Abstract

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are prominent components of tumor stroma that promotes tumorigenesis. Many soluble factors participate in the deleterious cross-talk between TAMs and transformed cells; however mechanisms how tumors orchestrate their production remain relatively unexplored. c-Myb is a transcription factor recently described as a negative regulator of a specific immune signature involved in breast cancer (BC) metastasis. Here we studied whether c-Myb expression is associated with an increased presence of TAMs in human breast tumors. Tumors with high frequency of c-Myb-positive cells have lower density of CD68-positive macrophages. The negative association is reflected by inverse correlation between MYB and CD68/CD163 markers at the mRNA levels in evaluated cohorts of BC patients from public databases, which was found also within the molecular subtypes. In addition, we identified potential MYB-regulated TAMs recruiting factors that in combination with MYB and CD163 provided a valuable clinical multigene predictor for BC relapse. We propose that identified transcription program running in tumor cells with high MYB expression and preventing macrophage accumulation may open new venues towards TAMs targeting and BC therapy.

Subject terms: Breast cancer, Cancer microenvironment, Tumour biomarkers

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common malignant disease in women, with one million new cases diagnosed worldwide per year. Tumors engage various components of immune system throughout their evolution. Among these components, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) represent a major cell population constituting up to 50% of tumor mass1,2. TAMs, a macrophage population recruited and educated by tumor cells, resemble M2-like macrophages3. Unlike M1-like macrophages exhibiting pro-inflammatory and anti-cancer functions, the M2-like macrophages are immunosuppressive cells contributing to the matrix-remodeling, angiogenesis, chemoresistance and metastasis and hence favor tumor growth and dissemination4–9. The direct correlation between high amount of TAMs and worse prognosis/low survival rate of breast cancer patients was demonstrated and TAMs depletion was suggested as therapeutic strategy in breast cancer10–14. Less known are mechanisms of attraction and polarization of TAMs inside the malignant tissue. Several soluble factors of tumor microenvironment, secreted by tumor and stromal cells, such as CCL2 (MCP1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; C-C motif chemokine ligand 2), CSF1 (colony-stimulating factor 1), CSF2 (colony-stimulating factor 2), VEGFA (vascular endothelial growth factor A), CCL18 (C-C motif chemokine ligand 18), CCL20 (C-C motif chemokine ligand 20), and CXCL12 (C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12) are doubtless involved in the processes of monocytes recruitment and their polarization at the tumor sites1,15. However, how the cytokine production by tumor cells orchestrates the tumor microenvironment, including TAMs remains rather unclear.

The c-Myb protein encoded by MYB gene, is transcription regulator required for the maintenance of stem cells in bone marrow, colon epithelia, and neurogenic niches in adult brain16. Its expression has been linked with leukemias and epithelial cancer, most notably colon and breast cancers. c-Myb was described to have oncogenic and tumor suppressor activities in BCs17–21. However, clinical data have unanimously associated MYB overexpression with a good prognosis for BC patients19,20,22. Better survival rate has been linked with a lower risk of lung metastasis in patients with high MYB expression23.

Recently, we have described the functional association between Ccl2 and c-Myb in regulation of the monocyte-assisted extravasation capacity of breast tumor cells. c-Myb efficiently suppressed the inflammatory circuit including the Ccl2 chemokine in mouse models of BC and attenuated tumor dissemination suggesting that c-Myb-regulated transcriptional program may affect recruitment and/or activity of immune cells23. Because Ccl2 is a well-known monocyte/macrophage recruiting factor in BC24–28, we explored an association between c-Myb immunostaining in tumor cells and TAMs infiltration in clinical specimens of breast carcinomas. While causal interdependence between TAMs and cancer progression has been established, the molecular mechanisms linking oncogenic mutations in the tumor cells to the modulation of the microenvironment remain to be elaborated. The identification of a tumor-expressed transcription factor program in association with TAMs abundance may help to find a valuable multigene biomarker for the assessment of a clinical outcome that is superior to TAMs enumeration per se.

Results

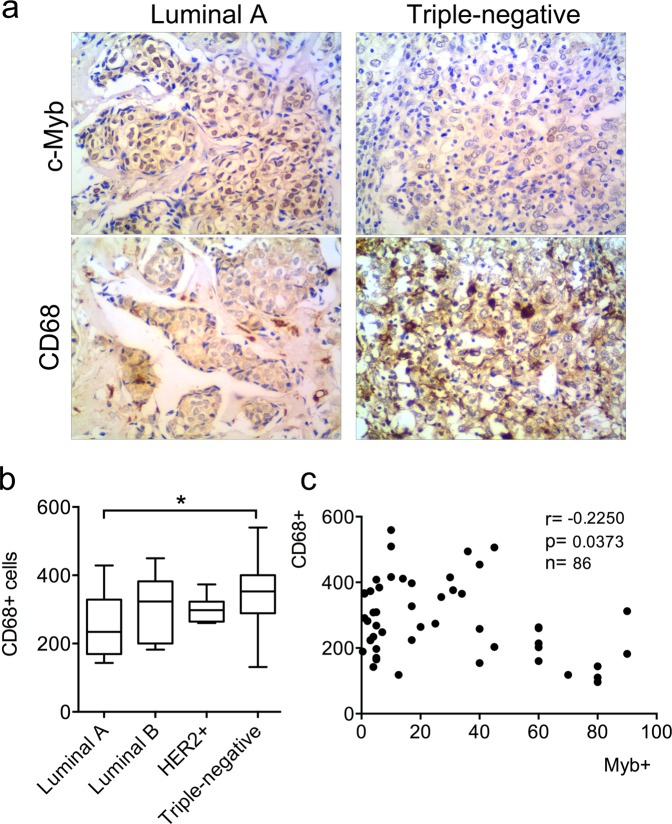

High MYB levels mark tumors with low infiltration by CD68+ macrophages

First, we explored the number of CD68+ cells within subgroups with different immunohistochemical (IHC) status of estrogen receptor (ER), progesteron receptor (PgR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), i.e. luminal A (ER+PgR+HER2−), luminal B (ER+PgR+HER2+), HER2+ (ER−PgR−HER2+) and triple negative (ER−PgR−HER2−). In line with published data we observed a higher number of CD68+ macrophages in triple negative subgroup (Fig. 1a,b). On the contrary, the stronger intensity of MYB expression and higher frequency of c-Myb-positive cells were found in ER-positive tumor samples. When patients of all subtypes (n = 86) were combined, the statistically significant inverse correlation (r = −0.23, p = 0.0373) between the amount of CD68+ cells and frequency of c-Myb+ tumor cells was revealed (Fig. 1c). The significant inverse correlation (r = −0.27, p = 0.0258) was maintained in ER-positive patients, that constitute majority (n = 66) of patients in study group, while within 20 patients of ER-negative subgroup there was no significant correlation (r = 0.199, p = 0.401) (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

Detection of CD68+ TAMs, and c-Myb in BC patient samples according to the ER/PgR/HER2 status. (a) c-Myb and CD68 proteins in BC tissues were detected by IHC. Invasive ductal BCs, left - luminal A subtype (>50% of c-Myb+ tumor cells, low number of CD68+ cells), right - triple negative case (<5% of c-Myb+ tumor cells, high number of CD68+ cells). (b) Absolute amount of CD68+ cells in 40 high power fields X1350 in different subtypes. (c) Correlation between percentage of c-Myb+ tumor cells and number of CD68+ cells as determined by IHC in a cohort 86 BC patients. Pearson correlation coefficient (r), logrank p value (p) and number of patients (n) are indicated.

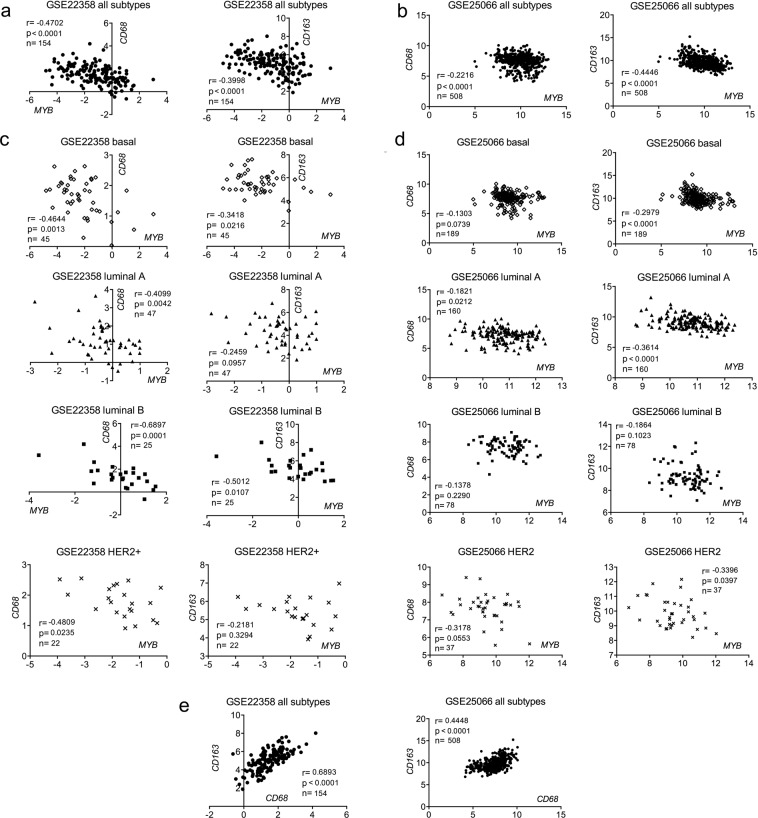

MYB is inversely correlated with CD163/CD68 mRNA in BC molecular subtypes

We used publically available databases to investigate the transcript levels of MYB and two monocyte/macrophage markers CD68 and CD16329. Medisapiens database (medisapiens.org) showed an inverse correlation between MYB and CD163 mRNAs in BC patients (r = −0.192, p < 0.001, n = 1830) (Table S1). CD68 was inversely correlated with MYB in breast lobular carcinomas (r = −0.282, p < 0.001, n = 83), only marginal associations were found in ductal and other carcinomas (Table S1). Then, we calculated correlations between CD68/CD163 and MYB in a cohort of 154 BC patients (GSE22358) across and within molecular subtypes defined using the PAM50 classifier in the original study30. As expected, CD68 and CD163 mRNAs were in positive correlation (r = 0.69, p < 0.0001). MYB expression negatively correlated with both CD68 (r = −0.47, p < 0.0001) and CD163 (r = −0.4, p < 0.0001) across BC subtypes (Fig. 2a). Importantly, the inverse correlations were found also within basal, luminal A, luminal B and HER2+ subtypes, though in luminal A and HER2+ groups correlations with CD68, not CD163, were significant (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Table S2). The higher MYB mRNA expression the lower levels of CD163/CD68 mRNA associations were found also in subgroups with different neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) (Fig. S2). Of note, these results were recapitulated with another dataset (GSE25066)31 as shown in Fig. 2b,d, and Supplementary Table S3. Importantly, the negative correlations between MYB and CD68/CD163 prevailed across and within subtypes also in patients that did not receive any NAC (Fig. S3). Together these data show that tumors overexpressing MYB contain less CD68/CD163 transcript levels independently on the BC subtype.

Figure 2.

Expression of MYB inversely correlates with CD68 and CD163 mRNAs in human BCs. Two datasets were used for correlation analysis: GSE22358 (left; a,c,e) and GSE25066 (right; b,d,e). Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between mRNA expression of indicated genes (MYB vs CD68, MYB vs CD163, and CD68 vs CD163), logrank p value and number of patients (n) are indicated in the graphs. Patients of all subtypes were included in a,b,e; and stratified according to the molecular subtypes (by the PAM50 classifier) in c,d.

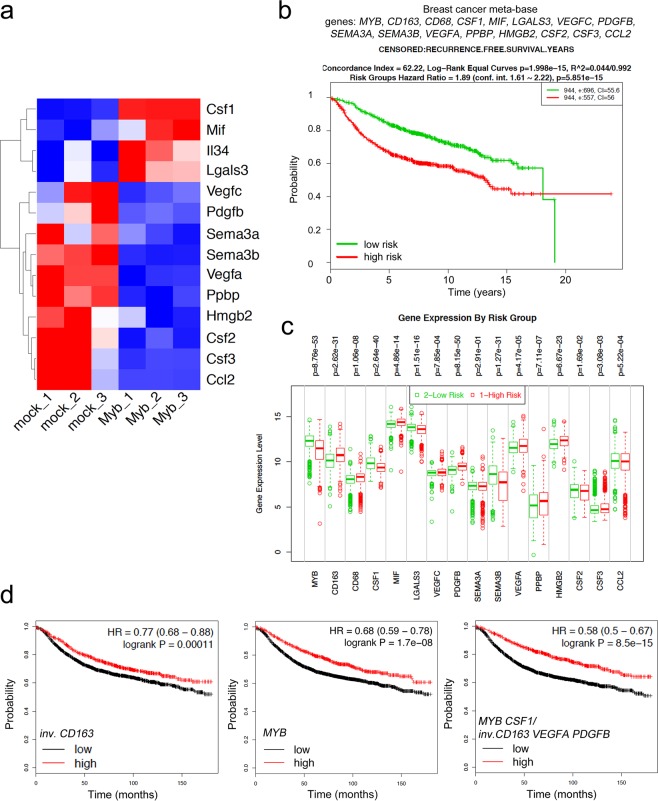

TAM recruitment factors are downregulated upon c-Myb overexpression

There are several cytokines and growth factors known to recruit monocytes/macrophages into tumors1,32–35. One of them, chemokine Ccl2 is suppressed by c-Myb in BC cells, as we described previously23. However, TAMs utilize multiple chemokine signals to accumulate in the tumor microenvironment, as a single chemokine inhibition does not achieve TAMs depletion36. Thus, we took advantage of the established mouse model and screened the c-Myb-responsive transcripts related to TAMs generation/recruitment in 4T1 mammary cancer cells. Comparing transcriptomes of cells overexpressing c-Myb and mock-transfected controls we retrieved the differentially expressed transcripts involved in monocyte/macrophage migration and chemotaxis by gene ontology (GO) terms attribute. A set of 14 potential TAM chemoattractants was identified (Fig. 3a). Besides Ccl2, MYBhigh cells produce less Csf2, Csf3, Sema3a, Sema3b, Vegfa, Vegfc, Pdgfb, Ppbp, Hmgb2, but on contrary more CSF-1R ligands Csf1 and IL34, as well as Lgals3 and inhibitory factor Mif mRNAs when compared to mock-transfected cells (Fig. 3a). Based on these results from a mouse model, we searched human BCs databases. We calculated correlation coefficients for MYB and monocyte/macrophage recruitment factors in three independent datasets (Gene Expression Omnibus, GEO, accession numbers GSE22358, GSE12276, GSE25066) and in Medisapiens meta-base. Significant inverse correlations between VEGFA, SEMA3A, CSF1, CSF2, PDGFB and MYB were frequently found, while SEMA3B and MIF were positively correlated with MYB (Supplementary Tables S1–S4). This indicates that c-Myb may suppress TAMs recruitment via regulation of a specific transcription program in BC tumors.

Figure 3.

Expression of MYB and TAM-related genes is associated with risk of relapse in BCs. (a) Heat map of 14 monocyte and macrophage recruitment/migration factors differentially expressed in 4T1 MYBhigh (Myb1-3) and mock cells as determined by RNA sequencing. (b) Kaplan-Meier analysis for MYB-TAM genes (MYB, CD163, CD68, CSF1, MIF, LGALS3, VEGFC, PDGFB, SEMA3A, SEMA3B, VEGFA, PPBP, HMGB2, CSF2, CSF3, CCL2) expression under the condition of recurrence free survival in BC patients using SurvExpress database, patients included in Breast Cancer Meta-base split to high (red) and low (green) risk cohorts. (c) Expression levels of individual MYB-TAM genes in high vs. low risk groups in Breast Cancer Meta-base. The most significant differentially expressed genes (DEG) are MYB, PDGFB, CSF1, SEMA3B, and CD163. (d) Meta-analyses of BCs patients available on KMplot.com representing the probability of relapse free survival in BCs stratified according to the expression status of CD163 inverted alone (left), MYB alone (middle), and MYB in combination with CSF1 and inverted CD163, VEGFA, PDFGB (right).

Expression of MYB/TAM-related genes predicts outcome for BC patients

To investigate the potential prognostic significance of our findings, we researched publicly available platforms of survival analysis, including SurvExpress37 and Kaplan-Meier Plotter (KM-Plotter)38. To preselect relevant genes within MYB/TAM signature we estimated the prognostic significance of CD163 and CD68 in combination with MYB and c-Myb-related TAM-recruitment factors (CCL2, CSF2, CSF3, CSF1, VEGFA, VEGFC, SEMA3A, SEMA3B, PDGFB, PPBP, HMGB2, LGALS3, MIF, IL34) in predicting the recurrence-free survival (RFS) rates using SurvExpress database. SurvExpress implements Cox regression model to estimate β-coefficients of each gene that can be interpreted as a risk coefficients. The prognostic index (PI = β1 × 1 + β2 × 2 + … + βpxp, where xi is the expression value and the βI is obtained from the Cox fitting), also known as the risk score, is then used to generate risk groups. Overall, the MYB/TAM multigene predictor can significantly separate low- and high-risk groups in the Breast Cancer Meta-base (n = 1888) (Fig. 3b) and in all remaining datasets (n = 19) that monitor recurrence/relapse/metastasis events (Supplementary Table S5). CD163, VEGFA, PDGFB, CSF1 together with MYB were repeatedly found among the most significant differentially expressed genes (DEG) within risk groups (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Table S5). While high-risk groups had higher CD163, VEGFA, and PDGFB expression, they exhibited lower MYB and CSF1 expression levels. In addition, these genes were often among those with significant β-coefficients within the Cox fitting (Supplementary Table S5, significant genes Cox).

Hence, we selected MYB, CSF1, CD163, VEGFA and PDGFB to compare the probability of RFS in BCs using KM-plotter38. BC patients (n = 3951) were stratified according to the expression status of MYB, CSF1 and inverted expression status of CD163, VEGFA and PDGFB. As previously reported by us and others20,23 high MYB expression decreases the risk of relapse (hazard ratio, HR = 0.68, p = 1.7e − 08) (Fig. 3d). On the other hand, patients with low CD163 expression had better survival outcome (HR = 0.77, p = 0.00011) that is in line with published data39. Interestingly, tumors in the top quartile of MYB and CSF1 expression and the lowest quartile of CD163, VEGFA and PDGFB expression showed better RFS (HR = 0.58, p = 8.5e−15) compared to MYB or CD163 alone (Fig. 3d).

Discussion

We found previously that c-Myb expression is associated with good prognosis in BC and colorectal cancer patients23,40,41. It suppressed a specific subset of inflammatory factors that is elevated in highly metastatic mouse tumors. Blunted inflammatory arsenal in MYBhigh tumors resulted in severely impaired monocyte-assisted extravasation and lung metastasis23,42. Tumor cell-derived inflammatory mediators also shape microenvironment at the tumor site and actively guide infiltration of immune cells from blood43. Tumor infiltrating macrophages are often correlated with a bad prognosis, and their abundance relates to the process of metastasis44,45. TAMs are key orchestrators of cancer-related inflammation and exert several pro-tumorigenic functions, as they produce a large array of growth factors supporting angiogenesis, and participate in the suppression of the adaptive anti-tumor immune response46. Here we explored whether the number of TAMs differs between MYBhigh and MYBlow breast carcinomas. We found that tumors with higher frequency of c-Myb+ tumor cells have indeed lower density of TAMs. These findings suggest that c-Myb-driven transcription changes in tumor cells results in reduced infiltration of the primary tumor by immune cells, which may impair their capacity to form distant metastasis.

In line with previous findings where the presence of TAMs inversely correlated with ER expression in BC10,47, we observed more CD68+ cells in triple-negative breast tumors compared to luminal subtypes. Medrek et al. also described the tumor stroma of luminal subtypes to be rarely infiltrated by TAMs that is in contrary to the densely infiltrated tumors of the basal-like subtype29. The subtype-dependent TAMs abundance was confirmed with microarray expression data showing that the basal-like breast cancer had significantly higher levels of CD163 and CD68 mRNAs compared to luminal breast cancer29. Of note, high MYB levels are generally found in luminal subtypes23,48. In this study, we evaluated mRNA levels of the two macrophage markers, CD68 as a pan-macrophage marker and CD163 specific for M2-like macrophages49,50, in large cohorts of BC patients to confirm our immunohistochemical findings. Human microarray data mining showed that expression of both CD68 and CD163 often inversely correlates with MYB, even within molecular subtypes, implying that c-Myb reduces TAMs in BCs independently on the ER-status.

An array of tumor-derived chemoattractants such as CSF1, CSF2, CCL2, VEGFA, and SEMA3A contribute to the recruitment of monocytic precursors, resulting in TAMs accumulation1,32–34,51–53. A prominent monocyte recruiting factor Ccl2 is one of the inflammatory mediators directly repressed by c-Myb23,54. The correlation between macrophage accumulation and Ccl2 expression has been demonstrated in breast carcinomas and Ccl2 neutralization was found to attenuate recruitment of inflammatory monocytes and reduce metastasis formation in tumor-bearing mice26. A set of multiple cytokines shape abundance and phenotype of macrophages in a tumor, rather than a single ligand-receptor pair36. We hypothesized that decreased accumulation of TAMs in MYBhigh tumors is caused by downregulation of several factors, including SEMA3A, VEGFA, CSF2 or PDGFB that we found to be inversely correlated with c-Myb not only in mammary cell lines but also in primary human BCs. However, reduced amount of TAMs associated with high MYB expression by tumor cells may also arise from altered TAMs proliferation not only recruitment of precursors from circulation. Recent evidence indicates that fully differentiated macrophages may proliferate in situ, thus increasing the pool of TAMs55. Interestingly, the cell-surface guidance molecule SEMA3A contributes to differential proliferative control of TAMs56. Dissecting the mechanism of c-Myb effect on TAMs density in BCs that likely involves a specific transcription module regulation, requires further functional studies. How are tumors with high MYB expression populated by TAMs, whether their recruitment, or proliferation is altered by tumor-derived cytokine network under control of c-Myb, whether such milieu could be mimicked by gene depletion/overexpression or pharmacologically, and how TAMs differ in their properties (not only quantity) in Myb-high vs. Myb-low tumors etc. should be investigated in preclinical models.

The presence of proliferating TAMs in human BC is associated with poor clinical outcomes and early recurrence10. Moreover, the expression of the macrophage antigen CD163 in BCs has a prognostic impact on the occurrence of distant metastases and reduced patient survival time29,39 that we also confirmed using publically available expression databases. Combination of MYB, its potential target genes and CD163 enhanced the relapse risk assessment compared to CD163 alone, and vice versa, a biomarker consisting of MYB and TAM-related transcripts CD163, CSF1, VEGFA and PDGFB increased the prognostic performance of MYB. These results indicate a clinical relevance of the identified MYB-TAMs liaison.

Unexpectedly, we found that CSF1 expression, unlike CD163, VEGFA and PDGFB, is significantly higher in low-risk group. CSF-1 was one of the TAM-related cytokines up-regulated in MYBhigh 4T1 cells, along with interleukin 34 (IL34), but correlation analyses in clinical samples mostly revealed negative association. CSF-1 is a myelopoietic growth factor regulating the recruitment, proliferation, differentiation, and survival of macrophages via binding to CSF-1 receptor (CSF-1R/c-Fms/CD115). Interestingly, IL34 is a newly discovered alternative ligand for CSF-1R, triggering the same signaling events and promoting the differentiation and survival of macrophages, only with different polarization potential57. The role of CSF1/CSF-1R as predictive factors in BC remains unclear. Although frequently referred as a poor prognosis factors, clinical evidence shows variable associations that rather depend on patient groups or protein localization58–64. Underscoring the complexity of CSF-1/CSF-1R pair in BC prognosis, Beck et al. found that a CSF-1 response signature predicted different outcomes for patients with breast cancer depending on the tumor subtype65.

The function of CSF1/CSF-1R remains controversial also in experimental models of breast cancer. In macrophage-deficient MMTV-PyMT (mouse mammary tumor virus- polyoma middle T-antigen) mice carrying a null mutation in the Csf1 gene, TAMs were unable to accumulate in primary tumors and resulted in reduced lung metastasis66. Macrophage-depletion mimics Csf1 deficiency in reduced lung metastatic seeding67. In MCF-7 mammary carcinoma cell xenografts CSF-1 block has been shown to reduce host macrophage infiltration and suppress tumor growth68. This, along with other observations of the beneficial effects of targeting CSF-1R in various cancers69–71, has led to the initiation of several clinical trials with either a monoclonal antibody or a small molecule inhibitor of CSF-1R72. However, recent studies placed a cautionary note on blocking CSF-1 signaling as a therapeutic modality in cancer. Neutralizing anti–CSF-1R and anti–CSF-1 antibodies, or small-molecule inhibitors of CSF-1R, not only left the tumor growth unaffected but actually increased spontaneous metastasis63. The block of CSF-1R or CSF-1 led to increased levels of serum G-CSF (granulocyte colony stimulating factor, CSF-3), increased frequency of neutrophils, while TAMs were variably reduced. Block of G-CSF receptor overcomes the increase in metastasis and neutrophil numbers, indicating that this enhanced metastasis is driven by G-CSF that in turn alters the phenotype of TAMs35,63. Of note, CSF1 is one of the genes included in lung-metastatic signature that is down-regulated in aggressive metastatic MDA-MB-231 cells73. Whether differential control CSF-1/CSF-3 by c-Myb may guide specific leukocyte infiltrate that accounts for lung metastasis suppression requires further investigations.

Because high TAM infiltration is associated with poor prognosis and therapeutic failure in cancer patients, inhibition of recruitment and retention of macrophages may represent a valuable strategy to combine with conventional therapies. It is plausible that TAMs utilize multiple signals to accumulate in the tumor microenvironment, which makes any approach to eliminate them difficult. Identification of a transcription program running in tumor cells with high MYB expression that prevents macrophage accumulation may open new venues towards better prognosis estimation and potentially towards TAMs targeting.

Methods

Immunohistochemistry

The study group included 86 breast cancer patients (median age 53 years) with invasive breast cancer who had undergone surgical treatment at Lviv Regional Oncological Center in the period 2013–2016 (Table S6). All tumor samples were obtained as surgical specimen before any kind of treatment. This study complied with the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and guidelines for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK)74 and was approved by the Ethical Committee of Lviv Regional Oncological center. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

IHC detection of c-Myb, CD68, ER, PgR, HER2 was performed on formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissues of primary tumors as described previously23. Briefly, 4 μm thick tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated and incubated in 3% Hydrogen Peroxide for 5 minutes. The antigen retrieval was performed by heating the sections in citrate buffer (pH 6.0). The slides were blocked for 5 minutes with Ultra V Block solution from UltraVision LP Large Volume Detection System HRP (Horseradish Peroxidase) Polymer Ready-To-Use kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, UK), and incubated with the primary antibodies: rabbit monoclonal anti-c-Myb (clone EP769Y, dilution 1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) at room temperature (RT) overnight; rabbit monoclonal anti-CD68 (clone KP1, dilution 1:200, Thermo Fisher Scientific, UK), rabbit monoclonal anti-ER (clone SP1, dilution 1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific, UK), rabbit monoclonal anti-PgR (clone SP2, dilution 1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific, UK) at RT 30 min, and rabbit monoclonal anti-HER2 (clone SP3, dilution 1:350; Thermo Fisher Scientific, UK) at RT 20 min.

The slides were washed 4 times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated in Primary Antibody Enhancer (from UltraVision kit) at RT for 10 min. Then, the slides were incubated with HRP Polymer (from UltraVision kit) at RT for 15 minutes, washed 4 times in PBS and incubated with 3,3΄-diaminobenzidine (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) as chromogen for 5 min. The slides were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin solution (Sigma Aldrich). Negative controls were prepared by incubating samples in the absence of a primary antibody. Evaluation of all IHC results was performed using a uniform Zeiss microscope independently by two pathologists.

The tumors were evaluated for percentage of immunostained positive cells in 10 random fields at magnification x200. The amount of tumor infiltrating macrophages was evaluated as positive cells at x1350 magnification (in 20 stromal and 20 tumor fields), which gave the total amount of macrophages in 40 high power fields. This amount has been used for all further calculations.

Expression of TAM recruitment factors in MYBhigh mammary cancer cell line

Derivation and RNA sequencing (RNAseq) of 4T1 cells overexpressing Myb (MYBhigh) were described previously23. The expression levels of potential TAM recruitment factors were analyzed as follows: differentially expressed genes in MYBhigh and mock-transfected cells were searched for GO terms associated with monocyte and macrophage migration/activation/chemotaxis (GO:0042116, GO:0048246, GO:0002548, GO:0042056, GO:1905517, GO:0002688). Out of 22 genes associated with these GO terms, 14 were selected encoding potential paracrine factors directed towards macrophages. These differentially expressed transcripts were clustered and shown in heatmap using FGCZ (Functional Genomics Center Zürich) Heatmap tool (http://fgcz-shiny.uzh.ch). The RNAseq data are available in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, NCBI) under the accession number GSE104264.

Correlation analysis

We used Medisapiens (ist.medisapiens.com) and NCBI GEO databases to assess the differential expression of MYB, CD68, CD163, CSF1, CSF2, CSF3, PDGFB, SEMA3A, SEMA3B, VEGFA, VEGFC, PPBP, MIF, HMBG2, IL34, LGALS3 mRNA in human BCs. Correlations between MYB and CCL2 were shown previously23. Pearson correlations were calculated with the GraphPad Prism software (version 6.07). Besides Medisapiens, three independent GEO datasets were used (accession numbers: GSE25066, GSE22358, GSE12276), results in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Tables S1–S4.

Survival analysis

To assess the prognostic significance of a list of MYB-TAMs related genes we used SurvExpress database37. All datasets offering recurrence, relapse or metastasis endpoints were used for Cox fitting, the maximum row average for duplicated genes, two risk groups split at the median prognostic index. The log-rank test was used to evaluate statistically the equality of survival curves. All results are summarized in Supplementary Table S5.

Kaplan–Meier plots representing the probability of RFS in BCs stratified according to the expression status of MYB, CSF1, CD163, PDGFB and VEGFA were calculated with KM-plotter (kmplot.com)38. Follow-up threshold set for 15 years, patients were split by upper quartile expression, only JetSet best probe set per gene included, the expression of CD163, PDGFB, and VEGFA was inverted. The log-rank test was used to assess the significance of the correlation between gene(s) expression and shorter survival outcome.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with the GraphPad Prism software (version 6.07). For correlation analysis Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated. Survival curves were evaluated using the log-rank test.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by SCOPES/SNF grant IZ73Z0-152361, by Czech Science Foundation grant 17-08985Y, by Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic grant NV18-07-00073 and supported by the European Regional Development Fund - Project ENOCH (No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000868).

Author Contributions

Conception and design: L.K., N.V., L.B. Clinical specimen collection, I.H.C., histopathological evaluation: N.V., T.G., O.P., R.H. Survival and bioinformatic analysis: L.K., M.D., P.B. Writing, review, and revision of the manuscript: L.K., P.B., J.S., L.B.

Data Availability

The RNAseq data are available in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, NCBI) under the accession number GSE104264. Other datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-48051-1.

References

- 1.Yang L, Zhang Y. Tumor-associated macrophages: from basic research to clinical application. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10:58. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0430-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim J, Bae JS. Tumor-Associated Macrophages and Neutrophils in Tumor Microenvironment. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:6058147. doi: 10.1155/2016/6058147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, Allavena P, Sica A. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:549–55. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(02)02302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valković T, et al. Correlation between vascular endothelial growth factor, angiogenesis, and tumor-associated macrophages in invasive ductal breast. Virchows Arch. 2002;440:583–8. doi: 10.1007/s004280100458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li W, et al. The association between expressions of Ras and CD68 in the angiogenesis of breast cancers. Cancer Cell Int. 2015;15:17. doi: 10.1186/s12935-015-0169-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolat F, et al. Microvessel density, VEGF expression, and tumor-associated macrophages in breast tumors: correlations with prognostic parameters. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2006;25:365–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruffell B, Coussens LM. Macrophages and Therapeutic Resistance in Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:462–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Palma M, Lewis CE. Cancer: Macrophages limit chemotherapy. Nature. 2011;472:303–4. doi: 10.1038/472303a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan ZY, Luo RZ, Peng RJ, Wang SS, Xue C. High infiltration of tumor-associated macrophages in triple-negative breast cancer is associated with a higher risk of distant metastasis. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:1475–80. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S61838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell MJ, et al. Proliferating macrophages associated with high grade, hormone receptor negative breast cancer and poor clinical outcome. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128:703–711. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1154-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeisberger SM, et al. Clodronate-liposome-mediated depletion of tumour-associated macrophages: a new and highly effective antiangiogenic therapy approach. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:272–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogers TL, Holen I. Tumour macrophages as potential targets of bisphosphonates. J Transl Med. 2011;9:177. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giraudo E, Inoue M, Hanahan D. An amino-bisphosphonate targets MMP-9-expressing macrophages and angiogenesis to impair cervical carcinogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:623–33. doi: 10.1172/JCI200422087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsagozis P, Eriksson F, Pisa P. Zoledronic acid modulates antitumoral responses of prostate cancer-tumor associated macrophages. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57:1451–9. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0482-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borsig L, Wolf MJ, Roblek M, Lorentzen A, Heikenwalder M. Inflammatory chemokines and metastasis-tracing the accessory. Oncogene. 2014;33:3217–24. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramsay RG, Gonda TJ. MYB function in normal and cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:523–34. doi: 10.1038/nrc2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drabsch Y, Robert RG, Gonda TJ. MYB suppresses differentiation and apoptosis of human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R55. doi: 10.1186/bcr2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miao RY, et al. MYB is essential for mammary tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7029–37. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thorner AR, Parker JS, Hoadley KA, Perou CM. Potential tumor suppressor role for the c-Myb oncogene in luminal breast cancer. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicolau M, Levine AJ, Carlsson G. Topology based data analysis identifies a subgroup of breast cancers with a unique mutational profile and excellent survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:7265–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102826108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hugo HJ, et al. Direct repression of MYB by ZEB1 suppresses proliferation and epithelial gene expression during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:R113. doi: 10.1186/bcr3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu LY, et al. A supervised network analysis on gene expression profiles of breast tumors predicts a 41-gene prognostic signature of the transcription factor MYB across molecular subtypes. Comput Math Methods Med. 2014;2014:813067. doi: 10.1155/2014/813067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knopfová L, et al. Transcription factor c-Myb inhibits breast cancer lung metastasis by suppression of tumor cell seeding. Oncogene. 2018;37:1020–1030. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang WB, et al. Targeted gene silencing of CCL2 inhibits triple negative breast cancer progression by blocking cancer stem cell renewal and M2 macrophage recruitment. Oncotarget. 2016;7:49349–49367. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitamura T, et al. CCL2-induced chemokine cascade promotes breast cancer metastasis by enhancing retention of metastasis-associated macrophages. J Exp Med. 2015;212:1043–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qian BZ, et al. CCL2 recruits inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis. Nature. 2011;475:222–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ueno T, et al. Significance of macrophage chemoattractant protein-1 in macrophage recruitment, angiogenesis, and survival in human breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:3282–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yao M, Yu E, Staggs V, Fan F, Cheng N. Elevated expression of chemokine C-C ligand 2 in stroma is associated with recurrent basal-like breast cancers. Mod Pathol. 2016;29:810–23. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Medrek C, Pontén F, Jirström K, Leandersson K. The presence of tumor associated macrophages in tumor stroma as a prognostic marker for breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:306. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glück S, et al. TP53 genomics predict higher clinical and pathologic tumor response in operable early-stage breast cancer treated with docetaxel-capecitabine ± trastuzumab. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132:781–91. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1412-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Itoh M, et al. Estrogen receptor (ER) mRNA expression and molecular subtype distribution in ER-negative/progesterone receptor-positive breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;143:403–9. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2763-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chanmee T, Ontong P, Konno K, Itano N. Tumor-associated macrophages as major players in the tumor microenvironment. Cancers (Basel) 2014;6:1670–90. doi: 10.3390/cancers6031670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Casazza A, et al. Impeding macrophage entry into hypoxic tumor areas by Sema3A/Nrp1 signaling blockade inhibits angiogenesis and restores antitumor immunity. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:695–709. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh S, et al. Initiative action of tumor-associated macrophage during tumor metastasis. Biochim Open. 2017;4:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.biopen.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hollmén M, et al. G-CSF regulates macrophage phenotype and associates with poor overall survival in human triple-negative breast cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2015;5:e1115177. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1115177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Argyle D, Kitamura T. Targeting Macrophage-Recruiting Chemokines as a Novel Therapeutic Strategy to Prevent the Progression of Solid Tumors. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2629. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aguirre-Gamboa R, et al. SurvExpress: an online biomarker validation tool and database for cancer gene expression data using survival analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Györffy B, et al. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:725–31. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shabo I, Stål O, Olsson H, Doré S, Svanvik J. Breast cancer expression of CD163, a macrophage scavenger receptor, is related to early distant recurrence and reduced patient survival. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:780–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tichý M, et al. Overexpression of c-Myb is associated with suppression of distant metastases in colorectal carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:10723–9. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-4956-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tichý M, et al. High c-Myb Expression Associates with Good Prognosis in Colorectal Carcinoma. J Cancer. 2019;10:1393–7. doi: 10.7150/jca.29530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knopfová L, et al. c-Myb regulates matrix metalloproteinases 1/9, and cathepsin D: implications for matrix-dependent breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2012;11:15. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-11-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Landskron G, De la Fuente M, Thuwajit P, Thuwajit C, Hermoso MA. Chronic inflammation and cytokines in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunol Res. 2014;2014(():149185. doi: 10.1155/2014/149185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Condeelis J, Pollard JW. Macrophages: obligate partners for tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. Cell. 2006;124:263–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao X, et al. Prognostic significance of tumor-associated macrophages in breast cancer: a meta-analysis of the literature. Oncotarget. 2017;8:30576–30586. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Noy R, Pollard JW. Tumor-associated macrophages: from mechanisms to therapy. Immunity. 2014;41:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steele RJ, Eremin O, Brown M, Hawkins RA. Oestrogen receptor concentration and macrophage infiltration in human breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1986;12:273–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gonda TJ, Leo P, Ramsay RG. Estrogen and MYB in breast cancer: potential for new therapies. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8:713–7. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.6.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sousa S, et al. Human breast cancer cells educate macrophages toward the M2 activation status. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:101. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0621-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tiainen S, et al. High numbers of macrophages, especially M2-like (CD163-positive), correlate with hyaluronan accumulation and poor outcome in breast cancer. Histopathology. 2015;66:873–83. doi: 10.1111/his.12607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aras S, Zaidi MR. TAMeless traitors: macrophages in cancer progression and metastasis. Br J Cancer. 2017;117:1583–1591. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Linde N, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-induced skin carcinogenesis depends on recruitment and alternative activation of macrophages. J Pathol. 2012;227:17–28. doi: 10.1002/path.3989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barleon B, et al. Migration of human monocytes in response to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is mediated via the VEGF receptor flt-1. Blood. 1996;87:3336–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bonapace L, et al. Cessation of CCL2 inhibition accelerates breast cancer metastasis by promoting angiogenesis. Nature. 2014;515:130–3. doi: 10.1038/nature13862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tymoszuk P, et al. In situ proliferation contributes to accumulation of tumor-associated macrophages in spontaneous mammary tumors. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44:2247–62. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wallerius M, et al. Guidance Molecule SEMA3A Restricts Tumor Growth by Differentially Regulating the Proliferation of Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Cancer Res. 2016;76:3166–78. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boulakirba S, et al. IL-34 and CSF-1 display an equivalent macrophage differentiation ability but a different polarization potential. Sci Rep. 2018;8:256. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18433-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scholl SM, et al. Anti-colony-stimulating factor-1 antibody staining in primary breast adenocarcinomas correlates with marked inflammatory cell infiltrates and prognosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:120–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aharinejad S, et al. Elevated CSF1 serum concentration predicts poor overall survival in women with early breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20:777–83. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Richardsen E, Uglehus RD, Johnsen SH, Busund LT. Macrophage-colony stimulating factor (CSF1) predicts breast cancer progression and mortality. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:865–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kluger HM, et al. Macrophage colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor expression is associated with poor outcome in breast cancer by large cohort tissue microarray analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:173–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-0699-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zins K, Heller G, Mayerhofer M, Schreiber M, Abraham D. Differential prognostic impact of interleukin-34 mRNA expression and infiltrating immune cell composition in intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. Oncotarget. 2018;9:23126–23148. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Swierczak A, et al. The promotion of breast cancer metastasis caused by inhibition of CSF-1R/CSF-1 signaling is blocked by targeting the G-CSF receptor. Cancer. Immunol Res. 2014;2:765–76. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Laoui D, Van Overmeire E, De Baetselier P, Van Ginderachter JA, Raes G. Functional Relationship between Tumor-Associated Macrophages and Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor as Contributors to Cancer Progression. Front Immunol. 2014;5:489. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beck AH, et al. The macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 response signature in breast carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:778–87. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin EY, Nguyen AV, Russell RG, Pollard JW. Colony-stimulating factor 1 promotes progression of mammary tumors to malignancy. J Exp Med. 2001;193:727–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Qian B, et al. A distinct macrophage population mediates metastatic breast cancer cell extravasation, establishment and growth. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aharinejad S, et al. Colony-stimulating factor-1 blockade by antisense oligonucleotides and small interfering RNAs suppresses growth of human mammary tumor xenografts in mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5378–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ries CH, et al. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages with anti-CSF-1R antibody reveals a strategy for cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:846–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Strachan DC, et al. CSF1R inhibition delays cervical and mammary tumor growth in murine models by attenuating the turnover of tumor-associated macrophages and enhancing infiltration by CD8+ T cells. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2:e26968. doi: 10.4161/onci.26968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Linde N, et al. Macrophages orchestrate breast cancer early dissemination and metastasis. Nat Commun. 2018;9:21. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02481-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Qiu SQ, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages in breast cancer: Innocent bystander or important player? Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;70:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Minn AJ, et al. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to lung. Nature. 2005;436:518–24. doi: 10.1038/nature03799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McShane LM, et al. REporting recommendations for tumor MARKer prognostic studies (REMARK) Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100:229–35. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The RNAseq data are available in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, NCBI) under the accession number GSE104264. Other datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.