Abstract

Background:

Patient/carer involvement in palliative care research has been reported as complex, difficult and less advanced compared to other areas of health and social care research. There is seemingly limited evidence on impact and effectiveness.

Aim:

To examine the evidence regarding patient/carer involvement in palliative care research and identify the facilitators, barriers, impacts and gaps in the evidence base.

Design:

Qualitative evidence synthesis using an integrative review approach and thematic analysis.

Data sources:

Electronic databases were searched up to March 2018. Additional methods included searching websites and ongoing/unpublished studies, author searching and contacting experts. Eligibility criteria were based on the SPICE (Setting, Perspective, Intervention, Comparison, Evaluation) framework. Two quality assessments on methodology and involvement were undertaken.

Results:

A total of 93 records were included. Eight main themes were identified, mainly concerning facilitators and barriers to effective patient and carer involvement in palliative care research: definitions/roles, values/principles, organisations/culture, training/support, networking/groups, perspectives/diversity, relationships/communication and emotions/impact. Evidence on the impact of involvement was limited, but when carried out effectively, involvement brought positive benefits for all concerned, improving the relevance and quality of research. Evidence gaps were found in non-cancer populations and collaborative/user-led involvement.

Conclusion:

Evidence identified suggests that involvement in palliative care research is challenging, but not dissimilar to that elsewhere. The facilitators and barriers identified relate mainly to the conduct of researchers at an individual level; in particular, there exists a reluctance among professionals to undertake involvement, and myths still perpetuate that patients/carers do not want to be involved. A developed infrastructure, more involvement-friendly organisational cultures and a strengthening of the evidence base would also be beneficial.

Keywords: Community participation, co-production, engagement, palliative care, patient and public involvement, research, systematic review, user involvement

What is already known about the topic?

Patient/carer involvement in palliative care research is reported as complex and challenging due to its association with end-of-life care and concerns for the vulnerability of patients/carers.

Involvement in palliative care research is less advanced than in other areas of health and social care research.

Limited evidence exists regarding the impact and effectiveness of involvement in palliative care research.

What this paper adds?

The findings show that involvement in palliative care research is challenging but not dissimilar to that in other fields. Issues concerning power, diversity and emotions are magnified, leading to a reluctance among researchers to undertake involvement.

Specific strategies are proposed to develop involvement concerning access, flexibility and the use of different involvement methods.

Patients/carers value opportunities to be involved in research, including from the outset of studies.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

Further exploration is needed of the highlighted issues to enable more collaborative, co-produced or user-led involvement.

The findings show a need for education, guidance or standards to improve involvement practice and organisational culture.

There is a need for further development of infrastructure to support involvement, including funding, training, support and networking opportunities.

Introduction

Public involvement in research is defined as research carried out ‘with’ or ‘by’ members of the public rather than ‘to’, ‘about’ or ‘for’ them.1 INVOLVE, funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) to support involvement within England, includes patients and carers within this definition; however, professionals, including academics and clinicians, although also users of health and social care services, are excluded because of their role and resulting different perspectives they bring. Patient/carer involvement may occur throughout the research cycle and could include, for example, taking an active role in setting priorities for research, commenting on study design as a member of an advisory group or carrying out interviews. Involvement has been shown to bring benefits such as making the research more relevant and improving its quality.1

Involvement has increased in priority both in the United Kingdom and internationally, notably the United States, Canada, Australia and Europe, and is now driven by both policy and research funders.1–3 However, in some areas of health and social care research, it is less well developed. This seems apparent in palliative care, where involvement has a shorter history compared to other disciplines and is said to be more complex and challenging for numerous reasons.4–7 Palliative care is associated with end-of-life care and there can be unease at discussing death and dying.8,9 Patients/carers often experience high levels of symptom burden or have limited time,8,9 and professionals may be reluctant to engage in research as it may feel too daunting or they may assume patients are too ill.10–12 Structures such as ethical review and governance arrangements may provide additional barriers.13,14

Little evidence exists on involvement in palliative care research compared to other fields.15 Available guidelines and standards are general and fail to provide detail on the particular issues associated with involving this population.1,2,16,17 There is limited literature on involvement in other palliative care settings, for example, education18–20 or service provision.21–25 The need for this review is therefore apparent, to promote more effective involvement in palliative care research, for the benefit of all, including clinicians, academics and patients/carers.26–29

Aims

The primary aim was to systematically review the evidence regarding patient/carer involvement in palliative care research. The secondary aim was to identify facilitators, barriers and gaps in the evidence base.

Methods

A preliminary scoping review was undertaken to identify issues related to the definition of palliative care, the population, evidence type and study design; and used to define the eligibility criteria, search terms and search strategy for the subsequent review.

Subsequently, a qualitative evidence synthesis was used to enable diverse evidence to be incorporated and different perspectives and contextual factors to be considered.30 An integrative approach brought together different types of data in terms of both study design and involvement approach.31 The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines were followed.32

Eligibility criteria

The SPICE framework (Setting, Perspective, Intervention, Comparison, Evaluation)33 was used to define the eligibility criteria, with additional criteria identified from the scoping review (Table 1).

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria.

| Selection criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Setting | Palliative carea research Palliative care in other settings (e.g. education, service provision) if it relates to involvement at a higher level than the individual patient/carer, includes guidelines or standards, or is a key text of relevance to the review |

Other areas of research Palliative care in service provision at individual level with no involvement No guidelines or standards |

| Perspective | Anyone with experience of patient/carer involvement in palliative care research (e.g. patients, carers, clinicians, academics) | No experience of patient/carer involvement in palliative care research |

| Intervention | Involvement | No involvement |

| Comparison | Not relevant | Not relevant |

| Evaluation | Any evidence on the effects of involvement, either on outcome or process (e.g. impact, benefits, barriers) | None |

| Age | Aged 18 years and older | Aged under 18 years |

| Countries | Evidence concerning Western populations only | Non-Western populations |

| Language | English only | Non-English |

| Type of evidence | Any evidence or literature, including grey literature | None |

| Study/evidence design | Any design, including reviews, qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods, text or opinion | None |

| Publication year | Any year | None |

WHO: World Health Organisation; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MND: motor neuron disease.

Palliative care defined broadly using the Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life,34 which widened the WHO definition35 to make it more comprehensive. Search terms related to palliative care expanded to include non-communicable life-limiting health conditions most relevant to Western countries34 and to ensure a diverse range of conditions to enable different involvement issues to be explored. The following were used: Alzheimer’s and other dementias, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, chronic respiratory conditions (e.g. COPD), diabetes and neurodegenerative conditions (e.g. Huntington’s, MND, Parkinson’s). Those aged under 18 were excluded because of the additional ethical and other issues raised.

Information sources and search

The scoping review identified a scarcity of published academic literature and a larger quantity of diverse grey evidence, suggesting the need to use a wide variety of search methods.

Health databases (AMED, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, PsycINFO), social science and other databases (ASSIA, EThOS, Social Care Online, Open Grey, ProQuest, Web of Science) were searched. Websites of general health organisations (e.g. Joseph Rowntree Foundation), involvement-specific organisations (e.g. James Lind Alliance) and palliative care organisations in the United Kingdom and internationally (e.g. National Council for Palliative Care (NCPC), European Association for Palliative Care) were hand-searched. The INVOLVE website was searched for ongoing and unpublished research studies.

Bibliographies of key texts were checked to identify missing evidence and author searching was undertaken. Individual experts and specialist organisations were contacted, including academics, clinicians and patients/carers, notably a patient/carer involvement panel, Sheffield Palliative Care Studies Advisory Group (PCSAG).36 All searches were conducted between July and December 2017, with an additional search in April 2019.

Components of the SPICE framework were combined and used to define the search strategies. Multiple terms were identified for each component and combined using Boolean operators. Free text searching was used to search databases and websites using these terms. Some databases use MeSH terms; therefore, thesaurus searching was used in addition. Where possible, limit functions were used to limit searches, for example, to English language. Similarly, filters were applied to restrict searches, for example, to adult populations only (Table 2).

Table 2.

Search strategies.

| SPICE components | Thesaurus terms | Free text terms |

|---|---|---|

| Setting | ((Palliative care OR Palliative medicine OR Hospice care OR Terminally ill OR Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing OR Hospices) OR (Alzheimer Disease OR Dementia) OR (Cancer OR Neoplasms) OR (Cardiovascular diseases) OR (Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive) OR (Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults) OR (Neurodegenerative Diseases OR Motor Neuron Disease OR Huntington Disease OR Parkinson Disease, Postencephalitic)) AND (research* OR study OR trial OR interview* OR project OR review) |

((Palliative care OR Palliative medicine OR Hospice care OR Terminally ill OR Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing OR Hospices OR End of life care OR Terminal Care OR Supportive Care OR Non-curative Therapy OR Palliative Treatment) OR (Alzheimer’s OR Dementia) OR (Cancer OR Neoplasms) OR (Cardiovascular disease OR CVD) OR (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease OR COPD) OR (Diabetes) OR (Neurodegenerative Disease OR Motor Neuron Disease OR MND OR Huntington Disease Huntington’s OR Parkinson’s Disease)) AND (research* OR study OR trial OR interview* OR project OR review) |

| Perspective | Not relevant | Not relevant |

| Intervention | Community Participation OR Patient Participation | Involv* OR Engag* OR Participat* OR Co-produc* OR Collaborat* OR Partnership working OR Participatory Research OR Participatory Action Research OR Emancipatory Research OR Expert Patient OR Experts by Experience OR Research Partner |

| Comparison | Not relevant | Not relevant |

| Evaluation | Not relevant | Not relevant |

SPICE: Setting, Perspective, Intervention, Comparison, Evaluation.

Evidence selection

All retrieved evidence was screened for relevance using the eligibility criteria. Titles and abstracts of studies (or summaries in the case of grey literature) were screened together initially and the same process repeated with the full texts. Reasons for exclusion were recorded for transparency. All references were entered into EndNote.

Data collection process

A data extraction form was developed, piloted on a sample of diverse evidence and adapted to ensure the optimum extraction of relevant data. Data were extracted on key characteristics pertaining to both type of evidence and involvement.

Quality assessment

Two quality assessments were undertaken, concurrently with data extraction. The first related to the methodological quality of the study or evidence and used the relevant critical appraisal tool from the Joanna Briggs Institute.37 The second used critical appraisal guidelines developed specifically for appraising the quality of involvement in research.38 No evidence was excluded on the basis of quality, instead both checklists were used to provide a rating based on broad categories only (weak, moderate, strong), as has been found useful in other reviews.39,40

Independent verification

Evidence selection, data extraction and quality assessment were carried out by the lead author with contributions from all other authors. A sample of evidence was randomly selected and double-checked by the other authors and comprised a full screening process using the eligibility criteria and completion of both quality assessments. Findings were compared and any differences resolved through discussion. Agreement was achieved on eligibility of evidence and broad rating categories for both quality assessments.

Synthesis of results

Thematic synthesis was used because the review questions were fixed and there was a large amount of evidence.30,41 In addition, thematic synthesis has been effectively used in similar reviews that explored people’s perceptions, including the identification of barriers and facilitators.31,42

Synthesis involved several stages: data from each piece of evidence were extracted verbatim into tables and coded initially line-by-line, codes were combined to generate descriptive themes, and finally analytical themes were developed.41 An a priori framework was not used for initial coding but was developed from the codes iteratively during the first two stages, as further evidence was individually coded.

Patient and carer involvement in this review

The involvement of patients/carers in systematic reviews is still scarce, although it has been increasing in recent years.43–45 Patients/carers were involved at several key stages. Initially, consultation was undertaken with a group of patients/carers, including members of the PCSAG on the identification of sources to be searched, search terms and the inclusion of different health conditions.

A further wider consultation took place with patients/carers after the identification of the analytical themes, for validation purposes. Patients/carers described experiences and perspectives that resonated with the themes produced. They provided examples from their own involvement activities and highlighted particular areas they believed to be of importance. Additional issues were raised that had not previously been identified by the review (Supplemental material: File 1. Patient/carer involvement). Patients/carers were offered gift vouchers as an appreciation of thanks.

Results

Evidence selection and characteristics

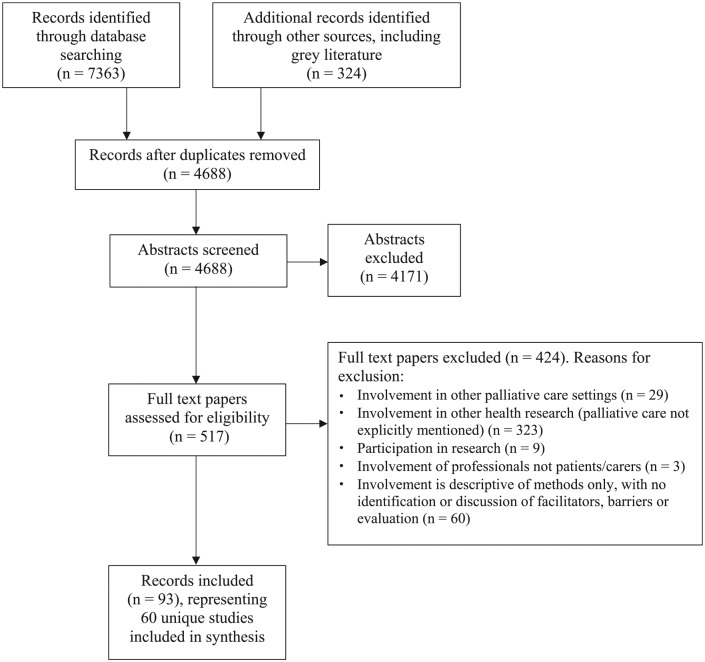

The searches identified 4688 potentially relevant records after duplicates were removed, resulting in 93 included records after screening. Reasons for exclusion are shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). Included evidence and characteristics are provided (Supplemental materials: File 2. Included evidence, File 3. Evidence characteristics).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.32

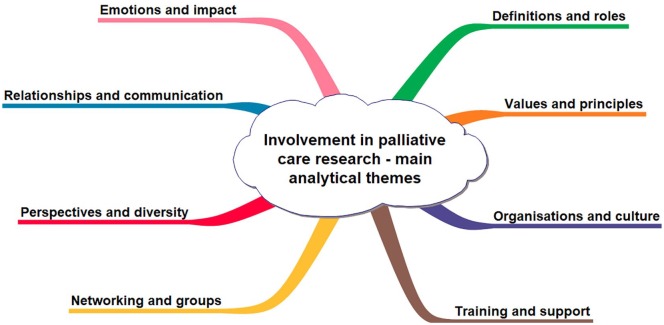

Thematic findings

Eight main analytical themes were identified, which mainly described facilitators and barriers to effective patient and carer involvement in palliative care research: definitions and roles, values and principles, organisations and culture, training and support, networking and groups, perspectives and diversity, relationships and communication, and emotions and impact (Figure 2). A summary table of the findings is provided (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Main analytical themes.

Table 3.

Summary of results.

| Main analytical theme | Summary of key issues/learning |

|---|---|

| Definitions and roles | • Difficulties in conceptualising involvement and palliative care due to use of different terminology

• Take time to clarify roles, purpose and expectations • Take time to create a safe space and to work together collaboratively, acknowledging boundary issues |

| Values and principles | • Similarity of values in involvement and palliative care

• Acknowledge difficulties; however, do not make assumptions • Acknowledge and work with power issues |

| Organisations and culture | • Consider involvement as a core activity, integrate throughout organisations

• Address practical matters to make systems more involvement-friendly • Address issues concerning attitudes to involvement and emotional aspects • Involvement found to be less daunting than originally thought |

| Training and support | • Provide training opportunities for all, considering different motivations

• Address support issues • Involve different people using different methods |

| Networking and groups | • Develop infrastructure to enable networking and mutual support, build collaborations and develop new groups

• Take time to develop relationships • Consider issues concerning sustainability of groups |

| Perspectives and diversity | • View differing perspectives as all valuable

• Acknowledge and address issues concerning diversity • Consider diversity rather than representativeness |

| Relationships and communication | Take time to develop relationships

• Need for professionals to interact with patients/carers • Ensure communication is accessible and regular, provide feedback • Acknowledge value and benefits of involvement |

| Emotions and impact | • Acknowledge and address issues concerning emotional impact

• Ensure good practice followed in involvement • Acknowledge positive benefits and impacts • Ensure patients/carers offered opportunities to be involved |

Definitions and roles

Different terminology was used for those involved, for example, ‘lay stakeholders’,46 ‘research partners’47 and ‘service users’.48 No one definition was applicable across all evidence and it was unclear whether interpretations of involvement were uniform.49,50 Similarly, the term palliative care was inconsistently used, with variations in health condition, including symptoms and stages25,51,52; service use, for example, specialist or generalist services12,50,53,54; and inconsistencies concerning how end-of-life was defined, boundaries between different types of care and the length of time a person was considered to be in need of palliative care.12,21,55,56 The discrepancies made it hard to conceptualise both involvement and palliative care.

The need for greater clarity of involvement roles was highlighted, particularly at the outset of studies when patients were unclear what was expected from them.6,28,57 Evidence related to groups emphasised the need for a clear purpose.5,58 Initial expectations of what a group could achieve were vague, roles uncertain and relationships with external bodies such as research networks confused.5,49 Researchers needed to take time to facilitate a safe space, explain the research and clarify roles and expectations.

It could take groups a year before they started to engage meaningfully with researchers – time was needed to learn the system and how to affect change.59 This slowness was frustrating for some but valuable to develop aims and working practices.50,60,61 The need for agreement by everyone was stressed and the importance of negotiating this throughout the study was described to enable ownership of the group. It was recommended that possible emotional impacts of involvement were discussed from the outset, including stressing that people need only share aspects of their personal experiences that they feel comfortable with.62

Boundaries between patients/carers and professionals were sometimes challenged as many people were in fact juggling several different roles.63,64 Researchers had to decide how much of their own personal experiences to reveal.65 One described a merging between his professional and personal roles; he found himself becoming friendlier with members of the patient group and felt his professional identity was being challenged, as he shifted from being paternalistic to a more equal position.66

Values and principles

The values implicit within involvement were described as similar to those in palliative care,49,67 and included transparency, accountability and honesty, for example, the importance of congruency between real and stated aims.61,62 Respect, trust and listening were necessary to develop collaborative relationships between patients and researchers.7,61,67 Flexibility enabled people to decide when and how to be involved – important for carers who had responsibilities and patients, whose health condition may fluctuate or progress.68

Particular approaches, notably Participatory Action Research, Community Based Participatory Research and emancipatory research, were suggested as being effective in promoting involvement.69–72 These approaches used principles of equity, power-sharing and reciprocal transfer of knowledge and skills.49,55,73 However, the evidence was limited because they had not been widely or comprehensively used.55,69

Power was a recurrent theme, significantly the need to avoid tokenism or tick-box involvement. Sometimes roles were limited, patients had a voice but little authority for decision-making,50,51,74 or involvement was used to meet the organisation’s agenda rather than that of patients.71,75 Furthermore, involvement had the potential to be exploitative – thought to be important due to the potential vulnerability of patients/carers.12,21,67,75 Even when partic-ipatory methods were used, inequalities of power and influence were reported, the experiential knowledge of patients/carers could be overshadowed by academics’ research knowledge, and the drive for research usually came from academics.63,70,71,76 The importance of bridging different world views was highlighted.72 Sometimes patients felt obliged to take part in involvement or were concerned about possible repercussions to their care if they expressed negative opinions. The ‘grateful patient syndrome’ was mentioned, where people at a difficult time in their life may be overly positive77 and older people were less likely to be negative.25

Patients/carers were often experiencing massive change and had fears for the future. Some had little time, non-essential commitments may be rejected or people may be pre-occupied with other things. Patients may be feeling unwell or experiencing fatigue, some had highly symptomatic conditions, a short disease duration, poor prognosis or may be facing death. Carers were facing bereavement, coping with loss or the prospect of loneliness.12,21,66,74,78,79 Therefore, many professionals were concerned about overburdening people or felt it inappropriate to contact patients as they may die before seeing any changes resulting from their involvement.21,49,51,80 Gatekeeping by clinicians could also be a barrier,50,56,69,71,81 for example, a hospice refused to allow patients to be involved until their own Ethics Committee had cleared the study.77 The ethical concerns of involvement needed to be balanced with not making assumptions or removing choices from people.21,56,66,67

Organisations and culture

Involvement was influenced by wide contextual factors including international perspectives and local politics46,51; however, organisational culture was also highly significant.4,50,67,82 Involvement needed to be considered a core activity, integrated throughout organisations at different levels5,49,56,83; however, systems often were not perceived as being involvement-friendly. Competing considerations existed; pressures on staff, heavy workloads and cutbacks in the context of austerity all made involvement difficult.4,51,60,84 Practical matters of administration, finances and travel needed to be addressed to avoid complicated bureaucratic practices.65,84

Despite this, there was much commitment and support shown from professionals,4,51,57,59,64,77,84,85 including, importantly, those in senior positions.4,50,86 Conversely, professionals were also reported as being disinterested, dismissive or displaying a lack of understanding of involvement.5,58,60,67 Some were described as fearful or uncomfortable; they felt involvement was too impractical or unrealistic.51,74 The representativeness of patients was questioned; some patients were thought to have their own personal agendas.82 People were labelled as ‘the usual suspects’, causing annoyance and offence.5,57 Sometimes patients were considered to be too close to their diagnosis; at other times, professionals felt their treatment occurred too long ago.87 There were concerns that people were not competent, that they would not consider legal, funding or other organisational constraints.65 These issues were poorly addressed, preventing patients from expressing their views.49

Nevertheless, there were encouraging progressions over time.59,70,88 In evaluations, clinicians reported more positive views about involvement activities, which were previously small scale but now more sophisticated, focussing on larger service development issues.50,51,84 Researchers increased their understanding of and commitment to involvement, and there was a shift in ideology away from paternalistic or superficial approaches. Professionals were surprised that patients raised issues that were small and achievable rather than large issues which required resources. They realised patients’ views were not as challenging as anticipated and involvement not as daunting as first believed, thereby also increasing their confidence.6,51,74

Training and support

Ongoing training and support were recommended for all, including professionals.7,50,56,58,67 Some organisations had developed specific programmes, providing induction, training and scientific mentoring.6,49 Training on involvement, funding, organisational structures, team building and research methods was provided.60,86 Patients/carers appreciated being able to keep up to date with current knowledge and research.89 Involvement from the outset was important, to enable appropriate training and support to be developed in partnership with patients/carers.7,54,76 The different motivations for wanting to be involved needed to be addressed, including poor or excellent treatment, wanting to give back, training opportunities and notably a desire to influence and improve both research and service provision.5,87

However, numerous practical constraints were reported, including meeting times or the use of venues such as hospitals which may hold unpleasant memories.51 Involvement needed to allow people to engage with ease, therefore meetings needed to accommodate those who may be ill, experiencing pain or discomfort, have limited energy or a limited attention span.8,90,91 Informality was important, so people could move around or take medication.62,66 Meetings/training should not last too long, breaks were useful and presentations should be kept short.49,89,92

Flexibility and accessibility were required as people sometimes could not commit regularly or long term.28,50,73,89 Sometimes one involvement method was used initially, for example, an advisory group, but then, if people became unwell, email communication was preferred.28 Initiatives such as keeping reflexive diaries and using de-brief time after events were recommended, if people did not want or were unable to participate in groups.65,68,74,77 Other support mechanisms included peer mentoring or attending events with family/friends.49,51,58,93 Advocacy may be helpful, so patients could speak on behalf of others who may be too unwell.50

Not every involvement method was suitable for everyone, each brought advantages and disadvantages. The use of several methods, adapted to suit different communities, was useful to enable a range of people to be involved.6,28,56,65,67 Methods included newsletters, website stories, talks at organisations and other outreach methods, telephone and email.68 Developments in IT had made virtual interaction more feasible, therefore not requiring physical presence at meetings – online training, video conferencing and online communities were all suggested.8,47,49 One study had developed an online involvement forum.6,94

Networking and groups

A centralised networking resource for professionals and patients/carers was suggested, to provide co-ordination, reduce duplication, and share information and learning. Professionals highlighted the importance of building alliances and linking to local organisations, for example, patient forums.28,50,51,82 Patients wanted assistance with developing new groups, particularly patient-led organisations, and gaining mutual support.5,25,28,84

Patient/carer advisory groups were common involvement methods,62,70,71,74,77,95 with members often also active elsewhere, for example, involved in service provision.82,83 There were particular challenges regarding the stability of patient groups, including a lack of funding.58,80 Clinicians could help establish and publicise groups, and provide ongoing support, for example, free meeting space.25 However, it was important for professionals to facilitate group collaboration, not discriminate between patient groups, and to step back to allow patients to implement their own agendas.25

Some people were initially anxious on joining a group; it took time for relationships to develop and members to feel comfortable. Several groups showed an element of peer support – not the intended purpose but often needed due to the nature of palliative care.5,25 However, it was difficult to sustain the long-term survival of groups and the loss of influential members caused groups to destabilise.25,87 There was a need for continuous recruitment and succession planning.50,58

Tensions were reported when individuals dominated discussions. Often conflicts were self-managed, but it was important to give time to these process issues.25,58,62,86 Facilitation was sometimes demanding because when people spoke of their personal experiences, it could be hard to move the conversation on.7,92 The composition of groups was discussed. Mixed panels of professionals and patients provided better networking opportunities but could be harder to facilitate to enable patients to have a meaningful contribution.60,86 It may be helpful if patients outnumbered professionals85 or if the chair was a patient/carer.51,82 Some groups aimed to be more participatory in approach but this was unusual and required increased resources.48,67,80,96

An evolutionary process of group development over time was reported, as knowledge, expertise and confidence grew.6,50,59,60,83 Initially group members were engaged mainly in consultations, for example, reviewing patient information. They then undertook more collaborative involvement, such as becoming peer researchers or co-applicants on funding bids.65,74,84,96–98 As groups gained experience, they established more influential relationships with professionals, took more pro-active roles in decision-making, and contributed to policy and development.4,49,59,60,82,96 Some also started thinking about their own research ideas as patient-led projects.47,99

Perspectives and diversity

Differences in perspectives were common, mainly between patients/carers and the dominant perspective, professionals.28,46,51,84,92,100 There was a need to make the patient/carer voice more visible throughout, including in dissemination.28,50,61,71,75,83 It may be helpful to view differing perspectives as not in competition, but as different opinions that all needed to be understood to reach a solution.65 For example, in studies where patients undertook data analysis, different themes were identified from that of researchers alone.76,80,93,101

Perspectives were particularly relevant for research that used Nominal Group Techniques, including Priority Setting Partnerships (PSPs) or similar,28,61,68,79,90,91,102–104 or Delphi studies.105,106 PSPs were often driven by clinicians suggesting a need for greater involvement, to enable patient/carer priorities to be included rather than merely validating those identified by professionals.75,103,106 Facilitators of groups/workshops needed to ensure that no stakeholder groups dominated or were excluded. For example, there may be conflicts between patients and carers.12,61,77

Greater diversity in involvement increased the credibility of research findings and/or obtained more relevant priorities; however, difficulties were often reported.7,56,103 The exclusion of some groups – people from Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) backgrounds, those on a lower income or with a non-cancer condition – reflected their exclusion in palliative care service provision.49,77 For others, older people or those in rural communities, practical considerations of transport and access were exacerbated.6,12,107 Younger people and those with rare conditions could also be excluded,62,96 and some people were self-conscious or reluctant to mix with others, for example, people with laryngectomies.25 The exclusion of those at the end of life was also highlighted,12,99 although one PSP had focussed solely on this group90,108 – other PSPs used weighting mechanisms to ensure patient priorities were reflected.79,103 Recruitment from marginalised communities required greater resources and different approaches, for example, outreach methods or regional recruitment for those with rarer conditions.7,25,49

Several papers commented that the ‘right type’ of patient seemed to be, for example, in better health, English speaking, had access to IT and available in the daytime!62,87 Such patients could be recruited to the exclusion of others as they were more accessible to professionals, sometimes hand-picked with no open recruitment processes.49,87 Often recruitment was solely from existing patient/carer groups, thereby creating further exclusion as most people are not a member of any group.12,25,49,75 Groups served some conditions better than others – some had no or few groups, in particular, rarer conditions.25,96,102

The word ‘representative’ caused difficulties; aiming for diversity rather than representativeness was recommended.21,65,75,82 Demographic factors and health conditions could be used for recruitment, along with those with different experiences and attitudes, for example, ‘patients who volunteer, enthusiastic patients, hard to reach patients, alienated and sceptical patients, isolated patients, patients who are very ill, carers, family members and friends’.21

Relationships and communication

It was important for professionals to develop collaborative relationships, have ongoing conversations and establish a two-way dialogue – not just email asking for comments.84,93,97 Sometimes it was difficult to build relationships6,94 or it took longer as communities became involved in their own ways, in their own time.57,69,72 There was sometimes mutual suspicion between patients/carers and professionals with a resulting need to develop a common agenda and work towards unified goals.25 Participatory approaches were suggested, whereby different groups can come together to co-develop a vision for research.72 A willingness to remain open, listen, revise expectations and try new things all helped.87 It was suggested the best way for professionals to learn was to interact with people with life-limiting conditions or experiencing bereavement. The ability to listen to ‘awful stories’ was thought to be valuable.50

Communication needed to be accessible, as complicated technical language and jargon could alienate some people.6,7,50,66,91,109 Researchers were able to communicate regularly with academic colleagues; however, this was not possible with patients/carers. Lack of feedback was therefore sometimes an issue, resulting in patients feeling frustrated with not knowing what had happened to their views or if any action had resulted.28,56,57,65,68 It was important to keep patients/carers regularly updated, for example, via newsletters.77,80 Emerging findings could also be provided in case patients/carers were unable to receive final study results.49,89

Relationships formed or were strengthened, teamwork was developed and barriers broken down.50 There was increased dialogue and communication, contributing to organisational change. Boundaries were positively blurred between patients/carers and professionals, as involvement began to be perceived as a joint process with shared responsibilities.51,97,98 Throughout studies, patients/carers challenged assumptions, asked questions and influenced professional complacency. They brought common-sense to meetings and kept discussions grounded in reality.50,74,80,92,110

Emotions and impact

Involvement in palliative care could have a profound effect and high emotional cost. Sometimes it affirmed people’s experiences of disrespectful services or brought back memories of loved ones who had since died.5,28,62,74 The ill-health and death of fellow group members or participants caused distress.63,66,74,109 One paper reported that ‘people shed tears at every event’.63 Sometimes patients/carers had to withdraw from involvement as a result.21,109 Conversely, few professionals described any such emotional attachment.82

Involvement itself also caused distress, as activities could be carried out poorly, for example, it could be disempowering to sit on an intimidating committee.25,58,75,77 Sometimes patients experienced unrealistic expectations from professionals regarding their health or available time.49,71 People could feel overwhelmed by the pressures of involvement, issues connected with power imbalances or upsetting attitudes of professionals, for example, when health conditions were discussed insensitively.5,57

However, many more positive impacts were reported. Patients commonly described involvement as giving them a focus, motivating them to carry on in life.5 Coming together in groups was reassuring and confidence boosting; being with others with the same health condition could be beneficial and some were seen as role models.5,50,98 Other social benefits included networking, making friends and gaining mutual support. Working together, including with professionals, brought a sense of solidarity and comradery.57,66,80 Patients/carers increased their knowledge of research and ethical issues.28,57 Researchers gained a greater understanding of palliative care, the experiences of the communities they were working with and what it was like living with particular health conditions.46,72,74

Patients found that involvement improved their relationship with their illness, helping them to come to terms with it. They learnt more about themselves, their health condition and how to better live with it.57,109 It gave them a sense that something positive had come out of the sometimes negative experiences of diagnosis and treatment and helped to dispel feelings of hopelessness. Some commented that involvement had enabled them to think more about palliative care and to take responsibility for planning their own death.5,50,57,66 Carers too found that being involved eased difficult feelings regarding their experiences.111

Other psychological benefits included increased self-confidence and feelings of empowerment. Involvement was seen as a positive way to keep active and combat depression and loneliness. A sense of personal achievement was gained and people felt recognised and valued for their contribution.5,57,83 Their expertise in their own condition was acknowledged but they were not just being defined as a patient, they felt helpful and able to do something again. Sometimes, people went on to be involved in further research, study or other activities.66,85,110

Despite the challenges, patients/carers were still keen to be involved and reported strong emotional attachments to involvement.22,48,82,87 Members of one group described how they had not considered giving up, despite the fact that several members had died. They described their involvement as ‘fun’.5

Discussion

This is the first study to systematically review patient and carer involvement in palliative care research. Eight main themes were found: definitions and roles, values and principles, organisations and culture, training and support, networking and groups, perspectives and diversity, relationships and communication, and emotions and impact. These are consistent with themes found elsewhere on involvement in health and social care research, both in the United Kingdom and internationally.112–115

The evidence identified, although considerable, was predominantly qualitative or text/opinion in design, from the United Kingdom and concerned cancer. Furthermore, the quantity of publications has not increased significantly over recent years. The majority of involvement methods identified were consultative. Some more collaborative or co-produced initiatives were found, although collaboration featured as an element only in these. No studies were user-led or user-controlled.1,116 These limitations in the evidence base illustrate the slow progression and particular difficulties associated with involvement in this field, when compared to mental health or disability research, for example.3,117,118

The evidence was largely comprised of facilitators and barriers, with limited evidence of impacts identified. Several prominent themes were highlighted. As in other fields, power was significant, influencing involvement throughout the research cycle.2,114 However, the range of issues reported from differing perspectives suggests there is a greater power imbalance between patients/carers and professionals than in other fields, and a resulting magnification of the complexities. The perceived vulnerability of patients/carers by professionals was frequently cited as a barrier, supporting existing evidence from other disciplines.119,120 Furthermore, myths still perpetuate that patients/carers do not want to or are unable to take part in palliative care research as participants, let alone undertake involvement.56,121,122 This review challenges such assumptions as being paternalistic and increasing marginalisation and exclusion. Both the review and consultation show that patients/carers value involvement opportunities, and moreover, from the outset, to enable them to input into their role and the involvement methods used.

Diversity was a further important theme, again reflected elsewhere.119,123 The lack of diversity found among those involved was shown to reflect many of the inequalities found in the wider context of palliative care service provision, where some communities receive limited palliative care services or a poorer quality of care, including patients with non-cancer conditions, people from BAME backgrounds, older people and those living in deprived areas.124–126 To increase diversity, there needs to be greater emphasis on the process of involvement, to address issues such as access and flexibility, using a variety of involvement methods, adapting or changing them over time. The evidence base for this is gradually developing, with studies in palliative care and other fields beginning to use more innovative approaches.6,56,127–129

A contrast was illustrated of how emotions were addressed from different perspectives. Patients/carers were open in relaying both the positive impacts and often complex profound sentiments concerning their involvement, whereas few professionals reported emotional impacts, usually keeping any personal experiences of palliative care hidden.63,65,82 Exceptions to this were studies that used more participatory approaches, in which professionals were less reserved, acknowledged their multiple or changing roles, and where a blurring of boundaries between patients/carers and professionals was found to be helpful to the involvement process.51,63,65,66,77

Finally, although the limited evidence found on impact is in line with reporting of involvement elsewhere,7,114,130,131 it is apparent that when involvement was carried out effectively, there were positive benefits for all concerned, patients/carers, clinicians and researchers, in addition to improving the relevance and quality of the research.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength is the comprehensive search and broad inclusion criteria, resulting in the identification of a significant amount of diverse evidence. It is possible the evidence is not reflective of all involvement as only published involvement initiatives were reviewed; however, saturation became apparent as new records did not identify new themes.132

The quality of evidence was variable in terms of both methodology and involvement; however, all available evidence was used in order to maximise understanding. The exclusion of evidence pertaining to those under 18 or non-Western populations may have resulted in some omissions; however, palliative care services and involvement practices were considered to be incomparable between these populations. The integrative approach enabled all evidence to be brought together. Thematic synthesis allowed both different perspectives and contexts to be explored.

The involvement of patients/carers at several key stages widened the search terms and sources searched, identifying grey literature in particular, thereby increasing the comprehensiveness. Later, patients and carers not only validated themes but also provided additional data not found in the review. Increased collaboration may have further strengthened the review.

Unclear definitions of both involvement and palliative care were evident throughout. This could be seen as a limitation; however, it is believed that the evidence still provides beneficial data and moreover simply reflects the blurred boundaries and intricacies often present in both involvement and palliative care.133–136

Implications for future research and development

The limited evidence base, in particular the lack of rigorous evidence on the impact and effectiveness of involvement, suggests the need for further research in areas not previously evaluated, notably non-cancer conditions and more collaborative, co-produced or user-led research. Prominent themes of power, diversity and emotions could be explored further, including the apparent reluctance of professionals to undertake involvement. Although involvement was shown to have developed over time, as elsewhere,137–139 there is a need for education or guidance to improve both improvement practice and organisational culture.

Few organisations exist that specifically support involvement in palliative care research. Patient/carer groups encounter difficulties in establishing and sustaining themselves.85,140 Palliative care organisations tend to focus on service provision,141,142 or have not yet explored involvement in research,143,144 and involvement-specific organisations have seldom considered the additional complexities inherent in palliative care research.145,146 Evidence is rarely shared between organisations and involvement practices in other settings, notably service provision and education, are rarely shared. There is therefore a need for further development of infrastructure to support involvement, including funding, training, support and networking opportunities.

Conclusion

This review is the first to synthesise evidence related to involvement in palliative care research and has identified significant themes which need to be addressed to further the development of involvement in this field. Given the increase in the older population and resulting need for palliative care services, this is a growing topical concern.147

This review suggests that at present many professionals feel reluctant or unable to undertake patient and carer involvement in a palliative care research context. Increased education or guidance, the development of infrastructure, more involvement-friendly organisational cultures and a strengthening of the evidence base would enable more effective involvement in palliative care research, thereby improving both research and service provision.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, 858247_File_1,_Patient_and_carer_involvement for Patient and carer involvement in palliative care research: An integrative qualitative evidence synthesis review by Eleni Chambers, Clare Gardiner, Jill Thompson and Jane Seymour in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, 858247_File_2,_Included_evidence for Patient and carer involvement in palliative care research: An integrative qualitative evidence synthesis review by Eleni Chambers, Clare Gardiner, Jill Thompson and Jane Seymour in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, 858247_File_3,_Evidence_characteristics for Patient and carer involvement in palliative care research: An integrative qualitative evidence synthesis review by Eleni Chambers, Clare Gardiner, Jill Thompson and Jane Seymour in Palliative Medicine

Acknowledgments

We thank the experts and organisations who provided assistance with identifying evidence, in particular, members of the Palliative Care Studies Advisory Group and other patients/carers who were involved in the study.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by a Doctoral Academy Scholarship awarded to Eleni Chambers jointly from the School of Nursing & Midwifery and the Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry & Health, University of Sheffield.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iDs: Eleni Chambers  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6017-2750

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6017-2750

Clare Gardiner  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1785-7054

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1785-7054

References

- 1. INVOLVE. Briefing notes for researchers: involving the public in NHS, public health and social care research. Southampton: National Institute for Health Research, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wicks P, Richards T, Denegri S, et al. Patients’ roles and rights in research. BMJ 2018; 362: k3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Breaking Boundaries Review Team. Going the extra mile: improving the nation’s health and wellbeing through public involvement in research. London: National Institute for Health Research, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Croft S, Chowns G, Beresford P. Getting it right: end of life care and user involvement in palliative care social work. London: Association of Palliative Care Social Workers, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cotterell P, Harlow G, Morris C, et al. Service user involvement in cancer care: the impact on service users. Health Expect 2010; 14: 159–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brighton LJ, Pask S, Benalia H, et al. Taking patient and public involvement online: qualitative evaluation of an online forum for palliative care and rehabilitation research. Res Involv Engagem 2018; 4: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pii KH, Schou LH, Piil K, et al. Current trends in patient and public involvement in cancer research: a systematic review. Health Expect 2019; 22(1): 3–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Black J. User involvement in EoLC: how involved can patients/carers be? End Life Care 2008; 2: 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen EK, Riffin C, Reid MC, et al. Why is high-quality research on palliative care so hard to do? Barriers to improved research from a survey of palliative care researchers. J Palliat Med 2014; 17(7): 782–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Payne S, Seymour J, Molassiotis A, et al. Benefits and challenges of collaborative research: lessons from supportive and palliative care. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2011; 1(1): 5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gysels M, Evans CJ, Lewis P, et al. MORECare research methods guidance development: recommendations for ethical issues in palliative and end-of-life care research. Palliat Med 2013; 27(10): 908–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Small N, Rhodes P. Too ill to talk? User involvement and palliative care. London: Routledge, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Higginson IJ, Evans CJ, Grande G, et al. Evaluating complex interventions in end of life care: the MORECare statement on good practice generated by a synthesis of transparent expert consultations and systematic reviews. BMC Med 2013; 11: 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bellamy G, Gott M, Frey R. ‘It’s my pleasure?’ The views of palliative care patients about being asked to participate in research. Prog Palliat Care 2011; 19: 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- 15. INVOLVE. Evidence bibliography 5: references on public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research. Eastleigh: INVOLVE, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16. INVOLVE. Public involvement in research: values and principles framework. Eastleigh: INVOLVE, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chief Scientist Office, Health and Care Research Wales, National Institute for Health Research and Public Health Agency. National standards for public involvement. London: National Institute for Health Research, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Agnew A, Duffy J. Innovative approaches to involving service users in palliative care social work education. Soc Work Educ 2010; 29: 744–759. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harris DG, Coles B, Willoughby HM. Should we involve terminally ill patients in teaching medical students? A systematic review of patient’s views. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015; 5(5): 522–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Edmonds P, Burman R, Sinnott C. The goldfish bowl. Eur J Palliat Care 2004; 11: 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- 21. National Council for Palliative Care. Listening to users: helping professionals address user involvement in palliative care. London: National Council for Palliative Care, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22. National Council for Palliative Care and NHS Centre for Involvement. A guide to involving patients, carers and the public in palliative care and end of life care services. London: National Council for Palliative Care and NHS Centre for Involvement, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haarsma F, Moser A, Beckers M, et al. The perceived impact of public involvement in palliative care in a provincial palliative care network in the Netherlands: a qualitative study. Health Expect 2015; 18(6): 3186–3200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Payne SG, Small M, Oliviere N, et al. User involvement in palliative care: a scoping study. London: National Council for Palliative Care, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gott M, Stevens T, Small N, et al. User involvement in cancer care: exclusion and empowerment. Bristol: Policy Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Andershed B, Ternestedt BM. Development of a theoretical framework describing relatives’ involvement in palliative care. J Adv Nurs 2001; 34(4): 554–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brereton L, Goyder E, Ingleton C, et al. Patient and public involvement in scope development for a palliative care health technology assessment in Europe. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2014; 4: A40–A41. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Daveson BA, de Wolf-Linder S, Witt J, et al. Results of a transparent expert consultation on patient and public involvement in palliative care research. Palliat Med 2015; 29(10): 939–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Noble B, Buckle P, Gadd B. Service user and patient and public involvement in palliative and supportive care research. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015; 5(5): 459–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Booth A, Noyes J, Flemming K, et al. Guidance on choosing qualitative evidence synthesis methods for use in health technology assessments of complex interventions, http://www.integrate-hta.eu/downloads/ (2016, accessed 24 December 2016).

- 31. Booth A, Sutton A, Papaioannou D. Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. 2nd ed London: SAGE, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Booth A. Clear and present questions: formulating questions for evidence based practice. Libr Hi Tech 2006; 24: 355–368. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Connor SR, Bermedo MC. Global atlas of palliative care at the end of life. London: Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35. World Health Organization. WHO definition of palliative care, http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (2017, accessed 30 January 2017).

- 36. INVOLVE. Palliative Care Studies Advisory Group (PCSAG), http://www.invo.org.uk/communities/invodirect-org/palliative-care-studies-advisory-group-pcsag/ (2015, accessed 5 May 2018).

- 37. The Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical appraisal tools, https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/ (2017, accessed 1 January 2018).

- 38. Wright D, Foster C, Amir Z, et al. Critical appraisal guidelines for assessing the quality and impact of user involvement in research. Health Expect 2010; 13(4): 359–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Johnson M, Everson-Hock E, Jones R, et al. What are the barriers to primary prevention of type 2 diabetes in black and minority ethnic groups in the UK? A qualitative evidence synthesis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2011; 93(2): 150–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Debbi S, Elisa P, Nigel B, et al. Factors influencing household uptake of improved solid fuel stoves in low- and middle-income countries: a qualitative systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014; 11(8): 8228–8250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008; 8: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Morton R, Tong A, Howard K, et al. The views of patients and carers in treatment decision making for chronic kidney disease: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ 2010; 340: c112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Smith E, Donovan S, Beresford P, et al. Getting ready for user involvement in a systematic review. Health Expect 2009; 12(2): 197–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Boote J, Baird W, Sutton A. Involving the public in systematic reviews: a narrative review of organizational approaches and eight case examples. J Comp Eff Res 2012; 1(5): 409–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Morley RF, Norman G, Golder S, et al. A systematic scoping review of the evidence for consumer involvement in organisations undertaking systematic reviews: focus on Cochrane. Res Involv Engagem 2016; 2: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Brereton L, Ingleton C, Gardiner C, et al. Lay and professional stakeholder involvement in scoping palliative care issues: methods used in seven European countries. Palliat Med 2017; 31(2): 181–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bailey C, Wilson R, Addington-Hall J, et al. The Cancer Experiences Research Collaborative (CECo): building research capacity in supportive and palliative care. Prog Palliat Care 2006; 14: 265–270. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cotterell P, Clarke P, Cowdrey D, et al. Influencing palliative care project. West Sussex: Worthing and Southlands Hospital NHS Trust, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stevens T. Involving or using? User involvement in palliative care. In: Payne S, Seymour J, Ingleton C. (eds) Palliative care nursing: principles and evidence for practice, 2nd ed Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2008, pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- 50. McIlfatrick S, Hasson F, Hanna-Trainor L, et al. Evaluation report for all Ireland institute of hospice and palliative care ‘voices 4 care’ initiative. Dublin, 2015, https://research.hscni.net/sites/default/files/FINAL-VOICES4CARE-REPORT-AIIHPC%209%2012%2015cm.pdf

- 51. Knighting K, Forbat L, Cayless S, et al. Enabling change: patient experience as a driver for service improvement. Final report, Scotland, 2007, https://dspace.stir.ac.uk/handle/1893/3610#.XQB-WNIzbIU

- 52. Forbat L, Hubbard G, Kearney N. Patient and public involvement: models and muddles. J Clin Nurs 2009; 18(18): 2547–2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Payne SP, Turner N, Rolls M, et al. Research in palliative care: can hospices afford not to be involved? A report for the commission into the future of hospice care. London: National Council for Palliative Care, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Brereton L, Wahlster P, Lysdahl KB, et al. Integrated assessment of home based palliative care with and without reinforced caregiver support: ‘a demonstration of INTEGRATE-HTA methodological guidances’ – executive summary, http://www.integrate-hta.eu/downloads/ (2016, accessed 19 August 2017).

- 55. Froggatt K, Heimerl K, Hockley J. Challenges for collaboration. In: Hockley J, Froggatt K, Heimerl K. (eds) Participatory research in palliative care: actions and reflections. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, pp. 173–84. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Harris FM, Kendall M, Worth A, et al. What are the best ways to seek the views of people affected by cancer about end of life issues? Stirling: Macmillan Cancer Relief, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ashcroft J, Wykes T, Taylor J, et al. Impact on the individual: what do patients and carers gain, lose and expect from being involved in research. J Ment Health 2016; 25(1): 28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Collins K, Stevens T, Ahmedzai SH. Can consumer research panels become an integral part of the cancer research community? Clin Eff Nurs 2005; 9: 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Richardson A, Sitzia J, Cotterell P. ‘Working the system’. Achieving change through partnership working: an evaluation of cancer partnership groups. Health Expect 2005; 8(3): 210–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Brown V, Cotterell P, Sitzia J, et al. Evaluation of consumer research panels in cancer research networks. London: National Cancer Research Network and Macmillan Cancer Support, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rafie CL, Zimmerman EB, Moser DE, et al. A lung cancer research agenda that reflects the diverse perspectives of community stakeholders: process and outcomes of the SEED method. Res Involv Engagem 2019; 5: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cotterell P, Paine M. Involving a marginalized group in research and analysis – people with life limiting conditions. In: Beresford P, Carr S. (eds) Social care, service users and user involvement. London: Jessica Kingsley, 2012, pp. 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Marsh P, Gartrell G, Egg G, et al. End-of-Life care in a community garden: findings from a participatory action research project in regional Australia. Health Place 2017; 45: 110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Brereton L, Wahlster P, Mozygemba K, et al. Stakeholder involvement throughout health technology assessment: an example from palliative care. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2017; 33(5): 552–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. TwoCan Associates. Finding out about the priorities of users and making them count: a report for Macmillan Cancer Relief. Hereford: TwoCan Associates, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cotterell P, Clarke P, Cowdrey D, et al. Becoming involved in research: a service user led research advisory group. In: Jarrett L. (ed.) Creative engagement in palliative care: new perspectives on user involvement. Abingdon: Radcliffe Publishing, 2007, pp. 101–115. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Cotterell P. Service user involvement–an overview. In : Help the hospices conference: user involvement: nothing about us without us, Bristol, 25 April 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Greater Manchester. Next steps for end-of-life research: research priorities defined for greater Manchester. Manchester: Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research, Care Greater Manchester and National Institute for Health Research, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Riffin C, Kenien C, Ghesquiere A, et al. Community-based participatory research: understanding a promising approach to addressing knowledge gaps in palliative care. Ann Palliat Med 2016; 5(3): 218–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Caswell G, Hardy B, Ewing G, et al. Supporting family carers in home-based end-of-life care: using participatory action research to develop a training programme for support workers and volunteers. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2017; 9: e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Alabaster E, Allen D, Fothergill A, et al. User involvement in user-focused research. Cardiff: University of Wales College of Medicine, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Brazil K. Issues of diversity: participatory action research with indigenous peoples. In: Hockley J, Froggatt K, Heimerl K. (eds) Participatory research in palliative care: actions and reflections. London: Oxford University Press, 2013, pp. 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Williams A-l, Selwyn PA, McCorkle R, et al. Application of community-based participatory research methods to a study of complementary medicine interventions at end of life. Complement Health Pract Rev 2005; 10: 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Goodman C, Mathie E, Cowe M, et al. Talking about living and dying with the oldest old: public involvement in a study on end of life care in care homes. BMC Palliat Care 2011; 10: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gott M. User involvement in palliative care: rhetoric or reality. In: Payne S, Seymour J, Ingleton C. (eds) Palliative care nursing: principles and evidence for practice, 1st ed Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2004, pp. 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Cotterell P. Exploring the value of service user involvement in data analysis: ‘our interpretation is about what lies below the surface’. Educ Action Res 2008; 16: 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Beresford P, Adshead L, Croft S. Palliative care, social work and service users: making life possible. London: Jessica Kingsley, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Gott M, Ingleton C, Gardiner C, et al. Transitions to palliative care for older people in acute hospitals: a mixed-methods study. Health Serv Deliv Res 2013; 1: 1–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Palliative and end of life care Priority Setting Partnership (PeolcPSP). Putting patients, carers and clinicians at the heart of palliative and end of life care research. London: James Lind Alliance, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Cotterell P. Living with life limiting conditions: a participatory study of people’s experiences and needs. PhD Thesis, School of Health Sciences and Social Care, Brunel University, London, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Johnston B, Forbat L, Hubbard G. Involving and engaging patients in cancer and palliative care research: workshop presentation. Int J Palliat Nurs 2008; 14(11): 554–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sitzia J, Cotterell P, Richardson A. Interprofessional collaboration with service users in the development of cancer services: The Cancer Partnership Project. J Interprof Care 2006; 20(1): 60–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Gordon J, Franklin S, Eltringham SA. Service user reflections on the impact of involvement in research. Res Involv Engagem 2018; 4: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Forbat L, Knighting K, MacDonald C, et al. Evidence of impact of the cancer care research centre’s developing cancer services: patient and carer experiences programme. Final report, Scotland, 2007, https://dspace.stir.ac.uk/bitstream/1893/3621/1/Evidence%20of%20Impact%20of%20the%20Cancer%20Care%20Research%20Centres%20Developing%20Cancer%20Services%20Patient%20and%20Carer%20Experiences%20Programme%20(2007).pdf

- 85. Beresford P. Palliative care: developing user involvement, improving quality. Middlesex: Brunel University, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Staley K. Collaborate and succeed: an evaluation of the COMPASS masterclass in consumer involvement in research. London: National Cancer Research Institute, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Sargeant A, Payne S, Gott M, et al. User involvement in palliative care: motivational factors for service users and professionals. Prog Palliat Care 2007; 15: 126–132. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Collins K, Boote J, Ardron D, et al. Making patient and public involvement in cancer and palliative research a reality: academic support is vital for success. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015; 5(2): 203–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Wright DN, Hopkinson JB, Corner JL, et al. How to involve cancer patients at the end of life as co-researchers. Palliat Med 2006; 20(8): 821–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Perkins P, Barclay S, Booth S. What are patients’ priorities for palliative care research? Focus group study. Palliat Med 2007; 21(3): 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Stephens RJ, Whiting C, Cowan K. Research priorities in mesothelioma: a James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership. Lung Cancer 2015; 89(2): 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Poland F, Mapes S, Pinnock H, et al. Perspectives of carers on medication management in dementia: lessons from collaboratively developing a research proposal. BMC Res Notes 2014; 7: 463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Stevens T, Wilde D. Consumer involvement in cancer research in the United Kingdom. In: Lowes L, Hulatt I. (eds) Involving service users in health and social care research. Oxford: Routledge, 2005, pp. 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- 94. Brighton LJ, Pask S, Benalia H, et al. Taking involvement online: development and evaluation of an online forum for patient and public involvement in palliative care research. London: INVOLVE, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Cunningham M, Washington KT, Huenke DL. Lessons learned from a clinical-research partnership in outpatient palliative care. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 238. [Google Scholar]

- 96. Wright D, Corner J, Hopkinson J, et al. Listening to the views of people affected by cancer about cancer research: an example of participatory research in setting the cancer research agenda. Health Expect 2005; 9: 3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. INVOLVE. Examples of public involvement in research funding applications: decision making about implantation of cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) and deactivation during end of life care. Eastleigh: National Institute for Health Research, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 98. Kennedy S. Older carers and involvement in research: why, what and when? Nottingham: University of Nottingham, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 99. Cowdrey D, Paine M, Cotterell P. Service users and inclusion in palliative care. In: Help the hospices conference: user involvement, Bristol, 1 January 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 100. Bradburn J, Maher J. User and carer participation in research in palliative care. Palliat Med 2005; 19(2): 91–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Biondo PD, Kalia R, Khan RA, et al. Understanding advance care planning within the South Asian community. Health Expect 2017; 20: 911–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Corner J, Wright D, Hopkinson J, et al. The research priorities of patients attending UK cancer treatment centres: findings from a modified nominal group study. Br J Cancer 2007; 96(6): 875–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Wan YL, Beverley-Stevenson R, Carlisle D, et al. Working together to shape the endometrial cancer research agenda: the top ten unanswered research questions. Gynecol Oncol 2016; 143(2): 287–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Perkins P, Booth S, Vowler SL, et al. What are patients’ priorities for palliative care research? A questionnaire study. Palliat Med 2008; 22(1): 7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Cox A. Research on palliative and end-of-life care is a priority for patients. Int J Palliat Nurs 2017; 23(4): 202–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Cox A, Arber A, Gallagher A, et al. Establishing priorities for oncology nursing research: nurse and patient collaboration. Oncol Nurs Forum 2017; 44(2): 192–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Small N, Sargeant A. User and community participation at the end of life. In: Gott M, Ingleton C. (eds) Living with ageing and dying: palliative and end of life care for older people. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011, pp. 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- 108. Science Council. Promoting diversity, equality and inclusion: starter steps and quick wins. London: Science Council, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 109. Froggatt K, Preston N, Turner M, et al. Patient and public involvement in research and the Cancer Experiences Collaborative: benefits and challenges. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2014; 5: 518–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. INVOLVE. Examples of public involvement in research funding applications: supporting excellence in end of life care in dementia – SEED programme. Eastleigh: National Institute for Health Research, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 111. Allsop MJ, Ziegler LE, Kelly A, et al. Hospice volunteers as facilitators of public engagement in palliative care priority setting research. Palliat Med 2015; 29(8): 762–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Bench S, Eassom E, Poursanidou K. The nature and extent of service user involvement in critical care research and quality improvement: a scoping review of the literature. Int J Consum Stud 2018; 42: 217–231. [Google Scholar]

- 113. Manafo E, Petermann L, Mason-Lai P, et al. Patient engagement in Canada: a scoping review of the ‘how’ and ‘what’ of patient engagement in health research. Health Res Policy Syst 2018; 16: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Snape D, Kirkham J, Britten N, et al. Exploring perceived barriers, drivers, impacts and the need for evaluation of public involvement in health and social care research: a modified Delphi study. BMJ Open 2014; 4(6): e004943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Wilson P, Mathie E, Keenan J, et al. Research with patient and public involvement: a realist evaluation – the RAPPORT study. London: National Institute for Health Research, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Hickey G, Brearley S, Coldham T, et al. Guidance on co-producing a research project. Southampton: INVOLVE, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 117. Wilson P, Mathie E, Poland F, et al. How embedded is public involvement in mainstream health research in England a decade after policy implementation? A realist evaluation. J Health Serv Res Policy 2018; 23(2): 98–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Nind M. What is inclusive research? London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 119. INVOLVE. Diversity and inclusion: what’s it about and why is it important for public involvement in research? Eastleigh: INVOLVE, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 120. Liamputtong P. Researching the vulnerable: a guide to sensitive research methods. London: SAGE, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 121. Aoun S, Slatyer S, Deas K, et al. Family caregiver participation in palliative care research: challenging the myth. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 53(5): 851–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Kars MC, van Thiel GJ, van der Graaf R, et al. A systematic review of reasons for gatekeeping in palliative care research. Palliat Med 2016; 30(6): 533–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Smith E, Ross F, Donovan S, et al. Service user involvement in nursing, midwifery and health visiting research: a review of evidence and practice. Int J Nurs Stud 2008; 45: 298–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Seymour J, Cassel B. Palliative care in the USA and England: a critical analysis of meaning and implementation towards a public health approach. Mortality 2017; 22: 275–290. [Google Scholar]

- 125. Dixon J, King D, Matosevic T, et al. Equity in the provision of palliative care in the UK: review of evidence. London: Personal Social Services Research Unit, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 126. Care Quality Commission. ‘A different ending’: our review looking at end of life care. Newcastle upon Tyne: Care Quality Commission, 2016. [Google Scholar]