Abstract

Dry eye disease is a common ocular surface disease in patients who are undergoing cataract surgery. The significance of dry eye disease is often underestimated or overlooked during preoperative assessment of cataract. We report an 80-year-old patient, with a background of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes, who presented with an acute corneal melt and perforation associated with undiagnosed dry eye disease and use of topical ketorolac 1 week following an uncomplicated cataract surgery. The patient underwent repeated corneal gluing for corneal perforation and was subsequently diagnosed and treated for bilateral moderate-severe dry eye disease. This case highlights the importance of meticulous preoperative assessment and management of the ocular surface, especially in patients with systemic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes prior to cataract surgery. The implication of the use of topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs following cataract surgery – which might have contributed to the process of corneal melt in our case – is also discussed.

Keywords: cataract surgery, corneal gluing, corneal melt, corneal perforation, dry eye, keratoconjunctivitis sicca, rheumatoid arthritis

Introduction

Cataract surgery is one of the most commonly performed surgeries worldwide, with approximately 20 million procedures being performed annually. With the advancement of phacoemulsification technology, intraocular lens designs and power calculation and surgical techniques,1,2 patients’ expectation of good visual and refractive outcomes following cataract surgery is continually rising.3 This is reflected by the lower preoperative visual impairment threshold and the rising cataract surgery rates observed in many countries.3–5

Dry eye disease (DED) is a common ocular surface disease among patients who are undergoing cataract surgery. With an estimated prevalence rate of 50–60%, DED poses many important implications on cataract surgery.6,7 First, DED may affect the preoperative biometry assessment, resulting in an undesired postoperative refractive error.8 Second, DED can cause significant ocular discomfort and patient dissatisfaction, nullifying the beneficial effect of visual gain from cataract surgery.9 Furthermore, the exacerbation of DED following cataract surgery may rarely lead to sight-threatening complications such as corneal melting and perforation.10–13 Therefore, meticulous preoperative assessment and optimal management of DED before cataract surgery are of utmost importance. Herein, we report a case of acute corneal melt with perforation, associated with undiagnosed DED and topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), occurring as soon as 1 week after an uncomplicated cataract surgery.

Case description

This is a case report with literature review. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication. An 80-year-old gentleman was referred to our eye unit for assessment of bilateral cataract. His past medical history included type 2 diabetes and seropositive rheumatoid arthritis controlled by sulfasalazine. The corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA) was 20/25 in the right eye (OD) and 20/50 in the left eye (OS). Slit-lamp examination showed bilateral grade 3 nuclear sclerotic cataract (based on the Lens Opacities Classification System III)14 with no other ocular abnormality detected. He underwent an uneventful phacoemulsification with intraocular lens implant and was started on topical prednisolone 1% TID, ketorolac 0.5% TID and chloramphenicol 0.5% TID postoperatively. Topical ketorolac was started postoperatively to reduce the risk of macular oedema after cataract surgery in view of the history of diabetes.

After 1 week, the patient presented to the eye emergency department with an acute left eye pain and hand movement vision. Slit-lamp examination showed a left inferior, noninfiltrated, crescentic corneal melt with epithelial defect, spanning 4–8 o’clock position (away from the temporal primary corneal incision), with a small Seidel-positive corneal perforation and flat anterior chamber. There was severe corneal punctate staining in the left eye and mild punctate staining in the right eye, suggestive of underlying DED. A left emergency corneal suturing and reformation of anterior chamber was performed. All postoperative drops, such as topical preservative-free sodium hyaluronate 0.2% Q2H, levofloxacin 0.5% Q2H and dexamethasone 0.1% BD, were discontinued. Oral prednisolone 40 mg was started in view of the possibility of peripheral ulcerative keratitis associated with the underlying seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. On the next day, there was a mild persistent leak at the perforated site, which warranted a corneal gluing using cyanoacrylate glue (Histoacryl; B. Braun Medical Ltd, Sheffield, UK) and insertion of a bandage contact lens (BCL). Bilateral lower lid punctal plugs were inserted. Blood tests, including the inflammatory markers, were all normal. The oral prednisolone was stopped after 2 days as there was no convincing evidence of vasculitis or peripheral ulcerative keratitis and the corneal melt was likely attributed to DED. No flare-up of rheumatoid arthritis was reported.

After 1 week, the anterior chamber had successfully reformed. However, the corneal glue and BCL spontaneously dislodged after 2 weeks, resulting in a recurrent pinpoint corneal wound leak with iris plugging. He underwent a repeat corneal gluing and the eye stabilized within a week with a formed anterior chamber. CDVA was 20/50. The cornea successfully re-epithelialized under the glue 2 months later (Figure 1), and the BCL and glue were subsequently removed. The patient complained of ongoing grittiness and discomfort in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination showed mild meibomian gland dysfunction with right moderate and left severe inferior/central corneal punctate staining consistent with uncontrolled DED. The tear breakup time was 6 s, corneal sensation was normal and Schirmer’s test (with topical anaesthesia) was 0 mm/5 min in both eyes. All the inflammatory and serologic markers for Sjögren’s syndrome were negative, except for a moderately raised rheumatoid factor (53.1 IU/ml; normal: 0–14). Topical preservative-free sodium hyaluronate 0.2% Q2H, lacrilube nocte, cyclosporine 0.1% nocte and an 8-week tapering regime of prednisolone 0.5%, starting from QID, were given. Bilateral lower lid punctal plugs were re-inserted. Two years after cataract surgery, the DED had improved significantly, with the left eye remaining settled with an inferior corneal scar (Figure 2a and b) and a CDVA of 20/30 (–3.25/+3.75 × 70).

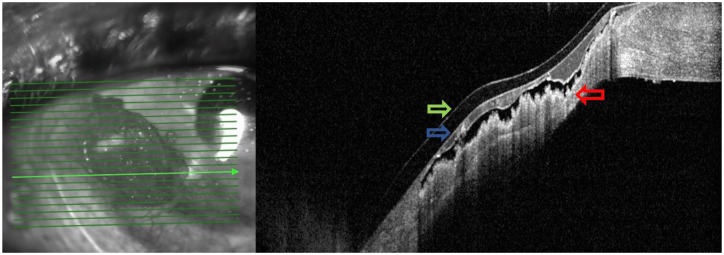

Figure 1.

Anterior segment optical coherence tomography of the left eye showing inferonasal corneal re-epithelialization and stromal reformation (red arrow) under the glue (blue arrow) and bandage contact lens (green arrow) 2 months after the corneal gluing procedure.

Figure 2.

(a) Slit-lamp photography of the left eye showing a clear central cornea with a mild inferonasal scar (red arrow) at 2-year post-corneal gluing. (b) Anterior segment optical coherence tomography showing significant corneal remodelling and thickening with an area of full-thickness corneal hyper-reflectivity (yellow arrow) corresponding to the scarred area.

Discussion

In this report, we highlight a patient presenting with corneal perforation 1 week following uncomplicated cataract surgery associated with undiagnosed asymptomatic DED and postoperative use of topical NSAIDs. Several studies have reported a high prevalence rate (50–60%) of DED in patients who were undergoing cataract surgery.6,7 In addition, studies have shown that as many as 50% of the patients with DED were asymptomatic during the initial evaluation for cataract surgery,6,7 which was similarly observed in our case. With the increasing referrals for cataract surgery, clinicians are becoming more efficient and targeted during their initial assessment of cataract, which may render DED undiagnosed or overlooked particularly in the absence of ocular surface symptoms. In view of the significantly abnormal Schirmer’s test result in both eyes and evidence of moderate DED in the nonoperated eye, it was likely that the co-existing DED was not detected during the initial assessment of cataract in our case.

Studies have also shown that cataract surgery could exacerbate or even cause DED postoperatively.15–17 The worsening of ocular surface usually peaked from 1 week to 1 month after surgery followed by a gradual improvement over time. Various hypotheses have been proposed to explain the reasons why cataract surgery could exacerbate or even cause DED postoperatively.18 These included prolonged exposure to the light of operating microscope, infrequent intraoperative wetting of the ocular surface, inflammation related to the cataract surgery, use of postoperative preserved drops and damage to corneal nerves during corneal incisions. In addition, diabetes has been shown to increase the risk of DED following cataract surgery.19

To our best knowledge, there were only five cases of sterile corneal melt with perforation following cataract surgery reported in the literature.10–13 The corneal perforation in these cases occurred between 1 and 6 weeks postoperative and they shared a few commonalities such as inferior paracentral location, sterile in nature and a history of rheumatoid arthritis or Sjögren’s syndrome. Although the cataract surgery was considered uneventful intraoperatively, it was likely that various potential factors could have exacerbated the DED and corneal melt postoperatively. The factors included the pre-existing undiagnosed DED, inflammation related to the cataract surgery, underlying rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes and use of postoperative topical preserved drops and NSAIDs. Topical NSAIDs were started in our patient postoperatively because several randomized controlled studies have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of topical NSAIDs in reducing the risk of postoperative cystoid macular oedema in diabetic patients following cataract surgery.19 However, a few reports have highlighted the association of topical NSAIDs and corneal complications such as corneal ulceration, melt and perforation.20,21 Unfortunately, no anterior segment photos were available during the initial presentation as the patient presented during the weekend where imaging facility was not available. However, we trust that the take home messages of this case shall remain significant.

This case report aims to raise the awareness of this potentially sight-threatening postoperative complication following cataract surgery among all ophthalmologists. Meticulous preoperative assessment and management of pre-existing ocular surface diseases should be undertaken before cataract surgery, especially in patients with known underlying rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes. We recommend that all patients should undergo a comprehensive preoperative ocular surface evaluation, including lid margin assessment, fluorescein staining of the cornea, tear breakup time and Schirmer’s test (particularly in high-risk patients), to detect for any underlying DED. Preservative-free drops should be used and topical NSAIDs should be prescribed judiciously in patients with DED after cataract surgery.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: DSJT is supported by the Fight for Sight / John Lee, Royal College of Ophthalmologists Primer Fellowship.

ORCID iD: Darren Shu Jeng Ting  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1081-1141

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1081-1141

Contributor Information

Darren Shu Jeng Ting, Sunderland Eye Infirmary, Sunderland, UK; Academic Ophthalmology, Division of Clinical Neuroscience, School of Medicine, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK.

Saurabh Ghosh, Sunderland Eye Infirmary, Sunderland, UK.

References

- 1. Brandsdorfer A, Kang JJ. Improving accuracy for intraocular lens selection in cataract surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2018; 29: 323–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ting DSJ, Rees J, Ng JY, et al. Effect of high-vacuum setting on phacoemulsification efficiency. J Cataract Refract Surg 2017; 43: 1135–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Erie JC. Rising cataract surgery rates: demand and supply. Ophthalmology 2014; 121: 2–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Taylor HR, Hien TV, Keefe JE. Visual acuity thresholds for cataract surgery and changing Australian population. Arch Ophthalmol 2006; 124: 1750–1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Behndig A, Montan P, Stenevi Uet al. One million cataract surgeries: Swedish National Cataract Register 1992–2009. J Cataract Refract Surg 2011; 37: 1539–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Trattler WB, Majmudar PA, Donnenfeld EDet al. The Prospective Health Assessment of Cataract Patients’ Ocular Surface (PHACO) study: the effect of dry eye. Clin Ophthalmol 2017; 11: 1423–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gupta PK, Drinkwater OJ, VanDusen KWet al. Prevalence of ocular surface dysfunction in patients presenting for cataract surgery evaluation. J Cataract Refract Surg 2018; 44: 1090–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Epitropoulos AT, Matossian C, Berdy GJet al. Effect of tear osmolarity on repeatability of keratometry for cataract surgery planning. J Cataract Refract Surg 2015; 41: 1672–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Szakats I, Sebestyen M, Toth Eet al. Dry eye symptoms, patient-reported visual functioning, and health anxiety influencing patient satisfaction after cataract surgery. Curr Eye Res 2017; 42: 832–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pfister RR, Murphy GE. Corneal ulceration and perforation associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 1980; 98: 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cohen KL. Sterile corneal perforation after cataract surgery in Sjögren’s syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol 1982; 66: 179–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chaudhary R, Mushtaq B. Spontaneous corneal perforation post cataract surgery. BMJ Case Rep 2011; 2011: bcr1120115099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Murtagh P, Comer R, Fahy G. Corneal perforation in undiagnosed Sjögren’s syndrome following topical NSAID and steroid drops post routine cataract extraction. BMJ Case Rep 2018; 2018: bcr-2018-225428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chylack LT, Jr, Wolfe JK, Singer DMet al. The lens opacities classification system III. The longitudinal study of cataract study group. Arch Ophthalmol 1993; 111: 831–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Park Y, Hwang HB, Kim HS. Observation of influence of cataract surgery on the ocular surface. PLoS ONE 2016; 11: e0152460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kasetsuwan N, Satitpitakul V, Changul Tet al. Incidence and pattern of dry eye after cataract surgery. PLoS ONE 2013; 8: e78657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li XM, Hu L, Hu Jet al. Investigation of dry eye disease and analysis of the pathogenic factors in patients after cataract surgery. Cornea 2007; 26: S16–S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chuang J, Shih KC, Chan TCet al. Preoperative optimization of ocular surface disease before cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 2017; 43: 1596–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jiang D, Xiao X, Fu Tet al. Transient tear film dysfunction after cataract surgery in diabetic patients. PLoS ONE 2016; 11: e0146752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wolf EJ, Kleiman LZ, Schrier A. Nepafenac-associated corneal melt. J Cataract Refract Surg 2007; 33: 1974–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guidera AC, Luchs JI, Udell IJ. Keratitis, ulceration, and perforation associated with topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Ophthalmology 2001; 108: 936–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]