To the Editor:

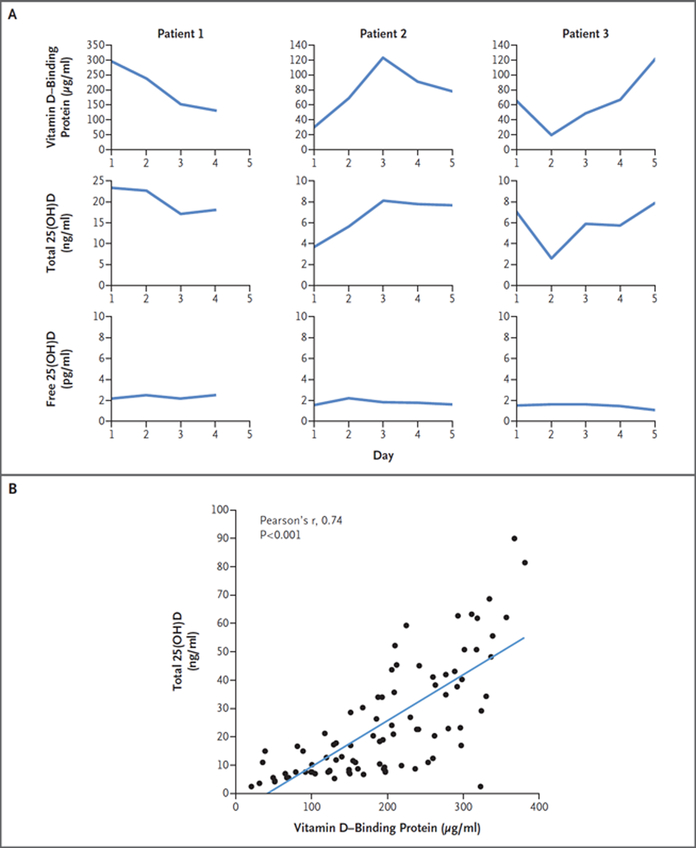

The recent case report by Henderson et al. of a patient with homozygous deletion of the GC gene encoding vitamin D–binding protein and profoundly diminished levels of circulating 25(OH)D corroborates the free-hormone hypothesis. In addition to the authors’ conclusions, the phenotype of the patient’s heterozygous brother is also illuminating. The brother’s vitamin D–binding protein levels were approximately 50% lower and 25(OH)D levels approximately 35% lower than those of his unaffected sister with two intact GC alleles. Furthermore, his 25(OH)D levels (approximately 13 ng per milliliter) were well below thresholds for diagnosis of vitamin D sufficiency. Despite very low 25(OH)D levels in the hemizygous brother, his free 25(OH)D levels were within normal limits and he had no signs of abnormal calcium homeostasis (i.e., normal parathyroid hormone [PTH] level) or bone mineralization deficits. These findings have important implications for acquired states of vitamin D–binding protein deficiency commonly seen in acute illness (due to actin binding and accelerated clearance from the circulation).1 We investigated vitamin D status in 25 consenting adults with acute critical illness admitted to a hospital intensive care unit and measured their total 25(OH)D and vitamin D–binding protein by mass spectrometry over a period of 2 to 7 days. The mean age of the patients was 67 years (interquartile range, 57 to 77); 14 (56%) were male, 23 (92%) were white, and 2 identified themselves as being of Asian descent. Admission diagnoses were varied and included sepsis, respiratory failure, myocardial infarction, acute pancreatitis, small-bowel ischemia, and acute kidney injury. Inspection of serum vitamin D–binding protein and 25(OH)D levels within individual patients over time revealed that changes in vitamin D–binding protein paralleled those in 25(OH)D (Fig. 1A), but day-to-day changes in directly measured free 25(OH)D remained comparatively stable. Repeated measures analysis confirmed that changes in vitamin D–binding protein correlated with changes in 25(OH)D between patients (repeated-measures correlation, 0.81; P = 0.002), and vitamin D– binding protein and 25(OH)D levels at all time points were strongly correlated (Fig. 1B), with no correlation between 25(OH)D and PTH (repeated measures correlation, −0.10; P = 0.35). Moreover, mean (±SD) levels of PTH, calcium, and free 25(OH)D were normal (58±44 pg per milliliter, 8.5±0.9 mg per deciliter [2.12±0.22 mmol per liter], and 9.2±6.9 pg per milliliter, respectively), similar to those reported in patients with liver cirrhosis.2 Animal models3 and persons2 with genetic or acquired deficiency of vitamin D–binding protein provide excellent examples of the free-hormone hypothesis at work. Namely, they suggest that the unbound subset of 25(OH)D is the form that maintains homeostasis of bone and mineral metabolism. Our collective findings imply that in healthy states in which vitamin D–binding protein levels are unchanged, total 25(OH)D correlates with free 25(OH)D4; however, in critical illness or other chronic inflammatory states in which vitamin D–binding protein is decreased, 25(OH)D levels are largely determined by vitamin D–binding protein levels and only modestly correlate with free 25(OH)D. Analogous to evaluation of thyroid function (measuring free T4 instead of total T4), clinical sufficiency of 25(OH)D in sick patients is best determined by methods that measure the unbound fraction.

Figure 1:

Vitamin D Binding-Protein and 25-Hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) in Patients Admitted to an Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Panel A shows changes over time in levels of vitamin D binding-protein, total 25(OH)D, and directly measured free 25(OH)D in 3 patients admitted to an ICU. Panel B shows the Pearson’s correlation coefficient between serum total 25(OH)D and vitamin D-binding protein levels n 25 ICU patients at all time points sampled.

Acknowledgements:

This study was supported by grant R01 DK094486 from the National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure Statement: Drs. Berg, Karumanchi, and Thadhani report being named coinventors on a patent (WO2014179737A3) on assays and methods of treatment relating to vitamin D insufficiency that is held by Massachusetts General Hospital. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this letter was reported.

REFERENCES CITED

- 1.Meier U, Gressner O, Lammert F, Gressner AM. Gc-globulin: roles in response to injury. Clin Chem. 2006;52(7):1247–53. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.065680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bikle DD, Halloran BP, Gee E, Ryzen E, Haddad JG. Free 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels are normal in subjects with liver disease and reduced total 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. J Clin Invest. 1986;78(3):748–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI112636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Safadi FF, Thornton P, Magiera H, Hollis BW, Gentile M, Haddad JG, Liebhaber SA, Cooke NE. Osteopathy and resistance to vitamin D toxicity in mice null for vitamin D binding protein. J Clin Invest. 1999;103(2):239–51. doi: 10.1172/JCI5244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz JB, Gallagher JC, Jorde R, Berg V, Walsh J, Eastell R, Evans AL, Bowles S, Naylor KE, Jones KS, Schoenmakers I, Holick M, Orwoll E, Nielson C, Kaufmann M, Jones G, Bouillon R, Lai J, Verotta D, Bikle D. Determination of Free 25(OH)D Concentrations and Their Relationships to Total 25(OH)D in Multiple Clinical Populations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(9):3278–88. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-00295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]