Abstract

Exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals has been associated with compromised testosterone production leading to abnormal male reproductive development and altered spermatogenesis. In vitro high-throughput screening (HTS) assays are needed to evaluate risk to testosterone production, yet the main steroidogenesis assay currently utilized is a human adrenocortical carcinoma cell line, H295R, which does not synthesize gonadal steroids at the same level as the gonads, thus limiting assay sensitivity. Here, we propose a complementary assay using a highly purified rat Leydig cell assay to evaluate the potential for chemical-induced alterations in testosterone production by the testis. We evaluated a subset of chemicals that failed to decrease testosterone production in the HTS H295R assay. The chemicals examined fit into one of two categories based on changes in substrates upstream of testosterone in the adrenal steroidogenic pathway (17α-hydroxyprogesterone and 11-deoxycorticosterone) that we predicted should have elicited a decrease in testosterone production. We found that 85% of 20 test chemicals examined inhibited Leydig cell testosterone production in our assay. Importantly, we adopted a 96-well format to increase throughput and efficiency of the Leydig cell assay. We identified a selection criterion based on the AC50 values for 17α- hydroxyprogesterone and 11-deoxycorticosterone generated from the HTS H295R assay that will help prioritize chemicals for further testing in the Leydig cell screen. We hypothesize that the greater dynamic range of testosterone production and sensitivity of the Leydig cell assay permits the detection of small, yet significant, chemical-induced changes not detected by the HTS H295R assay.

Keywords: Leydig cells, testosterone, testis, adrenal, cell culture, endocrine disruptors, gonadal steroids, male infertility

Summary Sentence

The greater dynamic range of testosterone production in a primary rat Leydig cell assay permitted detection of chemical-induced testosterone inhibition thatwas not detected by the high-throughput screening format of the H295R steroidogenesis assay.

Introduction

The US Environmental Protection Agency’s (US EPA) Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program (EDSP) is tasked with evaluating pesticides, chemicals, and environmental contaminants for potential endocrine disrupting effects that could be hazardous to human and wildlife health. The Endocrine Society defines endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) as “chemicals that mimic, block, or interfere with hormones in the body’s endocrine system” [1]. Much of the more recent in vitro research on EDCs has focused on compound interaction with various hormone receptors and cellular signaling pathways; however, it is evident that EDCs can target the steroid hormone biosynthesis pathway as well [2–5]. Alterations in steroidogenic hormone action have been associated with developmental defects as well as dysfunction of the reproductive system [6, 7]. For decades, epidemiological data have been suggesting that semen quality has been declining. Both decreases in sperm production and sperm quality have been reported [8, 9]. This declining trend in semen quality has been linked to human exposure to EDCs during reproductive development as well as during adulthood [10]. Compromised testosterone production in the fetal or adult testis can lead to abnormal male reproductive development, quantitative and qualitative alterations in spermatogenesis, and subsequent reduced fertility [11]. Research is needed to identify EDCs in the environment that have the potential to disrupt steroid hormone biosynthesis, and if so, determine whether these chemicals pose risks to the reproductive health of humans and wildlife.

The US EPA’s EDSP Tier 1 Screening Battery includes two in vitro assays that evaluate chemical-induced alterations in steroidogenesis [12]. A cell-free human recombinant microsome assay assesses aromatase (EDSP Test Guideline 890.1200), the rate-limiting enzyme required for the conversion of androgens to estrogens, but this assay is limited in scope as it evaluates the potential for inhibition of only estrogen synthesis within the steroidogenic pathway. The cell-basedH295R steroidogenesis assay (EDSP Test Guideline 890.1550) utilizes a human adrenocortical carcinoma cell line to evaluate chemical-induced alterations in both 17β-estradiol and testosterone production. The H295R cell line has the characteristics of zonally undifferentiated fetal adrenal cells, and as a result, maintains all of the enzymes required to synthesize steroid hormones from each of the three distinct zones found in the adult adrenal cortex [13].

Numerous investigators have utilized the H295R cell line as a rapid in vitro screen to evaluate toxicant-induced effects on adrenocortical steroidogenesis [14–17]. The H295R steroidogenesis assay has been validated by both the EPA (EDSP Test Guideline 890.1550) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (OECD Test Guideline 456) [18] for the assessment of two major reproductive hormones, i.e., 17β-estradiol and testosterone. Investigators in the National Center for Computational Toxicology (NCCT) within the US EPA recently proposed the application of a high-throughput screening (HTS) adapted version of the OECD H295R steroidogenesis assay for inclusion in the ToxCast program [19]. In the high-throughput H295R steroidogenesis assay (HTS H295R), cells are cultured in a 96-well format and a panel of 13 hormones is measured using HPLC-MS/MS. This permits the evaluation of a greater number of chemicals and measurement of multiple steroid hormones across four hormone classes (progestogens, glucocorticoids, androgens, and estrogens), which in theory may elucidate different mechanisms of action of chemical-induced alterations in adrenal steroidogenesis.

Despite the novel capabilities of the HTS H295R assay, it is limited in its ability to accurately predict chemical-induced alterations in gonadal sex steroid hormones. The function of the potent sex steroids, 17β-estradiol and testosterone, in the normal human adult adrenal is not well understood, and importantly these steroids are not synthesized at the same levels as in the gonads [20]. Previous investigators have reported the production of 8 ng of testosterone/106 H295R cells cultured over a 48-h incubation period [14]. In contrast, unstimulated highly purified rat Leydig cells can produce ~30 ng of testosterone/106 cells over a 3-h incubation period [21]. Production of 17β-estradiol is even weaker than testosterone in the H295R cell line (reportedly 6-fold less than testosterone), and in fact, represents a known limitation of the H295R assay [14, 22]. The resulting lower dynamic range of 17β-estradiol production, and thus lower assay sensitivity, makes the identification of weak inhibitors difficult [14, 22]. Arguably, there is a need for sensitive and biologically relevant HTS gonadal-based assays to directly measure chemical induced alterations in sex steroid hormone synthesis and provide a better prediction of potential impact on gonadal function.

Here, we propose a complementary assay to screen for potential chemical-induced alterations in testosterone production by the testis using a highly purified rat Leydig cell assay. Highly purified rat Leydig cells, resulting from a well-established multistep isolation procedure, produce hundreds of nanograms of testosterone on stimulation by physiological levels of luteinizing hormone (LH) [21, 23]. The testosterone produced by these cells is impressive compared to the testosterone produced by other readily available Leydig cell lines [23–27]. This attribute permits a large dynamic range with inherent sensitivity to identify potent as well as modest inhibitors of testosterone production. Because purified rat Leydig cells are LH responsive, the evaluation of biologically relevant LH-stimulated alterations in testosterone production also is permitted. Given these attributes, we hypothesized that a significant number of chemicals that were not detected as inhibitors of testosterone synthesis in the H295R assay would decrease testosterone production by LH-stimulated Leydig cells, and therefore be identified as probable EDCs.

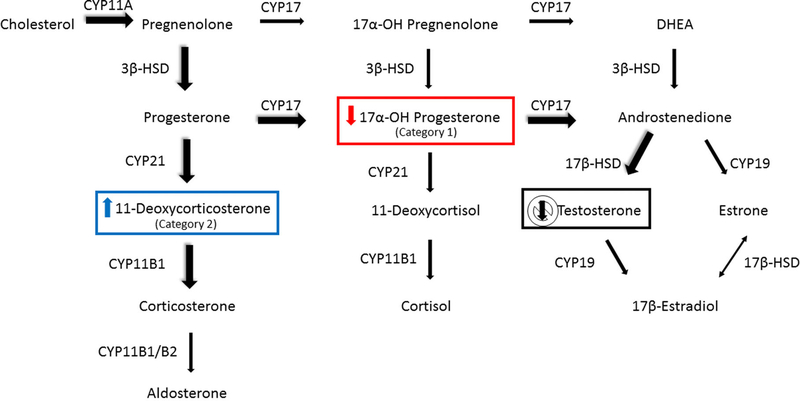

To test this hypothesis, we evaluated a subset of chemicals that failed to decrease testosterone production in the HTS H295R assay, despite changes in the concentrations of substrates upstream of testosterone that would be expected to cause decreased testosterone production. The chemicals selected fit into one of two categories based on consistent changes that we predicted should have resulted in decreased testosterone production (Figure 1). Category 1 test chemicals decreased 17α-hydroxyprogesterone with no corresponding decrease in testosterone production. Due to the substrate-dependent nature of steroidogenesis, a decrease in this upstream substrate would decrease testosterone. Category 2 test chemicals induced 11-deoxycorticosterone synthesis with no decrease in testosterone production. An increase in 11-deoxycorticosterone should lead to an increase in corticosterone, which in turn is reported to decrease testosterone biosynthesis via inhibition of steroidogenic enzymes such as hydroxylase/lyase [28–30].

Figure 1.

Human adrenal steroidogenesis pathway showing mineralocorticoid, glucocorticoid, and androgen synthesis. Chemicals were chosen for screening in the Leydig cell assay based on observed changes in substrates upstream of testosterone synthesis that were detected by the HTS H295R steroidogenesis assay. Category 1 chemicals elicited a decrease in 17α-hydroxyprogesterone and did not decrease testosterone. Category 2 chemicals induced 11-deoxycorticosterone synthesis but did not decrease testosterone synthesis. The predominant pathways to corticosterone and testosterone in the rat are depicted with the large, shadowed arrows. Abbreviations: CYP11A1, cholesterol side chain cleavage; CYP17, 17α-hydroxylase/17, 20 lyase; 3β-HSD, 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-D 5,4 isomerase; CYP21, 21-hydroxylase; CYP11B1, 11β-hydroxylase; CYP11B1/B2, 11β/18-hydroxylase; 17β-HSD, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase; CYP19, aromatase.

The objective of our study was to determine whether a highly purified rat Leydig cell assay could serve as a complement to the HTS H295R assay to assess the potential for chemical-induced impacts on LH-stimulated testosterone production by the testis. Together, these two assays would provide a comprehensive assessment of chemicalinduced alterations in both gonadal and adrenal androgen production. After evaluating the initial subset of chemicals described above in a well-established 24-well format, we adapted the assay to a moderate throughput 96-well format formore efficient screening. Finally, we have identified a selection criterion for chemicals that should be tested in the Leydig cell assay.

Materials and methods

Animal acquisition and housing conditions

All animal work was completed following review by the US EPA National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The US EPA National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory is an AAALAC-accredited institution. Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (~70 days of age upon arrival; ~90–120 days of age at Leydig cell isolation) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Raleigh, NC) and housed on a 12:12 light cycle under controlled conditions (temperature [20–24°C], humidity [40–50%]).

Leydig cell isolation

Highly purified rat Leydig cells were isolated following a modified version [25] of a validated multistep procedure [21]. Briefly, the isolation involved perfusing the vasculature of the testis via the testicular artery with collagenase and dispase, subsequent collagenase/dispase digestion of the parenchyma, retention of Leydig cell clumps in a sedimentation buffer containing 1% bovine serum albumin, removal of sperm and small germ cells by centrifugal elutriation, and finally recovery of 98% pure Leydig cells following density gradient Percoll centrifugation. Isolation yields from six rats (12 testes) ranged from 12 to 18 × 106 Leydig cells.

Chemical selection

Chemicals (Table 1) were selected based on the reported results of the HTS H295R steroidogenesis assay [19]. Category 1 chemicals included those that elicited a decrease in 17α-hydroxyprogesterone with no corresponding decrease in testosterone production. Category 2 chemicals included those that elicited an increase in 11- deoxycorticosterone with no decrease in testosterone production.

Table 1.

Chemical categorization, identification, CAS number, purity, and source.

| Category based on H295R substrates | Chemical name | CAS no. | Purity | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | Bisphenol A | 80-05-7 | 99.9 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| x | Prochloraz | 67747-09-5 | 99.1 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| x | Dexamethasone | 50-02-2 | 99.2 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| 1 | Corticosterone | 50-22-6 | >98.5 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| 1 | Cycloheximide | 66-81-9 | 98 | EMD Millipore |

| 1 | Esfenvalerate | 66230-04-4 | 99.5 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| 1 | 17α-Ethynylestradiol | 57-63-6 | 99.8 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| 1 | Finasteride | 98319-26-7 | 99.6 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| 1 | Flufenoxuron | 101463-69-8 | 98.1 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| 1 | Flusilazole | 85509-19-9 | 99.8 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| 1 | Metconazole | 125116-23-6 | 99.4 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| 1 | Permethrin | 52645-53-1 | 98.8 (isomer mix) | Sigma-Aldrich |

| 1 | Simvastatin | 79902-63-9 | 99 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| 1 | Spirodiclofen | 148477-71-8 | 99.5 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| 1 | Tamoxifen citrate | 54965-24-1 | 99.7 | USA Pharmacopeia |

| 1 | 3,4,4|-Trichlorocarbanilide | 101-20-2 | 98.9 | Aldrich |

| 1 | Triphenyl phosphate | 115-86-6 | 99.9 | Aldrich |

| 2 | Anilazine | 101-05-3 | 99.9 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| 2 | 4-Chloro-1,2-diaminobenzene | 95-83-0 | 98.4 | Aldrich |

| 2 | 1,4-Dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid | 31519-22-9 | 99.3 | Aldrich |

| 2 | Dimethipin | 55290-64-7 | 99 | Supelco Analytical |

| 2 | Hydroquinone | 123-31-9 | 100.2 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| 2 | Prednisone | 53-03-2 | 99.8 | Sigma-Aldrich |

We used the established 24-well format of the Leydig cell assay [21, 25] to perform an initial evaluation of a subset of category 1 (corticosterone, esfenvalerate, metconazole, permethrin, simvastatin) and category 2 (anilazine, hydroquinone, prednisone) chemicals. Dexamethasone was also selected as it decreased testosterone production in the HTS H295R assay. This served as an interassay control for comparison between the H295R and Leydig cell assays. Chemicals that decreased testosterone production significantly in the 24-well format of the Leydig cell assay were then reassayed in a 96- well format to confirm consistent results between the two plate formats. After confirming comparable responses in the 24- and 96-well formats, a second subset of chemicals was selected for evaluation in the 96-well format. These chemicals were selected based on a pattern in the AC50 results from the H295R assay that effectively differentiated the responders (i.e., those chemicals that decreased testosterone production in the Leydig cell assay but did not in the H295R assay) from the nonresponders (i.e., those chemicals that did not decrease testosterone production in either assay). The additional chemicals included cycloheximide, 17α-ethynylestradiol, finasteride, flufenoxuron, flusilazole, spirodiclofen, tamoxifen citrate, 3,4,4_-trichlorocarbanilide, and triphenyl phosphate from category 1 and 4-chloro-1,2-diaminobenzene, 1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid, and dimethipin from category 2. Similar to dexamethasone, bisphenol A and prochloraz were added as additional interassay controls because they also decreased testosterone production in the H295R assay and were previously shown to decrease testosterone by highly purified LH-stimulated Leydig cells (Gary Klinefelter, unpublished data).

Cell culture design

All chemicals were solubilized in DMSO at 100 mM with the exception of simvastatin and prochloraz, which were solubilized at 10 mM. A minimum of two independent experimental replicates (i.e., different isolations of Leydig cells) were performed for each chemical dosing range. Each chemical was originally tested in duplicate wells over six concentrations ranging from 0 to 100 μM, except simvastatin (0–10 μM) and prochloraz (0–1 μM). Previous studies have indicated cell viability issues at higher concentrations for simvastatin [25] and prochloraz (Gary Klinefelter, unpublished data). Cell viability was compromised at higher concentrations of tamoxifen citrate and 3,4,4’-trichlorocarbanilide, and as a result, the dosing range was lowered for both (0–1 μM). The response of simvastatin (0–10 μM) served as a positive control for the Leydig cell assay based on previous results [25] and was run in each experimental replicate. Continuous maximum LH stimulation was achieved with highly purified ovine LH (NIDDK-oLH-26; a gift from the NIDDK National Hormone & Pituitary Program) at a concentration of 100 ng/mL.

Cell culture medium consisted of phenol-red free Medium 199 for cell culture (Gibco, 11043–023) supplemented with 2 g/L protease free bovine serum albumin for cell culture (Sigma, A3294), 10 mL/L insulin-transferrin-selenium-sodium pyruvate (100X, Gibco, 51300– 044), 10 mL/L sodium pyruvate (100 mM, Gibco, 11360–070), 10 mL/LMEMnonessential amino acids solution (100X,Gibco, 11140– 050), 10 mL/L GlutaMax supplement (100X, Gibco, 35050–061), and 12mg/L gentamicin (Sigma, G1272). For the 24-well format, the total volume in each well was 1.0 mL and included, in order of addition, the following: culture medium, Leydig cells (cell number held constant across plate per experimental replicate and ranged from 125 000 to 150 000 cells/well/replicate), highly purified ovine LH at a concentration for continuous maximal stimulation (100 ng/mL), and chemical doses administered in DMSO at 0.1% v/v per well immediately after plating. The 96-well format was proportionally adjusted according to well area and volume and optimized for performance using cell plating density and total DMSO concentration as parameters (data not shown). For the 96-well format, the total volume in each well was 0.3 mL and included, in order of addition, the following: culture medium, Leydig cells (30 000 cells/well/replicate), highly purified ovine LH at a concentration for continuous maximal stimulation (100 ng/mL), and chemical doses administered in DMSO at 0.3% v/v per well immediately after plating.

Leydig cells were cultured overnight (~18 h) at 34°C in 5% CO2. The next day, medium was carefully aspirated from each well 0.8-mL 24-well format; 0.15-mL 96-well format), transferred to a microcentrifuge tube, and stored at −80°C for future testosterone quantification.

Cell viability/toxicity assessment

Cells were first visually inspected under a stereomicroscope for consistent morphology. Additionally, cell viability was quantified for each cell culture plate using the LIVE/DEAD Viability/Cytotoxicity kit for mammalian cells (Molecular Probes, L-3224). Testosterone data were excluded from statistical analysis when chemical exposure resulted in cell viability less than 75% of DMSO control.

Radioimmunoassay evaluation of testosterone production

Media from the wells were thawed and total testosterone was quantified using radioimmunoassay according to manufacturer’s instructions (coat-a-count, TESTO-US, ALPCO). The reported limit of detection for testosterone was 0.09 ng/mL. Media from duplicate wells of each concentration were diluted 1:10 and assayed. The technical duplicates were averaged to provide each experimental replicate value.

Statistical analysis

Testosterone concentration data were analyzed for differences from solvent controls using two-way ANOVA (PROC GLM; SAS 9.4) with least square means analysis and using experimental replicate as a covariate. Significant (P < 0.05) differences from solvent controls were evaluated using a 2-tailed Dunnett test. Prior to conducting this statistical analysis, the data were first evaluated for homogeneity of variance by either a Bartlett or Levene test, where appropriate. The lowest observed effect concentration (LOEC) was defined as the lowest concentration at which a statistically significant decrease in testosterone was observed for each chemical. The dynamic range of testosterone production in the H295R assay and the 24- and 96-well formats of the Leydig cell assay were evaluated using two-tailed t-tests. Prior to conducting this statistical analysis, all data were log transformed to correct for heterogeneity of variance.

Results

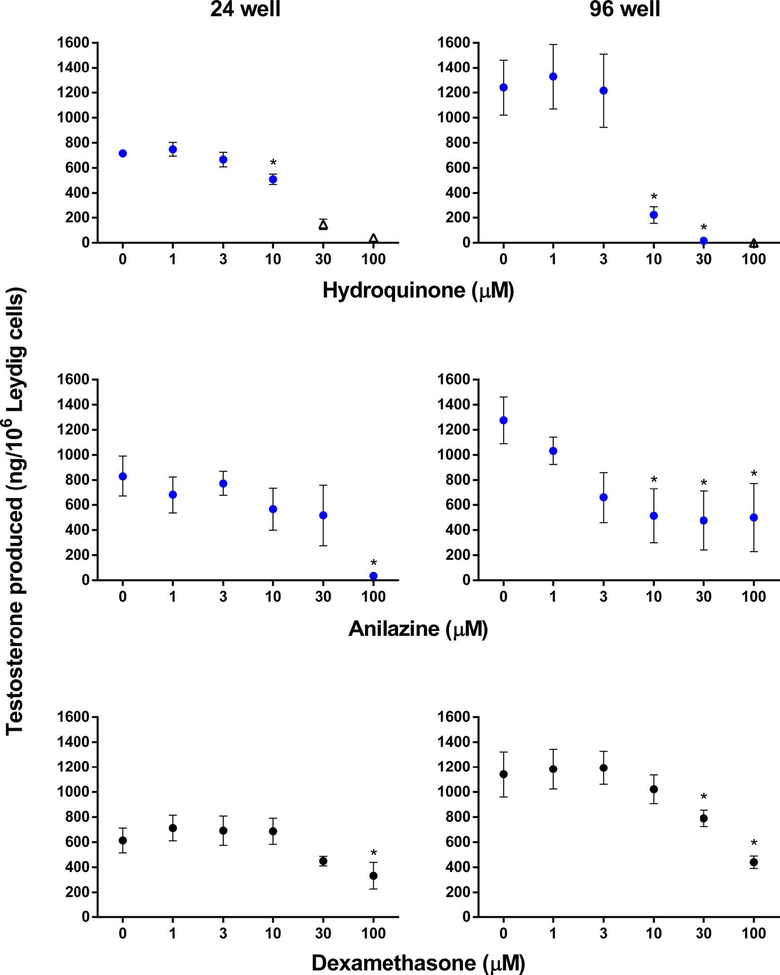

Based on our predefined chemical categories, we initially evaluated eight test chemicals and dexamethasone for testosterone inhibition in the established 24-well format. Five of the nine chemicals decreased testosterone production significantly. Chemicals that significantly decreased testosterone production in the Leydig cell assay included simvastatin and metconazole from category 1 (Figure 2), hydroquinone and anilazine from category 2 (Figure 3), and the interassay control, dexamethasone (Figure 3). The LOECs were 0.1, 3, 10, 100, and 100 μM for simvastatin, metconazole, hydroquinone, anilazine and dexamethasone, respectively. Esfenvalerate, permethrin, prednisone, and corticosterone did not inhibit testosterone production in the 24-well format, and these results were in agreement with the results from the HTS H295R assay [19]. Corticosterone, however, was close to significance (P < 0.06) at 100 μM in the Leydig cell assay (Figure 2). We classified simvastatin, metconazole, anilazine, and hydroquinone as responders, or chemicals that decreased testosterone production in the Leydig cell assay but did not in the H295R assay [19].

Figure 2.

Comparison of Leydig cell assay results for 24- vs 96-well formats for category 1 chemicals. Testosterone production (ng/106 Leydig cells) was assessed after an 18-h incubation. Data are mean ± SEM for ≥2 independent replicates. Significant differences (∗) from 0 μM were set at P < 0.05. Data were excluded (indicated by open triangle markers) if cell viability was less than 75% of control.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Leydig cell assay results for 24- vs 96-well formats for category 2 chemicals and interassay control, dexamethasone. Testosterone production (ng/106 Leydig cells) was assessed after an 18-h incubation. Data are mean ± SEM for ≥2 independent replicates. Significant differences (∗) from 0 μM were set at P < 0.05. Data were excluded (indicated by open triangle markers) if cell viability was less than 75% of control.

A second objective of this study was to adapt the Leydig cell assay to a 96-well format. For this, we optimized the performance of the 96-well assay and re-evaluated the original four responder chemicals, as well as dexamethasone and corticosterone, as corticosterone produced near significant decreases in testosterone production at the 100 μM concentration. The ability of the four responder chemicals to decrease testosterone production by Leydig cells was confirmed in the 96-well format of the Leydig cell assay (Figures 2 and 3). Although corticosterone did not decrease testosterone production significantly in the 24-well format, it did produce a significant decrease in the 96-well assay at the highest concentration tested and was classified as a responder (Figure 2). The LOECs were 0.1, 1, 10, 10, 30, and 100 μM for simvastatin, metconazole, hydroquinone, anilazine, dexamethasone, and corticosterone, respectively (Table 2). Esfenvalerate, permethrin, and prednisone were confirmed as nonresponders, as they did not significantly inhibit testosterone production in the Leydig cell assay, and these results were in agreement with those obtained from the HTS H295R assay. Thus, five of the eight chemicals that were negative for decreased testosterone in the H295R assay were positive in the 96-well Leydig cell assay and were classified as responders.

Table 2.

LOECs of category 1, category 2, and interassay control chemicals identified in the 96-well format of the Leydig cell assay.

| Category 1 | LOEC (μM) |

| Tamoxifen citrate | 0.01 |

| 3,4,4’-Trichlorocarbanilide | 0.1 |

| Simvastatin | 0.1 |

| Cycloheximide | 1 |

| Metconazole | 1 |

| Flufenoxuron | 1 |

| Spirodiclofen | 1 |

| Flusilazole | 10 |

| 17α-Ethynylestradiol | 30 |

| Corticosterone | 100 |

| Finasteride | 100 |

| Triphenyl phosphate | 100 |

| Category 2 LOEC | LOEC (μM) |

| Dimethipin | 1 |

| 1,4-Dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid | 3 |

| 4-Chloro-1,2-diaminobenzene | 3 |

| Anilazine | 10 |

| Hydroquinone | 10 |

| Interassay controls | LOEC (μM) |

| Prochloraz | 0.3 |

| Bisphenol A | 30 |

| Dexamethasone | 30 |

A third objective of this study was to identify selection criteria that would differentiate the responders from the nonresponders for potential impacts on testosterone production. The criteria would identify chemicals assayed in the H295R assay that would benefit from being re-evaluated in the complementary Leydig cell assay. Examination of the 17α-hydroxyprogesterone and 11-deoxycorticosterone data from the H295R assay indicated that those chemicals that significantly decreased testosterone production by Leydig cells, but not the H295R, had relatively low AC50 values (of ~3 μM or less) for decreased 17α-hydroxyprogesterone or increased 11-deoxycorticosterone (Table 3).

Table 3.

HTSH295RAC50 (μM) values for 17α-hydroxyprogesterone and 11-deoxycorticosterone showing that responders in the 96-well format of the Leydig cell assay have AC50 values <3 μM.

| Responders | AC50 (μM) |

Non responders | AC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Category 1: AC50 for 17α-hydroxyprogesterone in the HTS H295R assay | |||

| Metconazole | 0.09 | Permethrin | 9.99 |

| Cycloheximide | 0.10 | Esfenvalerate | 27.50 |

| Tamoxifen citrate | 0.14 | ||

| 17α-Ethynylestradiol | 0.33 | ||

| 3,4,4|-Trichlorocarbanilide | 0.37 | ||

| Flusilazole | 0.38 | ||

| Simvastatin | 0.72 | ||

| Flufenoxuron | 1.09 | ||

| Finasteride | 1.13 | ||

| Triphenyl phosphate | 1.81 | ||

| Spirodiclofen | 2.01 | ||

| Corticosterone | 44.16 | ||

| Category 2: AC50 for 11-deoxycorticosterone in the HTS H295R assay | |||

| 1,4-Dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid | 0.43 | Prednisone | 39.51 |

| Dimethipin | 1.59 | ||

| 4-Chloro-1,2-diaminobenzene | 2.69 | ||

| Anilazine | 2.84 | ||

| Hydroquinone | 3.20 | ||

Corticosterone does not follow <3 μM pattern.

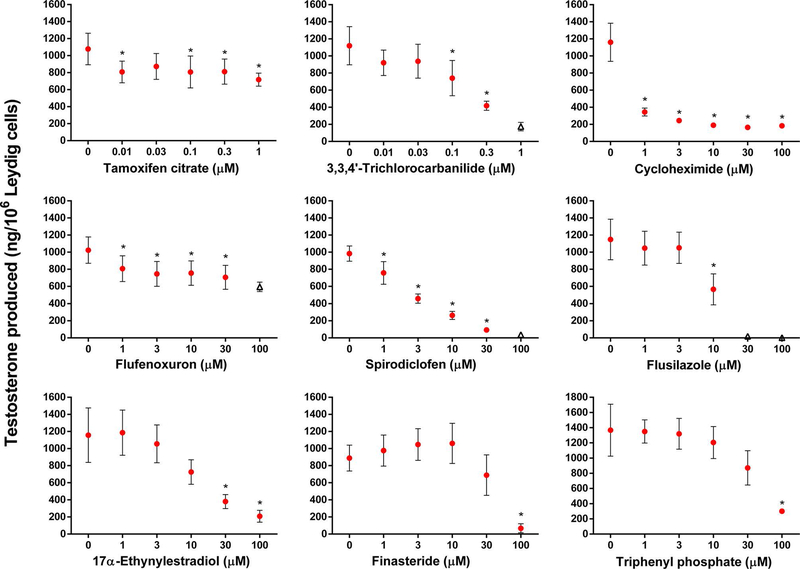

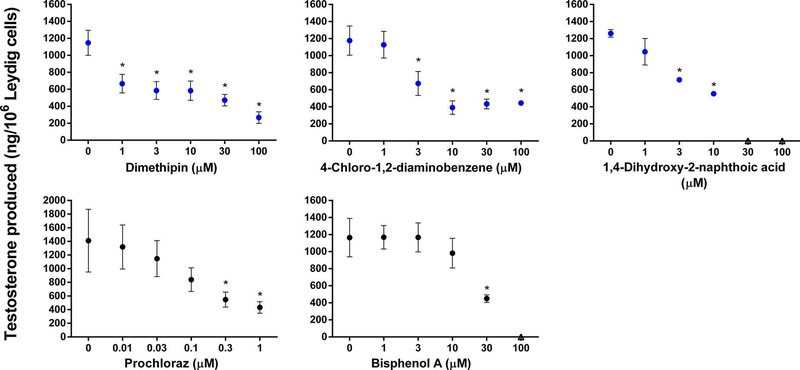

We selected a second subset of 12 chemicals that met the selection criteria for testing in the 96-well format. All 12 test chemicals significantly decreased testosterone production in the Leydig cell assay as hypothesized by the selection criteria. LOECs (Table 2) were determined for nine category 1 (Figure 4) and three category 2 (Figure 5) chemicals. Both interassay controls, prochloraz and bisphenol A, also significantly reduced testosterone production by Leydig cells (Figure 5) with LOECs of 0.3 and 30 μM, respectively (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Category 1 chemicals that decreased testosterone production in the 96-well Leydig cell assay but not in the HTS H295R assay. Testosterone production (ng/106 Leydig cells) was assessed after an 18-h incubation. Data are mean ± SEM for ≥2 independent replicates. Significant differences (∗) from 0 μM were set at P < 0.05. Data were excluded (indicated by open triangle markers) if cell viability was less than 75% of control.

Figure 5.

Category 2 chemicals that decreased testosterone production in the 96-well Leydig cell assay but not in the HTS H295R assay. Interassay controls, prochloraz and bisphenol A, are also shown. Testosterone production (ng/106 Leydig cells) was assessed after an 18-h incubation. Data are mean ± SEM for ≥2 independent replicates. Significant differences (∗) from 0 μM were set at P < 0.05. Data were excluded (indicated by open triangle markers) if cell viability was less than 75% of control.

Discussion

Over the past few decades, there has been a debate regarding the possibility that exposure to environmental chemicals is contributing to a decline in semen quality in men [6, 31, 32]. Both environmental chemicals and pharmaceuticals have been linked to compromised testosterone production in the testis. It is reasonable to assume that exposure to any agent that significantly suppresses testosterone production could compromise spermatogenesis and epididymal sperm maturation resulting in reductions in both sperm numbers and sperm quality. Thus, chemically induced decreases in testosterone by adult Leydig cells can result in a phenotype typical of primary hypogonadism, low testosterone despite normal LH levels [33]. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that many of the chemicals that alter testosterone production by the adult Leydig cell also are likely to alter testosterone production by fetal Leydig cells. In addition to direct alteration to fetal Leydig cell testosterone production, it has been hypothesized that fetal stem Leydig cells compromised by specific gestational exposures will populate a testis containing adult Leydig cells with limited steroidogenic competence [34].

To identify chemicals with a potential to alter endocrine mediated key events such as steroidogenesis, high-throughput screens have been implemented through EPA’s ToxCast program [35, 36, 37]. Karmaus et al. [19] recently suggested the addition of an HTS version of the H295R steroidogenesis assay to the ToxCast assay battery. However,H295R cells have limitations as they suboptimally respond to their endogenous ligand, adrenocorticotropic hormone [38], as well as to LH [39]. Moreover, while H295R cells contain all the adrenal steroidogenic enzymes, they produce low levels of testosterone compared to primary Leydig cells. This limits the sensitivity needed to identify significant chemical-induced alterations in testosterone production. Furthermore, limitations exist for many Leydig cell lines. The transformed murine MA-10 Leydig cell line does not contain the enzymes necessary for terminal testosterone production and cannot produce steroid beyond progesterone [24]. The rat R2C Leydig cell line lacks the LH /chorionic gonadotropin receptor and is therefore nonresponsive to LH [26]. The murine BLTK1 cell line contains the complete suite of steroidogenic enzymes necessary for testosterone synthesis and is LH responsive; however, it too is limited by the low quantities of testosterone produced [27].

We successfully demonstrated that the highly purified Leydig cell assay was capable of detecting chemical-induced inhibition in testosterone production that was not detected by the HTS H295R assay. In total, we examined 20 test chemicals that did not reduce testosterone in the H295R assay and found that 85% of them inhibited Leydig cell testosterone production in our assay. Importantly, we identified a selection criterion based on the H295R AC50 values for 17α-hydroxyprogesterone and 11-deoxycorticosterone that will help prioritize chemicals for further testing. All 12 chemicals selected based on this criterion decreased testosterone production in the Leydig cell assay. This demonstrates that the AC50 criterion could be used as a guide to select compounds for further testing.

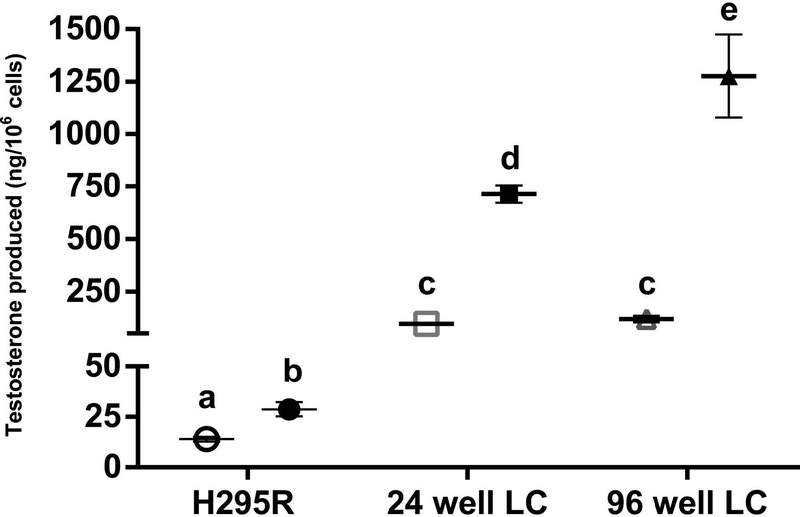

The disparity between the results of the H295R and Leydig cell assays emphasizes the importance of using Leydig cells for detecting chemical-induced alterations in gonadal testosterone production. We hypothesize that the far greater dynamic range of testosterone production characteristic of the LH-stimulated Leydig cell affords the sensitivity required to detect small yet significant chemical-induced changes. Basal and forkolin-stimulated testosterone production were evaluated during international validation of the H295R steroidogenesis assay [22] (Angela Buckalew, personal communication), and the dynamic range of H295R cells was deduced (Figure 6). Forskolin stimulation (10 μM) increased testosterone production in theH295R assay to only 29 ng/106 cells compared to 568–809 ng/106 Leydig cells and 738–1902 ng/106 Leydig cells in LH-stimulated 24- and 96-well formats. While there was no difference in unstimulated testosterone production between the two plate formats, the LH responsiveness (i.e., LH-stimulated testosterone vs unstimulated testosterone) was increased 7.4-fold and 10.8-fold in the 24- and 96-well formats, respectively. In the 96-well format, we were able to detect statistically significant decreases in testosterone production at lower concentrations for 3 of 5 test chemicals evaluated in both 24- and 96-well formats (metconazole, corticosterone, and anilazine).

Figure 6.

Comparison of the dynamic range of testosterone production between the H295R steroidogenesis assay (Angela Buckalew, personal communication), the 24-well format of the Leydig cell (LC) assay, and the 96-well format of the Leydig cell assay. Markers represent mean ± SEM testosterone production (ng/106 cells) without (empty markers) and with stimulation (filled markers), respectively (10 μM forskolin = H295R assay; 100 ng/mL LH = LC assay) for two to eight independent replicates. Significant differences (P < 0.05) between unstimulated and stimulated testosterone production and differences between groups are denoted by different letters.

This study provided data demonstrating significant concentration-dependent decreases in testosterone production for 17 out of 20 chemicals (85%) that failed to decrease testosterone by H295R cells. The identification of this incidence of false negatives suggests a real need to use the Leydig cell assay as a complementary screen to capture potential impacts on gonadal steroidogenesis. Moreover, the data strongly suggest that AC50 values of approximately 3 μM or less for proximal substrates 17α- hydroxyprogesterone and 11-deoxycorticosterone are reasonable criteria to effectively select chemicals for this secondary screen with a high likelihood of detecting a significant decrease in testosterone production by Leydig cells. It can be reasoned that while there was too little testosterone produced to detect an AC50, there was sufficient 17α-hydroxyprogesterone and 11-deoxycorticosterone to detect rather low AC50 changes. A low AC50 for decreased 17α-hydroxyprogesterone would be expected to be accompanied by a decrease in testosterone. Conversely, a low AC50 for increased 11-deoxycorticosterone would be expected to be accompanied by a decrease in testosterone provided corticosterone-induced inhibition of testosterone occurs in the absence of sufficient protective 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase [40–42].

The scientific challenge at this juncture is to elucidate more proximal molecular events that lead to decreased testosterone production. The Leydig cell assay is well suited to address this. This may be achieved for example by quantifying the proximal substrates in the Leydig cell pathway. Recently, Hansen et al. [43] studied the effect of multiple serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) on testosterone production by H295R cells cultured in an unstimulated, 24-well format. Each SSRI decreased testosterone and quantification of all proximal substrates of testosterone, and multiple sites of action were identified for individual SSRIs. We can only assume that observed substrate alterations may differ between H295R cells and LH-stimulated Leydig cells since testosterone is not the main steroid produced by the H295R cell.

To our knowledge, this is the first time highly purified Leydig cells have been cultured in a 96-well format. Our results provide strong support for the addition of a highly purified Leydig cell assay to measure toxicant-induced alterations in gonadal testosterone production to complement the H295R steroidogenesis assay when either decreases in 17α-hydroxyprogesterone or increases in 11-deoxycorticosterone are observed with no decrease in testosterone. Given that a typical Leydig cell isolation yields 14–20 × 106 cells, one isolation is well suited for a minimum of 5 × 96-well plates with 30 000 Leydig cells/well to test 40 chemicals over six concentrations in duplicate.

The utility of the Leydig cell assay is best demonstrated by the results of simvastatin, which served as the positive control for the Leydig cell assay, yet did not decrease testosterone in the H295R assay. Simvastatin is perhaps the most recognized chemical of those evaluated and is a highly prescribed pharmaceutical that competitively inhibits 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase and subsequently the formation of cholesterol [44], a rate-limiting testosterone precursor. Statin use has been associated with lower peripheral blood testosterone levels in middle-aged men [45], lower serum testosterone concentrations in older men [46], and reduced Leydig cell testosterone production [25] and serum testosterone levels [47] in male rats. Recently, we have demonstrated significant decreases in testosterone measures and reduced fertility in rats exposed to simvastatin for 30 days (Klinefelter, in preparation). The H295R assay repeatedly failed to identify a reduction in testosterone production upon simvastatin exposure [19, 48]. This discrepancy highlights the importance of using a gonadal-based assay for measuring toxicant induced changes in sex steroid hormones. High-priority chemicals that are negative for decreased testosterone in the H295R assay but positive in the Leydig cell assay should be followed up in vivo to evaluate the potential for these chemicals to decrease testosterone in vivo. Even with such rigorous effort, the possibility exists that some chemicals may require paracrine/endocrine activity only achieved in vivo. Chemicals testing positive in the Leydig cell assay should also be studied using fetal testis incubations and following gestational exposure to characterize effects on the fetal Leydig cell population.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Agnus Karmaus for sharing her HTS H295R ToxCast data and helping sort through the data to develop our hypothesis and select test chemicals. We thank Vickie Wilson and Dan Villeneuve, US EPA, for their assistance with manuscript review; Angela Buckalew, US EPA, for her assistance with radioimmunoassays; and Judith Schmid, US EPA, for her statistical expertise. The US Environmental Protection Agency through its Office of Research and Development has subjected this article to Agency administrative review and approved it for publication. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement for use. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the US Environmental Protection Agency.

Grant Support: This study was conducted at the National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, US EPA, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina and was supported in part by an appointment to the Research Participation Program at the US EPA, administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the US Department of Energy and EPA.

Footnotes

Conference Presentation: This research was presented, in part, at the 56th Annual Meeting of the Society of Toxicology, 12–16 March 2017, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

References

- 1.Chemicals Endocrine-Disrupting [Internet]. Washington, DC: Endocrine Society; https://www.endocrine.org/topics/edc. Accessed 05 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanderon JT. The steroid hormone biosynthesis pathway as a target for endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Toxicol Sci 2006; 94:3–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloom M, Lin EM, Fujimoto V. Bisphenol A and ovarian steroidogenesis. Fertil Steril 2016; 106:857–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harvey P Adrenocortical endocrine disruption. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2016; 155:199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svechnikov K, Savchuk I, Morvan M-L, Antignac J-P, Bizec BL, Söder O. Phthalates exert multiple effects on leydig cell steroidogenesis horm res paediatr. 2016; 86:253–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharpe RM, Skakkebaek NE. Testicular dysgenesis syndrome: mechanistic insights and potential new downstream effects. Fertil Steril 2008; 89:e33–e38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeung BH,Wan HT, Law AY, Wong CK. Endocrine disrupting chemicals. Spermatogenesis 2011; 1:231–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rolland M, Moal JL,Wagner V, Royere D, Mouzon JD. Decline in semen concentration and morphology in a sample of 26 609 men close to general population between 1989 and 2005 in France. Hum Reprod 2013; 28:462–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sengupta P, Jr EB, Dutta S, Krajewska-Kulak E. Decline in sperm count in European men during the past 50 years. Hum Exp Toxicol 2017:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skakkebaek NE, Meyts ER-D, Louis GMB, Toppari J, Anderson A-M, Eisenberg ML, Jensen TK, Jørgensen N, Swan SH, Sapra KJ, Ziebe S, Priskorn L et al. Male reproductive disorders and fertility trends: influences of environment and genetic susceptibility Physiol Rev 2016; 96:55–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klinefelter GR. Male infertility and the environment: a plethora of associations based on a paucity of meaningful data In: Goldstein M, Schlegel P (eds.), Surgical and Medical Management of Fertility. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 2012:249–257. [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. EPA Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program Test Guidelines Series 890 [Internet]. Washington, DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency; https://www.epa.gov/test-guidelines-pesticidesand-toxic-substances/series-890-endocrine-disruptor-screening-program. Accessed 01 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gazdar AF, Oie HK, Shackleton CH, Chen T, Triche TJ, Myers CE, Chrousos GP, Brennan MF, Stein C, Rocca RVL. Establishment and characterization of a human adrenocortical carcinoma cell line that expresses multiple pathways of steroid biosynthesis. Cancer Res 1990; 50:5488–5496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hecker M, Newsted JL, Murphy MB, Higley EB, Jones PD, Wu R, Giesy JP. Human adrenocarcinoma (H295R) cells for rapid in vitro determination of effects on steroidogenesis: hormone production. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2006; 217:114–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uller °as E, Ohlsson Å, Oskarsson A. Secretion of cortisol and aldosterone as a vulnerable target for adrenal endocrine disruption - screening of 30 selected chemicals in the human H295R cell model. J Appl Toxicol 2008; 28:1045–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jumhawan U, Yamashita T, Ishida K, Fukusaki E, Bamba T. Simultaneous profiling of 17 steroid hormones for the evaluation of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in H295R cells. Bioanalysis 2017; 9:67–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strajhar P, Tonoli D, Jeanneret F, Imhof RM, Malagnino V, Patt M, Kratschmar DV, Boccard J, Rudaz S, Odermatt A. Steroid profiling in H295R cells to identify chemicals potentially disrupting the production of adrenal steroids. Toxicology 2017; 381:51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Test No. 456: H295R Steroidogenesis Assay [Internet]. Paris: OECD Publishing; http://www.oecd.org/env/test-no-456-h295r-steroidogenesisassay-9789264122642-en.htm. Accessed 01 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karmaus A, Toole C, Filer D, Lewis K. High-throughput screening of chemical effects on steroidogenesis using H295R human adrenocortical carcinoma cells. Toxicol Sci 2016; 150:323–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanderson JT. Adrenocortical toxicology in vitro: assessment of steroidogenic enzyme expression and steroid production in H295R cells In: Harvey P, Everett D, Springall C (eds.), Target Organ Toxicology Series, vol. 26 London: Informa Healthcare; 2009:175–182. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klinefelter G, Hall P, Ewing L. Effect of luteinizing hormone deprivation in situ on steroidogenesis of rat leydig cells purified by a multistep procedure12. Biol Reprod 1987; 36:769–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hecker M, Hollert H, Cooper R, Vinggaard AM, Newsted Y, Murphy M, Nellemann C, Higley E, Newsted J, Laskey J, Buckalew A, Grund S et al. The OECD validation program of the H295R steroidogenesis assay: phase 3. final inter-laboratory validation study. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2011; 18:503–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klinefelter GR, Ewing LW.Optimizing testosterone production by purified adult rat Leydig cells in vitro. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol 1988; 24:545–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ascoli M Characterization of several clonal lines of cultured ley dig tumor cells: gonadotropin receptors and steroidogenic responses. Endocrinology 1981;108:88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klinefelter G, Laskey J, Amann R. Statin drugs markedly inhibit testosterone production by rat Leydig cells in vitro: implications formen. Reprod Toxicol 2014; 45:52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stocco DM, Chen W. Presence of identical mitochondrial proteins in unstimulated constitutive steroid-producing R2C rat leydig tumor and stimulated nonconstitutive steroid-producing MA-10 mouse leydig tumor cells. Endocrinology 1991; 128:1918–1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forgacs AL, Ding Q, Jaremba RG, Huhtaniemi IT, Rahman NA, Zacharewski TR. BLTK1 murine Leydig cells: a novel steroidogenic model for evaluating the effects of reproductive and developmental toxicants. Toxicol Sci 2012; 127:391–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hales DB, Payne AH. Glucocorticoid-mediated repression of P450 scc mRNAand de novo synthesis in cultured leydig cells. Endocrinology 1989; 124:2099–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orr TE, Taylor MF, Bhattacharyya AK, Collins DC, Mann DR. Acute immobilization stress disrupts testicular steroidogenesis in adult male rats by inhibiting the activities of 17α-hydroxylase and 17,20-lyase without affecting the binding of LH/hCG receptors. J Androl 1994; 15: 302–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin H, Yuan K-M, Zhou H-Y, Bu T, Su H, Liu S, Zhu Q, Wang Y, Hu Y, Shan Y, Lian Q-Q, Wu X-Y et al. Time-course changes of steroidogenic gene expression and steroidogenesis of rat Leydig cells after acute immobilization stress. Int J Mol Sci 2014; 15:21028–21044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sweeney M, Hasan N, Soto A, Sonnenschein C. Environmental endocrine disruptors: effects on the human male reproductive system. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2015; 16:341–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levine H, Jørgensen N, Martino-Andrade A, Mendiola J, Weksler-Derri D, Mindlis I, Pinotti R, Swan SH. Temporal trends in sperm count: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Hum Reprod Update 2017; 23:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Surampudi PN, Wang C, Swerdloff R. Hypogonadism in the aging male diagnosis, potential benefits, and risks of testosterone replacement therapy. Int J Endocrinol 2012; 2012:1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kilcoyne KR, Smith LB, Atanassova N, Macpherson S,McKinnell C, Driesche SVD, Jobling MS, Chambers TJ, Gendt KD, Verhoeven G, O’Hara L, Platts S et al. Fetal programming of adult Leydig cell function by androgenic effects on stem/progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111:E1924–E1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Villeneuve DL, Crump D, Garcia-Reyero N, Hecker M, Hutchinson TH, LaLone CA, Landesmann B, Lettieri T, Munn S, Nepelska M, Ottinger MA, Vergauwen L et al. Adverse outcome pathway (AOP) development I: strategies and principles. Toxicol Sci 2014; 142:312–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Judson R, Kavlock R, Martin M, Reif D, Houck K, Knudsen T, Richard A, Tice RR, Whelan M, Xia M, Huang R, Austin C et al. Perspectives on validation of high-throughput assays supporting 21st century toxicity testing. ALTEX 2013; 30:51–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rotroff DM, Dix DJ, Houck KA, Knudsen TB, Martin MT, McLaurin KW, Reif DM, Crofton KM, Singh AV, Xia M, Huang R, Judson RS. Using in vitro high throughput screening assays to identify potential endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Environ Health Perspect 2013; 121:7–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rainey WE, Bird IM, Sawetawan C, Hanley NA, McCarthy JL, McGee EA, Wester R, Mason JI. Regulation of human adrenal carcinoma cell (NCI-H295) production of C19 steroids. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1993; 77:731–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rao C, Zhou X, Lei Z. Functional luteinizing hormone/chorionic gonadotropin receptors in human adrenal cortical H295R cells. Biol Reprod 2004;71:579–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sankar BR, Maran RM, Sudha S, Govindarajulu P, Balasubramanian K. Chronic corticosterone treatment impairs Leydig Cell 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity and LH-stimulated testosteorne production. Horm Metab Res 2000; 32:142–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ge R-S, Dong Q, Niu E-M, Sottas CM, Hardy DO, Catterall JF, Latif SA, Morris DJ, Hardy MP. 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2 in rat leydig cells: its role in blunting glucocorticoid action at physiological levels of substrate. Endocrinology 2005; 146:2657–2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rengarajan S, Balasubramanian K. Corticosterone has direct inhibitory effect on the expression of peptide hormone receptors, 11β-HSD and glucose oxidation in cultured adult rat Leydig cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2007; 279:52–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hansen CH, Larsen LW, Sørensen AM, Halling-Sørensen B, Styrishave B. The six most widely used selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors decrease androgens and increase estrogens in the H295R cell line. Toxicol In Vitro 2017; 41:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stancu C, Sima A. Statins: mechanism of action and effects. J Cellular Mol Med 2001; 5:378–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schooling CM, Yeung SLA, Freeman G, Cowling BJ. The effect of statins on testosterone in men and women, a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Med 2013; 11:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Keyser CE, de Lima FV, de Jong FH, Hofman A, de Rijke YB, Uitterlinden AG, Visser LE, Stricker BH. Use of statins is associated with lower serum total and non-sex hormone-binding globulin-bound testosterone levels in male participants of the Rotterdam study. Eur J Endocrinol 2015; 173:155–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang X, Li J, Zhou X, Guan Q, Zhao J, Gao L, Yu C, Wang Y, Zuo C. Simvastatin decreases sex hormone levels in male rats. Endocr Pract 2017; 23:175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guldvang A, Hansen CH, Weisser JJ, Halling-Sørensen B, Styrishave B. Simvastatin decreases steroid production in the H295R cell line and decreases steroids and FSH in female rats. Reprod Toxicol 2015; 58:174–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]