Abstract

Histoplasmosis is a worldwide-distributed deep mycosis that affects healthy and immunocompromised hosts. Severe and disseminated disease is especially common in HIV-infected patients. At least 11 phylogenetic species are recognized and the majority of diversity is found in Latin America. The northeastern region of Brazil has one of the highest HIV/AIDS prevalence in Latin America and Ceará State has one of the highest death rates due to histoplasmosis in the world, where the mortality rate varies between 33–42%. The phylogenetic distribution and population genetic structure of 51 clinical isolates from Northeast Brazil was studied. For that morphological characteristics, exoantigens profile, and fungal mating types were evaluated. The genotypes were deduced by a MSLT in order to define local population structure of this fungal pathogen. In addition, the relationships of H. capsulatum genotypes with clinically relevant phenotypes and clinical aspects were investigated. The results suggest two cryptic species, herein named population Northeast BR1 and population Northeast BR2. These populations are recombining, exhibit a high level of haplotype diversity, and contain different ratios of mating types MAT1-1 and MAT1-2. However, differences in phenotypes or clinical aspects were not observed within these new cryptic species. A HIV patient can be co-infected by two or more genotypes from Northeast BR1 and/or Northeast BR2, which may have significant impact on disease progression due to the impaired immune response. We hypothesize that co-infections could be the result of multiple exposure events and may indicate higher risk of disseminated histoplasmosis, especially in HIV infected patients.

Subject terms: Fungal evolution, Fungal infection

Introduction

Histoplasmosis is a worldwide-distributed systemic mycosis caused by several cryptic species nested within the Histoplasma capsulatum complex1. H. capsulatum has a dimorphic life cycle; the mycelial phase (MP) develops in an environmental milieu with high concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus, humidity above 60%, darkness, and near watercourses2. Upon inhalation of microconidia or macroconidia from Histoplasma spp. by susceptible hosts, the fungus differentiates into the yeast phase (YP), composed by budding yeast cells. Both MP and YP can be obtained by in vitro cultivation of the fungus at 25–28 °C and 34–37 °C, respectively. Histoplasma infections have been reported on all continents with exception of Antarctica1. The course of histoplasmosis varies from asymptomatic infection to mild-to-severe disease. High incidence of human Histoplasma infection has been reported mainly in tropical and subtropical areas of the Americas. However, the true disease range is likely larger, as this mycosis has also been found in Canada and in the Patagonia desert in Argentina3,4.

This pathogen can cause disease in different animal hosts, such as bats, domestic cats, and several wild mammals2,4,5. In humans, histoplasmosis outbreaks have been described in immunocompetent individuals linked to activities such as visiting caves and archeological sites, or working on a construction site. These exposures are often associated with environments containing high levels of bat or bird guano, which may favor the development of MP that harbors infectious microconidia6.

In last years, an increase of disseminated histoplasmosis has been reported, mainly associated with AIDS-patients throughout the Americas7,8. A major challenge is that mortality rate, presence of skin and mucosal lesions, and relapse frequency of these infections vary in individuals from distinct geographic areas of the disease9,10. In addition, experimental studies have demonstrated that variation in virulence may be associated with different genetic lineages of H. capsulatum11.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) is the main molecular tool currently used to evaluate genetic diversity at the species level of H. capsulatum12. The first analysis of isolates across the global distribution of the species defined 8 phylogenetic clades13,14. The LAm A and LAm B clades harbor isolates primarily from Latin America; the Nam 1 and Nam 2 clades from North America; the Eurasian clade from Egypt, India, China, Thailand, and England; the Netherlands clade; the Africa clade; and the Australian clade14. Recently, a more robust MLST study evaluating 234 isolates of H. capsulatum lead to the identification of at least 11 species-level clades, the majority of them found in Latin America. The former LAm A and LAm B species were divided into four different genetic clusters as follows: LAm A1, LAm A2, LAm B1 and LAm B2. Two new phylogenetic species, RJ (Southeast of Brazil) and BAC-1 (Mexico), and four different monophyletic and cryptic clades from Brazil (BR1-4) were also identified1.

Brazil presents one of the highest global incidences of histoplasmosis, and also presents the greatest genetic variability of Histoplasma and could be considered the center of origin of this important pathogen1,15. It is estimated that 2.19 individuals had a histoplasmosis diagnosis per 1,000 hospitalizations in Brazil16. However, the true incidence of this mycosis in Brazil is unknown, especially because it is not a notifiable disease.

Studies performed by histoplasmin skin-test between 1940 and 1990 have found different levels of prevalence of histoplasmosis in Brazil17. A prevalence rate of 93.2% was observed in southeastern Brazil17,18. In Ceará, a state located in the northeastern of Brazil, the prevalence rates varied from 23.6% to 61.5% among residents in rural areas19,20. Among HIV-positive individuals from Ceará without severe immunosuppression (lymphocyte T CD4+ >350 cells/mm3), the histoplasmosis prevalence reached 11.8%21. In the last three decades, the Ceará State has presented a large number of cases of disseminated histoplasmosis (DH) described mainly in AIDS-patients9. Between 1995 and 2004, 164 cases of co-infection of DH and AIDS were observed in a single hospital22. Moreover, 134 cases of the disease were found during a 7 year medical surveillance23; 208 cases in another 5 years8 and, more recently, 264 new cases in 7 years9 in this single state. These studies clearly demonstrate that northeastern Brazil, particularly Ceará State, is a highly endemic area of histoplasmosis, and is associated with a high annual death rate among HIV patients24. In Fortaleza (the capital of Ceará State), many cases of histoplasmosis are associated with low sanitation capacity, ecotourism, and fishing25.

Although antiretroviral therapy has modified the course of AIDS, a mortality rate between 33–42% associated with histoplasmosis has been observed in this region of Brazil8,9, unlike other endemic regions such as Panama (12.5%)26 and French Guiana (8%)24,27. The genetic background of Histoplasma in northeastern Brazil is poorly explored, especially considering the high mortality rates of DH so far reported for this particular area.

The aim of this study was to assemble the epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory data of histoplasmosis patients diagnosed in Ceará, Northeastern of Brazil. The phenotypes of clinical strains such as morphological characteristics, exoantigen profiles, and fungal mating types were evaluated. The genotypes of clinical isolates of H. capsulatum obtained from patients were deduced by a MSLT in order to define local population structure of this fungal pathogen. In addition, the relationships of H. capsulatum genotypes with clinically relevant phenotypes and clinical aspects were investigated. Finally, it was demonstrated the occurrence of recurrent infections by multiple genotypes of H. capsulatum in HIV patients.

Results

Clinical data

Relevant clinical data were evaluated in 43 hospitalizations of 40 individuals with DH from 2011 to 2014 (Table 1). Thirty-one cases occurred in males and nine in females. Patient’s age varied from 19 to 56 years old (median 31 years; interquartile range: 28–39 years). Only a single patient was HIV-negative. Hospitalizations were more frequent in individuals living in the metropolitan area of Fortaleza (75%). Other Ceará regions, such as the central wilderness, mountain region, and east coast, had smaller number of histoplasmosis cases (Table S1). All patients received amphotericin B deoxycholate (1 mg/Kg/day) until the clinical improvement, followed by itraconazole (400 mg/day). Co-infections with tuberculosis were detected in 15% of the cases. Fever, cough, and dyspnea were the most common clinical manifestations observed in the herein described patients (Table 1). Data revealed a high mortality ratio among the AIDS-patients (33%) included in this study. Moreover, presence of skin lesions (p = 0.003) and acute renal failure (p = 0.010) were risk factors associated with deaths.

Table 1.

Baseline measurements of the histoplasmosis cases (n = 40) evaluated in the São José Hospital from Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil, between 2011 to 2014.

| Epidemiological data | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Man | 31 (77.5%) |

| Woman | 9 (22.5%) |

| Origin | |

| Fortaleza, Ceará | 23 (57.5%) |

| Other cities of Ceará | 17 (42.5%) |

| HIV/AIDS test | |

| Positive | 39 (97.5%) |

| Negative | 1 (2.5%) |

| Drug addictive | |

| Yes | 6 (15.0%) |

| No | 34 (85.0%) |

| Co-infection with tuberculosis | |

| Positive | 6 (15.0%) |

| Negative | 34 (85.0%) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Fever | 40 (100%) |

| Weight loss | 33 (82.5%) |

| Cough | 27 (67.5%) |

| Dyspnea | 27 (67.5%) |

| Hepatomegaly | 26 (65%) |

| Diarrhea | 25 (62.5%) |

| Asthenia | 22 (55%) |

| Spleenomegaly | 20 (50%) |

| Vomit | 18 (45%) |

| Abdominal pain | 12 (30%) |

| Headache | 11 (27.5%) |

| Mucosa hemorrhage | 10 (25%) |

| Skin lesion | 09 (22%) |

| Adenomegaly | 08 (20%) |

| Acute renal failure | 06 (15%) |

Macro and micromorphological characteristics of MP

Fifty-one clinical fungal isolates were obtained from the included patients. Fungi were isolated from buffy coat (n = 30), blood (n = 14), bone marrow (n = 6), and bronchoalveolar lavage (n = 1) (Table S1). The overall morphological characteristics of the H. capsulatum isolates are reported in Table S2, where differences in colony texture, color, and micromorphologies were recorded. The surface of H. capsulatum colonies varied from pale (white to beige) (36/51–70.6%) to dark (brown) (15/51–29.4%) and the texture of colonies ranged from cottony (42/51–82.4%) to powdery (9/51–17.6%). Microconidia were observed in all isolates while macroconidia were identified in 74.5% (38/51) of H. capsulatum isolates. There was no association between texture and presence of tuberculate macroconidia, as the majority of cottony (30/42–71.4%) and powdery colonies (8/9–89%) produced tuberculate macroconidia (p = 0.417).

Dimorphism

The MP-YP conversion occurred in 88.2% (45/51) of H. capsulatum isolates in the first cultivation on ML-Gema Agar between 7 to 14 days. Five isolates (9.8%) presented a delayed MP-YP conversion, since the dimorphic switch took place after 3 or 4 sub-cultivations at the same conditions. Just one isolate (CE 0613) did not convert from MP to YP (2%) under the studied conditions (Table S2). All YP colonies presented smooth and moist texture, and showed characteristic oval-shaped yeast cells ranging from 2 to 5 µm in size.

Exoantigen profiles

ID tests revealed that 17.6% of H. capsulatum exoantigens (9/51) yielded precipitin bands. Eight fungal isolates had single M band, and only one isolate had both H and M precipitin bands. By using Western blot, a more sensitive technique, the exoantigens were detected in all fungal isolates (Table S2). Both H and M antigens were observed in 29 (54.9%) isolates; 18 (35.2%) had single M band (corresponding to a 94 kDa protein), and 4 (7.9%) isolates just presented the H antigen (corresponding to a 114 kDa protein). There was no association between isolates that produced the both H and M antigens with texture (p = 0.268) or pigmentation (p = 0.167) of colonies, as well as with the presence or absence of macroconidia (p = 0.106).

Phylogenetic distribution, population structure, and clinical/phenotype correlation

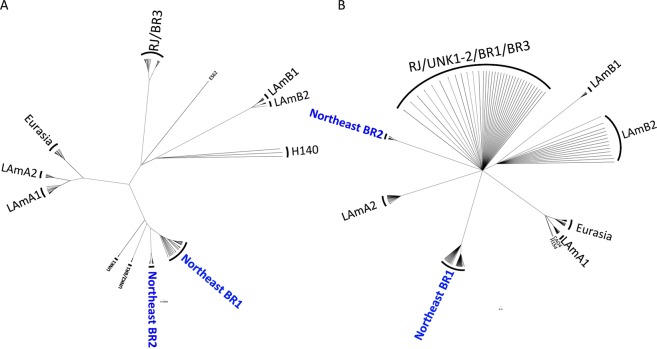

Phylogenetic analysis revealed two new clades within Latin America, comprised mainly of the H. capsulatum isolates recovered from HIV-infected patients, named the Northeast clade BR1 and Northeast clade BR2 (Fig. 1). Both clades appear to be monophyletic using both maximum likelihood (ML) (Fig. 1A) and Bayesian inference (BI) methods (Fig. 1B). According to Teixeira et al.1, the strains from BR2 clade (84476, 84502, 84564, H151, and JIEF) and BR4 clade (H146, RE5646, and RE9463) nested within the herein proposed Northeast BR1 and Northeast BR2 populations, respectively. For that study, those clades were not classified as phylogenetic species due to the low taxon sampling (1). Therefore, the clades found in the Northeast region of Brazil were renamed in order to clarify nomenclature, Northeast clade BR1 and Northeast clade BR2. According to both ML and BI unrooted trees, the Northeast BR1 and BR2 clades are monophyletic; however, they have low bootstrap and posterior probability values (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic distribution of the isolates from Northeast Brazil. Two cryptic clades Northeast BR1 and Northeast BR2 are revealed. Unrooted trees were generated by (A) Maximum Likelihood and (B) Bayesian analysis using K2P+ Inv Gamma DNA substitution model. Brach supports are proportion to the thickness of each branch.

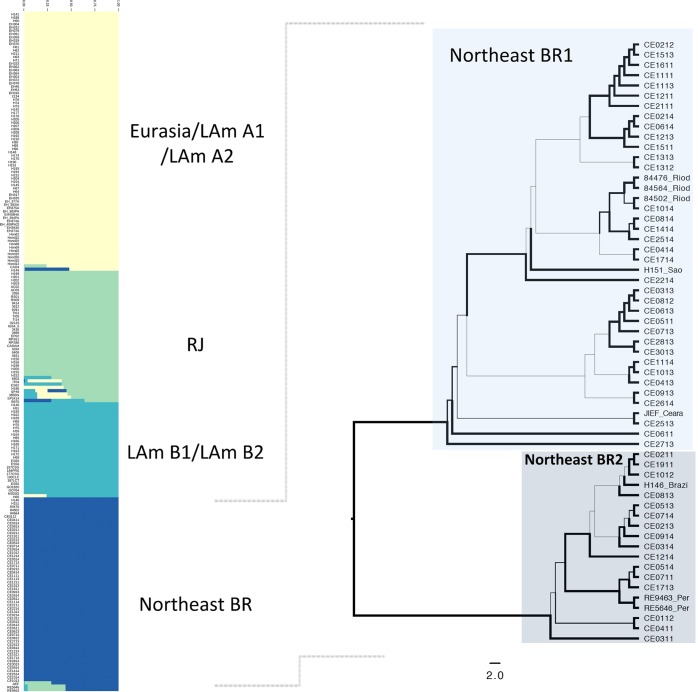

Initially, the whole population structure of Latin American (former LAm A, LAm B and Eurasia clades)1 was assessed via Bayesian Analysis of Population Structure using a Kmax value of 50. Initial admixture analysis revealed at least four clusters: Eurasia/LAm A1/LAm A2, RJ, LAm B1/LAm B2, and a fourth population composed mainly of isolates from the northeastern Brazil confirming the monophyly achieved in the phylogenetic analyses (Fig. 2). Gene flow between the RJ and Northeast BR1 and BR2 populations was noted, as the isolates JIEF, RE9463, and RE5646 share alleles from both populations (Fig. 2). Allele exchange has been extensively reported in the former LAm A clade, which is compatible with a sexually recombining species. Recombination analysis for the Northeast population was positive (p = 2.345 × 10−12) using the PHI-test analysis, and a cluster network analysis demonstrated gene flow between isolates within this population (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 2.

Population distribution of H. capsulatum in Latin America. (A) Admixture plots revealed a cryptic H. capsulatum population (green) harboring isolates from Northeast Brazil. Gene flow between Latin American populations is evidenced by admixed plots in RJ, LAm B and Northeast populations. (B) Phylogenetic analysis using the Maximum Likelihood methods of the Northeast population revealed two cryptic species Northeast1 and Northeast 2.

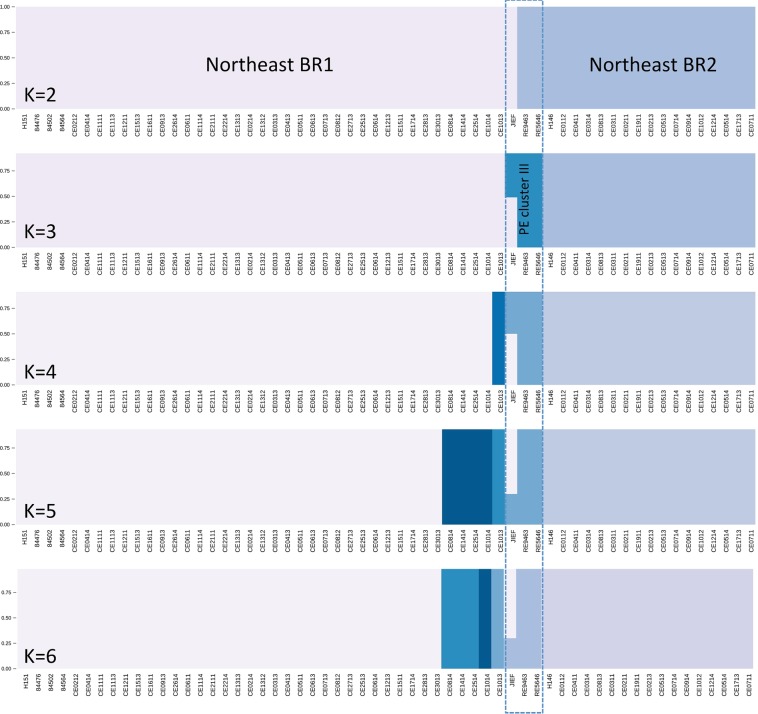

A deep investigation of the phylogenetic and population distribution of the 59 strains [51 from the present study and eight from Teixeira et al.1] belonging to the Histoplasma Northeast populations showed two monophyletic clades strongly supported by bootstrap values as represented by the ML tree (Fig. 2). Admixture analysis using a fixed K model revealed an optimal partition of K = 3: Northeast BR1, Northeast BR2, and a third population composed of two isolates (RE9463 and RE5646) from Pernambuco State, Brazil (a state that borders Ceará) and a third isolate (JIEF) from Ceará shares alleles with Northeast BR1 population and is likely a hybrid strain (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Sub-population distribution of Northeast isolates. Admixtures plots show the percentage of alleles unique or shares between Northeast BR1 and Northeast BR2 populations. At least three populations where found within Northeast isolates: The previous phylogenetic proposed Northeast BR1 and Northeast BR2 and an additional one composed by isolates of the neighbor state of Pernambuco, Brazil.

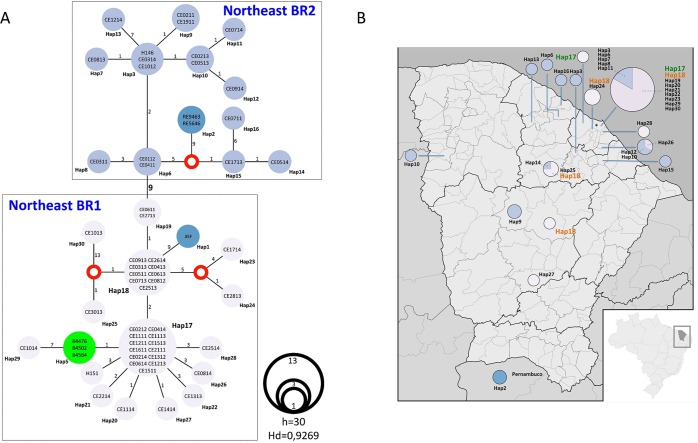

Haplotype networks revealed that the two Northeast populations are highly diverse (Fig. 4A). The haplotype diversity index for these populations is comparable to the highly recombinant RJ population (Hd = 0.9269)1. At least 30 haplotypes were observed within the subset of 59 isolates from northeastern Brazil (Fig. 4A). Northeast BR1 and Northeast BR2 are separated by nine mutations that are fixed in each population. The isolates RE9463 and RE5646 from Pernambuco form a unique haplotype (Hap2) derived from a median vector from a population Northeast BR2 (Fig. 4A). The isolates 84476, 84502, and 84564 were isolated in Rio de Janeiro in 1998 and represent cases diagnosed outside northeastern of Brazil belonging to Northeast BR1. Importantly, the population Northeast BR2 is widely spread across Ceará state while the Northeast BR1 is more restricted to the metropolitan area of the capital Fortaleza (Fig. 4B). This is evident as haplotypes 17 and 18 and their derivations (Hap19-23, Hap29, and Hap30) are clustered in Fortaleza and adjacent regions. Finally, it was observed that haplotype 18 is widely distributed in at least four municipalities and may represent a broadly distributed genotype (Fig. 4B). Associations between Northeast BR1 and Northeast BR2 populations and clinical manifestations such as dyspnea, mucosa hemorrhage, skin lesion, acute renal failure, and deaths were not observed (p > 0.05). Additionally, relationships between the genetic populations and their phenotypes were not detected either (Table 2, Supplementary Fig. S2). However, there was a slightly predominance of MAT1-1 (68.7%) in Northeast BR2 and MAT1-2 (62.9%) in Northeast BR1 (p = 0.036 – Table 2).

Figure 4.

Haplotype network analysis using the Median-Joining method. (A) The haplotypes are proportional to the number of individuals and the number of mutations between each haplotype is displayed to each correspondent vertices. We identified 2 main population correspondent to Northeast BR1 and Northeast BR2 genotypes. (B) The haplotypes were plotted against each corresponding location in the map of Ceará state.

Table 2.

Associations between phenotype and genotype of H. capsulatum isolates from Ceará, Brazil.

| Phenotype | BR1 genotype | BR2 genotype | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Color | |||

| Pale | 25 (71.4%) | 11 (68.8%) | 0.846 |

| Dark | 10 (28.6%) | 5 (31.2%) | |

| Texture | |||

| Cotony | 30 (85.7%) | 12 (75%) | 0.352 |

| Powdery | 5 (14.3%) | 4 (25%) | |

| Micromorfology | |||

| Macroconidia+ | 26 (64.3%) | 12 (75%) | 0.957 |

| Macroconidia− | 9 (25.7%) | 4 (25%) | |

| Exoantigen | |||

| M antigen | 15 (42.8%) | 7 (43.8%) | 0.952 |

| M and H antigen | 20 (57.2%) | 9 (56.2%) | |

| Mating | |||

| MAT1-1 | 13 (37.1%) | 11 (68.8%) | 0.036 |

| MAT1-2 | 22 (62.9%) | 5 (31.2%) | |

Dual Histoplasma infections in HIV patients

Seven patients included in this study yielded more than one H. capsulatum strain for analysis (Table S2). The phenotypic analyses of these strains revealed one patient (number 17) that yielded three isolates (CE 0313, CE 0713, CE 1013) with pale colonies, and one with dark pigmentation (CE 2713). The textures of H. capsulatum colonies obtained from two patients were cottony in some isolates (CE 0313, CE 0713, and CE 1013 from patient 17; CE 0513, and CE 0814 from patient 19) and powdery in others (CE 2713 from patient 17 and CE 0914 from patient 19). Tuberculate macroconidia were present in all isolates recovered from patients 2, 22 and 28; however, three patients (1, 17, and 19) were infected with fungal isolates with and without tuberculate macroconidia. The macroconidia were not observed on the isolates CE 0614 and CE 1014 from patient number 33. Moreover, the H. capsulatum isolates recovered from patients 2, 17, 19, 28, and 33 expressed different exoantigen profiles under the same experimental conditions.

The genotypic analyses revealed that sequential isolates belonging to the same haplotype were recovered from two patients (1 and 22). It is noteworthy that isolates CE0211 and CE1911 from patient 1, comprising the haplotype 9 within the Northeast BR2 population (Fig. 4), are phenotypically distinct, since CE1911 did not produce macroconidia. On the other hand, isolates CE1113 and CE1513 recovered from patient 22 are identical by means of genotypic (haplotype 17, Northeast BR1 population) and phenotypic analyses (Supplementary Fig. S2).

For the other five patients, more than one genotype was recovered from successive isolations (Table 3). Patients 2 and 19 were infected by isolates from the Northeast BR1 population (CE0511 and CE 0814, respectively) and from the Northeast BR2 population (CE0112 and CE0311 from patient 2; CE0513 and CE0914, from patient 19), while three patients (17, 28, and 33) were infected by different haplotypes within the Northeast BR1 population (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Table 3.

Clinical and epidemiological features of patients infected with different genotypes of Histoplasma capsulatum.

| Patients | Sex | Age | Risk activity | Symptoms | CD4+ (cells/mm3) | HAART at admission | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 2 | Man | 22 | no | Dyspnea | 273 | No | Discharged |

| Patient 17 | Man | 38 | no | Dyspnea | Not performed | No | Discharged |

| Patient 19 | Man | 31 | yes | Dyspnea | 36 | No | Discharged |

| Patient 28 | Man | 52 | yes | Dyspnea, renal failure, skin lesions, mucosa bleeding | Not performed | No | Death |

| Patient 33* | Man | 30 | yes | Dyspnea | 117 | Poor adhesion | Discharged |

*This individual was re-hospitalized with histoplasmosis and severe immunodeficiency (CD4+ 29 cells/mm3).

Of five patients affected with dual infection, all individuals were men, with average age of 34.6 years. Three patients had risk activity for histoplasmosis. Dyspnea was observed in all patients, and only one patient had skin lesions, mucosa bleeding and renal failure (patient 28). The first opportunistic infection in 4 among these 5 patients was histoplasmosis ou disseminated histoplasmosis was AIDS defining illness in 4 among these 5 patients. Only one patient had AIDS before this mycosis (patient 33), and this individual had irregular adhesion to HAART. One patient had tuberculosis co-infection (patient 2). Four patients had discharged and one died. Mortality of patients harboring different genotypes was similar to those infected with a single genotype (p = 1.000).

Three patients were re-hospitalized with the new hospitalization one to five months apart the first: patient 17 yielded four isolates with different phenotypic characteristics (Supplementary Figure 2) but all of them belonging to three distinct haplotypes from the Northeast BR1 population; patient 19 yielded three isolates from three different haplotypes, interestingly the two isolates from the first hospitalization (CE0513 and CE0914) were from the Northeast BR2 population and the isolate from the second hospitalization (CE0814) was from the Northeast BR1 population; finally patient 33 was infected by isolates with different haplotypes and mating types (CE0614 – Hap17, MAT1-1; CE1014 – Hap29, MAT1-2, from first and second hospitalizations, respectively), but both belonging to the Northeast BR1 population (Supplementary Figs S2 and S3).

Discussion

Histoplasmosis has been considered an AIDS defining illness since 198728, and a disease responsible for thousands of deaths in Latin America among people living with HIV/AIDS. The Ceará state, Northeastern Brazil, is considered the area with the highest mortality due to histoplasmosis in South America8,9,24, far surpassing rates in other endemic areas, such as Panama26 and French Guiana24,27. Thirty-one cases occurred in males and nine in females. These data has been previously demonstrated by Damasceno and collaborators (2013)9 where the majority of the subjects included in their studies were male with a mean age of 35 years (SD = 2.2; 95% CI = 3.01–3.75) and were born in the capital of Ceará. A lack of early diagnosis for the disease contributes to the high rates of mortality. The high mortality rate observed in this study, which unfortunately is expected for this disease among immunocompromised patients at this area, is in accordance with other studies conducted at Ceará, Brazil.

Currently, H. capsulatum is thought to be a complex of different species, containing at least 11 phylogenetic species and/or cryptic lineages1. Latin America presents higher diversity than other endemic areas, and diversity is highest in Brazil1,29. Additionally, the majority of H. capsulatum Brazilian clinical isolates previously studied were obtained from residents of southeastern Brazil1,14.

Fungal infections may contain multiple genotypes of the same pathogen, but still are usually considered as uniform entities. For the first time, we show strong support for two new populations, Northeast BR1 and Northeast BR2 that could cause mixed infections in HIV-positive individuals. The co-infection concept in virology is characterized by patients infected with two different virus strains simultaneously. On the other hand, the superinfection concept represents a condition in which an individual with established viral infection acquires a secondary infection provoked by a second genotype and this phenomenon is widely studied in viruses30. Similar event was observed in this research. Possibly, there were two different exposure events in the patients that presented different genotypes. Another explanation is that different genotypes share similar ecologic niches. Further studies are necessary to address these issues.

In bacteriology, this concept is slightly different; a secondary infection overcomes the earlier one caused by a different species and may be resistant to primary antibacterial treatment. Either way, mixed infections of Mycobacterium tuberculosis also have shown effects on both treatment and disease control31. Multiple infections due Cryptococcus neoformans32 and Pneumocystis jirovecii33 were also reported on HIV patients, however the incubation periods of fungal, bacterial and viral infections varies and whether the herein reported mixed infections are either co-infection or superinfections must be deeply revised in the medical mycology field.

Different genotypes may display divergent host cell tropism, immunologic evasion, or even antifungal-drug resistance, which is critical for patients with disseminated histoplasmosis and other endemic mycosis34. Thus, heterogeneous H. capsulatum infections may have significant consequences for immunologic escape and histoplasmosis progression. The competence of a previously cleared or ongoing Histoplasma infection to protect against a subsequent infection by a novel Histoplasma genotype may decrease the ability of the adaptive immune response to provide adequate and broad protection. The immunity induced by a prior Histoplasma infection could be insufficient to prevent a new infection. This directly challenges our current understanding of protective immunity, and impacts the development of vaccines for histoplasmosis and other endemic fungal pathogens in certain patient populations.

The genotyped isolates from Northeastern Brazil are contained in the previously delineated BR2 clade and BR4 clade respectively (Figs 1–4)1. The BR2 and BR4 clades were not previously ranked as phylogenetic species due to the low taxon sampling. However, we herein propose to elevate the status of “cryptic clades” to phylogenetic species of the former BR2 and BR4 (Fig. 1). The newly described Histoplasma Northeast BR1 and Northeast BR2 clades are monophyletic in both phylogenetic methods evaluated. However low bootstrap support for these monophyletic braches, likely due to homoplasy, were detected in both species so it is clear that more in depth analyses, such as whole genome sequencing, would resolve this question. Phylogenetic methods were coupled with population genetics analysis and it was identified the same population structure for the Northeast BR1 and Northeast BR2 clades mentioned above (Figs 2 and 3). Moreover, further investigation may reveal new populations in Northeast Brazil as evidenced by an isolated population of H. capsulatum in the Pernambuco state of Brazil (Fig. 3).

Additionally, this is the first study that evaluates the relationships between genotypes with clinical and phenotypic aspects of H. capsulatum isolates. It is known that DH can present with differential clinical characteristics in individuals from different endemic areas. For example, skin lesions and deaths are more frequent in individuals from Brazil than in patients from North America10. These differences may be related to different circulating genotypes on these two regions but also by phenotypic traits of the strains, such as different tolerances to cooler temperatures found in the skin. In fact the development and progression of histoplasmosis it is very sophisticated and depend of differences in fungal burden, disease kinetics, cytokine responses, and many virulence factors. Experimental studies have also found differences in the virulence of the pathogen, gene expression, and pathogenesis of disease between H. capsulatum from different phylogenetic clades35–37. Despite this, associations between genetic populations and phenotypic features were not detected (Table 2). Neither morphology nor exoantigen profile were associated with population/species, revealing that the phenotypic plasticity of those isolates is a process independent of speciation/population subdivision, and more likely due to intrinsic variation38,39.

Mixed mating types were identified with a slight predominance of one mating type in each group. Consequently, we hypothesize that both Northeast BR1 and Northeast BR2 are sexually recombining populations as evidenced by recombination analysis (phi-test), recombination networks, homoplasy, and admixture profiles (Figs 1, 3 and S1). Sexual reproduction can increase genetic diversity and may have consequences for pathogenesis by creating progeny with novel traits such as the ability to evade the host immune responses, a greater resistance to antifungal drugs, biofilm formation, or hyper virulence40. Thus, recombination events can facilitate shifts in lifestyles, which can persist in successive successful lineages41. In Toxoplasma gondii, mating crosses between type II and III virulent strains revealed that the recombinant f1 progeny had a virulence increased by 1,000-fold in a mice model42. More studies are necessary to characterize the impact of natural variation found within H. capsulatum populations and its influence on virulence and pathogenesis. Additionally, it was demonstrated that a single patient (patient #17) was infected by different mating types from the same phylogenetic species (Northeast BR1). We hypothesize that co-infections could be the result of multiple exposure events and may indicate higher risk of disseminated histoplasmosis, especially in HIV infected patients.

In summary, H. capsulatum clinical isolates from Ceará are genetically distinct from isolates from southern Brazil and Latin America, which demonstrates the high genetic diversity this pathogen. It is unclear how this relates to variation in phenotypes, and additional investigation is greatly needed in this area, such as a GWAS approach.

Methods

Histoplasmosis patients

The study was approved in the Research Ethical Committee of INI/FIOCRUZ (protocol number 19342513.2.0000.5262) and it is in accordance with the suggestions of the Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine, UNAM (protocol number 057–2014). Forty patients hospitalized at São José Hospital from Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil, from 2011 to 2014 were included in this study. All patients had proven histoplasmosis by the isolation of H. capsulatum from clinical samples cultures. A retrospective study was conducted by reviewing medical records including epidemiological (sex, age, origin, occupational risk of histoplasmosis infection, drug addiction, and co-infection with tuberculosis), clinical (fever, weight loss, cough, dyspnea, hepatomegaly, diarrhea, asthenia, splenomegaly, vomit, abdominal pain, headache, mucosa hemorrhage, skin lesion, adenomegaly, and acute renal failure - ARF), and laboratory data (HIV serological test). Patient data entries were anonymously handled with Epi-Info software, version 7.1.5 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Fungal isolates and DNA extraction

Fifty-one fungal isolates were obtained from the 40 patients seen at São José Hospital, located in Fortaleza (Ceará, Brazil), as mentioned above. Histoplasma colonies were isolated from diverse samples [blood, bone marrow, buffy coat and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL)] by in vitro culture. YP or MP cells were grown in Ham’s F12 broth at 37 °C and 25 °C for 3–5 days, respectively. A total of 500 µl of YP/MP liquid cultures were used for DNA extraction. Briefly, the cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed three times with distilled deionized water, and kept at −4 °C for DNA extraction as previously described43. DNA was quantified by spectrophotometry using the Epoch™ Multi-Volume Spectrophotometer System (Biotek Instruments, Inc., USA).

Phenotypic assays

Fungal isolates were maintained for 21 days on Potato Dextrose Agar plates (PDA – Difco, Detroit, MI, USA) at 25 °C in order to obtain the MP. Macromorphological features of H. capsulatum MP cultures, such as texture and color of colonies, were described. Micromorphological characteristics of MP were observed by optical microscopy (Zeiss PrimoStar, Oberkochen, Germany) by sampling 10 fields randomly with a magnification of 400X, after Lactophenol Cotton Blue (Fluka Analyted, France) staining. Dimorphism was demonstrated by MP-YP conversion in the ML-Gema Agar at 37 °C, for 7 to 14 days43.

Exoantigens were obtained from the 51 H. capsulatum isolates included in this study. Briefly, a fragment of 2–4 cm2 of H. capsulatum MP grown for 14 days on PDA slants was transferred to Erlenmeyer flasks containing 25 ml of Brain Heart Infusion broth (BHI - Difco, Detroit, MI, USA). Flasks were incubated at 25 °C in a gyratory shaker at 150 rpm for 7 days (New Brunswick Scientific, Edison, NJ). Thimerosal 1% was added in the seventh day to inactivate fungal cells, and the flasks were re-incubated overnight at 25 °C. Cultures were centrifuged at 1,050 × g for 10 min, and the supernatants were filtered through 0.45 µm pore size filter membranes (Nalgene Co., Rochester, NY). The pooled filtrate was concentrated to 50X in a Minicon Macrosolute B-15 Concentrator (Amicon Corp., Lexington, MA, USA)44. To evaluate the presence of the specific H and/or M antigens in the exoantigens from each H. capsulatum isolate, double immunodiffusion (ID) and western blot (WB) were performed. The ID assay was performed as previously described13. For the WB experiments, H. capsulatum exoantigens were initially separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), on 10% polyacrylamide resolving gels with a 4% polyacrylamide staking gel. The gels were then processed for WB according to the protocol previously established45 and revealed against a pool of sera from human patients with proven histoplasmosis.

Mating type identification

The MAT locus of the H. capsulatum isolates was identified by a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using previously described primers and reaction conditions46,47, where amplicons with 440 and 528 bp are expected after the amplification of H. capsulatum MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 loci, respectively. The G-217B (ATCC® Number: MYA-2455™) from USA (MAT1-1) and G-186A (ATCC® Number: 26029TM) from Panama (MAT1-2) reference strains were respectively used as controls for each mating type. Amplicons were resolved by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. The 100-bp DNA ladder was used as a molecular size marker.

Multi locus sequencing typing

Amplification of partial DNA sequences of four nuclear genes (arf, H-anti, ole1, and tub1) was performed according to the protocol described by Kasuga et al.13, with some modifications. The PCR reactions were achieved in a final volume of 25 µl, containing 200 µM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA, USA), 2 mM of MgCl2, 0.45 µM of each primer, 1.0 U of Taq DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs Inc., MA, USA), 1 X of Taq commercial buffer (New England BioLabs Inc., MA, USA) and 20 ng of each DNA template. The G-217B reference strain was used as positive control for the PCR reactions. PCR assays were performed in a Thermal iCycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) programmed as follows: (a) 3 min at 95 °C; (b) 32 cycles, consisting of 15 sec at 94 °C, 30 sec at 65 °C in the first cycle, which was subsequently reduced by 0.7 °C/cycle for next 12 cycles, and 1 min at 72 °C. The remaining 20 cycles, the annealing temperature was continued at 56 °C; (c) a final extension cycle of 5 min at 72 °C (touchdown PCR)48. Generated amplicons were then sequenced by Sanger method at the High-Throughput Genomics Center (University of Washington) and the sequences were deposited in the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) – (Table S3). The Asparagin Platform (http://asparagin.cenargen.embrapa.br/phph/) was used to analyze the electropherograms.

Phylogenetic analysis

The obtained sequences were first checked by BLASTn49 to evaluate the genetic similarity with other H. capsulatum sequences deposited at GenBank. The sequences were aligned using the ClustalW50 algorithm implemented in the Mega 6.0 software51. We included the same dataset evaluated by Teixeira et al.1 to compare to the entire diversity of the genus Histoplasma so far reported (Table S3). The combined matrix was analyzed through two phylogenetic methods. First, maximum likelihood (ML) trees were generated using the IQ-TREE program52 using the –m MODEL function that allowing an automatic best-fit model selection (ModelFinder – K2P+ Inv Gamma was used in all tested phylogenies). The ultrafast bootstrap (UFBoot) approximation described by Minh et al.53 was employed to test branch confidence. Second, Bayesian inference (BI) was conducted using the MrBayes ver. 3.2 software54. Bayesian analysis was performed through 300,000 generations and samples were collected every 100 generations using 4 independent Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) to compute the posterior probability density. Twenty-five percent of the initial samples were discarded as burn-in and the remaining samples were used to build the consensual Bayesian tree. The consensus tree obtained by both methods was visualized in FigTree v1.3.155.

Recombination and population structure analysis

Recombination within Northeast populations was accessed using pairwise homoplasy index, (PHI-test). Cluster network analysis was inferred using the software SplitsTree 456. Population distribution of Northeast H. capsulatum isolates was inferred using a Bayesian Analysis of Population Structure (BAPS)57. The haplotypic networks were inferred to visualize diversity both Northeast H. capsulatum populations. The distribution and diversity of haplotypes for the concatenated dataset was estimated using the software DnaSP, v 558, and Median-joining networks were built and visualized in Network, v 4, software (Fluxus Technology, Clare, Suffolk, England). We conducted mixture and admixture analysis setting K-max to 50 hypothetical populations within the former LamA, LAmB as well as the Eurasian clade. In addition, fixed K model analysis (K = 2–5) was used for mixture analysis in order to infer the population sub-structuring within the Northeast population. In the admixture analysis (K = 3), 200 interactions were used to infer the admixture coefficient. Fifty references individuals were assumed for each cluster and admixture analyses were repeated 10 times per individual.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out using the software STATA 11.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). A bivariate analysis was performed to evaluate clinical data, phenotypic aspects, and genetic populations, using the Chi-square or Fisher exact test, if any value in the cells of the contingency table was less than five. A significance level of 5% (α = 0.05) was applied in all tests.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Lisandra Serra Damasceno thanks the “Programa de Pós-graduação Stricto Sensu em Pesquisa Clínica em Doenças Infecciosas do Instituto Nacional de Infectologia Evandro Chagas”, FIOCRUZ and the scholarship No. 99999.002336/2014-06 provided by the “Programa Institucional de Bolsas de Doutorado Sanduíche no Exterior” from the “Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Capes)”, Brazil, which was realized in the Laboratorio de Inmunología de Hongos, Unidad de Micología, Departamento de Microbiología y Parasitología, Facultad de Medicina, UNAM, Mexico. RMZ-O was supported in part by CNPq [302796/2017-7] and FAPERJ [E-26/203.076/2016]. This research was also partially supported by a grant provided by “Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica-Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico” from UNAM [PAPIIT-DGAPA/UNAM, Reference Number-IN213515] as well for Bridget Barker Startup funding from Northern Arizona University. PRINT-FIOCRUZ-CAPES was responsible for payment for this publication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Rosely Maria Zancopé-Oliveira. Data curation: Lisandra Serra Damasceno, Jacó Ricarte Lima de Mesquita, Terezinha do Menino Jesus Silva Leitão. Formal analysis: Lisandra Serra Damasceno, Marcus de Melo Teixeira, Bridget Marie Barker, Rodrigo Almeida-Paes. Funding acquisition: Rosely Maria Zancopé-Oliveira, Maria Lucia Taylor. Investigation: Lisandra Serra Damasceno. Methodology: Lisandra Serra Damasceno, Marcus de Melo Teixeira, Marcos Abreu de Almeida, Mauro de Medeiros Muniz, Claudia Vera Pizzini, Jacó Ricarte Lima de Mesquita, Gabriela Rodríguez-Arellanes, José Antonio Ramírez, Tania Vite-Garín. Project Administration: Terezinha do Menino Jesus Silva Leitão, Maria Lucia Taylor, Rosely Maria Zancopé-Oliveira. Resources: Lisandra Serra Damasceno, Jacó Ricarte Lima de Mesquita, Terezinha do Menino Jesus Silva Leitão, Maria Lucia Taylor, Rodrigo Almeida-Paes, Rosely Maria Zancopé-Oliveira. Supervision: Rosely Maria Zancopé Oliveira. Validation: Rodrigo Almeida-Paes. Visualization: Lisandra Serra Damasceno, Marcus de Melo Teixeira, Gabriela Rodríguez-Arellanes, José Antonio Ramírez, Tania Vite-Garín. Writing – original draft: Lisandra Serra Damasceno, Marcus de Melo Teixeira, Bridget Marie Barker. Writing, review, and editing: Maria Lucia Taylor, Rodrigo Almeida-Paes, Rosely Maria Zancopé-Oliveira.

Data Availability

The datasets correspondent to the sequenced genes generated during the current study are available in the GenBank repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/). Accession numbers and all other data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published articleand its Supplementary Information files.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lisandra Serra Damasceno, Marcus de Melo Teixeira, Maria Lucia Taylor and Rosely Maria Zancopé-Oliveiran contributed equally.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-48111-6.

References

- 1.Teixeira MM, et al. Worldwide Phylogenetic distributions and population dynamics of the genus Histoplasma. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016;10:e0004732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor ML, et al. Environmental conditions favoring bat infection with Histoplasma capsulatum in Mexican shelters. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1999;61:914–919. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calanni LM, et al. Brote de histoplasmosis en la provincia de Neuquén, Patagonia Argentina. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2013;30:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burek-Huntington KA, Gill V, Bradway DS. Locally acquired disseminated histoplasmosis in a northern sea otter (Enhydra lutris kenyoni) in Alaska, USA. J. Wildl Dis. 2014;50:389–392. doi: 10.7589/2013-11-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brilhante RS, et al. Feline histoplasmosis in Brazil: clinical and laboratory aspects and a comparative approach of published reports. Mycopathologia. 2012;173:193–197. doi: 10.1007/s11046-011-9477-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benedict K, Mody RK. Epidemiology of histoplasmosis outbreaks, United States, 1938–2013. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016;22:370–378. doi: 10.3201/eid2203.151117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colombo AL, Tobon A, Restrepo A, Queiroz-Telles F, Nucci M. Epidemiology of endemic systemic fungal infections in Latin America. Med. Mycol. 2011;49:785–798. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2011.577821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brilhante RS, et al. Histoplasmosis in HIV-positive patients in Ceara, Brazil: clinical-laboratory aspects and in vitro antifungal susceptibility of Histoplasma capsulatum isolates. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012;106:484–488. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damasceno LS, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis and aids: relapse and late mortality in endemic area in North-Eastern Brazil. Mycoses. 2013;56:520–526. doi: 10.1111/myc.12067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couppie P, Aznar C, Carme B, Nacher M. American histoplasmosis in developing countries with a special focus on patients with HIV: diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Curr.Opin. Infect. Dis. 2006;19:443–449. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000244049.15888.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sepulveda VE, Williams CL, Goldman WE. Comparison of phylogenetically distinct Histoplasma strains reveals evolutionarily divergent virulence strategies. MBio. 2014;5:e01376–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01376-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damasceno LS, Leitao TM, Taylor ML, Muniz MM, Zancope-Oliveira RM. The use of genetic markers in the molecular epidemiology of histoplasmosis: a systematic review. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016;35:19–27. doi: 10.1007/s10096-015-2508-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasuga T, Taylor JW, White TJ. Phylogenetic relationships of varieties and geographical groups of the human pathogenic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum Darling. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999;37:653–663. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.653-663.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasuga T, et al. Phylogeography of the fungal pathogen Histoplasma capsulatum. Mol. Ecol. 2003;12:3383–3401. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wheat LJ, et al. Histoplasmosis. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2016;30:207–227. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giacomazzi J, et al. The burden of serious human fungal infections in Brazil. Mycoses. 2016;59:145–150. doi: 10.1111/myc.12427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fava SC, Netto CF. Epidemiologic surveys of histoplasmin and paracoccidioidin sensitivity in Brazil. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. S. Paulo. 1998;40:155–164. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46651998000300005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guimaraes AJ, Nosanchuk JD, Zancope-Oliveira RM. Diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2006;37:1–13. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822006000100001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diógenes MJ, et al. Reações à histoplasmina e paracoccidioidina na Serra de Pereiro (estado do Ceará-Brasil) Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. S. Paulo. 1990;32:116–120. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46651990000200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Façanha MC, et al. Estudo soroepidemiológico de paracoccidioidomicose em Palmácia, Ceará. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 1991;24(Supl 2):28. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bezerra FS, et al. Histoplasmin survey in HIV-positive patients: results from an endemic area in northeastern Brazil. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. S. Paulo. 2013;55:261–265. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652013000400007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daher FE, et al. Risk factors for death in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated disseminated histoplasmosis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2006;74:600–603. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2006.74.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pontes LB, Leitao TMJS, Lima GG, Gerhard ES, Fernandes TA. Características clínico-evolutivas de 134 pacientes com histoplasmose disseminada associada a SIDA no Estado do Ceará. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2010;43:27–31. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822010000100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prado M, Silva MB, Laurenti R, Travassos LR, Taborda CP. Mortality due to systemic mycoses as a primary cause of death or in association with AIDS in Brazil: a review from 1996 to 2006. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104:513–521. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762009000300019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Correia FGS, et al. Spatial distribution of disseminated histoplasmosis and AIDS co-infection in an endemic area of Northeastern Brazil. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2016;49:227–231. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0327-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gutierrez ME, Canton A, Sosa N, Puga E, Talavera L. Disseminated histoplasmosis in patients with AIDS in Panama: a review of 104 cases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005;40:1199–1202. doi: 10.1086/428842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adenis A, et al. HIV-associated histoplasmosis early mortality and incidence trends: from neglect to priority. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014;8:e3100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.CDC. Revision of the CDC surveillance case definition for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists; AIDS Program, Center for Infectious Diseases. MMWR Suppl. 1987;36:1S–15S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vite-Garin T, Estrada-Barcenas DA, Cifuentes J, Taylor ML. The importance of molecular analyses for understanding the genetic diversity of Histoplasma capsulatum: an overview. Rev. Iberoam. Mycol. 2014;31:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blackard JT, Sherman KE. Hepatitis C virus coinfection and superinfection. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;195:519–524. doi: 10.1086/510858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen T, et al. Mixed-strain Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections and the implications for tuberculosis treatment and control. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012;25:708–719. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00021-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Wyk M, Govender NP, Mitchell TG, Litvintseva AP, Germs SA. Multilocus sequence typing of serially collected isolates of Cryptococcus from HIV-infected patients in South Africa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014;52:1921–1931. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03177-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helweg-Larsen J, et al. Clinical correlation of variations in the internal transcribed spacer regions of rRNA genes in Pneumocystis carinii f.sp. hominis. AIDS. 2001;15:451–459. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200103090-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sil A, Andrianopoulos A. Thermally dimorphic human fungal pathogens-polyphyletic pathogens with a convergent pathogenicity trait. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014;5:a019794. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Durkin MM, et al. Pathogenic differences between North American and Latin American strains of Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum in experimentally infected mice. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:4370–4373. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.9.4370-4373.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karimi K, et al. Differences in histoplasmosis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in the United States and Brazil. J. Infect. Dis. 2002;186:1655–1660. doi: 10.1086/345724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sahaza JH, Perez-Torres A, Zenteno E, Taylor ML. Usefulness of the murine model to study the immune response against Histoplasma capsulatum infection. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014;37:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nieduszynski CA, Liti G. From sequence to function: Insights from natural variation in budding yeasts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1810:959–966. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wohlbach DJ, et al. Comparative genomics of Saccharomyces cerevisiae natural isolates for bioenergy production. Gen. Biol. Evol. 2014;6:2557–2566. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ene IV, Bennett RJ. The cryptic sexual strategies of human fungal pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014;12:239–251. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tibayrenc M, Ayala FJ. Reproductive clonality of pathogens: a perspective on pathogenic viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasitic protozoa. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E3305–E3313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212452109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grigg ME, Bonnefoy S, Hehl AB, Suzuki Y, Boothroyd JC. Success and virulence in Toxoplasma as the result of sexual recombination between two distinct ancestries. Science. 2001;294:161–165. doi: 10.1126/science.1061888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fressatti R, Dias-Siqueira VL, Svidzinski TIE, Herrero F, Kemmelmeier C. A medium for inducing conversion of Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum into its yeast-like form. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 1992;87:53–58. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02761992000100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Standard PG, Kaufman L. Specific immunological test for the rapid identification of members of the genus. Histoplasma. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1976;3:191–199. doi: 10.1128/jcm.3.2.191-199.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pizzini CV, et al. Evaluation of a western blot test in an outbreak of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 1999;6:20–23. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.1.20-23.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bubnick M, Smulian AG. The MAT1 locus of Histoplasma capsulatum is responsive in a mating type-specific manner. Eukaryot. Cell. 2007;6:616–621. doi: 10.1128/EC.00020-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodriguez-Arellanes G, et al. Frequency and genetic diversity of the MAT1 locus of Histoplasma capsulatum isolates in Mexico and Brazil. Eukaryot. Cell. 2013;12:1033–1038. doi: 10.1128/EC.00012-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Don RH, Cox PT, Wainwright BJ, Baker K, Mattick JS. ‘Touchdown’ PCR to circumvent spurious priming during gene amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4008. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.14.4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLASTn) J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015;32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Minh BQ, Nguyen MA, von Haeseler A. Ultrafast approximation for phylogenetic bootstrap. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:1188–1195. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ronquist F, et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rambaut, A. FigTree v1.3.1: Tree figure drawing tool. Preprint at, http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtre?e/ (2009).

- 56.Huson DH, Bryant D. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006;23:254–267. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Corander, J., Cheng, L., Marttinen, P., Sirén, J. & Tang, J. BAPS: Bayesian Analysis of Population Structure. BAPS, http://www.helsinki.fi/bsg/software/BAPS/ (2011).

- 58.Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1451–1452. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets correspondent to the sequenced genes generated during the current study are available in the GenBank repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/). Accession numbers and all other data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published articleand its Supplementary Information files.