Abstract

Influenza world-wide causes significant morbidity and mortality annually, and more severe pandemics when novel strains evolve to which humans are immunologically naïve. Because of the high viral mutation rate, new vaccines must be generated based on the prevalence of circulating strains every year. New approaches to induce more broadly protective immunity are urgently needed. Previous research has demonstrated that influenza-specific T cells can provide broadly heterotypic protective immunity in both mice and humans, supporting the rationale for developing a T cell-targeted universal influenza vaccine. We used state-of-the art immunoinformatic tools to identify putative pan-HLA-DR and HLA-A2 supertype-restricted T cell epitopes highly conserved among >50 widely diverse influenza A strains (representing hemagglutinin types 1, 2, 3, 5, 7 and 9). We found influenza peptides that are highly conserved across influenza subtypes that were also predicted to be class I epitopes restricted by HLA-A2; these peptides were found to be immunoreactive in HLA-A2 positive but not HLA-A2 negative individuals. Class II-restricted T cell epitopes that were highly conserved across influenza subtypes were identified. Human CD4+ T cells were reactive with these conserved CD4 epitopes, and epitope expanded T cells were responsive to both H1N1 and H3N2 viruses. Dendritic cell vaccines pulsed with conserved epitopes and DNA vaccines encoding these epitopes were developed and tested in HLA transgenic mice. These vaccines were highly immunogenic, and more importantly, vaccine-induced immunity was protective against both H1N1 and H3N2 influenza challenges. These results demonstrate proof-of-principle that conserved T cell epitopes expressed by widely diverse influenza strains can induce broadly protective, heterotypic influenza immunity, providing strong support for further development of universally relevant multi-epitope T cell-targeting influenza vaccines.

Keywords: influenza vaccines, cellular immunity, bioinformatics, pandemics

Introduction

Each flu season, 5 to 10% of adults and 20 to 30% of children are infected with circulating flu strains, causing an estimated 250,000 – 500,000 deaths around the world [1]. The more dramatic and abrupt changes in viral composition lead to pandemics and more severe disease because human populations have limited cross-protective immunity to the new reassortments[2]. The 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, resulting from a newly emerged avian-like influenza strain, infected 20-40% of the world’s population and resulted in 50-100 million deaths[3]. Other pandemics occurred in 1957 (H2N2), 1968 (H3N2) and 2009 (H1N1),which infected >60 million people in the US alone[4]. Currently, avian H5 and H7 strains represent major public health threats that could lead to unprecedented morbidity and mortality.

Licensed influenza vaccines currently focus on inducing neutralizing antibodies against seasonal viruses. A major limitation of this approach is the focus on strain-specific immunity that rarely induces optimal immunity against drifted strains that emerge from one flu season to the next. Even during a single flu season, viral drift can occur, which may make a newly generated seasonal influenza vaccine ineffective against the new strains. This occurred in 2014-2015 when most H3N2 isolates were antigenically different from the vaccine strain.

T cells have the ability to provide broad protection against diverse influenza strains in mice [5-7] and in humans [8-12]. However, to date, no influenza vaccines are available for inducing influenza-specific T cell-mediated heterotypic immunity in humans, despite the potential for this strategy to greatly improve influenza vaccine-induced immunity. Integration of the fields of bioinformatics and vaccinology has made possible the development of protective T cell-targeted multi-epitope vaccines. For example, immunoinformatic identification of conserved T cell epitopes in variola and vaccinia genomes has been utilized to generate an epitope-based vaccine with demonstrated efficacy against poxviral lethal challenges in mice[13]. Additional research has demonstrated that vaccines inducing responses against even a single T cell epitope can be sufficient to induce potent protection against a virulent pathogen challenge[14]. T cell-targeted influenza and tularemia vaccines also have been shown to induce protective immunity against relevant challenges[15, 16]. In the current work, we utilize state-of-the art immunoinformatic tools to identify promiscuous CD4+ T cell epitopes and HLA-A2-restricted CD8+ T cell epitopes highly conserved in widely diverse influenza A strains. These epitopes were also carefully screened for cross-conservation against the human genome, and potential regulatory T cell epitopes were removed from the list [17, 18]. Most importantly, we show that these identified universally relevant T cell epitopes can induce potent protection in HLA transgenic mice against both H3N2 and H1N1 viral challenges.

Methods.

Mice and Viruses:

HLA-DR1 transgenic mice, expressing a chimeric mouse:human class II element (I-Ed/HLA-DR1), crossed onto a MHC-II deficient B6 background, were obtained from E. Rosloniec (University of Tennessee Health Science Center) [19]. HLA-A2 HHD mice, expressing a chimeric H-2Db/HLA-A2.1 molecule and deficient in murine MHC-I expression, and HLA-A2/DR1 dual transgenic mice, deficient in endogenous murine MHC-I and II, expressing full-length HLA-DR1 and chimeric H-2Db/HLA-A2.1 were obtained under MTA from the Institut Pasteur [20, 21]. All strains were bred at Saint Louis University under germ-limiting conditions. Male and female mice, aged 6-12 weeks, were utilized as described in each experiment. Mouse-adapted influenza strains A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1) and A/Victoria/3/75 (H3N2) were provided by Andrew Pekosz (Johns Hopkins University) and Donald Smee (Utah State University), respectively, and propagated in MDCK cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) with DMEM supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, L-glutamine, 0.5% bovine serum albumin, and trypsin TPCK (1μmg/ml). Viral stocks were stored frozen (−80°C) and were quantified after thawing using 50% tissue culture infectious dose assays (TCID50). Briefly, titrations of sample were added to 96 well tissue culture plates previously seeded with MDCK cells to >80% confluence in the media above. After 3 days of culture, cells were fixed and stained with formalin and crystal violet, respectively, and cytopathic effect (CPE) observed microscopically. Human influenza strains H3N2 A/California/07/04 and H1N1 A/Puerto Rico/8/34 were used in vitro for studies with human PBMC and CD4+ T cells as described below.

Immunoinformatics:

Strains causing major pandemics (such as the 1918 pandemic strain) and epidemics over the last 40+ years, as well as more novel strains (e.g.- H5 and H7 strains) shown to be highly virulent in humans were identified. M1, M2, and NP protein sequences from selected influenza A virus strains were collected from the Influenza Virus Resource and the GISAID EpiFlu Database (see Table 1 for list of 53 influenza strains used for immunoinformatic analyses, and Supplemental Table 1 for accession numbers and reference laboratories)[22-24]. The Conservatrix algorithm, which searches for identically matched segments and tracks the number of strains in which regions (9-mers) are conserved, was used to identify conserved 9-mer sequences in M1, M2, and NP sequences from the 53 input strains[25]. Potential immunogenicity of parsed 9-mers was computationally assessed by epitope mapping using the EpiMatrix algorithm.

Table 1.

Influenza A strains utilized in immunoinformatic prediction strategy.

| Influenza Strain Name | Subtype | Influenza Strain Name | Subtype |

|---|---|---|---|

| A/Brevig Mission/1/1918 | H1N1 | A/Shangdong/9/1993 | H3N2 |

| A/Puerto Rico/8/34 | H1N1 | A/Johnannesburg/33/1994 | H3N2 |

| A/WSN/1933 | H1N1 | A/Nanchang/933/1995 | H3N2 |

| A/NewJersey/76 | H1N1 | A/Wuhan/359/1995 | H3N2 |

| A/USSR/90/1977 | H1N1 | A/Sydney/5/1997 | H3N2 |

| A/Brazil/11/1978 | H1N1 | A/Moscow/10/1999 | H3N2 |

| A/Chile/1/1983 | H1N1 | A/Fujian/411/2002 | H3N2 |

| A/Singapore/6/1986 | H1N1 | A/California/7/2004 | H3N2 |

| A/Beijing/262/1995 | H1N1 | A/Wisconsin/67/2005 | H3N2 |

| A/New Caledonia/20/1999 | H1N1 | A/Brisbane/10/2007 | H3N2 |

| A/Brisbane/59/2007 | H1N1 | A/Perth/16/2009 | H3N2 |

| A/California/7/2009 | H1N1 | A/Victoria/361/2011 | H3N2 |

| A/Singapore/1/57 | H2N2 | A/Texas/50/2012 | H3N2 |

| A/Japan/170/62 | H2N2 | A/goose/Guangdong/1/96 | H5N1 |

| A/Taiwan/64 | H2N2 | A/Hong Kong/156/97 | H5N1 |

| A/Hong Kong/1/68 | H3N2 | A/Vietnam/1203/2004 | H5N1 |

| A/Udorn/72 | H3N2 | A/Indonesia/5/2005 | H5N1 |

| A/England/42/72 | H3N2 | A/turkey/turkey/1/2005 | H5N1 |

| A/Port Chalmers/1/1973 | H3N2 | A/Cambodia/R0404050/2007 | H5N1 |

| A/Victoria/3/1975 | H3N2 | A/Guizhou/1/2013 | H5N1 |

| A/Texas/1/1977 | H3N2 | A/New York/107/2003 | H7N2 |

| A/Bangkok/1/1979 | H3N2 | A/mallard/Netherlands/12/2000 | H7N3 |

| A/Philippines/2/1982 | H3N2 | A/Canada/504/04 | H7N3 |

| A/Leningrad/360/1986 | H3N2 | A/Mexico/InDRE7218/2012 | H7N3 |

| A/Sichuan/2/1987 | H3N2 | A/Hangzhou/1/2013 | H7N9 |

| A/Shanghai/11/1987 | H3N2 | A/Hong Kong/1073/1999 | H9N2 |

| A/Beijing/353/1989 | H3N2 |

Promiscuous epitopes were identified for eight common human MHC II alleles (DRB1*0101, DRB1*0301, DRB1*0401, DRB1*0701, DRB1*0801, DRB1*1101, DRB1*1301 and DRB1*1501) which are cumulatively expressed by >95% of the human population. 9-mer sequences scoring above 1.64 on the EpiMatrix “Z” scale, typically the top 5% of scores, are likely MHC ligands and considered potential epitope “hits”. The EpiMatrix score for all 8 Class II alleles served as the starting point for constructing immunogenic consensus sequences (ICS). ICS were constructed using EpiAssembler, an algorithm that maximizes epitope density in a 20-25 amino acid long sequence across strains by assembling overlapping 9-mers that are both ≥70% conserved and predicted to be immunogenic. Design of vaccine immunogens with increased epitope density makes it possible for presentation of epitopes to T cells in the context of more than one HLA allele, thereby more broadly covering the HLA diverse human population. Furthermore, it enables increased coverage of influenza strains. Epitopes were ranked based on influenza strain coverage (all >70%) and EpiMatrix scores for DRB*0101 (representing the HLA-DR1 supertype). To minimize risks of inducing unanticipated immune responses (Treg cells, autoimmunity), ICS epitopes sharing significant homology with human sequences were triaged using JanusMatrix, an advanced algorithm that identifies MHC binding peptides predicted to present structural patterns to TCR similar to “self” peptides [17, 26-29].

A similar immunoinformatic approach was employed to identify highly conserved influenza A HLA-A2-restricted 9mer T cell epitopes capable of inducing robust heterotypic protective immunity. Using the suite of immunoinformatic tools described above (Conservatrix, EpiMatrix), M1, M2, and NP sequences from the 53 diverse influenza A strains (H1/H2/H3/H5/H7/H9) shown in Table 1 were analyzed for both conservation and predicted binding to HLA*0201, representative of the HLA-A2 supertype expressed by ~50% of humans. BlastP analyses were performed to identify (and remove) potential human homologues.

Vaccines:

Peptide-pulsed dendritic cell (DC) vaccines were prepared as described previously[30]. Briefly, 5×106 B16-Flt3L cells were injected i.p. into donor mice, and 2 weeks later DC were matured in vivo by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) injection (2μg i.v.). Splenic DC isolated 14-16 hours later using Miltenyi CD11c+ microbeads were pulsed for 1-2 hours at 37°C with various peptide pools (2.5μg/ml each peptide). DC vaccine recipient mice were immunized using 0.5-1.0×106 peptide-pulsed DC delivered i.v. In experiments involving HLA-A2 transgenic mice, DC were additionally pulsed with pan-restricted PADRE and OVA323-339 peptides to induce CD4+ T cell helper responses to facilitate induction of CD8+ T cell responses.

Conserved influenza promiscuous ICS or HLA-A2 epitopes were arranged into synthetic minigenes for DNA vaccine preparation using VaxCAD, an algorithm that optimizes the order of epitopes in a vaccine construct to minimize the creation and introduction of non-specific epitopes at influenza epitope junctions[31]. The protein sequences were next reverse-engineered for high expression in mice/humans (i.e.- codon harmonized) and cloned into commercially available antibiotic-free, sucrose-selectable eukaryotic-expression plasmids (Nature Technology Corporation). Promiscuous ICS were cloned in frame with the human tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) leader sequence to target the protein for secretion. Predicted HLA-A2 epitopes were cloned with a ubiquitin leader optimized for intracellular protein degradation. An additional construct was engineered to express promiscuous CD4+ T cell epitopes PADRE and OVA323-339 using the TPA construct described above. Endotoxin-free plasmid DNAs were prepared using QIAGEN EndoFree Plasmid Giga kits, and suspended in PBS for immunization studies. Mice were anesthetized by i.p. injection of ketamine (60 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg) prior to i.m. delivery of 100μg of each DNA into the tibialis anterior muscle beds (50μg/limb).

Murine T cell analyses:

Conserved ICS/epitope-specific T cell responses were studied by IFN-γ ELISPOT as described previously[30]. T cell subsets were prepared using Miltenyi CD4 and CD8 microbeads according to the manufacturer’s recommendations and suspended in complete media (RPMI 1640 with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 2mM L-glutamine, non-essential amino acids, 1mM sodium pyruvate, 50U/ml penicillin, 50μg/ml streptomycin, 5mM HEPES, and 55μM β-mercaptoethanol). For study of murine MHC class II responses, splenic CD4+ T cells were added to IFN-γ ELISPOT plates (1×105/well) with syngeneic naïve CD4/CD8 T cell-depleted splenocytes (3×105/well) and individual peptides or peptide pools (10 μg/ml each peptide). In other cases, total splenocytes were studied using 4×105 total cells/well. Conserved influenza-specific HLA-A2-restricted CD8+ T cell responses were studied similarly using 1×105 CD8+ T cells, 3×105 total naïve splenocytes as APC, and 2.5 – 5.0 μg/ml of each peptide. After assay development, ELISPOT well images were captured, spots enumerated using a C.T.L. ImmunoSpot Reader and software, and results expressed as spot forming cells (SFC) per million cells. A positive response was defined as a value greater than the mean + 2 standard deviations of negative control T cell responses to all individual stimulating peptides.

Human T cell immunogenicity assays:

To determine human T cell immunogenicity of influenza ICS, 2×106 thawed human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were cultured for 1 week with DMSO (control), the FluICS peptide pool (2 μg/ml each peptide), or live influenza A viruses (H3N2 and H1N1; 0.02 MOI) in RPMI supplemented with 10% human AB serum (Sigma), 2mM L-glutamine and penicillin/streptomycin (50 U/ml and 50 μg/ml, respectively). Expanded CD4+ T cells were then isolated (Miltenyi microbeads) and stimulated in human IFN-γ ELISPOT assays with fresh autologous T cell-depleted APCs pulsed with DMSO (control), FluICS peptides (2μg/ml each), H3N2 A/California/07/04 (0.5 MOI), or H1N1 A/PR/8/34 (0.5 MOI) (1-4×104 CD4+ T cells and 1×105 APC per well). In other experiments, thawed PBMC were directly stimulated in overnight IFN-γ ELISPOT assays with DMSO or the FluICS peptide pool. Human IFN-γ ELISPOT assays were conducted as recommended by the manufacturer (BD Biosciences) and data analyzed using a C.T.L. ImmunoSpot system. For determination of human T cell reactivity with class I influenza epitopes, HLA-A2 expression in each volunteer was determined by flow cytometry of PBMC (anti-HLA-A2 clone BB7.2). Thawed PBMC were stimulated in 96 well “U” bottom plates (2.5×105 cells/well) with individual peptide (10 μg/ml) in 0.2 ml X-Vivo15 media (Lonza) supplemented with L-glutamine and penicillin/streptomycin. IL-2 was provided on days 0, 3, 7 and 10. On day 13, cells were washed once to remove residual peptide, and the following day cells were washed again, resuspended in complete X-Vivo15 media, and stimulated in overnight IFN-γ ELISPOT assays (50,000 cells/well) with 10 μg/ml peptide. Assays were performed and analyzed as described above.

Influenza challenge and assessment of protection:

Influenza virus preparations were diluted in DMEM and delivered intranasally, at 20 μl doses split between nares, to mice under ketamine/xylazine-induced anesthesia. Doses for each challenge experiment are described in the Figure Legends. Some groups of mice were weighed daily and/or studied for survival, and others euthanized 3-4 days post-challenge for assessment of pulmonary influenza burden. Briefly, lungs were homogenized in 1 ml of DMEM using a Tissue Tearor hand homogenizer (Biospec) and homogenates stored at −80°C prior to serial dilution and virus quantitation using TCID50 assays as described above. HLA-DR1 transgenic mice were extremely susceptible to the PR8 H1N1 strain, and we were unable to identify a low enough challenge dose that allowed assessment of survival. Instead we used lung viral titers as our primary protection endpoint in HLA-DR1 transgenic mice challenged with H3N2 which is significantly less virulent than H1N1 in our murine model.

Results

Immunoinformatic identification of putative pan-DR and HLA-A2-restricted conserved influenza T cell epitopes.

The ultimate goal for influenza vaccinologists is to develop vaccines that could protect all humans against all future influenza epidemics and pandemics[32]. To that end, we first sought to identify highly conserved sequences from diverse influenza strains. Not all influenza proteins are equally conserved within a specific influenza A subtype and among different subtypes. For example, neuraminidase and hemagglutinin proteins contain conserved regions, but overall these proteins undergo high rates of mutation. Matrix (M1, M2) and nucleoprotein (NP) are all highly conserved proteins in influenza A subtypes and have been shown to be immunogenic and targets of protective T cells in inbred mouse strains. We therefore focused our efforts on identifying T cell targets relevant for broad human protection against seasonal and potential pandemic strains using conserved M1, M2, and NP sequence. We identified strains that have been associated with major pandemics/epidemics, are used commonly in influenza laboratories, have crossed the species barrier (evidence of human infection with known swine or avian viruses), and those that are listed by the WHO as possible future vaccine strains. Fifty-three influenza A strains were identified for which complete sequences of the M1, M2, and NP proteins were available for subsequent study. The strains were diverse, with sequences collected from H1N1, H2N2, H3N2, H5N1, H7N2, H7N3, H7N7, and H7N9 subtypes (Table 1).

Next, protein sequences were analyzed for conservation and epitope composition. Sequences parsed into 9-mer frames allowed identification of 727 unique M1 9-mers, 573 unique M2 9-mers, and 2,021 unique NP 9-mers from the 53 influenza strains. Matrix-based epitope predictions for 8 common human class II alleles (cumulatively expressed by >95% of humans) were performed to identify conserved sequences with predicted binding to multiple alleles. Core conserved 9-mers were then extended in both directions to include additional epitopes, resulting in longer and more dense epitope-rich promiscuous immunogenic consensus sequences (ICS) ICS were ranked based on influenza strain coverage (all >70%) and EpiMatrix scores for DRB*0101. Thirty ICS selected for further analyses were highly conserved, with an average 91.7% conservation among the diverse influenza strains, and contained multiple predicted DR-restricted epitopes, with an average 7.1 epitopes per ICS. These sequences were examined further to identify MHC binding peptides predicted to present sequence patterns to TCR similar to “self” peptides [29]. Five of the top 30 predicted ICS were found to share significant sequence homology with human peptides and were excluded from further study. The resulting 25 high-priority conserved influenza ICS (Table 2) were produced as synthetic peptides for immunogenicity evaluation and arranged into a synthetic minigene for DNA vaccine preparation using the EpiVax VaxCAD algorithm[31].

Table 2.

Conserved influenza A class II-predicted immunogenic consensus sequences.

| Peptide # | Protein - Starting AA |

Consensus Sequence | EpiMatrix Hits |

EpiBars? (#) | Conservation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flu.ICS-2 | M1-58 | GMLGFVFTLTVPSERGLQ | 14 | Yes (2) | 1 |

| Flu.ICS-4 | M1-176 | ENRMVLASTTAKAMEQV | 7 | Yes (1) | 1 |

| Flu.ICS-6 | M1-76 | RRRFVQNALNGNGDPN | 7 | Yes (1) | 1 |

| Flu.ICS-7 | M1-129 | GLIYNRMGAVTTEAA | 6 | Yes (1) | 0.72 |

| Flu.ICS-8 | M1-234 | LENLQAYQKRMGVQMQRF | 6 | Yes (1) | 0.98 |

| Flu.ICS-9 | M1-17 | SGPLKAEIAQRLEDV | 4 | Yes (1) | 0.91 |

| Flu.ICS-10 | M1-170 | NPLIRHENRMVLAST | 3 | No | 0.92 |

| Flu.ICS-11 | M1-135 | MGAVTTEVAFGLVCA | 1 | No | 0.77 |

| Flu.ICS-12 | M1-125 | ASCMGLIYNRMGAVT | 3 | No | 0.98 |

| Flu.ICS-14 | NP-409 | QPAFSVQRNLPFERVTI | 11 | Yes (1) | 1 |

| Flu.ICS-15 | NP-113 | KDEIRRIWRQANNGEDAT | 9 | No | 1 |

| Flu.ICS-16 | NP-51 | DNEGRLIQNSLTIERMVL | 9 | No | 0.72 |

| Flu.ICS-17 | NP-133 | LTHMMIWHSNLNDTTYQR | 8 | Yes (1) | 1 |

| Flu.ICS-18 | NP-216 | RTAYERMCNILKGKF | 6 | Yes (1) | 1 |

| Flu.ICS-19 | NP-261 | RSALILRGSVAHKSCLP | 8 | Yes (1) | 1 |

| Flu.ICS-20 | NP-145 | DATYQRTRALVRSGM | 6 | Yes (1) | 1 |

| Flu.ICS-21 | NP-36 | IGRFYIQMCTELKLNDY | 7 | Yes (1) | 0.98 |

| Flu.ICS-22 | NP-188 | TMVMELIRMIKRGINDRN | 13 | Yes (2) | 0.75 |

| Flu.ICS-23 | NP-381 | LRSMYWAIRTRSGGNTN | 7 | Yes (1) | 1 |

| Flu.ICS-24 | NP-301 | IDPFRLLQNSQVYSLIRP | 14 | Yes (2) | 0.75 |

| Flu.ICS-25 | NP-310 | SQVYSLIRPNENPAHKSQ | 9 | Yes (1) | 0.96 |

| Flu.ICS-26 | NP-204 | RNFWRGENGRKTRSA | 4 | Yes (1) | 0.72 |

| Flu.ICS-28 | NP-75 | RNKYLEEHPSAGKDP | 2 | No | 0.98 |

| Flu.ICS-29 | NP-161 | PRMCSLMQGSTLPRR | 1 | No | 1 |

| Flu.ICS-30 | NP-220 | ERMCNILKGKFQTAA | 1 | No | 1 |

EpiMatrix ‘hit’ defined as a predicted binding Z-score of ≥1.64 to a single class II HLA.

‘EpiBars’ are defined frames for which predicted binding is observed for ≥4 DR alleles.

Similarly, parsed 9-mers were scored for predicted binding to MHC class I alleles sharing the most common HLA-A2 supertype. Sequences with EpiMatrix HLA-A2 predicted binding scores of ≥1.64 representing the top 5% of predicted binders, ≥70% conservation among the 53 input strains, and without significant human homology were selected for further study (Table 3). These influenza HLA-A2-restricted sequences were highly conserved (present in 88.3% of the highly diverse influenza strains listed in Table 1).

Table 3.

Conserved putative influenza A HLA-A2-restricted epitopes.

| A2 Peptide | Protein - starting AA |

Sequence | Conservation | A0201 Z-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2-1 | M1-58 | GILGFVFTL | 0.98 | 3.09 |

| A2-2 | M1-3 | LLTEVETYV | 0.98 | 2.71 |

| A2-3 | M1-123 | ALASCMGLI | 0.98 | 2.42 |

| A2-4 | M1-51 | ILSPLTKGI | 0.98 | 2.36 |

| A2-5 | M1-59 | ILGFVFTLT | 0.98 | 2.29 |

| A2-6 | M1-130 | LIYNRMGAV | 0.72 | 2.27 |

| A2-7 | M1-180 | VLASTTAKA | 1 | 1.96 |

| A2-8 | M1-55 | LTKGILGFV | 0.98 | 1.95 |

| A2-9 | M1-178 | RMVLASTTA | 1 | 1.86 |

| A2-10 | M1-116 | ALSYSAGAL | 0.7 | 1.74 |

| A2-11 | M1-146 | LVCATCEQI | 0.87 | 1.7 |

| A2-12 | M1-60 | LGFVFTLTV | 1 | 1.69 |

| A2-13 | M1-138 | VTTEVAFGL | 0.77 | 1.68 |

| A2-14 | M1-47 | KTRPILSPL | 1 | 1.67 |

| A2-15 | M1-129 | GLIYNRMGA | 0.72 | 1.64 |

| A2-16 | M2-35 | ILHLILWIL | 0.89 | 2.83 |

| A2-17 | M2-34 | GILHLILWI | 0.91 | 2.66 |

| A2-18 | M2-38 | LILWILDRL | 0.89 | 2.41 |

| A2-19 | M2-3 | LLTEVETPI | 0.74 | 2.2 |

| A2-20 | M2-42 | ILDRLFFKC | 0.92 | 2.08 |

| A2-21 | M2-41 | WILDRLFFK | 0.92 | 1.91 |

| A2-22 | M2-32 | IIGILHLIL | 0.91 | 1.74 |

| A2-23 | M2-45 | RLFFKCIYR | 0.81 | 1.7 |

| A2-24 | NP-55 | RLIQNSLTI | 0.7 | 2.51 |

| A2-25 | NP-48 | KLSDYEGRL | 0.74 | 2.46 |

| A2-26 | NP-158 | GMDPRMCSL | 1 | 2.38 |

| A2-27 | NP-258 | FLARSALIL | 0.79 | 2.34 |

| A2-28 | NP-357 | KLSTRGVQI | 0.74 | 2.15 |

| A2-29 | NP-225 | ILKGKFQTA | 1 | 1.9 |

| A2-30 | NP-328 | LVWMACHSA | 0.74 | 1.74 |

| A2-31 | NP-263 | ALILRGSVA | 1 | 1.71 |

Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of class II influenza ICS.

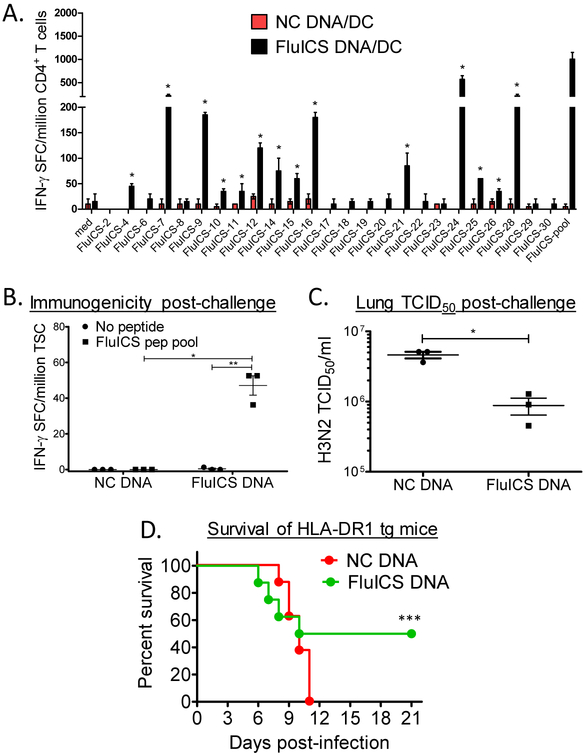

To determine immunogenicity of the selected class II ICS, mice expressing the common human class II allele HLA-DR1, and lacking endogenous murine class II [19], were vaccinated in a prime-boost fashion with naked DNA and peptide pool-pulsed DC. Splenic CD4+ T cells from vaccinated mice were stimulated with antigen presenting cells (APC) pulsed with individual peptides (or DMSO control) in IFN-γ ELISPOT assays. As shown in Fig. 1A, 14 of 25 predicted promiscuous pan-DR-restricted epitopes were immunogenic in HLA-DR1 Tg mice. Similar results were obtained in both female (shown) and male (not shown) vaccinated mice.

Figure 1. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of highly conserved class II immunogenic consensus sequences (ICS) in HLA-DR1 transgenic mice.

In panel A, female HLA-DR1 transgenic mice were vaccinated i.m. twice 2 weeks apart with a DNA vaccine encoding the 25 highly conserved influenza A ICS (FluICS) detailed in Table 1. These mice were additionally vaccinated with mature HLA-DR1 transgenic dendritic cells pulsed with these same epitopes. Shown are splenic CD4+ T cell IFN-γ ELISPOT responses determined 4 weeks after final vaccination, and 4 days post-intranasal A/PR/8 H1N1 (pooled cells from groups of N=2 mice; positive responses as defined in Methods marked with asterisks). In panels B-D HLA-DR1 transgenic mice were immunized 4 times with control or FluICS DNA vaccines. Four weeks post-vaccination mice were challenged intranasally with 30×LD50 Influenza A/Victoria/3/75 (H3N2). Shown in panel B are total splenocyte IFN-γ ELISPOT results obtained 4 days post-challenge (N=3 female mice/group). Protection against H3N2 challenge was assessed 4 days post-infection by lung homogenate TCID50 assay (C; N=3 female mice/group) and by survival (D; N=8 mixed sex mice/group). (A-C) Data depicted as means ± standard errors. These data demonstrate that highly conserved influenza ICS are both immunogenic and protective in HLA-Tg mice. In panels B-D: *P<0.005 by 2-tailed unpaired t test, ** P=0.012 by 2-tailed paired t test, and ***P=0.039 by 1-tailed Fishers exact test.

To study the protective efficacy of our novel DNA vaccines given alone, encoding highly conserved and promiscuous pan-DR-restricted ICS, groups of HLA-DR1 Tg mice were vaccinated with control or FluICS DNA vaccines. One month after the final vaccination, mice were challenged with mouse-adapted influenza A/Victoria/3/75 H3N2 intranasally (~30 × LD50), and 4 days later representative mice were euthanized to analyze conserved FluICS peptide pool-specific T cell responses and lung H3N2 viral burden. Splenocytes from mice vaccinated with DNA encoding conserved influenza ICS were responsive to the conserved influenza T cell epitopes (Fig. 1B). Conserved FluICS DNA vaccines provided significant protection as assessed by lung viral burden (Fig. 1C; P<0.005 by unpaired t test). Notably, 50% of FluICS vaccinated HLA-DR 1 transgenic mice survived lethal challenge as compared to 0% of control vaccinated mice (Fig. 1D; P<0.05 by Fishers exact test). These results demonstrate the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of FluICS DNA vaccines in mice expressing a common human class II molecule.

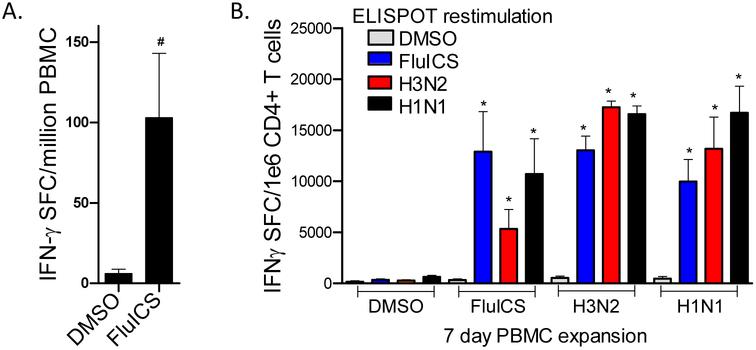

Importantly, human T cells were found to be highly reactive with the FluICS peptide pool. PBMC from 4 different individuals were stimulated in overnight IFN-γ ELISPOT assays with DMSO (control) or FluICS. The PBMC responded strongly to the FluICS peptides as demonstrated in Fig. 2A (P<0.05 by Mann Whitney U tests). Next, human CD4+ T cells expanded for 1 week with FluICS peptides were re-stimulated with APC pulsed with DMSO (control), FluICS peptides, live H3N2, and live H1N1. As shown in Fig. 2B, CD4+ T cells expanded with FluICS peptides, but not with DMSO alone, were highly responsive to restimulation with not only the FluICS peptide pool, but also H3N2- and H1N1-infected APC (N=5; P≤0.05 by both Mann Whitney U and paired t tests). Similar significant results were obtained after expanding PBMC for 1 week with live H3N2 and H1N1, and then re-stimulating with the FluICS peptide pool. Taken together, these results indicate that the conserved FluICS are presented to antigen-specific human CD4+ T cells in the context of influenza infection with diverse IAV strains.

Figure 2. Human CD4+ T cell immunogenicity of highly conserved class II immunogenic consensus sequences.

In panel A, PBMC from 4 volunteers were stimulated in overnight IFN-γ ELISPOT assays with either DMSO alone (control) or FluICS peptides. In panel B, PBMC from 5 volunteers were expanded in vitro with DMSO (control), FluICS peptides, or live IAV for 1 week. Then CD4+ T cells were isolated and stimulated in IFN-γ ELISPOT assays with APC pulsed with DMSO, FluICS peptides, or live IAV (H1N1 and H3N2). These data demonstrate human immunogenicity of highly conserved influenza ICS and their relevance with infection with diverse IAV strains. Data depicted as means ± standard errors. #P<0.05 by Mann Whitney U test, *P≤0.05 by Mann Whitney U and matched pair t tests.

Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of conserved HLA-A2-restricted influenza epitopes.

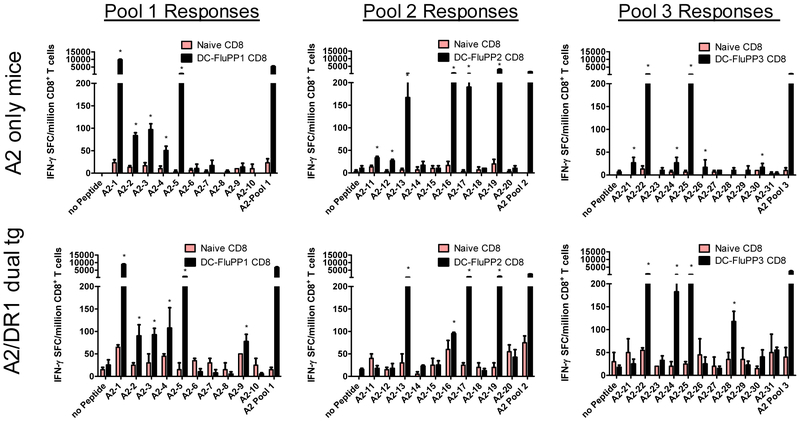

The epitope-MHC binding predictions shown in Table 3 were validated using a combination of in vivo and in vitro studies. These 31 predicted influenza epitopes (Table 3) were synthesized, pooled (10-11 peptides per pool), pulsed onto DC, and injected into HLA-A2 transgenic mice deficient in endogenous murine MHC I expression[20, 21]. Robust CD8+ T cell responses were induced, specific for many of the HLA-A2 predicted epitopes in two different strains of mice expressing HLA-A2 (Fig. 3). Overall, 19 of the 31 predicted HLA-A2-restricted epitopes were immunogenic in these model systems. Similar results were obtained in both strains of HLA-A2 transgenic mice.

Figure 3. Immunogenicity of highly conserved HLA-A2-restricted influenza A epitopes in HLA-A2 transgenic mice.

Mature dendritic cells (DC) from HLA-A2 and HLA-A2/DR1 transgenic mice were pulsed with pools of 10-11 putative conserved HLA-A2-restricted epitopes and i.v. injected into strain-matched recipient mice. To provide CD4 help for optimal CD8 T cell induction, DC also were pulsed with the highly promiscuous PADRE and OVA peptides that are immunogenic in all mice. Four weeks after the second vaccination, splenic CD8+ T cells were purified and added to IFN-γ ELISPOT assays along with naïve antigen presenting cells and individual peptides. Shown are results generated with CD8+ T cells purified from 2-3 HLA-A2 (top) and HLA-A2/DR1 transgenic mice (bottom) vaccinated with putative HLA-A2 peptides #1-10 (left panels), #11-20 (middle panels) and #21-31 (right panels). Control stimulations included media alone (no peptide) and the total peptide pool (10-11 peptides) used for vaccination of mice. Data shown represent means ± standard errors. Positive responses are marked with asterisks as defined in Methods.

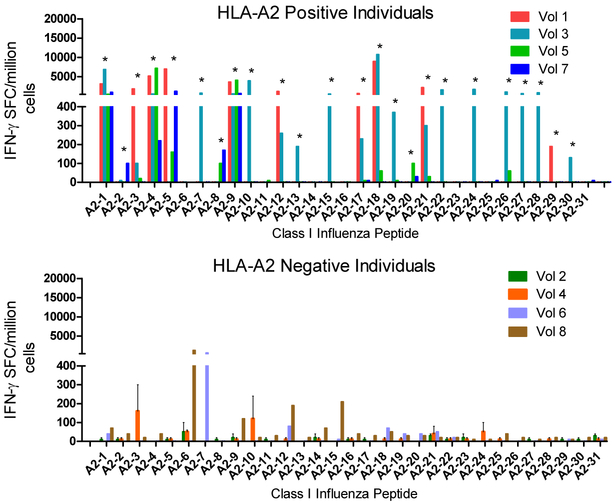

Next, naïve human PBMC immunoreactivity assays were conducted. PBMC collected from HLA-A2 negative and HLA-A2 positive healthy adult donors were expanded in vitro for 14 days with individual influenza peptides. Cells were then washed and restimulated with peptide or DMSO control in overnight IFN-γ ELISPOT assays. Shown in Fig. 4 are results obtained from HLA-A2 positive and HLA-A2 negative donors. Twenty-four of the 31 conserved influenza peptides predicted to be HLA-A2-restricted T cell epitopes induced a positive response in at least one of the four HLA-A2 positive PBMC sample, confirming the relevance of these epitopes for human influenza immunity. Nineteen (84%) HLA A2 epitopes immunogenic in HLA-A2 Tg mice were also immunogenic in humans, showing that HLA Tg mice are predictive of human responses. The minor reactivity with peptides detected in HLA-A2 negative PBMC could represent immunoreactivity across more than one supertype.

Figure 4. Human immunogenicity of highly conserved HLA-A2 restricted influenza A epitopes.

PBMC from HLA-A2 positive and HLA-A2 negative individuals were cultured with DMSO alone or with individual putative influenza A HLA-A2-restricted epitopes for 2 weeks with IL-2 provided on days 0, 2, 7 and 10. On day 14 of culture, cells were washed and added to IFN-γ ELISPOT assays with the same peptide as utilized for expansion. Shown are results [expressed as spot forming cells (SFC) per million cells] obtained from PMBC collected from 4 HLA-A2 positive (A-top) and 4 HLA-A2 negative (B-bottom) individuals (DMSO expansion subtracted). Data shown represent means ± standard errors for each volunteer. Positive responses are marked with asterisks as defined in Methods.

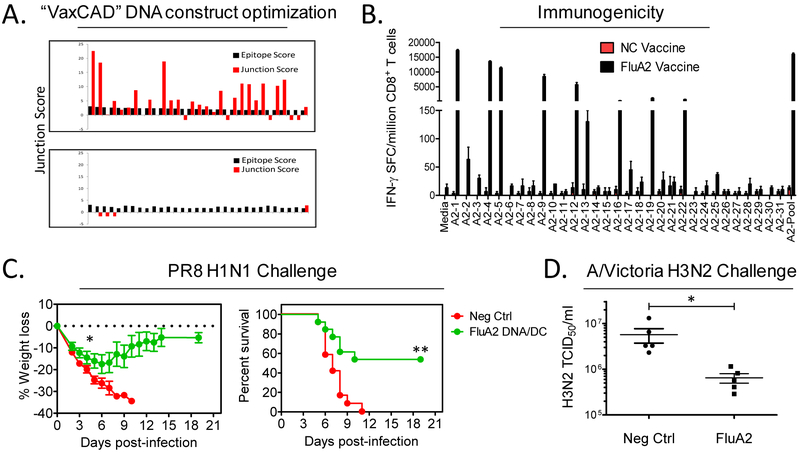

A DNA vaccine construct encoding each of these 31 predicted HLA-A2 epitopes was designed using VaxCAD [31] which reduces the creation of new epitopes at epitope junctions (Fig.5A). Next, HLA-A2 transgenic mice were vaccinated in a prime/boost fashion with DNA and DC/peptide vaccines. The vaccines were highly immunogenic, inducing robust epitope-specific CD8+ T cell responses in HLA-A2 transgenic mice (Fig. 5B). Other groups of control and Flu-A2 vaccinated mice were intranasally challenged with 8×LD50 of Influenza A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1), and post-challenge weights and survival monitored. As shown in Figs. 5C and 5D, mice immunized with vaccines incorporating highly conserved influenza HLA-A2-restricted epitopes were significantly protected as compared to vaccinated control mice with respect to severe weight loss (P<0.05 by Mann Whitney U test) and death (P<0.005 by Fisher’s exact and Mantel Cox log rank tests). In order to assess heterotypic protective immunity induced by the Flu-A2 vaccine, groups of vaccinated mice were challenged with A/Victoria/3/75 (H3N2), and lung viral titers determined 3 days post-challenge. As shown in Fig. 5E, mice receiving vaccines incorporating conserved HLA-A2-restricted influenza A epitopes were protected against H3N2 (P<0.05 by Mann Whitney U test). Cumulatively the results presented in Fig. 5 demonstrate that vaccines incorporating highly conserved influenza epitopes, identified using a comprehensive immunoinformatic approach, elicit potent T cell responses protective against diverse influenza strain challenges in mice expressing only a single human class I molecule.

Figure 5. Heterotypic protective immunity induced by vaccines incorporating highly conserved influenza epitopes.

DNA vaccines encoding 31 highly conserved influenza A HLA-A2 epitopes were designed using a computer assisted vaccine design tool (VaxCAD). Shown in A are predicted immunogenicity scores of selected epitopes (black bars) and junctions (red bars) of minigenes arranged by default order (top) and by VaxCAD (bottom). HLA-A2 transgenic mice were vaccinated i.m. with DNA encoding the HLA-A2-restricted conserved T cell epitopes (or control insert), and boosted with peptide-pulsed DC vaccines (delivered i.v.). CD4+ T cell help was provided to all mice by co-immunization with DNA and DC vaccines incorporating OVA and PADRE epitopes. One month following the final vaccination groups of mice were euthanized to study vaccine-induced T cell immunity. Shown in B are results from IFN-γ ELISPOT assays using purified CD8+ T cells stimulated with APC pulsed with individual (and pooled) peptides (N=3 male HLA-A2+ mice/group). In panel C, groups of control and FluA2 vaccinated mice were challenged with 8×LD50 of Influenza A/PR/8 H1N1, and post-challenge weights (left) and survival (right) monitored. Shown are results of 2 combined experiments with similar outcomes (combined sexes, N=12-13 mice per group). In panel D, groups of vaccinated mice were challenged with nonlethal A/Victoria H3N2 (1×105 TCID50). Three days later, viral burdens were assessed in lung homogenates by TCID50 assay (N=5 females mice/group). Data shown represent means ± standard errors. * P<0.05 by 2-sided Mann Whitney U test, ** P<0.005 by 2-sided Fisher’s exact and Mantel Cox log rank tests.

Discussion

The development of universal influenza vaccines protective against both future seasonal and pandemic viruses is considered a top priority by public health programs worldwide[32]. Tens of thousands of people die from seasonal influenza in the US alone every year. The 1918-19 influenza pandemic killed up to 50-100 million people, and future pandemics threaten to do so again. Current seasonal vaccines can be effective but need to be given every year because the circulating viruses mutate rapidly. Public health epidemiologists must predict what will become the most important circulating strains in advance of each influenza season, leaving only a few months to prepare vaccines. Sometimes the predictions are wrong leading to major mismatches between antigenic targets expressed by circulating influenza strains causing disease and the vaccines designed to induce protection. These problems exist because all conventional influenza vaccines target the most rapidly mutating but strongly immunogenic surface antigens, hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). Novel vaccines that induce immunity against highly conserved influenza sequences are urgently needed (see reference [32] and review [33]).

The results presented here provide proof-of-concept for a potentially paradigm-shifting T cell targeting vaccination strategy that could induce protection against all past and future influenza A viruses in virtually all people worldwide. We first identified highly conserved sequences present in influenza strains representing all past pandemic strains, dozens of seasonal strains, and even avian H5 and H7 strains that are currently considered the highest risks for future pandemics. We next utilized cutting-edge immunoinformatic tools to identify predicted T cell epitopes within the highly conserved sequence subset based on motifs known to be important for binding to HLA molecules required for presentation to T cells. Epitope predictions were confirmed both in HLA transgenic mice and with human peripheral blood lymphocytes. New DNA vaccines were made encoding strings of highly conserved and immunogenic T cell epitopes. These novel vaccines induced protection in HLA transgenic mice against diverse influenza strains. These results clearly demonstrate that vaccines incorporating highly conserved influenza A epitopes can provide broad protection against diverse influenza viruses, confirming the relevance of our strategy for generating novel universal influenza vaccines.

Vaccines encoding putative promiscuous HLA-DR ICS were immunogenic and efficacious against H3N2 influenza challenge in HLA-DR1 transgenic mice, as measured both by survival and lung viral burdens. Importantly these HLA-DR ICS vaccines were designed to contain epitopes capable of stimulating only CD4+ helper T cells and thus demonstrate that vaccines targeting only CD4+ T cell responses, and not neutralizing antibodies or CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, could provide protection. Memory CD4+ T cells induced by this vaccine could facilitate more rapid induction of neutralizing antibody and/or CD8+ T cell responses that develop during influenza viral challenge[34]. Alternatively, cytokines produced by memory/effector CD4+ T cells could increase intracellular resistance to viral replication, and/or these CD4+ T cells could mediate Fas/Fas-ligand pro-apoptotic signaling in influenza infected cells. Future work will be required to identify the specific mechanisms important for this CD4+ T cell-mediated protection. Although our proof-of-concept experiments completed to date with putative promiscuous HLA-DR ICS vaccines have focused on protection in HLA-DR1 transgenic mice, it is anticipated that these vaccines will provide broad immunogenicity in diverse HLA-DR transgenic mice and >95% of all humans. Previous studies utilizing the same immunoinformatic toolkit to identify pan-DR-restricted ICS indicate that this is an achievable goal[35-37]. Indeed, we found these ICS to be highly immunogenic for human CD4+ T cells from random human volunteers regardless of HLA-DR alleles expressed, demonstrating the power of our HLA Tg mouse model to predict broad immunogenicity in humans. Furthermore, the FluICS-specific T cells responded potently to both H3N2 and H1N1-infected APC (Fig 2B). However, detailed studies of human population coverage are needed, and we plan to more systematically study transgenic mice expressing a broader panel of distinct HLA-DR alleles, and PBMC from larger numbers of diverse human populations expressing distinct HLA-DR alleles, to further confirm the promiscuous immunogenicity of the conserved influenza ICS identified here.

Vaccines encoding highly conserved, influenza-specific and HLA-A2 supertype-restricted CD8+ T cell epitopes were constructed in parallel with the promiscuous HLA-DR ICS encoding vaccines. The HLA-A2 supertype is the most common of the 6 HLA class I supertypes that cover more than 95% of the world’s population. In fact, HLA-A2 is expressed by 40-60% of all humans worldwide. Therefore, we chose to perform proof-of-concept studies first with the HLA-A2 supertype. Similar to the strategy described above for identification of HLA-DR epitopes, we identified the highly conserved influenza genome sequence subset, predicted HLA-A2 supertype peptide binding, and studied the immunogenicity as well as protective capacity of predicted epitopes in HLA-A2 transgenic mice. We also confirmed immunogenicity in humans expressing HLA-A2. Overall, approximately 50% of the HLA-A2 supertype epitope predictions were confirmed in both HLA transgenic mice and human PBMC assays. It is important to point out that even though a peptide binds MHC, an immune response depends on availability of T cells with T cell receptors (TCRs) that recognize the peptide-MHC complex. It is expected that immunogenicity results obtained from HLA-A2 transgenic mice will not completely match those obtained from HLA-A2 supertype positive individuals since mice did not evolve with HLA and there are differences in T cell selection and the TCR repertoire between mice and humans. Therefore, we believe the results detected in HLA transgenic mouse models significantly underestimate the epitopes that could be immunogenic in humans. Indeed, most of the predicted HLA-A2 epitopes were shown to be recognized by human T cells (24 of 31), even though some were not immunogenic in the HLA-A2 transgenic murine models. Most importantly, the immune responses induced by vaccines encoding conserved, HLA-A2 supertype-restricted influenza epitopes were broadly protective against challenges with both the highly murine virulent H1N1 PR8 strain, and a less virulent mouse-adapted H3N2 viral strain. These HLA-A2-restricted CD8+ T cell responses were protective even though our vaccines did not include any known neutralizing antibody epitopes, and in fact none of our multi-epitope FluICS or Flu-A2 vaccines induced antibody responses against the viruses utilized in our work (data not shown). Therefore, our work also provides further proof-of-concept for the overall strategy focused on the development of T cell targeting universal influenza vaccines, either as stand-alone vaccines or as an adjunct to seasonal vaccines.

The development and refinement of immunoinformatic tools has allowed for the identification of numerous T cell epitopes for a variety of pathogens. In fact, several T cell-based multi-epitope vaccines have been generated and proven to be highly successful in mice expressing human MHC[15, 16, 38]. Human T cell epitope-based vaccine trials so far have not always been as convincing. For example, an epitope-based vaccine for HIV failed to generate measurable T cell responses in humans[39, 40]. However, in this epitope-based HIV vaccine study, the only CD4+ T cell epitope included in the DNA vaccine (PADRE) failed to induce immune responses in most of the vaccinees, suggesting a deficiency in the vaccine delivery platform or specific construct itself. Other efforts to induce T cell immunity in humans have been more successful. For example, several epitope-based vaccines for various cancers have proven immunogenic[41-46]. Recently, an artificial recombinant protein expressing a very limited number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell influenza epitopes was shown to induce T cell responses, and led to enhanced HA-based responses induced by later booster vaccinations with conventional influenza vaccines[47, 48].

Currently approved influenza vaccines are designed to induce robust B cell (antibody) immunity against the major viral surface proteins HA and NA. However, because of antigenic drift and shift in these protein sequences, antibodies do not generally exhibit potent cross-strain neutralization activity. In contrast, internal antigens M1, M2, and NP are highly conserved among diverse influenza A strains, and T cells recognizing these conserved antigens can recognize and protect against infection with diverse influenza strains. Furthermore, parallel studies have found that antibodies directed against conserved regions within the HA stalk can provide cross-strain protective immunity[49]. It is therefore important to consider combining conserved T cell and broadly neutralizing Ab epitopes in future universal influenza vaccine constructs to induce the most broadly heterotypic protective immunity.

Other groups have generated multi-epitope vaccines which have provided partial protection against influenza challenge (eg – references [50, 51]). However, our work presented here is novel in at least 4 major ways. First, our approach is focused on identifying epitopes expressed and conserved across highly diverse IAV strains including seasonal and potential pandemic avian and swine strains. In contrast, we note that some but not all of the epitopes reported in previous publications are in fact poorly conserved. Therefore, the vaccine constructs generated using our approach are likely to have more broadly protective effects than previously described vaccines. Second, previously reported IAV class II epitopes are, in general, native linear IAV sequences. Our class II immunoinformatic strategy relies on the identification of core conserved promiscuous 9-mers which are then extended in both directions to include additional epitopes from multiple strains and subtypes, resulting in longer and more dense epitope-rich immunogens with broader influenza coverage. Vaccines incorporating these longer, promiscuous ICS are thus anticipated to have high universal relevance at both the pathogen and human host levels. Third, although immunoinformatic-driven vaccine approaches are not novel overall, our approach goes beyond conventional analysis of influenza 9-mer sequences for HLA binding potential by additionally evaluating the effect of T cell epitopes that are homologous with human protein epitopes on the T cell receptor-facing side of binding 9-mers. We have proposed that these homologies are a natural means of viral camouflage whereby pathogens induce regulatory T cells to suppress protective cellular and antibody responses and evade immune clearance [28]. We developed and validated the JanusMatrix algorithm to account for potential homologies with human sequences on the TCR-face of HLA-binding 9-mers. In one application of JanusMatrix, we identified a Treg-inducing epitope in poorly immunogenic H7N9 HA, and improved cellular and humoral responses to a novel HA engineered to delete the epitope ([17, 18] and unpublished). In addition, examining cross-conservation with self may reduce the potential for unexpected off-target effects such as were observed for a known cancer epitope (MAGE A3 - EVDPIGHLY). We performed a post-hoc JanusMatrix analyses and identified a peptide found in human cardiac tissues (titin - ESDPIVAQY) which shares predicted HLA binding and sequence homology with TCR-facing amino acids with the MAGE A3 epitope (unpublished analyses). This is of great importance, since 2 individuals receiving adoptive immunotherapies of MAGE A3-specific T cells died within 5 days of transfer as a result of titin-autoreactive T cells causing cardiovascular toxi city [52, 53]. Therefore, we believe that it is important to examine the TCR-face of T cell epitopes for cross-conservation with the TCR facing residues of similarly HLA-restricted self epitopes when selecting epitopes to include in a universal influenza vaccine. Finally, arrangement of synthetic genes can be complicated, and due to the nature of compiling multiple epitopes with dense HLA-binding motifs, new artificial epitopes may be introduced at epitope junctions (neo-epitopes). To address this issue, we use the VaxCAD algorithm that minimizes junctional immunogenicity and creation of neo-epitopes to optimize the construction of synthetic genes. The novel approaches described above may yield safer and more effective vaccines. However, these hypotheses must be tested in future studies. For example, epitopes identified using our approach and those predicted elsewhere (eg-[50, 51, 54, 55]), after exclusion of peptides with homology to the TCR-facing self MHC binding peptides, should be compared in future head-to-head immunogenicity and protection experiments to identify the best epitopes to include in future T cell-targeting universal influenza vaccines.

In conclusion, we have shown that T cell-targeted vaccines composed of multiple pan-DR- and HLA-A2 restricted, highly conserved influenza epitopes are immunogenic and protective in mice expressing the appropriate human MHC. Future studies to identify conserved influenza T cell epitopes restricted by additional MHC I supertypes should be prioritized to rapidly generate T cell-based vaccines relevant for all diverse human populations. Other avenues worthy of exploration include generation and testing of new vaccines designed to specifically induce broadly-reactive mucosal influenza-specific T and B cells with the ultimate goal of providing lifelong protection against all seasonal and pandemic influenza A strains.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Approach used here can be expanded to generate flu vaccine with universal relevance

Identified T cell epitopes induced heterologous protection in HLA transgenic mice

Conserved flu putative immunogenic sequences were identified via immunoinformatics

Predicted HLA-A2 and pan-DR-restricted epitopes immunogenic in HLA-transgenic mice

Predicted CD4 and CD8 epitopes induced effector function in human T cells

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Institut Pasteur for providing HLA-A2 and HLA-A2/DR1 transgenic mice[20, 21]. The following reagent was obtained through BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH: Influenza A Virus, A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1), NR-3169 (used for stimulation of human PBMC). This work was funded by NIH R21-AI105605-01 to D.F.H.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].WHO. Fact sheet N°211 - Influenza (Seasonal). 2014.

- [2].Belshe RB. The origins of pandemic influenza--lessons from the 1918 virus. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2209–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Taubenberger JK, Morens DM. 1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:15–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Shrestha SS, Swerdlow DL, Borse RH, Prabhu VS, Finelli L, Atkins CY, et al. Estimating the burden of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in the United States (April 2009-April 2010). Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52 Suppl 1:S75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Schulman JL, Kilbourne ED. Induction of Partial Specific Heterotypic Immunity in Mice by a Single Infection with Influenza a Virus. J Bacteriol. 1965;89:170–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Liang SH, Mozdzanowska K, Palladino G, Gerhard W. Heterosubtypic Immunity to Influenza Type-a Virus in Mice - Effector Mechanisms and Their Longevity. J Immunol. 1994;152:1653–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Benton KA, Misplon JA, Lo CY, Brutkiewicz RR, Prasad SA, Epstein SL. Heterosubtypic immunity to influenza A virus in mice lacking IgA, all Ig, NKT cells, or gamma delta T cells. J Immunol 2001. p. 7437–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].McMichael AJ, Gotch FM, Noble GR, Beare PA. Cytotoxic T-cell immunity to influenza. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:13–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jameson J, Cruz J, Terajima M, Ennis FA. Human CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocyte memory to influenza A viruses of swine and avian species. J Immunol. 1999;162:7578–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hoft DF, Babusis E, Worku S, Spencer CT, Lottenbach K, Truscott SM, et al. Live and inactivated influenza vaccines induce similar humoral responses, but only live vaccines induce diverse T-cell responses in young children. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:845–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sonoguchi T, Naito H, Hara M, Takeuchi Y, Fukumi H. Cross-subtype protection in humans during sequential, overlapping, and/or concurrent epidemics caused by H3N2 and H1N1 influenza viruses. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:81–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Epstein SL. Prior H1N1 influenza infection and susceptibility of Cleveland Family Study participants during the H2N2 pandemic of 1957: an experiment of nature. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Moise L, Buller RM, Schriewer J, Lee J, Frey SE, Weiner DB, et al. VennVax, a DNA-prime, peptide-boost multi-T-cell epitope poxvirus vaccine, induces protective immunity against vaccinia infection by T cell response alone. Vaccine. 2011;29:501–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Snyder JT, Belyakov IM, Dzutsev A, Lemonnier F, Berzofsky JA. Protection against lethal vaccinia virus challenge in HLA-A2 transgenic mice by immunization with a single CD8+ T-cell peptide epitope of vaccinia and variola viruses. J Virol. 2004;78:7052–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gregory SH, Mott S, Phung J, Lee J, Moise L, McMurry JA, et al. Epitope-based vaccination against pneumonic tularemia. Vaccine. 2009;27:5299–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Moise L, Tassone R, Latimer H, Terry F, Levitz L, Haran JP, et al. Immunization with cross-conserved H1N1 influenza CD4+ T-cell epitopes lowers viral burden in HLA DR3 transgenic mice. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2013;9:2060–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Liu R, Moise L, Tassone R, Gutierrez AH, Terry FE, Sangare K, et al. H7N9 T-cell epitopes that mimic human sequences are less immunogenic and may induce Treg-mediated tolerance. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2015;11:2241–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wada Y, Nithichanon A, Nobusawa E, Moise L, Martin WD, Yamamoto N, et al. A humanized mouse model identifies key amino acids for low immunogenicity of H7N9 vaccines. Scientific reports. 2017;7:1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rosloniec EF, Brand DD, Myers LK, Whittington KB, Gumanovskaya M, Zaller DM, et al. An HLA-DR1 transgene confers susceptibility to collagen-induced arthritis elicited with human type II collagen. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1113–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Pascolo S, Bervas N, Ure JM, Smith AG, Lemonnier FA, Perarnau B. HLA-A2.1-restricted education and cytolytic activity of CD8(+) T lymphocytes from beta2 microglobulin (beta2m) HLA-A2.1 monochain transgenic H-2Db beta2m double knockout mice. J Exp Med. 1997;185:2043–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pajot A, Michel ML, Fazilleau N, Pancre V, Auriault C, Ojcius DM, et al. A mouse model of human adaptive immune functions: HLA-A2.1-/HLA-DR1-transgenic H-2 class I-/class II-knockout mice. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:3060–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Shu Y, McCauley J. GISAID: Global initiative on sharing all influenza data - from vision to reality. Euro surveillance : bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin. 2017;22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bao Y, Bolotov P, Dernovoy D, Kiryutin B, Zaslavsky L, Tatusova T, et al. The influenza virus resource at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. J Virol. 2008;82:596–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Brister JR, Ako-Adjei D, Bao Y, Blinkova O. NCBI viral genomes resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D571–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].De Groot AS, Ardito M, McClaine EM, Moise L, Martin WD. Immunoinformatic comparison of T-cell epitopes contained in novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus with epitopes in 2008-2009 conventional influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2009;27:5740–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Moise L, Gutierrez A, Kibria F, Martin R, Tassone R, Liu R, et al. iVAX: An integrated toolkit for the selection and optimization of antigens and the design of epitope-driven vaccines. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2015;11:2312–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Losikoff PT, Mishra S, Terry F, Gutierrez A, Ardito MT, Fast L, et al. HCV epitope, homologous to multiple human protein sequences, induces a regulatory T cell response in infected patients. Journal of hepatology. 2015;62:48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].De Groot AS, Moise L, Liu R, Gutierrez AH, Tassone R, Bailey-Kellogg C, et al. Immune camouflage: relevance to vaccines and human immunology. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2014;10:3570–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Moise L, Gutierrez AH, Bailey-Kellogg C, Terry F, Leng Q, Abdel Hady KM, et al. The two-faced T cell epitope: examining the host-microbe interface with JanusMatrix. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2013;9:1577–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Eickhoff CS, Van Aartsen D, Terry FE, Meymandi SK, Traina MM, Hernandez S, et al. An immunoinformatic approach for identification of Trypanosoma cruzi HLA-A2-restricted CD8(+) T cell epitopes. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2015;11:2322–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].De Groot AS, Marcon L, Bishop EA, Rivera D, Kutzler M, Weiner DB, et al. HIV vaccine development by computer assisted design: the GAIA vaccine. Vaccine. 2005;23:2136–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Erbelding EJ, Post DJ, Stemmy EJ, Roberts PC, Augustine AD, Ferguson S, et al. A Universal Influenza Vaccine: The Strategic Plan for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. J Infect Dis. 2018;218:347–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Clemens EB, van de Sandt C, Wong SS, Wakim LM, Valkenburg SA. Harnessing the Power of T Cells: The Promising Hope for a Universal Influenza Vaccine. Vaccines (Basel). 2018;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Laidlaw BJ, Craft JE, Kaech SM. The multifaceted role of CD4(+) T cells in CD8(+) T cell memory. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:102–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Moise L, Terry F, Ardito M, Tassone R, Latimer H, Boyle C, et al. Universal H1N1 influenza vaccine development: identification of consensus class II hemagglutinin and neuraminidase epitopes derived from strains circulating between 1980 and 2011. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2013;9:1598–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].De Groot AS, Ardito M, Moise L, Gustafson EA, Spero D, Tejada G, et al. Immunogenic Consensus Sequence T helper Epitopes for a Pan-Burkholderia Biodefense Vaccine. Immunome Res. 2011;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Koita OA, Dabitao D, Mahamadou I, Tall M, Dao S, Tounkara A, et al. Confirmation of immunogenic consensus sequence HIV-1 T-cell epitopes in Bamako, Mali and Providence, Rhode Island. Human vaccines. 2006;2:119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].McMurry JA, Gregory SH, Moise L, Rivera D, Buus S, De Groot AS. Diversity of Francisella tularensis Schu4 antigens recognized by T lymphocytes after natural infections in humans: identification of candidate epitopes for inclusion in a rationally designed tularemia vaccine. Vaccine. 2007;25:3179–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gorse GJ, Baden LR, Wecker M, Newman MJ, Ferrari G, Weinhold KJ, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte poly-epitope, DNA plasmid (EP HIV-1090) vaccine in healthy, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-uninfected adults. Vaccine. 2008;26:215–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wilson CC, Newman MJ, Livingston BD, MaWhinney S, Forster JE, Scott J, et al. Clinical phase 1 testing of the safety and immunogenicity of an epitope-based DNA vaccine in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected subjects receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:986–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lennerz V, Gross S, Gallerani E, Sessa C, Mach N, Boehm S, et al. Immunologic response to the survivin-derived multi-epitope vaccine EMD640744 in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII. 2014;63:381–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Asahara S, Takeda K, Yamao K, Maguchi H, Yamaue H. Phase I/II clinical trial using HLA-A24-restricted peptide vaccine derived from KIF20A for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Transl Med. 2013;11:291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kenter GG, Welters MJ, Valentijn AR, Lowik MJ, Berends-van der Meer DM, Vloon AP, et al. Vaccination against HPV-16 oncoproteins for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1838–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bocchia M, Gentili S, Abruzzese E, Fanelli A, Iuliano F, Tabilio A, et al. Effect of a p210 multipeptide vaccine associated with imatinib or interferon in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia and persistent residual disease: a multicentre observational trial. Lancet. 2005;365:657–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Ott PA, Hu Z, Keskin DB, Shukla SA, Sun J, Bozym DJ, et al. An immunogenic personal neoantigen vaccine for patients with melanoma. Nature. 2017;547:217–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Sahin U, Derhovanessian E, Miller M, Kloke BP, Simon P, Lower M, et al. Personalized RNA mutanome vaccines mobilize poly-specific therapeutic immunity against cancer. Nature. 2017;547:222–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Atsmon J, Kate-Ilovitz E, Shaikevich D, Singer Y, Volokhov I, Haim KY, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of multimeric-001--a novel universal influenza vaccine. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32:595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Atsmon J, Caraco Y, Ziv-Sefer S, Shaikevich D, Abramov E, Volokhov I, et al. Priming by a novel universal influenza vaccine (Multimeric-001)-a gateway for improving immune response in the elderly population. Vaccine. 2014;32:5816–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Krammer F, Pica N, Hai R, Margine I, Palese P. Chimeric hemagglutinin influenza virus vaccine constructs elicit broadly protective stalk-specific antibodies. J Virol. 2013;87:6542–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Ichihashi T, Yoshida R, Sugimoto C, Takada A, Kajino K. Cross-protective peptide vaccine against influenza A viruses developed in HLA-A*2402 human immunity model. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Alexander J, Bilsel P, del Guercio MF, Stewart S, Marinkovic-Petrovic A, Southwood S, et al. Universal influenza DNA vaccine encoding conserved CD4+ T cell epitopes protects against lethal viral challenge in HLA-DR transgenic mice. Vaccine. 2010;28:664–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Linette GP, Stadtmauer EA, Maus MV, Rapoport AP, Levine BL, Emery L, et al. Cardiovascular toxicity and titin cross-reactivity of affinity-enhanced T cells in myeloma and melanoma. Blood. 2013;122:863–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Cameron BJ, Gerry AB, Dukes J, Harper JV, Kannan V, Bianchi FC, et al. Identification of a Titin-derived HLA-A1-presented peptide as a cross-reactive target for engineered MAGE A3-directed T cells. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:197ra03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Assarsson E, Bui HH, Sidney J, Zhang Q, Glenn J, Oseroff C, et al. Immunomic analysis of the repertoire of T-cell specificities for influenza A virus in humans. J Virol. 2008;82:12241–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Savic M, Dembinski JL, Kim Y, Tunheim G, Cox RJ, Oftung F, et al. Epitope specific T-cell responses against influenza A in a healthy population. Immunology. 2016;147:165–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.