Abstract

Keratin 18 (KRT18) has been suggested to be overexpressed in most types of human tumor, but the expression pattern of KRT18 in colorectal cancer (CRC) remained unknown. In our research, KRT18 protein expression was markedly increased in CRC cancer tissues and cell lines compared with adjacent normal colorectal tissues and normal colonic epithelial cell line, respectively. Meanwhile, we observed high KRT18 expression was associated with advanced clinical stage, deep tumor invasion, lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis, poor differentiation and unfavorable prognosis in CRC patients. Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed high expression of KRT18 was an unfavorable independent predictor for overall survival in CRC patients. The in vitro studies indicated down-regulation of KRT18 expression depressed CRC cell viability, migration and invasion. In conclusion, KRT18 serves as an oncogenic role in CRC progression and may be a therapeutic target for promoting CRC patients’ prognosis.

Keywords: biomarker, colorectal cancer, KRT18, prognosis

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide accounting for 1800977 newly diagnosed cases and 861663 deaths in 2018 [1]. Based on 2015 Cancer Statistics in China, CRC had a remarkable upward trend in age-standardized incidence rate, and became the fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in China with approximately 191000 deaths in 2015 [2]. CRC is significantly threatening public health in China [3]. Despite the significant improvements in molecular targeting therapy and immunotherapy, the 5-year survival rate for CRC patients with distant metastasis or recurrence remains dissatisfactory [4–7]. Therefore, it is urgently needed to consecutively elucidate the underlying mechanism and identify novel therapeutic targets for improving the clinical outcome of CRC patients.

Keratin 18 (KRT18) is a member of the intermediate filament family of cytoskeletal protein, which is essential for tissue integrity [8]. Originally, KRT18 expression was suggested in epithelial and endothelial cells from the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract [9]. Subsequently, KRT18 was found to be aberrantly expressed in various human malignancies and correlated with clinical progression and prognosis [10,11]. However, the clinical significance and biological function of KRT18 was seldom reported in CRC. Only one study showed that normal colon tissues exhibited higher KRT18 expression than colon adenomatous polyp or carcinoma tissues [12]. In our study, we first observed the KRT18 expression in CRC tissues and normal tissues at The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) databases [13], and found that KRT18 expression was significantly increased in colon cancer tissues and rectal cancer compared with corresponding normal tissues. Then, high expression of KRT18 was confirmed in CRC tissues and cell lines in our study, and found to be associated with malignant status in CRC patients. Survival analyses indicated that CRC patients with high KRT18 expression had shorter overall survival time than those with low KRT18 expression, and high KRT18 expression acted as an independent prognostic predictor for overall survival in CRC patients. Finally, the in vitro experiments revealed inhibition of KRT18 expression depressed CRC cell viability, migration and invasion.

Materials and methods

Database analysis

TCGA database (275 colon cancer tissues and 41 normal tissues; 92 rectal cancer tissues and 10 normal tissues) and GTEx database (308 normal tissues) were used for data analysis. In addition, analysis of TCGA and GTEx databases was performed at the GEPIA (Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis, http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/) platform.

Clinical tissue specimens

One hundred and twelve patients with CRC in the present study received surgery or biopsy in The Affiliated Hospital of Jining Medical University or Zhoucheng People’s Hospital. The following samples were obtained and paraffin-embedded: adjacent normal colorectal tissues (n=36) and CRC tissues (n=108), which were applied to immunohistochemistry. None of the CRC cases had received anti-tumor treatment prior to pathologic diagnosis. The adjacent normal colorectal tissues were acquired from 5 cm over the margin of tumor tissues. Histopathologic examination of each tissue was verified by two pathologists. The clinical stage was determined based on 7th edition the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system.

Immunohistochemistry

The 4-μm-thick CRC sections were subjected to routine deparaffinization and rehydration. Antigen retrieval was accomplished by incubating the sections in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer for 10 min and microwaving the sections for 20 min. Then, the sections were treated with 0.3% H2O2 for inhibition of endogenous peroxidase activity, and incubated with 5% nonfat dried milk for blocking of nonspecific binding. After washing, the sections were incubated with anti-KRT18 antibody (1:250 dilution, catalog ab133263, Abcam, U.S.A.) at 4°C overnight, and biotinylated secondary antibody (1:2000 dilution, Beyotime, China) for 90 min. Phosphate buffered saline was used instead of a primary antibody as a negative control. Subsequently, the sections were incubated with ABC solution for 30 min, and treated with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) for 5 min. After Hematoxylin counterstain, the sections were dehydrated and sealed.

The KRT18 staining was scored by combining the percentage of positive tumor cells and the intensity of the staining. The percentage of positive tumor cells was scored as 0 (no staining), 1 (<10%), 2 (10–50%), 3 (50–80%) and 4 (>80%). The staining intensity was scored as 0 (no staining), 1 (weak), 2 (moderate), and 3 (strong). The final score was obtained by multiplying the score of staining intensity and the score of positive tumor cells. The CRC cases were divided into two groups: low KRT18 expression group (score 0–6) and high KRT18 expression group (score 8–12).

Cell lines

The human normal colonic epithelial cell line (NCM460) and four human CRC cell lines (HT29, HCT116, SW480, SW620) were purchased from Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) and cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 medium (Gibco, U.S.A.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, U.S.A.) at an incubator with an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 37°C.

Cell transfection

The siRNA for KRT18 (si-KRT18) and negative control (si-NC) were designed and synthesized by Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). The si-KRT18 or si-NC was transfected into CRC cells by using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, U.S.A.) according to the protocol of the manufacturer. The depletion of KRT18 by siRNA treatment was confirmed by Western blot after transfection with 72 h. The CRC cells were collected after 48 h transfection for the following assays in vitro.

Cell counting kit-8 assay

CRC cells (2 × 103 cells per well) were seeded in 96-well plates, and cultured for 24, 72, and 120 h. Then, cell counting kit-8 (CCK8) solutions were added in each well and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The optical density (OD) of each was detected via a microplate reader at 450 nm. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Cell migration and invasion assays

Cell migration and invasion assays were performed by trawnswell chamber (8-μm pore size, Corning, U.S.A.). For cell invasion assay, the transwell chamber was coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences, U.S.A.). CRC cells (1 × 105 cells/well) were resuspended in serum-free RPMI-1640 medium, and seeded in the upper well of the transwell chamber. The lower well of the transwell chamber was filled with RPMI-1640 medium containing 20% FBS. After culturing for 24 h, the filter inserts were removed from the chambers, and fixed with methanol and stained with Crystal Violet. Finally, the number of cells was counted in five random fields under a microscope. All assays were independently repeated at least three times.

Western blot

CRC cells were crushed in lysis buffer (Beyotime, China) according to the protocol of the manufacturer. Equal amount of proteins were verified by BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime, China), separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate/polyacrylamide gel and electroblotted on to polyvinyl difluoride membranes (Millipore, U.S.A.). Then, the membrane was immunoblotted overnight at 4°C with primary antibody against human KRT18 (1:100 dilution; catalog ab133263, Abcam, U.S.A.), and incubated with 1:3000 horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody (Beyotime, China). The enhanced chemiluminescence system (Beyotime, China) was used to detect the signal. The bands were obtained and quantified by Quantity One (Bio-Rad, U.S.A.). Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. SPSS version 22.0 software (IBM Corporation, NY, U.S.A.) was used to analyze all results. The difference between two groups was assessed by the independent two-tailed Student’s t test. Chi-square test was used to estimate correlations between KRT18 expression and clinicopathological characteristics of CRC patients. Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test were used to evaluate the overall survival difference between high KRT18 expression group and low KRT18 expression group. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to assess potential factors for predicting overall survival in CRC patients. A value of P<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

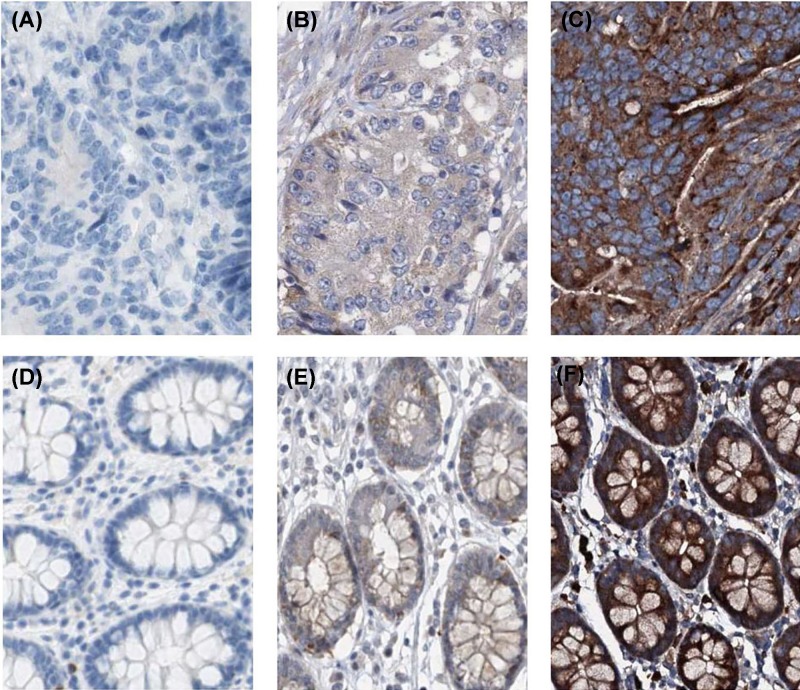

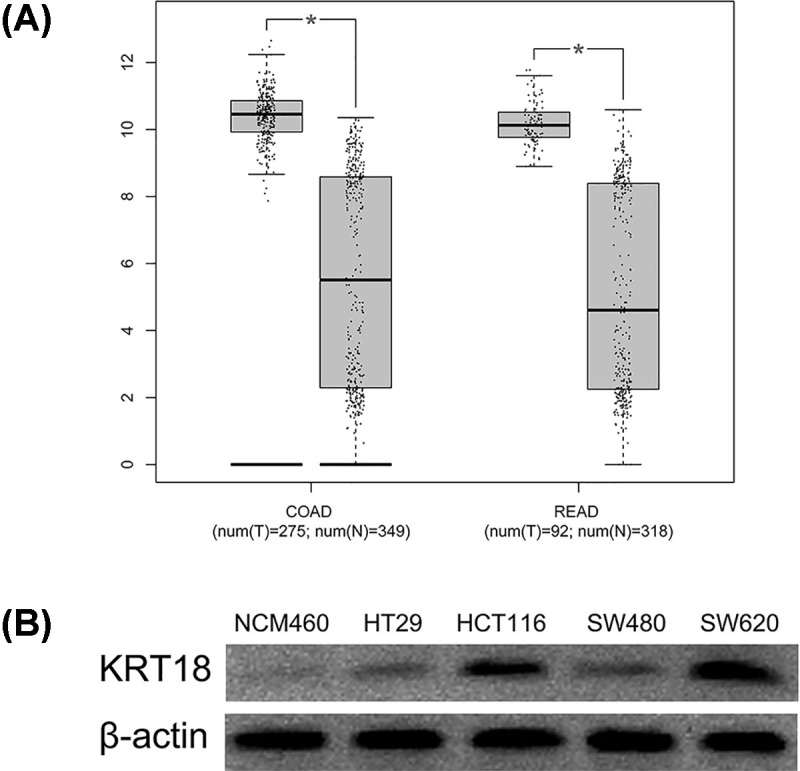

KRT18 expression is increased in CRC tissues and cell lines

For exploring the expression pattern of KRT18 in CRC, we first observed KRT18 expression in TCGA and GTEx databases, and found levels of KRT18 expression were dramatically increased in colon cancer and rectal cancer tissues compared with corresponding normal tissues (both P<0.001, Figure 1A). Furthermore, we conducted immunohistochemistry to detect the KRT18 expression in CRC tissues and normal colorectal tissues (Figure 2A–F). KRT18 showed high expression in the cytoplasm of cells. The results of immunohistochemistry showed high KRT18 staining was observed in 62 of 108 CRC tissues (57.4%) and 10 of 36 normal colorectal tissues (27.8%). The statistical analysis indicated that there was significant difference in KRT18 staining between CRC tissues and normal colorectal tissues (P=0.002, Table 1), which was similar to the result of TCGA database. Moreover, the expression of KRT18 was also measured in the human normal colonic epithelial cell line (NCM460) and four human CRC cell lines (HT29, HCT116, SW480, SW620) through Western blot. The result of Western blot revealed that overexpression of KRT18 was observed in all human CRC cell lines compared with human normal colonic epithelial cell line (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. KRT18 expression is increased in CRC tissues and cell lines.

(A) Levels of KRT18 expression were dramatically increased in colon cancer and rectal cancer tissues compared with corresponding normal tissues. (B) KRT18 was observed in all human CRC cell lines compared with human normal colonic epithelial cell line. *P<0.001

Figure 2. The immunohistochemical KRT18 staining in CRC tissues.

(A) Negative KRT18 expression in CRC tissues. (B) Low cytoplasmic KRT18 expression in CRC tissues. (C) High cytoplasmic KRT18 expression in CRC tissues. (D) Negative KRT18 expression in normal colorectal tissues. (E) Low cytoplasmic KRT18 expression in normal colorectal tissues. (F) High cytoplasmic KRT18 expression in normal colorectal tissues.

Table 1. KRT18 protein expression between CRC tissues and adjacent normal tissues.

| Group | Cases | High KRT18 expression | Low KRT18 expression | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor tissues | 108 | 62 | 46 | 0.002 |

| Normal tissues | 36 | 10 | 26 |

KRT18 expression is related with clinical progression in CRC patients

For exploring the clinical significance of KRT18 expression in CRC patients, the relationship between KRT18 expression and clinicopathological characteristics were estimated by Chi-square test. As shown in Table 2, high KRT18 expression associated with clinical stage (P=0.003, Table 2), tumor invasion depth (P=0.009, Table 2), lymph node metastasis (P=0.008, Table 2), distant metastasis (P=0.001, Table 2), and degree of differentiation (P=0.005, Table 2), but had no significant association with gender (P=0.082, Table 2), age (P=0.862, Table 2), family history (P=0.447, Table 2), and location (P=0.083, Table 2).

Table 2. Correlations between KRT18 expression and clinicopathological characteristics in CRC patients.

| Characteristics | n | High KRT18 expression | Low KRT18 expression | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| <50 | 48 | 28 | 20 | 0.862 |

| ≥50 | 60 | 34 | 26 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 37 | 17 | 20 | 0.082 |

| Male | 71 | 45 | 26 | |

| Clinical stage | ||||

| I–II | 33 | 12 | 21 | 0.003 |

| III–IV | 75 | 50 | 25 | |

| Tumor invasion depth | ||||

| T1–T2 | 50 | 22 | 28 | 0.009 |

| T3–T4 | 58 | 40 | 18 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||

| N0–N1 | 43 | 18 | 25 | 0.008 |

| N2 | 65 | 44 | 21 | |

| Distant metastasis | ||||

| M0 | 96 | 50 | 46 | 0.001 |

| M1 | 12 | 12 | 0 | |

| Degree of differentiation | ||||

| High or Middle | 68 | 32 | 36 | 0.005 |

| Low | 40 | 30 | 10 | |

| Family history | ||||

| No | 88 | 49 | 39 | 0.447 |

| Yes | 20 | 13 | 7 | |

| Location | ||||

| Colon | 62 | 40 | 22 | 0.083 |

| Rectum | 46 | 22 | 24 |

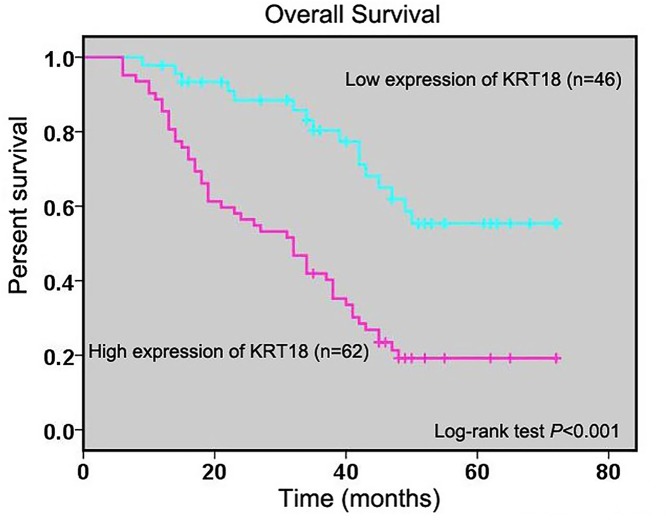

KRT18 expression is related with prognosis in CRC patients

To explore the influence of KRT18 expression on CRC patients’ overall survival, we analyzed the relationship between KRT18 expression and overall survival time of CRC patients. Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test showed KRT18 expression was negatively related to overall survival time of CRC patients (P<0.001, Figure 3). Moreover, univariate Cox regression analysis revealed that clinical stage (P=0.004, Table 3), tumor invasion depth (P=0.022, Table 3), lymph node metastasis (P=0.009, Table 3), distant metastasis (P<0.001, Table 3), family history (P=0.042, Table 3), and KRT18 expression (I–IIA vs. IIB–IV, P<0.001, Table 3) were prognostic factors for CRC patients. Furthermore, high expression of KRT18 was found to be an unfavorable independent predictor of overall survival in CRC patients at multivariate Cox regression analysis (P=0.010, Table 3).

Figure 3. KRT18 expression is related with prognosis in CRC patients.

Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test were analyzed the relationship between KRT18 expression and overall survival time of CRC patients.

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate cox regression of prognostic factors for overall survival in CRC patients.

| Parameter | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| (<50 vs. ≥50) | 0.592 | 0.363–0.965 | 0.035 | 0.688 | 0.415–1.142 | 0.148 |

| Gender | ||||||

| (Female vs. Male) | 1.687 | 0.979–2.908 | 0.060 | 1.332 | 0.726–2.446 | 0.354 |

| Clinical stage | ||||||

| (I–II vs. III–IV) | 2.403 | 1.318–4.382 | 0.004 | 1.320 | 0.488–3.570 | 0.585 |

| Tumor invasion depth | ||||||

| (T1–T2 vs. T3–T4) | 1.803 | 1.088–2.989 | 0.022 | 1.205 | 0.677–2.143 | 0.527 |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||||

| (N0–N1 vs. N2) | 2.015 | 1.188–3.416 | 0.009 | 1.243 | 0.502–3.077 | 0.638 |

| Distant metastasis | ||||||

| (M0 vs. M1) | 4.010 | 2.031–7.917 | <0.001 | 1.871 | 0.850–4.121 | 0.120 |

| Degree of differentiation | ||||||

| (High or Middle vs. Low) | 1.388 | 0.846–2.277 | 0.194 | 0.829 | 0.445–1.543 | 0.554 |

| Family history | ||||||

| (No vs. Yes) | 1.829 | 1.024–3.270 | 0.042 | 1.654 | 0.814–3.363 | 0.164 |

| Location | ||||||

| (Colon vs. Rectum) | 1.002 | 0.607–1.653 | 0.994 | 0.964 | 0.524–1.774 | 0.906 |

| KRT18 expression | ||||||

| (Low vs. High) | 3.315 | 1.877–5.854 | <0.001 | 2.377 | 1.230–4.597 | 0.010 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

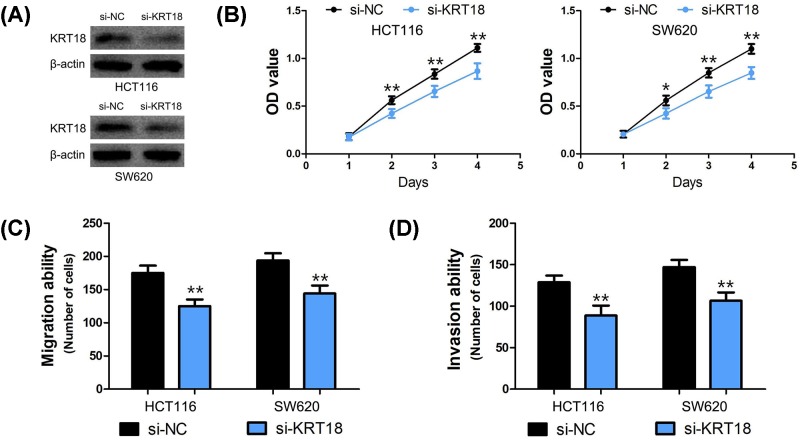

Silencing of KRT18 expression inhibits CRC cell viability, migration, and invasion

To explore the biological role of KRT18 in CRC cells, we performed loss-of-function studies through si-KRT18 in HCT116 and SW620 cells (Figure 4A). The CCK8 assay suggested that the viability of HCT116 and SW620 cells was suppressed after KRT18 silencing (P<0.01, Figure 4B). Moreover, the results of cell migration and invasion assays demonstrated that the migratory and invasive abilities of HCT116 and SW620 cells were inhibited by KRT18 knockdown (P<0.001, Figure 4C,D).

Figure 4. Silencing of KRT18 expression inhibits CRC cell proliferation, migration and invasion.

(A) The depletion of KRT18 by siRNA treatment was confirmed by Western blot in HCT116 and SW620 cells. (B) The proliferation of HCT116 and SW620 cells was strikingly suppressed after KRT18 silencing. (C,D) The migratory and invasive abilities of HCT116 and SW620 cells were dramatically inhibited by KRT18 knockdown. (*: P<0.01, **: P<0.001)

Discussion

KRT18 is a type I intermediate filament protein that extends from the surface of the nucleus to the cell membrane, and involved in a variety of cellular processes including cell proliferation, cell cycle, apoptosis, motility, and cell signaling [14]. In recent decade, KRT18 was suggested to be up-regulated in various human tumor tissues including lung cancer [15], invasive breast cancer [16], esophageal cancer [17], gastric cancer [18], hepatocellular carcinoma [19], bladder cancer [20], ovarian cancer [21], oral squamous cell carcinoma [22], pancreatic cancer [23], prostate cancer [24], and so on. Drew et al. [12]performed multivariate discriminant analysis on the hCellMarkerPlex gene expression data including human colon normal tissues, colon adenomatous polyp tissues and colon carcinoma tissues, and found that colon normal tissues had significantly low KRT18 expression compared with colon adenomatous polyp tissues and colon carcinoma tissues. In our study, we further found that KRT18 protein expression was increased in CRC cancer tissues and cell lines. Generally, KRT18 is overexpressed in most types of human cancer.

We further investigated the clinical significance of KRT18, and observed high KRT18 expression was positively associated with clinical stage, tumor invasion depth, lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis, and degree of differentiation. In lung cancer patients, KRT18 expression was suggested to be correlated with clinical lymph node metastasis [25]. In addition, KRT18 expression had 4.6-times increase in high metastatic lung cancer cell line compared with low metastatic lung cancer cell line [26]. In hepatocellular carcinoma patients, levels of KRT18 expression were positively correlated with lymph node metastasis and aggressive phenotype [27,28]. Moreover, Afrem et al. [29] reported KRT18 overexpression was correlated with advanced clinical stage, poor differentiation, and high invasion pattern in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. In bladder cancer, Wild et al. [20] and Catto et al. [30] conformably found KRT18 served as one of artificial intelligence-selected genes for predicting clinical progression. Moreover, Yin et al. [31] suggested high expression of KRT18 was associated with tumor aggressiveness and paclitaxel resistance in prostate cancer patients. In breast cancer, Chalabi et al. [32] revealed that high expression of KRT18 often observed in luminal B patients from Lebanon, Tunisia, and Morocco, and in luminal A patients from France. Besides, Kilic-Baygutalp et al. [17] found KRT18 expression was positively associated with clinical stage, tumor stage, and metastasis stage in patients with esophageal cancer. In gastric cancer, high KRT18 expression was suggested to be associated with positive lymph nodes, advanced clinical stage, and chemoresistance [33,34].

The prognostic significance of KRT18 is still not well understood in human tumors. Zhang et al. [35] reported that KRT18 overexpression was correlated with short overall survival and disease-free survival in lung cancer patients. In hepatocellular carcinoma patients, KRT18 overexpression served as an unfavorable prognostic predictor for 1-year survival [36]. Moreover, Yang et al. [37] found positive KRT8/18 was an independent prognostic factor for overall survival in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. In nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients, Huang et al. [38] showed high expression of KRT18 had high specificity for predicting poor prognosis. However, Morisaki et al. [39] indicated that KRT18 expression had no relationship with overall survival time in gastric cancer patients. There was no report about the prognostic significance of KRT18 in CRC patients. In our study, we also found KRT18 overexpression acted as an unfavorable independent predictor of overall survival in CRC patients.

In past decades, KRT18 has been found to function as oncogenic lncRNA in several types of human malignancy. In lung cancer cells, Zhang et al. [35] showed down-regulation of KRT18 that inhibited cell migration and elevated the sensitivity to paclitaxel. In addition, down-regulation of KRT18 was found to depress epithelial cancer cell motility, invasion, and cisplatin sensitivity [11]. In hepatocellular carcinoma, KRT18 deficiency accelerated liver tumor development [40]. In CRC cells, we observed silencing of KRT18 expression inhibited CRC cell viability, migration, and invasion. In colonic epithelial cells, Lähdeniemi et al. [41] found KRT18 interacted with Notch1 and regulate Notch1 signalling activity. Unfortunately, we did not further explore the molecular mechanism of KRT18 in CRC due to limited research fund. However, Zhang et al. [25] reported that KRT18 expression was directly regulated by EGR1, which has been showed to function as a tumor suppressor in lung cancer. Moreover, Fortier et al. [11] found knockdown of KRT18 led to PI3K/Akt/NF-κB hyperactivation and elevated MMP2 and MMP9 expression, but no had effects on epithelial–mesenchymal transition markers. Meanwhile, knockdown of KRT18 was elevated Fas receptor membrane targeting in a claudin1-dependent manner, thus enhancing the activation of the extrinsic apoptosis pathway [11]. Therefore, more studies would be needed to explore and verify the role of KRT18 in tumorigenesis.

In conclusion, KRT18 is overexpressed in CRC tissues and cell lines, and associated with tumor progression and overall survival. Down-regulation of KRT18 expression depresses CRC cell viability, migration, and invasion in vitro.

Abbreviations

- CCK8

cell counting kit-8

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GTEx

The Genotype-Tissue Expression

- KRT18

Keratin 18

- MMP

matrix metalloprotein

- RPMI

Roswell Park Memorial Institute

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

Ethical Statement

The present study was reviewed and approved by The Ethics Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Jining Medical University or Zhoucheng People’s Hospital, and has been carried out in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was signed from all CRC patients.

Author Contributions

Yansen Li: study concept and design, interpretation of data, and review of the manuscript. Jingfeng Zhang and Sifeng Hu: execution experiment and statistical analysis.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that there are no sources of funding to be acknowledged.

References

- 1.Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R.L., Torre L.A. and Jemal A. (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68, 394–424 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W., Zheng R., Baade P.D., Zhang S., Zeng H., Bray F.. et al. (2016) Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J. Clin. 66, 115–132 10.3322/caac.21338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y., Shi J., Huang H., Ren J., Li N. and Dai M. (2015) Burden of colorectal cancer in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 36, 709–714 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seeber A. and Gastl G. (2016) Targeted therapy of colorectal cancer. Oncol. Res. Treat. 39, 796–802 10.1159/000453027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohhara Y., Fukuda N., Takeuchi S., Honma R., Shimizu Y., Kinoshita I.. et al. (2016) Role of targeted therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 8, 642–655 10.4251/wjgo.v8.i9.642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yaghoubi N., Soltani A., Ghazvini K., Hassanian S.M. and Hashemy S.I. (2019) PD-1/ PD-L1 blockade as a novel treatment for colorectal cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 110, 312–318 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.11.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilt C. and Le D.T. (2018) Integrating immunotherapy into colorectal cancer care. Oncology (Williston Park) 32, 494–498 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lebherz-Eichinger D., Krenn C.G. and Roth G.A. (2013) Keratin 18 and heat-shock protein in chronic kidney disease. Adv. Clin. Chem. 62, 123–149 10.1016/B978-0-12-800096-0.00003-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koehler D.R., Hannam V., Belcastro R., Steer B., Wen Y., Post M.. et al. (2001) Targeting transgene expression for cystic fibrosis gene therapy. Mol. Ther. 4, 58–65 10.1006/mthe.2001.0412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai Y.C., Cheng C.C., Lai Y.S. and Liu Y.H. (2017) Cytokeratin 18-associated histone 3 modulation in hepatocellular carcinoma: a mini review. Cancer Genomics Proteomics 14, 219–223 10.21873/cgp.20033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fortier A.M., Asselin E. and Cadrin M. (2013) Keratin 8 and 18 loss in epithelial cancer cells increases collective cell migration and cisplatin sensitivity through claudin1 up-regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 11555–11571 10.1074/jbc.M112.428920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drew J.E., Farquharson A.J., Mayer C.D., Vase H.F., Coates P.J., Steele R.J.. et al. (2014) Predictive gene signatures: molecular markers distinguishing colon adenomatous polyp and carcinoma. PLoS ONE 9, e113071. 10.1371/journal.pone.0113071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Cancer Genome Atlas Network (2012) Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 487, 330–337 10.1038/nature11252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Owens D.W. and Lane E.B. (2004) Keratin mutations and intestinal pathology. J. Pathol. 204, 377–385 10.1002/path.1646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagashio R., Sato Y., Matsumoto T., Kageyama T., Satoh Y., Ryuge S.. et al. (2010) Significant high expression of cytokeratins 7, 8, 18, 19 in pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas, compared to small cell lung carcinomas. Pathol. Int. 60, 71–77 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2009.02487.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doebar S.C., Sieuwerts A.M., De Weerd V., Stoop H., Martens J.W.M. and Van Deurzen C.H.M. (2017) Gene expression differences between ductal carcinoma in situ with and without progression to invasive breast cancer. Am. J. Pathol. 187, 1648–1655 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilic-Baygutalp N., Ozturk N., Orsal-Ibisoglu E., Gundogdu B., Ozgeris F.B., Bakan N.. et al. (2016) Evaluation of serum HGF and CK18 levels in patients with esophageal cancer. Genet Mol Res 15, 10.4238/gmr.15038583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu W., Zhang M.W., Huang J., Wang X., Xu S.F., Li Y.. et al. (2005) Correlation between CK18 gene and gastric carcinoma micrometastasis. World J. Gastroenterol. 11, 6530–6534 10.3748/wjg.v11.i41.6530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akiba J., Nakashima O., Hattori S., Naito Y., Kusano H., Kondo R.. et al. (2016) The expression of arginase-1, keratin (K) 8 and K18 in combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma, subtypes with stem-cell features, intermediate-cell type. J. Clin. Pathol. 69, 846–851 10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wild P.J., Catto J.W., Abbod M.F., Linkens D.A., Herr A., Pilarsky C.. et al. (2007) Artificial intelligence and bladder cancer arrays. Verh. Dtsch. Ges. Pathol. 91, 308–319 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolostova K., Pinkas M., Jakabova A., Pospisilova E., Svobodova P., Spicka J.. et al. (2016) Molecular characterization of circulating tumor cells in ovarian cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 6, 973–980 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamauchi K., Fujioka Y., Kogashiwa Y. and Kohno N. (2011) Quantitative expression study of four cytokeratins and p63 in squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue: suitability for sentinel node navigation surgery using one-step nucleic acid amplification. J. Clin. Pathol. 64, 875–879 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walsh N., O’donovan N., Kennedy S., Henry M., Meleady P., Clynes M.. et al. (2009) Identification of pancreatic cancer invasion-related proteins by proteomic analysis. Proteome Sci. 7, 3. 10.1186/1477-5956-7-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santamaria L., Ingelmo I., Sinues B., Martinez L. and Teba F. (2018) Quantification of the heterogeneity of cytokeratin 18 immunoexpression in prostate adenocarcinoma and normal prostate: Global and local features. Histol. Histopathol. 33, 1099–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H., Chen X., Wang J., Guang W., Han W., Zhang H.. et al. (2014) EGR1 decreases the malignancy of human non-small cell lung carcinoma by regulating KRT18 expression. Sci. Rep. 4, 5416. 10.1038/srep05416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J., Zhong X., Li J., Liu B., Guo S., Chen J.. et al. (2012) Screening and identification of lung cancer metastasis-related genes by suppression subtractive hybridization. Thorac. Cancer 3, 207–216 10.1111/j.1759-7714.2011.00092.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golob-Schwarzl N., Bettermann K., Mehta A.K., Kessler S.M., Unterluggauer J., Krassnig S.. et al. (2019) High keratin 8/18 ratio predicts aggressive hepatocellular cancer phenotype. Transl. Oncol. 12, 256–268 10.1016/j.tranon.2018.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee C.F., Ling Z.Q., Zhao T., Fang S.H., Chang W.C., Lee S.C.. et al. (2009) Genomic-wide analysis of lymphatic metastasis-associated genes in human hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 15, 356–365 10.3748/wjg.15.356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Afrem M.C., Craitoiu S., Hincu M.C., Manolea H.O., Nicolae V. and Craitoiu M.M. (2016) Study of CK18 and GDF5 immunoexpression in oral squamous cell carcinoma and their prognostic value. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 57, 167–172 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Catto J.W., Abbod M.F., Wild P.J., Linkens D.A., Pilarsky C., Rehman I.. et al. (2010) The application of artificial intelligence to microarray data: identification of a novel gene signature to identify bladder cancer progression. Eur. Urol. 57, 398–406 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yin B., Zhang M., Zeng Y., Li Y., Zhang C., Getzenberg R.H.. et al. (2016) Downregulation of cytokeratin 18 is associated with paclitaxelresistance and tumor aggressiveness in prostate cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 48, 1730–1736 10.3892/ijo.2016.3396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chalabi N., Bernard-Gallon D.J., Bignon Y.J., Breast Med C., Kwiatkowski F., Agier M.. et al. (2008) Comparative clinical and transcriptomal profiles of breast cancer between French and South Mediterranean patients show minor but significative biological differences. Cancer Genomics Proteomics 5, 253–261 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peduk S., Tatar C., Dincer M., Ozer B., Kocakusak A., Citlak G.. et al. (2018) The role of serum CK18, TIMP1, and MMP-9 levels in predicting R0 resection in patients with gastric cancer. Dis. Markers 2018, 5604702. 10.1155/2018/5604702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagel M., Schulz J., Maderer A., Goepfert K., Gehrke N., Thomaidis T.. et al. (2018) Cytokeratin-18 fragments predict treatment response and overall survival in gastric cancer in a randomized controlled trial. Tumour Biol. 40, 1010428318764007. 10.1177/1010428318764007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang B., Wang J., Liu W., Yin Y., Qian D., Zhang H.. et al. (2016) Cytokeratin 18 knockdown decreases cell migration and increases chemosensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 142, 2479–2487 10.1007/s00432-016-2253-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lorente L., Rodriguez S.T., Sanz P., Perez-Cejas A., Padilla J., Diaz D.. et al. (2016) Prognostic value of serum caspase-cleaved cytokeratin-18 levels before liver transplantation for one-year survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, pii: E1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Z.Y., Zhang H.Y., Wang F., Ma Y.H., Li Y.Y., He H.L.. et al. (2018) Expression of cytokeratin(CK)7, CK8/18, CK19 and p40 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and their correlation with prognosis. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi 47, 834–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang S., Li S., Peng T., Wu T., Song P. and Zhou X. (2015) Detection of cytokeratin18 and cytokeratin19 gene expression in blood and tumor tissue of nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients by RT-PCR. Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi 29, 111–113, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morisaki T., Yashiro M., Kakehashi A., Inagaki A., Kinoshita H., Fukuoka T.. et al. (2014) Comparative proteomics analysis of gastric cancer stem cells. PLoS ONE 9, e110736. 10.1371/journal.pone.0110736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bettermann K., Mehta A.K., Hofer E.M., Wohlrab C., Golob-Schwarzl N., Svendova V.. et al. (2016) Keratin 18-deficiency results in steatohepatitis and liver tumors in old mice: a model of steatohepatitis-associated liver carcinogenesis. Oncotarget 7, 73309–73322 10.18632/oncotarget.12325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lahdeniemi I.A.K., Misiorek J.O., Antila C.J.M., Landor S.K., Stenvall C.A., Fortelius L.E.. et al. (2017) Keratins regulate colonic epithelial cell differentiation through the Notch1 signalling pathway. Cell Death Differ. 24, 984–996 10.1038/cdd.2017.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]