Abstract

Beam angle configuration is a major planning decision in Intensity Modulated Radiation Treatment (IMRT) that has a significant impact on dose distributions and thus quality of treatment, especially in complex planning cases such as those for lung cancer treatment. We propose a novel method to automatically determine beam configurations that incorporates noncoplanar beams. We then present a completely automated IMRT planning algorithm that combines the proposed method with a previously reported OAR DVH prediction model. Finally, we validate this completely automatic planning algorithm using a set of challenging lung IMRT cases. A beam efficiency index (BEI) map is constructed to guide the selection of beam angles. This index takes into account both the dose contributions from individual beams and the combined effect of multiple beams by introducing a beam-spread term. The effect of the beam-spread term on plan quality was studied systematically and the weight of the term to balance PTV dose conformity against OAR avoidance was determined. For validation, complex lung cases with clinical IMRT plans that required the use of one or more noncoplanar beams were re-planned with the proposed automatic planning algorithm. Important dose metrics for the PTV and OARs in the automatic plans were compared with those of the clinical plans. The results are very encouraging. The PTV dose conformity and homogeneity in the automatic plans improved significantly. And all the dose metrics of the automatic plans, except the lung V5Gy, were statistically better than or comparable with those of the clinical plans. In conclusion, the automatic planning algorithm can incorporate non-coplanar beam configurations in challenging lung cases and can generate plans efficiently with quality closely approximating that of clinical plans.

Keywords: beam angle configuration, beam angle optimization, automatic IMRT planning, lung cancer

1. Introduction

Beam angle configuration is a major planning decision affecting dose distributions in 3D CRT and IMRT planning. While beam configuration can usually be fixed in simpler cases (e.g. prostate), it must be customized for complex cases. Due to variations in tumor location, size and patient anatomy, selection of beam angles is a critical component of planning for the thorax, abdomen, and lung, as it offers another dimension to negotiate organ sparing. In clinical practice, beam angles are often selected based on a planner’s experience and adjusted through a trial-and-error process to form an optimal set of beam bouquet. While it has been shown that the non-coplanar beam configurations can improve the dosimetric quality in many lung IMRT plans (Zhang et al., 2011; Dong et al., 2013), noncoplanar beams are used less efficiently in current clinical practices because the planners usually have less experience with them.

Beam angle optimization in IMRT planning is a large scale combinatorial optimization problem; many methods have been developed to improve its time efficiency. Some studies carried out global optimizations to optimize the beam angles and the fluence map for each beam simultaneously (Wang et al., 2005; Jia et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2013; Pugachev et al., 2001; Li et al., 2004; Dong et al., 2013; Zarepisheh et al., 2015; Bangert and Unkelbach, 2016; Liu et al., 2017). However, these methods require a large amount of time to perform the iterative optimization process. To determine the beam angles automatically within a clinically practical timeframe, some studies perform beam angle selection by sequentially adding (Breedveld et al., 2012; Popple et al., 2014; Das et al., 2003) or eliminating (Zhang et al., 2011) single candidate beams to the treatment plan in an iterative manner.

There have also been studies to develop population-based class-solution of beam bouquets (i.e., entire beam configuration settings) for certain treatment sites (Abraham et al., 2013; Schreibmann and Xing, 2004). In a recent study, the standardized set of six beam bouquets was determined for lung IMRT planning by learning the beam configuration features from clinical plans by a cluster analysis method (Yuan et al., 2015).

A different kind of beam angle selection method which is not restricted to a fixed set of beams has also been proposed (Dink et al., 2012). This method allows a wider array of beam directions to be used over the entire treatment course by alternating multiple of sets of beams across fractions. The number of fractions which utilize each set of beam angles is optimized by a mixed integer linear programing (MILP).

One promising approach to efficient beam angle selection is to somehow estimate the quality of a beam angle without expensive dose calculation, optimization, or iterations. A number of metrics have been defined to score and rank candidate beam directions according to the patients’ anatomical features and physics principles. In Pugachev et al. (Pugachev and Xing, 2001; Schreibmann and Xing, 2005), a score is calculated for each given beam angle as the maximum dose delivered to the target by the beam without violating OAR dose constraints. In Potrebko et al., purely geometrical features are used to rank the beam directions (Potrebko et al., 2008). The preferential beam directions are those that bisect the target and adjacent OARs and parallel to 3D flat surface features of the PTV. These methods only produce the initial set of beams in a beam configuration. An iterative optimization process follows to find the final beam angles setting. Another set of methods for determining the beam angles are directly based on the beam angle scores. In Meyer, et.al. (Meyer et al., 2005), a birds-eye-view (BEV) ray-tracing method is used to calculate a score function for each direction. The dose in PTV and OARs is estimated by the depth and the path length inside them. In Bangert et al. (Bangert and Oelfke, 2010), a radiological quality index is computed for each voxel and along each potential beam angle. The locally preferred beam angles for individual voxels are selected based on the indices and the cluster centers of these angles are extracted as the beam configuration for a plan. In Amit et al., a machine learning method was utilized to learn the relationships between beam angles and anatomical features for co-planar beam cases (Amit et al., 2015).

We note that the existing methods for beam angle selection suffer from a number of drawbacks. Many of them are too time consuming to be used in routine clinical practice. Some are too simplistic to handle complex cases such as the challenging lung cancer cases. Results from recent studies also indicate that many plans generated by the automated methods have worse target dose conformity and homogeneity compared with the clinical plans or the plans generated by other methods (Bangert et al., 2013; Amit et al., 2015).

In this study, we present a method for automatic determination of beam configurations in IMRT that is capable of handling complex cases by incorporating noncoplanar beams. We demonstrate that the proposed method is effective in planning of challenging lung cases and results in high quality plans which are comparable to or even superior to clinical plans. After the beam configuration is determined, the fluence map or MLC segments for each individual beam is optimized based on a set of dose coverage and dose sparing objectives. To take full advantage of past experience and knowledge in order to improve the efficiency and quality of IMRT planning, we have further developed a fully automatic planning method which combines the automatic method for beam angle selection with a previously reported method for automatic determination of OAR dose objectives (Yuan et al., 2012; Giaddui et al., 2016).

2. Methods

2.1. Patient data

A dataset consisting of seventy two (72) clinical lung IMRT plans is utilized to develop and test the algorithm for automatic determination of beam angle configuration and the OAR DVH prediction models under an IRB approved research protocol. The prescription dose in these plans ranges from 60 Gy to 70 Gy. The dataset has a wide range of tumor size (from 12 to 1132 cm3, mean 308 cm3) and locations. The distribution of the cases by tumor location is: 26 cases in the right lung, 31 in the left lung, 12 in the mediastinum and 3 in the chest wall. The number of beams used in the treatment plans ranges from six to eleven. Within the 72 clinical cases, 14 were challenging cases that required the use of one or more noncoplanar beams. The average target volume within these noncoplanar cases is 336.0 cm3 (range: 151.48 to 521.20 cm3). Thus, in this study, we chose to use the 58 co-planar plans for development and training and the 14 noncoplanar plans for validation.

2.2. Automatic determination of beam angle configuration

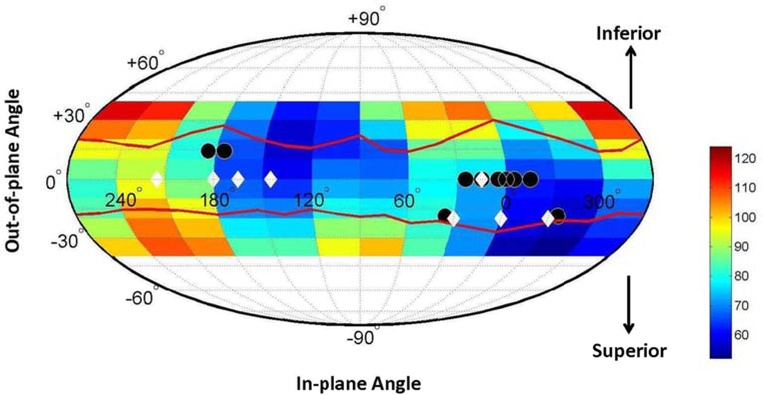

A beam efficiency index (BEI) map is constructed to characterize the shape and position of the tumor relative to the body, the lung and other OARs in each candidate beam angle. The beam angle search space includes all combinations of gantry and couch angles that do not cause potential collision with the patient. In this study, a common admissible gentry-couch angle space is used for all patients based on the collision chart obtained in a previous study (Becker, 2011). This chart has been verified with Varian linac and a patient immobilization device (Alpha Cradle, Smithers Medical Products, Inc., North Canton, Ohio) in our clinics. The admissible angle space is shown in Fig. 1 as the inside region between the two red lines.

Figure 1.

Beam efficiency index map for non-coplanar beam angles plotted as Mollweide projection for an example case. It is color coded with arbitrary unit. “Colder” colors represent smaller BEI values and thus superior beam angles. The solid circles indicate the beam angles in the clinical plans and the diamonds indicate the beam angles generated by the automatic planning method.

We first define a voxel-level beam efficiency index (BEI) qαv for each voxel v inside a target volume and along the beam direction with a directional angle α. BEI is a function f of the integrated dose dαv deposited in the target volume, the OAR, and other normal tissues (NT) along the particular beam path. The attenuation of the primary beam and the lung tissue inhomogeneity are taken into account using a pencil beam model. Scattered dose is ignored for the sake of calculation efficiency. An intuitive functional form for f is the ratio of the weighted sum of the dose deposited inside the lung and other OARs to the dose in the PTV:

where the w’s are the relative weights which indicate the contribution of the dose deposits in different structures to the beam efficiency index. The represent the dosimetric tolerance of different organs and the planner’s tradeoff preferences among different OARs. A smaller qαv suggests a better beam angle since dose in OARs is relatively smaller in this direction. The ΓTarget term is a regularization parameter to avoid the divergence of the index when the beam passing through the target approaches 0. Next, we define the voxel-independent beam efficiency index qα for each candidate beam angle by averaging qαv across all voxels on the PTV surface.

We determined the value of weighting factors empirically in this study to be those that generate beam configurations most consistent with the beam angles used in clinical plans. We evaluated the total dissimilarity between the beams angles in the clinical plans and the automatically generated beam configuration with different weighting factor values based on a dissimilarity measure defined in a previous study (Yuan et al., 2015). In this study, the parameter values were chosen to minimize the dissimilarity for a subset of the clinical cases that used only co-planar beams. This serves two purposes. First, the relatively large number of co-planar plans provides more reliable estimates of the parameters. Second, we aim to show that our model is able to capture planner’s knowledge of planning preferences reflected in their clinical co-planar plans and extend it to noncoplanar planning. Owing to the nonlinearity and the highly nonconvex feature of how the dissimilarity varies with the parameters values (the weights), a grid search method was used to find the set of weights to minimize the dissimilarity.

For noncoplanar beams, the directional angle α has two components, the azimuthal (in-plane) angle βa and elevation (out-of-plane) angle βe. The distribution of the BEI in the noncoplanar angle space forms a beam efficiency index map. In our current formulation, smaller values on the map indicate more preferred beam directions. It can be visualized as a Mollweide projection on angle space (Fig. 1).

Up to this point, the definition of BEI takes into account only the effect of a single beam. To represent the combination effects of multiple beams, an additional constraint on beam angle selection is introduced. It has been recognized that the separation between beams affect the dosimetric quality, in particular, larger beam spread generally leads to better PTV dose conformity (Meyer et al., 2005; Amit et al., 2015). Thus, a term representing a measure of beam spread is added to the beam efficiency index based on a spring-coupled mass model. This beam spread term resembles the elastic potential energy between a pair of masses, which is inversely proportional to the angle separation between each pair of beams αij. So the total efficiency index (TEI) value for a beam configuration {αi, i = 1, …, n} with n beams becomes:

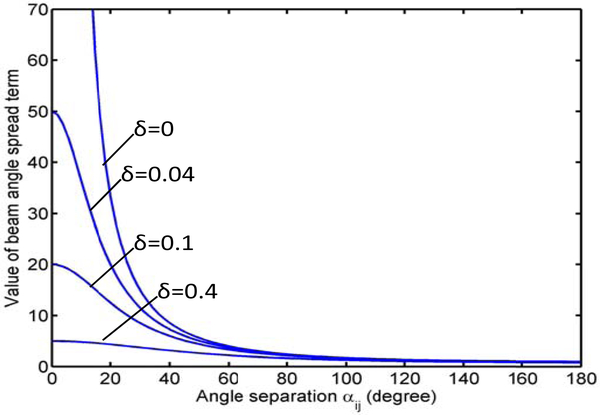

where αij is the angle separation between angles αi and αj, δ is a regularization parameter to avoid the singularity when αij = 0, δ ≪ 1, and k represents the relative importance of beam separation to beam angle selection. The plots of the beam spread terms with a number of different values of δ are shown in Fig. 2. As we can see, a larger beam angle separation will lead to smaller TEI value which will be considered as a more preferred beam arrangement during optimization. The term becomes more flat with larger δ values. A δ value of 0.04 is used in this study. The choice of k should balance the need for OAR avoidance and beam angle spread. In order to study the variation of plan quality as the parameter value changes, we carried out a sensitivity analysis as a part of our evaluation process in which different beam angle sets were generated with varying values of the parameter.

Figure 2.

Plots of the beam spread terms with different values of δ as functions of the angle separation between a pair of beams

Based on the concept of beam efficiency index map, the optimal beam angle configuration is determined by finding a set of beam angles that minimizes the TEI through a greedy algorithm. Considering that the number of noncoplanar beams in the clinical plans ranges from 1 to 5, and most noncoplanar clinical plans uses 4 noncoplanar beams, we restrict the number of noncoplanar beams in our automatic planning method to half the total number of beams (4). The initial beam angle search space includes all of the 4π space excluding areas of potential gantry-patient collision. At each step, the beam direction corresponding to the minimum value of the total efficiency index is added to the set of selected beams. If 4 noncoplanar beams have already been selected, the search space will be limited to coplannar beam angles only, so that no more than 4 noncoplanar beams are used in each plan for the purpose of better delivery efficiency and to be consistent with the clinical plans.

2.3. Automated lung IMRT planning

After the beam configurations are determined, the fluence map for each individual beam is optimized based on a set of target dose coverage and OAR dose sparing objectives. In this study, the patient specific OAR dose sparing objectives are generated by utilizing the OAR DVH prediction models which correlate the anatomical features with the dosimetric features embedded in prior clinical IMRT plans (Yuan et al., 2012). The anatomical features used in the model are: The distance-to-target histogram (DTH) and their components along the three cardinal directions and a number of volumetric factors. Specific dose-volume points and mean or maximum dose are sampled from the DVHs and are used as planning objectives. In addition, the dose coverage objectives for the PTV and the optimization priority for each objective are pre-determined based on past IMRT planning experience and are not adjusted during optimization.

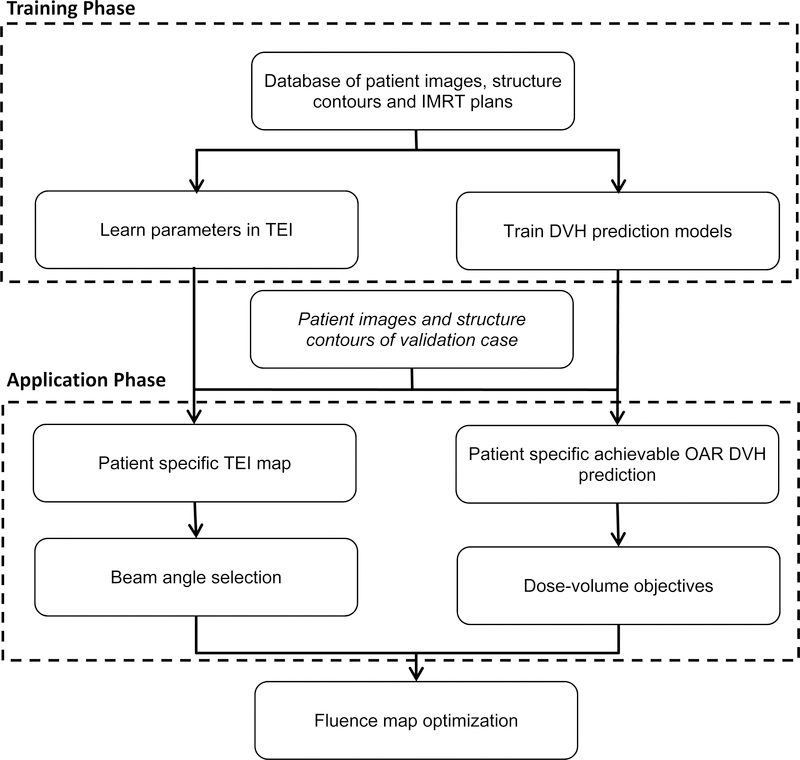

The automated planning method combines the automatic beam angle selection method with the automatic determination of dose objectives. It consists of three major phases: training, application and fluence map optimization. In the training phase, the models and relevant parameters are learned from high quality prior clinical plans. In the application phase, the method consists of two major steps for each new patient case. In the first step, the beam angles are determined from the patient specific TEI map and the dose-volume objectives are generated. Specific dose-volume points and mean or maximum dose are sampled from the DVHs and are used as planning objectives. Because of the quadrature format of the objective functions in our TPS, we used the lower 1-sigma limit of the predicted achievable DVH to generate the IMRT optimization objectives. In the second step, the plan optimization objectives are written into objective templates and the beam angle settings are written as plan templates. These templates are directly imported into Eclipse (version 13, Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA) for fluence map optimization and leaf sequencing. The overall workflow for this automated planning method is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

The overall workflow for the automated planning method is shown in the diagram. It consists of training, application and fluence map optimization phases.

2.4. Evaluation

The fourteen complex lung cases with their clinical IMRT plans employing at least one noncoplanar beam were re-planned by the automated planning method. The number of beams used in the clinical plans for these validation cases ranges from 8 to 11. We chose to use eight beams for all the cases in the automatically generated plans (auto-plans) because 8 beams provide a good compromise between plan quality and delivery efficiency based on prior studies (Liu et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2011). In addition, to study the sensitivity of plan quality to the coefficient k of the beam spread term, we generated, for each case, six beam angle configurations and auto-plans for six different values of k within the range [0,1] by an increment of 0.2.

We performed quantitative assessment of the quality of the auto-plans as compared with clinical plans. Important dosimetric parameters were extracted from both clinical plans and auto-plans to quantify the quality of OAR dose sparing and PTV dose coverage. The PTV dosimetric parameters include dose conformity (The volume enclosed by prescription isodose surface divided by the PTV volume), homogeneity (D2%-D99%) and D2cm (Maximal dose farther than 2 cm away from PTV which indicates hot spot outside PTV). These parameters have been used for plan evaluation and reporting in a number of IMRT planning protocols (Li et al., 2012; Bradley et al., 2015; Gregoire et al., 2010) and a prior study (Nelms et al., 2013).

The quantitative analysis was done in two steps. First, the variation of plan dose metrics as the beam spread term coefficient changes was investigated and the value for the coefficient was determined based on this study. A composite plan dose metrics was constructed based on the relative differences between the metrics in the auto-plans and clinical plans as:

where and are the ith dose metrics in auto-plans and clinical plans, respectively, and wi is the relative weight. We used an equal weight for all the dose metrics in this study. The dose metrics are: CI, HI, D2cm, spinal cord and cord+3mm (spinal cord with 3mm margin) maximum dose, lung V5Gy, V20Gy and Dmean, Esophagus V60Gy, Dmean, heart V40Gy and Dmean. The meaning of these OAR dose metrics are given in table 1. In the second step, the auto-plans, as a whole group, were compared with the clinical plans by a Wilcoxon signed-rank test in terms of each dosimetric index.

Table 1.

The mean and standard deviation of the dose metrics over all automatic plans and those in the clinical plans are listed. The p-values by Wilcoxon signed-rank test are also shown.

| Structure | Dose Metrics | Clinical (mean±s.d.) | Auto-plans (mean±s.d.) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTV | CI | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.0002 |

| HI (%) | 14.3 ± 4.2 | 11.4 ± 1.8 | 0.009 | |

| D2cm (%) | 109.3 ± 6.4 | 103.1 ± 8.3 | 0.0081 | |

| Lungs | V5Gy (%) | 54.0 ± 11.3 | 57.4 ± 9.7 | 0.0129 |

| V20Gy (%) | 26.7 ± 6.2 | 27.7 ± 5.9 | 0.1528 | |

| Dmean (%) | 15.3 ± 3.2 | 15.4 ± 3.1 | 0.9395 | |

| Esophagus | V60Gy (%) | 26.2 ± 15.4 | 26.1 ± 16.4 | 0.7148 |

| Dmean | 32.5 ± 9.6 | 32.7 ±10.5 | 0.9153 | |

| Heart | V40Gy (%) | 17.2 ± 12.3 | 11.9 ± 11.6 | 0.0012 |

| Dmean (%) | 17.7 ± 11.0 | 15.5 ± 10.0 | 0.0465 | |

| Cord+3mm | Dmax (%) | 46.4 ± 6.3 | 47.0 ± 6.6 | 0.6816 |

Abbreviations: s.d.: standard deviation, VxGy: portion of OAR volume irradiated by dose higher than x Gy (Unit: percertage of OAR volume), Dmax: maximum dose (Unit: percentage of prescription dose), Dmean: mean dose (Unit: percentage of prescription dose).

3. Results

To determine the weighting factors in the model, the TEI for each of the 58 co-planar cases were calculated with varying values of the dose deposit weights wi in different structures. Beam angles were automatically determined from the TEI map. The total dissimilarity between the beams angles in the clinical plans and the automatically generated beam configuration were evaluated for different weighting factor values. We used a grid search method to find the set of the parameter values to minimize the dissimilarity. It is found that the combination of the weights which minimize the dissimilarity is (wlung, wheart) = (1.0, 0.3). For the series organs such as spinal cord which have hard dose constraints, higher weight values (10) are assigned to them to ensure that beam doesn’t directly go through them.

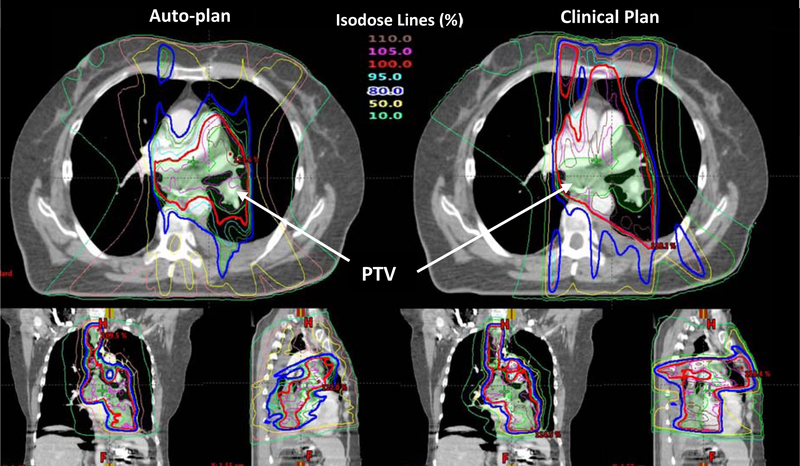

Next, The BEI map for each of the 14 noncoplanar validation cases were calculated. The BEI map and the automatically determined angle for one case are shown in Fig. 1 as an example. Eight beams were used in this case as were in all automatic plans. Fluence map optimization was done subsequently using automatically generated planning objectives. The isodose distributions in the auto-plan and the clinical plan for this case are compared in Fig. 4. As can be seen in this figure, the 100% isodose line in the auto-plan better conforms to the PTV than the clinical plan, while the dose sparing of the lung in the mid-dose range (50%) appears comparable.

Figure 4.

The isodose distributions in the auto-plan (left) and the clinical plan (right) for an example validation case are shown. The color coding for the isodose lines is shown in the figure. The dose unit in the table is percentage of the prescription dose (60Gy).

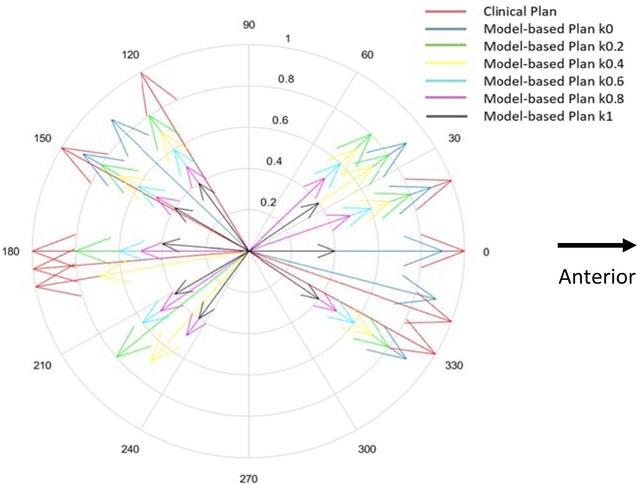

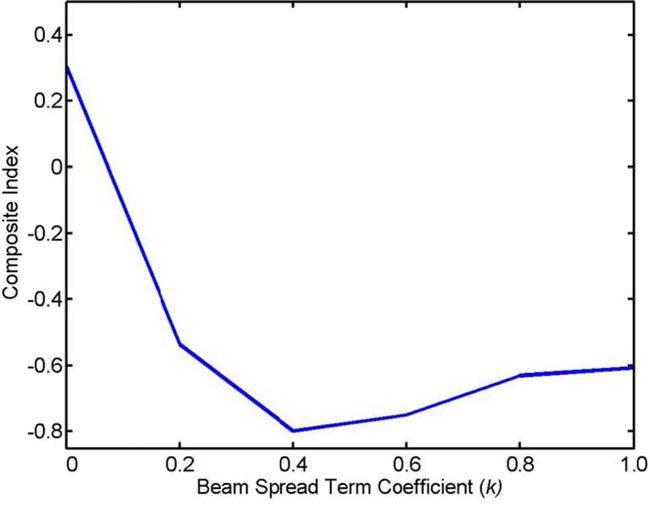

To illustrate the effect of coefficient k on beam angle selection, the gantry angle components of the beam angles in the clinical plan and the auto-plan for an example case are show in Fig. 5. The longest arrows represent the beams (nine beams) in the clinical plan and others with various lengths indicate the beam angle in the auto-plans. The different colors of the arrows correspond to different values of coefficient k. It can be seen that beams in all plans distribute over the same regions anteriorly and posteriorly, mainly to minimize the beam penetration through the lungs and other critical organs. In addition, the beam set with coefficient k = 0 has the most compact distribution as expected. The DVHs in the auto-plans generated with different values of k were compared with those in the clinical plans in Figure A1 in the supplementary material. Furthermore, dose metrics were extracted from the clinical plans and the auto-plans. We calculate the composite dosimetric index I defined above and plot it as a function of k in Fig. 6. As shown in the plot, the composite dosimetric index reaches a broad minimum when k value is in the range between 0.4 and 0.6. We used a value of 0.4 throughout the study.

Figure 5.

Diagram showing the gantry angle components of the beam angles in the clinical plan and the auto-plan for an example case. The longest arrows represent the beams (nine beams) in the clinical plan and others with various lengths indicate the beam angle (eight beams) in the auto-plans. The different colors of the arrows correspond to different value of coefficient k.

Figure 6.

Composite dosimetric index shown as a function of coefficient k of the beam spread term

The DVHs in the auto-plans generated with different values of k were compared with those in the clinical plans in Figure A1 in the supplementary material. The dose metrics were extracted from the auto-plans generated with k = 0.4 and they are compared with those in the clinical plans (Table A1 in the supplementary material). The mean and standard deviation of these parameters over all automatic plans and those in the clinical plans are shown in Table 1. As we can see, except Lung V5Gy, which is about 3.4% higher in auto-plans on average (p-value: 0.013), all the other dosimetric parameters in the auto-plans are statistically better or comparable with those in the clinical plans. The most significant improvements are for the PTVs and heart. We observe significant improvement in PTV dose conformity and homogeneity.

4. Discussion

IMRT has enabled better sparing of normal organs in the treatment of lung cancer compared with three-dimensional techniques (Liao et al., 2010; Ling et al., 2016). In our clinics, lung IMRT is generally used to treatment large tumors or centrally located tumors close to the OARs. Because noncoplanar beams require additional treatment setup time to rotate the couch and have higher risk of gantry-couch collision, they are used less frequently and thus the planners usually have less experience with their planning. Within the 72 lung IMRT cases we have studied, only 14 plans used noncoplanar beams and many of them are the same sets of angles from a template. Many IMRT plans in our database, especially those using noncoplanar angles, are complicated case in terms of tumor geometry and/or patient anatomy. The noncoplanar beams are employed mainly to further improve the dose sparing of the heart, esophagus or spinal cord. It took multiple hours to generate a clinically acceptable plan for these complex cases.

By means of the knowledge-based automatic IMRT planning algorithm, the planning efficiency was greatly improved; typically, a plan was completed within an hour. The automatic planning method also ensures a consistent plan quality. This can be attributed to the good quality of the beam configurations determined by the beam angle selection method and the optimization objectives predicted by the OAR DVH prediction models. A prospective study is needed in order to perform a more systematic planning efficiency comparison.

The PTV dose conformity in lung IMRT plans is an important plan quality metric (Chun et al., 2017). It has been recognized that dose conformity is affected by the combined effect of multiple beams, and in particular, the spread of beam arrangement (Meyer et al., 2005). Many plans generated by previous automatic beam angle selection methods have inferior dose conformity compared with clinical plans, possibly because the effects of multiple beams are not fully taken into account (Amit et al., 2015; Bangert et al., 2013). Instead of imposing a hard constraint on minimum beam separation as in (Meyer et al., 2005), we introduced the beam spread term in the BEI and investigated the effect of beam spread systematically. The optimal choice of the coefficient of this term to balance OAR avoidance and beam angle spread was determined from this study.

In this study, we developed beam efficiency index (BEI) map to guide the automatic selection of beam angles. The beam efficiency index (BEI) map is a novel representation that captures both physics principle and planner’s experience of planning preferences. We further utilized a dissimilarity measure to compare the difference between the beams angles in the clinical plans and the automatically generated beam configuration. This dissimilarity measure is defined on a high-dimensional non-Euclidean space. The formulization of the BEI and the dissimilarity measure allow us to determine beam configuration by a machine learning method. RT plan optimization is a process of trade-off between different optimization objectives. In this method, the beam configurations and dose objectives are determined by taking into account the physician and planner’s trade-off preferences embedded in existing clinical plans.

In addition, we introduced the beam spread term in the BEI and investigated the dosimetric effect of beam spread systematically. The optimal choice of the weight for this term to balance OAR avoidance and beam angle spread was determined from this study. This beam spread term reflects the requirement of multiple optimization objectives in plan optimization and the nonconvex feature of the beam angle searching space. Using this term overcomes the shortcoming of PTV dose conformity in previous methods.

This fully automatic method combines the automatic beam angle selection method with automatic determination of dose objectives. Although knowledge-based IMRT planning methods have been evaluated in previous studies to automatically generate dose objectives (Snyder et al., 2016), only limited number of predetermined beam configuration templates were used in those studies. The suboptimal beam placement increases the dose to certain OARs.

In terms of dose metrics, the auto-plans have better PTV conformity and better heart sparing than the clinical plans. However, lung V20Gy in auto-plans is 1% of lung volume higher and V5Gy 3.4% higher on average. The worse lung indices reflect the limitation of our current training data set and learning strategy. In this study, the relative weights for different OARs and the OAR dose sparing objectives used in plan optimization are learned from past planning experience empirically. Because the noncoplanar cases currently only account for about 20% of the total cases, our strategy was to learn the parameters from the coplanar cases and apply them to the non-coplanar cases. While the proposed algorithm already demonstrates a number of dosimetric advantages, the parameters learned from the usually simpler coplanar cases may not represent the best choices for the more complex non-coplanar cases. Thus, we expect our algorithm to significantly outperform manual methods when we accumulate sufficiently more non-coplanar cases in the training data set. In addition, we can improve our algorithm further by adding effective means to give user the option to adjust these weights for special cases to satisfy the physician’s dose sparing preferences and the patient’s clinical conditions.

Furthermore, we recognize that the quality of a plan may not be completely represented by these dosimetric parameters. Thus we are also planning a larger prospective study to further assess both the efficiency and quality of the automatic planning algorithm and invite clinicians specialized in lung cancer treatment to evaluate the quality of the auto-plans and compare them with clinical plans.

Aside from lung IMRT, the RT planning of many other treatment sites can benefit from noncoplanar beams. This includes abdomen, head and neck, and brain. The proposed beam angle selection method and the automated planning algorithm can be easily extended to these cancer sites by learning the structure weights and beam spread term coefficient in TEI from corresponding clinical cases to reflect the OAR dose sparing and PTV dose conformity preferences of the specific treatment sites.

5. Conclusion

We have proposed and studied a novel beam efficiency index (BEI) map to guide the automatic selection of beam angles that incorporate non-coplanar beam configurations. This index takes into account both the requirement of OAR avoidance and PTV conformity in beam angle selection. We have also evaluated a fully automated lung IMRT planning algorithm that combines the automatic beam angle selection method and a method for automatic determination of dose objectives using an OAR DVH prediction model. Initial results demonstrate that the automatic planning algorithm can incorporate non-coplanar beam configurations in challenging lung cases and can generate plans efficiently with quality closely approximating that of clinical plans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported in part by a grant from NIH/NCI under grant number R01CA201212 and a master research grant from Varian Medical Systems.

References

- Abraham C, Molinari N and Servien R 2013. Unsupervised clustering of multivariate circular data Statistics in Medicine 32 1376–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amit G, Purdie TG, Levinshtein A, Hope AJ, Lindsay P, Marshall A, Jaffray DA and Pekar V 2015. Automatic learning-based beam angle selection for thoracic IMRT Med Phys 42 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangert M and Oelfke U 2010. Spherical cluster analysis for beam angle optimization in intensity-modulated radiation therapy treatment planning Phys Med Biol 55 6023–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangert M and Unkelbach J 2016. Accelerated iterative beam angle selection in IMRT Medical Physics 43 1073–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangert M, Ziegenhein P and Oelfke U 2013. Comparison of beam angle selection strategies for intracranial IMRT Med Phys 40 011716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SJ 2011. Collision indicator charts for gantry-couch position combinations for Varian linacs JOURNAL OF APPLIED CLINICAL MEDICAL PHYSICS 12 16–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley JD, Paulus R, Komaki R, Masters G, Blumenschein G, Schild S, Bogart J, Hu C, Forster K, Magliocco A, Kavadi V, Garces Y I, Narayan S, Iyengar P, Robinson C, Wynn RB, Koprowski C, Meng J, Beitler J, Gaur R, Curran W and Choy H 2015. Standard-dose versus high-dose conformal radiotherapy with concurrent and consolidation carboplatin plus paclitaxel with or without cetuximab for patients with stage IIIA or IIIB non-small-cell lung cancer (RTOG 0617): a randomised, two-by-two factorial phase 3 study The lancet oncology 16 187–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breedveld S, Storchi PR, Voet PW and Heijmen BJ 2012. iCycle: Integrated, multicriterial beam angle, and profile optimization for generation of coplanar and noncoplanar IMRT plans Med Phys 39 951–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun SG, Hu C, Choy H, Komaki RU, Timmerman RD, Schild SE, Bogart JA, Dobelbower MC, Bosch W, Galvin JM, Kavadi VS, Narayan S, Iyengar P, Robinson CG, Wynn RB, Raben A, Augspurger ME, MacRae RM, Paulus R and Bradley JD 2017. Impact of Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy Technique for Locally Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Secondary Analysis of the NRG Oncology RTOG 0617 Randomized Clinical Trial Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 35 56–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Cullip T, Tracton G, Chang S, Marks L, Anscher M and Rosenman J 2003. Beam orientation selection for intensity-modulated radiation therapy based on target equivalent uniform dose maximization Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 55 215–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dink D, Langer MP, Rardin RL, Pekny JF, Reklaitis GV and Saka B 2012. Intensity modulated radiation therapy with field rotation--a time-varying fractionation study Health Care Manag Sci 15 138–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong P, Lee P, Ruan D, Long T, Romeijn E, Low DA, Kupelian P, Abraham J, Yang Y and Sheng K 2013. 4pi noncoplanar stereotactic body radiation therapy for centrally located or larger lung tumors Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 86 407–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaddui T, Chen W, Yu J, Lin L, Simone CB 2nd, Yuan L, Gong YU, Wu QJ, Mohan R, Zhang X, Bluett JB, Gillin M, Moore K, O’Meara E, Presley J, Bradley JD, Liao Z, Galvin J and Xiao Y 2016. Establishing the feasibility of the dosimetric compliance criteria of RTOG 1308: phase III randomized trial comparing overall survival after photon versus proton radiochemotherapy for inoperable stage II-IIIB NSCLC Radiation oncology 11 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoire V, Mackie TR, Co-Chair and Neve WD 2010. ICRU Report No.83: Prescribing, recording, and reporting photon-beam intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). The International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements) [Google Scholar]

- Jia X, Men C, Lou Y and Jiang SB 2011. Beam orientation optimization for intensity modulated radiation therapy using adaptive l(2,1)-minimization Phys Med Biol 56 6205–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Galvin J, Harrison A, Timmerman R, Yu Y and Xiao Y 2012. Dosimetric verification using monte carlo calculations for tissue heterogeneity-corrected conformal treatment plans following RTOG 0813 dosimetric criteria for lung cancer stereotactic body radiotherapy Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 84 508–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Yao J and Yao D 2004. Automatic beam angle selection in IMRT planning using genetic algorithm Phys Med Biol 49 1915–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao ZX, Komaki RR, Thames HD Jr., Liu HH, Tucker SL, Mohan R, Martel MK, Wei X, Yang K, Kim ES, Blumenschein G, Hong WK and Cox JD 2010. Influence of technologic advances on outcomes in patients with unresectable, locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer receiving concomitant chemoradiotherapy Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 76 775–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling DC, Hess CB, Chen AM and Daly ME 2016. Comparison of Toxicity between Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy and 3-Dimensional Conformal Radiotherapy for Locally Advanced Non-small-cell Lung Cancer Clinical lung cancer 17 18–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Dong P and Xing L 2017. A new sparse optimization scheme for simultaneous beam angle and fluence map optimization in radiotherapy planning Physics in Medicine and Biology 62 6428–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HH, Jauregui M, Zhang X, Wang X, Dong L and Mohan R 2006. Beam angle optimization and reduction for intensity-modulated radiation therapy of non-small-cell lung cancers Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 65 561–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J, Hummel SM, Cho PS, Austin-Seymour MM and Phillips MH 2005. Automatic selection of noncoplanar beam directions for three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy The British journal of radiology 78 316–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelms BE, Chan MF, Jarry G v, Lemire M, Lowden J, Hampton C and Feygelman V 2013. Evaluating IMRT and VMAT dose accuracy: Practical examples of failure to detect systematic errors when applying a commonly used metric and action levels Medical Physics 40 111722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popple RA, Brezovich IA and Fiveash JB 2014. Beam geometry selection using sequential beam addition Med Phys 41 051713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potrebko PS, McCurdy BMC, Butler JB and El-Gubtan AS 2008. Improving intensity-modulated radiation therapy using the anatomic beam orientation optimization algorithm Medical Physics 35 2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugachev A, Li JG, Boyer AL, Hancock SL, Le QT, Donaldson SS and Xing L 2001. Role of beam orientation optimization in intensity-modulated radiation therapy Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 50 551–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugachev A and Xing L 2001. Pseudo beam’s-eye-view as applied to beam orientation selection in intensity-modulated radiation therapy Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 51 1361–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreibmann E and Xing L 2004. Feasibility study of beam orientation class-solutions for prostate IMRT Medical Physics 31 2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreibmann E and Xing L 2005. Dose-volume based ranking of incident beam direction and its utility in facilitating IMRT beam placement Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 63 584–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder K, Kim J, Reding A and Fraser C 2016. Development and evaluation of a clinical model for lung cancer patients using stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) within a knowledge-based algorithm for treatment planning JOURNAL OF APPLIED CLINICAL MEDICAL PHYSICS 17 263–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhang X, Dong L, Liu H, Gillin M, Ahamad A, Ang K and Mohan R 2005. Effectiveness of noncoplanar IMRT planning using a parallelized multiresolution beam angle optimization method for paranasal sinus carcinoma Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 63 594–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L, Ge Y, Lee WR, Yin FF, Kirkpatrick JP and Wu QJ 2012. Quantitative analysis of the factors which affect the interpatient organ-at-risk dose sparing variation in IMRT plans Med Phys 39 6868–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L, Wu QJ, Yin F, Li Y, Sheng Y, Kelsey CR and Ge Y 2015. Standardized beam bouquets for lung IMRT planning Physics in Medicine and Biology 60 1831–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarepisheh M, Li R, Ye Y and Xing L 2015. Simultaneous beam sampling and aperture shape optimization for SPORT Med Phys 42 1012–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HH, Gao S, Chen W, Shi L, D’Souza WD and Meyer RR 2013. A surrogate-based metaheuristic global search method for beam angle selection in radiation treatment planning Phys Med Biol 58 1933–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Li X, Quan EM, Pan X and Li Y 2011. A methodology for automatic intensity-modulated radiation treatment planning for lung cancer Physics in Medicine and Biology 56 3873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.