Abstract

Introduction

Social media listening (SML) is an approach to assess patient experience in different indications. This is the first study to report the results of using SML to understand patients’ experiences of living with dry eye disease (DED).

Methods

Publicly available, English-language social media content between December 2016 and August 2017 was searched employing pre-defined criteria using Social Studio®, an online aggregator-tool for posts from social media channels. Using natural language processing (NLP), posts were indexed using patient lexicon and disease-related keywords to derive a set of patient posts. NLP was used to identify relevance, followed by further manual evaluation and analysis to generate patient insights.

Results

In all, 2279 possible patient records were identified following NLP, which were filtered for relevance to disease area by analysts, resulting in a total of 1192 posts which formed the basis of this study. Of these, 77% (n = 915) were from the USA. Symptoms, causes, diagnosis and treatments were the most commonly discussed themes. Most common symptoms mentioned were eye dryness (138/901), pain (114/901) and blurry vision (110/901). Pharmaceutical drugs (prescription and over-the-counter; 55%; 764/1393), followed by medical devices (20%; 280/1393), were mentioned as major options for managing symptoms. Of the pharmaceutical drugs, eye drops (33%; 158/476) and artificial tears (10%; 49/476) were the most common over-the-counter options reported, and Restasis® (22%; 103/476) and Xiidra® (6%; 27/476) were the most common prescription drugs. Patients voiced a significant impact of DED on their daily activities (4%; 9/224), work (23%; 51/224) and driving (12%; 26/224). Lack of DED specialists, standard diagnostic procedures, effective treatment options and need to increase awareness of DED among patients were identified as the key unmet needs.

Conclusions

Insights revealed using SML strengthen our understanding about patient experiences and their unmet needs in DED. This study illustrates that an SML approach contributed effectively in generating patient insights, which can be utilised to inform early drug development process, market access strategies and stakeholder discussions.

Funding

Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland.

Plain Language Summary

Plain language summary available for this article.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40123-019-0188-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Disease burden, Dry eye, Patients’ experiences, Quality of life, Social media, Twitter, Unmet needs

Plain Language Summary

Dry eye disease (DED) is a chronic health condition that affects a large number of people. The effects of DED can cause many problems in the lives of patients. Social media listening is an upcoming methodology which lends itself to researching how diseases can affect patients, by looking at what people discuss in online social media forums about their disease. The thoughts and opinions expressed openly by patients online distinguish this approach from traditional, structured and solicited patient research, and it is considered that the results of such social media listening studies should reflect spontaneous patient perspectives on their disease. In this study, patients’ internet social media posts about DED were identified using software through a keyword search and further analysed. It was found that most DED patients talked about their symptoms, causes, diagnosis and treatments when discussing DED. Most patients said they experienced eye dryness, pain and blurry vision. Daily activities like work and driving were all greatly affected by DED. Concerning what would make things better for them, patients mentioned the need for standard methods of diagnosing DED, better treatment options and need for a better awareness of the disease. Emotions expressed tended to be very negative, reflective of the impact of the disease on their lives. This study illustrates how DED negatively affects the lives of patients and highlights their unmet needs; it may help doctors, pharmaceutical companies and health insurance providers better understand the challenges faced by patients with this disease.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40123-019-0188-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Dry eye disease (DED) affects hundreds of millions of people globally [1, 2]. While the prevalence of DED increases with age [3], lifestyle changes like rising use of smartphones and tablets have resulted in increasing reports of DED among younger populations [4]. DED symptoms have a substantial impact on patients’ lives leading to eye discomfort, pain, fatigue and vision-related disturbances [5–8]. This leads to impairment of their quality of life (QoL), including aspects of physical, social and psychological functioning, daily activities and workplace productivity [7, 8]. Consequently, DED is one of the most common reasons for seeking medical eye care [1, 2], and the extensive QoL impact implies that understanding patient experiences is key to improving future treatments and outcomes in patients with DED [9].

Conventional methods of assessing patient experience utilise surveys and questionnaires in different research settings (at home, online, at a doctor’s office, through patient groups, etc.) [10]. The emergence of digital electronic devices and social media platforms has significantly altered the healthcare landscape and healthcare knowledge exchange in countries with high internet penetration [11–13]. Social media acts simultaneously as a platform to obtain disease-related information, identify and access healthcare resources, network with fellow patients, and communicate problems and experiences online [11–14]. Therefore, social media platforms provide a window to patients’ perceptions of their diseases, treatment, satisfaction with outcomes, and other factors affecting patient lives.

Social media listening (SML) is a new approach to harness information derived from social media platforms and generate insights into users’ experiences. It has been employed to monitor and analyse discussions on health-related topics in diverse diseases [15–20]. To date, there is no published literature on the use of SML to investigate the needs and experiences of patients with DED. The present study explores SML as a research tool to provide insights on disease burden, diagnosis, treatment patterns and QoL in patients with DED.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

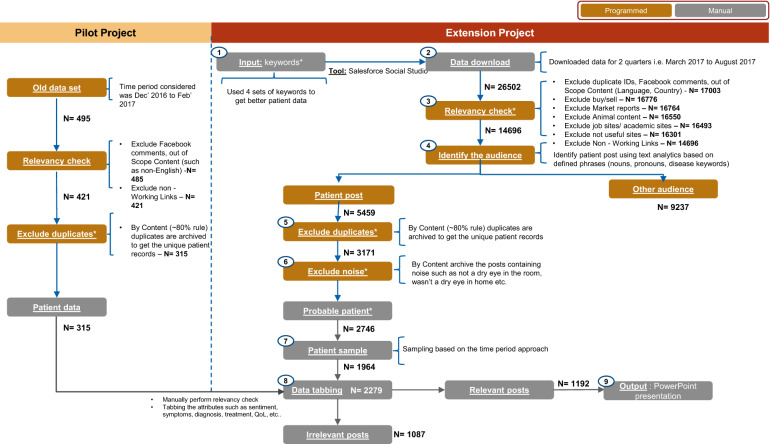

A comprehensive search was performed on the social media platforms (Twitter, blogs, news and forums providing public access to information/posts) for English-language content posted online between December 2016 and August 2017. Social media platforms, like Facebook, which did not provide public access to information/posts were excluded. The resulting search output was evaluated for DED-related posts using the following predefined search terms: dry eye OR dry eye disease OR dry eye syndrome OR dysfunctional tear syndrome OR meibomian gland disease OR meibomian gland dysfunction. These keywords for DED were combined with other search terms related to the symptoms, diagnosis and medications (Supplementary Table 1). Social media posts in English language from the United States (USA), United Kingdom (UK), France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Canada, Australia and Japan were retrieved using the Social Studio® platform (Salesforce.com, USA). A pilot phase of the study was carried out resulting in 315 patient posts. A further extension of the study was subsequently carried out, resulting in the final cumulative output of posts used for analyses in the current study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of post selection and tagging. N = no. of posts remaining after each step. Includes posts by Twitter handles of various clinics, university research groups, eye care awareness group, charities, etc.

Selection of Posts and Text Data Cleaning

Social Studio® is an online aggregator tool that provides downloadable links of posts from social media channels (Supplementary Table 3) based on specific keywords, with time stamp and geographic location of user. The Social Studio software we used utilizes the Rosette Language Identifier, enabling demanding text analytics applications whilst delivering high accuracy without sacrificing speed. It assigns a unique article ID for each downloadable link. These links were accessed to retrieve the content of the posts and the downloaded data were filtered and cleaned to remove duplicates (based on unique article ID and content snippet), irrelevant comments and out of scope content (e.g. general use of dry eye in a non-clinical sense, itch/pain with reference to conditions other than dry eye, etc.). Posts containing data from social media websites outside the scope of this study, aggregator or junk websites (i.e. websites leading to unsolicited advertisements, or unrelated misleading links), links that are not publicly accessible or not working, content pertaining to buying or selling drugs, market reports from pharmaceutical companies or e-retailers and posts by pharmacies were removed (Fig. 1). Only English-language posts were considered for the study. Spelling correction was applied to the extent possible while evaluating the content of the post; it might have been possible that content was missed during search because of incorrect spelling in the posts not matching with the search terms used.

For the purpose of this study, a user refers to an individual who posted the content on social media. A unique record pertains to a unique individual (patient, caregiver), identifiable by the same content, even if their posts have a different time stamp. A post was defined as social media content with a defined article ID. Thus, each user has a record which cumulatively consists of one or several user posts on social media. A mention indicates the number of times a symptom, treatment, diagnostic test or other parameter is mentioned in each record. As each record may contain one or more posts by a user, the number of mentions is independent of the number of posts.

Categorisation and Indexing of Social Media Posts

Using natural language processing (NLP) the downloaded links were further indexed using patient lexicon and disease-related keywords to arrive at a sample set of possible patient records. Relevancy check of the extracted social media posts followed a two-step process. The first step included NLP to identify the relevancy and then a manual evaluation of the posts identified as relevant through NLP. Gender, age and other demographic information about users was recorded when available or when it was possible for the information to be inferred from the message content or categorised as unknown. The posts were classified as being reported by patients (e.g. in case of direct reference to a ‘self’ within the content, without references to other subjects, was qualified as patient-reported insights) or caregivers, where this could be determined on the basis of analysis of content and posts with no first-person references but mention of a relation like husband, wife, son, daughter etc. Final analysis of all relevant posts was conducted manually to generate patient insights. All manual tagging and analyses of posts followed a four-level hierarchy of decision-making, starting from level 1 (self review), level 2 (peer review done by peer analysts), level 3 (senior analyst review) and level 4 (team review), thus ensuring outcome of manual analyses followed a robust model of consensus-based analysis and tagging of posts.

The key themes identified included causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatments and comorbidities associated with DED, and disease management. Posts were further analysed for the ‘number of mentions’ of a particular theme in the posts. Posts with a mention of DED severity were used to provide a qualitative description of the patients’ self-reported experience of the disease. The impact of DED on patients’ QoL was analysed using posts describing work productivity loss or inefficiency and problems in performing activities of daily living. Whilst more than one mention of a theme was counted once only, mention of other management strategies was counted separately, thus leading to the number of mentions sometimes being in excess of the number of posts obtained. For example, ‘management’ could result in more than one theme mention within a single post, e.g. drug management of the disease. As an example is the following:

Of course my insurance company denied any coverage for Xiidra. They said I needed a trial of Restasis. After they gave authorization, I tried Restasis for one month. I was miserable. No eyelove for me. I was back to sticking eyelids in the AM, burning sensation all day from Restasis. Back to constant use of tears solutions. I went back to my doc, and it was clear that I failed Restasis. Thankfully, I got a 6 month approval for Xiidra. As soon as I started back on Xiidra, I felt great again. No more dry eye symptoms. Just nasty bitter taste in my throat

There is a mention of two different management options (Xiidra® and Restasis®), including the outcomes, and thus this counts as two different mentions: one for Xiidra® and one for Restasis®. However, as the number of mentions for each of the key themes was different, and it was not clear if a comparable sample had expressed the specific themes in their posts, each theme should be interpreted as a standalone outcome. No correlation across the outcomes of these analyses is possible in the current study.

Ethical Considerations

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. All online content was anonymised and is in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) search strategy and data collection. Approval was obtained from Novartis Social Media Council, the governing body which holds oversight on the use of social media by Novartis. All relevant local and global laws affecting and relating to the use of social media were aligned with and as reflected in Novartis processes were followed in the conduct of the current study. The authors of this manuscript consent to the publication of the submitted manuscript and declare that no individual patient data requiring consent has been presented.

Data Analysis

All data were analysed using descriptive statistics and are presented as numbers of posts, number of mentions or percentages. All posts were analysed by (1) social media channels (Twitter, forums, blogs and news), (2) countries (USA, Germany, Italy, UK, France, Spain, Australia and Japan), (3) tones (positive, neutral and negative) and (4) key themes of discussion.

Results

Characteristics of Analysed Posts

A total of 26,502 outputs were initially extracted from social media platforms using DED-related keywords during the study period. In all, 2279 possible patient records were identified by NLP which automates the process of generating unique patient posts. The 2279 posts were then filtered for relevance to the disease area by analysts on the basis of manually identifying the content which explicitly stated information about DED. A total of 1192 posts determined to be written by patients or caregivers were thus identified and included for further analysis. Figure 1 summarises the filtering of posts. Most posts were by patients (99%; 1191/1192), and just one by a patient’s caregiver. The information on gender could be discerned in 130 posts, and 68% (89/130) of posts were by female and 32% (41/130) by male patients. Where age could be discerned, 39% (26/67) of patients were aged between 21 and 30 years, 12% (8/67) between 31 and 40 years, and 22% between 41 and 50 years (15/67). Forums were the primary source of information, contributing to 69% of the total posts, followed by Twitter (29%). A detailed list of domains from where the posts were obtained has been provided in Supplementary Table 3. Most of the social media posts were from the USA (77%) or the UK (21%) (Supplementary Table 2).

Key Themes of Discussion

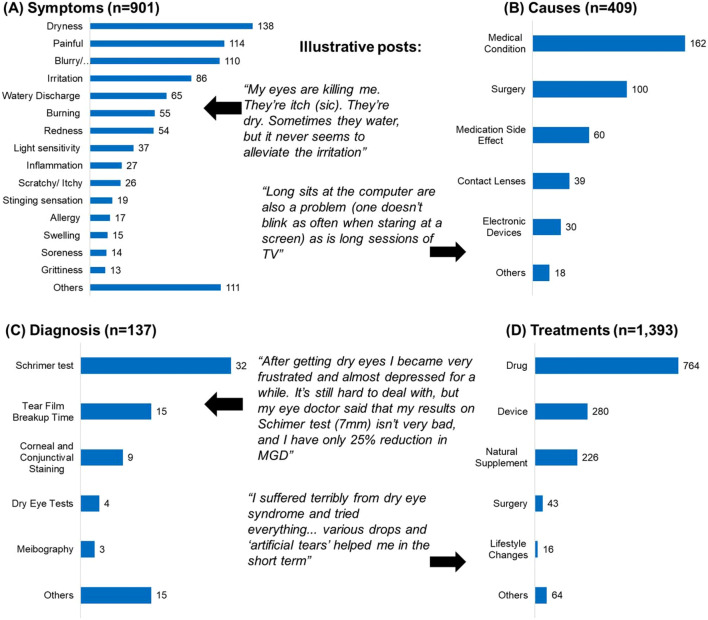

The key themes of discussion in the posts were management (number of mentions, 1393), symptoms (901), causes (409), diagnosis (137) and associated comorbidities (187). The most common symptoms mentioned in the posts were eye dryness, pain and blurry vision. There were 409 mentions for the causes of dry eye, of which 40% mentioned the underlying medical conditions (e.g. Sjögren’s syndrome, blepharitis, vitamin D deficiency and autoimmune conditions), 24% mentioned surgery (e.g. undergoing laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis, cataract surgery, photorefractive keratectomy laser surgery, radial keratotomy) and 15% mentioned side effects of medications (e.g. contraceptives, antihistamines, blood pressure medication, isotretinoin, cancer medication) (Fig. 2). DED-associated comorbidities were a less frequently discussed theme—there were 187 mentions of comorbidities with eye diseases (34%), autoimmune conditions (13%), thyroid disorders (7%) and diabetes (6%) being the common comorbidities. Multiple diagnostic methods were mentioned as being available, but the Schirmer test and tear film break-up time were the most mentioned ones (Fig. 2). Pharmaceutical drugs were mentioned as the major treatment option for managing dry eye symptoms (55% of 1393 treatment-related mentions), followed by devices (warm compresses, punctal plugs, scleral lens etc.). Of the pharmaceutical drugs, patients most often mention using eye drops; artificial tears as over-the-counter (OTC) drugs appear the first treatment option; about 17% of mentions related to prescription drugs. Patients are also actively discussing natural supplements as an alternative approach for treating dry eye symptoms.

Fig. 2.

Major themes of discussion on social media by the number of mentions in the posts

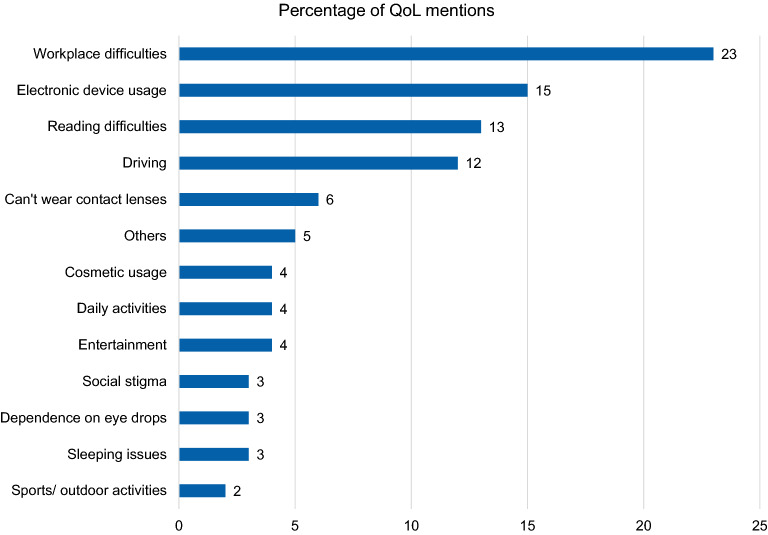

Impact of DED on Patients’ QoL

There were 224 posts by patients which were ascertained to describe their QoL (Fig. 3). Dry eye was stated to significantly impact patients’ QoL, limiting the activities of daily routine, commute/driving and use of electronic devices. Overall, DED greatly affected patient psychological well-being, as illustrated through the patient quotes in Fig. 4. Of the QoL quotes, nearly one quarter (51/224) spoke of workplace difficulties (see Table 1 for themes and some example quotes). Of the 51 mentions related to workplace difficulties, 48 had a negative mention (Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Impact of dry eye on patients’ quality of life. All percentages were calculated for a total number N = 224; QoL health-related quality of life

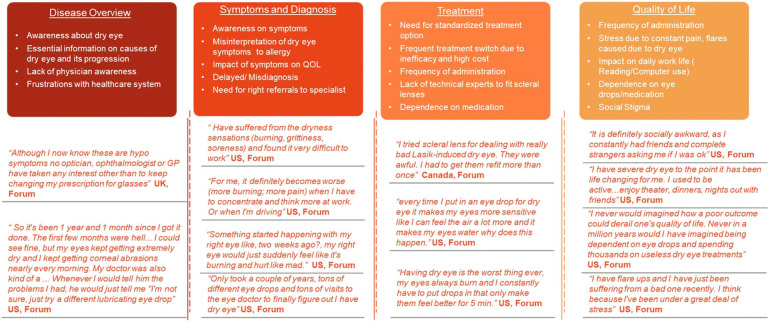

Fig. 4.

Patients’ perspectives on dry eye disease: broad themes and representative patient posts

Table 1.

Impact of DED on quality of life

| Theme (number of mentions) | Perception | Specific aspect of theme mentioned in post | Number of mentions | Sample quote |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workplace difficulties (n = 51) | Positive: 1; Neutral: 2; Negative: 48 | Can’t work on computer | 10 |

“I couldn’t see through the heavy tear production & stopped working, as a film maker” “I also spent thousands on my eye treatments last year alone, which I can’t do if I don’t work, but I can’t work when I feel like this” |

| Can’t keep up with work | 9 | |||

| Can’t focus on work | 9 | |||

| Stopped working | 7 | |||

| Skip/can’t work full time | 6 | |||

| Trouble finding job | 5 | |||

| Make working easy | 2 | |||

| Change work | 2 | |||

| Retired early | 1 | |||

| Electronic device usage (n = 33) | Positive: 4; Neutral: 2; Negative: 27 | Eye strain | 11 | “My vision is so blurry now I have to get about 5 inches from the screen to see what is there. Magnification does not help much as the lighted screen “ghost” whatever I am seeing. My friend is typing/sending this for me now” |

| Unable to use | 9 | |||

| Able to use | 5 | |||

| Less blinking | 4 | |||

| Difficulty in reading | 2 | |||

| Blurry vision | 2 | |||

| Reading difficulties (n = 29) | Positive: 3; Neutral: 1; Negative: 25 | Can’t read | 10 | “I had them reset my ‘reader’ for my lap and rest the book on a small pillow because of hand osteoarthritis, 2.5 yrs. ago I had to go to Kindle and blow up the fonts to the biggest fuzzy stuff I could get” |

| Able to read | 4 | |||

| Burn while reading | 4 | |||

| Small prints | 4 | |||

| Difficulty in reading | 3 | |||

| Blur while reading | 2 | |||

| Driving difficulties (n = 26) | Positive: 3; Neutral: 2; Negative: 21 | Difficulty in driving | 6 | “I can no longer drive at night. The halos and starbursts around lights are huge and disorienting. So I have to make sure I am home before the sun sets. My eyes are horribly dry” |

| Can’t see while driving | 6 | |||

| Stopped driving | 4 | |||

| Night driving difficult | 3 | |||

| Able to drive | 3 | |||

| Trouble concentrating | 3 | |||

| Reduced driving | 1 | |||

| Can’t wear contact lenses (n = 13) | Positive: 2; Neutral: 2; Negative: 9 | Stopped use | 7 | “The worst part with this for me (I know I probably sound superficial) have been to completely cut off wearing contact lenses and makeup” |

| Wish to start | 5 | |||

| Occasional use | 1 | |||

| Entertainment (n = 10) | Positive: 3; Negative: 7 | Can’t watch movie/TV | 7 | “I have severe dry eye to the point it has been life changing for me. I used to be active…enjoy theater, dinners, nights out with friends” |

| Can watch movie/TV | 4 | |||

| Social stigma (n = 7) | Positive: 1; Negative: 6 | Social awkwardness | 4 | “It is definitely socially awkward, as I constantly had friends and complete strangers asking me if I was OK” |

| Miss social events | 2 | |||

| Can’t go out in public | 1 |

Everyday activities like driving, reading and wearing contact lenses had some of the highest proportions of negative mentions. However, the overlap of these mentions with the potential impact of this impairment on patients’ QoL demonstrates the interrelationship between clinical symptoms and QoL.

Patients’ Perspectives on Unmet Needs

Patients’ perceptions of unmet needs were assigned under four broad categories: disease, symptoms and diagnosis, treatment and QoL. A summary of patient perception of unmet need is presented in Fig. 4. Patients mentioned a lack of awareness about DED and insufficient access to essential information about the disease as the key unmet needs relating to the disease. This correlated with delayed diagnosis/misdiagnosis after presentation of initial symptoms also being mentioned as an important factor.

Patients seem to recognise the value of timely referral to specialists, and the need for physician awareness of DED is identified as a key need. Moreover, patients perceive that, despite the availability of symptomatic treatments, there is no available treatment providing lasting relief. The relative lack of efficacy and frequent treatment switches due to inefficacy are illustrated by the quotes provided in Fig. 4.

Discussion

The current study attempts to utilize substantive data from social media platforms, and apply it to understanding patient issues related to living with DED. This is the first study to use an SML approach to analyse disease burden and patients’ perspectives on DED, and provides a view of the significant impact of DED on patients’ daily activities, work and driving. The results illustrate how lack of expertise for proper diagnosis, a dearth of effective treatment options and the need to increase awareness of DED among patients are the key unmet needs.

Social media interactions present an inherent opportunity to obtain unfiltered, clear, first- or near-person narratives of patients’ experiences of living with disease conditions and the effectiveness of their treatment. SML has been used as a tool to investigate patient perceptions in different indications, including multiple sclerosis [15], cancer screening [16], human immune virus [17], inflammatory bowel disease [18], Zika virus [19] and total joint arthroplasty [20]. Emerging communication media have been used in different academic disciplines to assess perspectives and views of their users on health issues and interventions [21–24]. Insights derived from such online conversations can be a crucial resource in enriching treatment outcomes associated with chronic disease conditions.

NLP has been widely used in SML studies, and the resulting data has been reported for a variety of diseases. The use of NLP-based surveillance has especially been studied for its effectiveness in post-marketing safety surveillance. These studies assessed the effectiveness of NLP-based surveillance ranging from signal detection to identifying individual case safety reports from social media. This is especially true in the case of hybrid models where NLP is paired with manual assessment to arrive at a search strategy that optimizes the processing throughput possible with NLP-based surveillance, combined with the specificity and accuracy of manual assessment.

In the current study, NLP (itself well characterized as being effective in SML) has been used for its high-throughput capability, which was then paired with manual assessment to provide the necessary focus and specificity of the outputs. As a tool for such SML studies, it can be surmised that certain pertinent posts might have been excluded by this approach; however, it is unlikely that any non-specific posts will be included. Thus, errors of exclusion may impact the strength of the signal identified, but the proportion of “noise to signal” is relatively low, and hence the outcomes of this approach are considered to be robust. The SML approach used in the current study enriches our understanding of the issues, concerns and needs of DED patients, as expressed in social platforms, and complements the understanding from more conventional research approaches. Since the information is not being solicited through structured interviews, it allows a first-person authenticity in their described experiences. Potential bias inherent when using research questionnaires, interviews and other solicited sources of response-gathering has the potential to influence the research result outcome [25]. Being self-described, social media posts can therefore complement insights from traditional survey-based studies to posit a more complete picture of patient experiences with DED.

The insights from the present study are a valuable addition to existing literature on DED patient experiences. However, they must be interpreted in the context of key limitations imposed by the nature of the study and the data obtained from it. Firstly, a majority of the posts were from the USA, and the findings may not be generalised across all geographies. Secondly, expression of patient perceptions may be a function of how motivated they are to use social media. Negative perceptions may be vocalised more often than positive perceptions/experiences. That said, the broad agreement of trends from this study with those from previous survey-based studies is an indicator of the validity of the information derived from social media. Lastly, inherent biases which may affect accuracy (representation of collected sample, linguistic selection in posts), reliability (consistency of reports from individual patients across time points or descriptors) and quality of information (self-selection bias) from any social media platform may be operative in the current study as well [26].

In the present study, one of the key themes was an expression of need for better medications due to patients’ frustration with relief offered by current available medications. Patient satisfaction associated with current dry eye medications, and with symptom control, is low [27]. Thus, there may be some disconnect between clinical assessment of “effectiveness” and patients’ perception of “relief” associated with current medications use. Patient- and physician-reported assessments of DED severity often diverge and, despite reports of patient experience being positively associated with clinical effectiveness, contrary reports of patient experience often being not in concordance with clinical assessments also exist [28, 29]. The fact that symptoms, causes and especially treatments of DED are most frequently discussed in the context of their impact on patients’ lives in the current study, points to the practical concerns that are most bothersome to patients; these may differ from clinical measures of improvement. This is suggestive of the need for current DED treatment paradigms to include qualitative aspects of patient experience to build a patient-centric model of DED management.

Two broad aspects of patient experience that the current study identify are impairment of QoL and patient perceptions of unmet needs. Almost one in four DED patients who contributed posts online describe impaired QoL in terms of workplace difficulties. It has been previously reported that people with DED are 2–3 times more likely to experience difficulties with daily activities such as reading, computer use, watching television, performing professional work and day- or night-time driving [30]. In a survey from five European countries, 31% of patients perceived DED as a ‘disease’ and in some cases even a ‘handicap’ [31]. In a cohort study from China, when vision-related QoL in outpatients with DED was compared to the general population, patients with DED had statistically significantly higher scores measuring the impact on ‘mental health’, ‘role difficulties’, ‘dependency’ and ‘driving’ subscales as well as in the composite score [32]. Impairments in QoL due to moderate and severe dry eye are similar to reports for moderate and more severe (class III/IV) angina, respectively, when measured for utility assessment (preference by patients for a specified condition) [33]. The high patient burden of DED consequently translates into a significant economic burden on both the individual and healthcare system—the annual overall burden of DED on the health care system in the USA was estimated at USD3.84 billion and per patient at USD771 and USD1267 for patients with moderate and severe DED, respectively, in 2011 [7, 34]. The cumulative impact of the QoL impairment and cost burden is that DED patients report a lack of optimism about the outlook for their condition in the long term [35].

The articulation of issues influencing patients’ QoL in social media posts provides a basis for increasing awareness of, and developing management strategies for those underlying unmet needs. A common theme amongst patients’ posts was the delay in diagnosis of DED, which resulted in multiple visits to physicians’ offices, and suboptimal management of DED symptoms. An online survey of DED patients concluded that delayed diagnosis and high frequency of treatment use are associated with negative patient perception of DED [31]. Additionally, even after being diagnosed with DED, patients appear to perceive the lack of desired efficacy as an unmet need in the current study. In a previous questionnaire-based survey of 4000 participants, at least 15–20% of participants reported being either somewhat or extremely dissatisfied with the duration for which the treatment worked [35]. Nearly 40% of all patients reported either being dissatisfied or unaffected by the duration of efficacy of their treatment [36]. Despite being one of the most common clinical complaints, fundamental issues like timely diagnosis and efficacious treatment seem to be the most voiced unmet needs in DED.

Conclusions

DED imposes a significant burden of impaired QoL in patients that spans multiple aspects of daily life. This appears to manifest itself in terms of both a requirement for more efficacious treatment options and also improvements in the education, diagnosis and management of the disease. The insights revealed using SML data strengthen our understanding of patient experiences and their unmet needs in DED. This study illustrates that an SML approach contributed effectively in generating patient insights, which can be utilised to inform decision-making and strategy in drug development. Harnessing the synergy between data from new digital media platforms and conventional channels of patient insight generation is important to build a patient-centric model of DED care.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Brigitte Sloesen, Stefano Dal Santo, Sushant Anand and Cheshta Bhatia for their contributions to this study.

Funding

The study and article processing charges were funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Editorial Assistance

The authors acknowledge K M Ashwini Kumar (Novartis Healthcare Pvt Ltd, India) for editorial and writing support, in accordance with the Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authors’ Contributions

NC, AM, CP and SM contributed to the conception of the study design. NT and JK contributed to the conduct of study and data collection. Data analysis and interpretation was performed by JK and NT, along with other authors. The manuscript was written by RG, along with NC and AM. All authors reviewed the manuscript critically and provided final approval for submission.

Disclosures

Nigel Cook is a full-time employee of Novartis group of companies and declares that he has no competing interests. Anmol Mullins was a full-time employee of Novartis group of companies at the time of the study and declares that she has no competing interests. Raju Gautam is a full-time employee of Novartis group of companies and declares that he has no competing interests. Sharath Medi is a full-time employee of Novartis group of companies and declares that he has no competing interests. Clementine Prince was a full-time employee of Novartis group of companies at the time of the study and declares that she has no competing interests. Nishith Tyagi is a full-time employee of Novartis group of companies and declares that he has no competing interests. Jyothi Kommineni is a full-time employee of Novartis group of companies and declares that he has no competing interests.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. All online content was anonymised and is in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) search strategy and data collection. Approval was obtained from Novartis Social Media Council, the governing body which holds oversight on the use of social media by Novartis. All relevant local and global laws affecting and relating to the use of social media were aligned with and as reflected in Novartis processes were followed in the conduct of the current study. The authors of this manuscript consent to the publication of the submitted manuscript and declare that no individual patient data requiring consent has been presented.

Data Availability

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article and the associated supplementary material.

Footnotes

Enhanced digital features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.8108912.

References

- 1.Craig JP, et al. TFOS DEWS II report executive summary. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(4):802–812. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stapleton F, et al. The epidemiology of dry eye disease. In: Chan C, editor. Dry eye: a practical approach. Essentials in ophthalmology. Berlin: Springer; 2015. pp. 21–9.

- 3.Farrand KF, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed dry eye disease in the united states among adults aged 18 years and older. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;182:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hauser W. Dry eye: a young person’s disease? Review of optometry. Feb 15, 2017. https://www.reviewofoptometry.com/article/dry-eye-a-young-persons-disease. Accessed Jan 31, 2019.

- 5.NHS. Dry eye syndrome. 2016. http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Dry-eye-syndrome/Pages/Introduction.aspx. Accessed Jan 31, 2019.

- 6.Messmer EM. The pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of dry eye disease. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112(5):71–81 (quiz 82). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.McDonald M, et al. Economic and humanistic burden of dry eye disease in Europe, North America, and Asia: a systematic literature review. Ocul Surf. 2016;14(2):144–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uchino M, Schaumberg DA. Dry eye disease: impact on quality of life and vision. Curr Ophthalmol Rep. 2013;1(2):51–57. doi: 10.1007/s40135-013-0009-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barabino S, Labetoulle M, Rolando M, Messmer EM. Understanding symptoms and quality of life in patients with dry eye syndrome. Ocul Surf. 2016;14(3):365–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garratt A, Solheim E, Danielsen K. National and cross-national surveys of patient experiences: a structured review [Internet]. Oslo, Norway: Knowledge Centre for the Health Services at The Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH); 2008. [PubMed]

- 11.Pew Research Center. Social media usage: 2005–2015. 2015. http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/10/08/social-networking-usage-2005-2015/. Accessed Jan 31, 2019.

- 12.Pew Research Center. Health online 2013. 2013. http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/01/15/health-online-2013/. Accessed Jan 31, 2019.

- 13.European Commission. Europeans becoming enthusiatic users of online health information. 2014. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/europeans-becoming-enthusiastic-users-online-health-information. Accessed Jan 31, 2019.

- 14.Antheunis ML, Tates K, Nieboer TE. Patients’ and health professionals’ use of social media in health care: motives, barriers and expectations. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(3):426–431. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Risson V, et al. Patterns of treatment switching in multiple sclerosis therapies in US patients active on social media: application of social media content analysis to health outcomes research. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(3):e62. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metwally O, et al. Using social media to characterize public sentiment toward medical interventions commonly used for cancer screening: an observational study. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(6):e200. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill BS, et al. Leveraging social media to explore black women’s perspectives on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2018;29(1):107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez B, et al. Patient understanding of the risks and benefits of biologic therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: insights from a large-scale analysis of social media platforms. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(7):1057–1064. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller M, et al. What are people tweeting about Zika? An exploratory study concerning its symptoms, treatment, transmission, and prevention. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2017;3(2):e38. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.7157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramkumar PN, et al. Social media and total joint arthroplasty: an analysis of patient utilization on instagram. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(9):2694–2700. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magro MJ. A review of social media use in e-government. Adm Sci. 2012;2:148–161. doi: 10.3390/admsci2020148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farrell LC, Warin MJ, Moore VM, Street JM. Emotion in obesity discourse: understanding public attitudes towards regulations for obesity prevention. Sociol Health Illn. 2015;38:543–558. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giles E, Holmes M, McColl E, Sniehotta FF, Adams JM. Acceptability of financial incentives for breastfeeding: thematic analysis of readers’ comments to UK online news reports. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2015;15:1. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0549-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Street JM, Hennessy SE, Watt AM, Hiller JE, Elshaug AG. News and social media: windows into community perspectives on disinvestment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2011;7:376–383. doi: 10.1017/S026646231100033X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi BC, Pak AW. A catalog of biases in questionnaires. Prev Chron Dis. 2005;2(1):A13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nichols KK, Bacharach J, Holland E, et al. Impact of dry eye disease on work productivity, and patients’ satisfaction with over-the-counter dry eye treatments. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(7):2975–2982. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alshaikh F, Ramzan F, Rawaf S, Majeed A. Social network sites as a mode to collect health data: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(7):e171. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yeh PT, Chien HC, Ng K, et al. Concordance between patient and clinician assessment of dry eye severity and treatment response in Taiwan. Cornea. 2015;34(5):500–505. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chalmers RL, Begley CG, Edrington T, et al. The agreement between self-assessment and clinician assessment of dry eye severity. Cornea. 2005;24(7):804–810. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000154410.99691.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miljanovic B, et al. Impact of dry eye syndrome on vision-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(3):409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.11.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Labetoulle M, Rolando M, Baudouin C, van Setten G. Patients’ perception of DED and its relation with time to diagnosis and quality of life: an international and multilingual survey. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101(8):1100–1105. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-309193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Le Q, Ge L, Li M, et al. Comparison on the vision-related quality of life between outpatients and general population with dry eye syndrome. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014;92(2):e124–e132. doi: 10.1111/aos.12204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schiffman RM, Walt JG, Jacobsen G, Doyle JJ, Lebovics G, Sumner W. Utility assessment among patients with dry eye disease. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(7):1412–1419. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00462-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu J, Asche CV, Fairchild CJ. The economic burden of dry eye disease in the United States: a decision tree analysis. Cornea. 2011;30(4):379–387. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181f7f363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crnej A, Kheirkhah A, Ren A, et al. Patients’ perspectives on their dry eye disease. Ocul Surf. 2016;14(4):440–446. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaumberg DA, Uchino M, Christen WG, Semba RD, Buring JE, Li JZ. Patient reported differences in dry eye disease between men and women: impact, management, and patient satisfaction. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e76121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article and the associated supplementary material.