To elucidate the proteogenomic functional consequences of DNA copy number and methylation alterations, an integrative analysis tool iProFun was proposed. Compared to conventional approaches, iProFun achieves enhanced power and accuracy. When applied to TCGA-CPTAC ovarian cancer data, iProFun identified a collection of genes whose CNAs and/or DNA methylations influence either some or all three types of molecular traits (mRNA level, global protein, and phosphoprotein abundances). Results from this analysis may help nominate or prioritize candidate drug targets for ovarian patients.

Keywords: Proteogenomics, Molecular Function Mapping, Phosphoproteins, Gene Expression, Methylation, Ovarian Cancer, Cascading Effects, DNA Copy Number Alteration, Global Protein

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

A new algorithm, iProFun, to detect DNA alterations perturbing proteogenomic traits.

Identified CNAs (e.g. AKT1) driving corresponding mRNAs/proteins in ovarian cancer.

Identified methylations (e.g. BIN2) driving corresponding mRNAs/proteins in OV cancer.

R package of iProFun is publicly available at Github July 5, 2019.

Abstract

In this work, we propose iProFun, an integrative analysis tool to screen for proteogenomic functional traits perturbed by DNA copy number alterations (CNAs) and DNA methylations. The goal is to characterize functional consequences of DNA copy number and methylation alterations in tumors and to facilitate screening for cancer drivers contributing to tumor initiation and progression. Specifically, we consider three functional molecular quantitative traits: mRNA expression levels, global protein abundances, and phosphoprotein abundances. We aim to identify those genes whose CNAs and/or DNA methylations have cis-associations with either some or all three types of molecular traits. Compared with analyzing each molecular trait separately, the joint modeling of multi-omics data enjoys several benefits: iProFun experienced enhanced power for detecting significant cis-associations shared across different omics data types, and it also achieved better accuracy in inferring cis-associations unique to certain type(s) of molecular trait(s). For example, unique associations of CNAs/methylations to global/phospho protein abundances may imply posttranslational regulations.

We applied iProFun to ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma tumor data from The Cancer Genome Atlas and Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium and identified CNAs and methylations of 500 and 121 genes, respectively, affecting the cis-functional molecular quantitative traits of the corresponding genes. We observed substantial power gain via the joint analysis of iProFun. For example, iProFun identified 117 genes whose CNAs were associated with phosphoprotein abundances by leveraging mRNA expression levels and global protein abundances. By comparison, analyses based on phosphoprotein data alone identified none. A network analysis of these 117 genes revealed the known oncogene AKT1 as a key hub node interacting with many of the rest. In addition, iProFun identified one gene, BIN2, whose DNA methylation has cis-associations with its mRNA expression, global protein, and phosphoprotein abundances. These and other genes identified by iProFun could serve as potential drug targets for ovarian cancer.

The initiation, progression, and metastasis of cancer often results from accumulation of DNA-level variations, such as DNA copy number alterations (CNAs)1 and epigenetic modifications. CNAs involve gains or losses of a large region of tumor DNA that could result in activation of oncogenes or inactivation of tumor suppressors (1–3). Hypermethylation of CpG islands often results in silencing the expression of DNA repair genes when occurring in the promoter regions and activating oncogenes if in the coding regions (4–8). Most major cancer types have been systematically profiled for copy number and CpG methylation, and as a result, many CNAs and DNA methylations have been identified and been associated to carcinogenesis and cancer progression (9–14). However, it remains challenging to pinpoint diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic targets from this long list of cancer-associated genes. In particular, it is important to distinguish the driver genes that contribute to oncogenesis and cancer progression from the passengers acquired by random alterations during cancer evolution (2) and changes in gene activities that are the consequences, not causes, of cancer. To address this challenge, previous studies have primarily focused on associating CNAs and DNA methylations to their cis (i.e. local) gene expression levels (15), a form of molecular quantitative trait (QT) that is relatively easier to measure than protein abundances. Significant associations of CNAs and methylations with cis-mRNA expression levels partially reveal the molecular mechanisms of cancer-associated genes.

In addition to mRNA expression levels, it is of great interest to characterize the functional consequences of CNAs and DNA methylations on protein abundances. Global proteins and phosphoproteins are key molecules that carry out most cellular functions and are essential to cancer initiation, tumor progression, and response to therapy. The observed median correlations between mRNA gene expressions and global proteomic abundances, when measured and quantified in tumor tissues, are 0.45, 0.39, and 0.47 in ovarian (16), breast (17), and colorectal tumors (18), respectively. In addition to global protein abundances, phosphorylation often occurs on multiple distinct sites of a given protein, facilitating complex, multilevel regulation that is not reflected at the mRNA expression levels. By investigating the effects of CNAs (19) and separately the effects of DNA methylations (20) on global and phospho proteomic changes, novel insights have been obtained. However, due to a lack of proper analytic tools, few studies have employed an integrative approach to evaluate the impact of CNAs and DNA methylation on multilevel molecular QTs in tumor genomes from a systematic perspective.

Motivated by these challenges and needs, in this work we propose to conduct integrative analysis of multiple types of omics data in order to achieve a systematic and comprehensive understanding of the functional mechanisms of DNA-level alterations in tumors. We propose a novel integrative analysis tool to screen for proteogenomic functional traits (iProFun) altered by CNAs and DNA methylations. Specifically, we are interested in (1) detecting genes with “cascading effects” on downstream molecular traits, i.e. a gene's DNA alterations have associations with its cis mRNA expression levels, and global and phospho protein abundances and (2) identifying associations unique to certain type(s) of molecular trait(s), in particular unique to global/phospho protein levels.

Several mechanisms could result in association patterns of DNA alterations unique to the protein levels but that may not be reflected on mRNA levels. First, specific proteins may be more stable molecules and have longer half-lives than their corresponding RNAs. For example, the median mRNA half-life is ∼10 h in human cells (21), whereas certain proteins (e.g. histone proteins) degrade over months (22). Thus, in some instances protein abundances may more faithfully reflect accumulated transcription/translation activities in cells during tumor initiation and development and thus better capture the perturbations due to DNA alterations such as CNAs. Second, some DNA alterations (e.g. methylations or mutations) may result in amino acid sequence changes that alter protein-folding structures and then the degradation speeds of corresponding protein molecules. On the other hand, the matching changes on mRNA sequences may have quite limited impact on stability of mRNA molecules. Thus, associations between such DNA alteration events and protein abundances without corresponding RNA data support would be observed.

Despite the urgent needs for integrative analysis methods and tools in biomedical research, the integration of data from multiple data types imposes tremendous statistical challenges, such as high dimensionality, complex gene–gene correlations, different scales and distributions among different types of omics data, and complete or partial overlapping of samples across platforms/data types (23, 24). To address these challenges, the iProFun method takes as input genome-wide summary statistics in assessing associations of CNAs and DNA methylations on each type of molecular trait and allows genes and molecular QTs to be arbitrarily correlated in the joint analysis. The iProFun method estimates the conditional density of each type of trait separately, allowing different scales and distributions among different data types. And, it also allows for sample correlations due to complete or partial overlapping of samples. Compared with the separate analyses of CNA and then methylation on each molecular trait, iProFun leverages data from multiple sources and borrows information across data types. By imposing rigorous assessment of false discovery rates (FDR), we have demonstrated that iProFun is able to largely boost power and maintain low FDR in identifying various types of cis-associations, in particular in the data types with relatively low sample sizes.

We applied iProFun to the high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSOC) data from the cancer genome atlas (TCGA) and the genome-wide proteomic data measured in clinical proteomic tumor analysis consortium (CPTAC). HGSOC is the leading cause of gynecologic cancer death in the United States (25) for which most women will present with advanced-stage disease and ultimately die of their disease within five years (26). Thus, new treatments and an improved understanding of the biological basis of this cancer are desperately required. Using iProFun, we identified a collection of genes whose molecular functional traits at transcriptomic, proteomic, and/or phosphoproteomic levels were altered by somatic CNAs and DNA methylations. Some candidates in this list could serve as potential drug targets.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

TCGA-CPTAC Ovarian Cancer Data

The tumor sample data we analyzed were from 570 adults with HGSOC collected by TCGA. The proteomic and phosphoproteomic data were obtained from the CPTAC Data Portal and processed by the common data analysis pipeline from CPTAC. Both proteome and phosphoproteome data were acquired using iTRAQ (isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification) protein quantification methods (16). Proteome data were from among 206 samples of 174 unique patients (84 from Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, 122 from Johns Hopkins University, and 32 measured by both centers). Phosphoproteome of 69 patients were measured exclusively by Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. A total of 7,061 global proteins and 10,057 phosphosites from 2,865 phosphoproteins with high quality were considered for analysis. The somatic CNA and mRNA data from the microarray platforms were directly downloaded from CPTAC publication (16), which were summarized by gene in their pipeline. The DNA methylation data measured on the Illumina 27K platform were downloaded from the TCGA Firehose pipeline processed in July 2016 at the Broad Institute (http://gdac.broadinstitute.org/), with each methylation site taking beta values ∈ [0, 1] with 0 being unmethylated and 1 being fully methylated. Finally, the germline genotyping data were obtained from National Cancer Institute's Genomic Data Commons (27). The mRNA expression levels of 15,121 genes were measured on 569 samples, CNAs of 11,859 genes were measured in 559 samples, and DNA methylations for a total of 25,762 methylation sites from 14,269 genes were measured in 550 samples. More information about the samples and the associated metadata is available online (16, 28).

Integrative Analysis Pipeline

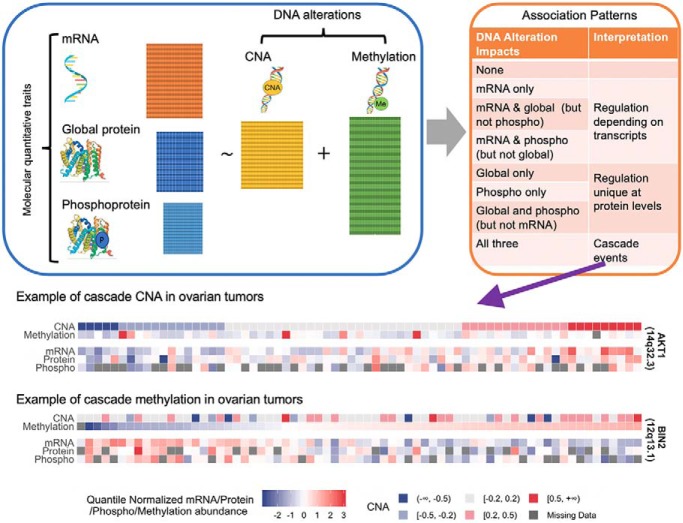

Fig. 1 illustrates the integrative analysis pipeline—iProFun—for revealing dynamic cis regulatory patterns in tumors. Briefly, iProFun takes as input the association summary statistics from associating CNAs and methylations of genes to each type of cis-molecular trait, aiming to detect the joint associations of DNA variations and molecular traits in various association patterns. Of particular interest are the genes with “cascading effects” on all cis molecular traits of interest and the genes whose functional regulations are unique at global/phospho protein levels. iProFun can incorporate prior biological knowledge through a filtering procedure and can identify significant genes with calculated posterior probabilities exceeding a threshold while assessing the empirical FDR (eFDR) through permutation. Downstream enrichment analyses were also embedded into our pipeline to allow for more direct interpretations of different association patterns.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of iProFun tool for integrative functional analysis.

Preprocessing

All of the five data types were further preprocessed to allow integrative analysis. Specifically, the HGSOC proteomic data were generated at two independent CPTAC centers at Johns Hopkins University and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, making it susceptible to center-level batch effect. We corrected center effects by analyzing the 32 overlapping samples processed in both centers, using linear normalization to match measured protein abundances. Then, we filtered genes with missing rate ≥ 50% for each of the molecular traits. The methylation data generated using the Illumina 27K platform support the existence of only one or a few methylation sites per gene. Collinearity among sites were low, and thus they were modeled simultaneously in a gene-level regression model (as discussed herein) without concern. In cases where new methylation technologies are applied, such as generating over 450,000 methylation sites, multicollinearity is likely to occur. In this case, we propose summarizing high-dimensional methylation predictors into gene level prior to considering them in the regression.

To account for potential population structures and other major unmeasured confounding factors, when obtaining the summary statistics for associations, we adjusted for the top principal components calculated based on germline genotype data, using principal component analysis provided in PLINK 1.9 (29). Blood-derived DNA samples were used as the primary source of germline genotype data, with solid normal tissue samples used as a surrogate for subjects who were missing blood-derived DNA samples. We restricted the principal component analysis to bi-allelic variants on autosomes that met the following criteria: minor allele frequency ≥ 0.05; Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium p value ≥ 0.0001; and pairwise linkage disequilibrium r2 ≤ 0.2. Finally, we restricted our analysis to genes with quantitative measurements across all five data types (CNA, methylation, mRNA expression, global protein, and phosphoprotein) to understand their joint association patterns. A total of 676 genes were analyzed in the following steps.

Gene-level Multiple Linear Regression to Obtain Summary Statistics

Consider a total of G genes that passed the preprocessing procedures in all of the five data types; n1 samples have measurements of mRNA, CNA and methylation, n2 samples have measurements of global protein, CNA and methylation, n3 samples have measurements of phosphoprotein, CNA and methylation. We use the following regression models for each type of molecular trait of interes

| (1) |

where i ∈ (1, …, n1), j ∈ (1, …, n2), and v ∈ (1, …, n3) are sample indices, g ∈ (1, …, G) is the index for genes, and cov's are the sets of covariates adjusted in the regression analyses. The mRNA, global protein, and CNA have been summarized at the gene level prior to the analysis, and as such, only one variable for each data type is included. Multiple methylation sites may exist for a gene. We use mg to denote the number of methylation sites for gene g and jointly consider all mg methylation sites in the regression. Also, multiple phosphosites might exist for a gene. We conducted a prescreening analysis to select the representing phosphosite from all measured sites of a gene by ANOVA procedure. More specifically, we selected the phosphosite that minimizes the p value from ANOVA F-test by testing the null model (phosphovg = γ0g + γ3gcovv + evg) versus the alternative model (phosphovg = γ0g + γ1gCNAvg + γ2g1methyv1 + ⋯ + γ2gmgmethyvmg + γ3gcovv + evg). In the above sets of regressions, we adjust for the top three genotype-generated principal components for all three regression models. We adjust for only three principal components based on a separate investigation in which we compare the regression results adjusting for up to 15 principal components (see Supplemental Fig. S1).

We use sets of separate regressions in Equation (1) in the integrative analysis pipeline to allow for different samples being measured for different sets of molecular features. In comparison, a joint analysis of data from all five types may have only a limited number of samples with complete measurements on all five data types, while separate analyses of data from subsets of platforms without integration would ignore the potential correlations and connections among different types of genomic features. From this perspective, iProFun is especially appealing in boosting study power for associations with proteomic features because protein and phosphoprotein data are often measured on much smaller sets of samples than that of mRNA data, and as such, power to detect associations with proteins is also much lower. Moreover, the integration of summary statistics in iProFun also allows one to take advantage of existing summary statistics when raw data are not available.

Detecting Joint Associations of DNA Alterations with Multi-omics Traits

With the association summary statistics obtained from Equation (1), we apply an integrative analysis method—Primo—to detect joint associations of DNA variation with multi-omics traits (30). The Primo algorithm is briefly summarized below.

Consider a total of G genes, and J sets of summary statistics in assessing the associations of CNAs on J-types of cis-molecular traits of interest (here J = 3) in Equation (1). Let T denote a G × J matrix of t-statistics obtained from regression. For any of the J quantitative traits, a gene can be either associated or not associated with the trait, i.e. its association status is binary. With J = 3 omics traits, there are a total of K = 2J = 8 possible association patterns for each CNA. Fig. 1 shows the list of all association patterns, as well as the interpretation for each association pattern. For example, α1g = β1g = γ1g = 0 denotes that the CNA from g-th gene has no association with any of the three types of traits, while α1g = β1g = 0; γ1g ≠ 0 and α1g ≠ 0; β1g ≠ 0; γ1g ≠ 0 denote that the CNAs that have effects on only phosphoproteins and have cascade effects on all of the three traits, respectively.

For each CNA, there must be one and only one true association pattern. Let πk denote the “frequency” of CNAs in the k-th pattern across all genes in the current data. Then the probability of CNA i following pattern k given the t-statistics is given by

| (2) |

where Dk(·) is the conditional joint density function of the set of t-statistics of CNA i on J traits, conditioning on the k-th association pattern. In this equation, both Dk(Ti) and πk are unknown and need to be estimated. In estimating the conditional joint density Dk(Ti), we assume that the t-statistics from different data types are independent, that is,

where fj0(·) and fj1(·) represent the marginal null and alternative density functions for the association statistics to the j-th trait, respectively. The qkj is an 0 or 1 index to denote the association status of the k-th pattern in data type j. For example, the second pattern (k = 2) (CNA impacts mRNA only) in Fig. 1 is α1g ≠ 0 (q_{21} = 1); β1g = γ1g = 0, q_{22} = q_{23} = 0 so D2 = f11·f20·f30. This does not assume statistics from different traits to be marginally independent; instead, we use πk to capture both biological correlations and sample correlations among molecular traits. When there are overlapping samples from different omics data types, the t-statistics from different data types could be correlated. In the next subsection, we will further propose a permutation strategy to calculate FDR while accounting for potential sample correlation.

We applied the R limma approach (32, 33) to estimate the null and alternative density functions f's for the J sets of association statistics. Limma pools information across all genes within each set of statistics and estimates the empirical nulls as t-distributions and the empirical alternatives as scaled t-distributions with an estimated scaling parameter. In applying limma, one needs to specify a priori the estimated proportion of nonnull statistics (i.e. statistics with nonzero associations) in each set of summary statistics. Those nonnull proportion estimates can be obtained from the literature or estimated based on the data. Primo is insensitive to underspecification of the parameters within a reasonable range. In this analysis, we specify that 5% (which is an underestimation) of association statistics are from the alternative for the effects of CNA on each of the three traits.

Once we obtain the estimated Dk(T), we can estimate πk's for all association patterns in the current data using the expectation-maximization algorithm (34). When considering the association patterns as mutually exclusive “clusters,” the conditional joint density can be viewed as the “class centroid.” The estimation of the posterior probability of a CNA following a particular association pattern assesses the relative strength of that pattern compared with other patterns.

Separately, we applied the Primo method to analyze the effects of methylation sites on three types of traits, with similar parameter specifications, and obtained the results for the effects of methylations on cis-molecular traits.

False Discovery Rate Determination

In addition to calculating posterior probability for each association pattern for each gene, we proposed to also calculate the empirical FDR based on permutations. The empirical FDR can serve as an additional significance measure in accounting for the data-dependent correlation structures and sample overlapping among different data types.

To calculate the empirical FDR, we first calculated the posterior probability of a predictor being associated with an outcome by summing over all patterns that are consistent with the association of interest. For example, the posterior probability of a CNA being associated with its cis mRNA expression level was obtained by summing up the posterior probabilities in the following four association patterns—“CNA affecting mRNA only,” ”CNA affecting both mRNA & global protein,” “CNA affecting both mRNA & phophoprotein,” and “CNA affecting all three traits,” all of which were consistent with CNA being associated with mRNA expression. Then, we permuted our sample m times (e.g. m = 100) to recalculate the summary statistics and use them for calculating empirical FDRs. More specifically, for each molecular trait, we randomly permute the sample label of the trait while keeping the labels of the other two traits. Then, we reran gene-level multiple regressions and Primo analysis and calculated the posterior probability of a predictor being associated with that trait based on the null datasets. Then, for a prespecified posterior probability cutoff value α, a gene was considered positive if its posterior probability is > α. We calculated empirical FDR as

for a prespecified α value. We consider a grid of α values (e.g. among 75% < α < 100%). We consider a minimum of 75% posterior probability and an averaged empirical FDR <10% as the joint significance criteria in declaring significant associations.

Additionally, we added the following filtering procedure to incorporate prior biological knowledge. Literature has suggested that CNA amplifications have often been associated with increased molecular quantities, and CNA deletions have been linked with decreased molecular quantities (17, 18, 28). Meanwhile, variations in methylation might have associations in both directions. For example, hypermethylation in promoter regions may silence DNA repair genes (negative association), but hypermethylation in coding regions may activate oncogenes (positive association). Based on the criteria, only genes with association directions matching biological knowledge (all positive for CNA and same direction for methylation across all traits) were retained and further assessed by empirical FDR.

Empirical Simulation Assessment

To evaluate the performance of iProFun on error control and power with different sample sizes, we performed simulation assessment based on ovarian cancer data and compared the results with an alternative approach that conducted separate regression for each molecular quantitative trait. Specifically, we generated three omic outcomes using real CNA samples for the same number of genes as investigated in ovarian cancer data. In real data, the number of significant CNAs are 500, 457, and 117, and nonsignificant CNAs are 77, 219, and 559, respectively for RNA, protein, and phosphoprotein. For each CNA that was not significantly associated with a molecular trait, we simulated the effect size (coefficient) as zero and variance of regression error as the estimated value in data. For each CNA that was significantly identified, the effect size was fixed as half of the estimated coefficient, and then data were simulated centered on this effect size, using the observed variance of the regression error. We assessed the powers as well as true FDRs for sample sizes of 50, 100, and 150, respectively. For each of the sample size cohorts, we simulated 100 datasets. We applied both iProFun and linear regression to test the associations between CNA and those three omic outcomes using t-statistics. With FDR = 0.1, we assessed the powers as well as true FDRs for each sample size.

Subset Analysis

We further conducted threefold subset analysis with a random split of the samples to evaluate the replication rates and stability of identified cis associations. Specifically, stratified by the sample availability of each omic data, we randomly split the ovarian cancer data into three subsets, with each having ∼190 mRNA, 58 global protein, and 23 phosphoprotein samples. We applied iProFun to two subsets of the data for identifications and repeated this procedure three times. We calculated the threefold cross-validation consensus association sets to obtain the CNAs and DNA methylations that were identified in all three subsets of data. CNAs and DNA methylations in the consensus sets can be stably identified with different and smaller numbers of samples.

Concordant Analysis with TCGA-CPTAC Breast Cancer

It has been independently reported that ovarian and breast cancers can share genetic etiologies and driver mechanisms (35–37), and a pan-cancer study on TCGA gynecologic and breast cancers identified shared CNAs across these cancer types, more prevalent than shared DNA methylations profiles (38). With limited multi-omic proteogenomic ovarian cancer data available, we investigated the concordance of CNAs identifications among ovarian and breast cancers as a way to broadly validate the iProFun discoveries. The underlying rationale is that shared etiology often results in CNAs with similar impact on molecular traits, and thus iProFun discoveries are more likely to be valid if they are more concordant than would be expected (random associations) between ovarian and breast cancers.

Specifically, we considered 48 breast cancer samples drawn from TCGA-CPTAC consortium with -omic quantification on the same platforms as ovarian cancer. We conducted the same preprocessing procedure as ovarian cancer and applied iProFun to the samples and identified CNAs and DNA methylations associated with mRNAs, global proteins, and phosphoproteins at FDR < 10%. We calculated the percentage of breast cancer identified CNAs that were also significant in the ovarian cancer analysis and compared it with the percentage of breast cancer identified CNAs that were nonsignificant in the ovarian cancer analysis. We also investigated CNA–protein associations that were identified by iProFun but were not identified in separate analysis in ovarian cancer to determine if they were co-identified in breast cancer.

RESULTS

Landscape of CNA and DNA Methylation Association Patterns on Functional Molecular Quantitative Traits

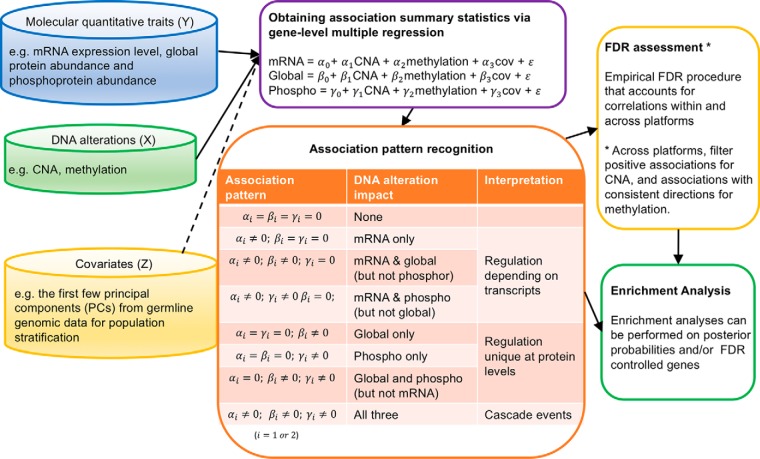

To characterize the impact of CNAs and DNA methylations on mRNA, protein and phosphoprotein abundances in ovarian tumors, we applied iProFun on TCGA and CPTAC data as described in “Methods.” The posterior probabilities of eight cis-regulation association patterns (Fig. 1) of each CNA and CpG site methylation were calculated (Supplemental Tables S1 and S2), and the average posterior probabilities across all CNAs and methylation sites are shown in Fig. 2(A). Specifically, the averaged posterior probability is 45.3% for the CNAs to be from the all three cis-regulation association patterns, i.e. CNAs are associated with all three cis-QTs: mRNA expression level, global protein, and phosphoprotein abundances. The similarly common association pattern for CNAs is “mRNA and global” (45.1%), with “mRNA only” the third most common category (7.9%). Only 1.6% of CNAs are estimated to be from the “none” association pattern, i.e. no association between CNAs and any of the three cis-QTs. On the other hand, for 1,103 DNA methylation sites of the 676 genes, the averaged posterior probability is 3.3% for the “all-three” association pattern, while 59.5% of posterior probability is from the “none” association pattern. Overall, there is a 36.3% probability for methylation sites to have a cis-regulation with transcripts (18.2% “mRNA only,” 16.9% “mRNA and global,” and 1.2% “mRNA and phospho”), and 1% for unique cis-association with protein levels (0.3% “global only,” 0.4% “phoshpo only,” and 0.4% “global and phospho”). It is clear that the effects of CNAs on cis-molecular QTs are much stronger than those of DNA methylations. Enrichment analyses based on posterior probabilities identified that chromosome arms 3p, 8q, and 10q are enriched with cascade genes with CNA associations to all three cis-molecular traits (Supplemental Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

(A) The averaged posterior probabilities of association patterns of CNAs and DNA methylations on molecular quantitative traits. (B) The Venn diagrams of the identified CNAs and methylations with effects on molecular quantitative traits that satisfy (1) FDR < 10%, (2) posterior probability >75%, and (3) positive associations for CNAs with all traits and associations with consistent directions for methylations with all traits.

After further deriving the empirical FDRs for all cis-associations based on permutation tests (see “Methods”), we selected significant association pairs by requiring (1) empirical FDRs < 10%, (2) posterior probabilities > 75%, and (3) positive associations for CNAs with all three QTs and associations with consistent directions for methylations with all three QTs. Fig. 2(B) displays the Venn diagrams of the numbers of genes whose CNAs and/or DNA methylations were significantly associated with their cis-mRNA levels and global or phosphoprotein abundances. A full list of CNAs and DNA methylation sites with significant cis-associations is provided (Supplemental Tables S1 and S2). The Venn diagram of CNAs is comprised of concentric circles, i.e. all CNAs associated with their phosphoproteins were also associated with their global proteins, and all CNAs associated with global proteins were also associated with their mRNA expression levels. Specifically, out of the 676 gene-level CNAs in our analysis, 117 CNAs were identified as cascade CNAs, i.e. the CNA demonstrates significant cis association with all of the three traits (mRNA levels and protein and phosphoprotein abundances); 340 were associated with mRNA levels and global protein abundances but not phosphoprotein abundances; and 43 CNAs were associated with mRNA levels only. The Venn diagram of methylations presented more-complex association patterns. One gene (1 site) has a cascade methylation effect, 27 genes (27 sites) have mRNA and global protein effects, 2 genes (2 sites) have mRNA and phosphoprotein effects, 90 genes (94 sites) have mRNA only effects, and 1 gene (1 site) has global protein-only effects.

Highlighting Key CNAs and DNA Methylations with Biologically Interesting Association Patterns

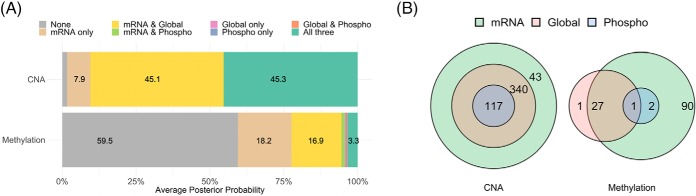

Network analysis of these 117 cascade CNAs using the STRING V10 database (39) (Supplemental Fig. S5) revealed AKT1 as a key hub node interacting with many other cascade CNAs. The associations between CNA and mRNA expression levels and global protein abundances of CNA were observed in threefold cross-validation consensus set (supplemental Table S5). The gene AKT1, located on 14q32.33, is an important effector of the PI3K/RAS pathway. The methylation site cg10590292 in BIN2 has a cascade methylation effect. The methylation of BIN2 survived the stability check (consensus set) for its association with mRNA expression levels and global protein abundances. The gene BIN2, located on 12q13.13, is related to the innate immune system pathway. In addition, the methylation site cg13859478 in CANX was associated with its global protein abundances but not with its mRNA expression levels; two sites cg25416363 and cg06043190 in RBM15 and EML4, respectively, were significantly associated with their mRNA expression levels and phosphoprotein abundances but not with their global protein levels. Cross-referencing CNAs and methylations, three genes—CDH6, MAP2, and KRT8—had cascade CNA cis-associations and were associated with global or phosphoproteins with methylation results. Detailed information of all five omics data across the 69 samples for these key genes (AKT1, BIN2, CANX, RBM15, EML4 CDH6, MAP2, and KRT8) are presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The heatmap of key identified genes among the 69 overlapping samples in which all of the five data types have been measured. AKT1 is the key hub of the cascade CNA network; BIN2 is a cascade DNA methylation; the gene CANX has a cascade CNA effect, and its methylation plays a regulatory role on global protein abundance, without mRNA reflection; the methylations of RBM15 and EML4 play a regulatory role on mRNA expression levels and phosphoprotein abundances, without global protein reflection; the genes CDH6, MAP2, and KRT8 have cascade CNA effects, and their methylations have effects on cis-mRNAs and global proteins (not identified for phosphoproteins).

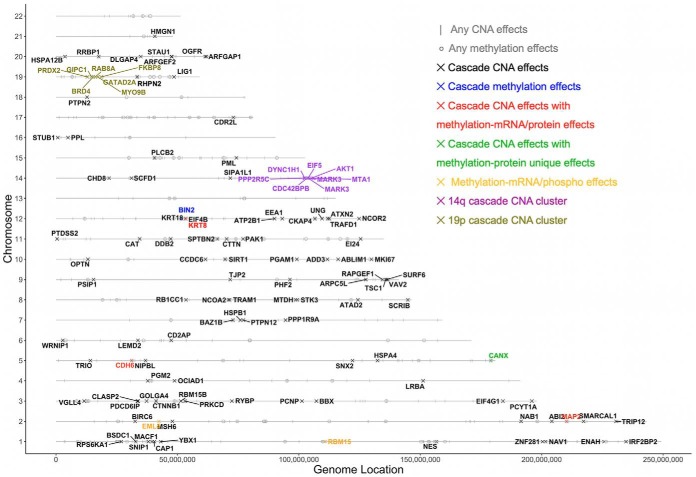

Fig. 4 demonstrates the genome distribution of all CNAs and methylations with significant cis-associations. Two cascade CNAs hotspots were identified on 14q and 19p with at least five genes within 10MB showing cascade CNA cis-regulations. The 14q hotspot sits in 14q32.31–32.33 and contains seven cascade CNAs (PPP2R5C, DYNC1H1, CDC42BPB, EIF5, MARK3, AKT1, MTA1), while the 19p hotspot sits in 19p13.2–13.11, harboring six cascade CNAs (PRDX2, GIPC1,BRD4, RAB8A, MYO9B, FKBP8). Detailed depictions of all omics data related to these genes within the two hotspot regions are presented in Supplemental Figs. S3 and S4.

Fig. 4.

The genome distribution of identified CNAs and DNA methylations. Cascade CNA effects are much more abundant than cascade methylation effects. Two cascade CNA clusters are identified on chromosome arm 14q and 19p. Genes with interesting association patterns are highlighted in the figure.

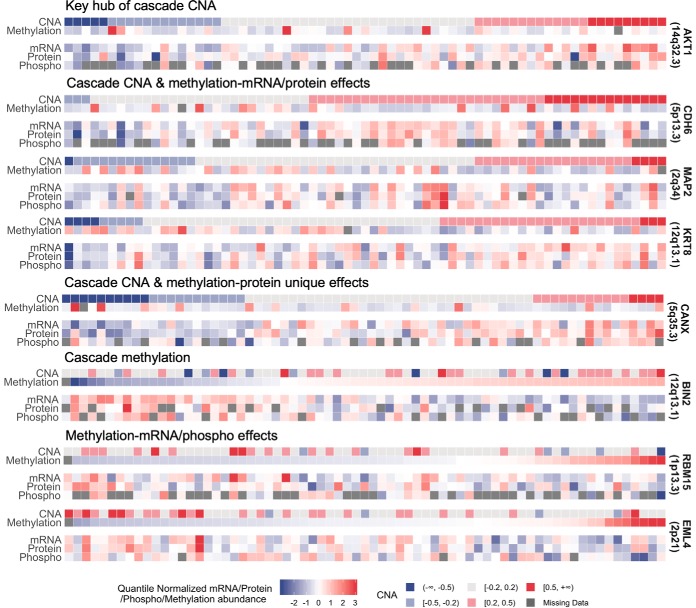

Comparison with a Conventional Method in Real Data and Simulations

We next compared the power and false discovery control of iProFun to existing approaches. iProFun employs empirical assessment of FDR instead of using commonly used FDR control procedures for the following reasons: the q-value procedure (40) and Benjamini and Hochberg procedure (41) assume independence among multiple tests, and the revised Benjamini and Yekutieli approach (42) allows only weak dependence among different tests. Because there are often unknown yet potentially high correlations among nearby genes, none of them holds valid FDR control (Supplemental Fig. S6). Therefore, empirical assessment through permutation provides more accurate assessment and should be applied for error control.

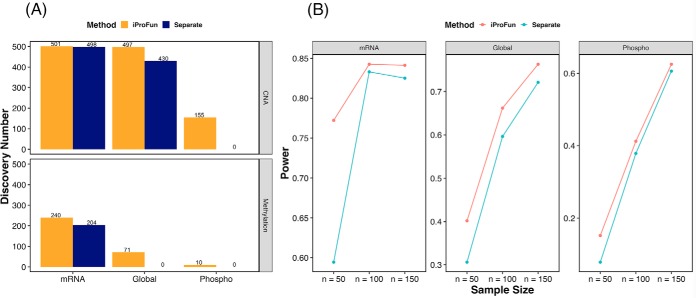

With the empirical error control, Fig. 5(A) plots the number of genes discovered under iProFun and a conventional approach that separately considers each molecular quantitative trait in the analysis. The conventional approach only uses samples that contain the molecular quantitative trait of interest for regression, adjusting for the same covariates as our integrative analysis. Using the same FDR criteria (empirical mean FDR < 10%), iProFun identifies many more genes than separate analyses by borrowing information across data types. We observed higher power gain in the data types with smaller sample sizes, such as protein and phosphoprotein abundances. We observed substantial power improvement in identifying global protein QT CNA (pQTC) (from 430 to 497 genes), phosphoprotein QT CNA (phQTC) (from 0 to 155 genes), global protein QT methylation (pQTM) (from 0 to 71), and phosphoprotein QT methylation (phQTM) (from 0 to 10 genes), as well as marginal power gain in identifying mRNA expression QT CNA (eQTC) (from 498 to 501) and mRNA expression QT methylation (eQTM) (from 204 to 240). Our integrative analysis pipeline greatly boosts study power for gene identification, especially for the data types with small initial sample sizes.

Fig. 5.

(A) Comparison between iProFun and separate analyses on the number of identified genes in ovarian cancer (FDR < 10%). (B) Power comparison between iProFun and separate analyses based on empirical simulations of ovarian cancer data.

We further demonstrated the power comparison based on empirical simulations using ovarian cancer data. Both iProFun and separate analyses preserve well-controlled false positive rates, as the simulations allow independence between different genes. However, iProFun is more powerful than separate analyses regardless of the sample sizes, effect sizes, and platforms under consideration (Fig. 5(B)). The power gain ranges from 1% to 94%, with an average 21% power increase.

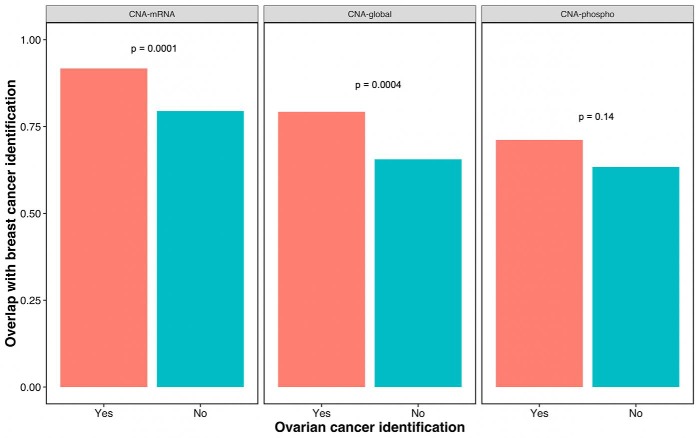

Concordance with TCGA-CPTAC Breast Cancer

We further applied iProFun to proteogenomics data from the TCGA-CPTAC breast cancer study (17). We focus on 48 samples and 2,212 genes with all CNA, methylation, mRNA, protein, and phosphoprotein measurements in the TCGA-CPTAC breast cancer datasets. Among the 2,212 genes, 593 overlapped with genes considered in the previous ovarian cancer data analysis. For these 593 genes, 526 eQTCs, 445 pQTCs, and 384 phQTCs were identified at FDR < 10% (Supplemental Tables S3 and S4). As demonstrated in Fig. 6, among 447 genes with eQTCs in ovarian cancer, 92% were also identified to have eQTCs in breast cancer. On the other hand, the replication rate was significantly lower (79%) for the 146 non-eQTCs in ovarian cancer, generating an odds ratio (OR) of 2.9 (p = 0.0001). Similarly, the percentage of breast cancer pQTC genes was 79% and 66%, respectively, among 410 ovarian pQTC genes and 183 non-pQTCs in ovarian cancer (OR = 2.0; p = 0.004); the percentage of breast cancer phQTCs were 72% and 64%, respectively, in 104 and 489 ovarian phQTC and non-phQTC genes (OR = 1.4; p = 0.14). In summary, for all three omics traits, we observed that genes with significant cis-regulations in ovarian cancer were more likely to have significant cis-regulations in breast cancer data than nonsignificant ovarian cancer associations (OR = 1.4–2.9). The concordance was strongest in eQTCs and weakest in phQTCs.

Fig. 6.

Concordance of breast cancer CNA identifications among ovarian cancer identified CNAs. It is clear that a CNA is more likely to be identified in breast cancer to be associated with mRNA (p = 0.0001) and global protein (p = 0.0004) if it is already identified by ovarian cancer.

As mention in the previous section, compared with separate analyses, iProFun demonstrates enhanced power and identified additionally 3 eQTCs, 67 pQTCs, and 155 phQTCs in the ovarian cancer data set (Fig. 5(A)). To assess the likelihood whether these additional detections represent true associations, we examined the “replication rate” of these pQTCs and phQTCs in breast cancer data. Among the 67 pQTCs and 155 phQTCs uniquely identified by iProFun in ovarian cancer, 58 and 139 genes were included in the breast cancer dataset. Among them, 69% of pQTCs and 72% of phQTCs were also confirmed to have significant cis-regulation in the breast cancer dataset. These high levels of replication rates based on an independent cohort with a different but related cancer type convincingly suggest that additional pQTC and phQTC identifications by iProFun are more likely to be biological relevant regulations than false positives due to data noises.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we introduced a novel integrative analysis tool, iProFun, to effectively detect proteogenomic functional traits altered by CNAs and DNA methylations by jointly modeling CNA, epigenome, transcriptome, global proteome, and phospho-proteome data. This integrative solution boosts power for detecting significant cis-associations and infers multi-omic association patterns by borrowing information across different omics data types.

We applied iProFun to the HGSOC tumor data from TCGA and CPTAC. HGSOC is the leading cause of gynecologic cancer death in the United States (25). In the United States this year, it is estimated that there will be more than 22,000 new ovarian cancer cases and more than 14,000 deaths (43). Five-year survival, virtually unchanged for the past 40 years, remains at ∼45% (44). Treatment failure is primarily due to the development of platinum resistance and cancer recurrence, and yet platinum remains the gold standard treatment. Following first-line use of platinum and in the absence of robust molecular guidance, nonspecific drugs with broad effects are essentially chosen in a formulaic manner for treating recurrences (45, 46). These second-line agents are selected without nationally/internationally recognized guidelines and are known to be significantly less effective, having survival improvements measurable usually in single months, and are associated with significant hematologic and nonhematologic toxicities (47–53).

Despite the tremendous efforts on reproducible delineation of molecular HGSOC subsets through large-scale next-generation sequencing profilings (28, 54–56), understanding of the mechanisms of oncogenic alterations of HGSOC is still limited and there is still a lack of therapeutically actionable genomic alterations in tumors (53, 57). Novel strategies are needed to gain insights that could lead to new treatment targets. The proposed analysis is an attempt to address this challenge by further integrating proteomics information with genomics information. By leveraging all the available molecular-level information in iProFun, we are able to identify and prioritize important alterations in the genome that have multiple functional consequences. Considering the well-known, low efficiency (at less than 5%) of translating even pharma-selected candidate therapeutic oncology targets into clinical practice, admittedly the targets discovered by iProFun will still need to be further validated and tested. However, the method provides a new way to identify candidates with known functional consequences in tumor for cancer development, progression, and resistance. Results from this analysis may help to nominate or prioritize novel candidate drug targets for ovarian cancer patients.

Specifically, using iProFun, we identified 117 CNAs that impact all levels of molecular QTs, i.e. mRNA, global, and phosphoprotein abundances, our definition of “cascade” cis-effects. This set should be enriched for biologically relevant cancer genes, as CNAs with preserved functional consequences are more likely to be cancer drivers. A network analysis of these 117 genes using the STRING database directed our attention to the gene AKT1, a key hub in the network, which interacts with many other cascade CNA genes (Supplemental Fig. S5). AKT1 is an effector in the PI3K/RAS pathway, which is deregulated in nearly half of all HGSOC cases (28), and down-regulation of its phosphoprotein was found to be associated with poor survival outcomes in the original TCGA-CPTAC ovarian study (16). While the impact of AKT1 copy number alteration was not discussed in the previous ovarian studies (16), iProFun results suggest that down-regulation of AKT1 phosphopeptides are associated with DNA copy number losses of the gene. This potentially therapeutically targetable association/pathway, as well as the other 116 cascade CNA cis-associations, however, would not have been detected if only CNA phosphoproteomics data alone would have been analyzed due to the challenge of high-dimension and low sample size in such investigations (Fig. 5).

Another interesting finding in iProFun results is the cascade effect of one methylation site cg10590292 within the bridging integrator 2 (BIN2) gene. BIN2, also called breast cancer-associated protein1, encodes a cytoplasmic protein, which influences podosome formation, motility, and phagocytosis via its interaction with the cell membrane and cytoskeleton (58) and relates to the innate immune system pathway. While the role of BIN2 in cancer is presently unknown, associations between up-regulation of BIN2 and favorable survival outcomes have been observed in all cervical, endometrial, breast, and ovarian cancers in TCGA studies (p value = 0.0001, 0.0006, 0.008, and 0.075, respectively (59)). Our analysis further suggests that the expression levels as well as protein abundances of BIN2 were suppressed by DNA methylation in a subset of ovarian patients. Intriguingly, this implies a possible mechanism affecting immune invasion in ovarian tumors.

A few other genes with biologically interesting association patterns identified by iProFun include CANX, RBM15, EML4, CDH6, MAP2, and KRT8. All have been previously shown to play different and important roles in cancers, but only CDH6 has been previously linked to ovarian cancer. CDH6 encodes a member of the cadherin superfamily. Cadherins are calcium-dependent cell adhesion proteins that play critical roles in cell differentiation and morphogenesis. CHD6 has been shown to be both highly differentially expressed in ovarian cancer and, taking advantage of its surface expression, demonstrated to be a unique therapeutic target for antibody–drug conjugates (60).

As already noted, in part, one of our reasons for targeting ovarian cancer in our studies was the current relatively bleak landscape for novel therapies. Thus, it is notable that our analyses have identified a number of therapeutic candidates. All of AKT1, KRT8, and MAP2 are druggable genes with approved drugs already on the market with indications for other tumors (61). Our results suggest that integrating multiple-omics data to screen for genes whose DNA alterations have significant impact on functional molecular traits can be a very effective strategy to nominate candidate genes contributing to the disease. While we believe that CNAs and DNA methylations, which play key roles in disease etiology of cancer, should preserve functional consequences, not all genetic alteration events with functional impacts are disease relevant. Thus, after iProFun is performed to nominate disease relevant genes, further investigation leveraging additional information, such as patient outcome data and gene–gene interaction network could further help to pinpoint the most promising candidates. In addition, the observed protein unique associations in our paper may be identified due to various biological reasons as well as power issues. Future investigation, such as comparing half-lives of corresponding mRNA and protein levels in tumor cells, will help to reveal the underlying biological mechanisms for protein unique associations.

Beyond the current studies, where we focused on the functional regulations of somatic CNA and DNA methylation, iProFun provides a general framework that can be easily extended to a wide range of applications. For example, by considering the same molecular quantitative trait from three subtypes as if it were from three omics data types with no overlapping samples, we could identify CNAs and methylations whose functional consequences are shared across subtypes versus CNAs and methylations whose functional consequences are unique to one or some of the subtypes. We could also extend the tool to germline variations, adding additional molecular QTs, and/or trans associations analysis. To provide a balanced perspective, we also note potential limitations of our analysis. First, iProFun is based on a linear regression framework and calculated the posterior probabilities using t-distributions, which might not be directly applicable to analyses that follow other distributions (e.g. χ2, F, or uniform distributions). Second, iProFun requires a relatively large number of genomic features, such as CNAs and DNA methylations, to estimate the density under the alternative distribution and robustly calculate the posterior probabilities. In cases where only a few genes are quantified, iProFun might not provide optimal results. Third, iProFun can be applied to genes that are measured across all data types of interest and, therefore, might define up fewer genes than separate analyses. Future studies could expand iProFun to incorporate more association analysis tools (e.g. provide a p-value-based algorithm) to overcome these limitations.

Software implementing the proposed iProFun, as well as CNA, DNA methylation, mRNA, global, and phosphoprotein data used for this analysis, are available on Github https://github.com/songxiaoyu/iProFun.

Data Availability

The proteomic and phosphoproteomic data were obtained from the CPTAC Data Portal https://cptac-data-portal.georgetown.edu/cptacPublic/. The somatic CNA and mRNA data from the microarray platforms were downloaded from CPTAC publications (16) and (17). The DNA methylation data were downloaded from the TCGA Firehose pipeline processed in July 2016 at the Broad Institute (http://gdac.broadinstitute.org/). The germline genotyping data were obtained from NCI's Genomic Data Commons https://gdc.cancer.gov/.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

* This work was supported by National Health Institute | National Cancer Institute U24 CA2109993 and P30 CA196521, by National Health Genome Research Institute R01 HG008980, by National Institute of General Medical Sciences R01 GM108711, and by Susan G. Komen Grant TDR16376189.

This article contains supplemental Figures and Tables.

This article contains supplemental Figures and Tables.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- CNA

- copy number alteration

- QT

- quantitative trait

- HGSOC

- high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma

- TCGA

- The Cancer Genome Atlas

- CPTAC

- Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium

- FDR

- false discovery rate

- eQTC

- expression quantitative trait CNA

- pQTC

- global protein quantitative trait CNA

- phQTC

- phosphoprotein quantitative trait CNA

- eQTM

- expression quantitative trait methylation

- pQTM

- global protein quantitative trait methylation

- phQTM

- phosphoprotein quantitative trait methylation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wang H., Liang L., Fang J.-Y., and Xu J. (2016) Somatic gene copy number alterations in colorectal cancer: New quest for cancer drivers and biomarkers. Oncogene 35, 2011–2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zack T. I., Schumacher S. E., Carter S. L., Cherniack A. D., Saksena G., Tabak B., Lawrence M. S., Zhang C.-Z., Wala J., Mermel C. H., Sougnez C., Gabriel S. B., Hernandez B., Shen H., Laird P. W., Getz G., Meyerson M., and Beroukim R. (2013) Pan-cancer patterns of somatic copy number alteration. Nat. Genet. 45, 1134–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weischenfeldt J., Dubash T., Drainas A. P., Mardin B. R., Chen Y., Stütz A. M., Waszak S. M., Bosco G., Halvorsen A. R., Raeder B., Efthymiopoulos T., Erkek S., Siegl C., Brenner H., Brustugun O. T., Dieter S. M., Northcott P. A., Petersen I., Pfister S. M., Schneider M., Solberg S. K., Thunissen E., Weichert W., Zichner T., Thomas R., Peifer M., Helland A., Ball C. R., Jechlinger M., Sotillo R., Glimm H., and Korbel J. O. (2017) Pan-cancer analysis of somatic copy-number alterations implicates irs4 and igf2 in enhancer hijacking. Nat. Genet. 49, 65–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jones P. A. (1986) DNA methylation and cancer. Cancer Res. 46, 461–466 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Joo J. E., Dowty J. G., Milne R. L., Wong E. M., Dugué P.-A., English D., Hopper J. L., Goldgar D. E., Giles G. G., and Southey M. C. (2018) Heritable DNA methylation marks associated with susceptibility to breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 9, 867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koukoura O., Spandidos D. A., Daponte A., and Sifakis S. (2014) Dna methylation profiles in ovarian cancer: Implication in diagnosis and therapy. Mol. Med. Rep. 10, 3–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wei J., Li G., Dang S., Zhou Y., Zeng K., and Liu M. (2016) Discovery and validation of hypermethylated markers for colorectal cancer. Dis. Markers 2016, 2192853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yamashita K., Hosoda K., Nishizawa N., Katoh H., and Watanabe M. (2018) Epigenetic biomarkers of promoter DNA methylation in the new era of cancer treatment. Cancer Sci. 109, 3695–3706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Slamon D. J., Clark G. M., Wong S. G., Levin W. J., Ulrich A., and McGuire W. L. (1987) Human breast cancer: Correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the her-2/neu oncogene. Science. 235, 177–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Avet-Loiseau H., Li C., Magrangeas F., Gouraud W., Charbonnel C., Harousseau J.-L., Attal M., Marit G., Mathiot C., Facon T., Moreau P., Anderson K. C., Campion L., Munshi N. C., and Minvielle S. (2009) Prognostic significance of copy-number alterations in multiple myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 4585–4590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bergamaschi A., Kim Y. H., Wang P., Sørlie T., Hernandez-Boussard T., Lonning P. E., Tibshirani R., Børresen-Dale A.-L., and Pollack J. R. (2006) Distinct patterns of DNA copy number alteration are associated with different clinicopathological features and gene-expression subtypes of breast cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 45, 1033–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cappuzzo F., Marchetti A., Skokan M., Rossi E., Gajapathy S., Felicioni L., Del Grammastro M., Sciarrotta M. G., Buttitta F., Incarbone F., Toschi L., Finocchiaro G., Destro A., Terracciano L., Roncalli M., Alloisio M., Santoro A., and Varella-Garcia M. (2009) Increased met gene copy number negatively affects survival of surgically resected non-small-cell lung cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 1667–1674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chim C. S., Liang R., Tam C. Y., and Kwong Y. L. (2001) Methylation of p15 and p16 genes in acute promyelocytic leukemia: Potential diagnostic and prognostic significance. J. Clin. Oncol. 19, 2033–2040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Calvisi D. F., Ladu S., Gorden A., Farina M., Lee J.-S., Conner E. A., Schroeder I., Factor V. M., and Thorgeirsson S. S. (2007) Mechanistic and prognostic significance of aberrant methylation in the molecular pathogenesis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 2713–2722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sharma A., Jiang C., and De S. (2018) Dissecting the sources of gene expression variation in a pan-cancer analysis identifies novel regulatory mutations. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 4370–4381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang H., Liu T., Zhang Z., Payne S. H., Zhang B., McDermott J. E., Zhou J.-Y., Petyuk V. A. Chen L., Ray D., Sun S., Yang F., Chen L., Wang J., Shah P., Cha S. W., Aiyetan P., Woo S., Tian Y., Gritsenko M. A., Clauss T. R., Choi C., Monroe M. E., Thomas S., Nie S., Wu C., Moore R. J., Yu K. H., Tabb D. L., Fenyö D., Bafna V., Wang Y., Rodriguez H., Boja E. S., Hiltke T., Rivers R. C., Sokoll L., Zhu H., Shih I. M., Cope L., Pandey A., Zhang B., Snyder M. P., Levine D. A., Smith R. D., Chan D. W., and Rodland K. D. (2016) Integrated proteogenomic characterization of human high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Cell 166, 755–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mertins P., Mani D. R., Ruggles K. V., Gillette M. A., Clauser K. R., Wang P., Wang X, Qiao J. W., Cao S., Petralia F., Kawaler E., Mundt F., Krug K., Tu Z., Lei J. T., Gatza M. L., Wilkerson M., Perou C. M., Yellapantula V., Huang K. L., Lin C., McLellan M. D., Yan P., Davies S. R., Townsend R. R., Skates S. J., Wang J., Zhang B., Kinsinger C. R., Mesri M., Rodriguez H., Ding L., Paulovich A. G., Fenyö D., Ellis M. J., and Carr S. A. (2016) Proteogenomics connects somatic mutations to signalling in breast cancer. Nature. 534, 55–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang B., Wang J., Wang X., Zhu J., Liu Q., Shi Z., Chambers M. C., Zimmerman L. J., Shaddox K. F., Kim S., Davies S. R., Wang S., Wang P., Kinsinger C. R., Rivers R. C., Rodriguez H., Townsend R. R., Ellis M. J., Carr S. A., Tabb D. L., Coffey R. J., Slebos R. J., and Liebler D. C. (2014) Proteogenomic characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 513, 382–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Geiger T., Cox J., and Mann M. (2010) Proteomic changes resulting from gene copy number variations in cancer cells. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. I Zmetakova I., Danihel L., Smolkova B., Mego M., Kajabova V., Krivulcik T., Rusnak I., Rychly B., Danis D., Repiska V., Blasko P., Karaba M., Benca J., Pechan J., and Fridrichova I. (2013) Evaluation of protein expression and DNA methylation profiles detected by pyrosequencing in invasive breast cancer. Neoplasma 60, 635–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang E., van Nimwegen E., Zavolan M., Rajewsky N., Schroeder M., Magnasco M., and Darnell J. E. Jr. (2003) Decay rates of human mRNAs: Correlation with functional characteristics and sequence attributes. Genome Res. 13, 1863–1872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mathieson T., Franken H., Kosinski J., Kurzawa N., Zinn N., Sweetman G., Poeckel D., Ratnu V. S., Schramm M., Becher I., Steidel M., Noh K. M., Bergamini G., Beck M., Bantscheff M., and Savitski M. M. (2018) Systematic analysis of protein turnover in primary cells. Nature Commun. 9, 689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sun Y. V., and Hu Y.-J. (2016) Integrative analysis of multi-omics data for discovery and functional studies of complex human diseases. In Advances in genetics, vol. 93, pp. 147–190. Elsevier; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huang S., Chaudhary K., and Garmire L. X. (2017) More is better: Recent progress in multi-omics data integration methods. Front. Genet. 8, 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Torre L. A., Trabert B., DeSantis C. E., Miller K. D., Sammi G., Runowicz C. D., Gudet M. M., Jemal A., and Siegel R. L. (2018) Ovarian cancer statistics, 2018. CA J. Cancer Clin. 68, 284–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. National Cancer Institute. (2019) SEER cancer statistics factsheets. Ovary cancer. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/ovary.html

- 27. Grossman R. L., Heath A. P., Ferretti V., Varmus H. E. Lowy D. R. Kibbe W. A., and Staudt L. M. (2016) Toward a shared vision for cancer genomic data. Engl, N. J. Med. 375, 1109–1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network et al. , (2011) Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature 474, 609–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chang C. C., Chow C. C., Tellier L. C., Vattikuti S., Purcell S. M., and Lee J. J. (2015) Second-generation PLINK: Rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 4, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gleason K. J., Yang F. Pierce B. L., He X., and Chen L. S. (2019) Primo: Integration of multiple GWAS and omics QTL summary statistics for elucidation of molecular mechanisms of trait-associated SNPs and detection of pleiotropy in complex traits. bioRxiv 579581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Deleted in proof.

- 32. Smyth G. K. (2004) Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 3, 1–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ritchie M. E., Phipson B., Wu D., Hu Y., Law C. W., Shi W., and Smyth G. K. (2015) limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dempster A. P., Laird N. M., and Rubin D. B. (1977) Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J. Royal Stat. Soc. Series B. 39, 1–22 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kar S. P., Beesley J., Al Olama A. A., Michailidou K., Tyrer J., Kote-Jarai Z. S., Lawrenson K., Lindstrom S. Ramus S. J., Thompson D. J., Kibel A. S., Dansonka-Mieszkowska A., Michael A., Dieffenbach A. K., Gentry-Maharaj A., Whittemore A. S., Wolk A., Monteiro A., Peixoto A., Kierzek A., Cox A., Rudolph A., Gonzalez-Neira A., Wu A. H., Lindblom A., Swerdlow A., Ziogas A., Ekici A. B., Burwinkel B., Karlan B. Y., Nordestgaard B. G., Blomqvist C., Phelan C., McLean C., Pearce C. L., Vachon C., Cybulski C., Slavov C., Stegmaier C., Maier C., Ambrosone C. B., Høgdall C. K., Teerlink C. C., Kang D., Tessier D. C., Schaid D. J., Stram D. O., Cramer D. W., Neal D. E., Eccles D., Flesch-Janys D., Edwards D. R., Wokozorczyk D., Levine D. A., Yannoukakos D., Sawyer E. J., Bandera E. V. Poole E. M., Goode E. L., Khusnutdinova E., Høgdall E., Song F., Bruinsma F., Heitz F., Modugno F., Hamdy F. C., Wiklund F., Giles G. G., Olsson H., Wildiers H., Ulmer H. U., Pandha H., Risch H. A., Darabi H., Salvesen H. B., Nevanlinna H., Gronberg H., Brenner H., Brauch H., Anton-Culver H., Song H., Lim H. Y., McNeish I., Campbell I., Vergote I., Gronwald J., Lubiński J., Stanford J. L., Benítez J., Doherty J. A., Permuth J. B., Chang-Claude J., Donovan J. L., Dennis J., Schildkraut J. M., Schleutker J., Hopper J. L., Kupryjanczyk J., Park J. Y., Figueroa J., Clements J. A., Knight J. A., Peto J., Cunningham J. M., Pow-Sang J., Batra J., Czene K., Lu K. H., Herkommer K., Khaw K. T., Matsuo K., Muir K., Offitt K., Chen K., Moysich K. B., Aittomäki K., Odunsi K., Kiemeney L. A., Massuger L. F., Fitzgerald L. M., Cook L. S., Cannon-Albright L., Hooning M. J., Pike M. C., Bolla M. K., Luedeke M., Teixeira M. R., Goodman M. T., Schmidt M. K., Riggan M., Aly M., Rossing M. A., Beckmann M. W., Moisse M., Sanderson M., Southey M. C., Jones M., Lush M., Hildebrandt M. A., Hou M. F., Schoemaker M. J., Garcia-Closas M., Bogdanova N., Rahman N., Le N. D., Orr N., Wentzensen N., Pashayan N., Peterlongo P., Guénel P., Brennan P., Paulo P., Webb P. M., Broberg P., Fasching P. A., Devilee P., Wang Q., Cai Q., Li Q., Kaneva R., Butzow R., Kopperud R. K., Schmutzler R. K., Stephenson R. A., MacInnis R. J., Hoover R. N., Winqvist R., Ness R., Milne R. L., Travis R. C., Benlloch S., Olson S. H., McDonnell S. K., Tworoger S. S., Maia S., Berndt S., Lee S. C., Teo S. H., Thibodeau S. N., Bojesen S. E., Gapstur S. M., Kjær S. K., Pejovic T., Tammela T. L., Dörk T., Brüning T., Wahlfors T., Key T. J., Edwards T. L., Menon U., Hamann U., Mitev V., Kosma V. M., Setiawan V. W., Kristensen V., Arndt V., Vogel W., Zheng W., Sieh W., Blot W. J., Kluzniak W., Shu X. O., Gao Y. T., Schumacher F., Freedman M. L., Berchuck A., Dunning A. M., Simard J., Haiman C. A., Spurdle A., Sellers T. A., Hunter D. J., Henderson B. E., Kraft P., Chanock S. J., Couch F. J., Hall P., Gayther S. A., Easton D. F., Chenevix-Trench G., Eeles R., Pharoah P. D., and Lambrechts D. (2016) Genome-wide meta-analyses of breast, ovarian, and prostate cancer association studies identify multiple new susceptibility loci shared by at least two cancer types. Cancer Discov. 6, 1052–1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Easton D. F., Ford D., and Bishop D. T. (1995) Breast and ovarian cancer incidence in brca1-mutation carriers. Breast cancer linkage consortium. Am J. Hum. Genet. 56, 265–271 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Amundadottir L. T., Thorvaldsson S., Gudbjartsson D. F., Sulem P., Kristjansson K., Arnason S., Gulcher J. R., Bjornsson J., Kong A., Thorsteindottir U., and Stefansson K. (2004) Cancer as a complex phenotype: pattern of cancer distribution within and beyond the nuclear family. PLoS Med. 1, e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Berger A. C., Korkut A., Kanchi R. S., Hegde A. M., Lenoir W., Liu W., Liu Y., Fan H., Shen H., Ravikumar V., Rao A., Schultz A., Li X., Sumazin P., Williams C., Mestdagh P., Gunaratne P. H., Yau C., Bowlby R., Robertson A. G., Tiezzi D. G., Wang C., Cherniack A. D., Godwin A. K., Kuderer N. M., Rader J. S., Zuna R. E., Sood A. K., Lazar A. J., Ojesina A. I., Adebamowo C., Adebamowo S. N., Baggerly K. A., Chen T. W., Chiu H. S., Lefever S., Liu L., MacKenzie K., Orsulic S., Roszik J., Shelley C. S., Song Q., Vellano C. P, Wentzensen N., Weinstein J. N., Mills G. B., Levine D. A., and Akbani R. (2018) A comprehensive pan-cancer molecular study of gynecologic and breast cancers. Cancer Cell. 33, 690–705.e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Szklarczyk D., Franceschini A., Wyder S., Forslund K., Heller D., Huerta-Cepas J., Simonovic M., Roth A., Santos A., Tsafou K. P., Kuhn M., Bork P., Jensen L. J., and von Mering C. (2015) String v10: Protein–protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D447–D452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Storey J. D., and Tibshirani R. (2003) Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 9440–9445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Benjamini Y., and Hochberg Y. (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. Royal Stat. Soc. Series B 57, 289–300 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Benjamini Y., and Yekutieli D. (2001) The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Annals Stat. 29, 1165–1188 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Siegel R. L., Miller K. D., and Jemal A. (2019) Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 69, 7–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lisio M. A., Fu L., Goyeneche A., Gao Z., and Telleria C. (2019) High-grade serous ovarian cancer: Basic sciences, clinical and therapeutic standpoints. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, E952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Narod S. (2016) Can advanced-stage ovarian cancer be cured? Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 13, 255–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Ovarian cancer including fallopian tube cancer and primary peritoneal cancer. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Davis A., Tinker A. V., and Friedlander M. (2014) “Platinum resistant” ovarian cancer: What is it, who to treat and how to measure benefit? Gynecol. Oncol. 133, 624–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hoskins P. J., and Swenerton K. D. (1994) Oral etoposide is active against platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 12, 60–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Israel V. P., Garcia A. A., Roman L., Muderspach L., Burnett A., Jeffers S., and Muggia F. M. (2000) Phase II study of liposomal doxorubicin in advanced gynecologic cancers. Gynecol. Oncol. 78, 143–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Miller D. S., Blessing J. A., Krasner C. N., Mannel R. S., Hanjani P., Pearl M. L., Waggoner S. E., and Boardman C. H. (2009) Phase ii evaluation of pemetrexed in the treatment of recurrent or persistent platinum-resistant ovarian or primary peritoneal carcinoma: A study of the gynecologic oncology group. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 2686–2691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. ten Bokkel Huinink W., Gore M., Carmichael J., Gordon A., Malfetano J., Hudson I., Broom C., Scarabelli C., Davidson N., Spanczynski M., Bolis G., Malström H., Coleman R., Fields S. C., and Heron J. F. (1997) Topotecan versus paclitaxel for the treatment of recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 15, 2183–2193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Markman M., and Bookman M. A. (2000) Second-line treatment of ovarian cancer. The Oncologist 5, 26–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tomao F., D'Incalci M., Biagioli E., Peccatori F. A., and Colombo N. (2017) Restoring platinum sensitivity in recurrent ovarian cancer by extending the platinum-free interval: Myth or reality? Cancer 123, 3450–3459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chalmers Z. R., Connelly C. F., Fabrizio D., Gay L., Ali S. M., Ennis R., Schrock A., Campbell B., Shlien A., Chmielecki J., Huang F., He F., Sun J., Tabori U., Kennedy M., Lieber D. S., Roels S., White J., Otto G. A., Ross J. S., Garraway L., Miller V. A., Stephens P. J., and Frampton G. M. (2017) Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med. 9, 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Patch A.-M., Christie E. L., Etemadmoghadam D., Garsed D. W., George J., Fereday S., Nones K., Cowin P., Alsop K., Bailey P. J., Kassahn K. S., Newell F., Quinn M. C., Kazakoff S., Quek K., Wilhelm-Benartzi C., Curry E., Leong H. S., Hamilton A., Mileshkin L., Au-Yeung G., Kennedy C., Hung J., Chiew Y. E., Harnett P., Friedlander M., Quinn M., Pyman J., Cordner S., O'Brien P, Leditschke J., Young G., Strachan K., Waring P., Azar W., Mitchell C., Traficante N., Hendley J., Thorne H., Shackleton M., Miller D. K., Arnau G. M., Tothill R. W., Holloway T. P., Semple T., Harliwong I., Nourse C., Nourbakhsh E., Manning S, Idrisoglu S, Bruxner T. J., Christ A. N., Poudel B., Holmes O., Anderson M., Leonard C., Lonie A., Hall N., Wood S., Taylor D. F., Xu Q., Fink J. L., Waddell N., Drapkin R., Stronach E., Gabra H., Brown R., Jewell A., Nagaraj S. H., Markham E., Wilson P. J., Ellul J., McNally O., Doyle M. A., Vedururu R., Stewart C., Lengyel E., Pearson J. V., Waddell N., deFazio A., Grimmond S. M., and Bowtell D. D. (2015) Whole-genome characterization of chemoresistant ovarian cancer. Nature. 521, 489–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tothill R. W., Tinker A. V., George J., Brown R., Fox S. B., Lade S., Johnson D. S., Trivett M. K., Etemadmoghadam D., Locandro B., Traficante N., Fereday S., Hung J. A., Chiew Y. E., Haviv I., Gertig D., DeFazio A., and Bowtell D. D. (2008) Novel molecular subtypes of serous and endometrioid ovarian cancer linked to clinical outcome. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 5198–5208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Villalobos V. M., Wang Y. C., and Sikic B. I. (2018) Reannotation and analysis of clinical and chemotherapy outcomes in the ovarian data set from the Cancer Genome Atlas. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2, 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sánchez-Barrena M. J., Vallis Y., Clatworthy M. R., Doherty G. J., Veprintsev D. B., Evans P. R., and McMahon H. T. (2012) Bin2 is a membrane sculpting n-bar protein that influences leucocyte podosomes, motility and phagocytosis. PloS One 7, e52401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cancer Genome Atlas Network (2012) Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 490, 61–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bialucha C. U., Collins S. D., Li X., Saxena P., Zhang X., Dürr C., Lafont B., Prieur P., Shim Y., Mosher R., Lee D., Ostrom L., Hu T., Bilic S., Rajlic I. L., Capka V., Jiang W., Wagner J. P., Elliott G., Veloso A., Piel J. C., Flaherty M. M., Mansfield K. G., Meseck E. K., Rubic-Schneider T., London A. S., Tschantz W. R., Kurz M., Nguyen D., Bourret A., Meyer M. J., Faris J. E., Janatpour M. J., Chan V. W., Yoder N. C., Catcott K. C., McShea M. A., Sun X,. Gao H., Williams J., Hofmann F., Engelman J. A., Ettenberg S. A., Sellers W. R., and Lees E. (2017) Discovery and optimization of hkt288, a cadherin-6 targeting ADC for the treatment of ovarian and renal cancer. Cancer Discov. 7, 1030–1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Cotto K. C., Wagner A. H., Feng Y.-Y., Kiwala S., Coffman A. C., Spies G., Wollam A., Spies N. C., Griffith O. L., and Griffith M. (2018) Dgidb 3.0: A redesign and expansion of the drug–gene interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D1068–D1073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The proteomic and phosphoproteomic data were obtained from the CPTAC Data Portal https://cptac-data-portal.georgetown.edu/cptacPublic/. The somatic CNA and mRNA data from the microarray platforms were downloaded from CPTAC publications (16) and (17). The DNA methylation data were downloaded from the TCGA Firehose pipeline processed in July 2016 at the Broad Institute (http://gdac.broadinstitute.org/). The germline genotyping data were obtained from NCI's Genomic Data Commons https://gdc.cancer.gov/.