Abstract

Objective

To examine the relationship between disordered eating behaviour and Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) in a clinical population of adolescent girls. We hypothesized that BPD and disordered eating would be strongly associated and that this association would be partially mediated by rejection sensitivity.

Method

Participants were 73 female patients aged 11–18 presenting for mental health treatment at an outpatient psychiatry clinic in a large metropolitan hospital. Measures used in this study include the Diagnostic Interview for Borderline Personality Disorder-Revised, Borderline Personality Questionnaire and The Short Screen for Eating Disorders.

Results

Youth with BPD had significantly more disordered eating behaviour compared to controls. Of the nine facets of BPD, eight were highly correlated with disordered eating, suggesting important shared variance between the constructs of BPD and disordered eating. This study also demonstrated that rejection sensitivity significantly mediated the relationship between BPD symptoms and disordered eating.

Conclusions

This paper provides a novel association between a diagnosis of BPD in adolescents and disordered eating and the mediation effect of rejection sensitivity. These findings suggest that disordered eating should be screened in BPD samples and interventions targeting rejection sensitivity may be of clinical use.

Keywords: borderline personality disorder, adolescence, disordered eating, abandonment, rejection sensitivity

Résumé

Objectif

Examiner la relation entre le trouble du comportement alimentaire et le trouble de la personnalité limite (TPL) dans une population clinique d’adolescentes. Nous avons émis l’hypothèse que le TPL et le trouble alimentaire seraient fortement associés et que cette association serait partiellement soumise à la médiation de la sensibilité au rejet.

Méthode

Les participantes étaient 73 patientes âgées de 11 à 18 ans qui consultaient pour un traitement de santé mentale à une clinique psychiatrique ambulatoire d’un grand hôpital métropolitain. Les mesures utilisées dans cette étude comprennent l’entrevue diagnostique pour le trouble de la personnalité limite (révisé), le questionnaire de la personnalité limite et le dépistage rapide des troubles alimentaires.

Résultats

Les adolescentes souffrant du TPL avaient significativement plus de troubles du comportement alimentaire comparativement aux témoins. Sur les 9 dimensions du TPL, 8 étaient fortement corrélées au trouble alimentaire, ce qui suggère une importante variance partagée entre les structures du TPL et du trouble alimentaire, Cette étude a aussi démontré que la sensibilité au rejet est un médiateur significatif de la relation entre les symptômes du TPL et le trouble alimentaire.

Conclusions

Cet article offre une nouvelle association entre un diagnostic de TPL chez des adolescentes et un trouble alimentaire, et l’effet de médiation de la sensibilité au rejet. Ces résultats suggèrent qu’il faudrait dépister les troubles alimentaires dans les échantillons souffrant de TPL, et que des interventions ciblant la sensibilité au rejet pourraient être d’une utilité clinique,

Mots clés: trouble de la personnalité limite, adolescence, trouble alimentaire, abandon, sensibilité au rejet

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is marked by instability in the core symptom domains of impulsivity and negative affect as well as associated dysfunctional interpersonal relationships (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Historically, the diagnosis of BPD had been restricted to adults. However, in the recent decade there has been a surge in research supporting the diagnosis of BPD in adolescents due to changes in diagnostic criteria and awareness of the disorder (Fossati, 2015). The literature suggests that BPD in adolescents and adults is similar in terms of symptomatology, outcomes, and treatment success (Kaess, Brunner & Chanen, 2014).

Of the nine symptoms of BPD, fear of real or imagined abandonment has been proposed as a core feature of the disorder that contributes to many of the observable symptoms and subjectively experienced cognitions and emotions in affected individuals (Zeichner, 2013). This fear of being abandoned or rejected by others relates to the social psychology concept of rejection sensitivity. Rejection sensitivity is defined as “the cognitive affective disposition that influences expectations, perceptions and behaviour within the context of social rejection” (Downey & Feldman, 1996). Although the theoretical model of rejection sensitivity encompasses the etiology, nature and outcomes of social rejection, there is great interchangeability in the usage of the term (Leary, 2005) to describe any form of negative social evaluation, including fear of abandonment, which was posited as the “ultimate form of rejection” (Stafford, 2007). The model of rejection sensitivity specifically suggests that anxious expectation of rejection or abandonment is the cognitive-affective mediator that links situational perceptions to the behavioural manifestations that influence interpersonal relationships (Downey & Feldman, 1996). Thus, people high in rejection sensitivity are characterized by high levels of anxiety and fear of abandonment, a construct that has become a defining feature of BPD specifically. Although fear of abandonment, typically triggered by rejection, is common throughout the lifespan, the impact of its experience is greatest during childhood or adolescence (Feldman & Downey, 1994).

Rejection Sensitivity in BPD

Borderline Personality Disorder has been both empirically and theoretically linked with the construct of rejection sensitivity (Lakatos, 2012). Rejection sensitivity, which encompasses the concept of fear of abandonment (Downey & Feldman, 1996), is the persistent perception of rejection or assuming intentional hurt by others even if the behaviour is ambiguous. This construct exists on a continuum with some individuals overreacting to rejection cues while others do not (Staebler et al., 2011). High rejection sensitivity leads to a misinterpretation of relational conversation, such as the inability of a colleague to attend an appointment as excluding and neglectful, despite the companion’s intentions.

Many adult studies have examined rejection sensitivity in relation to various psychopathological conditions, especially with regards to BPD. In the recent literature, Staebler and colleagues (2011) reported that individuals with BPD had significantly higher feelings of rejection sensitivity when compared to persons with mood disorders, anxiety disorders, avoidant personality disorder, and healthy controls. This finding has also been replicated in studies by Berenson et al. (Berenson, Downey, Rafaeli, Coifman & Paquin, 2011) and Domsalla et al. (2014) in which rejection sensitivity was higher in those with BPD than any other psychiatric disorder. Impulsive actions such as non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and substance use, common to individuals with BPD, may also be mediated by social rejection sensitivity (Twenge, Catanese & Baumeister, 2002). Specific to this point, these authors noted that the experience of social rejection appeared to increase feelings of emptiness, suicidality, and dissociation, all of which can serve as emotional triggers for NSSI (Glenn and Klonsky, 2013). Further evidence that rejection sensitivity and BPD are etiologically linked are the presence of shared risk factors such as neglectful family environments and insecure attachment style (Zanarini, 2000; Fonagy, Target, Gergely, Allen, & Bateman, 2003).

BPD and Disordered Eating

Studies have shown that disordered eating is found in adults with BPD, whether or not they are diagnosed with a co-morbid eating disorder (Marino & Zanarini, 2001). Disordered eating is defined as abnormal eating behaviour that do not meet the threshold for an eating disorder diagnosis (Tabler & Geist, 2016), but can also be present in individuals with eating disorders. These behaviour include binge eating, dieting, skipping meals regularly, and self-induced vomiting, among others. Although disordered eating behaviour have been traditionally used to define eating disorders, some researchers argue that these behaviour are clinically relevant on their own and common in adolescent girls (Aimé, Craig, Papler, Jiang, & Connolly, 2008; Lee & Vaillancourt, 2018; Menzel et al., 2010; Tabler & Geist, 2016). For example, although eating disorders affect less than 2% of the population, a study by Croll and colleagues (Croll, Neumark-Sztainer, Story, & Ireland, 2002) showed that approximately 50% of adolescent girls engaged in at least one disordered eating behaviour. Neumark-Sztainer and colleagues also demonstrated in a 10-year longitudinal study that disordered eating in adolescence, independent of eating disorder diagnosis, had long-lasting impacts on overall well-being and tended to persist even into young adulthood (Neumark-Sztainer, Wall, Larson, Eisenberg, & Loth, 2011; Neumark-Sztainer, Wall, Story, & Standish, 2012).

Disordered eating can be classified into categories of behaviour such as chronic restriction of food as well as compulsive/binge eating with or without purging. BPD is associated with both types of behaviour, and particularly with impulsive eating pathology such as binge eating and purging. In fact, in a review of nine empirical studies on personality pathology associated with eating disorders in adult samples, BPD was the most common comorbid personality disorder reported in those with eating pathology with an average prevalence rate of approximately 25% and 28% in inpatients with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, respectively (Sansone, Levitt & Sansone, 2004; Sansone & Sansone, 2013).

Does rejection sensitivity link BPD and disordered eating?

Studies have shown that a causal and maintaining feature of disordered eating behaviour is fear of negative social evaluation which is directly related to rejection sensitivity (Rieger et al., 2010). Patients with disordered eating also endorse significantly more maladaptive relationships than controls, similar to those with BPD (De Paoli, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, Halliwell, Puccio, & Krug, 2017). Adults with high rejection sensitivity have a bias towards processing angry faces, a trait seen in both those with disordered eating (Pringle, Harmer & Cooper, 2010) as well as BPD (Kaiser, Jacob, Domes, & Arntz, 2016) suggesting that similar neural networks underlie rejection sensitivity in persons with BPD or with disordered eating.

Since existing studies demonstrate a significant association between BPD symptoms and rejection sensitivity, we predicted that rejection sensitivity may mediate the relationship between BPD and disordered eating behaviour. In further support of this hypothesis, rejection sensitivity, BPD, and disordered eating are each associated with childhood experiences of rejection and dysfunctional attachment to caregivers (Alexander, 2017; Bungert et al., 2015; De Paoli, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz & Krug, 2017).

Longitudinal studies have shown that personality disorder symptoms first manifest during childhood in the form of childhood emotional and behavioural disturbances (Bernstein, Cohen, Skodol, Bezirganian, & Brook, 1996; Chanen & Kaess, 2012; Stepp et al., 2014). Therefore, symptoms of personality pathology likely precede disordered eating behaviour as the latter are reported to develop in adolescence largely due to the pervasive nature of dieting and body dissatisfaction during this time period (Jones, Bennett, Olmsted, Lawson, & Rodin, 2001; Sansone & Sansone, 2007; Slane, Klump, McGue, & Iacono, 2014; Tyrka, Graber & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). A causal model of this phenomenon would best place BPD symptoms before the onset of disordered eating behaviour, or, in the absence of longitudinal data, BPD symptoms – in general – serve as risk factors for disordered eating.

The specific objective of the present study was to report the prevalence of disordered eating and BPD in a clinical sample of adolescent girls. We predicted that BPD diagnosis and BPD symptoms would be strongly associated with disordered eating behaviour. The second objective was to test whether the relationship between BPD and disordered eating behaviour was accounted for by rejection sensitivity specifically.

Methods

Procedure

This study utilized data collected by the Teenage Girls Emotion Regulation (TiGER) Study which examined the relation between disruptive behaviour and BPD symptoms in a clinical sample of adolescent girls. This study recruited females exclusively due to the original research question being female-specific. All procedures were approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board prior to initiation and both participants and guardians consented to participate. Girls were originally referred to the clinic by family doctors, emergency room physicians or self-referral to a central referral agency. Before commencing the study, it was confirmed by researchers that all girls were able to read at a Grade six (age 12) level using the Slosson Oral Reading Test (Slosson & Nichiolson, 1990).

Participants

Participants were 73 female patients aged 11–18 (M =14.92, SD =1.50) consecutively recruited as they presented for mental health treatment at an outpatient psychiatry clinic in a large metropolitan hospital. A score of > 16 on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D scale; Radloff, 1977) and/or having endorsed suicidal thoughts or self-harm was required in order to participate in the study. Exclusionary criteria included a moderate intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or substance abuse disorder with severity likely to impact ability to participate in the study.

Measures

Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression (CES-D)

Current severity of mood symptoms was assessed using the total score from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression (CES-D scale; Radloff, 1977). This 20-item self-report measure asked youth to rate how often they experienced a variety of depressive symptoms over the week prior to participation in the study. The scale has a range of 0–60 and a cut-off score of 16 or higher indicates increased risk of depression with good sensitivity and specificity and high internal consistency (Lewinsohn, Seeley, Roberts, & Allen, 1997).

Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines – Revised (DIB-R)

The Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines – Revised (DIB-R; Zanarini, Gunderson, Frankenburg, & Chauncey, 1989) was used to determine the prevalence of BPD in our sample. The DIB-R is the most commonly used tool to diagnose BPD and has been validated for use in adolescent samples (Ludolph et al, 1990; Wall, Sharp, Goodman & Zanarini, 2017). It is a semi-structured interview measuring the four domains of BPD: Affect, Cognition, Impulsive Action Patterns and Interpersonal Relationships. The interview includes 97 items assessing thoughts, feelings and behaviour reported by the individual over a two-year period (α=.877). These items determine scores on 24 subsections which are then used to calculate scores across the four domains as well as a total score. A total revised DIB score ranges from 0 to 10 and a score of 7 and above was used as the cut-off to indicate a diagnosis of BPD. This tool has excellent psychometric properties including inter-rater reliability and test-retest reliability (Zanarini, Frankenburg & Vujanovic, 2002).

Borderline Personality Questionnaire (BPQ)

The BPQ was used to quantify the symptoms and severity of BPD based on nine subscales parallel to the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for BPD (impulsivity, abandonment, unstable relationships, self-image, self-injury, emptiness, intense anger, and quasi-psychotic states (Poreh et al., 2006). This measure consisted of 80 true or false questions which can be scored to calculate a total for each of the nine subscales with a higher numerical score indicating higher results on that subscale. The BPQ has been used in many studies and has excellent diagnostic accuracy (0.85), test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.92) and internal consistency (alpha = 0.92; Chanen et al., 2008). For this study, the internal consistency of the total score was .81 and .83 for the abandonment factor.

The Short Screen for Eating Disorders (SSED)

The Short Screen for Eating Disorders (SSED) was used to measure disordered eating using the continuum model of eating disorders (Lee and Vaillancourt, 2018; Miller & Boyle, 2009). This measure is novel as it focuses on eating behaviour and not thoughts which has been shown to increase specificity of the items to pathological eating/eating disorders. The scale has 12 items responded to on a 5-point scale (0=never; 1=a few times last month; 2=once a week; 3=2–4 times every week; 4=almost every day) where higher total scores indicate more severe disordered eating behaviour (0–48). Examples of statements include “How often did you eat in secret?” and “How often did you vomit on purpose after eating?”. The SSED has an internal consistency reliability of .81 and as a screening instrument has exhibited 83–97% sensitivity and specificity in predicting cases vs. non-cases. The internal consistency for the current study was .71.

The Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA)

The Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA; Goodman et al., 2010) was used to measure prevalence of separation anxiety, social phobia, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder in participants. The DAWBA is a computerized interview completed by parents and children to identify youth diagnosis using a multi-informant best estimate procedure. This measure includes both structured and open-ended question format which a computer program can then use to predict the presence or absence of diagnoses based on DSM-IV criteria. A clinician then reviews the results and determines whether to accept or reject computer-based predictions. The DAWBA can successfully discriminate between clinic and community populations (Fleitlich-Bilyk & Goodman, 2004; Goodmen et al., 2000) and there are high levels of agreement between the DAWBA and diagnostic case notes among clinical samples (Kendall’s tau b=0.47–0.70; Goodman et al., 2000).

Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Parent Rating Scale (VADPRS)

The VADPRS is a parent-completed rating scale that was used to assess symptoms of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), and Conduct Disorder (CD) in our sample (Wolraich et al., 2003). This measure includes all 18 of the DSM-IV criteria for ADHD, eight criteria for ODD, 12 criteria for CD as well as seven items that screen for anxiety and depression which were not used in this study. Parents are asked to rate their child’s severity of each behaviour on a 4-point (range 0–3) scale ranging from (“never” to “very often”). A clinically significant symptom is considered present if scores of 2 or 3 are endorsed on that symptom. Diagnosis of ADHD inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive subtype required six symptoms, ADHD-combined type required 12 symptoms, ODD required four ODD symptoms and CD required three or more CD symptoms. This measure has high internal consistency (>0.93) and factor structure based on other accepted measures of ADHD (Wolraich et al., 2003). The reliability across the three scales for this sample was high (ADHD α =.94; ODD α = .90; CD α = .70) with reliability for CD being lower due to only having 3% prevalence in the sample.

Statistical Approach

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 statistical software. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all continuous variables (Table 1). Individuals were categorized as “yes” or “no” for BPD based on a cut-off score of 7 on the revised DIB. A disordered eating score was calculated using a total score of unhealthy eating behavior on the SSED. For the first analysis which addressed hypothesis 1, examining if youth with BPD had significantly more disordered eating behaviour, an independent samples 2-tailed t-test was used to compare differences in average disordered eating behavior between youth with and without a diagnosis of BPD.

Table 1.

Psychiatric disorders in participants (n= 73)

| Disorder | N | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder† | 44 | 60.3 |

| Depression† | 35 | 47.9 |

| Social Phobia† | 32 | 43.8 |

| ODD‡ | 30 | 41.1 |

| ADHD-Inattentive‡ | 24 | 32.9 |

| BPD§ | 18 | 24.7 |

| Separation Anxiety† | 9 | 12.3 |

| ADHD-Hyperactive‡ | 7 | 9.6 |

| PTSD† | 6 | 8.2 |

| ADHD-Combined‡ | 4 | 5.5 |

| OCD† | 2 | 2.7 |

| CD‡ | 2 | 2.7 |

| Number of Diagnoses (Mean) | 2.4 |

Note: Development and Wellbeing Assessment (DAWBA).

Vanderbilt ADHD Parent Rating Scale (VADPRS).

Diagnostic Interview for Borderline (DIB)

Secondly, a hierarchical regression was utilized to explore our hypothesis to determine which facet of BPD (Impulsivity, Affective Instability, Abandonment, Dysfunctional Relationships, Self-Image, Suicide/Self-Mutilation, Emptiness, Intense Anger, and Quasi-Psychotic States) contributed most to disordered eating behavior, measured as the total SSED score. These facets were identified using the sum of particular items from the BPQ. Violations of assumptions of multiple regression analysis were checked to ensure validity of the results. These assumptions include adequacy of sample size, normality, a lack of multicollinearity, non-homoscedasticity, and independence of observations. After verifying the results utilizing a stepwise regression, suicide/self-mutilation was also identified as a factor that contributed significantly to the model. Abandonment was entered first followed by Suicide/Self-Mutilation in this block.

To test our second hypothesis examining if the relationship between BPD and disordered eating behaviour was fully or partially mediated by rejection sensitivity, mediation was tested using Hayes’ PROCESS macro (2013). This is a regression path analysis tool that estimates direct and indirect effects of predictor variables on the outcome variable. All assumptions of this model were satisfied, so data were bootstrapped to 1000 draws to generate confidence intervals. BPD was entered as the predictor variable and disordered eating behavior as the outcome variable with abandonment as the mediator.

Results

Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the sample is shown in Table 1. Approximately 25% of the sample met criteria for BPD (N=18) and most girls had more than one comorbid psychiatric disorder.

Association between disordered eating behaviour and BPD diagnosis

Compared to those without a diagnosis of BPD (Mean score (disordered eating) = 27.1, SD = 3.39, n = 55), individuals with BPD (M = 30.4, SD = 3.68, n = 18) exhibited significantly more disordered eating behaviour; t (72) = 3.61, p < .01, rpb =.393, p < .01.

Association between BPD symptoms and disordered eating behaviour

All nine facets of BPD, except intense anger, were significantly correlated with disordered eating behaviour (Table 2). As its correlation was the highest of all facets, Abandonment was entered first in a regression analysis, explaining 32% of the variance in disordered eating behaviour (F (1, 72) = 33.682, p < .001, MSE = 9.54, β = .565). Suicide/Self-Mutilation contributed to the model, explaining an additional 5% of the variance in disordered eating behaviour (F (2, 71) = 21.121, p < .05, MSE = 8.91, β = .276). Together, both Abandonment and Suicide/Self-Mutilation explained 37% of the variance in disordered eating behaviour. All other variables (Impulsivity, Affective Instability, Dysfunctional Relationships, Self-Image, Emptiness, Intense Anger and Quasi-Psychotic States) did not significantly contribute to the model.

Table 2.

BPQ Subscales Descriptive Statistics and Correlations with Disordered Eating

| M | SD | Disordered Eating | Impulsivity | Affective Instability | Abandonment | Relationships | Self-Image | Suicide/Self-Mutilation | Emptiness | Intense Anger | Quasi-Psychotic States | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disordered | Eating | 27.9 | 3.72 | 1 | .313** | .411** | .565** | .436** | .466** | .499** | .489** | .199 | .332** |

| Impulsivity | 7.52 | 2.66 | 1 | .329** | .335** | .225* | .241* | .428** | .223* | .375** | .363** | ||

| Affective | |||||||||||||

| Instability | 4.80 | 2.98 | 1 | .409** | .381** | .378** | .424** | .476** | .442** | .226* | |||

| Abandonment | 4.75 | 2.47 | 1 | .692** | .547** | .519** | .639** | .386** | .537** | ||||

| Relationships | 5.71 | 2.82 | 1 | .557** | .361** | .616** | .379** | .413** | |||||

| Self-Image | 4.44 | 2.01 | 1 | .405** | .845** | .425** | .307** | ||||||

| Suicide/Self- | Mutilation | 6.38 | 3.17 | 1 | .421** | .155 | .253* | ||||||

| Emptiness | 5.77 | 2.92 | 1 | .508** | .394** | ||||||||

| Intense Anger | 2.68 | 1.96 | 1 | .408** | |||||||||

| Quasi-Psychotic | 2.05 | 1.57 | 1 | ||||||||||

| States |

Note: BPQ = Borderline Personality Questionnaire. Significance at p<.0 5 is denoted by *, p<.01 by **

Abandonment as a mediator of BPD and disordered eating behaviour

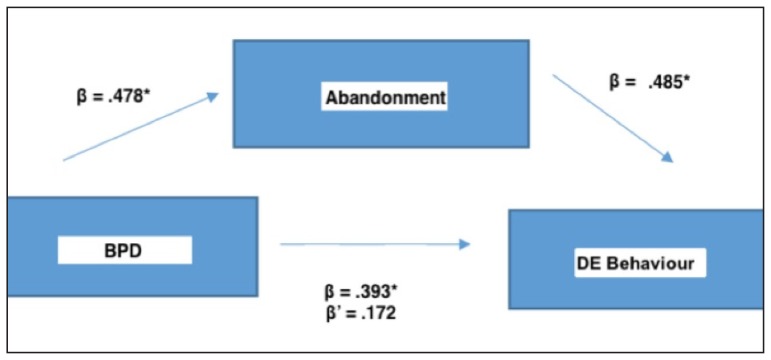

We evaluated whether Abandonment would mediate the relation between BPD symptoms and disordered eating behaviour (Table 3). Regression analysis was used to investigate this hypothesis utilizing the method by Preacher and Hayes (Hayes, 2013). Results indicated that BPD was a significant predictor of disordered eating behaviour (Model 1), R2=.15, F (1, 71) = 13.0, p <.001, β =.39, SE = 0.1091, 95% CI [.1758, .6109]. As well, Abandonment was a significant predictor of disordered eating behaviour, β = .49, SE = .11, 95% CI [.26, .70]. The relation between disordered eating behaviour and BPD became non-significant after including Abandonment as a mediator (Model 2), R2= .34, F (2, 70) = 18.14, p > .05, β = .17, SE = .11, 95% CI [-.04, .39]. After bootstrapping to 1000 draws, the indirect effect of BPD to disordered eating behaviour through Abandonment was β = .22, SE =0.64, 95% CI [.11, .34]. Since βc’ = .17 < βc =.39 and βc’ is no longer significant, Abandonment is a full mediator of this relation and the hypothesis is supported (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Regression analysis of BPD and Abandonment as predictors of disordered eating behaviour

| B | R2 | F | T | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: | ||||

| BPD | .393** | .155 | 13.0** | 3.61** |

| Model 2: | ||||

| BPD and Abandonment | .341 | 18.1*** | ||

| 1. BPD | .172 | 1.58 | ||

| 2. Abandonment | .485*** | 4.45*** | ||

BPD = Borderline Personality Disorder. Significance at p<.0 5 is denoted by *, p<.01 by ** and p<.001 by ***

Model 1 represents BPD entered as a predictor of disordered eating behaviour.

Model 2 demonstrates the mediation effect of abandonment on the relationship between BPD and disordered eating behaviour.

Figure 1.

Please provide a title

Discussion

This study was the first to investigate the relationship between disordered eating behaviour and BPD symptoms in a clinical sample of adolescent girls who did not have eating disorders. We found that girls with BPD had significantly more disordered eating behaviour than those without a BPD diagnosis and that disordered eating behaviour and BPD symptoms were strongly correlated. Other studies have examined this relationship in youth with eating disorders, in samples where disordered eating as well as BPD symptoms would be prevalent. Selby, Ward & Joiner (2010) identified a relationship between BPD and disordered eating in adults and found that BPD symptoms predicted higher levels of rejection sensitivity, leading to emotion dysregulation and then subsequent dysregulated eating behaviour.

This study replicated previous findings that both BPD and disordered eating were associated with rejection sensitivity. Staebler and colleagues (2011) compared levels of rejection sensitivity in patients with BPD compared to other clinical disorders and found that BPD patients had the highest scores on measures of rejection sensitivity, even when compared to patients with social anxiety disorder. Other research has also shown that even those with remitted BPD had higher levels of rejection sensitivity than healthy controls, indicating that this factor is persistent and requires increased attention during treatment (Bungert et al., 2015). With regards to disordered eating, De Paoli and colleagues found that rejection sensitivity mediated the relationship between disordered eating and insecure attachment, which is also prevalent in BPD (2017). Further, Cardi et al. (Cardi, Matteo, Corfield, & Treasure, 2013) found that lifetime eating disorder patients showed an attentional bias to rejecting faces compared to healthy controls, suggesting these patients may have elevated rejection sensitivity.

We found that rejection sensitivity accounted for 32% of the relationship between BPD and disordered eating in adolescents. Studies of adults have identified similar findings. De Paoli and colleagues (2017) found that rejection sensitivity mediated the relationship between disordered eating and insecure attachment, which is also prevalent in BPD. Other studies have found that emotional cascades (intense rumination and negative affect) mediated the relationship between BPD and binge-eating, suggesting that other dysfunctional cognitions may also contribute to this relationship (Selby, Anestis, Bender, & Joiner, 2009). Selby, Ward & Joiner (2010) posited that adults with BPD may partake in disordered eating behaviour as an emotion regulation strategy to cope with feelings of rejection. This proposed mechanism may also apply to adolescents with BPD or without BPD and requires further investigation in longitudinal studies.

Clinical Implications

Disordered eating is highly prevalent in adolescents and is associated with long-lasting impacts on well-being such as depression, weight gain and other health concerns (Neumark-Sztainer et al. 2011, 2012; Stephen, Rose, Kenney, Rosselli-Navarra, & Weissman, 2014) and can be easily missed due to its sub-threshold nature. Consideration should be given to screening for disordered eating in youth, particularly those who present with BPD symptoms.

Given our findings about the relationship between BPD and disordered eating, it is possible that disordered eating may be used by adolescents with BPD to regulate their emotions in situations where rejection sensitivity is exacerbated. Therapies targeting emotion regulation skill development such as Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) may be helpful to treat disordered eating in these populations (Linehan, 1993). A randomized controlled trial found that DBT in adults was beneficial in reducing binge eating and was found to have a much lower dropout than other therapies (Safer & Jo, 2010). Further, given the finding of rejection sensitivity as a mediator of disordered eating, targeting rejection sensitivity as a possible process variable with the therapy client by challenging thoughts of perceived abandonment may help reduce disordered eating. In Linehan’s DBT manual, the interpersonal effectiveness module focuses on teaching clients social skills to help stabilize difficult relationship dynamics (May, Richardi & Barth, 2016). Rejection sensitivity has been shown to be a persistent issue even in remitted patients, indicating that this factor in treatment may be lacking (Bungert et al., 2015) and is often not directly addressed by DBT (Biskin, 2015). Incorporating a greater focus on rejection sensitivity specifically by educating clients about this concept and teaching methods to navigate situations in which they may be rejection sensitive may lead to better treatment success.

Limitations and Future Directions

The findings of our study should be considered in the context of its limitations. Our findings cannot be generalized to the studies examining youth with eating disorders. No participants in our study were being treated clinically for an eating disorder, although as our data show, there was a range of disordered eating behaviour. Second, the sample consisted exclusively of girls. Studying the relationship in boys is important as adolescent males and females have different rates of psychopathology (Zahn-Waxler, Shirtcliff & Marceau, 2008), including eating disorders (Raevuori, Keski-Rahkonen & Hoek, 2014) and likely also disordered eating (Kinasz, Accurso, Kass, & Le Grange, 2016). In fact, in a five-year longitudinal study by Lee & Vaillancourt, adolescent girls consistently reported higher disordered eating scores compared to boys except during one time point (Lee & Vaillancourt, 2018). Third, the sample was cross-sectional which does not allow inference to causality. Further research should examine this relationship in a longitudinal sample to observe if this relationship is consistent over time.

Future studies may also benefit from examining the type of rejection sensitivity (eg. Appearance-Based rejection sensitivity; De Paoli et al., 2017) that most contributes to disordered eating behaviour in BPD patients to allow for targeting of more specific treatment. Appearance-based rejection sensitivity differs from personal rejection sensitivity, which assesses sensitivity to rejection in general, as it is characterized by anxious concerns regarding expectations about being rejected based on physical attractiveness specifically (Park, 2007). This form of rejection sensitivity has been found to predict disordered eating in community samples (Park, 2007), increase interest in cosmetic surgery in college students (Park, Calogero, Harwin & DiRaddo, 2009) and was associated with more severe body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) and depressive symptoms in BDD patients (Kelly, Didie & Phillips, 2014). This form of rejection sensitivity was also found to be a mediator of the relationship between social anxiety symptoms and disordered eating cognitions and behaviour in a community sample of males and females (Linardon, Braithwaite, Cousins, & Brennan, 2017). Despite these findings, there are no known studies that have investigated appearance-based rejection sensitivity in those with BPD, or in eating disorder samples in general.

In conclusion, we found that disordered eating behaviour are highly prevalent in adolescent girls with BPD and that the relationship between BPD and disordered eating is mediated by rejection sensitivity. Our results contribute to an increasing body of literature that examines the etiology of BPD in adolescents and its relationship to other behaviour and conditions.

Acknowledgements / Conflicts of Interest

Funding for this study was provided by Hamilton Health Sciences Foundation.

References

- Aimé A, Craig WM, Pepler D, Jiang D, Connolly J. Developmental pathways of eating problems in adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41(8):686–696. doi: 10.1002/eat.20561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander Attachment anxiety is associated with a fear of becoming fat, which is mediated by binge eating. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3034. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition. 2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berenson KR, Downey G, Rafaeli E, Coifman KG, Paquin NL. The rejection–rage contingency in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120(3):681–690. doi: 10.1037/a0023335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Cohen P, Skodol A, Bezirganian S, Brook JS. Childhood antecedents of adolescent personality disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153(7):907–913. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.7.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biskin RS. The lifetime course of borderline personality disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(7):303–8. doi: 10.1177/070674371506000702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bungert M, Koppe G, Niedtfeld I, Vollstädt-Klein S, Schmahl C, Lis S, Bohus M. Pain Processing after Social Exclusion and Its Relation to Rejection Sensitivity in Borderline Personality Disorder. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0133693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bungert M, Liebke L, Thome J, Haeussler K, Bohus M, Lis S. Rejection sensitivity and symptom severity in patients with borderline personality disorder: effects of childhood maltreatment and self-esteem. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation. 2015;2(1) doi: 10.1186/s40479-015-0025-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardi V, Matteo RD, Corfield F, Treasure J. Social reward and rejection sensitivity in eating disorders: An investigation of attentional bias and early experiences. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 2013;14(8):622–633. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2012.665479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanen AM, Jovev M, Djaja D, McDougall E, Yuen HP, Rawlings D, Jackson HJ. Screening for Borderline Personality Disorder in Outpatient Youth. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2008;22(4):353–364. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.4.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanen AM, Kaess M. Developmental Pathways to Borderline Personality Disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2012;14(1):45–53. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0242-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croll J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Ireland M. Prevalence and risk and protective factors related to disordered eating behaviors among adolescents: relationship to gender and ethnicity. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2002;31(2):166–175. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00368-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paoli T, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Halliwell E, Puccio F, Krug I. Social Rank and Rejection Sensitivity as Mediators of the Relationship between Insecure Attachment and Disordered Eating: Social Rank and Rejection Sensitivity. European Eating Disorders Review. 2017;25(6):469–478. doi: 10.1002/erv.2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paoli T, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Krug I. Insecure attachment and maladaptive schema in disordered eating: The mediating role of rejection sensitivity. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2017;24(6):1273–1284. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domsalla M, Koppe G, Niedtfeld I, Vollstädt-Klein S, Schmahl C, Bohus M, Lis S. Cerebral processing of social rejection in patients with borderline personality disorder. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2014;9(11):1789–1797. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Feldman SI. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70(6):1327–1343. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman S, Downey G. Rejection sensitivity as a mediator of the impact of childhood exposure to family violence on adult attachment behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6(01):231–247. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400005976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleitlich-Bilyk B, Goodman R. Prevalence of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Disorders in Southeast Brazil. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(6):727–734. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000120021.14101.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P, Target M, Gergely G, Allen JG, Bateman AW. The Developmental Roots of Borderline Personality Disorder in Early Attachment Relationships: A Theory and Some Evidence. Psychoanalytic Inquiry. 2003;23(3):412–459. doi: 10.1080/07351692309349042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fossati A. Diagnosing Borderline Personality Disorder During Adolescence: A Review of the Published Literature. Scandinavian Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychology. 2015;3(1):5–21. doi: 10.21307/sjcapp-2015-002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CR, Klonsky ED. Nonsuicidal Self-Injury Disorder: An Empirical Investigation in Adolescent Psychiatric Patients. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42(4):496–507. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.794699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R, Ford T, Richards H, Gatward R, Meltzer H. The Development and Well-Being Assessment: Description and Initial Validation of an Integrated Assessment of Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41(5):645–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2000.tb02345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jones JM, Bennett S, Olmsted MP, Lawson ML, Rodin G. Disordered eating attitudes and behaviour in teenaged girls: a school-based study. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de l’Association Medicale Canadienne. 2001;165(5):547–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaess M, Brunner R, Chanen A. Borderline Personality Disorder in Adolescence. PEDIATRICS. 2014;134(4):782–793. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser D, Jacob GA, Domes G, Arntz A. Attentional Bias for Emotional Stimuli in Borderline Personality Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. Psychopathology. 2016;49(6):383–396. doi: 10.1159/000448624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MM, Didie ER, Phillips KA. Personal and appearance-based rejection sensitivity in body dysmorphic disorder. Body Image. 2014;11(3):260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinasz K, Accurso EC, Kass AE, Le Grange D. Does Sex Matter in the Clinical Presentation of Eating Disorders in Youth? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2016;58(4):410–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos S. Would Exposure Therapy be Effective for Reducing Rejection Sensitivity in Borderline Personality Disorder? Graduate Student Journal of Psychology. 2012;12 [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR. Sociometer theory and the pursuit of relational value: Getting to the root of self-esteem. European Review of Social Psychology. 2005;16(1):75–111. doi: 10.1080/10463280540000007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KS, Vaillancourt T. Longitudinal Associations Among Bullying by Peers, Disordered Eating Behavior, and Symptoms of Depression During Adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(6):605. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, Allen NB. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychology and Aging. 1997;12(2):277–287. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardon J, Braithwaite R, Cousins R, Brennan L. Appearance-based rejection sensitivity as a mediator of the relationship between symptoms of social anxiety and disordered eating cognitions and behaviors. Eating Behaviors. 2017;27:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ludolph PS, Westen D, Misle B, Jackson A, Wixom J, Wiss FC. The borderline diagnosis in adolescents: symptoms and developmental history. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147(4):470–476. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.4.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino MF, Zanarini MC. Relationship between EDNOS and its subtypes and borderline personality disorder. The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;29(3):349–353. doi: 10.1002/eat.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May JM, Richardi TM, Barth KS. Dialectical behavior therapy as treatment for borderline personality disorder. Mental Health Clinician. 2016;6(2):62–67. doi: 10.9740/mhc.2016.03.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzel JE, Schaefer LM, Burke NL, Mayhew LL, Brannick MT, Thompson JK. Appearance-related teasing, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating: A meta-analysis. Body Image. 2010;7(4):261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JL, Boyle M. Short Screen for Eating Disorders (SSED) Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: McMaster University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Larson NI, Eisenberg ME, Loth K. Dieting and Disordered Eating Behaviors from Adolescence to Young Adulthood: Findings from a 10-Year Longitudinal Study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2011;111(7):1004–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Story M, Standish AR. Dieting and Unhealthy Weight Control Behaviors During Adolescence: Associations With 10-Year Changes in Body Mass Index. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50(1):80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park LE. Appearance-Based Rejection Sensitivity: Implications for Mental and Physical Health, Affect, and Motivation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33(4):490–504. doi: 10.1177/0146167206296301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park LE, Calogero RM, Harwin MJ, DiRaddo AM. Predicting interest in cosmetic surgery: Interactive effects of appearance-based rejection sensitivity and negative appearance comments. Body Image. 2009;6(3):186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poreh AM, Rawlings D, Claridge G, Freeman JL, Faulkner C, Shelton C. The BPQ: A Scale for the Assessment of Borderline Personality Based on DSM-IV Criteria. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2006;20(3):247–260. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2006.20.3.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle A, Harmer CJ, Cooper MJ. Biases in emotional processing are associated with vulnerability to eating disorders over time. Eat Behav. 2010;12:56–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raevuori A, Keski-Rahkonen A, Hoek HW. A review of eating disorders in males. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27:426–30. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger E, Van Buren DJ, Bishop M, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Welch R, Wilfley DE. An eating disorder-specific model of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT-ED): Causal pathways and treatment implications. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(4):400–410. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safer DL, Jo B. Outcome from a Randomized Controlled Trial of Group Therapy for Binge Eating Disorder: Comparing Dialectical Behavior Therapy Adapted for Binge Eating to an Active Comparison Group Therapy. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41(1):106–120. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansone RA, Levitt JL, Sansone LA. The Prevalence of Personality Disorders Among Those with Eating Disorders. Eating Disorders. 2004;13(1):7–21. doi: 10.1080/10640260590893593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Childhood Trauma, Borderline Personality, and Eating Disorders: A Developmental Cascade*. Eating Disorders. 2007;15(4):333–346. doi: 10.1080/10640260701454345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Responses of mental health clinicians to patients with borderline personality disorder. Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience. 2013;10(5–6):39–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, Anestis MD, Bender TW, Joiner TE. An exploration of the emotional cascade model in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118(2):375–387. doi: 10.1037/a0015711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, Ward AC, Joiner TE. Dysregulated eating behaviors in borderline personality disorder: Are rejection sensitivity and emotion dysregulation linking mechanisms? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2010;43(7):667–670. doi: 10.1002/eat.20761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slane JD, Klump KL, McGue M, Iacono WG. Developmental trajectories of disordered eating from early adolescence to young adulthood: A longitudinal study: Developmental trajectories of disordered eating. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2014;47(7):793–801. doi: 10.1002/eat.22329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slosson RL, Nicholson CL. Slosson Oral Reading Test, Revised. East Aurora, NY: Slosson Educational Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Staebler K, Helbing E, Rosenbach C, Renneberg B. Rejection sensitivity and borderline personality disorder. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2011;18(4):275–283. doi: 10.1002/cpp.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford L. INTERPERSONAL REJECTION SENSITIVITY: TOWARD EXPLORATION OF A CONSTRUCT. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2007;28(4):359–372. doi: 10.1080/01612840701244250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephen EM, Rose JS, Kenney L, Rosselli-Navarra F, Weissman R. Prevalence and correlates of unhealthy weight control behaviors: findings from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Journal of Eating Disorders. 2014;2(1):16. doi: 10.1186/2050-2974-2-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepp SD, Whalen DJ, Scott LN, Zalewski M, Loeber R, Hipwell AE. Reciprocal effects of parenting and borderline personality disorder symptoms in adolescent girls. Development and Psychopathology. 2014;26(02):361–378. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413001041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabler J, Geist C. Young Women with Eating Disorders or Disordered Eating Behaviors: Delinquency, Risky Sexual Behaviors, and Number of Children in Early Adulthood. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World. 2016;2 doi: 10.1177/2378023116648706. 237802311664870. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Catanese KR, Baumeister RF. Social exclusion causes self-defeating behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83(3):606–615. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.3.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J. The Development of Disordered Eating. In: Sameroff AJ, Lewis M, Miller SM, editors. Handbook of Developmental Psychopathology. Boston, MA: Springer US; 2000. pp. 607–624. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wall K, Sharp C, Ahmed Y, Goodman M, Zanarini MC. Parent-adolescent concordance on the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R) and the Childhood Interview for Borderline Personality Disorder (CI-BPD): Adolescent-parent DIB-R and CI-BPD concordance. Personality and Mental Health. 2017;11(3):179–188. doi: 10.1002/pmh.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolraich ML, Lambert W, Doffing MA, Bickman L, Simmons T, Worley K. Psychometric properties of the Vanderbilt ADHD diagnostic parent rating scale in a referred population. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2003;28(8):559–567. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Shirtcliff EA, Marceau K. Disorders of childhood and adolescence: Gender and psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:275–303. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC. Childhood experiences associated with the development of borderline personality disorder. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2000;23(1):89–101. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini Mary C, Frankenburg FR, Vujanovic AA. Inter-rater and test-retest reliability of the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2002;16(3):270–276. doi: 10.1521/pedi.16.3.270.22538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL. The Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines: Discriminating BPD from other Axis II Disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1989;3(1):10–18. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1989.3.1.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeichner S. Borderline Personality Disorder: Implications in Family and Pediatric Practice. Journal of Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2013;03(04) doi: 10.4172/2161-0487.1000122xe. [DOI] [Google Scholar]