Abstract

Major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC I) positive selection of CD8+ T cells in the thymus requires that T cell antigen receptor (TCR) signaling end in time for cytokines to induce Runx3d, the CD8-lineage transcription factor. We examined the time required for these events and found that the overall duration of positive selection was similar for all CD8+ thymocytes in mice, despite markedly different TCR signaling times. Notably, prolonged TCR signaling times were counter-balanced by accelerated Runx3d induction by cytokines and accelerated differentiation into CD8+ T cells. Consequently, lineage errors did not occur except when MHC I–TCR signaling was so prolonged that the CD4-lineage-specifying transcription factor ThPOK was expressed, preventing Runx3d induction. Thus, our results identify a compensatory signaling mechanism that prevents lineage-fate errors by dynamically modulating Runx3d induction rates during MHC I positive selection.

Bi-potential precursor cells use environmental cues to determine their appropriate cell fate in virtually every developmental step in biology. An immunological example is the differentiation of bi-potential CD4+CD8+ (double-positive (DP)) cells in the thymus into either CD4- or CD8-lineage T cells based on the specificity of their TCRs for intra-thymic ligands1. DP thymocytes are the first cells to express αβTCRs on their cell surfaces and require TCR signaling to differentiate further1. However, only TCRs that engage intra-thymic ligands signal DP thymocytes to differentiate into mature CD4+ single-positive (SP4) T cells or CD8+ single-positive (SP8) T cells, which is referred to as ‘positive selection’2.

Transduction of TCR signals into DP thymocytes requires recruitment to the TCRs of the Src family protein tyrosine kinase p56Lck (Lck)3. However, most Lck molecules in DP thymocytes are bound to the cytosolic tails of the co-receptor proteins CD4 and CD8 (refs. 4–6), whose extra-cellular domains bind to MHC class II (MHC II) and MHC I ligands, respectively7–9. TCRs on DP thymocytes can gain proximity to co-receptor-associated Lck molecules by engaging peptide-MHC (pMHC) ligands together with either CD4 or CD8. Consequently, positive selection signals are transduced by TCRs that engage pMHC II ligands together with CD4 co-receptors or that engage pMHC I ligands together with CD8 co-receptors10–13. After positive selection is initiated by TCR signaling, thymocyte lineage fate depends on the lineage-specifying transcription factor that is expressed2,14, with the transcription factor ThPOK directing thymocyte differentiation into a CD4-helper-lineage fate15,16 and the transcription factor Runx3d directing differentiation into a CD8-cytotoxic-lineage fate17–19.

How thymocyte lineage fate is determined during positive selection is best described by the kinetic signaling model of T cell differentiation2,20,21. In the kinetic signaling model, TCR signaling of DP thymocytes specifically terminates Cd8 expression22, causing surface expression of CD8 to decline and CD8-dependent TCR signaling to cease. Cessation of TCR signaling allows intrathymic cytokines such as interleukin 7 (IL-7) to signal Runx3d expression, which specifies the CD8-lineage fate, induces CD8 re-expression and drives thymocyte differentiation into mature CD8+ cytotoxic-lineage T cells23–25. Thus, the generation of CD8+ T cells during MHC I positive selection requires signaling by both TCRs and intra-thymic cytokines, and it requires coordination of those events so that TCR signaling ends in time for cytokines to signal Runx3d expression. Despite its intricacies, lineage-fate errors do not normally occur during MHC I positive selection. However, the actual duration times of TCR and cytokine signaling during MHC I positive selection have never been measured, and it is not known why lineage errors do not occur.

We sought to determine the time required for MHC I positive selection in the thymus and to understand how lineage-fate errors are avoided or prevented. We found that the duration times of both TCR signaling and cytokine signaling during MHC I positive selection varied with TCR signal intensity but varied inversely with one another, so that the overall duration of MHC I positive selection was similar for all TCRs. We identified a compensatory mechanism (signaling compensation) that dynamically adjusted TCR-cytokine signaling times during normal MHC I positive selection to insure correct CD8-lineage assignments but could be circumvented by experimental manipulations that abnormally prolonged MHC I TCR signaling to the point that it induced expression of ThPOK and prevented induction of Runx3d14,26,27. Thus, our results quantify the timing and duration of TCR and cytokine signals driving MHC I positive selection in the thymus and identify signaling compensation as a previously unknown mechanism that prevents lineage-fate errors during normal MHC I positive selection.

RESULTS

Two distinct phases of MHC I positive selection

We sought to determine the duration time of TCR and cytokine signals during MHC I positive selection in the thymus and to assess their effect on subsequent lineage-fate ‘choices’. We first examined thymocytes from mice with homozygous deficiency in MHC II (H2-Ab1−/−; called ‘MHCII−/−’ here) that also expressed green fluorescent protein (GFP), from an allele encoding the recombinase RAG2 (Rag2GFP), as their RAG2-GFP content steadily diminishes with time during MHC I positive selection28. We also used surface expression of the activation marker CD69 and the chemokine receptor CCR7 to track MHC I positive selection because these markers were not expressed in pre-selection thymocytes and were upregulated differentially during positive selection (Fig. 1a). Differential expression of CD69 and CCR7 revealed six stages of MHC I positive selection, with stage 1 consisting of TCR-unsignaled pre-selection thymocytes and stages 2–6 consisting of thymocytes that had been signaled to undergo MHC I positive selection (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). Notably, thymocytes in stages 2–6 contained steadily decreasing amounts of RAG2-GFP, which indicated that TCR-signaled thymocytes at stage 2 differentiated sequentially into stage 3, then stage 4 and then stage 5 and, ultimately, into stage 6 (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1). Thus, stages 2–6 reflect precursor-progeny relationships among thymocytes at sequential stages of MHC I positive selection.

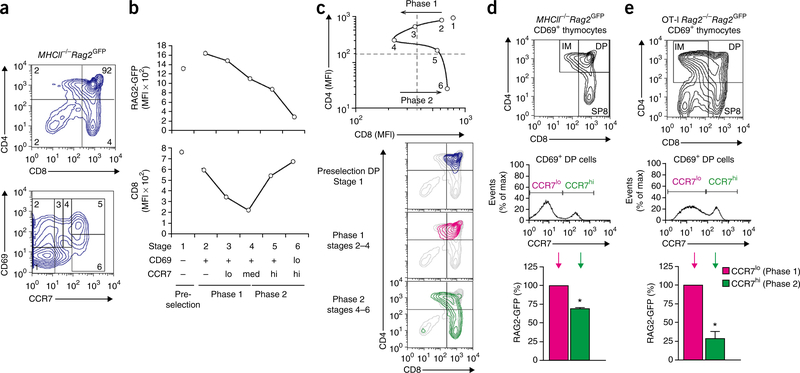

Figure 1.

Developmental progression during MHC I positive selection. (a) Profiles of thymocytes from MHCII−/−Rag2GFP mice. CD69 and CCR7 expression identified thymocytes at six different stages (1–6) of development, with stage 1 consisting of pre-selection thymocytes and stages 2–6 consisting of signaled thymocytes undergoing positive selection (bottom). Numbers in quadrants (top) indicate cell frequency; numbers in outlined areas (bottom) indicate developmental stage. (b) Expression of RAG2-GFP and CD8 at each developmental stage, presented as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI): the temporal sequence of stages 2–6 is indicated by steadily decreasing RAG2-GFP content (top); changing surface CD8 expression on stage 2–6 thymocytes divides MHC I positive selection into phase 1 and phase 2 (bottom). (c) MFI of CD4 and CD8 in thymocytes from MHCII−/−Rag2GFP mice at each stage of development (top), and CD4 and CD8 profiles of thymocytes at various stages of development (colored plots) overlaid on profiles of whole thymocytes (gray plots) (bottom). (d,e) Expression of CD4 and CD8 (top) by gated CD69+ thymocytes from polyclonal MHCII−/−Rag2GFP mice (d) and monoclonal OT-I Rag2−/−Rag2GFP mice (e), and identification of two distinct subpopulations CD69+ DP thymocytes by CCR7 expression (middle) and RAG2-GFP content (bottom), presented relative to CCR7lo cells. *P < 0.001 (Student′s one-sample t-test). Data are representative of three (a–d; n = 5) or five (e) independent experiments (mean and s.e.m. of n = 5 (d) and n = 7 (e)).

We then examined CD8 surface expression at each sequential stage of MHC I positive selection. CD8 surface expression initially declined during stages 2–4 and then abruptly increased during stages 4–6, with CD8 expression being fully restored by stage 6 (Fig. 1b). The marked changes in CD8 expression defined two sequential phases of MHC I positive selection, with phase 1 being characterized by declining CD8 expression on thymocytes that were CCR7neg–lo, and phase 2 being characterized by increasing CD8 expression on thymocytes that were CCR7med–hi.

Concurrent assessment of the expression of CD4 and CD8 on stage 2–6 thymocytes revealed the complicated CD4-CD8 phenotypic pathway that TCR-signaled thymocytes follow during MHC I positive selection29 (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1). Expression of CD4 and CD8 did not clearly distinguish phase 1 thymocytes from phase 2 thymocytes because both were present among DP and CD4+CD8lo intermediate (IM) subsets (Fig. 1c). In each subset, we were able to distinguish phase 1 and phase 2 thymocytes by expression of CCR7 and/or RAG2-GFP. For example, CD69+ DP thymocytes included both CCR7loRAG2-GFPhi (phase 1) cells and CCR7hiRAG2GFPlo (phase 2) cells (Fig. 1d). Such heterogeneity was not caused by TCR diversity, as DP thymocytes bearing the monoclonal OT-I TCR (transgenic TCR selected by MHC I) also included both phase 1 cells and phase 2 cells (Fig. 1e).

Our results indicate that MHC I positive selection proceeds in two sequential phases that are defined by dynamic changes in CD8 co-receptor expression and are distinguishable by quantitative differences in CCR7 expression.

Runx3d induction during positive selection

Because Runx3d is the transcription factor that specifies CD8-lineage fate, we next determined when Runx3d is expressed during MHC I positive selection. For this determination, we introduced the Runx3dYFP reporter allele (in which yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) is expressed from a Runx3d allele)26 into RAG2-deficient OT-I mice. Runx3d-YFP was first detectable only in stage 4 cells, with expression increasing in stages 5–6 (Fig. 2a). To gain further insight into Runx3d expression during MHC I positive selection, we also assessed Runx3d-YFP expression in OT-I thymocyte populations defined by expression of CD4 and CD8 (Fig. 2b). Runx3d-YFP− cells and Runx3d-YFP+ cells were both present in DP and IM OT-I thymocyte subsets, with IM OT-I cells being further subcategorized, for greater discrimination, into IM1, IM2 and IM3 subsets on the basis of decreasing CD8 surface expression (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2). Quantifying CCR7 expression on Runx3d-YFP− and Runx3d-YFP+ cells in each thymocyte subset confirmed that Runx3d-YFP− thymocytes were phase 1 cells that sequentially differentiated from DP>IM1>IM2>IM3, and that Runx3d-YFP+ thymocytes were phase 2 cells that sequentially differentiated from IM3>IM2>IM1>DP>SP8 (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2). Thus, Runx3d expression does not begin until stage 4, at which point cells have the least surface expression of CD8, and increases throughout phase 2 differentiation.

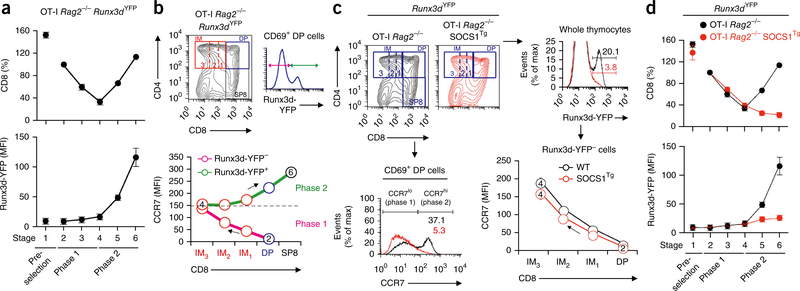

Figure 2.

Runx3d induction during MHC class I positive selection. (a) Expression of CD8 and Runx3d-YFP in thymocytes from OT-I Rag2−/− Runx3dYFP mice at each stage of development (1–6); CD8 expression is presented relative to that of stage 2 cells, set as100%. (b) CD4 and CD8 profiles of thymocytes from OT-I Rag2−/− Runx3dYFP mice; gates indicate DP, IM1, IM2, IM3 and SP8 subsets (top left), identification of Runx3d-YFP− and Runx3d-YFP+ cells among CD69+ DP thymocytes (top right), and CCR7 expression on Runx3d-YFP− and Runx3d-YFP+ thymocytes in each gated subset (bottom). Arrows indicate temporal sequence of differentiation. (c) Profiles of thymocytes from OT-I Rag2−/− Runx3dYFP mice and OT-I Rag2−/− SOCS1Tg Runx3dYFP mice (top left): overlay of Runx3d-YFP expression in whole thymocytes (top right) and CCR7 expression on gated CD69+ DP thymocytes (bottom left), and CCR7 expression on Runx3d-YFP− cells in each subset of DP, IM1, IM2 and IM3 cells (bottom right; arrow as in b). (d) Expression of CD8 (presented as in a) and Runx3d-YFP on thymocytes at each stage of development (1–6), from OT-I Rag2−/−Runx3dYFP mice (black lines) and OT-I Rag2−/− SOCS1Tg Runx3dYFP mice (red lines). Data are representative of four (a,b) or three (c,d) independent experiments (mean and s.e.m. of n = 6 in a,d).

Runx3d induction has previously been shown to be signaled by intrathymic cytokines23,24 and to be inhibited by the cytokine-signaling suppressor SOCS1 (refs. 24,27,30). We observed that transgenic expression of SOCS1 (SOCS1Tg)31 almost completely abrogated Runx3d-YFP expression and therefore impaired phase 2 differentiation (Fig. 2c), as very few CD69+ DP OT-I SOCS1Tg thymocytes were CCR7hi (Fig. 2c). Moreover, the few OT-I SOCS1Tg thymocytes that became stage 5–6 cells did not normally upregulate expression of CD8 and Runx3d-YFP (Fig. 2d). In contrast, SOCS1Tg expression did not affect phase 1, as Runx3d-YFP− cells normally increased CCR7 expression during phase 1 differentiation from DP>IM1>IM2>IM3 (Fig. 2c).

Our results demonstrate that phase 1 differentiation proceeds independently of cytokine signaling, whereas phase 2 differentiation is driven by cytokine signals that induce Runx3d expression. Because they do not express Runx3d, MHC-I-signaled phase 1 thymocytes can be considered ‘lineage uncertain’, whereas phase 2 thymocytes that do express Runx3d are ‘CD8 lineage committed’.

Factors determining phase 1 duration

Because phase 1 differentiation is driven by TCR signaling, phase 1 duration might be affected by TCR signaling intensity. To assess this possibility, we used RAG-deficient H-2b female mice containing monoclonal thymocyte populations bearing various transgenic TCRs (HY, F5, P14 and OT-I) that signal MHC I positive selection with different intensities. As reflected by surface expression of the negative regulator CD5 on stage 2 (CD69+CCR7−) thymocytes that had just received TCR signals, the in vivo signaling intensities of transgenic TCRs formed a descending hierarchy of OT-I > P14 > F5 > HY (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 3a). Interestingly, thymocyte profiles of mice with transgenic TCR expression revealed that the surface abundance of CD8 on CD4+CD69+ IM thymocytes decreased as TCR signaling intensity increased (Fig. 3b). To quantify surface CD8 on IM thymocytes bearing different transgenic TCRs, we normalized CD8 protein abundance on TCR-signaled CD69+ IM thymocytes to CD8 expression on their own pre-selection DP thymocytes. Notably, CD8 expression on IM thymocytes was reduced least on HY thymocytes and was reduced most on OT-I thymocytes (Fig. 3b), although CD8 expression in all cases was fully restored during phase 2 differentiation into SP8 cells (Fig. 3b). Thus, TCR signaling intensity specifically determines the extent of CD8 loss during phase 1 differentiation.

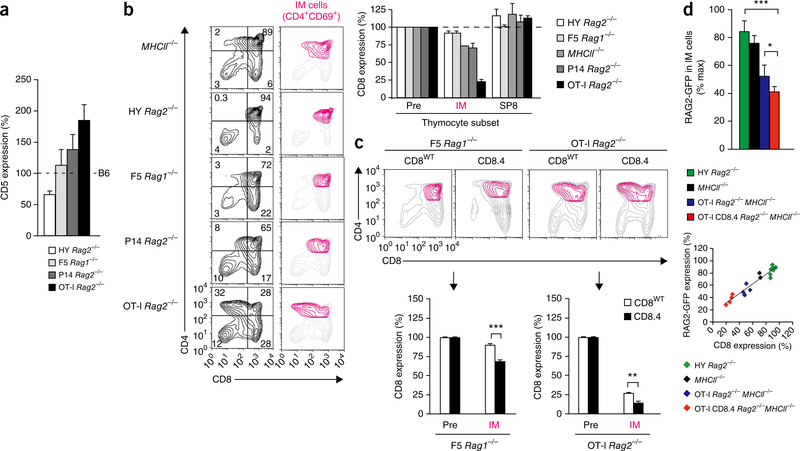

Figure 3.

Effect of TCR-CD8 signaling on phase 1 duration. (a) CD5 expression on CD69+CCR7− DP thymocytes from Rag2−/− mice with various transgenic TCRs (key), presented relative to that of cells from C57BL/6 mice. (b) Profiles of whole thymocytes and IM thymocytes (CD4+CD69+CCR7+) (left), and CD8 expression on thymocyte subsets, presented relative to that on preselection (CD69− DP) thymocytes (Pre) in the same mouse (right). (c) Profiles of whole thymocytes (gray) and IM (CD4+CD69+CCR7+) thymocytes (colors) expressing CD8wt or CD8.4 (top), and CD8 expression on IM cells from transgenic mice (below plots), presented relative to that on pre-selection DP thymocytes from those mice (bottom). (d) RAG2-GFP content in IM (CD4+CD69+CCR7+) thymocytes, presented relative to that in just-signaled (CD69+CCR7−) DP thymocytes from the same thymi (top). In IM (CD4+CD69+CCR7+) thymocytes, RAG2-GFP content and CD8 expression were highly correlated with a correlation coefficient greater than 0.92 (r2 > 0.92) (bottom). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 (Student′s two-tailed t-test). Data are representative of three (a–c) or four (d) independent experiments (mean and s.e.m. of n = 3 (a,b), n = 5, 6, 8 or 8 (c) or n = 7, 2, 4, 4 (d)).

MHC-I-specific TCR signaling in the thymus requires both TCR and CD8 but is limited by the low amount of the protein tyrosine kinase Lck that is associated with the CD8 cytosolic tail32,33. Consequently, MHC I signaling intensity might increase with greater binding of Lck to CD8. To assess this possibility, we compared thymocytes expressing endogenously encoded wild-type CD8 (CD8wt) or CD8 that had been re-engineered to express CD4 cytosolic tails that bind more Lck (CD8.4)34 (Fig. 3c). In fact, CD8 loss on IM thymocytes was greater with CD8.4 than CD8wt whether thymocytes expressed weakly signaling F5 TCRs or strongly signaling OT-I TCRs (Fig. 3c). Thus, low binding of Lck to wild-type CD8 limits TCR signaling intensity and CD8 loss during phase 1 differentiation.

The extent of CD8 loss during phase 1 differentiation reflects the passage of time since thymocytes were initially signaled by their TCR to terminate Cd8 transcription22. To confirm this, we introduced the transgene encoding RAG2-GFP into mice with transgenic TCR expression and compared the GFP content in IM thymocytes relative to that in stage 2 (CD69+CCR7−) DP thymocytes in their own thymus (Fig. 3d). As expected, RAG2-GFP content was lower in IM thymocytes than in stage 2 DP thymoyctes, but the amount of RAG2-GFP remaining in IM thymocytes with OT-I TCR was less than that remaining in IM thymocytes with HY TCR, and the remaining RAG2-GFP content of OT-I IM thymocytes was further reduced by CD8.4 (Fig. 3d). Plotting relative CD8 expression versus relative RAG2-GFP content in IM thymocytes revealed a marked correlation (r2 > 0.92) between these two parameters (Fig. 3d). Given that the decrease in RAG2-GFP content in IM thymocytes is a direct measure of time that has passed since TCR signaling initiated phase 1 differentiation, these results indicate that CD8 loss on IM thymocytes is also a measure of phase 1 duration time.

Our findings suggest that CD8-dependent TCR signals initiate MHC-I-specific positive selection and continue throughout phase 1, but with steadily diminishing intensity because of progressively declining CD8 surface expression (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Phase 1 differentiation lasted longer for OT-I thymocytes than for HY thymocytes because OT-I TCRs have higher ligand affinity and can therefore continue signaling with fewer remaining CD8 co-receptors. Phase 1 differentiation finally terminated when TCR–co-receptor signaling intensity became too weak to prevent cytokines from signaling Runx3d expression and initiating phase 2 differentiation.

Inverse relationship between phase 1 and 2 duration time

It was possible to calculate the duration time in hours for each phase of MHC I positive selection because the half-life of GFP protein from the Rag2GFP transgene declines with a linear half-life of 54–56 h (ref. 28). Having defined phase 1 by decreasing CD8 expression and phase 2 by increasing CD8 expression, we calculated phase 1 duration times on the basis of RAG2-GFP content in IM cells with lowest CD8 (CD8lowest) surface expression and we calculated phase 2 duration times based on RAG2-GFP content in SP8 (stage 6) cells (Fig. 4).

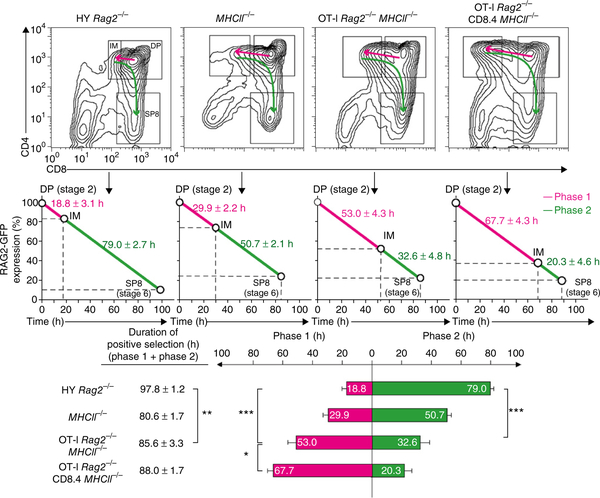

Figure 4.

Duration time of phase 1, phase 2 and overall positive selection. Thymocyte profiles (top) showing the DP, IM and SP8 gates of various mice (above plots). Duration time (in hours) was calculated on the basis of the RAG2-GFP half-life of 54–56 h (ref. 28) with the following formula: duration time = (100 – relative RAG2-GFP) / 0.9. The RAG2-GFP content in just-signaled (CD69+CCR7−) DP thymocytes was set as 100%. Phase 1 duration time was calculated using relative RAG2-GFP expression on IM (CD69+CD4+CD8lowest) thymocytes, and the duration time of overall positive selection was calculated using relative RAG2-GFP expression on stage 6 SP8 (CCR7+CD8 SP) thymocytes. Phase 2 duration time was calculated as the difference between overall positive selection and phase 1 duration times (middle and bottom). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 (Student′s two-tailed t test). Data are representative of four independent experiments (mean and s.e.m. of n = 5, 6, 4, 5).

Phase 1 duration times for HY thymocytes and OT-I thymocytes were 18 h and 53 h, respectively (Fig. 4), with the latter’s time being further prolonged to 67 h by strongly signaling CD8.4 co-receptors. Thus, phase 1 duration times varied directly with TCR and CD8 signaling intensity.

To our surprise, phase 2 duration times varied inversely with phase 1 duration times. Phase 2 duration times were longest (79 h) in HY thymocytes with short phase 1 times, and phase 2 duration times were shortest (20 h) in OT-I CD8.4 thymocytes with long phase 1 times. The inverse relationship between the duration times of phase 1 and phase 2 was notable, as phase 1 duration times were 2.5- to 3-fold longer for OT-I thymocytes than for HY thymocytes, whereas phase 2 duration times were 2.5- to 3-fold shorter (Fig. 4).

The inverse relationship between the differentiation times of phase 1 and phase 2 was unexpected. Given that CD8 loss during phase 1 was greatest for OT-I thymocytes, we had expected CD8 re-expression during phase 2 to be slowest for OT-1 thymocytes. However, the opposite was true: despite starting phase 2 differentiation with the least CD8, OT-I thymocytes completed phase 2 differentiation more quickly than HY thymocytes did (32 h versus 79 h) (Fig. 4). We considered the possibility that phase 2 differentiation time might reflect cytokine signaling intensity and that cytokine signaling intensity might be influenced by TCR signaling duration. Indeed, pre-selection DP thymocytes are cytokine unresponsive as a result of high expression of Socs1 and absent expression of Il7r (which encodes the cytokine receptor IL-7Rα)30,35,36, but TCR signaling induces DP thymocytes to terminate Socs1 expression and re-initiate Il7r expression24,30. As a result, Socs1 mRNA content might be expected to steadily decrease and IL-7Rα surface expression to steadily increase during phase 1 differentiation, causing thymocytes to acquire greater and greater ‘cytokine-response potential’ the longer phase 1 differentiation persists (Supplementary Fig. 4).

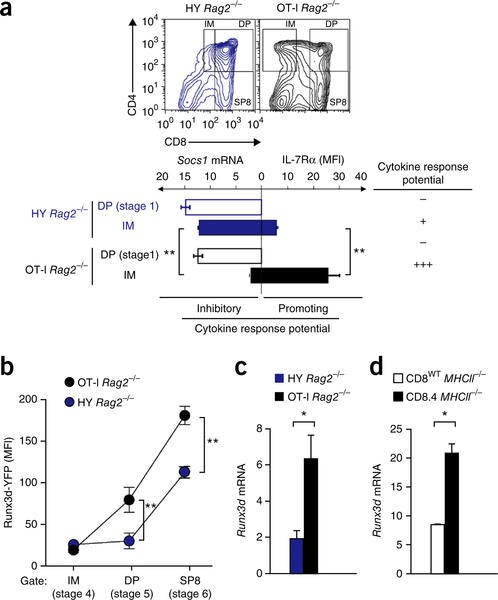

To address this notion, we quantified Socs1 mRNA and IL-7Rα surface expression during phase 1 differentiation of OT-I and HY thymocytes. Indeed, the decrease in Socs1 mRNA and the increase in surface IL-7Rα during phase 1 were both greater in OT-I thymocytes than in HY thymocytes (Fig. 5a), indicating that longer phase 1 duration times do result in greater cytokine response potential.

Figure 5.

Phase 1 duration affects cytokine-response potential and Runx3d induction rate. (a) Thymocyte profiles (top) showing the DP, IM and SP8 gates for Rag2−/− HY or OT-I mice (above plots), and expression of Socs1 mRNA and surface expression of IL-7Rα by stage 1 preselection (CD69−CCR7−) DP thymocytes and IM (CD69+CCR7+) thymocytes in the same mice (below). (b) Runx3d-YFP expression during phase 2 differentiation of the thymocyte subsets in a. (c,d) Runx3d mRNA expression in stage 6 (TCR+CCR7+CD4−CD8+) SP8 thymocytes from Rag2−/− HY or OT-I mice (c) and CD8wt or CD8.4 MHCII−/− mice (d). *P < 0.01 and **P < 0.001 (Student′s two-tailed t-test). Data are representative of four (a–c) or two (d) independent experiments (mean and s.e.m. of n = 8 technical replicates (a,b; flow cytometry) or n = 4 (a,c) or n = 3 (d) technical replicates (mRNA)).

One effect of greater cytokine-response potential might be to accelerate and increase Runx3d induction, shortening the phase 2 differentiation time (Supplementary Fig. 4). If that were correct, then Runx3d expression would be higher throughout phase 2 differentiation in thymocytes with high-affinity than in those with low-affinity TCRs. In fact this prediction was precisely what we observed (Fig. 5b–d). Runx3d-YFP expression was higher in OT-I thymocytes than in HY thymocytes at both stage 5 and stage 6 (Fig. 5b), indicating that Runx3d expression during phase 2 increases faster and to a greater amount in high-affinity OT-I thymocytes. Moreover, Runx3d mRNA expression was threefold greater in OT-I SP8 thymocytes than HY SP8 thymocytes at the conclusion of phase 2 differentiation (Fig. 5c), and was greater in SP8 thymocytes with CD8.4 co-receptors (Fig. 5d). We conclude that prolonged phase 1 duration times increase cytokine response potential, which quantitatively increases both the rate and magnitude of Runx3d induction to accelerate phase 2 differentiation.

Because the duration times of phase 1 and phase 2 varied inversely to one another, we then considered their effect on overall positive selection times. We were surprised to find that variations in the duration times of phase 1 and phase 2 almost completely compensated for one another, as overall MHC I positive selection times were relatively constant (differing by less than 20%) among thymocytes with TCR–co-receptor signals of different intensity (Fig. 4).

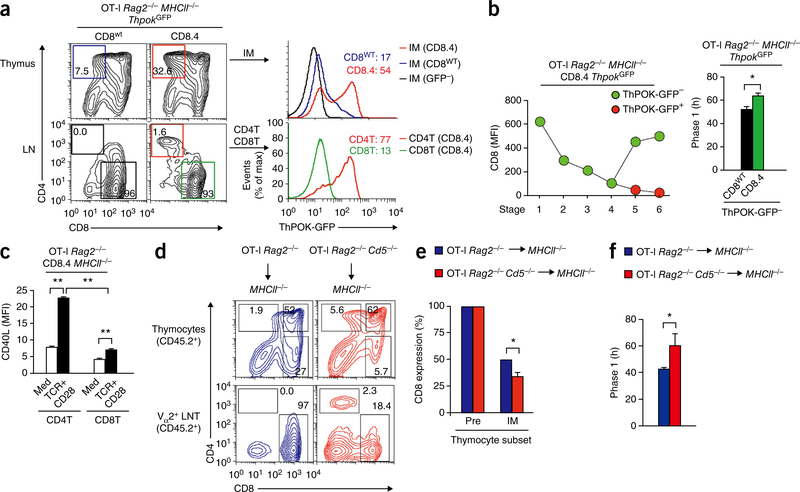

Phase 1 prolongation results in lineage errors

Because phase 1 thymocytes did not express Runx3d and were lineage uncertain, we wondered whether prolonging phase 1 to increase the duration of lineage uncertainty might cause lineage ‘choice’ errors. To determine whether MHC I selected thymocytes could erroneously express ThPOK, we introduced the ThpokGFP reporter37 into OT-I Rag2−/−MHCII−/− mice that expressed only MHC I ligands. Interestingly, ThPOK-GFP expression was significantly expressed only in IM thymocytes from OT-1 CD8.4 mice that had the longest phase 1 differentiation time (67 h) in this study (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 5a). In fact, OT-I CD8.4 thymocytes that were ThPOK+ continuously lost CD8 surface expression during positive selection and differentiated into SP4 thymocytes (Fig. 6b). In contrast, OT-I CD8.4 thymocytes that remained ThPOK− re-expressed surface CD8 protein during stages 5 and 6 and differentiated into SP8 thymocytes (Fig. 6b). Notably, the phase 1 differentiation time of OT-I CD8.4 thymocytes that remained ThPOK− was 63.6 h, which was significantly longer (P < 0.05) than that of OT-I CD8wt thymocytes (Fig. 6b). Thus, stronger signaling CD8.4 co-receptors prolonged phase 1 duration for OT-I thymocytes whether or not ThPOK was expressed, indicating that phase 1 prolongation was not a result of ThPOK. Instead, we suggest that prolonged MHC I TCR signaling induces ThPOK expression.

Figure 6.

Prolongation of phase 1 results in lineage errors. (a) Profiles of thymocytes (top left) and LNT cells (bottom left); numbers in outlined areas indicate cell frequency in each gate. Right, one-color histograms of ThPOK-GFP in gated IM thymocytes (top right) and gated CD4+ LNT cells (CD4T) and CD8+ LNT cells (CD8T) (bottom right); numbers in plots indicate MFI. (b) CD8 expression on ThPOK-GFP− and ThPOK-GFP+ thymocytes from OT-I Rag2−/−MHCII−/− CD8.4 ThpokGFP mice, at each stage of development (1–6) (left), and phase 1 duration, calculated from the amount of CD8 surface expression remaining on ThPOK-GFP− IM thymocytes (right). (c) CD40L expression on CD4+ LNT cells (LNCD4T) and CD8+ LNT cells (LNCD8T) from OT-I Rag2−/− CD8.4 MHCII−/− mice after overnight stimulation with immobilized antibodies specific for TCR and CD28. (d) Profiles of thymocytes (top) and LNT cells (bottom) from chimeras constructed 8 weeks before by injection of T cell–depleted CD45.2+ BM into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ MHCII−/− host mice (above plots). (e) CD8 expression on pre-selection (CD69− DP) thymocytes and IM (CD4+CD69+CCR7+) thymocytes from chimeras as in d. (f) Phase 1 duration in cells from chimeras as in d, calculated by quantification of remaining CD8 expression on IM thymocytes. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001 (Student′s two-tailed t-test). Data are representative of three independent experiments (a–f; mean and s.e.m. of n = 6,3 in b and n = 3 in e,f; and mean and s.e.m. of tripricate cultures in c).

Consistent with the presence of CD4+ThPOK-GFP+ cells in the thymus, a small but distinct population of CD4+ThPOK-GFP+ T cells were present in the periphery of OT-I CD8.4 mice (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 5a,b). Such OT-I CD4+ T cells expressed less ThPOK-GFP than did conventional CD4+ T cells from C57BL/6 mice (Supplementary Fig. 5a), but nevertheless possessed helper function as they upregulated surface CD40L expression following stimulation via TCR plus the costimulatory molecule CD28 (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 5c).

The number of CD4+ lymph node T cells (LNT cells) detected in OT-I CD8.4 mice (Supplementary Fig. 5b) likely under-estimated the rate of lineage specification errors, because TCR–co-receptor mismatching would impair TCR signaling and cell survival in the periphery. Indeed, CD5 expression was lower on CD4+ OT-I T cells than on CD8+ OT-I T cells (Supplementary Fig. 5d), the reverse of normal CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, indicating that TCR signaling by peripheral self ligands was impaired in TCR-co-receptor mis-matched OT-I T cells. Moreover, recent thymic emigrants (that is, RAG2-GFP+ T cells) constituted fully 40% of CD4+ OT-I T cells but less than 10% of CD8+ OT-I T cells, indicating impaired peripheral survival of mis-matched OT-I CD4+ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 5d).

To confirm that lineage-specification errors in OT-I CD8.4 thymocytes are the result of prolonged TCR signaling and are not unique to CD8.4 thymocytes, we prolonged the phase 1 differentiation time of OT-I CD8wt thymocytes by making them CD5 deficient to remove a potent inhibitor of TCR signaling38 (Fig. 6d). To ensure that OT-I Cd5−/− thymocytes were MHC I signaled, we used CD5-deficient OT-I (CD45.2+) bone marrow stem cells to reconstitute lethally irradiated MHCII−/− (CD45.1+) host mice (Fig. 6d). CD5 deficiency resulted in significantly greater CD8 loss and significantly prolonged phase 1 differentiation of OT-I IM thymocytes (Fig. 6e,f). Notably, prolonged phase 1 duration was again associated with the appearance of mismatched OT-I CD4+ LNT cells (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. 5e).

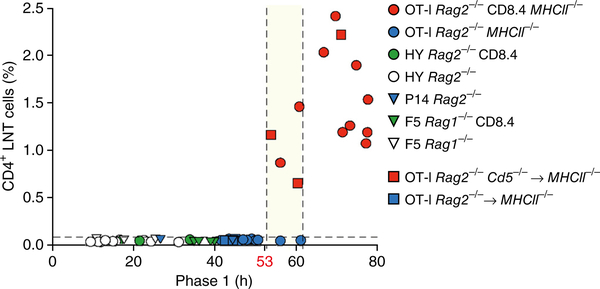

Time limit for error-free CD8 lineage specification

Finally, we asked whether there existed a maximum TCR signaling time limit for MHC-I-signaled thymocytes to accurately ‘choose’ the CD8-lineage fate. To answer this question, we plotted the frequency of peripheral CD4+ LNT cells versus phase 1 duration time in the thymus for Rag2−/− mice with the various transgenic TCRs (Fig. 7). In mice with phase 1 duration times of less than 53 h, MHC-I-selected CD4+ T cells were undetectable (Fig. 7). In contrast, mice with phase 1 duration times greater than 60 h contained MHC-I-selected CD4+ T cells in frequencies of 0.6–2.25%, despite impaired peripheral survival of T cells with mismatched TCR and co-receptors (Fig. 7). Phase 1 duration times of 53–60 h represented an inflection point between error-free fate ‘choices’ and error-prone lineage fate ‘choices’ (Fig. 7). Thus, 53 h is the maximum TCR signaling time limit for consistently error-free CD8-lineage ‘choice’ during MHC I positive selection, with longer MHC I TCR signaling times becoming increasingly error prone.

Figure 7.

Time limit for error-free CD8 lineage specification. Frequency of CD4+ LNT cells plotted against phase 1 duration time for each mouse in this study (mouse strains in key). Data are from 20 independent experiments with individual mice (n = 53) in.

DISCUSSION

By deconstructing MHC I positive selection into its component steps, we have determined the sequence, timing and duration of signaling events that drive MHC I positive selection and result in CD8-lineage fate assignment. MHC I positive selection proceeded in two phases, with phase 1 being driven by TCR signaling and phase 2 being driven by cytokine signaling. In normal thymocytes, TCR signaling duration varied between 18 h and 53 h depending on TCR-ligand affinity, whereas cytokine signaling duration varied between 32 h and 79 h depending on the Runx3d induction rate, with faster and greater Runx3d induction shortening cytokine signaling times. The dynamic adjustment of TCR-cytokine signaling times during MHC I positive selection is called ‘signaling compensation’ and provides normal thymocytes with the amount and duration of cytokine signals needed to induce Runx3d and drive differentiation into CD8+ T cells. Notably, signaling compensation required MHC I TCR signaling to persist for no more than 53 h, which was the maximum MHC I TCR signaling time in normal thymocytes. Signaling compensation was circumvented by experimental manipulations that prolonged MHC I TCR signaling beyond 53–60 h, which induced ThPOK expression and prevented Runx3d expression, causing erroneous differentiation into CD4-helper-lineage T cells.

Signaling compensation is intrinsic to individual thymocytes and dynamically adjusts cytokine signaling times during MHC I positive selection. The basis of signaling compensation derives from the unique physiology of DP thymocytes. DP thymocytes receive survival signals only from their TCR, and cannot receive survival signals from intra-thymic cytokines24,30,35,36. In fact, pre-selection DP thymocytes are cytokine unresponsive because of absent Il7r expression and uniquely high Socs1 expression24,35. TCR signaling of DP thymocytes re-initiates Il7r expression and terminates Socs1 expression to permit cytokine signal transduction and subsequent Runx3d expression in positively selected thymocytes24. Consequently, thymocytes acquire greater and greater ‘cytokine-response potential’ the longer MHC-I- specific TCR signaling persists. Thus, the mechanism of signaling compensation can be understood as follows: the longer MHC I TCR signaling persists, the greater the thymocyte cytokine-response potential, the more intense the subsequent cytokine signaling, the faster and greater Runx3d induction, and the less time required for cytokine-signaled thymocytes to differentiate into mature SP8 T cells. Thus, the Runx3d induction rate is a key factor for determining the time required for CD8+ T cell differentiation.

Although cytokines induce Runx3d expression, prolonged MHC I TCR signaling induced ThPOK expression, so long as it was of sufficient duration. Error-free CD8-lineage fate during MHC I positive selection required TCR signaling to end before ThPOK expression was induced. CD8 loss during phase 1 disrupted TCR signaling because, with few exceptions, MHC-I-specific TCRs on DP thymocytes required CD8 to engage intra-thymic ligands. The few MHC-I-specific TCRs that are CD8 independent in the thymus signal thymocyte differentiation into alternative-lineage cells, such as natural killer T cells39, but not into CD8-lineage T cells. It is a curious but critical feature of MHC I positive selection that signaled DP thymocytes immediately begin losing surface CD8 protein expression until it becomes too low to sustain continued signaling by CD8-dependent TCRs. The amount of time TCR signaling continues before being disrupted varies for different TCRs because TCRs with higher binding affinities require fewer CD8 co-receptors to continue signaling. Nevertheless, the maximum time that MHC I TCR signaling persisted in normal thymocytes was ~53 h. However, experimental manipulations such as genetic deletion of Cd5 or expression of CD8.4 with stronger signaling resulted in prolongation of OT-I TCR signaling beyond 53 h, as they reduced the number of CD8 co-receptors required for continued TCR signaling. Notably, the result of prolonged TCR signaling was the appearance of ThPOK+ thymocytes and CD4-lineage-fate errors, events that did not occur in unmanipulated thymocytes.

We suspect it is not simply fortuitous that MHC I TCR signaling is disrupted in normal thymocytes before ThPOK expression can be induced. Instead, we think that CD8 proteins have evolved to be weakly signaling co-receptor molecules whose surface expression decreases rapidly enough during MHC I positive selection to disrupt TCR signaling before ThPOK expression is induced. We also suspect that the regulatory elements controlling ThPOK expression have evolved to be activated by TCR signals of longer duration and greater intensity than can normally be achieved by CD8-dependent TCRs during positive selection. Consequently, we think that CD8 co-receptor proteins and ThPOK molecules might have co-evolved to minimize lineage errors during MHC I positive selection.

Our results provide an explanation for conflicting conclusions about the role of TCR signaling in CD8-lineage specification40–42. It is now appreciated that the CD8-lineage fate is not specified by MHC I TCR signals but is instead specified by cytokine signals that induce Runx3d expression24. Indeed, we found that Runx3d expression was not induced by TCR signaling during phase 1 but was induced by cytokine signaling during phase 2. Nonetheless, MHC I TCR signal duration indirectly affected the induction of Runx3d expression by influencing thymocyte cytokine-response potential. Consequently, we think that previous studies concluding that MHC I TCR signals specify the CD8-lineage fate failed to appreciate the fact that the influence of TCR signaling on CD8 specification is only indirect40,42. In addition, we found that not all DP thymocytes are pre-selection cells, as CD8-lineage-committed thymocytes during phase 2 differentiation may fall within the DP gate. Indeed, unlike pre-selection DP thymoyctes, which were invariably CCR7−, DP thymocytes that were CCR7int–hi were in the process of upregulating Runx3d expression and surface expression of CD8 during phase 2 differentiation.

In conclusion, our results substantially enhance the understanding of MHC I positive selection and CD8-lineage fate by revealing how TCR and cytokine signaling are coordinated during MHC I positive selection. By dynamically adjusting the rate and magnitude of Runx3d induction by intra-thymic cytokines, signaling compensation ensures correct CD8-lineage assignments to thymocytes during normal MHC I positive selection. Thus, TCR and cytokine signaling times are dynamically regulated during normal MHC I positive selection to generate CD8-lineage T cells and to avoid lineage-fate errors.

METHODS

Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper.

ONLINE METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Frederick Cancer Research and Development center. MHCII−/− mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. CD8.4 mice were generated by replacing the endogenously encoded CD8α cytosolic tail with the CD4 cytosolic tail by gene knock-in technology as previously described34. Rag2GFP Tg mice were provided by M. Nussenzweig43; Runx3dYFP knock-in reporter mice were provided by D. Littman26; SOCS1Tg mice were from M. Kubo31; ThpokGFP Tg mice were from R. Bosselut37; and HY Rag2−/−, HY Rag2−/− Rag2GFPTg, HY Rag2−/− Runx3dYFP, CD8.4 HY Rag2−/−, F5 Rag1−/−, CD8.4 F5 Rag1−/−, P14 Rag2−/−, OT-I Rag2−/−, OT-I Rag2−/− Rag2GFPTg, OT-I Rag2−/− Runx3dYFP, OT-I Rag2−/− SOCS1Tg Runx3dYFP, OT-I Rag2−/− MHCII−/−, OT-I Rag2−/− MHCII−/− Rag2GFPTg, OT-I Rag2−/− MHCII−/− ThpokGFPTg, OT-I Rag2−/− Cd5−/−, CD8.4 OT-I Rag2−/−, CD8.4 OT-I Rag2−/− MHCII−/−, CD8.4 OT-I Rag2−/− MHCII−/− Rag2GFPTg, CD8.4 OT-I Rag2−/− MHCII−/− ThpokGFPTg, CD45.1+MHCII−/− were bred in our own colony. Animal experiments were approved by the National Cancer Institute Animal Care and Use Committee. Age-matched mice (6–12 weeks) were used for experiments. All mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in accordance with US National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines.

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were prepared and stained with fluorochrome conjugated antibodies with the following specificities: CD4 (GK1.5), CD8α (53–6-7), CD69 (H1.2F3), CCR7 (4B12), CD5 (53–7.3), IL-7Rα (A7R34), TCRβ (H57–597), CD40L (MR1), CD45.2 (104), Vα2 (B20.1) (Supplementary Table 1).

For cell surface staining of fresh cells, 1–2 × 106 cells were incubated with 2.4G2 (anti-mouse Fcγ III/II receptor) and stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies. Dead cells were excluded by forward light-scatter gating and propidium iodide staining. Stained samples were analyzed with a FACSLSRII or a FACSFortessa flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Data were analyzed using software developed at the US National Institutes of Health.

Time of positive selection

Rag2GFP Tg was introduced into MHCII−/−, HY Rag2−/−, OT-I Rag2−/− MHCII−/− and CD8.4 OT-I Rag2−/− MHCII−/− mice. CD69+CCR7−DP thymocytes (DP, stage#2) were considered the starting point and CCR7hiCD8SP cells (SP8, stage#6) the end point of positive selection. CD69+CCR7+CD4+CD8lowestIM cells (IM) were used for determining the end point of phase 1 and the starting point of phase 2. RAG2-GFP expression in IM and SP8 relative to DP was determined and those values were used for calculation of the duration of phase 1 and total time of positive selection with the formula: time = (100 – relative GFP expression)/0.9. Duration of phase 2 was determined by subtracting phase 1 duration time from total time of positive selection. For phase 1 thymocytes, relative Rag2-GFP expression could be derived from relative CD8 expression by the formula: [Relative Rag2-GFP expression] = 0.8783*[Relative CD8 expression] + 3.9034), which was determined from Figure 3d.

Radiation bone marrow chimeras

CD45.2+ bone marrow cells were treated with Thy1-specific antibody and complement to deplete Thy1+ cells. 10–15 × 106 Thy1-depleted bone marrow cells were injected into CD45.1+ host mice that were lethally irradiated (9.5 Gy) at least 6 h before the transfer, and reconstituted mice were analyzed 8 weeks later.

In vitro helper function assay

Whole LNT cells from OT-I Rag2−/− CD8.4 MHCII−/− mice were stimulated overnight with immobilized anti-TCRβ + anti-CD28 mAbs and then examined for CD40L and CD69 expression by flow cytometry.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated with Trizol (Invitrogen) and treated with DNase I (Invitrogen) to eliminate possible genomic DNA contamination. cDNA synthesis was done by superscript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen) with oligo dT primers. Quantitative RTPCR was done with QuantiTect SYBR green PCR system (Qiagen). Real time PCR data are shown relative RPL13a. The primer sequences for SYBR green PCR system are as follows. RPL13a; forward (CGAGGCATGCTGCCCCACAA), reverse (AGCAGGGACCACCATCCGCT), SOCS1; forward (GGCAGCCGA CAATGCGATCT), reverse (GATCTGGAAGGGGAAGGAAC), Runx3d; forward (GCGACATGGCTTCCAACAGC), reverse (CTTAGCGCGCCGC TGTTC TCGC).

Statistical analysis

Student’s t test with two-tailed distributions was used for statistical analysis. P values of 0.05 or less were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H. Park, D. Singer and N. Taylor for critical reading of the manuscript; M. Nussenzweig (Rockefeller University) for Rag2GFPTg mice; D. Littman (New York University) for Runx3dYFP knock-in reporter mice; R. Bosselut (National Cancer Institute) for ThpokGFP mice; M. Kubo (Tokyo University of Science, Japan) for SOCS1Tg mice; and S. Sharrow and L. Granger for flow cytometry. Supported by the Intramural Research Program of the US National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Science and Technology (Grant-in-Aid for Research Activity Start-up 26893033; and Scientific Research (C) 15K08524).

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Note: Any Supplementary Information and Source Data files are available in the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.Starr TK, Jameson SC & Hogquist KA Positive and negative selection of T cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol 21, 139–176 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singer A, Adoro S & Park JH Lineage fate and intense debate: myths, models and mechanisms of CD4- versus CD8-lineage choice. Nat. Rev. Immunol 8, 788–801 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palacios EH & Weiss A Function of the Src-family kinases, Lck and Fyn, in T-cell development and activation. Oncogene 23, 7990–8000 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veillette A, Bookman MA, Horak EM & Bolen JB The CD4 and CD8 T cell surface antigens are associated with the internal membrane tyrosine-protein kinase p56lck. Cell 55, 301–308 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barber EK, Dasgupta JD, Schlossman SF, Trevillyan JM & Rudd CE The CD4 and CD8 antigens are coupled to a protein-tyrosine kinase (p56lck) that phosphorylates the CD3 complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 3277–3281 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaw AS et al. The lck tyrosine protein kinase interacts with the cytoplasmic tail of the CD4 glycoprotein through its unique amino-terminal domain. Cell 59, 627–636 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norment AM, Salter RD, Parham P, Engelhard VH & Littman DR Cell-cell adhesion mediated by CD8 and MHC class I molecules. Nature 336, 79–81 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doyle C & Strominger JL Interaction between CD4 and class II MHC molecules mediates cell adhesion. Nature 330, 256–259 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haughn L et al. Association of tyrosine kinase p56lck with CD4 inhibits the induction of growth through the alpha beta T-cell receptor. Nature 358, 328–331 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins EJ & Riddle DS TCR-MHC docking orientation: natural selection, or thymic selection? Immunol. Res 41, 267–294 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Laethem F et al. Deletion of CD4 and CD8 coreceptors permits generation of alphabetaT cells that recognize antigens independently of the MHC. Immunity 27, 735–750 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Laethem F, Tikhonova AN & Singer A MHC restriction is imposed on a diverse T cell receptor repertoire by CD4 and CD8 co-receptors during thymic selection. Trends Immunol. 33, 437–441 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Laethem F et al. Lck availability during thymic selection determines the recognition specificity of the T cell repertoire. Cell 154, 1326–1341 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taniuchi I & Ellmeier W Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of CD4/CD8 lineage choice. Adv. Immunol 110, 71–110 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He X et al. The zinc finger transcription factor Th-POK regulates CD4 versus CD8 T-cell lineage commitment. Nature 433, 826–833 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun G et al. The zinc finger protein cKrox directs CD4 lineage differentiation during intrathymic T cell positive selection. Nat. Immunol 6, 373–381 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taniuchi I et al. Differential requirements for Runx proteins in CD4 repression and epigenetic silencing during T lymphocyte development. Cell 111, 621–633 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato T et al. Dual functions of Runx proteins for reactivating CD8 and silencing CD4 at the commitment process into CD8 thymocytes. Immunity 22, 317–328 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egawa T, Tillman RE, Naoe Y, Taniuchi I & Littman DR The role of the Runx transcription factors in thymocyte differentiation and in homeostasis of naive T cells. J. Exp. Med 204, 1945–1957 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singer A New perspectives on a developmental dilemma: the kinetic signaling model and the importance of signal duration for the CD4/CD8 lineage decision. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14, 207–215 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Littman DR How Thymocytes Achieve Their Fate. J. Immunol. 196, 1983–1984 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brugnera E et al. Coreceptor reversal in the thymus: signaled CD4+8+ thymocytes initially terminate CD8 transcription even when differentiating into CD8+ T cells. Immunity 13, 59–71 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu Q, Erman B, Bhandoola A, Sharrow SO & Singer A In vitro evidence that cytokine receptor signals are required for differentiation of double positive thymocytes into functionally mature CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med 197, 475–487 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park JH et al. Signaling by intrathymic cytokines, not T cell antigen receptors, specifies CD8 lineage choice and promotes the differentiation of cytotoxic-lineage T cells. Nat. Immunol. 11, 257–264 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz G et al. T cell receptor stimulation impairs IL-7 receptor signaling by inducing expression of the microRNA miR-17 to target Janus kinase 1. Sci. Signal 7, ra83 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egawa T & Littman DR ThPOK acts late in specification of the helper T cell lineage and suppresses Runx-mediated commitment to the cytotoxic T cell lineage. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1131–1139 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luckey MA et al. The transcription factor ThPOK suppresses Runx3 and imposes CD4(+) lineage fate by inducing the SOCS suppressors of cytokine signaling. Nat. Immunol 15, 638–645 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCaughtry TM, Wilken MS & Hogquist KA Thymic emigration revisited. J. Exp. Med. 204, 2513–2520 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bosselut R, Guinter TI, Sharrow SO & Singer A Unraveling a revealing paradox: Why major histocompatibility complex I-signaled thymocytes “paradoxically” appear as CD4+8lo transitional cells during positive selection of CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med 197, 1709–1719 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu Q et al. Cytokine signal transduction is suppressed in preselection doublepositive thymocytes and restored by positive selection. J. Exp. Med 203, 165–175 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanada T et al. A mutant form of JAB/SOCS1 augments the cytokine-induced JAK/STAT pathway by accelerating degradation of wild-type JAB/CIS family proteins through the SOCS-box. J. Biol. Chem 276, 40746–40754 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiest DL et al. Regulation of T cell receptor expression in immature CD4+CD8+ thymocytes by p56lck tyrosine kinase: basis for differential signaling by CD4 and CD8 in immature thymocytes expressing both coreceptor molecules. J. Exp. Med 178, 1701–1712 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stepanek O et al. Coreceptor scanning by the T cell receptor provides a mechanism for T cell tolerance. Cell 159, 333–345 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Erman B et al. Coreceptor signal strength regulates positive selection but does not determine CD4/CD8 lineage choice in a physiologic in vivo model. J. Immunol 177, 6613–6625 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chong MM et al. Suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 is a critical regulator of interleukin-7-dependent CD8+ T cell differentiation. Immunity 18, 475–487 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van De Wiele CJ et al. Thymocytes between the beta-selection and positive selection checkpoints are nonresponsive to IL-7 as assessed by STAT-5 phosphorylation. J. Immunol 172, 4235–4244 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang L et al. Distinct functions for the transcription factors GATA-3 and ThPOK during intrathymic differentiation of CD4(+) T cells. Nat. Immunol 9, 1122–1130 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tarakhovsky A et al. A role for CD5 in TCR-mediated signal transduction and thymocyte selection. Science 269, 535–537 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Constantinides MG & Bendelac A Transcriptional regulation of the NKT cell lineage. Curr. Opin. Immunol 25, 161–167 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Itano A et al. The cytoplasmic domain of CD4 promotes the development of CD4 lineage T cells. J. Exp. Med. 183, 731–741 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yin X et al. CCR7 expression in developing thymocytes is linked to the CD4 versus CD8 lineage decision. J. Immunol. 179, 7358–7364 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saini M et al. Regulation of Zap70 expression during thymocyte development enables temporal separation of CD4 and CD8 repertoire selection at different signaling thresholds. Sci. Signal 3, ra23 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu W et al. Continued RAG expression in late stages of B cell development and no apparent re-induction after immunization. Nature 400, 682–687 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.