Abstract

Objectives:

To understand feedback from participants in Paired PLIÉ (Preventing Loss of Independence through Exercise), a novel, integrative group movement program for people with dementia and their care partners, in order to refine the intervention and study procedures.

Method:

Data sources included daily logs from the first Paired PLIÉ RCT group, final reflections from the second Paired PLIÉ RCT group, and responses to requests for feedback and letters of support from Paired PLIÉ community class participants. All data are reports from care partners. The qualitative coding process was iterative and conducted with a multidisciplinary team. The coding team began with a previously established framework that was modified and expanded to reflect emerging themes. Regular team meetings were held to confirm validity and to reach consensus around the coding system as it was developed and applied. Reliability was checked by having a second team member apply the coding system to a subset of the data.

Results:

Key themes that emerged included care partner-reported improvements in physical functioning, cognitive functioning, social/emotional functioning, and relationship quality that were attributed to participation in Paired PLIÉ. Opportunities to improve the intervention and reduce study burden were identified. Care partners who transitioned to the community class after participating in the Paired PLIÉ study reported ongoing benefits.

Conclusion:

These qualitative results show that people with dementia and their care partners can participate in and benefit from community-based programs like Paired PLIÉ that include both partners, and focus on building skills to maintain function and quality of life.

Keywords: dementia and cognitive disorders, caregiving, psychosocial interventions

Introduction

Currently more than 5 million Americans are living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, and this number is expected to rise as high as 16 million by the year 2050 (Alzheimer’s Association, 2017). People with dementia experience a progressive decline in cognitive function that impairs their ability to carry out daily activities independently. Addressing these needs requires skilled medical management and help from informal care partners; more than 15 million care partners in the U.S. are providing an estimated $230 billion annually in unpaid services. These care partners often experience burden, stress, loneliness, and isolation (Alzheimer’s Association, 2017). Interventions are needed to improve the lives of both people living with dementia and their care partners.

Available dementia medications provide small improvements in cognitive and physical function but do not change the disease course, improve quality of life or reduce care partner burden; in addition, they are often discontinued due to side effects (Birks, 2006). In contrast, there is growing evidence that non-pharmacological interventions have larger effects on a wider range of outcomes for both people with dementia and care partners (Aguirre, Woods, Spector, & Orrell, 2013; Forbes, Forbes, Blake, Thiessen, & Forbes, 2015; Olazarán et al., 2010; Ueda, Suzukamo, Sato, & Izumi, 2013). Multi-domain interventions that combine physical, mental and social activities (including music) with care partner education are associated with improvements across multiple outcomes (Olazarán et al., 2010). Yet few programs designed for people with dementia and their care partners are widely available in the community. In contrast to general programs for older adults, there are almost no community-based programs for people with dementia other than support groups and adult day programs.

Preventing Loss of Independence through Exercise (PLIÉ; Barnes et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2015) is a novel, multi-domain program that integrates physical movement sequences (training procedural or ‘muscle’ memory for basic daily activities such as transitioning between siting and standing), cognitive stimulation (mindful body awareness), social engagement (group movement and sharing of in-the-moment experiences), music, and care partner education (monthly home-visit). PLIÉ was originally designed and tested in an adult day care setting with groups of people with dementia and is currently being tested in a clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02350127).

Paired PLIÉ is an adapted version of the PLIÉ program designed for groups of people with dementia and care partners to perform together. It was developed and refined during two pilot studies and is currently being tested in a small randomized, controlled trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02729311). Graduates of our pilot studies and ongoing clinical trials are invited to join a for-fee weekly community class. The goal of this study was to perform a process evaluation in the first two Paired PLIÉ clinical trial groups and the ongoing community class to gain insight into the impact of the program and to identify opportunities for improvement.

Methods

Participants

Participants included graduates of our ongoing Paired PLIÉ clinical trial and members of the ongoing community class. Participants were enrolled in dyads of a person with mild-to-moderate dementia (defined as Clinical Dementia Rating of 0.5, 1, or 2; Morris, J. C., 1993) and their primary care partner (family member or paid). All participants were fluent in English, able to walk independently or using a cane or walker and lived in the community in a private home or apartment.

We excluded individuals with behavioral or physical issues that would impede participation or would be disruptive or dangerous to themselves or others (e.g., severe vision or hearing impairment, physical impairment such as individuals who use a wheelchair or who are bed-bound, mental health condition such as bipolar disorder), plans to move before the end of the study period, medical condition with limited life expectancy (e.g., metastatic cancer), participation in another research study, or unwillingness to be video-recorded for quality control purposes. All study participants provided written consent and/or assent.

Data Sources

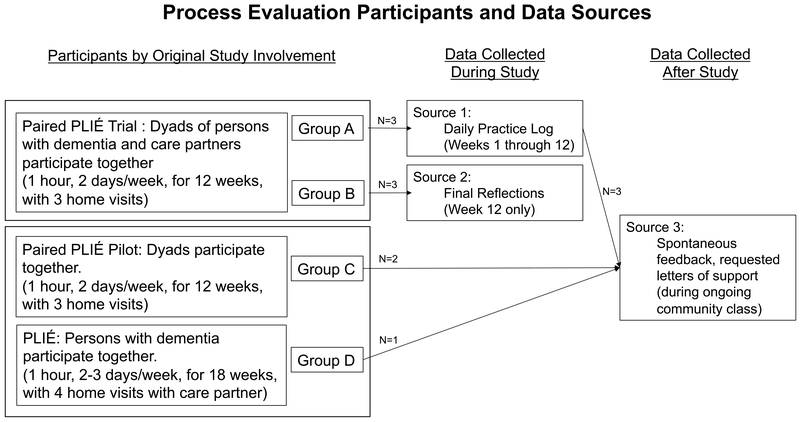

For this process evaluation, data were drawn from three sources (Figure 1). 1) From Group A, daily practice logs. The first group of Paired PLIÉ clinical trial dyads were asked to practice Paired PLIÉ movements at home, and care partners were asked to fill in a daily practice log in which they recorded what the dyads did, how many minutes, and what the care partners noticed. 2) From Group B, final reflections. After receiving feedback from Group A that the daily practice logs were burdensome, in Group B we instead asked care partners to report final reflections at the end of the program. Specific questions asked how the program affected them and the person with dementia, what they enjoyed most, what was most difficult, and suggestions for improvement. 3) From members of different trials who chose to continue in a community class, community class feedback and letters of support. Dyads who completed our pilot studies or ongoing clinical trials were invited to join an ongoing for-fee community class. Community class participants were invited to send us feedback on their experiences and to write letters of support for a grant application.

Figure 1.

Process evaluation participants and data sources.

All data were entered into an excel spreadsheet and qualitatively coded for care partners’ reports on the effects of Paired PLIÉ. Care partners’ pseudonyms were chosen from the five most popular names in the United States for their gender and birth year. Each care partner quote in this manuscript includes a citation indicating the pseudonym, source, and, for practice logs, the week of the quote.

Analysis

The qualitative analysis process was iterative and collaborative and included independent researchers (JC, KH) as well as Paired PLIÉ investigators (DB, WM) and an outcomes assessor (MV). The analysis team began with the coding framework established in the previous qualitative study of the PLIÉ program (Wu et al., 2015), with overarching code domains of functional changes, emotional changes, and social changes. The entire team independently coded daily practice logs from Paired PLIÉ Group A using both the deductive codes of Wu et al., and developing new codes inductively to respond to new themes in the data. We met to discuss and develop an initial list of codes and definitions for this project. JC tested and refined this initial codebook by applying them systematically to the Group A data. Regular meetings with the coding team were held throughout the analysis process to assess validity and reach consensus around the coding system. Next, final reflections from Group B and feedback and letters of support from community class participants were added to the dataset, and the coding system was further refined to reflect the themes from these additional data sources. MV also applied the coding system to a subset of the data in order to check reliability against the primary coder; reliability was high, and in those few situations in which the coders disagreed, the differences were discussed with the interdisciplinary team, sometimes resulting in revision of code definitions. This process continued until consensus was achieved on all codes. JC then reviewed all data to ensure codes were applied according to the finalized codebook.

Results

Demographic characteristics of care partners are shown in Table 1. A total of nine care partners provided data: 5 women, 4 men; 8 white, 1 Asian; 4 wives, 2 husbands, 3 adult children; 3 Paired PLIÉ Group A; 3 Paired PLIÉ Group B; 3 community class. Analysis identified several themes related to participation in Paired PLIÉ. Themes regarding the care partners’ observations of both the person with dementia’s experience and the care partners’ experience included physical functioning, cognitive functioning, and social/emotional functioning. The final two themes focused on care partners’ observations of the dyadic relationship and of intervention logistics.

Table 1.

Care Partner Characteristics and Data Sources

| Pseudonym | Group(s) | Age | Sex | Race | Care Partner Relationship | Date Source(s) | Dementia Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Susan | Paired PLIÉ Group A, community class | 60 | Female | White | Daughter | Daily practice log, feedback | Amnestic disorder |

| Mary | Paired PLIÉ Group A, community class | 77 | Female | White | Wife | Daily practice log, letter of support | Alzheimer’s disease |

| Linda | Paired PLIÉ Group A, community class | 71 | Female | White | Wife | Daily practice log, letter of support | Vascular dementia |

| Barbara | Paired PLIÉ Group B | 72 | Female | Asian | Wife | Final reflection | Alzheimer’s disease |

| Michael | Paired PLIÉ Group B | 44 | Male | White | Son | Final reflection | Alzheimer’s disease |

| Robert | Paired PLIÉ Group B | 85 | Male | White | Husband | Final reflection | Alzheimer’s disease |

| James | Paired PLIÉ Pilot, community class | 76 | Male | White | Husband | Letter of support | Mild cognitive impairment |

| Patricia | PLIÉ trial, community class | 70 | Female | White | Wife | Letter of support | Alzheimer’s disease |

| John | Paired PLIÉ Pilot, community class | 62 | Male | White | Son-in-Law | Letter of support | Dementia |

People with Dementia.

Theme 1: Physical functioning.

Most care partners noted improvements in the person with dementia’s physical functioning including improved mobility, balance, and coordination. These comments started in the first week and continued through the post-program feedback. For example, one care partner wrote, ‘[He] started to trip and was able to catch himself. He appears to have quicker reflexes’ (Linda, letter of support). Another reported being surprised with muscle memory: ‘I was amazed at the value of the muscle memory but was not quite sure how to put 2 & 2 together until my husband fell and broke his femur. On queue he could figure out to get in and out of bed as well as getting in and out of the car and picking himself up from the floor after playing with our dog… It proved that this muscle memory is like an angel sitting on our shoulders. This would have NEVER happened without the PLIÉ program’ (Patricia, letter of support).

One care partner expressed concern that Paired PLIÉ may have contributed to a problem with physical functioning: ‘Mom had some unwell feelings right after class. That night she also complained of a pain in her neck at the base of the skull’ (Susan, daily practice log, week 5). However, this concern was not raised during future reports, and no other care partners reported attributing problems with physical functioning to Paired PLIÉ.

Theme 2: Cognitive functioning.

Care partners sometimes attributed improvements in cognitive functioning to Paired PLIÉ. For instance, one care partner wrote, ‘He finished two crosswords completely (this was never done prior)’ (Mary, daily practice log, week 4). Some care partners also commented on the person with dementia’s increased mindfulness, a skill that Paired PLIÉ targets directly: ‘I have to think that anything that contributes to mindfulness on my wife’s part helps bring her out of the fog in which she seems so often to be lost’ (James, Community Class, letter of support).

Care partners sometimes described variable attention and engagement in the person with dementia during the group sessions and the at-home practices. One initially wrote that her husband ‘seemed more alert’ during Paired PLIÉ (Linda, daily practice log, week 1); she later noted fluctuations in attention, writing that he ‘does better at home… where I can have his attention so doesn’t fall asleep’ (Linda, daily practice log, week 5). Despite some concerns about her husband’s level of engagement, this care partner found great value in Paired PLIÉ; she later wrote that it ‘contributed to his sense of well-being, functionality and contentment’ (Linda, letter of support).

Care partners noted cognitive deficits in the person with dementia, but they did not attribute these to Paired PLIÉ. One care partner initially suggested that the person with dementia’s cognitive impairments prevented her from benefitting from Paired PLIÉ, saying that she ‘cannot mentally and purposefully use what she learns in class’ (Susan, daily practice log, week 3). However, this belief changed as the program continued; she later wrote, ‘I see a difference in [person with dementia]. She walks taller, moves better, and seems less resistant to moving around’ (Susan, feedback).

Theme 3: Social and emotional functioning.

Care partners reported positive emotions in the person with dementia during and after Paired PLIÉ sessions. One wrote that the benefit of the program was ‘Primarily emotional - she looked forward eagerly to attending, and usually the hour had a productive residual effect on the rest of her day’ (Robert, final reflection). Several care partners mentioned specific elements that the person with dementia enjoyed, including music, exercise, and mindfulness, as well as the diversity of activities and the small group size. ‘Partner enjoys the class - participates, attentive, likes the music and participants and teachers. Happy here’ (Barbara, final reflection).

Care partners

Theme 1: Physical functioning.

Care partners also attributed improvements in their own physical functioning to Paired PLIÉ. They noted improved ease for standing from kneeling, better posture, and even movements that were not directly targeted by Paired PLIÉ such as regained ability to turn ‘from stomach to back’ during a massage (Mary, daily practice log, week 5).

One care partner attributed some physical discomfort to Paired PLIÉ, writing that a previous condition precluded him from performing some exercises and resulted in ‘an uncomfortable aftereffect’ when performing others (Robert, final reflection). No other care partners noted problems related to physical functioning attributable to Paired PLIÉ.

Theme 2: Cognitive functioning.

Several care partners noted enhanced mindfulness in themselves. They described becoming aware of bodily sensations they had previously taken for granted and linked the mindfulness practice to feeling less stress. One wrote that ‘attention to temperature, touch, feel, emotions’ resulted in feeling ‘calmer, peaceful’ (Susan, daily practice log, week 1). Another relayed his belief that mindfulness practice was ‘contributing to my long-term health’ (James, letter of support).

Theme 3: Social and emotional functioning.

Several care partners reported reduced stress and increased positive emotion, and these feelings were implicitly or explicitly attributed to different aspects of Paired PLIÉ. One wrote, ‘I feel stress free during class’ (Barbara, final reflection). Care partners reported feeling more at ease because Paired PLIÉ encouraged self-soothing techniques, greater self-compassion, and mindfulness, and because it improved physical functioning in the person with dementia. ‘[W]hen he is safe and able to navigate the world around him at his own pace, I am also more at peace’ (Linda, Group A, letter of support).

Care partners also commented on the social connection within the group. They described a supportive group dynamic coalescing quickly and found value in connecting with others in the care partner role. One wrote, ‘One of the most positive things about the program was meeting other people who are in a similar situation’ (James, letter of support). Only one care partner commented on social connection in a negative light, noting that it felt a ‘bit uncomfortable to be touching strangers’ (Susan, Group A, week 5).

Relationship between person with dementia and care partner

Paired PLIÉ seemed to help foster positive feelings between the care partner and the person with dementia. One care partner wrote that the program helped her to feel closer to her mother. She wrote that Paired PLIÉ had reduced her ‘frustration and resentment… Mom is now learning ways to use her body to help her accomplish things she needs to do, and I am there to help her remember to use them. That is very helpful to both of us’ (Susan, feedback).

Intervention Logistics

Concerns expressed by care partners in Group A were addressed either immediately or in planning for Group B. Susan (in Group A) voiced concern for her mother’s well-being during class, describing health conditions that might make Paired PLIÉ too challenging. Group leaders responded by personalizing the exercises as needed; this response supported the person with dementia and seemed to ease the care partner’s concerns. Susan also reported frustration from not understanding the scope or goal of the classes until relatively late in the program and expressed burden and stress from the program evaluation components (e.g., the daily logs and other questionnaires). Similarly, Linda (in Group A) noted that the time requirements of the program evaluation affected her ability to engage in her own self-care. Their frustrations led to changes in Group B, including the creation of a clearer roadmap of Paired PLIÉ, and the use of a single final reflection rather than daily logs. This shift appears to have been helpful; the care partners in Group B did not express similar frustrations.

Care partners also suggested several ways to improve the program for future participants. Some suggested concrete additions to the program, such as increasing focus on physical balance, and the ‘addition of some stretches and light weights or [resistance] bands’ (Barbara, week 2, daily practice log). Others suggested broader changes to the structure of the program, such as sorting participants into groups by disease severity, creating videos to improve practice at home, and improving accessibility such that people with dementia and care partners could participate from anywhere.

Overall, care partners reported appreciating the program. In describing Paired PLIÉ, one wrote, ‘A program that produces results, is fun, and allows a person to retain his/her dignity, gets my support’ (Linda, letter of support).

Discussion

In this process evaluation, we analyzed care partners’ written responses to Paired PLIÉ. Care partners observed positive impacts of Paired PLIÉ for themselves, the people with dementia, and their relationship with each other. Where concerns were raised about the intervention or study burden in Group A, they were addressed in the next iteration of Paired PLIÉ and no similar concerns were raised by Group B. These results align with previous research of the original PLIÉ intervention (within only people with dementia, without class participation of care partners) showing positive effects on physical, cognitive and social/emotional functioning (Wu et al., 2015).

A growing body of evidence shows that non-pharmacological interventions benefit both people with dementia and care partners. In people with dementia, various non-pharmacological interventions have been found to improve outcomes ranging from inappropriate behaviors (Cohen-Mansfield, 2001), to functional mobility (Yao, Giordani, Algase, You, & Alexander, 2013); in care partners, non-pharmacological interventions can reduce distress, depression, anxiety, and hostility, among others (Brodaty, Green, & Koschera, 2003; Hou et al., 2014; Quayhagen et al., 2000). Paired PLIÉ appears to be on the cutting edge of evidence-based interventions in its multi-dimensional focus on physical, cognitive, and social/emotional functioning for both people with dementia and their care partners.

The limitations of the present process evaluation include a small sample size and a limited pool of qualitative data. The strengths of this evaluation include a thorough qualitative analysis of the available data, yielding important insights that informed intervention adaptation for Paired PLIÉ Group B and seemed to positively impact experiences.

In the future, we will engage in mixed-methods longitudinal analysis of the RCT data to assess efficacy. If successful, we aim to test effectiveness on a larger scale, then disseminate and implement Paired PLIÉ in order to benefit as many people with dementia and care partners as possible. Future studies of Paired PLIÉ will also systematically and proactively monitor adverse events, as people with dementia and their care partners are vulnerable populations and even the gentle exercises in the Paired PLIÉ program could result in an adverse event. In order to maximize participants’ benefits from the program and avoid adverse events, future iterations of this program will also continue to train instructors to adapt exercises to participants’ abilities.

There are few programs available that encourage the joint participation of people with dementia and care partners, or benefit both groups in terms of physical, cognitive, and social/emotional functioning. If the results of this qualitative analysis are confirmed in the larger clinical trial, Paired PLIÉ may prove to be a scalable program that improves daily function and quality of life for people with dementia and care partners during an extremely difficult time.

Table 2.

Sample quotes from care partners about persons with dementia.

| Primary Domain | Sub-Domain | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Functioning | Physical Improvements | ‘She is more mobile than when we started.’ (Robert, Group B, final reflection) |

| ‘Last week, he started to trip and was able to catch himself. He appears to have quicker reflexes, especially lateral movements.’ (Linda, Group A, letter of support) | ||

| Muscle Memory | ‘I was amazed at the value of the muscle memory but was not quite sure how to put 2 & 2 together until my husband fell and broke his femur. On queue he could figure out to get in and out of bed as well as getting in and out of the car and picking himself up from the floor after playing with our dog… It proved that this muscle memory is like an angel sitting on our shoulders. This would have NEVER happened without the PLIÉ program.’ (Patricia, Community Class, letter of support) | |

| Physical Problems | ‘Mom had some unwell feelings right after class. That night she also complained of a pain in her neck at the base of the skull. Wondering how much the classwork contributing to this.’ (Susan, Group A, week 5) | |

| Cognitive Functioning | Cognitive Improvement | ‘He finished two crosswords completely (this was never done prior).’ (Mary, Group A, week 4) |

| Mindfulness | ‘I have to think that anything that contributes to mindfulness on my wife’s part helps bring her out of the fog in which she seems so often to be lost.’ (James, Community Class, letter of support) | |

| Ability to Learn | ‘My mother in law had a stroke and she was not accepting that she could not do certain things that most of us take for granted. The class has helped her see that certain things that we need to do every day were hard for her at first but that if she would pay attention to what and how she was doing things that she could do it.’ (John, Group A, letter of support) | |

| Ability to Benefit | ‘[Person with dementia] cannot mentally and purposefully use what she learns in class.’ (Susan, Group A, week 3) | |

| Variable Attention | ‘seemed more alert [during Paired PLIÉ]’ (Linda, daily practice log, week 1) | |

| ‘does better at home without cushions on chair - where I can have his attention so doesn’t fall asleep’ (Linda, daily practice log, week 5). | ||

| ‘[Paired PLIÉ] has contributed to his sense of well-being, functionality and contentment in whatever dimension his mind is on a given day’ (Linda, community class, letter of support). | ||

| Social/Emotional | Enjoyment | ‘[The benefit of the program was] primarily emotional - she looked forward eagerly to attending, and usually the hour had a productive residual effect on the rest of her day.’ (Robert, Group B, final reflection) |

|

‘Partner enjoys the class - participates, attentive, likes the music and participants and teachers. Happy here.’ (Barbara, final reflection) |

Table 3.

Sample quotes from care partner about care partner.

| Primary Domain | Sub-Domain | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Functioning | Physical Improvements | ‘I was able to turn from stomach to back very easily - prior I could NOT do that and needed help.’ (Mary, Group A, week 5) |

| ‘Prior to that program and it’s exercises we both were out of shape physically. I myself could not stand from kneeling. Since completion, I can stand and can do so many things much easier.’ (Mary, Community Class, letter of support) | ||

| Physical Problems | ‘Because of my back condition, many of the movements were beyond me, others had an uncomfortable aftereffect.’ (Robert, Group B, final reflection) | |

| Cognitive Functioning | Mindfulness | ‘attention to temperature, touch, feel, emotions… calmer, peaceful.’ (Susan, week 1, daily practice log) |

| ‘…mindful standing from and sitting down into a chair and, for me especially, mindful walking. I am not afflicted as my wife is, but I still think of what I learned as contributing to my long-term health, both inside the home and in the street.’ (James, Community Class, letter of support) | ||

| Difficulties due to Burden | ‘Unable to get in mental state of thinking of exercises, commitment to this program.’ (Susan, Group A, week 4) | |

| Social/Emotional | Reduced Stress, Increased Positive Emotion | ‘I feel stress free during class.’ (Barbara, Group B, final reflection) |

| ‘PLIÉ is a valuable tool that, I think, has contributed to his sense of well-being, functionality and contentment in whatever dimension his mind is on a given day. And when he is safe and able to navigate the world around him at his own pace, I am also more at peace.’ (Linda, Group A, letter of support) | ||

| Social Connection | ‘Our group is so exceptional in how we became a community so easily and comfortable with each other.’ (Barbara, Group B, final reflection) | |

| One of the most positive things about the program was meeting other people who are in a similar situation. It also helps me feel more relaxed… we both look forward to keeping in touch with the class (John, Group B, letter of support) | ||

| It was nice to mix it up today, sit next to new people, have new partners. A bit uncomfortable to be touching strangers (Susan, Group A, week 5) | ||

| Frustration with Paired PLIÉ | ‘I had trouble understanding where the classes in the study were heading, why we were doing what we were doing. Toward the end I saw how everything was coming together to help us move in a way to make daily living easier. I don’t know if I just didn’t get it until later, or if the ‘end’ goal could have been stated earlier on to help me understand why we were doing what we were doing. That knowledge might have reduced some frustration I was having.’ (Susan, Group A, feedback) | |

| Worry for Health of Person with Dementia | ‘[Person with dementia]’s hip started hurting during the exercises but instructors had her sit down and she was still included in what everyone else was doing. That was nice.’ (Susan, Group A, week 6) |

Table 4.

Sample quotes from care partners about their relationship with the person with dementia.

| Primary Domain | Sub-Domain | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship | Relationship Improvements | ‘We managed to get a balance with our hand pushing, and I explained to Mom my feelings about the difficulties in our relationship. I am daughter, she mother, I am caretaker, she is care needer (her term!). I want to make her do things that I think are good for her (get up and walk, change positions, eat healthy…) and sometimes she resists being told what to do. I told her I felt if we could get a balance in our physical hand pushing it might transfer to our mental/emotional relationship. She was pleased with this idea. I certainly feel more relaxed and loving toward Mom after this positive exercise experience.’ (Susan, Group A, week 3) |

| ‘[B]efore the study there was tension between mom and me around exercise (I would nag her to get up and walk, move, and she would resist, which led to frustration and resentment). Mom is now learning ways to use her body to help her accomplish things she needs to do, and I am there to help her remember to use them. That is very helpful to both of us.’ (Susan, Group A, feedback) | ||

| ‘Getting along better with each other.’ (Mary, Group A, week 8) |

Table 5.

Sample quotes from care partner regarding intervention logistics.

| Primary Domain | Sub-Domain | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention Logistics | Frustrations | ‘Her hip started hurting during the exercises but instructors had her sit down and she was still included in what everyone else was doing. That was nice.’ (Susan, Group A, week 6) |

| ‘I had trouble understanding where the classes in the study were heading, why we were doing what we were doing. Toward the end I saw how everything was coming together to help us move in a way to make daily living easier. I don’t know if I just didn’t get it until later, or if the ‘end’ goal could have been stated earlier on to help me understand why we were doing what we were doing. That knowledge might have reduced some frustration I was having.’ (Susan, Group A, letter of support) | ||

| ‘The follow up class on Thursday mornings is very different for me. There is no pressure on me (I put none on myself). It is only once a week, and it is closer to home, a 10 minute drive instead of a 30 minute drive. And now I see what the class is doing for us, how it is helping in a real and important way. It is very different than an ‘exercise’ class. This is an important class where we practice and learn how to move our bodies in a supportive way during a time in life where mom is less able to move and function with ease.’ (Susan, Group A and Community Class, letter of support) | ||

| ‘My hope is that once PLIÉ is over I have my two mornings free to return to my own exercise routine. I will feel more motivated to do Paired routines. For now he is getting more exercise than I am!’ (Linda, Group A, week 6) | ||

| Suggestions | ‘Think he might benefit from addition of some stretches and light weights or bands.’ (Linda, Group A, week 2) | |

| ‘It would be wonderful if there were a way for us to practice the movements from home with videos or other supportive materials. Also some kind of a forum where care partners could ask specific questions when a need arises. We would benefit from the instructor answers as well as from other care partners’ tips as we all have developed tricks to fit unexpected situations. Such a wealth of knowledge could be easily shared.’ (Patricia, Community Class, letter of support) | ||

| Overall Satisfaction | ‘I would like to thank you all for having crossed the path of our lives and helping others like my husband and myself. We will owe you until the end. There aren’t many options available in the community. We are very thankful to be able to participate in the Paired PLIÉ program.’ (Patricia, Community Class, letter of support) | |

| ‘PLIÉ is a valuable tool that, I think, has contributed to his sense of well-being, functionality and contentment in whatever dimension his mind is on a given day. And when he is safe and able to navigate the world around him at his own pace, I am also more at peace. … PLIÉ directly addresses functioning, relaxation techniques and quality of life incorporating music and socialization. A program that produces results, is fun, and allows a person to retain his/her dignity, gets my support.’ (Linda, Group A, letter of support) |

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the Alzheimer’s Association under grant NPSASA-15-364656; the National Institute on Aging under grants T32AG049663 and T32AG000212; Tideswell at UCSF; Andrew and Ellen Bradley; the UCSF Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center; and the Atlantic Fellowship at the Global Brain Health Institute.

Footnotes

Requests for access to data should be submitted to the Dr. Barnes.

Disclosure of interest. As co-inventors of the Paired PLIÉ program, Dr. Barnes and Dr. Mehling have the potential to earn royalities if the program is commercialized. Dr. Casey, Dr. Harrison and Dr. Ventura have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

James J. Casey, San Francisco Veterans Affairs Health Care System

Krista L. Harrison, Division of Geriatrics, School of Medicine, University of California San Francisco

Maria I. Ventura, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, University of California Davis

Wolf Mehling, Department of Family and Community Medicine and Osher Center for Integrative Medicine, University of California San Francisco.

Deborah E. Barnes, UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences, Departments of Psychiatry and Epidemiology & Biostatistics, University of California San Francisco, and San Francisco Veterans Affairs Health Care System.

References

- Aguirre E, Woods RT, Spector A, & Orrell M (2013). Cognitive stimulation for dementia: A systematic review of the evidence of effectiveness from randomised controlled trials. Ageing Research Reviews, 12(1), 253–262. 10.1016/j.arr.2012.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2017). 2017 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 13(4), 325–373. 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes DE, Mehling W, Wu E, Beristianos M, Yaffe K, Skultety K, & Chesney MA (2015). Preventing Loss of Independence through Exercise (PLIÉ): A Pilot Clinical Trial in Older Adults with Dementia. PLOS ONE, 10(2), e0113367 10.1371/journal.pone.0113367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birks JS (2006). Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty H, Green A, & Koschera A (2003). Meta-Analysis of Psychosocial Interventions for Caregivers of People with Dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51(5), 657–664. 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00210.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J (2001). Nonpharmacologic interventions for inappropriate behaviors in dementia: a review, summary, and critique. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 9(4), 361–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes D, Forbes SC, Blake CM, Thiessen EJ, & Forbes S (2015). Exercise programs for people with dementia In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou RJ, Wong SY-S, Yip BH-K, Hung ATF, Lo HH-M, Chan PHS, … Ma SH (2014). The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction program on the mental health of family caregivers: a randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83(1), 45–53. 10.1159/000353278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC (1993). The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current Version and Scoring Rules. Neurology, 43, 2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olazarán J, Reisberg B, Clare L, Cruz I, Peña-Casanova J, Ser TD, … Muñiz R (2010). Nonpharmacological therapies in Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 30(2), 161–178. 10.1159/000316119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quayhagen MP, Quayhagen M, Corbeil RR, Hendrix RC, Jackson JE, Snyder L, & Bower D (2000). Coping With Dementia: Evaluation of Four Nonpharmacologic Interventions. International Psychogeriatrics, 12(2), 249–265. 10.1017/S1041610200006360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda T, Suzukamo Y, Sato M, & Izumi S-I (2013). Effects of music therapy on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews, 12(2), 628–641. 10.1016/j.arr.2013.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu E, Barnes DE, Ackerman SL, Lee J, Chesney M, & Mehling WE (2015). Preventing Loss of Independence through Exercise (PLIÉ): qualitative analysis of a clinical trial in older adults with dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 19(4), 353–362. 10.1080/13607863.2014.935290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao L, Giordani BJ, Algase DL, You M, & Alexander NB (2013). Fall risk-relevant functional mobility outcomes in dementia following dyadic tai chi exercise. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 35(3), 281–296. 10.1177/0193945912443319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]