Abstract

This study uses Medicare billing codes to characterize trends in readmission and mortality rates for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with pulmonary embolism (PE) between 1999 and 2015 to assess changes accompanying recent diagnostic and therapeutic changes in management of the disease.

Over the past 15 years, advances have occurred in the diagnosis and management of pulmonary embolism (PE).1 Computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA) is now the routine diagnostic test. The availability of risk stratification tools and non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants that do not require routine laboratory monitoring have facilitated early discharge of patients.2

The risk of developing PEs and experiencing adverse outcomes increases with age, partly because of the comorbidity burden and low cardiopulmonary reserve.3 Little is known about recent PE hospitalizations or about outcomes in older adults in the context of the improvements in diagnostics and therapeutics.

Methods

The Human Investigation Committee at Yale University exempted the study from review because all data were deidentified. We identified Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries 65 years or older with a principal discharge diagnosis of PE (International Classification of Diseases [ICD], Ninth Revision codes: 415.1X, PE and infarction; 415.11, iatrogenic PE and infarction; 415.13, saddle embolus of pulmonary artery; and 415.19, other PE and infarction) from January 1999 through September 2015. These codes have high positive predictive values for PE.4 After October 2015, the codes were changed to ICD-10. To preserve the internal consistency for the trends, we did not include the fourth quarter of 2015.

Study outcomes included hospitalization rates per 100 000 beneficiary-years, length of stay (LOS); all-cause 30-day readmissions; and all-cause in-hospital, 30-day, and 1-year mortality. Because models for adjustment of LOS and in-hospital mortality have not been validated, unadjusted results are presented. We explored the changes in patient characteristics over time (Table). We used mixed-effects models with the Poisson link function and state-specific random intercepts to assess the hospitalization rates adjusted for demographics, and a logit link function and hospital-specific random intercepts to assess the 30-day and 1-year mortality and 30-day readmission rates, adjusted for patient characteristics. A 2-sided P < .05 was considered significant. Analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Table. Characteristics of Medicare Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries Hospitalized With Pulmonary Embolisma.

| Percentage of Patients | P Value for Linear Trend | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999-2000 | 2001-2002 | 2003-2004 | 2005-2006 | 2007-2008 | 2009-2010 | 2011-2012 | 2013-2014 | 2015 | ||

| Patients with PE, No. | 65 795 | 80 386 | 93 695 | 106 177 | 105 063 | 105 542 | 109 653 | 104 926 | 39 732 | |

| Age, mean, y | 77.6 | 77.6 | 77.8 | 78 | 78.2 | 78 | 78 | 77.7 | 77.6 | .71 |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Men | 36.7 | 37.1 | 38.8 | 39.9 | 40.7 | 41.4 | 42.1 | 43.1 | 43.8 | <.001 |

| Women | 63.3 | 62.9 | 61.2 | 60.1 | 59.3 | 58.6 | 57.9 | 56.9 | 56.2 | <.001 |

| Raceb | ||||||||||

| White | 87.5 | 86.8 | 85.8 | 85.6 | 85.6 | 85.1 | 84.9 | 84.8 | 84.8 | <.001 |

| Black | 10.2 | 10.5 | 11.5 | 11.7 | 11.4 | 12 | 12.2 | 12 | 11.8 | .005 |

| Other | 2.4 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.4 | <.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||||

| Cancer | 21.9 | 22.9 | 23.7 | 22.9 | 22.5 | 21.7 | 21.5 | 21.2 | 21.1 | .03 |

| Heart failure | 16.2 | 15.6 | 16.2 | 15.5 | 14.6 | 13.6 | 13.5 | 12.4 | 12.6 | <.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 11.9 | 11.3 | 10.9 | 10.6 | 10.3 | 9.6 | 9.2 | 8.2 | 7.9 | <.001 |

| Atherosclerotic disease | 30.4 | 30.6 | 30.5 | 29.9 | 29.5 | 28.3 | 28.1 | 25.5 | 23.6 | .001 |

| Stroke | 3.8 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.6 | <.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.5 | <.001 |

| CVD other than stroke | 5.2 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 4 | 3.6 | 3.3 | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 54.2 | 58.7 | 62.8 | 63.9 | 67.5 | 68.6 | 70.9 | 68.7 | 66.7 | <.001 |

| Respiratory failure | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 5.9 | 7.9 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 8.7 | 9.6 | <.001 |

| COPD | 27.7 | 28 | 28.9 | 29.6 | 27.8 | 25.8 | 25.4 | 24.2 | 23.6 | .005 |

| Pneumonia | 17.4 | 18.3 | 19.6 | 20.2 | 21.6 | 21.9 | 21.2 | 20.2 | 20.1 | <.001 |

| Kidney failure | 3.7 | 4.6 | 6.1 | 8.6 | 11.2 | 13 | 13.9 | 13.9 | 14.7 | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 18.8 | 20.1 | 22.1 | 22.9 | 23.4 | 23.8 | 25 | 25 | 24.4 | <.001 |

| Other conditions | ||||||||||

| Trauma | 10.6 | 10.8 | 11.3 | 11.2 | 11.1 | 10.1 | 9.7 | 8.9 | 8.8 | <.001 |

| Malnutrition | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.9 | 5.4 | 6.6 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 8.8 | 9.0 | <.001 |

| Dementia | 9.7 | 10.9 | 12.6 | 13.2 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 11.3 | 6.6 | 5.9 | .23 |

| Depression | 7.2 | 8.8 | 9.8 | 10.2 | 10.4 | 10.1 | 10.8 | 10.4 | 10.1 | .02 |

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, cerebrovascular disease.

For brevity, other comorbidities such as unstable angina, history of liver disease, other psychiatric disorder, and functional disability are not shown but were used in the adjustment models for outcomes. These 4 comorbidities had a prevalence of less than 5% in all study years.

Race was determined through the Medicare Denominator File, which used patient-reported data from the Social Security Administration.

Results

From 1999 through 2015, there were 810 969 patients with a principal discharge diagnosis of PE. Mean age did not change significantly (77.6 years). The prevalence of some comorbidities, including myocardial infarction and stroke, decreased. The prevalence of respiratory failure and malnutrition increased (P < .001 for trend for all; Table).

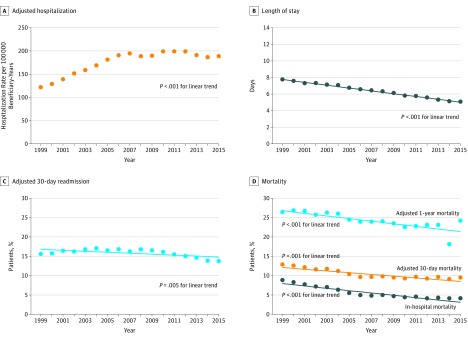

The adjusted PE hospitalization rate per 100 000 beneficiary-years was 120.0 (95% CI, 120.0-120.0) in 1999, peaked at 198.0 (95% CI, 194.4-201.6) in 2010, and was 187.2 (95% CI, 184.0-190.4) in 2015. Length of stay declined over time (from 7.7 to 5.0 days; P < .001 for trend). A significant decline was observed in adjusted 30-day readmission rates from 1999 through 2015 (from 15.5% to 13.6%; P = .005; Figure). From 1999 through 2015, unadjusted in-hospital (decline from 8.7% to 4.0%) and adjusted 30-day (decline from 12.7% to 9.4%) and 1-year (decline from 26.3% to 24.1%) mortality rates had a similar pattern (P < .001 for trend).

Figure. Hospitalization, Length of Stay, and Mortality Rates Among Medicare Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries With Pulmonary Embolism.

Thirty-day readmission rates and 30-day mortality rates were adjusted for patient characteristics listed in the Table.

Discussion

From 1999 through 2015 among older US adults, hospitalization rates for PE increased, but LOS, readmission rates, and short-term and 1-year mortality rates declined. Use of a more sensitive diagnostic modality (CTPA), which may lead to the diagnosis of anatomically small or incidental PEs with lower acuity of illness, may explain the trends.5 Alternatively, the trends, which are consistent with findings from Registro Informatizado de Enfermedad TromboEmbólica (RIETE)6—a prospective registry primarily from Europe—may reflect improvements in timeliness of diagnosis and therapeutics and in processes of care for older adults with PE. The mortality rates in the final years, when CTPA was routine, remained relatively stable, but LOS and 30-day readmission rates continued to decline.

This study had some limitations. It focused on fee-for-service beneficiaries with principal discharge diagnosis of PE and did not examine other subgroups. Data from 2016 or 2017 were not included because the codes changed to ICD-10, which may have affected the trends. No control condition was studied, so it is unknown whether the trends reflect general trends in hospitalizations, readmissions, and mortality.

Additional studies are required to determine the reasons behind the observed trends and strategies that may mitigate the residual risk of death or recurrence in older adults.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Tritschler T, Kraaijpoel N, Le Gal G, Wells PS. Venous thromboembolism: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2018;320(15):1583-1594. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. . Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berman AR. Pulmonary embolism in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 2001;17(1):107-130. doi: 10.1016/S0749-0690(05)70109-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White RH, Garcia M, Sadeghi B, et al. . Evaluation of the predictive value of ICD-9-CM coded administrative data for venous thromboembolism in the United States. Thromb Res. 2010;126(1):61-67. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiener RS, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Time trends in pulmonary embolism in the United States: evidence of overdiagnosis. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(9):831-837. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiménez D, de Miguel-Díez J, Guijarro R, et al. ; RIETE Investigators . Trends in the management and outcomes of acute pulmonary embolism: analysis from the RIETE Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(2):162-170. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]