Abstract

Avian influenza A viruses (AIVs) can occasionally transmit to mammals and lead to the development of human pandemic. A species of mammal is considered as a mixing vessel in the process of host adaptation. So far, pigs are considered as a plausible intermediate host for the generation of human pandemic strains, and are labelled ‘mixing vessels’. In this study, through the analysis of two professional databases, the Influenza Virus Resource of NCBI and the Global Initiative on Sharing Avian Influenza Data (GISAID), we found that the species of mink (Neovison vison) can be infected by more subtypes of influenza A viruses with considerably higher α-diversity related indices. It suggested that the semiaquatic mammals (riverside mammals), rather than pigs, might be the intermediate host to spread AIVs and serve as a potential mixing vessel for the interspecies transmission among birds, mammals and human. In epidemic areas, minks, possibly some other semiaquatic mammals as well, could be an important sentinel species for influenza surveillance and early warning.

Subject terms: Influenza virus, Ecological epidemiology

Introduction

Influenza A viruses (IAVs) belong to the family Orthomyxoviridae. Based on the antigenic properties of two surface glycoproteins hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), IAVs are clustered into 18 HA (H1–H18) and 11 NA (N1–N11) subtypes1–3. The ecology of IAVs is complicated involving multiple host species and viral genes. So far, except that H17, H18, N10 and N11 were restrictively identified from bat samples in forms of H17N10 and H18N114, all other subtypes viruses can circulate in avian species1,2,5, aquatic birds (or waterfowls) in particular, which are therefore considered the natural reservoir of IAVs6–11. Occasionally, avian influenza A viruses (AIVs) can transmit to mammals from avian species, which may lead to the development of human pandemic strains by direct or indirect transmission.

A successful transmission between species depends on both host and virus factors, and some period of adaptation of the virus to the new species. Many host factors interacting with the component proteins of IAVs have been identified and their role in the host range expansion and interspecies transmission has been clearly stated8,9. Several viral proteins of IAVs are also known to be responsible for host adaptation or interspecies transmission6,12–18, of which HA membrane protein is the major determinant for crossing the species barrier8,19,20. Binding to sialic acid receptor, HA initiates fusion of the viral envelope with the host cell membrane5,21,22. The sialic acid receptor can be linked to galactose by α2,6-linkages (SAα2,6 Gal) or α2,3-linkages (SAα2,3 Gal). It is generally believed that HAs of AIVs preferentially bind to SAα2,3 Gal on intestinal epithelial cells of aquatic birds, whereas the HAs of human IAVs prefer SAα2,6 Gal on tracheal epithelium. The adaptation of AIVs to human or other mammalian hosts (mammalian influenza A viruses are abbreviated as MIVs in this study) is connected with a switch in HA ability to bind SAα2,6 Gal instead of SAα2,3 Gal20,23–28. In pig tracheal epithelium, there exist both SAα2,3 Gal and SAα2,6 Gal; HA of both AIVs and human influenza viruses may find the receptors. Given these features, pigs are considered as a plausible intermediate host for the generation of human pandemic strains by gene reassortment5,29–35. This potential to generate novel influenza viruses has resulted in swine being labelled ‘mixing vessels’36–38.

The variety of AIVs combined with the high ability of adaptation constitutes the main risk factor for crossing the species barriers, but it is difficult to predict which virus might induce a human pandemic8,39. In order to identify precursor viruses of potential pandemics, an active surveillance and collecting of AIVs from different species, especially the species that can be served as mixing vessels, are crucial. In this study, through screening the host originations of all subtypes of HA and NA sequences available in public databases, we analyzed their host tropisms and attempted to provide the target hosts other than pigs for surveillance of influenza pandemics.

Methods

Screen and count the host originations of IAVs

As mentioned above, HA can initiate fusion of the viral envelope with the host cell membrane, which is the prerequisite for viral replication and transmission. While the balance between HA receptor-binding affinity and NA receptor destroying activity is critical for the efficient growth of IAVs, NA also contributes to influenza virus species specificity40,41. Therefore, HA and NA nucleotide sequences were analyzed in this study.

The host originations of HA and NA nucleotide sequences were screened and counted in two databases, the Influenza Virus Resource of NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/FLU/aboutdatabase.html) and the Global Initiative on Sharing Avian Influenza Data (GISAID, http://platform.gisaid.org/epi3/frontend) by the end of March 12, 2018. NCBI was used as the main database while the latter was used as a supplementary under the set of only GISAID uploaded isolates. Two screen strategies were engaged in this study. Considering that large amount of isolates of IAV were not sequenced and submitted completely to the databases, the host originations of HA and NA sequences were screened separately. The other strategy that the host originations were screened and counted by subtypes of HxNy (x = 1, 2, 3…18, y = 1, 2, 3…11), was carried out when the preferential HA-NA balances of IAVs were taken into account.

Measure for α-diversity indices of IAVs established from mammalian hosts

Microenvironment in host animal provides the material basis for the growth and proliferation of viruses; at the same time, antibodies and receptor types can also restrict the IAV infections. Relationship or interaction between the microenvironment of a host and viruses is somewhat similar to that between ecological environment and the populations living in it. When a host can be infected with different subtypes of IAVs, it is more likely to be a mixing vessel or natural reservoir for the viruses. Each subtype of HA or NA was regarded as a species population, while the sequence frequencies recorded in the databases were regarded as the observed individuals of the corresponding populations. We can use use some ecological indices such as species diversity, richness, and evenness of IAVs within a species of mammalian host to measure the complexity of a relationship between host microenvironment and IAVs42:

- Margalef (1951, 1957, and 1958) index (focuses on richness)

S is the total subtype number of HA or NA that established from a species of mammalian hosts, and N is the total sequence frequency of HA or NA established from this host species. - Simpson’s index (focuses on dominance)

Pi refers to the ratios of the number of ni subtype of HA or NA to the total sequence frequency of HA or NA established from a species of mammalian hosts, i.e., Pi = ni/N. - Shannon-wiener diversity index

The meaning of Pi is the same as above. Pielou evenness index

H is the observed species diversity index, which equals to Shannon-wiener index H′, i. e., H = H′ = −ΣPilnPi.

Sequence analyses for focused HAs and NAs of AIVs

A species of mammalian host may have the tendency to become a mixing vessel or natural reservoir for human IAVs or other MIVs if they can be infected with a large number of subtypes of IAVs, AIVs in particular. We further studies the species of mammalian hosts infected with the IAVs that had the highest richness, diversities, and evenness. After consulting the information in GenBank and GISAID in detail, tracking references, and removing repeated sequence submissions, each of the HA and NA sequences of AIVs was analyzed by using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST, https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) with the set of Max target sequences being 1000, and then, every 1000 sequences were downloaded to a local computer. After alignment by FFT-NS-2 methods in multiple alignment program for amino acid or nucleotide sequences (MAFFT version 7, https://mafft.cbrc.jp), they were translated and compared by the MegAlign module of the Lasergene 7.0 software. For HAs, the parts of sequences encoding the signal peptides were cut off beforehand corresponding to each reference sequence of the respective subtype (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq). The comparisons were carried out between each sequence of HA or NA and its 999 most similar sequences, and variations on the sites that are known as being relevant to the host tropism of IAVs were focused on3,23,24,39,43–51.

Ethics approval

This study is a serial of phylogenetic analyses based on large scale of existing gene sequences; all these sequences can be searched and downloaded from two public databases, the NCBI Influenza Virus Sequence Database and the Global Initiative on Sharing Avian Influenza Data (GISAID) database. No institutional review board approval was required from the research ethics committee of School of Public Health, Fudan University, and animals’ ethics approval was applicable neither.

Results

From H1 to H18, and from N1 to N11, the ratios of sequences with mammalian host origination to those with avian host origination are displayed in Supplementary Figs 1, 2 and Supplementary Tables 1–3. Except for 65 sequences (33 HA and 32 NA) that were labeled as mammalian origination but no definite species records, 26 species of nonhuman mammal hosts of IAVs were retrieved from the databases. Further checking confirmed that the hosts labeled as feline are cats rather than the taxonomic family of feline. Bovine and mouse had entries but no sequence records. Thus, 23 species of nonhuman mammals were included for the subsequent analysis.

The mammalian species of bat, boar, camel, canine, cat, equine, ferret, mink, muskrat, seal, swine, and whale can be infected by more than one subtype of IAVs. For a long time, swine is considered as a mixing vessel for reassortment or recombination of IAVs. Although isolates established from swine are indeed abundant, the subtypes of them are restricted mainly to MIVs, of which, H1, H3, N1 and N2 account for the overwhelming majority (99·18% of HAs and 99·58% of NAs). The α-diversity related indices including the Shannon-wiener index, the Simpson’s diversity index, the Margalef richness, and the Pielou evenness and they were 0.88, 0.38, 0.94 and 0.27 for HAs that derived from swine, and were 1·00, 0·49, 0·64, and 0·36 for NAs. For HAs, the indices were even lower in swine as compared with those in cat, ferret, camel, bat and muskrat, and for NAs, they were not higher in swine than those in cat and camel. It seemed that swine can only be infected with limited subtypes of IAVs, and sporadic infections caused by subtypes other than H1N1, H1N2 and H3N2 occasionally occurred by chance of accidental spillover. The same happened in dogs and horses. Although the sequences of HA and NA established from them were abundant enough, the subtypes of IAVs were restricted to one or more specific subtypes of MIVs, of which H3N8 and H3N2 accounted for the overwhelming majority.

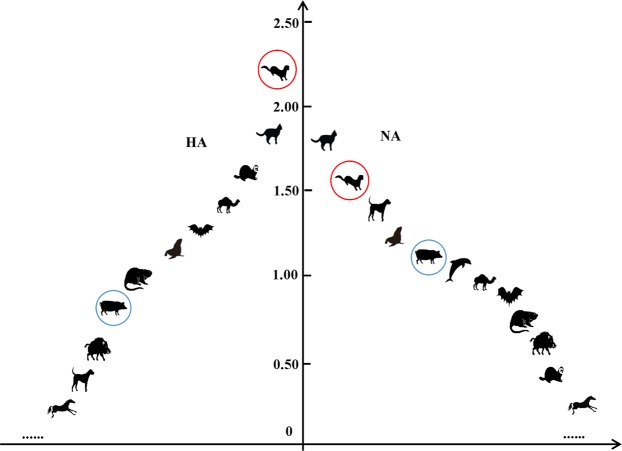

Interestingly, a neglected mammalian host, mink, was infected by more subtypes of IAVs. Isolates including both MIVs (H3N2 and H1N1) and AIVs (H5N1, H9N2, and H10N4), had considerably higher α-diversity related indices. The Shannon-wiener index, the Simpson’s diversity index, the Margalef richness, and the Pielou evenness were 2·20, 0·77, 1·56, and 0·95 for HAs, and 1·46, 0·61, 0·81, and 0·92 for NAs. The α-diversity related indices of HAs and NAs derived from different mammalian hosts are displayed in Table 1 and Fig. 1.

Table 1.

The α diversity related indices of HA and NA derived from mammalian hosts.

| HA | NA | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ds | Dr | H′ | E | S | N | Ds | Dr | H | E | S | N | |

| mink | 0·77 | 1·56 | 2·20 | 0·95 | 5 | 13 | 0·61 | 0·81 | 1·46 | 0·92 | 3 | 12 |

| cat | 0·68 | 0·85 | 1·79 | 0·90 | 4 | 34 | 0·63 | 0·56 | 1·51 | 0·95 | 3 | 36 |

| ferret | 0·62 | 1·14 | 1·59 | 0·80 | 4 | 14 | 0·26 | 0·39 | 0·62 | 0·62 | 2 | 13 |

| camel | 0·50 | 1·44 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 2 | 2 | 0·50 | 1·44 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 2 | 2 |

| bat | 0·48 | 0·62 | 0·97 | 0·97 | 2 | 5 | 0·48 | 0·62 | 0·97 | 0·97 | 2 | 5 |

| muskrat | 0·44 | 0·91 | 0·92 | 0·92 | 2 | 3 | 0·44 | 0·91 | 0·92 | 0·92 | 2 | 3 |

| swine | 0·38 | 0·94 | 0·88 | 0·27 | 10 | 13841 | 0·49 | 0·64 | 1·00 | 0·36 | 7 | 11747 |

| seal | 0·30 | 0·92 | 0·97 | 0·42 | 5 | 78 | 0·57 | 1·36 | 1·38 | 0·72 | 5 | 19 |

| boar | 0·28 | 0·56 | 0·65 | 0·65 | 2 | 6 | 0·44 | 0·56 | 0·92 | 0·92 | 2 | 6 |

| canine | 0·09 | 0·64 | 0·32 | 0·14 | 5 | 520 | 0·59 | 0·38 | 1·40 | 0·88 | 3 | 188 |

| equine | 0·01 | 0·36 | 0·06 | 0·03 | 4 | 4075 | 0·10 | 0·51 | 0·32 | 0·16 | 4 | 361 |

| whale | 0 | 0 | 0 | / | 1 | 2 | 0·50 | 1·44 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 2 | 2 |

| tiger | 0 | 0 | 0 | / | 1 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | / | 1 | 17 |

| civet | 0 | 0 | 0 | / | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | / | 1 | 2 |

| raccoon dog | 0 | 0 | 0 | / | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | / | 1 | 2 |

| cheetah | 0 | 0 | 0 | / | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | / | 1 | 2 |

| anteater | 0 | / | 0 | / | 1 | 1 | 0 | / | 0 | / | 1 | 1 |

| leopard | 0 | 0 | 0 | / | 1 | 6 | 0 | / | 0 | / | 1 | 1 |

| lion | 0 | / | 0 | / | 1 | 1 | 0 | / | 0 | / | 1 | 1 |

| marten | 0 | / | 0 | / | 1 | 1 | 0 | / | 0 | / | 1 | 1 |

| panda | 0 | / | 0 | / | 1 | 1 | 0 | / | 0 | / | 1 | 1 |

| pika | 0 | 0 | 0 | / | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | / | 1 | 6 |

| bear | 0 | / | 0 | / | 1 | 1 | 0 | / | 0 | / | 1 | 1 |

Figure 1.

Shannon-wiener index of IAVs’ HA and NA derived from different mammals*. *Only those are greater than zero are shown. As for HA (left side), from high to low are mink, cat, ferret, camel, bat, seal, muskrat, swine, boar, canine, equine, in turn; as for NA (right side), they are cat, mink, canine, seal, swine, whale, camel, bat, muskrat, boar, ferret, equine, respectively.

Fourteen HA and thirteen NA sequences were found to be established from minks, of which nine pairs of HA and NA were of the typical AIVs, including two H10N4, three H5N1, and four H9N2. BLAST analysis showed that one variation of G212R in two strains of H10N4, and one variation of N173H in the isolate China/01/2014 (H9N2) might involve the binding epitopes of the globular head of HA protein, and the rest variations did not site in the known binding epitopes of the host cell receptor (Table 2).

Table 2.

Variations of HAs and NAs of AIVs established from minks compared to majorities.

| Strain | HA | NA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access No. | Variation | Access No. | Variation | |

| Sweden/3900/1984(H10N4) | GQ176144 | E23V, A92T, E97G, I112T, T117A, N137D, L143V, S150D, G212R, L245R, V525A | GQ176142 | E75D, R79S, N/T271P, V/E328M |

| Sweden/E12665/1984(H10N4) | M21646 | the same as above | AY207530 | the same as above |

| Sweden/V907/2006(H5N1) | EU889075 | E502G | EU889101 | / |

| Shandong/F6/2013(H9N2) | KM576103 | K276E, G294E, D366G, Y414C, S486P, E501G | KM576104 | P55S, N61S, N218H, K293N |

| Shandong/F10/2013(H9N2) | KM576111 | the same as above | KM576112 | the same as above |

| China/01/2014(H9N2) | MF996800 | N173H | MF996801 | K77N, K196T, G245E, G267R, N/D325S |

| China/02/2014(H9N2) | MF996789 | V(−14)I, G230D, R537G | MF996791 | Q90K, K/N140R, I202V, Y281H, N355D, S397N |

| China/G/2015(H5N1) | KX867865 | I(−12)T, K162E, P194L, I375M, E502G | KX867867 | Q45H, F302L |

| China/XB/2015(H5N1) | KX867873 | I374M | KX867875 | / |

Discussion

Swine is an important host for IAVs for reasons of being involved in genetic reassortment and interspecies transmission. In swine population, H1N1, H3N2, H1N2 viruses are circulating worldwide, and most swine influenza viruses (SIVs) are reassortants originated from human, avian and swine influenza viruses24,52,53. However, our study indicated that the spillover infections of swine occurred only occasionally. Rare spillover infections were similar for dogs, horses and cats.

Remarkably, our results suggest that mink should be taken more seriously in influenza surveillance. Mink (Neovison vison) is a semiaquatic mammal (or riverside mammal, mammals occurring close to the water and sometimes within it, such as Neovison vison, Lutra lutra, Delphinidae, and Phocidae) species of the genus Mustela of the family Mustelidae; there are 15 subspecies of mink widely distributed in the Americas or being introduced into other continents54. IAVs including both AIVs (H9N2, H5N1, and H10N4) and MIVs (H3N2 and H1N1), were isolated from minks with the highest species/subtype diversities, richness and evenness. Influenza A has caused several outbreaks in minks55–58. The same strain of MIV or AIV can be repeatedly established during one outbreak55,58, and different subtypes of AIVs also can be isolated from an outbreak in the same period and same breeding farm59,60. All these testimonies prove the susceptibility of mink to IAVs and the transmission features within the populations. Peng et al. and Yu et al. have reported that receptors in tracheal epithelium of mink are mainly linked to SAα2,6 Gal, but receptors of SAα2,3 Gal and SAα2,6 Gal are detected equally or with predominance to SAα2,3 Gal in gastrointestinal mucosa of it58,61. As we know, HAs of AIVs preferential receptors of SAα2,3 Gal are coincidentally on intestinal epithelial cells of aquatic birds26,31,62. Such a molecular basis of the existence of both AIVs and MIVs specific receptors within minks, as well as their characteristic distribution, imply that minks not only could infect with MIVs by intra-tracheal inoculation or horizontal transmission from other minks within populations, but also could infect with AIVs either by eating (preying or feeding) on virus-infected birds or by faecal-oral route within habitat environment63,64. These findings suggest minks may be another intermediate host to spread the virus from wild waterfowls to human. Mink infection may contribute to the adaptation of AIVs to human and other mammals by genetic reassortment or other mechanisms.

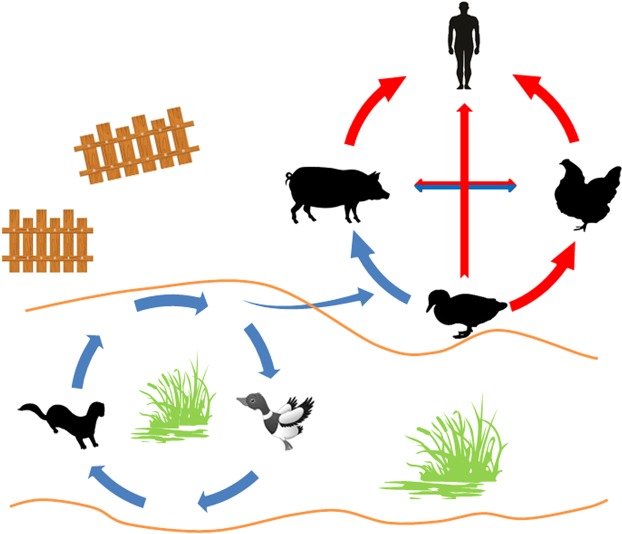

From the viewpoint of niche, habitats of riverside mammals such as minks and wild waterfowls overlap each other, which greatly facilitate the interspecies transmission among them. Possibly, some other species of riverside mammals, in addition to terrestrial and domesticated pigs, might also have this potential. Waterfowls have long been considered natural gene pools for IAVs. While the receptors on the surface of gastrointestinal mucosa can recur the infections caused by AIVs within waterfowls, minks may be of significance in sustaining IAVs’ genes and the species may be both a mixing vessel and natural reservoir for IAVs. Co-infection greatly increases the chances of generating novel viruses through genetic reassortment or recombination, which can introduce a novel subtype of IAV in human population. In a free stall barn system, usually in some areas of South Asia, Southeast Asia, Southern and Eastern China, the traditional methods of free-range or outdoor breeding always exacerbates the risk of infection of poultry and backyard livestock through contact with contaminated water or feces65–67. The emergence of novel IAVs can lead to a rapid epidemic within terrestrial animals or human. Circulation of IAVs among minks or other riverside mammals, waterfowl, domestic poultry, terrestrial mammals and human is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

The illustration of adaptation and transmission of Human AIVs. An adaptation from AIVs to human AIVs includes two circulations, the aquatic habitat circulation and the land habitat circulation. In the aquatic habitat circulation, AIVs are transmitting, mutating, and adapting between aquatic birds and minks (as well as other semiaquatic mammals). This adaptation may or may not change their infectivity to avian, but can significantly increase the infectivity to human and terrestrial mammals. Poultries such as duck, goose can be infected through contacting with epidemic water. In a free stall barn system, usually in some areas of South Asia, Southeast Asia, Southern and Eastern China, it will inevitably lead to a land habitat circulation including human beings. The blue pathway is transmitted by faecal-oral route, while the red one is transmitted by intra-tracheal inoculation. The conception for this scene is partly based on the observation of daily lives; e.g., in rural areas of South Asia, Southeast Asia, Southern and Eastern China, pigs and poultries, in particular chick, are often observed to eat each other’s feces. Pigs also eat duck feces, but ducks seldom eat pig feces; and partly based on the available reports, e.g., human infected by a human-adapted AIV from the live poultry market was often reported in China.

This study demonstrates that mink (Neovison vison) might be a potential mixing vessel or intermediate host for the generation of novel human IAVs. Minks, possibly some other semiaquatic mammals (riverside mammals) as well, might play a pivotal role in the process of adapting and transmitting AIVs to human and other terrestrial animals. The significances of mink and other riverside mammal hosts in influenza surveillance and early warning should be paid an attention. In epidemic areas, mink should be considered as one of important sentinel species of hosts for influenza surveillance.

There are several limitations of our study should be mentioned. In this study, we only used the existing databases with no additional laboratory evidence. Secondly, the number of IAVs established from the mammalian species here including those in minks is still small. Hence, our conclusions need to be consolidated.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81872673), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2017YFC1200203), the Original Research Support Project of Fudan University (Grant No. IDF201011), the Fourth Round of Three-Year Public Health Action Plan of Shanghai (Grant Nos 15GWZK0101 and 15GWZK0202). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. We acknowledge the contributions of scientists and researchers from all over the world for depositing the genomic sequences of IAVs in NCBI Flu database and Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) EpiFlu™. We acknowledge Dr. Guozhong He for kindly providing us the computing platform; Dr. He is a research professorship at School of Public Health, Kunming Medical University.

Author Contributions

C.X., L.S., J.X., P.Z. and Y. Chen co-wrote the first draft of the paper; all other authors contributed substantial amendments and critical review. C.X., P.Z., L.S., J.X. and C.W. screened and counted the sequences in two public databases. C.X., J.X., L.C., P.Y. and Q.Y. did the ecological measurement. C.X., L.C., J.X. and C.W. produced tables and figures. C.X., Q.J., G.Z., Y. Chen, L.J., H.Y. and Y. Cheng undertook systematic reviews; C.X. and Q.J. led the systematic reviews.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ping Zhao, Lingsha Sun and Jiasheng Xiong contributed equally.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-48255-5.

References

- 1.Kalthoff D, Globig A, Beer M. Highly pathogenic) avian influenza as a zoonotic agent. Vet. Microbiol. 2010;140:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan BS, Webby RJ. The avian and mammalian host range of highly pathogenic avian H5N1 influenza. Virus Res. 2013;178:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schrauwen EJ, Fouchier RA. Host adaptation and transmission of influenza A viruses in mammals. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2014;3:e9. doi: 10.1038/emi.2014.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tong S, et al. New world bats harbor diverse influenza A viruses. PLoS. Pathog. 2013;9:e1003657. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imai M, Kawaoka Y. The role of receptor binding specificity in interspecies transmission of influenza viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012;2:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salomon R, et al. The polymerase complex genes contribute to the high virulence of the human H5N1 influenza virus isolate A/Vietnam/1203/04. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:689–697. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JK, Negovetich NJ, Forrest HL, Webster RG. Ducks: the “Trojan horses” of H5N1 influenza. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses. 2009;3:121–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2009.00084.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma W, et al. The role of swine in the generation of novel influenza viruses. Zoonoses Public Health. 2009;56:326–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2008.01217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webster RG, Bean WJ, Gorman OT, Chambers TM, Kawaoka Y. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiol. Rev. 1992;56:152–179. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.152-179.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fouchier RA, et al. Characterization of a novel influenza A virus hemagglutinin subtype (H16) obtained from black-headed gulls. J. Virol. 2005;79:2814–2822. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.2814-2822.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krauss S, et al. The enigma of the apparent disappearance of Eurasian highly pathogenic H5 clade 2.3.4.4 influenza A viruses in North American waterfowl. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:9033–9038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608853113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scholtissek C, Burger H, Kistner O, Shortridge KF. The nucleoprotein as a possible major factor in determining host specificity of influenza H3N2 viruses. Virology. 1985;147:287–294. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90131-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tian SF, et al. Nucleoprotein and membrane protein genes are associated with restriction of replication of influenza A/Mallard/NY/78 virus and its reassortants in squirrel monkey respiratory tract. J. Virol. 1985;53:771–775. doi: 10.1128/jvi.53.3.771-775.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snyder MH, Buckler-White AJ, London WT, Tierney EL, Murphy BR. The avian influenza virus nucleoprotein gene and a specific constellation of avian and human virus polymerase genes each specify attenuation of avian-human influenza A/Pintail/79 reassortant viruses for monkeys. J. Virol. 1987;61:2857–2863. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.9.2857-2863.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Subbarao EK, London W, Murphy BR. A single amino acid in the PB2 gene of influenza A virus is a determinant of host range. J. Virol. 1993;67:1761–1764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.1761-1764.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown EG. Influenza virus genetics. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2000;54:196–209. doi: 10.1016/S0753-3322(00)89026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatta M, Gao P, Halfmann P, Kawaoka Y. Molecular basis for high virulence of Hong Kong H5N1 influenza A viruses. Science. 2001;293:1840–1842. doi: 10.1126/science.1062882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scholtissek C, Stech J, Krauss S, Webster RG. Cooperation between the hemagglutinin of avian viruses and the matrix protein of human influenza A viruses. J. Virol. 2002;76:1781–1786. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.4.1781-1786.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glaser L, et al. A single amino acid substitution in 1918 influenza virus hemagglutinin changes receptor binding specificity. J. Virol. 2005;79:11533–11536. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11533-11536.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oshansky CM, et al. Avian influenza viruses infect primary human bronchial epithelial cells unconstrained by sialic acid alpha2,3 residues. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers GN, et al. Single amino acid substitutions in influenza haemagglutinin change receptor binding specificity. Nature. 1983;304:76–78. doi: 10.1038/304076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogers GN, Pritchett TJ, Lane JL, Paulson JC. Differential sensitivity of human, avian, and equine influenza A viruses to a glycoprotein inhibitor of infection: selection of receptor specific variants. Virology. 1983;131:394–408. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90507-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matrosovich M, Stech J, Klenk HD. Influenza receptors, polymerase and host range. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2009;28:203–217. doi: 10.20506/rst.28.1.1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu D, Liu X, Yan J, Liu WJ, Gao GF. Interspecies transmission and host restriction of avian H5N1 influenza virus. Sci. China C Life Sci. 2009;52:428–438. doi: 10.1007/s11427-009-0062-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baum LG, Paulson JC. Sialyloligosaccharides of the respiratory epithelium in the selection of human influenza virus receptor specificity. Acta Histochem. 1990;40(Suppl):35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki Y. Sialobiology of influenza: molecular mechanism of host range variation of influenza viruses. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005;28:399–408. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shinya K, et al. Avian flu: influenza virus receptors in the human airway. Nature. 2006;440:435–436. doi: 10.1038/440435a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thongratsakul S, et al. Avian and human influenza A virus receptors in trachea and lung of animals. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2010;28:294–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuki T, et al. Swine influenza virus strains recognize sialylsugar chains containing the molecular species of sialic acid predominantly present in the swine tracheal epithelium. FEBS. Lett. 1997;404:192–196. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito T, et al. Differences in sialic acid-galactose linkages in the chicken egg amnion and allantois influence human influenza virus receptor specificity and variant selection. J. Virol. 1997;71:3357–3362. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3357-3362.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ito T, et al. Molecular basis for the generation in pigs of influenza A viruses with pandemic potential. J. Virol. 1998;72:7367–7373. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7367-7373.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stevens J, et al. Glycan microarray analysis of the hemagglutinins from modern and pandemic influenza viruses reveals different receptor specificities. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;355:1143–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Poucke SG, Nicholls JM, Nauwynck HJ, Van Reeth K. Replication of avian, human and swine influenza viruses in porcine respiratory explants and association with sialic acid distribution. Virol. J. 2010;7:38. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taubenberger JK, Kash JC. Influenza virus evolution, host adaptation, and pandemic formation. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:440–451. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelli RK, et al. Comparative distribution of human and avian type sialic acid influenza receptors in the pig. BMC Vet. Res. 2010;6:4. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scholtissek C. Source for influenza pandemics. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1994;10:455–458. doi: 10.1007/BF01719674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scholtissek C, Burger H, Bachmann PA, Hannoun C. Genetic relatedness of hemagglutinins of the H1 subtype of influenza A viruses isolated from swine and birds. Virology. 1983;129:521–523. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garten RJ, et al. Antigenic and genetic characteristics of swine-origin 2009 A(H1N1) influenza viruses circulating in humans. Science. 2009;325:197–201. doi: 10.1126/science.1176225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Urbaniak K, Kowalczyk A, Markowska-Daniel I. Influenza A viruses of avian origin circulating in pigs and other mammals. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2014;61:433–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. Host range restriction and pathogenicity in the context of influenza pandemic. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006;12:881–886. doi: 10.3201/eid1206.051336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Landolt GA, Olsen CW. Up to new tricks - a review of cross-species transmission of influenza A viruses. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2007;8:1–21. doi: 10.1017/S1466252307001272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun, R. Y. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Population. In: Sun, R. Y., ed. Principles of Animal Ecology, 3rd Edition. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press, pp44–86 (2001, in Chinese).

- 43.Liu, J. H. et al. The difference of the hemagglutinin of H9N2 chicken influenza viruses isolated in China and Korea. Acta Veterinaria et Zootechnica Sinica35, 79–82 (2004, in Chinese).

- 44.Zhang, J. R., Yao, Q., Wei, D. B. & Lei, F. M. Study on the characteristics of the human-infected avian influenza H5N1 HA subtype in China between 2006 and 2007. Ningxia Med. J. 31, 193–195 (2009, in Chinese).

- 45.Chen, L., Liu, S. C., Zhao, J., Wang, C. Q. & Wang, Z. L. Characteristics of pathogenic and HA antigenic variation of H9N2 subtybe avian influenza viruses isolated from 1998 to 2008 in China. Scientia Agricultura Sinica44, 5100–5107 (2011, In Chinese).

- 46.Tang, S. & Li, T. X. Molecular characteristics analysis and pathogenicity study of H5N1/H7N8/H10N4 avian influenza virus. Graduate School of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Dissertation (2007, In Chinese).

- 47.Xiao, C. C. & Liao, M. The mechanism of mammalian adaptation of the novel H10N8 avian influenza virus. South China Agricultural University, Dissertation (2016, In Chinese).

- 48.Yang, C. R., Dong, S. Z., Yang, Z. Z. & Ni, J. Molecular basis on pathogenicity of avian influenza virus. Progress in veterinary medicine31, 92–96 (2010, In Chinese).

- 49.Xu, X. L., Bao, H. M., Chen, H. L. & Wang, X. R. Review: key amino acid sites affecting the pathogenicity and transmission of avian influenza virus. Chinese journal of preventive veterinary medicine36, 165–168 (2014, In Chinese).

- 50.Dong, F.Y., Zheng, Q. & Fang, S. S. Review: molecular mechanism of cross-species transmission of influenza A virus. J. Trop. Med. 15, 1442–1445 (2015, In Chinese).

- 51.Zhang, M. M. et al. Progress on molecular basis of host specificity and pathogenicity of avian influenza viruses. Progress in veterinary medicine37, 102–105 (2016, In Chinese).

- 52.Kawaoka Y, Krauss S, Webster RG. Avian-to-human transmission of the PB1 gene of influenza A viruses in the 1957 and 1968 pandemics. J. Virol. 1989;63:4603–4608. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.11.4603-4608.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Reeth K. Avian and swine influenza viruses: our current understanding of the zoonotic risk. Vet. Res. 2007;38:243–260. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2006062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cai Z, et al. The first draft reference genome of the American mink (Neovison vison) Sci. Rep. 2017;7:14564. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15169-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klingeborn B, Englund L, Rott R, Juntti N, Rockborn G. An avian influenza A virus killing a mammalian species–the mink. Brief report. Arch. Virol. 1985;86:347–351. doi: 10.1007/BF01309839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kiss I, et al. Molecular characterization of highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza viruses isolated in Sweden in 2006. Virol. J. 2008;5:113. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gagnon CA, et al. Characterization of a Canadian mink H3N2 influenza A virus isolate genetically related to triple reassortant swine influenza virus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47:796–799. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01228-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peng L, et al. Molecular characterization of H9N2 influenza virus isolated from mink and its pathogenesis in mink. Vet. Microbiol. 2015;176:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jiang W, et al. Characterization of H5N1 highly pathogenic mink influenza viruses in eastern China. Vet. Microbiol. 2017;201:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xue R, et al. H9N2 influenza virus isolated from minks has enhanced virulence in mice. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018;65:904–910. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yu M, et al. Expression of inflammation-related genes in the lung of BALB/c mice response to H7N9 influenza A virus with different pathogenicity. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2016;205:501–509. doi: 10.1007/s00430-016-0466-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ito T, et al. Receptor specificity of influenza A viruses correlates with the agglutination of erythrocytes from different animal species. Virology. 1997;227:493–499. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reperant LA, Kuiken T, Osterhaus AD. Adaptive pathways of zoonotic influenza viruses: from exposure to establishment in humans. Vaccine. 2012;30:4419–4434. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reperant LA, Rimmelzwaan GF, Kuiken T. Avian influenza viruses in mammals. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2009;28:137–159. doi: 10.20506/rst.28.1.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shortridge KF, Stuart-Harris CH. An influenza epicentre? Lancet. 1982;2:812–813. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(82)92693-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Scholtissek C, Naylor E. Fish farming and influenza pandemics. Nature. 1988;331:215. doi: 10.1038/331215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Webby RJ, Webster RG. Emergence of influenza A viruses. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2001;356:1817–1828. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.