ABSTRACT

Background

Western diets may provide excess vitamin A, which is potentially toxic and could adversely affect respiratory health and counteract benefits from vitamin D.

Objective

The aim of this study was to examine child asthma at age 7 y in relation to maternal intake of vitamins A and D during pregnancy, infant supplementation with these vitamins, and their potential interaction.

Design

We studied 61,676 school-age children (born during 2002–2007) from the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort with data on maternal total (food and supplement) nutrient intake in pregnancy (food-frequency questionnaire validated against biomarkers) and infant supplement use at age 6 mo (n = 54,142 children). Linkage with the Norwegian Prescription Database enabled near-complete follow-up (end of second quarter in 2015) for dispensed medications to classify asthma. We used log-binomial regression to calculate adjusted RRs (aRRs) for asthma with 95% CIs.

Results

Asthma increased according to maternal intake of total vitamin A [retinol activity equivalents (RAEs)] in the highest (≥2031 RAEs/d) compared with the lowest (≤779 RAEs/d) quintile (aRR: 1.21; 95% CI: 1.05, 1.40) and decreased for total vitamin D in the highest (≥13.6 µg/d) compared with the lowest (≤3.5 µg/d) quintile (aRR: 0.81; 95% CI: 0.67, 0.97) during pregnancy. No association was observed for maternal intake in the highest quintiles of both nutrients (aRR: 0.99; 95% CI: 0.83, 1.18) and infant supplementation with vitamin D or cod liver oil.

Conclusions

Excess vitamin A (≥2.5 times the recommended intake) during pregnancy was associated with increased risk, whereas vitamin D intake close to recommendations was associated with a reduced risk of asthma in school-age children. No association for high intakes of both nutrients suggests antagonistic effects of vitamins A and D. This trial was registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov as NCT03197233.

Keywords: food-frequency questionnaire, dietary supplements, pregnant women, infants, vitamin A, vitamin D, pediatric asthma, prescriptions, Norwegian Prescription Database, Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is currently among the top 5 chronic conditions contributing to the global burden of disease in children aged 5–14 y (1). Unfavorable changes in diet have been hypothesized to increase the susceptibility to asthma (2) and dietary exposures in utero and infancy could play a role, in particular for childhood onset of the disease (3).

Fat-soluble vitamins have a broad range of effects related to antioxidant properties (4), immune function (5), and lung development (6). In particular, vitamin D has attracted much interest because of widespread deficiency in Western populations (7). Studies that used Mendelian randomization do not support that genetically lowered 25-hydroxyvitamin D is a risk factor for asthma (8). However, randomized trials (9, 10) and a meta-analysis of birth cohort studies (11) suggest that prenatal vitamin D supplementation above the regular dose (9, 10), and higher maternal circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D (11), may reduce the susceptibility to asthma in the offspring, although follow-up of children to school age is not yet available in the trials.

Vitamin A deficiency poses a public health problem in parts of the world, but westernized diets may provide excess vitamin A (12–14) from increasing intakes of animal products and fortified foods and the use of dietary supplements. High dietary vitamin A has been associated with increased asthma severity in a murine model (15), but human studies are limited by potential toxic effects and a lack of feasible biomarkers for assessing adequate or subtoxic status (16). Observational studies, rather than trials, are therefore important to examine unintended health effects of vitamin A excess at the population level. Previous observational studies of vitamin A and asthma have mainly focused on the antioxidant properties of carotenoids (3) and have not included retinol, the most potent form of vitamin A. Vitamin A supplementation trials have been conducted in areas with endemic deficiency (17, 18) where the effects on respiratory outcomes could differ from those in well-nourished populations due to differences in baseline vitamin A status (19). Few studies, to our knowledge, have examined the risk of child asthma in relation to prenatal concentrations of vitamin A, including retinol, outside of deficient populations (20, 21) or the importance of prenatal compared with early postnatal exposure. Furthermore, high vitamin A intake could potentially counteract the beneficial effects of vitamin D, due to competition for the nuclear retinoid X receptor (22).

Our objective was to investigate the association of maternal intakes of vitamins A and D during pregnancy, infant exposure to dietary supplements containing these nutrients, and potential nutrient interaction, with current asthma at school age when the diagnosis is more reliable than at earlier ages. Norway offers advantages for the study of high intakes of vitamin A during pregnancy because of a generally high intake from food sources in addition to the widespread use of cod liver oil as a dietary supplement.

METHODS

Study population

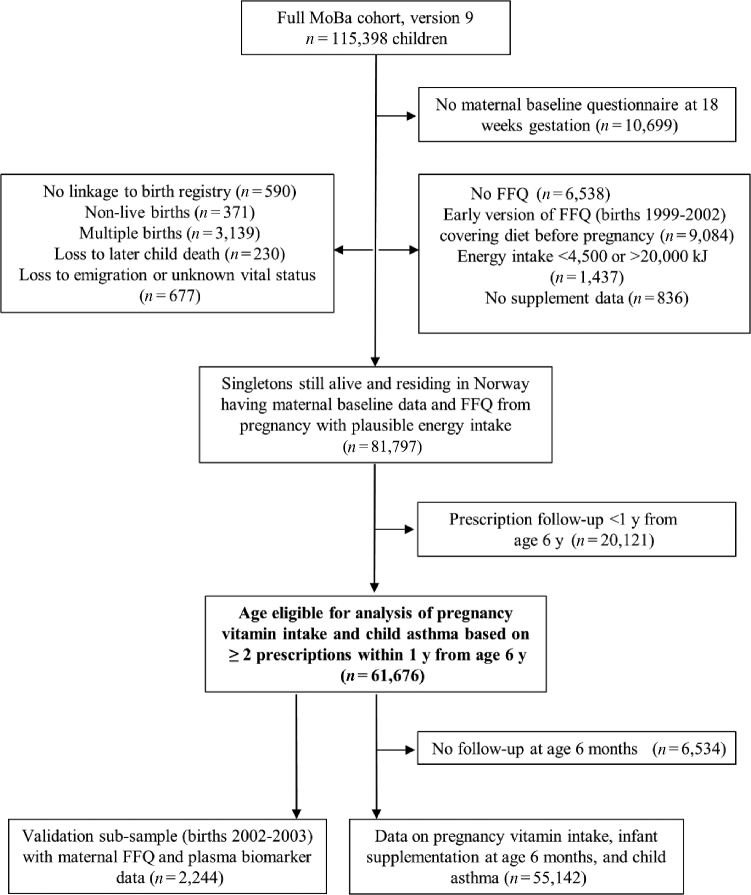

The study included participants in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa), a population-based pregnancy cohort (births during 1999–2009) administered by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (23, 24). Women were recruited nationwide (41% participation) at ∼18 wk of gestation when a prenatal screening is offered to all pregnant women. For the current study we linked MoBa file version 9 (115,398 children and 95,248 mothers) with the Medical Birth Registry of Norway (hereafter referred to as the birth registry) and the Norwegian Prescription Database (NorPD), with follow-up to the end of the second quarter of 2015. The current study was registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov as NCT03197233. Eligible children (Figure 1) had available data on maternal dietary intake in pregnancy from a validated food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ) administered at ∼20 gestational weeks and prescription follow-up for ≥12 mo from age 6 y (n = 61,676; born 2002–2007), of whom 89% (n = 55,142) had data on infant supplement use at 6 mo. We used a random subsample of 2244 births from 2002–2003 to compare maternal dietary intake with plasma concentrations of fat-soluble vitamins at 18 gestational weeks.

FIGURE 1.

Sample selection and eligibility criteria. FFQ, food-frequency questionnaire; MoBa, Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study.

Ethical approval

The MoBa study has been approved by the Norwegian Data Inspectorate (reference 01/4325) and the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics (refererence S-97045, S-95). All of the participants gave written informed consent at the time of enrollment. The current study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics of South/East Norway.

Dietary exposure assessment and biomarker comparisons

Total (food and supplement) nutrient intakes during pregnancy were estimated from the FFQ, which queried about intake since becoming pregnant. The FFQ has been validated against a 4-d weighed food diary and with selected biomarkers (25, 26). Total vitamin A (sum of total retinol and total β-carotene) was expressed as daily retinol activity equivalents (RAEs) per day by using the conversion factors 1 μg retinol (from diet or supplements) = 12 μg β-carotene from diet = 2 μg β-carotene from supplements to account for differences in bioavailability (27). Total vitamin D (micrograms per day) included vitamin D3 from foods and vitamins D2 and D3 from supplements. Nutrient intake was calculated by using the Norwegian Food Composition Table (28) and a compiled database of dietary supplements, mainly based on the manufacturers’ information. Maternal plasma retinol and 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 and D3 were measured at Bevital AS laboratories in Bergen, Norway (www.bevital.no), in a single, nonfasting venous blood sample drawn at ∼18 wk of gestation. The frequency of infant supplement use (never, sometimes, or daily) was assessed from a follow-up questionnaire mailed at 6 mo of age. We analyzed the use of the following supplement categories containing vitamins A or D or both: vitamin D only (liquid oil-based formula), cod liver oil, multivitamins, and any vitamin D supplement, excluding multivitamins. The latter category included vitamin D only, cod liver oil, and less common supplements (fish oil with added vitamin D, liquid vitamin A and vitamin D formula, vitamin D with fluoride, and other vitamin D combinations).

Outcome measures of children's asthma

We examined current asthma in children at ∼7 y of age, defined as having ≥2 pharmacy dispensations of asthma medication in the NorPD within a 12-mo interval, the first prescription being dispensed between ages 6 and 7 y. Noncases were all children who did not meet these criteria. Asthma medications were inhaled β2-agonists, inhaled glucocorticoids, combination inhalers with β2-agonists and glucocorticoids, or leukotriene receptor antagonists.

Covariates

Potential confounders and covariates were based on data from the birth registry (maternal age at delivery, parity, region of delivery, mode of delivery, child's sex, birth weight, and gestational age) or MoBa questionnaires completed at approximately gestational weeks 18 (inclusion), 20 (FFQ), and 30 and when the child was aged 6 mo.

Because cod liver oil and other omega-3 supplements contribute to the intake of vitamins A and D in many MoBa women (13), we also evaluated maternal intakes of other nutrients provided by these supplements, including vitamin E (preservative, antioxidant) and long-chain n–3 fatty acids (EPA, docosapentaenoic acid, and DHA). In addition, we included vitamin C as a measure of fruit and vegetable intake (29), folate intake (30), and total energy intake. In sensitivity analyses, we also evaluated maternal zinc intake (3) and birth year to control for a potential cohort effect. To assess potential confounding by UV exposure in the analysis of vitamin D intake, we included leisure-time physical activity (0, ≤1, 2–4, or ≥5 times/wk) and solarium use (0, 1–5, or ≥6 total times) in pregnancy, geographical region of delivery within Norway (South and East, West, Mid, North) as a proxy for latitude of residence, and season of delivery (January–March, April–June, July–September, or October–December). Maternal histories of asthma and allergic disorders (separate variables) were defined as ever reports at week 18 of asthma or hay fever, atopic dermatitis, animal hair allergies, or “other” allergies.

Many clinical practice guidelines recommend the use of dietary supplements, including multivitamins, to ensure adequate nutrient supply to low-birth-weight or premature infants (31). To adjust for child frailty, which could be related to both supplement use (therapeutic or nontherapeutic) and later asthma susceptibility, we included low birth weight (<2500 g), premature birth (gestational age <37 wk), and postnatal exposures in the first 6 mo to full breastfeeding (number of months), respiratory tract infections (no or yes), and maternal smoking (no, sometimes, or daily) in the main analysis. In sensitivity analyses, we additionally included child's sex, birth season, cesarean delivery (no or yes), and use of paracetamol or acetaminophen (no or yes) and antibiotics (no or yes) in the first 6 mo.

Statistical analysis

We examined associations of maternal vitamin A and D intake during pregnancy (exposures) and infant supplement use (exposures) with children's asthma (outcome) by using log binomial regression. We calculated RRs with 95% CIs on the basis of robust cluster variance estimation and controlled for potential confounding by multivariable adjustment. The NorPD linkage enabled near-complete follow-up for asthma.

Our regression models were based on a directed acyclic graph for the hypothesized causal relations (Supplemental Figure 1). According to the graph, the effects of maternal intake and infant supplementation on children's asthma can be estimated independently when potential confounding factors and mediators are adjusted for. In the analysis of maternal intake (model 1), vitamins A and D were mutually adjusted for (Spearman correlation of 0.53, continuous data), and we additionally adjusted for total intakes of other nutrients (vitamin E; sum of the n–3 fatty acids EPA, docosapentaenoic acid, and DHA; vitamin C; and folate) and energy during pregnancy, maternal prenatal factors (age at delivery, parity, prepregnancy BMI, education, history of asthma and atopy, and smoking in pregnancy), and birth weight and prematurity as potential mediators. In the analysis of infant supplementation (model 2), we mutually adjusted for the different supplements given and included all model 1 factors and postnatal child factors (months of full breastfeeding, child respiratory tract infections in the first 6 mo, and maternal smoking since birth). Missing values in individual covariates were <5% (Supplemental Table 1) and handled by multiple imputation by using chained equations (10 imputations). For 10.6% of the main study sample with missing questionnaire follow-up at age 6 mo (6534 of 61,676), we assessed the effect of imputing the infant supplement exposure data before performing multivariable adjustments.

All of the maternal nutrient intake variables were included as quintiles to account for a potential nonlinear association with children's asthma. We tested for linearity by including the quintile values (ordinal scale) as a continuous variable. To examine the potential interaction between vitamins A and D in the mother, we created a binary variable for high (highest quintile) compared with low (all lower quintiles) intakes of each vitamin and 4 mutually exclusive exposure categories for the following combinations: low vitamin A and low vitamin D, high vitamin A and low vitamin D, high vitamin D and low vitamin A, and high vitamin A and high vitamin D. To account for multiple supplement use in children, we created 6 mutually exclusive categories for daily or sometimes compared with never use of the following: 1) vitamin D only; 2) cod liver oil only; 3) multivitamin only; 4) any vitamin D supplement, including cod liver oil, combined with a multivitamin; 5) multiple vitamin D supplements (e.g., vitamin D only combined with a fish-oil supplement containing vitamin D); and 6) none of the categories (reference).

In sensitivity analyses, we added more covariates to our main multivariable regression models, as described in Results, and we performed propensity score matching as an alternative method of controlling for potential confounding (32). We tested for multiplicative interaction between maternal intakes of vitamin A and vitamin D, taking potential nonlinearity into account by including all spline term combinations from restricted cubic spline models with 4 knots. We also assessed the potential influence of unmeasured confounding by using a recently published framework developed by Ding and VanderWeele (33). The significance level was 5% for all tests. The analyses were conducted in Stata 14.0 (StataCorp LP).

RESULTS

Participant selection is shown in Figure 1, and selected participant characteristics are shown in Table 1 (mothers) and Table 2 (children). Characteristics were similar for the main study sample, the subsample with questionnaire follow-up at 6 mo, and the biomarker subsample (Supplemental Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Distribution of maternal characteristics according to the lowest (Q1) and highest (Q5) quintiles of total vitamin A and D intake in pregnancy1

| Vitamin A | Vitamin D3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (≤779 RAEs/d) | Q5 (≥2031 RAEs/d) | Q1 (≤3.5 µg/d) | Q5 (≥13.6 µg/d) | |

| n | 12,331 | 12,346 | 12,089 | 12,378 |

| Maternal age at delivery, % | ||||

| <25 y | 12.9 | 11.5 | 13.6 | 9.5 |

| 25–30 y | 43.0 | 42.0 | 42.3 | 40.1 |

| >30 y | 44.0 | 46.5 | 44.1 | 50.4 |

| Previous children, % | ||||

| 0 | 43.5 | 46.3 | 38.7 | 49.2 |

| 1 | 36.8 | 34.6 | 39.1 | 33.2 |

| ≥2 | 19.7 | 19.2 | 22.2 | 17.6 |

| Maternal education, % | ||||

| Less than high school | 9.5 | 8.3 | 10.7 | 6.5 |

| High school | 33.4 | 30.3 | 35.4 | 27.0 |

| ≤4 y of college | 38.6 | 40.8 | 37.7 | 41.8 |

| >4 y of college | 18.0 | 20.1 | 15.8 | 24.3 |

| Missing | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Maternal prepregnancy BMI (kg/m2), % | ||||

| <18.5 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 3.2 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 57.8 | 64.9 | 56.0 | 67.9 |

| 25.0–29.9 | 25.0 | 20.3 | 25.9 | 19.5 |

| ≥30 | 11.8 | 9.1 | 12.9 | 7.1 |

| Missing | 3.0 | 2.6 | 3.1 | 2.4 |

| Maternal smoking in pregnancy, % | ||||

| No | 74.8 | 76.2 | 73.0 | 78.7 |

| Stopped in pregnancy | 15.6 | 15.8 | 16.0 | 14.7 |

| Yes | 9.6 | 8.0 | 11.0 | 6.6 |

| Missing | <0.01 | 0.00 | <0.01 | 0.02 |

| Maternal history of asthma, % yes | 7.2 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 7.2 |

| Maternal history of atopy, % yes | 29.9 | 32.5 | 30.0 | 32.1 |

| Supplement use in pregnancy, % yes | ||||

| Cod liver oil | 12.4 | 31.8 | 2.2 | 70.2 |

| Other n–3 supplement | 28.4 | 42.8 | 21.6 | 22.5 |

| Multivitamin | 19.2 | 67.3 | 10.0 | 69.4 |

| Folic acid | 39.7 | 75.9 | 32.3 | 75.7 |

| Child supplement use at 6 mo (n = 55,142), % yes | ||||

| Cod liver oil | 40.9 | 51.4 | 38.4 | 59.3 |

| Vitamin D drops | 24.5 | 24.8 | 23.2 | 23.9 |

| Multivitamins | 9.1 | 8.9 | 9.6 | 7.1 |

1 n = 61,676. Q, quintile; RAE, retinol activity equivalent.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of child characteristics according to any (sometimes or daily) postnatal supplement use in the first 6 mo1

| n | % | Cod liver oil, % | Vitamin D drops, % | Multivitamin, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child birth weight, g | |||||

| <2500 | 1473 | 2.7 | 43.1 | 12.8 | 44.5 |

| 2500–4500 | 51,223 | 92.9 | 54.3 | 29.3 | 8.4 |

| ≥4501 | 2424 | 4.4 | 54.0 | 25.5 | 8.1 |

| Missing | 22 | 0.04 | 40.9 | 27.3 | 22.7 |

| Preterm birth | |||||

| No (≥37 wk gestation) | 52,346 | 94.9 | 54.4 | 29.1 | 8.3 |

| Yes (≤36 wk gestation) | 2577 | 4.7 | 46.7 | 19.9 | 30.7 |

| Missing | 219 | 0.4 | 49.8 | 22.8 | 12.8 |

| Months of full breastfeeding | |||||

| 0 | 658 | 1.2 | 47.6 | 18.2 | 13.2 |

| 1 to <4 | 21,295 | 38.6 | 51.4 | 27.7 | 11.1 |

| 4 to <6 | 25,354 | 46.0 | 55.2 | 29.9 | 8.9 |

| ≥6 | 7835 | 14.2 | 57.7 | 27.9 | 5.9 |

| Respiratory tract infections in the first 6 mo | |||||

| No | 50,838 | 92.2 | 54.1 | 28.9 | 9.2 |

| Yes, not hospitalized | 1645 | 3.0 | 51.2 | 26.7 | 12.2 |

| Yes, hospitalized | 1033 | 1.9 | 50.3 | 24.2 | 12.7 |

| Missing | 1626 | 2.9 | 56.0 | 25.5 | 8.9 |

| Postnatal maternal smoking in the first 6 mo | |||||

| No | 45,680 | 82.8 | 54.9 | 29.7 | 8.8 |

| Some | 3095 | 5.6 | 51.1 | 28.4 | 9.6 |

| Daily | 4149 | 7.5 | 46.3 | 21.0 | 14.8 |

| Missing | 2218 | 4.0 | 54.4 | 21.6 | 11.3 |

1 n = 55,142.

Characteristics of mothers and children

Associations between maternal characteristics and dietary intake in pregnancy (n = 61,676) were generally in the same direction for vitamins A and D. High intakes were associated with older age, higher education, primiparity, lower BMI, less smoking, and supplement use (Table 1).

Supplementation with cod liver oil at age 6 mo was related to high maternal intakes of both vitamins A and D (Table 1) and was higher in children with positive health indicators (birth weight ≥2500 g, term birth, breastfeeding ≥6 mo, and no respiratory tract infections or postnatal maternal smoking) (Table 2). The use of multivitamins (percentage) was much higher among low--birth weight (45%) and premature (31%) children, indicating therapeutic use according to clinical practice guidelines (31), and was associated with shorter breastfeeding and more postnatal maternal smoking (Table 2).

Maternal intakes of vitamins A and D and child asthma

The prevalence of current asthma at age 7 y, based on prescription registry data, was 4.1% (2546 of 61,676). Children born to women in the highest compared with the lowest quintile of total vitamin A intake during pregnancy had a slightly higher prevalence of asthma (4.9% compared with 4.1%), and the adjusted RR was 20% higher (Table 3). We observed the lowest prevalence of asthma (3.6%) in the second quintile of total vitamin A (780–1102 RAEs/d) in which intake was close to, or slightly above, the public recommendation for pregnant women of 800 RAEs/d in Nordic countries (34), which is similar to other national recommendations (35). Relative to the second quintile, the adjusted RR of asthma was 32% higher (95% CI: 1.15, 1.51) in the highest quintile. The effect of total vitamin A (retinol and β-carotene) was only marginally stronger than for total retinol. Total β-carotene showed a weak, but positive association with asthma after adjustment for total retinol. The adjusted RR for the highest (≥4007 µg/d) compared with the lowest (≤1360 µg/d) quintile of β-carotene was 1.11 (95% CI: 0.98, 1.27) (Supplemental Table 2). The Spearman correlation between total retinol and total β-carotene (continuous data) was 0.12. A high intake of vitamin A from food was not associated with asthma when the study sample was restricted to nonusers of retinol-containing supplements (712 cases; n = 16,924). The adjusted RR was 1.05 (95% CI: 0.81, 1.36) for the highest (≥1462 RAEs/d) compared with the lowest (≤97 RAEs/d) quintile of food vitamin A intake (results not shown).

TABLE 3.

Total vitamin A and vitamin D intake in pregnancy and RR estimates (95% CIs) for current asthma at age 7 y1

| Quintiles of intake | Cases/total n | Prevalence, % | Crude RR | Adjusted RR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total vitamin A (RAEs/d) | ||||

| Q1 (≤779) | 506/12,331 | 4.1 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Q2 (780–1102) | 445/12,323 | 3.6 | 0.88 (0.78, 1.00) | 0.92 (0.80, 1.05) |

| Q3 (1103–1479) | 475/12,331 | 3.9 | 0.94 (0.83, 1.06) | 0.99 (0.86, 1.13) |

| Q4 (1480–2030) | 520/12,345 | 4.2 | 1.03 (0.91, 1.16) | 1.08 (0.93, 1.24) |

| Q5 (≥2031) | 600/12,346 | 4.9 | 1.18 (1.05, 1.33) | 1.21 (1.05, 1.40) |

| P-trend | <0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Total vitamin D (µg/d) | ||||

| Q1 (≤3.5) | 531/12,089 | 4.4 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Q2 (3.6–5.7) | 485/12,487 | 3.9 | 0.88 (0.78, 1.00) | 0.90 (0.79, 1.02) |

| Q3 (5.8–8.6) | 496/12,393 | 4.0 | 0.91 (0.81, 1.03) | 0.89 (0.77, 1.03) |

| Q4 (8.7–13.5) | 556/12,329 | 4.5 | 1.03 (0.91, 1.15) | 0.96 (0.82, 1.12) |

| Q5 (≥13.6) | 478/12,378 | 3.9 | 0.88 (0.78, 0.99) | 0.81 (0.67, 0.97) |

| P-trend | 0.46 | 0.03 | ||

1 n = 61,676. RRs are from a log binomial regression model. Q, quintile; RAE, retinol activity equivalent; ref, reference.

2Adjusted for maternal total intakes of vitamins A or D (mutual adjustment), vitamin E, vitamin C, folate, and sum of n–3 fatty acids (all in quintiles) and total energy intake (continuous); the following maternal prenatal factors: age at delivery (continuous), parity (0, 1, or ≥2), education (less than high school, high school, ≤4 y of college/university, or >4 y of college/university), prepregnancy BMI (kg/m2; <18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25.0–29.9, or ≥30), history of asthma (no or yes), history of atopy (no or yes), and smoking in pregnancy (no, quit, or yes); and the following mediators: birth weight (<2500, 2500–4500, or ≥4500 g) and prematurity (no or yes). Missing values in covariates were handled by multiple imputation (m = 10) by using chained equations.

A high intake of vitamin D during pregnancy was associated with less-frequent asthma (3.9% compared with 4.4% for the highest compared with the lowest quintile), and the adjusted RR was ∼20% lower in the highest compared with the lowest quintile (Table 3). We observed no adverse effect of high vitamin A, or a protective effect of vitamin D, for intakes in the highest quintiles of both nutrients (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Combined effect of total vitamin A and vitamin D intake in pregnancy and RR estimates (95% CIs) for current asthma at age 7 y1

| Total vitamin A (RAEs/d) | Total vitamin D (µg/d) | Cases/total n | Prevalence, % | Crude RR | Adjusted RR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (≤2030) | Low (≤13.5) | 1687/41,903 | 4.0 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| High (≥2031) | Low (≤13.5) | 381/7395 | 5.2 | 1.28 (1.15, 1.43) | 1.21 (1.08, 1.36) |

| Low (≤2030) | High (≥13.6) | 259/7427 | 3.5 | 0.87 (0.76, 0.98) | 0.86 (0.73, 1.00) |

| High (≥2031) | High (≥13.6) | 219/4951 | 4.4 | 1.10 (0.96, 1.26) | 0.99 (0.83, 1.18) |

1 n = 61,676. RRs are from a log binomial regression model. A high intake corresponds to the highest quintile (Q5) and low intake to all lower quintiles (Q1–Q4) in Table 3. Q, quintile; RAE, retinol activity equivalent; ref, reference.

2Adjusted for maternal total intake of vitamins A or D (mutual adjustment), vitamin E, vitamin C, folate, and sum of n–3 fatty acids (all in quintiles) and total energy intake (continuous); the following maternal prenatal factors: age at delivery (continuous), parity (0, 1, or ≥2), education (less than high school, high school, ≤4 y of college/university, or >4 y of college/university), prepregnancy BMI (kg/m2; <18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25.0–29.9, or ≥30), history of asthma (no or yes), history of atopy (no or yes), and smoking in pregnancy (no, quit, or yes); and the following mediators: birth weight (<2500, 2500–4500, or ≥4500 g) and prematurity (no or yes). Missing values in covariates were handled by multiple imputation (m = 10) by using chained equations.

Food and supplement contributions to maternal intake of total vitamins A and D

The use of supplements containing retinol, including cod liver oil, was common (73% overall compared with 86% in the highest quintile). The median intake of supplemental retinol among users was ≥300 µg/d in the third through fifth quintiles of total vitamin A intake, indicating that many pregnant women take more than the standard daily dose of 250 µg, or combine multiple supplements. However, food retinol contributed most to total vitamin A (Supplemental Table 3). The main food sources were sandwich meats, including liver spread, fortified margarine, and dairy products. In Norway, dairy products are not fortified with retinol. Low-fat milk is fortified with low amounts of vitamin D, but food intake of vitamin D varied little, and the use of supplemental vitamin D (76% overall compared with 99% in the highest quintile) was an important contributor to total vitamin D intake (Supplemental Table 4).

Biomarker comparisons

In the biomarker subsample (n = 2244), maternal plasma vitamin D3 concentration increased across each quintile of total vitamin D intake (medians: 68, 72, 74, 75, and 82 nmol/L for the first through the fifth quintile, respectively; see Supplemental Table 4). The overall plasma-diet Spearman correlation (continuous) for vitamin D varied with the season of blood draw, from 0.15 in summer to 0.32 in winter. Associations with indicators of UV exposure were in the expected direction (Supplemental Table 5): plasma vitamin D3 increased with leisure-time physical activity and tanning bed use in pregnancy and from North to South for geographical region of delivery. The maternal plasma retinol concentration (median: 1.64 µmol/L; IQR: 1.46–1.83 µmol/L) varied little with vitamin A intake (see Supplemental Table 3), also as expected, due to its strict homeostatic control.

Infant supplementation and child asthma

Daily infant supplementation with vitamin D only or cod liver oil was not associated with the risk of asthma at school age. Daily use of multivitamins was associated with a 19% higher RR after multivariable adjustment (Table 5). However, there was no increased risk for any (daily or sometimes) use of multivitamins in infants who were given an additional vitamin D–containing supplement.

TABLE 5.

Infant supplement use in the first 6 mo and crude and adjusted RR estimates (95% CIs) for current asthma at age 7 y1

| Cases/total n | Prevalence, % | Crude RR2 | Crude RR3 | Adjusted RR3,4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cod liver oil | |||||

| No | 1095/25,365 | 4.3 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Sometimes | 428/11,579 | 3.7 | 0.86 (0.77, 0.96) | 0.86 (0.77, 0.97) | 0.91 (0.81, 1.02) |

| Daily | 721/18,198 | 4.0 | 0.92 (0.84, 1.01) | 0.92 (0.84, 1.01) | 0.97 (0.87, 1.09) |

| Vitamin D only | |||||

| No | 1617/39,343 | 4.1 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Sometimes | 152/3746 | 4.1 | 0.99 (0.84, 1.16) | 1.02 (0.87, 1.19) | 1.05 (0.89, 1.23) |

| Daily | 475/12,053 | 3.9 | 0.96 (0.87, 1.06) | 0.99 (0.90, 1.10) | 0.97 (0.86, 1.09) |

| Multivitamins | |||||

| No | 2008/50,363 | 4.0 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Sometimes | 81/2129 | 3.8 | 0.95 (0.77, 1.19) | 0.97 (0.78, 1.21) | 0.88 (0.71, 1.10) |

| Daily | 155/2650 | 5.9 | 1.47 (1.25, 1.72) | 1.45 (1.24, 1.70) | 1.19 (1.01, 1.41) |

| Combined use (sometimes/daily) | |||||

| Neither category | 410/9397 | 4.3 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Cod liver oil only | 936/24,545 | 3.8 | 0.89 (0.80, 1.00) | 0.90 (0.80, 1.01) | 0.97 (0.86, 1.09) |

| Vitamin D only | 524/12,978 | 4.0 | 0.95 (0.83, 1.08) | 0.97 (0.85, 1.10) | 1.00 (0.88, 1.15) |

| Multivitamin only | 149/2493 | 6.0 | 1.40 (1.16, 1.69) | 1.39 (1.15, 1.67) | 1.19 (0.98, 1.43) |

| Any vitamin D supplement and multivitamin | 108/2541 | 4.3 | 1.00 (0.81, 1.23) | 1.03 (0.84, 1.27) | 0.94 (0.76, 1.15) |

| Multiple vitamin D supplements | 126/3188 | 4.0 | 0.93 (0.76, 1.13) | 0.99 (0.81, 1.21) | 1.02 (0.83, 1.26) |

1 n = 61,676. ref, reference.

2RRs were from a log binomial regression model. Sample included participants with a follow-up questionnaire at 6 mo (n = 55,142).

3RRs were from a log binomial regression model. Analysis included all eligible children (n = 61,676) with child supplement use imputed for 10.6% of the sample with missing follow-up at age 6 mo. Missing values were handled by multiple imputation (m = 10) by using chained equations.

4Infant supplements (vitamin D only, cod liver oil, multivitamins) were mutually adjusted for with additional adjustments for maternal total intake of vitamins A, D, E, and C; folate; sum of n–3 fatty acids (all in quintiles); and total energy (continuous); the following maternal prenatal factors: age at delivery (continuous), parity (0, 1, or ≥2), education (less than high school, high school, ≤4 y of college/university, or >4 y of college/university), prepregnancy BMI (kg/m2; <18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25.0–29.9, or ≥30), history of asthma (no or yes), history of atopy (no or yes), and smoking in pregnancy (no, quit, or yes); and the following postnatal child factors: birth weight (<2500, 2500–4500, or ≥4500 g), prematurity (no or yes), months of full breastfeeding (0, 1 to <4, 4 to <6, or ≥6 mo), child respiratory tract infections in first 6 mo (no or yes), and maternal smoking since birth (none, sometimes, or daily). Missing values in covariates were handled by multiple imputation (m = 10) by using chained equations.

Maternal and child sensitivity analyses

Results on maternal intake (Table 3) were robust to a range of sensitivity analyses including additional adjustment for total zinc intake, proxy variables for UV exposure during pregnancy (leisure-time physical activity, tanning bed use, and geographical region of delivery) in the vitamin D analysis, or birth year to control for a potential cohort effect (Supplemental Table 6). The results from the nonlinear analysis of multiplicative interaction were not significant (P-interaction from 0.59 to 0.94 in the multivariable model). Confounder adjustment by multivariable regression and propensity score matching gave similar results (Supplemental Table 7). From our main model (Table 3), we estimated the direct effect of maternal intake not mediated through low birth weight and prematurity; however, the total effect, not adjusting for these mediators, was similar (results not shown). Results on infant supplement use (Table 5) were little affected by additional adjustment for indicators of child frailty or asthma susceptibility (child's sex, birth season, delivery by cesarean section, and antibiotics and paracetamol use) or the exclusion of 5.5% (3399 of 61,676) of premature or low--birth weight children (Supplemental Table 8). Maternal and child risk estimates were also unaffected by the exclusion of 20% of controls (11,828 of 59,130) who had been dispensed any asthma medication by the age of 8 y (see Supplemental Tables 6 and 8).

Ding and VanderWeele's (33) approach for assessing the potential influence of unmeasured confounding showed that to completely explain an RR of 1.2 (as we observed for a high maternal intake of total vitamin A and for infant supplementation with multivitamins) it would take an unmeasured confounder with a strength ≥1.7, which is stronger than what we observed for all of our measured confounders, except for maternal asthma.

DISCUSSION

In this large population–based pregnancy cohort study, a high maternal intake of vitamin A during pregnancy was associated with more asthma and a high intake of vitamin D was associated with less asthma in children at age 7 y, independent of infant supplement use in the first 6 mo. The RR for intake in the highest compared with the lowest quintile was ∼20% higher for vitamin A and 20% lower for vitamin D. In agreement with the hypothesis that vitamin A may antagonize actions of vitamin D, we observed no protective effect of vitamin D when the intake of vitamin A was high and likewise no adverse effect of high vitamin A in the face of high vitamin D. We found no protective effect of infant supplementation with vitamin D only, or cod liver oil, on asthma at school age.

Total vitamin A intake in the highest quintile (≥2031 RAEs/d), in which we observed more frequent asthma, corresponds to ∼2.5 times the recommended intake for pregnant women of 800 RAEs/d (34, 35). In comparison, the cutoff for the upper quintile of vitamin D (≥13.6 µg/d), in which we observed less asthma, was close to the Nordic (10 µg/d) and US (15 µg/d) recommendations for pregnant women.

Comparison with other studies

Few other studies have assessed asthma development in school-age children in relation to pregnancy intake of vitamin A, including retinol, outside of populations at risk of deficiency. In a study from the Danish National Birth Cohort with half the sample size of the current study, the association of total vitamin A intake with the risk of asthma at age 7 y was only borderline significant (21), but the magnitude (8% higher risk per 1000-µg/d increase) is compatible with our finding of a 20% increased risk in the highest quintile. A study from Finland of maternal antioxidant intake during pregnancy showed positive, but nonsignificant, relations of total intake of carotenoids (α and β) and retinol from food (0.2% retinol supplement use was ignored) with child asthma at age 5 y (20). Our results support that intakes of β-carotene or food vitamin A alone (results shown in Supplemental Table 2) are not sufficient, or high enough, in most women, to increase asthma risk. Furthermore, vitamin A supplementation trials conducted in areas of Nepal with endemic deficiency reported better lung function in children of supplemented mothers (17, 18). A prospective study in Norwegian adults reported that daily intake of cod liver oil was associated with increased incidence of asthma (36). The authors attributed the association to the high retinol content of Norwegian cod liver oil at the time (1000 µg/5 mL before 1999), combined with a traditional diet rich in vitamin A. Thus, the risk of adverse effects of vitamin A appears to be greater in Western populations who consume supplemental retinol in the face of high food retinol intake.

A high intake of vitamin D from our FFQ was reflected in higher maternal circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D, which has been associated with a lower risk of asthma in a recent meta-analysis of birth cohort studies (11), including a case-cohort study in younger MoBa children (37). The findings of this review and our current study are in keeping with recent reports from 2 trials of prenatal vitamin D supplementation, which suggest an inverse association between prenatal exposure to vitamin D and child asthma (38). Our results suggested that the protective effect of high vitamin D intake was attenuated among those with vitamin A intake in the highest quintile. Likewise, there was no adverse effect of high vitamin A intake when vitamin D intake was high. Other studies support that retinol and vitamin D may have antagonistic effects that affect health outcomes. A large, nested, case-control study of colorectal cancer found that the protective effect of high circulating vitamin D disappeared in subjects with a high retinol intake (≥1000 µg/d) (39); however, vitamin D may also reduce toxicity from retinol. In a review of case-reports of vitamin A toxicity, the median dose of retinol associated with toxicity was higher in cases who had also taken vitamin D (40).

Strengths and limitations of this study

Our study has several strengths. We used a validated FFQ and few previous studies have estimated the total intake of vitamin A from foods and supplements during pregnancy outside of deficient populations (20, 21). In addition, we had high statistical power (2546 cases) to study asthma, and the prescription registry linkage enabled near-complete follow-up to school age. As in other large, nationwide, population-based studies, we were not able to classify asthma on the basis of clinical examination, and we cannot rule out some misclassification in our asthma outcome. We expect that any bias in our RR estimates would be in the direction of slight attenuation, because the risk of outcome misclassification should be low and independent of maternal exposure (nondifferential error). Norway has universal health care and prescription coverage, so undiagnosed or untreated asthma should be rare. In addition, in a validation study of the MoBa 7-y questionnaire items with regard to asthma, we found that even a single dispensing of asthma medication was very rare in the absence of the maternal report of a doctor’s diagnosis of asthma (41). A prescription for asthma medication requires a physician’s evaluation, and we required ≥2 prescriptions to increase the positive predictive value of our asthma definition (42). Furthermore, we would not expect high maternal intakes of vitamin A and vitamin D to be associated with asthma in opposite directions, if high intakes just reflected differences in health consciousness and health-seeking behavior.

A limitation of this study is that we did not have data on nutrient intake from supplements in infants, but we were able to compare different supplements. Our results suggested more asthma among children who were given multivitamins but not cod liver oil. Both supplements provide similar doses of vitamin A (typically 200–250 µg) and vitamin D (typically the recommended dose of 10 µg), and cod liver oil also contains vitamin E and n–3 fatty acids. A potential explanation for this difference is that liquid multivitamins for children contain water-miscible or emulsified retinol, which could be more toxic than retinol in oil-based solutions such as cod liver oil (40). Interestingly, a Swedish study found an increased risk of asthma and allergy in infants supplemented with vitamins A and D in water-based but not oil-based formula (43). In our study, the lack of association between any multivitamin use and the risk of asthma in infants who were given an additional supplement containing vitamin D could be explained by an antagonistic effect of vitamin D on retinol. However, it is also possible that these infants had a lower intake of multivitamins than infants in the multivitamin-only category due to alternating use of a vitamin D supplement. Other vitamins or minerals in a multivitamin formula, potentially folic acid, could also affect asthma development (30). Unmeasured confounding is always of concern in observational studies, but Ding and VanderWeele's (33) framework provides some reassurance that even a modest RR of 1.2 is relatively robust to unmeasured confounding. Last, we did not assess the potential influence of vitamin A and D exposures at other time points, such as during lactation or after age 6 mo, on our results.

Potential mechanisms

Asthma is characterized by chronic airway inflammation and has been associated with atopy and a T-helper 2 (Th2)–dominated cytokine profile. Vitamin A exerts many of its effects through retinoic acid–mediated gene transcription, and retinoic acid may have a Th2 cell–promoting effect (44). Although vitamin A is mainly stored in the liver, excess vitamin A also accumulates in the lung (15), where retinoid metabolites may cause asthma-like symptoms (45). In the rat lung, vitamin A supplementation with higher and intermediate doses increases markers of oxidative stress (46), which also may impair lung function. We found no indication that antioxidant properties of β-carotene protect against asthma. The effect of β-carotene was weaker but in the same direction as retinol. However, many aspects related to the maternal–fetal transfer of retinoids and carotenoids, their metabolism in the developing tissues, and homeostatic control in the face of excessive maternal dietary vitamin A intake are still poorly understood (47). Our results suggest that little, if any, of the effects of vitamin A and D intake during pregnancy on child asthma were mediated through low birth weight or prematurity. We found some indication that the adverse effects associated with excess vitamin A were mitigated by having a sufficient intake of vitamin D. This observation is in line with mechanistic studies in myeloid cells, which showed that vitamin D represses retinoic acid transcriptional activity, but the action is 2 way, which also explains how vitamin A can attenuate vitamin D activity (22).

Conclusions

In this study, we found that a diet naturally high in vitamin A combined with the use of supplements containing retinol during pregnancy place women at risk of vitamin A excess, which was associated with increased susceptibility to asthma in school-age children. We observed this effect for intakes that were ≥2.5 times the recommended dose, which is below the tolerable upper intake level for retinol of 3000 µg/d during pregnancy (27). Vitamin D intake close to recommendations was associated with a reduced risk of asthma at school age but not when maternal intake of vitamin A was high. Thus, the balance of vitamin A and vitamin D intake during pregnancy could be of importance to asthma susceptibility in the offspring. A high intake of dietary retinol combined with a low intake of vitamin D is seen in many Western populations (12) in which child asthma is common.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—WN and CLP: were responsible for the study conception, design, and data acquisition; CLP, ØK, NAL-B, and MH: contributed to the data analysis; CLP: wrote the manuscript and had primary responsibility for the final content; and all authors: contributed to the interpretation of data, revised the manuscript for intellectual content, and read and approved the final manuscript. The authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Notes

The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study is supported by the Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services and the Ministry of Education and Research, NIH/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (contract no. N01-ES-75558), and NIH/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grant nos. 1 UO1 NS 047537-01 and 2 UO1 NS 047537-06A1). This work was also supported by the Norwegian Research Council (grant no. 221097; to WN) and by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (ZO1 ES49019; to SJL).

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Supplemental Figure 1 and Supplemental Tables 1–8 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/.

Abbreviations used: FFQ, food-frequency questionnaire; MoBa, Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study; NorPD, Norwegian Prescription Database; RAE, retinol activity equivalent.

REFERENCES

- 1. Global Burden of Disease 2015 Disability-Adjusted Life-Years (DALYs) and Healthy Life Expectancy (HALE) Collaborators Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388(10053):1603–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Seaton A, Godden DJ, Brown K. Increase in asthma: a more toxic environment or a more susceptible population? Thorax 1994;49(2):171–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beckhaus AA, Garcia-Marcos L, Forno E, Pacheco-Gonzalez RM, Celedon JC, Castro-Rodriguez JA. Maternal nutrition during pregnancy and risk of asthma, wheeze, and atopic diseases during childhood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy 2015;70(12):1588–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Han YY, Forno E, Holguin F, Celedon JC. Diet and asthma: an update. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;15(4):369–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Julia V, Macia L, Dombrowicz D. The impact of diet on asthma and allergic diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 2015;15(5):308–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sharma S, Chhabra D, Kho AT, Hayden LP, Tantisira KG, Weiss ST. The genomic origins of asthma. Thorax 2014;69(5):481–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cashman KD, Dowling KG, Skrabakova Z, Gonzalez-Gross M, Valtuena J, De Henauw S, Moreno L, Damsgaard CT, Michaelsen KF, Molgaard C, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in Europe: pandemic? Am J Clin Nutr 2016;103(4):1033–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Manousaki D, Paternoster L, Standl M, Moffatt MF, Farrall M, Bouzigon E, Strachan DP, Demenais F, Lathrop M, Cookson W, et al. Vitamin D levels and susceptibility to asthma, elevated immunoglobulin E levels, and atopic dermatitis: a Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med 2017;14(5):e1002294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chawes BL, Bonnelykke K, Stokholm J, Vissing NH, Bjarnadottir E, Schoos AM, Wolsk HM, Pedersen TM, Vinding RK, Thorsteinsdottir S, et al. Effect of vitamin D3 supplementation during pregnancy on risk of persistent wheeze in the offspring: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;315(4):353–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Litonjua AA, Carey VJ, Laranjo N, Harshfield BJ, McElrath TF, O'Connor GT, Sandel M, Iverson RE Jr., Lee-Paritz A, Strunk RC, et al. Effect of prenatal supplementation with vitamin D on asthma or recurrent wheezing in offspring by age 3 years: the VDAART randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;315(4):362–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Feng H, Xun P, Pike K, Wills AK, Chawes BL, Bisgaard H, Cai W, Wan Y, He K. In utero exposure to 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of childhood asthma, wheeze, and respiratory tract infections: a meta-analysis of birth cohort studies. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;139(5):1508–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jenab M, Salvini S, van Gils CH, Brustad M, Shakya-Shrestha S, Buijsse B, Verhagen H, Touvier M, Biessy C, Wallstrom P, et al. Dietary intakes of retinol, beta-carotene, vitamin D and vitamin E in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition cohort. Eur J Clin Nutr 2009;63(Suppl 4):S150–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haugen M, Brantsaeter AL, Alexander J, Meltzer HM. Dietary supplements contribute substantially to the total nutrient intake in pregnant Norwegian women. Ann Nutr Metab 2008;52(4):272–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ahluwalia N, Herrick KA, Rossen LM, Rhodes D, Kit B, Moshfegh A, Dodd KW. Usual nutrient intakes of US infants and toddlers generally meet or exceed Dietary Reference Intakes: findings from NHANES 2009–2012. Am J Clin Nutr 2016;104(4):1167–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schuster GU, Kenyon NJ, Stephensen CB. Vitamin A deficiency decreases and high dietary vitamin A increases disease severity in the mouse model of asthma. J Immunol 2008;180(3):1834–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tanumihardjo SA. Vitamin A: biomarkers of nutrition for development. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94(Suppl):658S–65S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Checkley W, West KP Jr., Wise RA, Baldwin MR, Wu L, LeClerq SC, Christian P, Katz J, Tielsch JM, Khatry S, et al. Maternal vitamin A supplementation and lung function in offspring. N Engl J Med 2010;362(19):1784–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Checkley W, West KP Jr., Wise RA, Wu L, LeClerq SC, Khatry S, Katz J, Christian P, Tielsch JM, Sommer A. Supplementation with vitamin A early in life and subsequent risk of asthma. Eur Respir J 2011;38(6):1310–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen H, Zhuo Q, Yuan W, Wang J, Wu T. Vitamin A for preventing acute lower respiratory tract infections in children up to seven years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;1:CD006090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nwaru BI, Erkkola M, Ahonen S, Kaila M, Kronberg-Kippila C, Ilonen J, Simell O, Knip M, Veijola R, Virtanen SM. Intake of antioxidants during pregnancy and the risk of allergies and asthma in the offspring. Eur J Clin Nutr 2011;65(8):937–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maslova E, Hansen S, Strom M, Halldorsson TI, Olsen SF. Maternal intake of vitamins A, E and K in pregnancy and child allergic disease: a longitudinal study from the Danish National Birth Cohort. Br J Nutr 2014;111(6):1096–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bastie JN, Balitrand N, Guidez F, Guillemot I, Larghero J, Calabresse C, Chomienne C, Delva L. 1 alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 transrepresses retinoic acid transcriptional activity via vitamin D receptor in myeloid cells. Mol Endocrinol 2004;18(11):2685–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Magnus P, Birke C, Vejrup K, Haugan A, Alsaker E, Daltveit AK, Handal M, Haugen M, Hoiseth G, Knudsen GP, et al. Cohort profile update: the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). Int J Epidemiol 2016;45(2):382–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Paltiel P, Haugan A, Skjerden T, Harbak K, Bækken S, Stensrud NK, Knudsen GP, Magnus P. The biobank of the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study—present status. Nor J Epidemiol 2014;24(1–2):29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brantsaeter AL, Haugen M, Hagve TA, Aksnes L, Rasmussen SE, Julshamn K, Alexander J, Meltzer HM. Self-reported dietary supplement use is confirmed by biological markers in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). Ann Nutr Metab 2007;51(2):146–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brantsaeter AL, Haugen M, Alexander J, Meltzer HM. Validity of a new food frequency questionnaire for pregnant women in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). Matern Child Nutr 2008;4(1):28–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Institute of Medicine Panel on Micronutrients Dietary Reference Intakes for vitamin A, vitamin K, arsenic, boron, chromium, copper, iodine, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, silicon, vanadium, and zinc. Washington (DC): National Academies Press;2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Norwegian Food Composition Database. 2nd ed Oslo (Norway): Norwegian Food Safety Authority, The Norwegian Directorate of Health and University of Oslo; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Michels KB, Welch AA, Luben R, Bingham SA, Day NE. Measurement of fruit and vegetable consumption with diet questionnaires and implications for analyses and interpretation. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161(10):987–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Parr CL, Magnus MC, Karlstad O, Haugen M, Refsum H, Ueland PM, McCann A, Nafstad P, Haberg SE, Nystad W, et al. Maternal folate intake during pregnancy and childhood asthma in a population-based cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;195(2):221–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Metodebok i nyfødtmedisin 2012 [Handbook in neonatal medicine 2012.] Tromsø (Norway): University Hospital of North Norway; 2012(in Norwegian). [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sturmer T, Joshi M, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Rothman KJ, Schneeweiss S. A review of the application of propensity score methods yielded increasing use, advantages in specific settings, but not substantially different estimates compared with conventional multivariable methods. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59(5):437–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ding P, VanderWeele TJ. Sensitivity analysis without assumptions. Epidemiology 2016;27(3):368–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2012: integrating nutrition and physical activity. Copenhagen (Denmark): Nordic Council of Ministers; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Trumbo P, Yates AA, Schlicker S, Poos M. Dietary Reference Intakes: vitamin A, vitamin K, arsenic, boron, chromium, copper, iodine, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, silicon, vanadium, and zinc. J Am Diet Assoc 2001;101(3):294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mai XM, Langhammer A, Chen Y, Camargo CA Jr. Cod liver oil intake and incidence of asthma in Norwegian adults—the HUNT study. Thorax 2013;68(1):25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Magnus MC, Stene LC, Haberg SE, Nafstad P, Stigum H, London SJ, Nystad W. Prospective study of maternal mid-pregnancy 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and early childhood respiratory disorders. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2013;27(6):532–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. von Mutius E, Martinez FD. Inconclusive results of randomized trials of prenatal vitamin D for asthma prevention in offspring: curbing the enthusiasm. JAMA 2016;315(4):347–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jenab M, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Ferrari P, van Duijnhoven FJ, Norat T, Pischon T, Jansen EH, Slimani N, Byrnes G, Rinaldi S, et al. Association between pre-diagnostic circulating vitamin D concentration and risk of colorectal cancer in European populations: a nested case-control study. BMJ 2010;340:b5500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Myhre AM, Carlsen MH, Bohn SK, Wold HL, Laake P, Blomhoff R. Water-miscible, emulsified, and solid forms of retinol supplements are more toxic than oil-based preparations. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;78(6):1152–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Furu K, Karlstad O, Skurtveit S, Haberg SE, Nafstad P, London SJ, Nystad W. High validity of mother-reported use of antiasthmatics among children: a comparison with a population-based prescription database. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64(8):878–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pekkanen J, Pearce N. Defining asthma in epidemiological studies. Eur Respir J 1999;14(4):951–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kull I, Bergstrom A, Melen E, Lilja G, van Hage M, Pershagen G, Wickman M. Early-life supplementation of vitamins A and D, in water-soluble form or in peanut oil, and allergic diseases during childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;118(6):1299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mora JR, Iwata M, von Andrian UH. Vitamin effects on the immune system: vitamins A and D take centre stage. Nat Rev Immunol 2008;8(9):685–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mawson AR. Could bronchial asthma be an endogenous, pulmonary expression of retinoid intoxication? Front Biosci 2001;6:D973–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pasquali MA, Gelain DP, Oliveira MR, Behr GA, Motta LL, Rocha RF, Klamt F, Moreira JC. Vitamin A supplementation induces oxidative stress and decreases the immunocontent of catalase and superoxide dismutase in rat lungs. Exp Lung Res 2009;35(5):427–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Spiegler E, Kim YK, Wassef L, Shete V, Quadro L. Maternal-fetal transfer and metabolism of vitamin A and its precursor beta-carotene in the developing tissues. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012;1821(1):88–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.