Key Points

Question

Are perioperative opioid prescriptions or their duration associated with fewer or more return visits for complications after tonsillectomy in children than nonopiod use?

Findings

In this cohort analysis of 15 793 children who underwent tonsillectomy, having 1 or more perioperative opioid prescription fills was not associated with fewer or more return visits for pain or dehydration or secondary hemorrhage than nonopioid use, but it was associated with increased risk of return visits for constipation. Duration of perioperative opioid prescriptions was not associated with return visits for complications.

Meaning

These findings potentially support the feasibility of reducing perioperative opioid prescribing and prescription duration in children after tonsillectomy.

This cohort study evaluates private insurance claims data for perioperative opioid prescribing practice, duration of prescriptions, and possible association with return visits for complications in pediatric tonsillectomy.

Abstract

Importance

Practice guidelines recommend nonopioid medications in children after tonsillectomy, but to date, studies have not used recent national data to assess perioperative opioid prescribing patterns or the factors associated with these patterns in this population. Closing this knowledge gap may help in assessing whether such prescribing and prescription duration could be safely reduced.

Objective

To assess national perioperative opioid prescribing patterns, clinical and demographic factors associated with these patterns, and association between these patterns and complications in children after tonsillectomy compared with children not using opioids.

Design, Setting, and Participants

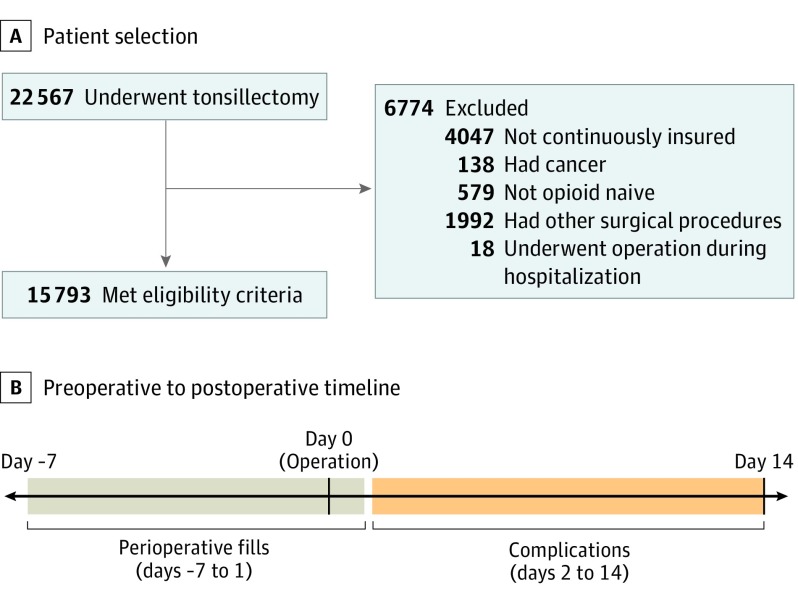

This cohort analysis used the 2016 to 2017 claims data from the database of a large national private insurer in the United States. Opioid-naive children aged 1 to 18 years with a claims code for tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy between April 1, 2016, and December 15, 2017, were identified (n = 22 567) and screened against the exclusion criteria. The final sample included 15 793 children.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The percentage of children with 1 or more perioperative fills (prescription drug claims for opioids between 7 days before to 1 day after tonsillectomy) was calculated, along with the duration of perioperative prescriptions (days supplied). Linear regression was used to identify the demographic and clinical factors associated with the duration of perioperative opioid prescriptions. Logistic regression was used to assess the association between having 1 or more perioperative fills and their duration and the risk of return visits 2 to 14 days after tonsillectomy for pain or dehydration, secondary hemorrhage, and constipation compared with children not using opioids.

Results

Among 15 793 children, the mean (SD) age was 7.8 (4.2) years, 12 807 (81.1%) were younger than 12 years, 2986 (18.9%) were between 12 and 18 years of age, and 8289 (52.6%) were female. In total, 9411 (59.6%) children had 1 or more perioperative fills, and the median (25th-75th percentile) duration was 8 (6-10) days; 6382 had no perioperative fills. The probability of having 1 or more perioperative fills and the duration of prescription varied across US census divisions. Having 1 or more perioperative fills was not associated with return visits for pain or dehydration (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.13; 95% CI, 0.95-1.34) or secondary hemorrhage (AOR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.73-1.10) compared with children not using opioids, but it was associated with increased risk of return visits for constipation (AOR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.24-3.28). Duration was not associated with return visits for complications.

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings suggest that reducing perioperative opioid prescribing and the duration of perioperative opioid prescriptions may be possible without increasing the risk of these complications.

Introduction

Tonsillectomy is one of the most common surgical procedures performed in children.1 Effective posttonsillectomy analgesia is crucial to avoid dehydration.2,3,4 Opioids are commonly used after tonsillectomy, in part because they are believed to provide superior analgesia and because nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are believed to increase hemorrhage risk. However, randomized clinical trials have shown that NSAIDs provide the equivalent posttonsillectomy analgesia as opioids do,5,6 and most studies have found that NSAIDs are not associated with differences in hemorrhage risk.7,8,9,10 Moreover, opioid exposure after tonsillectomy is associated with increased risk of constipation, new persistent opioid use, and respiratory complications.5,11,12 Based on these considerations, the 2011 and 2019 American Academy of Otolaryngology tonsillectomy clinical practice guidelines strongly recommend nonopioids such as NSAIDs for perioperative analgesia.3,4

These guidelines suggest that national practice may have moved toward fewer or shorter perioperative opioid prescriptions in children after tonsillectomy. Whether such a shift has occurred is unknown, as no recent national data are available to date on the rate or duration of perioperative opioid prescriptions in the pediatric tonsillectomy population. In addition, many studies into the associations between perioperative opioids and posttonsillectomy complications such as uncontrolled pain or hemorrhage were single-institution studies.5,13 Evaluating these associations in a large national study may help in assessing whether perioperative opioid prescribing can be safely reduced. The association between perioperative opioid prescription duration and posttonsillectomy complications is also unclear. Closing this knowledge gap is important to evaluate the feasibility of providing shorter courses of opioid therapy.

We used a national private insurance claims database to assess current perioperative opioid prescribing patterns in children after tonsillectomy and the factors associated with these patterns. In addition, we assessed the association among perioperative opioid prescription fills; the duration of perioperative prescriptions; and return visits for pain or dehydration, constipation, and secondary hemorrhage (hemorrhage beyond 24 hours after tonsillectomy). In theory, perioperative fills and longer prescription durations could decrease visits for pain or dehydration if opioids were superior for analgesia and could also protect against secondary hemorrhage by decreasing NSAID use. However, on the basis of previous studies, we hypothesized that perioperative fills and duration were not associated with differences in the risk of visits for pain or dehydration or secondary hemorrhage but were associated with increased risk of visits for constipation.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

We conducted a cohort analysis using the 2016 to 2017 Clinformatics Data Mart (OptumInsights), which contains claims from a large national private insurer. The institutional review board of the University of Michigan Medical School exempted this study from review because it used deidentified data. Informed consent was not required for this reason.

With annual sample sizes of approximately 12 million, the Clinformatics Data Mart captures patient visits in a wide variety of settings, including hospitals, emergency departments, primary care offices, and surgeon offices. Data include demographic information, International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis codes, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes, and provider taxonomy codes based on self-declared specialty by clinicians.

Prescription drug claims contain information on national drug code, quantity, and days supplied. Days supplied represents the estimated prescription duration based on quantity, frequency, and strength per dose. For example, a prescription for 48 tablets of 5 mg of oxycodone every 4 hours represents an 8-day supply (6 tablets per day).

Study Population

We identified children aged 1 to 18 years with a claim containing a CPT code for tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy during the study period (April 1, 2016, to December 15, 2017; eTable 1 in the Supplement lists codes used in the study). We did not include children who underwent only adenoidectomy. We defined the date of tonsillectomy as the first instance of these CPT codes during the study period. Because the US health care system transitioned to ICD-10-CM on October 1, 2015, we started the study period on April 1, 2016, to allow the use of only ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes in assessing comorbidities during the 180 days before tonsillectomy.

We made several exclusions (Figure 1). First, we excluded children without continuous insurance coverage during the 180 days before tonsillectomy. Second, we excluded children with 1 or more claims containing a diagnosis code for cancer on the day of or during the 180 days before tonsillectomy. Third, we excluded children with 1 or more claims for other surgical procedures from 7 days before to 1 day after tonsillectomy, except for tympanostomy and myringotomy, as these procedures were deemed unlikely to be associated with opioid prescribing or complications. Fourth, to limit the study population to opioid-naive patients, we excluded children with 1 or more prescription drug claims for an opioid between 180 days and 8 days before tonsillectomy. We did not exclude children with opioid prescription drug claims during the 7 days before tonsillectomy because opioids intended for postoperative use may be prescribed before the procedure. Fifth, we excluded children who underwent tonsillectomy while hospitalized (ie, a hospitalization with an admission date earlier than the tonsillectomy date). We did not exclude patients who were hospitalized or admitted for observation immediately after tonsillectomy for monitoring.

Figure 1. Study Design.

Perioperative fills were defined as opioid prescription claims from 7 days before to 1 day after tonsillectomy. Return visits for complications were measured during the 2 to 14 days after tonsillectomy.

Study Variables

We compiled a list of national drug codes for opioid analgesics by searching the Micromedex RED BOOK (IBM), and then we used these codes to identify opioid prescription fills (eAppendix in the Supplement).14 Study outcomes were having 1 or more perioperative fills, perioperative prescription duration, and return visits for complications. We defined perioperative fills as opioid prescription drug claims from 7 days before to 1 day after tonsillectomy (Figure 1). We included drug claims 1 day after tonsillectomy because families of children observed overnight may not fill prescriptions immediately. In regression models assessing complications, we controlled for having 1 or more late fill, defined as opioid prescription drug claims occurring 2 to 14 days after tonsillectomy. These late fills could be delayed fills of perioperative opioid prescriptions or fills of opioid prescriptions provided after the perioperative period (eg, refills, prescriptions after visits for pain or dehydration).

For most children with only 1 perioperative fill, prescription duration was measured by days supplied. For the 103 children with 2 perioperative fills (eg, 2 prescription drug claims for different opioids on the day of tonsillectomy), days supplied was summed across the fills.

We assessed return visits occurring 2 to 14 days after tonsillectomy for the following complications: (1) pain or dehydration, based on ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes such as postprocedural pain or CPT codes for intravenous fluid administration; (2) secondary hemorrhage, based on ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes for postprocedural hemorrhage or CPT codes for oropharyngeal hemorrhage control; (3) constipation, based on ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes; and (4) opioid overdose, based on ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes (eTable 1 in the Supplement).15 We began counting complications 2 days after tonsillectomy to establish a clear temporal association between perioperative fills and complications. This choice precluded capture of primary hemorrhage occurring within 24 hours of the tonsillectomy, but the risk of this complication is mostly technique-related and should not be affected by perioperative opioid prescribing decisions.

We combined return visits for pain and dehydration because some patients had return visits in which diagnosis or procedure codes for both pain and dehydration were used, potentially resulting in double counting if pain and dehydration were analyzed separately. However, we also conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we assessed pain and dehydration as separate outcomes. In addition, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we evaluated vomiting as an additional outcome.

Statistical Analysis

We fit 8 regression models. First, we used multivariable logistic regression to model having 1 or more perioperative fills as a function of (1) demographic variables, including age, sex, US census division (a measure of geographic location), and median educational level among individuals 25 years or older in the policyholder’s census block; (2) whether the surgeon was a pediatric or general otolaryngologist; (3) whether tonsillectomy alone or tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy was performed; and (4) whether children had 1 or more claims on the day of or during the 180 days before tonsillectomy with ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes for obstructive sleep apnea, mental health disorders, and other chronic conditions such as asthma, morbid obesity, and bleeding disorders (eTable 1 in the Supplement).16 We included obstructive sleep apnea as a covariate because surgeons may vary their prescribing decisions owing to the higher risk of opioid-associated respiratory depression in patients with this condition.

Second, we used linear regression to model prescription duration (continuous variable for days supplied) as a function of the same variables in the first regression analysis. The sample for this regression was limited to children with 1 or more perioperative fills.

Third through fifth, we used logistic regression to model the occurrence of return visits for pain or dehydration, secondary hemorrhage, and constipation as a function of having 1 or more perioperative fills. Models included an indicator for having 1 or more late fills and the variables in the first regression.

Sixth through eighth, we used logistic regression to model the occurrence of return visits for complications as a function of prescription duration (continuous variable for days supplied). The sample for this regression was limited to children with 1 or more perioperative fills. Models included an indicator for having 1 or more late fills and the variables in the first regression. Higher-order terms for duration were not included because coefficients were not statistically significant. Conclusions were unchanged when categorizing duration into 2-day increments (1-2 days, 3-4 days, etc) or 3-day increments (1-3 days, 4-6 days, etc).

In all regressions, higher-order terms for age were included when statistically significant. Conclusions were unchanged when clustering SEs at the clinician level.

The sample had missing data for sex (0.006%), US census division (0.2%), educational level (1.7%), and pediatric or general otolaryngologist (6.5%). For regressions, we imputed data using multiple imputation with chained equations and 30 imputations. Imputation models used the 4 variables listed earlier, age, an indicator for tonsillectomy alone, and indicators for comorbidities.

Because overdose was rare, we calculated only the unadjusted proportion of children with 1 or more perioperative fills who had a return visit for overdose between 2 and 14 days after tonsillectomy. Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and Stata, version 15.1 SE (StataCorp LLC). Two-sided tests were used, with P < .05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Among 22 567 children who underwent tonsillectomy during the study period, 6774 were excluded, leaving 15 793 (70.0%) for the sample (Figure 1). Among the 15 793 children included, the mean (SD) age was 7.8 (4.2) years, with 12 807 (81.1%) younger than 12 years and 2986 (18.9%) between 12 and 18 years of age. In total, 8289 children (52.6%) were female, and 6285 (39.8%) lived in the South (including South Atlantic, East South Central, and West South Central census divisions), compared with 991 (6.2%) in the Northeast (including New England and Middle Atlantic census divisions), 5504 (34.9%) in the Midwest (including East North Central and West North Central census divisions), and 2985 (18.9%) in the West (including Mountain and Pacific census divisions) (Table 1).

Table 1. Sample Characteristics .

| Variable | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age group, y | |

| 0-5 | 5691 (36.0) |

| 6-11 | 7116 (45.1) |

| 12-18 | 2986 (18.9) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 7503 (47.5) |

| Female | 8289 (52.5) |

| Unknown | 1 (<0.1) |

| Median educational level by census block | |

| ≤High school diploma | 3460 (21.9) |

| Some college | 8765 (55.5) |

| ≥Bachelor’s degree | 3302 (20.9) |

| Unknown | 266 (1.7) |

| US census division | |

| New England (CT, RI, MA, VT, NH, ME) | 302 (1.9) |

| Middle Atlantic (NJ, NY, PA) | 689 (4.4) |

| East North Central (IL, IN, MI, OH, WI) | 3152 (20.0) |

| West North Central (IA, KS, MN, MO, NE, ND, SD) | 2352 (14.9) |

| South Atlantic (DE, DC, FL, GA, MD, NC, SC, VA, WV) | 2365 (15.0) |

| East South Central (AL, KY, MS, TN) | 766 (4.9) |

| West South Central (AR, LA, OK, TX) | 3154 (20.0) |

| Mountain (AZ, CO, ID, MT, NV, NM, UT, WY) | 2048 (13.0) |

| Pacific (AK, CA, HI, OR, WA) | 937 (5.9) |

| Unknown | 28 (0.2) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 6298 (39.9) |

| Mental health condition | 2521 (16.0) |

| Other chronic condition | 3680 (23.3) |

| Surgeon type | |

| General otolaryngologist | 11 278 (71.4) |

| Pediatric otolaryngologist | 3482 (22.1) |

| Unknown | 1033 (6.5) |

| Procedure | |

| Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy | 14 035 (88.9) |

| Tonsillectomy alone | 1758 (11.1) |

Patterns of Opioid Prescription Fills

Among the 15 793 children, 9411 (59.6%) had 1 or more perioperative fills and 6382 (40.4%) did not. Overall, 8633 children (54.7%) had 1 or more perioperative fills and 0 late fills, 778 (4.9%) had 1 or more perioperative fills and 1 or more late fills, 340 (2.2%) had 1 or more late fills only, and 6042 (38.3%) had 0 perioperative or late fills. Among the 10 709 opioid prescription drug claims occurring between 7 days before and 14 days after tonsillectomy, 1196 (11.2%) were late fills and 9514 (88.9%) were perioperative fills. Among the 9514 perioperative fills, 1109 (11.7%) occurred before, 7829 (82.3%) occurred on the day of, and 576 (6.1%) occurred on day 1 after tonsillectomy.

Among the 15 793 children in the sample, 520 (3.3%) had 1 or more perioperative fills for codeine, 108 (0.7%) had 1 or more perioperative fills for tramadol, 1543 (9.8%) had 1 or more perioperative fills for oxycodone, 7253 (45.9%) had 1 or more perioperative fill for hydrocodone bitartrate, and 6382 (40.4%) had 0 perioperative fills (percentages do not add to 100% because some patients had 2 perioperative fills for different opioids). Among 12 807 children younger than 12 years, 341 (2.7%) had 1 or more perioperative fills for codeine.

Factors Associated With Perioperative Fills and Prescription Duration

Having 1 or more perioperative fills was positively associated with median educational level by census block (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] for ≥ bachelor’s degree vs ≤ high school diploma, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.17-1.46) and negatively associated with obstructive sleep apnea (AOR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.84-0.97) and other chronic conditions (AOR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.80-0.94). The association between age and having 1 or more perioperative fills was nonlinear. The probability of having 1 or more perioperative fills initially increased with older age (AOR for linear age, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.20-1.23), but the magnitude of the association became less positive with older age (AOR for aged squared, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.99-1.00). The probability of having 1 or more perioperative fills varied by census division (eg, West South Central vs New England: AOR, 2.22; 95% CI, 1.79-2.76) (Table 2).

Table 2. Clinical and Demographic Factors Associated With Perioperative Opioid Prescription Fills.

| Variable | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Age | 1.22 (1.20-1.23) |

| Age squared | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) |

| Female sex | 1.00 (0.93-1.07) |

| Median educational level by census block (vs ≤high school diploma) | |

| Some college | 1.10 (1.01-1.20) |

| ≥Bachelor’s degree | 1.31 (1.17-1.46) |

| US census division (vs New England) | |

| Middle Atlantic (NJ, NY, PA) | 0.66 (0.50-0.87) |

| East North Central (IL, IN, MI, OH, WI) | 0.75 (0.60-0.92) |

| West North Central (IA, KS, MN, MO, NE, ND, SD) | 1.27 (1.08-1.49) |

| South Atlantic (DE, DC, FL, GA, MD, NC, SC, VA, WV) | 1.30 (1.10-1.53) |

| East South Central (AL, KY, MS, TN) | 0.91 (0.77-1.07) |

| West South Central (AR, LA, OK, TX) | 2.22 (1.79-2.76) |

| Mountain (AZ, CO, ID, MT, NV, NM, UT, WY) | 1.73 (1.47-2.03) |

| Pacific (AK, CA, HI, OR, WA) | 1.57 (1.33-1.86) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 0.91 (0.84-0.97) |

| Mental health condition | 0.94 (0.85-1.03) |

| Other chronic condition | 0.86 (0.80-0.94) |

| Surgeon was pediatric otolaryngologist (vs general) | 1.05 (0.96-1.14) |

| Tonsillectomy alone (vs tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy) | 1.10 (0.97-1.25) |

Among children with 1 or more perioperative fills, the median (25th-75th percentile) prescription duration was 8 (6-10) days. Factors associated with shorter duration included age (–0.19 days; 95% CI, –0.21 to –0.16 days) and having a surgeon who was a pediatric otolaryngologist (–0.74 days; 95% CI, –0.98 to –0.50 days). Duration varied between census divisions (eg, Mountain vs New England: 1.50 days; 95% CI, 1.05-1.95 days) (Table 3).

Table 3. Clinical and Demographic Factors Associated With the Duration of Perioperative Opioid Prescriptions Among Patients With Perioperative Fills.

| Variable | Coefficient (95% CI), da |

|---|---|

| Age | −0.19 (−0.21 to −0.16) |

| Female sex | 0.03 (−0.17 to 0.22) |

| Median educational level by census block | |

| Some college | −0.08 (−0.32 to 0.16) |

| ≥Bachelor’s degree | 0.12 (−0.17 to 0.41) |

| US census division (vs New England) | |

| Middle Atlantic (NJ, NY, PA) | −0.28 (−1.16 to 0.59) |

| East North Central (IL, IN, MI, OH, WI) | 0.10 (−0.55 to 0.75) |

| West North Central (IA, KS, MN, MO, NE, ND, SD) | 0.01 (−0.44 to 0.46) |

| South Atlantic (DE, DC, FL, GA, MD, NC, SC, VA, WV) | 0.98 (0.50 to 1.45) |

| East South Central (AL, KY, MS, TN) | 0.82 (0.35 to 1.30) |

| West South Central (AR, LA, OK, TX) | 1.24 (0.67 to 1.80) |

| Mountain (AZ, CO, ID, MT, NV, NM, UT, WY) | 1.50 (1.05 to 1.95) |

| Pacific (AK, CA, HI, OR, WA) | 0.73 (0.25 to 1.20) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 0.17 (−0.04 to 0.38) |

| Mental health condition | 0.03 (−0.23 to 0.29) |

| Other chronic condition | −0.06 (−0.29 to 0.17) |

| Surgeon was pediatric otolaryngologist (vs general) | −0.74 (−0.98 to −0.50) |

| Tonsillectomy alone (vs tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy) | 0.02 (−0.27 to 0.32) |

Represents change in days supplied associated with a 1-unit increase in the variable.

Complications

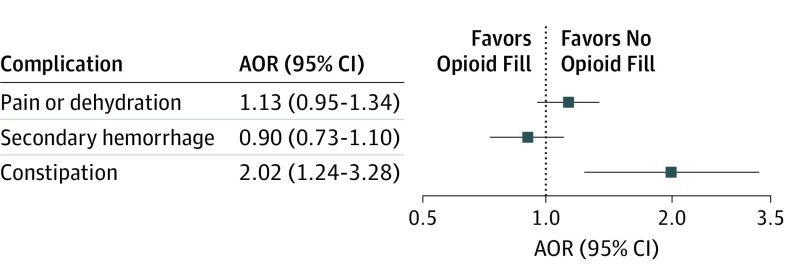

Among the 15 793 children in the sample, 665 (4.3%) had a return visit for pain or dehydration. Among 9411 children with 1 or more perioperative fills, 404 (4.3%) had a return visit for secondary pain or dehydration, compared with 261 (4.1%) of the 6382 children with 0 perioperative fills. In adjusted analyses, having 1 or more perioperative fills was not associated with return visits for pain or dehydration (AOR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.95-1.34) (Figure 2). Factors associated with increased risk of visits for pain or dehydration were female sex (AOR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.05-1.45), mental health disorder (AOR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.54-2.22), other chronic condition (AOR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.49-2.10), and having 1 or more late fills (AOR, 4.51; 95% CI, 3.66-5.57) (eTable 2 in the Supplement). The association between age and the risk of visits for pain or dehydration was nonlinear. Risk initially decreased as age increased (AOR for linear age, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.91-0.96), but the magnitude of the association became less negative with older age (AOR for age squared, 1.01; 95% CI, 1.00-1.01). Among children with 1 or more perioperative fills, duration was not associated with return visits for pain or dehydration (AOR for 1-day increase, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.98-1.02) (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Adjusted Association Between 1 or More Perioperative Opioid Prescription Fill and Return Visits for Complications .

Squares represent the point estimate, and lines and whiskers represent the 95% CIs. Only the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) for constipation was statistically significant (ie, the 95% CI did not include 1.0). Regressions adjusted for demographic variables (age, sex, US census division, and median educational level by census block); an indicator of whether the surgeon was a pediatric or general otolaryngologist; an indicator of tonsillectomy alone vs tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy; and indicators of recent diagnoses of obstructive sleep apnea, mental health disorders, and other chronic conditions.

Among the 15 793 children, 483 (3.1%) had a return visit for secondary hemorrhage. Among 9411 children with 1 or more perioperative fills, 300 (3.2%) had a return visit for secondary hemorrhage, compared with 183 (2.9%) of the 6382 children with 0 perioperative fill. In adjusted analyses, having 1 or more perioperative fills was not associated with return visits for secondary hemorrhage (AOR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.73-1.10). Factors associated with increased risk of visits for secondary hemorrhage included age (AOR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.04-1.09), other chronic condition (AOR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.09-1.64), pediatric otolaryngologist (AOR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.01-1.57), and having 1 or more late fills (AOR, 2.63; 95% CI, 2.05-3.38) (eTable 4 in the Supplement). Among children with 1 or more perioperative fills, duration was not associated with return visits for secondary hemorrhage (AOR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.99-1.04) (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Among the 15 793 children, 91 (0.6%) had a return visit for constipation. Among 9411 children with 1 or more perioperative fills, 65 (0.7%) had a return visit for constipation, compared with 26 (0.4%) of the 6382 children with 0 perioperative fills. In adjusted analyses, having 1 or more perioperative fills was associated with increased risk of return visits for constipation (AOR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.24-3.28). Additional factors associated with increased risk included other chronic condition (AOR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.06-2.61) and having 1 or more late fills (AOR, 2.25; 95% CI, 1.20-4.23) (eTable 6 in the Supplement). The association between age and risk of visits for constipation was nonlinear. Risk initially decreased as age increased (AOR for linear age, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.84-0.95), but the magnitude of the association became less negative with older age (AOR for age squared, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.01-1.03). Among children with 1 or more perioperative fills, duration was not associated with return visits for constipation (AOR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.94-1.05) (eTable 7 in the Supplement).

Among 9411 children with 1 or more perioperative fills, 1 (0.01%) had a return visit for opioid overdose. This child had 0 late fill.

Sensitivity Analyses

In sensitivity analyses, we analyzed pain and dehydration separately as well as vomiting as an additional outcome. Having 1 or more perioperative fills was not associated with return visits for pain (AOR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.81-1.25), dehydration (AOR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.96-1.50), or vomiting (AOR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.80-1.47). Among children with 1 or more perioperative fills, duration was not associated with return visits for pain (AOR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.99-1.02), dehydration (AOR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.99-1.04), or vomiting (AOR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.94-1.05).

Discussion

In this national study of privately insured children after tonsillectomy in 2016 and 2017, the probability of perioperative opioid prescription fills and the duration of perioperative prescriptions varied widely. Perioperative fills and duration were not associated with return visits for pain or dehydration or secondary hemorrhage. However, perioperative fills were associated with increased risk of visits for constipation and with 1 opioid overdose. Findings from this study potentially support the feasibility of decreasing perioperative opioid prescribing and the duration of perioperative prescriptions in children after tonsillectomy.

This study provides recent national data on perioperative opioid prescribing patterns after pediatric tonsillectomy. Overall, 6 in 10 children had perioperative fills. Age was positively associated with having perioperative fills, potentially because surgeons were more likely to prescribe opioids owing to the painfulness of tonsillectomy in older children.17 Previous diagnoses for obstructive sleep apnea and other chronic conditions were negatively associated with having perioperative fills, suggesting that some surgeons may tailor their prescribing decisions according to patient comorbidities.

Among children with perioperative fills, the median prescription duration was 8 days. This duration exceeds most state and insurer limits on the duration of opioid prescriptions for acute pain, which typically restrict prescriptions to a 7-day supply and were mostly implemented in 2017 and 2018.18,19 Age and having a pediatric otolaryngologist perform the tonsillectomy were associated with shorter duration. In addition, duration varied widely between census divisions, suggesting that local practice patterns may partially be associated with prescribing decisions. To reduce unwarranted variation, collecting data on opioid requirements after tonsillectomy is important.18,20,21,22 A previous single-institution study found that children who underwent tonsillectomy had 43.8 leftover opioid doses on average, suggesting that prescribing sometimes far exceeds pain needs.23 Larger-scale efforts to collect data on opioid consumption could help develop evidence-based prescribing guidelines, which have been associated with reduced prescribing without increased refills in other surgical contexts.24

Perioperative fills and prescription duration were not associated with return visits for pain or dehydration. These associations could be confounded by pain severity, which may affect a surgeon's decision to provide perioperative opioid prescriptions, a family's decision to fill these prescriptions, and a family's decision to seek care for inadequate analgesia. Consequently, the findings do not negate the possibility that perioperative fills could prevent visits for pain or dehydration, although opioids were not superior to nonopioids for analgesia in randomized clinical trials.5,6

Similarly, perioperative fills and prescription duration were not associated with return visits for secondary hemorrhage. Because the lack of perioperative fills does not imply NSAID use, the findings only suggest that opioids may not be superior to nonopioid regimens for preventing secondary hemorrhage. Despite this caveat, the findings in this study are consistent with several studies that did not find statistically significant differences in hemorrhage rates between children who used opioids and those who used NSAIDs.7,8,9,10 Late fills were associated with increased risk of secondary hemorrhage. The reason for this finding was unclear, but we hypothesized that some late fills were opioids prescribed to minimize NSAID use once secondary hemorrhage had occurred.

Perioperative fills were associated with increased risk of visits for constipation, although prescription duration was not, contrary to our hypothesis. In addition, 1 (0.01%) of the 9411 children with a perioperative fill experienced opioid overdose, an overdose rate similar to that reported in a national study of adults prescribed opioids after surgical procedures.25 The risks of constipation and overdose, along with the risks of respiratory complications and new persistent opioid use,12 are important considerations when planning postoperative pain management with families.26 More broadly, these risks underscore the importance of ongoing opioid stewardship initiatives in otolaryngology and other surgical specialties.27,28,29,30,31

In this study, 3.3% of children had perioperative fills for codeine, despite a 2013 black box warning that contraindicated codeine in children younger than 18 years after tonsillectomy.32 A previous national study demonstrated that 5% of privately insured children had codeine prescription fills after tonsillectomy in December 2015.33 Although codeine prescribing may have decreased, quality improvement efforts are still needed to eliminate this practice. The 2019 tonsillectomy guidelines of the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery discourage the use of codeine for children younger than 12 years,4 but 2.7% of such children in the present study had perioperative fills for codeine.

In addition, 0.7% of children had perioperative fills for tramadol. In April 2017, a time point captured by this study, another black box warning contraindicated tramadol for children younger than 18 years after tonsillectomy.34 We believe that future research should assess whether tramadol prescribing after tonsillectomy persists, as it has for codeine.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the results could be confounded by unmeasured factors such as surgical technique, intraoperative medication administration, pain severity, or patient and family attitudes toward opioids. Second, the claims database records only filled opioid prescriptions reimbursed through insurance. Consequently, the reported rate of perioperative fills may underestimate prescribing. Third, children may not use opioids even when prescriptions are filled. Fourth, the lack of return visits for pain or dehydration does not necessarily mean that severe pain did not occur. Fifth, we may have undercounted opioid overdoses, as diagnosis codes have high specificity but low sensitivity for detecting overdose.35,36 Sixth, results may not generalize to publicly insured children. Moreover, because the sample overrepresented the South and Midwest census divisions, the results may not generalize to other privately insured children.

Conclusions

The findings of this study do not appear to contradict the American Academy of Otolaryngology national guidelines recommending nonopioids as a first-line option for posttonsillectomy analgesia in children.4 We believe these findings highlight the need to identify the appropriate duration of therapy when opioids are prescribed for children after tonsillectomy.

eAppendix. List of Opioid Analgesics

eTable 1. Codes Used in Study

eTable 2. Association Between Perioperative Fills and Return Visits for Pain or Dehydration

eTable 3. Association Between Duration of Perioperative Prescriptions and Return Visits for Pain or Dehydration Among Patients With Perioperative Fills

eTable 4. Association Between Perioperative Fills and Return Visits for Secondary Hemorrhage

eTable 5. Association Between Duration of Perioperative Prescriptions and Return Visits for Secondary Hemorrhage Among Patients With Perioperative Fills

eTable 6. Association Between Perioperative Fills and Return Visits for Constipation

eTable 7. Association Between Duration of Perioperative Prescriptions and Return Visits for Constipation Among Patients With Perioperative Fills

References

- 1.Cullen KA, Hall MJ, Golosinskiy A. Ambulatory surgery in the United States, 2006. Natl Health Stat Report. 2009;(11):1-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauder G, Emmott A. Confronting the challenges of effective pain management in children following tonsillectomy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78(11):1813-1827. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baugh RF, Archer SM, Mitchell RB, et al. ; American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation . Clinical practice guideline: tonsillectomy in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144(1)(suppl):S1-S30. doi: 10.1177/0194599810389949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell RB, Archer SM, Ishman SL, et al. Clinical practice guideline: tonsillectomy in children (update). Executive Summary. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;160(2):187-205. doi: 10.1177/0194599818807917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly LE, Sommer DD, Ramakrishna J, et al. Morphine or ibuprofen for post-tonsillectomy analgesia: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):307-313. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.St Charles CS, Matt BH, Hamilton MM, Katz BP. A comparison of ibuprofen versus acetaminophen with codeine in the young tonsillectomy patient. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117(1):76-82. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(97)70211-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mudd PA, Thottathil P, Giordano T, et al. Association between ibuprofen use and severity of surgically managed posttonsillectomy hemorrhage. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143(7):712-717. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2016.3839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pfaff JA, Hsu K, Chennupati SK. The use of ibuprofen in posttonsillectomy analgesia and its effect on posttonsillectomy hemorrhage rate. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;155(3):508-513. doi: 10.1177/0194599816646363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riggin L, Ramakrishna J, Sommer DD, Koren G. A 2013 updated systematic review & meta-analysis of 36 randomized controlled trials; no apparent effects of non steroidal anti-inflammatory agents on the risk of bleeding after tonsillectomy. Clin Otolaryngol. 2013;38(2):115-129. doi: 10.1111/coa.12106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis SR, Nicholson A, Cardwell ME, Siviter G, Smith AF. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and perioperative bleeding in paediatric tonsillectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(7):CD003591. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003591.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown KA. Intermittent hypoxia and the practice of anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2009;110(4):922-927. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819c480a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harbaugh CM, Lee JS, Hu HM, et al. Persistent opioid use among pediatric patients after surgery. Pediatrics. 2018;141(1):e20172439. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mattos JL, Robison JG, Greenberg J, Yellon RF. Acetaminophen plus ibuprofen versus opioids for treatment of post-tonsillectomy pain in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78(10):1671-1676. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.IBM IBM Micromedex RED BOOK. https://www.ibm.com/us-en/marketplace/micromedex-red-book. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- 15.Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):85-92. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simon TD, Cawthon ML, Stanford S, et al. ; Center of Excellence on Quality of Care Measures for Children with Complex Needs (COE4CCN) Medical Complexity Working Group . Pediatric medical complexity algorithm: a new method to stratify children by medical complexity. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):e1647-e1654. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alm F, Stalfors J, Nerfeldt P, Ericsson E. Patient reported pain-related outcome measures after tonsil surgery: an analysis of 32,225 children from the National Tonsil Surgery Register in Sweden 2009-2016. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274(10):3711-3722. doi: 10.1007/s00405-017-4679-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chua KP, Brummett CM, Waljee JF. Opioid prescribing limits for acute pain: potential problems with design and implementation. JAMA. 2019;321(7):643-644. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Conference of State Legislatures Prescribing policies: states confront opioid overdose epidemic. http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/prescribing-policies-states-confront-opioid-overdose-epidemic.aspx. Published October 31, 2018. Accessed April 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howard R, Fry B, Gunaseelan V, et al. Association of opioid prescribing with opioid consumption after surgery in Michigan [published online November 17, 2018]. JAMA Surg. 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.4234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill MV, Stucke RS, Billmeier SE, Kelly JL, Barth RJ Jr. Guideline for discharge opioid prescriptions after inpatient general surgical procedures. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(6):996-1003. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monitto CL, Hsu A, Gao S, et al. Opioid prescribing for the treatment of acute pain in children on hospital discharge. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(6):2113-2122. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Voepel-Lewis T, Wagner D, Tait AR. Leftover prescription opioids after minor procedures: an unwitting source for accidental overdose in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(5):497-498. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howard R, Waljee J, Brummett C, Englesbe M, Lee J. Reduction in opioid prescribing through evidence-based prescribing guidelines. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(3):285-287. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ladha KS, Gagne JJ, Patorno E, et al. Opioid overdose after surgical discharge. JAMA. 2018;320(5):502-504. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.6933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Voepel-Lewis T, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Boyd CJ, et al. Effect of a scenario-tailored opioid messaging program on parents’ risk perceptions and opioid decision-making. Clin J Pain. 2018;34(6):497-504. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartels K, Mayes LM, Dingmann C, Bullard KJ, Hopfer CJ, Binswanger IA. Opioid use and storage patterns by patients after hospital discharge following surgery. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steyaert A, Lavand’homme P. Postoperative opioids: let us take responsibility for the possible consequences. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2013;30(2):50-52. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32835b9db2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cramer JD, Wisler B, Gouveia CJ. Opioid stewardship in otolaryngology: state of the art review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;158(5):817-827. doi: 10.1177/0194599818757999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alam A, Gomes T, Zheng H, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, Bell CM. Long-term analgesic use after low-risk surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):425-430. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oltman J, Militsakh O, D’Agostino M, et al. Multimodal analgesia in outpatient head and neck surgery: a feasibility and safety study. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143(12):1207-1212. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.1773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.US Food and Drug Administration Safety review update of codeine use in children; new boxed warning and contraindication on use after tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy. Safety announcement. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/UCM339116.pdf. Published February 20, 2013. Accessed April 1, 2017.

- 33.Chua KP, Shrime MG, Conti RM. Effect of FDA investigation on opioid prescribing to children after tonsillectomy/adenoidectomy. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6):e20171765. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.US Food and Drug Administration FDA restricts use of prescription codeine pain and cough medicines and tramadol pain medicines in children; recommends against use in breastfeeding women. Safety announcement. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/UCM553814.pdf. Published April 20, 2017. Accessed February 20, 2018.

- 35.Chung CP, Callahan ST, Cooper WO, et al. Development of an algorithm to identify serious opioid toxicity in children. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:293. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1185-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowe C, Vittinghoff E, Santos GM, Behar E, Turner C, Coffin PO. Performance measures of diagnostic codes for detecting opioid overdose in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(4):475-483. doi: 10.1111/acem.13121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. List of Opioid Analgesics

eTable 1. Codes Used in Study

eTable 2. Association Between Perioperative Fills and Return Visits for Pain or Dehydration

eTable 3. Association Between Duration of Perioperative Prescriptions and Return Visits for Pain or Dehydration Among Patients With Perioperative Fills

eTable 4. Association Between Perioperative Fills and Return Visits for Secondary Hemorrhage

eTable 5. Association Between Duration of Perioperative Prescriptions and Return Visits for Secondary Hemorrhage Among Patients With Perioperative Fills

eTable 6. Association Between Perioperative Fills and Return Visits for Constipation

eTable 7. Association Between Duration of Perioperative Prescriptions and Return Visits for Constipation Among Patients With Perioperative Fills