Abstract

Beige adipocytes are an inducible form of thermogenic adipose cells that emerge within the white adipose tissue in response to a variety of environmental stimuli, such as chronic cold acclimation. Similar to brown adipocytes that reside in brown adipose tissue depots, beige adipocytes are also thermogenic; however, beige adipocytes possess unique, distinguishing characteristics in their developmental regulation and biological function. This review highlights recent advances in our understanding of beige adipocytes, focusing on the diverse roles of beige fat in the regulation of energy homeostasis that are independent of the canonical thermogenic pathway via uncoupling protein 1.

This review highlights recent advances in the field of thermogenic adipose cells: brown fat and beige fat in the regulation of energy homeostasis.

Adipose tissue is a remarkably complex tissue that plays key roles in both the regulation of energy storage in the form of triglycerides, predominantly carried out by white adipose tissue (WAT), and energy dissipation in the form of heat, which is mediated by brown adipose tissue (BAT). Morphologically, these two tissue types are distinct: white adipocytes in the WAT contain unilocular lipid droplets and low mitochondrial content, whereas brown adipocytes in the BAT contain numerous smaller multilocular lipid droplets and mitochondria with high cristae density.

Subcutaneous WAT depots contain another form of thermogenic adipocyte, referred to as beige adipocytes (or brite adipocytes). Like brown adipocytes residing in the BAT, beige adipocytes also contain multilocular lipid droplets and densely packed mitochondria. However, despite the morphological similarity, beige adipocytes are distinct from brown adipocytes in their developmental origin and regulation. In contrast to brown adipocytes residing in the interscapular BAT depots that originated from progenitors expressing myogenic factor 5 (MYF5) and paired box protein 7 (PAX7), beige adipocytes arise from a subset of progenitors that express platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRα), smooth muscle actin protein 1 (SMA1), myosin heavy chain 11 (MYH11), or platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFRβ) (1). In addition, recruitment of adipocyte differentiation is highly induced in response to a variety of environmental cues, such as cold exposure, exercise, synthetic ligands of peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ, and tissue injury (2). The various similarities and distinctions exhibited by these two thermogenic adipose cell types have recently been reviewed (3). It is important to note that adult humans possess this inducible form of thermogenic adipose cells that resemble murine beige adipocytes (4–7). To support that notion, recent studies using positron emission tomography/CT demonstrated that prolonged cold acclimation promoted the recruitment of new thermogenic adipose tissue, even in human subjects who did not possess previously identifiable levels of thermogenic adipocytes (8–11).

Thermogenesis carried out by brown fat and beige fat does not require muscle shivering and is thus referred to as nonshivering thermogenesis. It was previously thought that adipose tissue thermogenesis exclusively relied on the action of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), a mitochondrial protein found intercalated within the inner mitochondria membrane. In response to cold exposure or activation of the β-adrenergic receptor signaling, UCP1 uncouples the electrochemical gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane from mitochondrial ATP synthesis, due to UCP1-mediated proton leak, thereby converting the energy in the form of heat (12). Importantly, UCP1 knockout (KO) mice develop severe hypothermia following cold exposure, whereas genetic deletion of other members of the UCP family (UCP2 and UCP3) do not cause hypothermia in mice. Accordingly, UCP1 has been considered the only form of UCP responsible for mediating nonshivering thermogenesis in mammals (13, 14).

However, rodent studies indicate an incongruity in the metabolic phenotypes of thermogenic fat-deficient mice and UCP1-deficient mice. For instance, adipocyte-specific deletion of PR domain zinc finger protein 16 (PRDM16) or its cofactor enzyme euchromatic histone-lysine N-methyltransferase 1 causes beige fat depletion in the subcutaneous WAT and leads to the development of obesity and systemic insulin resistance in mice (15, 16). In addition, chemical depletion of brown/beige fat by transgenic expression of diphtheria toxin driven by the Ucp1 gene enhancer/promoter leads to obesity and insulin resistance in mice even under ambient temperature conditions (17). By contrast, UCP1 null mice develop hypothermia but do not display either the diabetic or obesity phenotypes unless kept under a thermoneutral environment (18, 19). This inconsistency in metabolic phenotypes suggests that thermogenic adipose cells possess UCP1-independent mechanisms that control whole-body energy homeostasis and glucose homeostasis. This review will discuss recent studies reporting such UCP1-independent mechanisms of thermogenic fat cells.

UCP1-Independent Mechanisms of Fat Thermogenesis

As mentioned earlier, UCP1 null mice develop severe hypothermia when mice are challenged with a cold environment (13, 19). Intriguingly, however, when UCP1 null mice are gradually acclimated to cold temperature by lowering the ambient temperature by 2°C/day, UCP1 null mice can maintain their core body temperature and survive regardless their genetic background (C57BL/6 and 129S1/SvImJ) (20). Although skeletal muscle thermogenesis can contribute to the maintenance of core body temperature (13, 21), a recent study used tissue temperature recording and demonstrated that beige fat in the subcutaneous WAT plays a major role in the regulation of core body temperature maintenance in the absence of UCP1 (22). This study implemented a mouse model in which beige adipocyte biogenesis is genetically activated by the fat-selective transgenic expression of PRDM16 in a Ucp1 null background (Fabp4-Prdm16Tg × Ucp1−/−). Surprisingly, Fabp4-Prdm16Tg × Ucp1−/− mice are completely protected from cold-induced hypothermia, whereas skeletal muscle thermogenesis does not contribute much to the phenotype. Instead, this phenotype is due to cell-autonomous thermogenic activity of beige adipocytes, because cultured beige adipocytes from Fabp4-Prdm16Tg × Ucp1−/− mice show a robust thermogenic response in response to norepinephrine treatment. Importantly, increased beige fat mass induced by PRDM16 transgenic expression protected mice from high diet-induced body weight gain and glucose intolerance even in the absence of UCP1 (22). These findings indicate that UCP1 is dispensable for beige fat thermogenesis as well as their antiobesity and antidiabetic actions in vivo.

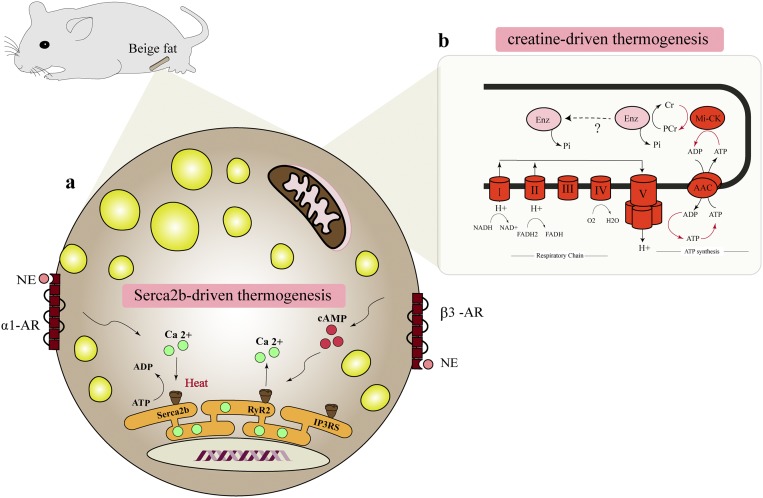

Mechanistically, we found that calcium cycling involving the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2b (SERCA2b) and ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2) pathway is responsible for UCP1-independent thermogenesis in beige adipocytes (Fig. 1). In fact, disruption of Ca2+ cycling in adipocytes, caused by the fat-specific deletion of SERCA2 encoded by the Atp2a gene, impaired thermogenesis in the subcutaneous WAT. SERCA2b-mediated Ca2+ cycling thermogenesis occurs when ATP hydrolysis by SERCA2b is uncoupled from Ca2+ uptake (i.e., ATP-dependent thermogenesis); however, the molecules responsible for uncoupling ATP hydrolysis and Ca2+ uptake by SERCA2b remain undetermined. Of note, as demonstrated by numerous papers in the past, UCP1-meidated thermogenesis plays a dominant role in brown adipocytes in the BAT. The difference between brown fat and beige fat in their thermogenic mechanism is potentially explained by the fact that brown adipocytes have a lower ATP synthesis capacity, rendering ATP-dependent thermogenesis by Ca2+ cycling untenable in brown fat. In contrast, beige fat has a much higher capacity to generate ATP in the mitochondria such that ATP-dependent thermogenesis can compensate for the lack of UCP1 in beige fat.

Figure 1.

UCP1-independent thermogenesis in beige adipocytes. (a) Fat-specific PRDM16 transgenic mice in a UCP1 KO background (PRDM16 Tg × UCP1 KO mice) possess an alternative thermogenic mechanism that involves ATP-dependent Ca2+ cycling by SERCA2b and RyR2. Pharmacological activation of α1- and/or β3-adrenergic receptors enhances Ca2+ cycling and UCP1-independent thermogenesis in beige adipocytes. (b) Cold exposure also activates another thermogenic mechanism by a futile creatine-driven cycle coupled to mitochondria ATP synthesis in beige adipocytes. AAC, ATP/ADP carrier; Cr, creatine; Enz, enzyme; Mi-CK, mitochondrial creatine kinase; NE, norepinephrine; PCr, phosphocreatine; Pi, inorganic phosphate; α1-AR, α1-adrenergic receptor; β3-AR, β3-adrenergic receptor.

Thermogenesis is one of the fundamental homeostatic systems in mammals, and thus, multiple pathways have evolved to preserve animals from hypothermia. Another example of UCP1-independent thermogenesis is futile creatine substrate cycling, which is active in the mitochondria of brown and beige adipocytes (23). A recent study demonstrated that adipocyte-specific deletion of a rate-limiting enzyme of creatine biosynthesis, glycine amidinotransferase, causes hypothermia following cold exposure, reduces whole-body energy expenditure, and mitigates diet-induced body weight gain (24). Because disruption of the creatine cycling pathway causes thermal defects even in the presence of UCP1, this UCP1-independent pathway also plays a crucial role in the regulation of whole-body energy expenditure. Additional UCP1-independent mechanisms for thermogenesis have been proposed, including triglyceride-fatty acid cycling (25). Thiazolidinediones, synthetic ligands for peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ, induce glycerol kinase in adipocytes and stimulate the futile cycle of triglyceride breakdown and subsequent resynthesis from glycerol and fatty acids (26). The contribution of this pathway at the whole-body level, however, remains unknown. This finding is of interest because thiazolidinediones also powerfully activate SERCA2 expression in beige adipocytes (unpublished data). Overall, it will be important to address the relative contribution of UCP1-dependent and these UCP1-independent thermogenic pathways to the regulation of whole-body energy expenditure and systemic glucose homeostasis.

In contrast to the long-standing paradigm that UCP1 is the only active thermogenin in mammals, a recent study reported that inactivating mutations in the Ucp1 gene occurs in a variety of mammalian species, at least 8 of the 18 traditional placental orders (27). For instance, exons 3 to 5 in the Ucp1 gene were deleted in pigs ∼20 million years ago (28). Notably, Ca2+ cycling thermogenesis by SERCA2b plays a critical role in pig adipocyte thermogenesis. In fact, expression of RyR2 in pig adipocytes activates UCP1-independent thermogenesis. Thus, Ca2+ cycling thermogenesis is an evolutionally conserved mechanism that exists not only in humans and rodents, but also in pigs (22). A better understanding of thermogenic mechanisms in UCP1-defective animals may identify previously uncharacterized thermogenic pathways in the future.

UCP1-Independent Regulation of Adipose Tissue Fibrosis

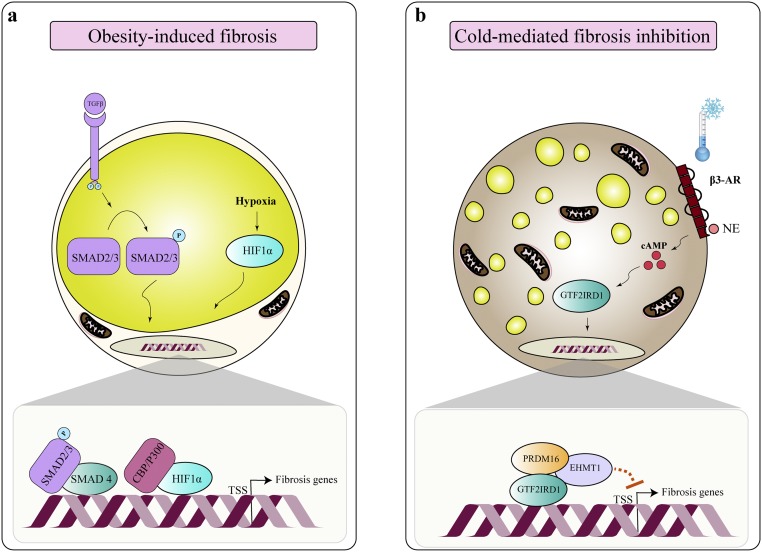

The plasticity of adipose tissue mass is a physiological adjustment to metabolic demand. Adipose tissue shrinks through lipolysis under the conditions of energy deprivation, whereas it dramatically expands through lipogenesis in response to overfeeding (29). Such changes in adipocyte size are accompanied by modifications of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. During the initiation of obesity, ECM proteins (e.g., collagens and elastins) accumulate to facilitate the adipose tissue expansion, but an excessive accumulation of ECM proteins leads to increased adipose tissue fibrosis that is closely associated with infiltration of proinflammatory immune cells in the adipose tissue (30). It is also important to note that adipose tissue fibrosis is strongly linked to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes in humans and rodents (31–35).

Genetic studies in rodents suggest that adipose tissue fibrosis is not simply a metabolic consequence of obesity and obesity-induced inflammation. For instance, reducing adipose tissue fibrosis by genetic deletion of adipose tissue-enriched collagen type VI, one of the representative collagens in the adipose tissue, significantly alleviates obesity-induced glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in mice (36). Furthermore, our recent study showed that reducing adipose tissue fibrosis by the adipose tissue-selective overexpression of general transcription factor II-I repeat domain-containing protein 1 (GTF2IRD1), a member of the TFII-I family of DNA-binding proteins, significantly improves glucose homeostasis and adipocyte insulin sensitivity (37). Because the improvement in glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity by GTF2IRD1 transgenic expression occurs prior to changes in adipose tissue inflammation and independent of body weight (37), repression of adipose tissue fibrosis is directly linked to the improvement in adipose tissue homeostasis and metabolic health.

One of the intriguing observations made by this study (37) is that adipose tissue fibrosis is inversely associated with beige adipocyte biogenesis in a UCP1-independent fashion (i.e., increased beige adipocyte biogenesis by chronic cold acclimation or PRDM16 overexpression significantly inhibits adipose tissue fibrosis in the subcutaneous adipose tissue of UCP1 null mice). Hence, it is likely that increased beige adipocyte mass prevents the profibrosis program in adipose tissue. How does beige adipocyte biogenesis antagonize the formation of adipose tissue fibrosis? In response to cold exposure or β-adrenergic stimulus, we found that PRDM16 forms a transcriptional complex with GTF2IRD1, a cold-inducible DNA-binding transcription factor, which mediates the repressive action of the PRDM16 complex on profibrosis gene expression (37) (Fig. 2). As mentioned above, overexpression of GTF2IRD1 represses adipose tissue fibrosis, whereas depletion of GTF2IRD1 in adipocytes activates the expression of profibrosis genes. These findings suggest a mechanism by which beige adipocyte biogenesis improves systemic glucose homeostasis, in part, through inhibiting adipose tissue fibrosis in a UCP1-independent fashion. It is worth noting that multiple cell types, besides adipocytes, contribute to ECM deposition in adipose tissues; these cell types include myofibroblasts, perivascular cells expressing Nestin, macrophages, and PDGFRa+ cells expressing high levels of CD9 (38–41). Hence, multiple pathways in each cell type likely contribute to the regulation of adipose tissue fibrosis. In this regard, it is vital to understand the mechanism by which beige adipocytes communicate with other cell types (e.g., myofibroblasts and endothelium) in the adipose tissue through heat as well as secretory molecules from beige adipocytes. The role of brown/beige fat as a secretory tissue will be discussed in the next chapter.

Figure 2.

Regulation of adipose tissue fibrosis. (a) Under an obese state, adipose tissue fibrosis is induced by the action of TGF-β and hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α). (b) Cold exposure not only induces beige adipocyte biogenesis but also represses adipose tissue fibrosis. Mechanistically, cold exposure stimulates the assembly of a PRDM16–euchromatic histone-lysine N-methyltransferase 1–GTF2IRD1 transcription complex that represses transcription of profibrosis genes. EHMT1, euchromatic histone-lysine N-methyltransferase 1; NE, norepinephrine; TSS, transcription start site; β3-AR, β3-adrenergic receptor.

The Role of Secreted Factors From Thermogenic Adipocytes

Although the major function of brown and beige cells is to protect the body against hypothermia by nonshivering thermogenesis, emerging evidence suggests an important secretory role of thermogenic adipocytes (2, 42). In this review, we summarize secretory molecules that are released from brown and beige adipocytes (so-called batokines) that act in an endocrine or autocrine/paracrine manner (Table 1) and are also discussed later.

Table 1.

Secreted Factors From Brown and Beige Adipocytes

| Target Tissue | Action | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autocrine/paracrine factors | |||

| VEGFA | BAT | Increase vascularization and stimulate thermogenesis | (43, 44) |

| NO | BAT | Enhance blood flow and increase thermogenesis | (45) |

| BMP8b | BAT | Stimulate thermogenesis | (46) |

| 12-13-diHOME | BAT | Increase free fatty acid uptake and thermogenesis | (47) |

| Prostaglandin | BAT/WAT | Induce beige adipocyte biogenesis and increase thermogenesis | (48, 49) |

| sLR11 | BAT | Suppress thermogenesis | (50) |

| Endothelin-1 | BAT | Suppress thermogenesis | (51) |

| Endocannabinoids | BAT | Suppress thermogenesis | (52, 53) |

| Endocrine factors | |||

| FGF21 | Multiple | In adipose tissue, induce beige adipocyte biogenesis and BAT/beige thermogenesis | (54–57) |

| IL-6 | Multiple | Increase glucose uptake and improve insulin sensitivity | (58, 59) |

| NRG4 | Liver | Repress de novo lipogenesis | (60) |

| PM20D1 | BAT, WAT, muscle | Increase thermogenesis | (61) |

| SLIT2-C | BAT/WAT | Induce beige adipocyte biogenesis and BAT/beige thermogenesis | (62) |

| Exosomes | Liver | Repress FGF21 expression and improve whole body glucose homeostasis | (63) |

“Multiple” connotes actions on adipocytes and other metabolic tissues such as liver, pancreas, and muscle.

Abbreviations: BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; FGF21, fibroblast growth factor 21; NO, nitric oxide; NRG4, neuregulin 4; PM20D1, peptidase M20 domain containing 1; SLIT2-C, slit homolog of extracellular protein 2 cleaved at the C-terminus; sLR11, soluble form of low-density lipoprotein receptor.

Paracrine/autocrine factors

It has been well appreciated that BAT is highly vascularized and that increased vascularization is associated with active thermogenesis (64, 65). Brown adipocytes express high levels of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), which promotes vascularization. In fact, overexpression of VEGFA in BAT activates UCP1 expression and thermogenesis (43). Conversely, adipose tissue-specific VEGFA KO mice disrupt thermogenesis in a nonobese mouse model (44), supporting the important role of vascularization for adipose thermogenesis. Another essential molecule for the regulation of blood supply is nitric oxide (NO). Cold exposure stimulates NO synthase (a key enzyme in NO synthesis) in brown adipocytes, which, in turn, enhances blood flow and thermogenesis (45).

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are also known to promote brown and beige fat differentiation and thermogenesis (66, 67). For example, BMP8b is a BMP family member that is expressed in brown adipocytes, for which expression is induced by environmental stimuli such as diet and cold exposure (46). BMP8b promotes homologues of the Drosophila protein, mothers against decapentaplegic and the Caenorhabditis elegans protein Sma (SMAD) signaling (SMAD1, SMAD5, and SMAD8) to increase p38-MAPK activation in an autocrine manner, thereby promoting brown fat thermogenesis in response to the β3-adrenergic stimulation. In addition, BMP8b acts in an endocrine manner by acting on the hypothalamus to stimulate the sympathetic nervous system (46).

Sympathetic activation promotes adipocyte lipolysis, which, in turn, fuels the mitochondria with a substrate for fatty acid oxidation (12). Intriguingly, sympathetic activation also triggers the release of signaling lipid molecules (termed lipokine) that mediate the activation of fat thermogenesis. One of the molecules that have been reported recently is 12,13-dihydroxy-9Z-octadecenoic acid (12,13-diHOME) that is released from BAT and enhances brown adipocyte thermogenesis (47). Under cold exposure, 12,13-diHOME levels are increased in mice and humans. Administration of 12,13-diHOME enhances cold tolerance and triglyceride clearance in the circulation by promoting fatty acid uptake in brown adipocytes via fatty acid transporter protein 1 (FATP1) and CD36. Another bioactive lipid compound that enhances brown and beige fat thermogenesis is prostaglandin (48, 49). Disruption of cyclooxygenase 2, a rate-limiting enzyme in prostaglandin synthesis, impairs cold-induced beige adipocyte biogenesis, whereas overexpression of cyclooxygenase 2 promotes beige adipocyte biogenesis and prevents mice from diet-induced body weight gain and glucose intolerance (48).

Several batokines that negatively regulate adipose thermogenesis as a negative feedback loop have also been identified. One is the soluble form of low-density lipoprotein receptor soluble form of low-density lipoprotein receptor (sLR11), a cold-stimulated batokine that attenuates brown fat thermogenesis in an autocrine manner (50). Endothelin-1 is also secreted from brown and beige adipocytes and inhibits adipose tissue thermogenesis by stimulating the Gq signaling (downstream of endothelin receptor1) and reducing UCP1 expression (51). In addition, endocannabinoids repress thermogenesis in response to cold exposure and β3-adrenergic receptor stimulation (52). Blockade of cannabinoid receptor-1, in turn, activates thermogenesis in brown adipocytes (53). These studies suggest a variety of batokines secreted from brown and beige adipocytes can positively or negatively control thermogenesis in a paracrine or autocrine fashion.

Endocrine factors

Although the BAT mass is much smaller than WAT, transplantation of brown fat or beige fat from mice and humans to obese mice significantly improves systemic glucose homeostasis (58, 68, 69). The metabolic improvement is, at least in part, through endocrine actions of batokines that act on peripheral metabolic organs (Table 1). Of note, many of the secreted factors are also expressed in other tissues, and no BAT-specific secretory molecule has as of yet been identified.

Fibroblast growth factor 21

Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) is an endocrine factor that is abundantly released by the liver and activates adipose thermogenesis (54). In addition to the liver, FGF21 is also secreted from BAT in response to cold exposure and β3-adrenergic receptor stimulation and contributes to the circulating FGF21 levels in mice (70). Interestingly, adipose tissue-derived FGF21 significantly contributes to the circulating levels particularly in the absence of UCP1 under a cold environment (71). Although it has been considered that FGF21 increases whole-body energy expenditure by activating UCP1-mediated thermogenesis, recent studies demonstrated that UCP1 is dispensable for the pharmacological action of FGF21 on body weight and glucose metabolism (55, 56). In contrast, FGF21 powerfully activates intracellular Ca2+ flux in adipocytes (72) and induces beige adipocyte biogenesis (57). Hence, it is conceivable that a part of the FGF21 action is to stimulate Ca2+ cycling thermogenesis in the adipose tissue. This hypothesis can be tested by examining the effect of FGF21 on adipose-specific SERCA2 KO mice.

IL-6

IL-6 is known to be a myokine derived from skeletal muscle, but also secreted from brown adipocyte. BAT-derived IL-6 plays an important role in systemic glucose homeostasis based on the study in which transplantation of BAT depots from wild-type mice, but not from IL-6 null mice, to recipient wild-type mice improves systemic glucose tolerance (58). Although metabolic analysis of BAT-specific IL-6 KO mice awaits further investigations, the data suggest a role of IL-6 from BAT as an endocrine factor in the regulation of systemic glucose homeostasis. In addition to BAT, subcutaneous WAT also secretes IL-6 (59). It has been demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition of the IκB kinase-ε and TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) signaling pathways in adipocytes of obese mice results in increased IL-6 secretion and represses hepatic gluconeogenesis (59). Interestingly, adipocyte-specific TBK1 deletion also promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and creatine-driven cycle thermogenic genes (73). Thus, TBK1 repression leads to increased IL-6 secretion and adipose tissue thermogenesis.

Neuregulin

Neuregulin 4 (NRG4) is a member of the epidermal growth factor family of extracellular ligands that is highly expressed in brown adipocytes (74). NRG4 acts on the ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases (ErbB3 and ErbB4) in hepatocytes and represses de novo lipogenesis in the liver. Importantly, gain and loss of function experiments show that NRG4 alleviates hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance in vivo (60). Because adipose tissue NRG4 expression is reduced in cases of rodent and human obesity, replacing NRG4 under an obese condition may serve as a promising approach to improving hepatic function.

Peptidase M20 domain containing 1

Peptidase M20 domain containing 1 (PM20D1) enzyme has recently been described as a secreted factor from UCP1-expressing adipocytes (61). PM20D1 catalyzes the condensation of fatty acids and amino acids into N-acyl amino acids. Overexpression of PM20D1 by tail vein injection of the adenoviral-associated virus increased the circulating levels of N-acyl amino acids, which uncouples mitochondria in a variety of tissues, including BAT and WAT, and augments whole-body energy expenditure. This action is mediated by N-acyl amino acids because administration of purified N-acyl amino acids (C18:1-Leu or C18:1-Phe) similarly stimulates mitochondrial uncoupling and increases energy expenditure. The mechanism by which N-acyl amino acids stimulate mitochondrial proton uncoupling appears to be though direct binding to mitochondrial membrane protein; however, the mechanisms driving N-acyl amino acids uptake by and subsequent binding to their target proteins in the mitochondria remain unknown.

Slit homolog of extracellular protein 2 cleaved at the C-terminus

Slit homolog of extracellular protein 2 is a 180-kDa extracellular protein family that is highly expressed in adipocytes expressing PRDM16 (62). This protein is proteolytically cleaved at the C-terminus, leading to the generation of a 50-kDa secreted peptide termed slit homolog of extracellular protein 2 cleaved at the C-terminus (SLIT2-C). Administration of SLIT2-C activates brown and beige fat thermogenesis and whole-body energy expenditure by activating the protein kinase A (PKA) signaling pathway, although its receptor remains undetermined.

Exosomes

MicroRNAs (miRNAs), small noncoding RNA molecules with 20–22 nucleotides, can be secreted from cells through microvesicles, or so-called exosomes. Brown adipocytes secrete considerable numbers of exosomes (63, 75); thus, the notion of exosome as a circulating mediator or molecular marker of brown and beige fat is an attractive hypothesis. Intriguingly, a recent study reports that BAT-derived exosomes containing miRNAs are released into circulation and act on the liver (63). miR-99b is one of the miRNAs delivered via BAT-derived exosomes and represses hepatic FGF21 expression (63). Importantly, administration of serum exosome from wild-type mice, but not from adipose tissue-specific DICER KO mice (lack miRNA production in the adipose tissue), restores FGF21 regulation in the liver. The study proposed the idea that batokines include not only polypeptides and lipid species, but also miRNAs delivered via exosomes.

Future Perspectives

Although brown and beige fat have previously been considered specialized exclusively for thermogenesis, an emerging body of evidence suggests their diverse roles in the regulation of energy balance beyond thermogenesis, including glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity in the peripheral organs, and adipose tissue remodeling (e.g., tissue fibrosis and angiogenesis). The mechanisms of such actions are diverse. Some of the aforementioned pathways are mediated through the endocrine effects of batokines, which can also embody a paracrine/autocrine functionality, mediating cell-to-cell communication within the adipose tissue. In this regard, secretory molecules released by noncanonical pathways or posttranslational cleavage of membrane-anchored proteins need to be explored in further detail. Additionally, new secretory entities such as exosomes should be further explored in the near future. Another area to be explored is to deconvolute the neuronal circuits that integrate external cues that affect adipose tissue development and function. Although the central neural circuits that target BAT have been well defined, much less is known about the neuroanatomical organization in beige fat (76). A recent study demonstrated that exposing rats to cold temperature for a week increases the percentage of neurons projecting to the brainstem (locus coeruleus) and hypothalamus (paraventricular nucleus) for both BAT and inguinal WAT depots (77). Besides anatomically reorganizing the sympathetic circuits projecting from the inguinal WAT of rats, cold-induced WAT browning has been shown to alter the neurochemical gene expression of the sympathetic ganglia innervating inguinal WAT, such that beige adipocytes adopt a gene expression profile more closely resembling that of brown adipocytes in the BAT, rather than the WAT (78). A better understanding of the neuroendocrine mechanisms may allow us to selectively target fat development and function in a depot-specific manner. These studies will also provide insights into the physiological roles of thermogenic adipocytes and also potentially lead to therapeutic interventions for the treatment of obesity and obesity-linked metabolic disorders.

Acknowledgments

We thank Zachary Brown for constructive comments on and edits to the manuscript.

Financial Support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK97441 and DK108822 and the Edward Mallinckrodt, Jr. Foundation (to S.K.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- 12,13-diHOME

12,13-dihydroxy-9Z-octadecenoic acid

- BAT

brown adipose tissue

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- FATP1

fatty acid transporter protein 1

- FGF21

fibroblast growth factor 21

- GTF2IRD1

general transcription factor II-I repeat domain-containing protein 1

- KO

knockout

- miRNA

microRNA

- MYF5

myogenic factor 5

- MYH11

myosin heavy chain 11

- NO

nitric oxide

- NRG4

neuregulin 4

- PAX7

paired box protein 7

- PDGFRα

platelet-derived growth factor receptor α

- PDGFRβ

platelet-derived growth factor receptor β

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PM20D1

peptidase M20 domain containing 1

- PRDM16

PR domain zinc finger protein 16

- RyR2

ryanodine receptor 2

- SERCA2b

sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2b

- SLIT2-C

slit homolog of extracellular protein 2 cleaved at the C-terminus

- sLR11

soluble form of low-density lipoprotein receptor

- SMA1

smooth muscle actin protein 1

- SMAD

homologues of the Drosophila protein, mothers against decapentaplegic and the Caenorhabditis elegans protein Sma

- TBK1

TANK-binding kinase 1

- UCP1

uncoupling protein 1

- VEGFA

vascular endothelial growth factor A

- WAT

white adipose tissue

References

- 1. Wang W, Seale P. Control of brown and beige fat development. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17(11):691–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kajimura S, Spiegelman BM, Seale P. Brown and beige fat: physiological Roles beyond Heat Generation. Cell Metab. 2015;22(4):546–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ikeda K, Maretich P, Kajimura S. The common and distinct features of brown and beige adipocytes. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2018;29(3):191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu J, Boström P, Sparks LM, Ye L, Choi JH, Giang AH, Khandekar M, Virtanen KA, Nuutila P, Schaart G, Huang K, Tu H, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Hoeks J, Enerbäck S, Schrauwen P, Spiegelman BM. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell. 2012;150(2):366–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shinoda K, Luijten IH, Hasegawa Y, Hong H, Sonne SB, Kim M, Xue R, Chondronikola M, Cypess AM, Tseng YH, Nedergaard J, Sidossis LS, Kajimura S. Genetic and functional characterization of clonally derived adult human brown adipocytes. Nat Med. 2015;21(4):389–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sharp LZ, Shinoda K, Ohno H, Scheel DW, Tomoda E, Ruiz L, Hu H, Wang L, Pavlova Z, Gilsanz V, Kajimura S. Human BAT possesses molecular signatures that resemble beige/brite cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e49452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lidell ME, Betz MJ, Dahlqvist Leinhard O, Heglind M, Elander L, Slawik M, Mussack T, Nilsson D, Romu T, Nuutila P, Virtanen KA, Beuschlein F, Persson A, Borga M, Enerbäck S. Evidence for two types of brown adipose tissue in humans. Nat Med. 2013;19(5):631–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yoneshiro T, Aita S, Matsushita M, Kayahara T, Kameya T, Kawai Y, Iwanaga T, Saito M. Recruited brown adipose tissue as an antiobesity agent in humans. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(8):3404–3408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van der Lans AA, Hoeks J, Brans B, Vijgen GH, Visser MG, Vosselman MJ, Hansen J, Jörgensen JA, Wu J, Mottaghy FM, Schrauwen P, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD. Cold acclimation recruits human brown fat and increases nonshivering thermogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(8):3395–3403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee P, Smith S, Linderman J, Courville AB, Brychta RJ, Dieckmann W, Werner CD, Chen KY, Celi FS. Temperature-acclimated brown adipose tissue modulates insulin sensitivity in humans. Diabetes. 2014;63(11):3686–3698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hanssen MJ, Hoeks J, Brans B, van der Lans AA, Schaart G, van den Driessche JJ, Jörgensen JA, Boekschoten MV, Hesselink MK, Havekes B, Kersten S, Mottaghy FM, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Schrauwen P. Short-term cold acclimation improves insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Med. 2015;21(8):863–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev. 2004;84(1):277–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Golozoubova V, Hohtola E, Matthias A, Jacobsson A, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Only UCP1 can mediate adaptive nonshivering thermogenesis in the cold. FASEB J. 2001;15(11):2048–2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nedergaard J, Golozoubova V, Matthias A, Asadi A, Jacobsson A, Cannon B. UCP1: the only protein able to mediate adaptive non-shivering thermogenesis and metabolic inefficiency. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1504(1):82–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ohno H, Shinoda K, Ohyama K, Sharp LZ, Kajimura S. EHMT1 controls brown adipose cell fate and thermogenesis through the PRDM16 complex. Nature. 2013;504(7478):163–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cohen P, Levy JD, Zhang Y, Frontini A, Kolodin DP, Svensson KJ, Lo JC, Zeng X, Ye L, Khandekar MJ, Wu J, Gunawardana SC, Banks AS, Camporez JP, Jurczak MJ, Kajimura S, Piston DW, Mathis D, Cinti S, Shulman GI, Seale P, Spiegelman BM. Ablation of PRDM16 and beige adipose causes metabolic dysfunction and a subcutaneous to visceral fat switch. Cell. 2014;156(1-2):304–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lowell BB, S-Susulic V, Hamann A, Lawitts JA, Himms-Hagen J, Boyer BB, Kozak LP, Flier JS. Development of obesity in transgenic mice after genetic ablation of brown adipose tissue. Nature. 1993;366(6457):740–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Feldmann HM, Golozoubova V, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. UCP1 ablation induces obesity and abolishes diet-induced thermogenesis in mice exempt from thermal stress by living at thermoneutrality. Cell Metab. 2009;9(2):203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Enerbäck S, Jacobsson A, Simpson EM, Guerra C, Yamashita H, Harper ME, Kozak LP. Mice lacking mitochondrial uncoupling protein are cold-sensitive but not obese. Nature. 1997;387(6628):90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ukropec J, Anunciado RP, Ravussin Y, Hulver MW, Kozak LP. UCP1-independent thermogenesis in white adipose tissue of cold-acclimated Ucp1-/- mice. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(42):31894–31908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bal NC, Maurya SK, Sopariwala DH, Sahoo SK, Gupta SC, Shaikh SA, Pant M, Rowland LA, Bombardier E, Goonasekera SA, Tupling AR, Molkentin JD, Periasamy M. Sarcolipin is a newly identified regulator of muscle-based thermogenesis in mammals [published correction appears in Nat Med 2012;18(12):1857]. Nat Med. 2012;18(10):1575–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ikeda K, Kang Q, Yoneshiro T, Camporez JP, Maki H, Homma M, Shinoda K, Chen Y, Lu X, Maretich P, Tajima K, Ajuwon KM, Soga T, Kajimura S. UCP1-independent signaling involving SERCA2b-mediated calcium cycling regulates beige fat thermogenesis and systemic glucose homeostasis. Nat Med. 2017;23(12):1454–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kazak L, Chouchani ET, Jedrychowski MP, Erickson BK, Shinoda K, Cohen P, Vetrivelan R, Lu GZ, Laznik-Bogoslavski D, Hasenfuss SC, Kajimura S, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM. A creatine-driven substrate cycle enhances energy expenditure and thermogenesis in beige fat. Cell. 2015;163(3):643–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kazak L, Chouchani ET, Lu GZ, Jedrychowski MP, Bare CJ, Mina AI, Kumari M, Zhang S, Vuckovic I, Laznik-Bogoslavski D, Dzeja P, Banks AS, Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. Genetic depletion of adipocyte creatine metabolism inhibits diet-induced thermogenesis and drives obesity [published correction appears in Cell Metab 2017;26(4):693].Cell Metab. 2017;26(4):660–671.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reshef L, Olswang Y, Cassuto H, Blum B, Croniger CM, Kalhan SC, Tilghman SM, Hanson RW. Glyceroneogenesis and the triglyceride/fatty acid cycle. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(33):30413–30416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Guan HP, Li Y, Jensen MV, Newgard CB, Steppan CM, Lazar MA. A futile metabolic cycle activated in adipocytes by antidiabetic agents. Nat Med. 2002;8(10):1122–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gaudry MJ, Jastroch M, Treberg JR, Hofreiter M, Paijmans JLA, Starrett J, Wales N, Signore AV, Springer MS, Campbell KL. Inactivation of thermogenic UCP1 as a historical contingency in multiple placental mammal clades. Sci Adv. 2017;3(7):e1602878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Berg F, Gustafson U, Andersson L. The uncoupling protein 1 gene (UCP1) is disrupted in the pig lineage: a genetic explanation for poor thermoregulation in piglets. PLoS Genet. 2006;2(8):e129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. What we talk about when we talk about fat. Cell. 2014;156(1-2):20–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sun K, Tordjman J, Clément K, Scherer PE. Fibrosis and adipose tissue dysfunction. Cell Metab. 2013;18(4):470–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Divoux A, Tordjman J, Lacasa D, Veyrie N, Hugol D, Aissat A, Basdevant A, Guerre-Millo M, Poitou C, Zucker JD, Bedossa P, Clément K. Fibrosis in human adipose tissue: composition, distribution, and link with lipid metabolism and fat mass loss. Diabetes. 2010;59(11):2817–2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Henegar C, Tordjman J, Achard V, Lacasa D, Cremer I, Guerre-Millo M, Poitou C, Basdevant A, Stich V, Viguerie N, Langin D, Bedossa P, Zucker JD, Clement K. Adipose tissue transcriptomic signature highlights the pathological relevance of extracellular matrix in human obesity. Genome Biol. 2008;9(1):R14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lackey DE, Burk DH, Ali MR, Mostaedi R, Smith WH, Park J, Scherer PE, Seay SA, McCoin CS, Bonaldo P, Adams SH. Contributions of adipose tissue architectural and tensile properties toward defining healthy and unhealthy obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;306(3):E233–E246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Muir LA, Neeley CK, Meyer KA, Baker NA, Brosius AM, Washabaugh AR, Varban OA, Finks JF, Zamarron BF, Flesher CG, Chang JS, DelProposto JB, Geletka L, Martinez-Santibanez G, Kaciroti N, Lumeng CN, O’Rourke RW. Adipose tissue fibrosis, hypertrophy, and hyperplasia: correlations with diabetes in human obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(3):597–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reggio S, Rouault C, Poitou C, Bichet JC, Prifti E, Bouillot JL, Rizkalla S, Lacasa D, Tordjman J, Clément K. Increased basement membrane components in adipose tissue during obesity: links with TGFβ and metabolic phenotypes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(6):2578–2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Khan T, Muise ES, Iyengar P, Wang ZV, Chandalia M, Abate N, Zhang BB, Bonaldo P, Chua S, Scherer PE. Metabolic dysregulation and adipose tissue fibrosis: role of collagen VI. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(6):1575–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hasegawa Y, Ikeda K, Chen Y, Alba DL, Stifler D, Shinoda K, Hosono T, Maretich P, Yang Y, Ishigaki Y, Chi J, Cohen P, Koliwad SK, Kajimura S. Repression of adipose tissue fibrosis through a PRDM16-GTF2IRD1 complex improves systemic glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2018;27(1):180–194.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wynn TA, Ramalingam TR. Mechanisms of fibrosis: therapeutic translation for fibrotic disease. Nat Med. 2012;18(7):1028–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Iwayama T, Steele C, Yao L, Dozmorov MG, Karamichos D, Wren JD, Olson LE. PDGFRα signaling drives adipose tissue fibrosis by targeting progenitor cell plasticity. Genes Dev. 2015;29(11):1106–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Marcelin G, Ferreira A, Liu Y, Atlan M, Aron-Wisnewsky J, Pelloux V, Botbol Y, Ambrosini M, Fradet M, Rouault C, Hénégar C, Hulot JS, Poitou C, Torcivia A, Nail-Barthelemy R, Bichet JC, Gautier EL, Clément K. A PDGFRα-mediated switch toward CD9high adipocyte pogenitors controls obesity-induced adipose tissue fibrosis. Cell Metab. 2017;25(3):673–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Keophiphath M, Achard V, Henegar C, Rouault C, Clément K, Lacasa D. Macrophage-secreted factors promote a profibrotic phenotype in human preadipocytes. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23(1):11–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Villarroya F, Cereijo R, Villarroya J, Giralt M. Brown adipose tissue as a secretory organ. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13(1):26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sun K, Kusminski CM, Luby-Phelps K, Spurgin SB, An YA, Wang QA, Holland WL, Scherer PE. Brown adipose tissue derived VEGF-A modulates cold tolerance and energy expenditure. Mol Metab. 2014;3(4):474–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mahdaviani K, Chess D, Wu Y, Shirihai O, Aprahamian TR. Autocrine effect of vascular endothelial growth factor-A is essential for mitochondrial function in brown adipocytes. Metabolism. 2016;65(1):26–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nisoli E, Tonello C, Briscini L, Carruba MO. Inducible nitric oxide synthase in rat brown adipocytes: implications for blood flow to brown adipose tissue. Endocrinology. 1997;138(2):676–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Whittle AJ, Carobbio S, Martins L, Slawik M, Hondares E, Vázquez MJ, Morgan D, Csikasz RI, Gallego R, Rodriguez-Cuenca S, Dale M, Virtue S, Villarroya F, Cannon B, Rahmouni K, López M, Vidal-Puig A. BMP8B increases brown adipose tissue thermogenesis through both central and peripheral actions. Cell. 2012;149(4):871–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lynes MD, Leiria LO, Lundh M, Bartelt A, Shamsi F, Huang TL, Takahashi H, Hirshman MF, Schlein C, Lee A, Baer LA, May FJ, Gao F, Narain NR, Chen EY, Kiebish MA, Cypess AM, Blüher M, Goodyear LJ, Hotamisligil GS, Stanford KI, Tseng YH. The cold-induced lipokine 12,13-diHOME promotes fatty acid transport into brown adipose tissue. Nat Med. 2017;23(5):631–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vegiopoulos A, Müller-Decker K, Strzoda D, Schmitt I, Chichelnitskiy E, Ostertag A, Berriel Diaz M, Rozman J, Hrabe de Angelis M, Nüsing RM, Meyer CW, Wahli W, Klingenspor M, Herzig S. Cyclooxygenase-2 controls energy homeostasis in mice by de novo recruitment of brown adipocytes. Science. 2010;328(5982):1158–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Virtue S, Feldmann H, Christian M, Tan CY, Masoodi M, Dale M, Lelliott C, Burling K, Campbell M, Eguchi N, Voshol P, Sethi JK, Parker M, Urade Y, Griffin JL, Cannon B, Vidal-Puig A. A new role for lipocalin prostaglandin d synthase in the regulation of brown adipose tissue substrate utilization. Diabetes. 2012;61(12):3139–3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Whittle AJ, Jiang M, Peirce V, Relat J, Virtue S, Ebinuma H, Fukamachi I, Yamaguchi T, Takahashi M, Murano T, Tatsuno I, Takeuchi M, Nakaseko C, Jin W, Jin Z, Campbell M, Schneider WJ, Vidal-Puig A, Bujo H. Soluble LR11/SorLA represses thermogenesis in adipose tissue and correlates with BMI in humans. Nat Commun. 2015;6(1):8951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Klepac K, Kilić A, Gnad T, Brown LM, Herrmann B, Wilderman A, Balkow A, Glöde A, Simon K, Lidell ME, Betz MJ, Enerbäck S, Wess J, Freichel M, Blüher M, König G, Kostenis E, Insel PA, Pfeifer A. The Gq signalling pathway inhibits brown and beige adipose tissue. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Krott LM, Piscitelli F, Heine M, Borrino S, Scheja L, Silvestri C, Heeren J, Di Marzo V. Endocannabinoid regulation in white and brown adipose tissue following thermogenic activation. J Lipid Res. 2016;57(3):464–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Boon MR, Kooijman S, van Dam AD, Pelgrom LR, Berbée JF, Visseren CA, van Aggele RC, van den Hoek AM, Sips HC, Lombès M, Havekes LM, Tamsma JT, Guigas B, Meijer OC, Jukema JW, Rensen PC. Peripheral cannabinoid 1 receptor blockade activates brown adipose tissue and diminishes dyslipidemia and obesity. FASEB J. 2014;28(12):5361–5375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fisher FM, Maratos-Flier E. Understanding the physiology of FGF21. Annu Rev Physiol. 2016;78(1):223–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Samms RJ, Smith DP, Cheng CC, Antonellis PP, Perfield JW II, Kharitonenkov A, Gimeno RE, Adams AC. Discrete aspects of FGF21 in vivo pharmacology do not require UCP1. Cell Reports. 2015;11(7):991–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Véniant MM, Sivits G, Helmering J, Komorowski R, Lee J, Fan W, Moyer C, Lloyd DJ. Pharmacologic effects of FGF21 are independent of the “browning” of white adipose tissue. Cell Metab. 2015;21(5):731–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fisher FM, Kleiner S, Douris N, Fox EC, Mepani RJ, Verdeguer F, Wu J, Kharitonenkov A, Flier JS, Maratos-Flier E, Spiegelman BM. FGF21 regulates PGC-1α and browning of white adipose tissues in adaptive thermogenesis. Genes Dev. 2012;26(3):271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Stanford KI, Middelbeek RJ, Townsend KL, An D, Nygaard EB, Hitchcox KM, Markan KR, Nakano K, Hirshman MF, Tseng YH, Goodyear LJ. Brown adipose tissue regulates glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(1):215–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Reilly SM, Ahmadian M, Zamarron BF, Chang L, Uhm M, Poirier B, Peng X, Krause DM, Korytnaya E, Neidert A, Liddle C, Yu RT, Lumeng CN, Oral EA, Downes M, Evans RM, Saltiel AR. A subcutaneous adipose tissue-liver signalling axis controls hepatic gluconeogenesis. Nat Commun. 2015;6(1):6047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wang GX, Zhao XY, Meng ZX, Kern M, Dietrich A, Chen Z, Cozacov Z, Zhou D, Okunade AL, Su X, Li S, Blüher M, Lin JD. The brown fat-enriched secreted factor Nrg4 preserves metabolic homeostasis through attenuation of hepatic lipogenesis. Nat Med. 2014;20(12):1436–1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Long JZ, Svensson KJ, Bateman LA, Lin H, Kamenecka T, Lokurkar IA, Lou J, Rao RR, Chang MR, Jedrychowski MP, Paulo JA, Gygi SP, Griffin PR, Nomura DK, Spiegelman BM. The secreted enzyme PM20D1 regulates lipidated amino acid uncouplers of mitochondria. Cell. 2016;166(2):424–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Svensson KJ, Long JZ, Jedrychowski MP, Cohen P, Lo JC, Serag S, Kir S, Shinoda K, Tartaglia JA, Rao RR, Chédotal A, Kajimura S, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM. A secreted Slit2 fragment regulates adipose tissue thermogenesis and metabolic function. Cell Metab. 2016;23(3):454–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Thomou T, Mori MA, Dreyfuss JM, Konishi M, Sakaguchi M, Wolfrum C, Rao TN, Winnay JN, Garcia-Martin R, Grinspoon SK, Gorden P, Kahn CR. Adipose-derived circulating miRNAs regulate gene expression in other tissues. Nature. 2017;542(7642):450–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Foster DO, Frydman ML. Tissue distribution of cold-induced thermogenesis in conscious warm- or cold-acclimated rats reevaluated from changes in tissue blood flow: the dominant role of brown adipose tissue in the replacement of shivering by nonshivering thermogenesis. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1979;57(3):257–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Orava J, Nuutila P, Lidell ME, Oikonen V, Noponen T, Viljanen T, Scheinin M, Taittonen M, Niemi T, Enerbäck S, Virtanen KA. Different metabolic responses of human brown adipose tissue to activation by cold and insulin. Cell Metab. 2011;14(2):272–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tseng YH, Kokkotou E, Schulz TJ, Huang TL, Winnay JN, Taniguchi CM, Tran TT, Suzuki R, Espinoza DO, Yamamoto Y, Ahrens MJ, Dudley AT, Norris AW, Kulkarni RN, Kahn CR. New role of bone morphogenetic protein 7 in brown adipogenesis and energy expenditure. Nature. 2008;454(7207):1000–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Qian SW, Tang Y, Li X, Liu Y, Zhang YY, Huang HY, Xue RD, Yu HY, Guo L, Gao HD, Liu Y, Sun X, Li YM, Jia WP, Tang QQ. BMP4-mediated brown fat-like changes in white adipose tissue alter glucose and energy homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(9):E798–E807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Min SY, Kady J, Nam M, Rojas-Rodriguez R, Berkenwald A, Kim JH, Noh HL, Kim JK, Cooper MP, Fitzgibbons T, Brehm MA, Corvera S. Human ‘brite/beige’ adipocytes develop from capillary networks, and their implantation improves metabolic homeostasis in mice. Nat Med. 2016;22(3):312–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tharp KM, Jha AK, Kraiczy J, Yesian A, Karateev G, Sinisi R, Dubikovskaya EA, Healy KE, Stahl A. Matrix-assisted transplantation of functional beige adipose tissue. Diabetes. 2015;64(11):3713–3724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hondares E, Iglesias R, Giralt A, Gonzalez FJ, Giralt M, Mampel T, Villarroya F. Thermogenic activation induces FGF21 expression and release in brown adipose tissue. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(15):12983–12990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Keipert S, Kutschke M, Lamp D, Brachthäuser L, Neff F, Meyer CW, Oelkrug R, Kharitonenkov A, Jastroch M. Genetic disruption of uncoupling protein 1 in mice renders brown adipose tissue a significant source of FGF21 secretion. Mol Metab. 2015;4(7):537–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Moyers JS, Shiyanova TL, Mehrbod F, Dunbar JD, Noblitt TW, Otto KA, Reifel-Miller A, Kharitonenkov A. Molecular determinants of FGF-21 activity-synergy and cross-talk with PPARgamma signaling. J Cell Physiol. 2007;210(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zhao P, Wong KI, Sun X, Reilly SM, Uhm M, Liao Z, Skorobogatko Y, Saltiel AR. TBK1 at the crossroads of inflammation and energy homeostasis in adipose tissue. Cell. 2018;172(4):731–743.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rosell M, Kaforou M, Frontini A, Okolo A, Chan YW, Nikolopoulou E, Millership S, Fenech ME, MacIntyre D, Turner JO, Moore JD, Blackburn E, Gullick WJ, Cinti S, Montana G, Parker MG, Christian M. Brown and white adipose tissues: intrinsic differences in gene expression and response to cold exposure in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;306(8):E945–E964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Chen Y, Buyel JJ, Hanssen MJ, Siegel F, Pan R, Naumann J, Schell M, van der Lans A, Schlein C, Froehlich H, Heeren J, Virtanen KA, van Marken Lichtenbelt W, Pfeifer A. Exosomal microRNA miR-92a concentration in serum reflects human brown fat activity. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bartness TJ, Ryu V. Neural control of white, beige and brown adipocytes. Int J Obes Suppl. 2015;5(Suppl 1)S35–S39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wiedmann NM, Stefanidis A, Oldfield BJ. Characterization of the central neural projections to brown, white, and beige adipose tissue. FASEB J. 2017;31(11):4879–4890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Stefanidis A, Wiedmann NM, Tyagi S, Allen AM, Watt MJ, Oldfield BJ. Insights into the neurochemical signature of the Innervation of Beige Fat. Mol Metab. 2018;11:47–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]