Abstract

In 2012, a European initiative called Single Hub and Access point for paediatric Rheumatology in Europe (SHARE) was launched to optimise and disseminate diagnostic and management regimens in Europe for children and young adults with rheumatic diseases. Juvenile localised scleroderma (JLS) is a rare disease within the group of paediatric rheumatic diseases (PRD) and can lead to significant morbidity. Evidence-based guidelines are sparse and management is mostly based on physicians’ experience. This study aims to provide recommendations for assessment and treatment of JLS. Recommendations were developed by an evidence-informed consensus process using the European League Against Rheumatism standard operating procedures. A committee was formed, mainly from Europe, and consisted of 15 experienced paediatric rheumatologists and two young fellows. Recommendations derived from a validated systematic literature review were evaluated by an online survey and subsequently discussed at two consensus meetings using a nominal group technique. Recommendations were accepted if ≥80% agreement was reached. In total, 1 overarching principle, 10 recommendations on assessment and 6 recommendations on therapy were accepted with ≥80% agreement among experts. Topics covered include assessment of skin and extracutaneous involvement and suggested treatment pathways. The SHARE initiative aims to identify best practices for treatment of patients suffering from PRDs. Within this remit, recommendations for the assessment and treatment of JLS have been formulated by an evidence-informed consensus process to produce a standard of care for patients with JLS throughout Europe.

Keywords: methotrexate, systemic sclerosis, DMARDs (biologic)

Introduction

In 2012, a European project called Single Hub and Access point for paediatric Rheumatology in Europe (SHARE) was launched to optimise and disseminate diagnostic and management regimens in Europe for children and young adults with rheumatic diseases.1 As currently no international or European consensus exists with regard to the assessment and treatment of juvenile rheumatic diseases, defining clear guidelines is one of the most important aims of the SHARE initiative. In this paper, we focus on juvenile localised scleroderma (JLS) consensus-based recommendations.

Methods

An international committee of 15 experts in paediatric rheumatology was established to develop consensus-based recommendations for JLS.2 European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) standard operating procedures for developing best practice were used.3 Ten experts were part of the SHARE consortium; five other experts were asked to take part to the project due to their consolidate clinical experience in the management of JLS.

Systematic literature search

The electronic databases PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase and Cochrane were searched in August 2013 and subsequently in January 2015. All synonyms of JLS were searched in MeSH/Emtree terms, title and abstract. Reference tracking was performed in all included studies (full search strategy in online supplementary figure S1). Fellows (RC, FS) and experts (FZ, IF) selected the relevant papers for validity assessment (inclusion and exclusion criteria shown in online supplementary figure S1): 53 out of 1550 papers were eventually selected. All full-text scored papers are listed in the online supplementary list 1.

annrheumdis-2018-214697supp001.pdf (170KB, pdf)

annrheumdis-2018-214697supp002.htm (69.9KB, htm)

Validity assessment

Every relevant paper dealing with ‘diagnosis’, ‘assessment’ and ‘therapy’ studies has been independently assessed for methodological quality by two experts, who extracted data using a predefined scoring system.4 Disagreements were resolved by the opinion of a third expert. Adapted classification tables for assessment and therapeutic studies were used to determine the level of evidence and strength of each recommendation.5

Recommendation development

As part of the EULAR standard operating procedure,3 experts assessed validity and level of evidence and described the main results and conclusions of each paper. This information was examined by two experts (FZ, IF) and used to formulate 18 provisional recommendations. These drafted recommendations were at first presented to the expert committee in an online survey (100% response rate) and subsequently revised accordingly to responses. The derived recommendations were then presented to the expert committee and discussed using a nominal group technique in two face-to-face meetings on March 2014 in Genova (Italy) and on March 2015 in Barcelona (Spain). At both meeting, a non-voting expert (SJV) facilitated the process. Recommendations were accepted when ≥80% of the experts agreed.

Results

The literature search yielded 1550 papers; after the application of inclusion/exclusion criteria, title/abstract and full-text screening, 53 papers (26 for assessment and 27 for treatment) were selected and sent to the expert committee for validity assessment. Following a consensus-based methodology, the scleroderma working group of SHARE formulated 22 recommendations for the management of JLS. In total, 1 overarching principle, 10 recommendations on assessment and 6 on therapy were accepted with ≥80% agreement among the experts. Topics include assessment of skin, extracutaneous involvement and treatment suggestions at disease onset and in refractory disease.

We briefly describe the recommendations with corresponding supporting literature. Tables 1 and 2 summarise the recommendations for JLS, their levels of evidence, recommendation strength and percentage of agreement between experts. Of note, two recommendations derive from randomised controlled trials (level of evidence 1b, strength of evidence A), while three derive from expert opinions (level of evidence 4, strength of evidence D).

Table 1.

Recommendations regarding diagnosis and assessment

| L | S | Agreement (%) |

||

|

|

Overarching principle

All children with suspected localised scleroderma should be referred to a specialised paediatric rheumatology centre. |

4 | D | 100 |

| 1 | LoSSI, which is part of LoSCAT, is a good clinical instrument to assess activity and severity in JLS lesions and is highly recommended in clinical practice. | 3 | C | 90 |

| 2 | LoSDI, which is part of LoSCAT, is a good clinical instrument to assess damage in JLS and is highly recommended in clinical practice. | 3 | C | 90 |

| 3 | Infrared thermography can be used to assess activity of the lesions in JLS, but skin atrophy can give false-positive results. | 4 | D | 90 |

| 4 | A specialised US imaging, using standardised assessment and colour Doppler, may be a useful tool for assessing disease activity, extent of JLS and response to treatment. | 4 | D | 100 |

| 5 | All patients with JLS at diagnosis and during follow-up should be carefully evaluated with a complete joint examination, including the temporomandibular joint. | 2a | C | 100 |

| 6 | MRI can be considered a useful tool to assess musculoskeletal involvement in JLS, especially when the lesion crosses the joint. | 3 | C | 100 |

| 7 | It is highly recommended that all patients with JLS involving face and head, with or without signs of neurological involvement, have an MRI of the head at the time of the diagnosis. | 3 | C | 90 |

| 8 | All patients with JLS involving face and head should undergo an orthodontic and maxillofacial evaluation at diagnosis and during follow-up. | 2b | B | 90 |

| 9 | Ophthalmological assessment, including screening for uveitis, is recommended at diagnosis for every patient with JLS, especially in those with skin lesions on the face and scalp. | 2a | C | 100 |

| 10 | Ophthalmological follow-up, including screening for uveitis, should be considered for every patient with JLS, especially in those with skin lesions on the face and scalp. | 3 | C | 100 |

JLS, juvenile localised scleroderma; L, level of evidence; LoSCAT, Localized Scleroderma Cutaneous Assessment Tool; LoSDI, Localized Scleroderma Skin Damage Index; LoSSI, Localized Scleroderma Skin Severity Index; S, strength of recommendation; US, ultrasound.

Table 2.

Recommendations regarding treatment

| L | S | Agreement (%) |

|

| Systemic corticosteroids may be useful in the active inflammatory phase of JLS. At the same time as starting systemic corticosteroids, MTX or an alternative DMARD should be started. | 2b | C | 100 |

| All patients with active, potentially disfiguring or disabling forms of JLS should be treated with oral or subcutaneous methotrexate at 15 mg/m²/week. | 1b | A | 100 |

| If acceptable clinical improvement is achieved, methotrexate should be maintained for at least 12 months before tapering. | 3 | C | 100 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil may be used to treat severe JLS or MTX-refractory or MTX-intolerant patients. | 2a | B | 100 |

| Medium-dose UVA1 phototherapy may be used to improve skin softness in isolated (circumscribed) morphoea lesions. | 1b | A | 100 |

| Topical imiquimod may be used to decrease skin thickening of circumscribed morphoea. | 3 | C | 100 |

DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; JLS, juvenile localised scleroderma; L, level of evidence; MTX, methotrexate; S, strength of recommendation; UVA1, ultraviolet A1.

Overarching principle

JLS includes a group of disorders whose manifestations are confined to the skin and subdermal tissues and, with rare exceptions, do not affect internal organs. The most widely used classification includes five subtypes: circumscribed morphoea, linear scleroderma, generalised morphoea, pansclerotic morphoea, and the mixed subtype where a combination of two or more of the previous subtypes is present.2 It is a rare condition in children as the incidence is 3.4 cases per million children per year, the vast majority represented by the linear subtype.6 The female to male ratio of JLS is 2.4:1, the mean age at onset is approximately 7.3 years,7 although the disease can start as early as at birth.8 The severity of the disease varies widely from isolated plaques to generalised morphoea, and to extensive linear lesions involving limbs, trunk and/or the face and head.9

Given the rarity of the disease, the expert group agreed that patients with suspected JLS should be referred to a specialised paediatric rheumatology centre for clinical assessment and treatment (table 1).

Assessment of skin lesions

The assessment of disease activity is crucial in patients with JLS. At the time of diagnosis and during follow-up, it is fundamental to determine whether a lesion is active in order to establish an appropriate treatment regimen. Indeed, quantifying the activity of specific lesions is important in order to evaluate the response to therapy. As for disease activity and severity, the experts agreed on using both multiparametric scoring systems and instrumental techniques (table 1).

LoSCAT (Localized Scleroderma Cutaneous Assessment Tool) is a scoring system that includes a Skin Severity Index (LoSSI) and a Skin Damage Index (LoSDI).10 11 LoSSI is a validated clinical instrument that allows to assess activity and severity of JLS lesions. Indeed, it correlates well with disease activity evaluated by clinicians.12 LoSSI includes four domains (body surface area involvement, degree of erythema, skin thickness and appearance of new lesion or old lesion extension), each one graded from 0 to 3, in 18 anatomic sites.10 LoSDI assesses damage by a similar scoring system. It includes three domains: skin atrophy, subcutaneous tissue loss and hypo-hyperpigmentation.11 Although this method does not evaluate the real size of the lesions, it can be performed by physicians in daily practice without the need for special equipment.

Infrared thermography (IT) is a non-invasive technique that detects infrared radiation and provides an image of the temperature distribution across the body surface.13 IT has been shown to be of value in the detection of active lesions with high sensitivity (92%) but moderate specificity (68%).13 False-positive results are related to the fact that old lesions lead to marked atrophy of skin, subcutaneous fat and muscle, with increased heat conduction from deeper tissues.

High-frequency ultrasound can detect several abnormalities such as increased blood flow related to inflammation as well as increased echogenicity due to fibrosis and loss of subcutaneous fat.14 15 The main limits of this tool are its operator dependency and the lack of standardisation.

Assessment of extracutaneous involvement

Although cutaneous and subcutaneous involvement is prominent, almost 20% of patients with JLS present extracutaneous manifestations16 which are more frequent in patients with linear scleroderma and consist essentially of arthritis, neurological findings or other autoimmune conditions. Based on published data and clinical experience, the experts approved six recommendations regarding the assessment and monitoring of the extracutaneous manifestations of JLS.

Articular involvement is the most frequent extracutaneous feature being present in up to 19% of patients.16 It can manifest with limited range of joint motion from contractures and/or arthritis.

Articular involvement is more common in children with the linear subtype, but it can be present in any subtype of JLS.16 Therefore, all patients with JLS should be evaluated with a comprehensive joint examination at diagnosis and during follow-up. Joint symptoms are more common in patients with linear scleroderma and the affected joint does not always correlate with the site of the cutaneous lesion. Children with JLS who develop arthritis often have positive rheumatoid factor, and sometimes an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate.7 A few studies, conducted mainly in adults,17 18 reported a positive correlation between MRI and clinical findings of arthritis, especially during treatment. In addition to the literature evidence, the expert panel reported a positive experience in using this non-invasive tool to assess musculoskeletal involvement in JLS.

Central nervous system (CNS) involvement, although rare, has been reported in children with JLS, especially in those with linear scleroderma of the face and scalp.19 The most frequent signs and symptoms are seizures and headache, although behavioural changes and learning disabilities have been also described.16 20 Abnormalities on MRI, such as calcifications, white matter changes and vascular malformations or vasculitis, have also been reported.21 Considering that most of these changes have been reported in the linear scleroderma of the face/head, it is mandatory to perform an MRI of the head in every patient with facial/scalp lesions. The lesions may occur distant to the skin lesions and do not apparently represent a skin down to deep tissue full thickness pathology. These patients should also be screened for ocular abnormalities16 as literature shows a correlation between ophthalmological and neurological involvement in patients with linear forms.22 Among the ocular manifestations, anterior uveitis is the most frequent one although there can be direct involvement of the eye, eyelid, eyelashes and orbit with the JLS lesions. Being usually asymptomatic, an ophthalmological screening is recommended at the time of diagnosis and during follow-up.

Indeed, since linear scleroderma of the face is significantly associated with odontostomatologic abnormalities,23 an orthodontic and maxillofacial evaluation at diagnosis and during follow-up is recommended. Joint approaches to treatment may be needed, including with plastic surgery input, when there are severe wasting of facial fat compartments or in the linear scalp lesions. A comprehensive review on the most recent advances on monitoring and treatment of JLS has been recently published.24

Treatment

Over the years, many treatments have been tried for JLS24 frequently without significant evidence base. Management decisions should be based on the particular subtype of disease, the site of lesions and on the degree of activity.

Most recent reported data show effectiveness of systemic corticosteroids in association with methotrexate (MTX) in patients with active JLS, particularly in progressive linear scleroderma and generalised or pansclerotic morphoea. Experience with steroids for treatment of active disease in children is reported in many papers, mainly in combination with MTX.25 26 Literature evidence suggests that systemic corticosteroids are effective and well tolerated in the active phase of the disease and this was confirmed by the expert panel.27 Data from the literature mainly suggest two administration regimens: oral prednisone at a dosage of 1–2 mg/kg/day for a period of 2–3 months with subsequent gradual tapering,28 or pulsed high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg) with various administration schedules.25 26 As far as the preferred administration route and dosage is concerned, no agreement has been achieved by the expert committee, therefore both alternatives are accepted. In the future, comparative trials of the two regimes could be considered.

As for the disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs that should be started in combination with corticosteroids, experts recommend MTX as first-step treatment. The only randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial published to date clearly shows the safety and efficacy of oral MTX in the treatment of JLS, initially in combination with corticosteroids.28 A weekly regimen of 15 mg/m2 MTX as single oral or subcutaneous dose is recommended. During the first 3 months of therapy, a course of corticosteroids, namely prednisone, should be used as adjunctive ‘bridge therapy’.28 Prolonged remission off medication is more likely to occur in patients treated for more than 12 months after achieving clinical remission on medication.29 30 Therefore, once an acceptable clinical improvement is achieved, MTX should be maintained for at least 12 months before tapering, although longer term treatments are also frequently used.

As for safety, several reports show that low-dose MTX is safe and well tolerated in the paediatric population,25–30 with a low rate of non-severe side effects including nausea, headache and transient hepatotoxicity.26 28 30

If MTX is ineffective or the disease relapses after a period of clinical remission (ie, cutaneous disease progression or severe extracutaneous manifestations) or in the case of MTX-intolerant patients, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) at a dose of 500–1000 mg/m2 may be used, despite that lack of good evidence in the literature.31 A retrospective study on efficacy of MMF, mostly in combination with MTX, in severe refractory JLS has shown clinical improvement in all patients and a good safety profile.31 More trials on the safety and efficacy of MMF in a larger paediatric population with localised scleroderma are needed.

Circumscribed morphoea is generally of cosmetic concern only and should be treated with topical treatment. Some studies report efficacy of imiquimod (IMQ) in decreasing the skin thickening of isolated plaques of circumscribed morphoea.32 33 IMQ is a novel immunomodulator which is effective in the treatment of keloids, genital warts and basal cell skin cancers. One of its modes of action is to upregulate a variety of cytokines including interferon α and γ. These interferons are capable of inhibiting collagen production by fibroblasts, likely by downregulating the production of transforming growth factor beta.34 35 Although published literature includes mainly adult data in low numbers of patients,33 IMQ appears to be safe in the paediatric population and despite limited evidence, the expert panel suggested its use in selected non-progressive or extended forms of JLS, although a formal trial is also recommended.

Phototherapy with ultraviolet (UV) light represents another possible therapeutic choice for JLS36 37 although data on its use in children are scarce. Medium-dose UVA1 therapy seems to be effective in improving skin softness and reducing skin thickness with a good safety profile in adults with localised scleroderma.36–38 Limitations for the use of phototherapy in children are the need for prolonged maintenance therapy, leading to a high cumulative dosage of irradiation, and the increased risk of potential long-term effects such as skin ageing and carcinogenesis.39

Although there are, to date, no published trials of biologics or combination treatments, surveys of clinical practice demonstrate that tacrolimus, cyclophosphamide and a number of biologics (including tumour necrosis factor or interleukin-6 inhibitors) are being used in some patients for resistant or CNS disease.40–43 There is also no high-level evidence regarding when to stop MTX or other immunosuppressive treatments. The expert panel suggested considering the withdrawal of MTX (or alternative disease-modifying drug) once the patient is in remission and off steroids for at least 1 year.

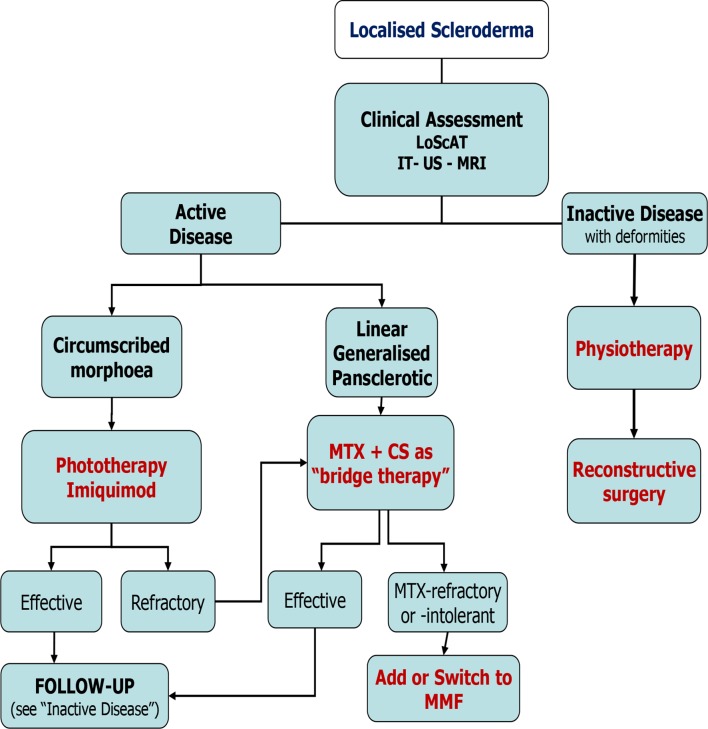

Based on consensus recommendations, a flow chart was proposed for JLS treatment (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for the treatment of newly diagnosed or refractory patients with juvenile localised scleroderma according to the clinical subtype. CS, corticosteroid; IT, infrared thermography; LoSCAT, Localized Scleroderma Cutaneous Assessment Tool; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MTX, methotrexate; US, ultrasound.

Discussion

The scleroderma working group of SHARE formulated a total of 22 recommendations for the management of JLS, based on a systematic literature review and consensus procedure.

Topics include assessment of skin lesions and extracutaneous involvement, and the use of topical and systemic treatment options.

In total, 1 overarching principle, 10 recommendations on assessment and 6 on therapy were accepted with ≥80% agreement among the experts.

Close monitoring of patients’ disease status and well-being by an experienced multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary team with expertise in localised scleroderma is essential for a good clinical outcome.

As in patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies or other rare connective tissue diseases all experts agree on the importance of managing JLS in specialised centres.44 As with all significant rare disorders, concentrating care in a few centres gives rise to a larger physician experience. In addition, European and international sharing of patients in studies provides evidence to improve standards of care. An important message from both the literature and the experience of experts is the requirement of a global evaluation of patients with JLS, focusing attention on the skin lesions and on possible extracutaneous involvement, which even though are rare can also be severe and potentially disabling. Validated scores for disease activity and damage are proposed in order to perform a structured assessment of outcome over time and to closely check their effect on the growth in children.

Recent evidence highlights the importance of treating skin disease aggressively as it is associated with high morbidity both physically and psychologically. Long-term follow-up studies are warranted to clarify complication risks and predictors of poor outcome. Given the disease rarity, international collaboration is crucial to recruit sufficient patients for future clinical trials with both current and innovative drugs.

To conclude, this SHARE initiative is based on expert opinion informed by the best available evidence and provides recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with JLS, along with other paediatric rheumatic diseases, with a view to improving their outcome in Europe. We anticipate that these guidelines will likely be adopted by physicians caring for patients with JLS outside Europe.

It will now be important to broaden discussion and test the reliability of these recommendations to the wider scientific community and to the patients.

Acknowledgments

This SHARE initiative has been endorsed by the executive committee of the Pediatric Rheumatology European Society and the International Society of Systemic Auto-Inflammatory Diseases.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Josef S Smolen

Contributors: FZ and IF are senior authors. NMW and SJV designed the SHARE initiative. RC, FS and NT performed the systematic literature review, supervised by FZ and IF. Validity assessment of selected papers was done by NMW, CB, RR, OK, TC, CSM, EMB, JA, SKFdeO and JC. Recommendations were formulated by FZ, RC and IF. The expert committee consisted of FZ, IF, JA, TC, EMB, CB, JC, TA and RR; they completed the online surveys and/or participated in the subsequent consensus meetings. SJV facilitated the consensus procedure using a nominal group technique. FZ, RC and FS wrote the manuscript, with contribution and approval of all coauthors.

Funding: This project was supported by a grant from the European Agency for Health and Consumers (EAHC), grant number 20111202.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study did not involve human participants, therefore the ethical approval was not needed.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional unpublished data from the study are available by just sending an email to RC (roberta.culpo@gmail.com) or FZ (francescozulian58@gmail.com).

References

- 1. Wulffraat NM, Vastert B. Time to share. Pediatric Rheumatology 2013;11 10.1186/1546-0096-11-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Laxer RM, Zulian F, scleroderma L. Localized scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2006;18:606–13. 10.1097/01.bor.0000245727.40630.c3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dougados M, Betteridge N, Burmester GR, et al. . EULAR standardised operating procedures for the elaboration, evaluation, dissemination, and implementation of recommendations endorsed by the EULAR standing committees. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:1172–6. 10.1136/ard.2004.023697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Collaboration T C Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, et al. . EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: Management. Report of a task Force of the EULAR standing Committee for international clinical studies including therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1312–24. 10.1136/ard.2006.055269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Herrick AL, Ennis H, Bhushan M, et al. . Incidence of childhood linear scleroderma and systemic sclerosis in the UK and ireland. Arthritis Care Res 2010;62:213–8. 10.1002/acr.20070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zulian F, Athreya BH, Laxer R, et al. . Juvenile localized scleroderma: clinical and epidemiological features in 750 children. An international study. Rheumatology 2006;45:614–20. 10.1093/rheumatology/kei251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zulian F, Vallongo C, de Oliveira SKF, et al. . Congenital localized scleroderma. J Pediatr 2006;149:248–51. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.04.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Martini G, Fadanelli G, Agazzi A, et al. . Disease course and long-term outcome of juvenile localized scleroderma: experience from a single pediatric rheumatology centre and literature review. Autoimmun Rev 2018;17:727–34. 10.1016/j.autrev.2018.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arkachaisri T, Vilaiyuk S, Li S, et al. . The localized scleroderma skin severity Index and physician global assessment of disease activity: a work in progress toward development of localized scleroderma outcome measures. J Rheumatol 2009;36:2819–29. 10.3899/jrheum.081284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Arkachaisri T, Vilaiyuk S, Torok KS, et al. . Development and initial validation of the localized scleroderma skin damage index and physician global assessment of disease damage: a proof-of-concept study. Rheumatology 2010;49:373–81. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kelsey CE, Torok KS. The localized scleroderma cutaneous assessment tool: responsiveness to change in a pediatric clinical population. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;69:214–20. 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Martini G, Murray KJ, Howell KJ, et al. . Juvenile-onset localized scleroderma activity detection by infrared thermography. Rheumatology 2002;41:1178–82. 10.1093/rheumatology/41.10.1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li SC, Liebling MS, Haines KA. Ultrasonography is a sensitive tool for monitoring localized scleroderma. Rheumatology 2007;46:1316–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/kem120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li SC, Liebling MS, Haines KA, et al. . Initial evaluation of an ultrasound measure for assessing the activity of skin lesions in juvenile localized scleroderma. Arthritis Care Res 2011;63:735–42. 10.1002/acr.20407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zulian F, Vallongo C, Woo P, et al. . Localized scleroderma in childhood is not just a skin disease. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:2873–81. 10.1002/art.21264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schanz S, Henes J, Ulmer A, et al. . Response evaluation of musculoskeletal involvement in patients with deep morphea treated with methotrexate and prednisolone: a combined MRI and clinical approach. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013;200:W376–W382. 10.2214/AJR.12.9335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schanz S, Fierlbeck G, Ulmer A, et al. . Localized scleroderma: Mr findings and clinical features. Radiology 2011;260:817–24. 10.1148/radiol.11102136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chiu YE, Vora S, Kwon E-KM, et al. . A significant proportion of children with morphea en coup de sabre and Parry-Romberg syndrome have neuroimaging findings. Pediatr Dermatol 2012;29:738–48. 10.1111/pde.12001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blaszczyk M, Królicki L, Krasu M, et al. . Progressive facial hemiatrophy: central nervous system involvement and relationship with scleroderma en coup de sabre. J Rheumatol 2003;30:1997–2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Flores-Alvarado DE, Esquivel-Valerio JA, Garza-Elizondo M, et al. . Linear scleroderma en coup de sabre and brain calcification: is there a pathogenic relationship? J Rheumatol 2003;30:193–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zannin ME, Martini G, Athreya BH, et al. . Ocular involvement in children with localised scleroderma: a multi-centre study. Br J Ophthalmol 2007;91:1311–4. 10.1136/bjo.2007.116038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Trainito S, Favero L, Martini G, et al. . Odontostomatologic involvement in juvenile localised scleroderma of the face. J Paediatr Child Health 2012;48:572–6. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2012.02435.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zulian F. Scleroderma in children. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2017;31:576–95. 10.1016/j.berh.2018.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Uziel Y, Feldman BM, Krafchik BR, et al. . Methotrexate and corticosteroid therapy for pediatric localized scleroderma. J Pediatr 2000;136:91–5. 10.1016/S0022-3476(00)90056-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Weibel L, Sampaio MC, Visentin MT, et al. . Evaluation of methotrexate and corticosteroids for the treatment of localized scleroderma (morphoea) in children. Br J Dermatol 2006;155:1013–20. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07497.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Joly P, Bamberger N, Crickx B, et al. . Treatment of severe forms of localized scleroderma with oral corticosteroids: follow-up study on 17 patients. Arch Dermatol 1994;130:663–5. 10.1001/archderm.1994.01690050133027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zulian F, Martini G, Vallongo C, et al. . Methotrexate treatment in juvenile localized scleroderma: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:1998–2006. 10.1002/art.30264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zulian F, Vallongo C, Patrizi A, et al. . A long-term follow-up study of methotrexate in juvenile localized scleroderma (morphea). J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;67:1151–6. 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.03.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Torok KS, Arkachaisri T. Methotrexate and corticosteroids in the treatment of localized scleroderma: a standardized prospective longitudinal single-center study. J Rheumatol 2012;39:286–94. 10.3899/jrheum.110210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Martini G, Ramanan AV, Falcini F, et al. . Successful treatment of severe or methotrexate-resistant juvenile localized scleroderma with mycophenolate mofetil. Rheumatology 2009;48:1410–3. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pope E, Doria AS, Theriault M, et al. . Topical imiquimod 5% cream for pediatric plaque morphea: a prospective, multiple-baseline, open-label pilot study. Dermatology 2011;223:363–9. 10.1159/000335560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dytoc M, Ting PT, Man J, et al. . First case series on the use of imiquimod for morphoea. Br J Dermatol 2005;153:815–20. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06776.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wooten JM. Imiquimod. South Med J 2005;98 10.1097/01.smj.0000170854.47749.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Spaner DE, Miller RL, Mena J, et al. . Regression of lymphomatous skin deposits in a chronic lymphocytic leukemia patient treated with the Toll-like receptor-7/8 agonist, imiquimod. Leuk Lymphoma 2005;46:935–9. 10.1080/10428190500054426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kreuter A, Hyun J, Stücker M, et al. . A randomized controlled study of low-dose UVA1, medium-dose UVA1, and narrowband UVB phototherapy in the treatment of localized scleroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;54:440–7. 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.11.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Su O, Onsun N, Onay HK, et al. . Effectiveness of medium-dose ultraviolet A1 phototherapy in localized scleroderma. Int J Dermatol 2011;50:1006–13. 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04843.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. de Rie MA, Enomoto DNH, de Vries HJC, et al. . Evaluation of medium-dose UVA1 phototherapy in localized scleroderma with the cutometer and fast Fourier transform method. Dermatology 2003;207:298–301. 10.1159/000073093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Staberg B, Wulf HC, Klemp P, et al. . The carcinogenic effect of UVA irradiation. J Invest Dermatol 1983;81:517–9. 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12522855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li SC, Feldman BM, Higgins GC, et al. . Treatment of pediatric localized scleroderma: results of a survey of North American pediatric rheumatologists. J Rheumatol 2010;37:175–81. 10.3899/jrheum.090708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Martini G, Campus S, Raffeiner B, Bernd R, et al. . Tocilizumab in two children with pansclerotic morphoea: a hopeful therapy for refractory cases? Clin Exp Rheumatol 2017;35 Suppl 106:211–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Foeldvari I, Anton J, Friswell M, et al. . Tocilizumab is a promising treatment option for therapy resistant juvenile localized scleroderma patients. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2017;2:203–7. 10.5301/jsrd.5000259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lythgoe H, Baildam E, Beresford MW, et al. . Tocilizumab as a potential therapeutic option for children with severe, refractory juvenile localized scleroderma. Rheumatology 2018;57:398–401. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Enders FB, Bader-Meunier B, Baildam E, et al. . Consensus-based recommendations for the management of juvenile dermatomyositis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:329–40. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

annrheumdis-2018-214697supp001.pdf (170KB, pdf)

annrheumdis-2018-214697supp002.htm (69.9KB, htm)