Abstract

Background

People with low back pain (LBP) may display an altered lumbar movement pattern of early lumbar motion compared to people with healthy backs. Modifying this movement pattern during a clinical test decreases pain. It is unknown whether similar effects would be seen during a functional activity.

Objective

The objective of this study was to examine the lumbar movement patterns before and after motor skill training, effects on pain, and characteristics that influenced the ability to modify movement patterns.

Design

The design consisted of a repeated-measures study examining early-phase lumbar excursion in people with LBP during a functional activity test.

Methods

Twenty-six people with chronic LBP received motor skill training, and 16 people with healthy backs were recruited as a reference standard. Twenty minutes of motor skill training to decrease early-phase lumbar excursion during the performance of a functional activity were used as a treatment intervention. Early-phase lumbar excursion was measured before and after training. Participants verbally reported increased pain, decreased pain, or no change in pain during performance of the functional activity test movement in relation to their baseline pain. The characteristics of people with LBP that influenced the ability to decrease early-phase lumbar excursion were examined.

Results

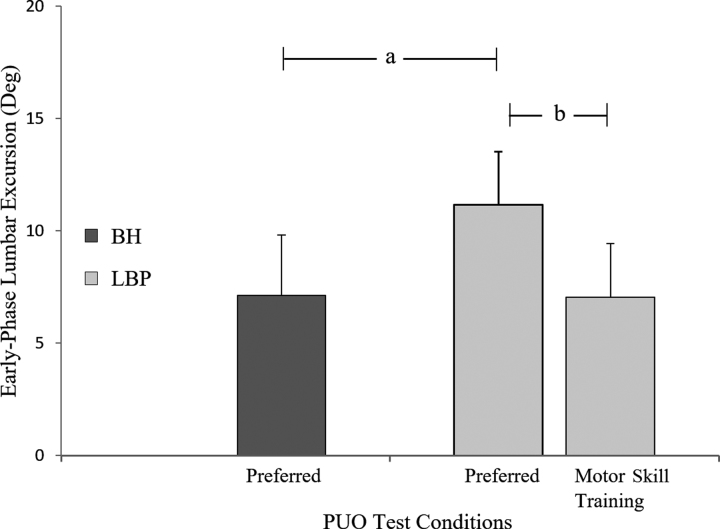

People with LBP displayed greater early-phase lumbar excursion before training than people with healthy backs (LBP: mean = 11.2°, 95% CI = 9.3°–13.1°; healthy backs: mean = 7.1°, 95% CI = 5.8°–8.4°). Following training, the LBP group showed a decrease in the amount of early-phase lumbar excursion (mean change = 4.1°, 95% CI = 2.4°–5.8°); 91% of people with LBP reported that their pain decreased from baseline following training. The longer the duration of LBP (β = − 0.22) and the more early-phase lumbar excursion before training (β = − 0.82), the greater the change in early-phase lumbar excursion following training.

Limitations

The long-term implications of modifying the movement pattern and whether the decrease in pain attained was clinically significant are unknown.

Conclusions

People with LBP were able to modify their lumbar movement pattern and decrease their pain with the movement pattern within a single session of motor skill training.

Low back pain (LBP) is the leading cause of non-fatal disability worldwide,1–3 often resulting in persistent pain and limitations in the performance of daily functional activities.4,5 The primary reason people with LBP seek initial and repeat medical care for a LBP condition is limitations in the performance of functional activities.6,7 Although exercise has been shown to be an effective approach for the treatment of chronic LBP, no specific form of exercise has been shown to be most effective for improving LBP-related functional limitations.8–11 One possible explanation may be that the exercise-based treatments have not focused on identifying and modifying symptom-provoking movement patterns used repeatedly throughout the day with performance of functional activities.

During clinical tests of movement, an altered movement pattern frequently identified in people with LBP has been one in which the lumbar spine moves more readily into its available range of motion compared to other joints that contribute to the overall movement (eg, hip or thoracic spine).12–15 Theoretical models such as the kinesiopathologic model12 provide a conceptual framework to understand how an altered movement pattern of early lumbar motion may contribute to the development and course of LBP.16–18 A primary assumption of the kinesiopathologic model is that people adopt an altered lumbar movement pattern that is repeated throughout the performance of functional activities across the day. Because most functional activities are performed in the early to middle ranges of lumbar motion,19–21 it is proposed that the repeated use of the altered lumbar movement pattern may lead to an accumulation of lumbar tissue stress, micro- or macrolevel tissue injury, and eventually pain.22–25 Recent data suggest that people with LBP and high levels of functional limitation consistently display a pattern of early lumbar motion during functional activity tests.26 Additional research suggests that the pattern of early lumbar motion is associated with a persons’ LBP symptoms16,17,27,28 and functional limitations.26,29 Therefore, treatment directed at decreasing the amount of early lumbar motion during a functional activity may be a logical and direct approach to improving symptoms and functional limitations in people with chronic LBP.

Prior research has demonstrated that people with LBP can reduce the amount of early lumbar motion during a single session of training through the use of verbal and tactile cues during the clinical test of hip lateral rotation.30 It also has been shown that people with LBP are able to modify their altered lumbar movement pattern following 6 weeks of training to reduce the amount of early lumbar motion during the hip lateral rotation test.18 Modifying the lumbar movement pattern during clinical tests has been shown to be an effective method to reduce LBP symptoms16,17 and functional limitations.31 Given the significance of limitations in functional activities for people with LBP, it would be important to examine the ability to modify the lumbar movement pattern during a functional activity, the effect of modifying the movement pattern on pain, and the characteristics of people that influence the ability to modify the pattern.

The primary purpose of the current study was to examine the ability of people with LBP to reduce the amount of early lumbar motion during a functional activity test within a single session of motor skill training. Motor skill training is a form of training that involves practice of a skill to promote the acquisition and refinement of novel combinations of motor sequences through challenging practice. Studies in humans suggest that motor skill training produces neural changes that are associated with the acquisition of a new motor skill.32–36 Because limitation in functional activities is the primary reason people with LBP seek initial and repeat medical care,6,7 motor skill training during a functional activity represents a direct approach to address the performance of the activity. A key component of the motor skill training in this study was that the training emphasized intrinsic feedback to facilitate learning37–39 during challenging practice of a functional activity that is often painful and limited40 for people with LBP (eAppendix, available at https://academic.oup.com/ptj). We hypothesized that, following motor skill training, people with LBP would demonstrate decreased early lumbar motion during performance of the functional activity test.

A second purpose was to examine the effect of modifying the lumbar movement pattern on pain. We hypothesized that decreasing the amount of early lumbar motion would result in a decrease in pain during performance of the functional activity test. The final purpose of the study was to conduct an exploratory analysis of the characteristics of people with LBP that were associated with the ability to minimize the early lumbar motion when performing the functional activity. Although this was an exploratory analysis, we hypothesized that certain demographic variables, hamstring extensibility, lumbar lordosis angle, LBP, and movement characteristics would be associated with the change in early lumbar motion following training. Specifically, we hypothesized that participants who were younger and less impaired (ie, greater hamstring extensibility, shorter duration of LBP history, and lower levels of pain, functional limitation, and fear avoidance behaviors) would demonstrate greater change in early lumbar motion. Improved understanding of the characteristics that may influence the ability of a person to modify an altered movement pattern may be important to assist in prognosis as well as the clinical decision making process for the delivery of this type of intervention.

Methods

Twenty-six people with chronic LBP41 were recruited through advertisements in the St Louis metropolitan area. Chronic LBP was operationally defined as LBP present on greater than half of the days in a 12-month period.41 Participants with LBP were excluded if they were in an acute flare up41 or reported a history of various structural or systemic reasons for LBP, or psychosocial factors known to negatively affect outcomes.42 In order to provide a reference for examining the amount of early lumbar motion during the untrained or preferred movement, an additional 16 people who were matched for sex, age, height, weight, and body mass index and who had healthy backs also were recruited. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1. All participants signed a written informed consent form approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Human Research Protection Office.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Participants With Low Back Pain (LBP) and Participants With Healthy Backs.

| Criterion | Participants | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion | All | Age of 18–60 y |

| Body mass index of < 30 kg/m2 | ||

| Those with LBP | History of LBPa | |

| LBP condition for a duration of at least 12 mo | ||

| LBP symptoms present on more than half the days of the year | ||

| Exclusion | Those with healthy backs | History of LBPa |

| All | Spinal complications (ie, tumor or infection) | |

| Previous spinal surgery (lumbar) | ||

| Neurological disease requiring hospitalization | ||

| Diagnosis of any of the following spinal conditions: | ||

| Marked kyphosis/scoliosis | ||

| Spinal stenosis | ||

| Spondylolisthesis | ||

| Spinal instability | ||

| Spinal fracture or dislocations | ||

| Osteoporosis | ||

| Ankylosing spondylitis | ||

| Disk herniation with current radicular symptoms | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | ||

| Currently pregnant | ||

| Undergoing treatment for kidney or bladder infection | ||

| Loss of sensation, weakness, or numbness in arms or legs | ||

| Pain, numbness, or tingling below the knee | ||

| Difficulty standing or walking without assistance | ||

| Undergoing treatment for cancer | ||

| Receiving disability benefits or worker's compensation for LBP | ||

| Involved in litigation for LBP |

aA history of LBP was defined as LBP symptoms that resulted in seeking a medical/health care intervention (eg, physician, chiropractor, or physical therapist) or altered performance of work, school, daily functional, or physical activity for 3 or more consecutive days.

Self-Report Measures

Following consent, all participants completed a survey of demographic information and the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey.43 Participants with LBP also completed 4 self-report surveys: an LBP history questionnaire, a numeric pain rating scale,44,45 the Modified Low Back Disability Questionnaire (MLBPDQ),46 and the Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire.47 All participants were assessed by an experienced physical therapist for hamstring extensibility using the Hamstring Length and Associated Lumbar Flexibility test (hamstring length).48

Laboratory Measures

An 8-camera, 3-dimensional motion capture system (Vicon Motion Systems, Ltd, Denver, Colorado) with a sampling rate of 120 Hz was used to capture kinematic data. Retroreflective markers were placed on predetermined landmarks of the lower extremities, pelvis, and trunk.26 Participants were instructed to stand in a comfortable position with feet placed pelvis-width apart. Participants performed 3 separate movement trials for 2 conditions of the Pick Up an Object (PUO) functional activity test; the average of the 3 trials was examined.26,30 For both PUO test conditions, a lightweight container measuring 20 by 30 by 12 cm was placed at a height equal to the participant's shank length and at a distance equal to half of the participant's trunk length.26 Participants received verbal instructions to pick up the object using both hands and return to the starting position. A maximum of 10 seconds was allowed to complete each movement trial, and participants were instructed to move at a self-selected speed. LBP was measured using a numeric pain rating scale to establish a participant's baseline pain intensity in standing. Participants were told that they would be asked to pay attention to their pain during the PUO tests. Following each movement trial, participants reported whether their pain increased, decreased, or remained the same during the forward flexion phase of movement compared to their baseline pain in standing.16,17 Participants who reported an increase in pain for any of the 3 movement trials were considered to have increased pain during the movement. Participants who reported a decrease in pain for any of the 3 movement trials were considered to have decreased pain during the movement. In this study, no participants reported an increase and a decrease in pain during any set of the 3 movement trials.

For the first PUO functional activity test condition, a participant was not provided any instruction regarding how to move before performing the test and, thus, the movement was considered the participant's preferred movement pattern (PUO-Preferred).

Upon completion of the PUO-Preferred movement trials, participants with LBP underwent a 20-minute session of motor skill training by a trained physical therapist (eAppendix). The goal of the skill training is to promote motor learning of a task through challenging practice. The focus for the PUO task was on decreasing the amount of early lumbar motion with performance of the functional activity. The training included demonstration, visual cues, tactile cues, and opportunity for practice providing both external feedback and encouraging the use of intrinsic feedback.49 A primary objective of the motor skill training was to promote the development and use of intrinsic feedback and problem solving on the part of the participant, so extrinsic feedback was removed as quickly as possible. Participants then performed 3 separate trials of the second PUO functional activity test condition (PUO-MST) and reported whether their symptoms increased, decreased, or remained the same during the movement compared to their symptoms while standing.

A fourth-order, dual-pass Butterworth filter with a cutoff frequency of 3 Hz was applied, and the kinematic data were processed using Visual 3D software (C-Motion, Inc, Germantown, Maryland), and MATLAB (MathWorks Inc, Natick, Massachusetts) custom written software. The lumbar lordosis angle in the initial standing position was calculated. The formula used was lordosis = 2arctan[0.5 × (length/depth)], where length is equal to the vertical distance from the L1 marker to the L5 marker and depth is equal to the perpendicular distance from the L3 marker to the length vector.50–52 A vector between the C7 marker and the T12 marker defined the thoracic segment. A vector between the T12 marker and the S1 marker defined the lumbar segment. Markers placed on the right and left posterior superior iliac spine, iliac crest, and anterior superior iliac spine and the distal sacrum defined the pelvis segment. Markers on the mid-thigh, greater trochanter, and the medial and lateral knee joint line defined the thigh segment.

Sagittal plane angular displacements of the thoracic, lumbar, pelvis, and thigh segments were calculated from the start of forward trunk flexion to the stop of forward trunk flexion for both test conditions. Excursion of the thoracic spine was calculated relative to the lumbar segment. Excursion of the lumbar spine was calculated relative to the pelvis segment. Excursion of the hip was calculated as angular displacement of the pelvis relative to the thigh segment. Trunk excursion was defined as the angular displacement of the combined thoracic, lumbar, and hip segments. The start of motion was defined as a 1-degree change in sagittal plane forward trunk flexion. The stop of motion was defined as 98% of the maximum forward trunk flexion. Total movement time for forward trunk flexion was calculated, and increments of movement time were determined for the first 50% (early phase) and the last 50% (late phase) of movement time. Early lumbar motion was indexed by calculating the amount of lumbar excursion in the early-phase of movement time. Intraclass correlation coefficients and the standard error of the measure were calculated for the 16 participants with healthy backs during the PUO-Preferred test for maximal, early-phase, and late-phase lumbar excursion. ICC(3,1) values ranged from 0.88 to 0.95, and the standard error of the measure values ranged from 0.8 to 1.2 degrees.

Dependent Variables

Lumbar and hip kinematics were examined for the PUO-Preferred and PUO-MST tests. Maximal as well as early- and late-phase excursion was calculated for the lumbar and hip segments. The primary variable of interest was early-phase lumbar excursion. Change in early-phase lumbar excursion for the LBP group was calculated by subtracting the early-phase lumbar excursion during the PUO-MST test from the PUO-Preferred test.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics Inc, Chicago, Illinois), with a 2-tailed significance level set at a P value of ≤ .05 and a power of 0.80. The sample size of 26 LBP participants was calculated based on data from a previous study that reported a 2.8-degree within-session change in lumbar excursion during a clinical test.30

Participant characteristics

Differences between participants with LBP and participants with healthy backs in sex distribution, age, height, weight, body mass index, lumbar lordosis angle, and hamstring extensibility were examined using a chi-square test or an independent-group t test.

Movement excursion

Independent-group t tests were conducted to examine differences between participants with healthy backs and participants with LBP for lumbar lordosis angle in standing, as well as for movement time for forward trunk flexion, maximal lumbar and hip excursion, and early-phase lumbar excursion during the PUO-Preferred test. Next, a paired-sample t test was conducted to examine the change in early-phase lumbar excursion between the PUO-Preferred and the PUO-MST conditions for the LBP group. Finally, an independent-group t test was used to examine differences in the early-phase lumbar excursion between participants with healthy backs (PUO-Preferred) and participants with LBP following the skill training (PUO-MST). Cohen d effect sizes were calculated following each t test.53 A Bonferroni correction was applied to account for the multiple comparisons (n = 3) of the early-phase lumbar excursion variable; an α value of ≤ .017 was required for significance.

Pain with movement

A McNemar test was conducted to test for differences in the proportion of participants who reported an increase in LBP during the PUO-Preferred and the PUO-MST tests. Independent-group t tests were conducted on baseline participant characteristics between participants who reported an increase in pain during the PUO-Preferred test, and those who reported a decrease or no change in pain during the PUO-Preferred test.

Factors associated with change in early-phase lumbar excursion

For people with LBP, a linear regression analysis was conducted to predict the dependent variable, change in early-phase lumbar excursion. Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were calculated between the dependent variable and the predictor variables. The predictor variables included the participant characteristics listed in Table 2 and early-phase lumbar excursion during the PUO-Preferred test. Finally, to assist in the choice of the final predictor variables to be included in the regression analysis, bivariate correlations also were calculated among the predictor variables that were correlated significantly with the criterion variable (P < .05).

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants with Healthy Backs and Participants With Low Back Pain (LBP).

| Characteristic | Participants With Healthy Backs (n = 16)a | Participants With LBP (n = 26)a | Statistical Value | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||||

| Women, no. (%) | 10 (63) | 15 (58) | χ2 = 1.17 | .76 |

| Age, y | 37.4 (11.0) | 38.5 (12.3) | t = 0.27 | .79 |

| Height, m | 1.70 (0.13) | 1.72 (0.10) | t = 0.65 | .52 |

| Weight, kg | 68.6 (14.6) | 71.9 (11.6) | t = 0.80 | .43 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.6 (2.4) | 24.0 (2.6) | t = 0.54 | .59 |

| Extensibility and alignment | ||||

| Hamstring length testing,b ϒ | 166.4 (7.6) | 167.3 (8.2) | t = 0.36 | .72 |

| Lumbar lordosis angle,c ϒ | 161.2 (7.7) | 158.9 (6.8) | t = 0.86 | .33 |

| LBP | ||||

| mODd score, % | 24.2 (12.8) | |||

| LBP duration, y | 13.7 (7.5) | |||

| FABQ-We score | 12.5 (5.6) | |||

| FABQ-PAe score | 9.3 (8.6) | |||

| Pain intensityf | ||||

| Current | 3.0 (1.0) | |||

| Average (preceding 7 d) | 3.4 (0.8) | |||

| Worst (preceding 7 d) | 5.4 (1.2) | |||

| SF-36 PCSg score | 84.7 (14.5) | 80.6 (13.9) | t = 0.92 | .37 |

| SF-36 MCSg score | 78.8 (14.9) | 72.8 (16.0) | t = 1.21 | .23 |

aDescriptive statistics are presented as mean (SD), unless otherwise noted.

bTesting of hamstring length and associated lumbar flexibility was conducted in the supine position with the tested leg placed in 90° of hip flexion, the inclinometer aligned with the long axis of the fibula, and the nontested leg placed in a position of hip and knee flexion with the foot flat on the table.

cCalculated as 2arctan(0.5l/d), where l is the vertical distance from the L1 marker to L5 marker and d is the distance perpendicular from a vector from L3 to l.

dMLBDQ = Modified Low Back Disability Questionnaire; scores range from 0% to 100%.

eFABQ = Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire; scores range from 0 to 42 for the work (W) subscale and from 0 to 24 for the physical activity (PA) subscale.

fMeasured with a numeric pain rating scale; scores range from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable).

gSF-36 = 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey; scores range from 0 to 100 for the physical health component (PCS) and the mental health component (MCS) subscales.

Role of the Funding Source

This work was partially funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research (grant no. R01 HD047709), a Foundation for Physical Therapy Promotion of Doctoral Studies Scholarship, and the Dr Hans and Clara Davis Zimmerman Foundation. The funders played no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study.

Results

Participant Characteristics

There were no differences between participants with LBP and participants with healthy backs in sex distribution, age, height, weight, or body mass index. There were no differences between participants with LBP and participants with healthy backs in initial lumbar lordosis angle in standing or hamstring extensibility (P > .05) (Tab. 2).

Movement Excursion

Mean total movement time, maximal and early-phase lumbar excursion, and maximal hip excursion for the 2 PUO conditions are presented in Table 3. There were no differences between participants with LBP and participants with healthy backs for total movement time (t = 0.46, P = .64) or for maximal lumbar (t = 0.09, P = .93) or hip excursion (t = 0.63, P = .53) during the PUO-Preferred test. The Figure displays the values for early-phase lumbar excursion for the PUO-Preferred test for participants with LBP and participants with healthy backs and the PUO-MST test for participants with LBP. In the PUO-Preferred condition, participants with LBP displayed significantly greater early-phase lumbar excursion than participants with healthy backs (LBP: mean = 11.2°, 95% CI = 9.3°–13.1°; healthy backs: mean = 7.1°, 95% CI = 5.8°–8.4°; t = − 2.95, P < .005, d = 1.02). Following skill training, participants with LBP demonstrated a significant decrease in early-phase lumbar excursion compared to their movement in the PUO-Preferred condition (mean change = 4.1°, 95% CI = 2.4°–5.8°; t = 4.73, P < .01, d = 1.05). Following training, the early-phase lumbar excursion of participants with LBP group was not different from the early-phase lumbar excursion of participants with healthy backs in the PUO-Preferred condition (mean difference = 0.1°, 95% CI = − 0.1°to 0.3°, t = 0.11, P = .91, d = 0.03).

Table 3.

Results of Pick Up an Object (PUO) Test for Participants With Low Back Pain (LBP) and Participants With Healthy Backs.a

| Parameter | PUO-Preferred | PUO-MST | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants With Healthy Backsb | Participants With LBPb | t Statistic | P | Participants With LBPb | t Statistic | P | |

| Movement time, s | 1.19 (0.24) | 1.23 (0.30) | 0.46 | .64 | 1.47 (0.38) | 1.14 | .26 |

| Lumbar excursion, ϒ | |||||||

| Maximal | 18.6 (7.7) | 18.5 (5.8) | 0.09 | .93 | 16.2 (6.2) | 1.16 | .25 |

| Early-phase | 7.1 (2.7) | 11.2 (5.0) | 2.95 | .005 | 7.1 (2.4) | 0.11 | .91 |

| Hip excursion, ϒ | |||||||

| Maximal | 52.2 (11.0) | 49.7 (13.3) | 0.63 | .53 | 57.0 (15.4) | 1.10 | .28 |

aFor PUO-Preferred, a participant was not provided any instruction regarding how to move before performing the PUO test and, thus, the movement was considered the participant's preferred movement pattern; for PUO-MST, a participant with LBP received motor skill training from a trained physical therapist before performing the PUO test.

bValues are reported as mean (SD).

Figure.

Change in early-phase lumbar excursion following motor skill training (MST). Data are means and SDs for early-phase lumbar excursion in participants with healthy backs during the Pick Up an Object (PUO) test for the preferred condition (in which participants were not provided any instruction regarding how to move and, thus, the movement was considered the participant's preferred movement pattern) and in participants with low back pain (LBP) during the Pick Up an Object test for the preferred and MST conditions. There was no difference between the preferred condition for participants with healthy backs (BH) and the MST condition for participants with LBP (LBP). Significant effects are indicated by letters: a, significant difference between participants with healthy backs and participants with LBP for the preferred condition; b, significant change in early-phase lumbar excursion between preferred and MST conditions for the LBP group.

Pain with Movement

Forty-two percent (11/26) of LBP participants reported an increase in pain compared with baseline pain in standing during the PUO-Preferred test. Following skill training, 91% (10/11) of these participants no longer reported an increase in pain during the PUO-MST test (P < .01). There were no differences in age, height, weight, body mass index, lumbar lordosis angle, hamstring extensibility, MLBPDQ, or pain intensity between the participants with increased pain and the participants with decreased or no change in pain during the PUO-Preferred test (Tab. 4). However, the participants who reported increased pain during the PUO-Preferred test had significantly higher Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire work subscale (t = 2.70, P = .01) and physical activity subscale (t = 3.03, P < .01) scores.

Table 4.

Changes in Symptoms in Participants With Low Back Pain (LBP) During the PUO-Preferred Test.a

| Characteristic | Participants With Increase in Symptoms (n = 11)b | Participants With Decrease or No Change in Symptoms (n = 15)b | Statistical Value | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Women, no. (%) | 5 (45) | 10 (67) | χ2 = 1.17 | .25 |

| Age, y | 37.1 (12.2) | 39.5 (12.8) | t = 0.48 | .64 |

| Height, m | 1.73 (0.10) | 1.73 (0.10) | t = 0.02 | .98 |

| Weight, kg | 71.3 (7.4) | 72.4 (14.2) | t = 0.24 | .82 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.9 (1.8) | 24.1 (3.1) | t = 0.20 | .84 |

| Extensibility and alignment | ||||

| Hamstring length test,c ϒ | 164.0 (9.7) | 169.7 (6.2) | t = 1.80 | .08 |

| Lumbar lordosis angle,d ϒ | 159.4 (4.7) | 161.4 (4.9) | t = 0.61 | .54 |

| LBP | ||||

| MLBPDQe, % | 29.5 (10.4) | 20.4 (13.4) | t = 1.86 | .08 |

| LBP duration, y | 13.9 (6.8) | 13.6 (8.2) | t = 0.10 | .92 |

| FABQ-Wf | 15.5 (6.4) | 10.2 (3.6) | t = 2.70 | .01g |

| FABQ-PAf | 14.5 (8.1) | 5.5 (6.9) | t = 3.03 | <.01g |

| Pain intensityh | ||||

| Current | 3.3 (1.0) | 2.9 (1.0) | t = 1.03 | .32 |

| Average (preceding 7 d) | 3.5 (0.7) | 3.3 (0.8) | t = 0.93 | .36 |

| Worst (preceding 7 d) | 5.7 (1.4) | 5.1 (1.0) | t = 1.26 | .22 |

| SF-36 PCSi | 78.6 (15.8) | 82.0 (12.6) | t = 0.60 | .55 |

| SF-36 MCSi | 65.8 (18.6) | 77.9 (11.9) | t = 2.02 | .06 |

| Movement | ||||

| Maximal lumbar excursion, ϒ | 19.8 (4.6) | 17.5 (6.5) | t = 0.99 | .33 |

| Early-phase lumbar excursion, ϒ | 13.2 (3.2) | 9.6 (5.6) | t = 1.89 | .07 |

| Maximal hip excursion, ϒ | 46.4 (9.8) | 52.1 (15.3) | t = 1.08 | .29 |

aFor PUO-Preferred, a participant was not provided any instruction regarding how to move before performing the Pick Up an Object (PUO) test, and, thus, the movement was considered the participant's preferred movement pattern.

bDescriptive statistics are presented as mean (SD), unless otherwise noted.

cTesting of hamstring length and associated lumbar flexibility was conducted in the supine position with the tested leg placed in 90° of hip flexion, the inclinometer aligned with the long axis of the fibula, and the nontested leg placed in a position of hip and knee flexion with the foot flat on the table.

dCalculated as 2arctan(0.5l/d), where l is the vertical distance from the L1 marker to the L5 marker and d is the distance perpendicular from a vector from L3 to l.

eMLBPDQ = Modified Low Back Disability Questionnaire; scores range from 0% to 100%.

fFABQ = Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire; scores range from 0 to 42 for the work (W) subscale and from 0 to 24 for the physical activity (PA) subscale.

gSignificant value (P < .05).

hMeasured with a numeric pain rating scale; scores range from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable).

iSF-36 = 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey; scores range from 0 to 100 for the physical health component (PCS) and the mental health component (MCS) subscales.

Variables Associated With Change in Early-Phase Lumbar Excursion

The 4 predictor variables that were correlated significantly with the dependent variable, change in early-phase lumbar excursion, included hamstring length (r = − 0.52, r2 = 0.27, P < .01), MLBPDQ score (r = 0.57, r2 = 0.33, P < .01), duration of LBP symptoms (r = 0.39, r2 = 0.16, P = .05), and PUO-Preferred early-phase lumbar excursion (r = 0.88, r2 = 0.78, P < .01) (eTable, available at https://academic.oup.com/ptj). These results indicate that a greater change in early-phase lumbar excursion following training is associated with decreased hamstring extensibility, increased MLBPDQ scores, longer duration of LBP symptoms, and greater early-phase lumbar excursion in the PUO-Preferred condition. Intercorrelations among the predictor variables that were significantly correlated with the dependent variable are presented in the eTable (available at https://academic.oup.com/ptj).

With a sample size of 26 participants, 3 variables could be entered into the regression analysis. Because the PUO-Preferred early-phase lumbar excursion was significantly correlated with both MLBPDQ and hamstring length, a decision was made to exclude MLBPDQ from the regression analysis. This decision was based on prior research that indicated that MLBPDQ scores were consistently positively associated with the amount of early-phase lumbar excursion in a PUO-Preferred condition.26,29 Thus, MLBPDQ scores were redundant with the amount of early phase lumber excursion in the PUO-Preferred condition. Therefore, in the regression analysis, we included the following 3 predictor variables: hamstring length, duration of LBP symptoms, and PUO-Preferred early-phase lumbar excursion. The 3-variable model accounted for 82.1% of the variance in the change in early-phase lumbar excursion (F(3,22) = 33.70, P < .01) (Tab. 5). Duration of LBP symptoms (β = − 0.22, P = .03) and PUO-Preferred early-phase lumbar excursion (β = − 0.82, P < .01) were the only significant predictors in the regression model. These results indicate that the longer the duration of LBP and the more early-phase lumbar excursion displayed during the PUO-Preferred test, the greater the change in early-phase lumbar excursion participants displayed following training.

Table 5.

Results of Standard Multiple Regression Analysis of Predictors of Change in Early-Phase Lumbar Excursion for Participants With Low Back Pain (LBP).

| Predictor Variable | Criterion Variable (Change in Early-Phase Lumbar Excursion) | |

|---|---|---|

| R 2 | P | |

| PUO-Preferred early-phase lumbar excursiona | 0.78 | <.01 |

| Duration of LBP symptoms | 0.05 | .03 |

| Hamstring length testb | 0.00 | .86 |

| Total R2 | 0.82 | <.01 |

aAmount of early-phase lumbar excursion (ϒ) during a Pick Up an Object (PUO) test in which a participant was not provided any instruction regarding how to move before performing the test; thus, the movement was considered the participant's preferred movement pattern.

bTesting of hamstring length and associated lumbar flexibility was conducted in the supine position with the tested leg placed in 90° of hip flexion, the inclinometer aligned with the long axis of the fibula, and the nontested leg placed in a position of hip and knee flexion with the foot flat on the table.

Discussion

The first purpose of this study was to examine if people with LBP could modify their preferred lumbar movement pattern during a functional activity test. We found that following training, participants with LBP were able to reduce the amount of early-phase lumbar excursion and displayed a pattern of lumbar excursion similar to the pattern displayed by participants with healthy backs. The second purpose of this study was to examine the effect of motor skill training on LBP reported during a functional activity. Consistent with our hypothesis, 91% of participants with increased LBP during the preferred movement reported decreased LBP following training. Therefore, modifying the lumbar movement pattern was an effective approach to improving LBP. The final purpose of the study was to explore which characteristics of people with LBP were associated with the ability to modify their preferred pattern of lumbar excursion during the functional activity test. We found that the longer the person had LBP, and the more early-phase lumbar excursion a person displayed during the preferred movement condition, the more a person could change his lumbar movement pattern after motor skill training.

Prior work has shown that people with LBP with high levels of functional limitation consistently display early lumbar motion when the conditions of a functional activity test are varied, suggesting that people with LBP adopt altered movement patterns that are used across activities throughout the day.26 In the current study, we found that although people with healthy backs and people with LBP displayed similar amounts of maximal lumbar and hip excursion with performance of a functional activity test, people with LBP displayed an altered movement pattern of early lumbar motion compared to people with healthy backs during the preferred movement condition. In addition, we found that immediately after a 20-minute session of skill training, people with LBP were able to modify their preferred movement pattern by reducing the amount of early-phase lumbar excursion during the same functional activity test. Although the change in the amount of early-phase lumbar excursion exceeded the standard error of the measure (0.8°–1.2°), it is unknown whether the change in early-phase lumbar excursion is clinically meaningful. Following training, however, there were no differences in the amount of early-phase lumbar excursion with the functional activity test between participants with LBP and participants with healthy backs. Thus, the LBP group was performing the functional activity in a manner that was similar to people who do not have LBP. Additionally, 91% of people no longer reported increased pain with movement following the training, suggesting that modifying the altered lumbar movement pattern was directly relevant to their current pain.

Two previous studies have documented that following a single session and 6 weeks of training, people with LBP were able to modify their preferred lumbar movement pattern during a clinical test by reducing the amount of early lumbar motion.18,30 Different from the prior studies, we were interested in whether people with LBP could modify their preferred lumbar movement pattern during a functional activity test. Because limitations in the performance of daily functional activities is a primary reason people with LBP seek medical care,6,7 we chose to use the PUO functional activity test.26 Although certain procedures of the PUO test were standardized, the test mimics a typical functional activity performed in a range of lumbar motion consistent with the demands of most functional activities,20,21 which are often problematic for people with LBP.40 Our findings are important because we have shown that people with LBP can modify an altered movement pattern known to be associated with a person's LBP-related functional limitation26 in a very short period of time. An important next step would be to examine the immediate and long-term effects of motor skill training using more robust methodology (ie, a randomized controlled trial) that can address some of the limitations of the repeated-measures design. Future research should examine whether motor skill training during functional activities results in better outcomes than other forms of physical therapy treatment, such as strength and flexibility exercise.

Prior studies have documented that, during clinical tests, people with LBP display an altered movement pattern of early lumbar motion13–15 and report an immediate improvement in pain when the altered movement pattern is corrected by manually reducing early lumbar motion.16,17 Similar to prior research, we also found that reducing early lumbar motion improved pain. However, different from the previous studies, we observed that people with LBP displayed early lumbar motion during a functional activity and were able to modify the movement pattern on their own without manual stabilization of the lumbar spine or verbal cueing by the clinician, and they reported an immediate improvement in pain during the movement. Although much remains unknown regarding the long-term effects of motor skill training, our results suggest that treatment interventions that include skill training specifically directed at performance of functional activities may be a viable option for clinicians to immediately modify an altered movement pattern associated with the person's pain. Because the current study suggests that people with LBP can modify the altered movement pattern within the context of the activity, clinicians may wish to direct skill training during functional activities that are difficult to perform because of the person's LBP.

Because not all people with LBP respond similarly to a given treatment, we wanted to know which participant characteristics predicted the ability to modify the altered lumbar movement pattern. When we looked at simple correlations, we found that the ability to reduce early-phase lumbar excursion was significantly associated with decreased hamstring extensibility, higher scores on the MLBPDQ, longer duration of LBP symptoms, and greater early-phase lumbar excursion during the preferred condition. Thus, counter to our hypothesis, the more impaired participants were the ones who were able to change their lumbar movement pattern more. In the regression analysis, only duration of LBP symptoms and early-phase lumbar excursion during the preferred condition were significant individual predictors of the change in early-phase lumbar excursion. It may seem logical that the participants with the most early-phase lumbar excursion changed the most following treatment because these participants had the greatest potential to change. However, our results are somewhat counterintuitive because the altered movement pattern was positively associated with functional limitation (r = 0.65, r2 = 0.42, P < .01), and one might assume that the more impaired the movement during that activity or the longer a person has had LBP, the more difficulty the person would have modifying the movement pattern. Our results, however, are encouraging because they provide preliminary evidence to suggest that even people that are more impaired are still able to modify their lumbar movement pattern within a short amount of time.

Study Limitations

Although the results of our study are encouraging, we recognize that there are limitations. One potential limitation is that the setup and verbal instructions for the PUO test were standardized and may not reflect the actual circumstances encountered during the performance of daily activities. First, the placement of the object used in the PUO test was scaled to the person rather than set to a constant position. The rationale for scaling the placement of the object to the individual was to decrease the likelihood of differences in movement time and total excursion due to variations in participant height. The standardized methods are consistent with prior research that has attempted to examine movement during a functional activity.54–58 Additionally, the participants were instructed not to move their feet, and to retrieve the object using both hands. Although the standardizations may not represent the exact manner in which a person would perform this activity outside of a laboratory setting, they provide an avenue to examine the lumbar movement pattern and changes in the pattern with training.

A second potential limitation is that participants were asked to monitor their pain during the PUO-preferred condition and this may have affected how they responded to monitoring pain during the PUO-MST condition following the training. Although we cannot eliminate this potential bias, the motor skill training involved repeated performance of the activity. Given this, one might expect pain to have increased during the posttest condition rather than decreased. Additionally, the participants were not told to expect an improvement in pain following the training.

A third limitation of the study is that the follow-up time for the repeated-measures design was not adequate to measure any lasting effects or transfer of effects of the motor skill training. Because the primary variable of interest, change in early-phase lumbar excursion, was examined on the same day following only 1 session of training, it is not known whether the modified movement pattern would be retained beyond the initial laboratory session or transferred to performance of other unrelated functional activities. Additionally, although we observed an immediate improvement in pain during performance of the movement following training, it is unknown whether modifying the movement pattern would affect pain on subsequent days. Thus, we do not know whether the improvement in pain represents a clinically meaningful change from baseline. We did not collect pain behavior with a numeric pain rating scale; therefore, we can comment only on the direction of change in pain and not the magnitude of the change. Finally, we also do not know whether our results would be generalizable because the sample of people with LBP in the present study was minimally to moderately involved.46 Future studies should examine the retention and transference of modifying an altered movement pattern with motor skill training, and quantify the short- and long-term effects on outcomes such as pain and functional limitation. Future work also should examine if the effects obtained in the current study are replicated in a sample of people with LBP and higher levels of pain and limitation.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that people with LBP can modify their preferred lumbar movement pattern during a functional activity test within a single session of motor skill training. Following skill training, people with LBP displayed decreased lumbar excursion in the early phase of the movement that was similar to the amount displayed by participants with healthy backs and decreased pain with performance of the functional activity. The person's preferred movement pattern during the PUO test and duration of LBP symptoms were associated with a person's ability to modify his or her preferred lumbar movement pattern.

Author Contributions and Acknowledgments

Concept/idea/research design: A.V. Marich, V.M. Lanier, G.B. Salsich, C.E. Lang, L.R. Van Dillen

Writing: A.V. Marich, G.B. Salsich, C.E. Lang, L.R. Van Dillen

Data collection: A.V. Marich

Data analysis: A.V. Marich, G.B. Salsich, C.E. Lang

Project management: A.V. Marich, L.R. Van Dillen

Fund procurement: L.R. Van Dillen

Providing facilities/equipment: L.R. Van Dillen

Clerical/secretarial support: L.R. Van Dillen

Consultation (including review of manuscript before submitting): V.M. Lanier, G.B. Salsich, L.R. Van Dillen

The authors thank Ching-Ting Hwang; Kristen Roles, MS; Sara Francois, DPT; Jennifer Jarvis, MS; and the members of the Musculoskeletal Analysis Laboratory at Washington University in St Louis, Missouri, who assisted in the development of the project.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Human Research Protection Office at Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, Missouri. All participants signed a written informed consent form approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Human Research Protection Office.

Funding

This work was partially funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research (grant no. R01 HD047709), a Foundation for Physical Therapy Promotion of Doctoral Studies Scholarship, and the Dr Hans and Clara Davis Zimmerman Foundation.

Disclosures and Presentations

The authors completed the ICJME Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. They reported no conflicts of interest.

This work was presented in poster format at the World Congress on Low Back and Pelvic Girdle Pain, October 31–November 4, 2016, in Singapore.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Croft PR, Macfarlane GJ, Papageorgiou AC, Thomas E, Silman AJ. Outcome of low back pain in general practice: a prospective study. BMJ. 1998;316:1356–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guo HR, Tanaka S, Cameron LL et al. Back pain among workers in the United States: National estimates and workers at high risk. Am J Ind Med. 1995;28:591–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hoy D, March L, Brooks P et al. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:968–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Frymoyer JW, Catsbaril WL. An overview of the incidences and costs of low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am. 1991;22:263–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wahlgren DR, Atkinson JH, Epping-Jordan JE et al. One-year follow-up of first onset low back pain1. Pain. 1997;73:213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mortimer M, Ahlberg G MUSIC-Norrtälje Study Group . To seek or not to seek? Care-seeking behaviour among people with low-back pain. Scand J Public Health. 2003;31:194–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ferreira ML, Machado G, Latimer J, Maher C, Ferreira PH, Smeets RJ. Factors defining care-seeking in low back pain - A meta-analysis of population based surveys. Eur J Pain. 2010;14:747.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Malmivaara A, Koes BW. Meta-Analysis: Exercise therapy for nonspecific low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:765–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hayden JA, van Tulder M, Tomlinson G. Systematic review: strategies for using exercise therapy to improve outcomes in chronic low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:776–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Macedo LG, Maher CG, Latimer J, McAuley JH. Motor control exercise for persistent, nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2009;89:9–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Maher CG, Herbert RD, Refshauge K. Specific stabilisation exercise for spinal and pelvic pain: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother. 2006;52:79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sahrmann SA. Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes. 1st ed St Louis, MO: Mosby; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gombatto SP, Collins DR, Engsberg JR, Sahrmann SA. Patterns of lumbar region movement during trunk lateral bending in 2 subgroups of people with low back pain. Phys Ther. 2007;87:441–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Van Dillen LR, Gombatto SP, Collins DR, Engsberg JR, Sahrmann SA. Symmetry of timing of hip and lumbopelvic rotation motion in 2 different subgroups of people with low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scholtes SA, Gombatto SP. Differences in lumbopelvic motion between people with and people without low back pain during two lower limb movement tests. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2009;24:7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Van Dillen LR, Sahrmann SA, Norton BJ, Caldwell CA, McDonnell MK, Bloom N. The effect of modifying patient-preferred spinal movement and alignment during symptom testing in patients with low back pain: a preliminary report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Van Dillen LR, Maluf KS, Sahrmann SA. Further examination of modifying patient-preferred movement and alignment strategies in patients with low back pain during symptomatic tests. Man Ther. 2009;14:52–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hoffman SL, Johnson MB, Zou D, Harris-Hayes M, Van Dillen LR. Effect of Classification-Specific treatment on lumbopelvic motion during hip rotation in people with low back pain. Man Ther. 2011;16:344–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rose J, Gamble JG. Human Walking. 3rd ed.Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bible JE, Biswas D, Miller CP, Whang PG, Grauer JN. Normal functional range of motion of the lumbar spine during 15 activities of daily living. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2010;23:106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cobian DG, Daehn NS, Anderson PA, Heiderscheit BC. Active cervical and lumbar range of motion during performance of activities of daily living in healthy young adults. Spine. 2013;38:1754–1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Adams MA. Biomechanics of back pain. Acupunct Med. 2004;22:178–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Adams MA, Freeman BJ, Morrison HP, Nelson IW, Dolan P. Mechanical initiation of intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine. 2000;25:1625–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McGill SM. The biomechanics of low back injury: implications on current practice in industry and the clinic. J Biomech. 1997;30:465–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Picavet HS, Schouten JS. Physical Load in Daily Life and Low Back Problems in the General Population: the MORGEN study. Prev Med. 2000;31:506–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marich AV, Hwang CT, Salsich GB, Lang CE, Van Dillen LR.. Consistency of a lumbar movement pattern across functional activities in people with low back pain. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2017;44:45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gombatto SP, Collins DR, Sahrmann SA, Engsberg JR. Gender differences in pattern of hip and lumbopelvic rotation in people with low back pain. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2006;21:263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Scholtes SA, Gombatto SP, Van Dillen LR. Gender differences in timing of lumbopelvic movement during the clinical test of active knee flexion. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38:A69. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marich AV, Bohall SC, Hwang CT, Sorensen CJ, Van Dillen LR.. Lumbar movement pattern during a clinical test and a functional activity test in people with and people without low back pain. In: American Society of Biomechanics 39th Annual Meeting. Columbus, OH: August 5–8, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Scholtes SA, Norton BJ, Lang CE, Van Dillen LR.. The effect of within-session instruction on lumbopelvic motion during a lower limb movement in people with and people without low back pain. Man Ther. 2010;15:496–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Luomajoki H, Kool J, de Bruin ED, Airaksinen O. Improvement in low back movement control, decreased pain and disability, resulting from specific exercise intervention. Sports Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2010;2:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Karni A, Meyer G, Jezzard P, Adams MM, Turner R, Ungerleider LG. Functional MRI evidence for adult motor cortex plasticity during motor skill learning. Nature. 1995;377:155–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Scholz J, Klein MC, Behrens TEJ, Johansen-Berg H. Training induces changes in white-matter architecture. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1370–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Draganski B, Gaser C, Busch V, Schuierer G, Bogdahn U, May A. Changes in grey matter induced by training. Nature. 2004;427:311–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Draganski B, May A. Training-induced structural changes in the adult human brain. Behav Brain Res. 2008;192:137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tsao H, Galea MP, Hodges PW. Driving plasticity in the motor cortex in recurrent low back pain. Eur J Pain. 2010;14:832–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Costa LO, Maher CG, Latimer J et al. Motor control exercise for chronic low back pain: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2009;89:1275–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Adkins DL, Boychuk J, Remple MS, Kleim JA. Motor training induces experience-specific patterns of plasticity across motor cortex and spinal cord. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:1776–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Barnett ML, Ross D, Schmidt RA, Todd B. Motor skills learning and the specificity of training principle. Res Q. 1973;44:440–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, O’Brien JP. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy. 1980;66:271–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Von Korff M. Studying the natural history of back pain. Spine. 1994;19(Supplement):2041S–2046S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bigos SJ, Holland J, Holland C, Webster JS, Battie M, Malmgren JA. High-quality controlled trials on preventing episodes of back problems: systematic literature review in working-age adults. Spine J. 2009;9:147–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-ltem Short-Form health survey (SF-36). Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94:149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Downie WW, Leatham PA, Rhind VM, Wright V, Branco JA, Anderson JA. Studies with pain rating scales. Ann Rheum Dis. 1978;37:378–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fritz JM, Irrgang JJ. A comparison of a modified Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire and the quebec back pain disability scale. Phys Ther. 2001;81:776–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main CJ. A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain. 1993;52:157–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nelson RM. Low Back Atlas of Standardized Tests/Measures. Morgantown, WV: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kleim JA, Jones TA. Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity: implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2008;51:S225–S239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Norton BJ, Sahrmann SA, Van Dillen LR. Differences in measurements of lumbar curvature related to gender and low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34:524–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sorensen CJ, Norton BJ, Callaghan JP, Hwang CT, Van Dillen LR. Is lumbar lordosis related to low back pain development during prolonged standing? Man Ther. 2015;20:553–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Youdas JW, Suman VJ, Garrett TR. Reliability of measurements of lumbar spine sagittal mobility obtained with the flexible curve. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995;21:13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shum GLK, Crosbie J, Lee RYW. Effect of low back pain on the kinematics and joint coordination of the lumbar spine and hip during sit-to-stand and stand-to-sit. Spine. 2005;30:1998–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shum GLK, Crosbie J, Lee RYW. Movement coordination of the lumbar spine and hip during a picking up activity in low back pain subjects. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:749–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shum GLK, Crosbie J, Lee RYW. Symptomatic and asymptomatic movement coordination of the lumbar spine and hip during an everyday activity. Spine. 2005;30:E697–E702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Thomas JS, Gibson GE. Coordination and timing of spine and hip joints during full body reaching tasks. Hum Mov Sci. 2007;26:124–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Thomas JS, Corcos DM, Hasan Z. Kinematic and kinetic constraints on arm, trunk, and leg segments in target-reaching movements. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:352–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.