Abstract

Fibroblast activation protein (FAP) is a proline-selective serine protease. It is hardly expressed in healthy adult tissue but upregulated in tissue remodeling sites associated with several diseases including epithelial cancer types, atherosclerosis, arthritis and fibrosis. Ongoing research aims at clinical implementation of FAP as a biomarker for these diseases. Several immunochemical methods that quantify FAP expression have been reported. An alternative/complementary approach focuses on quantification of FAP’s enzymatic activity. Developing an activity-based assay for FAP has nonetheless proven challenging because of selectivity issues with respect to prolyl oligopeptidase (PREP). Here, we present substrate-type FAP probes that are structurally derived from a FAP-inhibitor (UAMC1110) that we published earlier. Both cleavage efficiency and FAP-selectivity of the best compounds in the series equal or surpass the most advanced peptide-based FAP substrates reported to date. Finally, proof-of-concept is provided that 4-aminonaphthol containing probes can spatially localize FAP activity in biological samples.

Keywords: Fibroblast activation protein, FAP, seprase, biomarker, UAMC1110, selective substrate, PREP

Fibroblast activation protein (FAP, FAPα) is a transmembrane serine protease that belongs to the dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP) family. Next to postproline exopeptidase activity, FAP possesses endopeptidase (gelatinase) activity, with a clear preference for the Gly-Pro sequence.1−3 FAP also exhibits a unique expression pattern. Typically, FAP expression is low to undetectable in most healthy adult tissues, with endometrial cells and wound healing sites being well-known exceptions. However, FAP is highly upregulated in lesions associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), hepatic fibrosis, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), atherosclerosis, and in stromal tissue of a multitude of tumor types, including nearly all epithelial carcinomas.4−8 Furthermore, FAP enzymatic activity and/or its expression levels have been reported to be correlated with patient outcome, disease severity, and/or susceptibility to treatment in some of the aforementioned pathologies.4−9 Interestingly, most of these reports have so far focused on quantification of FAP expression, generally relying on classical immunochemical techniques (e.g., ELISA). A number of FAP-specific antibodies are available to support such studies, although some of the commercial antibodies have been reported to lack specificity.6−8 Alternatively and/or complementary to measuring the enzyme’s expression levels, others are investigating whether FAP’s enzymatic activity status could be a better biomarker of disease. The latter could indeed be the case, based on earlier reports that functionally link FAP activity to disease, e.g., in cancer and fibrosis.4,5,8−10 Experimental validation nonetheless is required, and fundamental questions regarding the biological regulation of FAP’s activity status in vivo remain to be addressed.11 While awaiting the settlement of these issues, several activity-based probes (ABPs) have been reported that are amenable to quantification of FAP activity in biological matrixes. These comprise both substrate-type compounds and active site ligands equipped with a suitable reporter system. A well-known limitation of several of these probes is their lack of selectivity with respect to peptidases related to FAP, specifically toward the endopeptidase prolyl oligopeptidase (PREP).12 Likewise, the synthetic substrates commonly used to measure dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP) activity are also processed by FAP.13 Selected, relevant examples of ABPs for FAP are shown in Figure 1. Compound 1 (ANPFAP) is an activatable near-infrared (NIR) fluorescent probe, developed by Li and co-workers. This quenched probe was originally reported to be selective for FAP but processing by PREP was later on demonstrated by Bainbridge and co-workers.12,14 In response, Bainbridge reported a series of quenched fluorescent substrates based on the endogenous FAP-substrate FGF21.12 The most promising compound in that paper, 2 (also referred to as aP, Figure 1), was not processed by PREP under the assay conditions and was convincingly demonstrated, i.e., to be applicable for reliable quantification of FAP-activity in plasma. Other groups have devoted attention to discovery of small-molecule-based ABPs for FAP. In 2018, Haberkorn and co-workers published a series of PET probes for tumor imaging, represented by compound 3 in Figure 1.15−17 These compounds, for which human applicability was demonstrated, were structurally derived from UAMC1110, a FAP-selective inhibitor reported by our group (substructure highlighted in probe 3, also shown as compound 5 in Figure 2).18 A boronate-based inhibitor related to UAMC1110, published by Bachovchin, has also been used as the structural basis for the fluorogenic substrate ARI-3144 (compound 4, Figure 1).19,20 This compound was claimed by the authors to be a specific substrate for FAP and used for quantification of FAP-activity in serum and tissue samples. However, no processing parameters (kcat, Km) for FAP, PREP, or any of the related dipeptidyl-peptidases were reported, and no information was provided on whether other analogues had been synthesized and evaluated. Moreover, in our own hands, ARI-3144 did not behave as a specific substrate of FAP (vide infra, Table 1).

Figure 1.

Relevant published probes for detection and quantification of FAP activity.

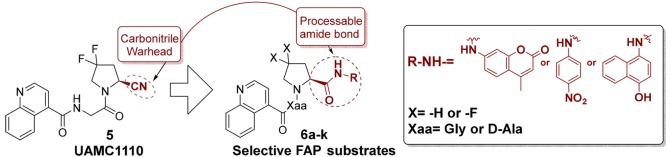

Figure 2.

Overview of the FAP ABPs prepared in this study.

Table 1. Processing Data for Target Compounds 6 by FAP and PREPa,b.

Values are represented as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3; for 6h and 6i: n = 2).

None of the compounds in Table 1 displayed substrate inhibition (si) toward FAP, except compound 6a (Ksi = 29 ± 6 μM).

SI = selectivity index, defined as kcat/Km (FAP)/kcat/Km (PREP).

NP = not processed; no cleavage of the substrate was observed at the highest concentration that was evaluated.

ND = not determined; no active site saturation could be reached in the concentration range that was used.

NA = not applicable.

In response to the latter, we decided to explore the chemical space around 4 to obtain probes with a higher FAP/PREP selectivity. Noteworthy, we were interested in direct analogues of our own FAP-inhibitor UAMC1110 (compound 5, Figure 2), which is one of the most potent and selective FAP-inhibitors published to date.18,21 Replacing its carbonitrile warhead function by an enzyme processable amide group was expected to be instrumental for obtaining selective and efficiently processed substrates: for carbonitrile-based compounds (capable of forming transition-state mimicking complexes after binding to FAP or the related proteases), transition state theory predicts a strong correlation between Ki values and the −log(kcat/Km) parameter of derived substrates.22 This implies that, at least in theory, the low nanomolar FAP potency of UAMC1110 should translate in efficient processing of the corresponding substrates by FAP. Likewise, the low affinity of UAMC1110 for PREP and the related dipeptidyl-peptidases would translate in poor substrate properties for the latter enzymes. Three reporter groups were selected for target compounds 6: 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC), para-nitroaniline (pNA), and 4-aminonaphthol (4-AN). The first two are well-known constituents of fluorogenic and chromogenic protease substrates. The third reporter (4-AN) in its free, nonacylated form, is capable of reducing tetrazolium-type precursors to formazan dyes. When a combination of a 4-AN containing substrate and a tetrazolium dye precursor is applied to a biological sample that contains spatially defined loci of enzymatic substrate processing, liberated 4-AN produces formazan blue in situ. The insoluble formazan blue precipitates, allowing spatial localization of enzymatic activity. Furthermore, the intensity of the blue precipitates can be used as a (semi-) quantitative measure of activity. In the more recent literature, substrates of this type have been reported for dipeptidyl peptidases and PREP, and their applicability in (patho-)histology was demonstrated.23,24 Two additional structural features were investigated in the substrate series of generic structure 6: (1) difluoro-substitution at the P1 pyrrolidine residue and (2) the P2 amino acid residue (“Xaa” in Figure 2). While difluorination of the pyrrolidine ring in 6 appreciably increases FAP-affinity, it also increases lipophilicity and decreases solubility. Because enzyme substrates are typically used at higher concentrations than inhibitors (micromolar vs nanomolar ranges), we expected the lower aqueous solubility of difluorinated substrates to be a potentially limiting factor. Therefore, analogues with a nonfluorinated P1-pyrrolidine were also included in this study.

At the P2 position, both a Gly and a d-Ala residue were selected. The choice for d-Ala was motivated by the presence of this residue in 4 and earlier literature claims that d-Ala in this position can be used to increase FAP/PREP selectivity.19,25

Results and Discussion

The general synthetic pathway toward target compounds 6 is shown in Scheme 1. Commercially available Boc-l-proline 7 or Boc-4,4-difluoro-l-proline 8 was coupled with either AMC, pNA, or 4-AN, delivering compounds 9–14. These were subsequently deprotected to the analogous, deprotected P1-building blocks 15–20. The latter were then coupled to Boc-protected d-alanine or glycine, yielding the protected [P2–P1] constructs 21–32. Acidolytic deprotection of these intermediates resulted in 33–44, from which final compounds 6a–k and 4 were synthesized by acylating the free amine group with quinoline-4-carboxylic acid.

Scheme 1. Synthetic Strategy for Target Compounds 6.

Reagents and conditions: (a) AMC or pNA, 1-chloro-N,N,2-trimethyl-1-propenylamine TEA, DCM:THF (1:1), rt; (b) 4-AN, isobutyl chloroformate, TEA, DCM, 0 °C to rt; (c) HCl, DCM, rt; (d) TFA, DCM, rt; (e) Boc-Xaa, T3P, DIPEA, DCM, rt; (f) quinoline-4-carboxylic acid, T3P, DIPEA, DCM.

For all final compounds, substrate properties were determined by measuring initial velocities of product formation catalyzed by FAP, PREP, and DPP4, 8, and 9. At least six concentrations per substrate were evaluated, and the highest concentration evaluated for each substrate was either 250 μM or the highest concentration of full solubility in assay media. Km and kcat parameters were determined when substrate solubility was sufficient to achieve enzyme saturation. Otherwise, a first order rate constant of substrate processing (kcat/Km) was determined from the linear part of the curve. Depending on the reporter group in the substrates (AMC, pNA, or 4-AN), different quantification methods were used. AMC-concentrations were measured using fluorometry and pNA concentrations via absorption spectrophotometry. For assessment of 4-AN-release, a photometric approach could not be elaborated because of overlaps between the absorbance and fluorescence spectra of 4-AN and other assay components. Therefore, a multiple reaction monitoring (MRM)-based LC–MS method was developed.

Biochemical evaluation data for 6a–k and 4 are shown in Table 1. At the highest concentration evaluated (vide supra), none of the compounds were observably cleaved by DPPs 4, 8, and 9. This is not surprising since DPPs are known to require a positively charged P2-amino terminus for molecular recognition of their substrates. Due to this lack of processing, the assay results for the DPPs are not shown in Table 1, and only data for FAP and PREP are given. First, both for FAP and PREP, a clear difference in processing efficiency (kcat/Km) can be observed between substrates with different reporter groups: AMC-based molecules (6a–c, 4) are generally more efficiently cleaved than pNA-containing molecules (6d–g), and these, in turn, are cleaved more efficiently than 4-AN derivatives (6h–k). Quantitative analysis of the kcat/Km reduction between AMC- (6a–c, 4) and pNA (6d–6g)-based substrates, reveals that the fold decrease is different for each substrate and enzyme. Furthermore, the underlying cause for the lower cleavage efficiency seems to be inconsistent: either a decrease of the kcat-parameter, an increase of the Km-parameter, or both can be seen for the individual pNA-derived molecules compared to analogous AMC-based substrates. All these findings indicate that most likely an ensemble of kinetic (e.g., leaving group properties of the amines) and thermodynamic factors (e.g., substrate accommodation in the active site) govern the decrease. Finally, quantitative comparison with 4-AN substrates (6h–k) cannot be done reliably, given the lack of processing that is observed for several of the latter.

Furthermore, difluorination at the P1-proline residue appears not to have major impact on FAP-processing efficiency. This can be illustrated by comparing FAP-processing data for the corresponding pairs 6a/6b, 4/6c, and 6d/6e. Very remarkably nonetheless, while difluorination does not strongly affect the overall cleavage efficiency (kcat/Km), it does seem to induce a decrease of comparable proportionality on both the kcat and Km parameters of the corresponding substrates. The lower Km value of the difluorinated molecules (which implies that active site saturation is reached at lower substrate concentration) can be rationalized by taking into account the higher lipophilicity and/or better accommodation of these compounds. The decreased kcat parameter, however, also indicates that once bound to FAP difluorinated substrates are less readily processed by the enzyme. In contrast to FAP processing, a clearly negative effect of substrate difluorination on PREP cleavage efficiency can be observed, as exemplified by the corresponding kcat/Km data for the same substrate pairs. A detailed, quantitative comparison nonetheless is not possible since most difluorinated substrates are so poorly processed by PREP that only for 6b the individual kcat and Km values could be determined.

Finally, the presence of d-Ala in P2 also has a notably negative effect on the catalytic efficiency for both FAP and PREP when compared to Gly-containing substrates. This is illustrated by the analogous pairs 6a/4, 6b/6c and 6d/6f. Quantitative comparison reveals that for FAP the decrease in none of the cases exceeds 1 order of magnitude. However, the effect appears to be much more pronounced for PREP: out of all d-Ala-containing substrates, only 4 was processed by PREP.

For selecting the most promising FAP substrates in this series of compounds, both the FAP/PREP selectivity index (SI) and the absolute value of FAP cleavage efficiency should be taken into account. For the fluorogenic and chromogenic subseries, the direct AMC- and pNA-analogues of UAMC-1110 (6b and 6e) clearly possess FAP cleavage efficiencies that are unprecedented in the FAP substrate literature. In addition, they have FAP/PREP selectivity indices (32 and 26, respectively) that are significantly higher than that of ref (4) (ARI-3144). As mentioned earlier, 4 was reported earlier as a FAP-specific molecule, although no substrate characterization data (e.g., kcat/Km values for FAP and PREP processing) were ever published. In addition, also within the AMC- and pNA-based subseries, 6c, 6f, and 6g are not measurably processed by PREP. Although the FAP cleavage efficiencies of these molecules are also lower, their kcat/Km values are still considerably higher than the published value for quenched peptide substrate 2/aP (kcat/Km= 0.00383 × 106 s–1 M–1).12,26 Comparable considerations can be made for the 4-AN-based histology substrates 6h and 6i. The latter are not cleaved by PREP and possess cleavage efficiencies that are higher than what has been reported for both the peptide-based 2 and ref (4). Finally, the commercially available fluorogenic substrate Z-Gly-Pro-AMC (45) was included in this study as an additional reference (Table 1). This molecule has been used, e.g., for quantification of FAP and PREP activity in plasma.27 As clearly observable, both FAP cleavage efficiency and its FAP/PREP selectivity are less favorable than the quinolinoyl-containing analogues in this study. These data also underscore the particular importance of the quinolinoyl function.

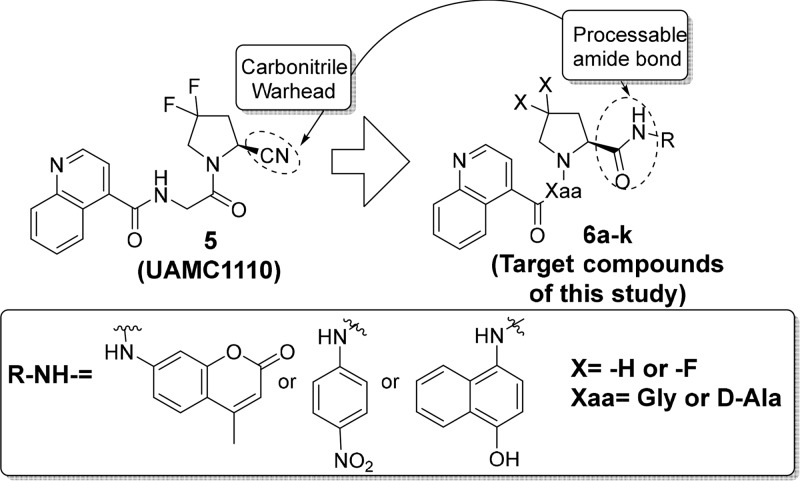

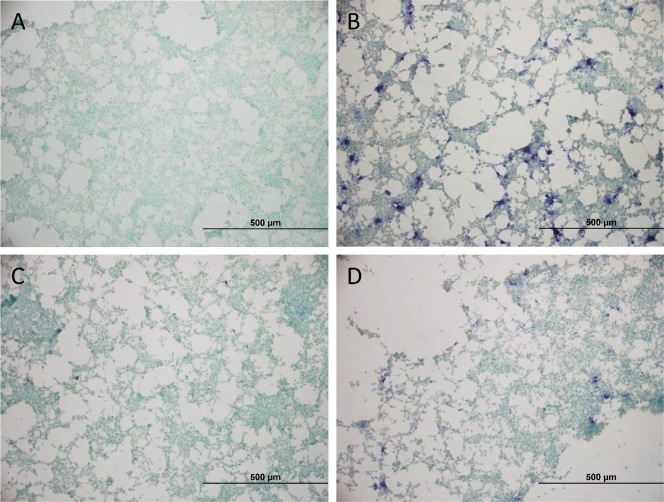

As a final part of this study, we wanted to deliver proof-of-concept that the most promising 4-AN-based probe 6h indeed can be used for localized staining of FAP-activity in biological samples. Cultured HEK293T cells were considered an appropriate model system. First, the cells were either transfected with empty pDEST40-vector (Figure 3A) as a negative control or with pDEST40-hFAP-vector (Figure 3B–D) for 48 h. Constitutional expression of FAP and PREP in empty-vector transfected cells was found to be minimal (Supporting Information, determined via classical activity measurement on cell lysate).27 Likewise, selective overexpression of FAP was confirmed in pDEST40-hFAP-transfected cells. Five minutes before adding substrate 6h to A–D, the cells were first pretreated with either DMSO (panels A and B), with FAP-inhibitor UAMC1110 (panel C) or with selective PREP inhibitor KYP-2047 (panel D).28 Gratifyingly, all these cellular experiments were found to confirm the in vitro FAP-processing selectivity determined earlier. The nonhomogenous and clearly localized fashion in which blue stains appeared is assigned to subpopulations of the cells in which transfection had been successful. Cells treated with an empty transfection vector or with UAMC-1110 do not show blue precipitates. Similar results were obtained using the 4-AN based probe 6i (Supporting Information, Figure S2). Altogether, we consider the results of these proof-of-concept experiments promising enough to pursue future effort in real histochemistry settings.

Figure 3.

FAP-activity staining in HEK293T cells with 6h. (A) Cells transfected with empty pDEST40-vector and treated with 6h. (B–D) Cells transfected with pDEST40-hFAP-vector, treated with 6h (B), with 6h + FAP-inhibitor 5/UAMC-1110 (C), or with 6h and PREP-inhibitor KYP-2047 (D).

Conclusion

Given the need for sensitive and reliable activity-based probes for FAP to support biomarker research, a series of novel small molecule substrates for FAP was delivered. These compounds were inspired by a FAP inhibitor that we published earlier (5/UAMC1110) and also by a small molecule substrate reported by Bachovchin (4/ARI-3144). Among the fluorogenic and chromogenic substrates that we prepared, 6b and 6e were found to combine unprecedented FAP cleavage efficiencies and FAP/PREP selectivity indices that are significantly better than those of ref (4). In addition, the fluorogenic and chromogenic subset was found to contain a number of probes (6c, 6f, and 6g) that are not cleaved by PREP under the assay conditions but still are characterized by significantly higher FAP-cleavage efficiencies than the value reported for 2/aP. The latter is the most promising peptide-based FAP substrate reported to date. Similar considerations can be made for the 4-AN containing subgroup of compounds. In addition, this is the first time that spatial localization of FAP activity is demonstrated with a 4-AN based substrate. Taken together, these data demonstrate that FAP inhibitors like 5/UAMC1110, can serve as a promising starting point for construction of substrates. Noteworthy, expansion to other fluorogenic, colorigenic, and even bioluminogenic reporter types is possible.

Acknowledgments

An De Decker, Dries van Rompaey, and Anke Peeraer are grateful to the Fund for Scientific Research-Vlaanderen (FWO-Vlaanderen) for a Ph.D. scholarship.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- ABP

activity-based probe;

- DCM

dichloromethane;

- DIPEA

di-isopropylethylamine;

- DPP

dipeptidyl peptidase;

- FAP

fibroblast activation protein;

- MRM

multiple reaction monitoring;

- PREP

prolyl oligopeptidase;

- SI

selectivity index;

- TEA

triethylamine;

- T3P

1-propanephosphonic anhydride

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00191.

Synthetic protocols, spectral characterization and analysis data for the reported compounds, experimental details for all biological experiments, and supplementary cellular evaluation data (PDF)

Author Contributions

⊥ These authors contributed equally.

This work received support from a GOA-BOF 2015 grant of the University of Antwerp (30729) and a research grant from the Science Foundation Flanders (FWO-Vlaanderen, grant number G038515N). Ruth Geiss-Friedlander is grateful to the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for financial support (grant number 2234/1-3).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Park J. E.; Lenter M. C.; Zimmermann R. N.; Garin-Chesa P.; Old L. J.; Rettig W. J. Fibroblast Activation Protein, a Dual Specificity Serine Protease Expressed in Reactive Human Tumor Stromal Fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274 (51), 36505–36512. 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamson E. J.; Keane F. M.; Tholen S.; Schilling O.; Gorrell M. D. Understanding Fibroblast Activation Protein (FAP): Substrates, Activities, Expression and Targeting for Cancer Therapy. Proteomics: Clin. Appl. 2014, 8 (5–6), 454–463. 10.1002/prca.201300095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edosada C. Y.; Quan C.; Tran T.; Pham V.; Wiesmann C.; Fairbrother W.; Wolf B. B. Peptide Substrate Profiling Defines Fibroblast Activation Protein as an Endopeptidase of Strict Gly 2 -Pro 1 -Cleaving Specificity. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580 (6), 1581–1586. 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan M.-H.; Zhu Q.; Li H.-H.; Ra H.-J.; Majumdar S.; Gulick D. L.; Jerome J. A.; Madsen D. H.; Christofidou-Solomidou M.; Speicher D. W.; Bachovchin W. W.; Feghali-Bostwick C.; Pure E. Fibroblast Activation Protein (FAP) Accelerates Collagen Degradation and Clearance from Lungs in Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291 (15), 8070–8089. 10.1074/jbc.M115.701433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lay A. J.; Zhang H. E.; McCaughan G. W.; Gorrell M. D. Fibroblast Activation Protein in Liver Fibrosis. Front. Biosci., Landmark Ed. 2019, 24, 1–17. 10.2741/4706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Geest T.; Roeleveld D. M.; Walgreen B.; Helsen M. M.; Nayak T. K.; Klein C.; Hegen M.; Storm G.; Metselaar J. M.; van den Berg W. B.; van der Kraan P. M.; Laverman P.; Boerman O. C.; Koenders M. I. Imaging Fibroblast Activation Protein to Monitor Therapeutic Effects of Neutralizing Interleukin-22 in Collagen-Induced Arthritis. Rheumatology 2018, 57 (4), 737–747. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brokopp C. E.; Schoenauer R.; Richards P.; Bauer S.; Lohmann C.; Emmert M. Y.; Weber B.; Winnik S.; Aikawa E.; Graves K.; Genoni M.; Vocht P.; Lüscher T. F.; Renner C.; Hoerstrup S. P.; Matter C. M. Fibroblast Activation Protein Is Induced by Inflammation and Degrades Type I Collagen in Thin-Cap Fibroatheromata. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32 (21), 2713–2722. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puré E.; Blomberg R. Pro-Tumorigenic Roles of Fibroblast Activation Protein in Cancer: Back to the Basics. Oncogene 2018, 37 (32), 4343–4357. 10.1038/s41388-018-0275-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazbeck R.; Jaenisch S. E.; Abbott C. A. Potential Disease Biomarkers: Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 and Fibroblast Activation Protein. Protoplasma 2018, 255 (1), 375–386. 10.1007/s00709-017-1129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J. D.; Valianou M.; Canutescu A. A.; Jaffe E. K.; Lee H.-O.; Wang H.; Lai J. H.; Bachovchin W. W.; Weiner L. M. Abrogation of Fibroblast Activation Protein Enzymatic Activity Attenuates Tumor Growth. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2005, 4 (3), 351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.-O.; Mullins S. R.; Franco-Barraza J.; Valianou M.; Cukierman E.; Cheng J. D. FAP-Overexpressing Fibroblasts Produce an Extracellular Matrix That Enhances Invasive Velocity and Directionality of Pancreatic Cancer Cells. BMC Cancer 2011, 11 (1), 245. 10.1186/1471-2407-11-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge T. W.; Dunshee D. R.; Kljavin N. M.; Skelton N. J.; Sonoda J.; Ernst J. A. Selective Homogeneous Assay for Circulating Endopeptidase Fibroblast Activation Protein (FAP). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7 (1), 12524. 10.1038/s41598-017-12900-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen K.; Heirbaut L.; Cheng J. D.; Joossens J.; Ryabtsova O.; Cos P.; Maes L.; Lambeir A.-M.; De Meester I.; Augustyns K.; Van der Veken P. Selective Inhibitors of Fibroblast Activation Protein (FAP) with a (4-Quinolinoyl)-Glycyl-2-Cyanopyrrolidine Scaffold. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4 (5), 491–496. 10.1021/ml300410d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Chen K.; Liu H.; Cheng K.; Yang M.; Zhang J.; Cheng J. D.; Zhang Y.; Cheng Z. Activatable Near-Infrared Fluorescent Probe for In Vivo Imaging of Fibroblast Activation Protein-Alpha. Bioconjugate Chem. 2012, 23 (8), 1704–1711. 10.1021/bc300278r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loktev A.; Lindner T.; Mier W.; Debus J.; Altmann A.; Jäger D.; Giesel F.; Kratochwil C.; Barthe P.; Roumestand C.; Haberkorn U. A Tumor-Imaging Method Targeting Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. J. Nucl. Med. 2018, 59 (9), 1423–1429. 10.2967/jnumed.118.210435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner T.; Loktev A.; Altmann A.; Giesel F.; Kratochwil C.; Debus J.; Jäger D.; Mier W.; Haberkorn U. Development of Quinoline-Based Theranostic Ligands for the Targeting of Fibroblast Activation Protein. J. Nucl. Med. 2018, 59 (9), 1415–1422. 10.2967/jnumed.118.210443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesel F.; Kratochwil C.; Lindner T.; Marschalek M.; Loktev A.; Lehnert W.; Debus J.; Jäger D.; Flechsig P.; Altmann A.; Mier W.; Haberkorn U. FAPI-PET/CT: Biodistribution and Preliminary Dosimetry Estimate of Two DOTA-Containing FAP-Targeting Agents in Patients with Various Cancers. J. Nucl. Med. 2019, 60, 386. 10.2967/jnumed.118.215913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen K.; Heirbaut L.; Verkerk R.; Cheng J. D.; Joossens J.; Cos P.; Maes L.; Lambeir A.-M.; De Meester I.; Augustyns K.; Van der Veken P. Extended Structure–Activity Relationship and Pharmacokinetic Investigation of (4-Quinolinoyl)Glycyl-2-Cyanopyrrolidine Inhibitors of Fibroblast Activation Protein (FAP). J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57 (7), 3053–3074. 10.1021/jm500031w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poplawski S. E.; Lai J. H.; Li Y.; Jin Z.; Liu Y.; Wu W.; Wu Y.; Zhou Y.; Sudmeier J. L.; Sanford D. G.; Bachovchin W. W. Identification of Selective and Potent Inhibitors of Fibroblast Activation Protein and Prolyl Oligopeptidase. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56 (9), 3467–3477. 10.1021/jm400351a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane F. M.; Yao T.-W.; Seelk S.; Gall M. G.; Chowdhury S.; Poplawski S. E.; Lai J. H.; Li Y.; Wu W.; Farrell P.; Vieira de Ribeiro A. J.; Osborne B.; Yu D. M.; Seth D.; Rahman K.; Haber P.; Topaloglu A. K.; Wang C.; Thomson S.; Hennessy A.; Prins J.; Twigg S. M.; McLennan S. V.; McCaughan G. W.; Bachovchin W. W.; Gorrell M. D. Quantitation of Fibroblast Activation Protein (FAP)-Specific Protease Activity in Mouse, Baboon and Human Fluids and Organs. FEBS Open Bio 2014, 4 (1), 43–54. 10.1016/j.fob.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvořáková P.; Bušek P.; Knedlík T.; Schimer J.; Etrych T.; Kostka L.; Stollinová Šromová L.; Šubr V.; Šácha P.; Šedo A.; Konvalinka J. Inhibitor-Decorated Polymer Conjugates Targeting Fibroblast Activation Protein. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60 (20), 8385–8393. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladysz R.; Lambeir A.-M.; Joossens J.; Augustyns K.; Van der Veken P. Substrate Activity Screening (SAS) and Related Approaches in Medicinal Chemistry. ChemMedChem 2016, 11 (5), 467–476. 10.1002/cmdc.201500569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schade J.; Stephan M.; Schmiedl A.; Wagner L.; Niestroj A. J.; Demuth H.-U.; Frerker N.; Klemann C.; Raber K. A.; Pabst R.; Von Hörsten S. Regulation of Expression and Function of Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 (DP4), DP8/9, and DP10 in Allergic Responses of the Lung in Rats. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2008, 56 (2), 147–155. 10.1369/jhc.7A7319.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimaviciusa L.; Jain R. K.; Jaako K.; Van Elzen R.; Gerard M.; van Der Veken P.; Lambeir A.-M.; Zharkovsky A. In Situ Prolyl Oligopeptidase Activity Assay in Neural Cell Cultures. J. Neurosci. Methods 2012, 204 (1), 104–110. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edosada C. Y.; Quan C.; Wiesmann C.; Tran T.; Sutherlin D.; Reynolds M.; Elliott J. M.; Raab H.; Fairbrother W.; Wolf B. B. Selective Inhibition of Fibroblast Activation Protein Protease Based on Dipeptide Substrate Specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281 (11), 7437–7444. 10.1074/jbc.M511112200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blöcher R.; Wagner K. M.; Gopireddy R. R.; Harris T. R.; Wu H.; Barnych B.; Hwang S. H.; Xiang Y. K.; Proschak E.; Morisseau C.; Hammock B. D. Orally Available Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase/Phosphodiesterase 4 Dual Inhibitor Treats Inflammatory Pain. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61 (8), 3541–3550. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracke A.; Van Elzen R.; Van Der Veken P.; Augustyns K.; De Meester I.; Lambeir A.-M. The Development and Validation of a Combined Kinetic Fluorometric Activity Assay for Fibroblast Activation Protein Alpha and Prolyl Oligopeptidase in Plasma. Clin. Chim. Acta 2019, 495, 154–160. 10.1016/j.cca.2019.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Veken P.; Fülöp V.; Rea D.; Gerard M.; Van Elzen R.; Joossens J.; Cheng J. D.; Baekelandt V.; De Meester I.; Lambeir A.-M.; Augustyns K. P2-Substituted N -Acylprolylpyrrolidine Inhibitors of Prolyl Oligopeptidase: Biochemical Evaluation, Binding Mode Determination, and Assessment in a Cellular Model of Synucleinopathy. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55 (22), 9856–9867. 10.1021/jm301060g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.