Abstract

To prepare for embryo implantation, the uterus must undergo a series of reciprocal interactions between the uterine epithelium and the underlying stroma, which are orchestrated by ovarian hormones. During this process, multiple signaling pathways are activated to direct cell proliferation and differentiation, which render the uterus receptive to the implanting blastocysts. One important modulator of these signaling pathways is the cell surface and extracellular matrix macromolecules, heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs). HSPGs play crucial roles in signal transduction by regulating morphogen transport and ligand binding. In this study, we examine the role of HSPG sulfation in regulating uterine receptivity by conditionally deleting the N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase (NDST) 1 gene (Ndst1) in the mouse uterus using the Pgr-Cre driver, on an Ndst2- and Ndst3-null genetic background. Although development of the female reproductive tract and subsequent ovarian function appear normal in Ndst triple-knockout females, they are infertile due to implantation defects. Embryo attachment appears to occur but the uterine epithelium at the site of implantation persists rather than disintegrates in the mutant. Uterine epithelial cells continued to proliferate past day 4 of pregnancy, accompanied by elevated Fgf2 and Fgf9 expression, whereas uterine stroma failed to undergo decidualization, as evidenced by lack of Bmp2 induction. Despite normal Indian hedgehog expression, transcripts of Ptch1 and Gli1, both components as well as targets of the hedgehog (Hh) pathway, were detected only in the subepithelial stroma, indicating altered Hh signaling in the mutant uterus. Taken together, these data implicate an essential role for HSPGs in modulating signal transduction during mouse implantation.

Conditional removal of Ndst1–3 in the uterus leads to female infertility due to implantation defects.

Embryo implantation involves complex interactions between the implanting blastocysts and the maternal uterus. Under the control of ovarian hormones [17β-estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P4)], the uterus must be prepared to receive embryos during the critical window of implantation. The uterine epithelium proliferates under the influence of preovulatory estrogen but undergoes differentiation in response to P4 production by the corpora lutea on day 2.5 postcoitum in mice. During this process, the helix-loop-helix transcription factor HAND2 functions downstream of the P4 receptor to suppress the production of several fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), which stimulate cell proliferation in the luminal epithelium (1). In addition to FGFs, other growth factor/morphogen signaling pathways, including Indian hedgehog (IHH), bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) 2, and WNT, are also important for uterine receptivity and decidualization, as genetic ablation of key components of these pathways all led to female infertility due to implantation failure (1–3).

Most, if not all, biological processes that involve spatiotemporal regulation of morphogens and growth factors require the function of heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs). HSPGs regulate cell signaling pathways by acting as receptors/coreceptors of a ligand, modulating receptor trafficking and secretion, and/or establishing signaling gradients via regulating extracellular matrix structures (4). HSPGs consist of a core protein to which glycosaminoglycan heparan sulfate (HS) chains are covalently attached. The main core proteins include syndecans and glypicans that are membrane anchored, as well as perlecan and agrin that are secreted into the extracellular matrix. Biosynthesis of HS chains requires exostosin enzymes that elongate such chains, as well as a series of modifying enzymes, among which the N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase (NDST) enzymes catalyze deacetylation and N-sulfation of the HS chains. This step is particularly important, as the locations of N-sulfate groups determine subsequent HS chain modifications by 2-O, 3-O, and 6-O sulfotransferases and C5-epimerase, which together generate the diverse ligand-specific sulfated binding sites along the HS chains. Four genes encoding NDST enzymes are present in the mouse (Ndst1, Ndst2, Ndst3, and Ndst4) that exhibit different spatiotemporal expression patterns during development. Ablation of Ndst1 causes embryonic lethality, whereas Ndst2 knockout mice are grossly normal. Conditional removal of Ndst1 and Ndst2 using tissue-specific Cre lines causes defects in lens, heart, and kidney (5–7), largely due to alternations in FGF and WNT signaling pathways.

The uterus undergoes dramatic physiological and morphological changes during peri-implantation, which are orchestrated by ovarian hormones, as well as morphogens, growth factors, and transcription factors (8, 9). Cell–cell communications through paracrine signaling are particularly important, as revealed by mouse knockout studies. However, the role of HSPG in regulating signal transduction in the peri-implantation uterus is not known. In this study, we present genetic evidence that HSPG is required during peri-implantation to promote luminal epithelial differentiation and facilitate long-range diffusion of IHH.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Generation of Ndst1f/f;2null;3null mice was described previously (10), and mutant mice were provided by Dr. Xin Zhang at Columbia University. Pgr-Cre mice (11) were provided by Dr. Francesco DeMayo at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and were mated to Ndst1f/f;2null;3null mice to produce triple heterozygotes with or without Pgr-Cre. Male Pgr-Cre;Ndst1f/f;2null;3null mice were bred to Ndst1f/f;2null;3null females to produce triple-knockout (tKO) and littermate control (CTRL) animals. Tail vein injection of Chicago Blue was described previously (12). Female mice 2 to 4 months of age were used to perform all experiments unless specified otherwise. All mice used in this study were maintained in a barrier facility at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, and experiments and procedures were performed in accordance with the institution’s regulations with an approved protocol.

Histology, immunofluorescence, and alkaline phosphatase assay

Routine histological processes and analyses were performed following protocols described previously (13). Antibodies and dilutions used were: 1:1000 for E-cadherin (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA; RRID: AB_397580), phospho–histone H3 (Millipore/Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; RRID: AB_310177), and Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA; RRIDs: AB_2534095 and AB_2534069). To assay for alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity, 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA)-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections were dewaxed, rehydrated, and washed in phosphate-buffered saline. Slides were subsequently incubated in BM purple solution (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) for color development, followed by counterstaining in nuclear fast red (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Immunoblotting

Whole uterine tissues were harvested and homogenized in RIPA buffer supplied with protease inhibitors. For HS detection using anti-HS antibody 3G10, lysates were incubated with heparinase III (Millipore/Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 1 hour. Reduced lysates were loaded onto 4% to 20% Mini-PROTEAN® precast gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and routine blotting procedures were followed to detect indicated proteins. Antibodies and dilutions used were: 1:2000 for anti–glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA; RRID: AB_561053), 1:1000 for anti-HS antibodies clone 3G10 and clone 10E4 (United States Biological, Salem, MA; RRIDs: AB_10013601 and AB_2722745), 1:5000 for horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–linked anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology; RRIDs: AB_2099233 and AB_330924). Blots were visualized by applying Immobilon Western chemiluminescent HRP substrate (Millipore/Sigma-Aldrich) and were imaged on ChemiDoc XRS+ (Bio-Rad).

RNAscope in situ hybridization

In situ hybridizations were performed on PFA-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections with RNAscope® 2.5 HD detection kit (RED) following manufacturer’s instructions (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, CA). For each gene target, custom probes that contain ∼20 DNA oligonucleotide pairs recognizing regions spanning 300 to 1000 bases of RNA were designed and purchased (Advanced Cell Diagnostics) with the exception of Ndst1 (short), which contains 15 DNA oligonucleotide pairs and covers the 677-bp floxed region of the Ndst1 gene. Briefly, dewaxed slides were washed in 100% ethanol twice and air-dried. Slides were incubated in 1× hydrogen peroxide reagent for 10 minutes at room temperature, washed with water, and then boiled in 1× target retrieval reagent for 15 minutes. After washing in distilled water, slides were dipped in 100% ethanol and air-dried overnight. After blocking in 1× protease reagent at 40°C for 30 minutes, slides were washed in distilled water and incubated in gene-specific probes for 2 hours at 40°C. Following hybridization, six amplification steps (solutions Amp 1 to 6) were performed to amplify and visualize the signal. Slides were baked dry and mounted in Permount (Sigma-Aldrich) for imaging.

Separation and isolation of uterine epithelial and stromal cells

Fresh mouse uterine tissues were dissected, rinsed briefly in cold Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS; calcium- and magnesium-free), and cut into 3- to 4-mm pieces. Tissue fragments were digested in 1% trypsin (Millipore/Sigma-Aldrich) in HBSS on a shaking platform for 1.5 hours at 4°C and then 30 minutes at room temperature. The enzymatic digestion was stopped by adding an equal volume of 5 mg/mL bovine serum albumin in HBSS. Uterine epithelia were extruded by gently squeezing the tissue fragments longitudinally with a pair of tweezers, while holding one end, and collected into an Eppendorf tube by pipetting. Pooled epithelial cells were washed with cold HBSS and spun down. Remaining uterine tissues were transferred to a fresh tube and digested in 0.25% trypsin, 0.5 to 1 mg/mL collagenase (Millipore/Sigma-Aldrich) in HBSS on a shaking platform for 30 minutes at 37°C. Stromal cells were released from tissue remnants by vigorous pipetting and collected by passing through 100µm nylon filters followed by centrifugation.

Artificial decidualization

Female CTRL and tKO mice were ovariectomized and allowed to rest for 2 weeks. These mice then received three daily injections of 100 ng of E2 (Sigma-Aldrich), followed by 2 days of rest, then three daily injections of 6.7 ng of E2 plus 1 mg of P4 (Sigma-Aldrich). Six hours after the last injection, one uterine horn received 20 µL of sesame oil, whereas the contralateral uterine horn served as control. Mice continued to receive daily E2 plus P4 treatment for another 4 days, when they were euthanized and their uterine tissue assessed for decidualization. Uterine horns were weighed and the ratio of decidua/control uterine horns of the same animal was calculated. Tissues were then fixed in 4% PFA for subsequent AP assay.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Whole blood was collected by cardiac puncture into 1.5-mL Eppendorf tubes and incubated undisturbed at room temperature for 20 minutes. Following centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C, supernatant (serum) was aliquoted and stored at −80°C until assay. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits for detection of E2 and P4 were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI), and manufacturer’s instructions were followed to determine serum level of hormones.

RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcription PCR

Total RNA was isolated from uterine tissue or isolated uterine cell pellets with RNA Stat-60 (Tel-Test, Friendswood, TX) following manufacturer’s instructions. Primer design and reverse transcription followed by quantitative PCR were performed as previously described (14). Student t test was performed on biological triplicates, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

NDSTs are present in normal adult uterus

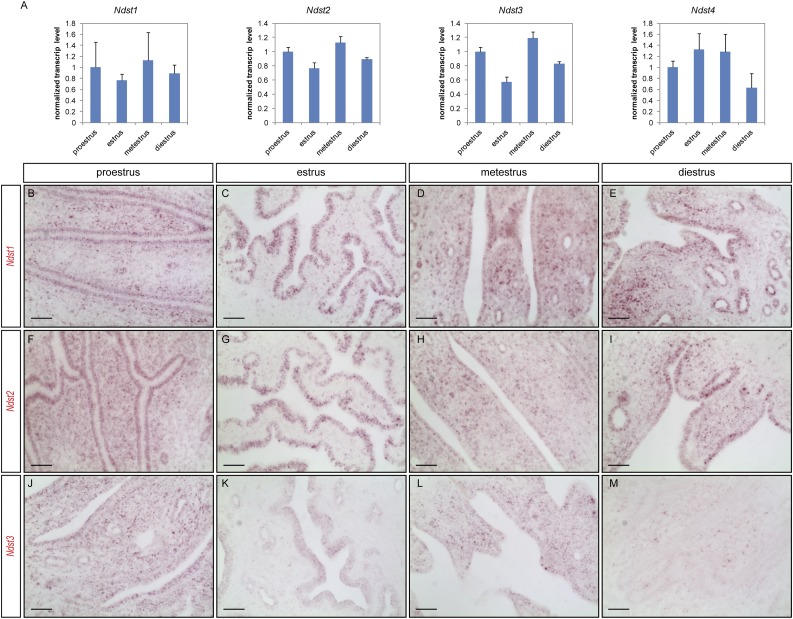

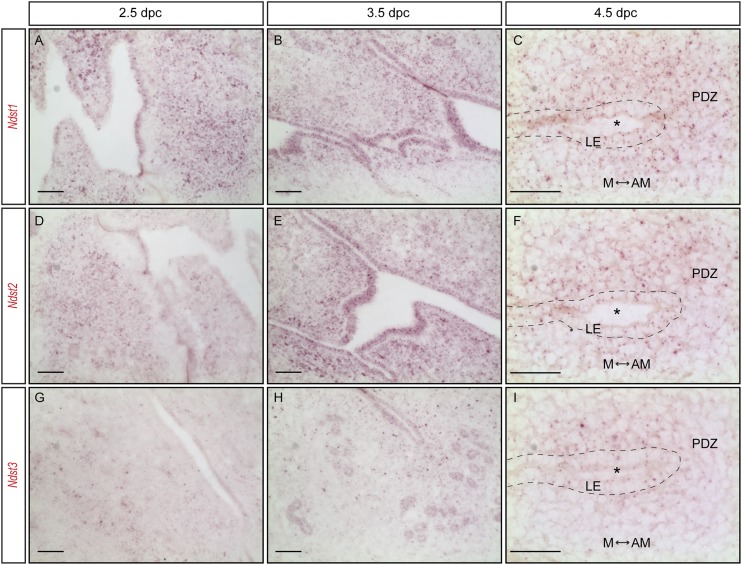

To investigate the potential roles of NDST enzymes in female reproduction, we first determined Ndst gene expressions in adult mouse uterus. As shown in Fig. 1A, real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) detected all four Ndst genes in the uterus, during each estrous stage. Despite minor fluctuations, no significant changes in gene expression were detected for all four genes throughout the estrous cycle. Next, we performed branched DNA method–based RNAscope in situ hybridization to determine the tissue distribution of Ndst1, Ndst2, and Ndst3 using commercially available gene-specific Z-probes and detection kit. As shown in Fig. 1B–1E, in adult wild-type uteri, Ndst1 was primarily detected in the uterine epithelium as well as the underlying stromal cells in proestrus, metestrus, and diestrus. In estrus, however, Ndst1 transcripts were primarily detected in the uterine epithelium (Fig. 1C). A very similar expression pattern was found for Ndst2 (Fig. 1F–1I). Ndst3, however, was detected at a much lower level (Fig. 1J–1M). Prior to and during implantation [2.5 to 4.5 days postcoitum (dpc)], the mouse uterus continues to express Ndst1 and Ndst2 at fairly high levels both in the uterine epithelium and in the stroma, including the primary decidual zone (Fig. 2A–2F), with Ndst3 at a lower level (Fig. 2G–2I). These data demonstrate that the NDST enzymes are present in the adult mouse uterus and during the implantation window.

Figure 1.

Ndst genes are expressed in adult uterus. (A) Expressions of all four Ndst genes were detected in 2-month-old adult wild-type mouse uterus by RT-qPCR, in various stages of the estrous cycle. Estrous cycle stages were determined by cytological analysis of vaginal smear at the time of dissection. (B–M) Transcripts of Ndst1, Ndst2, and Ndst3 were detected in adult uterus by RNAscope in situ hybridization (red). Ndst1 transcripts are present primarily in the luminal epithelium and underlying mesenchymal cells at (B) proestrus, (D) metestrus, and (E) diestrus. (C) Elevated level of Ndst1 transcripts was noticed in the epithelium at estrus. (F–I) Similar expression pattern and level was observed for Ndst2. (J–M) Ndst3 transcripts were detected at a much lower level. Scale bars, 50 µm.

Figure 2.

Ndst genes are expressed in the uterus around the time of implantation. (A–I) RNAscope in situ hybridization (red) showed Ndst1, Ndst2, and Ndst3 transcripts in the uterus at 2.5, 3.5 (longitudinal section), and 4.5 dpc (cross-section). The asterisk indicates the implantation chamber. AM, antimesometrial; LE, luminal epithelium; M, mesometrial; PDZ, primary decidualization zone. Scale bars, 50 µm.

Genetic ablation of Ndst1, Ndst2, and Ndst3 in Pgr-expressing lineages leads to female infertility

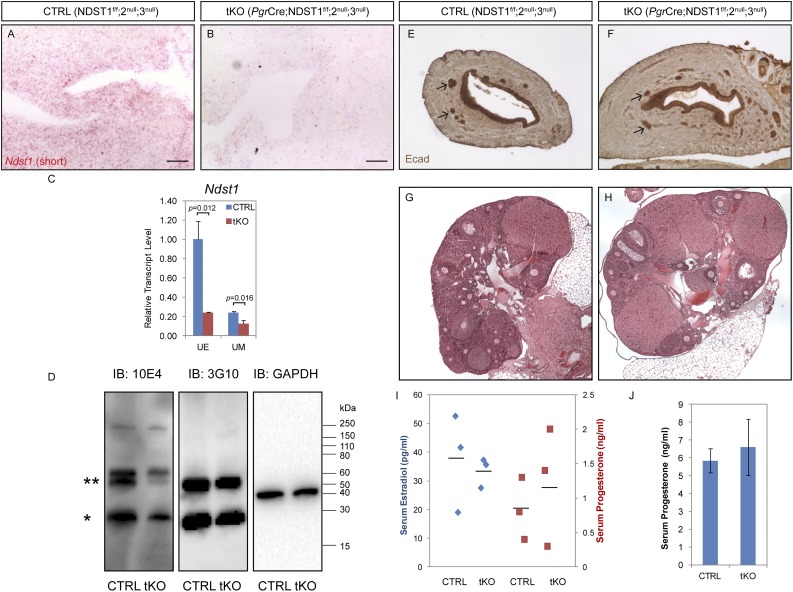

Although Ndst2 and Ndst3 are both expressed in the adult uterus, Ndst2 and Ndst3 double-null mice are grossly normal and fertile. Because NDST1 has been shown to be crucial for many organogenesis processes, we generated Pgr-Cre;Ndst1f/f;2null;3null (hereafter referred to as tKO) compound mutants in which Ndst1, Ndst2, and Ndst3 were all deleted in the Pgr-expressing female reproductive organs. To assess Ndst1 deletion efficiency by the Pgr-Cre, RNAscope in situ hybridization was performed using probes targeting the 677-bp floxed region of Ndst1. These probes revealed that Ndst1 transcripts were dramatically reduced in tKO mutant uterus (Fig. 3A and 3B). Quantification by qRT-PCR revealed that Ndst1 transcripts were significantly reduced by 81.3% and 46.6% in the tKO uterine epithelium and stroma, respectively (Fig. 3C). To determine whether deleting all three Ndst genes in the uterus leads to changes in HSPG sulfation, we performed immunoblotting on uterine tissue extracts using the anti-HS epitope 10E4 antibody that detects N-acetylated/N-sulfated HSPGs. Markedly reduced levels of sulfated proteoglycans, with molecular masses corresponding to syndecan (Fig. 3D, asterisk) and glypicans (Fig. 3D, double asterisks), were observed in the tKO uterine lysates. This reduction reflects differences in HSPG sulfation rather than total proteoglycan abundance, as western blotting using the anti-HS epitope 3G10 antibody which detects neo-HS stubs on heparinase III–digested uterine lysate showed no difference between the two genotypes (Fig. 3D). Loss of NDSTs did not appear to cause any obvious defect in female reproductive organs, as immunohistochemistry against E-cadherin outlining luminal as well as glandular epithelia showed normal uterine structure in tKO mutants (Fig. 3E and 3F). Likewise, the tKO ovary appeared normal in size and gross morphology, where follicles of various stages and corpus luteum were all present (Fig. 3G and 3H). Because one major function of the ovary is to produce ovarian hormones, we measured serum levels of P4 and estrogen in nonpregnant age-matched CTRL (Ndst1f/f;2null;3null) and tKO mice. Fig. 3I shows that both hormones were detected in tKO females, with a range comparable to those in CTRL females. Because these mice were euthanized at random stages of the estrous cycle, fluctuations in hormone levels were expected. Serum P4 level was also measured at 3.5 dpc to ensure normal ovarian function, and no significant difference was detected in the tKO mice (Fig. 3J). These data collectively demonstrate that the NDST1, NDST2, and NDST3 enzymes are not required for postnatal female reproductive organ development.

Figure 3.

Pgr-Cre–mediated Ndst1 ablation on Ndst2/Ndst3 double-null genetic background does not affect uterine development and ovarian function. (A and B) RNAscope in situ hybridization of Ndst1 using a short probe detecting the floxed region of the transcript showed marked reduction of the transcript in the tKO uterus. (C) qRT-PCR of Ndst1 showing reduction in both uterine epithelium (UE; relative level 1.000 ± 0.190 in CTRL vs 0.019 ± 0.005 in tKO, n = 3, P = 0.012) and uterine stroma (UM; 0.241 ± 0.012 in CTRL vs 0.129 ± 0.031 in tKO, n = 3, P = 0.016). (D) Immunoblotting (IB) of whole uterine lysates detecting HSPGs. GAPDH was used as loading control. Lysates digested with heparinase III was blotted with an anti-HS 3G10 antibody to detect HS stubs of proteoglycans. Anti-HS mAb 10E4 detects N-acetylated/N-sulfated HSPGs. An asterisk indicates syndecans (22 to 30 kDa) presumably, whereas double asterisks indicate glypicans (∼60 kDa). (E and F) Expression of E-cadherin immunohistochemistry of P22 uterine sections showing normal appearance of adult tKO animals. Arrows point to uterine glands. (G and H) Stitched H&E images of CTRL and tKO ovaries, showing presence of follicles of various stages as well as luteal bodies, regardless of genotype. (I and J) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay shows comparable serum levels of E2 and P4 in cycling females and during peri-implantation of CTRL and tKO mice (cycling E2, 37.7 ± 17.1 in CTRL vs 33.4 ± 5.2 pg/mL in tKO, n = 3, P = 0.70; cycling P4, 0.8 ± 0.4 in CTRL vs 1.2 ± 0.8 ng/mL in tKO, n = 3, P = 0.52; P4 at 3.5 dpc, 5.8 ± 0.7 in CTRL vs 6.6 ± 1.6 ng/mL in tKO, n = 4, P = 0.41). Scale bars, 50 µm.

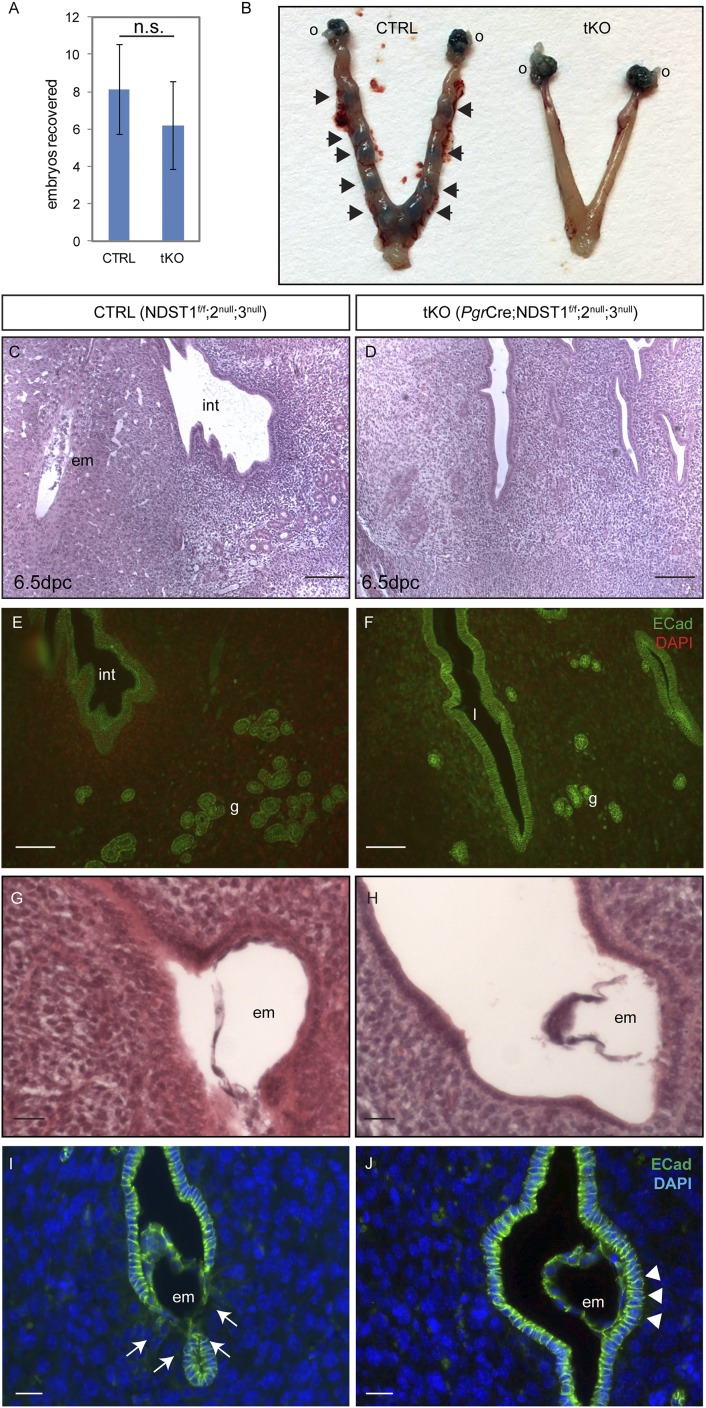

Despite normal morphology of their reproductive organs, tKO females present a complete infertile phenotype (Table 1); no pups were ever produced by the tKO females in spite of vaginal plugs. We therefore examined early stages of pregnancy in these animals to determine the cause of infertility. Quantification of embryos was first performed to confirm successful ovulation by flushing the oviducts of 3.5 dpc female mice and no significant difference was noted in the number of embryos recovered (Fig. 4A). Increased vascular permeability is an early sign of successful implantation, which can be visualized via tail vein injection of Chicago blue dye (15). As shown in Fig. 4B, distinct blue uterine segments indicative of regions where implantation is taking place were detected along the uterine horns of CTRL mice at 4.5 dpc (arrows), but were absent in the tKO uteri. Histological analyses of the pregnant uterus at 6.5 dpc revealed embedded embryos, disintegration of the surrounding uterine epithelium, and enlarged polygonal decidual cells in CTRL mice (Fig. 4C). In contrast, 6.5 dpc tKO uterine tissue displayed normal nonpregnant appearance, with intact epithelium and regularly shaped stromal cells (Fig. 4D). Immunofluorescent staining of E-cadherin further demonstrated that the decidua in CTRL 6.5 dpc uterus pushed uterine glands toward the surrounding myometrium (Fig. 4E), whereas lack of decidualization reaction in the tKO uteri resulted in an even distribution of glands throughout the stroma (Fig. 4F). These results suggest that the infertility phenotype in Ndst tKO females results from an implantation defect.

Table 1.

Fertility Test of Ndst tKO Females and Their Littermate CTRLs During a Period of 2 Months

| Males (n) | Females (n) | No. Vaginal Plugs Observed | No. Litters | No. Pups | Average Litter Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pgr-Cre;Ndst1f/f;2null;3null (2) | Pgr-Cre;Ndst1f/f;2null;3null (7) | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Pgr-Cre;Ndst1f/f;2null;3null (2) | Ndst1 f/f ;2 null ;3 null (6) | 11 | 11 | 73 | 6.6 |

Females of both genotypes were mated with tKO males, which do not present any fertility phenotype. Copulation was scored by the presence of vaginal plug, and subsequent number of litters/pups was recorded. The tKO females were unable to produce any pups, despite the presence of vaginal plugs, suggesting that they are infertile [0.0 ± 0.0 (n = 7 in tKO) vs 6.6 ± 0.9 (n = 6 in CTRL); P = 6.3 × 10−19].

Figure 4.

Fertility defects in tKO females are due to implantation failure. (A) Embryo recovery assay was performed and revealed no statistically significant difference between the genotypes (8.14 ± 2.34 vs 6.20 ± 2.39, n = 7 in CTRL and n = 5 in tKO, P = 0.19). n.s., not significant. (B) Implantation sites at 4.5 dpc visualized by tail vein injection of Chicago blue dye solution were present in CTRL mice (arrows), but absent in tKO animals. (C and D) H&E staining of CTRL and tKO uteri at 6.5 dpc. (E and F) E-cadherin immunofluorescence of adjacent sections as shown in (C) and (D). Note that the decidua in CTRL uterus pushes the glands to the peripheral regions of the endometrium, whereas those in tKO uterus are distributed evenly throughout the mesenchyme. (G and H) H&E staining of 4.5 dpc uteri from CTRL and tKO both show the presence of embryos in the uterine lumen, attaching to the uterine epithelia. Note that uterine lumenal closure is evident in CTRL, but not in the tKO uterus. (I and J) Immunofluorescence against E-cadherin shows its disappearance around the embedding embryo in CTRL uterus [arrows in (I)], indicating successful epithelial remodeling. On the contrary, its expression remains intact in tKO uterine epithelium where embryo attaches [arrowheads in (J)]. Scale bars, 50 µm in (C)–(F), 20 µm in (G)–(J). DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; g, glands; em, embryo; int, interimplantation site; l, lumen; o, ovary.

Examination of longitudinal uterine sections at 4.5 dpc by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed blastocysts in both CTRL and tKO uteri, indicating successful ovulation, fertilization, and oviductal–uterine transport regardless of genotype (Fig. 4G and 4H). However, luminal closure along the mesometrial–antimesometrial axis, a key step in immobilizing embryos for implantation at the antimesometrial side of the uterus, was evident only in the CTRL but not the tKO uterus (Fig. 4G and 4H). Intriguingly, immunofluorescent staining against E-cadherin further revealed that at 4.5 dpc, CTRL uterine epithelium already started to downregulate E-cadherin expression upon embryo attachment (Fig. 4I, arrows), a sign of epithelial disintegration (16). In the tKO uterus, however, E-cadherin expression persists at the same high level in the uterine epithelium even at sites of embryo contact, showing no sign of disintegration (Fig. 4J, arrowheads). It is noteworthy that the infertility phenotype was only observed in the tKO females, but not in Pgr-Cre;Ndst1f/f females carrying one or more wild-type alleles for both Ndst2 and Ndst3 (data not shown), indicating functional compensation among NDST family members. These results collectively demonstrate that Pgr-Cre–mediated deletion of Ndst1 on Ndst2- and Ndst3-null genetic background leads to female infertility due to compromised uterine receptivity, without interfering with normal ovarian and oviductal functions.

Altered cellular proliferation and gene expression in the Ndst tKO uterus

During peri-implantation, the uterus must undergo a series of molecular and cellular changes in both the epithelial and stromal compartments to render itself receptive to the implanting blastocysts. One hallmark of these changes is the cessation of uterine epithelial proliferation at ∼3.5 dpc in preparation for rapid morphological remodeling during P4-controlled embryo embedding. In contrast, the underlying stromal cells undergo extensive proliferation to prime for decidualization under the coordinated control of P4 and estrogen (17, 18). As shown in Fig. 5A, immunofluorescent staining against phospho–histone H3, a protein only present at the mitotic phase of an actively proliferating cell, was detected primarily in the stromal cells of the CTRL 3.5 dpc uterus (arrows), but not in the receptive epithelium (outlined by a dotted line). In contrast, proliferating cells were mostly confined to the luminal epithelium of the 3.5 dpc tKO uterus (Fig. 5B, arrowheads), with sporadic staining in the underlying stroma. This abnormal proliferation is unlikely to result from aberrant hormonal regulation, because comparable serum P4 level (Fig. 3J) and normal estrogen receptor and P4 receptor levels were detected in these animals (data not shown). These results indicate that without the NDST enzymes, the uterus is not properly prepared and is not receptive for the implanting blastocysts.

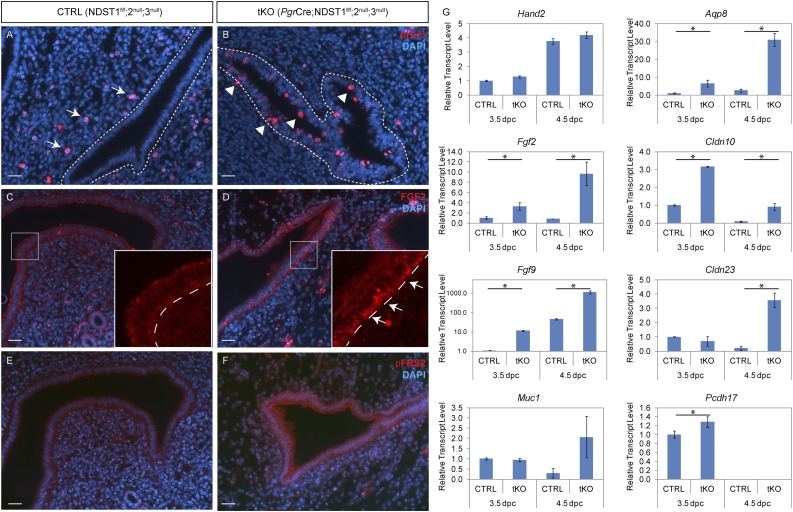

Figure 5.

Early implantation failure in tKO uterus is accompanied by cell cycle and signaling disruption. (A and B) Immunofluorescence against phospho-histone H3 (pHH3) shows that uterine epithelial cells cease to proliferate at 3.5 dpc in CTRLs but continue to proliferate in tKOs [arrowheads in (B)], indicating failure of uterine receptivity in the latter. Note that many mesenchymal cells proliferate in CTRL uterus [arrows in (A)] but few were detected in tKO stroma. (C–F) Immunofluorescence of (C and D) FGF2 and (E and F) phospho–FGF receptor substrate 2 (pFRS2) shows an increase in FGF signaling activities in the absence of NDSTs. Note the accumulation of FGF2 protein in the basolateral side of the uterine epithelium at 3.5 dpc [arrows, inset in (D)] and (F) an overall increase of pFRS2 in the uterine epithelium. (G) Real-time quantitative PCR of a panel of genes involved in early implantation. *P < 0.05 (n ≥ 3). Scale bars, 20 µm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

FGF family members and their signaling cascades modulate the cellular processes of proliferation and differentiation via autocrine and/or paracrine pathways. Specifically, FGF2 has been reported to be involved in uterine function during normal estrous cycle as well as pregnancy by regulating epithelial proliferation and migration, angiogenesis, and endometrial receptivity in many species (19–22). In mice lacking Hand2, a P4-responsive critical regulator of uterine proliferation and decidualization, implantation fails to occur because of persistent epithelial proliferation during the window of implantation. Fgf2 transcript levels were elevated, and FGF signaling was augmented in Hand2 mutant uterine epithelium (1). Even though no significant changes were detected in Hand2 expression in tKO females, marked increases in Fgf2 and Fgf9 expression were noted during peri-implantation (Fig. 5G). Immunofluorescence of FGF2 revealed a fairly even distribution of the protein in the luminal and glandular epithelia as well as the stroma of the CTRL uterus at 3.5 dpc (Fig. 5C). Intriguingly, accumulation of FGF2 protein was prominent in the basolateral cytoplasm of the tKO luminal epithelial cells (Fig. 5D, arrows). Consistently, tyrosine phosphorylation of FGF receptor substrate 2 was observed in these cells (Fig. 5F), indicating ectopic FGF signaling activation in the absence of NDST enzymes during the peri-implantation period, which may have directly led to persistent epithelial proliferation.

Additionally, a panel of genes previously reported to be regulated by E2 or P4 and involved in the establishment of implantation were analyzed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 5G). E2-responsive mucin 1, whose expression is attenuated during peri-implantation to prepare the uterus for embryo attachment (23, 24), was not properly downregulated in the tKO uterus. Aquaporin (Aqp)8, a water channel–encoding gene previously reported to be primarily present in blastocysts (25), exhibited elevated transcript level in the tKO uterus. Claudins Cldn10 and Cldn23, genes encoding tight junction proteins that normally regulate paracellular permeability, cell signaling, and subsequent proliferation and differentiation, were also deregulated in the tKO uterus. Elevation of these genes’ expression could result in failure in epithelial breakdown and reduced vascular permeability. Increased transcript levels of protocadherin 17, a gene regulating cytoskeletal dynamics (26), was also noted. Taken together, these results suggest that HS biosynthesis is essential to maintain the expression of a wide array of genes regulating implantation.

Signal transduction defects in the Ndst tKO uterus

Many evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways are active and involved in the process of implantation. Disruption of these signal transduction cascades via altered HS chain modifications could be one underlying molecular mechanism that leads to decidualization failure and eventual infertility. To test this hypothesis, in situ hybridization was performed to examine some key components of the hedgehog and BMP pathways. Lee et al. (3) previously reported that Ihh is induced in the uterine epithelium during the peri-implantation period under the control of P4 and activates its downstream signal cascades only in the underlying stroma in a paracrine manner. Ablation of Ihh by Pgr-Cre resulted in female infertility due to failed decidualization and uterine vascularization, a phenotype very similar to that of the Ndst tKOs. In situ hybridization revealed comparable Ihh transcript levels in 3.5 dpc uterine epithelia of tKO mutants and CTRLs (Fig. 6A and 6B), indicating that the mutant epithelium is responsive to P4 induction. Expression of the transmembrane Hh receptor patched 1 (Ptch1) and the transcription factor Gli1, often used as readouts of Hh signaling, were also examined.

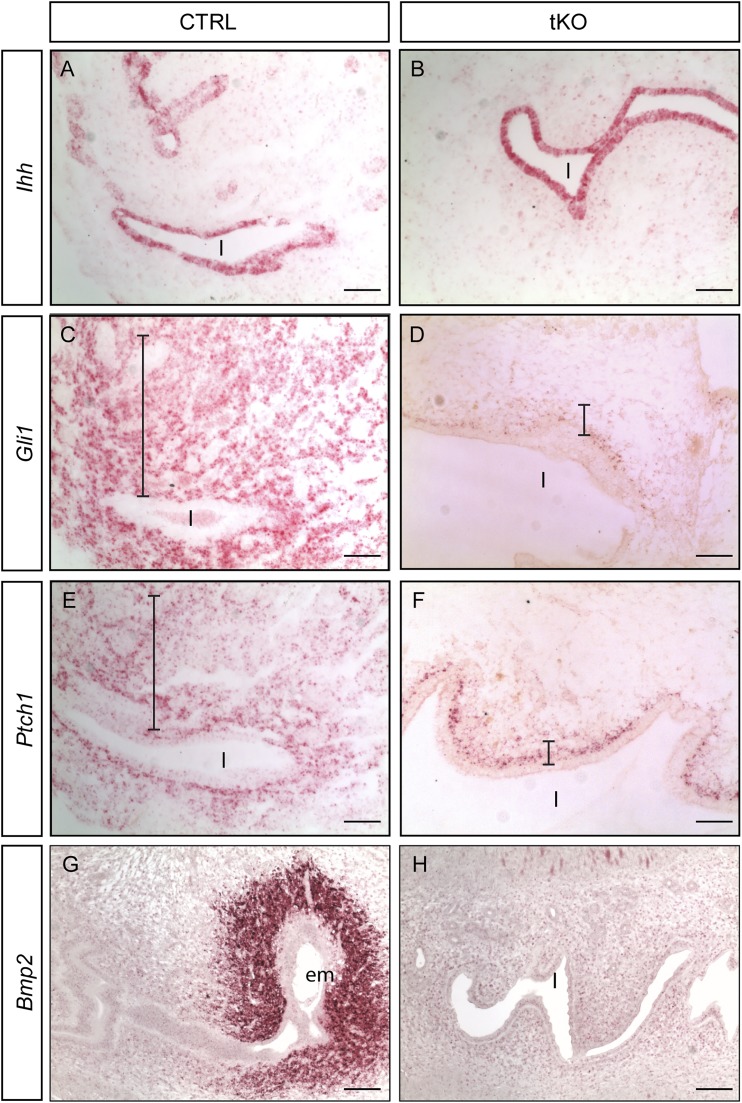

Figure 6.

RNAscope in situ hybridization of selected genes. (A and B) At 3.5 dpc, comparable levels of Ihh, were detected in tKO uterus; however, distribution of Gli1 and Ptch1 is altered in the absence of NDST isoenzymes. (C and E) Both transcripts are evenly expressed in CTRL stroma, (D and F) whereas they were detected only in the subepithelial stroma of tKO uterus. Signals are red. Bars indicate the distribution depth of the detected transcripts. (G) At 4.5 dpc, Bmp2 is drastically induced in the mesenchyme surrounding the implanting embryo but not in the mesenchyme of interimplantation sites. (H) In contrast, no Bmp2 elevation is ever observed in tKO uterus. Scale bars, 50 µm. em, embryo; l, lumen.

Even though both were expressed in the tKOs at 3.5 dpc, their expressions were mostly confined to the subepithelial stroma (Fig. 6D and 6F), unlike the CTRL uterus where expression was more widespread and detected in stromal cells farther away from the epithelium (Fig. 6C and 6E). Bmp2 has also been shown to be indispensable for decidualization, and removal of the gene by Pgr-Cre leads to female infertility (27). Bmp2 is absent in the preimplantation uterus, but is upregulated in the stroma surrounding the embedding blastocyst, under the control of IHH and leukemia inhibitory factor signaling (27). In situ hybridization showed that Bmp2 failed to be induced in the tKO stroma at 4.5 dpc (Fig. 6G and 6H). These results indicate that even though IHH is induced in the tKO uterine epithelium, its ability to signal long range is impaired in the stroma due to altered sulfation status of HSPGs in the absence of NDST enzymes.

Decidualization failure in the Ndst tKO uteri

Absence of Chicago blue dye reaction in the tKO uteri at 4.5 dpc (Fig. 4B) and lack of large polygonal decidual cells at 6.5 dpc (Fig. 4D) led us to suspect that decidualization also failed to occur in the tKO animals. To test this, we examined activity of AP, a hallmark isoenzyme that is specifically expressed in the decidua. As expected, 5.5 dpc CTRL uterine stroma showed robust AP activity in the decidual cells (Fig. 7A). In contrast, AP activity in tKO uteri was virtually absent (Fig. 7B), which confirmed decidualization failure in the mutants.

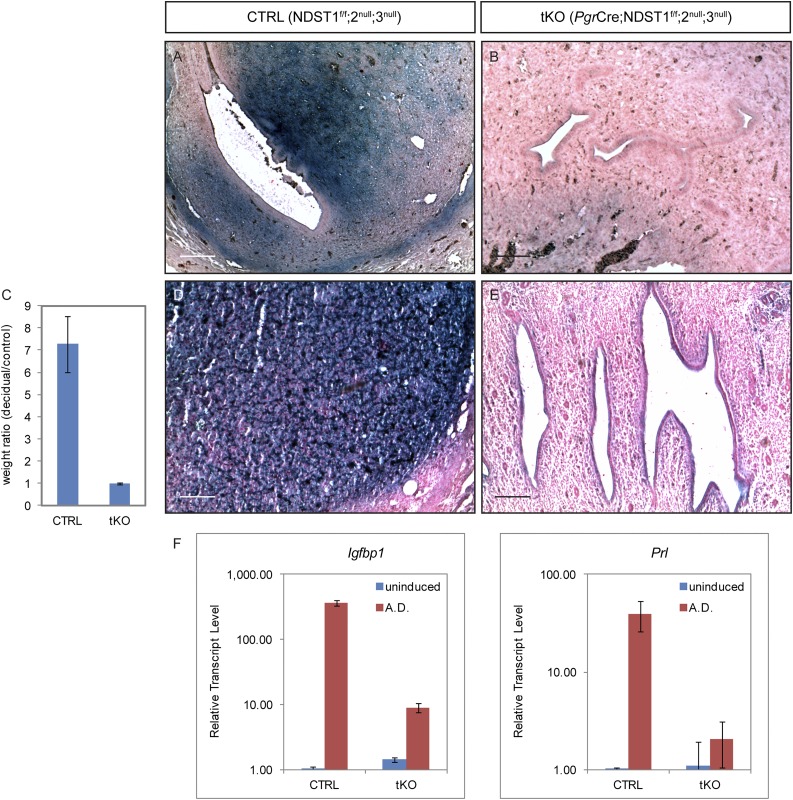

Figure 7.

Female infertility in the Pgr-Cre;Ndst1,2,3 tKO is partially caused by decidualization defects during implantation. (A and B) AP activity, an indicator of decidualization, is evident in CTRL uterine stroma at 5.5 dpc, whereas very little, if any, AP activity was detected in the tKO uterus. (C) Artificial decidualization is achieved in CTRL mice, demonstrated by markedly increased uterine weight in the induced uterine horn, but not in the tKO mice (induced/uninduced contralateral horn weight ratio, 7.27 ± 1.27 vs 0.99 ± 0.06; n = 3; P = 0.001). (D and E) AP activity of the artificial decidua in (D) CTRL and (E) tKO uteri. (F) Real-time RT-PCR shows that induction of two decidualization markers, Igfbp1 and Prl, was markedly dampened in the tKO artificial decidua. Note that the transcript level is on logarithmic scale. Scale bars, 50 µm.

As successful decidualization during normal pregnancy requires embryo attachment, uterine receptivity, and tight regulation of ovarian hormones, failure in decidualization could be the result of defects in one or more of these aspects. To rule out the potential involvement of defective embryo attachment and/or hormone regulation, we performed an artificial decidualization assay to focus on uterine receptivity alone. When exogenous hormones are provided to ovariectomized CTRL females and trauma is introduced to a uterine horn, it undergoes rapid proliferation and differentiation that mimics the natural decidualization process. As expected, a marked increase in uterine weight compared with the unstimulated uterine horn was evident in CTRL animals, but not in the tKO mice (Fig. 7C; induced/uninduced contralateral horn weight ratio, 7.27 ± 1.27 in CTRL vs 0.99 ± 0.06 in tKO, n = 3, P = 0.001). Substantial AP staining was detected in the artificial decidua of CTRL uterine stroma (Fig. 7D), whereas little was seen in the tKO uteri (Fig. 7E). Furthermore, Igfbp1 and Prl, two genes that are rapidly upregulated in decidual cells, failed to be induced in the tKO uterus upon stimulation (Fig. 7F). Taken together, these data demonstrate that decidualization failure in Ndst tKO mice may also contribute to the observed female infertility phenotype.

Discussion

The existence and role of ligand–receptor signaling mechanisms operating in the peri-implantation uterus have been extensively studied (28). It is primarily controlled by ovarian hormones E2 and P4, coordinated ligand expression, and subsequent pathway activation, which together prime the uterus for embryo implantation. Oftentimes the signal transduction is conducted in a paracrine manner, where the ligand expressed in the luminal epithelium travels to and activates receptors on the stromal cells, or vice versa. One such example is IHH, which is exclusively induced in the uterine epithelium by P4 during early pregnancy and exerts its function in many layers of underlying stromal cells (29). Transportation of and receptor interaction with the ligands, many facilitated through binding to HS, are therefore crucial for subsequent signaling cascade activation in target cells. In this study, we genetically abolished three HS GlcNAc NDST genes specifically in the female reproductive organs, and showed that reduction in the level of sulfation of HS chains rendered females infertile.

We have previously performed global gene profiling on neonatal mouse uterine tissues and discovered that out of the four Ndst genes, Ndst1 and Ndst2 were highly expressed in both the epithelial and stromal compartments of the uterus at postnatal day 5, whereas Ndst3 and Ndst4 were not expressed (30) (Gene Expression Omnibus accession no. GSE37969). In the present study, we detected strong ubiquitous Ndst1 and Ndst2 expression and weaker Ndst3 expression in adult uterus. These expression patterns continue throughout the peri-implantation period. Despite their expression in the uterus, Ndst2-null and Ndst2/Ndst3-null mice are developmentally normal and fertile (31). Only when Ndst1 was ablated in Pgr-expressing cells on the Ndst2/Ndst3-null genetic background did it affect female reproduction. Similarly, deleting Ndst1 alone in Pgr-expressing cells does not lead to infertility, indicating functional redundancy among NDST enzymes during peri-implantation.

The fact that ovarian hormone levels and ovulation appeared normal and blastocysts were present in 3.5 dpc tKO uterine lumen indicates that fertilization and early embryogenesis were unaffected by Ndst mutations. The first observed phenotype is luminal closure, a process thought to precede embryo attachment. The mechanisms underlying luminal closure are not clear. Many think that uterine glands switch between secretory and absorptive functions to regulate uterine fluid volume under P4 control (32). There is also the hypothesis of luminal epithelium adjusting its absorptivity through the expression of pinopodes present on the apical surface (33, 34). A recent study suggested that increased expression of two aquaporin water channel genes (Aqp5 and Aqp8) causes excessive intraluminal fluid accumulation, which is the major contributor to aberrant implantation in mice treated with supraphysiological doses of E2 (35). Intriguingly, elevated levels of Aqp8 expression were detected in tKO uteri on both 3.5 and 4.5 dpc (Fig. 5). This finding is consistent with a role of Aqp8 in luminal closure and could directly lead to the luminal closure defect observed in the tKO uterus.

Involvement of HSPG in FGF signaling has been extensively studied. In Drosophila, mutations in genes sugarless and sulfateless, which encode homologs of UDP-d-glucose dehydrogenase and NDSTs, respectively, caused similar phenotypes as those in Drosophila FGF receptor homolog mutants, heartless and breathless (36). Additionally, introduction of a constitutively active form of heartless into the sugarless and sulfateless mutants partially rescued their phenotypes. Biochemical studies have revealed distinct HS binding sites on both FGF ligands and receptors, suggesting that they form a ternary complex with HSPGs (37–39). During the peri-implantation period, P4 induces expression of the transcription factor Hand2 in the subepithelial stroma cells, which in turn suppresses the production of several FGF ligands by the epithelia via an unknown mechanism (1). Ectopic FGF signaling activity in Hand2 mutants was accompanied by sustained epithelial proliferation, which led to implantation failure. In our Ndst tKO mice, despite a compromised luminal closure in the tKO uterus, some embryos managed to adhere to the luminal epithelium (Fig. 4). However, ectopically induced FGF signaling in the tKO luminal epithelium with extensive cell proliferation well into the implantation window prevented proper differentiation of uterine epithelium and implantation progression. This ectopic activation of FGF signaling is not mediated through Hand2, as its expression was not significantly changed in the mutant uterus. Given that Hand2 is likely directly regulated by P4, and that Ndst mutations do not affect ovarian hormone production, it is not surprising that Hand2 expression remains unchanged. Our data support the model that Ndsts are either downstream of Hand2 or function in a Hand2-independent regulatory axis in the receptive uterus to modulate its proliferation and differentiation.

Another finding of our study is that HSPGs likely facilitate IHH signaling across the uterine stroma, as Ndst mutations attenuate the extent of signaling transduction (Fig. 6). Ihh is induced by P4 in the mouse uterus, and Pgr-Cre–mediated Ihh mutation in the mouse causes implantation failure (3, 29, 40). In the absence of Ndst genes, luminal induction of Ihh occurs normally, yet activation of Hh signaling happens only in the subepithelial stroma. Hh diffusion in the Drosophila wing disc requires HS function, as evidenced by studies on mutations in genes involved in HS biosynthesis, including sfl, tout-velu, sister of tout-velu, and brother of tout-velu (41–43). Mutation in the HSPG core protein Dlp results in defects almost identical to those of hh mutants in the Drosophila embryonic epidermis, where Hh cannot travel from Hh-expressing cells to adjacent cells (44). It has also been speculated that HSPGs regulate Hh ligand stability by shielding it from degradation (45). Our study demonstrates that HS function is likely required in the mouse uterus for proper IHH signal transduction and propagation. Loss of long-range IHH signaling in uterine stromal cells may render them incapable of decidualization to support subsequent implantation events. Expression of NDST1 and NDST2 has been reported in human placenta (46), and a decreased sulfated proteoglycan level is associated with preeclampsia (47). However, the involvement of HSPG sulfation in human implantation and decidualization requires further investigation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Xin Zhang (Indiana University School of Medicine) and Dr. Francesco DeMayo (National Institute on Environmental Health Sciences) for providing the Ndst conditional knockout mice and Pgr-Cre mice, respectively. We thank members of the Ma laboratory for critical comments on the manuscript.

Financial Support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grants HD082792 and HD087973 (to L.M.) and HD049010 (to B.M.B.).

Author Contributions: Y.Y. and L.M. conceived the study and wrote the paper. Y.Y., A.W., L.F., Y.W., H.Z., and I.Z. performed experiments and analyzed results. B.M.B contributed a key reagent and revised the manuscript with important intellectual input. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AP

alkaline phosphatase

- Aqp

aquaporin

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- CTRL

control

- dpc

days postcoitum

- E2

17β-estradiol

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HBSS

Hanks balanced salt solution

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- Hh

hedgehog

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- HS

heparan sulfate

- HSPG

heparan sulfate proteoglycan

- IHH

Indian hedgehog

- NDST

N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase

- P4

progesterone

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- Ptch1

patched 1

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcription PCR

- tKO

triple-knockout

Appendix.

Antibodies Used

| Name of Antibody | Manufacturer, Catalog No. | Species Raised in; Monoclonal or Polyclonal | Dilution Used | RRID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti–E-cadherin | BD Biosciences, 610181 | Mouse; monoclonal | 1:1000 | AB_397580 |

| Anti–phospho-histone H3 | Millipore, 06-570 | Rabbit; polyclonal | 1:1000 | AB_310177 |

| Anti-GAPDH | Cell Signaling Technology, 2118 | Rabbit; monoclonal | 1:2000 | AB_561053 |

| Anti-HS, 10E4 | United States Biological, H1890 | Mouse; monoclonal | 1:1000 | AB_10013601 |

| Anti-rabbit IgG (H+L), Alexa Fluor 594 | Thermo Fisher Scientific, A-11037 | Goat; polyclonal | 1:1000 | AB_2534095 |

| Anti-mouse IgG (H+L), Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific, A-1100 | Goat; polyclonal | 1:1000 | AB_2534069 |

| Anti-rabbit IgG, HRP linked | Cell Signaling Technology, 7074 | Goat; unknown | 1:5000 | AB_2099233 |

| Anti-mouse IgG, HRP linked | Cell Signaling Technology, 7076 | Horse; unknown | 1:5000 | AB_330924 |

Abbreviation: H+L, heavy chain and light chain.

References

- 1. Li Q, Kannan A, DeMayo FJ, Lydon JP, Cooke PS, Yamagishi H, Srivastava D, Bagchi MK, Bagchi IC. The antiproliferative action of progesterone in uterine epithelium is mediated by Hand2. Science. 2011;331(6019):912–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Franco HL, Dai D, Lee KY, Rubel CA, Roop D, Boerboom D, Jeong JW, Lydon JP, Bagchi IC, Bagchi MK, DeMayo FJ. WNT4 is a key regulator of normal postnatal uterine development and progesterone signaling during embryo implantation and decidualization in the mouse. FASEB J. 2011;25(4):1176–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee K, Jeong J, Kwak I, Yu CT, Lanske B, Soegiarto DW, Toftgard R, Tsai MJ, Tsai S, Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ. Indian hedgehog is a major mediator of progesterone signaling in the mouse uterus. Nat Genet. 2006;38(10):1204–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lin X. Functions of heparan sulfate proteoglycans in cell signaling during development. Development. 2004;131(24):6009–6021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coulson-Thomas VJ, Chang SH, Yeh LK, Coulson-Thomas YM, Yamaguchi Y, Esko J, Liu CY, Kao W. Loss of corneal epithelial heparan sulfate leads to corneal degeneration and impaired wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(5):3004–3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pan Y, Carbe C, Kupich S, Pickhinke U, Ohlig S, Frye M, Seelige R, Pallerla SR, Moon AM, Lawrence R, Esko JD, Zhang X, Grobe K. Heparan sulfate expression in the neural crest is essential for mouse cardiogenesis. Matrix Biol. 2014;35:253–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nigam SK, Bush KT. Growth factor-heparan sulfate “switches” regulating stages of branching morphogenesis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29(4):727–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang S, Kong S, Lu J, Wang Q, Chen Y, Wang W, Wang B, Wang H. Deciphering the molecular basis of uterine receptivity. Mol Reprod Dev. 2013;80(1):8–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang H, Dey SK. Roadmap to embryo implantation: clues from mouse models. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7(3):185–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grobe K, Inatani M, Pallerla SR, Castagnola J, Yamaguchi Y, Esko JD. Cerebral hypoplasia and craniofacial defects in mice lacking heparan sulfate Ndst1 gene function. Development. 2005;132(16):3777–3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Soyal SM, Mukherjee A, Lee KY, Li J, Li H, DeMayo FJ, Lydon JP. Cre-mediated recombination in cell lineages that express the progesterone receptor. Genesis. 2005;41(2):58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yin Y, Lin C, Sawalha D, Bany BM, Ma L. Molecular analysis of implantation defects in homeobox gene Hoxa10-deficient mice. Reprod Syst Sex Disord. 2011:S1:001.

- 13. Yin Y, Lin C, Ma L. Msx2 promotes vaginal epithelial differentiation and Wolffian duct regression and dampens the vaginal response to diethylstilbestrol. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20(7):1535–1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yin Y, Huang WW, Lin C, Chen H, MacKenzie A, Ma L. Estrogen suppresses uterine epithelial apoptosis by inducing birc1 expression. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22(1):113–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Finn CA, McLaren A. A study of the early stages of implantation in mice. J Reprod Fertil. 1967;13(2):259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Uchida H, Maruyama T, Nishikawa-Uchida S, Oda H, Miyazaki K, Yamasaki A, Yoshimura Y. Studies using an in vitro model show evidence of involvement of epithelial-mesenchymal transition of human endometrial epithelial cells in human embryo implantation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(7):4441–4450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pan H, Deng Y, Pollard JW. Progesterone blocks estrogen-induced DNA synthesis through the inhibition of replication licensing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(38):14021–14026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dey SK, Lim H, Das SK, Reese J, Paria BC, Daikoku T, Wang H. Molecular cues to implantation. Endocr Rev. 2004;25(3):341–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Srivastava RK, Gu Y, Ayloo S, Zilberstein M, Gibori G. Developmental expression and regulation of basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor in rat decidua and in a decidual cell line. J Mol Endocrinol. 1998;21(3):355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Möller B, Rasmussen C, Lindblom B, Olovsson M. Expression of the angiogenic growth factors VEGF, FGF-2, EGF and their receptors in normal human endometrium during the menstrual cycle. Mol Hum Reprod. 2001;7(1):65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lim W, Bae H, Bazer FW, Song G. Stimulatory effects of fibroblast growth factor 2 on proliferation and migration of uterine luminal epithelial cells during early pregnancy. Biol Reprod. 2017;96(1):185–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Paiva P, Hannan NJ, Hincks C, Meehan KL, Pruysers E, Dimitriadis E, Salamonsen LA. Human chorionic gonadotrophin regulates FGF2 and other cytokines produced by human endometrial epithelial cells, providing a mechanism for enhancing endometrial receptivity. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(5):1153–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Surveyor GA, Gendler SJ, Pemberton L, Das SK, Chakraborty I, Julian J, Pimental RA, Wegner CC, Dey SK, Carson DD. Expression and steroid hormonal control of Muc-1 in the mouse uterus. Endocrinology. 1995;136(8):3639–3647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Braga VM, Gendler SJ. Modulation of Muc-1 mucin expression in the mouse uterus during the estrus cycle, early pregnancy and placentation. J Cell Sci. 1993;105(Pt 2):397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Richard C, Gao J, Brown N, Reese J. Aquaporin water channel genes are differentially expressed and regulated by ovarian steroids during the periimplantation period in the mouse. Endocrinology. 2003;144(4):1533–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Monsivais D, Clementi C, Peng J, Titus MM, Barrish JP, Creighton CJ, Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Matzuk MM. Uterine ALK3 is essential during the window of implantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(3):E387–E395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee KY, Jeong JW, Wang J, Ma L, Martin JF, Tsai SY, Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ. Bmp2 is critical for the murine uterine decidual response. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(15):5468–5478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cha J, Sun X, Dey SK. Mechanisms of implantation: strategies for successful pregnancy. Nat Med. 2012;18(12):1754–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Matsumoto H, Zhao X, Das SK, Hogan BL, Dey SK. Indian hedgehog as a progesterone-responsive factor mediating epithelial–mesenchymal interactions in the mouse uterus. Dev Biol. 2002;245(2):280–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yin Y, Lin C, Veith GM, Chen H, Dhandha M, Ma L. Neonatal diethylstilbestrol exposure alters the metabolic profile of uterine epithelial cells. Dis Model Mech. 2012;5(6):870–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Humphries DE, Wong GW, Friend DS, Gurish MF, Qiu WT, Huang C, Sharpe AH, Stevens RL. Heparin is essential for the storage of specific granule proteases in mast cells. Nature. 1999;400(6746):769–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Naftalin RJ, Thiagarajah JR, Pedley KC, Pocock VJ, Milligan SR. Progesterone stimulation of fluid absorption by the rat uterine gland. Reproduction. 2002;123(5):633–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nardo LG, Sabatini L, Rai R, Nardo F. Pinopode expression during human implantation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;101(2):104–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Enders AC, Nelson DM. Pinocytotic activity of the uterus of the rat. Am J Anat. 1973;138(3):277–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang Y, Chen Q, Zhang H, Wang Q, Li R, Jin Y, Wang H, Ma T, Qiao J, Duan E. Aquaporin-dependent excessive intrauterine fluid accumulation is a major contributor in hyper-estrogen induced aberrant embryo implantation. Cell Res. 2015;25(1):139–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lin X, Buff EM, Perrimon N, Michelson AM. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans are essential for FGF receptor signaling during Drosophila embryonic development. Development. 1999;126(17):3715–3723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Blaber M, DiSalvo J, Thomas KA. X-ray crystal structure of human acidic fibroblast growth factor. Biochemistry. 1996;35(7):2086–2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pantoliano MW, Horlick RA, Springer BA, Van Dyk DE, Tobery T, Wetmore DR, Lear JD, Nahapetian AT, Bradley JD, Sisk WP. Multivalent ligand-receptor binding interactions in the fibroblast growth factor system produce a cooperative growth factor and heparin mechanism for receptor dimerization. Biochemistry. 1994;33(34):10229–10248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kan M, Wang F, Xu J, Crabb JW, Hou J, McKeehan WL. An essential heparin-binding domain in the fibroblast growth factor receptor kinase. Science. 1993;259(5103):1918–1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Takamoto N, Zhao B, Tsai SY, DeMayo FJ. Identification of Indian hedgehog as a progesterone-responsive gene in the murine uterus. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16(10):2338–2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Han C, Belenkaya TY, Khodoun M, Tauchi M, Lin X, Lin X. Distinct and collaborative roles of Drosophila EXT family proteins in morphogen signalling and gradient formation. Development. 2004;131(7):1563–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. The I, Bellaiche Y, Perrimon N. Hedgehog movement is regulated through tout velu–dependent synthesis of a heparan sulfate proteoglycan. Mol Cell. 1999;4(4):633–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bellaiche Y, The I, Perrimon N. Tout-velu is a Drosophila homologue of the putative tumour suppressor EXT-1 and is needed for Hh diffusion. Nature. 1998;394(6688):85–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Han C, Belenkaya TY, Wang B, Lin X. Drosophila glypicans control the cell-to-cell movement of Hedgehog by a dynamin-independent process. Development. 2004;131(3):601–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bornemann DJ, Duncan JE, Staatz W, Selleck S, Warrior R. Abrogation of heparan sulfate synthesis in Drosophila disrupts the Wingless, Hedgehog and Decapentaplegic signaling pathways. Development. 2004;131(9):1927–1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Heyer-Chauhan N, Ovbude IJ, Hills AA, Sullivan MH, Hills FA. Placental syndecan-1 and sulphated glycosaminoglycans are decreased in preeclampsia. J Perinat Med. 2014;42(3):329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Warda M, Zhang F, Radwan M, Zhang Z, Kim N, Kim YN, Linhardt RJ, Han J. Is human placenta proteoglycan remodeling involved in pre-eclampsia? Glycoconj J. 2008;25(5):441–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]