Abstract

Geriatric low back pain (LBP) can have a profound impact on physical activity and can cause a decline in physical function, which is a major health risk for older adults. Within the last decade, physical therapist management of LBP has shifted from an emphasis on pathoanatomical mechanisms, such as spine degeneration, to addressing psychological distress factors. Although this approach is promising, the complexity of LBP in older adults (including biological, psychological, cognitive, and social influences), which may differ from that in younger adults, must be considered. Further, outcome assessment should represent not only the LBP experience (eg, pain intensity, pain with movement) but also LBP consequences, such as physical activity decline and physical function decline. This perspective discusses influences on geriatric LBP, experiences, and consequences with the goal of facilitating standardized and comprehensive physical therapist management.

Geriatric low back pain (LBP) is the global leader in musculoskeletal disability for older adults, eclipsing other age-related conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, and osteoarthritis (OA).1 For almost 40 years, the mechanistic model of geriatric LBP has been pathoanatomical spine degeneration. However, spinal degeneration is highly prevalent with age and weakly associated with pain intensity.2,3 Moreover, care pathways that involve diagnostic imaging for spinal degeneration increase the likelihood of invasive interventions, incur higher treatment costs, and yield no better outcomes.4

In 2011, PTJ’s Special Issue on Psychologically Informed Practice helped shift emphasis from spinal pathoanatomy to addressing pain-related beliefs and attitudes.5 For physical therapists, the result was greater understanding of associations between psychological distress and persistent pain, and subsequent incorporation of psychologically informed practice into LBP management. A caveat, however, is that associations between psychological distress and persistent pain change across the life span, and such changes could have implications for geriatric LBP management. In addition, older adults undergo age-related senescence to multiple body systems,6–8 which not only increases the susceptibility to persistent pain, but also presents a cadre of management targets and barriers different from younger adults.

Moreover, compared with younger adults, LBP consequences for older adults may be greater. Like most musculoskeletal pain conditions, movement-evoked pain is a staple of LBP and can facilitate physical activity compensation and/or avoidance. However, older adults are already at risk for sedentary behavior9; therefore, further physical activity avoidance during geriatric LBP increases the likelihood for long-term consequences—mainly physical function decline.10 The established associations among physical function decline, comorbid conditions,11 and mortality12,13 are reminders that geriatric LBP may indirectly pose health risks above and beyond the pain experience. Therefore, physical therapists should consider expanding geriatric LBP outcome measurement to encompass pain, movement, physical activity, and physical function.

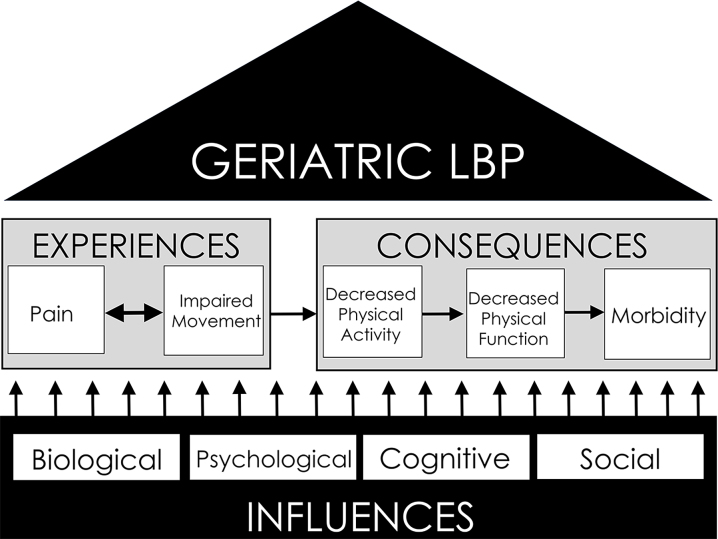

This perspective will outline geriatric LBP in the context of influences, experiences, and consequences (Figure); with the aim of promoting a more standardized and comprehensive physical therapy approach to geriatric LBP management. The first objective is to provide current understanding of potential age-related biological, psychological, cognitive, and social influences on geriatric LBP. Second, we will outline measurement tools and appropriate evidence-based interventions for influences on geriatric LBP. Finally, we will propose an expansion of geriatric LBP outcomes to adequately represent both geriatric LBP experiences and consequences. In addition to recall questionnaires of pain intensity and pain-related disability, we suggest the use of clinical performance measures to assess movement, pain with movement, physical activity, and physical function. The long-term goals of this perspective are to optimize the effectiveness of geriatric LBP management and mitigate long-term health consequences associated with geriatric LBP.

Figure.

Foundation and structure of geriatric low back pain (LBP). Geriatric LBP experiences and consequences are founded upon biological, psychological, cognitive, and social influences. Experiences include not only pain but also the interface of pain with movement. Consequently, pain with movement can induce decreases in physical activity, which invoke the negative health cascade of physical function decline and subsequent morbidity.

Influences on Geriatric LBP

Biological Influences

Biological aging

Older adults are susceptible to age-related changes to body systems. Importantly, individuals of the same chronological age can have distinctly different biological ages, meaning that the body systems of 1 individual can be older than those of another.14 That said, 2 key systems which consistently change and are highly important to consider when managing geriatric LBP are the pain neuroprocessing system and the muscular system.

The pain system undergoes widespread age-related senescence that affects how older adults perceive and process pain, including an altered opioid system, loss of nociceptive afferent fibers, and altered activity of neurotransmitters.6 Although much of this work has been performed in animal models, recent psychometric studies reveal an age-related delay in pain perception.6,7 In addition, the elderly pain neuroprocessing system also demonstrates maladaptive responses to prolonged pain over time. Using experimental paradigms to test spinal and supraspinal pain facilitation, older adults reported higher, increasing pain intensity despite experiencing an unchanging heat pain stimulus; while younger adults demonstrated lower, decreasing pain intensity.7 Using similar experimental pain methods, older adults had a decrement in their ability to inhibit pain once it is present.15 Importantly, maladaptive pain responses are not confined to a particular injury region or pain tracts in the central nervous system. For example, older adults react to pain with a faster and longer release of circulating substance P—a neuropeptide associated with pain and inflammation—than do younger adults.16 Collectively, these findings suggest age-related senescent changes in pain neuroprocessing system, which may predispose older adults to pain persistence.

Similar to the pain processing system, the muscular system also undergoes deleterious age-related changes. Sarcopenia is traditionally defined as the age-associated loss of muscle mass and strength, although it has come to be associated not only with muscle atrophy but also with the deposition of fat within the muscle.17 Muscle atrophy and increased intramuscular fat infiltration are associated with negative functional sequelae in older adults, including disability, functional decline, and mortality.18 Recent work demonstrated that older adults with chronic LBP have higher levels of intramuscular fat in their multifidi than do age-matched peers without LBP as well as a smaller erector spinae muscle cross-sectional area.19 Further, Hicks et al20 demonstrated that increased intramuscular fat in the trunk muscles of older adults is associated with greater LBP intensity and worse functional performance; both cross-sectionally20 and longitudinally.10 A recent preliminary randomized clinical trial suggests that targeting the trunk muscles through a volitional trunk muscle training program augmented with neuromuscular electrical stimulation may lead to clinically meaningful improvements in pain, disability, and functional performance.21 Further longitudinal investigations into the role of the trunk muscles relative to geriatric LBP management are necessary.

Multimorbidity

Multimorbidity, or the coexistence of 2 or more health conditions, affects approximately one-quarter of older adults and increases the risk for health-related events.22 Here, we discuss key conditions that can influence both the patient's capacity to recover and the treatment plan. Importantly, the following factors are in addition to screening geriatric LBP red flags, such as fracture, osteoporosis, or thoracic pain.

Unlike current recommendations to deemphasize spinal pathoanatomy, hip degeneration in the presence of geriatric LBP should still be considered. A growing body of evidence points to hip degeneration as a potential key contributor to geriatric LBP symptoms. For example, approximately 50% of individuals with lower extremity OA also report LBP.23 Not only is hip degeneration highly prevalent in geriatric LBP, but research from the Delaware Spine Studies Cohort Study suggests that hip symptoms thought to be indicative of arthritis are associated with movement-evoked pain intensity, disability, poor physical performance, and worse health-related quality of life.24,25 Further, a recent epidemiologic study found older adults presenting to primary care with hip degeneration and new back pain had worse long-term disability, and worse quality of life outcomes than those with LBP but no hip degeneration.26

Older adults are susceptible to an increased number of painful body areas.27 Surprisingly, a large proportion of older adults experience widespread pain in at least 6 different anatomical areas.28 OA is often related to widespread pain in older adults, and much of the research in this area has been performed in patients with knee OA. The 3 key findings are that knee pain is predictive of widespread pain,29,30 that associations between knee pain and widespread pain are not based on OA-related structural changes,29,30 and that the association does not appear to be bidirectional, meaning that widespread pain does not lead to knee pain in people with knee OA.31 Although few studies have examined associations with geriatric LBP, widespread pain is generally a predictor for poor recovery from clinical care32 and must, therefore, be considered with geriatric LBP management.

The physiological pathway to activity limitation has not been well explored for people with pain. In the geriatric literature, Schrack et al33 proposed the Energetic Pathway to Mobility Loss framework. According to this framework, as a person ages, total energy capacity decreases while the energy cost of typical daily mobility increases; and, as a result, mobility limitations develop to prevent the energy cost of daily mobility from nearing the limits of the person's total energy capacity.33 In support of this framework, Schrack et al34 demonstrated that a higher energy cost of walking predicts walking speed decline in older adults but not in younger adults. Recently, Coyle et al35 capitalized on the Energetic Pathway to Mobility Loss framework and developed the Pain-Energy Model of Mobility Limitation. In essence, the Pain-Energy Model proposes that

The pain experience drives increases in the energy cost of mobility and decreases in energy capacity. As a result, functional mobility limitations develop to prevent energy cost from approaching energy capacity, thereby avoiding the risk of homeostatic collapse; however, the combined effects of both age and the pain experience result in even greater functional mobility limitations. Essentially, the pain experience accelerates the age-related decline of functional mobility.35

Moreover, pain in multiple forms in older adults, including hip pain,36 is associated with a greater energy cost during walking. The consistency of these findings might indicate that individuals with chronic LBP are at greater risk for mobility decline than their peers who are pain free, due to the elevated cost of everyday movement. It may be necessary to consider interventions focused on improving the energetic efficiency of daily mobility in older adults with chronic pain.

Psychological Influences

Pain catastrophizing and pain-related fear

The influence of psychological distress on persistent pain conditions is well established.37,38 A robust pain-related psychological factor is pain catastrophizing, whereby threats associated with a painful experience are ruminated, magnified, and lead to feelings of helplessness.39 Importantly, age may be a factor in pain catastrophizing scores, although so far findings have been mixed; some studies have shown lower scores for older adults, whereas others have shown scores to be unchanged across the life span.40–42 The influence of pain catastrophizing does appear to vary based on age, with middle adults having a stronger association between pain catastrophizing and pain-related emotions (eg, anxiety, sadness) and older adults having a stronger association with pain intensity.42 Further, a recent study by Somers et al43 found that in individuals with knee OA, pain catastrophizing was associated with pain, disability, and walking speed.

A second factor related to pain catastrophizing is pain-related fear, which is a vulnerability to pain that leads to subsequent avoidance of movement or activity.44 Unlike pain catastrophizing, pain-related fear is consistently lower in older adults than in younger and middle-aged adults.45–47 However, despite lower scores, pain-related fear is an important factor to consider when treating older adults with LBP, given its association to outcomes. Sions and Hicks48 found pain-related fear to be associated with an increased risk of falls. Cook et al45 found that in older adults but not in middle-aged adults, pain-related fear mediated associations between pain catastrophizing, depression, and disability. Finally, a recent meta-analysis found moderate to large associations between pain-related fear and disability, independent of age.49

Depressive symptoms

Like pain-related fear, depressive symptoms decrease with age.50 The magnitude of influence on pain in older adults is still in question, as some studies have reported stronger associations between depressive symptoms and pain,51–53 whereas others have reported weaker associations.45,46,54 However, a case-control study by Rudy et al55 found depressive symptoms to be a key factor in distinguishing older adults with LBP from those who are pain free. Further, a recent longitudinal study of older adults with hip or knee OA found that, while depressive symptoms did not influence OA symptoms, pain was found to contribute to depressive symptoms.56 Therefore, it is possible that depressive symptoms may be a consequence rather than a risk factor for persistent pain conditions in older adults. Because older adults with depressive symptoms are susceptible to other health conditions like cognitive impairment and increased falls risk,57,58 assessment of depressive symptoms should be routine during geriatric LBP management.

Reduced self-efficacy

Allthough the majority of studies on psychological influences of persistent pain pertain to negative affect constructs, such as pain catastrophizing or pain-related fear, research on positive affect constructs has grown significantly—particularly for age-related musculoskeletal conditions. One such factor is self-efficacy, which is an individual's confidence to perform tasks or exercises.59 Self-efficacy is believed to decline with age,60,61 suggesting that older adults have lower confidence in their functional abilities. In older adults with chronic pain, studies also have found self-efficacy to be positively associated with physical activity,62,63 and negatively associated with pain-related disability and depression.64 Further, in older adults with knee OA, greater self-efficacy has been associated with higher expectations for exercise.65 Perhaps the greatest endorsement for studying self-efficacy was a recent meta-analysis by Jackson et al,59 who found older adult samples to have stronger associations between self-efficacy and pain-related impairment than younger adults. The authors concluded that age is one of the strongest moderators of this association.

Cognitive Influences

A wealth of literature points to persistent pain being associated with reduced cognitive performance.66 In particular, working memory performance is decreased in individuals with chronic pain compared with healthy controls67 and is more strongly associated with movement-evoked pain than pain catastrophizing.68 Cognitive performance is particularly important when managing pain in older adults, as memory and executive function decline with age.69 A recent study by van der Leeuw et al70 observed that community-dwelling older adults with severe pain had poorer cognitive performance than those who were pain free. Importantly, pain interference—but not pain severity—was associated with reduced memory and executive function in the same cohort.70 Specific to geriatric LBP, Weiner et al71 found cognitive performance in older adults with geriatric LBP to be lower than that in older adults who were pain free and to be negatively associated with pain severity.

A limitation of most studies on cognitive performance and persistent pain in older adults is the use of questionnaires of recalled pain and/or function. However, a recent study of older adults with knee OA found those with higher pain severity and lower executive functioning had slower gait speed and impaired stair negotiation performance.72 Another limitation is that most studies have been cross-sectional, meaning that it is impossible to know the extent to which reduced cognitive performance leads to persistent pain (vs the more established notion that persistent pain leads to impaired cognitive performance). However, a seminal study by Attal et al73 in individuals with OA found that lower memory and executive functioning before surgery predicted pain persistence 12 months after surgery.

Social Influences

Positive patient-clinician interaction (ie, therapeutic alliance) has been associated with improved outcomes for persistent LBP.74 Recent work also suggests positive patient-clinician interaction in combination with nonpharmacologic treatment is associated with improved LBP outcomes.75 The problem is that older adults often face obstacles in patient-clinician interactions—such as age stereotypes and poor clinical understanding—that subsequently prevent optimal clinical care.76–79 Unfortunately, it is quite common for clinicians to attribute geriatric LBP to the inevitability of old age and/or to prescribe activity avoidance, which adversely affects patient outcomes.79 A qualitative study by Cayea et al80 found an alarming number of clinicians expressed low confidence in effectively treating geriatric LBP. A qualitative study by Makris et al81 identified multiple reasons why older adults with geriatric LBP avoid care; including negative attitudes toward pharmacologic and surgical interventions, and the belief that the priorities of their clinician do not align with their own priorities. Such scenarios increase the risk of older adults avoiding geriatric LBP care altogether.81

Measurement of Influences on Geriatric LBP

Biological Influences

For sarcopenia, physical therapists need to consider consequences to the primary muscular trunk stabilizers. Geriatric LBP measurement may include assessment of trunk muscle endurance, morphology, and function. Trunk muscle morphology and function may be assessed via ultrasound imaging studies in the clinical environment82,83; however, to capture intramuscular fat infiltration, magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography is needed. Although imaging studies are useful, they might not be feasible for most physical therapists to carry out in the clinic; therefore, trunk muscle endurance tests (extensors, flexors, and sidebridge84) are likely the best assessment tools. In fact, trunk extensor endurance, as measured by Suri et al,85 has been found to be reliable and predictive of balance and function in older adults.86(Tab. 1)

Table 1.

Implications and Measurement of Influences on Geriatric Low Back Pain (LBP).

| Influences | Age-Related Implications | Measurements Used |

|---|---|---|

| Biological | ||

| Maladaptive pain neuroprocessing | – Higher likelihood for pain persistence | – Quantitative Sensory Testing – Central Sensitization Inventory – painDETECT questionnaire |

| Sarcopenia | – Muscle atrophy of trunk stabilizers – Intramuscular fat infiltration |

– Muscle endurance testing – Diagnostic imaging |

| Hip pathoanatomy | – Referral to low back region – Poorer outcomes when coexisting with LBP |

– Measurement as described in current physical therapy hip and LBP clinical practice guidelines |

| Widespread pain | – Associations with poor recovery outcomes – Increased energy cost |

– Pain body diagrams |

| Energetic inefficiency | – Mobility limitations secondary to increased energy cost | – Cardiovascular endurance testing (eg, walk tests) |

| Psychological | ||

| Pain catastrophizing | – Similar to lower scores compared to younger adults – Associated with pain and function outcomes among older adults; less association with pain emotions |

– Pain Catastrophizing Scale |

| Pain-related fear | – Lower scores compared with younger adults – Associated with increased falls risk – Mediates association between pain catastrophizing and disability |

– Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire – Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia |

| Depressive symptoms | – Lower scores compared with younger adults – Potential consequence of persistent pain |

– Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale – Geriatric Depression Scale |

| Reduced pain self-efficacy | – Lower scores compared with younger adults – Stronger association with pain and function outcomes compared with younger adults |

– Chronic Diseases Self-Efficacy Scale – Chronic Pain Self-Efficacy Scale |

| Cognitive | ||

| Reduced memory and executive function | – Age-related decline in memory and executive function – Poorer cognitive performance associated with higher pain severity |

– Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| Social | ||

| Suboptimal medical interaction | – Lower medical provider confidence to effectively treat LBP – Prescription of activity-avoidance vs facilitation – Discordant patient vs provider goals |

– Expanded communication – Shared goal development |

Senescent changes in pain neuroprocessing, which predispose older adults to pain persistence and widespread pain, can be assessed with similar quantitative sensory tests used in research—although clinical assessment is limited to static measures, such as pressure algometry (which only assesses the pain threshold). Lower pressure pain threshold would suggest higher pain sensitivity either to a specific region (eg, low back) or diffusely (ie, widespread pain), and indirectly indicates altered pain neuroprocessing. Alternatively, patient-reported outcome measures such as the Central Sensitization Inventory or the painDETECT Questionnaire might be used. The Central Sensitization Inventory is a 101-point questionnaire designed to inform clinicians of altered pain neuroprocessing and the presence of widespread pain conditions.87 Similarly, the painDETECT Questionnaire was designed to assess neuropathic components of LBP88; in addition, it was found to correlate with altered pain processing in older adults with knee OA.89 Finally, clinicians can use pain body diagrams to determine the presence of widespread pain in older adults with geriatric LBP.

Hip involvement in LBP is not novel, as Offierski and MacNab90 first proposed the relationship over 30 years ago. For reference, both hip measurement and management strategies are extensively covered by current hip and LBP clinical practice guidelines for physical therapists.91,92

If there are concerns regarding energetic efficiency, clinicians should evaluate both the total energetic capacity of the patient (ie, VO2 assessment or an endurance-focused performance test) and any potential impairments that are reducing efficiency. For example, recent work from Hicks et al93 found that increased step width and double limb support time are problematic gait characteristics in older adults with chronic LBP, and Wert et al94 found that increased step width has been associated with a greater energy cost of walking. In addition, rehabilitation interventions have been developed to improve the energy cost of walking by addressing motor control.95

Psychological Influences

Pain catastrophizing can be screened by using the Pain Catastrophizing Scale, a 13-item questionnaire that ascertains rumination, magnification, and helplessness surrounding painful experiences.96 Both the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire97 and the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia98 are robust measures of pain-related fear and were either designed for or validated in individuals with persistent LBP. Further, both scales have been used extensively in older adults.

Two established depressive symptom measures for use in older adults are the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale99 and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS).100 The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale is a 20-item scale that poses questions about a person's feelings and behavior based on the number of days experienced over a week's time. The GDS has both a long form (GDS-30) and a short form (GDS-15), although both are similar in that individuals answer “yes” or “no” to questions pertaining to feelings. Importantly, the physical therapist scope of practice precludes diagnosing clinical depression; thus, the suggested measures should be used only as a screening tool for depressive symptoms. Further, physical therapists should maintain adequate communication with primary care physicians regarding positive findings.

A number of pain-related self-efficacy questionnaires exist, both by condition (eg, arthritis), and by outcome (falls, exercise).59,101 Miles et al101 identified 4 aspects of pain self-efficacy that should be addressed in questionnaires: ability to control pain and associated negative emotions, ability to maintain everyday life activities, ability to communicate needs to health care providers, and ability to implement advice about their plan. Two questionnaires incorporate most to all of these suggested aspects of self-efficacy and were deemed more suitable for individuals with persistent pain: the Chronic Disease Self-Efficacy Scale and the Chronic Pain Self-Efficacy Scale.101

Cognitive Influences

Older adults with geriatric LBP may have poorer cognitive performance compared with their peers who are pain free, and/or their cognitive performance may influence their persistent pain. In addition, older adults with geriatric LBP may be at risk for poorer long-term cognitive performance. Therefore, it is important to at least screen for cognitive performance during geriatric LBP management. A well-established screening tool of global cognition is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, a 30-point questionnaire that assesses multiple cognitive constructs, including memory and executive function.102 The Montreal Cognitive Assessment takes approximately 10 minutes to complete and has been administered by physical therapists in the treatment of older adults at risk for falls.103 As with psychological influences, physical therapists should have adequate communication with other medical disciplines regarding positive findings.

Management of Influences on Geriatric LBP (Tab. 2)

Table 2.

Geriatric Low Back Pain (LBP) Interventions.

| Influences | Aerobic Exercise | Strengthening | ROM | Pain Modalities | CBPT | Mindfulness | Graded Tasking | Communication | Referral |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological | |||||||||

| Altered pain neuroprocessing | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Sarcopenia | X | ||||||||

| Hip pathoanatomy | X | X | X | ||||||

| Widespread pain | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Energetic inefficiency | X | ||||||||

| Psychological | |||||||||

| Pain catastrophizing | X | X | X | ||||||

| Pain-related fear | X | X | X | ||||||

| Depressive symptoms | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Reduced pain self-efficacy | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Cognitive | |||||||||

| Reduced memory and executive function | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Social | |||||||||

| Suboptimal medical interaction | X | ||||||||

Biological Influences

Older adults with altered pain neuroprocessing may require either graded exercises or modification to exercise interventions that they perceive to exacerbate other painful regions. A recent study suggests a graded activity program is both feasible and highly accepted by older adults with chronic LBP.104 While passive interventions are usually discouraged in such patients, clinicians may consider additive treatments, in which pain modality interventions such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation are used in conjunction with exercise. Recently, Simon et al105 found transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation to reduce movement-evoked pain in the same capacity for older adults as younger adults, provided amplitude was perceived to be strong yet tolerable.

Sarcopenia and energetic efficiency may potentially impact exercise prescription. Current best evidence suggests that aged skeletal muscle does not hypertrophy in response to resistance training as efficiently as younger muscle106; therefore, a higher training dose is required to increase muscle size and potentially change the ratio of muscle to fat in the trunk musculature.107,108 As such, it is important to consider training approaches that are properly dosed to safely increase muscle size and improve muscle function—such as neuromuscular electrical stimulation, which has been safely used in the geriatric LBP population.21

Psychological and Cognitive Influences

Cognitive-behavioral therapy may have an indirect impact on both psychological and cognitive performance. Cognitive-behavioral physical therapy is emerging in physical therapist practice109 and may be an effective intervention not only for psychological distress but for cognitive influences in older adults. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Richmond et al110 found that cognitive-behavioral therapy was effective for nonspecific LBP, independent of patient characteristics.

Multiple interventions fall within the realm of cognitive-behavioral physical therapy, although a key component is that symptoms of a patient's condition (eg, pain) are a central tenet of treatment. However, mindfulness-based stress reduction is unique to cognitive-behavioral therapy in that the focus is more global (ie, not specific to pain). Recently, a large clinical trial compared mindfulness-based stress reduction to cognitive-behavioral therapy in individuals with persistent LBP and found that both were as effective in improving long-term pain and functional limitations.111 Moreover, both mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive behavioral therapy had similar effects on pain catastrophizing and self-efficacy.112 Mindfulness-based stress reduction has also been found to improve pain and function outcomes for older adults with persistent LBP.113 The benefit of mindfulness-based stress reduction is that it can be integrated into exercises like tai chi, which has been found to improve executive functioning in older adults.114 Although the direct influence of tai chi on pain is still unclear, there is at least some indication for its use in patients with arthritis and LBP.115

A multifaceted intervention for self-efficacy, which also addresses abnormal pain processing and low social interaction, is graded tasking performed in a group setting.59 By performing graded tasks with others experiencing the same condition (eg, geriatric LBP), patients are able to observe successful task completion and successfully complete tasks themselves, all the while receiving verbal encouragement.

Social Influences

Clinicians should have adequate communication with patients to ensure their goals and priorities are adequately known and met. In addition, clinicians can adopt shared goal development with their patients, which is an intuitive way to improve the direction of treatment and ensure that both the patient and the clinician are on the same page. Developing SMART goals (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and timed)116 will improve the rigor of goal development as well as ensure mutual understanding on the part of patient and clinician.

Expanding Geriatric LBP Outcomes

In the following section, we justify using multiple age-appropriate outcome measures to comprehensively define both geriatric LBP experiences and consequences (Figure). We strongly encourage augmenting questionnaires with physical performance measures, which will increase the likelihood of accurately assessing pain with movement and physical function. With such measures, physical therapists can optimize care and also identify future health risks associated with physical activity decline and physical function decline.

Questionnaire-Based Measures

Pain intensity

Undoubtedly, intensity remains the single most assessed construct of pain, in part because pain intensity measures are easily to administer by clinicians and transferrable across the continuum of care. However, it is important for physical therapists to query time frames that are likely to be accurate and not burdensome for older adults. Asking about pain experienced over weeks or months is a difficult question when compared with asking about pain experienced over days or the past 24 hours. Also, pain intensity measures should have established validity based on age group. Visual analog scales—with which pain intensity is marked on a continuous line between 2 anchors—are not ideal because they are difficult to use and susceptible to error in older adults.117 In contrast, numeric pain rating scales—which measure pain on a scale from 0 to 10 or 0 to 100—or verbal descriptor scales are more appropriate for older adults.118

Pain with movement, physical function, and disability

Another problem with pain intensity measures is that they fail to provide an indication of pain with movement and subsequent impact—which is a benefit of pain-related disability questionnaires. The Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale is easy to use and addresses transitional movements that prove difficult or pain limiting for older adults with geriatric LBP.119 The Patient-Specific Functional Scale is a validated, responsive measure that may be even more ideal than the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale, as it allows patients to select and rate functional tasks that are more specific to their limitations.120 The Late Life Function and Disability Instrument is a comprehensive measure that was developed among and is specific to community-dwelling older adults.121,122 Although the Late Life Function and Disability Instrument does not capture pain with movement, it does provide a comprehensive assessment of physical function and disability.

Finally, the National Institutes of Health Task Force on Research Standards for Chronic Low Back Pain proposed a measure of “pain impact” that includes pain intensity, pain interference, and physical function.123 An emerging pain impact assessment tool is the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement System 29-item short form, which supports pain impact recommendations and has good reliability and validity in older adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain.124

Physical activity

Current recommendations are for older adults to participate in 150 hours of moderate activity weekly125 and to avoid sedentary activities such as prolonged sitting, which increase with age and increase the risk for both comorbid conditions and mortality.125 Importantly, sedentary activity occurs as a result of geriatric LBP. The problem for clinicians is that physical activity questionnaires have a high susceptibility for recall bias,125,126 in addition to underreporting of lower to moderate activity, which comprises the majority of exertion by older adults.126 Nevertheless, it's important for clinicians to have some perspective on the amount of physical activity that older adults perform in the natural environment. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form is one of the few questionnaires that have demonstrated both acceptable reliability and validity127 and is indicated for use in both middle-aged and older adults.

Alternatively, clinicians can prescribe an ecologic momentary assessment of daily activity via written or electronic diaries, in which older adults are charged with inputting the amount of physical activity that they achieve per day, including specificity, duration, and intensity. Ecologic momentary assessment has been extensively studied in older adults with pain conditions,128 although it is important for clinicians to consider factors that may affect participation, including physical or cognitive limitations and/or comfort with using technology.128

Performance-Based Geriatric LBP Measures

Questionnaires are valuable for ascertaining the impact of geriatric LBP on free-living physical activity but are limited in scope, particularly for older adults. In addition to recall bias susceptibility,129 questionnaires cannot observe the real-time interface among pain, movement, and compensation. Moreover, knee OA studies have demonstrated a lack of concordance between questionnaire outcomes and performance-based outcomes.130 Although there is clear evidence from the geriatric literature that performance-based measures of function should complement self-report measures, observed performance has not become a well-integrated component of evaluation in the older LBP population—primarily because of the lack of geriatric expertise in this field of study. For best practice, we propose the concurrent use of performance-based measures in geriatric LBP management to more comprehensively assess pain with movement, movement quality, physical activity, and physical function.

Pain with movement

Performance-based measures are a potentially more sensitive and standardized measure of pain with movement. Recent laboratory studies in older adults with knee OA highlight this sensitivity for pain interference. During a stair-climbing task, older adults experienced a more than 110% increase in knee pain.131 Similarly, during the Six-Minute Walk Test, knee pain increased by 130%.132

Performance-based measures for geriatric LBP have been slow to translate to clinical care, in part because most measures have not been psychometrically assessed in older adults. However, a current validated performance-based instrument of LBP disability—which may be used for assessing pain tolerance to movement in some older adults with geriatric LBP—is the Back Performance Scale (BPS).133 The BPS involves 5 activities, including bending, lifting, and transitioning into long-sitting. A recent study of younger and older adults with LBP coupled BPS tasks with movement-evoked pain measurement.105 Similar to aforementioned studies in knee OA, participants with LBP experienced an exponential increase in their pain with BPS tasks. Moreover, movement-evoked pain via the BPS was responsive to the transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation intervention.105 In a subsequent study, movement-evoked pain via the BPS was negatively associated with working memory in younger and older adults with LBP, meaning that those with lower working memory had higher movement-evoked pain.68

Another viable method for measuring pain with movement is to couple with current validated performance measures of physical function. For example, the repeated chair-rise test is an important measure for older adults with geriatric LBP as it involves transitioning and movement of both the trunk and lower extremities. One form is 5 repeated chair rises for a timed score, which Rudy et al55 noted as having high ecologic validity in older adults with geriatric LBP. Another form is the 30-second chair stand test, which The Osteoarthritis Research Society International includes as part of their recommended performance battery.134

Physical activity

An alternative is to physical activity questionnaires is to use wearable devices which, through watches or devices affixed to clothing, capture accelerometry data. Such devices are slow to translate to clinical care, although commercially available wearable activity trackers continue to emerge and have been used to research health and wellness in older adults.135 Although a paucity of research exists on the validity of popular consumer wrist activity trackers, these devices do appear to provide continuous feedback, motivation, and/or reinforcement and are likely to be worn regularly. Moreover, these devices may provide a crude estimate of physical activity change with treatment. However, as with ecologic momentary assessment, clinicians should consider their patient's physical or cognitive limitations and comfort in using such devices.

Physical function

Performance-based physical function tests have long provided indication of morbidity and mortality risks.13 Gait speed is the reference standard measure and can be performed by assessing either time over distance (eg, self-pace walk test) or distance over time as a function of endurance (eg, Six-Minute Walk Test). Gait assessment is commonplace for older adults who have lower extremity musculoskeletal conditions, such as anterior knee pain. However, rarely is gait assessed during geriatric LBP management. Moreover, a recent study demonstrated key characteristics influencing slowed gait speed in older adults, including step width and double limb support time.93

Another physical function performance measure is the Short Physical Performance Battery, which incorporates multiple tests to provide an overall snapshot of physical function; it is one of the most widely used instruments and involves tests for balance, walking, and transitioning.136 However, the Short Physical Performance Battery may be susceptible to ceiling effects, meaning that it has better responsiveness for individuals who are more frail than for those with higher functioning. A viable alternative is the Health ABC Physical Performance Battery, which involves both gait and chair stands as well as measures of standing and dynamic balance.10 Balance should be a crucial component to geriatric LBP management because older adults with geriatric LBP are susceptible to falls.93

Conclusion

Optimal geriatric LBP management is founded on a comprehensive understanding of age-specific biological, psychological, cognitive, and social influences, including measurement and treatment of such influences. Physical therapists should be aware of senescent changes to body systems that may render older adults susceptible to persistent pain, physical activity decline, and physical function decline. Further, clinicians should use a multidimensional battery of outcome measures to account for pain intensity, pain with movement, physical activity, and physical function. Collectively, this approach will increase the effectiveness of physical therapy for geriatric LBP and contribute to overall health of older adults by mitigating potential health-related risks.

Author Contributions

Concept/idea/research design: C.B. Simon, G.E. Hicks

Writing: C.B. Simon, G.E. Hicks

Consultation (including review of manuscript before submitting): G.E. Hicks

Funding

G.E. Hicks was supported by Award Number R01AG0412202 from the National Institute on Aging. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

The authors completed the ICJME Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. They reported no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Buchbinder R, Blyth FM, March LM, Brooks P, Woolf AD, Hoy DG. Placing the global burden of low back pain in context. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:575–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hicks GE, Morone N, Weiner DK. Degenerative lumbar disc and facet disease in older adults: prevalence and clinical correlates. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:1301–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brinjikji W, Luetmer PH, Comstock B et al. Systematic literature review of imaging features of spinal degeneration in asymptomatic populations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36:811–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jarvik JG, Gold LS, Comstock BA et al. Association of early imaging for back pain with clinical outcomes in older adults. JAMA. 2015;313:1143–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Main CJ, George SZ. Psychologically informed practice for management of low back pain: future directions in practice and research. Phys Ther. 2011;91:820–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gibson SJ, Farrell M. A review of age differences in the neurophysiology of nociception and the perceptual experience of pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:227–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lautenbacher S. Experimental approaches in the study of pain in the elderly. Pain Med. 2012;13:S44–S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fielding RA, Vellas B, Evans WJ et al. Sarcopenia: an undiagnosed condition in older adults. Current consensus definition: prevalence, etiology, and consequences. International working group on sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12:249–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nelson M, Rejeski W, Blair S et al. Physical activity and public health in older adults: recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;116:1094–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hicks GE, Simonsick EM, Harris TB et al. Trunk muscle composition as a predictor of reduced functional capacity in the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study: the moderating role of back pain. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:1420–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaminsky LA, Arena R, Beckie TM et al. The importance of cardiorespiratory fitness in the United States: the need for a national registry—a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:652–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Perera S, Studenski S, Chandler JM, Guralnik JM. Magnitude and patterns of decline in health and function in 1 year affect subsequent 5-year survival. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:894–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K et al. Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA. 2011;305:50–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Belsky DW, Caspi A, Houts R et al. Quantification of biological aging in young adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E4104–E4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Riley JL III, King CD, Wong F, Fillingim RB, Mauderli AP. Lack of endogenous modulation and reduced decay of prolonged heat pain in older adults. Pain. 2010;150:153–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Riley JL, Cruz-Almeida Y, Dasilva Ribeiro MC et al. Age differences in the time course and magnitude of changes in circulating neuropeptides after pain evocation in humans. J Pain. 2017;18:1078–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goodpaster BH, Carlson CL, Visser M et al. Attenuation of skeletal muscle and strength in the elderly: the Health ABC Study. J Appl Physiol ( 1985). 2001;90:2157–2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brown JC, Harhay MO, Harhay MN. Sarcopenia and mortality among a population‐based sample of community‐dwelling older adults. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016;7:290–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sions JM, Elliott JM, Pohlig RT, Hicks GE. Trunk muscle characteristics of the multifidi, erector spinae, psoas, and quadratus lumborum in older adults with and without chronic low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017;47:173–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hicks GE, Simonsick EM, Harris TB et al. Cross-sectional associations between trunk muscle composition, back pain, and physical function in the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:882–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hicks GE, Sions JM, Velasco TO, Manal TJ. Trunk muscle training augmented with neuromuscular electrical stimulation appears to improve function in older adults with chronic low back pain: a randomized preliminary trial. Clin J Pain. 2016;32:898–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Whitson HE, Johnson KS, Sloane R et al. Identifying patterns of multimorbidity in older Americans: application of latent class analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:1668–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wolfe F. Determinants of WOMAC function, pain and stiffness scores: evidence for the role of low back pain, symptom counts, fatigue and depression in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999;38:355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hicks GE, Sions J, Velasco T. Hip symptoms contribute to low back pain-related disability in older adults with a primary complaint of low back pain: the Delaware spine studies. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24(suppl 1):S439. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hicks GE, Sions JM, Velasco TO. Hip symptoms, physical performance, and health status in older adults with chronic low back pain: a preliminary investigation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017October 27 [E-pub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rundell SD, Goode AP, Suri P et al. Effect of comorbid knee and hip osteoarthritis on longitudinal clinical and health care use outcomes in older adults with new visits for back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kamaleri Y, Natvig B, Ihlebaek CM, Benth JS, Bruusgaard D. Change in the number of musculoskeletal pain sites: a 14-year prospective study. Pain. 2009;141:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thomas E, Peat G, Harris L, Wilkie R, Croft PR. The prevalence of pain and pain interference in a general population of older adults: cross-sectional findings from the North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project (NorStOP). Pain. 2004;110:361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Carlesso LC, Segal NA, Curtis JR et al. Knee pain and structural damage as risk factors for incident widespread pain: data from the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69:826–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Riddle DL, Stratford PW. Knee pain during daily tasks, knee osteoarthritis severity, and widespread pain. Phys Ther. 2014;94:490–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carlesso LC, Niu J, Segal NA et al. The effect of widespread pain on knee pain worsening, incident knee osteoarthritis (OA), and incident knee pain: the Multicenter OA (MOST) Study. J Rheumatol. 2017;44:493–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Artus M, Campbell P, Mallen CD, Dunn KM, van der Windt DAW. Generic prognostic factors for musculoskeletal pain in primary care: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e012901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schrack JA, Simonsick EM, Chaves PHM, Ferrucci L. The role of energetic cost in the age-related slowing of gait speed. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1811–1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schrack JA, Zipunnikov V, Simonsick EM, Studenski S, Ferrucci L. Rising energetic cost of walking predicts gait speed decline with aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71:947–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Coyle PC, Schrack JA, Hicks GE. Pain energy model of mobility limitation in the older adult. Pain Med. 2017May 22 [E-pub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnx089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gussoni M, Margonato V, Ventura R, Veicsteinas A. Energy cost of walking with hip joint impairment. Phys Ther. 1990;70:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leeuw M, Goossens ME, Linton SJ, Crombez G, Boersma K, Vlaeyen JW. The fear-avoidance model of musculoskeletal pain: current state of scientific evidence. J Behav Med. 2007;30:77–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Crombez G, Eccleston C, Van Damme S Vlaeyen JWS, Karoly P. Fear-avoidance model of chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2012;28:475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Quartana PJ, Campbell CM, Edwards RR. Pain catastrophizing: a critical review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:745–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Turner JA, Mancl L, Aaron LA. Pain-related catastrophizing: a daily process study. Pain. 2004;110:103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Keefe FJ, Williams DA. A comparison of coping strategies in chronic pain patients in different age groups. J Gerontol. 1990;45:P161–P165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ruscheweyh R, Nees F, Marziniak M, Evers S, Flor H, Knecht S. Pain catastrophizing and pain-related emotions: influence of age and type of pain. Clin J Pain. 2011;27:578–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Somers TJ, Keefe FJ, Pells JJ et al. Pain catastrophizing and pain-related fear in osteoarthritis patients: relationships to pain and disability. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:863–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Crombez G, Vlaeyen JW, Heuts PH, Lysens R. Pain-related fear is more disabling than pain itself: evidence on the role of pain-related fear in chronic back pain disability. Pain. 1999;80:329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cook AJ, Brawer PA, Vowles KE. The fear-avoidance model of chronic pain: validation and age analysis using structural equation modeling. Pain. 2006;121:195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Riley JL III, Wade JB, Robinson ME, Price DD. The stages of pain processing across the adult lifespan. J Pain. 2000;1:162–170. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Albaret MC, Muñoz Sastre MT, Cottencin A, Mullet E. The Fear of Pain questionnaire: factor structure in samples of young, middle-aged and elderly European people. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sions JM, Hicks GE. Fear-avoidance beliefs are associated with disability in older American adults with low back pain. Phys Ther. 2011;91:525–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zale EL, Lange KL, Fields SA, Ditre JW. The relation between pain-related fear and disability: a meta-analysis. J Pain. 2013;14:1019–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Christensen H, Jorm AF, Mackinnon AJ et al. Age differences in depression and anxiety symptoms: a structural equation modelling analysis of data from a general population sample. Psychol Med. 1999;29:325–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Newmann JP. Aging and depression. Psychol Aging. 1989;4:150–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Blazer D, Burchett B, Service C, George LK. The association of age and depression among the elderly: an epidemiologic exploration. J Gerontol. 1991;46:M210–M215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Turk DC, Okifuji A, Scharff L. Chronic pain and depression: role of perceived impact and perceived control in different age cohorts. Pain. 1995;61:93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jorm AF, Windsor TD, Dear KBG, Anstey KJ, Christensen H, Rodgers B. Age group differences in psychological distress: the role of psychosocial risk factors that vary with age. Psychol Med. 2005;35:1253–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rudy TE, Weiner DK, Lieber SJ, Slaboda J, Boston JR. The impact of chronic low back pain on older adults. Pain. 2007;131:293–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hawker GA, Gignac MAM, Badley E et al. A longitudinal study to explain the pain-depression link in older adults with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:1382–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kvelde T, McVeigh C, Toson B et al. Depressive symptomatology as a risk factor for falls in older people: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:694–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wilson RS, Capuano AW, Boyle PA et al. Clinical-pathologic study of depressive symptoms and cognitive decline in old age. Neurology. 2014;83:702–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jackson T, Wang Y, Wang Y, Fan H. Self-efficacy and chronic pain outcomes: a meta-analytic review. J Pain. 2014;15:800–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Grembowski D, Patrick D, Diehr P et al. Self-efficacy and health behavior among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 1993;34:89–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Clark DO. Age, socioeconomic status, and exercise self-efficacy. Gerontologist. 1996;36:157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Larsson C, Ekvall Hansson E, Sundquist K, Jakobsson U. Impact of pain characteristics and fear-avoidance beliefs on physical activity levels among older adults with chronic pain: a population-based, longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Quicke JG, Foster NE, Ogollah RO, Croft PR, Holden MA. Relationship between attitudes and beliefs and physical activity in older adults with knee pain: secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69:1192–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Turner JA, Ersek M, Kemp C. Self-efficacy for managing pain is associated with disability, depression, and pain coping among retirement community residents with chronic pain. J Pain. 2005;6:471–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Marszalek J, Price LL, Harvey WF, Driban JB, Wang C. Outcome expectations and osteoarthritis: association of perceived benefits of exercise with self-efficacy and depression. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69:491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Berryman C, Stanton TR, Bowering KJ, Tabor A, McFarlane A, Moseley GL. Do people with chronic pain have impaired executive function? A meta-analytical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34:563–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Berryman C, Stanton TR, Jane Bowering K, Tabor A, McFarlane A, Moseley LG. Evidence for working memory deficits in chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2013;154:1181–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Simon CB, Lentz TA, Bishop MD, Riley JL, Fillingim RB, George SZ. Comparative associations of working memory and pain catastrophizing with chronic low back pain intensity. Phys Ther. 2016;96:1049–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Park DC, Reuter-Lorenz P. The adaptive brain: aging and neurocognitive scaffolding. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:173–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. van der Leeuw G, Eggermont LH, Shi L et al. Pain and cognitive function among older adults living in the community. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71:398–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Weiner DK, Rudy TE, Morrow L, Slaboda J, Lieber S. The relationship between pain, neuropsychological performance, and physical function in community-dwelling older adults with chronic low back pain. Pain Med. 2006;7:60–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Morone NE, Abebe KZ, Morrow LA, Weiner DK. Pain and decreased cognitive function negatively impact physical functioning in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Pain Med. 2014;15:1481–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Attal N, Masselin-Dubois A, Martinez V et al. Does cognitive functioning predict chronic pain? Results from a prospective surgical cohort. Brain. 2014;137:904–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Latimer J, Adams RD. The therapeutic alliance between clinicians and patients predicts outcome in chronic low back pain. Phys Ther. 2013;93:470–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Fuentes J, Armijo-Olivo S, Funabashi M et al. Enhanced therapeutic alliance modulates pain intensity and muscle pain sensitivity in patients with chronic low back pain: an experimental controlled study. Phys Ther. 2014;94:477–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Linton SJ, Vlaeyen J, Ostelo R. The back pain beliefs of health care providers: are we fear-avoidant? J Occup Rehabil. 2002;12:223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Main CJ, Foster N, Buchbinder R. How important are back pain beliefs and expectations for satisfactory recovery from back pain? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24:205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bishop A, Foster NE, Thomas E, Hay EM. How does the self-reported clinical management of patients with low back pain relate to the attitudes and beliefs of health care practitioners? A survey of UK general practitioners and physiotherapists. Pain. 2008;135:187–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Darlow B, Fullen BM, Dean S, Hurley DA, Baxter GD, Dowell A. The association between health care professional attitudes and beliefs and the attitudes and beliefs, clinical management, and outcomes of patients with low back pain: a systematic review. Eur J Pain. 2012;16:3–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Cayea D, Perera S, Weiner DK. Chronic low back pain in older adults: what physicians know, what they think they know, and what they should be taught. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1772–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Makris UE, Higashi RT, Marks EG et al. Ageism, negative attitudes, and competing co-morbidities: why older adults may not seek care for restricting back pain—a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sions JM, Smith AC, Hicks GE, Elliott JM. Trunk muscle size and composition assessment in older adults with chronic low back pain: an intra-examiner and inter-examiner reliability study. Pain Med. 2016;17:1436–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Sions JM, Velasco TO, Teyhen DS, Hicks GE. Reliability of ultrasound imaging for the assessment of lumbar multifidi thickness in older adults with chronic low back pain. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2015;38:33–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. McGill SM, Childs A, Liebenson C. Endurance times for low back stabilization exercises: clinical targets for testing and training from a normal database. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:941–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Suri P, Kiely DK, Leveille SG, Frontera WR, Bean JF. Trunk muscle attributes are associated with balance and mobility in older adults: a pilot study. PM R. 2009;1:916–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Suri P, Kiely DK, Leveille SG, Frontera WR, Bean JF. Increased trunk extension endurance is associated with meaningful improvement in balance among older adults with mobility problems. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:1038–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Neblett R, Cohen H, Choi Y et al. The Central Sensitization Inventory (CSI): establishing clinically-significant values for identifying central sensitivity syndromes in an outpatient chronic pain sample. J Pain. 2013;14:438–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, Tölle TR. painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:1911–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Hochman JR, Davis AM, Elkayam J, Gagliese L, Hawker GA. Neuropathic pain symptoms on the modified painDETECT correlate with signs of central sensitization in knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:1236–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Offierski CM, MacNab I. Hip-spine syndrome. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1983;8:316–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Cibulka MT, White DM, Woehrle J et al. Hip pain and mobility deficits: hip osteoarthritis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39:A1–A25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Delitto A, George SZ, Van Dillen LR et al. Low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42:A1–A57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Hicks GE, Sions JM, Coyle PC, Pohlig RT. Altered spatiotemporal characteristics of gait in older adults with chronic low back pain. Gait Posture. 2017;55:172–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Wert DM, Brach J, Perera S, VanSwearingen JM. Gait biomechanics, spatial and temporal characteristics, and the energy cost of walking in older adults with impaired mobility. Phys Ther. 2010;90:977–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Brach JS, Lowry K, Perera S et al. Improving motor control in walking: a randomized clinical trial in older adults with subclinical walking difficulty. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:388–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:524–532. [Google Scholar]

- 97. Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main CJ. A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain. 1993;52:157–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Roelofs J, Goubert L, Peters ML, Vlaeyen JWS, Crombez G. The Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia: further examination of psychometric properties in patients with chronic low back pain and fibromyalgia. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Caracciolo B, Giaquinto S. Criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale in a sample of rehabilitation inpatients. J Rehabil Med. 2002;34:221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17:37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Miles CL, Pincus T, Carnes D, Taylor SJC, Underwood M. Measuring pain self-efficacy. Clin J Pain. 2011;27:461–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Matchar DB, Duncan PW, Lien CT et al. Randomized controlled trial of screening, risk modification, and physical therapy to prevent falls among the elderly recently discharged from the emergency department to the community: the Steps to Avoid Falls in the Elderly Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:1086–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Kuss K, Leonhardt C, Quint S et al. Graded activity for older adults with chronic low back pain: program development and mixed methods feasibility cohort study. Pain Med. 2016;17:2218–2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Simon CB, Riley JL, Fillingim RB, Bishop MD, George SZ. Age group comparisons of TENS response among individuals with chronic axial low back pain. J Pain. 2015;16:1268–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Raue U, Slivka D, Minchev K, Trappe S. Improvements in whole muscle and myocellular function are limited with high-intensity resistance training in octogenarian women. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2009;106:1611–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Delmonico MJ, Harris TB, Visser M et al. Longitudinal study of muscle strength, quality, and adipose tissue infiltration. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1579–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Frontera WR, Suh D, Krivickas LS, Hughes VA, Goldstein R, Roubenoff R. Skeletal muscle fiber quality in older men and women. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C611–C618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Archer KR, Devin CJ, Vanston SW et al. Cognitive-behavioral–based physical therapy for patients with chronic pain undergoing lumbar spine surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain. 2016;17:76–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Richmond H, Hall AM, Copsey B et al. The effectiveness of cognitive behavioural treatment for non-specific low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0134192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Balderson BH et al. Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction vs cognitive behavioral therapy or usual care on back pain and functional limitations in adults with chronic low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:1240–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Turner JA, Anderson ML, Balderson BH, Cook AJ, Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic low back pain: similar effects on mindfulness, catastrophizing, self-efficacy, and acceptance in a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2016;157:2434–2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Morone NE, Greco CM, Moore CG et al. A mind-body program for older adults with chronic low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:329–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Wayne PM, Walsh JN, Taylor-Piliae RE et al. Effect of Tai Chi on cognitive performance in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:25–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Hall A, Copsey B, Richmond H et al. Effectiveness of Tai Chi for chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther. 2017;97:227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Doran GT. There's a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management's goals and objectives. Management Review. AMA FORUM 1981;70(11):35–36. [Google Scholar]

- 117. Gagliese L. Pain and aging: the emergence of a new subfield of pain research. J Pain Off J Am Pain Soc. 2009;10:343–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Herr KA, Spratt K, Mobily PR, Richardson G. Pain intensity assessment in older adults: use of experimental pain to compare psychometric properties and usability of selected pain scales with younger adults. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:207–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Smeets R, Köke A, Lin C-W, Ferreira M, Demoulin C. Measures of function in low back pain/disorders: Low Back Pain Rating Scale (LBPRS), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Progressive Isoinertial Lifting Evaluation (PILE), Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale (QBPDS), and Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RDQ). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(suppl 11):S158–S173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Pengel LHM, Refshauge KM, Maher CG. Responsiveness of pain, disability, and physical impairment outcomes in patients with low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:879–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Jette AM, Haley SM, Coster WJ et al. Late Life Function and Disability Instrument, I: development and evaluation of the disability component. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:M209–M216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Haley SM, Jette AM, Coster WJ et al. Late Life Function and Disability Instrument, II: development and evaluation of the function component. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:M217–M222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Deyo RA, Dworkin SF, Amtmann D et al. Report of the NIH Task Force on Research Standards for Chronic Low Back Pain. Phys Ther. 2015;95:e1–e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Deyo RA, Ramsey K, Buckley DI et al. Performance of a Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) short form in older adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain Med. 2016;17:314–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Sparling PB, Howard BJ, Dunstan DW, Owen N. Recommendations for physical activity in older adults. BMJ. 2015;350:h100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Schrack JA, Cooper R, Koster A et al. Assessing daily physical activity in older adults: unraveling the complexity of monitors, measures, and methods. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71:1039–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Helmerhorst HJ, Brage S, Warren J, Besson H, Ekelund U. A systematic review of reliability and objective criterion-related validity of physical activity questionnaires. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Morren M, van Dulmen S, Ouwerkerk J, Bensing J. Compliance with momentary pain measurement using electronic diaries: a systematic review. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:354–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Stull DE, Leidy NK, Parasuraman B, Chassany O. Optimal recall periods for patient-reported outcomes: challenges and potential solutions. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:929–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Stevens-Lapsley JE, Schenkman ML, Dayton MR. Comparison of self-reported knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score to performance measures in patients after total knee arthroplasty. PM R. 2011;3:541–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Harden RN, Wallach G, Gagnon CM et al. The osteoarthritis knee model: psychophysical characteristics and putative outcomes. J Pain. 2013;14:281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Wideman TH, Finan PH, Edwards RR et al. Increased sensitivity to physical activity among individuals with knee osteoarthritis: relation to pain outcomes, psychological factors, and responses to quantitative sensory testing. Pain. 2014;155:703–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Strand LI, Moe-Nilssen R, Ljunggren AE. Back Performance Scale for the assessment of mobility-related activities in people with back pain. Phys Ther. 2002;82:1213–1223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Dobson F, Hinman RS, Roos EM et al. OARSI recommended performance-based tests to assess physical function in people diagnosed with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:1042–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Patel S, Park H, Bonato P, Chan L, Rodgers M. A review of wearable sensors and systems with application in rehabilitation. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2012;9:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M85–M94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]