ABSTRACT

The two types of thermogenic fat cells, beige and brown adipocytes, play a significant role in regulating energy homeostasis. Their development and thermogenesis are tightly regulated by dynamic epigenetic mechanisms, which could potentially be targeted to treat metabolic disorders such as obesity. However, we are just beginning to catalog and understand these dynamic changes. In this review, we will discuss the current understanding of the role of DNA (de)methylation events in beige and brown adipose biology in order to highlight the holes in our knowledge and to point the way forward for future studies.

KEYWORDS: Epigenetics, DNA methylation, brown adipocytes, beige adipocytes, obesity, type 2 diabetes

Introduction

At least three types of adipose tissue exists in mammals: white, beige, and brown [1,2]. White adipocytes store excess energy as triglycerides and release them as needed, whereas brown adipocytes burn that energy to create heat [1,2]. Beige adipocytes sit between the two phenotypes, seemingly alternating between storing energy and burning it [1,2]. In rodents, classical brown adipose tissue exists in defined anatomical depots, such as the interscapular regions [1,2]. Concordantly, human studies detect thermogenic adipocytes around the neck, clavicle and spinal cord [3–7] that burn glucose and fatty acids [8,9]. Beige adipocytes aren’t in depots, but instead, are interspersed within white adipose tissue (WAT) [10].

For thermogenesis, both beige and brown adipocytes have abundant mitochondria to oxidize fatty acids, thus generating heat via uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1)-dependent and independent mechanisms [10,11]. Beige adipocytes biogenesis in WAT is induced by various environmental cues, including cold exposure, exercise, and PPARγ agonist [12,13], in a process called ‘browning’ or ‘beiging’[14]. Conversely, they undergo ‘whitening’ in response to thermoneutrality, impaired β-adrenergic signaling, lipase deficiency, and other cues [15]. Brown adipocytes also exhibit a certain degree of flexibility in their thermogenic gene program and morphology [16,17]. Because chronic cold acclimatization in humans leads to increased adipose thermogenic activity, which leads to increased energy expenditure [18,19], beige and brown adipocytes are an attractive therapeutic target for obesity and related metabolic diseases [19–21].

Studies strongly suggest that DNA (de)methylation plays a critical role in thermogenic adipose development and gene regulation. The reversible nature of epigenetic changes raises hope for therapeutic interventions that can reverse deleterious epigenetic programing as a means to prevent or treat relevant metabolic disorders. However, a deeper understanding is needed before medical therapies can be developed to target the epigenome. Here, we will discuss the current understanding of the role of DNA (de)methylation events in beige and brown adipose biology, with a focus on their development and gene regulation.

DNA (De)methylation in brown adipogenesis

PR domain–containing 16 protein (PRDM16) is a key developmental transcriptional regulator that commits progenitors to the brown adipogenic lineage and maintains brown adipocyte identity [22]. Prdm16 is enriched with CpG sites around its transcription start site, and hypomethylation at three specific regions of its promoter, likely mediated by the TET proteins, leads to increased Prdm16 expression during brown adipogenesis [23,24]. Moreover, reducing the level of α-ketoglutarate (αKG), a co-factor for the TET enzymes, leads to reduced demethylation of Prdm16 and impaired brown adipocyte development and function in mutant mice carrying loss-of-function of AMPKa1 [23].

To find loci important for brown adipose development, two independent DNA methylome studies were conducted to identify differentially methylated regions between white and brown adipocytes. The first study differentiated stromal vascular cells into inguinal and brown adipose cells in vitro [25]. The authors found that white adipogenesis has more hypermethylation overall than brown adipogenesis, and it is located mostly at intronic and intergenic regions. On the other hand, brown adipocytes have hypomethylated exonic regions that are significantly enriched for genes involved in brown fat functions such as the mitochondrial respiratory chain and fatty acid oxidation [25]. Notably, several Hox transcription factors are differentially methylated, some of which are linked to adipogenesis and diabetes [26,27]. For example, Hoxc9 is a well-established adipocyte marker [28], and Hoxc9 and Hoxc10 promoter methylation is inversely correlated with their gene expression in brown adipose tissue.

The second global study compared the DNA methylation profile of primary white vs. brown pre-adipocytes, among other cell types. Here, authors concluded that the DNA methylome is greatly similar between white and brown adipocytes [29]. However, there are multiple variables that could account for the discrepancy, including the cell types used (in vitro differentiated vs. primary cells), differential genome coverages due to the profiling method (reduced representation bisulfite sequencing vs. restriction hallmark genomic scanning), and the number of comparative analyses (two cell types vs. multiple comparisons between multiple cell types). Future genome-wide studies using whole-genome bisulfite sequencing are needed to compare, at base-pair resolution, the DNA methylation events between white and brown adipogenesis.

There are likely many regions involved in thermogenic adipogenesis that are controlled epigenetically, as global inhibition of (de)methylation greatly impacts general adipogenesis. The expression of TETs, the mediators of DNA demethylation, is upregulated in tissue culture models of both white and brown adipogenesis [23,30]. In addition, TET1 appears to use a physical interaction with a nuclear receptor (PPARγ) to target adipose genes during differentiation [31,32]. This results in demethylation and H3K4me1/H3K27ac around PPARγ binding sites in 3T3-L1 adipocytes [31–33]. Interestingly, in mature adipocytes, TET2 facilitates the transcriptional activity of PPARγ and the insulin-sensitizing efficacy of PPARγ agonist by sustaining PPARγ DNA binding at certain target loci [34]. These studies employed non-brown/beige adipocyte cell lines, yet it is likely that the TETs play additional roles in thermogenic adipocytes – outside of their effect on Prdm16. These roles require further studies using beige and brown adipocyte models.

Opposing the TETs are DNMTs, the mediators of DNA methylation. No specific role in brown adipogenesis has been found for DNMTs; however, they are likely important, as they have huge effects on general adipogenesis. Pharmacological and genetic inhibition of DNMTs appears to have biphasic impact on adipogenesis. Administering DNMT inhibitor prior to or during the early stages of adipogenesis enhanced adipogenesis [35–38]. This holds true in multiple tissue culture models including multipotent C3H10T1/2, ST2 cells, and pre-white adipocytes 3T3-L136–[38]. However, the opposite effect is observed when the inhibitor is added at a later stage of differentiation [39]. Knockdown of Dnmt1 and Dnmt3a during clonal expansion or early adipogenesis (day 0–2) impairs 3T3-L1 adipogenesis [39–41] but promotes lipid accumulation when knocked down on day 5 [39].

The specific effect of these DNMTs may depend on their expression pattern. Dnmt1 expression is transiently increased during the mitotic clonal expansion phase [42], which is critical for in vitro adipogenesis [43], and reduced in later stages of differentiation [42]. By contrast, Dnmt3a expression is increased during later stages of adipogenesis, while Dnmt3b expression remains low and relatively stable during differentiation. Together, these studies suggest that DNA methylation, along with DNMT1 and 3a, has complex roles in adipogenesis depending on the stage of adipose conversion. However, another group reported that DNMT1 is anti-adipogenic even during early phases by showing that DNMT1 is necessary for maintaining DNA methylation and repressive H3K9 histone methylation at key adipogenic genes, such as Pparg, during clonal expansion [42]. Such a discrepancy might be due to the knockdown efficiency of Dnmt1 or tissue culture variables between the two laboratory environments. While it is likely that DNMTs play a role in brown adipogenesis, future studies are necessary to reveal their exact functional role.

DNA methylation in brown adipocyte gene regulation

UCP1 is important for adipocyte thermogenesis, as it uncouples the respiratory chain, allowing for fast substrate oxidation with a low rate of ATP production. Brown adipocyte-specific Ucp1 expression is associated with reduced CpG methylation at the Ucp1 enhancer and can be further reduced by DNMT inhibitor in brown adipocyte HIB1B cells [44]. Moreover, cold adaptation causes DNA hypomethylation at the CpG sites within two of the cyclic AMP response elements in the Ucp1 promoter [44]. Consistent with this, under cold conditions, the Ucp1 locus is more enriched in the active histone mark (H3K4me3) in brown adipose tissue (BAT), whereas the repressive mark (H3K9me2) is enriched in white adipose tissue (WAT) [44].

Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α) is required for the cold-inducible expression of Ucp1 [45]. PGC-1α is a transcriptional co-activator that regulates genes involved in energy metabolism, and its methylation changes in the context of insulin resistance and exercise in tissues like skeletal muscle [46,47]. However, whether temperature changes cause changes in Ppargc1a methylation in beige and brown adipocytes remains to be uncovered.

Another study suggests that DNA methylation is involved in the brown adipocyte–specific expression of Vaspin (visceral adipose tissue–derived serine protease inhibitor; SERPINA12). Vaspin is an adipokine suggested to be anti-diabetic and anti-obesogenic [48] because it inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis and improves insulin signal transduction [49–51]. A microarray study found that Vaspin level is strongly upregulated in BAT after cold exposure, and another study found that Vaspin promoter regions in BAT are more hypomethylated than white adipose depots in mice fed with normal chow. Moreover, acute cold exposure further decreases methylation levels, notably at one CpG site (CpG-525). Supporting the in vivo findings, in vitro experiments demonstrate that vaspin mRNA expression is markedly upregulated after treating BAT pre-adipocytes with the DNMT inhibitor 5-aza-2ʹ-deoxycytidine for 48h prior to differentiation. Future studies are warranted to address the causal role of DNA methylation in brown adipose–specific gene regulation in response to various physiological stimuli.

DNA methylation in intergenerational and transgenerational brown adipocyte function

Intergenerational effects occur when the parental environment (F0) directly affects their germ cells or developing fetus (F1). A true transgenerational effect can only be proven if the effect of exposure is transmitted to the F2 (when parental exposure occurred before conception) or F3 (when maternal exposure occurred during pregnancy) [52]. Accumulating evidence supports that DNA methylation plays an important role in the heritability of obesity and other metabolic disorders. A classic example is the Agouti (Avy) mouse model. Ectopic expression of the Agouti gene during development, due to hypomethylation of the cryptic promoter, results in agouti fur, as well as adult-onset obesity, diabetes, and tumorigenesis [53]. The tendency for obesity is exacerbated when the Avy allele comes from an obese Avy mother [54], and this intergenerational effect is partially reversed by supplementing with methyl-donors, which promote DNA hypermethylation [54]. In addition, in humans, several genes important for development and metabolism, such as IGF2 and LEP, are differentially methylated in newborns that were prenatally exposed to famine and overnutrition [55,56].

A recent study revealed the link between DNA methylation and the intergenerational impact of environmental exposure on brown adipose activity [57]. Notably, cold exposure in males, but not females, prior to conception results in increased cold tolerance and improved whole-body metabolism in male offspring in association with enhanced expression of UCP1 in BAT [57]. This intergenerational transmission is associated with altered DNA methylation at multiple genomic loci within the sperm – most prominently in the gene body of Adrb3, which encodes a protein that mediates β-adrenergic stimulation in BAT, was hypomethylated in sperm [57]. This led to increased expression of Adrb3 in inguinal, epididymal, and BAT of the cold exposed offsprings [57]. This study supports the possibility that DNA methylation underlies the epigenetic basis of the sexually dimorphic inheritance of prenatal cold exposure.

Another intriguing study showed that neonates born to obese wild-type mice have reduced brown adipose activity [23], a finding that is correlated with obesity [19,58]. These mice have reduced Prdm16 expression, in association with a reduced α-KG level, due to DNA hypermethylation at Prdm16 [23]. As a result, Ucp1 expression is reduced in these offspring, impairing the ability to maintain body temperature in response to cold [23]. Interestingly, administering AMPK agonists, like metformin and AICAR, which increase α-KG level by activating AMPK-dependent signaling pathways after birth, rescues the inherited obesity-induced suppression of brown adipogenesis and adaptive thermogenesis in offspring [23]. Consistent with this mouse study, a human study reported that maternal obesity increases DNA methylation in the Prdm16 promoter in the placenta at birth [59].

Zinc-finger protein 423 (Zfp423) is a preadipocyte commitment factor during fetal development [60]. It maintains white adipocyte identity by suppressing EBF2/PPARγ-dependent Prdm16 induction [61]. Maternal obesity led to DNA hypomethylation at Zfp423 and the increased gene expression in whole fetal tissues from embryos, which results in increased adipogenesis in the offspring at weaning and increased susceptibility to obesity later in life [62]. Similar to this study, a global profiling study detected DNA hypomethylation at Zfp423 promoter regions in the adipose tissue from obese dams compared to controls [63].

Another protein involved in transgenerational regulation is PPARγ, which is the master transcription factor for both white and brown adipogenesis and is involved in brown adipocyte development and thermogenic gene regulation [64,65]. Offspring with obese mothers have persistently lower PPARγ expression due to higher epigenetic repression, such as DNA hypermethylation and fewer active histone markers, at the Pparg promoter region [66]. Follow-up studies are necessary to address whether these DNA methylation and transcriptional changes impact brown/beige adipose development in neonates and later in life. In addition, more studies are needed to determine whether this altered thermogenic fat biology and its associated metabolic effects are truly transgenerational and whether DNA (de)methylation is involved in that process.

Conclusions and future perspectives

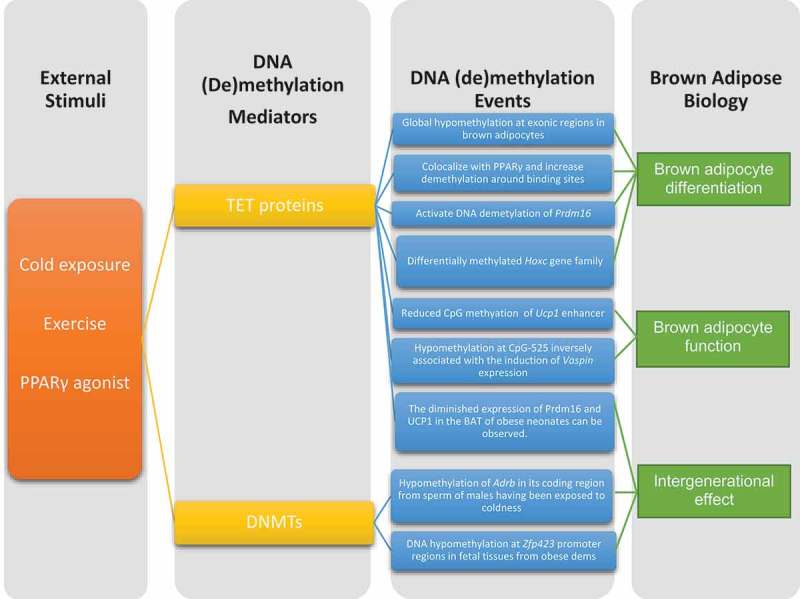

Studies strongly suggest that DNA (de)methylation plays a critical role in brown adipose development and thermogenic gene regulation (summarized in Figure 1). However, a deeper understanding is needed before we can target them in the treatment of obesity and related disorders. For example, what is the role of DNA (de)methylation in regulating ‘browning’ and ‘whitening’ and how dynamically are they regulated in response to various external cues? Also, little is known about the putative interaction between DNA (de)methylation and other epigenetic mechanisms in governing thermogenic brown/beige adipogenesis and plasticity. Furthermore, it’s crucial to investigate whether the machinery is functionally implicated in thermogenic brown/beige adipose development and function in humans. In conclusion, elucidating the role of DNA (de)methylation in brown and beige adipose biology will shed light on effective therapeutic interventions for obesity and obesity-related human diseases.

Figure 1.

Summary of external stimuli and DNA (de)methylation machinery and events that affect thermogenic adipose biology.

Funding Statement

This work was supported NIH R01 NIDDK DK116008-01 to SK;National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [DK116008].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported NIH R01 NIDDK DK116008-01 to SK.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Author Contributions

SK and HX co-wrote manuscript and HX did artwork.

References

- [1].Lidell ME, Betz MJ, Leinhard OD, et al. Evidence for two types of brown adipose tissue in humans. Nat Med. 2013. DOI: 10.1038/nm.3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Peirce V, Carobbio S, Vidal-Puig A.. The different shades of fat. Nature. 2014. DOI: 10.1038/nature13477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hany TF, Gharehpapagh E, Kamel EM, et al. Brown adipose tissue: A factor to consider in symmetrical tracer uptake in the neck and upper chest region. Eur J Nucl Med. 2002. DOI: 10.1007/s00259-002-0902-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cypess AM, Lehman S, Williams G, et al. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2009. DOI: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181ac8aa2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Vanhommerig JW, Smulders NM, et al. Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in healthy men. N Engl J Med. 2009. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Nedergaard J, Bengtsson T, Cannon B. Unexpected evidence for active brown adipose tissue in adult humans. Am J Physiol Metab. 2007. DOI: 10.1152/ajpendo.00691.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Virtanen KA, Lidell ME, Orava J, et al. Functional brown adipose tissue in healthy adults. N Engl J Med. 2009. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Orava J, Nuutila P, Lidell ME, et al. Different metabolic responses of human brown adipose tissue to activation by cold and insulin. Cell Metab. 2011. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ouellet V, Labbé SM, Blondin DP, et al. Brown adipose tissue oxidative metabolism contributes to energy expenditure during acute cold exposure in humans. J Clin Invest. 2012. DOI: 10.1172/JCI60433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wu J, Boström P, Sparks LM, et al. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell. 2012. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Shabalina IG, Petrovic N, deJong JMA, et al. UCP1 in Brite/Beige adipose tissue mitochondria is functionally thermogenic. Cell Rep. 2013. DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Loft A, Forss I, Siersbæk MS, et al. Browning of human adipocytes requires KLF11 and reprogramming of PPARγ superenhancers. Genes Dev. 2015. DOI: 10.1101/gad.250829.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Petrovic N, Walden TB, Shabalina IG, et al. Chronic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) activation of epididymally derived white adipocyte cultures reveals a population of thermogenically competent, UCP1-containing adipocytes molecularly distinct from classic brown adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2010. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M109.053942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Nedergaard J, Cannon B. The browning of white adipose tissue: some burning issues. Cell Metab. 2014. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kotzbeck P, Giordano A, Mondini E, et al. Brown adipose tissue whitening leads to brown adipocyte death and adipose tissue inflammation. J Lipid Res. 2018. DOI: 10.1194/jlr.M079665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ikeda K, Maretich P, Kajimura S. The common and distinct features of brown and beige adipocytes. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.tem.2018.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Roh HC, Tsai LTY, Shao M, et al. Warming induces significant reprogramming of beige, but not brown, adipocyte cellular identity. Cell Metab. 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Van der Lans AAJJ, Hoeks J, Brans B, et al. Cold acclimation recruits human brown fat and increases nonshivering thermogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2013. DOI: 10.1172/JCI68993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yoneshiro T, Aita S, Matsushita M, et al. Recruited brown adipose tissue as an antiobesity agent in humans. J Clin Invest. 2013. DOI: 10.1172/JCI67803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Arch JRS. β3-adrenoceptor agonists: potential, pitfalls and progress. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002. DOI: 10.1016/S0014-2999(02)01421-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Cannon B. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev. 2004. DOI: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Seale P, Bjork B, Yang W, et al. PRDM16 controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature. 2008. DOI: 10.1038/nature07182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yang Q, Liang X, Sun X, et al. AMPK/α-ketoglutarate axis dynamically mediates DNA demethylation in the Prdm16 promoter and brown adipogenesis. Cell Metab. 2016. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ficz G, Branco MR, Seisenberger S, et al. Dynamic regulation of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mouse ES cells and during differentiation. Nature. 2011. DOI: 10.1038/nature10008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lim YC, Chia SY, Jin S, et al. Dynamic DNA methylation landscape defines brown and white cell specificity during adipogenesis. Mol Metab. 2016. DOI: 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Procino A, Cillo C. The HOX genes network in metabolic diseases. Cell Biol Int. 2013. DOI: 10.1002/cbin.10145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].He D, Wang J, Gao Y, et al. Differentiation of PDX1 gene-modified human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells into insulin-producing cells in vitro. Int J Mol Med. 2011. DOI: 10.3892/ijmm.2011.774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Scheele C, Larsen TJ, Nielsen S. Novel nuances of human brown fat. Adipocyte. 2014. DOI: 10.4161/adip.26520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sakamoto H, Suzuki M, Abe T, et al. Cell type-specific methylation profiles occurring disproportionately in CpG-less regions that delineate developmental similarity. Genes Cells. 2007. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yoo Y, Park JH, Weigel C, et al. TET-mediated hydroxymethylcytosine at the Pparγ locus is required for initiation of adipogenic differentiation. Int J Obes. 2017. DOI: 10.1038/ijo.2017.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fujiki K, Shinoda A, Kano F, et al. PPARγ-induced PARylation promotes local DNA demethylation by production of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Nat Commun. 2013. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms3262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Matsumura Y, Nakaki R, Inagaki T, et al. H3K4/H3K9me3 bivalent chromatin domains targeted by lineage-specific DNA methylation pauses adipocyte differentiation. Mol Cell. 2015. DOI: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Dubois-Chevalier J, Oger F, Dehondt H, et al. A dynamic CTCF chromatin binding landscape promotes DNA hydroxymethylation and transcriptional induction of adipocyte differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gku780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bian F, Ma X, Villivalam SD, et al. TET2 facilitates PPARγ agonist–mediated gene regulation and insulin sensitization in adipocytes. Metabolism. 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Taylor SM, Jones PA. Multiple new phenotypes induced in 10T 1 2 and 3T3 cells treated with 5-azacytidine. Cell. 1979. DOI: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90317-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bowers RR, Kim JW, Otto TC, et al. Stable stem cell commitment to the adipocyte lineage by inhibition of DNA methylation: role of the BMP-4 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0605789103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Chen YS, Wu R, Yang X, et al. Inhibiting DNA methylation switches adipogenesis to osteoblastogenesis by activating Wnt10a. Sci Rep. 2016. DOI: 10.1038/srep25283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sakamoto H, Kogo Y, Ohgane J, et al. Sequential changes in genome-wide DNA methylation status during adipocyte differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Yang X, Wu R, Shan W, et al. DNA methylation biphasically regulates 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation. Mol Endocrinol. 2016. DOI: 10.1210/me.2015-1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Guo W, Chen J, Yang Y, et al. Epigenetic programming of Dnmt3a mediated by AP2α is required for granting preadipocyte the ability to differentiate. Cell Death Dis. 2016. DOI: 10.1038/cddis.2016.378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Guo W, Zhang KM, Tu K, et al. Adipogenesis licensing and execution are disparately linked to cell proliferation. Cell Res. 2009. DOI: 10.1038/cr.2008.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Londono Gentile T, Lu C, Lodato PM, et al. DNMT1 is regulated by ATP-citrate lyase and maintains methylation patterns during adipocyte differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2013. DOI: 10.1128/MCB.01495-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Tang QQ, Lane MD. Adipogenesis: from stem cell to adipocyte. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-052110-115718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Shore A, Karamitri A, Kemp P, et al. Role of Ucp1 enhancer methylation and chromatin remodelling in the control of Ucp1 expression in murine adipose tissue. Diabetologia. 2010. DOI: 10.1007/s00125-010-1701-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Puigserver P, Wu Z, Park CW, et al. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell. 1998. DOI: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81410-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Patti ME. Gene expression in humans with diabetes and prediabetes: what have we learned about diabetes pathophysiology? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2004. DOI: 10.1097/01.mco.0000134359.23288.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Michael LF, Wu Z, Cheatham RB, et al. Restoration of insulin-sensitive glucose transporter (GLUT4) gene expression in muscle cells by the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.061035098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Weiner J, Rohde K, Krause K, et al. Brown adipose tissue (BAT) specific vaspin expression is increased after obesogenic diets and cold exposure and linked to acute changes in DNA-methylation. Mol Metab. 2017. DOI: 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Luo X, Li K, Zhang C, et al. Central administration of vaspin inhibits glucose production and augments hepatic insulin signaling in high-fat-diet-fed rat. Int J Obes. 2016. DOI: 10.1038/ijo.2016.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Brunetti L, Di Nisio C, Recinella L, et al. Effects of vaspin, chemerin and omentin-1 on feeding behavior and hypothalamic peptide gene expression in the rat. Peptides. 2011. DOI: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Klöting N, Kovacs P, Kern M, et al. Central vaspin administration acutely reduces food intake and has sustained blood glucose-lowering effects. Diabetologia. 2011. DOI: 10.1007/s00125-011-2137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Perez MF, Lehner B. Intergenerational and transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in animals. Nat Cell Biol. 2019. DOI: 10.1038/s41556-018-0242-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Morgan HD, Sutherland HGE, Martin DIK, et al. Epigenetic inheritance at the agouti locus in the mouse. Nat Genet. 1999. DOI: 10.1038/15490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Waterland RA, Travisano M, Tahiliani KG, et al. Methyl donor supplementation prevents transgenerational amplification of obesity. Int J Obes. 2008. DOI: 10.1038/ijo.2008.100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Heijmans BT, Tobi EW, Stein AD, et al. Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0806560105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Tobi EW, Lumey LH, Talens RP, et al. DNA methylation differences after exposure to prenatal famine are common and timing- and sex-specific. Hum Mol Genet. 2009. DOI: 10.1093/hmg/ddp353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Sun W, Dong H, Becker AS, et al. Cold-induced epigenetic programming of the sperm enhances brown adipose tissue activity in the offspring. Nat Med. 2018. DOI: 10.1038/s41591-018-0102-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Wang Q, Zhang M, Xu M, et al. Brown adipose tissue activation is inversely related to central obesity and metabolic parameters in adult human. PLoS One. 2015. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Côté S, Brisson D, Guérin R, et al. PRDM16 gene DNA methylation levels in the placenta are associated with maternal overweight and obesity at first trimester of pregnancy. Can J Diabetes. 2013. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Gupta RK, Arany Z, Seale P, et al. Transcriptional control of preadipocyte determination by Zfp423. Nature. 2010. DOI: 10.1038/nature08816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Shao M, Ishibashi J, Kusminski CM, et al. Zfp423 maintains white adipocyte identity through suppression of the beige cell thermogenic gene program. Cell Metab. 2016. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Yang QY, Liang JF, Rogers CJ, et al. Maternal obesity induces epigenetic modifications to facilitate Zfp423 expression and enhance adipogenic differentiation in fetal mice. Diabetes. 2013. DOI: 10.2337/db13-0433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Borengasser SJ, Zhong Y, Kang P, et al. Maternal obesity enhances white adipose tissue differentiation and alters genome-scale DNA methylation in male rat offspring. Endocrinology. 2013. DOI: 10.1210/en.2012-2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Inagaki T, Sakai J, Kajimura S. Transcriptional and epigenetic control of brown and beige adipose cell fate and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17(8):480–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Lasar D, Rosenwald M, Kiehlmann E, et al. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma controls mature brown adipocyte inducibility through glycerol kinase. Cell Rep. 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Liang X, Yang Q, Fu X, et al. Maternal obesity epigenetically alters visceral fat progenitor cell properties in male offspring mice. J Physiol. 2016. DOI: 10.1113/JP272123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]