Short abstract

Background

Detecting pathological breast calcifications remains challenging. Based on recent studies, contrast-enhanced spectral mammography (CESM) was shown to be superior compared to full-field digital mammography (FFDM).

Purpose

To evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of CESM in suspicious breast calcifications and its impact on surgical decision-making.

Material and Methods

All screening recalled patients with suspicious calcifications that underwent CESM in the period October 2012 until September 2015 were included. One experienced radiologist provided a BI-RADS classification for the FFDM images only. The evaluation was repeated for the CESM exam. In a simulated tumor board meeting, two breast surgeons decided on the preferred surgical treatment (breast conservation therapy [BCT] versus mastectomy) for all malignant cases. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated defining BI-RADS ≥4 as being malignant. In addition, differences in surgical decision-making were analyzed and compared using McNemar’s test.

Results

In total, 147 women were included in this study (mean age = 61 years; age range = 49–75 years). Pathology showed 82 benign and 65 malignant lesions, of which 33 were ductal carcinomas in situ and 32 were invasive lesions. Diagnostic performances of CESM (differences compared to FFDM in brackets) were: sensitivity 93.8% (+3%), specificity 36.6% (−2.5%), PPV 54% (0%), and NPV 88.2% (+4%). Based on low-energy images, surgeons suggested BCT in 89% of the cases. Based on the CESM exam, no statistical changes in decisions were observed (86% BCT, P = 0.453).

Conclusion

CESM only slightly improves the diagnostic accuracy of the evaluation of breast calcifications. It is not of added value compared to FFDM in guiding surgical decision-making.

Keywords: Mammography, contrast-enhanced spectral mammography, surgical decision-making, mastectomy, breast conservation therapy

Introduction

Although most suspicious breast calcifications are of benign origin, they can also be the predominant sign of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). They might even be associated with an underlying (non-palpable) invasive breast cancer. Full-field digital mammography (FFDM) plays a pivotal role in the detection and evaluation of suspicious breast calcifications, as demonstrated by the increased incidence of DCIS since the introduction of FFDM in breast cancer screening (1). Nevertheless, the evaluation of suspicious breast calcifications remains challenging, reflected by positive predictive values in the range of 18–38% (2–6).

Not only is the detection of pathologic calcifications challenging, but also the assessment of disease extent in patients with DCIS or (non-palpable) invasive breast cancer. Breast conservation therapy (BCT) surgery with positive margins is reported to occur in 34% of DCIS cases (7), compared to 3–7% in patients with invasive (ductal or lobular) breast cancers (8). Even the use of contrast-enhanced breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which is generally regarded to be the most accurate imaging modality to assess disease extent (9), does not have any positive impact on the surgical management of DCIS (10).

Contrast-enhanced spectral mammography (CESM) was recently introduced as a novel mammographic technique. Studies in various study populations showed that CESM is consistently superior to FFDM (11), for example in symptomatic patients (12), high-risk patients (13), and women recalled from the national breast cancer screening program (14), even when the latter is combined with targeted breast ultrasound (15). Lalji et al. showed that the image quality criteria regarding breast calcifications might be superior in the low-energy (LE) images of a CESM exam compared to FFDM (16). Some studies have shown that CESM matched or even outperformed breast MRI (17,18). Hypothetically, CESM would combine the best of all imaging modalities for the evaluation of calcifications: the visualization of calcium deposits on a mammographic (LE) image combined with information on increased local breast perfusion on the contrast-enhanced recombined images.

Therefore, our primary aim was to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of CESM in suspicious breast calcifications. Our secondary goal was to study the ability of CESM to assess disease extent in patients with DCIS or invasive breast cancer, including its impact on surgical decision-making.

Material and Methods

In our institute, CESM is mainly performed in recalls from the national breast cancer screening program. Included were women recalled from screening for suspicious calcifications (as indicated by the screening radiologists) in the period October 2012 until September 2015. Exclusion criteria were: patients with known allergies or contraindications to the use of iodine-based contrast agents, as well as patients with prior breast surgery (including breast implants). Due to the retrospective design of this study, the requirement for informed consent was waived by the local ethics committee (decision number METC 15-4-233).

Image acquisition and analysis

All CESM exams were performed for both breasts in the standard craniocaudal (CC) and mediolateral oblique (MLO) views using dedicated CESM unit (Senographe* Essential with Senobright* upgrade, GE Healthcare, Chalfont St Giles, UK). The CESM imaging protocol was described previously by Lobbes et al. (19). In short, an iodine-based contrast agent (with a concentration 300 mg/mL iopromide, 1.5 mL/kg bodyweight, Ultravist, Bayer Healthcare, Berlin, Germany) was intravenously administered with a flow rate of 3 mL/s followed by saline flush 2 min before the acquisition of the first image. A typical CESM image therefore consists of a LE (which is comparable to FFDM (16)) and a recombined image (in which areas of iodine accumulation can be detected) for both breasts in two separate views.

All images were displayed on a dedicated mammography workstation (IDI MammoWorkstation 4.7.0, GE Healthcare), equipped with mammography-approved monitors (Barco Coronis 5MP Mammo, Barco, Kortrijk, Belgium). One reader, with four years of breast imaging experience, assessed the images, blinded for final histopathological results. The radiologist had never evaluated the images of this dataset before. In this per lesion analysis, LE images were shown first with location of the (recalled) suspicious calcifications. The lesion was indicated by the correspondence letter supplied by the screening institute as in daily clinical practice. The calcifications were then scored according to the BI-RADS descriptors and a final BI-RADS classification was provided (20). For this study, the reader could subdivide BI-RADS category 4 into 4a, 4b, or 4c. All lesions were measured using digital calipers. However, only the diameters of the malignant and in situ lesions were analyzed subsequently. Next, the complete CESM examinations were assessed (i.e. the combination of both LE and recombined images) and the reader could modify their final BI-RADS classification or maximum lesion diameter when deemed necessary.

In two separate sessions and simulating a multidisciplinary tumor board meeting, two dedicated breast surgeons (with ten and eight years of experience, respectively) assessed (in consensus) which surgical treatment (BCT or mastectomy) would be recommended. During this decision-making, only the malignant lesions were shown and their extent as described by the radiologist were made available to them, including information relevant for this decision, such as the pathological results, breast size, or other relevant patient information (extracted from the patient files). In the first session, their decision was based on the LE images only. The session was repeated for the entire CESM exam after eight weeks to prevent any recall bias.

Histopathological results served as the gold standard for this study. For benign lesions, the histopathological results were based on core needle biopsies. For malignant cases, including DCIS, the final surgical specimens were used. Of all lesions, pathological results were thus available. Surgical specimens and biopsies were evaluated according to current national guidelines (21).

Statistical analysis

BI-RADS classifications 1–3 were considered benign, BI-RADS classification 4a, 4b, 4c, and 5 were considered malignant. With this predefined cut-off, we calculated sensitivity, specificity, positive predicte value (PPV), negative predicte value (NPV), and area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) for both evaluations using pathology as reference standard. Since DCIS is a non-invasive (intraductal) cancer, we considered these lesions as malignant in this study. Discrepancies between measurements of disease extent in histopathological specimens (considered as the gold standard) and measurements on LE and CESM images, were visualized in Bland–Altman plots. Pearson’s correlation coefficients (PCC) for LE and CESM were also calculated (22). The mean value of the discrepancies with histopathological size measurements quantifies systematic measurement error and the 95% limits of agreement (LOA) quantify random measurement error. To evaluate whether use of CESM compared to LE has impact on surgical management decisions, the frequency of concordant and discordant decisions was recorded. McNemar’s test was used to test for statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS (IBM SPSS statistics; version 21.0, Armonk, NY, USA). P values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

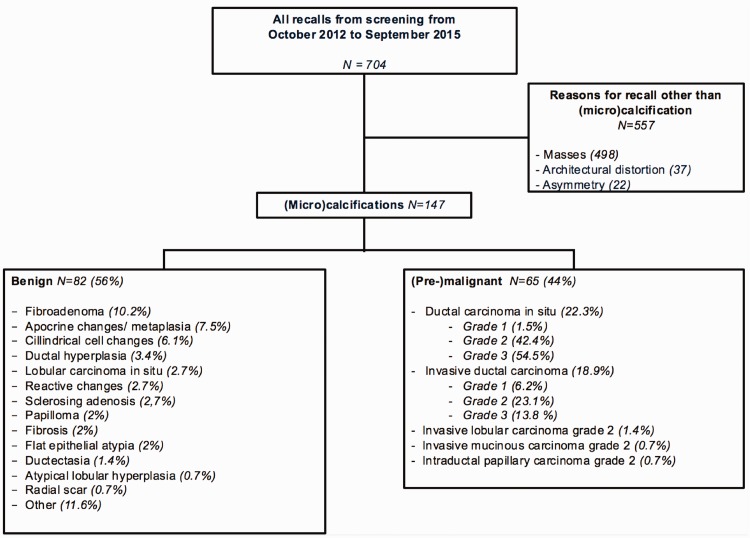

During the study period, 704 patients were recalled from the national breast cancer screening program and visited our institute for further analysis. Of these, 147 women were recalled from screening for suspicious calcifications (mean age = 60.5 years; age range = 49–75 years). Final pathology showed 82 benign and 65 malignant lesions, of which 33 DCIS lesions and 32 invasive lesions were diagnosed. A detailed overview of patient inclusion and final histopathological diagnosis is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient selection and final diagnosis.

Diagnostic performance parameters for the assessment of breast calcifications on the LE images were: sensitivity = 90.8% (59/65); specificity = 39% (32/82); PPV = 54.1% (59/109); and NPV = 84.2% (32/38). For the entire CESM, sensitivity was 93.8% (61/65), specificity was 36.6% (32/82), PPV was 54% (61/113), and NPV was 88.2% (30/34). Table 1 shows a detailed overview of the diagnostic performance parameters, including the 95% confidence intervals and absolute numbers of true-positive, false-negative, false-positive, and true-negative test results.

Table 1.

Detailed overview of the diagnostic performance.

| Performance | LE (95% CI) | CESM (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (%) | 90.8 (81.0–96.6) | 93.8 (85.0–98.3) |

| Specificity (%) | 39.0 (28.4–50.4) | 36.6 (26.2–48.0) |

| Positive predicted value (%) | 54.1 (49.4–58.8) | 54.0 (49.6–58.3) |

| Negative predicted value (%) | 84.2 (70.4–92.3) | 88.2 (73.6–95.3) |

| Mean diameter (PCC) | 0.91 (0.805) | 3.56 (0.785) |

|

Performance – Absolute numbers (n = 147) |

LE |

CESM |

| True positive | 59 | 61 |

| True negative | 32 | 30 |

| False positive | 50 | 52 |

| False negative | 6 | 4 |

|

Bland–Altman plot |

LE |

CESM |

| Mean | 0.2615 | 4.492 |

| LOA upper | 39.665 | 36.261 |

| LOA lower | –39.142 | –27.276 |

CI, confidence interval; PCC, Pearson’s correlation coefficient; LOA, limits of agreement.

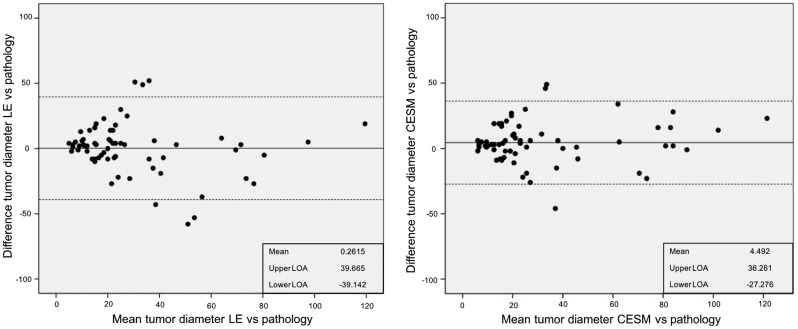

Mean diameter of all malignant and in situ lesions was 29.4 mm (standard deviation [SD] = 27.3 mm). When comparing tumor size measurements as assessed by the radiologist on the LE and CESM images versus histopathological size diameter, the mean difference was 0.3 mm (95% LOA -39.1 to +39.7 mm) for LE and 4.5 mm (95% LOA -27.3 to +36.3 mm) for CESM (Fig. 2). These findings imply that 95% of size measurements on LE imaging lie within a range of 3.9 cm below to 4 cm above the true size (as measured in histopathological specimens). For CESM, the random measurement errors are slightly smaller, with 95% of size measurements situated in a range of 2.7 cm below to 3.6 cm above the true size. The higher mean difference for CESM indicates that CESM tends to slight overestimation of size. Accurate assessment of disease extent is important for surgical management decision. An alternation in diameter occurred in 51/65 (78.4%) cases, in which we observed a mean difference of 4.23 mm (–32 mm to +60 mm).

Fig. 2.

Bland–Altman plots visualizing the discrepancies between maximum tumor size measurements according to histopathological examination (gold standard) and maximum tumor size measurements on imaging. The left panel shows results for LE images and the right panel the discrepancies for the entire CESM exam. Also presented are the mean discrepancy (in mm) with histopathological measurements and the upper and lower 95% LOA.

The PCC for LE was 0.700, P < 0.001 and for CESM 0.835, P < 0.001.

Off all invasive breast cancers, 84.4% showed enhancement (27/32), whereas enhancement was observed in 81.1% of the pure DCIS lesions (27/33). In these latter cases, enhancement was observed in 88.9% (16/18) of the high-grade DCIS, 71.4% (10/14) in the intermediate grade, and 100% (1/1) in the low-grade DCIS. The five non-enhanced invasive breast cancers mean size is 23.7 mm (range = 5–62 mm). For the six non-enhanced DCIS lesions, the mean size was 23 mm (range = 8–40 mm).

Based on all available clinical information and the LE images, the surgeons recommended BCT as the optimal surgical strategy in 58 cases (89.2%), with the remaining cases recommended to undergo primary mastectomy. In the second session, where their decision was based on all information including the entire CESM exam, they recommended performing BCT in 55 cases (84.6%). Decisions were concordant in 58/65 patients and discordant in seven patients. These differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.453). Based on the entire CESM exam, five cases were recommended to undergo mastectomy instead of BCT, whereas two cases were recommended to downsize surgery to BCT instead of mastectomy.

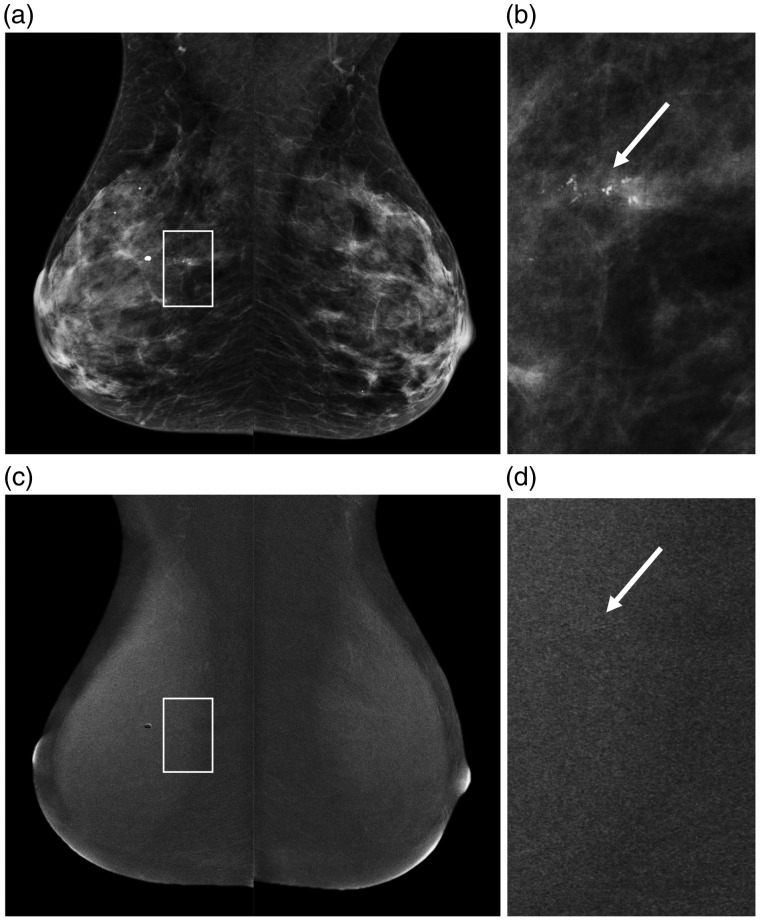

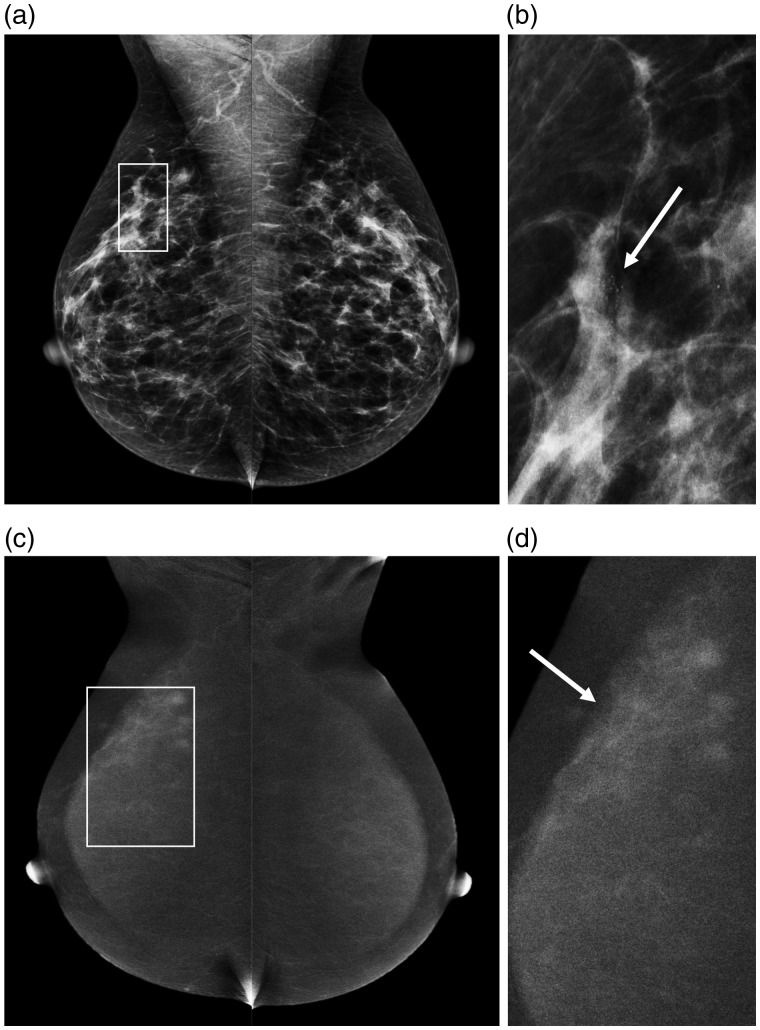

Two examples of using CESM to evaluate suspicious breast calcifications were presented in Figs. 3 and 4.

Fig. 3.

A 50-year-old patient who was recalled for suspicious breast calcifications. (a) The LE images of the subsequent CESM exam that was performed, with a detailed view of the calcifications in (b) (arrow). On the recombined images (c), no abnormal enhancement was seen in the area of the calcifications, that appear as black on the detailed recombined image (d, arrow). Final histopathological results revealed a 20-mm grade 2 DCIS.

Fig. 4.

Example of a 52-year old patient recalled for suspicious breast calcifications in the right breast. (a) The LE images with a detailed view of the calcifications in (b) (arrow). After contrast administration, the recombined images (c) show an area of segmental non-mass enhancement, showing that the true disease extent is much larger than was initially suspected on conventional mammography (d, arrow). Final histopathological results revealed a small invasive ductal carcinoma (6 mm) surrounded by grade 2 DCIS (40 mm).

Discussion

In theory, CESM can evaluate suspicious breast calcifications more accurately, as it combines the high spatial resolution and excellent visibility of suspicious calcifications using mammography with information on lesion vascularity. Therefore, we aimed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of CESM in breast calcifications and studied whether the use of CESM could result in improved surgical decision-making. We observed an only slight improvement in sensitivity and NPV at the predefined cut-off point. Measurement error in the assessment of disease extent is slightly reduced when using CESM, although CESM tends to slightly overestimate disease extent. Observed changes were minute and proved to have no significant impact on surgical decision-making.

Studies have shown that CESM is superior to FFDM in overall performance. In a recent systematic review covering 920 patients (eight studies), the estimated sensitivity of CESM was 98% (95% CI = 96–100), with a reported estimated specificity of 58% (95% CI = 38–77) (23). The moderate specificity might be explained by the preponderance of data (3/8 studies selected) from one study group. This group cited only a FFDM specificity of 15%, questioning the validity of results, showing a CESM specificity of only 40%. Jochelson et al. performed a recalculation of results using the other cited papers, resulting in an estimated CESM specificity of 78% (95% CI = 56–90) (24). However, most studies focused on the entire spectrum of breast lesions, not only on one specific subtype such as suspicious calcifications.

To the best of our knowledge, only two papers studied the diagnostic performance of CESM in calcifications. These were both by Cheung et al. and showed a significant overlap in the inclusion period (52 patients enrolled from February 2012 until December 2013 (25) versus 94 patients from February 2012 until June 2015 (26). Consequently, we compared our results to the largest study by Cheung et al. (26). In this study, sensitivity was 89%, specificity 87%, PPV 77%, and NPV 95%. Thus, cancer detection rates are in line with our observations, but their false-positive rates are much lower, as expressed in a superior specificity and PPV when compared to our study.

In our study, sensitivity of detecting breast cancer or DCIS was similar for LE and CESM in patients with a malignant lesion according to the gold standard. However, with the use of CESM a BI-RADS score of 5 was assigned more frequently than scores 4a/4b/4c (66.2% vs. 27.6%). When using only LE, these percentages were 16.9% and 73.8%, respectively. This substantial shift towards a higher frequency BI-RADS 5 (from 4a/4b/4c) indicates that CESM provides the reader with more confidence that the observed suspicious calcifications represent DCIS or breast cancer. But since the predefined cut-off to differentiate between benign lesions and malignant ones was ≥4, this did not result in a more pronounced improvement in diagnostic accuracy parameters.

With respect to enhancement of suspicious breast calcifications, we did not observe any relevant differences between the amount of enhancement between invasive or in situ breast cancers. Consequently, CESM cannot be used to distinguish between these two if one would opt to study a more “wait-and-see” approach for pure DCIS. In addition, we did not observe any relevant differences between different grades of pure DCIS: the only low-grade DCIS in this study showed enhancement, whereas approximately 11% of the high-grade DCIS did not show any enhancement. Hence, CESM cannot be used to distinguish between different grades of DCIS, especially low-grade versus high-grade DCIS.

We observed that invasive and non-invasive cancer show no enhancement in a comparable proportion. In theory, the numbers of invasive cancers showing no enhancement should be low, as they normally have access to blood and lymphatic vessels. However, our group of invasive cancers without any enhancement is too low to draw any definite conclusions (n = 5). Nevertheless, the amount of enhancement might hold important diagnostic information which should be studied in larger populations, especially since methods for assessing enhancement quantitatively have recently been published. (8,27)

In this study, we did not perform any magnification views as added view to evaluate calcifications. In the current digital era, electronic magnification (“zooming”) can be used to assess breast calcifications in detail. In a previous study by Fallenberg et al., it was nevertheless shown that even then dedicated magnification views improve the visibility of calcifications (AUC value 0.664 for mammography versus 0.813 for mammography plus magnification views), but the sample size of 100 cases is rather small. However, the AUC value of 0.813 is still not high enough to refrain from any tissue sampling. In other words, if calcifications are deemed “suspicious” on FFDM, adding magnification views only visualizes the calcifications better, but the indication for performing a (stereotactic) biopsy will remain (28).

With respect to the assessment of disease extent, Cheung et al. observed a better agreement between measurement performed on CESM compared to FFDM (with histopathology as gold standard). For FFDM, the mean difference was 4.2 mm, whereas for CESM it was 0.5 mm (25). However, these differences in both studies are relatively small and presumably of no impact on surgical decision-making, as the breast surgeon will consider an oncologically safe margin (<4 mm) surrounding the calcifications anyway (29). This was the main reason why we decided to also consider the impact of the findings on surgical decision-making, as this is the study outcome that is most relevant when assessing disease extent. As might be expected based on these results, there were no statistically significant differences between the surgical treatment plans based on the LE images or the entire CESM exam.

Our study has some limitations. First, the study was retrospective in design with a limited sample size (although this is the largest study on this topic so far to the best of our knowledge). Diagnostic performance of the reader did not show a significant increase in sensitivity and specificity at the predefined cut-off value when using the entire CESM exam. Second, surgical decision-making was based on documented patient information and presentation of imaging findings to simulate a multidisciplinary tumor board meeting as accurately as possible. This did not allow the surgeons to perform physical examinations and explore patient preferences or history, which is mandatory to optimize the surgical decision-making process, especially with respect to continuously evolving oncoplastic surgical approaches. Furthermore, we opted to perform a simulated multidisciplinary team meeting due to the retrospective nature of this study. Therefore, an objective evaluation of the impact of CESM on surgical outcome (in terms of radical surgery) was not possible. Although the simulated multidisciplinary team might reach the same conclusion regarding proposed surgical strategy, the patient’s preference could lead to an alternative surgery. Hence, a prospective randomized controlled clinical trial studying the impact of either FFDM or CESM on surgical outcome would be needed. However, in this retrospective study design, this evaluation simulated daily clinical practice as closely as possible. Third, the population of patients represents a selected group recalled from a national screening program, wherein screening radiologists decide whether an abnormality should be recalled. In theory, a different set of patients could be selected if other radiologists would read the same exams. However, this is current practice in our breast cancer screening program. Fourth, this was a single reader study, albeit with an experienced breast radiologist. This refrained us from studying inter-observer variation in the evaluation of suspicious calcifications using CESM.

In conclusion, the results of our study showed that CESM resulted in an only minute improvement in sensitivity and NPV at the predefined cut-off point, with the measurement error in the assessment of disease extent being slightly reduced compared to FFDM. However, these small changes did not seem to have a relevant impact on surgical decision-making.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with regard to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: ML received speaker’s fees from GE Healthcare.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Weber RJ, Nederend J, Voogd AC, et al. Screening outcome and surgical treatment during and after the transition from screen-film to digital screening mammography in the south of The Netherlands. Int J Cancer 2014; 137:135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liberman L, Abramson AF, Squires FB, et al. The breast imaging reporting and data system: positive predictive value of mammographic features and final assessment categories. Am J Roentgenol 1998; 171:35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coşar ZS, Çetin M, Tepe TK, et al. Concordance of mammographic classifications of microcalcifications in breast cancer diagnosis. Clin Imaging 2005; 29:389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnside ES, Ochsner JE, Fowler KJ, et al. Use of microcalcification descriptors in BI-RADS 4th edition to stratify risk of malignancy. Radiology 2007; 242:388–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bent CK, Bassett LW, D’Orsi CJ, et al. The positive predictive value of BI-RADS microcalcification descriptors and final assessment categories. Am J Roentgenol 2010; 194:1378–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim SY, Kim HY, Kim EK, et al. Evaluation of malignancy risk stratification of micro calcifications detected on mammography: a study based on the 5th edition of BI-RADS. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22:2895–2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Esser S, Peters NHGM, van den Bosch MAAJ, et al. Surgical outcome of patients with core-biopsy-proven nonpalpable breast carcinoma: a large cohort follow-up study. Ann Surg Oncol 2009; 16:2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lobbes MB, Vriens IJ, Bommel ACV, et al. Breast MRI increases the number of mastectomies for ductal cancers, but decreases them for lobular cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017; 162:353–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gruber IV, Rueckert M, Kagan KO, et al. Measurement of tumour size with mammography, sonography and magnetic resonance imaging as compared to histological tumour size in primary breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2013; 13:328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fancellu A, Turner RM, Dixon JM, et al. Meta-analysis of the effect of preoperative breast MRI on the surgical management of ductal carcinoma in situ. Br J Surgery 2015; 102:883–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tagliafico AS, Bignotti B, Rossi F, et al. Diagnostic performance of contrast-enhanced spectral mammography: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast 2016; 28:13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tennant S, Cornford E, James J, et al. Contrast-enhanced spectral mammography: what is the “added value” in a symptomatic setting? Initial findings from a UK centre. Breast Cancer Res 2015; 17:14.25848982 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jochelson MS, Pinker K, Dershaw DD, et al. Comparison of screening CEDM and MRI for women at increased risk for breast cancer: A pilot study. Eur J Radiol 2017; 97:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lalji UC, Houben IPL, Prevos R, et al. Contrast-enhanced spectral mammography in recalls from the Dutch breast cancer screening program: validation of results in a large multireader, multicase study. Eur Radiol 2016; 26:4371–4379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luczynska E, Heinze S, Adamczyk A, et al. Comparison of the mammography, contrast-enhanced spectral mammography and ultrasonography in a group of 116 patients. Anticancer Res 2016; 36:4359–4366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lalji UC, Jeukens CRLPN, Houben I, et al. Evaluation of low-energy contrast-enhanced spectral mammography images by comparing them to full-field digital mammography using EUREF image quality criteria. Eur Radiol 2015; 25:2813–2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fallenberg EM, Dromain C, Diekmann F, et al. Contrast-enhanced spectral mammography versus MRI: Initial results in the detection of breast cancer and assessment of tumour size. Eur Radiol 2013; 24:256–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lobbes MB, Lalji UC, Nelemans PJ, et al. The quality of tumor size assessment by contrast-enhanced spectral mammography and the benefit of additional breast MRI. J Cancer 2015; 6:144–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lobbes MBI, Lalji U, Houwers J, et al. Contrast-enhanced spectral mammography in patients referred from the breast cancer screening programme. Eur Radiol 2014; 24:1668.–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sickles EA, D’Orsi CJ, Bassett LW, et al. ACR BI-RADS® Mammography. In: ACR BI-RADS® Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. Reston, VA: ACR, 2013.

- 21.Nationaal Borstkanker Overleg Nederland (NABON). National guideline breast cancer 2012. Amsterdam: NABON, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics 2011; 12:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tagliafico AS, Bignotti B, Rossi F, et al. Diagnostic performance of contrast-enhanced spectral mammography: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast 2016; 28:13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jochelson M, Lobbes MBI, Bernard-Davila B. Reply to Tagliafic AS, Bignotti B, Rossi F, et al . Breast 2016; 32:267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheung Y-C, Tsai H-P, Lo Y-F, et al. Clinical utility of dual-energy contrast-enhanced spectral mammography for breast microcalcifications without associated mass: a preliminary analysis. Eur Radiol 2015; 26:1082–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheung Y-C, Juan YH, Lin YC, et al. Dual-energy contrast-enhanced spectral mammography: enhancement analysis on BI-RADS 4 non-mass microcalcifications in screened women. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0162740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deng C, Juan Y, Cheung Y, et al. Quantitative analysis of enhanced malignant and benign lesions on contrast-enhanced spectral mammography. Br J Radiol 2018; 91:20170605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fallenberg EM, Dimitrijevic L, Diekmann F. Impact of magnification views on the characterization of microcalcifications in digital mammography. Rofo 2014; 186;274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lobbes MBI, Vriens IJH, van Bommel ACM, et al. Breast MRI increases the number of mastectomies for ductal cancers, but decreases them for lobular cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017; 162:353–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]