Abstract

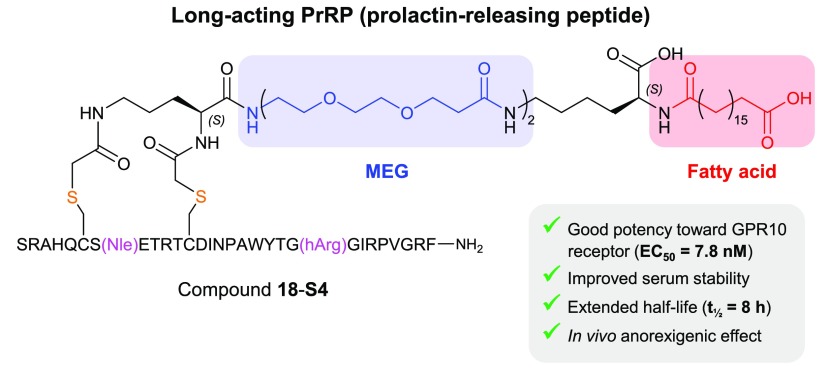

Anorexigenic peptides offer promise as potential therapies targeting the escalating global obesity epidemic. Prolactin-releasing peptide (PrRP), a novel member of the RFamide family secreted by the hypothalamus, shows therapeutic potential by decreasing food intake and body weight in rodent models via GPR10 activation. Here we describe the design of a long-acting PrRP using our recently developed novel multiple ethylene glycol-fatty acid (MEG-FA) stapling platform. By incorporating serum albumin binding fatty acids onto a covalent side chain staple, we have generated a series of MEG-FA stapled PrRP analogs with enhanced serum stability and in vivo half-life. Our lead compound 18-S4 exhibits good in vitro potency and selectivity against GPR10, improved serum stability, and extended in vivo half-life (7.8 h) in mouse. Furthermore, 18-S4 demonstrates a potent body weight reduction effect in a diet-induced obesity (DIO) mouse model, representing a promising long-acting PrRP analog for further evaluation in the chronic obesity setting.

Keywords: Prolactin-releasing peptide, peptide stapling, lipid−drug conjugate, GPCR, long-acting, prolonged half-life, serum protein binding, diabetes, obesity

Prolactin-releasing peptide (PrRP) was initially discovered from hypothalamus as a novel peptide that stimulates prolactin secretion in anterior pituitary cells via activation of the orphan G-protein coupled receptor human gustatory receptor 3 (Gr3), and its rat ortholog unknown hypothalamic receptor-1 (UHR-1).1 However, later reports showed that PrRP does not stimulate the secretion of prolactin or other pituitary hormones but may act as a neuromodulator and play a key role in the regulation of energy balance via activation of the prolactin-releasing peptide receptor, also known as G-protein coupled receptor 10 (GPR10, identical to hGr3).2−5 PrRP reduces body weight and food intake, and modifies body temperature when administered centrally, suggesting a role in energy homeostasis.2 The anorexigenic effect of PrRP is mediated by corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptors,3 and it also interacts with leptin to reduce food intake and body weight.6 PrRP-deficient mice show late onset obesity and adiposity suggesting that PrRP relays the satiety signal within the brain. A disturbance of PrRP receptor signaling can result in obesity and metabolic disorders.7 Thus, PrRP may offer potential as a therapeutic for diabetes and obesity, via harnessing of its anorexigenic properties for food intake and body weight reduction.

However, central administration of PrRP results in significantly increased cardiac contractility, heart rate, and blood pressure.8−10 PrRP belongs to the RFamide peptide family, and in addition to activating GPR10 it also exhibits high affinity toward NPFF2R (neuropeptide FF receptor 2 or GPR74).11 While NPFF2R signaling exerts an additional anorexigenic effect that may augment that mediated by GPR10,11,12 NPFF2R has been linked to elevated arterial blood pressure and may be responsible for PrRP-induced cardiovascular effects. PrRP causes an increase in arterial blood pressure and heart rate, which can be abolished by coadministration of RF9, a specific NPFF2R antagonist, but not neuropeptide Y, a putative GPR10 antagonist.13,14 Direct conjugation of palmitic acid to the N-terminus of PrRP via a Lys side chain at position 11 leads to significant extension of half-life and in vivo anorexigenic effect, with reduction of food intake, body weight, and glucose intolerance in rat and mouse models of obesity.15−20 Despite the benefit of exerting a central nervous system effect following peripheral administration, palmitoylated PrRP analogs seem to demonstrate increased activity toward NPFF2R. Thus, there is a need to develop GPR10-selective PrRP analogs that retain their anorectic and antidiabetic effects, while diminishing their activity toward NPFF2R agonism and its associated cardiovascular risk.21,22 Herein, we have applied a recently developed multiple ethylene glycol-fatty acid (MEG-FA) stapling technology to produce a selective and long-acting PrRP analog, 18-S4. Peptide 18-S4 exhibits good in vitro potency toward GPR10, reduced activation of NPFF2R, improved serum stability and in vivo half-life, and potent anorexigenic effect in diet-induced obese mice.

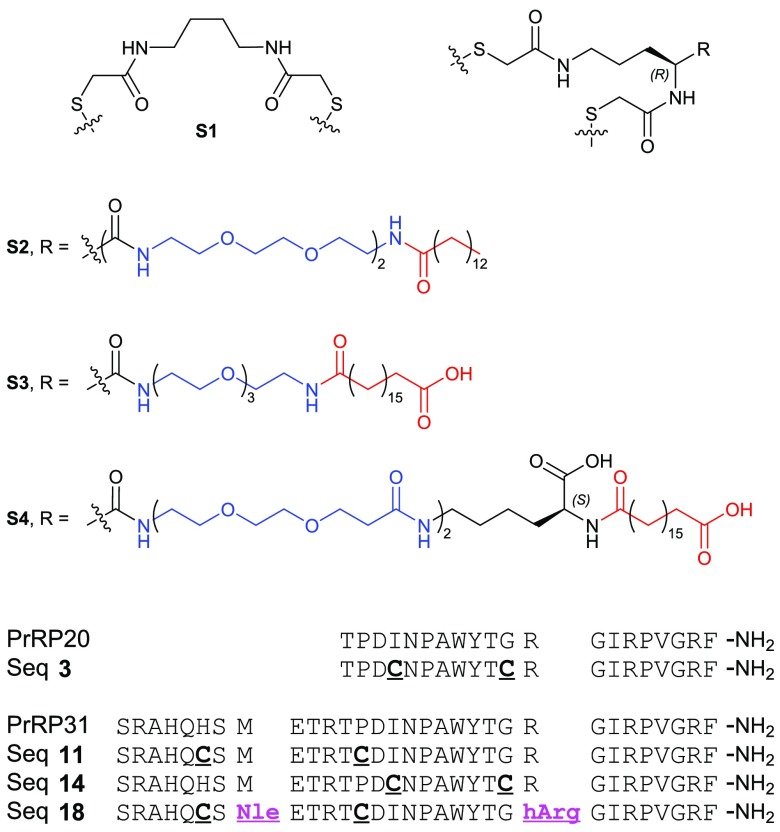

Endogenous PrRP exists in two isoforms: PrRP31 and N-terminally truncated PrRP20 (Figure 1). There are no crystal structures of PrRP peptides available, but NMR studies of PrRP20 reveal that the peptide exists in an equilibrium between α-helical and 310-helical forms and that the α-helical structure is critical for receptor activation.23 The 310 helix conformer forms hydrogen bonds between residues i and i + 3, in contrast to the α helix, which forms hydrogen bonds between residues i and i + 4. Further deletion of the N-terminus of PrRP20 reduces the affinity toward GPR10. PrRP derivatives truncated by more than four amino acids show activity at both NPFF2R and GPR10.24 GPR10 mutagenesis has revealed a conserved aspartate residue (Asp59) from the upper transmembrane helix 6, which directly interacts with Arg19 from PrRP20.25 Arg19 has been shown to be critical for GPR10 activation and may also form an important interaction with Glu26 located in transmembrane helix 5. Taking this into account, we scanned for tolerated dicysteine mutations within PrRP20 and PrRP31 onto which a staple could be incorporated, sparing the three C-terminal residues.

Figure 1.

Key sequences (PrRP20, PrRP31, and dicysteine mutants) and structures of MEG-FA staples S1, S2, S3, and S4.

Side chain stapling of a helical peptide can increase its proteolytic stability and helical conformation.26−33 Previously we showed that incorporation of a dicysteine motif at i and i + 7 positions could be effectively cross-linked with aliphatic spacers, resulting in a stabilized helical conformation.34−36 We carried out a screen of the PrRP20 sequence to find an optimum dicysteine mutant that retained or enhanced GPR10 activation, using a β-arrestin recruitment assay in a GPR10-overexpressing CHO-K1 cell line from DiscoverX (Table 1). Dicysteine incorporation at positions 3–10 (sequence 2), 4–11 (3), and 6–13 (5) was tolerated, while mutation at positions 8–15 (7), 9–16 (8), or 10–17 (9) drastically reduces the potency against GPR10. When peptides with sequence 2, 3, and 5 were conjugated with staple S1 (lacking a fatty acid moiety, Figure 1), the activity was retained or slightly improved (Table 1).

Table 1. Potency of PrRP20 and PrRP31 Derivatives at the GPR10 Receptor.

| GPR10

EC50 (nM)b |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seqa | di-Cys | no staple | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 |

| PrRP20 | - | 13 ± 1 | - | - | - | - |

| 1 | 2–9 | 33 ± 3 | 12 ± 1 | 33 ± 4 | 230 ± 30 | 620 ± 60 |

| 2 | 3–10 | 16 ± 2 | 21 ± 2 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| 3 | 4–11 | 10 ± 1 | 7.3 ± 0.6 | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 77 ± 9 | 81 ± 7 |

| 4 | 5–12 | 44 ± 6 | 13 ± 1 | 25 ± 3 | 610 ± 80 | 840 |

| 5 | 6–13 | 18 ± 2 | 15 ± 2 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| 6 | 7–14 | 33 ± 4 | 10 ± 1 | 5.2 ± 0.6 | >1000 | >1000 |

| 7 | 8–15 | 6800 | 720 ± 80 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| 8 | 9–16 | 120 ± 10 | 160 ± 20 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| 9 | 10–17 | 1600 | >10000 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| PrRP31 | - | 12 ± 3 | - | - | - | - |

| 10 | 1–8 | 16 ± 2 | 24 ± 3 | 17 ± 2 | 230 ± 20 | 330 ± 30 |

| 11 | 6–13 | 29 ± 5 | 20 ± 3 | 13 ± 2 | 80 ± 10 | 260 ± 20 |

| 12 | 9–16 | 41 ± 4 | 85 ± 10 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| 13 | 13–20 | 18 ± 2 | 40 ± 6 | 17 ± 2 | 630 ± 80 | 1500 |

| 14 | 15–22 | 17 ± 2 | 10 ± 1 | 6.1 ± 0.4 | 80 ± 10 | 230 ± 20 |

| 15 | 16–23 | 70 ± 7 | 29 ± 3 | 23 ± 3 | 360 ± 40 | 2800 |

| 16 | 18–25 | 33 ± 4 | 18 ± 2 | 7.5 ± 0.9 | >1000 | >1000 |

| 17 | 20–27 | 920 | 130 ± 20 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

Sequences 1–9 are derivatives of PrRP20; sequences 10–17 are derivatives of PrRP31.

EC50 determined in a β-arrestin recruitment assay using GPR10-overexpressing CHO-K1 cells. Cells were treated with the peptides at varying concentrations in triplicate for 90 min at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Luminescence was measured and plotted against log agonist concentration. The slope was fitted in Prism to generate the EC50, reported as mean ± SEM (n = 3).

Through a combination of a localized “depot” effect at the injection site and subsequent binding to serum albumin, fatty acids are commonly conjugated to peptides to prolong their duration of action. Examples of lipidated peptides include insulin detemir,37 insulin degludec,38 glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogs such as liraglutide39 and semaglutide,40 and relaxin analogs.41 We synthesized a number of staples incorporating multiple ethylene glycol-linked fatty acids (MEG-FA) (Figure 1). Staple S2 features four ethylene glycol units terminating in a myristoyl group, S3 features three ethylene glycol units with a terminal octadecanedioic acid moiety, and S4 features four ethylene glycol units attached to octadecanedioic acid via a lysine linker incorporating an internal carboxylate moiety. S4 is similar in structure to the lipid protractor used for semaglutide, which exhibits favorable binding to human serum albumin.39 This modification significantly enhances semaglutide’s half-life, which renders it suitable as a long-acting peptide therapeutic for once-weekly administration. We also observed superior solubility for peptides stapled with S3 and S4, presumably due to the presence of additional carboxylic acid moieties attached to the staple.

Upon conjugation of sequence 3 with staple S2, the resulting C(4–11) analog 3-S2 showed improved potency (EC50 = 3.9 nM) compared to native PrRP20. Conversely, a significant (10-fold) loss of potency was observed upon conjugation with S3 or S4 staples.

Despite the high potency of stapled analogs of sequence 3 (derived from the PrRP20 sequence), we decided to further screen dicysteine mutants based on the PrRP31 sequence due to the superior in vivo efficacy of lipidated PrRP31 analogs over PrRP20 in previous studies.15,16 As summarized in Table 1, we discovered that dicysteine mutations at positions 6–13, 15–22, and 18–25 were best tolerated (sequence 11, 14, and 16, respectively) and that dicysteine mutations at positions 9–16, 6–23, and 20–27 were not tolerated (12, 15, and 17, respectively). Similarly, stapled analogs 11-S2, 14-S2, and 16-S2 showed potent activation of GPR10, with EC50s of 13, 6.1, and 7.5 nM, respectively. However, when these three peptides were conjugated with staples S3 and S4, the potencies were significantly reduced, with relatively less reduction for 11-S3/S4 and 14-S3/S4 than for 16-S3/S4. S3 and S4 were anticipated to be beneficial with regards to half-life extension based on their similarity to the fatty acid used for semaglutide (see above). Taken together, sequence 11 was moved forward for further optimization of potency and stability (11-S3 and 11-S4).

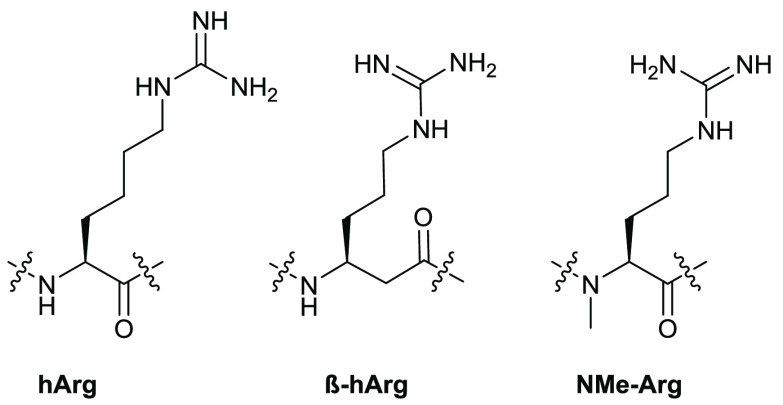

In order to prevent methionine oxidation, we replaced Met8 with norleucine (Nle) in sequence 11.42 Native PrRP peptides are generally not stable, and even in normal phosphate buffered saline, we observed cleavage sites between Arg23 and Gly24 and between Arg30 and Phe31. To address this we replaced Arg23 and Arg30 with homoarginine (hArg), β-homoarginine (β-hArg), and N-methylarginine (NMe-Arg) (Figure 2 and Table 2). Any modification of Arg in position 30 reduced the potency significantly (sequences 21, 22, and 23). Substitution at position 23 with hArg (sequence 18) or β-hArg (sequence 19) was well tolerated, while NMe-Arg at this position exhibited a 3-fold drop in potency (sequence 20).

Figure 2.

Structures of Arg residue analogs substituted at observed cleavage sites to improve proteolytic stability.

Table 2. Optimization of Sequence and Staple MEG-FA for C(6-13) PrRP31.

| GPR10

EC50 (nM)a |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sequence | residue 8 | residue 23 | residue 30 | no staple | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 |

| PrRP31 | Met | Arg | Arg | 12 ± 3 | - | - | - | - |

| 11 | ″ | ″ | ″ | 29 ± 5 | 20 ± 3 | 13 ± 2 | 80 ± 10 | 260 ± 20 |

| 18 | Nle | hArg | ″ | 17 ± 2 | 10 ± 1 | 9.1 ± 0.9 | 26 ± 3 | 80 ± 10 |

| 19 | ″ | β-hArg | ″ | 13 ± 2 | 16 ± 2 | 5.1 ± 0.7 | 60 ± 7 | 81 ± 8 |

| 20 | ″ | NMe-Arg | ″ | 44 ± 5 | 34 ± 4 | 8.8 ± 0.8 | 120 ± 20 | 160 ± 20 |

| 21 | ″ | Arg | hArg | >200 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| 22 | ″ | ″ | β-hArg | >200 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| 23 | ″ | ″ | NMe-Arg | 100 ± 10 | 100 ± 10 | 10 ± 1 | 280 ± 30 | 1100 |

EC50 determined in a β-arrestin recruitment assay using GPR10-overexpressing CHO-K1 cells. Mean ± SEM (n = 3).

We further explored the effect of fatty acid moiety structure on activity by synthesizing additional staples, including S5–S9 (Figure S1). Variants incorporating differing fatty acid chain lengths were synthesized, including derivatives of S2 (S5 and S6) and S4 (S7 and S8). A version of S4 incorporating a shorter MEG spacer was also synthesized (S9).

A significant reduction in apparent activity was observed for fatty acid-conjugated peptides in the presence of 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). This effect was attributed to sequestration of the conjugates by serum proteins in the culture medium, indicating favorable serum protein binding, and potentially extended in vivo half-life.39 In order to investigate this serum shift effect, the GPR10 β-arrestin recruitment assay was performed in the presence of 10% or 0% FBS (Table 3). A clear relationship is observed between serum shift and lipid moiety type. Peptides conjugated with S1 (no fatty acyl group), S2, or S2 derivatives (S5 and S6) do not show a large shift in potency (ratio < 5), indicating weaker serum binding. Linker S4 and derivatives S7 and S8 show the strongest shift (ratio 10–35), indicating strong binding to serum albumin. Changing the fatty acid chain length (18-S7 and 18-S8) or MEG length (18-S9) does not appear to improve serum binding drastically for S4 derivatives.

Table 3. Optimization of Staple MEG-FA for Nle8, hArg23, and C(6-13) PrRP31.

| GPR10 |

NPFF2R |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (nM)a |

EC50 (nM)b |

|||||||

| compound | residue 8 | residue 23 | 10% FBS | 0% FBS | ratio 10%/0% FBS | 10% FBS | 0% FBS | ratio NPFF2R/GPR10c |

| 18-S1 | Nle | hArg | 10 ± 1 | 5.9 ± 0.8 | 1.7 | 1200 | 920 | 160 |

| 18-S2 | ″ | ″ | 9.1 ± 0.9 | 8.0 ± 0.7 | 1.1 | 220 ± 20 | 150 | 19 |

| 18-S3 | ″ | ″ | 26 ± 3 | 12 ± 1 | 2.2 | >10 000 | 470 | 39 |

| 18-S4 | ″ | ″ | 80 ± 10 | 7.8 ± 0.6 | 10 | >10 000 | 520 | 67 |

| 18-S5 | ″ | ″ | 42 ± 4 | 12 ± 1 | 3.5 | 310 ± 30 | 270 | 23 |

| 18-S6 | ″ | ″ | 39 ± 5 | 9 ± 1 | 4.3 | 140 ± 20 | 130 | 14 |

| 18-S7 | ″ | ″ | 830 | 24 ± 3 | 35 | ∼ 10 000 | 560 | 23 |

| 18-S8 | ″ | ″ | 120 ± 10 | 8.2 ± 0.9 | 15 | >10 000 | 9000 | 1100 |

| 18-S9 | ″ | ″ | 120 ± 20 | 10 ± 1 | 12 | ∼ 8000 | 1600 | 160 |

EC50 determined in a β-arrestin recruitment assay using GPR10-overexpressing CHO-K1 cells in the presence (10%) or absence (0%) of FBS.

EC50 determined in a cAMP reporter assay using NPFF2R-overexpressing CHO cells in the presence (10%) or absence (0%) of FBS. Mean ± SEM (n = 3). NPFF2R-overexpressing CHO cells were treated with peptides in 12-point dose–response in culture medium and 0.5 mM IBMX (3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine) to inhibit cAMP degradation, with 20 μM forskolin as positive control. The assay was carried out in triplicate for 30 min at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and cAMP detection kit from Cisbio was used to quantify cAMP accumulation.

Ratio was calculated using EC50s obtained at 0% FBS.

Endogenous PrRP peptides are reported in the literature to have EC50s of 100–300 nM at the hNPFF2 receptor in a [35S]GTPγS binding assay.11 To investigate the selectivity of our conjugates toward GPR10 vs NPFF2R, we determined NPFF2R activity for peptides with sequence 18 in the presence of 10% or 0% FBS using a cAMP activation assay in CHO cells stably overexpressing human NPFF2R. It can be clearly seen that conjugates with linkers exhibiting favorable serum binding (S4, S7–9) show a large serum shift for NPFF2R activation. Nevertheless, all peptides exhibit good selectivity (14- to 1000-fold) toward GPR10. Compound 18-S4 demonstrates a combination of good serum binding and optimal potency (EC50 = 7.8 nM in the absence of serum) and good selectivity (67-fold) toward GPR10. This peptide was therefore selected as the lead compound for in vitro plasma stability and in vivo pharmacokinetic (PK) studies.

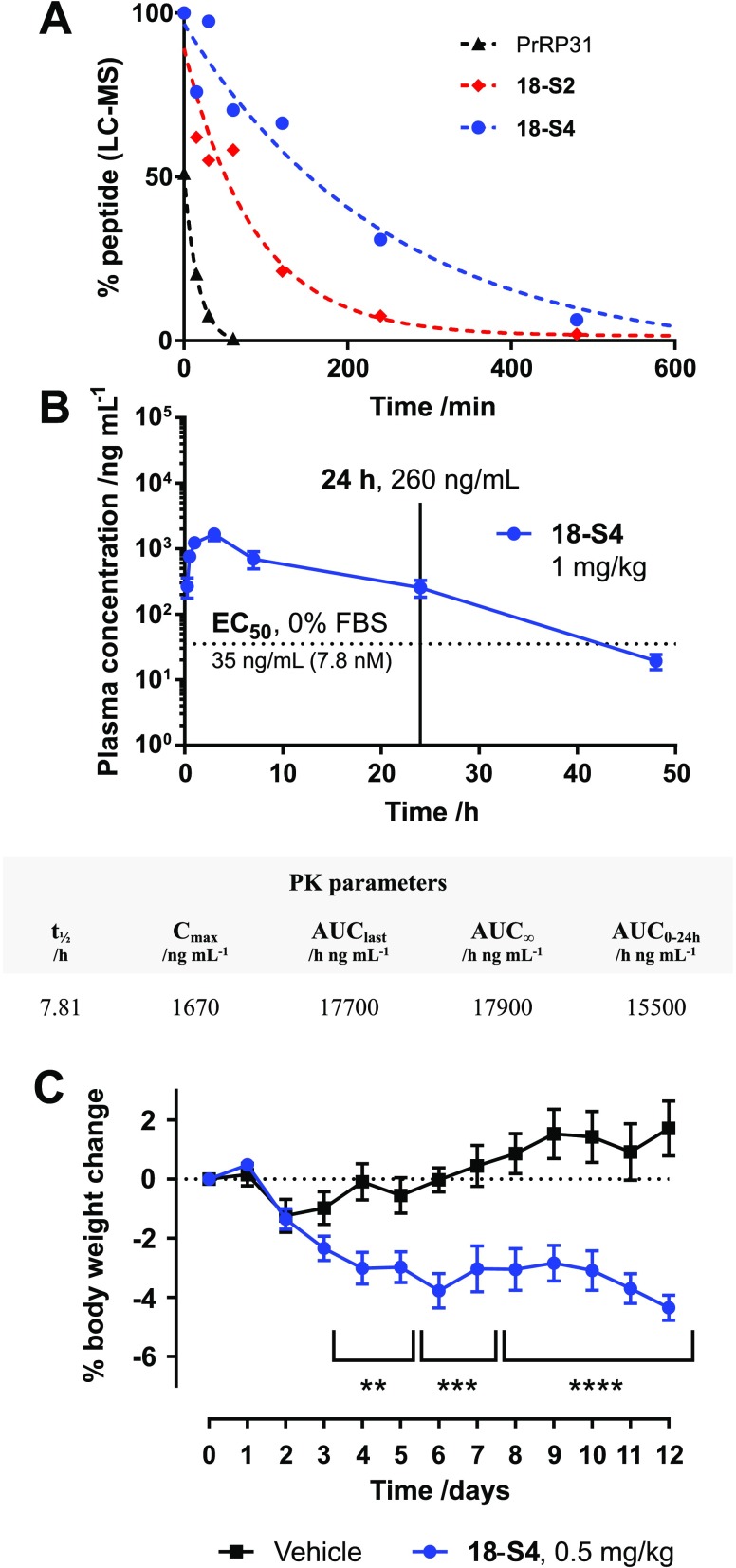

To investigate the stability of the conjugates in plasma, we incubated PrRP31, 18-S2, and 18-S4 in mouse plasma for up to 24 h (Figure 3A). The remaining intact peptide levels were quantified by LC–MS (QTOF) after precipitation of the serum proteins. The degradation of PrRP31 in mouse plasma was fast, with a half-life of ∼11 min and complete disappearance after 1 h. Stapling with S2 at positions 6–13 enhanced the stability, extending the half-life to 30–60 min. When conjugated to staple S4, the half-life was further increased to ∼3 h. We decided to select Nle8, hArg23, C(6–13) PrRP31–S4 (18-S4) for in vivo PK and efficacy studies.

Figure 3.

In vitro plasma stability of PrRP31, 18-S2, and 18-S4 (A), in vivo pharmacokinetics of 18-S4 (B), and in vivo efficacy of 18-S4 (C). Plasma stability was carried out in single replicate with incubation of peptides in mouse plasma at different time points followed by plasma protein precipitation in methanol and quantification via LC–MS. Mouse PK studies were carried out using single s.c. injection of 1 mg/kg 18-S4 in mice, and plasma samples were collected at different time points and quantified using LC–MS. PK parameters were calculated via fitting of the data using WinNonlin. Due to volume/sampling limitations in mice, sparse sampling was used. Therefore, a single PK profile was obtained by combining concentrations from various animals, and PK parameter estimates were averaged. Therefore, SEM is not reported. Efficacy was carried out in diet-induced obesity (DIO) mice, dosed daily with 18-S4 at 0.5 mg/kg s.c. or vehicle over a 12-day period (n = 8). Body weight was significantly reduced compared to vehicle treatment; **** = p ≤ 0.0001, *** = p ≤ 0.001, ** = p ≤ 0.01.

The pharmacokinetic profile of 18-S4 was evaluated in male C57BL/6 mice upon s.c. injection at 1 mg/kg (Figure 3B). The peptide plasma concentration at various time points (0.25, 0.5, 1, 3, 7, 24, 48, and 72 h) was determined using LC–MS. A Cmax of ∼1.67 μg/mL was reached at ∼3 h post-administration, with an elimination half-life of 8 h, which is similar to that of semaglutide in rodent.39 An additional PK study was carried out at 5 mg/kg dosing, and a similar pharmacokinetic profile was observed where plasma concentrations were determined using a cell-based functional assay (Figure S4).

In order to demonstrate translation of extended half-life for 18-S4 into in vivo efficacy, we carried out a 12 day body weight study in a diet-induced obesity (DIO) mouse model (n = 8 per group), with daily s.c. dosing (Figure 3C). A significant body weight reduction effect was observed for 18-S4 at 0.5 mg/kg. Interestingly, a higher dose of 5 mg/kg 18-S4 daily injection gave similar efficacy to the 0.5 mg/kg dose (Figure S3), indicating that the ED50 for 18-S4 is lower than 0.5 mg/kg. The relatively modest weight loss effect observed may be attributed to the selectivity of 18-S4 toward GPR10 and inactivity at NPFF2R, which may also explain an observed lack of significant food intake reduction (data not shown). While this selectivity appears to result in a reduced anorexigenic effect, 18-S4 is expected to exhibit a more favorable safety profile with regards to undesirable cardiovascular side effects associated with NPFF2R agonism. The 24 h plasma exposures for the 5 and 1 mg/kg PK studies are significantly higher than the EC50 for 18-S4 (Figure 3B and Figure S4), which may indicate that lower doses are required to show a dose–response effect. Detailed dose–response and efficacy studies in more chronic obesity and metabolic disease models are currently underway.

In summary, we have developed a potent, selective, long-acting PrRP analog using a strategy that combines helix stabilization with a MEG-FA serum protein binding motif. Peptide 18-S4 retained activity toward GPR10 with good selectivity over NPFF2R, exhibiting much improved plasma stability over PrRP31 and an extended in vivo half-life of 8 h. Low subcutaneous dosing of 18-S4 for 12 days showed reduced body weight compared to vehicle treatment in DIO mice, demonstrating a potent anorexigenic effect. Compound 18-S4 may offer potential as a promising lead for obesity research and warrants further evaluation in chronic obesity and metabolic disease models.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Christopher McCurdy (College of Pharmacy, University of Florida) for providing the NPFF2R CHO cell line, and Herlinda Quirino and David Huang for technical assistance and helpful discussions.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- AUC

area under the curve

- β-hArg

β-homoarginine

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- Cmax

maximum serum concentration

- CRH

corticotropin-releasing hormone

- DIO

diet-induced obesity

- EC50

half maximal effective concentration

- FA

fatty acid

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GLP-1

glucagon-like peptide-1

- GPCR/GPR

G-protein coupled receptor

- Gr3

human gustatory receptor 3

- GTP

guanosine triphosphate

- hArg

homoarginine

- IBMX

3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine

- LC–MS

liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

- MEG

multiple ethylene glycol

- N.D.

not determined

- Nle

norleucine

- NMe-Arg

N-methylarginine

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- NPFF2R

neuropeptide FF receptor 2

- PK

pharmacokinetic

- PrRP

prolactin-releasing peptide

- QTOF

quadrupole time-of-flight

- s.c.

subcutaneous

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- t1/2

half-life

- UHR-1

unknown hypothalamic receptor-1

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00182.

Synthesis and characterization of staples S1–S9 and peptides, in addition to GPCR assays, plasma stability, and in vivo study details (PDF)

Author Contributions

† These authors contributed equally to this work. E.P., C.L., H.Z., S.Y., M.S.T., V.N-T., and W.S. designed research; E.P., C.L, H.Z., S.Y., A.T., and S.L. performed research; E.P., C.L, H.Z., S.Y., S.L., S.J., and W.S. analyzed data; and S.L., E.P., C.L., H.Z., and W.S. wrote the paper.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hinuma S.; Habata Y.; Fujii R.; Kawamata Y.; Hosoya M.; Fukusumi S.; Kitada C.; Masuo Y.; Asano T.; Matsumoto H.; Sekiguchi M.; Kurokawa T.; Nishimura O.; Onda H.; Fujino M. A prolactin-releasing peptide in the brain. Nature 1998, 393 (6682), 272. 10.1038/30515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence C. B.; Celsi F.; Brennand J.; Luckman S. M. Alternative role for prolactin-releasing peptide in the regulation of food intake. Nat. Neurosci. 2000, 3 (7), 645. 10.1038/76597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence C. B.; Liu Y. L.; Stock M. J.; Luckman S. M. Anorectic actions of prolactin-releasing peptide are mediated by corticotropin-releasing hormone receptors. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2004, 286 (1), R101. 10.1152/ajpregu.00402.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarry H.; Heuer H.; Schomburg L.; Bauer K. Prolactin-releasing peptides do not stimulate prolactin release in vivo. Neuroendocrinology 2000, 71 (4), 262. 10.1159/000054544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead C. J.; Szekeres P. G.; Chambers J. K.; Ratcliffe S. J.; Jones D. N.; Hirst W. D.; Price G. W.; Herdon H. J. Characterization of the binding of [125I]-human prolactin releasing peptide (PrRP) to GPR10, a novel G protein coupled receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000, 131 (4), 683. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellacott K. L.; Lawrence C. B.; Rothwell N. J.; Luckman S. M. PRL-releasing peptide interacts with leptin to reduce food intake and body weight. Endocrinology 2002, 143 (2), 368. 10.1210/endo.143.2.8608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayanagi Y.; Matsumoto H.; Nakata M.; Mera T.; Fukusumi S.; Hinuma S.; Ueta Y.; Yada T.; Leng G.; Onaka T. Endogenous prolactin-releasing peptide regulates food intake in rodents. J. Clin. Invest. 2008, 118 (12), 4014. 10.1172/JCI34682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konyi A.; Skoumal R.; Kubin A. M.; Furedi G.; Perjes A.; Farkasfalvi K.; Sarszegi Z.; Horkay F.; Horvath I. G.; Toth M.; Ruskoaho H.; Szokodi I. Prolactin-releasing peptide regulates cardiac contractility. Regul. Pept. 2010, 159 (1–3), 9. 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson W. K.; Resch Z. T.; Murphy T. C. A novel action of the newly described prolactin-releasing peptides: cardiovascular regulation. Brain Res. 2000, 858 (1), 19. 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)02451-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T.; Mochiduki A.; Sugimoto Y.; Suzuki Y.; Itoi K.; Inoue K. Prolactin-releasing peptide regulates the cardiovascular system via corticotrophin-releasing hormone. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2009, 21 (6), 586. 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engstrom M.; Brandt A.; Wurster S.; Savola J. M.; Panula P. Prolactin releasing peptide has high affinity and efficacy at neuropeptide FF2 receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 305 (3), 825. 10.1124/jpet.102.047118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuneš J.; Pražienková V.; Popelová A.; Mikulášková B.; Zemenová J.; Maletínská L. Prolactin-releasing peptide: a new tool for obesity treatment. J. Endocrinol. 2016, 230 (2), R51. 10.1530/JOE-16-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonin F.; Schmitt M.; Laulin J. P.; Laboureyras E.; Jhamandas J. H.; MacTavish D.; Matifas A.; Mollereau C.; Laurent P.; Parmentier M.; Kieffer B. L.; Bourguignon J. J.; Simonnet G. RF9, a potent and selective neuropeptide FF receptor antagonist, prevents opioid-induced tolerance associated with hyperalgesia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103 (2), 466. 10.1073/pnas.0502090103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L.; MacTavish D.; Simonin F.; Bourguignon J. J.; Watanabe T.; Jhamandas J. H. Prolactin-releasing peptide effects in the rat brain are mediated through the Neuropeptide FF receptor. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009, 30 (8), 1585. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulášková B.; Zemenová J.; Pirník Z.; Pražienková V.; Bednárová L.; Železná B.; Maletínská L.; Kuneš J. Effect of palmitoylated prolactin-releasing peptide on food intake and neural activation after different routes of peripheral administration in rats. Peptides 2016, 75, 109. 10.1016/j.peptides.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pražienková V.; Holubová M.; Pelantová H.; Bugáňová M.; Pirník Z.; Mikulášková B.; Popelová A.; Blechová M.; Haluzík M.; Železná B.; Kuzma M.; Kuneš J.; Maletínská L. Impact of novel palmitoylated prolactin-releasing peptide analogs on metabolic changes in mice with diet-induced obesity. PLoS One 2017, 12 (8), e0183449 10.1371/journal.pone.0183449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maletínská L.; Nagelová V.; Tichá A.; Zemenová J.; Pirník Z.; Holubová M.; Špolcová A.; Mikulášková B.; Blechová M.; Sýkora D.; Lacinová Z.; Haluzík M.; Železná B.; Kuneš J. Novel lipidized analogs of prolactin-releasing peptide have prolonged half-lives and exert anti-obesity effects after peripheral administration. Int. J. Obes. 2015, 39, 986. 10.1038/ijo.2015.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pražienková V.; Tichá A.; Blechová M.; Špolcová A.; Železná B.; Maletínská L. Pharmacological characterization of lipidized analogs of prolactin-releasing peptide with a modified C- terminal aromatic ring. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2016, 67 (1), 121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulášková B.; Holubová M.; Pražienková V.; Zemenová J.; Hrubá L.; Haluzík M.; Železná B.; Kuneš J.; Maletínská L. Lipidized prolactin-releasing peptide improved glucose tolerance in metabolic syndrome: Koletsky and spontaneously hypertensive rat study. Nutr. Diabetes 2018, 8 (5), 1. 10.1038/s41387-017-0015-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holubová M.; Zemenová J.; Mikulášková B.; Panajotova V.; Stöhr J.; Haluzík M.; Kuneš J.; Železná B.; Maletínská L. Palmitoylated PrRP analog decreases body weight in DIO rats but not in ZDF rats. J. Endocrinol. 2016, 229 (2), 85. 10.1530/JOE-15-0519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold D. A.; Luckman S. M. Prolactin-releasing peptide mediates cholecystokinin-induced satiety in mice. Endocrinology 2006, 147 (10), 4723. 10.1210/en.2006-0753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W.; Geddes B. J.; Zhang C.; Foley K. P.; Stricker-Krongrad A. The prolactin-releasing peptide receptor (GPR10) regulates body weight homeostasis in mice. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2004, 22 (1–2), 93. 10.1385/JMN:22:1-2:93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deluca S. H.; Rathmann D.; Beck-Sickinger A. G.; Meiler J. The activity of prolactin releasing peptide correlates with its helicity. Biopolymers 2013, 99 (5), 314. 10.1002/bip.22162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roumeas L.; Humbert J. P.; Schneider S.; Doebelin C.; Bertin I.; Schmitt M.; Bourguignon J. J.; Simonin F.; Bihel F. Effects of systematic N-terminus deletions and benzoylations of endogenous RF-amide peptides on NPFF1R, NPFF2R, GPR10, GPR54 and GPR103. Peptides 2015, 71, 156. 10.1016/j.peptides.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathmann D.; Lindner D.; DeLuca S. H.; Kaufmann K. W.; Meiler J.; Beck-Sickinger A. G. Ligand-mimicking receptor variant discloses binding and activation mode of prolactin-releasing peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287 (38), 32181. 10.1074/jbc.M112.349852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walensky L. D.; Bird G. H. Hydrocarbon-stapled peptides: Principles, practice, and progress. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57 (15), 6275. 10.1021/jm4011675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. – W.; Grossmann T. N.; Verdine G. L. Synthesis of all-hydrocarbon stapled α-helical peptides by ring-closing olefin metathesis. Nat. Protoc. 2011, 6 (6), 761. 10.1038/nprot.2011.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D. Y.; King D. S.; Chmielewski J.; Singh S.; Schultz P. G. General approach to the synthesis of short α-helical peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113 (24), 9391. 10.1021/ja00024a067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verdine G. L.; Hilinski G. J. Stapled peptides for intracellular drug targets. Methods Enzymol. 2012, 503, 3. 10.1016/B978-0-12-396962-0.00001-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muppidi A.; Doi K.; Edwardraja S.; Drake E. J.; Gulick A. M.; Wang H. G.; Lin Q. Rational design of proteolytically stable, cell-permeable peptide-based selective Mcl-1 inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (36), 14734. 10.1021/ja306864v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y. S.; Graves B.; Guerlavais V.; Tovar C.; Packman K.; To K. H.; Olson K. A.; Kesavan K.; Gangurde P.; Mukherjee A.; Baker T.; Darlak K.; Elkin C.; Filipovic Z.; Qureshi F. Z.; Cai H.; Berry P.; Feyfant E.; Shi X. E.; Horstick J.; Annis D. A.; Manning A. M.; Fotouhi N.; Nash H.; Vassilev L. T.; Sawyer T. K. Stapled alpha-helical peptide drug development: a potent dual inhibitor of MDM2 and MDMX for p53-dependent cancer therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110 (36), E3445 10.1073/pnas.1303002110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevola L.; Giralt E. Modulating protein-protein interactions: the potential of peptides. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51 (16), 3302. 10.1039/C4CC08565E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muppidi A.; Zou H.; Yang P.-Y.; Chao E.; Sherwood L.; Nunez V.; Woods A. K.; Schultz P. G.; Lin Q.; Shen W. Design of potent and proteolytically stable oxyntomodulin analogs. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11 (2), 324. 10.1021/acschembio.5b00787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P. Y.; Zou H.; Chao E.; Sherwood L.; Nunez V.; Keeney M.; Ghartey-Tagoe E.; Ding Z.; Quirino H.; Luo X.; Welzel G.; Chen G.; Singh P.; Woods A. K.; Schultz P. G.; Shen W. Engineering a long-acting, potent GLP-1 analog for microstructure-based transdermal delivery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113 (15), 4140. 10.1073/pnas.1601653113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P. Y.; Zou H.; Lee C.; Muppidi A.; Chao E.; Fu Q.; Luo X.; Wang D.; Schultz P. G.; Shen W. Stapled, long-acting glucagon-like peptide 2 analog with efficacy in dextran sodium sulfate induced mouse colitis models. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61 (7), 3218. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lear S.; Amso Z.; Shen W. Engineering PEG-fatty acid stapled, long-acting peptide agonists for G protein-coupled receptors. Methods Enzymol. 2019, 622, 183. 10.1016/bs.mie.2019.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havelund S.; Plum A.; Ribel U.; Jonassen I.; Volund A.; Markussen J.; Kurtzhals P. The mechanism of protraction of insulin detemir, a long-acting, acylated analog of human insulin. Pharm. Res. 2004, 21 (8), 1498. 10.1023/B:PHAM.0000036926.54824.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tambascia M. A.; Eliaschewitz F. G. Degludec: the new ultra-long insulin analogue. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2015, 7, 57. 10.1186/s13098-015-0037-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen P. J.; Fledelius C.; Knudsen L. B.; Tang-Christensen M. Systemic administration of the long-acting GLP-1 derivative NN2211 induces lasting and reversible weight loss in both normal and obese rats. Diabetes 2001, 50 (11), 2530. 10.2337/diabetes.50.11.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau J.; Bloch P.; Schaffer L.; Pettersson I.; Spetzler J.; Kofoed J.; Madsen K.; Knudsen L. B.; McGuire J.; Steensgaard D. B.; Strauss H. M.; Gram D. X.; Knudsen S. M.; Nielsen F. S.; Thygesen P.; Reedtz-Runge S.; Kruse T. Discovery of the once-weekly glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogue semaglutide. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58 (18), 7370. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muppidi A.; Lee S. J.; Hsu C.-H.; Zou H.; Lee C.; Pflimlin E.; Mahankali M.; Yang P.-Y.; Chao E.; Ahmad I.; Crameri A.; Wang D.; Woods A.; Shen W. Design and synthesis of potent, long-acting lipidated relaxin-2 analogs. Bioconjugate Chem. 2019, 30 (1), 83. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirník Z.; Železná B.; Kiss A.; Maletínská L. Peripheral administration of palmitoylated prolactin-releasing peptide induces Fos expression in hypothalamic neurons involved in energy homeostasis in NMRI male mice. Brain Res. 2015, 1625, 151. 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.