Abstract

Histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) has emerged as a promising drug target for various human diseases, including diverse neurodegenerative diseases and cancer. Herein, we reported a series of 2,4-imidazolinedione derivatives as novel HDAC6 isoform-selective inhibitors based on structure-based drug design. Most target compounds exhibit good profiles in a preliminary screening concerning HDAC6 inhibitory activities. Moreover, the most active compound 10c increases the acetylation level of α-tubulin with little effect on the acetylation of histone H3. Further biological evaluation suggested that potent compound 10c, which possesses good antiproliferative activity, could induce apoptosis in HL-60 cell by activating caspase 3.

Keywords: HDAC6; isoform-selective; 2,4-imidazolinedione; antiproliferative; apoptosis

Many human diseases related to epigenetic etiology have stimulated the development of “epigenetic” therapies.1 As epigenetic eraser, histone deacetylases (HDACs), together with histone acetyltransferases (HATs), maintain the homeostasis of the acetylation on histones and other proteins.2 However, the aberrant acetylated state of histone mediated by HDACs overexpression is associated with many diseases including cancer.3 Inhibition of HDACs could induce apoptosis as well as antiproliferation of diverse cancer cells in vivo or in vitro, and HDACs have emerged as promising targets for cancer treatment.4,5 Efforts of two decades have developed five approved HDAC inhibitors (vorinostat, romidepsin, panobinostat, belinostat, and chidamide) for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCL), multiple myeloma (MM), and peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCL).6−10 Despite the success of HDAC inhibitors in cancer therapy, the indiscriminate inhibition on HDACs causes various side effects, such as diarrhea, fatigue, neutropenia, and so on.11−14 HDAC isoform-selective inhibitors, which target specific HDAC isoform, provide a blueprint for the development of HDAC inhibitors with no or less side effects.15 As a member of HDAC family, HDAC6 plays a pivotal role in myriad eukaryotic biological processes.16,17 The overexpression of HDAC6 has been confirmed in many tumor cell lines,18,19 and HDAC6 is required for efficient oncogenic cell transformation.20 Although some HDAC6 selective inhibitors exhibited good antiproliferative activities,21,22 other HDAC6 inhibitors displayed minor antiproliferative activities.23,24 Indiscriminate inhibition on HDACs or off-target effect may be caused by the controversy in the antiproliferative activity of HDAC6 selective inhibitors. Therefore, the antiproliferative activities remained to be explored. Here, we sought to develop HDAC6 isoform-selective inhibitors and explore their antiproliferative activities.

HDAC inhibitors have the well accepted pharmacophore: zinc binding group (ZBG), linker, and cap group (SI Figure 1). Modifying cap, altering the linker or varying ZBG have become important strategies to develop HDAC isoform-selective inhibitors.25 Recently, our group developed purine derivatives as HDAC inhibitors, which exhibit nanomolar inhibitory activities against HDAC6, whereas the selectivity remained to be improved.26

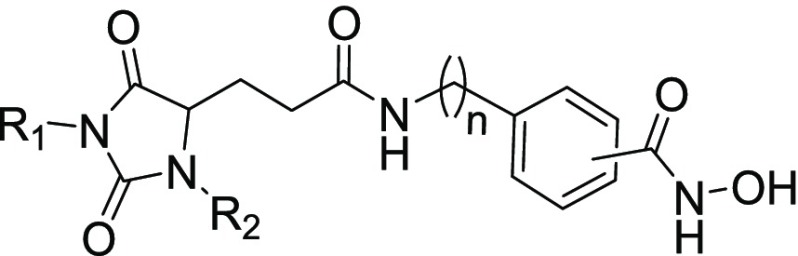

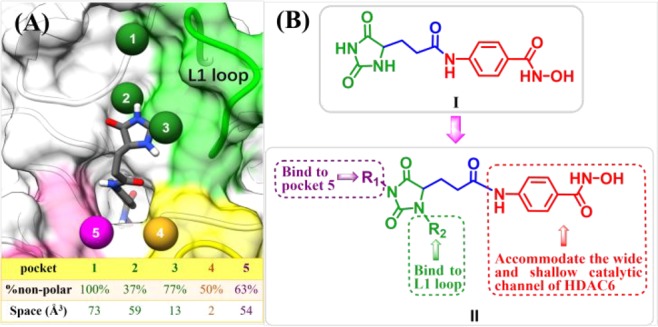

It has been widely recognized that cap group plays an important role in isoform selectivity of HDAC inhibitors.25 We analyzed the binding pockets in HDAC6 using AlphaSpace(27) and found several hydrophobic pockets in the rim of lysine binding channel, including L1 loop pockets 1, 2, and 3 (Figure 1A). A recent study suggested that L1 loop pocket of HDAC6 provides a conserved binding site to achieve HDAC6 isoform selectivity.28 Moreover, some 3-aryl-2,4-imidazolinedione derivatives were mentioned as HDAC inhibitors in 2015,29 whereas these structures with only one aromatic substitution in R1 position did not exhibit HDAC6 selective inhibition. Molecular docking of 2,4-imidazolinedione-based lead compound I (Figure 1A,B), which possesses no substituent at R1 and R2 positions, suggested that proper modification of 2,4-imidazolinedione scaffold would be helpful to accommodate unoccupied pocket spaces and improve binding affinity to HDAC6. Considering the hydrophobicity and size of these unoccupied pockets (Figure 1A), different aromatic rings were introduced into 2,4-imidazolinedione at R1 and R2 positions, which serves as cap group in our newly designed HDAC6 inhibitors (Figure 1B). However, bulky and aromatic linkers accommodate the wide and shallow catalytic channel of HDAC6 well,30,31 which indicated that N-hydroxybenzamide could be used as linker and ZBG (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Pocket analysis of HDAC6 was performed using AlphaSpace.27 (B) Design of 2,4-imidazolinedione derivatives as HDAC6 selective inhibitors.

In our ongoing study, we report the synthesis and biological evaluation of the disubstituted (R1 and R2) 2,4-imidazolinedione N-hydroxybenzamides derivatives as HDAC6 selective inhibitors.

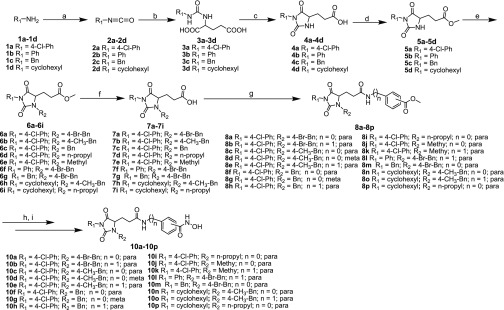

The synthetic methods for compounds 10a–10p are shown in Scheme 1. The amines listed were transformed into isocyanates through triphosgene and intermediate urea (3a–3d) and obtained from the isocyanates coupled with the amino acid. The cyclization reactions were simply mediated by concentrations of HCl to obtain intermediates 4a–4d. Then, the key intermediates 6a–6i were prepared by N-alkylation at R2 of 2,4-imidazolinedione. Compounds 7a–7i were obtained by deprotecting with LiOH, and they were used to prepare 8a–8p by amide coupling. After deprotecting, intermediates 9a–9p were converted to target compounds 10a–10p according to literature procedures.32 It should be noted that intermediates 6a–6i, 7a–7i, and 8a–8p and target compounds 10a–10p are racemates.

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) triphosgene, NaHCO3, CH2Cl2; (b) (i) toluene, 2 M NaOH, 0 °C, 4 h, (ii) 6 M HCl, 44–72%; (c) hydrochloric acid, reflux, 3 h, 88–92%; (d) CH3COCl, MeOH, reflux, 5 h, 95–97%; (e) K2CO3, KI, DMF, overnight, 45–93%; (f) LiOH·H2O, THF/H2O, rt, 6 h, 78–97%; (g) HATU, DIPEA, CH2Cl2, rt, overnight, 40–95%; (h) LiOH·H2O, THF/H2O, rt, 6 h; (i) isobutyl chlorocarbonate, 4-methylmorpholine, THF, NH2OH·HCl, KOH, MeOH, rt, 6 h, 17–65%.

We evaluated HDAC6 inhibitory activities of all target compounds with vorinostat (SAHA) as the positive control. As shown by the results summarized in Table 1, most target compounds have good HDAC6 inhibitory activities. Structure–activity relationships suggested that compounds with para-substituted N-hydroxybenzamides exhibit good HDAC6 inhibitory activities, whereas compounds with meta-substituted N-hydroxybenzamides are less active. Molecule docking study of compound 10c (SI Figure 15) indicated that the hydroxamic acid of compound 10c chelated with zinc ion properly and formed a series of hydrogen bond interactions with key residues (His 610, Tyr 782). This may help us to understand the reason why para-substituted N-hydroxybenzamides are more active than meta-substituted N-hydroxybenzamides (Table 1). As for the linker, compounds without spacer (n = 0) possess suitable linkers, and these linkers allow the cap groups to reach and interact with L1 loop, while allowing the ZBG to chelate with zinc ion properly (SI Figure 15). However, compounds 10b, 10e, 10h, 10k, 10l, and 10o, which possess one methylene spacer (n = 1), exhibit lower inhibition against HDAC6 due to the longer linkers. Moreover, docking study of compound 10c suggested that the phenyl in the linker of (S)-10c formed π–π interactions with Phe 680, whereas the phenyl in the linker of (R)-10c formed π–π interactions with Phe 620. Specially, the amide in the linkers of (S)-10c and (R)-10c both formed hydrogen bond interaction with Ser 568, which may explain the reason why compounds with no spacer (n = 0) between amide group and phenyl in the linker are more active than those with one methylene spacer (n = 1).

Table 1. HDAC6 Inhibitory Activities of Target Compounds.

| compd | R1 | R2 | n | position | IC50 (nM)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10a | 4-Cl-Ph | 4-Br-Bn | 0 | para | 9.7 ± 0.6 |

| 10b | 4-Cl-Ph | 4-Br-Bn | 1 | para | 16.5 ± 0.4 |

| 10c | 4-Cl-Ph | 4-CH3-Bn | 0 | para | 4.4 ± 0.4 |

| 10d | 4-Cl-Ph | 4-CH3-Bn | 0 | meta | >40 |

| 10e | 4-Cl-Ph | 4-CH3-Bn | 1 | para | 18.9 ± 0.4 |

| 10f | 4-Cl-Ph | Bn | 0 | para | 7.6 ± 0.8 |

| 10g | 4-Cl-Ph | Bn | 0 | meta | >40 |

| 10h | 4-Cl-Ph | Bn | 1 | para | 12.7 ± 2.7 |

| 10i | 4-Cl-Ph | n-propyl | 0 | para | 12.6 ± 2.3 |

| 10j | 4-Cl-Ph | methyl | 0 | para | 7.0 ± 1.3 |

| 10k | 4-Cl-Ph | methyl | 1 | para | 11.8 ± 3.2 |

| 10l | Ph | 4-Br-Bn | 1 | para | 13.6 ± 2.1 |

| 10m | Bn | 4-Br-Bn | 0 | para | 9.8 ± 1.8 |

| 10n | cyclohexyl | 4-CH3-Bn | 0 | para | 10.3 ± 1.3 |

| 10o | cyclohexyl | 4-CH3-Bn | 1 | para | 17.0 ± 0.78 |

| 10p | cyclohexyl | n-propyl | 0 | para | >40 |

| SAHA | 39.9 ± 9 |

All compounds were assayed at least two times, and the results are expressed with standard deviations.

In our studies, different substituents attached to 2,4-imidazolinedione in R1 and R2 position also show impacts on HDAC6 inhibitory activities. Except compound 10j, compounds with phenyl and substituted benzyl on cap region show better HDAC6 inhibitory activities compared to other compounds. Compound 10p, which possesses no aromatic rings at R1 and R2 positions, exhibits poor HDAC6 inhibitory activity.

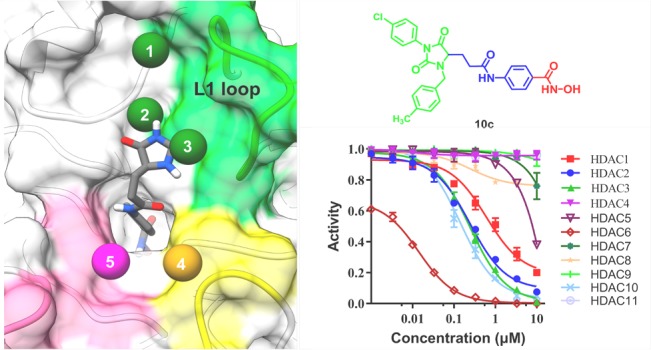

For potent compounds 10a, 10c, and 10f, we subsequently evaluated their HDAC inhibitory profile. IC50 values calculated from the dose–effect curve (SI Figure 11) indicated that all tested compounds exhibit good HDAC6 isoform selectivity (Table 2). It is worth mentioning that compound 10c possesses better HDAC6 selectivity compared to the positive control SAHA. Potent molecule 10c exhibits 218-fold selectivity against HDAC1 and more than 53-fold selectivity against HDAC2 and 3 as well as over 20000-fold selectivity against HDAC4, 7, 8, 9, and 11.

Table 2. HDACs Inhibitory Profiles of 10a, 10c, and 10f.

| IC50 (nM)a |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDAC isoform | 10a | 10c | 10f | SAHA |

| HDAC1 | 194 ± 13 | 959 ± 206 | 111 ± 30 | 46 ± 1 |

| HDAC2 | 249 ± 6 | 277 ± 17 | 203 ± 14 | 120 ± 7 |

| HDAC3 | 126 ± 13 | 235 ± 33 | 96 ± 16 | 35 ± 1 |

| HDAC4 | >100000 | >100000 | 27000 ± 6000 | >100000 |

| HDAC5 | 4600 ± 400 | 14900 ± 1700 | 4600 ± 600 | 41500 ± 10000 |

| HDAC6 | 9.7 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 7.6 ± 0.8 | 39.9 ± 9 |

| HDAC7 | 6000 ± 200 | >100000 | 8800 ± 1300 | 41800 ± 500 |

| HDAC8 | 6700 ± 700 | >100000 | 3600 ± 100 | 1800 ± 300 |

| HDAC9 | 9100 ± 800 | >100000 | 15200 ± 2900 | 64000 ± 8100 |

| HDAC10 | 268 ± 23 | 164 ± 10 | 114 ± 26 | 80 ± 8 |

| HDAC11 | >100000 | >100000 | >100000 | 40000 ± 3000 |

Assays were performed in replicate (n ≥ 2).

Research evidence revealed that HDAC6 inhibition induces apoptosis and suppresses the growth of carcinoma cells.23,24,33 Therefore, potent compounds (10a, 10c, and 10f) were chosen to evaluate their antiproliferative activities. The results (Table 3) suggested that compounds 10a, 10c, and 10f exhibit good antiproliferative activities against several tumor cell lines and that molecule 10c possesses better antiproliferative activities against HL-60 cell (IC50 = 0.25 μM) as well as RPMI-8226 cells (IC50 = 0.23 μM). Moreover, the antiproliferative activities of compound 10c against K562, HCT-116, and A549 cell lines were approximately three times that of the positive control SAHA.

Table 3. Antiproliferative Activities of 10a, 10c, and 10f.

| IC50 (μM)a |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | K562 | HL-60 | RPMI-8226 | HCT-116 | A549 |

| 10a | 0.69 ± 0.21 | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 0.36 ± 0.06 | 1.25 ± 0.07 | 5.86 ± 0.34 |

| 10c | 0.49 ± 0.10 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.83 ± 0.03 | 0.79 ± 0.07 |

| 10f | 0.83 ± 0.13 | 0.61 ± 0.03 | 0.64 ± 0.06 | 2.25 ± 0.12 | 9.45 ± 1.07 |

| SAHA | 1.45 ± 0.13 | 0.52 ± 0.08 | 0.57 ± 0.06 | 1.81 ± 0.17 | 2.42 ± 0.02 |

IC50 values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of three separate determinations.

To explore and verify the mechanism of the antiproliferative activity of target compounds, we further performed apoptotic assay (AnnexinV/PI staining), cell cycle analysis (PI staining), and caspase 3 activation in HL-60 cell. As shown in Figure 2A, compounds 10a and 10c exhibit mild apoptosis induction at 0.25 μM but exhibit strong apoptosis induction at 0.45 μM, whereas the positive control SAHA exhibits approximately no ability to induce apoptosis at different concentrations (0.25 μM, 0.45 μM). Cell cycle analysis (Figure 2B) showed that both 10a and 10c could induce cell cycle arrest at G1 phase and subG1 phase compared to the control (DMSO). Subsequently, caspase 3 activation assay was performed to explore the mechanism of apoptosis induction by potent compound 10c in HL-60 cell. After incubating HL-60 cells with various concentrations (0.25, 0.45, and 0.75 μM) for 24 and 48 h (Figure 2C), the amount of activated caspase 3 is significantly increased compared to control (untreated cells). Above research evidence indicated that compound 10c could induce apoptosis via activating caspase 3 in HL-60 cell.

Figure 2.

(A) Inducing apoptosis of HL-60 by 10a, 10c, and SAHA. (B) Cell cycle analysis for 10a, 10c, and SAHA against HL-60. (C) Fold increase of activated caspase 3 after treatment with compound 10c for 24 and 48 h in HL-60 cell. Data are expressed as mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments. Significant differences between treated cells with respect to control (untreated cells) are indicated as p < 0.05. (D) Levels of the acetylation of α-tubulin and H3 after treatment with compound 10c, ACY-1215, and SAHA in HL-60 cells at different concentrations for 24 h, respectively.

To confirm whether potent molecule 10c targets HDAC6 to exert antiproliferative activity, Western blot was performed. As shown in Figure 2D, SAHA increases the acetylation of α-tubulin (substrate for HDAC6) and the acetylation of H3 (a major substrate of class I HDACs), whereas ACY-1215 and compound 10c strongly increased the acetylation of α-tubulin with slight effect on H3 at low concentrations.

In summary, a series of 1,3-disubstituted 2,4-imidazolinedione derivatives were developed as HDAC6 selective inhibitors. Biological evaluations show that some compounds (10a, 10c, and 10f), especially compound 10c, exhibit good HDAC6 inhibitory activities, isoform-selectivities, and antiproliferative activities. Further studies revealed that potent molecule 10c could induce apoptosis by activating caspase 3 and significantly increase the acetylation of α-tubulin with little effect on the acetylation of H3. It is necessary to be noted that all target compounds are racemic and that developing a method for the separation of enantiomers is needed in future work. In addition, compound 10c may be used as a lead compound for the development of more potent and selective HDAC6 inhibitors.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- HDACs

histone deacetylase

- HATs

histone acetyltransferases

- ZBG

zinc binding group

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- HATU

1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium 3-oxid hexafluorophosphate

- DIPEA

N,N-diisopropylethylamine

- HeLa

human cervical cancer

- SAHA (vorinostat)

suberanilohydroxamic acid

- TSA

trichostatin A

- BSA

albumin from bovine serum

- His

histidine

- Tyr

tyrosine

- Phe

phenylalanine

- Ser

serine

- MTT

methylthiazolyldiphenyl-tetrazolium bromide

- K562

chronic myelogenous leukemia cell

- HL-60

human promyelocytic leukemia cell

- RPMI-8226

human multiple myeloma cell line

- HCT-116

human colon cancer cells

- A549

human lung cancer cells

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- ACY-1215

rocilinostat

- PI

propidium iodide

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00084.

Approved HDAC inhibitors and the well accepted pharmacophore of HDAC inhibitors; experimental methods; synthesis and characterization of target compounds 10a–10p; 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and HRMS spectra of representative compounds; HPLC analysis; HDAC6 and HDAC isoform inhibitory assay; in vitro antiproliferative assay (MTT assay); apoptosis and cell cycle analysis; caspase 3 activation assay; Western blot assay; molecular docking (PDF)

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81874288), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21672127), Key Research and Development Project of Shandong Province (Grant No. 2017CXGC1401), the Fundamental Research Funds of Shandong University (Grant No. 2019GN045), and The Joint Research Funds for Shandong University and Karolinska Institute (SDU-KI-2019-06).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Nebbioso A.; Clarke N.; Voltz E.; Germain E.; Ambrosino C.; Bontempo P.; Alvarez R.; Schiavone E. M.; Ferrara F.; Bresciani F.; Weisz A.; Lera A. R.; Gronemeyer H.; Altucci L. Tumor-selective action of HDAC inhibitors involves TRAIL induction in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 77–84. 10.1038/nm1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger G.; Liang G.; Aparicio A.; Jones P. A. Epigenetics in human disease and prospects for epigenetic therapy. Nature 2004, 429, 457–463. 10.1038/nature02625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peserico A.; Simone C. Physical and functional HAT/HDAC interplay regulates protein acetylation balance. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011, 2011, e371832 10.1155/2011/371832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y. J.; Liu Z. B.; Wang W. G.; Sun C. B.; Wei P.; Yang Y. L.; You M. J.; Yu B. H.; Li X. Q.; Zhou X. Y. HDAC6 regulates microrna-27b that suppresses proliferation, promotes apoptosis and target met in diffuse large b-cell lymphoma. Leukemia 2018, 32, 703. 10.1038/leu.2017.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pande A. N.; Biswas S.; Reddy N. D.; Jayashree B.; Kumar N.; Rao M. C. In vitro and in vivo anticancer studies of 2’-hydroxy chalcone derivatives exhibit apoptosis in colon cancer cells by hdac inhibition and cell cycle arrest. Excli. J. 2017, 448–463. 10.17179/excli2016-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvic M.; Vu J. Vorinostat: a new oral histone deacetylase inhibitor approved for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 2007, 16, 1111–1120. 10.1517/13543784.16.7.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker S. J.; Demierre M. F.; Kim E. J.; Rook A. H.; Lerner A.; Duvic M.; Scarisbrick J.; Reddy S.; Robak T.; Becker J. C.; Samtsov A.; McCulloch W.; Kim Y. H. Final results from a multicenter, international, pivotal study of romidepsin in refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 4485–4491. 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.9066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole R. M. Belinostat: first global approval. Drugs 2014, 74, 1543–1554. 10.1007/s40265-014-0275-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnockjones K. P. Panobinostat: First Global Approval. Drugs 2015, 75, 695–704. 10.1007/s40265-015-0388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning Z.; Li Z.; Newman M. J.; Shan S.; Wang X.; Pan D.; Zhang J.; Dong M.; Du X.; Lu X. Chidamide (CS055/HBI-8000): a new histone deacetylase inhibitor of the benzamide class with antitumor activity and the ability to enhance immune cell-mediated tumor cell cytotoxicity. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2012, 69, 901–909. 10.1007/s00280-011-1766-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson P. G.; Harvey R. D.; Laubach J. P.; Moreau P.; Lonial S.; San-Miguel J. F. Panobinostat for the treatment of relapsed or relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: pharmacology and clinical outcomes. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 9, 35–48. 10.1586/17512433.2016.1096773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers Z. T.; Oostra D. R.; Westholder J. S.; Vercellotti G. M. Romidepsin-associated cardiac toxicity and ecg changes: a case report and review of the literature. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2018, 24, 56–62. 10.1177/1078155216673229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith N.; Nucera C. Personalized therapy in patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer: targeting genetic and epigenetic alterations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 35–42. 10.1210/jc.2014-2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Veggel M.; Westerman E.; Hamberg P. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of panobinostat. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2018, 57, 21–29. 10.1007/s40262-017-0565-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H.; Cao J.; Xu W. Selective histone deacetylase inhibitors. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 247–270. 10.2174/187152012800228814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela-Fernandez A.; Cabrero J. R.; Serrador J. M.; Sanchez-Madrid F. HDAC6: a key regulator of cytoskeleton, cell migration and cell–cell interactions. Trends Cell Biol. 2008, 18, 291–297. 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ageta-Ishihara N.; Miyata T.; Ohshima C.; Watanabe M.; Sato Y.; Hamamura Y.; Higashiyama T.; Mazitschek R.; Bito H.; Kinoshita M. Septins promote dendrite and axon development by negatively regulating microtubule stability via hdac6-mediated deacetylation. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2532. 10.1038/ncomms3532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosik L.; Niegisch G.; Fischer U.; Jung M.; Schulz W. A.; Hoffmann M. J. Limited efficacy of specific HDAC6 inhibition in urothelial cancer cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2014, 15, 742–757. 10.4161/cbt.28469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haakenson J.; Zhang X. HDAC6 and ovarian cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 9514–9535. 10.3390/ijms14059514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q.; Li G.; Wang X.; Wang S.; Hu J.; Yang L.; He Y.; Pan Y.; Yu D.; Wu Y. A decrease of histone deacetylase 6 expression caused by helicobacter pylori infection is associated with oncogenic transformation in gastric cancer. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 42, 1326–1335. 10.1159/000478961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auzzas L.; Larsson A.; Matera R.; Baraldi A.; Deschenes-Simard B.; Giannini G.; Cabri W.; Battistuzzi G.; Gallo G.; Ciacci A.; Vesci L.; Pisano C.; Hanessian S. Non-natural macrocyclic inhibitors of histone deacetylases: design, synthesis, and activity. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 8387–8399. 10.1021/jm101092u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.; Wang T.; Wang F.; Niu T.; Liu Z.; Chen X.; Long C.; Tang M.; Cao D.; Wang X.; Xiang W.; Yi Y.; Ma L.; You J.; Chen L. Discovery of Selective Histone Deacetylase 6 Inhibitors Using the Quinazoline as the Cap for the Treatment of Cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 1455–1470. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y.; Lim J.; Seo Y. H. A novel class of anthraquinone-based HDAC6 inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 164, 263–272. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogerl K.; Ong N.; Senger J.; Herp D.; Schmidtkunz K.; Marek M.; Müller M.; Bartel K.; Shaik T. B.; Porter N. J.; Robaa D.; Christianson D. W.; Romier C.; Sippl W.; Jung M.; Bracher F. Synthesis and biological investigation of phenothiazine-based benzhydroxamic acids as selective histone deacetylase 6 inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 1138–1166. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand P. Inside HDAC with HDAC inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 2095–2116. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Sun F.; Han L.; Hou X.; Pan X.; Liu R.; Tang W.; Fang H. Design, synthesis, and preliminary bioactivity studies of substituted purine hydroxamic acid derivatives as novel histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors. MedChemComm 2014, 5, 1887–1891. 10.1039/C4MD00203B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rooklin D.; Modell A. E.; Li H.; Berdan V.; Arora P. S.; Zhang Y. Targeting unoccupied surfaces on protein–protein interfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 15560–15563. 10.1021/jacs.7b05960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hai Y.; Christianson D. W. Histone deacetylase 6 structure and molecular basis of catalysis and inhibition. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016, 12, 741–747. 10.1038/nchembio.2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyelere A.; Gryder B.. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors targeting prostate tumors and methods of making and using thereof. WOUS9139565[P], 2015.

- Butler K. V.; Kalin J.; Brochier C.; Vistoli G.; Langley B.; Kozikowski A. P. Rational design and simple chemistry yield a superior, neuroprotective HDAC6 inhibitor, Tubastatin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 10842–10846. 10.1021/ja102758v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake Y.; Keusch J. J.; Wang L.; Saito M.; Hess D.; Wang X.; Melancon B. J.; Helquist P.; Gut H.; Matthias P. Structural insights into HDAC6 tubulin deacetylation and its selective inhibition. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016, 12, 748–754. 10.1038/nchembio.2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy A. S.; Kumar M. S.; Reddy G. R. A convenient method for the preparation of hydroxamic acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 6285–6288. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)01058-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J.; Zheng N.; Wang X.; Tang C.; Yan P.; Zhou H. B.; Huang J. A novel HDAC6 inhibitor exerts an anti-cancer effect by triggering cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in gastric cancer. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 828, 67–79. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.