Key Points

Question

Can the Clinical Effort Against Secondhand Smoke Exposure intervention help parents quit smoking in the context of pediatric practices?

Findings

In this cluster randomized clinical trial, after initial intervention implementation, 44% of parents received cessation assistance in intervention practices, compared with less than 1% in control practices. Over the 2-year study period, intervention practices had a 2.7% decrease in the smoking rate in parents, compared with a 1.1% increase in control practices.

Meaning

In this trial, implementing a program to treat parents for tobacco use within pediatric offices was associated with markedly higher rates of tobacco treatment delivery and a decline in practice-level parent smoking rates compared with a control group of practices that delivered usual care.

This cluster randomized clinical trial examines the rate at which a tobacco use cessation program implemented in pediatric offices convinces parents who currently smoke to quit.

Abstract

Importance

Despite the availability of free and effective treatment, few pediatric practices identify and treat parental tobacco use.

Objective

To determine if the Clinical Effort Against Secondhand Smoke Exposure (CEASE) intervention can be implemented and sustained in pediatric practices and test whether implementing CEASE led to changes in practice-level prevalence of smoking among parents over 2 years.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cluster randomized clinical trial was conducted from April 2015 to October 2017. Ten pediatric practices in 5 states were randomized to either implement the CEASE protocol or maintain usual care (as a control group). All parents who screened positive for tobacco use by exit survey after their child’s clinical visit 2 weeks (from April to October 2015) and 2 years after intervention implementation (April to October 2017) were eligible to participate. Data analysis occurred from January 2018 to March 2019.

Interventions

The CEASE intervention is a practice-change intervention designed to facilitate both routine screening in pediatric settings of families for tobacco use and delivery of tobacco cessation treatment to individuals in screened households who use tobacco.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was delivery of meaningful tobacco treatment, defined as the prescription of nicotine replacement therapy or quit line enrollment. Furthermore, changes in practice-level smoking prevalence and cotinine-confirmed quit rates over the 2 years of intervention implementation were assessed.

Results

Of the 8184 parents screened after their child's visit 2 weeks after intervention implementation, 961 (27.1%) were identified as currently smoking in intervention practices; 1103 parents (23.9%) were currently smoking in control practices. Among the 822 and 701 eligible parents who completed the survey in intervention and control practices, respectively 364 in the intervention practices (44.3%) vs 1 in a control practice (0.1%) received meaningful treatment at that visit (risk difference, 44.0% [95% CI, 9.8%-84.8%]). Two years later, of the 9794 parents screened, 1261 (24.4%) in intervention practices and 1149 (25.0%) in control practices were identified as currently smoking. Among the 804 and 727 eligible parents completing the survey in intervention and control practices, respectively, 113 in the intervention practices (14.1%) vs 2 in the control practices (0.3%) received meaningful treatment at that visit (risk difference, 12.8% [95% CI, 3.3%-37.8%]). Change in smoking prevalence over the 2 years of intervention implementation favored the intervention (−2.7% vs 1.1%; difference −3.7% [95% CI, −6.3% to −1.2%]), as did the cotinine-confirmed quit rate (2.4% vs −3.2%; difference, 5.5% [95% CI, 1.4%-9.6%]).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this trial, integrating screening and treatment for parental tobacco use in pediatric practices showed both immediate and long-term increases in treatment delivery, a decline in practice-level parental smoking prevalence, and an increase in cotinine-confirmed cessation, compared with usual care.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01882348

Introduction

Tobacco use and involuntary smoke exposure cause an estimated 480 000 premature deaths annually.1,2 Pediatric office visits represent an opportunity to deliver tobacco cessation assistance to parents.3 The 2015 American Academy of Pediatrics tobacco policy recommends that health care systems facilitate identification of children exposed to tobacco and treat parental tobacco dependence.1 In addition to improving parents’ health, parental cessation is associated with improvements to children’s health,2,4,5 reductions in teens’ smoking initiation,6,7,8,9,10 and greater likelihood in future smoke-free pregnancies.11

Clinician counseling, telephone quit lines, and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) improve the likelihood of quitting.12 Combining treatments is more effective than individual interventions alone.12 Despite such evidence and recommendations, systematic parental tobacco cessation treatments are not delivered in most pediatric settings. A 2013 study found that only 3.5% of parents who smoke received meaningful treatment (eg, discussing quit strategies, prescribing pharmacotherapy, or referring parents to the quit line) in pediatric practices.13

Clinical Effort Against Secondhand Smoke Exposure (CEASE) is a practice-change intervention aimed at routinely screening families for tobacco use and delivering cessation assistance in pediatric clinician’s offices.3,13,14,15,16 Early versions of CEASE were paper based14,15; barriers to implementation and sustainability included lack of systems-level integration of the intervention into routine care, time limitations of clinical visits, an inability to efficiently identify parents requiring cessation assistance, and a lack of easy methods for referral to cessation resources.14 For this study, a tablet was used in pediatric offices to screen families for tobacco use, with the goal of increasing the proportion of families screened and offered assistance.

The study tested the effectiveness and sustainability of the enhanced CEASE intervention vs usual care for smoking-cessation assistance to parent who smoked in pediatric practices. It assessed the change in practice-level smoking prevalence and cotinine-confirmed quit rates between groups over 2 years.

Methods

Practice Enrollment and Randomization

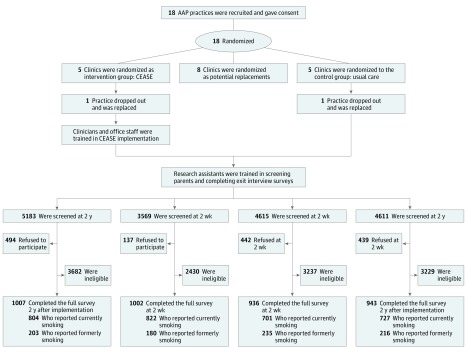

Practices were recruited through the American Academy of Pediatrics. To enhance generalizability, we recruited and enrolled a control, intervention, and replacement practice in each of 5 states, as well as a replacement state with a control, intervention, and replacement practice. The initial criterion to help ensure that an adequate number of parents who smoke would be enrolled in each practice were a parental smoking prevalence of 15% or more, a mean patient flow of 50 families per day or more, 4 or more full-time clinicians, and the use of an electronic health record system. Because of slow recruitment, the criteria of 4 or more full-time employees was removed to adhere to the study timeline, and 2 practices with 3 full-time clinicians were recruited to assess for eligibility. Practices that expressed interest conducted 3-day practice population surveys to confirm eligibility for randomization. Practices were eligible if they saw a minimum of 9 families that each had at least 1 parent who was smoking (as a proxy for a rate of smoking among parents) and a minimum of 40 families per day (as a proxy for practice flow rate). The Figure outlines the study design. (The protocol is presented in Supplement 1.) Eighteen pediatric practices were eligible from 6 states and were randomized via a random-number generator to the CEASE intervention, usual-care control group, or a replacement group. The practices were not blinded to group assignment. The final 5 study states were North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, Ohio, and Indiana. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at the American Academy of Pediatrics, Massachusetts General Hospital, and individual practices, when required.

Figure. Randomization Design.

AAP indicates American Academy of Pediatrics; CEASE, Clinical Effort Against Secondhand Smoke Exposure.

Parent Eligibility

Research assistants at intervention and control practices attempted to screen all parents after their child’s visit using the screening survey, starting 2 weeks after the intervention implementation and again 2 years later. Parents were eligible for a detailed survey if they indicated that they were the child’s parent or legal guardian and reported having smoked a cigarette (even a single puff) in the past 7 days (the group categorized as currently smoking) or having quit smoking in the past 2 years (the group categorized as formerly smoking). Exclusion criteria specified parents younger than 18 years, those whose child had a medical emergency, individuals who did not speak English, and those who had previously completed the detailed survey. Eligible parents who agreed to do the detailed survey provided consent and received $5 on completion. Parents who reported not smoking in the last 7 days were asked to provide a saliva sample to confirm quit status and received an additional $20. At 2 weeks and 2 years postintervention, research assistants screened parents until approximately 200 eligible parents per practice had completed the detailed survey. Owing to slow recruitment in the North Carolina control practice, an additional pediatric office affiliated with the practice was included. Recruitment at these 2 practices was stopped at 137 surveys total to adhere to the study timeline. The same procedures were used for the 2-year postintervention measurements.

Intervention

The CEASE intervention is integrated into existing systems of care to routinely address parental smoking and smoke exposure of all family members, using the ask, assist, and refer approach.17 Most clinical and support staff training was conducted via telephone, online learning courses, a training video, and a training manual (for reference).17 Ongoing training of new staff, assistance, and materials were tailored to individual practices.

Staff distributed the tablet-based household tobacco use screening instrument to parents at each visit during check-in or before they saw the health care professional. Screening information was managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) data capture tools hosted at Partners Healthcare.18 The CEASE study team monitored parent screening by the practice for 2 years. Electronic screening allowed for real-time monitoring; the team alerted practices when screening numbers dropped to less than their mean daily numbers as determined by the practice population survey flow rate, prompting a discussion of strategies to increase screening rates. Office staff handed a CEASE action sheet to families that reported having a member who was currently smoking, even when the individual was not at the visit. This sheet included prescriptions for NRT, information about a free cessation-support text-messaging service (SmokefreeTXT),19 and reminders for the clinician to recommend quit line enrollment. The tablets were automated to prompt staff to distribute quit line enrollment forms to all parents who were currently smoking and who indicated interest in the quit line. The enrollment forms were faxed to their state quit line by practice staff; a quit line coach subsequently made proactive attempts to contact the parent.

Participating clinicians were trained to help interested smokers set a quit date, set smoke-free home and car rules, and encourage NRT use. A member of the CEASE team contacted pharmacies near the intervention practices to inform them about the program and update them on NRT coverage changes from the Affordable Care Act.20 The electronically collected tobacco-use screening information was used to create a registry of children exposed to tobacco smoke, with monthly reports sent to each clinician to enhance documentation of parental smoking, confirm that requests for assistance were fulfilled, and foster follow-up with individuals who smoked.

Measures, Outcomes, and Data Analysis

Cross-sectional exit survey data were collected 2 weeks (April to October 2015) and 2 years (April to October 2017) after intervention implementation. Exit interview data were chosen over medical record review because the data have been shown to be more accurate than record review21,22 and almost as accurate as direct observation of clinician behavior.23,24

We assessed meaningful tobacco treatment delivery, defined as parents responding yes to questions about receiving either prescription of medication or referral to the state quit line at that office visit. Questions to assess tobacco treatment delivery were used in prior studies.13,25,26

To assess implementation and sustainability of the intervention, we examined meaningful tobacco treatment delivered at 2 weeks and 2 years after intervention implementation. Only parents who reported currently smoking are included in this analysis. We compared rates of treatment delivery using multivariable logistic regression with generalized estimating equations to account for physician clustering within practices. We included parent and child characteristics that showed imbalance (defined as P < .10) from the bivariate analyses in the models.

To assess the intervention’s effect on tobacco use, we compared change in current smoking prevalence from 2 weeks to 2 years after intervention implementation, as assessed by the exit survey screener. Parents were considered to be current smokers if they answered yes to the question, “Have you smoked a cigarette, even a puff, in the past 7 days?”

To assess cotinine-confirmed quit rate and validate comparability of self-reported smoking status between the groups, we tested salivary cotinine in parents who reported quitting in the past 2 years. Parents were considered to have quit if they reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes in their life and smoking a cigarette (even a puff) in the past 2 years but not in the past 7 days. Parents were considered to have cotinine-confirmed quit status if their cotinine level was less than 10 ng/mL (to convert to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 5.675) or if they reported using NRT in the past 7 days. Parents with missing cotinine data were categorized as currently smoking.

Since we expected a much smaller outcome from the cotinine-confirmed quit rate outcome than from the primary outcome of cessation-assistance delivery, the sample-size calculation was conducted based on the quit rate difference at 2 years after implementation. We assumed an α of .05 with 80% power and a 2-tailed test of significance, and 10 total practices (5 in the intervention group and 5 in the control group) completing the full study protocol and recruiting the necessary number of parent participants. We assumed a cotinine-confirmed quit rate of 7.5% in the control group and 12.5% in the intervention group, which requires a total sample size of 1190 individuals. With the assumptions of an intraclass correlation of 0.017 (based on the mean value from a previous study27) and a total of 60 clinicians, we estimated we needed a total of 1844 participants to take the clustering effect into account.

After observing a nonneglectable group difference in smoking prevalence at the first period, we used difference-in-differences analyses for both cotinine-confirmed quit rate and self-reported smoking status by testing the group and time interaction in logistic regression models adjusting for state, parent demographic factors (eg, age, sex, and race) and child characteristics (eg, age and insurance status). For the cotinine-confirmed quit rate, we also conducted sensitivity analysis accounting for clinician clustering. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Data were analyzed from January 2018 to March 2019.

Results

Research assistants screened 8184 parents exiting pediatric practices 2 weeks after intervention implementation. Of these, 961 parents (27.1%) in the intervention practices, and 1103 parents (23.9%) in the control practices were identified as currently smoking. Among eligible individuals who were currently smoking, 822 (89.0%) in the intervention practices and 701 (67.0%) in the control practices agreed to participate in the detailed survey. Two years later, 9794 parents were screened when exiting the pediatric practices. Of these, 1261 parents (24.4%) were currently smoking in the intervention practices, and 1149 parents (25.0%) were currently smoking in the control practices. Among those who were currently smoking, 804 parents (68.4%) in the intervention practices and 727 parents (68.0%) in the control practices agreed to the detailed survey (Figure).

Table 1 presents characteristics of parents who were identified as currently smoking and completed the survey at 2 weeks and 2 years after intervention implementation. Overall, 1052 parents (69.1%) were 25 to 44 years old at 2 weeks after intervention implementation and 1111 (72.6%) were 25 to 44 years old at 2 years after intervention implementation. Compared with the control group, the intervention group had more non-Hispanic white parents (at 2 weeks: control, 567 [80.8%] vs intervention, 752 [91.5%]; at 2 years: control, 610 [83.9%] vs intervention, 710 [88.3%]) and more children on Medicaid (at 2 weeks: control, 489 [69.8%] vs intervention, 684 [83.2%]; at 2 years: control, 431 [59.3%] vs intervention, 617 [76.7%]) than at both periods. Overall, 686 parents (45.0%) and 617 parents (40.3%) who currently smoked planned to quit in the next 30 days at the 2-week and 2-year survey points, respectively.

Table 1. Characteristics of Parents Who Currently Smoke per Surveys at 2 Weeks and 2 Years After Intervention Implementationa.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 wk After Implementation | 2 y After Implementation | |||

| Control (n = 701) | Intervention (n = 822) | Control (n = 727) | Intervention (n = 804) | |

| Age, y | ||||

| 18-24 | 138 (19.7) | 159 (19.3) | 115 (15.8) | 144 (17.9) |

| 25-44 | 486 (69.3) | 566 (68.9) | 533 (73.3) | 578 (71.9) |

| ≥45 | 77 (11.0) | 97 (11.8) | 79 (10.9) | 82 (10.2) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 109 (15.5) | 164 (20.0) | 123 (16.9) | 177 (22.0) |

| Female | 592 (84.5) | 658 (80.0) | 604 (83.1) | 627 (78.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 16 (2.3) | 25 (3.0) | 11 (1.5) | 28 (3.5) |

| Other | 19 (2.7) | 11 (1.3) | 18 (2.5) | 24 (2.9) |

| Non-Hispanic black or African American | 78 (11.1) | 23 (2.8) | 72 (9.9) | 25 (3.1) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 2 (0.3) | 4 (0.5) | 0 | 2 (0.2) |

| Non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian or other | 19 (2.7) | 7 (0.9) | 16 (2.2) | 15 (1.9) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 567 (80.8) | 752 (91.5) | 610 (83.9) | 710 (88.3) |

| Education | ||||

| <High school | 79 (11.3) | 145 (17.6) | 99 (13.6) | 106 (13.2) |

| High school graduate | 310 (44.2) | 340 (41.4) | 340 (46.8) | 355 (44.2) |

| Some college | 239 (34.1) | 261 (31.8) | 200 (27.5) | 285 (35.4) |

| College graduate | 73 (10.4) | 76 (9.2) | 84 (11.6) | 58 (7.2) |

| Cigarettes, No./d | ||||

| 1-9 | 270 (38.5) | 236 (28.7) | 287 (39.5) | 280 (34.8) |

| ≥10 | 430 (61.3) | 582 (70.8) | 438 (60.2) | 520 (64.7) |

| Plan to quit | ||||

| Next 30 d | 312 (44.5) | 374 (45.5) | 277 (38.1) | 340 (42.3) |

| Next 6 mo | 211 (30.1) | 213 (25.9) | 199 (27.4) | 233 (29.0) |

| None in the next 6 mo | 138 (19.7) | 150 (18.2) | 215 (29.6) | 169 (21.0) |

| Unknown | 40 (5.7) | 85 (10.3) | 36 (5.0) | 62 (7.7) |

| Quit attempt in the past 3 mo | 388 (55.3) | 344 (41.8) | 359 (49.4) | 389 (48.4) |

| Daily smoker | 595 (84.9) | 732 (89.1) | 594 (81.7) | 664 (82.6) |

| Age of youngest child seen, y | ||||

| <1 | 162 (23.1) | 179 (21.8) | 148 (20.4) | 189 (23.5) |

| 1-4 | 215 (30.7) | 267 (32.5) | 211 (29.0) | 247 (30.7) |

| 5-9 | 167 (23.8) | 175 (21.3) | 174 (23.9) | 179 (22.3) |

| 10-14 | 114 (16.3) | 134 (16.3) | 153 (21.0) | 137 (17.0) |

| ≥15 | 43 (6.1) | 67 (8.2) | 41 (5.6) | 51 (6.3) |

| Strict smoke-free policies in home and car | ||||

| Home | 407 (58.1) | 486 (59.1) | 444 (61.1) | 523 (65.0) |

| Car | 213 (30.4) | 261 (31.8) | 265 (36.5) | 251 (31.2) |

| Any other forms of tobacco used | ||||

| Pipe | 4 (0.6) | 7 (0.9) | 5 (0.7) | 15 (1.9) |

| Chew tobacco | 13 (1.9) | 31 (3.8) | 20 (2.8) | 36 (4.5) |

| Electronic cigarettes | 95 (13.6) | 147 (17.9) | 81 (11.1) | 82 (10.2) |

| Hookah | 1 (0.1) | 8 (1.0) | 7 (1.0) | 7 (0.9) |

| Assistance used the last 2 y to help quit | ||||

| Nicotine replacement therapy | 158 (22.5) | 188 (22.9) | 165 (22.7) | 268 (33.3) |

| Quit line | 41 (5.8) | 57 (6.9) | 31 (4.3) | 115 (14.3) |

| Website | 25 (3.6) | 32 (3.9) | 21 (2.9) | 54 (6.7) |

| Child’s insurance coverage | ||||

| Medicaid | 489 (69.8) | 684 (83.2) | 431 (59.3) | 617 (76.7) |

| Private insurance/HMO | 202 (28.8) | 119 (14.5) | 263 (36.2) | 162 (20.1) |

| Other/self-pay | 9 (1.3) | 14 (1.7) | 28 (3.8) | 22 (2.7) |

| Type of visit | ||||

| Well child | 338 (48.2) | 413 (50.2) | 394 (54.2) | 406 (50.5) |

| Follow-up | 79 (11.3) | 71 (8.6) | 59 (8.1) | 77 (9.6) |

| Sick visit | 226 (32.2) | 268 (32.6) | 181 (24.9) | 221 (27.5) |

| Other | 58 (8.3) | 69 (8.4) | 93 (12.8) | 100 (12.4) |

| Visits to clinician’s office in the last 2 y, median (IQR) | ||||

| Pediatricb | 8 (4-15) | 7 (4-15) | 8 (4-15) | 6 (4-12) |

| Own physician | 4 (2-10) | 4 (2-13) | 4 (2-10) | 4 (2-12) |

Abbreviations: HMO, health maintenance organization; IQR, interquartile range.

Total numbers vary slightly among items because of missing data.

Including the visit on the day the survey was collected.

For the primary outcome of meaningful treatment delivery, 364 parents (44.3%) who currently smoke in the intervention group vs 1 parent (0.1%) in the control group (P < .001) reported receiving a prescription for NRT or being enrolled in the quit line at 2 weeks after intervention implementation. Similarly, meaningful treatment delivery was reported by 113 parents (14.1%) in the intervention group vs 2 parents (0.3%) in the control group (P < .001) at the 2-year postimplementation point (Table 2). These differences remained significant after adjusting for differences in parent characteristics. A larger proportion of parents who reported currently smoking in the intervention group vs the control group reported discussing any cessation assistance (NRT or quit line) at 2 weeks (485 [59.0%] vs 8 [1.1%]) and 2 years after intervention implementation period (257 [32.0%] vs 24 [3.3%]). Among the 485 parents who were currently smoking and were provided any assistance at 2 weeks after intervention implementation period in the intervention group, 364 (75.1%) accepted treatment (received a prescription or quit line enrollment) when it was discussed in the intervention practices, and 113 of 257 parents (43.9%) accepted treatment as of 2 years after intervention implementation. Of parents who reported 2 years after implementation that they were not currently smoking and had used medication in the past 2 years to help them quit, 11 (31.4%) in the intervention practices and 0 parents in control practices reported receiving the NRT prescription from their child’s doctor.

Table 2. Parents Who Currently Smoke Who Received Any Tobacco Treatment at 2 Weeks and 2 Years After Intervention Implementation.

| Type of Help | 2 wk After Implementation | 2 y After Implementation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, No. (%) | Adjusted Risk Differences (95% CI)a | Patients, No. (%) | Adjusted Risk Differences (95% CI)b | |||

| Control (n = 701) | Intervention (n = 822) | Control (n = 727) | Intervention (n = 804) | |||

| Meaningful treatmentc | 1 (0.1) | 364 (44.3) | 44.0 (9.8-84.8) | 2 (0.3) | 113 (14.1) | 12.8 (3.3-37.8) |

| Any assistanced | 8 (1.1) | 485 (59.0) | 50.1 (25.5-74.2) | 24 (3.3) | 257 (32.0) | 33.1 (13.2-59.1) |

| Questioning by clinician | ||||||

| On smoking status | 156 (22.3) | 617 (75.4) | 52.4 (40.5-61.5) | 135 (18.7) | 387 (48.1) | 29.1 (17.5-41.0) |

| On smoke-free home status | 198 (28.3) | 570 (69.8) | 43.1 (31.6-52.4) | 168 (23.2) | 378 (47.1) | 27.7 (14.6-40.6) |

| On smoke-free car status | 126 (18.1) | 534 (65.4) | 48.2 (35.4-59.0) | 119 (16.5) | 319 (39.7) | 26.4 (14.7-38.9) |

| Advice from clinician | ||||||

| To quit | 95 (13.6) | 521 (63.7) | 44.5 (31.0-56.9) | 85 (11.7) | 313 (38.9) | 26.2 (12.7-41.8) |

| To have a smoke-free home | 149 (21.3) | 532 (64.9) | 43.2 (30.1-54.5) | 118 (16.3) | 319 (39.7) | 25.0 (13.4-37.7) |

| To have a smoke-free car | 123 (17.6) | 516 (62.9) | 43.8 (30.5-55.6) | 104 (14.4) | 296 (36.9) | 24.5 (12.8-37.6) |

| Discussion with clinician | ||||||

| On medicine to quit | 3 (0.4) | 466 (56.8) | 46.3 (20.0-74.6) | 16 (2.2) | 250 (31.2) | 29.1 (10.8,56.0) |

| On enrollment in state quit line | 7 (1.0) | 414 (50.6) | 40.7 (20.0-64.7) | 15 (2.1) | 161 (20.1) | 17.3 (5.1-41.0) |

| Prescribe nicotine replacement therapy | 1 (0.1) | 325 (39.6) | 38.3 (7.9-81.6) | 2 (0.3) | 102 (12.8) | 11.4 (2.9-34.9) |

| Enroll in quit line | 1 (0.1) | 246 (30.1) | 29.4 (5.4-74.9) | 0 (0) | 66 (8.2) | 8.2 (6.3-10.1)e |

Adjusted risk differences, adjusted for parent sex, race, education, cigarettes per day, plan to quit, quit attempt, daily smoker, electronic cigarette use, and child’s insurance status.

Adjusted risk differences, adjusted for parent age, sex, race, education, cigarettes per day, plan to quit, child’s age, and child’s insurance status.

Defined as either prescription of nicotine replacement therapy or enrollment in the state quit line during the visit on the day the contact occurred.

Such as discussing nicotine replacement therapy or quit line enrollment.

Unadjusted risk difference.

Table 3 shows a 2.7% reduction in intervention practice population-level smoking prevalence over the course of 2 years compared with a 1.1% increase in usual-care control practices (absolute rate difference, −3.7% [95% CI, −6.3% to −1.2%]). The number needed to treat to reduce 1 individual who smokes is 27 individuals. The 4 intervention practices in Indiana, North Carolina, Ohio, and Tennessee showed a reduction in the prevalence of parents who currently smoked over the course of 2 years, but prevalence increased in the Virginia intervention practice by 2.3%. (Prevalence in the Virginia control practice increased by 3.7% during the same period.) Table 3 demonstrates the 2.4% increase in cotinine-confirmed quit rate in intervention practices vs 3.2% decrease in usual-care control practices seen at 2 years after intervention implementation (absolute rate difference, 5.5% [95% CI, 1.4%-9.6%]). Sensitivity analysis accounting for clinician clustering showed that group and time interaction remained significant (rate difference, 5.5% [95% CI, 0.05%-10.1%]; P = .04) for changes in cotinine-confirmed cessation after adjusting for state, parent age, sex, race, child age, and insurance. The number needed to treat to produce 1 confirmed incident of quitting is 18 individuals.

Table 3. Changes in Cotinine-Confirmed Cessation and Practice-Level Smoking Prevalence at 2 Weeks and 2 Years After Intervention Implementation.

| Characteristic | 2 wk After Implementation | 2 y After Implementation | Risk Differences, % (95% CI) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | |||

| Total parents screened, No. | 4615 | 3569 | 4611 | 5183 | NA | NA |

| Current smokers, No. (%) | 1103 (23.9) | 961 (27.1) | 1149 (25.0) | 1261 (24.4) | NA | NA |

| % Change in practice-level current smoking prevalence over 2 y | NA | NA | 1.1 | −2.7 | −3.7 (−6.3 to −1.2)a | .047 |

| Total individuals who currently smoke and formerly smoked who completed full survey, No.b | 936 | 1002 | 943 | 1007 | NA | NA |

| Cotinine-confirmed cessation, No. (%) | 135 (14.4) | 99 (9.8) | 106 (11.2) | 123 (12.2) | NA | NA |

| % Change in cessation over 2 y | NA | NA | −3.2 | 2.4 | 5.5 (1.4-9.6)a | .02 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Group and time interaction, adjusting for state, parent age, sex, race, child age, and insurance status.

Former smoking was defined as reporting quitting in the past 2 years.

Discussion

In this cluster randomized trial in pediatric practices in 5 states, implementation of the tablet-based CEASE intervention facilitated far higher rates of meaningful parental tobacco treatment than usual care, both at 2 weeks and 2 years after intervention implementation. Two years after implementation, a significant decrease in practice-level smoking prevalence and a significant increase in cotinine-confirmed quit rates was seen in intervention practices vs control practices.

A large proportion of parents in the study planned to quit in the next 30 days; this is considered the preparation stage for quitting smoking.28 This number is much higher than seen in the general population,29 suggesting that the pediatric visit is a teachable moment for cessation.30 A large number of parents accepted assistance when it was discussed at 2 weeks and at the point 2 years after intervention implementation. These data support results from other studies31,32 that show that parents who smoke are willing to accept cessation assistance when it is offered by their child’s health care professional.

Sustained rates of routinely screening families for household tobacco use, and subsequent delivery of meaningful treatment to parents who smoke33 in intervention practices demonstrates a true systems-level implementation of the intervention. Even though clinicians in the intervention group were still providing significantly higher rates of meaningful treatment compared with clinicians providing usual care in the control group, we observed a drop in meaningful treatment delivered in the intervention group after 2 years of implementation. Despite Affordable Care Act–mandated insurance coverage for NRT and communication with local pharmacies, some parents were unable to obtain NRT for free or the cost of a copayment. Some intervention improvement opportunities include better integration of household tobacco screening and assistance into pediatric electronic health record systems, improving insurance coverage of NRT and for clinicians’ time spent on parental tobacco control, and making delivery of parental cessation assistance a component of clinicians’ credentialing or evaluation processes.34

The study showed an overall moderate decrease in practice-level smoking prevalence in intervention practices compared with control practices. Study practices were chosen in states that had a higher smoking rate compared with the national US smoking rate. Even though the adult cigarette smoking rate in the US decreased from 2015 to 2017,35,36 the overall smoking rate in the study states remained almost the same or increased slightly, which is consistent with the control practices’ parental smoking prevalence in these states. The parental smoking prevalence in the intervention practices showed consistent reduction in 4 states, indicating the potential of pediatric health care setting interventions to reduce smoking prevalence in some of the most challenging tobacco control environments. In Virginia, the intervention-practice smoking prevalence increased by 2.3%, which was less than the 3.7% increase in the control practice. Overall, decreasing family-level smoking prevalence could yield major health benefits to the US population if the intervention were implemented nationally.

The significant increase in parents’ cotinine-confirmed cessation over the 2-year study period in the intervention practices compared with usual-care control practices demonstrates that improved cessation can be achieved, if pediatric health care offices screen parents for tobacco use and routinely offer tobacco-dependence treatment. A considerable number of parents (31.4%) in the intervention group who reported quitting and using NRT in the past 2 years reported that they got the NRT prescription from their child’s physician, compared with 0% in the control group. This showed that CEASE increased delivery of assistance to parents who may not have otherwise received it. These data also suggest that the higher quit rate in the intervention practices may be attributable to the tobacco-dependence treatment received in the pediatric practice.

Limitations

The study had several limitations. Volunteer practices that enrolled in the study may have been more motivated than general pediatric practices to participate in the CEASE intervention. The research assistants were not blinded to the practice’s study-arm assignment, but they were trained to use the same standard protocol and language to approach all parents exiting practices, to ensure validity of the collected data. We do not have data on the total visits during the data collection period, but the research assistants attempted a complete sequential capture of every parent who exited the pediatric practice with their child after the visit.

The use of a difference-in-differences analysis allows each clinic to serve as its own control for demographic and visit-type variables. Although the same protocol was used to approach all parents, larger percentages of individuals who were currently smoking consented in the intervention compared with control practices at 2 weeks after intervention implementation, possibly because of unplanned priming as a result of the intervention. However, the consent rate did not appear to have any correlation with the change in smoking prevalence. Because the question about current smoking status was asked before the parent gave informed consent, we do not believe that consent to participate had any implication for the prevalence data on current smoking status. We did not observe a difference in the consent rate during the period 2 years after intervention implementation.

Intervention practices received regular data monitoring and feedback from the study staff, and it is unknown if meaningful treatment delivery would be sustained without this support. To faithfully replicate the intervention protocol, accountable care organizations may have to undertake the task of monitoring each practice’s parental tobacco-use screening and assistance data, to sustain the intervention and reduce population-level tobacco use rates.37 Providing program management support for the intervention may help ensure a substantial return on investment.38

Smoking prevalence at 2 weeks after the intervention implementation was slightly higher in the intervention group. However, the characteristics of those who were currently smoking, between intervention and control practices at 2 weeks after implementation indicates that randomization generally resulted in good balance between the 2 groups.

Conclusions

Using an innovative electronic screening system to address household tobacco use, the CEASE intervention produced markedly higher rates of screening parents for tobacco use and delivering effective tobacco-cessation assistance compared with usual care, and these effects were sustained 2 years after the intervention implementation. A decrease in parent smoking prevalence and increase in cotinine-confirmed cessation was measured in practices that implemented the CEASE intervention, while changes occurred in the opposite direction in the usual-care practices. If implemented in pediatric practices nationally, this intervention could reduce the prevalence of tobacco use among US parents and protect children from exposure to tobacco smoke.

Trial Protocol.

Data Sharing Statement.

References

- 1.Farber HJ, Groner J, Walley S, Nelson K; Section on Tobacco Control . Protecting children from tobacco, nicotine, and tobacco smoke. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1439-e1467. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services The health consequences of smoking: 50 years of progress, a report of the Surgeon General. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK179276/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK179276.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed July 8, 2019.

- 3.Hall N, Hipple B, Friebely J, Ossip DJ, Winickoff JP. Addressing family smoking in child health care settings. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2009;16(8):367-373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Department of Health and Human Services The health consequences of involuntary tobacco smoke: a report of the Surgeon General. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44324/. Published 2006. Accessed July 8, 2019.

- 5.Mackay D, Haw S, Ayres JG, Fischbacher C, Pell JP. Smoke-free legislation and hospitalizations for childhood asthma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(12):1139-1145. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.den Exter Blokland EA, Engels RC, Hale WW III, Meeus W, Willemsen MC. Lifetime parental smoking history and cessation and early adolescent smoking behavior. Prev Med. 2004;38(3):359-368. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farkas AJ, Distefan JM, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Pierce JP. Does parental smoking cessation discourage adolescent smoking? Prev Med. 1999;28(3):213-218. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bricker JB, Leroux BG, Peterson AV Jr, et al. Nine-year prospective relationship between parental smoking cessation and children’s daily smoking. Addiction. 2003;98(5):585-593. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bricker JB, Leroux BG, Robyn Andersen M, Rajan KB, Peterson AVJ Jr. Parental smoking cessation and children’s smoking: mediation by antismoking actions. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(4):501-509. doi: 10.1080/14622200500186353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bricker JB, Peterson AVJ Jr, Sarason IG, Andersen MR, Rajan KB. Changes in the influence of parents’ and close friends’ smoking on adolescent smoking transitions. Addict Behav. 2007;32(4):740-757. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winickoff JP, Healey EA, Regan S, et al. Using the postpartum hospital stay to address mothers’ and fathers’ smoking: the NEWS study. Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):518-525. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008. update, clinical practice guideline. https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/patient_care/clinical_recommendations/TreatingTobaccoUseandDependence-2008Update.pdf. Published May 2008. Accessed July 8, 2019.

- 13.Winickoff JP, Nabi-Burza E, Chang Y, et al. Implementation of a parental tobacco control intervention in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):109-117. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winickoff JP, Nabi-Burza E, Chang Y, et al. Sustainability of a parental tobacco control intervention in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):933-941. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winickoff JP, Park ER, Hipple BJ, et al. Clinical effort against secondhand smoke exposure: development of framework and intervention. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):e363-e375. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winickoff JP, Hipple B, Drehmer J, et al. The Clinical Effort Against Secondhand Smoke Exposure (CEASE) intervention: a decade of lessons learned. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2012;19(9):414-419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walters BH, Ossip DJ, Drehmer JE, et al. Clinician telephone training to reduce family tobacco use: analysis of transcribed recordings. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2016;23(2):79-86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smokefree.gov SmokefreeTXT. https://smokefree.gov/smokefreetxt. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- 20.Office of the Legislative Counsel Compilation of Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ppacacon.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- 21.Green ME, Hogg W, Savage C, et al. Assessing methods for measurement of clinical outcomes and quality of care in primary care practices. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:214. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moody-Thomas S, Celestin MD Jr, Tseng TS, Horswell R. Patient tobacco use, quit attempts, and perceptions of healthcare provider practices in a safety-net healthcare system. Ochsner J. 2013;13(3):367-374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pbert L, Adams A, Quirk M, Hebert JR, Ockene JK, Luippold RS. The patient exit interview as an assessment of physician-delivered smoking intervention: a validation study. Health Psychol. 1999;18(2):183-188. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.18.2.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hrisos S, Eccles MP, Francis JJ, et al. Are there valid proxy measures of clinical behaviour? a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2009;4:37. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winickoff JP, Hillis VJ, Palfrey JS, Perrin JM, Rigotti NA. A smoking cessation intervention for parents of children who are hospitalized for respiratory illness: the Stop Tobacco outreach program. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):140-145. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winickoff JP, Buckley VJ, Palfrey JS, Perrin JM, Rigotti NA. Intervention with parental smokers in an outpatient pediatric clinic using counseling and nicotine replacement. Pediatrics. 2003;112(5):1127-1133. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinson BC, Murray DM, Jeffery RW, Hennrikus DJ. Intraclass correlation for measures from a worksite health promotion study: estimates, correlates, and applications. Am J Health Promot. 1999;13(6):347-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51(3):390-395. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.51.3.390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12(1):38-48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McBride CM, Emmons KM, Lipkus IM. Understanding the potential of teachable moments: the case of smoking cessation. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(2):156-170. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jenssen BP, Bryant-Stephens T, Leone FT, Grundmeier RW, Fiks AG. Clinical decision support tool for parental tobacco treatment in primary care. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5):e20154185. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winickoff JP, Tanski SE, McMillen RC, Hipple BJ, Friebely J, Healey EA. A national survey of the acceptability of quitlines to help parents quit smoking. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):e695-e700. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nabi-Burza E, Winickoff JP, Drehmer J, et al. Innovations in parental smoking cessation assistance delivered in the child healthcare setting. Accept Transl Behav Med. 2019;pii:ibz070. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibz070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahabee-Gittens EM, Dixon CA, Vaughn LM, Duma EM, Gordon JS. Parental tobacco screening and counseling in the pediatric emergency department: practitioners’ attitudes, perceived barriers, and suggestions for implementation and maintenance. J Emerg Nurs. 2014;40(4):336-345. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2013.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jamal A, King BA, Neff LJ, Whitmill J, Babb SD, Graffunder CM. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(44):1205-1211. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6544a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang TW, Asman K, Gentzke AS, et al. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(44):1225-1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fisher ES, McClellan MB, Bertko J, et al. Fostering accountable health care: moving forward in Medicare, Vol. 28. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(2):219-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dilley JA, Harris JR, Boysun MJ, Reid TR. Program, policy, and price interventions for tobacco control: quantifying the return on investment of a state tobacco control program. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(2):e22-e28. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol.

Data Sharing Statement.