Abstract

Red blood cell distribution width (RDW) has been recently demonstrated to be a predictor of inflammation. High pretreatment RDW level is associated with poor survival outcomes in various malignancies, although the results are controversial. We aimed to investigate the prognostic role of RDW. A systematic literature search was performed in MEDLINE and EMBASE till April 2018. Pooled hazard ratios (HRs) were estimated for overall survival (OS) and combined disease-free survival, progression-free survival, and recurrence-free survival (DFS/PFS/RFS). 49 studies with 19,790 individuals were included in the final analysis. High RDW level adversely affected both OS and DFS/PFS/RFS. For solid cancers, colorectal cancer (CRC) had the strongest relationship with poor OS, followed by hepatic cancer (HCC). Negative OS outcomes were also observed in hematological malignancies. Furthermore, patients at either early or advanced stage had inverse relationship between high pretreatment RDW and poor OS. Studies with cut-off values between 13% and 14% had worse HRs for OS and DFS/PFS/RFS than others. Furthermore, region under the curve (ROC) analysis was used widely to define cut-off values and had relatively closer relationship with poorer HRs. In conclusion, our results suggested that elevated pretreatment RDW level could be a negative predictor for cancer prognosis.

Keywords: red blood cell distribution width, malignancies, prognosis, meta-analysis

Introduction

Red blood cell distribution width (RDW) is a conventional biomarker for erythrocyte volume variability and an indicator of erythrocyte homeostasis 1. Recent evidence shows that anisocytosis is involved in a variety of human diseases such as cardiovascular diseases 2,3, thrombosis 3, diabetes 4, and cancers 5,6. High RDW level is a negative prognoistic marker for these diseases, and inflammation is the leading mechanism 1.

Inflammation is a key regulator of cancer initiation and progression 7. Recently, RDW, which plays a critical role in inflammatory response, has attracted attention because of the connection between inflammation and cancer. RDW increases in malignant tumors 8,9. Furthermore, higher RDW levels are also significantly associated with advanced stages of cancer and metastasis 10,9.

A mounting body of evidence suggests that elevated RDW level also correlated with poor prognosis for various cancers, which included esophageal cancer 11-15, gastrointestinal tumors 16-18, HCC 19-22, lung cancer 23-26, and hematological malignancies 27-30. However, the prognostic impact of RDW has not been comprehensively investigated because of the inevitable heterogeneity of the samples studied. The aim of the present study was to assess the relationship between RDW and clinical outcomes in patients with cancer.

Methods

Search strategy

Our meta-analysis was registered in PROSPERO with the number CRD42018093419. Studies were identified from MEDLINE and EMBASE up to April 2018. Medical subject headings and Emtree headings were searched and combined with the following key-words: “red blood cell distribution width OR RDW” and “prognosis OR prognostic OR survival OR outcome” and “cancer OR tumor OR carcinoma OR neoplasm”. The references of the included articles were also scanned to identify additional studies. Supplementary Table 1 presents the full search strategy.

Study selection

We included prospective or retrospective studies that assessed RDW level prior to any treatment in patients with proven pathological diagnosis of cancer. Furthermore, eligible studies should provide hazard ratio (HR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for clinical outcomes, or enough data to calculate these quantities. We excluded studies based on the time when blood samples were collected; studies were eliminated if they involved patients who received any therapy within two weeks prior to blood donation. Conference abstracts, review articles, case reports, letter, animal studies, or in vitro studies were not eligible for our analysis. Studies with duplicate or overlapping data were also excluded. Two reviewers (PF-W and SY-S) independently performed the study selection and resolved any disagreements via discussion.

Data extraction

Data from all included studies were extracted by one author (SY-S) and was cross-checked by another author (PF-W). Data were extracted using the name of the first author, year of publication, country, tumor type, clinical/pathological tumor stage, study characteristics (sample size, age, and gender), stage criteria, statistical methods used to calculate the cut-off value for RDW, survival outcomes, and sources of HRs (univariate or multivariate). Furthermore, we calculated the male-to-female gender ratio (M/F gender ratio) to precisely assess the various gender distributions among the included cohorts. The interval of the M/F gender ratio of a balanced composition ranged from one to two; the M/F ratio of a female-dominant composition was less than one, whereas that of male-dominant cohorts was more than two. HRs and 95% CIs were extracted for overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS), progression-free survival (PFS), and recurrence-free survival (RFS). We used the Engauge digitizer to estimate HRs and their 95% CIs if eligible studies provided only Kaplan-Meier curves and we received no response from the investigators after two requests for HRs 31. All disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Outcomes

We defined OS as the time from the study enrollment to the date of death from any cause or last follow-up. As DFS, PFS, and RFS share similar endpoints, they were analyzed together as one outcome, DFS/PFS/RFS 32-34.

Statistical analyses

We used STATA version 14.0 (STATA, College Station, TX) in all analyses. Multivariate-adjusted HRs were used when possible, and univariate HRs were included in the meta-analysis if multivariate-adjusted HRs were missing. Pooled estimates with 95% CIs, separately for studies providing OS and DFS/PFS/RFS, were derived using the Mantel-Haenszel method. Further analyses for exploring heterogeneity were comprehensively conducted through subgroup analysis, sensitivity analyses, and meta-regression. Heterogeneity was assessed using the χ2 test and expressed as the I2 index (25% = low, 50% = medium, 75% = high) 35. A random effects model was used when heterogeneity was > 50%. Alternatively, a fixed effects model was conducted for the meta-analysis. Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of funnel plots, combined with Egger's test or Begg's test 36,37. Additionally, we applied Duval and Tweede's trim and fill method to estimate corrected effect size after adjustment for publication bias 38. A set of modified predefined criteria was utilized to evaluate the risk of bias in eligible studies 39-41. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study characteristics

Our literature search identified 401 potentially relevant records. Eighty-nine articles were further removed due to duplication. Two-hundred and fifteen studies with irrelevant content were excluded after screening titles and abstracts. Ninety-seven articles were reviewed with full texts. In total, forty-nine studies consisting of 19,790 patients were finally included in our analysis according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 1) 42-47,23,48,11,49,27,28,19,50-52,12,53,24,54,25,55,29,13,26,14,15,20,10,21,56,16,57-62,30,63-66,22,67,17,68,18,69.

Fig 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process.

The characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. OS and DFS/PFS/RFS were reported in 45 and 26 articles, respectively. Sixteen different solid cancer types and five different hematological malignancies were investigated in the eligible studies. For solid tumors, the most frequently evaluated cancer was upper gastrointestinal cancer (UGI) (including patients with pancreatic, esophageal, and gastric cancer) (n = 8), followed by hepatic cancer (HCC) (n = 4), non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (n = 4), colorectal cancer (CRC) (n = 3), breast cancer (n = 3), and glioma (n = 3). Multiple myeloma (MM) (n = 5) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (n = 2) were the most-studied diseases among hematological malignancies. A large number of studies (90%) enrolled patients with mixed-stage, whereas only a few studies specifically investigated patients with early- (10%) and advanced-stage (12%) disease. Five different methods for defining cut-off values were observed in the included studies. Region under the curve (ROC) analysis was used most frequently (n = 23), followed by the upper limit of reference range (n = 12) and empirical values based on previous studies (n = 6). With respect to cut-off values, most studies (94%) selected coefficient of variation (CV) to evaluate RDW, whereas others used standard deviation (SD). The cut-off values ranged from 12.20% to 20.00%. However, thirty-six studies (80%) applied cut-off values in the range of 13-15%. Furthermore, we evaluated the demographic characteristics among the cohorts, such as age, gender, and country of origin. Twenty-two studies (52%) enrolled elderly population, the median or mean age of whom was > 60 years. The number of cohorts with balanced gender composition (n = 22) was nearly equal to that of cohorts with female or male dominant composition (n = 24). Sixty-three percent cohorts were originally from Asian countries, whereas the others were from Western countries. In our assessment of study quality, nine studies had quality scores ≤ 7, and the remaining 40 studies had scores > 7 (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 1.

Main characteristics of 49 eligible studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Study, Year | Country | Tumor type | Study design | Stage | Criteria | Sample size | Agea | Gender (Female/male) | Definition of cut-offs | Cut-offs value | Outcome measures | HRs source | variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perlstein et al 2009 |

USA | NR | prospective | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 4th quartile | 14.35% | OS | UV | |

| Koma et al 2013 |

Japan | Lung cancer | retrospective | I-IV | UICC-7 | 332 | 71.5 (38-94) | 109/223 | Upper limit | 15.00% | OS | UV; MV | RDW; Stage; ECOG PS; Other diseases; Treatment; Albumin; CRP |

| Abakay et al 2014 |

Turkey | Malignant mesothelioma | retrospective | NR | NR | 152 | 58.2 ± 11.9 | 65/90 | Arbitraryc | 20.00% | OS | MV | RDW; Histopathological subtype; NLR |

| Lee et al 2014 |

Korea | MM | retrospective | I-III | ISS | 146 | 61 (32-83) | 55/91 | Upper limit | 14.50% | OS; PFS | UV; MV | RDW; Age at diagnosis; ECOG; Cytogenetic risk; B2MG; Albumin; LDH; Hemoglobin; Calcium; Induction with novel agents; ASCT |

| Riedl et al 2014 |

Austria | Multiple malignanciesb | prospective | Localized; Distant metastasis; Not classifiable | NR | 1840 | 62 (52-68) | 843/997 | Upper limit; 4th quartile | 16%; 14.6% | OS | UV; MV | RDW; Age; Sex |

| Wang et al 2014 |

China | RCC | retrospective | I-IV | AJCC-7 | 316 | 56.83 ± 11.68 | 108/210 | ROC | 12.85% | OS | MV | RDW; Smoking; Hemoglobin; MCV; Platelet; WBC; Albumin; ESR |

| Warwick et al 2014 |

UK | NSCLC | retrospective | T1-3; N0-1 | AJCC-7 | 917 | 67.21 (17-90) | 440/477 | 4th quartile | 15.30% | OS | MV | RDW; Age; Alcohol intake; Emphysema; Squamous carcinoma; predicted postoperative FEV1; T stage I; T stage III; N stage I |

| Yao et al 2014 |

China | Breast cancer | retrospective | Tis-T3; N0-3 |

NR | 608 | 52.4 ± 10.8 | 608/0 | ROC | 13.45% | OS | MV | RDW; Node stage; Molecular subtype; NLR |

| Chen et al 2015 |

China | ESCC | retrospective | T1-4; N0-3 | NR | 277 | NR | 37/240 | Mean | 14.50% | CSS | MV | RDW; Tumor length; Vessel invasion; Differentiation; T stage; N stage |

| Cheng et al 2015 |

Taiwan | UTUC | retrospective | Tis-T4; N0-+ |

AJCC-6 | 420 | 68 ± 10.3 | 116/79 | Within central 80 % distribution. | 14.00% | OS; CSS | UV; MV | RDW; T stage; LN metastasis; Tumor grade; Adjuvant chemotherapy; WBC; NLR |

| Iriyama et al 2015 |

Japan | CML | retrospective | NR | NR | 84 | 51 (22-85) | 30/54 | Arbitraryc | 15.00% | OS; EFS | UV | |

| Periša et al 2015 |

Croatia | DLBL | retrospective | I-IV | Ann Arbor | 81 | 64.0 (52.5-72.5) | 52/29 | ROC | 15.00% | OS; EFS | MV | RDW; Age; Sex; IPI; LDH; Clinical stage AA; ECOG PS |

| Smirne et al 2015 |

Italy | HCC | retrospective | A-D | BCLC | 314 | Training cohort 70 (62-77); Validation cohort 67 (59-74) | Training cohort 52/156; Validation cohort 26/80 | Upper limit | 14.60% | OS | MV | RDW; Age at diagnosis; BCLC stage; Child-Pugh-Turcotte score; tumor size; serum AFP |

| Wang et al 2015 |

USA | Breast cancer | retrospective | I-IV | AJCC-6 | 1816 | Black 57.26 ± 13.99; White 60.05 ± 13.43 | 1816/0 | NR | 14.50% | OS | MV | RDW; Age; Year of diagnosis; Ethnicity; Smoking status, Drinking status; Stage; Grade; Estrogen receptor status; progesterone receptor status |

| Xie et al 2015 |

USA | SCLC | prospective | Extensive; Limited | NR | 938 | 65.4 ± 11.0 | 438/500 | Upper limit | 15.00% | OS | UV; MV | RDW; NLR; PLR; Age at diagnosis; Gender; ECOG performance status; Chest radiation; Chemotherapy; Liver metastases; Numbers of metastatic sites |

| Auezova et al 2016 |

Kazakhstan | Gliomas | retrospective | Grade I-IV | WHO 2007 | 178 | 41.58 ± 1.04 | 85/93 | ROC | 13.95% | OS | UV | |

| Hirahara et al 2016 |

Japan | ESCC | retrospective | I-III | AJCC-7 | 144 | NR | 15/129 | Upper limit | 50fL | CSS | UV; MV | RDW; Stage; Tumor size; Operation time |

| Huang et al 2016 |

China | Breast cancer | retrospective | I-III | AJCC-6 | 203 | 37 (24-40) | 203/0 | ROC | 13.75% | OS; DFS | MV | RDW; PVI present; PR positive; Stage |

| Ichinose et al 2016 |

Japan | NSCLC | retrospective | T1-4; N0-2 | UICC-7 | 992 | NR | NR | Median | 13.80% | OS; DFS | MV | RDW; Gender; T factor; N factor; Sub-lobar resection; CEA; NLR; Albumin; Smoking |

| Kara et al 2016 |

Turkey | Laryngeal carcinoma | retrospective | T1-4; N0-2; M0 | AJCC-7 | 103 | 65.01 ± 9.01 | NR | ROC | 14.05% | OS | MV | RDW; Tumor stage |

| Kos et al 2016 |

Turkey | NSCLC | retrospective | I-IV | UICC-7 | 146 | 56.5 (26-83) | 15/131 | Median; ROC; Upper limit; Arbitraryc | 14%; 14.2%; 14.5%; 15% |

OS | UV | |

| Liang et al 2016 |

China | Glioblastoma | retrospective | NR | NR | 109 | 54 (19-85) | 42/67 | ROC | 14.10% | OS | MV | RDW; Age; Tumor location; Extent of resection; Adjuvant radio/chemotherapy; MCV; MCHC |

| Podhorecka et al 2016 |

Poland | CLL | retrospective | 0-IV | Rai | 66 | 63 (38-85) | 25/38 | Upper limit | 14.50% | OS | UV | |

| Sun et al 2016 |

China | ESCC | retrospective | I-III | AJCC-6 | 362 | Median 58; Mean 57.96 | 94/268 | ROC | 13.60% | OS; DFS | UV | |

| Uysal et al 2016 |

Turkey | NSCLC | retrospective | IA-IIIA | NR | 249 | 60.8 ± 9.1 | 41/208 | Upper limit | 14.60% | OS; DFS | UV | |

| Wan et al 2016 |

China | ESCC | retrospective | I-III | AJCC/ UICC-7 |

179 | 63.0 (42-77) | 29/150 | Upper limit | 15.00% | OS; DFS | MV | RDW; Stage (III vs. I&II); Node metastasis status; Tumor length; WBC; Albumin; CRP; NLR |

| Zhang et al 2016 |

China | ESCC | retrospective | I-III | AJCC-7 | 468 | 59.5 ± 9.0; 60 (36-81) |

92/376 | ROC | 12.20% | OS; DFS | MV | RDW; Age; N metastasis; Adjuvant radio/chemotherapy; Smoking; Maximum tumor diameter; MCV; CA19-9; NLR; PLR; COP-MPV |

| Zhao et al 2016 |

China | HCC | retrospective | I-IV | NR | 106 | 52 (22-75) | 13/93 | Upper limit | 14.50% | OS; DFS | MV; UV | RDW; TNM stage; Tumor size; Tumor number; Vascular invasion |

| Cheng et al 2017 |

China | GC | retrospective | I-IV | AJCC-7 | 227 | NR | 51/176 | Median | 13.00% | OS; DFS | UV | |

| Howell et al 2017 |

Japan, Italy and UK | HCC | prospective | A-D | BCLC; CLIP scores | 442 | 69.92 ± 10.06 | 96/346 | NR | NR | OS | MV | Treatment-naïve HCC; NLR; CLIP score; Diarrhea on sorafenib; RDW |

| Hu et al 2017 |

China | ESCC | retrospective | I-III | AJCC/ UICC-7 |

2396 | Male 55.98 ± 9.81; Female 57.93 ± 9.41 | 574/1822 | NR | NR | OS | MV | Age, body mass index, smoking, drinking, family history of cancer, systolic blood pressure, fasting blood glucose, TNM stage, tumor embolus and tumor size |

| Kust et al 2017 |

Croatia | CRC | retrospective | I-IV | AJCC-7 | 90 | 66.8 ± 9.7 | 37/53 | ROC | 14.00% | OS | MV | RDW; Age; Gender; AJCC stage; NLR |

| Li B et al 2017 |

China | Hilar cholangiocarcinoma | retrospective | I-IV | AJCC-7 | 292 | 60 (20-78) | 131/161 | ROC | 14.95% | OS | MV | RDW; Histologic grade; T stage; N stage; AJCC stage; Portal vein invasion; Hepatic artery invasion |

| Li Z et al 2017 |

USA | Epithelial ovarian cancer | retrospective | I-IV | NR | 654 | 63 (28-93) | 654/0 | ROC | 14.15% | OS | MV | RDW; NLR; PLR; MLR; Combined RDW+NLR; Stage; Origin of cancer; Age; Histology; Grade; Residual disease |

| Luo et al 2017 |

China | Nasal-type, extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma | retrospective | I-IV | Ann Arbor | 191 | 44 (15-86) | 57/134 | ROC | 46.2 fL | OS; PFS | MV | RDW; Local invasiveness; Hemoglobin |

| Meng et al 2017 |

China | MM | retrospective | I-III | DSS | 166 | 61.6 ± 10.8 | 78/88 | Arbitraryc | 14.00% | OS; PFS | UV | |

| Sun et al 2017 |

China | Prostate cancer | retrospective | NR | NR | 171 | 68.5 ± 8.4 | 0/171 | ROC | 12.90% | OS | UV | |

| Tangthongkum et al 2017 |

Thailand | Oral cancer | retrospective | I-IV | AJCC-7 | 374 | 60 (21-92) | 133/241 | Arbitraryc | 14.05% | OS; DFS; RFS | UV; MV | RDW; Stage; PLR |

| Wang et al 2017 |

China | MM | retrospective | I-III | ISS | 196 | 65 (33-82) | 86/110 | ROC | 18.05% | OS | MV | RDW; Age; gender; Albumin; Lactate dehydrogenase; Creatinine |

| Xu et al 2017 |

China | Glioma | retrospective | Low grade; High grade | WHO 2007 | 168 | 44.1 ± 14.6 | 168/0 | NR | 13.20% | PFS | UV | |

| Yazic et al 2017 |

Turkey | GC | retrospective | I-III | AJCC/ UICC-7 |

173 | 61.7 ± 12 | 62/110 | Mean | 16.00% | OS | MV | RDW; Gender; Age; Tumor diameter; Vascular invasion; PNI; Metastatic LN; PRBC; Complication; T1; PDW; MCV |

| Zheng et al 2017 |

China | Cervical cancer | retrospective | IA1-IIA2 | FIGO | 800 | 49.5 ± 10.7 | 800/0 | ROC | 12.70% | OS; DFS | UV | |

| Zhou et al 2017 |

China | DLBL | retrospective | I-IV | Ann Arbor | 161 | 59.1±11.4 | 70/91 | ROC | 14.10% | OS; PFS | MV | |

| Zhu et al 2017 |

China | HCC | retrospective | I-III | NR | 316 | 52.2 (22.0-80.0) | Training cohort 26/159; Validation cohort 20/111 | ROC | 13.25% | OS; DFS | MV; UV | RDW; FIB-4; NLR; PLR; Liver cirrhosis; Tumor size; Tumor capsule; Tumor thrombus; TNM stage |

| Życzkowski et al 2017 |

Poland | RCC | retrospective | I-IV | AJCC-7 | 434 | 62.0 (54.0-69.0) | 203/231 | ROC | 13.90% | CSS | MV | RDW; Age; Gender; T stage; Distant metastases; Nephrectomy; Tumor necrosis; Grading |

| Han et al 2018 |

China | CRC | retrospective | I-IV | NR | 128 | NR | 167/73 | ROC | 13.45% | OS; DFS | UV; MV | RDW; Differentiation; CA19‐9 |

| Ma et al 2018 |

China | MM | retrospective | I-III | ISS; DSS | 78 | 60.7 (43-81) | 31/47 | ROC | 15.50% | OS; PFS | UV | RDW; B symptoms; IPI; ECOG PS; LDH; Stage; Bone marrow involvement; Extranodal sites of disease; Hemoglobin |

| Zhang et al 2018 |

China | Rectal cancer | retrospective | I-III | AJCC-7 | 625 | NR | 241/384 | ROC | RDW-cv 14.1%; RDW-sd 48.2fL | OS; DFS | MV | RDW; Tumor location; Tumor size; Differentiation; TNM; Vascular invasion; Perineural invasion |

| Zhou et al 2018 |

China | MM | retrospective | I-III | ISS | 162 | 61 (40-87) | 75/87 | Upper limit | 14.00% | OS; PFS | UV |

Abbreviations: GC = gastric cancer; ESCC = esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; CRC = colorectal carcinoma; HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma; NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer; SCLC = small cell lung cancer; RCC = renal cell cancer; UTUC = Upper tract urothelial carcinoma; MM = multiple myeloma; chronic lymphocytic leukemia = CLL; CML = Chronic Myeloid Leukemia; DLBL = diffuse large B-cell lymphomas; AJCC = The American Joint Committee on Cancer; BCLC = Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer guidelines; UICC = International Union Against Cancer; DSS = Durie and Salmon staging system; ISS = International Staging System; OS = overall survival; PFS = progression free survival; RFS = recurrence free survival; DFS = disease free survival; event-free survival = EFS; MV = multivariate; UV = univariate; RDW-CV = red blood cell distribution width coefficient of variation; RDW-SD = red blood cell distribution width standard deviation; NR = not reported

a. Age reported as either mean ± standard deviation or median (range), if not otherwise specified.

b. Multiple malignancies include brain, breast, lung, upper or lower gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, kidney, prostate or gynecological system; sarcoma and hematologic malignancies (lymphoma, multiple myeloma)

c. Studies defined cut-offs value based on previous studies.

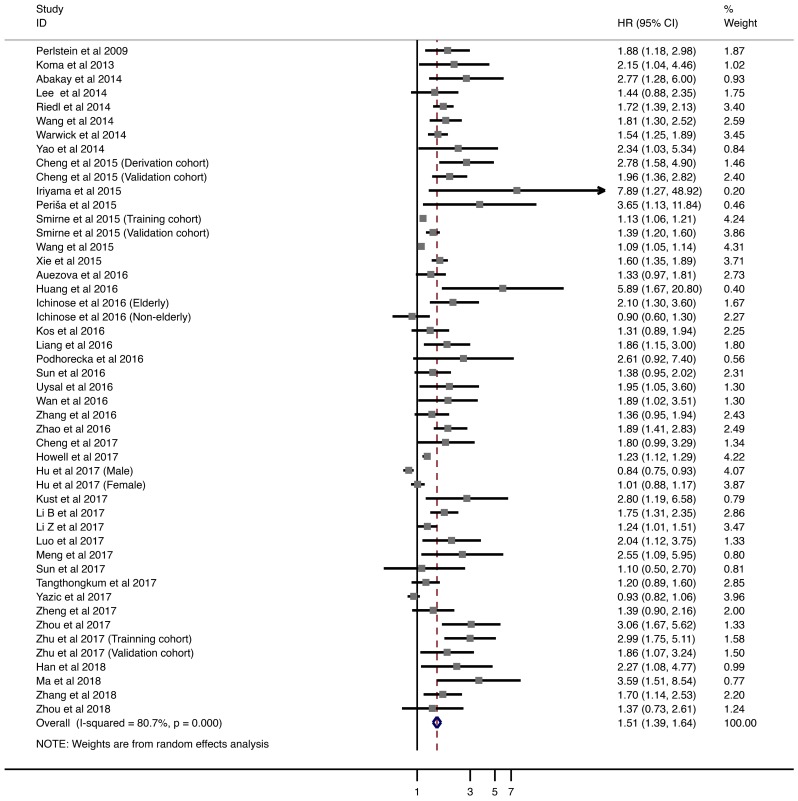

Overall survival

Forty-five studies with 18,767 patients were analyzed for OS. The pooled HRs of higher pretreatment RDW level was 1.508 (95% CI = 1.387-1.639; Fig. 2). Next, we performed comprehensive analysis to explore the high heterogeneity, including subgroup analyses, sensitivity analysis, and meta-regression.

Fig 2.

Meta-analysis of the association between RDW and OS in patients. Results are presented as individual and pooled hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Table 2 shows the subgroup analysis of the included studies, based on eight factors, including tumor type, tumor stage, age, gender distribution, country of origin, cut-off value, method of defining the cut-off value, and HR calculation. In solid tumors, CRC had the strongest relationship with poor OS (HR = 1.932; 95% CI = 1.397-2.673), followed by HCC (HR = 1.430; 95% CI = 1.232-1.660) and NSCLC (HR = 1.440; 95% CI = 1.103-1.880). However, UGI cancer and breast cancer with elevated RDW were not associated with worse OS (UGI cancer: HR = 1.091; 95% CI = 0.925-1.286. Breast cancer: HR = 2.092, 95% CI = 0.833-5-255). For hematological malignancies, negative OS outcomes were observed in MM and DLBCL (MM: HR = 1.692; 95% CI = 1.256-2.281. DLBCL: HR = 3.178, 95% CI = 1.853-5.450). In addition, patients in either early or advanced stage showed adverse relationship between increased pretreatment RDW and poor OS. Furthermore, combined HR remained significant in subgroups stratified by demographic factors, including age, gender, and country of origin. Studies with cut-off values between 13% and 14% had worse HR than others. However, considerable variety was present in the methodologies used for defining cut-off values. ROC analysis was the most widely used method and had relatively closer relationship with poorer HRs. Finally, studies using univariate (HR = 1.525; 95% CI = 1.380-1.686) and multivariate analyses (HR = 1.477; 95% CI = 1.342-1.626) showed that higher RDW levels were associated worse OS.

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses of the associations between RDW and OS in cancer.

| Stratified analyses | No. of patients | No. of studies | Model | Pooled HR (95%CI) | P value | PD value | Heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 | PH value | |||||||

| Tumor type | <0.001 | |||||||

| Hematologic malignancies | 1979 | 10 | fixed | 2.046 (1.623-2.580) | <0.001 | 21.2% | 0.248 | |

| MM | 748 | 5 | fixed | 1.692 (1.256-2.281) | 0.001 | 18.8% | 0.295 | |

| DLBCL | 881 | 2 | fixed | 3.178 (1.853-5.450) | <0.001 | 0.0% | 0.793 | |

| UGI cancer | 3805 | 6 | random | 1.091 (0.925-1.286) | 0.303 | 73.4% | 0.001 | |

| HCC | 1510 | 5 | random | 1.430 (1.232-1.660) | <0.001 | 79.9% | <0.001 | |

| NSCLC | 2304 | 4 | random | 1.440 (1.103-1.880) | 0.007 | 57.2% | 0.053 | |

| Breast cancer | 2627 | 3 | random | 2.092 (0.833-5.255) | 0.116 | 80.3% | 0.006 | |

| Colorectal carcinoma | 843 | 3 | fixed | 1.932 (1.397-2.673) | <0.001 | 0.0% | 0.521 | |

| Gliomas | 287 | 2 | fixed | 1.466 (1.129-1.904) | <0.001 | 23.9% | 0.252 | |

| UTUC | 420 | 1* | fixed | 2.172 (1.599-2.949) | <0.001 | 3.5% | 0.309 | |

| Stage | <0.001 | |||||||

| Mix stage | 16786 | 33 | random | 1.494 (1.372-1.626) | <0.001 | 80.5% | <0.001 | |

| Early stage | 1545 | 5 | fixed | 1.690 (1.180-2.422) | 0.004 | 41.0% | 0.148 | |

| Advanced Stage | 1416 | 6 | random | 1.717 (1.235-2.386) | 0.001 | 57.7% | 0.038 | |

| Age | <0.001 | |||||||

| ≤60 | 7979 | 19 | random | 1.590 (1.321-1.914) | <0.001 | 82.6% | <0.001 | |

| >60 | 7992 | 22 | random | 1.515 (1.351-1.699) | <0.001 | 75.7% | <0.001 | |

| Gender distribution | <0.001 | |||||||

| Female dominant | 5059 | 9 | random | 1.401 (1.153-1.703) | 0.001 | 74.9% | 0.001 | |

| Balanced | 6418 | 21 | random | 1.696 (1.441-1.997) | <0.001 | 74.8% | <0.001 | |

| Male dominant | 5325 | 14 | random | 1.413 (1.232-1.620) | <0.001 | 81.6% | <0.001 | |

| Country | <0.001 | |||||||

| Eastern | 10608 | 28 | random | 1.716 (1.458-2.020) | <0.001 | 79.8% | <0.001 | |

| Western | 8180 | 17 | random | 1.316 (1.203-1.439) | <0.001 | 80.9% | <0.001 | |

| Cut-off value | <0.001 | |||||||

| >15% | 3356 | 6 | random | 1.608 (1.107-2.335) | 0.013 | 89.5% | <0.001 | |

| >14% and ≤ 15% | 7911 | 21 | random | 1.510 (1.351-1.688) | <0.001 | 79.2% | <0.001 | |

| >13% and ≤ 14% | 3409 | 11 | random | 1.869 (1.493-2.340) | <0.001 | 57.5% | 0.004 | |

| ≤13% | 1982 | 5 | fixed | 1.534 (1.262-1.865) | <0.001 | 0.0% | 0.655 | |

| Definition of cut-off value | <0.001 | |||||||

| ROC curve analysis | 6276 | 22 | fixed | 1.569 (1.434-1.718) | <0.001 | 42.6% | 0.015 | |

| Upper limit | 3558 | 11 | random | 1.504 (1.296-1.746) | <0.001 | 70.8% | 0.000 | |

| Median | 2357 | 3 | random | 1.400 (0.961-2.040) | 0.080 | 62.4% | 0.046 | |

| 4th quartile | 2757 | 3 | random | 1.647 (1.430-1.897) | <0.001 | 0.0% | 0.645 | |

| Arbitrary# | 922 | 5 | random | 1.682 (1.073-2.638) | 0.023 | 63.2% | 0.028 | |

| HR calculation‡ | <0.001 | |||||||

| Multivariate | 13572 | 28 | random | 1.477 (1.342-1.626) | <0.001 | 83.9% | <0.001 | |

| Univariate | 4275 | 17 | fixed | 1.525 (1.380-1.686) | <0.001 | 8.5% | 0.355 | |

Abbreviations: MM = Multiple Myeloma; DLBCL = Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; UGI cancer = upper gastrointestinal tract (UGI) cancers (including esophagus cancer, gastric cancer, and small intestine cancer); HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma; NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer; UTUC = upper tract urothelial carcinoma; OS = overall survival; HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; PD = P for subgroup difference; PH = P for heterogeneity.

*: Cheng et al 2015 separately evaluated the survival outcome in two cohorts, which were derivation cohort and validation cohort.

#: Definition of cut-offs value of RDW was based on previous study.

‡: HRs were extracted from multivariate cox proportional hazards models, univariate cox proportional hazards models or survival curve analysis.

In sensitivity analysis under “one study removed” model, the pooled HRs for OS were significantly affected by exclusion of Wang et al. (Supplementary Table 4). In addition, meta-regression did not demonstrate any potential source of heterogeneity (Supplementary Table 5).

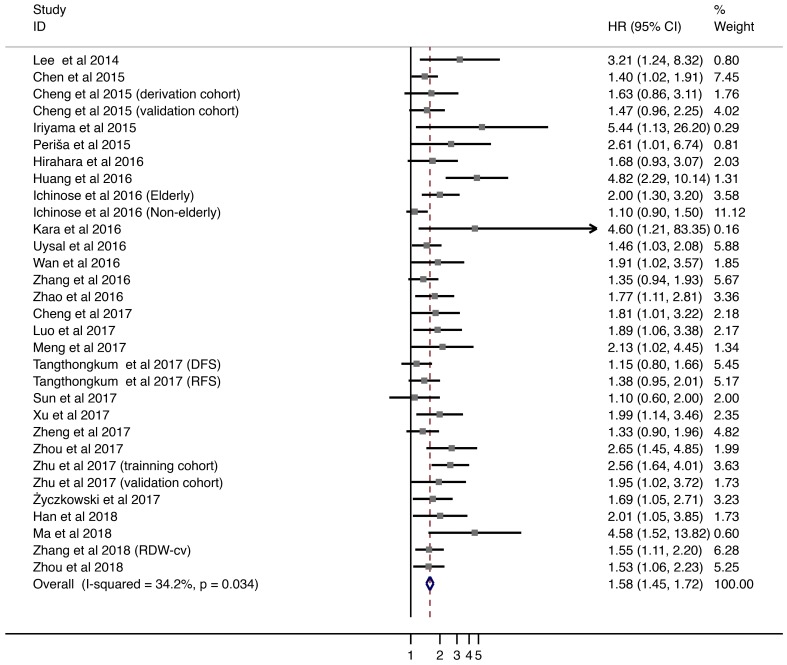

DFS/PFS/RFS

Twenty-six studies with 7,350 patients provided HRs and 95% CIs for DFS/PFS/RFS. Overall, elevated pretreatment RDW level were associated with worse DFS/PFS/RFS (HR = 1.576; 95% CI = 1.447-1.716; Fig. 3). Subgroup analyses were performed by stratification based on tumor type, tumor stage, age, gender distribution, country of origin, cut-off value, method of defining the cut-off value, and HR calculation (Supplementary Table 2). Higher levels of RDW were associated with shorter DFS/PFS/RFS in patients with HCC (HR = 2.104, 95% CI = 1.577-2.807), CRC (HR = 1.636; 95% CI = 1.211-2.211), and hematological malignancies (HR = 2.077; 95% CI = 1.644-2.625).

Fig 3.

Meta-analysis of the association between RDW and DFS/PFS/RFS in patients. Results are presented as individual and pooled hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Overall, HRs remained significant in subgroups stratified by demographic factors, including age, gender, and country of origin. Furthermore, associations between higher RDW levels and worse DFS/PFS/RFS were also observed with cut-off values > 13% and < 14% (HR = 1.818; 95% CI = 1.474-2.243). Studies which utilized ROC analysis to define cut-off values showed comparatively worse HRs (HR = 1.770; 95% CI = 1.536-2.040). Finally, both univariate and multivariate analyses for HR calculation indicated poor DFS/PFS/RFS outcomes.

Publication bias

We observed evidence of publication bias in studies provided on OS (n = 45) and DFS/PFS/RFS (n = 26) by visual inspection of the funnel plot (Supplementary Fig. 1), which was further confirmed by Egger's tests (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 2). The trim and fill method was applied to address these problems. Intriguingly, pooled adjusted HRs of OS and DFS/PFS/RFS subsets were consistent with our primary analysis (Supplementary Table 6 and Supplementary Fig. 3).

Discussion

RDW is an easily acquired, non-invasive, and inexpensive maker, which can be used routinely for clinical purpose. This is the first meta-analysis to comprehensively evaluate the prognostic role of RDW in cancers. High RDW level was correlated with unfavorable clinical outcomes in most tumor types and stages. The prognostic value of RDW was also independent of patient age, gender, or region.

Gradual increase in RDW with age has been reported in healthy people 1. However, association between gender and RDW is still unclear. Certain studies indicated that RDW was slightly higher in females 70,71, whereas others observed no significant gender-based difference in RDW values 72,73. Hence, an age- and gender-stratified subgroup analysis was performed. Poor survival outcome was associated with higher RDW in elder or younger patients with cancer. Similarly, both females and males with high RDW levels exhibited poor survival. These results showed that RDW can predict survival independent of age and gender. The cut-off value of 14.6% is conventionally used for anemia 74. However, the lack of unified RDW cutoff values for cancer survival prediction was a matter of concern 73.

Majority of the studies used ROC analysis to define cut-off values, which ranged from 12.20% to 20.00%. However, 36 studies (80%) applied cut-off values between 13% and 15%. We observed that cut-off values defined by ROC curves were more likely to predict poor clinical outcomes. Furthermore, subgroups with cut-off values between 13% and 14% were mostly negatively associated with poor OS and DFS/PFS/RFS. We conclude that more studies are required to determine uniform cut-off values in specific cancer types.

The mechanisms underlying the prognostic impact of RDW on cancers were due to inflammation 75, poor nutritional status 76, and oxidative stress 77. First, it is well-known that malignant tumors are accompanied by systemic inflammatory response 76. RDW was identified as an inflammatory marker in patients with cancer due to its positive association with widely used plasma inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) 43,28,14, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 60,47, and interleukin (IL)-6 78 levels. Elevated RDW level reflected the presence of immature juvenile red blood cells in the periphery. Various cytokines affect erythropoiesis via erythropoietin (EPO) production, inhibition of erythroid progenitors, and reduction in iron release. Previous in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that EPO production was inhibited by inflammatory cytokines 79-81 such as IL-6, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). In addition, IL-1α and IL-1β play important roles in suppression of erythroid progenitors 82. Hepcidin, a regulator of iron metabolism, is increasingly expressed when plasma IL-6 level is elevated 83,84, which results in iron deficiency and anemia 80. In sum, it is plausible to hypothesize that RDW can reflect inflammatory status in cancer. Second, malnutrition is another hallmark of cancer because of reduction in appetite and weight. This results in deficiency of various minerals and vitamins such as iron, folate and vitamin B12, which consequently contribute to the increase in RDW 85,42. Numerous studies have also shown that low albumin level is associated with increased RDW level in cancer patients 24,60,30,69, which also indicated the relationship between high RDW level and poor nutritional status in patients with cancer. Third, oxidative stress was recognized as a negative factor leading to significant variation in erythrocyte size. Free reactive oxygen species (ROS) can damage protein, lipids, and DNA, which may reduce RBC survival 86. Taken together, high RDW level is well-suited to reflect both chronic ongoing inflammation and poor nutritional status in patients with cancer.

Among solid tumors, CRC and HCC showed relatively strong association between RDW level and negative prognosis. This significant association in CRC may be attributed to chronic inflammatory status and cancer-associated anemia. CRC can develop from inflammatory bowel diseases and inflamed polyps 87-89. Thus, inflammation plays a crucial role in colorectal carcinogenesis 90. In addition, chronic blood loss is a common symptom of CRC, which can lead to iron deficiency, anemia, and subsequent rise in RDW values. HCC is one of the most important inflammation-associated cancers 91; it is closely associated with chronic inflammation and fibrosis, which is known as hepatic inflammation-fibrosis-cancer (IFC) axis. IL-6 and TNF-α expression was elevated and erythrocyte maturation was suppressed in patients with HCC 92. Furthermore, within the diseased liver, free radicals such as ROS and nitrogen species (NO) were generated by the cells of the hepatic immune system, including recruited neutrophils, monocytes, and Kupffer Cells 92. In sum, elevated RDW was negatively associated with the prognosis of certain cancer types, which encompassed multiple pathways affecting erythropoiesis.

In our meta-analysis, pretreatment RDW was identified as a robust predictor of cancer prognosis. However, there are several limitations. First, there was considerable heterogeneity when HRs for OS outcomes were pooled. However, subgroup analysis showed that various methodologies for defining cut-off values may be a major cause of heterogeneity. The robustness of our results was further confirmed by sensitivity analysis and meta-regression, which did not significantly alter the pooled effect size for OS. Second, we observed that some studies evaluated the relationship between delta RDW level 17,27,16 or delta MCV level 93-96 and cancer prognosis after the patients had undergone certain therapies. However, we focused on the prognostic role of absolute value of pretreatment RDW level in this analysis as delta RDW level may be dependent on many cofactors such as therapies and types of cancer. Finally, although pretreatment RDW level can reflect both inflammatory and nutritional status, it would be more convincible if combined with other potential predictors, such as neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and prognostic nutritional index (PNI). More studies are required for building a new prognostic and comprehensive model for predicting survival outcomes in patients with cancer.

Conclusions

Pretreatment RDW level is a potential predictor of cancer prognosis, independent of most tumor type and stage and patient age and gender. Optimal RDW cut-off values can be defined by ROC analysis. Cut-off values between 13% and 14% were negatively associated with poor survival outcomes. Uniform cut-off values for specific cancer types are required for further evaluation in future.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and tables.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Key Technology Research and Development Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (No. 2014BAI04B01).

Author contributions

Conception and design: Chang-xiang Yan, Ning Liu; Collection and assembly of data: Peng-fei Wang, Si-ying Song; Data analysis and interpretation: All authors; Manuscript writing: All authors; Final approval of manuscript: All authors; Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors.

References

- 1.Salvagno GL, Sanchis-Gomar F, Picanza A, Lippi G. Red blood cell distribution width: A simple parameter with multiple clinical applications. Critical reviews in clinical laboratory sciences. 2015;52:86–105. doi: 10.3109/10408363.2014.992064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felker GM, Allen LA, Pocock SJ, Shaw LK, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA. et al. Red cell distribution width as a novel prognostic marker in heart failure: data from the CHARM Program and the Duke Databank. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;50:40–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montagnana M, Cervellin G, Meschi T, Lippi G. The role of red blood cell distribution width in cardiovascular and thrombotic disorders. Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine. 2011;50:635–41. doi: 10.1515/cclm.2011.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiong XF, Yang Y, Chen X, Zhu X, Hu C, Han Y. et al. Red cell distribution width as a significant indicator of medication and prognosis in type 2 diabetic patients. Sci Rep. 2017;7:2709. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02904-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tham T, Bardash Y, Teegala S, Herman WS, Costantino PD. The red cell distribution width as a prognostic indicator in upper aerodigestive tract (UADT) cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Otolaryngol; 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu L, Li M, Ding Y, Pu L, Liu J, Xie J. et al. Prognostic value of RDW in cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:16027–35. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang D, Quan W, Wu J, Ji X, Dai Y, Xiao W. et al. The value of red blood cell distribution width in diagnosis of patients with colorectal cancer. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry. 2018;479:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2018.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin YY, Wu YY, Xian XY, Qin JQ, Lai ZF, Liao L. et al. Single and combined use of red cell distribution width, mean platelet volume, and cancer antigen 125 for differential diagnosis of ovarian cancer and benign ovarian tumors. J Ovarian Res. 2018;11:10. doi: 10.1186/s13048-018-0382-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng S, Han F, Wang Y, Xu Y, Qu T, Ju Y. et al. The red distribution width and the platelet distribution width as prognostic predictors in gastric cancer. BMC gastroenterology. 2017;17:163. doi: 10.1186/s12876-017-0685-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen GP, Huang Y, Yang X, Feng JF. A Nomogram to Predict Prognostic Value of Red Cell Distribution Width in Patients with Esophageal Cancer. Mediators of inflammation. 2015;2015:854670. doi: 10.1155/2015/854670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirahara N, Matsubara T, Kawahara D, Mizota Y, Ishibashi S, Tajima Y. Prognostic value of hematological parameters in patients undergoing esophagectomy for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2016;21:909–19. doi: 10.1007/s10147-016-0986-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun P, Zhang F, Chen C, Bi X, Yang H, An X. et al. The ratio of hemoglobin to red cell distribution width as a novel prognostic parameter in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective study from southern China. Oncotarget. 2016;7:42650–60. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wan GX, Chen P, Cai XJ, Li LJ, Yu XJ, Pan DF. et al. Elevated red cell distribution width contributes to a poor prognosis in patients with esophageal carcinoma. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry. 2016;452:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang F, Chen Z, Wang P, Hu X, Gao Y, He J. Combination of platelet count and mean platelet volume (COP-MPV) predicts postoperative prognosis in both resectable early and advanced stage esophageal squamous cell cancer patients. Tumour biology: the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2016;37:9323–31. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4774-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kust D, Lucijanic M, Urch K, Samija I, Celap I, Kruljac I. et al. Clinical and prognostic significance of anisocytosis measured as a red cell distribution width in patients with colorectal cancer. QJM: monthly journal of the Association of Physicians. 2017;110:361–7. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcw223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han F, Shang X, Wan F, Liu Z, Tian W, Wang D. et al. Clinical value of the preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and red blood cell distribution width in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:3339–49. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X, Wu Q, Hu T, Gu C, Bi L, Wang Z. Elevated red blood cell distribution width contributes to poor prognosis in patients undergoing resection for nonmetastatic rectal cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e9641. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smirne C, Grossi G, Pinato DJ, Burlone ME, Mauri FA, Januszewski A. et al. Evaluation of the red cell distribution width as a biomarker of early mortality in hepatocellular carcinoma. Digestive and liver disease: official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 2015;47:488–94. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao T, Cui L, Li A. The significance of RDW in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after radical resection. Cancer Biomark. 2016;16:507–12. doi: 10.3233/CBM-160591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howell J, Pinato DJ, Ramaswami R, Arizumi T, Ferrari C, Gibbin A. et al. Integration of the cancer-related inflammatory response as a stratifying biomarker of survival in hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib. Oncotarget. 2017;8:36161–70. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu Y, Li JH, Yang J, Gao XM, Jia HL, Yang X. Inflammation-nutrition scope predicts prognosis of early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e8056. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warwick R, Mediratta N, Shackcloth M, Shaw M, McShane J, Poullis M. Preoperative red cell distribution width in patients undergoing pulmonary resections for non-small-cell lung cancer. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery: official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2014;45:108–13. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ichinose J, Murakawa T, Kawashima M, Nagayama K, Nitadori JI, Anraku M. et al. Prognostic significance of red cell distribution width in elderly patients undergoing resection for non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of thoracic disease. 2016;8:3658–66. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2016.12.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kos M, Hocazade C, Kos FT, Uncu D, Karakas E, Dogan M. et al. Evaluation of the effects of red blood cell distribution width on survival in lung cancer patients. Contemporary oncology (Poznan, Poland) 2016;20:153–7. doi: 10.5114/wo.2016.60072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uysal S, Sahinoglu T, Kumbasar U, Demircin M, Pasaoglu I, Dogan R. The impact of red cell distribution width and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio on long-term survival after pulmonary resection for non-small cell lung cancer. UHOD - Uluslararasi Hematoloji-Onkoloji Dergisi. 2016;26:69–74. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iriyama N, Hatta Y, Kobayashi S, Uchino Y, Miura K, Kurita D. et al. Higher Red Blood Cell Distribution Width Is an Adverse Prognostic Factor in Chronic-phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients Treated with Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:5473–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perisa V, Zibar L, Sincic-Petricevic J, Knezovic A, Perisa I, Barbic J. Red blood cell distribution width as a simple negative prognostic factor in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a retrospective study. Croatian medical journal. 2015;56:334–43. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2015.56.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Podhorecka M, Halicka D, Szymczyk A, Macheta A, Chocholska S, Hus M. et al. Assessment of red blood cell distribution width as a prognostic marker in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Oncotarget. 2016;7:32846–53. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J, Xie X, Cheng F, Zhou X, Xia J, Qian X. et al. Evaluation of pretreatment red cell distribution width in patients with multiple myeloma. Cancer Biomark. 2017;20:267–72. doi: 10.3233/CBM-170032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med. 1998;17:2815–34. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981230)17:24<2815::aid-sim110>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miao C, Liang C, Zhu J, Xu A, Zhao K, Hua Y. et al. Prognostic role of matrix metalloproteinases in bladder carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:32309–21. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao Y, Si G, Zhu F, Hui J, Cai S, Huang C. et al. Prognostic role of platelet to lymphocyte ratio in hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:22854–62. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou LN, Tan Y, Li P, Zeng P, Chen MB, Tian Y. et al. Prognostic value of increased KPNA2 expression in some solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:303–14. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stuck AE, Rubenstein LZ, Wieland D. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Asymmetry detected in funnel plot was probably due to true heterogeneity. Bmj. 1998;316:469. author reply 70-1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–63. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayden JA, Cote P, Bombardier C. Evaluation of the quality of prognosis studies in systematic reviews. Annals of internal medicine. 2006;144:427–37. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-6-200603210-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mei Z, Liang M, Li L, Zhang Y, Wang Q, Yang W. Effects of statins on cancer mortality and progression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 95 cohorts including 1,111,407 individuals. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2017;140:1068–81. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altman DG. Systematic reviews of evaluations of prognostic variables. Bmj. 2001;323:224–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7306.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perlstein TS, Weuve J, Pfeffer MA, Beckman JA. Red blood cell distribution width and mortality risk in a community-based prospective cohort. Archives of internal medicine. 2009;169:588–94. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koma Y, Onishi A, Matsuoka H, Oda N, Yokota N, Matsumoto Y. et al. Increased red blood cell distribution width associates with cancer stage and prognosis in patients with lung cancer. PloS one. 2013;8:e80240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abakay O, Tanrikulu AC, Palanci Y, Abakay A. The value of inflammatory parameters in the prognosis of malignant mesothelioma. The Journal of international medical research. 2014;42(2):554–565. doi: 10.1177/0300060513504163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee H, Kong SY, Sohn JY, Shim H, Youn HS, Lee S, Kim HJ, Eom HS. Elevated red blood cell distribution width as a simple prognostic factor in patients with symptomatic multiple myeloma. BioMed research international. 2014;2014:145619. doi: 10.1155/2014/145619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riedl J, Posch F, Konigsbrugge O, Lotsch F, Reitter EM, Eigenbauer E, Marosi C, Schwarzinger I, Zielinski C, Pabinger I, Ay C. Red cell distribution width and other red blood cell parameters in patients with cancer: association with risk of venous thromboembolism and mortality. PloS one. 2014;9(10):e111440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang FM, Xu G, Zhang Y, Ma LL. Red cell distribution width is associated with presence, stage, and grade in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Disease markers. 2014;2014:860419. doi: 10.1155/2014/860419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yao M, Liu Y, Jin H, Liu X, Lv K, Wei H, Du C, Wang S, Wei B, Fu P. Prognostic value of preoperative inflammatory markers in Chinese patients with breast cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:1743–1752. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S69657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng YC, Huang CN, Wu WJ, Li CC, Ke HL, Li WM, Tu HP, Li CF, Chang LL, Yeh HC. The Prognostic Significance of Inflammation-Associated Blood Cell Markers in Patients with Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;23(1):343–351. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4781-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang C, Civan J, Lai Y, Cristofanilli M, Hyslop T, Palazzo JP, Myers RE, Li B, Ye Z, Zhang K, Xing J, Yang H. Racial disparity in breast cancer survival: the impact of pre-treatment hematologic variables. Cancer Causes and Control. 2015;26(1):45–56. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0481-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xie D, Marks R, Zhang M, Jiang G, Jatoi A, Garces YI, Mansfield A, Molina J, Yang P. Nomograms Predict Overall Survival for Patients with Small-Cell Lung Cancer Incorporating Pretreatment Peripheral Blood Markers. Journal of thoracic oncology: official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2015;10(8):1213–1220. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Auezova R, Ryskeldiev N, Doskaliyev A, Kuanyshev Y, Zhetpisbaev B, Aldiyarova N, Ivanova N, Akshulakov S, Auezova L. Association of preoperative levels of selected blood inflammatory markers with prognosis in gliomas. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:6111–6117. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S113606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang DP, Ma RM, Xiang YQ. Utility of Red Cell Distribution Width as a Prognostic Factor in Young Breast Cancer Patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(17):e3430. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kara M, Uysal S, Altinisik U, Cevizci S, Guclu O, Derekoy FS. The pre-treatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, and red cell distribution width predict prognosis in patients with laryngeal carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274(1):535–542. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-4250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liang RF, Li M, Yang Y, Mao Q, Liu YH. Significance of pretreatment red blood cell distribution width in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Medical Science Monitor. 2016;23:3217–3223. doi: 10.12659/MSM.905204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hu D, Lin X, Chen Y, Chang Q, Chen G, Li C, Zhang H, Cui Z, Liang B, Jiang W, Ji K, Huang J, Peng F, Zheng X, Niu W. Preoperative blood-routine markers and prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: The Fujian prospective investigation of cancer (FIESTA) study. Oncotarget. 2017;8(14):23841–23850. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li B, You Z, Xiong XZ, Zhou Y, Wu SJ, Zhou RX, Lu J, Cheng NS. Elevated red blood cell distribution width predicts poor prognosis in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8(65):109468–109477. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li Z, Hong N, Robertson M, Wang C, Jiang G. Preoperative red cell distribution width and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predict survival in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43001. doi: 10.1038/srep43001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luo H, Quan X, Song XY, Zhang L, Yin Y, He Q, Cai S, Li S, Zeng J, Zhang Q, Gao Y, Yu S. Red blood cell distribution width as a predictor of survival in nasal-type, extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8(54):92522–92535. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meng S, Ma Z, Lu C, Liu H, Tu H, Zhang W. et al. Prognostic Value of Elevated Red Blood Cell Distribution Width in Chinese Patients with Multiple Myeloma. Annals of clinical and laboratory science. 2017;47:282–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sun Z, Ju Y, Han F, Sun X, Wang F. Clinical implications of pretreatment inflammatory biomarkers as independent prognostic indicators in prostate cancer. Journal of clinical laboratory analysis; 2017. p. 32. (3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tangthongkum M, Tiyanuchit S, Kirtsreesakul V, Supanimitjaroenporn P, Sinkitjaroenchai W. Platelet to lymphocyte ratio and red cell distribution width as prognostic factors for survival and recurrence in patients with oral cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274(11):3985–3992. doi: 10.1007/s00405-017-4734-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu W, Wang D, Zheng X, Ou Q, Huang L. Sex-dependent association of preoperative hematologic markers with glioma grade and progression. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2017;137(2):279–287. doi: 10.1007/s11060-017-2714-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yazici P, Demir U, Bozkurt E, Isil GR, Mihmanli M. The role of red cell distribution width in the prognosis of patients with gastric cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2017;18(1):19–25. doi: 10.3233/CBM-160668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zheng RR, Huang XX, Jin C, Zhuang XX, Ye LC, Zheng FY, Lin F. Preoperative platelet count improves the prognostic prediction of the FIGO staging system for operable cervical cancer patients. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry. 2017;473:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhou S, Fang F, Chen H, Zhang W, Chen Y, Shi Y, Zheng Z, Ma Y, Tang L, Feng J, Zhang Y, Sun L, Chen Y, Liang B, Yu K, Jiang S. Prognostic significance of the red blood cell distribution width in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8(25):40724–40731. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zyczkowski M, Rajwa P, Gabrys E, Jakubowska K, Jantos E, Paradysz A. The Relationship Between Red Cell Distribution Width and Cancer-Specific Survival in Patients With Renal Cell Carcinoma Treated With Partial and Radical Nephrectomy. Clin Genitourin Cancer; 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ma Y, Jin Z, Zhou S, Ye H, Jiang S, Yu K. Prognostic significance of the red blood cell distribution width that maintain at high level following completion of first line therapy in mutiple myeloma patients. Oncotarget. 2018;9(11):10118–10127. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhou D, Xu P, Peng M, Shao X, Wang M, Ouyang J. et al. Pre-treatment red blood cell distribution width provides prognostic information in multiple myeloma. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2018;481:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lippi G, Salvagno GL, Guidi GC. Red blood cell distribution width is significantly associated with aging and gender. Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine. 2014;52:e197–9. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2014-0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alis R, Fuster O, Rivera L, Romagnoli M, Vaya A. Influence of age and gender on red blood cell distribution width. Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine. 2015;53:e25–8. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2014-0756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Qiao R, Yang S, Yao B, Wang H, Zhang J, Shang H. Complete blood count reference intervals and age- and sex-related trends of North China Han population. Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine. 2014;52:1025–32. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2012-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hoffmann JJML, Nabbe KCAM, van den Broek NMA. Effect of age and gender on reference intervals of red blood cell distribution width (RDW) and mean red cell volume (MCV) Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (CCLM); 2015. p. 53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McPherson RA, Pincus MR. Henry's clinical diagnosis and management by laboratory methods. St Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Woodman RC, Bandinelli S, Lauretani F, Corsi AM. et al. Proinflammatory state and circulating erythropoietin in persons with and without anemia. The American journal of medicine. 2005;118:1288. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Semba RD, Patel KV, Ferrucci L, Sun K, Roy CN, Guralnik JM. et al. Serum antioxidants and inflammation predict red cell distribution width in older women: the Women's Health and Aging Study I. Clin Nutr. 2010;29:600–4. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.de Gonzalo-Calvo D, de Luxan-Delgado B, Rodriguez-Gonzalez S, Garcia-Macia M, Suarez FM, Solano JJ. et al. Interleukin 6, soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor I and red blood cell distribution width as biological markers of functional dependence in an elderly population: a translational approach. Cytokine. 2012;58:193–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pavese I, Satta F, Todi F, Di Palma M, Piergrossi P, Migliore A. et al. High serum levels of TNF-alpha and IL-6 predict the clinical outcome of treatment with human recombinant erythropoietin in anaemic cancer patients. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2010;21:1523–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Means RT Jr, Krantz SB. Inhibition of human erythroid colony-forming units by tumor necrosis factor requires beta interferon. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1993;91:416–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI116216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Means RT Jr, Krantz SB. Inhibition of human erythroid colony-forming units by gamma interferon can be corrected by recombinant human erythropoietin. Blood. 1991;78:2564–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Faquin WC, Schneider TJ, Goldberg MA. Effect of inflammatory cytokines on hypoxia-induced erythropoietin production. Blood. 1992;79:1987–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nemeth E, Rivera S, Gabayan V, Keller C, Taudorf S, Pedersen BK. et al. IL-6 mediates hypoferremia of inflammation by inducing the synthesis of the iron regulatory hormone hepcidin. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2004;113:1271–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI20945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pietrangelo A, Trautwein C. Mechanisms of disease: The role of hepcidin in iron homeostasis-implications for hemochromatosis and other disorders. Nature clinical practice Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2004;1:39–45. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Douglas SW, Adamson JW. The anemia of chronic disorders: studies of marrow regulation and iron metabolism. Blood. 1975;45:55–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Friedman JS, Lopez MF, Fleming MD, Rivera A, Martin FM, Welsh ML. et al. SOD2-deficiency anemia: protein oxidation and altered protein expression reveal targets of damage, stress response, and antioxidant responsiveness. Blood. 2004;104:2565–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Song CS, Park DI, Yoon MY, Seok HS, Park JH, Kim HJ. et al. Association between red cell distribution width and disease activity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2012;57:1033–8. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1978-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dawwas MF. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;370:2539–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1405329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, Zhao WK, Lee JK, Doubeni CA. et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;370:1298–306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lasry A, Zinger A, Ben-Neriah Y. Inflammatory networks underlying colorectal cancer. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:230–40. doi: 10.1038/ni.3384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Greten TF, Duffy AG, Korangy F. Hepatocellular carcinoma from an immunologic perspective. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:6678–85. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Stauffer JK, Scarzello AJ, Jiang Q, Wiltrout RH. Chronic inflammation, immune escape, and oncogenesis in the liver: a unique neighborhood for novel intersections. Hepatology. 2012;56:1567–74. doi: 10.1002/hep.25674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Arslan C, Aksoy S, Dizdar O, Kurt M, Guler N, Ozisik Y. et al. Increased mean corpuscular volume of erythrocytes during capecitabine treatment: a simple surrogate marker for clinical response. Tumori. 2011;97:711–6. doi: 10.1177/030089161109700606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Buti S, Bordi P, Tiseo M, Bria E, Sperduti I, Di Maio M. et al. Predictive role of erythrocyte macrocytosis during treatment with pemetrexed in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 2015;88:319–24. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kloth JSL, Hamberg P, Mendelaar PAJ, Dulfer RR, van der Holt B, Eechoute K. et al. Macrocytosis as a potential parameter associated with survival after tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment. Eur J Cancer. 2016;56:101–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wenzel C, Mader RM, Steger GG, Pluschnig U, Kornek GV, Scheithauer W. et al. Capecitabine treatment results in increased mean corpuscular volume of red blood cells in patients with advanced solid malignancies. Anti-cancer drugs. 2003;14:119–23. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200302000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures and tables.