Abstract

Objective:

To identify preferences for and use of short-acting hormonal (e.g., oral contraceptives, injectable contraception) or long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) among community college students in Texas.

Participants:

Female community college students, ages 18 to 24, at risk of pregnancy, sampled in Fall 2014 or Spring 2015 (N=966).

Methods:

We assessed characteristics associated with preference for and use of short-acting hormonal or LARC methods (i.e., more-effective contraception).

Results.

47% preferred short-acting hormonal methods and 21% preferred LARC, compared to 21% and 9%, respectively, who used these methods. 63% of condom and withdrawal users and 78% of nonusers preferred a more effective method. Many noted cost and insurance barriers as reasons for not using their preferred more-effective method.

Conclusions.

Many young women in this sample who relied on less effective methods preferred to use more-effective contraception. Reducing barriers could lead to higher uptake in this population at high risk of unintended pregnancy.

Keywords: community college students, contraceptive use, contraceptive preferences, barriers to contraception

INTRODUCTION

Although young women aged 18 to 24 years old have the highest rates of unintended pregnancy and birth, they also experienced a greater decline in unintended pregnancy during the last decade compared to older women.1,2 This rapid decline has been attributed to increased use of any contraception but especially more effective methods of contraception, including intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implants (long-acting reversible contraception or LARC) and short-acting hormonal methods (oral contraceptive pill, contraceptive patch, vaginal ring, or injectable contraceptives).3,4 Despite increased use of these methods in the last decade,3 young women are still less likely to use LARC than women 25 to 34, even after excluding those who have not yet had sexual intercourse with a male.4 Nulliparous women are less likely to use highly effective methods of contraception than parous women and younger women are more likely to be nulliparous and have higher contraceptive failure rates than older women, resulting in an increased risk of unintended pregnancy. Indeed, a recent study found that among 18 to 24-year-olds, nulliparous young women were less likely to use LARC than parous women.5

One particular group of young women, those attending community colleges, may be at greater risk of unintended pregnancy.6 In addition to having a large proportion of students in the 18 to 24-year-old age range, community colleges often serve lower-income and minority students,7 who are more likely to experience unintended pregnancy than higher income women and non-Latina whites.2

Despite the fact that community college students make up almost half of all undergraduates in the U.S., little is known about their contraceptive use as most studies conducted with this population have focused on non-sexual health risk behaviors.8 One recent exception is a study of sexual behavior among 4,487 California community college students that found higher rates of risky sexual behavior and unintended pregnancy compared to four-year college students.6 Less effective methods (e.g., condoms and withdrawal) were the most frequently reported methods of contraception by students at 71%, followed by 46% who used oral contraceptives at last vaginal intercourse. No use of LARC was reported.6 Reliance on less effective methods in this population is higher than that seen among the 18 to 24-year-old sexually experienced women in the 2011–13 cycle of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) at risk of pregnancy. In that sample, 9% used LARC methods, 47% used short-acting hormonal methods, 21% used less effective methods like condoms and withdrawal and 23% did not use contraception (authors’ calculations). Thus, the limited existing data suggests higher risk of unintended pregnancy and lower use of more effective contraception among community college students compared to both the four-year college and national 18–24-year-old populations.

While the evidence on contraceptive method use is sparse for community college students, information about their contraceptive preferences is nonexistent. Thus, we do not know if community college students have low rates of using more effective contraceptive methods because they do not want to use them or because they experience barriers accessing them.

Inquiring directly about contraceptive method preference challenges an implicit, but longstanding, assumption that women are using the method they would prefer to use. Questions about method preference are not currently included in the main sources of population-based data, such as the NSFG and Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS). Studies using such data likely do not adequately capture women’s demand for specific methods, particularly methods that may be difficult for low-income women to access because they are expensive or require a health care visit. By asking about women’s preferences, we are able to detect the presence and level of unmet demand for more effective methods of contraception, as well as speculate on the consequences of failing to meet these preferences.

Community colleges may have student populations at higher risk of pregnancy, but they are less likely than four-year college students to be insured9 or to have on-campus health centers where women can obtain reproductive health services.10 This, together with the higher likelihood of being low income, suggests that many community college students may have less access to women’s health services than four-year college students. Therefore, it is critical to investigate not only contraceptive use in this understudied high-risk group, but also whether community college students are motivated to reduce their risk of unintended pregnancy by using effective contraception such as short-acting hormonal or LARC methods.

In this paper, we ask whether or not community college students in Texas are already getting the contraceptive methods they want, with a particular focus on assessing the proportion of unmet demand for more effective contraception, which we define as short-acting hormonal and LARC methods. We report on the contraceptive method use and preferences of women 18 to 24 years old attending community colleges in Texas and examine characteristics associated with women’s use and preferences for short-acting hormonal and LARC methods.

METHODS

Sample

We conducted this study in four community colleges in Dallas, South Texas, West Texas, and Houston. After securing approval from each college’s administration, we entered into a data sharing agreement with three of the colleges to receive student contact information from female students aged 18 to 24. The South and West Texas sites provided us a list of 1500 randomly selected names and contact information for students attending the Fall 2014 and Spring 2015 semesters, respectively; the Dallas site supplied a list of 1098 students—779 who were enrolled in the Spring 2015 semester who had not flagged their school record as private and 319 additional unique students who were enrolled in Fall 2014. The Houston site did not release student contact information so we trained student workers to recruit participants from campus sites during the Spring 2015 semester. However, because we recruited participants differently at the Houston site, and only 118 students were recruited in this manner, we limit our sample to the three sites that provided us a list of students.a

We mailed a letter to sampled students alerting them that they would be receiving an email with a link to a 10-minute online survey about women’s health. Each letter also included $5, as providing the incentive up front has been shown to increase response rates.11–13 Students were also informed that participants would be entered into a drawing for one of three $100 gift cards. We sent non-respondents a paper survey with return envelope and postage after sending four email reminders. Health-related studies with community college students using similar data collection strategies have yielded response rates of between 24% and 34%.14–16 This study received approval from the institutional review boards at the University of Texas at Austin and at each of the participating colleges.

Measures

The 41-item survey collected information in English about women’s sexual activity, use of and payment for women’s health services, current contraceptive use and preferences, measures of socioeconomic status, as well as demographic characteristics. Due to extremely low use of progestin-only pills among young women aged 15 to 24,17 oral contraceptive users were not asked whether they used combined oral contraceptives or progestin-only pills. Because contraceptive use has been shown to vary according to women’s parity5,18–20 and relationship status,21,22 we created a composite variable that captures both marital status and parity. Women indicated their source for family planning care from a list specific to each recruitment site, which we later categorized as public clinic (e.g., federally qualified health clinic, university or county hospital-based clinic, or health department), Planned Parenthood, private doctor, or none. Women also reported the type of health insurance, if any, they used to pay for contraception and women’s health services. We classified women as low income (<200% of the 2014 federal poverty level23) using household income and family size. Participants lacking that information (21% of sample) were classified as low income if they received means-tested financial aid (Pell Grant), if they or a member of their household received means-tested government assistance (e.g., Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) or if they answered yes to five questions about material hardships experienced by household members during the 12 months prior to the interview.

We asked if women had ever had sexual intercourse with a man, were currently sexually active with a male partner, and whether they were using contraception. We asked sexually experienced women to report their current contraceptive method; women not using a method were asked reasons for non-use and could indicate if they were pregnant or trying to get pregnant.

We captured women’s preferences for contraceptive methods by asking, “If you could use any birth control method you wanted, what method would you use?” and then provided a list of methods, including the option, “I don’t know.” We classified women’s current contraceptive use and preferences into the following categories: sterilization (tubal ligation or vasectomy); LARC (IUD or implant); short-acting hormonal methods, and less effective methods, which were primarily condoms and withdrawal. If women were not currently using their preferred method, we asked the reasons why not from a list of 12 options and an open response category. These categories and the contraceptive preference question were developed from previous work with postpartum24–26 and low-income women in Texas.27

Analysis

We limited our sample to women who had ever had sexual intercourse with a man, were not currently pregnant or trying to get pregnant, and responded to the questions on contraceptive use and preference for a contraceptive method. We also excluded women who were using sterilization and those who stated a preference for sterilization, because we are interested in use of reversible contraception.

Using χ2 tests, we assessed factors associated with two outcomes: a preference for more-effective methods of contraception and use of a more-effective method among women who expressed a preference for one using. Then, we conducted multivariable logistic regression analyses of these two outcomes adjusting for women’s sociodemographic characteristics. All analyses were performed using Stata 14.0.

RESULTS

Of the 4,098 surveys sent to students, 1,512 returned them for a response rate of 36.9% (range across colleges: 34.7%–40.5%). We found no statistically significant differences in age or ethnicity between respondents and non-respondents in the college sample for which we had that information. Among the respondents, 416 reported not being sexually experienced, 17 did not report whether they were sexually experienced, 42 were pregnant or trying to get pregnant, 22 used or preferred a permanent method, and 11 did not state a contraceptive preference, leaving 1,004 sexually experienced women at risk of unintended pregnancy. An additional 38 cases were excluded because of missing data on one or more of the independent variables, yielding a final analytic sample of 966 young women.

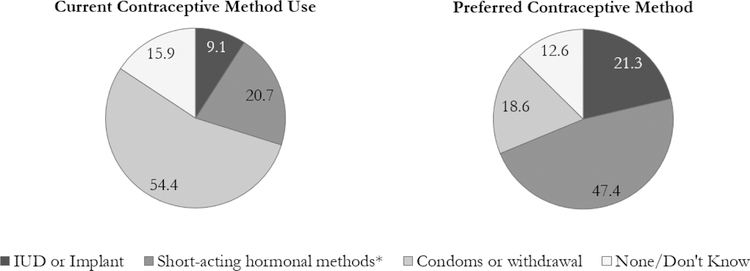

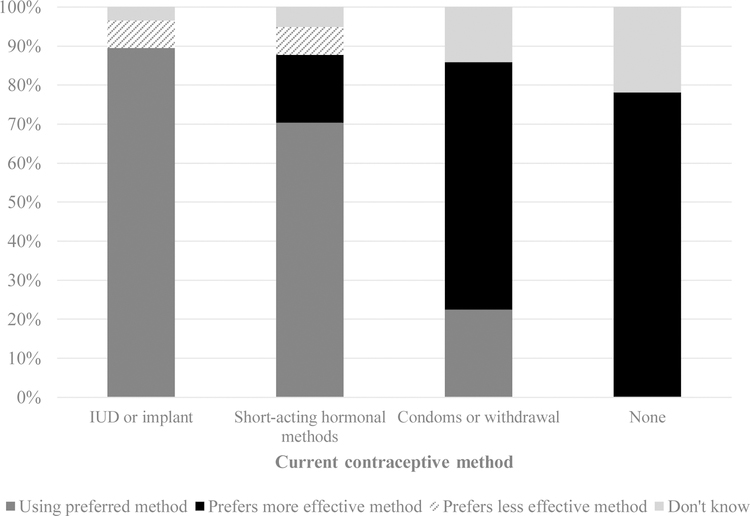

Over half of the women reported using condoms or withdrawal, followed by 22% who used short-acting hormonal methods, and just over 9% who used an IUD or implant (Figure 1). In addition, 16% reported using no method of contraception. However, 69% of the sample wanted to be using more-effective methods (short-acting hormonal: 47% and LARC: 21%), and 19% noted a preference for less effective methods. Moreover, large percentages of condom and withdrawal users (63%) and those who were not using a method (78%) expressed a preference for a more effective method (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Contraceptive method use and preferences among sexually experienced community college students in Texas.

Short-acting hormonal methods include the oral contraceptive pill, patch, ring, and injectable contraception (Depo-Provera); oral contraceptive pill users were not asked whether they used combined oral contraceptives or progestin-only pills

Figure 2. Contraceptive method use and preferences among sexually experienced community college students in Texas.

Short-acting hormonal methods include the oral contraceptive pill, patch, ring, and injectable contraception (Depo-Provera)

Among participants who wanted to use a short-acting hormonal or LARC method but were not using one of these methods, top reasons included not being able to afford the method, not having insurance, or their insurance did not cover the method (Table 1). Women also reported barriers such as not knowing where to get the method, not having made an appointment to get the method, or that it was too much of a hassle to get it. In addition, 23% of women whose preference was a short-acting hormonal method said they were not using the method because they were not currently sexually active.

Table 1.

Top reasons sexually experienced participants gave for not using their preferred LARC or short-acting hormonal method*

| Preferred method |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IUD or Implant (N=129) | Short-acting Hormonal Methods (N=320) | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Can’t afford it / don’t have insurance | 59 | 45.7 | 111 | 34.7 |

| Don’t know where to get it | 22 | 17.1 | 47 | 14.7 |

| Haven’t made an appointment to get it | 22 | 17.1 | 80 | 25.0 |

| Insurance doesn’t cover the method | 14 | 10.9 | 14 | 4.4 |

| Not currently sexually active | 10 | 7.8 | 74 | 23.1 |

| Too much of a hassle to get it | 7 | 5.4 | 29 | 9.1 |

Multiple responses valid

Short-acting hormonal methods include the oral contraceptive pill, patch, ring, and injectable contraception (Depo-Provera)

Preferences for more-effective methods of contraception varied across sociodemographic categories from a low of 56% for students of “other” race/ethnicity to a high of 81% for single students with children (Table 2). A higher percentage of women who saw private doctors, had one or more children, and participants from the West Texas college expressed a preference for these methods. Among women with a preference for a more-effective method, only 39% of women were using one (range: 14–70%). Those more likely to be using a more-effective method given a preference for one included older women (p=.001), African American or white women (p<.001), those with public or private insurance (p<.001), who saw a private doctor (p<.001), and who attended the Dallas or West Texas colleges (p<.001). Married women and single women with children also were more likely to be using their preferred more-effective method than single women without children (p<.001).

Table 2.

Preference for and use of more-effective methods of contraception† among sexually experienced community college students in Texas, by socio-demographic characteristics

| Preference for a more-effective method (n=966) |

Using a more-effective method among women with a preference for one (n=653) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n (%) | % with preference | p-value | n (%) | % using | p-value |

| Age | 0.661 | 0.001 | ||||

| 18–19 | 339 (35.1) | 67.9 | 227 (34.8) | 30.0 | ||

| 20–24 | 627 (64.9) | 69.2 | 426 (65.2) | 43.4 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.229 | <0.001 | ||||

| Hispanic | 748 (77.4) | 68.3 | 503 (77.0) | 34.6 | ||

| African American | 116 (12.0) | 68.1 | 78 (11.9) | 55.1 | ||

| White | 79 (8.2) | 77.2 | 59 (9.0) | 54.2 | ||

| Other | 23 (2.4) | 56.5 | 13 (2.0) | 30.8 | ||

| Low income ~<200% FPL | 0.997 | 0.358 | ||||

| No | 128 (13.3) | 68.8 | 88 (13.5) | 43.2 | ||

| Yes | 838 (86.8) | 68.7 | 565 (86.5) | 38.1 | ||

| Insurance Type | 0.046 | <0.001 | ||||

| None | 371 (38.4) | 64.2 | 231 (35.4) | 22.9 | ||

| Private | 404 (41.8) | 72.3 | 290 (44.4) | 47.2 | ||

| Public | 191 (19.8) | 70.2 | 132 (20.2) | 47.7 | ||

| Usual Source of Care | 0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| None | 394 (40.8) | 61.4 | 239 (36.6) | 13.8 | ||

| Private doctor | 332 (34.4) | 75.3 | 247 (37.8) | 60.3 | ||

| Public Clinic | 172 (17.8) | 70.9 | 119 (18.2) | 41.2 | ||

| Planned Parenthood | 68 (7.0) | 73.5 | 48 (7.4) | 45.8 | ||

| Relationship Status & Parity | 0.010 | <0.001 | ||||

| Single, no children | 748 (77.4) | 66.3 | 490 (75.0) | 31.0 | ||

| Married, no children | 40 (4.1) | 67.5 | 27 (4.1) | 70.4 | ||

| Single, has child(ren) | 113 (11.7) | 80.5 | 87 (13.3) | 56.3 | ||

| Married, has child(ren) | 65 (6.7) | 76.9 | 49 (7.5) | 67.4 | ||

| College Location | 0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Dallas | 254 (26.3) | 68.5 | 171 (26.2) | 48.0 | ||

| South Texas | 367 (38.0) | 62.4 | 226 (34.6) | 27.9 | ||

| West Texas | 345 (35.7) | 75.7 | 256 (39.2) | 42.2 | ||

| Total | 966 (100.0) | 68.7 | n/a | 653 (100.0) | 38.7 | n/a |

More-effective methods include injectables, oral contraceptive pill, patch, ring, implant, IUD

In multivariable-adjusted logistic regression analysis, women who obtained care from a private doctor or Planned Parenthood (both p≤.01), compared to those with no usual source of care, and who were single with children (p≤.01), compared to those who were single with no children, had higher odds of preferring a more-effective method (Table 3). Among women with a preference for a more-effective method, those with public or private insurance (both p≤.05), compared to those with no insurance, those with any usual source of care (p≤.001), married women with and without children and single women with children (p≤.001), compared to single women without children, had higher odds of using their preferred more-effective method.

Table 3.

Logistic regression models predicting preference for and use of a more-effective method† among sexually experienced community college students in Texas, by socio-demographic characteristics

| Preference for a more-effective method (n=966) | Using a more-effective method among women with a preference for one (n=653) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratios | 95% C.I. | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% C.I. |

| Age | ||||

| 18–19 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |

| 20–24 | 0.85 | 0.63–1.16 | 1.32 | 0.88–2.0 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| African American | 0.89 | 0.51–1.55 | 1.48 | 0.71–3.05 |

| White | 1.46 | 0.81–2.65 | 1.61 | 0.80–3.23 |

| Other | 0.55 | 0.23–1.34 | 0.46 | 0.12–1.88 |

| Low income ~<200% FPL | ||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 1.06 | 0.69–1.64 | 0.94 | 0.54–1.64 |

| Insurance Type | ||||

| None | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Private | 1.24 | 0.88–1.76 | 1.67* | 1.02–2.71 |

| Public | 1.00 | 0.67–1.51 | 1.94* | 1.12–3.37 |

| Usual Source of Care | ||||

| None | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Private doctor | 1.67** | 1.16–2.41 | 6.88*** | 4.18–11.35 |

| Public Clinic | 1.41 | 0.94–2.12 | 3.65*** | 2.06–6.48 |

| Planned Parenthood | 2.30** | 1.27–4.17 | 7.14*** | 3.36–8.55 |

| Relationship Status & Parity | ||||

| Single, no children | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Married, no children | 0.91 | 0.45–1.83 | 4.98*** | 1.91–13.01 |

| Single, has child(ren) | 2.21** | 1.32–3.68 | 3.18*** | 1.84–5.52 |

| Married, has child(ren) | 1.63 | 0.88–3.04 | 4.17*** | 2.03–8.55 |

| College Location | ||||

| Dallas | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| South Texas | 0.80 | 0.51–1.26 | 0.59 | 0.31–1.12 |

| West Texas | 1.57 | 0.99–2.50 | 1.20 | 0.65–2.21 |

| Constant | 1.35 | 0.73–2.49 | 0.08*** | 0.03–0.19 |

More-effective methods include injectables, oral contraceptive pill, patch, ring, implant, IUD

p ≤ 0.05;

p ≤ 0.01;

p ≤ 0.001

COMMENT

Our study demonstrates an unmet demand for more-effective contraception among female community college students, an understudied population that is at high risk of unintended pregnancy. We found that financial and health system barriers contribute to this unmet demand. Women without insurance were just as likely as women with insurance to prefer a short-acting hormonal or LARC method, but less likely to be using one of these methods. Indeed, high costs or lack of insurance were the most frequent reason women gave for not using their preferred more-effective method. This is particularly a problem for community college students; in our sample, we found that 38% were uninsured. This compares to results of a national survey in which just 4% of students attending primarily four-year institutions were uninsured.9 As demonstrated in other studies,28–31 many women will use a LARC method or short-acting hormonal contraceptive32 if cost barriers are removed, often leading to lower levels of unintended pregnancy.

These cost barriers may have been exacerbated by 2011 legislation that cut family planning funding dramatically and led to Planned Parenthood being excluded from state programs that supported family planning services.33 As a result, 25% of publicly funded clinic sites closed or discontinued providing family planning services in the state, and 54% fewer clients were served.34 Together, these outcomes could partially explain why only 7% of participants in this study cited Planned Parenthood as their usual source of care. Specialized family planning providers like Planned Parenthood are preferred by young women because they provide respectful and confidential services that are free or low-cost, and staff are considered knowledgeable about women’s health,35 suggesting that some women in this sample were not seeing a preferred provider. The budget cuts and exclusion of Planned Parenthood from state programs could have contributed to other young women not seeing a provider at all.

We also found that many young women who reported having a regular provider were not using their preferred more-effective method. In addition to potential cost or insurance barriers, this may be related to the fact that, for women preferring IUDs and implants, some health care providers may be misinformed about LARC protocols for adolescents and young women without children; a substantial fraction of US obstetrician/gynecologists believed that women without children were not appropriate candidates for LARC.36 Some also may lack training in LARC insertion.37 In addition to a lack of awareness of LARC by clinicians and the public,38 low-income young women may lack a usual health care provider who has the knowledge and skills to counsel and provide LARC methods.24,39–41

Similar to other studies,5,18–20 we found that single women with no children were less likely to be using more-effective methods than women with children. By measuring contraceptive preferences, we found that single women without children were no less likely to prefer more-effective methods than women with children. This suggests that women without children may experience more barriers to care.

Finally, young women in the West Texas site, which is in a city that borders Mexico, were more likely to have a preference for more-effective methods, suggesting that their proximity to Mexico—where LARC use is high and obtaining a LARC method is easier than in the US42—may shape social norms around contraception that promote a preference for more effective methods. However, women in West Texas were still no more likely than women in other parts of the state to overcome barriers to obtaining their preferred more-effective method.

Even though many women were not using their preferred more-effective method, we found greater use of LARC and short-acting hormonal methods in this sample of 18 to 24-year-old women at risk of pregnancy as compared to the NSFG and an earlier study of community college students in California. The NSFG sample was not restricted to low-income women so the lower use of short-acting hormonal methods in our sample is expected but the similar level of LARC use is perplexing, given the multiple barriers to more-effective methods of contraception low-income women in Texas face.27,34 On the other hand, higher use of LARC methods in this study compared to the 2007 California study could signal LARC’s growing popularity in recent years.3,43

Assisting community college students to obtain their preferred method of more-effective contraception would help them to achieve their educational goals. This is because unplanned pregnancy while attending community college increases the risk of dropping out—students who have a child while in college have a drop-out rate 65% higher than women who do not have a child during that time.10 Moreover, identifying approaches to help young community college students obtain their preferred method is important given that another study Texas found that postpartum women who were unable to access their preferred method were more likely to have an unintended pregnancy.25

Community colleges could implement several strategies to help students avoid an unintended pregnancy. Colleges could provide information about pregnancy prevention and contraceptive methods during orientation and in academic courses,10 as well as in campus events programming, and through peer-to-peer and staff-to-student mentoring.44 Colleges could also connect their students with local family planning services for low-income women, such as Title X clinics and other publicly funded services available to women based on income. Moreover, because contraceptive counseling increases use of LARC and other effective methods,5,28 providing contraceptive counseling on community college campuses could help facilitate access to more-effective contraception for a young adult population that often has no usual source of care or is uninsured.

Publicly funded family planning providers also could improve outreach to community college students to let them know of low-cost family planning services available in their communities. In addition, the possibility of moving oral contraceptives over the counter (OTC) may be particularly beneficial to this population that is uninsured and interested in short-acting hormonal methods, provided that OTC pills are made available at an accessible price.45

Limitations

A limitation of our study is a response rate of 37%, though it is higher than other health-related studies with community college students using online or mail recruitment.14–16 Although we found no statistically significant differences in age or ethnicity between respondents and non-respondents in the college sample for which we had that information, we were not able to compare sexually active women in those groups. In our logistic regression models predicting preference for and use of a more-effective method, some confidence intervals for the adjusted odds ratios of more-effective method use given a preference are relatively large. Therefore, we interpret our findings as evidence of differences in odds but do not draw conclusions about the magnitude of those differences. Also, we only offered the survey in English, the language of instruction at the colleges, and it is possible that students whose first language is Spanish may have opted out of taking the survey at higher rates than those whose first language is English. On the other hand, this sample provides a geographically diverse description of young community college students’ experiences in Texas, suggesting unmet demand for more-effective contraception is a widespread problem.

Conclusions

This study is the first investigation of contraceptive preferences among low-income women in a community college setting. We found high levels of preference for more-effective methods in this population, but we also found evidence of substantial barriers to realizing those preferences. Our findings indicate that increasing access to more-effective methods of contraception through improved health insurance coverage and low-cost contraception as well as providing students with information about pregnancy prevention and connecting them with health care providers who provide the full range of contraceptive methods could increase the use of more-effective methods and, by extension, decrease unintended pregnancy among this population.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Fu-An Lin, Lina Palomares, and Edward Leach for their contributions to the research. Earlier versions of the paper were presented at the annual meetings of the Population Association of America, April 1, 2016, Washington, DC and the National Institute for Staff and Organizational Development, May 30, 2016, Austin, TX. This work was supported by the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation (grant number 3862). Infrastructural support was provided by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R24 042849) to the Population Research Center, University of Texas at Austin. Funders of the Texas Policy Evaluation Project have no role in the design and conduct of the research, interpretation of the data, approval of the final manuscript or decision to publish.

Funding

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2CHD042849), Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation (3862).

Footnotes

Analyses that included the Houston participants yielded similar results as those presented here.

References

- 1.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Curtin SC, Matthews TJ. Births: final data for 2013 2015;64 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr64/nvsr64_01.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med 2016;374(9):843–852. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1506575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindberg L, Santelli J, Desai S. Understanding the decline in adolescent fertility in the United States, 2007–2012. J Adolesc Health August 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Pazol K, Daniels K, Romero L, Warner L, Barfield W. Trends in long-acting reversible contraception use in adolescents and young adults: New estimates accounting for sexual experience. J Adolesc Health 2016;59(4):438–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibbs SE, Rocca CH, Bednarek P, Thompson KMJ, Darney PD, Harper CC. Long-acting reversible contraception counseling and use for older adolescents and nulliparous women. J Adolesc Health 2016;59(6):703–709. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trieu SL, Bratton S, Hopp Marshak H. Sexual and reproductive health behaviors of California community college students. J Am Coll Health 2011;59(8):744–750. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.540764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Association of Community Colleges. American Association of Community Colleges 2016 Fact Sheet February 2016. http://www.aacc.nche.edu/AboutCC/Documents/AACCFactSheetsR2.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2016.

- 8.Pokhrel P, Little MA, Herzog TA. Current methods in health behavior research among U.S. community college students a review of the literature. Eval Health Prof 2014;37(2):178–202. doi: 10.1177/0163278713512125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American College Health Association. American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II: Undergraduate Student Reference Group Executive Summary Spring 2015 Hanover, MD: American College Health Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Briefly…what Community Colleges Can Do to Reduce Unplanned Pregnancy and Improve Completion; 2012. http://www.achievingthedream.org/sites/default/files/resources/unplanned_pregnancy_what_community_colleges_can_do.pdf.

- 11.Birnholtz JP, Horn DB, Finholt TA, Bae SJ. The effects of cash, electronic, and paper gift certificates as respondent incentives for a web-based survey of technologically sophisticated respondents. Soc Sci Comput Rev 2004;22(3):355–362. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Messer BL, Dillman DA. Surveying the general public over the Internet using address-based sampling and mail contact procedures. Public Opin Q 2011;75(3):429–457. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Millar MM, Dillman DA. Improving response to web and mixed-mode surveys. Public Opin Q 2011;75(2):249–269. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fish C, others. Health promotion needs of students in a college environment. Public Health Nurs 1996;13(2):104–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berg CJ, An LC, Thomas JL, et al. Smoking patterns, attitudes and motives: unique characteristics among 2-year versus 4-year college students. Health Educ Res 2011;26(4):614–623. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.VanKim NA, Laska MN, Ehlinger E, Lust K, Story M. Understanding young adult physical activity, alcohol and tobacco use in community colleges and 4-year post-secondary institutions: A cross-sectional analysis of epidemiological surveillance data. BMC Public Health 2010;10(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall KS, Trussell J, Schwarz EB. Progestin-only contraceptive pill use among women in the United States. Contraception 2012;86(6):653–658. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilliam ML, Warden MM, Tapia B. Young Latinas recall contraceptive use before and after pregnancy: a focus group study. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2004;17(4):279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson EK, Samandari G, Koo HP, Tucker C. Adolescent mothers’ postpartum contraceptive use: a qualitative study. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2011;43(4):230–237. doi: 10.1363/4323011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lemay CA, Cashman SB, Elfenbein DS, Felice ME. Adolescent Mothers’ Attitudes toward Contraceptive Use before and after Pregnancy. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2007;20(4):233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Upadhyay UD, Raifman S, Raine-Bennett T. Effects of relationship context on contraceptive use among young women. Contraception 2016;94(1):68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sweeney MM. The reproductive context of cohabitation in the United States: recent change and variation in contraceptive use. J Marriage Fam 2010;72(5):1155–1170. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00756.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Department of Health and Human Services. 2014 Poverty Guidelines 2014. http://aspe.hhs.gov/2014-poverty-guidelines.

- 24.Potter JE, Hopkins K, Aiken ARA, et al. Unmet demand for highly effective postpartum contraception in Texas. Contraception 2014;90(5):488–495. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Potter JE, Hubert C, Stevenson AJ, et al. Barriers to postpartum contraception in Texas and pregnancy within 2 years of delivery: Obstet Gynecol 2016;127(2):289–296. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potter JE, Coleman-Minahan K, White K, et al. Contraception after delivery among publicly insured women in Texas. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130(2):393–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hopkins K, White K, Linkin F, Hubert C, Grossman D, Potter JE. Women’s experiences seeking affordable family planning services in Texas. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2015;47(2):63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Secura GM, Allsworth JE, Madden T, Mullersman JL, Peipert JF. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project: Reducing Barriers to Long-Acting Reversible Contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;203(2):115.e1–115.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med 2012;366(21):1998–2007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harper CC, Rocca CH, Thompson KM, et al. Reductions in pregnancy rates in the USA with long-acting reversible contraception: a cluster randomised trial. The Lancet 2015;386(9993):562–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ricketts S, Klingler G, Schwalberg R. Game change in Colorado: widespread use of long-acting reversible contraceptives and rapid decline in births among young, low-income women. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2014;46(3):125–132. doi: 10.1363/46e1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Culwell KR, Feinglass J. The association of health insurance with use of prescription contraceptives. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2007;39(4):226–230. doi: 10.1363/3922607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stevenson AJ, Flores-Vazquez IM, Allgeyer RL, Schenkkan P, Potter JE. Effect of removal of Planned Parenthood from the Texas Women’s Health Program. N Engl J Med 2016;374(9):853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1511902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White K, Hopkins K, Aiken ARA, et al. The impact of reproductive health legislation on family planning clinic services in Texas. Am J Public Health 2015;105(5):851–858. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frost JJ, Gold RB, Bucek A. Specialized Family Planning Clinics in the United States: Why Women Choose Them and Their Role in Meeting Women’s Health Care Needs. Womens Health Issues 2012;22(6):e519–e525. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luchowski AT, Anderson BL, Power ML, Raglan GB, Espey E, Schulkin J. Obstetrician-gynecologists and contraception: long-acting reversible contraception practices and education. Contraception 2014;89(6):578–583. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaaler ML, Kalanges LK, Fonseca VP, Castrucci BC. Urban-rural differences in attitudes and practices toward long-acting reversible contraceptives among family planning providers in Texas. Womens Health Issues 2012;22(2):e157–62. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teal SB, Romer SE. Awareness of long-acting reversible contraception among teens and young adults. J Adolesc Health 2013;52(4):S35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dehlendorf C, Park SY, Emeremni CA, Comer D, Vincett K, Borrero S. Racial/ethnic disparities in contraceptive use: variation by age and women’s reproductive experiences. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;210(6):526.e1–526.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sundstrom B, Baker-Whitcomb A, DeMaria AL. A qualitative analysis of long-acting reversible contraception. Matern Child Health J 2014;19(7):1507–1514. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1655-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zerden ML, Tang JH, Stuart GS, Norton DR, Verbiest SB, Brody S. Barriers to receiving long-acting reversible contraception in the postpartum period. Womens Health Issues 2015;25(6):616–621. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Potter JE, Hubert C, White K. The availability and use of postpartum LARC in Mexico and among Hispanics in the United States. Matern Child Health J August 2016:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2179-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.National Center for Health Statistics. Trends in Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Use among U.S. Women Aged 15–44; 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db188.pdf. [PubMed]

- 44.National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Webinar: Addressing unplanned pregnancy at public colleges September 2017.

- 45.Grossman D, Grindlay K, Li R, Potter JE, Trussell J, Blanchard K. Interest in over-the-counter access to oral contraception among women in the United States. Contraception 2013;88(4):544–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]