Abstract

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a prevalent pathology associated with elevated cerebrovascular disease risk. We determined wall mechanics and vascular reactivity in ex vivo middle cerebral arteries (MCA) from male Goto-Kakizaki rats (GK; ~17 wk old) versus control Wistar Kyoto rats (WKY) to test the hypothesis that the diabetic environment in GK, in the absence of obesity and other comorbidities, leads to endothelial dysfunction and impaired vascular tone regulation. Dilation of MCA following challenge with acetylcholine and hypoxia was blunted in MCA from GK versus WKY, due to lower nitric oxide bioavailability and altered arachidonic acid metabolism, whereas myogenic activation and constrictor responses to serotonin were unchanged. MCA wall distensibility and cross-sectional area were not different between GK and WKY, suggesting that wall mechanics were unchanged at this age, supported by the determination that MCA dilation to sodium nitroprusside was also intact. With the use of ex vivo aortic rings as a bioassay, altered vascular reactivity determined in MCA was paralleled by relaxation responses in artery segments from GK, whereas measurements of vasoactive metabolite production indicated a loss of nitric oxide and prostacyclin bioavailability and an increased thromboxane A2 production with both methacholine challenge and hypoxia. These results suggest that endothelium-dependent dilator reactivity of MCA in GK is impaired with T2DM, and that this impairment is associated with the genesis of a prooxidant/pro-inflammatory condition with diabetes mellitus. The restriction of vascular impairments to endothelial function only, at this age and development, provide insight into the severity of multimorbid conditions of which T2DM is only one constituent.

Keywords: cerebral circulation, metabolic disease, rat models of diabetes, vascular tone regulation

INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is both a widespread and growing public health concern. In the United States, the Center for Disease Control reports that T2DM accounts for 95% of all diagnosed cases of diabetes (13), representing nearly 400 million people worldwide (38); whereas, in Canada, from 2015 to 2025, the prevalence of T2DM is expected to increase by 44% (47). T2DM is categorized by a collection of metabolic conditions associated with hyperglycemia, caused by insulin resistance, and in some cases there can also be a relative insulin deficiency (53). Since the vascular complications of T2DM are some of the most crucial manifestations of the disease (48), such as stroke and diabetic neuropathy, an understanding of the degree of T2DM-induced vascular dysfunction and its mechanisms is required for targeted therapeutic strategies. Moreover, the total estimated cost of diagnosed diabetes in 2017, in the United States alone, was $327 billion, including $237 billion in direct medical costs and $90 billion in reduced productivity, which is 26% greater than the inflation-adjusted cost in 2012 (5). The growing economic burden coupled with poor quality of life outcomes and increased mortality (38) makes gaining a better understanding of T2DM of high public importance.

Previous studies have used animal models of metabolic syndrome, a pathology that combines obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and T2DM, and is accompanied by a proinflammatory and prooxidant condition to study the combined effects of metabolic dysfunction on the structure and function of the vasculature (10). The findings included endothelial dysfunction in which a reduction in the bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO) was found, leading to impaired dilation (20) and increased constrictor response (45), and vascular remodeling characterized by increased medial hypertrophy and collagen deposition (19, 23, 56). However, the presence of confounding factors, such as obesity and hypertension, makes it difficult to discern the extent to which T2DM alone contributes to developing vasculopathy. The Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rat provides a valuable model for examining T2DM in the absence of the aforementioned confounding pathologies, as it spontaneously develops hyperglycemia and insulin resistance early in life, with blood glucose concentration ranges that mirror those observed in afflicted people (30).

Adults with T2DM have a 2- to 3-fold increased risk of ischemic stroke (54), a 1.5-fold increased risk for hemorrhagic stroke (14), and a decreased occurrence of the strong warning sign of a transient ischemic attack to provide an opportunity for medical intervention to prevent a complete stroke (2). Accordingly, increased mortality, severity, and rate of occurrence are reported in the diabetic condition (7, 29, 33, 37, 41, 55). Given the importance between vessel reactivity and blood flow, even small changes in vascular function can severely compromise cerebral perfusion (43). As such, a thorough understanding of how T2DM impacts myogenic tone, endothelial function, and smooth muscle constriction, including contributions from proinflammatory and prooxidant conditions, represents an area of investigation requiring greater clarity. Considering the detrimental consequences for poor stroke outcomes on cognitive impairment and quality of life, a rigorous understanding of the changes to the cerebral circulation occurring in T2DM is imperative.

Vascular abnormalities in the GK rat, such as impaired myogenic reactivity of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) of the GK rat, along with the degree to which vascular remodeling and neovascularization occur (1, 17, 26, 31, 42, 46, 54, 56), have previously been investigated. Specifically, increased myogenic tone (1), along with medial thickening and collagen deposition (34), were found in the MCA of the GK rat, leading to a decrease in baseline cerebral perfusion. However, the underlying vascular reactivity of the MCA in the GK rat to both mechanical and pharmacological challenges has yet to be elucidated, along with the contributing mechanisms. Therefore, the purpose of the study was to determine whether alterations to the regulation of cerebral vascular tone exist in a nonobese model of T2DM and to determine the mechanistic contributors to changes in this response compared with a control Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rat. This study tested the hypothesis that the proinflammatory and high oxidative stress environment present in the GK rat will lead to endothelial dysfunction and thus impairments in vascular tone regulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Male WKY (n = 12) and GK (n = 12) rats were acquired from Charles River Laboratories and were maintained on standard chow and drinking water ad libitum. All animals were housed in an accredited animal care facility, and all procedures had received prior Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval. At ~17 wk, rats were anesthetized with injections of pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg ip), and a carotid artery was cannulated for determination of mean arterial pressure (MAP). From each animal, a venous blood sample was also acquired from a cannula within the jugular vein for the determination of circulating endocrine, oxidant, and inflammatory biomarkers. At this point, all rats received a low dose of heparin (100 IU/kg iv) to prevent blood coagulation during the subsequent tissue harvest.

Preparation and study of isolated MCA.

While deeply anesthetized, each rat was decapitated, after which the brain was removed from the skull case and placed in cold physiological salt solution (PSS; 4°C). Subsequently, the MCA were dissected from their origins at the Circle of Willis. While somewhat larger than the classic definitions of “arteriole” based on diameter, the MCA is the major site of resistance to perfusion into the brain (35). Each MCA was doubly cannulated in a heated chamber (37°C) that allowed the lumen and exterior of the vessel to be perfused and superfused, respectively, with PSS from separate reservoirs (11). The PSS was equilibrated with a 21% O2, 5% CO2, and 74% N2 gas mixture and had the following composition (mM): 119 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.17 MgSO4, 1.6 CaCl2, 1.18 NaH2PO4, 24 NaHCO3, 0.026 EDTA, and 5.5 glucose. Any side branches were ligated using a single strand teased from 6 to 0 suture. Vessel diameter was measured using television microscopy and an on-screen video micrometer.

After cannulation, MCA extended to their in situ length and were equilibrated at 80% of the animal’s MAP (81 ± 3 mmHg for WKY; 82 ± 4 mmHg for GK) to approximate in vivo perfusion pressure (35). Any vessel that did not demonstrate significant active tone at the equilibration pressure was discarded. Active tone at the equilibration pressure was calculated as (ΔD/Dmax)·100, where ΔD is the diameter increase from rest in response to Ca2+-free PSS, and Dmax is the maximum diameter measured at the equilibration pressure in Ca2+-free PSS.

All measurements of the reactivity of MCA were taken under conditions of spontaneous tone (i.e., no preconstriction of the MCA was used for any of the results in the present study). After equilibration, the dilator reactivity of MCA was assessed in a cumulative response to increasing concentrations of acetylcholine (10−10 M to 10−6 M) added to the perfusate, as well as the imposition of hypoxia [reduction in superfusate/perfusate Po2 ~ 140 Torr (21% O2) to ~35 Torr (0% O2); measured using World Precision Instruments Oxygen Sensor, Sarasota, FL]. MCA responses to increasing concentrations of acetylcholine and to hypoxia were also measured after incubation (45–60 min) with Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME; 10−4 M), indomethacin (INDO; 10−5 M), or 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPOL; 10−4 M), to assess the contributions of NO synthase (NOS), cyclooxygenases, or reactive oxygen species, respectively, in modulating vascular reactivity.

Myogenic properties were assessed in MCA over the range of intraluminal pressures (5 mmHg and then 20–160 mmHg in 20-mmHg increments; this avoids the potential for the creation of a negative pressure at the lowest value). Intraluminal perfusion pressures were changed nonsequentially, and vessels were allowed 10 min to equilibrate at each pressure before the arterial inner and outer diameters were recorded. Constrictor responses of MCA were also assessed in response to challenge with increasing concentrations of serotonin (5-HT; 10−11 M to 10−6 M) or the thromboxane A2 (TxA2) analog U46619 (10−12 M to 10−8 M), whereas dilator responses to NO or prostacyclin (PGI2) were assessed using increasing concentrations of sodium nitroprusside (10−10 M to 10−6 M) or iloprost (10−12 M to 10−8 g/ml), respectively.

Removal of the vascular endothelium.

The endothelium of the MCA was removed via air bolus perfusion (35). Subsequently, PSS perfusion through the lumen was restored, and the artery was allowed to reequilibrate for 30 min. Endothelium denudation procedures were deemed successful when vessel dilator reactivity to 10−6 M acetylcholine was eliminated, and when reactivity of the vessel to the endothelium-independent agonist sodium nitroprusside (10−7 M) was not altered from responses determined in intact vessels.

After the experimental procedures for measuring ex vivo vascular reactivity, the perfusate and superfusate PSS were replaced with Ca2+-free PSS containing the metal ion chelators EDTA (0.03 mM) and EGTA (2.0 mM). Vessels were challenged with 10−7 M 5-HT until all active tone was lost (due to the progressive removal of calcium by the chelators in the Ca2+-free PSS (42). Subsequently, intraluminal pressure within the isolated vessel was altered in the identical manner as that for the determination of myogenic activation (discussed above). After 5–10 min at each intraluminal pressure, the inner and outer diameter of the passive MCA was determined.

Preparation of aortic rings.

Immediately after decapitation, the descending aorta was surgically removed from each euthanized rat, cleaned of adipose and connective tissue, and sectioned into 3–4 mm rings for ex vivo study using a standard tissue myograph technique (32). Each ring was mounted in a myobath chamber between a fixed point and a force transducer (World Precision Instruments) and equilibrated at a resting tension of 0.5-g tension for 45 min to equilibrate. The organ baths contained PSS at 37°C, aerated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Rings were preconditioned by treatment with 10−7 M phenylephrine for 5 min, after which 10−5 M methacholine (MCh) was added to the bath to assess endothelial integrity. Any ring that failed to demonstrate both a brisk constrictor response to phenylephrine and viable endothelial function was discarded. Subsequently, rings were challenged with increasing cumulative concentrations of phenylephrine (10−10 to 10−4 M), increasing cumulative concentrations of MCh (10−10 M to 10−4 M; following pretreatment with 10−7 M phenylephrine), hypoxia, by reducing the aeration gas to either 21% or 0% O2 (after pretreatment with 10−7 M phenylephrine), and increasing cumulative concentrations of sodium nitroprusside (10−10 M to 10−4 M; after pretreatment with 10−7 M phenylephrine).

The responses of aortic rings to MCh or hypoxia were also measured after incubation (45–60 min) with l-NAME (10−4 M), INDO (10−5 M), or TEMPOL (10−4 M) to assess the contributions of NOS, cyclooxygenases, or reactive oxygen species, respectively, in modulating vascular reactivity. Pretreatment groups were individual only, and there were no combinations of treatments in the present study.

Measurement of vascular NO bioavailability.

From each rat, the abdominal aorta was removed, and vascular NO production was assessed within the tissue bath using amperometric sensors (ISO-NOP30L; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). Briefly, while the aortic rings were within the myobath, the NO sensor (ISO-NOP30L) was placed in close apposition to the endothelial surface, and a baseline level of current was obtained. Subsequently, increasing concentrations of MCh were added to achieve concentrations of 10−8 and 10−4 M in the bath, and the changes in current were determined. In addition, superfusate O2 content in the vessel chamber was also reduced to 21% or 0% O2 (from 95% under control conditions), and the level of current was determined. To verify that responses represented NOS-dependent products, these procedures were repeated following pretreatment of the aortic rings with l-NAME (10−4 M). In pilot studies, there was no discernible production of NO using the sensors in the absence of the vascular tissue.

Determination of vascular metabolites of arachidonic acid.

Vascular production of 6-keto-prostaglandin F1α (6-keto-PGF1α; the stable breakdown product of PGI2) and 11-dehydro-thromboxane B2 (11-dehydro-TxB2; the stable plasma breakdown product of TxA2), in response to challenge with 10−8 and 10−4 M MCh and with changes in superfusate O2 content (95, 21, or 0%), was assessed using pooled conduit arteries (femoral, saphenous, iliac) from each rat. Pooled arteries from each animal were incubated in microcentrifuge tubes in 1 ml of PSS for 30 min under control conditions. After this time, the superfusate was removed, stored in a new microcentrifuge tube, and frozen in liquid N2, while a new aliquot of PSS was added to the vessels, and either the MCh challenge or different O2 content was imposed for the subsequent 30 min. After the second 30-min period, this new PSS was transferred to a fresh tube, frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80°C, and the final MCh or oxygen challenges were initiated. Metabolite release by the vessels was determined using commercially available enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kits for 6-keto-PGF1α and 11-dehydro-TxB2 (Cayman). In pilot studies, there was no discernible production of 6-keto-PGF1α or 11-dehydro-TxB2 using the EIA kits in the absence of the vascular tissue.

Data and statistical analyses.

Mechanical responses following challenge with logarithmically increasing dosages of an agonist were fit with the three-parameter logistic equation:

where y represents the vessel diameter; min and max represent the lower (minimum) and upper (maximum) bounds, respectively, of the change in diameter with agonist concentration; x is the logarithm of the agonist molar concentration; and logED50 represents the logarithm of the agonist concentration (x), where the response (y) is halfway between the bounds. For the presentation of results, we have focused on the changes in the upper and lower bounds, as appropriate, as a representation of vessel reactivity, and we did not determine a consistent or significant change to the logED50 values between treatment groups. As a result of this approach, the upper and lower bound represent statistically determined asymptotes for the concentration-response relationship and does not assume that the vascular response at the highest utilized concentration of the agonist represents the maximum possible response. Rather, the sigmoidal relationship of best fit to the data will predict the statistical bound of the response given the data points entered into the model. As such, the upper or lower bound is frequently slightly larger than the response of the vessel at the highest concentration of the agonist.

The myogenic properties of MCA from each experimental group was plotted as mean diameter at each intraluminal pressure and fitted with a linear regression (y = α0 + βx), where the slope coefficient β represents the degree of myogenic activation (Δdiameter/Δpressure). Increasingly negative values of β, therefore, represent a greater degree of myogenic activation in response to changes in intraluminal pressure. A similar analysis was used to determine the NO bioavailability in response to increasing concentrations of MCh, where β represents the rate of change of NO released by the vessels in response to agonist challenge.

All calculations of passive arteriolar wall mechanics (used as indicators of structural alterations to the individual microvessel) are based on that used previously (8), with minor modification. Vessel wall cross-sectional area (CSWA) was calculated as:

where OD and ID represent arteriolar outer and inner diameter, respectively (μm).

Incremental arteriolar distensibility (DISTINC; %change in arteriolar diameter/mmHg) was calculated as:

where ΔID represents the change in internal arteriolar diameter for each incremental change in intraluminal pressure (ΔPIL).

All data are presented as means ± SE. Differences in passive mechanical characteristics, slope coefficients describing vascular reactivity or NO bioavailability, or descriptive characteristics between WKY and GK groups were assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Student-Newman-Keuls test post hoc, as appropriate. In all cases, P < 0.05 was taken to reflect statistical significance.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics.

Table 1 presents body mass, MAP, and plasma biomarker data for both the GK rat and WKY control at ~17 wk of age. The GK rat exhibited characteristic symptoms of T2DM compared with the age-matched WKY control. Plasma glucose and insulin levels were two and six times greater in GK in addition to elevated plasma biomarkers of a proinflammatory and prooxidant environment.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of WKY and GK rats used in present study

| WKY | GK | |

|---|---|---|

| Mass, g | 405 ± 11 | 347 ± 9* |

| MAP, mmHg | 103 ± 5 | 105 ± 6 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 86 ± 5 | 166 ± 12* |

| Insulin, ng/ml | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 6.6 ± 0.8* |

| Cholesterol, mg/dl | 79 ± 14 | 98 ± 13 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 118 ± 15 | 211 ± 16* |

| Nitrotyrosine, ng/ml | 11 ± 3 | 34 ± 5* |

| TNF-α, pg/ml | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 5.7 ± 0.7* |

| IL-1β, pg/ml | 6.5 ± 0.6 | 10.9 ± 0.9* |

| MCP-1, pg/ml | 35.6 ± 4.1 | 58.5 ± 5.9* |

| RANTES, pg/ml | 29.4 ± 4.8 | 88.5 ± 11.4* |

Values are means ± SE; n = 12 rats for both groups [Wistar Kyoto (WKY) and Goto-Kakizaki (GK)]. All animals were ~17 wk of age. MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; MAP, mean arterial pressure; RANTES, regulated on activation normal T-expressed and presumably secreted.

P < 0.05 vs. WKY.

Responses from ex vivo MCA.

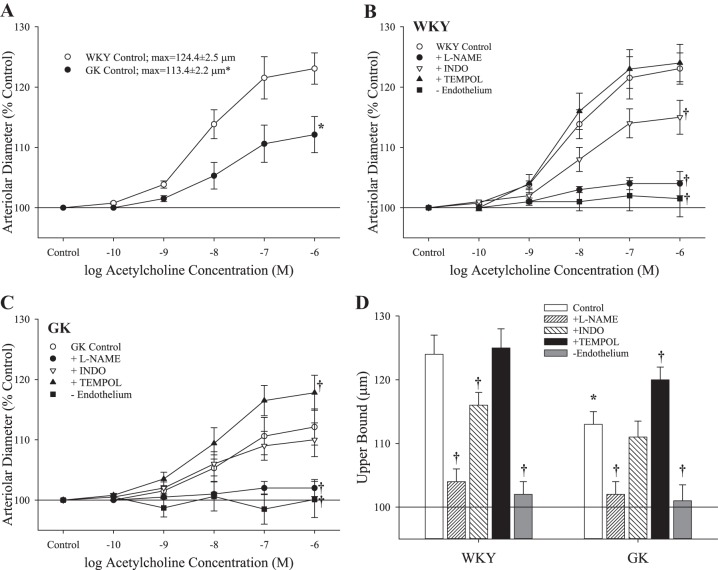

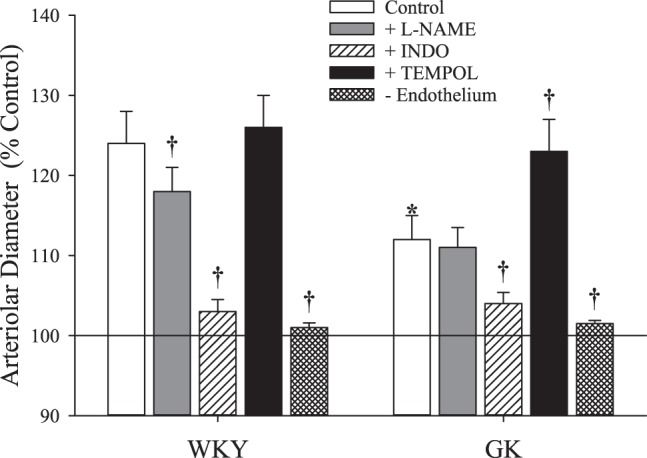

The diameters and active tone levels of the isolated MCA from WKY and GK rats under untreated conditions and following all pretreatments described above are summarized in Table 2. Dilator responses of ex vivo MCA from WKY and GK were impaired in response to challenge with increasing concentrations of acetylcholine (Fig. 1A). In MCA from WKY, acute treatment with l-NAME or INDO impaired dilation in response to acetylcholine (l-NAME > INDO), whereas treatment with TEMPOL was without effect (Fig. 1B). Similarly, pretreatment with l-NAME in MCA of GK abolished dilator responses (Fig. 1C). However, INDO treatment resulted in no net effect on dilator responses, and treatment with TEMPOL increased reactivity to acetylcholine (Fig. 1C). The upper bounds of the concentration-response curves for both strains, in response to acetylcholine under the different pretreatment conditions, are summarized in Fig. 1D. In all vessels, removal of the vascular endothelium abolished reactivity to acetylcholine.

Table 2.

Diameter and active tone of ex vivo MCA from WKY and GK rats under conditions of present study

| WKY | GK | |

|---|---|---|

| MCA diameter (baseline), μm | 135 ± 3 | 132 ± 4 |

| Active tone, % | 37 ± 2 | 36 ± 2 |

| + l-NAME, μm | 130 ± 4 | 130 ± 3 |

| Active tone, % | 38 ± 2 | 37 ± 2 |

| + INDO, μm | 132 ± 4 | 133 ± 4 |

| Active tone, % | 37 ± 2 | 35 ± 2 |

| + TEMPOL, μm | 136 ± 4 | 135 ± 4 |

| Active tone, % | 36 ± 2 | 35 ± 2 |

| − Endothelium, μm | 130 ± 3 | 131 ± 4 |

| Active tone, % | 38 ± 2 | 36 ± 2 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 6–8 rats for both groups [Wistar Kyoto (WKY) and Goto-Kakizaki (GK)]. INDO, indomethacin; l-NAME, Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester; MCA, middle cerebral arteries; TEMPOL, 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl.

Fig. 1.

The dilation of isolated middle cerebral arteries rings from Wistar Kyoto (WKY) and Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rats (n = 7 for both) in response to increasing concentrations of acetylcholine. Values (presented as means ± SE) are presented for responses under control conditions (A) and for rings from WKY (B) or GK rats (C) in response to pretreatment with Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME), indomethacin (INDO), or 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPOL). D: the upper bounds of the concentration response data in B and C. *P < 0.05 vs. responses in WKY. †P < 0.05 vs. untreated control responses within that strain. Please see text for details.

In response to hypoxia, dilator responses of MCA from GK were significantly reduced compared with that for WKY (Fig. 2). Pretreatment of MCA with l-NAME decreased hypoxic dilation in WKY, but had no effect in GK, although INDO treatment reduced dilator reactivity to hypoxia in both strains. Treatment of MCA with TEMPOL did not significantly impact hypoxic dilation in WKY, but increased responses in GK. In both strains, removal of the endothelium (passage of an air bolus through the vessel) abolished dilator reactivity to hypoxia.

Fig. 2.

The dilation of isolated middle cerebral arteries from Wistar Kyoto (WKY) and Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rats (n = 6 for both) in response to decreasing oxygen tension. Values (presented as means ± SE) are presented for responses under control conditions and after pretreatment with Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME), indomethacin (INDO), or 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPOL), or removal of the vascular endothelium. *P < 0.05 vs. responses in WKY. †P < 0.05 vs. untreated control responses within that strain. Please see text for details.

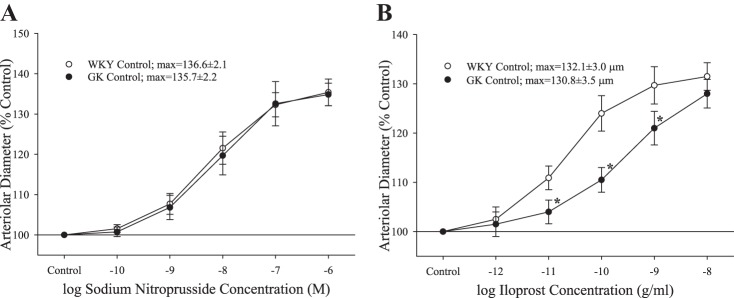

The dilator reactivity of ex vivo MCA in response to increasing concentrations of sodium nitroprusside demonstrated no differences in the responses of the vascular smooth muscle to increasing levels of NO (Fig. 3A). In contrast, dilator responses to the PGI2 analog iloprost were blunted in the midrange of the concentration-response curve in MCA from GK rats, compared with that from WKY, although the upper bounds of the relationship were not different (Fig. 3B). Pretreatment of MCA with l-NAME did not significantly impact the dilator responses to increasing concentrations of iloprost (WKY max: 129.8 ± 3.2 μm; GK max: 128.7 ± 3.3 μm).

Fig. 3.

The dilation of isolated middle cerebral arteries from Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) and Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rats (n = 6 for both) in response to increasing concentrations of sodium nitroprusside (A) or iloprost (B). Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. WKY at that agonist concentration.

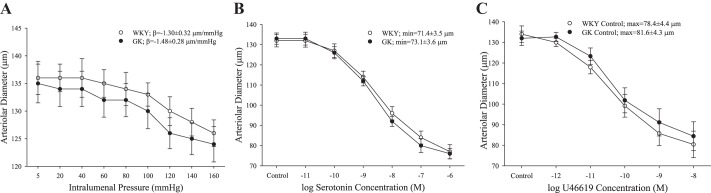

The constrictor response of isolated MCA was not different between WKY and GK, as measured by myogenic activation in response to increasing intraluminal pressure (Fig. 4A) or increasing concentrations of either 5-HT (Fig. 4B) or the TxA2 analog U46619 (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

The constriction of isolated middle cerebral arteries from Wistar Kyoto (WKY; n = 6) and Goto-Kakizaki (GK; n = 8) rats in response to increasing intraluminal pressure (A) and increasing concentrations of either serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; B) or the thromboxane A2 analog U46619 (C). Values are means ± SE. No significant differences were determined between WKY and GK in terms of constrictor reactivity.

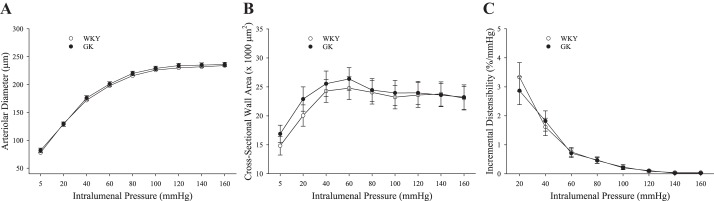

The mechanical characteristics of ex vivo MCA under Ca2+-free, passive conditions, in response to increasing intraluminal pressure, were used to determine whether there was evidence of remodeling as a consequence of T2DM. The inner diameter of the MCA (Fig. 5A), cross-sectional wall area (Fig. 5B), and incremental distensibility (Fig. 5C) of the MCA were not different between WKY and GK at any level of intraluminal pressure.

Fig. 5.

The mechanical characteristics of the wall of isolated middle cerebral arteries from Wistar Kyoto (WKY) and Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rats (n = 8 for both) under Ca2+-free conditions following altered intraluminal pressure. Values (means ± SE) are presented for arteriolar diameter (A), the cross-sectional wall area of the artery (B), and the incremental distensibility of the vessel wall (C) with increasing pressure. No significant differences were determined between WKY and GK. Please see text for details.

Responses from ex vivo aortic rings and conduit arteries.

With the use of the aortic ring as a bioassay to provide insight into alterations to MCA function with T2DM, the data from the vascular reactivity component of these studies is summarized in Table 3. The dose-constrictor responses of aortic ring in response to phenylephrine were not different between WKY and GK based on the upper bound of the relationship, whereas relaxation of aortic rings in response to challenge with increasing concentrations of MCh was decreased in GK compared with WKY. Acute treatment with the competitive NOS inhibitor l-NAME severely attenuated responses to MCh in both strains, whereas incubation with the cyclooxygenase inhibitor INDO mildly blunted relaxation to MCh in WKY, but increased relaxation responses in segments from GK. Acute treatment with antioxidant TEMPOL had no impact on MCh-induced relaxation in WKY, but increased reactivity in GK (Table 3). The relaxation of isolated aortic ring from WKY and GK in response to increasing concentration of the endothelium-independent NO donor sodium nitroprusside was not different between groups.

Table 3.

Contraction and relaxation responses of ex vivo aortic rings from WKY and GK rats in response to applied stimulus

| WKY | GK | |

|---|---|---|

| Phenylephrine (max), g | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 4.3 ± 0.3 |

| Methacholine, %max | 20.5 ± 2.8 | 38.4 ± 3.8 |

| + l-NAME | 92.4 ± 2.2* | 94.5 ± 2.4* |

| + INDO | 37.8 ± 3.2* | 24.6 ± 3.1† |

| + TEMPOL | 18.8 ± 2.4 | 21.4 ± 2.9† |

| SNP, %max | 9.4 ± 2.4 | 10.6 ± 2.6 |

| to 21% O2 | to 0% O2 | to 21% O2 | to 0% O2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Po2, %max | 45.4 ± 4.2 | 36.5 ± 3.5 | 64.1 ± 4.4 | 56.5 ± 4.6 |

| + l-NAME | 62.4 ± 3.9 | 48.2 ± 3.8 | 70.2 ± 3.6 | 55.1 ± 4.8 |

| + INDO | 82.1 ± 4.0 | 79.2 ± 3.8 | 85.4 ± 4.2 | 82.6 ± 3.9 |

| + TEMPOL | 42.5 ± 4.0 | 30.6 ± 2.9 | 56.8 ± 5.0 | 40.3 ± 4.5 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 6–8 for Wistar Kyoto (WKY) and n = 7–9 for Goto-Kakizaki (GK). Values are shown as the maximum tension developed (in response to phenylephrine) and the final percentage of the tension as a result of the subsequent condition or challenge. INDO, indomethacin; l-NAME, Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester; SNP, sodium nitroprusside; TEMPOL, 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl.

P < 0.05 vs. untreated condition in that strain.

P < 0.05 vs. WKY under that condition.

Relaxation of ex vivo aortic rings from WKY and GK in response to hypoxia was also decreased in GK group compared with the WKY for both 21% and 0% O2 content, and acute treatment of vessel rings with l-NAME or INDO impaired hypoxic relaxation in WKY. Incubation of segments with INDO blunted hypoxic relaxation in GK. In contrast, treatment with l-NAME had no impact on vessel relaxation to hypoxia, whereas TEMPOL improved reactivity at the lowest O2 level only (Table 3).

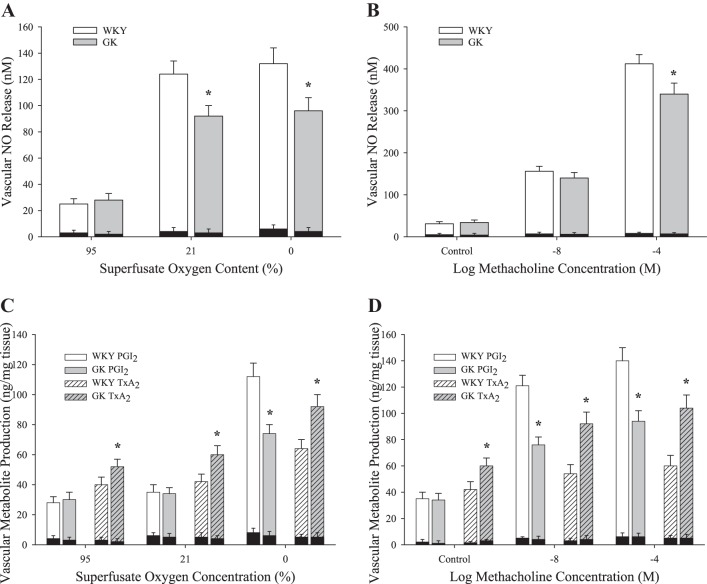

Figure 6 presents dilator metabolite production in either aortic rings (for NO) or pooled conduit arteries (for arachidonic acid metabolites) to challenge with MCh or hypoxia. In aortic rings from GK, NO release was significantly reduced in response to hypoxia (Fig. 6A) and with 10−4 M MCh (Fig. 6B) compared with responses in WKY. In response to challenge with either hypoxia (Fig. 6C) or increasing concentrations of MCh (Fig. 6D), vascular production of PGI2 was blunted in GK vs. WKY. In contrast, vascular production of TxA2 was increased in arteries from GK compared with WKY with hypoxia (Fig. 6C) or MCh (Fig. 6D). Metabolite production in the different groups following pretreatment of vascular tissue with either l-NAME (for NO production) or INDO (for PGI2 or TxA2 production) is also presented as the dark shaded bars overlaying the groups in question. l-NAME and INDO were highly effective in blunting NO or PGI2 and TxA2 production, respectively.

Fig. 6.

Data describing the production of vasoactive metabolites from arteries of Wistar Kyoto (WKY; n = 8) and Goto-Kakizaki (GK; n = 8) rats in response to decreasing oxygen tension or increasing methacholine concentration. Values (means ± SE) are presented for the release of nitric oxide with reduced Po2 (A) or increasing methacholine concentration (B) and for the production of prostacyclin (PGI2; C) and thromboxane A2 (TxA2; D) following these challenges. *P < 0.05 vs. responses in WKY for that condition. Dark shaded bars represent metabolite production after pretreatment of vessels with either Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (for nitric oxide production) or indomethacin (for PGI2 or TxA2 production). Please see text for details.

DISCUSSION

The primary observation of the present study was that the development of T2DM in the GK rat, with no other significant cardiovascular disease or cerebrovascular disease risk factors at this age, was associated with significant endothelial dysfunction relative to WKY. T2DM is a chronic disease that can lead to long-term elevations in cardiovascular disease and cerebrovascular disease with stroke, transient ischemic attack, and decreased baseline cerebral blood flow as potential outcomes (34). A critical contributor to these poor outcomes may be alterations to the integrated control of cerebral vascular tone at the level of the resistance vessels. As such, this study was designed to determine the changes to fundamental indexes of cerebral vascular tone regulation in the nonobese model of T2DM, the GK rat. The MCA is of particular interest, as it plays a central role in the regulation of cerebral blood flow and is a frequent site for occlusive ischemic events/stroke in the brain (57). As a result, changes to the reactivity of the MCA with the development of T2DM are vital in terms of acquiring an understanding of how altered aspects of cerebrovascular tone regulation with disease development can impact the control of blood flow or impaired perfusion within the brain. In addition, complementary measurements were taken from ex vivo aortic rings from WKY and GK to provide an additional bioassay to support the results in the MCA and to gain insight into mechanistic pathways where the signal to be determined may be difficult to distinguish in an isolated resistance vessel. Incorporating these data with that from our laboratory’s previous work (21) suggests that the vasculopathy that develops in the GK rat by 17 wk of age may be widespread throughout the body, and that future studies exploring underlying mechanisms and potentially ameliorative therapies should keep systemwide impacts in mind when interpreting their data.

The main evidence for endothelial dysfunction in GK was the significant impairment to dilator reactivity in the MCA (and in the aortic rings) when challenged with acetylcholine or hypoxia. Pereira et al. (44) also found a similar impairment of acetylcholine-induced aortic relaxation after preconstriction with phenylephrine in older GK rats at 8 mo of age, which they attributed to a reduction in the antioxidant capacity, leading to decreased NO bioavailability. Vascular responses to acetylcholine are highly dependent on NO bioavailability and action to dilate the vascular smooth muscle (36, 44). Given this, the present data clearly suggest that vascular NO bioavailability is reduced in GK rats by 17 wk of age following the development of T2DM, evidenced by a decreased agonist-induced vascular NO production in GK following challenge with MCh to aortic rings, while vascular reactivity to the exogenous NO donor sodium nitroprusside was maintained (44). This reduction to vascular NO bioavailability is consistently reported to evolve in parallel with oxidant stress and the development of a chronic inflammatory state (6, 17) and has been identified in the skeletal muscle microcirculation of the GK rat as well, indicating that this may be a widespread phenomenon associated with the early stages of development in T2DM (21). It appears to be a reflection of an increased scavenging to the produced NO by reactive oxygen species, decreasing its bioavailability and impairing dilation. Interestingly, previous studies (26) have reported that endothelial NOS expression is increased in GK cerebral vessels at 12 wk of age, but they too found decreased dilator reactivity and again attributed the impairment to increased scavenging to the produced NO. This is supported by the significantly improved dilator reactivity in MCA in GK, with pretreatment of the cell-permeable superoxide dismutase mimetic TEMPOL, while having no impact on dilator responses in vessels from WKY. This restoration of dilator reactivity warrants further exploration into its mechanistic bases and temporal development, such that future interventional strategies can be optimized.

Interestingly, cyclooxygenase inhibition with INDO yielded somewhat contrasting results in vessels from WKY and GK. In the control WKY group, INDO blunted the acetylcholine-mediated dilator responses of ex vivo MCA, but had minimal effect on the reactivity of GK MCA. Our data provide evidence of an increased vascular production of TxA2 and a blunting in PGI2 production measured in aortic rings following either hypoxic or MCh challenge. In WKY and GK, the differential response following pretreatment with INDO could be attributed to an oxidant stress-based shift in arachidonic acid metabolism toward an increased production of TxA2 in GK and combination of a lowered PGI2 production and a reduction in sensitivity of the vessel to the PGI2 analog iloprost (Fig. 3). Treating with INDO would remove the constrictor influences of TxA2 (and any dilator contribution via PGI2) and should fully uncover the full magnitude of the capacity for NO-mediated vasodilation of GK arteries. A restorative effect of INDO on acetylcholine-induced vascular relaxation in GK was not reported in previous studies (31, 44). However, INDO did inhibit the endothelium-derived contracting factor Up4A-mediated vasoconstriction of GK renal arteries (39), which induces vasoconstriction through the production of TxA2. Therefore, a further exploration of the role of cyclooxygenase in T2DM is needed. The results of the present study, taken in the context of previous work (24, 40), also suggest that there may be an interaction and potential compensation between the NO and prostanoid signaling pathways, both under healthy conditions and as the severity of endothelial dysfunction grows under conditions of elevated cardio-/cerebrovascular disease risk increases. Further investigation into this potential interaction and compensation and how this might be controlled or manipulated as a therapeutic route is needed.

In addition to endothelial dysfunction in GK, the results of the present study also suggest that there was no change in vasoconstrictor sensitivity either to pharmacological stimuli (5-HT or U46619) or in response to myogenic activation. Although not statistically significant, the potential for a mild increase associated with a loss of endothelium-dependent buffering of constrictor responses owing to the blunted production of dilator metabolites, such as NO or PGI2, may be present. This has been described in both GK and models of metabolic syndrome with increased maximal force production in aortic rings of GK rats and increased constrictor response of the MCA, respectively (45). The increased constriction has been attributed to the presence of ROS, causing decreased NO bioavailability (15) and thus a reduced dilator buffering capacity. However, this increased constrictor response has not been consistently found and may be age dependent, as others have found decreased sensitivity to norepinephrine in the aorta of GK rats at 12 wk of age (31), which was no longer present by 36 wk of age (31). Thus a temporal examination of the constrictor response throughout the progression of T2DM is required.

Although it was not altered in the present study, a brief discussion of myogenic activation in the GK model of T2DM is warranted, given previous studies. Foremost, there appears to be a significant age dependency that requires attention as, in Ergul’s group, 10-wk-old GK rats were found to exhibit increased cerebrovascular tone, although by 18 wk this effect was reversed and myogenic tone was found to be blunted compared with age-matched controls (28). Most studies suggest at least a partial role of hyperglycemia in mediating these changes, as supported by Cipolla et al. (16), who found decreased myogenic tone in isolated vessels exposed to acute hyperglycemia and that restoring glycemic control with metformin improves myogenic function in the mesenteric arteries of GK rats (51). Another study proposed that the enhanced myogenic tone in the diabetic GK is a result of hyperglycemia-mediated activation of ET-1 and ETA receptors (51). However, as the present study found no significant change in the constrictor reactivity to increasing intraluminal pressure, any effect on myogenic responses remains unclear in T2DM and warrants further examination.

In addition to a lack of change in constrictor response, no change in the passive mechanical characteristics of isolated MCA was found in response to changing intraluminal pressure under Ca2+-free conditions, strongly suggesting a lack of vascular remodeling in the vessels of GK at this age, severity, and duration of T2DM. While hypertension is thought to be a major stimulus of vascular remodeling in the cerebral vessels (8, 9), this was not present in the rats used in this study, and, therefore, a lack of significant remodeling is not surprising, given the presence of T2DM as the only significant risk factor at this age. However, when hypertension is present in the GK at more advanced ages, as observed by Harris et al. (23), significant increases in the wall-to-lumen ratio in MCA, resulting from medial hypertrophy and collagen deposition, have been demonstrated. It is possible, however, that, even though no change in the passive mechanical characteristics was found in the present study, some degree of vascular remodeling occurred, since, even with increased wall-to-lumen ratio found in a previous study, no change in mechanical characteristics was found (51). In their study, this was attributed to the presence of new collagen deposition rather than mature collagen, which has a more limited impact on vascular mechanics and compliance. It seems reasonable to hypothesize that, as the diabetic rat ages, a significant remodeling of the vasculature may develop with the evolution of hypertension, leading to increased mature collagen and changes to the passive mechanical characteristics of the MCA.

The GK rat provides an appropriate model for the study of nonobese T2DM, characterized by significant increases in plasma glucose, insulin, and triglycerides, coupled with increased markers of vascular oxidant stress and chronic subacute inflammation (Table 1). These characteristics are analogous to previous studies that have found between 10 and 30% less body mass in GK compared with age-matched controls, with markers of T2DM, including 50–55% higher blood glucose, dyslipidemia, and hyperinsulinemia (3, 52). Based on this, the results from the present study are likely best placed in the context of early T2DM, where the effects of the hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and dyslipidemia have yet to result in significant pancreatic β-cell dysfunction and ultimately apoptosis-inducing defective insulin secretion (4). Periods of hyperglycemia, especially in the context of insulin resistance and T2DM, have been established as a major contributor of not only the generation of reactive oxygen species (25), but also a decrease in mRNAs, proteins, and activities of various antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase (49). This shift toward a prooxidant condition, combined with glucotoxicity, contributes to the release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines measured in the present study. The increase in these proinflammatory mediators has also been consistently reported in previous studies using the GK rat and is considered a mainstay in the T2DM condition (18, 22, 30). Although outside the scope of this study, previous studies have also taken urine measurement of the GK and found increased albumin, advanced glycation end products, creatinine, and protein (3, 27, 50, 58), which is also seen in individuals with T2DM (12), further supporting the suitability of the GK as a model of T2DM.

Perspectives and Significance

This study describes some of the vascular impairments that develop in the GK model of T2DM in response to both mechanical and pharmacological stimuli. Endothelial dysfunction was present in MCA and aortic rings of GK, as demonstrated by impaired dilator reactivity in response to muscarinic agonists and hypoxia. This impairment is likely the result of the genesis of a proinflammatory and prooxidant environment in the diabetic condition, contributing to reduced NO bioavailability and a shift toward constrictor metabolite production in arachidonic acid metabolism. Given the extensive correlations between the incidence and prevalence of T2DM and negative cerebrovascular outcomes associated with the progression of the diabetic condition, this study provides a framework for additional investigation into mechanistic pathways and potential therapeutic options for restoring function in the cerebral circulation and improving current negative outcomes associated with T2DM.

GRANTS

This work was supported by awards from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (nos. 130138 and 389769), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN-2017-04536 and RGPIN-2018-05450), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIH R01 DK-64668), and the American Heart Association (EIA 0740129N).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.C.F. conceived and designed research; B.D.H. and J.C.F. performed experiments; B.D.H. and J.C.F. analyzed data; B.D.H., S.N.W., J.J.M., R.W.W., and J.C.F. interpreted results of experiments; B.D.H. and J.C.F. prepared figures; B.D.H., S.N.W., J.J.M., R.W.W., and J.C.F. drafted manuscript; B.D.H., S.N.W., J.J.M., R.W.W., and J.C.F. edited and revised manuscript; B.D.H., S.N.W., J.J.M., R.W.W., and J.C.F. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdelsaid M, Kaczmarek J, Coucha M, Ergul A. Dual endothelin receptor antagonism with bosentan reverses established vascular remodeling and dysfunctional angiogenesis in diabetic rats: relevance to glycemic control. Life Sci 118: 268–273, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Air EL, Kissela BM. Diabetes, the metabolic syndrome, and ischemic stroke: epidemiology and possible mechanisms. Diabetes Care 30: 3131–3140, 2007. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akash MS, Rehman K, Chen S. Goto-Kakizaki rats: its suitability as non-obese diabetic animal model for spontaneous type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Diabetes Rev 9: 387–396, 2013. doi: 10.2174/15733998113099990069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akash MSH, Rehman K, Chen S. Role of inflammatory mechanisms in pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Cell Biochem 114: 525–531, 2013. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Diabetes Association Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2017. Diabetes Care 41: 917–928, 2018. doi: 10.2337/dci18-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbato JE, Zuckerbraun BS, Overhaus M, Raman KG, Tzeng E. Nitric oxide modulates vascular inflammation and intimal hyperplasia in insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H228–H236, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00982.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barber M, Wright F, Stott DJ, Langhorne P. Predictors of early neurological deterioration after ischaemic stroke: a case-control study. Gerontology 50: 102–109, 2004. doi: 10.1159/000075561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumbach GL, Hajdu MA. Mechanics and composition of cerebral arterioles in renal and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 21: 816–826, 1993. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.21.6.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baumbach GL, Heistad DD. Remodeling of cerebral arterioles in chronic hypertension. Hypertension 13: 968–972, 1989. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.13.6.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks SD, DeVallance E, d’Audiffret AC, Frisbee SJ, Tabone LE, Shrader CD, Frisbee JC, Chantler PD. Metabolic syndrome impairs reactivity and wall mechanics of cerebral resistance arteries in obese Zucker rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 309: H1846–H1859, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00691.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butcher JT, Goodwill AG, Frisbee JC. The ex vivo isolated skeletal microvessel preparation for investigation of vascular reactivity. J Vis Exp 62: e3674, 2012. doi: 10.3791/3674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campion CG, Sanchez-Ferras O, Batchu SN. Potential role of serum and urinary biomarkers in diagnosis and prognosis of diabetic nephropathy. Can J Kidney Health Dis 4: 2054358117705371, 2017. doi: 10.1177/2054358117705371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen R, Ovbiagele B, Feng W. Diabetes and stroke: epidemiology, pathophysiology, pharmaceuticals and outcomes. Am J Med Sci 351: 380–386, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chettimada S, Ata H, Rawat DK, Gulati S, Kahn AG, Edwards JG, Gupte SA. Contractile protein expression is upregulated by reactive oxygen species in aorta of Goto-Kakizaki rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 306: H214–H224, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00310.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cipolla MJ, Porter JM, Osol G. High glucose concentrations dilate cerebral arteries and diminish myogenic tone through an endothelial mechanism. Stroke 28: 405–411, 1997. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.28.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dandona P, Aljada A, Chaudhuri A, Mohanty P, Garg R. Metabolic syndrome: a comprehensive perspective based on interactions between obesity, diabetes, and inflammation. Circulation 111: 1448–1454, 2005. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158483.13093.9D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donath MY, Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol 11: 98–107, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nri2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elgebaly MM, Prakash R, Li W, Ogbi S, Johnson MH, Mezzetti EM, Fagan SC, Ergul A. Vascular protection in diabetic stroke: role of matrix metalloprotease-dependent vascular remodeling. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 30: 1928–1938, 2010. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frisbee JC. Reduced nitric oxide bioavailability contributes to skeletal muscle microvessel rarefaction in the metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R307–R316, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00114.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frisbee JC, Lewis MT, Kasper JD, Chantler PD, Wiseman RW. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Goto-Kakizaki rat impairs microvascular function and contributes to premature skeletal muscle fatigue. J Appl Physiol (1985) 126: 626–637, 2019. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00751.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez LL, Garrie K, Turner MD. Type 2 diabetes—an autoinflammatory disease driven by metabolic stress. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 1864: 3805–3823, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris AK, Hutchinson JR, Sachidanandam K, Johnson MH, Dorrance AM, Stepp DW, Fagan SC, Ergul A. Type 2 diabetes causes remodeling of cerebrovasculature via differential regulation of matrix metalloproteinases and collagen synthesis: role of endothelin-1. Diabetes 54: 2638–2644, 2005. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hellsten Y, Nyberg M, Jensen LG, Mortensen SP. Vasodilator interactions in skeletal muscle blood flow regulation. J Physiol 590: 6297–6305, 2012. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.240762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ihara Y, Toyokuni S, Uchida K, Odaka H, Tanaka T, Ikeda H, Hiai H, Seino Y, Yamada Y. Hyperglycemia causes oxidative stress in pancreatic beta-cells of GK rats, a model of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 48: 927–932, 1999. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.4.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kazuyama E, Saito M, Kinoshita Y, Satoh I, Dimitriadis F, Satoh K. Endothelial dysfunction in the early- and late-stage type-2 diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rat aorta. Mol Cell Biochem 332: 95–102, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ke JT, Li M, Xu SQ, Zhang WJ, Jiang YW, Cheng LY, Chen L, Lou JN, Wu W. Gliquidone decreases urinary protein by promoting tubular reabsorption in diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats. J Endocrinol 220: 129–141, 2014. doi: 10.1530/JOE-13-0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly-Cobbs A, Elgebaly MM, Li W, Ergul A. Pressure-independent cerebrovascular remodelling and changes in myogenic reactivity in diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rat in response to glycaemic control. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 203: 245–251, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kernan WN, Inzucchi SE. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and insulin resistance: stroke prevention and management. Curr Treat Options Neurol 6: 443–450, 2004. doi: 10.1007/s11940-004-0002-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirkman MS, Mahmud H, Korytkowski MT. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 47: 81–96, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobayashi T, Matsumoto T, Ooishi K, Kamata K. Differential expression of α2D-adrenoceptor and eNOS in aortas from early and later stages of diabetes in Goto-Kakizaki rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H135–H148, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01074.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kunert MP, Dwinell MR, Drenjancevic Peric I, Lombard JH. Sex-specific differences in chromosome-dependent regulation of vascular reactivity in female consomic rat strains from a SS × BN cross. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R516–R527, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00038.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leys D, Deplanque D, Mounier-Vehier C, Mackowiak-Cordoliani M-A, Lucas C, Bordet R. Stroke prevention: management of modifiable vascular risk factors. J Neurol 249: 507–517, 2002. doi: 10.1007/s004150200057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li W, Kelly-Cobbs AI, Mezzetti EM, Fagan SC, Ergul A. Endothelin-1-mediated cerebrovascular remodeling is not associated with increased ischemic brain injury in diabetes. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 88: 788–795, 2010. doi: 10.1139/Y10-040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lombard JH, Liu Y, Fredricks KT, Bizub DM, Roman RJ, Rusch NJ. Electrical and mechanical responses of rat middle cerebral arteries to reduced Po2 and prostacyclin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 276: H509–H516, 1999. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.2.H509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lombard JH, Sylvester FA, Phillips SA, Frisbee JC. High-salt diet impairs vascular relaxation mechanisms in rat middle cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H1124–H1133, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00835.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lüscher TF, Creager MA, Beckman JA, Cosentino F. Diabetes and vascular disease: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and medical therapy. Part II. Circulation 108: 1655–1661, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000089189.70578.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 3: e442, 2006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsumoto T, Watanabe S, Kawamura R, Taguchi K, Kobayashi T. Enhanced uridine adenosine tetraphosphate-induced contraction in renal artery from type 2 diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats due to activated cyclooxygenase/thromboxane receptor axis. Pflugers Arch 466: 331–342, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1330-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitchell JA, Ali F, Bailey L, Moreno L, Harrington LS. Role of nitric oxide and prostacyclin as vasoactive hormones released by the endothelium. Exp Physiol 93: 141–147, 2008. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.038588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Després J-P, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER III, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB; Writing Group Members; American Heart Association Statistics Committee; Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 133: e38–e360, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Nueten JM, Janssens WJ, Vanhoutte PM. Serotonin and vascular reactivity. Pharmacol Res Commun 17: 585–608, 1985. doi: 10.1016/0031-6989(85)90067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paulson OB, Strandgaard S, Edvinsson L. Cerebral autoregulation. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev 2: 161–192, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pereira A, Fernandes R, Crisóstomo J, Seiça RM, Sena CM. The sulforaphane and pyridoxamine supplementation normalize endothelial dysfunction associated with type 2 diabetes. Sci Rep 7: 14357, 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14733-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phillips SA, Sylvester FA, Frisbee JC. Oxidant stress and constrictor reactivity impair cerebral artery dilation in obese Zucker rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R522–R530, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00655.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prakash R, Johnson M, Fagan SC, Ergul A. Cerebral neovascularization and remodeling patterns in two different models of type 2 diabetes. PLoS One 8: e56264, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Public Health Agency of Canada Diabetes in Canada: Facts and figures from a public health perspective. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Government of Canada, 2011, p. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rask-Madsen C, King GL. Vascular complications of diabetes: mechanisms of injury and protective factors. Cell Metab 17: 20–33, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robertson RP, Harmon JS. Diabetes, glucose toxicity, and oxidative stress: a case of double jeopardy for the pancreatic islet β cell. Free Radic Biol Med 41: 177–184, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rodrigues L, Matafome P, Crisóstomo J, Santos-Silva D, Sena C, Pereira P, Seiça R. Advanced glycation end products and diabetic nephropathy: a comparative study using diabetic and normal rats with methylglyoxal-induced glycation. J Physiol Biochem 70: 173–184, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s13105-013-0291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sachidanandam K, Hutchinson JR, Elgebaly MM, Mezzetti EM, Dorrance AM, Motamed K, Ergul A. Glycemic control prevents microvascular remodeling and increased tone in Type 2 diabetes: link to endothelin-1. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R952–R959, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90537.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sena CM, Louro T, Matafome P, Nunes E, Monteiro P, Seiça R. Antioxidant and vascular effects of gliclazide in type 2 diabetic rats fed high-fat diet. Physiol Res 58: 203–209, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siddiqui AA, Siddiqui SA, Ahmad S, Siddiqui S, Ahsan I, Sahu K. Diabetes: mechanism, pathophysiology and management—a review. Int J Drug Dev Res 5: 1–23, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sarwar N, Gao P, Seshasai SR, Gobin R, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Ingelsson E, Lawlor DA, Selvin E, Stampfer M, Stehouwer CD, Lewington S, Pennells L, Thompson A, Sattar N, White IR, Ray KK, Danesh J; The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration . Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Lancet 375: 2215–2222, 2010. [Erratum in Lancet 376: 958, 2010.] doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60484-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weimar C, Mieck T, Buchthal J, Ehrenfeld CE, Schmid E, Diener HC; German Stroke Study Collaboration . Neurologic worsening during the acute phase of ischemic stroke. Arch Neurol 62: 393–397, 2005. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yasir A, Hardigan T, Ergul A. Diabetes-mediated middle cerebral artery remodeling is restored by linagliptin: interaction with the vascular smooth muscle cell endothelin system. Life Sci 159: 76–82, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.02.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu YN, Li M-L, Xu Y-Y, Meng Y, Trieu H, Villablanca JP, Gao S, Feng F, Liebeskind DS, Xu W-H. Middle cerebral artery geometric features are associated with plaque distribution and stroke. Neurology 91: e1760–e1769, 2018. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao LC, Zhang XD, Liao SX, Gao HC, Wang HY, Lin DH. A metabonomic comparison of urinary changes in Zucker and GK rats. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010: 431894, 2010. doi: 10.1155/2010/431894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]