rationale to understand the impact of reduction of bowel movements on patients' QoL.

Both phase II trials collected symptoms daily through an interactive voice system (IVS).75,76 Kulke et al phase II assessed weekly patient relief perception, via IVS as well, with the question: “In the past 7 days, have you had adequate relief of your carcinoid syndrome bowel complaints such as diarrhoea, urgent need to have a bowel movement, abdominal pain or discomfort?”.76 Interviews have been employed in patients from these phase II trials as well.84

Both phase III studies, TELESTAR and TELECAST, employed electronic diaries,75–78 interviews85 and QOL questionnaires. Symptom assessment focused on the most relevant carcinoid syndrome–related symptoms such as diarrhea (bowel movements per day) and flushing and also on other aspects of interest such as stool consistency (graduated by Bristol Stool form Scale), urgency to defecate, abdominal pain and nausea. In addition, other subjective parameters exploring the impact of treatment on subjective global assessment of symptoms associated with carcinoid syndrome, adequate relief of gastrointestinal symptoms of carcinoid syndrome and need to self-administer short-acting SSA rescue therapy were also explored.77,78

Symptom relief with telotristat ethyl: patient interviews

In addition to the predefined diaries for collection of objective measures such as number of bowel movements, alternative data collection tools were required to assess subjective aspects. Interview format for symptom assessment was used as an attempt to optimize symptom capture and their impact on patients’ daily life. The first approach included 11 patients from the above mentioned phase II clinical trials.84 Only 4 out of these 11 patients were receiving telotristat ethyl at the time of the interview (the rest had already stopped the treatment); thus, low recall accuracy and bias cannot be completely excluded in this scenario due to the long gap between treatment and interview.

At a later stage, a study with a similar design, based on telephonic interviews, was performed. This study included patients from the TELESTAR trial, and interviews were performed at the end of the trial (2 weeks after the end-of-treatment visit, approximately). This design reduced the risk of recall bias and also included a larger sample size (35 patients).85

These interviews provided a reflection on the health problems experienced by patients with carcinoid syndrome, together with the impact of these on their lives. These interviews reported that the number of bowel movements per day was an adequate end point for clinical trials exploring carcinoid syndrome, which was highlighted as the most bothersome symptom and, therefore, the most important symptom to relieve.84,85 In addition, urgency was another of the most commonly reported symptoms.84,85 Fatigue was an important issue too, which was graded as severe in most of the cases. Even though it was associated with the disease itself, some participants perceived that sleep interruptions related to diarrhea also influenced their energy levels.84

Abdominal pain or cramps and flushing episodes were frequently reported, but were not considered as relevant as diarrhea-related problems by patients.84 This did not match with previous data reported by Pearman and colleagues exploring health-related QOL in NET patients, in which the presence of flushing episodes was a significant concern for patients, and the greater the number the episodes, the poorer the QOL.21 This discrepancy is likely to reflect variability in personal experience, since the impact of flushing depends significantly on the lifestyle and working environment of each patient, while the impact of diarrhea may affect every patient in a more homogeneous way.

Lately, weight loss is a frequent concern in patients with carcinoid syndrome, and it was evaluated as an exploratory analysis in the TELESTAR trial. At 12 weeks, weight gain ≥3% was achieved in both telotristat ethyl groups. This increase was statistically significantly superior to the weight gain in the placebo group. Furthermore, patients who put on weight also had an improvement in nutritional parameters and patient-reported outcomes.86

Patients perception of symptom improvement with telotristat ethyl

One of the phase II studies collected patient-reported data regarding “adequate relief of symptoms” on a weekly basis during the 4-week active treatment period.76 Data were available for 80 of the 92 weekly patient assessments. During this period, 56% of the patients on treatment with telotristat ethyl reported adequate relief at least in one or more of the weekly time points, whereas no patients in the placebo arm did so. At the end of the blinded treatment period (week 4), 6 of the 13 patients (46%) on telotristat ethyl who completed the “adequate-relief” assessment reported substantial relief of symptoms.

Impact of telotristat ethyl on QOL: QOL questionnaires

The TELESTAR and TELECAST clinical trials employed the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-C30 questionnaire (combined with the EORTC QLQ-GI.NET21 questionnaire) as the QOL assessment tool.75,76 The EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire was designed for patients with cancer and is useful for most of the cancer subtypes. In contrast, it may not be adequate for patients with a NET diagnosis.87 To address this issue, the EORTC QLQ-GI.NET21 (specifically designed for patients with a NET diagnosis) was also employed. Unfortunately, these two questionnaires combined only provide 1 question regarding diarrhea and 3 regarding other abdominal symptoms (pain, flatulence, bloating); thus, information collected is likely to be limited in patients for whom diarrhea, stool consistency and urgency are of relevance.

The TELESTAR study employed the EORTC QLQ-C30/QLQ-GI.NET21 questionnaire. According to this questionnaire, only modest improvements in overall QOL were reported in patients classified as responders, compared with nonresponders in all three treatment arms. When the diarrhea subscale was explored in detail, significant improvements in both arms randomized to telotristat ethyl compared to the placebo arm were identified. The TELECAST trial QOL results have not been reported yet.77,78 The TELEPATH trial (NTC02026063) is expected to provide more information regarding the impact of telotristat ethyl in terms of QOL, especially in the long term.

Selection of patients for treatment with telotristat ethyl

Based on available phase III data, telotristat ethyl is approved for treatment of refractory carcinoid-syndrome diarrhea. According to clinical trial inclusion criteria, patients with a minimum of 4 daily bowel movements would be the patient population to benefit from this treatment.

The licensed dose of telotristat ethyl is 250 mg three times daily. Dose adjustment is indicated in hepatic impairment.70

It is of critical importance to identify whether the diarrhea that is intended to be treated is related to carcinoid syndrome. Such diagnosis may be confirmed by the presence of concomitant increased 5-HIAA, if other differentials have been ruled out. However, it is important to acknowledge that this was not a required criterion for entry into the TELESTAR clinical trial, and that the presence of carcinoid syndrome in the absence of raised 5-HIAA has been described.88–90

Hence, other causes for refractory diarrhea should be excluded before starting treatment with telotristat ethyl. This includes, but is not limited to fat malabsorption (including SSA-induced pancreatic exocrine insufficiency),20 bile acid malabsorption, enteric pathogens (parasites or Clostridium difficile), short bowel syndrome or malignancy.

Challenges for assessment of symptoms and QOL in patients with carcinoid syndrome

Interview studies previously detailed84,85 have shown how interview-like tools are more likely to provide granularity on symptom improvement, especially for scenarios such as carcinoid syndrome when symptoms and their impact on patients’ daily activities are multifactorial and vary according to patients characteristics. Unfortunately, such interviews require adequate resourcing, which for large phase III studies imply high cost, if the aim is to interview every patient included within the study. Restricting these interviews to a selected population may, however, introduce selection bias and it is therefore likely not to solve this problem. Therefore, access to more simple and user-friendly tools for measuring the impact of treatment on patients QOL and daily symptoms is required. Due to the complexity of carcinoid syndrome, it may not be adequate to use the already available questionnaires designed for patients with cancer or irritable bowel syndrome, especially due to confounding factors such as, other concomitant medications and their side effects. One example may be SSA-induced steatorrhea, which is recorded in the currently available QOL questionnaires, as diarrhea, and in the setting of carcinoid syndrome, may be incorrectly labeled as worsening carcinoid syndrome with lack of benefit from treatment.20

Patients' perceptions and discrepancies with those of health care professionals

Patients' perceptions regarding the disease and its impact are important factors to consider. Various patient surveys explored different aspects of the diagnosis, treatment, information and daily life in patients with NETs. Delayed diagnosis and multiple doctor visits in the period of the onset of symptoms were identified as frequent concerns. In addition, patients describe difficulties in accessing centers with NET expertise as well as reliable information sources.22,23,91

An additional significant issue is how health care professionals perceive the disease/symptoms and what their definition of adequate symptom control and satisfactory QOL is. In a study by Goldstein et al patients, caregivers and health care professionals (doctors) participated in a survey and results reported a difference between the physician and patient perception of the disease and its impact on patient daily life and the patient experience.92 More than 50% of patients considered that it was hard to live with symptoms of carcinoid syndrome, whereas less than 25% of doctors thought this. A different perception was also reported in the frequency and severity of symptoms. Patients and caregivers reported higher severity of symptoms and increased frequency compared to health-care providers’ assessments. These results highlight the relevance of patient-reported outcomes and QOL measurement in clinical trials, and the importance of these being collected to provide insight regarding patient significant aspects of the disease being studied.

QOL in patients with NETs: currently available questionnaires and challenges

In general, QOL in patients with cancer is significantly affected.93,94 Such negative impact may be even more relevant in patients with NETs, especially in the population of patients with carcinoid syndrome (compared to nonfunctioning tumors). In a recent prospective observational study assessing QOL at baseline in patients starting treatment with SSAs, patients with functioning tumors had higher symptom severity in all symptoms/scales (derived from EORTC QLQ-30/QLQ-GI.NET21), with the exception of constipation and treatment-related symptoms, than patients with nonfunctioning NETs.20 In addition, patients with nonfunctioning tumors had higher baseline global health status and functioning scores reflecting a worse QOL in this second group of patients.20 Other studies have also shown similar findings.17–19

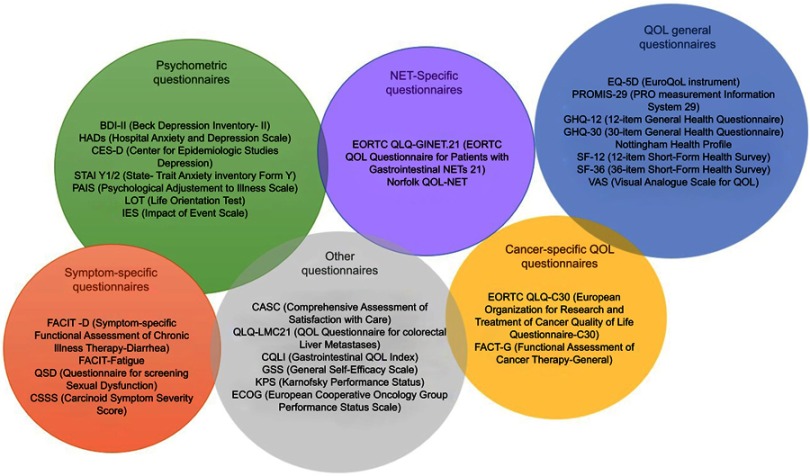

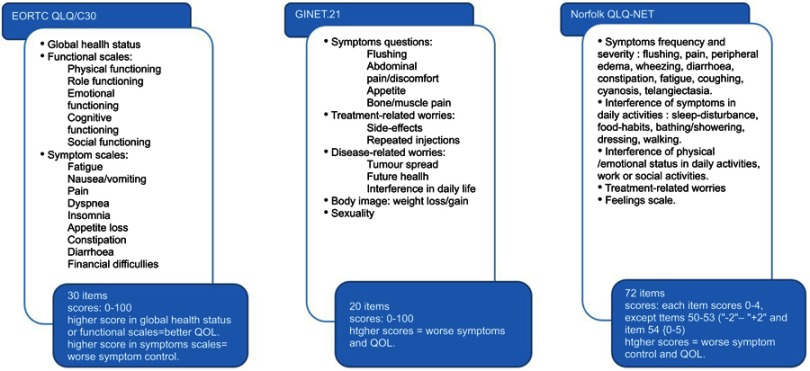

As mentioned above, QOL is already affected in patients with carcinoid syndrome, and taking into account the prolonged survival expected in this patient population, new therapies to improve QOL are required.95,96 Despite the increasing awareness of health-related QOL in drug evaluation, QOL is usually considered a secondary end point. Thus, studies are not appropriately powered for this assessment. In addition, different QOL assessment tools have been used in NET studies. Three systematic reviews have addressed this issue and identified up to 29 different questionnaires in NET research.95,97,98 A summary of these is provided in Figure 4 and the most relevant ones are discussed in this section.

Figure 4.

Symptomatic assessment tools. The figure collects the different tools employed to evaluated quality of life in studies and trials of neuroendocrine tumors.

Abbreviations: BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; HADs, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression; STAI Y1/2, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Fonn Y; PAIS, Psychological Adjustment to Illness Scale; LOT, Life Orientation Test; iES, Impact of Event Scale; FACIT-D, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Diarrhea; FACIT-Fatigue, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; QSD, Questionnaire for screening Sexual Dysfunction; CSSS, Carcinoid Symptom Severity Score; EORTC QLQ-GINET.21, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of life Questionnaire – Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors; Norfolk QLQ-NET, Norfolk Quality of life Questionnaire for Neuroendocrine Tumors; EQ-5D, Euro-Quality of Life instrument; PROMIS-29, PRO measurement information system; GHQ-12, 12-item General Health Questionnaire; GHQ-30, 30-item General Health Questionnaire; SF-12, 12-item Short-Form Health Survey. SF-36: 36-item Short-Fonn Health Survey; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale for Quality of Life; EORTC QLO-C30, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-C30; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General.

The EORTC QLQ-C30 is the most widely employed instrument. It was developed in 1997 based on a modification of the original EORTC QLQ-C36, and it is a generic tool for measurement of QOL in patients with cancer. It has been validated in the most common tumors.95,97,99,100 It comprises 30 items which are assessed on a 0–100 scale: five functional scales, nine symptom scales and a global health status scale. Higher scores in the global health scale and in the functional scales are associated with a better functioning level, whereas higher score in the other scales means worse symptomatic control (Figure 5). Despite the high level of evidence underlying this tool, patients with NETs encounter specific clinical issues which are not adequately assessed with this questionnaire.

Figure 5.

QOL assessment tools. This figure summarizes the main available tools for quality of life assessment in patients with NETs. The EORTC developed a questionnaire to assess health-related quality of life in patient with cancer. Items included and corresponding scores are detailed above.100 The GINET.21 is a supplement of the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire elaborated to improve symptoms evaluation in patients with NETs. It comprises the items presented above.102 The Norfolk QLQ-NET is a broad questionnaire, designed to assess health-related quality of life in patients with NETs only. The figure collected items included and scores.103Abbreviations: EORTC OLO/C30, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of life Questionnaire; GINET.21, Gastrointestinal Neuroendoaine Tumours; Norfolk OLO· NET, Norfolk Quality of life Questionnaire for Neuroendoaine Tumours.

A module to supplement the EORTC QLQ-C30 which focuses on NET symptoms was thus created, called the EORTC QLQ-GI.NET21.101 It captures disease-specific and treatment-related issues not adequately measured with the QLQ-C30 questionnaire. The EORTC QLQ-GI.NET21 is a 21-item self-reported questionnaire which comprises questions about disease symptoms (mainly endocrine and gastrointestinal), treatment side effects, body image, disease-related worries, social functioning, communication and sexuality (Figure 5). It provides an appropriate tool to assess NET-related QOL. Unfortunately, patients with functioning tumors such as glucagonomas, somatostatinomas and VIPomas were not represented in the development and validation samples of this questionnaire. Thus, this tool may not accurately capture QOL in these patients.95,99,101,102 The other limitation, as already mentioned, is that the combined EORTC QLQ-C30/QLQ-GI.NET21 only includes 1 question regarding diarrhea and 3 regarding other abdominal symptoms; thus, its relevance for applicability to carcinoid syndrome may be limited.

The Norfolk QLQ-NET was designed to specifically assess QOL in patients with NETs. It was developed in 2004 with the objective of assessing symptoms and their impact on physical and psychological functioning.103 It encompasses eleven symptoms and measures the frequency and severity of every one of them: flushing, rash, wheezing, coughing, cyanosis, telangiectasia, diarrhea/constipation, fatigue, joint/bone pain and other pain. It also measures dysfunction in daily activities, work capacity, family life and psychosocial activities (Figure 5).99,103

A direct comparison of these two scales (EORTC QLQ-C30/GINET21 and Norfolk QLQ-NET) was performed in a sample of 29 patients to assess the correlation between both tools.99 Results showed a strong correlation in the total scores and in all domains, except for the cardiovascular domain. The Norfolk QOL-NET questionnaire seemed to assess better flushing and respiratory and cardiovascular symptoms than the EORTC QLQ-C30/GINET21. Despite this, EORTC QLQ-C30/GINET21 remains the tool of preference for clinical trials, one of the reasons being that the Norfolk QLQ-NET is only available in the English language.95,99,103

Future directions

Ongoing studies are likely to provide data on long-term safety and efficacy from telotristat ethyl in patients with carcinoid syndrome. In addition, the utility of telotristat ethyl in the first-line setting will be explored concomitantly with SSAs in patients with high functioning carcinoid syndrome with diarrhea (so-called the TELEFIRST study).104

The role of telotristat ethyl for prevention/control of carcinoid heart disease and mesenteric fibrosis remains unknown, but may be clarified in the near future as we gain further experience with telotristat ethyl. In addition, the impact of telotristat ethyl in the management of other symptoms, such as flushing and its role for patients with less than 4 bowel movements per day remains unclear.

Mismatching information regarding the potential role of serotonin as a pro-proliferative molecule is available. Even though the effect of serotonin as a molecule involved in proliferation has been reported in small cell lung cancer, prostate cancer, bladder cancer,105 pancreatic cancer,106 biliary tract cancer107 and NETs,105,108–110 an antitumor effect has also been postulated in view of its vasoconstrictor effect.111 In view of preliminary results supporting the antitumor effect of telotristat ethyl in cholangiocarcinoma,107 an open-label phase 2 trial assessing the safety and efficacy of the combination of chemotherapy (cisplatin and gemcitabine) plus telotristat ethyl in first-line setting in a patient with locally advanced unresectable or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma is ongoing (NCT03790111). No evidence of antitumor effect of telotristat ethyl in NETs is available as yet.

Conclusions

Current treatments available provide adequate control of carcinoid syndrome–related symptoms for the majority, but not for all patients affected by this disease. Telotristat ethyl has been shown to significantly reduce the number of daily bowel movements in patients with a minimum of 4 bowel movements per day, despite adequate treatment with SSAs. The impact on QOL has resulted in an improvement in patient-reported diarrhea, and a significant number of patients report “adequate symptom relief”. Unfortunately, current tools for capturing patient-reported outcomes in NETs have limitations. Future studies will also aim to clarify the impact of telotristat ethyl on carcinoid heart disease and mesenteric fibrosis.

Acknowledgment

Dr Jorge Barriuso received funding from the ENETS Centre of Excellence Fellowship Grant Award. Dr Angela Lamarca was part-funded by The Christie Charity.

Disclosure

Dr Cristina Saavedra received travel and educational support from Ipsen, Roche, Amgen, MSD, Novartis. Dr Jorge Barriuso received travel and educational support from Ipsen, Pfizer, Novartis, AAA, Nanostring; research support from Pfizer; advisory honoraria from Nutricia. Dr Mairéad McNamara has served on advisory boards for Ipsen, SHIRE, Celgene and Sirtex and has received research support from NuCana BioMed Ltd, SHIRE, and Ipsen and served on speaker’s bureau for Pfizer, Ipsen and NuCana BioMed Ltd and received travel expenses from Bayer and travel and accommodation expenses from Ipsen. Prof. Juan W Valle reports grants, personal fees from Ipsen. Dr Angela Lamarca received travel and educational support from Ipsen, Pfizer, Bayer, AAA, SirtEx, Novartis and Delcath; speaker honoraria from Merck, Pfizer and Ipsen; advisory honoraria from EISAI and Nutricia and was also a member of the Knowledge Network and NETConnect Initiatives funded by Ipsen. The authors report no other conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

- 1.Klimstra David SYZ. Pathology, classification, and grading of neuroendocrine neoplasms arising in the digestive system In: Goldberg Richard MSDM, editor. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, et al. Trends in the incidence, prevalence, and survival outcomes in patients with neuroendocrine tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(10):1335–1342. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohike NAN. Mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms In: Lloyd RVOR, editor. WHO classification of tumours of endocrine organs. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2017:238. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vinik AI, Woltering EA, Warner RRP, et al. NANETS consensus guidelines for the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumor. Pancreas. 2010;39(6):713–734. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ebaffd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halperin DM, Shen C, Dasari A, et al. The frequency of carcinoid syndrome at neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis: a large population-based study using SEER-medicare data. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(4):525–534. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30072-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamarca A, Barriuso J, McNamara MG, Hubner RA, Valle JW. Telotristat ethyl: a new option for the management of carcinoid syndrome. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016;17(18):2487–2498. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2016.1129402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boutzios G, Kaltsas G. Clinical syndromes related to gastrointestinal neuroendocrine neoplasms. Front Horm Res. 2015;44:40–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Druce M, Rockall A, Grossman AB. Fibrosis and carcinoid syndrome: from causation to future therapy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5(5):276–283. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mota JM, Sousa LG, Riechelmann RP. Complications from carcinoid syndrome: review of the current evidence. Ecancermedicalscience. 2016;10:662. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2016.662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zacks J, Lavine R, Ratner L, Warner R. Telotristat etiprate appears to halt carcinoid heart disease. Neuroendocrinology. 103(suppl 1):90. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobson R, Burgess MI, Banks M, et al. The Association of a Panel of Biomarkers with the Presence and Severity of Carcinoid Heart Disease: a cross-sectional study Holvoet P, editor PLoS One. 2013; 8(9):e73679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moller JE, Connolly HM, Rubin J, Seward JB, Modesto K, Pellikka PA. Factors associated with progression of carcinoid heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(11):1005–1015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm020037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connolly HM, Crary JL, McGoon MD, et al. Valvular heart disease associated with fenfluramine-phentermine. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(9):581–588. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708283370901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fox DJ, Khattar RS. Carcinoid heart disease: presentation, diagnosis, and management. Heart. 2004;90(10):1224–1228. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.040329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dobson R, Burgess MI, Valle JW, et al. Serial surveillance of carcinoid heart disease: factors associated with echocardiographic progression and mortality. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(9):1703–1709. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plockinger U, Gustafsson B, Ivan D, Szpak W, Davar J. ENETS consensus guidelines for the standards of care in neuroendocrine tumors: echocardiography. Neuroendocrinology. 2009;90(2):190–193. doi: 10.1159/000225947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beaumont JL, Cella D, Phan AT, Choi S, Liu Z, Yao JC. Comparison of health-related quality of life in patients with neuroendocrine tumors with quality of life in the general US population. Pancreas. 2012;41(3):461–466. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182328045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haugland T, Vatn MH, Veenstra M, Wahl AK, Natvig GK. Health related quality of life in patients with neuroendocrine tumors compared with the general Norwegian population. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(6):719–726. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9478-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frojd C, Larsson G, Lampic C, von Essen L. Health related quality of life and psychosocial function among patients with carcinoid tumours. A longitudinal, prospective, and comparative study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;11(5):18. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamarca A, McCallum L, Nuttall C, et al. Somatostatin analogue-induced pancreatic exocrine insufficiency in patients with neuroendocrine tumors: results of a prospective observational study. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;12(7):723–731. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2018.1489232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearman TP, Beaumont JL, Cella D, Neary MP, Yao J. Health-related quality of life in patients with neuroendocrine tumors: an investigation of treatment type, disease status, and symptom burden. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(9):3695–3703. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3189-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh S, Granberg D, Wolin E, et al. Patient-reported burden of a neuroendocrine tumor (NET) diagnosis: results from the first global survey of patients with NETs. J Glob Oncol. 2017;3(1):43–53. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2015.002980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolin EM, Leyden J, Goldstein G, Kolarova T, Hollander R, Warner RRP. Patient-reported experience of diagnosis, management, and burden of neuroendocrine tumors: results from a large patient survey in the United States. Pancreas. 2017;46(5):639–647. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wymenga AN, de Vries EG, Leijsma MK, Kema IP, Kleibeuker JH. Effects of ondansetron on gastrointestinal symptoms in carcinoid syndrome. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(8):1293–1294. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(98)00009-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiesewetter B, Duan H, Lamm W, et al. Oral ondansetron offers effective antidiarrheal activity for carcinoid syndrome refractory to somatostatin analogs. Oncologist. 2019;24(2):255–258. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niederle B, Pape U-F, Costa F, et al. ENETS consensus guidelines update for neuroendocrine neoplasms of the Jejunum and Ileum. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103(2):125–138. doi: 10.1159/000443170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vinik AI, Wolin EM, Liyanage N, Gomez-Panzani E, GA F; ELECT Study Group. Evaluation of lanreotide Depot/autogel Efficacy And Safety As A Carcinoid Syndrome Treatment (ELECT): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(9):1068–1080. doi: 10.4158/1934-2403-22.12.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisher GA, Wolin EM, Liyanage N, et al. Lanreotide therapy in carcinoid syndrome: prospective analysis of patient-reported symptoms in patients responsive to prior octreotide therapy and patients naïve to somatostatin analogue therapy in the elect phase 3 study. Endocr Pract. 2018;24(3):243–255. doi: 10.4158/EP172000.OR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Modlin IM, Pavel M, Kidd M, Gustafsson BI. Review article: somatostatin analogues in the treatment of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumours. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(2):169–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ricci S, Antonuzzo A, Galli L, et al. Long-acting depot lanreotide in the treatment of patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors. Am J Clin Oncol. 2000;23(4):412–415. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200008000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kvols LK, Moertel CG, O’Connell MJ, Schutt AJ, Rubin J, Hahn RG. Treatment of the malignant carcinoid syndrome. Evaluation of a long-acting somatostatin analogue. N Engl J Med. 1986;315(11):663–666. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198609113151102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wymenga AN, Eriksson B, Salmela PI, et al. Efficacy and safety of prolonged-release lanreotide in patients with gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors and hormone-related symptoms. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(4):1111. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hofland LJ, Lamberts SW. The pathophysiological consequences of somatostatin receptor internalization and resistance. Endocr Rev. 2003;24(1):28–47. doi: 10.1210/er.2000-0001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carmona-Bayonas A, Jimenez-Fonseca P, Custodio A, et al. Optimizing somatostatin analog use in well or moderately differentiated gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Curr Oncol Rep. 2017;19(11):72. doi: 10.1007/s11912-017-0633-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Molina-Cerrillo J, Alonso-Gordoa T, Martinez-Saez O, Grande E. Inhibition of peripheral synthesis of serotonin as a new target in neuroendocrine tumors. Oncologist. 2016;21(6):701–707. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cordoba-Chacon J, Gahete MD, Duran-Prado M, et al. Identification and characterization of new functional truncated variants of somatostatin receptor subtype 5 in rodents. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67(7):1147–1163. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0401-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rinke A, Muller HH, Schade-Brittinger C, et al. Placebo-controlled, double-blind, prospective, randomized study on the effect of octreotide LAR in the control of tumor growth in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine midgut tumors: a report from the PROMID Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(28):4656–4663. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.8510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caplin ME, Pavel M, Cwikla JB, et al. Lanreotide in metastatic enteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(3):224–233. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strosberg JR, Benson AB, Huynh L, et al. Clinical benefits of above-standard dose of octreotide LAR in patients with neuroendocrine tumors for control of carcinoid syndrome symptoms: a multicenter retrospective chart review study. Oncologist. 2014;19(9):930–936. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kvols LK, Oberg KE, O’Dorisio TM, et al. Pasireotide (SOM230) shows efficacy and tolerability in the treatment of patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors refractory or resistant to octreotide LAR: results from a phase II study. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2012;19(5):657–666. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolin EM, Jarzab B, Eriksson B, et al. Phase III study of pasireotide long-acting release in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors and carcinoid symptoms refractory to available somatostatin analogues. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:5075–5086. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S84177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferolla P, Brizzi MP, Meyer T, et al. Efficacy and safety of long-acting pasireotide or everolimus alone or in combination in patients with advanced carcinoids of the lung and thymus (LUNA): an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(12):1652–1664. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30072-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kulke MH, Ruszniewski P, Van Cutsem E, et al. A randomized, open-label, phase 2 study of everolimus in combination with pasireotide LAR or everolimus alone in advanced, well-differentiated, progressive pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: COOPERATE-2 trial. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(6):1309–1315. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oberg K, Funa K, Alm G. Effects of leukocyte interferon on clinical symptoms and hormone levels in patients with mid-gut carcinoid tumors and carcinoid syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1983;309(3):129–133. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198307213090301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith DB, Scarffe JH, Wagstaff J, Johnston RJ. Phase II trial of rDNA alfa 2b interferon in patients with malignant carcinoid tumor. Cancer Treat Rep. 1987;71(12):1265–1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moertel CG, Rubin J, Kvols LK. Therapy of metastatic carcinoid tumor and the malignant carcinoid syndrome with recombinant leukocyte A interferon. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7(7):865–868. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.7.865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valimaki M, Jarvinen H, Salmela P, Sane T, Sjoblom SM, Pelkonen R. Is the treatment of metastatic carcinoid tumor with interferon not as successful as suggested? Cancer. 1991;67(3):547–549. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Veenhof CH, de Wit R, Taal BG, et al. A dose-escalation study of recombinant interferon-alpha in patients with a metastatic carcinoid tumour. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28(1):75–78. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(92)90389-J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Janson ET, Oberg K. Long-term management of the carcinoid syndrome. Treatment with octreotide alone and in combination with alpha-interferon. Acta Oncol. 1993;32(2):225–229. doi: 10.3109/02841869309083916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Di Bartolomeo M, Bajetta E, Zilembo N, et al. Treatment of carcinoid syndrome with recombinant interferon alpha-2a. Acta Oncol. 1993;32(2):235–238. doi: 10.3109/02841869309083918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yao JC, Guthrie KA, Moran C, et al. Phase III prospective randomized comparison trial of depot octreotide plus interferon alfa-2b versus depot octreotide plus bevacizumab in patients with advanced carcinoid tumors: SWOG S0518. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15):1695–1703. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.4072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pavel ME, Hainsworth JD, Baudin E, et al. Everolimus plus octreotide long-acting repeatable for the treatment of advanced neuroendocrine tumours associated with carcinoid syndrome (RADIANT-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet (London, England). 2011;378(9808):2005–2012. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60984-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yao JC, Shah MH, Ito T, et al. Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):514–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yao JC, Fazio N, Singh S, et al. Everolimus for the treatment of advanced, non-functional neuroendocrine tumours of the lung or gastrointestinal tract (RADIANT-4): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet (London, England). 2016;387(10022):968–977. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00817-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pavel M, Unger N, Borbath I, et al. Safety and QOL in patients with advanced NET in a phase 3b expanded access study of everolimus. Target Oncol. 2016;11(5):667–675. doi: 10.1007/s11523-016-0440-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bainbridge HE, Larbi E, Middleton G. Symptomatic control of neuroendocrine tumours with everolimus. Horm Cancer. 2015;6(5–6):254–259. doi: 10.1007/s12672-015-0233-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Raymond E, Dahan L, Raoul JL, et al. Sunitinib malate for the treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):501–513. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moertel CG, Lefkopoulo M, Lipsitz S, Hahn RG, Klaassen D. Streptozocin-doxorubicin, streptozocin-fluorouracil or chlorozotocin in the treatment of advanced islet-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(8):519–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202203260804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kouvaraki MA, Ajani JA, Hoff P, et al. Fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and streptozocin in the treatment of patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic endocrine carcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(23):4762–4771. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Strosberg JR, Fine RL, Choi J, et al. First-line chemotherapy with capecitabine and temozolomide in patients with metastatic pancreatic endocrine carcinomas. Cancer. 2011;117(2):268–275. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meyer T, Qian W, Caplin ME, et al. Capecitabine and streptozocin ± cisplatin in advanced gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(5):902–911. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fine RL, Gulati AP, Krantz BA, et al. Capecitabine and temozolomide (CAPTEM) for metastatic, well-differentiated neuroendocrine cancers: the Pancreas Center at Columbia University experience. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71(3):663–670. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-2055-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lamarca A, Elliott E, Barriuso J, et al. Chemotherapy for advanced non-pancreatic well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumours of the gastrointestinal tract, a systematic review and meta-analysis: a lost cause? Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;44:26–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Strosberg J, El-Haddad G, Wolin E, et al. Phase 3 trial of (177)lu-dotatate for midgut neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(2):125–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Strosberg J, Wolin E, Chasen B, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with progressive midgut neuroendocrine tumors treated with (177)Lu-dotatate in the phase III NETTER-1 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(25):2578–2584. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.5865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matthes S, Bader M. Peripheral serotonin synthesis as a new drug target. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2018;39(6):560–572. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fidalgo S, Ivanov DK, Wood SH. Serotonin: from top to bottom. Biogerontology. 2013;14(1):21–45. doi: 10.1007/s10522-012-9406-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Walther DJ, Peter JU, Bashammakh S, et al. Synthesis of serotonin by a second tryptophan hydroxylase isoform. Science (New York, NY). 2003;299(5603):76. doi: 10.1126/science.1078197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Adaway J, Dobson R, Walsh J, et al. Serum 5HIAA: a better biomarker than urine for detecting and monitoring neuroendocrine tumours? BioScientifica. 2014. [cited January 16, 2019] Available from: https://www.endocrine-abstracts.org/ea/0034/ea0034p45. Accessed June 24, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 70.European Medicines Agency. Xermelo [Internet]. 2017. [cited September28, 2018]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/assessment-report/xermelo-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf. Accessed June24, 2019.

- 71.Margolis KG, Stevanovic K, Li Z, et al. Pharmacological reduction of mucosal but not neuronal serotonin opposes inflammation in mouse intestine. Gut. 2014;63(6):928–937. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Engelman K, Lovenberg W, Sjoerdsma A. Inhibition of serotonin synthesis by para-chlorophenylalanine in patients with the carcinoid syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1967;277(21):1103–1108. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196711232772101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.A Phase 1, Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Ascending Single Dose Study to Determine the Safety and Tolerability of Orally Administered LX1606 in Healthy Human Subjects. The Woodlands, TX: Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lapuerta P, Zambrowicz B, Fleming D, Wheeler D, Arthur S. Telotristat etiprate, a novel inhibitor of serotonin synthesis for the treatment of carcinoid syndrome. Clin Invest (Lond). 2015;5:447–456. doi: 10.4155/cli.15.10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pavel M, Horsch D, Caplin M, et al. Telotristat etiprate for carcinoid syndrome: a single-arm, multicenter trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(4):1511–1519. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kulke MH, O’Dorisio T, Phan A, et al. Telotristat etiprate, a novel serotonin synthesis inhibitor, in patients with carcinoid syndrome and diarrhea not adequately controlled by octreotide. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21(5):705–714. doi: 10.1530/ERC-14-0173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kulke MH, Horsch D, Caplin ME, et al. Telotristat ethyl, a tryptophan hydroxylase inhibitor for the treatment of carcinoid syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(1):14–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.2780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pavel M, Gross DJ, Benavent M, et al. Telotristat ethyl in carcinoid syndrome: safety and efficacy in the TELECAST phase 3 trial. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2018;25(3):309–322. doi: 10.1530/ERC-17-0455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hörsch D, Rocio Garcia-Carbonero JW, Valle PP, et al. Efficacy and safety of telotristat ethyl in combination with lanreotide in patients with a neuroendocrine tumour and carcinoid syndrome diarrhoea: meta-analysis of phase 3 double-blind placebo-controlled TELESTAR and TELECAST studies. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(suppl_8):viii467–78. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx807 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Markham A. Telotristat ethyl: first global approval. Drugs. 2017;77(7):793–798. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0731-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oates JA, Melmon K, Sjoerdsma A, Gillespie L, Mason DT. Release of a kinin peptide in the carcinoid syndrome. Lancet. 1964;1(7332):514–517. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(64)92907-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Norheim I, Theodorsson-Norheim E, Brodin E, Oberg K. Tachykinins in carcinoid tumors: their use as a tumor marker and possible role in the carcinoid flush. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;63(3):605–612. doi: 10.1210/jcem-63-3-605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cunningham JL, Janson ET, Agarwal S, Grimelius L, Stridsberg M. Tachykinins in endocrine tumors and the carcinoid syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;159(3):275–282. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]