Abstract

In the present study, we aim to examine the relationship between genetic polymorphism and transcriptional expression of cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREBBP) and the risk of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Two hundred and fifty healthy individuals and 248 DLBCL patients participated in the present study. The CREBBP rs3025684 polymorphism was detected by polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP). The mRNA expression of CREBBP was tested by the real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). The allele A frequency of CREBBP rs3025684 in DLBCL patients was obviously higher than that of controls (P=0.01). No significant difference was detected between CREBBP rs3025684 polymorphism and clinical characteristics of DLBCL patients when subgrouped according to different parameters. The results demonstrated that the allele A of CREBBP rs3025684 increased the susceptibility to DLBCL (P=0.004), with a worse overall survival (OS) rate (P=0.002), a worse progression-free survival (PFS) rate (P=0.033) and poor prognosis (P=0.003) in DLCBL patients. Furthermore, the expression of CREBBP mRNA was considerably decreased in DLBCL patients as compared with controls (P<0.001), and the expression in patients with GG genotype was up-regulated in comparison with patients with GA and AA genotype (P=0.016 and P=0.001, respectively). However, no statistical differences were found in OS (P=0.201) and PFS (P=0.353) between the lower CREBBP mRNA level subgroup and higher CREBBP mRNA level subgroup. These data suggested that the CREBBP gene may be an important prognostic factor in DLBCL patients and perform an essential function in the development of DLBCL.

Keywords: CREBBP, DLBCL, expression, polymorphism

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is an aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma with extreme heterogeneity, accounting for 30–40% of newly diagnosed lymphomas [1]. Although the standard R-CHOP regimen has extremely good therapeutic effect on DLBCL patients, approximately 30–40% of patients show relapse and 10% have refractory disease [2]. In the past decades, accumulating evidences have shown the genetic, microenvironment, autoimmune diseases and occupational exposure participated in the pathogenesis of DLBCL [3–5]. With gene-expression profiling and next-generation sequencing, some common genetic loci are found to enmesh in the lymphomagenesis of DLBCL [6]. However, the pathogenesis of DLBCL is still not fully understood.

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) is the most abundant type of genetic variation that occurs at a specific position in the human genome. Accumulating evidence indicated that SNPs have shown the ability to influence the activity and expression of the genes, and affect the pathogenesis and risk of an extensive range of cancer [7–10]. Previous studies have demonstrated that SNPs in TP53, XRCC1 and A20 are related to the risk of DLBCL [11–13]. Genome-wide association studies have recognized genetic susceptibility locus for DLBCL [14]. The contribution of SNP in histone-modifying enzymes to DLBCL pathogenesis is a research hotspot.

Somatic mutations in cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREBBP) and EP300, and removal or inactivation of the HAT coding domain affect approximately 39% of DLBCL patients [15], and are also associated with Rubinstein Tyabi Syndrome (RTS) [16,17]. CREBBP belongs to the KAT3 family of histone/protein lysine acetyltransferases, which is a highly conserved and universally expressed nuclear phosphoprotein [18,19]. CREBBP inactivation expedites GC-derived pathogenesis of lymphoma [20]. Down-regulation of CREBBP is related to worse overall survival (OS) rate in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia and may affect the response to chemotherapy [21]. Crebbp+/− mice had blemish in the development of B-cell lymphoid and an increased incidence of hematopoietic malignancy [22]. The rs3025684 (A/G) is an SNP of CREBBP located in intron 21. This SNP was shown to be a possible risk factor for developing autism in the Netherlands, U.K. and Denmark, as well as among Bengali-Hindus [23,24].

However, the status of CREBBP rs3025684 SNP and the gene expression in DLBCL in a Chinese Han population is not completely understood. It was hypothesized that CREBBP rs3025684 polymorphism and expression may be related to the susceptibility and pathogenesis of DLBCL, and the results found that it may be a prognostic factor for DLBCL patients.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The present study recruited 250 healthy individuals and 248 DLBCL patients, diagnosed according to the World Health Organization classification [25] at Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital from 2011 to 2013. Peripheral blood and lymphoid specimens were collected before initial therapy. All participants signed the informed consent, and the approval of the study was obtained from the Tianjin Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board. The clinical and pathological characteristics of the patients and controls are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of DLBCL patients.

| Characteristics | Number (n=248) n (%) | Control (n=250) n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 112 (45.16) | 109 (43.60) |

| Female | 136 (54.84) | 141 (56.40) |

| Age | ||

| ≤60 | 165 (66.53) | 184 (73.60) |

| >60 | 83 (33.47) | 66 (26.40) |

| Subtype | ||

| GCB | 75 (30.24) | |

| nGCB | 173 (69.76) | |

| Ann-arbor stage | ||

| I–II | 152 (61.29) | |

| III–IV | 96 (38.71) | |

| IPI score | ||

| 0–1 | 133 (53.63) | |

| 2–5 | 115 (46.37) | |

| ECOG | ||

| 0–1 | 230 (92.74) | |

| 2–5 | 18 (7.26) | |

| B symptom | ||

| + | 79 (31.85) | |

| − | 169 (68.15) | |

| Extra nodal sites | ||

| + | 156 (62.90) | |

| − | 92 (37.10) | |

| Bone marrow involvement | ||

| + | 21 (8.47) | |

| − | 227 (91.53) | |

| HBV infection | ||

| + | 74 (29.84) | |

| − | 174 (70.16) | |

| Bulky tumor (>10 cm) | ||

| + | 55 (22.18) | |

| − | 193 (77.82) | |

| Elevated LDH | ||

| + | 98 (39.52) | |

| − | 150 (60.48) | |

| Elevated β2-MG | ||

| + | 86 (34.68) | |

| − | 162 (65.32) | |

| KI-67 | ||

| ≤75% | 93 (37.50) | |

| >75% | 155 (62.50) | |

| Source | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 116 (46.77) | |

| Others | 132 (53.23) | |

| Response rate | ||

| PR+CR | 215 (86.69) |

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IPI, International Prognostic Index; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PR, partial response; β2-MG, β2 macroglobulin.

Extraction of DNA and genotyping of CREBBP rs3025684

The TIANamp genomic DNA kit (TIANGEN Biotech, Beijing, China) was used to extract the genomic DNA according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Genotypes were analyzed by polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP). The reaction system contained 60 ng DNA template, 2 μl of each primer, 25 μl Premix Taq (Takara, Dalian, China) and sterilized water up to 50 μl. The PCR protocol was as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 58°C for 30 s, extension at 72°C for 30 s, followed by 72°C for 7 min. The primers for rs3025684 were: forward 5′-AGGGGAAACAACTCACCCTG-3′ and reverse 5′-CTGGTCTTGTGGTTCCGTGT-3′. The PCR product was digested by MnlI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) and analyzed by gel electrophoresis on 2.5% agarose gels. Randomly selected DNA samples were detected by direct sequencing to verify the results (Supplementary Figure S1).

Isolation of RNA and reverse-transcription quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). We normalized the levels of expression of CREBBP relative to glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and 2−ΔΔCt indicated the quantification of gene expression. The primers for CREBBP were: forward 5′-CGGCTCTAGTATCAACCCAGG-3′ and reverse 5′- TTTTGTGCTTGCGGATTCAGT-3′. The primers for GAPDH were: forward 5′-CCACATCGCTCAGACACCAT-3′ and reverse 5′-CCAGGCGCCCAATACG-3′.

Statistical analysis

A goodness-of-fit Chi-square test was used to analyze the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. The Chi-square test was used to detect the allelic frequency and genotypic distribution in all subjects. We estimated the relationship between CREBBP rs3025684 and the susceptibility to DLBCL by unconditional logistic regression. The prognostic factors were explored by univariate Cox regression analysis. The CREBBP mRNA expression levels were investigated by the independent Student’s t test. The survival curves were computed by Kaplan–Meier method with log-rank tests. All the statistical analyses mentioned above were executed by IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0. P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The false-positive report probability (FPRP) was calculated as previously described [26], we set an FPRP value of 0.2 and assigned a prior probability of 0.1.

Results

Characteristics of study subjects

The genotypic distributions in both patients and controls were under the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P>0.05). The genotypic distribution and allelic frequencies showed significant difference between the DLBCL patients and healthy individuals for CREBBP rs3025684 (P=0.021 and P=0.013, respectively, shown in Table 2). Furthermore, the association between the genotype and the clinical parameters of DLBCL patients was explored, which showed no statistical differences as shown in Table 3.

Table 2. Genotype distribution and allele frequencies of CREBBP rs3025684 polymorphism in DLBCL patients and the controls.

| Control (n=250) n (%) | DLBCL patients (n=248) n (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype frequency | |||

| GG | 153 (61.20) | 121 (48.79) | 0.021 |

| GA | 86 (34.40) | 113 (45.56) | |

| AA | 11 (4.40) | 14 (5.65) | |

| Allele frequency | |||

| G | 392 (78.40) | 355 (71.57) | 0.013 |

| A | 108 (21.60) | 141 (28.43) |

Table 3. Characteristics of DLBCL patients and their association with CREBBP rs3025684.

| Characteristics | Number | Genotype | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=248) n (%) | GA+AA, n (%) | GG, n (%) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 112 (45.16) | 61 (24.60) | 51 (20.56) | 0.352 |

| Female | 136 (54.84) | 66 (26.61) | 70 (28.23) | |

| Age | ||||

| ≤60 | 165 (66.53) | 87 (35.08) | 78 (31.45) | 0.500 |

| >60 | 83 (33.47) | 40 (16.13) | 43 (17.34) | |

| Subtype | ||||

| GCB | 75 (30.24) | 38 (15.32) | 37 (14.92) | 0.910 |

| nGCB | 173 (69.76) | 89 (35.89) | 84 (33.87) | |

| Ann-arbor stage | ||||

| I–II | 152 (61.29) | 73 (29.44) | 79 (31.85) | 0.207 |

| III–IV | 96 (38.71) | 54 (21.77) | 42 (16.94) | |

| IPI score | ||||

| 0–1 | 133 (53.63) | 62 (25.00) | 71 (28.63) | 0.120 |

| 2–5 | 115 (46.37) | 65 (26.21) | 50 (20.16) | |

| ECOG | ||||

| 0–1 | 230 (92.74) | 114 (45.97) | 116 (46.77) | 0.064 |

| 2–5 | 18 (7.26) | 13 (5.24) | 5 (2.02) | |

| B symptom | ||||

| + | 79 (31.85) | 43 (17.34) | 36 (14.52) | 0.488 |

| − | 169 (68.15) | 84 (33.87) | 85 (34.27) | |

| Bone marrow involvement | ||||

| + | 21 (8.47) | 11 (4.44) | 10 (4.03) | 0.911 |

| − | 227 (91.53) | 116 (46.77) | 111 (44.76) | |

| HBV infection | ||||

| + | 74 (29.84) | 39 (15.73) | 35 (14.11) | 0.759 |

| − | 174 (70.16) | 88 (35.48) | 86 (34.68) | |

| Bulky tumor (>10 cm) | ||||

| + | 55 (22.18) | 31 (12.50) | 24 (9.68) | 0.386 |

| − | 193 (77.82) | 96 (38.71) | 97 (39.11) | |

| Elevated LDH | ||||

| + | 98 (39.52) | 57 (22.98) | 41 (16.53) | 0.077 |

| − | 150 (60.48) | 70 (28.23) | 80 (32.26) | |

| Elevated β2-MG | ||||

| + | 86 (34.68) | 41 (16.53) | 43 (17.34) | 0.588 |

| − | 162 (65.32) | 86 (34.68) | 78 (31.45) | |

| KI-67 | ||||

| ≤75% | 93 (37.50) | 50 (20.16) | 43 (17.34) | 0.533 |

| >75% | 155 (62.50) | 77 (31.05) | 78 (31.45) | |

| Source | ||||

| Gastrointestinal | 116 (46.77) | 55 (22.18) | 61 (24.60) | 0.262 |

| Others | 132 (53.23) | 72 (29.03) | 60 (24.19) | |

Abbreviations: LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IPI, International Prognostic Index; β2-MG, β2 macroglobulin.

Relationship between the CREBBP rs3025684 and the susceptibility to DLBCL

The GA genotype was correlated with the risk of DLBCL (odds ratio (OR) = 1.692, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) = 1.170–2.446, P=0.005) (Table 4). However, the AA genotype displayed a slightly increased susceptibility to DLBCL with no statistical significance (OR = 1.620, 95% CI = 0.710–3.696, P=0.252, P=0.252) (Table 4). The combined AA and GA genotype was significantly related to increased susceptibility to DLBCL (OR = 1.684, 95% CI = 1.179–2.404, P=0.004) (Table 4). The results for dominant and recessive models are shown in Table 4. As no statistical significance was shown in the dominant model, we did not calculate the FPRP values and statistical power for the dominant model. Positive association was observed in the recessive model and GA genotype as their FPRP value was less than 0.2 (shown in Table 4).

Table 4. Association between CREBBP rs3025684 polymorphism and the risk of DLBCL.

| Genotype | OR (95% CI) | P | Statistical power | Prior probability | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.0001 | ||||

| AA vs. GG | 1.620 (0.710–3.696) | 0.252 | ||||||

| GA vs.GG | 1.692 (1.170–2.446) | 0.005 | 0.500 | 0.030 | 0.085 | 0.505 | 0.0912 | 0.990 |

| GA/AA vs. GG | 1.684 (1.179–2.404) | 0.004 | 0.500 | 0.024 | 0.069 | 0.449 | 0.891 | 0.988 |

| GA/GG vs. AA | 0.769 (0.342–1.729) | 0.526 | ||||||

Survival analysis of DLBCL patients according to the CREBBP rs3025684

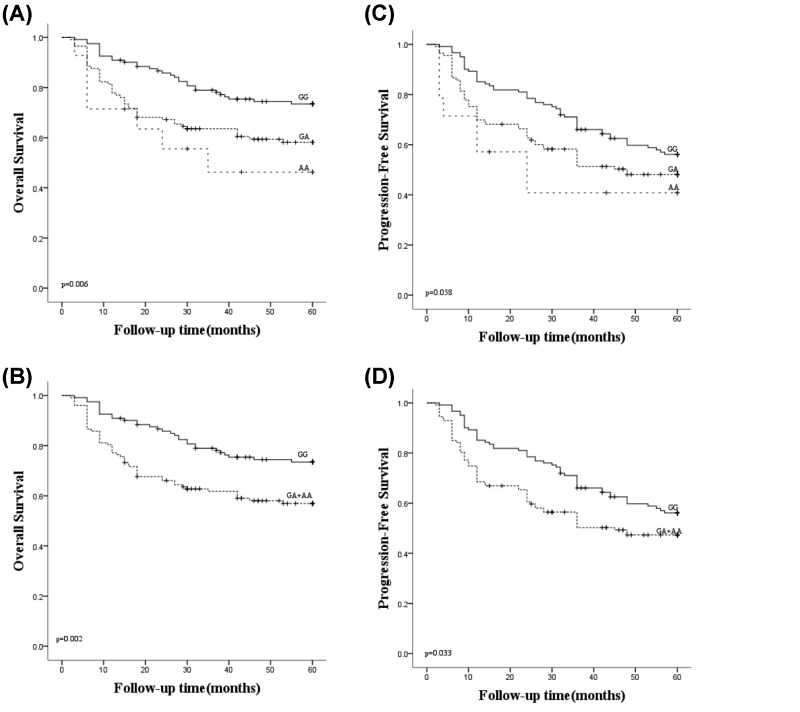

The survival analysis of all 248 DLBCL patients showed that the patients with genotype GA/AA (P=0.006, Figure 1A) and the combined GA and AA group (P=0.002, Figure 1B) had a worse OS than patients with GG genotype. Furthermore, the patients with GA/AA genotype had a worse progression-free survival (PFS) in comparison with the GG patients with no statistical significance (P=0.058, Figure 1C), however, the combined GA and AA group showed worse PFS rate compared with the GG group with statistically significant (P=0.033, Figure 1D). Furthermore, it was also indicated that patients with A allele showed poor prognosis (P=0.003, HR = 1.944, 95% CI = 1.247–3.029).

Figure 1. Survival analyses of DLBCL patients under the genotype of CREBBP rs3025684.

(A) OS analysis compared among the GG, GA and AA subgroups (P=0.006). (B) OS analysis compared between the GG subgroup and the combined GA/AA subgroup (P=0.002). (C) PFS analysis compared among the GG, GA and AA subgroups (P=0.058). (D) PFS analysis compared between the GG subgroup and the combined GA/AA subgroup (P=0.033). A check mark indicates that the data is censored.

Analysis of the CREBBP mRNA expression levels

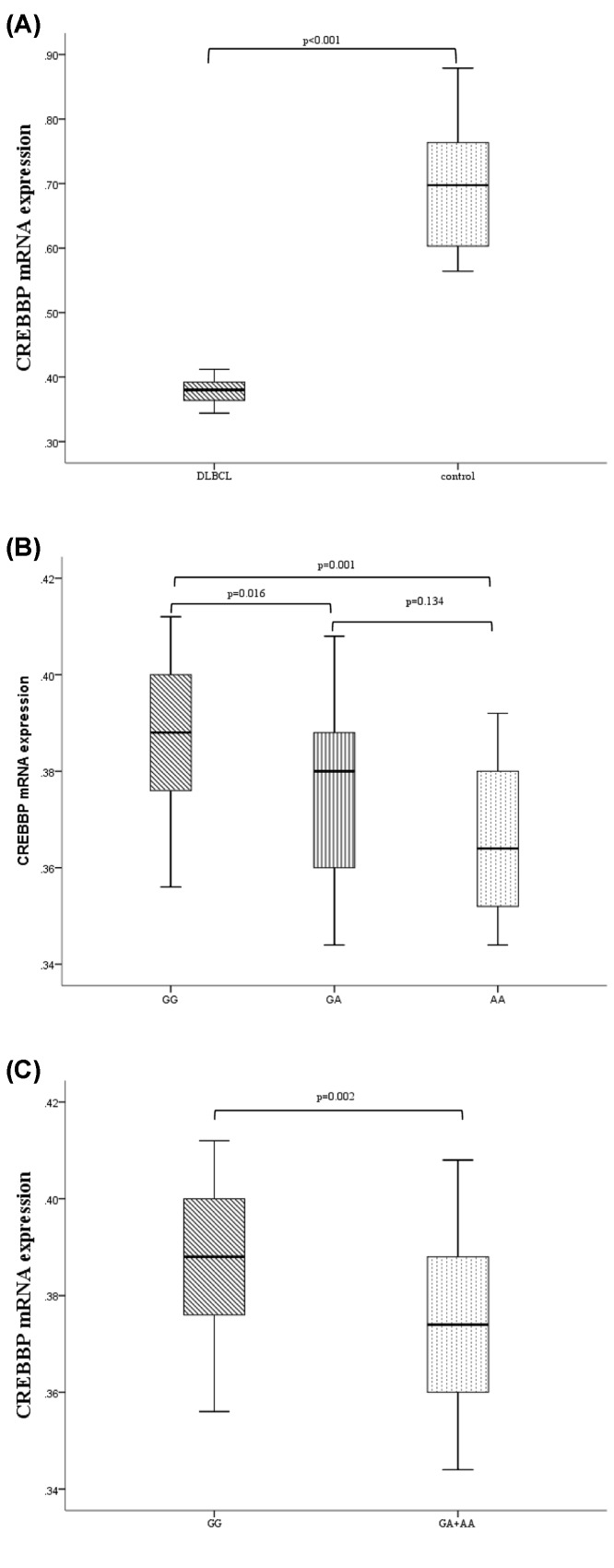

CREBBP expression was detected in 63 patients and 32 controls. The results showed that the CREBBP expression was remarkably down-regulated in patients as compared with controls (P<0.001, Figure 2A). The CREBBP expression of patients with GG genotype was down-regulated as compared with the patients with GA and AA genotype (P=0.016 and 0.001, respectively, Figure 2B). However, no significant difference was detected between the GA and AA subgroups (P=0.134, Figure 2B). The CREBBP expression was down-regulated in the GA/AA subgroup as compared with the GG subgroup (P=0.002, Figure 2C).

Figure 2. The expression of CREBBP mRNA in DLBCL patients.

(A) The expression of CREBBP mRNA in DLBCL patients was down-regulated as compared with the controls (P<0.001). (B) The expression of CREBBP mRNA in DLBCL patients with GG genotype was significantly up-regulated than those with GA and AA genotypes (P=0.016 and 0.001, respectively). (C) The expression of CREBBP mRNA in DLBCL patients with GA/AA genotype was significantly down-regulated than those with GG genotype (P=0.002).

Survival analysis based on the CREBBP mRNA levels of DLBCL patients

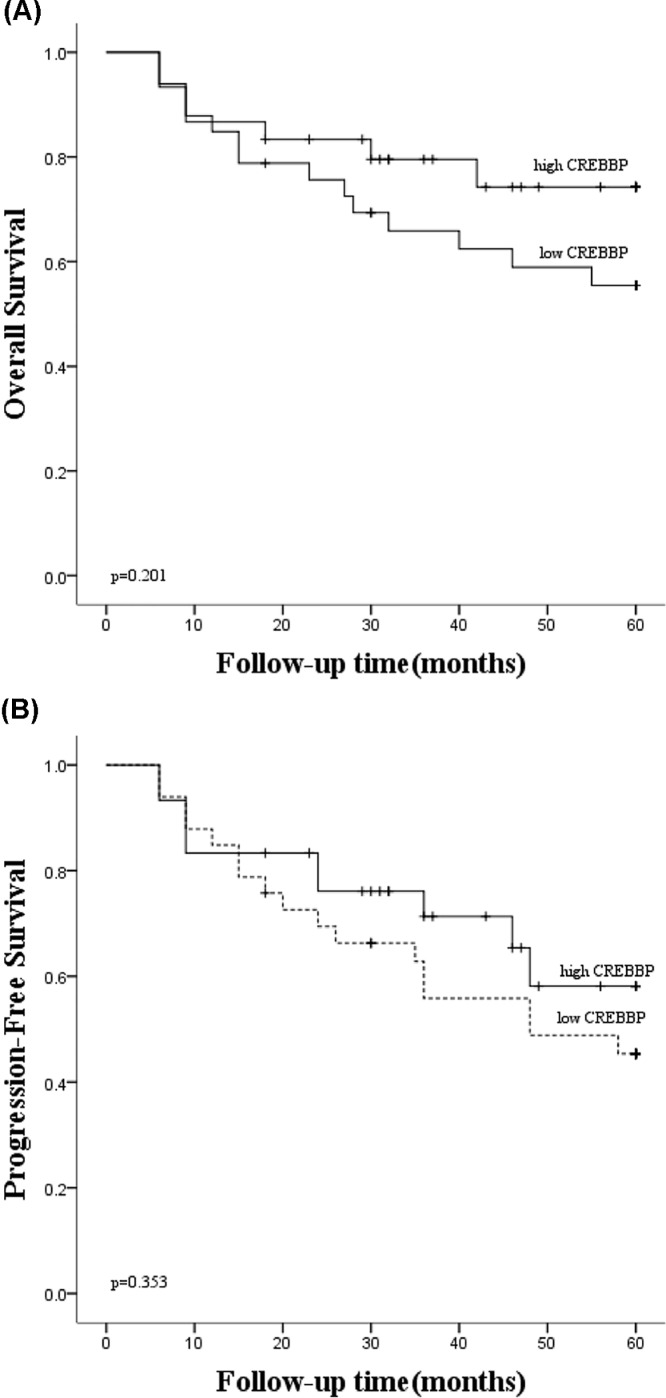

Based on the median of CREBBP mRNA expression value, 63 DLBCL patients were partitioned into two subgroups, the low CREBBP expression subgroup and the high CREBBP expression subgroup. The results indicated no significant differences between the patients with lower CREBBP mRNA level and those with high CREBBP mRNA level in OS (P=0.201, Figure 3A) and PFS (P=0.353, Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Survival analyses of DLBCL patients according to CREBBP mRNA expression.

(A) The OS analysis indicated no significant differences between lower CREBBP subgroup and high CREBBP subgroup (P=0.201). (B) The PFS analysis indicated no significant differences between the lower CREBBP subgroup and high CREBBP subgroup (P=0.353). A check mark indicates that the data is censored.

Discussion

DLBCL is an example of a translocation-based cancer, in which key genes are dysregulated by active lineage-specific promoters or enhancers due to characteristic equilibrium translocations [6]. The evolution of DLBCL was a multi-step procedure that requires the cumulation of multiple genetic pathological changes [14,27]. By the modern genome-wide molecular analysis, an abundance of altered cellular pathways that perform vital functions in the development of DLBCL and the sensitivity of cancer cells to therapy was detected. However, the notable heterogeneity of this disease partly limits the effective treatment. Therefore, it is necessary to seek ameliorated special biomarkers, permitting the devising of more efficient and accurate medical methods to specific cancer-causing addictions.

CREBBP, one of the most frequently mutated genes in DLBCL [15,28–30], acts as a tumor repressor of GC-derived pathogenesis of lymphoma [31]. Most of the CREBBP-binding regions in GC B cells displayed characteristics of transcriptionally active (or suspended) enhancers [32], which control the cell type-specific transcription [33]. CREBBP acetylates H3K27 on the promoter or enhancer sequence of the BCL6 target genes, promoting transcription to counteracting the inhibition of BCL6, which leads to the opposition of proto-oncogene activity of BCL6 [20,31]. Therefore, CREBBP may be considered as a tumor therapeutic target in DLBCL patients.

Gene expression-based categorization of DLBCL has been established [34,35], and the relevance to prognosis has been illustrated [36]. It has been demonstrated that certain genetic defects and distinct signal transduction pathways occur in specific subtypes [37,38]. In this study, the association between CREBBP rs3025684 polymorphism and its expression with the susceptibility and survival of DLBCL patients was investigated. The results showed that the A allele carriers were related to increased risk of DLBCL and had worse OS rate and PFS rate. Hence, CREBBP rs3025684 polymorphism may be used as a hallmark for the prediction of risk and prognosis of DLBCL.

In East Asians, the frequency of A allele of CREBBP rs3025684 was reported to be 19.3% in the HapMap Project. However, the present study showed that the frequency of allele A in controls and DLBCL patients was 21.60 and 28.43%, respectively. This difference in allele frequency may owe to the risk effects of allele A and the small sample size. In the recessive model, the positive association between the risk of DLBCL and CREBBP rs3025684 was observed. However, the statistical power was only 0.5, which may be a result of the small simple size.

The CREBBP/EP300 complex participates in numerous life events, such as cell growth, proliferation, apoptosis, metabolism and oncogenesis [18,39,40]. CREBBP/EP300 complex also targets many transcriptional factors significantly related to the development of B-cell lymphoma and immune response, such as p53 and c-MYC [41–43]. HAT activity is related to the survival rate of patients with B-cell lymphoma [31,44]. Furthermore, HAT mutations likely predict treatment efficiency in epigenetically targeted therapy, such as the HDAC3 inhibitors [20,45]. The present study indicated that the expression of CREBBP was notably down-regulated in patients as compared with the controls, and was especially down-regulated in the GA/AA genotype subgroup, indicating that CREBBP may be used as a therapeutic target for DLBCL.

In conclusion, the polymorphism and expression of CREBBP gene may play a vital role as a genetic risk factor and poor prognostic factor among DLBCL Chinese Han patients, indicating that CREBBP could be used for the prognosis and treatment of DLBCL. Additional studies with larger sample sizes are necessary to verify the results and further functional analyses are warranted to explore the lymphoma biology.

Supporting information

Supplementary Figure S1.

Abbreviations

- CREBBP

cyclic AMP response element binding protein

- DLBCL

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- FPRP

false-positive report probability

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase

- HAT

histone acetyltransferase

- HDAC3

histone deacetylase 3

- HR

hazard ratio

- OR

odds ratio

- OS

overall survival

- PFS

progression-free survival

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- 95% CI

95% confidence interval

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant numbers 81100337, 81470283].

Author Contribution

Z.Q. and H.Z. designed the research. Y.K. performed the experiment, analyzed the experimental data and wrote the manuscript. H.Z., P.G. and X.W. helped to analyze the experimental data and collected the samples. L.C. gathered the clinical information. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Lenz G. and Staudt L.M. (2010) Aggressive lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 1417–1429 10.1056/NEJMra0807082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coiffier B., Thieblemont C., Van Den Neste E., Lepeu G., Plantier I., Castaigne S.. et al. (2010) Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d’Etudes des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. Blood 116, 2040–2045 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morton L.M., Slager S.L., Cerhan J.R., Wang S.S., Vajdic C.M., Skibola C.F.. et al. (2014) Etiologic heterogeneity among non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes: the InterLymph Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Subtypes Project. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2014, 130–144 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgu013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerhan J.R. and Slager S.L. (2015) Familial predisposition and genetic risk factors for lymphoma. Blood 126, 2265–2273 10.1182/blood-2015-04-537498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott D.W. and Gascoyne R.D. (2014) The tumour microenvironment in B cell lymphomas. Nat. Rev. Cancer 14, 517–534 10.1038/nrc3774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armitage J.O., Gascoyne R.D., Lunning M.A. and Cavalli F. (2017) Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Lancet 390, 298–310 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32407-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abd El-Fattah A.A., Sadik N.A.H., Shaker O.G. and Mohamed Kamal A. (2018) Single nucleotide polymorphism in SMAD7 and CHI3L1 and colorectal cancer risk. Mediators Inflamm. 2018, 9853192. 10.1155/2018/9853192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wen J., Lv Z., Ding H., Fang X. and Sun M. (2018) Association of miRNA biosynthesis genes DROSHA and DGCR8 polymorphisms with cancer susceptibility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biosci. Rep. 38, 10.1042/BSR20180072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu C., Cui H., Gu D., Zhang M., Fang Y., Chen S.. et al. (2017) Genetic polymorphisms and lung cancer risk: Evidence from meta-analyses and genome-wide association studies. Lung Cancer 113, 18–29 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu G.C., Zhou Y.F., Su X.C. and Zhang J. (2019) Interaction between TP53 and XRCC1 increases susceptibility to cervical cancer development: a case control study. BMC Cancer 19, 24. 10.1186/s12885-018-5149-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y., Bai O., Cui J. and Li W. (2016) Genetic polymorphisms in the DNA repair gene, XRCC1 associate with non-Hodgkin lymphoma susceptibility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 59, 91–103 10.1016/j.ejmg.2015.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wenzl K., Hofer S., Troppan K., Lassnig M., Steinbauer E., Wiltgen M.. et al. (2016) Higher incidence of the SNP Met 788 Ile in the coding region of A20 in diffuse large B cell lymphomas. Tumour Biol. 37, 4785–4789 10.1007/s13277-015-4322-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y., Wang X., Ding N., Mi L., Ping L., Jin X.. et al. (2017) TP53 Arg72 as a favorable prognostic factor for Chinese diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with CHOP. BMC Cancer 17, 743. 10.1186/s12885-017-3760-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cerhan J.R., Berndt S.I., Vijai J., Ghesquieres H., McKay J., Wang S.S.. et al. (2014) Genome-wide association study identifies multiple susceptibility loci for diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Nat. Genet. 46, 1233–1238 10.1038/ng.3105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pasqualucci L., Dominguez-Sola D., Chiarenza A., Fabbri G., Grunn A., Trifonov V.. et al. (2011) Inactivating mutations of acetyltransferase genes in B-cell lymphoma. Nature 471, 189–195 10.1038/nature09730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartsch O., Schmidt S., Richter M., Morlot S., Seemanova E., Wiebe G.. et al. (2005) DNA sequencing of CREBBP demonstrates mutations in 56% of patients with Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome (RSTS) and in another patient with incomplete RSTS. Hum. Genet. 117, 485–493 10.1007/s00439-005-1331-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stef M., Simon D., Mardirossian B., Delrue M.A., Burgelin I., Hubert C.. et al. (2007) Spectrum of CREBBP gene dosage anomalies in Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome patients. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 15, 843–847 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodman R.H. and Smolik S. (2000) CBP/p300 in cell growth, transformation, and development. Genes Dev. 14, 1553–1577 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalkhoven E. (2004) CBP and p300: HATs for different occasions. Biochem. Pharmacol. 68, 1145–1155 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.03.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang Y., Ortega-Molina A., Geng H., Ying H.Y., Hatzi K., Parsa S.. et al. (2017) CREBBP inactivation promotes the development of HDAC3-dependent lymphomas. Cancer Discov. 7, 38–53 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao C., Zhang R.D., Liu S.G., Zhao X.X., Cui L., Yue Z.X.. et al. (2017) Low CREBBP expression is associated with adverse long-term outcomes in paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Eur. J. Haematol. 99, 150–159 10.1111/ejh.12897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kung A.L., Rebel V.I., Bronson R.T., Ch’ng L.E., Sieff C.A., Livingston D.M.. et al. (2000) Gene dose-dependent control of hematopoiesis and hematologic tumor suppression by CBP. Genes Dev. 14, 272–277 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnby G., Abbott A., Sykes N., Morris A., Weeks D.E., Mott R.. et al. (2005) Candidate-gene screening and association analysis at the autism-susceptibility locus on chromosome 16p: evidence of association at GRIN2A and ABAT. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 76, 950–966 10.1086/430454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar D., Deb I., Chakraborty J., Mukhopadhyay S. and Das S. (2011) A polymorphism of the CREB binding protein (CREBBP) gene is a risk factor for addiction. Brain Res. 1406, 59–64 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.05.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner J.J., Hughes A.M., Kricker A., Milliken S., Grulich A., Kaldor J.. et al. (2005) WHO non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma classification by criterion-based report review followed by targeted pathology review: an effective strategy for epidemiology studies. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 14, 2213–2219 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wacholder S., Chanock S., Garcia-Closas M., El Ghormli L. and Rothman N. (2004) Assessing the probability that a positive report is false: an approach for molecular epidemiology studies. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 96, 434–442 10.1093/jnci/djh075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmitz R., Wright G.W., Huang D.W., Johnson C.A., Phelan J.D., Wang J.Q.. et al. (2018) Genetics and pathogenesis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 1396–1407 10.1056/NEJMoa1801445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lohr J.G., Stojanov P., Lawrence M.S., Auclair D., Chapuy B., Sougnez C.. et al. (2012) Discovery and prioritization of somatic mutations in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) by whole-exome sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 3879–3884 10.1073/pnas.1121343109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morin R.D., Mendez-Lago M., Mungall A.J., Goya R., Mungall K.L., Corbett R.D.. et al. (2011) Frequent mutation of histone-modifying genes in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Nature 476, 298–303 10.1038/nature10351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pasqualucci L., Trifonov V., Fabbri G., Ma J., Rossi D., Chiarenza A.. et al. (2011) Analysis of the coding genome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nat. Genet. 43, 830–837 10.1038/ng.892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J., Vlasevska S., Wells V.A., Nataraj S., Holmes A.B., Duval R.. et al. (2017) The CREBBP acetyltransferase is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor in B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Discov. 7, 322–337 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heinz S., Romanoski C.E., Benner C. and Glass C.K. (2015) The selection and function of cell type-specific enhancers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 144–154 10.1038/nrm3949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hnisz D., Abraham B.J., Lee T.I., Lau A., Saint-Andre V., Sigova A.A.. et al. (2013) Super-enhancers in the control of cell identity and disease. Cell 155, 934–947 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alizadeh A.A., Eisen M.B., Davis R.E., Ma C., Lossos I.S., Rosenwald A.. et al. (2000) Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature 403, 503–511 10.1038/35000501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monti S., Savage K.J., Kutok J.L., Feuerhake F., Kurtin P., Mihm M.. et al. (2005) Molecular profiling of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identifies robust subtypes including one characterized by host inflammatory response. Blood 105, 1851–1861 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lenz G., Wright G., Dave S.S., Xiao W., Powell J., Zhao H.. et al. (2008) Stromal gene signatures in large-B-cell lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 2313–2323 10.1056/NEJMoa0802885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davis R.E., Ngo V.N., Lenz G., Tolar P., Young R.M., Romesser P.B.. et al. (2010) Chronic active B-cell-receptor signalling in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nature 463, 88–92 10.1038/nature08638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ngo V.N., Young R.M., Schmitz R., Jhavar S., Xiao W., Lim K.H.. et al. (2011) Oncogenically active MYD88 mutations in human lymphoma. Nature 470, 115–119 10.1038/nature09671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giordano A. and Avantaggiati M.L. (1999) p300 and CBP: partners for life and death. J. Cell. Physiol. 181, 218–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giles R.H., Peters D.J. and Breuning M.H. (1998) Conjunction dysfunction: CBP/p300 in human disease. Trends Genet. 14, 178–183 10.1016/S0168-9525(98)01438-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gu W. and Roeder R.G. (1997) Activation of p53 sequence-specific DNA binding by acetylation of the p53 C-terminal domain. Cell 90, 595–606 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80521-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vervoorts J., Luscher-Firzlaff J.M., Rottmann S., Lilischkis R., Walsemann G., Dohmann K.. et al. (2003) Stimulation of c-MYC transcriptional activity and acetylation by recruitment of the cofactor CBP. EMBO Rep. 4, 484–490 10.1038/sj.embor.embor821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weaver B.K., Kumar K.P. and Reich N.C. (1998) Interferon regulatory factor 3 and CREB-binding protein/p300 are subunits of double-stranded RNA-activated transcription factor DRAF1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 1359–1368 10.1128/MCB.18.3.1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Juskevicius D., Jucker D., Klingbiel D., Mamot C., Dirnhofer S. and Tzankov A. (2017) Mutations of CREBBP and SOCS1 are independent prognostic factors in diffuse large B cell lymphoma: mutational analysis of the SAKK 38/07 prospective clinical trial cohort. J. Hematol. Oncol. 10, 70. 10.1186/s13045-017-0438-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andersen C.L., Asmar F., Klausen T., Hasselbalch H. and Gronbaek K. (2012) Somatic mutations of the CREBBP and EP300 genes affect response to histone deacetylase inhibition in malignant DLBCL clones. Leukemia Res. Rep. 2, 1–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]