Abstract

Despite several years of research, only a handful of β-secretase (BACE) 1 inhibitors have entered clinical trials as potential therapeutics against Alzheimer’s disease. The intrinsic basic nature of low molecular weight, amidine-containing BACE 1 inhibitors makes them far from optimal as central nervous system drugs. Herein we present a set of novel heteroaryl-fused piperazine amidine inhibitors designed to lower the basicity of the key, enzyme binding, amidine functionality. This study resulted in the identification of highly potent (IC50 ≤ 10 nM), permeable lead compounds with a reduced propensity to suffer from P-glycoprotein-mediated efflux.

Keywords: BACE inhibitor, β-secretase 1, Alzheimer’s disease, cyclic sulfamidates, pKa

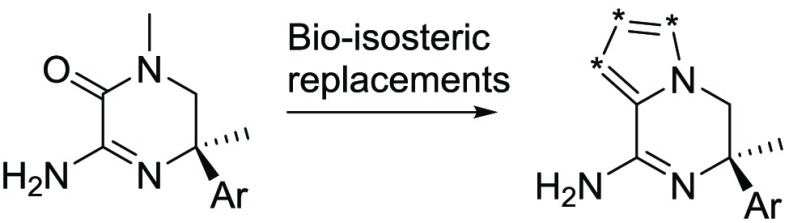

Genetics has suggested β-secretase 1 (BACE 1) as a key target to attenuate the formation of amyloid beta (Aβ) in Alzheimer’s disease (AD).1 Since the discovery of BACE 1 in 1999,2 many potent BACE 1 inhibitors have been described,3 but relatively few successfully combined in vitro potency and the necessary pharmacokinetic (PK) properties/parameters to achieve in vivo efficacy. The amidine class of BACE 1 inhibitors has become the main focus3,4 and contain a protonated amidine warhead necessary for an optimal interaction with the aspartyl catalytic dyad of BACE 1.3 The high intrinsic basicity of amidine heterocycles presents multiple liabilities for their development including high P-glycoprotein (Pgp) efflux and hERG inhibition, and low permeability. Several compounds have unfortunately failed clinical trials including MK-8931 (1)5 and LY-2886721 (2) (Figure 1).6

Figure 1.

Representative BACE 1 inhibitors.

Our interest in amidine BACE 1 inhibitors can be traced back to early reports of aminodihydroquinazolines.7 Since then we have been dedicated to identifying novel warheads with adequate substitution to control the pKa of the guanidine/amidine and as such balance the liabilities with in vivo efficacy. Thus, the challenge of BACE 1 inhibition is revealed: liabilities are inherent to the amidine, yet it is crucial for key binding motifs. To be capable of identifying BACE 1 clinical candidates, there is a need to efficiently synthesize and evaluate many novel but synthetically challenging amidine containing heterocycles. Here we describe a convergent approach to meet this goal.

We have previously described our approach to assess new candidate warheads with computational approaches leading to series of cyclic amidines,8 acylguanidines,9 and aminopiperazinones such as 3 (Figure 1).10 The aminopiperazinones suffered from poor brain penetration, which halted their progress. However, they served as inspiration for further research such as a series of aminomorpholine containing BACE 1 inhibitors. The morpholine series, exemplified by JNJ-50138803 (4) (Figure 1), was also supported by in silico work, and its optimization has been described.11,12 The initial prototypes displayed high pKa values (9 < pKa < 9.6) and a strong Pgp-mediated efflux liability.11 To attenuate the issues attributed to the elevated pKa, the amidine warhead was carefully modified with fluorine containing electron withdrawing substituents at position C-2 of the morpholine ring. This optimization focused on achieving a pKa within the range of 6.5–7.5. The evolution of the series ultimately culminated with the identification of 4 (Figure 1), a recently disclosed clinical candidate.12

Besides the exploration of the morpholine series, here we described a parallel effort using bioisosteric replacements of the amide in the aminopiperazinone warhead (3). We focused on replacing this amide functional group by nitrogen-containing fused five membered heteroaromatic rings, where a bridge head nitrogen was maintained.

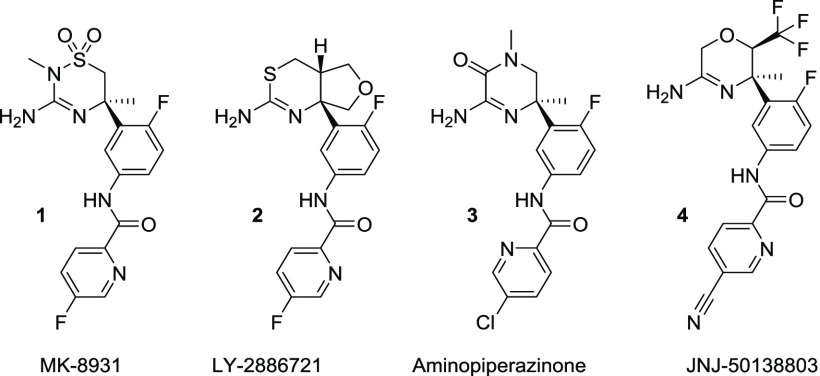

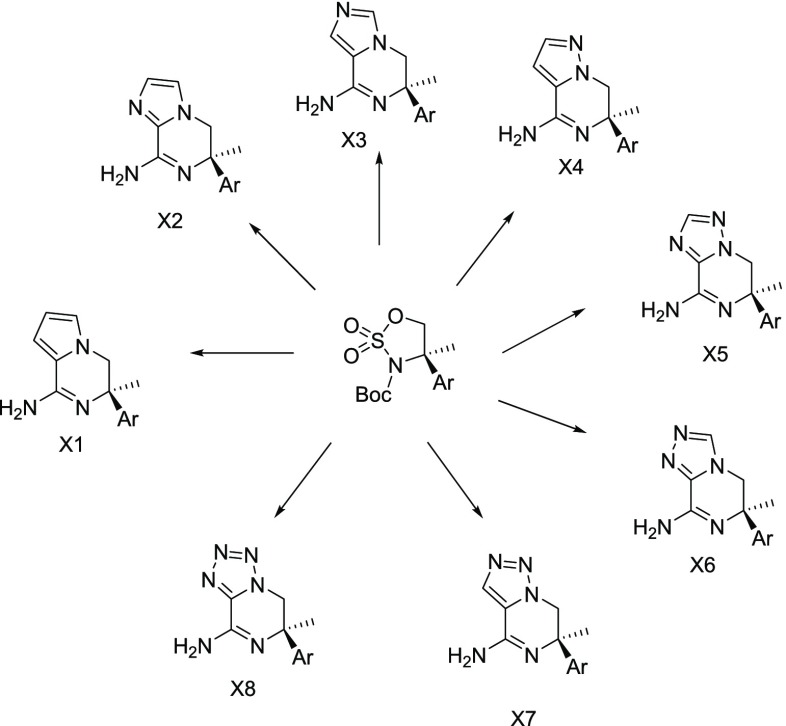

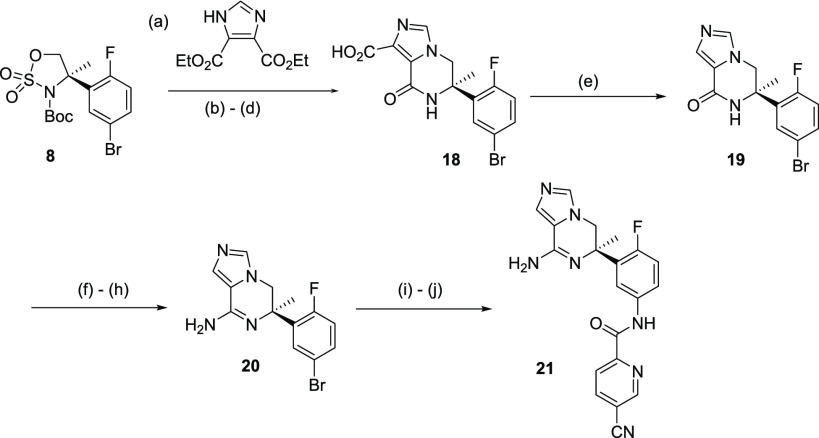

To validate our approach, we initially synthesized the imidazolopiperazine warhead (5) with identical decoration to the reported aminopiperazinone (Table 1). Similar potency in both the BACE 1 cellular and enzymatic assays was observed, which gave an immediate indication that this could offer a promising avenue for deeper exploration. Therefore, an efficient and versatile synthetic route based on the ring opening of a cyclic sulfamidate intermediate (8) was developed, which enabled the synthesis of the bicyclic warheads X1–X8, shown in Figure 2.

Table 1. BACE 1 Enzymatic Activity and Cellular Activity for Prototypes Aminopiperazinone 3 and Imidazolopiperazine 5.

Figure 2.

Proposed aminopiperazinone bisosteric replacements X1–X8 from common sulfamidate intermediate.

Chemistry

Cyclic sulfamidates have emerged as important and versatile intermediates in organic synthesis because of their established ability to undergo highly selective reactions with O-, S-, N-, C-, P-, and F-based nucleophiles.13 We reasoned that nitrogen-containing heteroaromatics could be suitable nucleophiles to ring open adequately substituted sulfamidates leading to intermediates which could then be further elaborated to yield the targeted warheads (Figure 2).

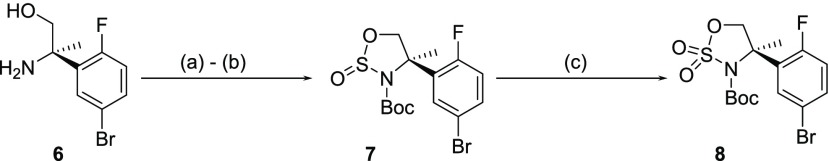

Key cyclic sulfamidate 8 was by Boc protection of the β-amino alcohol 6,11 followed by cyclization with thionyl chloride in acetonitrile at −40 °C afforded the corresponding sulfamidite 7 in 93% yield over two steps. This was then oxidized to the target sulfamidate 8 using NaIO4 and a catalytic amount of RuCl3 in acetonitrile/water with excellent yield (Scheme 1).14

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Cyclic Sulfamidate 8.

Reagents and conditions: (a) (Boc)2O, NaHCO3 aq, THF, rt, 2.5 d; (b) SOCl2, MeCN, 2 h, rt (93% yield over 2 steps); (c) RuCl3, NaIO4, CAN, MeCN/H2O, 2 h, rt (95% yield).

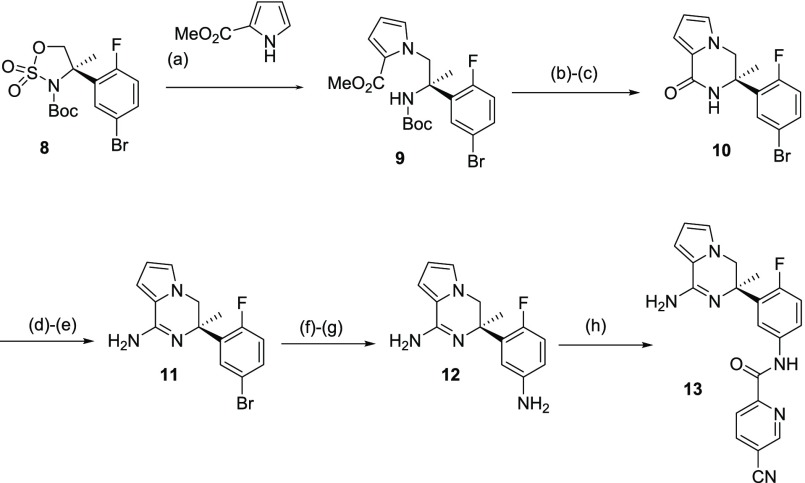

With sulfamidate 8 in hand, we studied its nucleophile induced ring opening reaction with several nitrogen-containing heteroaromatics. Sulfamidate 8 was successfully ring opened using methyl 1H-pyrrole-2-carboxylate in the presence of cesium carbonate in acetonitrile to afford 9 in 84% yield (Scheme 2). The resulting intermediate 9 was then deprotected and cyclized by sequential treatment with HCl in dioxane, followed by sodium methoxide to afford lactam 10, in 22% yield for the two steps. Lactam 10 was then elaborated to the targeted warhead by initial alkylation to form an imino-ether intermediate, and subsequent reaction with ammonia in EtOH to form the desired amidine 11, in 33% yield over the two transformations. While there are many techniques to convert aryl bromides to the corresponding anilines, and alternatives are described vide infra, on this occasion we used a Büchwald coupling using the benzophenone imine, which was subsequently hydrolyzed to the corresponding aniline 12. Subsequent chemo-selective coupling of the carboxylic acid was mediated by 4-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride (DMTMM).15 This reagent is designed to activate the carboxylic acid and concomitantly protonate the most basic center, subsequently promoting the chemo-selective amide formation on the least basic center, giving 13, in 50% yield.15

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Pyrrolopiperazine BACE 1 Inhibitor 13(16).

Reagents and conditions: (a) Cs2CO3, MeCN, 130 °C MW, 30 min (84% yield); (b) HCl (4 N in 1,4-dioxane), rt, 18 h; (c) MeONa, MeOH, 60 °C, 16 h (22% yield over 2 steps); (d) OMe3BF4, DCM, rt, 4 d; (e) NH4Cl, NH3 (2 M in MeOH), EtOH, 80 °C, 48 h (33% yield from 10); (f) Pd2(dba)3, BINAP, NatBuO, benzophenone-imine, 100 °C, 2 h; (g) HCl (6 N in iPrOH) 1 h, rt; (h) 5-cyanopyridine-2-carboxylic acid, DMTMM, MeOH, 0 °C to rt, 3 h (50% yield from 11).

The regioisomeric imidazolepiperazine warheads 5, 17, and 21 were also accessed using cyclic sulfamidate 8. Reaction of 2-cyanoimidazole with 8 in the presence of DBU afforded 14 in 97% yield (Scheme 3). HCl promoted cleavage of the Boc group in 14 occurred with concomitant cyclization to amidine 15 in 71% yield. The aryl bromide was then converted to aniline 16 using sodium azide and copper iodide in a solution of dimethylene ethylene diamine and DMSO in 75% yield. The regioselective amide formation was again achieved using DMTMM to afford the final products 5 and 17 in 45% and 57% yield, respectively.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Imidazolopiperazine BACE 1 Inhibitors 5 and 17.

Reagents and conditions: (a) DBU, ACN, 90 °C, 16 h (97% yield); (b) HCl (4 N in 1,4-dioxane), 70 °C, 4 h (71% yield); (c) NaN3, DMEDA, CuI, Na2CO3, DMSO, 110 °C, 24 h (75% yield); (d) (5) 5-chloro-pyridine-2-carboxylic acid or 5-cyanopyridine-2-carboxylic acid, DMTMM, MeOH, 0 °C to rt, 24 h (45–57% yield).

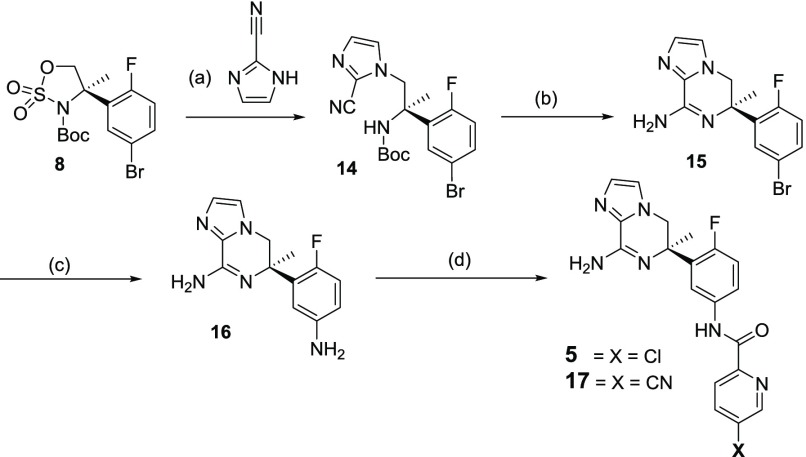

For the preparation of 21, due to the lack of symmetry and difference in reactivity, ethylimidazole-4-carboxylate could not be used to open the cyclic sulfamidate. Instead, reaction of 8 with symmetrical diethyl-1H-imidazole-4,5-dicarboxylate yielded the expected product in 88% yield (Scheme 4). Subsequent Boc deprotection, followed by sodium methoxide mediated intramolecular cyclization, afforded lactam 18 (55% yield over 3 steps). Decarboxylation by treatment with NaOH and heating in DMSO led to 19. Treatment of 19 with phosphorus pentasulfide to the thio-lactam and subsequent S-methylation followed by treatment with ammonia yielded amidine 20. Target compound 21 was obtained from 20 following analogous conditions to those described in Schemes 2 and 3.17

Scheme 4. Synthesis of Imidazolopiperazine BACE 1 Inhibitor 21.

Reagents and conditions: (a) DBU, ACN, 90 °C, 5 h, (88% yield); (b) HCl (4 M in 1,4-dioxane), 1,4-dioxane, 70 °C, 15 h; (c) NaOMe, MeOH, 55 °C, 5 h (55% yield over 3 steps); (d) 1 N NaOH, MeOH, rt, 1 h; (e) DMSO, 120 °C, 2 h (62% yield over 3 steps); (f) P2S5, pyridine, 110 °C, 16 h; (g) MeI, K2CO3, acetone, 16 h, rt; (h) NH4Cl, NH3 (7 M in MeOH), 80 °C, 48 h (35% yield over 3 steps); (i) NaN3, DMEDA, CuI, Na2CO3, DMSO, 110 °C, 4 h; (j) 5-cyanopyridine-2-carboxylic acid, DMTMM, MeOH, 0 °C to rt, 24 h (33% yield over 2 steps).

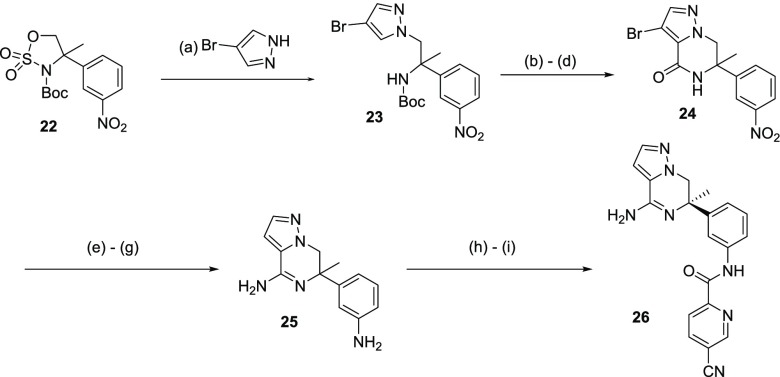

Pyrazolopiperazine analog 26 could be prepared by reaction of cyclic sulfamidate 22(18) with 4-bromopyrazole; this was achieved in good yield using cesium carbonate in dimethyl sulfoxide to yield 23 (Scheme 5). Cyclic sulfamidate 22 was synthesized in an analogous way to cyclic sulfamidate 8, previously described in Scheme 1, albeit racemically, thus requiring that the final compound undergo chiral separation, which in the case of 26 was achieved using chiral SFC. Intermediate 23 was deprotonated with LDA and reacted with ethylchloroformate to form the lactam precursor. This was then cyclized, after TFA-mediated Boc deprotection, by treatment with KOAc in refluxing ethanol. Lactam 24 was elaborated to the amidine via generation of the thioamide and subsequent reaction with ammonia. The aromatic nitro group in 24 was reduced to the corresponding aniline using heterogeneous catalysis, which went with concomitant bromide removal to afford 25 in excellent yields over three reaction steps (94%). The chemoselective amide formation was facilitated by DMTMM to afford the desired amide 26 in 10% yield after chiral separation.

Scheme 5. Synthesis of Pyrazolopiperazine BACE 1 Inhibitor 26.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Na2CO3, DMSO, 130 °C, 2 h (79% yield); (b) ethylchloroformate, LDA, THF, −78 °C to −50 °C, 2 h (66% yield); (c) TFA, DCM, rt, 3 h; (d) KOAc, EtOH, reflux, 4 h (87% yield over 2 steps); (e) P2S5, pyridine, 110 °C, 24 h; (f) NH4Cl, NH3 (7 M in MeOH), 100 °C, 16 h; (g) Zn, AcOH, EtOH, reflux, 24 h (37% yield over 3 steps); (h) 5-cyanopyridine-2-carboxylic acid, DMTMM, MeOH, 0 °C to rt, 4 h; (i) chiral SFC purification (10% yield over 2 steps).

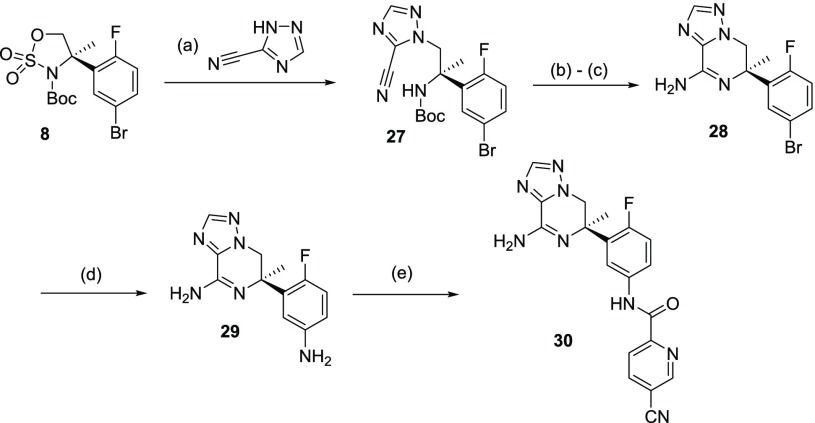

To access 1,2,4-triazolopiperazine 30, reaction of cyclic sulfamidate 8 with 1,2,4-triazole-3-carbonitrile afforded 27 in 92% yield (Scheme 6). This was then elaborated to the final compound following a very similar sequence to that previously described in Scheme 4 for the imidazolopiperazine analog 21. This started with formic acid-mediated Boc cleavage and subsequent intramolecular lactamization facilitated by trimethyl aluminum. Then amination of the bromophenyl ring in 28 by treatment with sodium azide and CuI afforded 29 in 92% yield. Regioselective amide formation led to the desired BACE 1 inhibitor 30 in 52% yield.

Scheme 6. Synthesis of 1,2,4-Triazolopiperizine BACE 1 Inhibitor 30.

Reagents and conditions: (a) KOtBu, 60 °C, 1,4-dioxane, 16 h (99% yield); (b) HCO2H, rt, 2 h; (c) AlMe3, toluene, 60 °C, 1 h (53% yield over 3 steps); (d) NaN3, DMEDA, Na2CO3, CuI, DMSO, 100 °C, 2 h (50% yield); (e) 5-cyano-pyridine-2-carboxylic acid, EDCI, HCl (6 N in iPrOH), MeOH, rt, 2 h (52% yield).

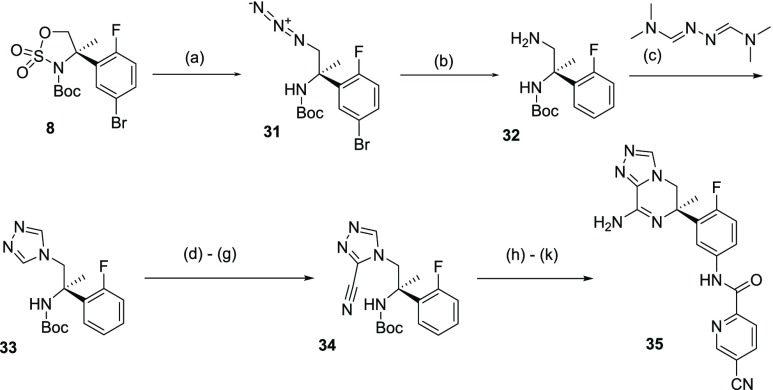

1,3,4-Triazolopiperazine 35 was accessed via ring opening of cyclic sulfamidate 8 with sodium azide to afford alkylazide 31, which, after subsequent hydrogenation, afforded diamine 32, with concomitant and undesired bromide removal (Scheme 7). Intermediate 32 was then treated with N,N′-bis(dimethylaminomethylene)hydrazine in the presence of a catalytic amount of p-TSA to afford the desired 1,3,4-triazole 33. The introduction of a nitrile functional group in the heteroaromatic ring was achieved in a four-step sequence. First, a hydroxymethyl substituent was introduced with formaldehyde in the presence of triethylamine; this primary alcohol was then selectively oxidized to the corresponding aldehyde using manganese dioxide. Finally, aldehyde condensation with hydroxylamine followed by dehydration of the intermediate oxime using oxalyl chloride afforded the desired nitrile containing intermediate 34. Boc deprotection of 34 under acidic conditions and concomitant cyclization led to the expected cyclic amidine intermediate. Nitration of the aromatic ring under standard conditions, followed by hydrogenation of the nitro group, resulted in the corresponding aniline intermediate. Final amide coupling with 5-cyanoyridine-2-carboxylic acid afforded BACE 1 inhibitor 35 in 58% yield from nitrile containing intermediate 34.

Scheme 7. Synthesis of 1,3,4-Triazolo-piperizine BACE 1 Inhibitor 35.

Reagents and conditions: (a) NaN3, DMF, 80 °C, 2 h (quantitative); (b) H2, Pd/C, TEA, MeOH, rt, 16 h (87% yield); (c) p-TSA, toluene, 130 °C, 16 h (47% yield); (d) CH2O, TEA, 100 °C, 2 h; (e) MnO2, CHCl3, rt, 1 h; (f) NH2OH·HCl, NaOAc, EtOH, 80 °C, 1.5 h; (g) CO2Cl2, TEA, EtOAc, 0 °C to rt, 2 h (31% yield over 4 steps); (h) HCO2H, 50 °C, 1 h; (i) HNO3, H2SO4, −10 °C, 30 min; (j) H2, Pd/C, MeOH, rt, 4 h; (k) 5-cyanopyridine-2-carboxylic acid, EDCI, HCl (6 N in iPrOH), MeOH, rt, 16 h (58% yield over 4 steps).

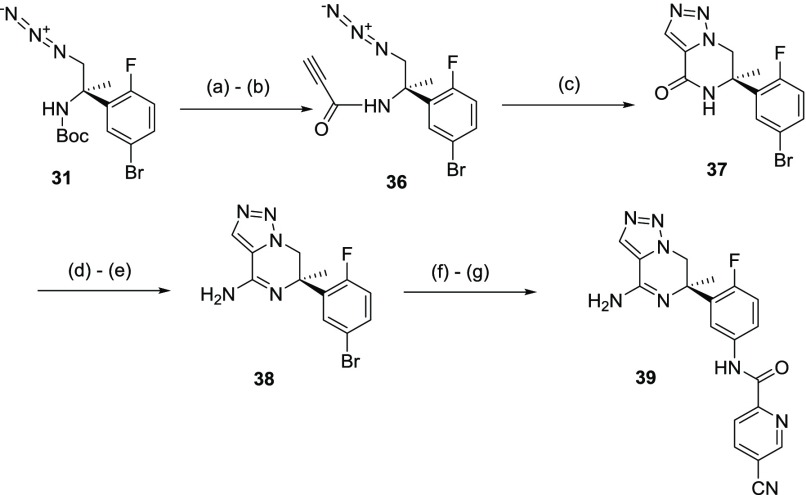

The 1,2,3-triazolopiperazine analogue 39 was prepared from intermediate 31 as outlined in Scheme 8. Boc deprotection of the amine group in 31 followed by coupling with propiolic acid led to amide 36; the resulting intermediate was double cyclized under thermal conditions to afford 37. Lactam 37 was elaborated to amidine 38 following a similar procedure as described in Scheme 5. Subsequent chemoselective amide coupling with 5-cyano-pyridine-2-carboxylic acid led to BACE 1 inhibitor 39.19

Scheme 8. Synthesis of 1,2,3-Triazolo-piperizine BACE 1 Inhibitor 39.

Reagents and conditions: (a) HCl (4 N in 1,4-dioxane), rt, 24 h; (b) propiolic acid, DCC, DCM, 0 °C, 2 h; (c) toluene, 70 °C, 18 h (78% yield over 3 steps); (d) P2S5, 1,4-dioxane, 95 °C, 2 h; (e) NH3 (7 M in MeOH), 75 °C, 2 h; (f) NaN3, DMEDA, Na2CO3, CuI, DMSO, 110 °C, 5 h; (g) 5-cyanopyridine-2-carboxylic acid, EDCI, HCl (6 N in iPrOH), MeOH, rt, 3 h (39% yield over 4 steps).

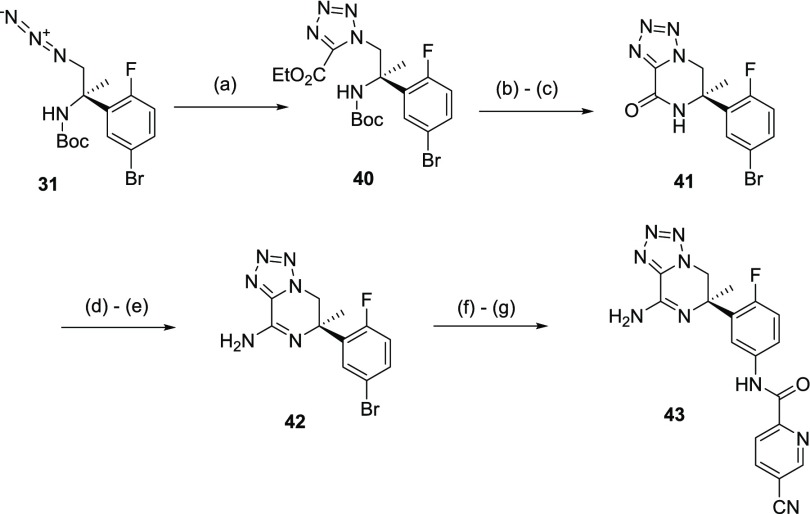

Compound 43 containing a fused tetrazole ring was again generated from intermediate 31, as shown in Scheme 9. Intermediate 31 initially underwent a 1,3-dipolar cyclization with ethyl cyanoformate to afford tetrazole 40. Acid-mediated Boc deprotection, followed by cyclization, gave lactam 41. Lactam 41 was converted to the corresponding amidine 42, as described in Schemes 5 and 7. Bromide 42 was converted to the aniline, which underwent chemoselective amide formation to yield BACE 1 inhibitor 43.

Scheme 9. Synthesis of Tetrazolo-piperizine BACE 1 Inhibitor 43.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Ethylcyanoformate, 120 °C, 20 h; (b) TFA, DCM, rt, 2 h; (c) K2CO3, EtOH, reflux, 20 h (75% yield over 3 steps); (d) P2S5, 1,4-dioxane, 95 °C, 2 h; (e) NH3 (7 M in MeOH), 70 °C, 18 h; (f) NaN3, DMEDA, Na2CO3, CuI, DMSO, 110 °C, 2 h; (g) 5-cyanopyridine-2-carboxylic acid, EDCI, HCl (6 N, iProH), MeOH, rt, 2 h (5% yield over 4 steps).

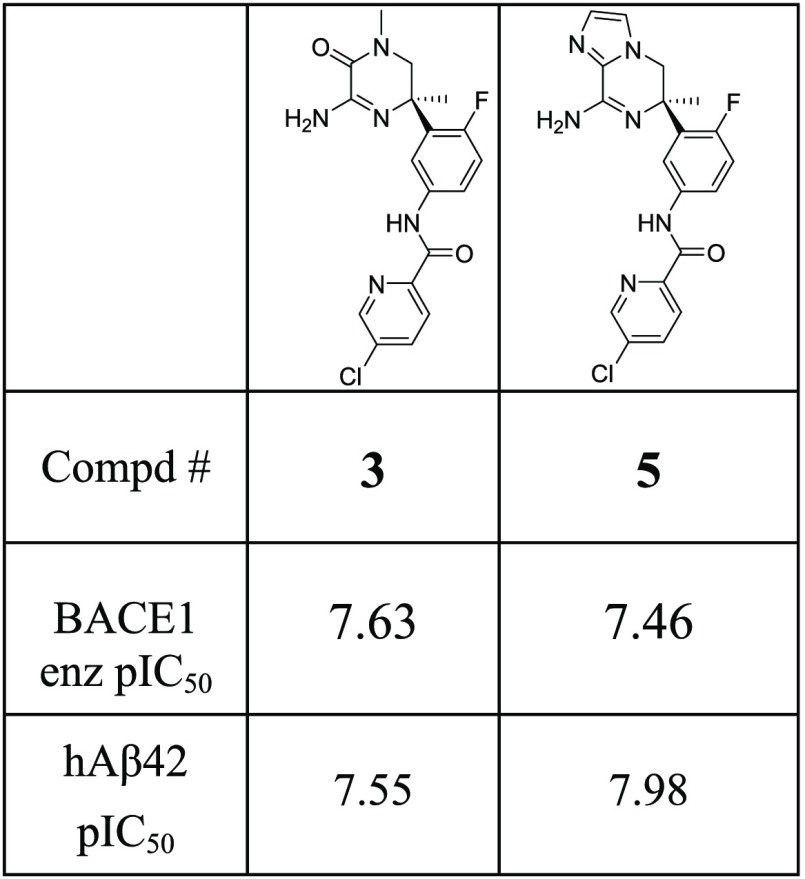

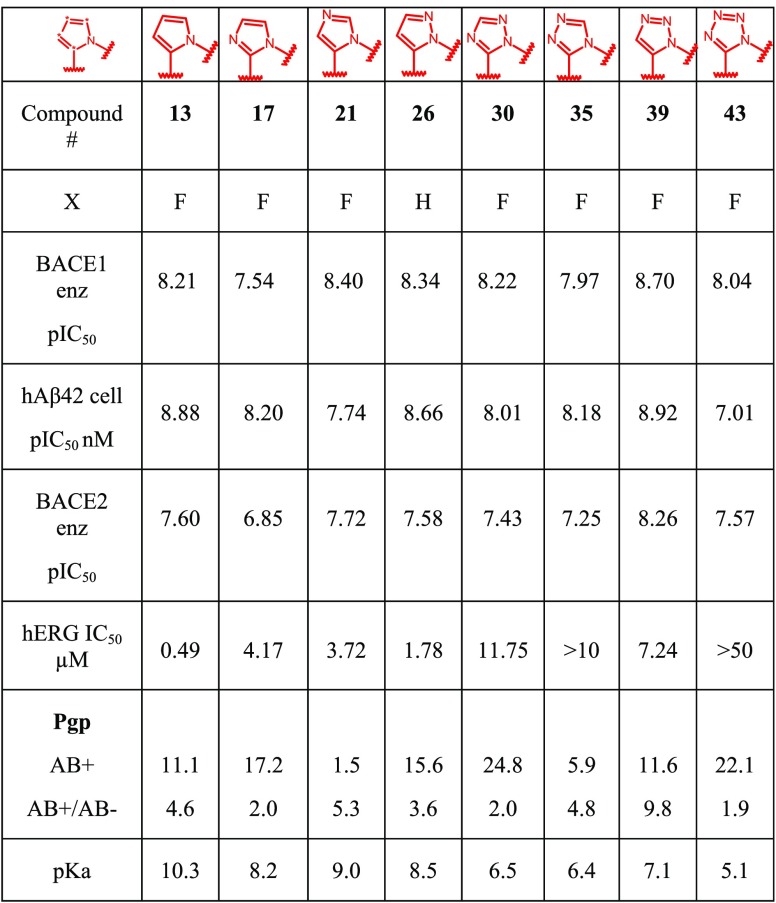

The resulting eight bicyclic heteroaryl-fused aminopiperazine BACE 1 inhibitors 13, 17, 21, 26, 30, 35, 39, and 43 provide an excellent opportunity for the side-by-side comparison of the effect of the fused heterocycle. They were profiled for their BACE 1 and 2 inhibitory activity in both our enzymatic assay and also cellular BACE1 assay, Table 2. Cathepsin D was not measured for this series of compounds as it is known that the expansion to the S3 pocket via the amide linked heteroaromatic removes the Cathepsin D activity.20

Table 2. Overview of BACE 1 Inhibitor in Vitro Profile.

See Supporting Information for assay details.

Most compounds showed high cellular potency in the range of pIC50 7.7–8.9. The low activity observed for the tetrazole derivative 43 (hAβ42 cell pIC50 = 7.01) was attributed to the low basicity of the amidine function (pKa = 5.1). In general, we have observed a dependency for BACE 1 cellular potency with pKa. This is rationalized by the BACE 1 cellular location in the endosomes, an acidic compartment that favors basic compound distribution,21 and the need to interact with the catalytic aspartates.

Our working hypothesis is that the optimal pKa for a BACE 1 inhibitor should be in the range of 6.5–8.5. Higher pKa values are tolerated and, in some cases, result in increased cellular potency. As demonstrated with compounds 13 and 43, compound 13 has a pKa of 10.3, and this is translated into a cellular potency of pIC50 of 8.88; compound 43 has the lowest pKa of 5.1 and has a cellular potency of pIC50 of 7.1. However, the higher basicity can also be responsible for off-target related complications such as hERG and Pgp-efflux liabilities; this is not always the case, and Pgp liability is not resultant on one factor and multiple properties of the molecule can affect this value. The measured pKa for compounds 13 (pKa = 10.3) and 21 (pKa = 9.0) was found to be higher than the optimal range. This high basicity could contribute to the high Pgp efflux observed for both compounds (13, AB+/AB– = 4.6 and 21, AB+/AB– = 5.3), but a clear outlier is compound 39 that has an ideal pKa and suffers from significant Pgp efflux. We did see in this series of compounds a clear correlation between hERG and pKa, with compound 13 with the highest pKa having a significant hERG liability and compound 43 not showing any hERG inhibition. Therefore, further work around these warhead modifications should aim at lowering the high pKa of the amidine function and modulating the vitro and vivo profile.

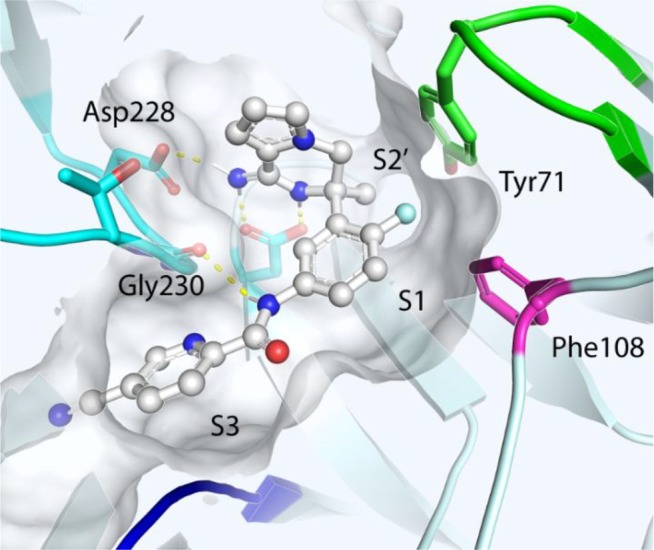

The crystal structure of 13 with BACE 1 was solved at 2 Å resolution (PDB code 6OD6, Figure 3). The result confirmed the binding mode to be similar to those seen for analogous amidine containing BACE 1 inhibitors.11,22 This includes the key interactions between the protonated amidine and the catalytic dyad (Asp32 and Asp228). The quaternary center is optimal for the orientation of the aryl ring and the methyl group, allowing the methyl to protrude into the S2′ pocket without clashing with the protein. The quaternary center favorably positions the F-aryl ring in an axial orientation to occupy the S1 pocket. The amide linker then optimally orientates the pyridine ring in the S3 pocket of BACE 1 while generating a favorable H-bond interaction with Gly230. Most of the compounds have a similar enzymatic activity with pIC50, approximately 8–8.5, with examples 17 and 39 showing the biggest difference: pIC50 7.54 and 8.70, respectively. Comparing pairs 13 and 17, 21 and 35, 26 and 30, and 39 and 43, all demonstrate that incorporation of a nitrogen at position 2′ led to a loss of activity. The crystal structure suggests that this nitrogen points toward the oxygen of Thr231 and is therefore electrostatically unfavorable, explaining the lower activity. The rest of the fused cycle is solvent exposed. Although not attempted here, additional substituents to the fused bicycle may allow further modulation of the potency by forming additional interactions with the receptor.

Figure 3.

Crystal structure of 13 in BACE 1 showing key interactions.

Compounds 17, 26, 30, 35, and 39 possess pKa values in an almost optimal range between 6.4 and 8.5 and show good to excellent intrinsic permeability. Unfortunately, despite their good pKa values, the Pgp-efflux liabilities measured for 35 (AB+/AB– = 4.8) and 39 (AB+/AB– = 9.8) precluded further investigation around these two chemotypes. On the other hand, compounds 17, 26, and 30 exhibited the desired in vitro profile combining potency, with good intrinsic permeability a reduced Pgp-efflux and hERG liability, and the heteroaryl-fused aminopiperazine warheads they represent have been selected for further profiling and optimization.

In summary, an efficient evaluation of multiple novel BACE 1 inhibitors has been achieved. Exploiting the reactivity of the cyclic sulfamidates, we have developed a convergent synthesis to explore the replacement of the aminopiperazinone warhead by bioisosteric replacements in the form of fused heteroaromatics. Several new series of BACE 1 inhibitors have been identified, and efforts are currently focused on the optimization of properties and progression of key compounds. These BACE 1 inhibitors represent a unique opportunity, as the fused 5-membered heterocyclic ring offers additional handles for modification to enhance their overall profile.

Acknowledgments

We thank the analytical departments in Beerse and Toledo for helping with compound characterization and purification and the DMPK and toxicology departments for their contributions in profiling the compounds. The authors would also like to thank Claudio Meyer for reviewing the manuscript.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00181.

Experimental procedures for synthesis, analytical characterization of all intermediates and final compounds (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hardy J. A.; Higgins G. A. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science 1992, 256, 184–185. 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S.; Anderson J. P.; Barbour R.; Basi G. S.; Caccavello R.; Davis D.; Doan M.; Dovey H. F.; Frigon N.; Hong J.; Jacobson-Croak K.; Jewett N.; Keim P.; Knops J.; Lieberburg I.; Power M.; Tan H.; Tatsuno G.; Tung J.; Schenk D.; Seubert P.; Suomensaari S. M.; Wang S.; Walker D.; Zhao J.; McConlogue L.; Varghese J. Purification and cloning of amyloid precursor protein beta-secretase from human brain. Nature 1999, 402, 537–540. 10.1038/990114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oehlrich D.; Prokopcova H.; Gijsen H. J. M. The evolution of amidine-based brain penetrant BACE 1 inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 2033–2045. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao C.-C.; Rombouts F.; Gijsen H. J. M. New evolutions in the BACE1 inhibitor field from 2014 to 2018. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 29, 761–777. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy and Safety Trial of Verubecestat (MK-8931) in Participants With Prodromal Alzheimer's Disease (MK-8931-019) (APECS). ClinicalTrials.gov; U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2013. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01953601.

- Study of LY2886721 in Mild Cognitive Impairment Due to Alzheimer's Disease or Mild Alzheimer's Disease. ClinicalTrials.gov; U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2012. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01561430.

- Baxter E. W.; Conway K. A.; Kennis L.; Bischoff F.; Mercken M. H.; De Winter H. L.; Reynolds C. H.; Tounge B. A.; Luo C.; Scott M. K.; Huang Y.; Braeken M.; Pieters S. M. A.; Berthelot D.; Masure S.; Bruinzeel W. D.; Jordan A. D.; Parker M. H.; Boyd R. E.; Qu J.; Alexander R. S.; Brenneman D. E.; Reitz A. E. 2-Amino-3,4-dihydroquinazolines as Inhibitors of BACE-1 (β-Site APP Cleaving Enzyme): Use of Structure Based Design to Convert a Micromolar Hit into a Nanomolar Lead. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 4261–4264. 10.1021/jm0705408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciordia M.; Perez-Benito L.; Delgado F.; Trabanco A.; Tresadern G. Application of Free Energy Perturbation for the Design of BACE1 Inhibitors. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2016, 56, 1856–1871. 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keranen H. K.; Perez-Benito L.; Ciordia M.; Delgado F.; Steinbrecher T. B.; Oehlrich D.; Van Vlijmen H. W. T.; Trabanco A.; Tresadern G. Acylguanidine Beta Secretase 1 Inhibitors: A Combined Experimental and Free Energy Perturbation Study. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2017, 13, 1439–1453. 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b01141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tresadern G.; Delgado F.; Delgado O.; Gijsen H.; Macdonald G. J.; Moechars D.; Rombouts F.; Alexander R.; Spurlino J.; Van Gool M.; Vega J. A.; Trabanco A. A. Rational design and synthesis of aminopiperazinones as β-secretase (BACE) inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 7255–7260. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rombouts F.; Tresadern G.; Delgado O.; Martínez-Lamenca C.; Van Gool M.; García-Molina A.; Alonso de Diego S.; Oehlrich D.; Prokopcova H.; Alonso J. A.; Austin N.; Borghys H.; Van Brandt S.; Surkyn M.; De Cleyn M.; Vos A.; Alexander R.; Macdonald R.; Moechars D.; Gijsen H.; Trabanco A. A. 1,4-Oxazine β-Secretase 1 (BACE 1) Inhibitors: From Hit Generation to Orally Bioavailable Brain Penetrant Leads. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 8216–8235. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijsen H.; Alonso de Diego S.; De Cleyn M.; García-Molina A.; Macdonald G. J.; Martínez-Lamenca C.; Oehlrich D.; Prokopcova H.; Rombouts F.; Surkyn M.; Trabanco A. A.; Van Brandt S.; Van den Bossche D.; Van Gool M.; Austin N.; Borghys H.; Dhuyvetter D.; Moechars D. Optimization of 1,4-oxazine β-secretase 1 (BACE 1) inhibitors toward a clinical candidate. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5292–5303. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower J. F.; Rujirawanich J.; Gallagher T. N-Heterocycle construction via cyclic sulfamidates: Applications in synthesis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010, 8, 1505–1519. 10.1039/b921842d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trabanco-Suarez A. A.; Delgado-Jimenez F.; Vega Ramiro J. A.; Tresadern G. J.; Gijsen H. J. M.; Oehlrich D.. Preparation of 5,6-dihydro-imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-8-ylamine derivatives as beta-secretase inhibitors. Patent WO2012085038, 2012.

- Kunishima M.; Kawachi C.; Monta J.; Terao K.; Iwasaki F.; Tani S. 4-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methyl-morpholinium chloride: an efficient condensing agent leading to the formation of amides and esters. Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 13159–13170. 10.1016/S0040-4020(99)00809-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trabanco-Suarez A. A.; Delgado-Jimenez F.. 3,4-Dihydro-pyrrolo[1,2-a]-1-ylamine derivatives useful as inhibitors of beta-secretase (BACE). Patent WO2012120023, 2012.

- Oehlrich D.; Gijsen H. J. M.; Surkyn M.. 4-Amino-6-phenyl-5,6-dihydroimidazo[1,5-A]pyrazine derivatives as inhibitors of beta-secretase (BACE). Patent WO2014198853, 2014.

- Trabanco-Suarez A. A.; Gijsen H. J. M.; Van Gool M. L. M.; Vega Ramiro J. A.; Delgado-Jimenez F.. Preparation of dihydropyrazolopyrazinylamine derivatives for use as beta-secretase inhibitors. Patent WO2012117027, 2012.

- Oehlrich D.; Gijsen H. J. M.. 4-Amino-6-phenyl-6,7-dihydro[1,2,3]triazolo[1,5,A]pyrazine derivatives as inhibitors of beta-secretase (BACE). Patent WO2014198854, 2014.

- Low J. D.; Bartberger M. D.; Chen K.; Cheng Y.; Fielden M. R.; Gore V.; Hickman D.; Liu Q.; Sickmier E. A.; Vargas H. W.; Werner J.; White R. D.; Wittington D. A.; Wood S.; Minatti A. E. Development of 2-aminooxazoline 3-azaxanthene β-amyloid cleaving enzyme (BACE) inhibitors with improved selectivity against Cathepsin D. MedChemComm 2017, 8, 1196–1206. 10.1039/C7MD00106A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huse J. T.; Pijak D. S.; Leslie G. J.; Lee V. M.; Doms R. W. Maturation and endosomal targeting of beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme. The Alzheimer’s disease beta-secretase. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 33729–33737. 10.1074/jbc.M004175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilpert H.; Guba W.; Woltering T. J.; Wostl W.; Pinard E.; Mauser H.; Mayweg A. V.; Rogers-Evans M.; Humm R.; Krummenacher D.; Muser T.; Schnider C.; Jacobsen H.; Ozmen L.; Bergadano A.; Banner D. W.; Hochstrasser R.; Kuglstatter A.; David-Pierson P.; Fischer H.; Polara A.; Narquizian R. β-Secretase (BACE 1) inhibitors with high in vivo efficacy suitable for clinical evaluation in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 3980–3995. 10.1021/jm400225m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.